1. Introduction

Today, approximately 6.3 billion metric tons of plastics are consumed worldwide each year, which at the end of their useful life are discarded into the environment, where they have a high potential to generate large amounts of microplastics (MP) [

1,

2]. The MP are pieces of different morphologies, sizes, and polymeric compositions, which present approximate sizes of 5mm to 1µm. MP origin is from industrial production (primary microplastics) and from the fragmentation of larger plastic waste (secondary microplastics) [

3]. The presence of MP has been identified in soil, air, and water, of which polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyvinyl chloride (PVC) stands out, to mention the most common [

4]. These MP are considered emerging pollutants because they are not yet contemplated in regulatory environmental standards and due to their multidimensional nature, they can pose a potential risk to the health of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, because all living organisms, human including are exposed to these polymeric particles [

5,

6]. Recent gender estimates, the annual consumption and inhalation of microplastics in girls is 74060 particles, in women 98305 particles, in boys 81331 particles and in men 121664 particles [

7]. In addition, in humans, MP have been found in placentas, feces, intestinal tract, and blood [

8,

9,

10,

11]; some authors have documented for example, that PET causes alterations in the intestinal fauna and affects the genomic stability of human lymphocytes [

10,

11].

Due to the complexity and polymeric diversity of these emerging pollutants, standardized protocols have not yet been established to accurately and truthfully determine the real concentration of these particles in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems and their impact on them due to the complexity and polymeric diversity of these emerging pollutants and the little knowledge of their impact, standardized protocols have not yet been established to accurately and truthfully determine the real amounts of these particles in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, in addition, their emission and transfer greatly hinders the implementation of policies and regulations on the maximum permissible limits for the control and elimination of MP in the environment [

12]. Derived from the above, in recent research various protocols for sampling, sample treatment, quantification and identification of MP have been used, in this sense, the most widely used analytical techniques for their identification are optical microscopy, FTIR spectroscopy, Raman and Pyr/GC/MS [

13], in this sense, FTIR is the most widely used technique for the identification of MP coming from WWTPs [

14]. For example, with FTIR spectroscopy coupled with optical microscopy, the polymeric composition of MP can be identified for small sizes from ≥ 20 µm [

12].

Regarding wastewater treatment systems, there are different types of WWTPs (secondary and tertiary) that, according to the physicochemical characteristics of wastewater (municipal and industrial) eliminate various pollutants according to the policies and regulatory criteria for control and removal of each country [

15], research reports that the removal efficiencies of these microplastic particles in WWTPs (secondary and tertiary) are approximately 90 to 98%. However, despite these high percentages of elimination, these treated effluents continue to present concentrations of MP that are continuously transferred to the receiving bodies, which is why these discharges are considered sources of emission and exposure of these emerging pollutants to aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Due to the above, the current standards that establish the quality criteria applied to treated wastewater do not include MP within their reference frameworks and, therefore, these polymeric microparticles will continue to contaminate aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. About Mexico, the official Mexican standards (NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021; NOM-002-SEMARNAT-1996; NOM-SEMARNAT-1997) they do not contemplate MP within their regulatory frameworks, only the maximum permissible limits are established for the quality of discharges from WWTPs and whose effluents are destined for aquatic and terrestrial receiving bodies [

24,

25,

26,

27].

To know and measure the problem of MP in WWTPs and their emissions into the environment in Mexico, as a consequence of the lack of norms that regulate and establish maximum permissible limits, the purpose of this research is to detect, quantify and characterize MP in sizes from 150 to 38 µm through the optical microscopy and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) coupled spectroscopy techniques in wastewater and wastewater treated in three urban plants with secondary treatment in the city of Acapulco, in addition to estimating the percentages of removal of these pollutants based on the concentrations of MP in influents and effluents in each of the study WWTPs and projecting their daily and annual emissions to the receiving bodies. The results obtained provide knowledge base data for the development of technical and methodological criteria in the construction of policies and regulatory norms whose purpose is the elimination of MP from effluents and mitigate future damage to the environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. WWTP evaluated

Sampling was carried out in three WWTPs in the city of Acapulco (figure 1.); these are operated and administered by the para-municipal body, their purification systems are through activated sludge (secondary treatment). The WWTP A) is in the eastern part of the city, it has an operating capacity of 23 L/s for a population of 10,948 inhabitants, and the receiving body is the Tres Palos lagoon, WWTP B) is in the suburban area of the city, it has an operating capacity of 350 L/s for a population of 166,600 inhabitants, its treated effluents are discharged into the Sabana river, tributary of the Tres Palos lagoon. WWTP C) is in the western area of the city, has an operating capacity of 650 L/s for a population of 309,400 inhabitants, its effluents are discharged into the sea through Olvidada beach.

The samples collection of influents and effluents in the three WWTPs was through point sampling during the months of June and July (dry season), October and November (rainy season) of 2022. The influents samples were collected from the intake pit at the WWTPs, after screening; the volume for each sample was 4 L. Regarding effluents, 20 L samples were collected at the WWTP outlet. Once the samples were collected, they were transported to the laboratory and stored at 15°C.

Figure 1.

WWTPs monitored location for this research: WWTP A) 23 L/s; WWTP B) 350 L/s and WWTP C) 650 L/s.

Figure 1.

WWTPs monitored location for this research: WWTP A) 23 L/s; WWTP B) 350 L/s and WWTP C) 650 L/s.

2.2. MP separation

The separation of MP from influents and effluents was carried out, based on the methodologies reported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and other researchers [

18,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Regarding the influents, the samples with a mesh opening of 300 µm (to retain the larger solids) were sieved, then with other screens the sizes of 150 and 38 µm were retained; the sieves are rinsed with distilled water to remove microplastic particles from each sieve and deposited in beakers. They were dried in an oven at 80 ± °C for 12 hours; then the digestion was carried out by adding 30 mL of 30% H2O2 at 60°C, it was left to stand for 2 hours; on the other hand, in the influent samples, another 30 mL of H

2O

2 was added, with 2 more hours, to make the digestion of organic matter more efficient. Once digestion is complete, they are allowed to cool to room temperature. Subsequently, the separation by density was carried out, adding 60 mL of ZnCl

2 (1.62 g/cm

3) to the samples placed in separation funnels, allowing them to settle for 12 hours. Under vacuum, the supernatant is passed through 47 mm diameter glass fiber filters that are later placed in Petri dishes for the MP counting and identification.

