1. Introduction

Clopidogrel is one of the most prescribed antiplatelet drugs for cardiovascular diseases[

1]. Clopidogrel is a thienopyridine prodrug that requires activation by hepatic biotransformation in cytochrome CYP2C19 to form an active metabolite that selectively and irreversibly inhibits platelet aggregation[

2]. Some patients acquire clopidogrel resistance due to a CYP2C19 pharmacogenetic defect [

3]. Indeed in 2010, the Food and Drug Administration, in the product summary of clopidogrel, stated that pharmacogenetic testing of CYP2C19 could be used as an aid to assess therapeutic safety and to consider alternative strategies in patients with a predicted phenotype of clopidogrel resistance due to a CYP2C19 defect[

4,

5]. Moreover, pharmacogenetic resistance to clopidogrel was established with the demonstration of CYP2C19 enzymatic activity due to certain genetic polymorphisms such as CYP2C19*2 variant leading to high platelet reactivity and predicted altered phenotype and decreased antiagregant effect [

4]. CYP2C19*2 allele is the most frequent CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele in Europe, with CYP2C19*2 allele frequencies of approximately 12% in Europeans, 15% in African Americans, and around 30% in Asians[

6]. A patient is considered as resistant to clopidogrel due to pharmacogenetic factors in the presence of at least one CYP2C19*2 allele (heterozygous) with a predicted phenotype of Intermediate Metaboliser (IM), with an additional effect if both alleles are CYP2C19*2 (homozygous) with a predicted phenotype of Poor Metaboliser (PM)[

7,

8]. Consequently, patients with resistant phenotypes treated with clopidogrel have a higher risk of thrombotic disease[

9]. CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics associated with P2Y12 inhibitor prescription is beneficial in the prevention of cardiovascular disease[

10]. However, prescription indications for CYP2C19 pharmacogenetic testing remain unclear. Clinical Data Warehouses (CDW) are useful to obtain a “real-world picture” of clinicians’ use of pharmacogenetic testing[

11]. The objective of this study was to evaluate CYP2C19 pharmacogenetic testing and clopidogrel prescription using data from a clinical data warehouse (Entrepôt de Données de Santé Normand EDSaN)[

12].

2. Materials and Methods

The database of the CDW was searched for the electronic medical records (EMR) of patients who had CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics testing and clopidogrel prescription in our academic hospital between 9 February 2015 and 1 October 2022. The search query was: (clopidogrel OR plavix OR (clopidogrel (INN OR Plavix)) AND "CYP2C19" OR "P2C19" OR "2C19" OR "cytochrome C19"OR ("CYP2C19"OR "P2C19" OR "2C19" OR "cytochrome C19"~3).

Pharmacogenetics was performed for the pharmacogenetics variant

CYP2C19*2 (rs4244285) according to the standard operating procedure in our laboratory, and based on Taqman Polymerase Chain Reaction method[

8].

Patients and healthcare workers were pseudoanonymised in the data file. The following data were collected in an excel spreadsheet: prescribers of pharmacogenetics test, indications, pharmacogenetics prescription and results and consequent therapeutic management. Data collection and analysis were performed by two operators (AM and JW).

2.1. Ethics

The study planned to use data from the EDSaN CDW. Ethical approval was not required as the research was outside of the field of the Jardé Law (French Law regulating human research).

2.2. Endpoints

The study endpoints were CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics status, place in the therapeutic management of CYP2C19(a posteriori and a priori) and results and therapeutic management in patients on clopidogrel treatment.

2.3. Statistics

Results are described by absolute values and percentages. Graphs are drawn with the help of GraphPad (GraphPad Prism version 8, Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA,

www.graphpad.com).