2.3. Quality control

To avoid cross contamination, cotton lab coats, gloves, and face masks were used. Prior to sample processing, all areas of the laboratory were cleaned using distilled water and 30% (v/v) ethanol. All reagents used were vacuum filtered on Whatman® filters (grade 41, 125 diameter). For the sampling, blanks (distilled water) were taken and analyzed according to the same protocol used for the influent and effluent samples. To assess the atmospheric quality of the laboratory, open Petri dishes were placed with Whatman® filter paper (grade 41, 125 in diameter) throughout the process; once completed, the exposed discs were analyzed by light microscopy. On the other hand, as a reference were used commercial PVC, PE, PET, and PP plastics for the identification of the MP detected in the influents and effluents of the WWTPs. The glass microfiber filter used during sample filtration was analyzed in FTIR to rule out interference in the spectra.

2.4. MP Characterization

The MP characterization was carried out with the classification criteria according to their color and morphology proposed by Hidalgo-Ruz et al. [

5]. For the counting and identification of MP, a SWIFT® M10 Series optical microscope was used with 4X and 40X objectives. Infrared spectra of the MP were recorded at room temperature in a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 100FT-IR (ATR) spectrometer with a resolution of 4 cm

-1 and were averaged over 4 scans in the range of 4000–650 cm

-1.

2.5. Daily and annual projections of removal efficiencies

The removal efficiencies were calculated with the MP obtained from the influents and effluents, according to what was proposed by Talvitie et al. [

34]. Regarding the daily and annual projections of MP release to the receiving bodies, the amounts obtained in the effluents (MP/L) were multiplied by the average daily operating flow in each WWTP (L/day); for annual concentrations, the total MP quantities per day was multiplied by 365 [

20].

2.6. Statistic analysis

For the comparison between the three WWTPs with respect to their MP removal and the sampling stations, statistical inference was made through one factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) (p<0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. MP detección

Through optical microscopy in the influents and effluents of three WWTPs, MP were detected in sizes from 150 to 38 µm (

Figure 2).

The MP detected in secondary treatment WWTPs are similar in their morphology to those reported in the literature, but with different size ranges [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

35,

36,

37]. Likewise, sizes from 10 to 1000 µm have been recorded [

31], 20 a ≥ 500 µm [

38], 43 a 355 µm [

39], 10 a 5000 µm [

19], 20 a 200 µm [

20], 20 a ≥ 300 µm [

33]. With respect to WWTPs with tertiary treatment systems [

29,

34], their morphology and appearance were similar to the results presented in this work. Due to the above, it is considered that unitary wastewater treatment systems do not affect the appearance and morphology of MP present in influents and effluents.

3.2. MP Physical characterization

3.2.1. MP Color

The MP detected during four sampling months in influents and effluents of the WWTPs, presented colors diversity (

Figure 3).

In the influents: the black color MP of WWTP A and, B (28.1% - 29.9% respectively) were the most abundant, while in WWTP C, the red color was the most abundant (33.7%). On the other hand, the blue color MP were the predominant ones in the effluents (49% for WWTP A and, 38% for WWTPs B and C), followed by red and purple colors. In contrast to the above, the presence of transparent plastics in WWTP A, B and, C were 6, 4 and 7%, respectively (

Figure 4). In other works, the black color MP predominated, followed by the transparent and blue ones [

18]. In Scotland, red color MP were found in greater numbers (26.7%) followed by blue (25.4%) and green (19.1%) colors [

20]. In China, white-colored PMs represent 27.3% of quantified plastics [

39]. It should be noted, that the presence of the different colors in the MP is due to the association with additives that are used in the plastics pigmentation [

40]. So not only the MP presence is a risk factor for the environment; according to recent studies, chemical additives added to polymers such as PE, PVC and PA can be toxic, in addition, this toxicity is often not due only to the presence of these polymers, but to the leachates from their additives [

41]. For example, the blue coloration in plastics may be due to the use of cobalt (II) diacetate (C

4H

6CoO

4) (additive applied to PET); for red pigmentation, various additives are used such as cadmium selenide (CdSe), lead sulfate (PbSO

4) and lead molybdate (PbMoO

4) (applied to various plastics) [

42]. It has been documented that the chemical production of additives is constantly increasing; it is estimated that the plastics production with their additives will be 20,000 million tons by 2050 [

22]. The aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems will be exposed to the MP constant emission and, other pollutants associated with them (heavy metals), if adequate regulations for the use of additives in the plastic industry are not implemented.

The influents and effluents of the WWTPs analyzed in this study, the abundance of MP according to their color reflect the complexity of these polymeric micropollutants that are transferred to the hydrological bodies, therefore, in addition to their implications for the environment, in the absence of regulatory policies and standards, they constitute a serious threat to the health of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. On the other hand, not only the toxicity degree attributable to microplastic polymers, but also their association with chemical additives represent a potential toxicological hazard due to the presence of heavy metals [

42]. Due to the above, we consider that the implementation of regulatory norms should consider the coloration of the MP, as an additional criterion for evaluating the quality of the treated effluents that are discharged into aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

In Mexico, there are currently no standards or criteria to date that regulate the manufacture of plastics and the use of additives, therefore, this lack of regulation has a considerable impact on the generation of MP, their emission and transfer to the environment. In this sense, there are only regulations that establish and describe the identification type that the plastics produced must have for their selection, separation, collection, collection and recycling [

43].