3. Results

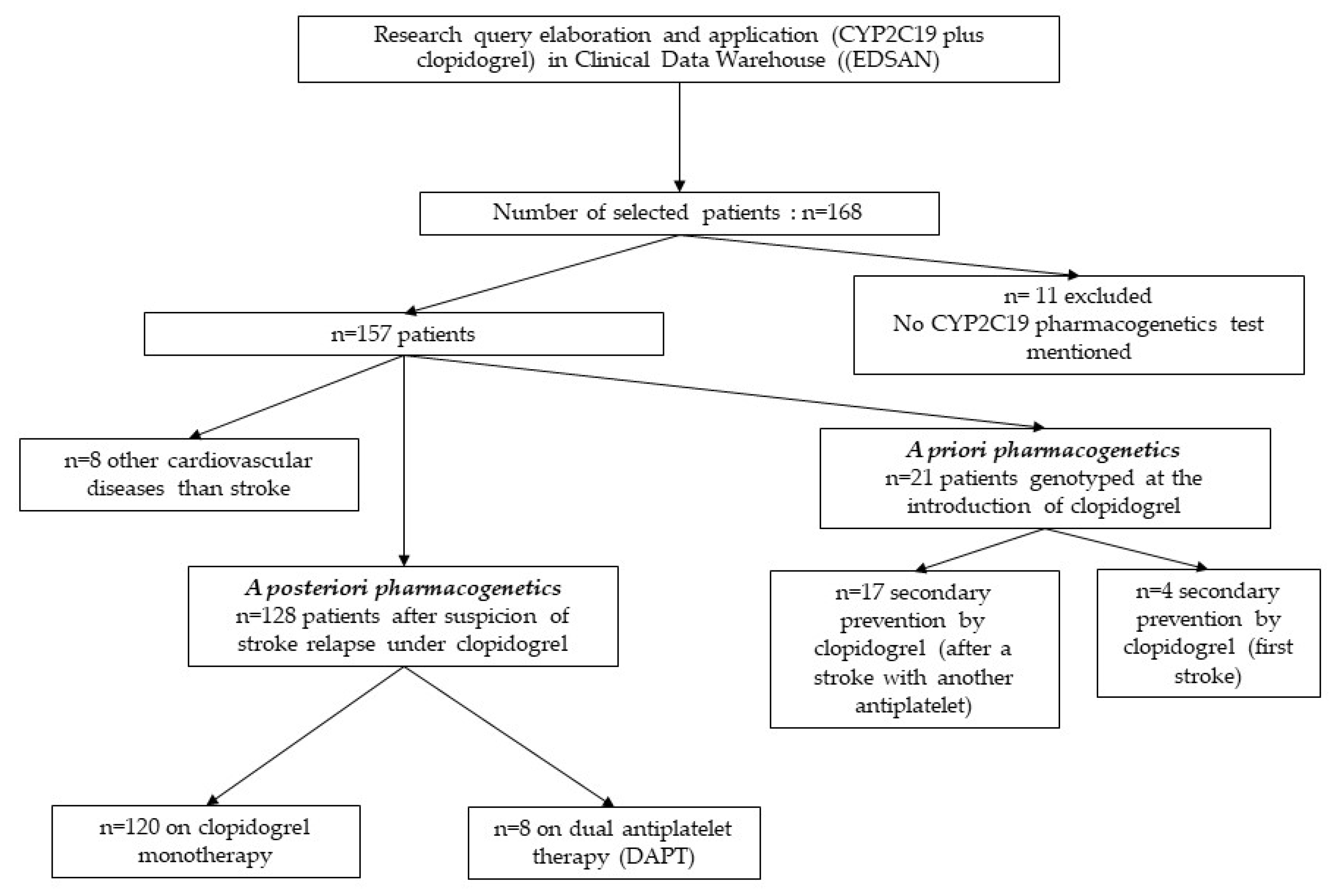

A total of 168 patients were screened. Finally, 157 patients were included in the study (figure 1). Eleven patients whose CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics test was not recorded in the EMR were not included in the study. The mean age was 72.4 years. The EMR of all patients were analysed, comprising 1994 medical reports, i.e., 11.9 reports per patient [min = 1; max = 145]. Eight patients had other cardiovascular diseases.

3.1. Prescribers

The majority of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics tests were prescribed by the neurology department, in 128 out of the 157 patients. The remaining tests were prescribed by the departments of geriatrics, hepato-gastro-enterology, vascular medicine, surgery, and internal medicine.

3.2. Indications (Figure 1)

Most indications for a CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics test were for a suspicion of stroke relapse a posteriori to clopidogrel prescription, in 128 out of the 157 patients. Among these 128 patients, 120 patients had a relapse of stroke on single clopidogrel therapy, and eight patients had a relapse of stroke on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of patients with CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics and clopidogrel treatment.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of patients with CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics and clopidogrel treatment.

The remaining indications for a CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics test were for a suspicion of stroke relapse a priori to clopidogrel prescription, in 21 patients. Among these 21 patients, 17 patients had a relapse of stroke on another antiplatelet such as lysine acetylsalicylate or aspirin, and 4 patients had clopidogrel for secondary prevention after a first stroke. Eight patients had other cardiovascular diseases than stroke.

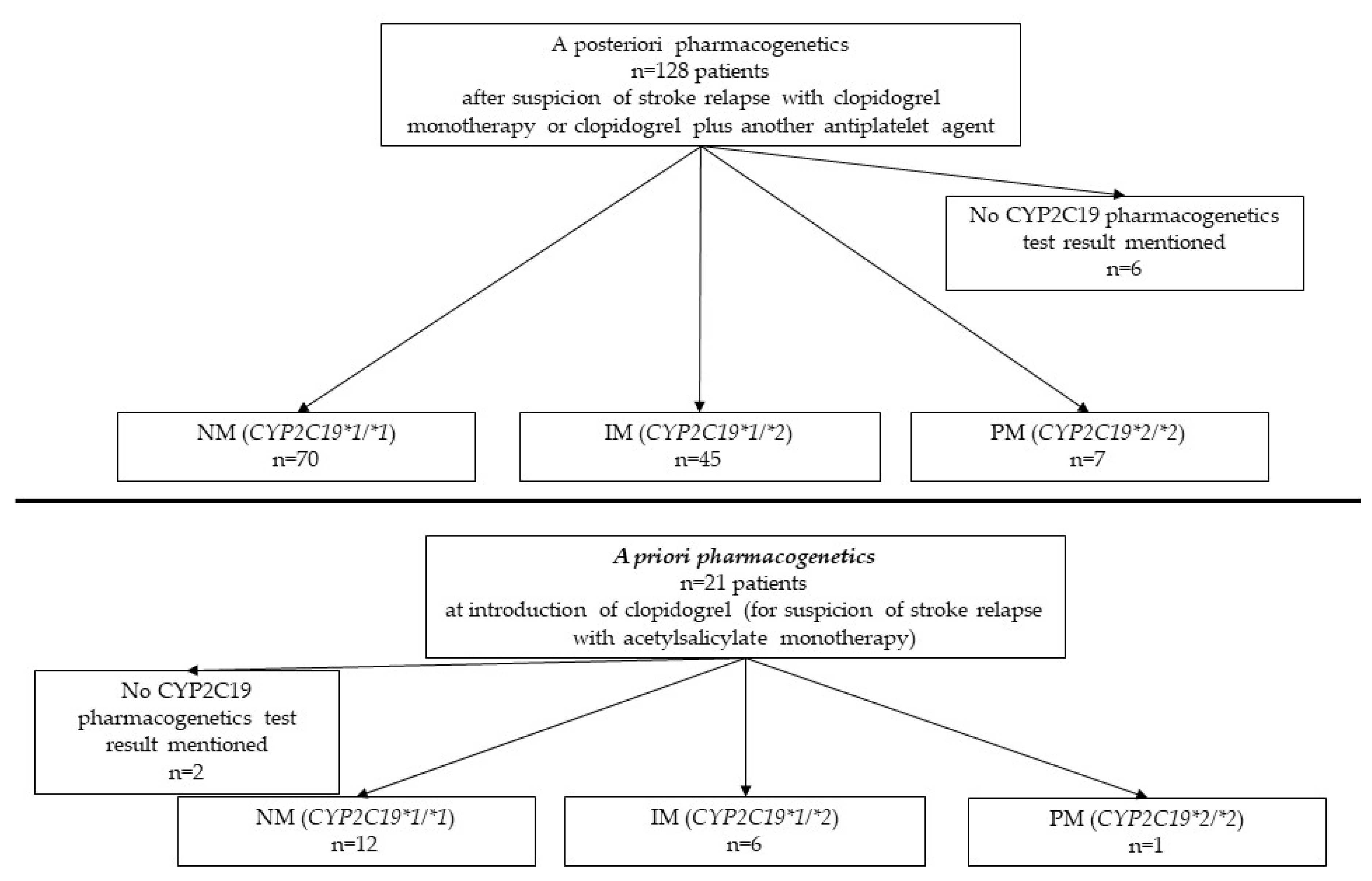

3.3. CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics (Figure 2)

The results of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics tests were: (i) 82 CYP2C19*1/*1 pharmacogenotypes considered sensitive to clopidogrel (NM), (ii) 51 CYP2C19*1/*2 pharmacogenotypes intermediate metabolizers (IM) considered as partially resistant to clopidogrel, (iii) 8 CYP2C19*2/*2 pharmacogenotypes considered fully resistant to clopidogrel (PM). Finally, in 8 patients, who had a pharmacogenetics prescription recorded in the EMR, no result was found.

Figure 2.

Flow-chart of patients with a posteriori and a priori groups pharmacogenetics (NM= normal metabolizer, IM= intermediate metabolizer, PM=poor metabolizer. Total NM patients is 82, IM patients is 51, PM patients is eight. Fifty-nine patients have pharmacogenetics resistance profile to clopidogrel. For eight patients, no CYP2C19 test result was mentioned.

Figure 2.

Flow-chart of patients with a posteriori and a priori groups pharmacogenetics (NM= normal metabolizer, IM= intermediate metabolizer, PM=poor metabolizer. Total NM patients is 82, IM patients is 51, PM patients is eight. Fifty-nine patients have pharmacogenetics resistance profile to clopidogrel. For eight patients, no CYP2C19 test result was mentioned.

Thus, of the 141 patients for whom test results were available, 59 were considered as pharmacogenetics resistant to clopidogrel.