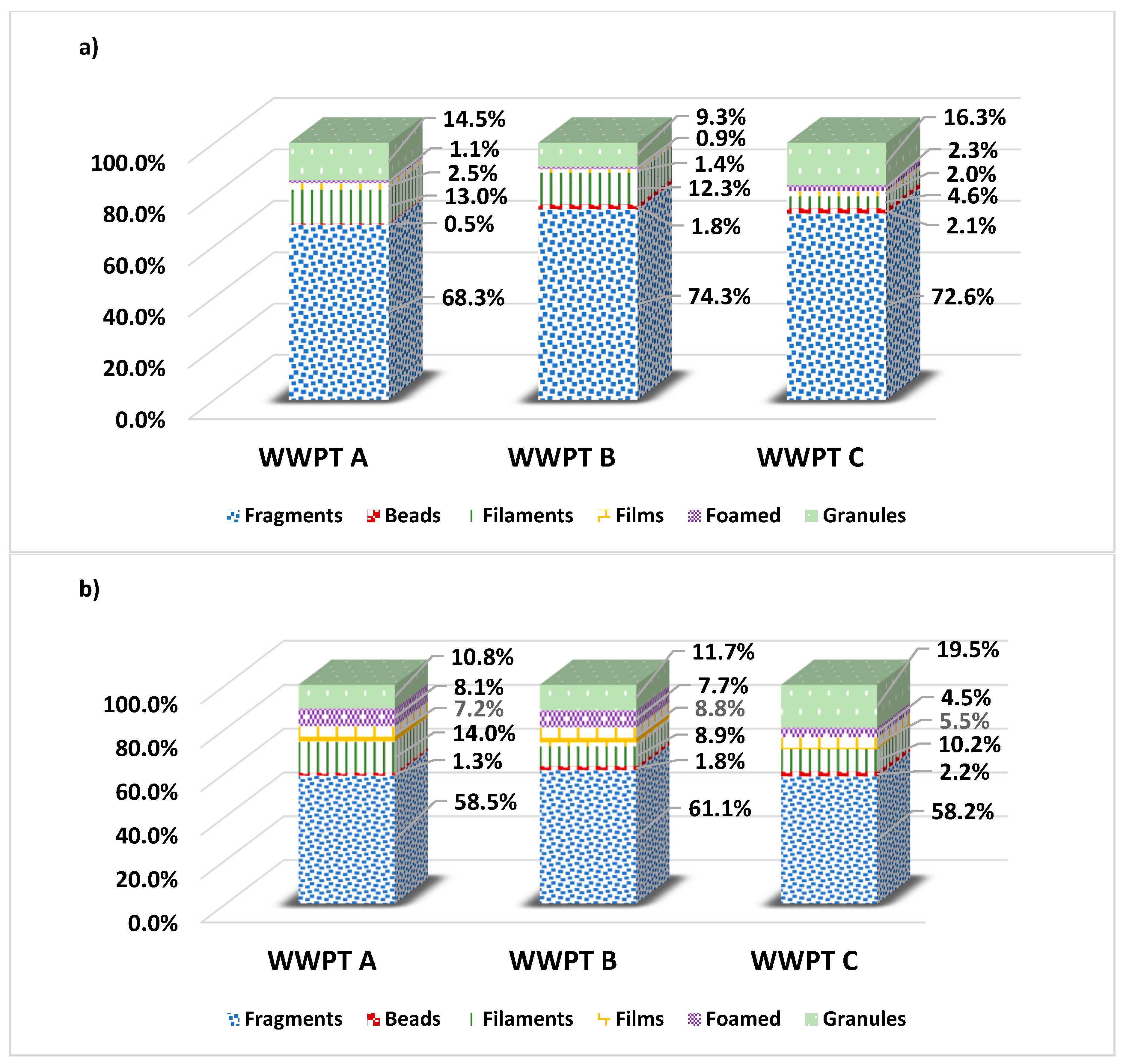

3.2.2. MP morphology

Various MP forms were found in the influents and effluents of the three WWTPs, the fragment-type morphology being the most abundant, followed by filaments (

Figure 4). There are no differences between the three WWTPs with respect to the MP morphological distribution in the treated effluents (ANOVA of one factor, F =0.11, p>0.05) (

Table 1) therefore, it can be deduced that the WWTPs studied present similar characteristics in the morphologies of admission to the WWTPs and those that are subsequently released to the receiving bodies.

In contrast to other studies, where filaments have been detected in greater numbers [

18,

21,

29,

44], granules [

39], fragments [

30] and scales [

20].

The importance of the morphological classification of the MP to know and identify the way in which they are degraded and to predict the possible mechanisms of transfer and absorption at the cellular level in the organisms of the trophic chain. In this sense, MP have been defined as vectors of other contaminants and pathogenic microorganisms; therefore, the morphology offers information on the potential risks in the transport of more dangerous pollutants, such as the chemical additives discussed in the previous section.

From the data obtained in this study, it can be deduced that most of the MP that enter and leave the WWTPs are secondary; however, significant amounts of filaments have also been detected, so it is inferred that many of these MP may be primary. As in the present study, in secondary treatment WWTPs in Korea, the fragments were the most abundant MP [

45]. In another context, the MP characterization according to their morphology will contribute to understanding the changes they undergo in their shape and size during purification processes [

46], this will allow the establishment of the maximum permissible limits of control and the development of technologies and complementary unit operations (tertiary treatment) to be incorporated into current systems, in accordance with the morphological typification in order to effectively eliminate these pollutants from the treated effluents that they carry as their destination the receiving hydrological bodies [

45,

47,

48,

49]. Countries like China, Kenya, and the European Union have implemented standards and public policies with the purpose of reducing the plastic pollutants generation. In this sense, in 2020 international agreements have been established with the goal of reducing single-use plastic products and packaging by up to 20% by 2025. [

5]. Despite these measures, there is an urgency to incorporate and establish criteria for the MP evaluation and control in effluents treated at WWTPs.

Due to the high MP concentrations that are destined for the various receiving bodies, these contaminants present a sizes diversity, colors and shapes, which is related to the variety of effects on living beings [

5]. In addition, it is known that during the plastics manufacture, additives are used to provide the characteristics required in them, adding another pollution factor associated with MP. These chemical compounds can be harmful to health, so it is important to characterize and classify them in the generation of basic scientific knowledge for the development of regulatory standards [

16].