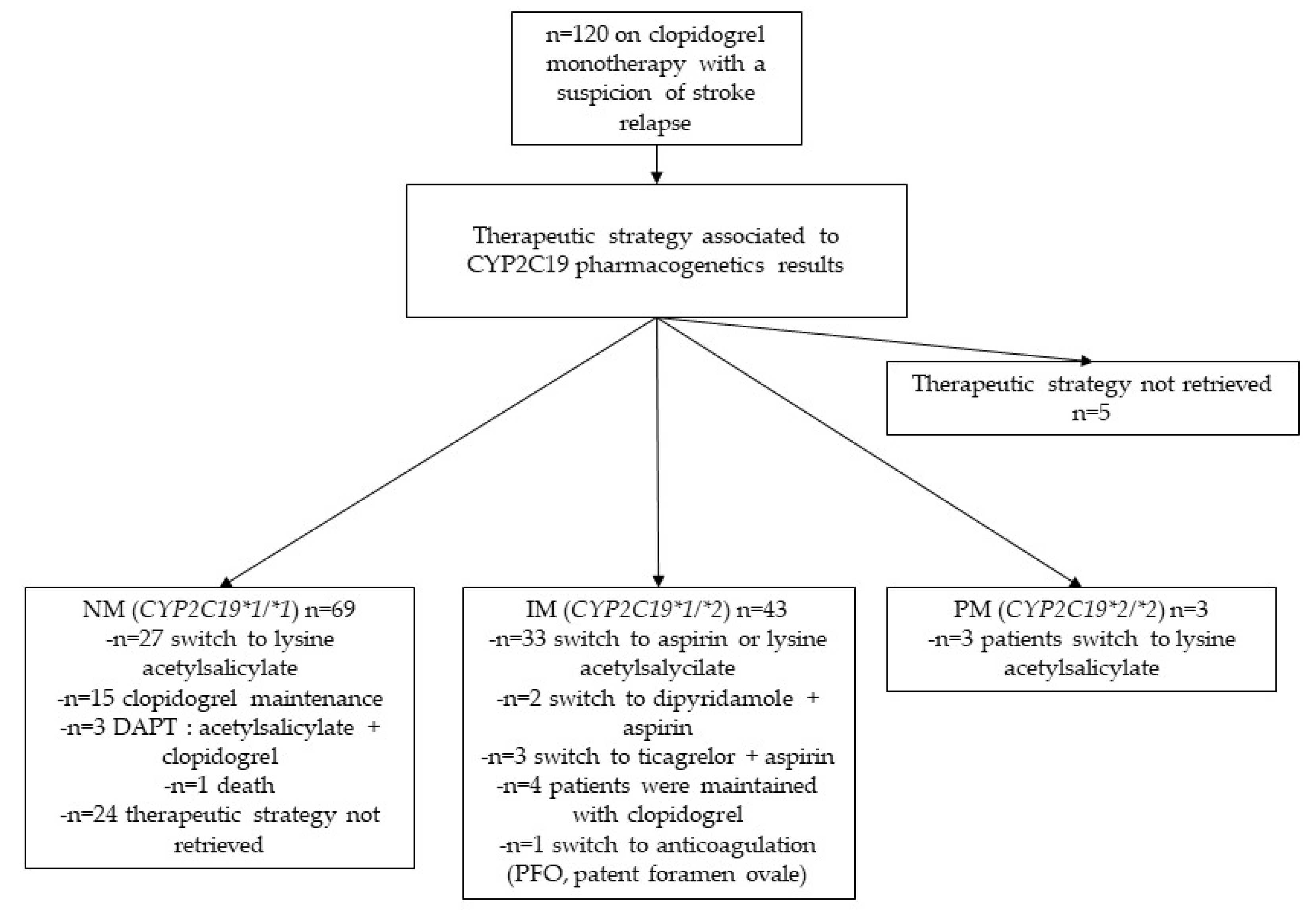

3.4. Therapeutic management (Figure 3)

The antiplatelet drug changes associated with pharmacogenetics test results were evaluated. Among the 49 patients identified as having pharmacogenetics resistance to clopidogrel (IM plus PM), 36 were switched to single antiplatelet therapy with lysine acetylsalicylate. Among patient labelled as pharmacogenetics resistant to clopidogrel, five patients were switched to DAPT, including 2 patients switched to dipyridamole and aspirin, and 3 patients switched to ticagrelor and aspirin. In 1 patient, clopidogrel was stopped in favour of an anticoagulant. Among the 69 patients who were normal metabolisers, 27 patients were switched from clopidogrel to lysine acetylsalicylate. For 5 patients, therapeutic strategy was not retrieved.

Figure 3.

Flow-chart of patients with clopidogrel treatment with a suspicion of stroke relapse. NM= normal metabolizer, IM= intermediate metabolizer, PM=poor metabolizer. Thirty-six patients with pharmacogenetics resistance have been switched to monotherapy with lysine acetylsalicylate. For five patients, therapeutic strategy was not retrieved.

Figure 3.

Flow-chart of patients with clopidogrel treatment with a suspicion of stroke relapse. NM= normal metabolizer, IM= intermediate metabolizer, PM=poor metabolizer. Thirty-six patients with pharmacogenetics resistance have been switched to monotherapy with lysine acetylsalicylate. For five patients, therapeutic strategy was not retrieved.

4. Discussion