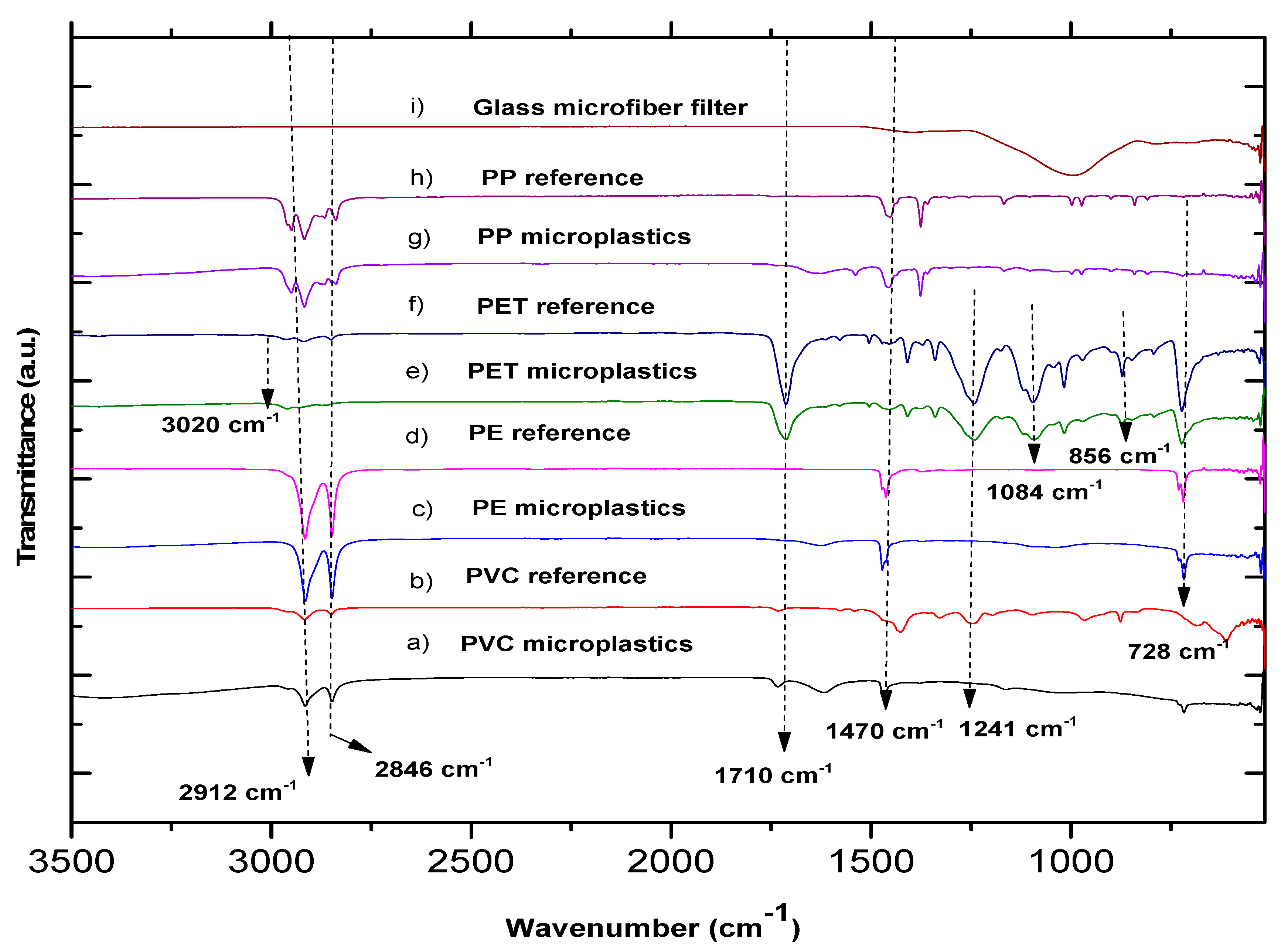

3.3. MP Characterization by FTIR

In the influent and effluent samples, four types of polymers were detected: polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and, polypropylene (PP), all about identified with the FTIR instrumental technique (

Figure 5). To verify their identification, the spectra obtained were compared with the reference spectra or conventional polymers.

According to the different characteristic vibration signals presented in the MP in the samples and the reference ones (

Table 2.), the signals of the functional groups of each one of the plastics detected, their coincidence with their reference plastic was compared. Based on these results, PET, PE, PP and PVC are the polymers with the highest frequency in the influents and effluents in the three WWTPs evaluated in Acapulco. (

Figure 5). It is worth mentioning that the vibration signals of the FTIR spectrum of the glass fiber paper used to filter the samples did not interfere with the vibration signals of the spectra of the MP analyzed (

Figure 5).

According to the spectra identified in this study, the four polymers (PET, PVC, PP and PE) have also been reported in other investigations as the most abundant [

18,

19,

20,

37,

38,

52,

53,

54]. However, in addition to these polymers, other studies have detected the presence of polyurethane (PU), polyphenylene oxide (PPO), nylon (PA), phenolic epoxide (PER), polyacrylonitrile (PAN) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), among others [

18]. The detection of other MP in different WWTPs in the world depends on particular consumption type of plastics in each country and city. On the other hand, the source of wastewater that enters the WWTPs, such as those that come from the combination of industrial and domestic waste, report more types of polymers with respect to discharges for domestic use [

19,

29]. One limitation to consider for this work was that the samples obtained (by sieve sizes) and analyzed (equipment used) were in sizes 150 and 38 µm, so the possibility of having other polymers in other particle sizes. It should be noted that the WWTPs analyzed in this research receive only domestic wastewater, so in this sense, when comparing the results obtained with similar WWTPs, similarities are observed in the identified polymers: for example, in WWTPs in Colombia, it is reported to low density polyethylene (LDPE), PP, PET and PS [

31], in another similar case, the MP identified in a WWTP of a Chinese province, the ones with the highest abundance were PP, PE, PS and PET [

51], however, unlike this study, in both works, they do not report PVC, and they coincide in the PS identification.

Furthermore, the type of discharge (industrial, domestic or mixed) can determine the predominance of PMs in influents and effluents [

32]. Plastics, such as those detected in this study, are the basis for establishing classification criteria on the types of discharge that enter the WWTPs and their discharge to the receiving bodies in cities with a tourist vocation in the medium and long term; Therefore, not only the chemical characterization of the MP is enough to dimension the problem, but it is necessary to quantify the number of particles that enter and leave the WWTPs to determine the removal percentages of each WWTP and thus have an objective evaluation on the operating conditions and the emissions of these particles whose permanent destination is the receiving bodies [

34].

3.4. MP concentration and removal efficiencies

The MP particles in influents and effluents in the three WWTPs studied presented different amounts and removal percentages with respect to the sampling months (

Table 3). Removal efficiency from monthly sampling and analysis was calculated for each microplastic particle size (150 and 38 µm respectively).The removal efficiency of MP in the Acapulco WWTPs present similar percentages with respect to other investigations of secondary treatment systems. For example, in Italy 95% were registered by WWTP [

18,

30]; in China from 79.33 to 97.84% [

18]; Colombia from 93.2 to 94.19% [

31]; Canada 99% [

44] and, Scotland 98% [

20]. In this context, it was considered to analyze only the influents and effluents in the three WWTPs, so it can be deduced that the retained MP are found mostly in the sludge from the secondary clarifiers, after the biological treatment. According to different studies, most of the retained MP are detected in biological sludge, so it is considered that the largest amount of MP is intercepted in primary and secondary [

18,

30,

35,

36,

37,

39,

45,

54,

55,

56]; therefore, secondary treatment systems for biological sludge retain and concentrate most of the MP in primary and secondary sedimentation.

Temporality is a factor that influences the concentration, distribution, and removal of MP in WWTPs [

46,

57]. However, in different studies it is not specified if rainwater can be a factor in the removal efficiency of MP during treatment. According to the data obtained in this study, weather conditions are a variability factor in the entry and emission of MP. Thus, during the rainy season, the entry of MP to the WWTPs increased, which decreases the removal efficiencies in the three WWTPs. The samples collected in June (dry season) presented the highest removal efficiencies (98.7%), while in the month of November (rainy season) the lowest removal efficiencies were obtained (82.5%). This difference is due to the fact that the pluvial currents interfere with the influents during the rainy seasons, for which it is inferred that they significantly influence the transfer, transport and emission of MP to the WWTPs, due to the connection of the pluvial channels with the network. plumbing in the city of Acapulco. Taking into account the statistical analysis ANOVA of a factor (p<0.05) there are significant variations in the concentrations of MP between the dry and rainy months in influents and effluents (

Table 4) (F calculated > F critical). In Korea, in treated effluents from a WWTP, higher concentrations of MP were reported in the rainy season than in the dry season [

57], presenting similarity with this study; on the contrary, in WWTPs of China, the MP concentrations and removal efficiencies were higher in dry seasons than in rainy seasons [

46]. We believe that factors such as exposure to the elements of urban solid waste in storm channels and hydrosanitary operating conditions contribute to the increase of MP in urban wastewater treatment systems.

Regarding the removal in each of the WWTPs analyzed in Acapulco, similarity was found between them, in the values of the MP removal percentages: WWTP A), 93.6%; WWTP B), 93.06%; WWTP C), 93.91%. Through the analysis of variance by one factor ANOVA (p>0.05) it was observed that there are no significant differences in the MP purification processes (

Table 5), for which it is demonstrated that the three WWTPs present similarities in the MP elimination for secondary treatment systems.

It has been documented that WWTPs with tertiary treatment systems have higher removal percentages than primary and secondary systems; their removal rates can reach approximately 99.9% [

32,

47]. This is an alternative to further reduce MP concentrations in treated effluents. Regarding the WWTPs analyzed in Acapulco, they do not present tertiary treatment, so it is suggested to consider in the future the incorporation of advanced systems that purify MP in the treated effluents before they are finally sent to the receiving bodies.

In this sense, complementary technological alternatives for the purification of treated effluents, for example, in effluent treatments treated by sand filtration, the removal percentages obtained were 99.2 - 99.4% [

48]; the removal percentages using disk filters was 89.7% [

49]; on the other hand, in Germany, with an advanced oxidation system induced by organosilanes in parallel to a filtration system using granular activated carbon in a pilot plant coupled to a municipal WWTP, they obtained a removal of MP of 60.9 %. [

58]; in China, through the use of biofilters, removal percentages of 79% and 89% by mass of microplastic particles in treated effluents were obtained [

59].

The secondary treatment systems in the three Acapulco WWTPs present high MP removal rates, however, despite this, significant amounts of MP continue to be released into water bodies [

33]. It is necessary to implement regulatory norms and policies that allow establishing technical criteria to increase the removal of MP and prevent their entry into aquatic ecosystems, hence the importance to extrapolate the values obtained in this study with respect to the capacities of WWTP operation, to know the daily and annual concentrations of MP whose final destination is aquatic environments (rivers, coastal lagoons, wetlands and sea).