In our study, almost half of the available pharmacogenetics test results showed a higher resistance to clopidogrel than in the general population. Compared to the population prevalence of pharmacogenetics CYP2C19*2 polymorphism14, this result suggests that patients with a resistance phenotype have a higher risk of stroke on clopidogrel treatment and require special medical care. Indeed, 26% of patients of European ancestry are classified as CYP2C19 IM [

13,

14]. Consequently, they have a higher risk of stroke relapse due to antiplatelet resistance[

14].

In our study, around four out of five patients had pharmacogenetics testing during a stay in neurology department. Indeed, neurologists were more prone to prescribe pharmacogenetics testing among potential prescribers. The main indication was stroke relapse (n=128 patients). The low prescription rate of CYP2C19 in cardiology could be explained by conflicting evidence regarding the usefulness of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics, which is a barrier to the implementation of these tests[

15]. Of the 128 patients who had a suspicion of stroke relapse on clopidogrel treatment, 52 carried at least one *2 allele, associated with clopidogrel resistance. In our study, the search for clopidogrel resistance was done in most cases following the occurrence of a probable stroke on clopidogrel (a posteriori group). In the a priori group, i.e. pharmacogenetics at a first prescription of clopidogrel, only a minority of patients had clopidogrel resistance. We strongly suggest implementing CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics at the introduction of clopidogrel, to support an early decision for antiplatelet drug modification. The positive impact of such a measure has already been demonstrated for high-risk acute coronary syndrome patients[

16] and would probably be similar for patients with stroke. In our academic hospital, the result of CYP2C19 genotype is accessible via the laboratory information system and paper laboratory reports. At this time, in France, to our knowledge, there are no clinical practice guidelines, produced by a healthcare agency, for the management of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics tests[

17]. In our study, most of patients on clopidogrel treatment were switched to single antiplatelet therapy with lysine acetylsalicylate, once pharmacogenetics resistance was detected. Recent scientific literature proposed guidelines for the interpretation of pharmacogenetics and its consequences on prescriptions [

7,

18,

19,

20]. Level of evidence is debated according to scientific literature, in particular, in stroke for CYP2C19 genotyping[

13]. In patients with pharmacogenetics resistance to clopidogrel, P2Y12 inhibitors not metabolised by CYP2C19 such as ticagrelor could be a therapeutic alternative, considering the benefit-risk balance (risk of thrombosis versus bleeding)[

13]. Worldwide, current antiplatelet drug therapeutic recommendations based on antiplatelet drugs are more focused towards a medicine considering the CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics status of the patient. Moreover, conflicting recommendations have been published by several pharmacogenetic working groups, according to a recent update of CYP2C19 CPIC Guidelines[

7,

13,

21].

The major strength of our study is the fact that it is a real-life study based on a CDW. It provides a snapshot of pharmacogenetics testing in an academic hospital for the gene-drug couple CYP2C19-clopidogrel since the implementation of the test in our hospital. However, the result was not transmitted or was not recorded in the EMR, and ambulatory reports were unattainable because of non-computerisation of the prescription department.

Among limitations of this study, access to routine laboratory tests was not available because of the absence of link between the CDW and the laboratory information system. Pharmacogenetics information was not retrieved for all the patients included. Another limitation was an absence of access to the platelet reactivity assessment in the CDW. Indeed, the presence of CYP2C19*2 allele has been associated with high residual platelet reactivity in clopidogrel therapy[

20].

In previous studies, prescription of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics in patients on clopidogrel treatment was shown to have a benefit in a cost-effectiveness strategy in order to prescribe the most effective antiplatelet drug[

21,

22,

23].

In our study, the number of patients who had pharmacogenetics testing was low. Increasing the number of pharmacist-led prescriptions could lead to better prescription of clopidogrel and CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics test[

21]. Another solution to increase the number of prescriptions, would be the implementation of a point-of-care CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics test at bedside as studied in the elaboration of clinical practice guidelines by the NHS for stroke[

24].

5. Conclusions

Perspectives related to this work are solutions (i) to overcome barriers for the clinical implementation of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics test and clopidogrel treatment[

25] (ii) to integrate CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics data in EMR with a clinical decision support system to aid efficient antiplatelet drug prescription based on CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics testing [

26]. Finally, clear clinical practice guidelines are needed to position CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics testing for the benefit of patients with stroke and other cardiovascular diseases.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, J.W. and A.M.; methodology, J.W. and J.G.; software, J.G. and S.D.; validation, J.W., A.M. J.G.and L.G.; formal analysis, J.W.,A.M.,L.G; investigation, J.W.,A.M.,L.G.; resources, J.W.,A.M.,.A.T.,J.G.,F.L.; data curation, J.W.,J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans.