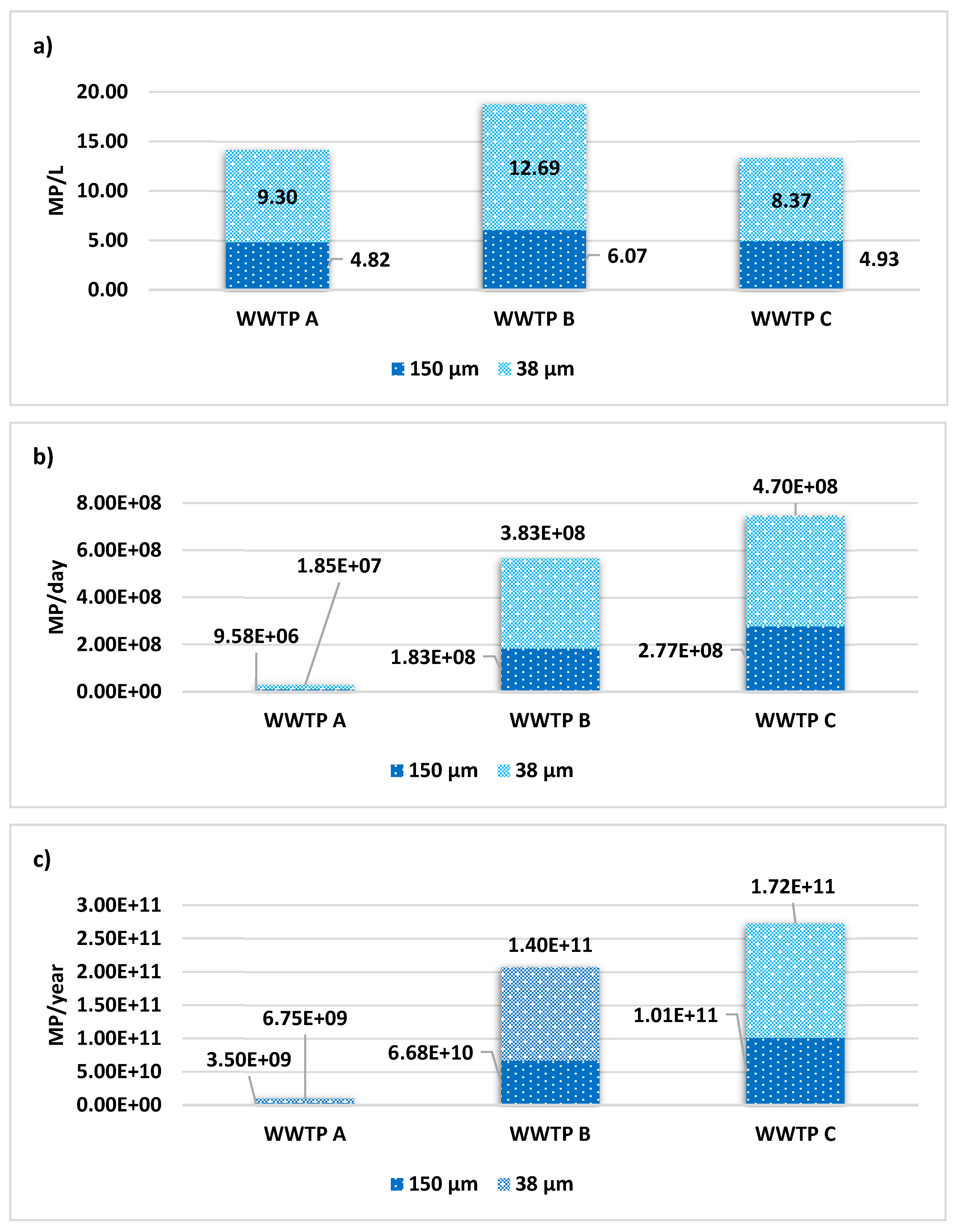

3.5. Daily and annual MP emission projections

The average concentrations of MP during four months of study (

Figure 6) reveal that the effluents from WWTP B) present higher concentrations of MP (

Figure 6 a). In this sense, the three WWTPs release a greater quantity of microplastic particles in sizes of 38 µm. According to the operating capacity, WWTP C) is the one that releases the greatest amount of MP per day to hydrological bodies with values of 2.77 x 10

8 (150 µm) and 4.70 x 10

8 (38 µm) particles (

Figure 6 b). For example, contrasting the treatment systems in similar works, in Scotland, the approximate daily emission was 65 x 10

6 particles [

20], in Italy the emissions from one of its largest WWTPs (for a population served of 1,200,000 inhabitants) is 160 x 10

6 PM per day [

19], while in China its average emission per WWTP amounts to 650 x10

6 PM per day [

39].

Regarding other studies carried out in tertiary treatment systems, average MP emissions of 2.2 x 10

7 particles/day have been recorded [

29], in Spain, the estimate of MP released according to the particular conditions of the evaluated WWTPs it was 1.6 x 10

7/day [

4]. In this sense, the daily projections of the three WWTPs in this study indicate that their secondary treatment systems require other complementary technologies in order to reduce the concentration of MP in their effluents and prevent their spread to the different receiving bodies.

In Acapulco, the record of the annual MP emission projections (

Figure 6 c), WWTP C presents the highest MP emission values because it is the largest WWTP studied (650 L/s). However, the annual emission values are estimated based on the concentrations of MP obtained from specific samplings, so the annual concentration may present significant variations with respect to estimates based on composite samplings, however despite this limitation, the information obtained allows us to know the problem of microplastic contamination in municipal WWTPs in Mexico and specifically in a tourist city.

Despite the various works on the presence of MP in WWTPs, in several of these studies no annual projections have been reported [

8,

18,

21,

29,

30,

31,

32,

45,

47,

54,

55,

60], however, in others one with development of projections, it is highlighted that the annual emissions of MP from WWTPs are approximately 0.3 x 10

9 particles [

44], 9 x 10

7 a 4 x 10

9 particles [

38] and 1.56 x 10

14 particles [

36]; the data obtained in this study are within the values estimated in the aforementioned investigations, so it can be deduced that the problem of removing MP in WWTPs is a global problem and that the establishment of regulatory standards and protocols standardized sampling and laboratory analysis is an urgent need to back away the emission of microplastic particles and the subsequent environmental degradation from the flow of these emerging pollutants.

4. Conclusions

The presence of MP was detected and characterized in three secondary-type municipal wastewater treatment plants in Acapulco, Mexico, monitored for four months, in the year 2022. About polymeric particles diversity according to their pigmentation, black color was the most abundant in the influents and red color in the effluents; in this sense, the MP coloring type must be considered in the regulatory criteria as indicators of other associated pollutants, such as heavy metals that are part of the additives used in the plastic industry and that represent a serious threat for living organisms, including humans.

The diversity of sizes and shapes in MP represent a challenge for the development of standardized analytical methodologies due to the multidimensional nature of these polymeric particles, so it is suggested to carry out studies in other size ranges to expand the knowledge of the qualitative and quantitative composition of these; in addition to developing in the immediate future, standardized analytical protocols, policies and regulatory standards; as well as the design and implementation of complementary technologies to the current wastewater treatment systems in Acapulco, in order to effectively retain and eliminate them in their different dimensions.

This study shows the role played by WWTPs in the retention and elimination of MP, given the alarming global problem about the use of plastics and their degradation, and currently consider them be emerging pollutants. In this sense, within the current context in Mexico about the absence of regulations and policies related to the emerging problem of plastic degradation in small sizes such as MP; the results obtained in this work demonstrate its presence in Acapulco, Mexico in three secondary municipal wastewater treatment plants.

Regarding the removal efficiency of MP in the three WWTPs studied in Acapulco, the results obtained indicate that there are high percentages of removal, however, the effluents present considerable amounts of MP and they are continuously released to the receiving bodies. In this sense, temporality is a factor that influences the quantities and removal of these. Thus it was that in the months with rain the highest load of MP and the lowest removal efficiencies were detected.

On the other hand, the removal percentages in this study only considered the particle sizes of 150 and 38 µm, so its efficiency was only recorded based on this size parameter; in this way, the removal efficiencies for other MP sizes may be different, so it is suggested to incorporate finer meshes than those used in this research. The estimates of the MP annual load indicate that aquatic ecosystems are highly exposed to the inappropriate use, consumption and disposal of plastics and, to the lack of knowledge on their degradation to smaller sizes such as MP; for this reason, the implementation of regulatory policies and standards must be promoted.

To date in Mexico, there are no official Mexican standards that establish maximum permissible limits for the amounts of MP in treated effluents that are discharged to receiving bodies. Due to the above, it is recommended at the local and national level to continue advancing with work in other WWTPs in order to incorporate MP into the national agenda to update current regulations and policies in the medium term.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, EJ. F-M and JL. R-A; methodology, EJ. F-M., JL. R-A., A. H-R., and A.A-S; software, A. H-R., and A.A-S; validation, EJ. F-M., JL. R-A., A. H-R., and A.A-S; formal analysis, EJ. F-M., A.H-R., and JL. R-A; data curation, EJ. F-M., JL. R-A., A. H-R., and A.A-S; writing—original draft preparation, EJ. F-M and JL. R-A; writing—review and editing, EJ. F-M., JL. R-A., A. H-R., and A.A-S; visualization, EJ. F-M., JL. R-A., A. H-R., A.A-S., RM. B-C., and J-V-G; supervision, JL. R-A., A. H-R., and A.A-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded by CONAHCYT, Mexico., through graduate scholarship received by the first author (registration number 758303).

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this research are contained in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks to the Acapulco Municipality Drinking Water and Sewerage Commission (CAPAMA) for allowing access to their facilities, especially Q.F.B. Gabriel Cejudo Blanco with the wastewater treatment systems. The authors also thanks to the Research Center of the Universidad del Papaloapan, Tuxtepec campus for the equipment to polymers chemical identification and, Engineering in Water Treatment Systems S.A. de C.V., by the microscopy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science advances 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, L.J.J.; van Emmerik, T.; van der Ent, R.; Schmidt, C.; Lebreton, L. More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. Science advances 2021, 7, eaaz5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias, J.P.G.L.; Nash, R. Microplastics: Finding a consensus on the definition. Marine pollution bulletin 2019, 138, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A.; Rowland S., J.; John, A.W.G.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A.E. Lost at sea: Where is all the plastic? Science 2004, 304, 838–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Ruz, V.; Gutow, L.; Thompson, R.C.; Thiel, M. Microplastics in the marine environment: A review of the methods used for identification and quantification. Environmental Science &Technology 2012, 46, 3060–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, K.; Rochman, C.M. Microplastics: a multidimensional contaminant requires a multidimensional framework for assessing risk. Microplastics and Nanoplastics 2022, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.D.; Covernton, G.A.; Davies, H.L.; Dower, J.F.; Juanes, F.; Dudas, S.E. Human Consumption of Microplastics. Environmental Science & Technology 2019, 53, 7068–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefato, V.; Carnevali, O.; Papa, F.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; Baiocco, F.; Draghi, S.; D’Amore, E.; Rinaldo, D.; Matta, M.; Giorgini, E. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environment International 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabl, P.; Köppel, S.; Königshofer, P.; Bucsics, T.; Trauner, M.; Reiberger, T.; Liebmann, B. Detection of various Microplastics in Human Stool. Annals of internal medicine, 2019, 171, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, A.; Molinero, N.; Reinosa, J.J.; Alcolea-Rodriguez, V.; Portela, R.; Bañares, M.A.; Fernández, J.F.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. PET microplastics affect human gut microbiota communities during simulated gastrointestinal digestion, first evidence of plausible polymer biodegradation during human digestion. Scientific Reports, 2022, 12, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çobanoğlu, H.; Belivermiş, M.; Sıkdokur, E.; Kılıç, Ö.; Çayır, A. Genotoxic and cytotoxic effects of polyethylene microplastics on human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Chemosphere, 2021, 272, 129805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhatib, D.; Oyanedel-Craver, V. A critical review of extraction and identification methods of microplátics in wastewater and drinking wáter. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54, 7037–7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Park, B. Review of microplastic distribution, toxicity, análisis methods, and removal technologies. Water, 2021, 13, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dai, X.; Wang, Q.; Van Loosdrecht. ; Ni, B.J. Microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: Detection, occurrence and removal. Water research, 2019, 152, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A. Depuración y desinfección de aguas residuales, 5th ed.; Colegio de Ingenieros de caminos, canales y puertos, Spain, 2001 pp. 88–120.

- Calero, M.; Gody, V.; Quesada, L.; Martín-Lara, M.A. Green strategies for microplastics reduction. Green and Sustainable Chemestry, 2021, 28, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvim, C.B.; Bes-Piá, M.A; Mendoza-Roca, J.A. Separation and identification of microplastics from primary and secondary effluents and activated sludge from wastewater treatment plants. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2020, 402, 126293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, K.; Cui, S.; Kang, Y.; An, L.; Lei, K. Removal of microplastics in municipal sewage from China’s largest water reclamation plant. Water research, 2019, 155, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, S.; Binelli, A.; Pittura, L.; Avio, C.G.; Della Torre, C.; Parenti, C.C.; Gorbi, S.; Regoli, F. The fate of microplastics in an italian wastewater treatment plant. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 652, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Ewins, C.; Carbonnier, F.; Quinn, B. Wastewater treatment works (WwTW) as a source of microplastics in the aquatic environment. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50, 5800–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, J.; Heinonen, M.; Pääkkönen, J.P.; Vahtera, E.; Mikola, A.; Setälä, O.; Vahala, R. Do wastewater treatment plants act as a potential point source of microplastics? Preliminary study in the coastal Gulf of Finland, Baltic Sea. Water Science & Technology, 2015, 72, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mato, Y.; Isobe, T.; Takada, H.; Kanehiro, H.; Ohtake, C.; Kaminuma, T. Plastic resin pellets as a transport medium for toxic chemicals in the marine environment. Environmental Science & Technology, 2001, 35, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, M.; Pironti, C.; Motta, O.; Miele, Y.; Proto, A.; Montano, L. Microplastics in the aquatic environment: occurrence, persistence, análisis, and human exposure. Water, 2021, 13, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021; Norma Oficial Mexicana - Que establece los límites permisibles de contaminantes en las descargas de aguas residuales en cuerpos receptores propiedad de la nación. Comisión Nacional del Agua, Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de México, México, 2022.

-

NOM-002-SEMARNAT-1996; Norma Oficial Mexicana – Que establece los límites máximos permisibles de contaminantes en las descargas de aguas residuales a los sistemas de alcantarillado urbano o municipal. Comisión Nacional del Agua, Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de México, México, 1998.

-

NOM-003-SEMARNAT-1997; Norma Oficial Mexicana – Que establece los límites máximos permisibles de contaminantes para las aguas residuales tratadas que se reúsen en servicios al público. Comisión Nacional del Agua, Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de México, México, 1998.

-

Ley de Aguas Nacionales, Constitución Política Mexicana – Tiene por objeto regular la explotación, uso o aprovechamiento de dichas aguas, su distribución y control, así como la preservación de su cantidad y calidad para lograr su desarrollo integral sustentable. Cámara de Diputados del H. Congreso de la Unión, Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de México, México, 2023.

- Masura, J.; Baker, J.; Foster, G.; Arthur, C. Laboratory methods for the analysis of microplastics in the marine environment. NOAA Marine Debris Program, 2015, Technical Memorandum NOS-OR&R-48. https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/publications-files/noaa_microplastics_methods_manual.pdf.

- Blair, R.M.; Waldron, S.; Gauchotte-Lindsay, C. Average daily flow of microplastics through a tertiary wastewater treatment plant over a ten-month period. Water Research, 2019, 163, 114909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galafassi, S.; Di Cesare, A.; Di Nardo, L.; Sabatino, R.; Valsesia, A.; Fumagalli, F.S.; Corno, G.; Volta, P. Microplastic retention on small and medium municipal wastewater treatment plants and the role of the desinfection. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2022; 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Fernández, J.; Cano, H.; Guerra, Y.; Puello Polo, E.; Ríos-Rojas, J.F.; Vivas-Reyes, R.; Oviedo, J. Identification and quantification of microplastics in effluents of wastewater treatment plant by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Sustainability, 2022, 14, 4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, J.; Mikola, A.; Koinstinen, A.; Setälä, O. Solutions to microplastic pollution -Removal of microplastics from wastewater effluent with advanced wastewater treatment technologies. Water Research, 2017, 123, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee. H.; Kim, Y. Treatment characteristics of microplastics at biological sewage treatment facilities in Korea. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2018, 137, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, J.; Mikola, A.; Setälä, O.; Heinonen, M.; Koistinen, A. How well is microlitter purified from wastewater? – A detailed study on the stepwise removal of microlitter in a tertiary level wastewater treatmetn plant. Water Research, 2017, 109, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, B.O.; Salmi, P.; Räty, J.; Ryymin, K.; Talvitie, J.; Karjalainen, A.K.; Kukkonen, J.V. K:, Roussey, M.; Peiponen, K.E. Optical monitoring of microplastics filtrated from wastewater sludge and suspended in etanol. Polymers, 2021, 13, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, L.; Mei, Q.; Dong, B.; Dai, X.; Ding, G.; Zeng, E.Y. Microplastics in sewage sludge from the wastewater plants in China. Water Research, 2018, 142, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, A.M.; O’Conell, B.; Healy, M.G.; O’Connor, I.; Officer, R.; Nash, R.; Morrison, L. Microplastics in sewage sludge: Effects of treatment. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintenig, S.M.; Int-Veen, I.; Löder, M.G.J.; Primpke, S.; Gerdts, G. Identification of microplastics in effluents of waste water treatment plants using focal plane-based micro-Fourier-transform infrared imaging. Water Research, 2017, 108, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Park, B. Review of microplastics distribution, toxicity, analysis methods, and removal technologies. Water, 2021, 13, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahladakis, J.N.; Velis, C.A.; Weber, R.; Iacovidou, E.; Purnell, P. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2018, 344, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiras, R.; Verdejo, E.; Campoy-López, P.; Vidal-Liñán, L. Aquatic toxicity of chemically defined microplastics can be explained by functional additives. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 406, 124388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A.; Filella, M. Hazardous metal additives in plastics and their environmental impacts. Environment International, 2021, 156, 106622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

NMX-E-232-CNCP-2011; Norma Oficial Mexicana – Industria del Plástico. Símbolos de identificación de plásticos. Dirección General de Normas, Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de México, México, 2011.

- Gies, E.A.; LeNoble, J.L.; Noël, M.; Etemadifar, A.; Bishay, F.; Hall, E.R.; Ross, P.S. Retention of microplastics in a major secondary wastewater treatment plant in Vancouver, Canada. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2018, 133, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.J.; Hidayaturrahman, H.; Peera, S.G.; Lee, T.G. Elimination of microplastics at different stages in wastewater treatment plants. Water, 2022, 14, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Bao, T.; Hong, L.; Wu, K. Occurrence characterization and contamination risk evaluation of microplastics om Hefei’s urban wastewater treatment plant. Water, 2023, 15, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayo, J.; Olmos, S.; López-Castellanos, J. Assesment of microplastics in a municipal wastewater treatment plant with tertiary treatment: removal efficiencies and loading per day into the environment. Water, 2021, 13, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, S.; Weber, F.; Kerpen, J.; Winklhofer, M.; Engelhart, M.; Barkmann, L. Elimination of microplastics by downstream sand filters in wastewater treatment. Water, 2020, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Vianello, A.; Vollertsen, J. Removal of > 10µm microplastic particles from treated wastewater by a disc filter. Water, 2019, 11, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syberg, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Clausen, L.P.W.; van Calster, G.; van Wezel, A.; Rochman, C.; Koelmans, A.A.; Cronin, R.; Pahl, S.; Hansen, S.F. Regulation of plastic from a circular economy perspective. Green and Sustainable Chemestry, 2021, 29, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Dong, Q.; Zuo, Z.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Wu, W.M. Microplastics in a municipal wastewater treatment plant: fate, dynamic distribution, removal efficiences, and control strategies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2019, 225, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L.A.; Iordachescu, L.; Tumlin, S.; Vollersten, J. A complete mass balance for plastics in a wastewater treatment plant -Macroplastics contributes more than microplastics. Water Research, 2021, 2021, 117307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Yao, X.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, T. A review of the removal of microplastics in global wastewater treatment plants: Characteristics and mechanims. Environmental International, 2021, 146, 106277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yuan, W.; Di, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Transfer and fate of microplastics during the conventional activated sludge process in one wastewater tratment plant of China. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2019, 362, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lares, M.; Ncibi, M.C.; Sillanpää, M.; Sillanpää, M. Ocurrence, identification and removal of microplastic particles and fibers in conventional activated sludge process and advanced MBR technology. Water Research, 2018, 133, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Miino, M.C.; Caccamo, F.M.; Milanese, C. Microplastics in sewage sludge: A known but underrated pathway in wastewater treatment plants. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 12591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.J.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, M.S.; Lee, J.K.; Park, J.H.; Zoh, K.D. Distributions of microplastics in surface wáter, fish, and sediment in the vicinity of a sewage treatment plant. Water, 2020, 12, 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, M.T.; Myers, E.; Schober, D.; Korzin, A.; Thege, C.; Schuhen, K. Comparision of AOP, GAC, and novel organosilane-based process for the removal of microplastics at a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Water, 2023, 15, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Nord, N.B.; Bester, K.; Vollertsen, J. Microplastics removal from treated wastewater by a biofilter. Water, 2020, 12, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Z.T.; Cundy. A. B.; Croudace, I.W.; Warwick, P.E.; Celis-Hernández, O.; Stead, J.L. A rapid method for assessing the accumulation of microplastics in the sea surface microlayer (SML) of estuarine systems. Scientific Reports, 2018, 8, 9428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).