Data Availability Statement

research data are available under specific request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Nikki Sabourin-Gibbs, CHU Rouen, for her help in editing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.” “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Beavers, C.J.; Naqvi, I.A. Clopidogrel. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Roden, D.M.; McLeod, H.L.; Relling, M.V.; Williams, M.S.; Mensah, G.A.; Peterson, J.F.; Van Driest, S.L. Pharmacogenomics. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2019, 394, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trenk, D.; Hochholzer, W. Genetics of Platelet Inhibitor Treatment. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 77, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, T.; Danchin, N. Clinical Impact of Pharmacogenomics of Clopidogrel in Stroke. Circulation 2017, 135, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, W.; Xu, Y.; Yi, X.; Han, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, X.; Huang, L.; Johnston, S.C.; Zhao, X.; et al. Genetic Polymorphisms and Clopidogrel Efficacy for Acute Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2017, 135, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizzi, C.; Dalabira, E.; Kumuthini, J.; Dzimiri, N.; Balogh, I.; Başak, N.; Böhm, R.; Borg, J.; Borgiani, P.; Bozina, N.; et al. A European Spectrum of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers: Implications for Clinical Pharmacogenomics. PloS One 2016, 11, e0162866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.R.; Luzum, J.A.; Sangkuhl, K.; Gammal, R.S.; Sabatine, M.S.; Stein, C.M.; Kisor, D.F.; Limdi, N.A.; Lee, Y.M.; Scott, S.A.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for CYP2C19 Genotype and Clopidogrel Therapy: 2022 Update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 112, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Very Important Pharmacogene: CYP2C19. Available online: https://www.pharmgkb.org/vip/PA166169770/overview (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Mao, L.; Jian, C.; Changzhi, L.; Dan, H.; Suihua, H.; Wenyi, T.; Wei, W. Cytochrome CYP2C19 Polymorphism and Risk of Adverse Clinical Events in Clopidogrel-Treated Patients: A Meta-Analysis Based on 23,035 Subjects. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 106, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden, D.M. Clopidogrel Pharmacogenetics - Why the Wait? N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1677–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnin, P.; Legrand, J.; Husson, G.; Ringot, P.; Tchechmedjiev, A.; Jonquet, C.; Napoli, A.; Coulet, A. PGxO and PGxLOD: A Reconciliation of Pharmacogenomic Knowledge of Various Provenances, Enabling Further Comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 2019, 20, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressat-Laffouilhère, T.; Balayé, P.; Dahamna, B.; Lelong, R.; Billey, K.; Darmoni, S.J.; Grosjean, J. Evaluation of Doc’EDS: A French Semantic Search Tool to Query Health Documents from a Clinical Data Warehouse. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, J.H.; Leach, M.; Sen, D.; Smith, C.J.; Newman, W.G.; Bath, P.M. The Role of CYP2C19 Genotyping to Guide Antiplatelet Therapy Following Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 15, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, K.; Nguyen, T.N.; Appleton, J.P.; Law, Z.K.; Caulfied, M.; Cabrera, C.P.; Lenthall, R.; Hewson, D.; England, T.; McConachie, N.; et al. Antiplatelet Resistance: A Review of Concepts, Mechanisms, and Implications for Management in Acute Ischemic Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack. Stroke Vasc. Interv. Neurol. 2023, 3, e000576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavers, C.J.; Naqvi, I.A. Clopidogrel. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; You, J.H.S. Review of Pharmacoeconomic Evaluation of Genotype-Guided Antiplatelet Therapy. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2015, 16, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.G.; Lee, S.J.; Heo, S.H.; Chang, D.-I.; Kim, B.J. Clopidogrel Resistance in Patients With Stroke Recurrence Under Single or Dual Antiplatelet Treatment. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 652416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, M.; Benenati, S.; Capodanno, D.; Franchi, F.; Rollini, F.; D’Amario, D.; Porto, I.; Angiolillo, D.J. Guided versus Standard Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2021, 397, 1470–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoureux, F.; Duflot, T. ; French Network of Pharmacogenetics (RNPGX) Pharmacogenetics in Cardiovascular Diseases: State of the Art and Implementation-Recommendations of the French National Network of Pharmacogenetics (RNPGx). Therapie 2017, 72, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, N.L.; Rihal, C.S.; So, D.Y.F.; Rosenberg, Y.; Lennon, R.J.; Mathew, V.; Goodman, S.G.; Weinshilboum, R.M.; Wang, L.; Baudhuin, L.M.; et al. Clopidogrel Pharmacogenetics. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, e007811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMukdad, S.; Elewa, H.; Arafa, S.; Al-Badriyeh, D. Short- and Long-Term Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of CYP2C19 Genotype-Guided Therapy, Universal Clopidogrel, versus Universal Ticagrelor in Post-Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Patients in Qatar. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 331, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Charitakis, K.; Swaminathan, R.V.; Feldman, D.N. Novel Antiplatelet Therapies. 2011, 14. [CrossRef]

- Claassens, D.M.F.; Vos, G.J.A.; Bergmeijer, T.O.; Hermanides, R.S.; van ’t Hof, A.W.J.; van der Harst, P.; Barbato, E.; Morisco, C.; Tjon Joe Gin, R.M.; Asselbergs, F.W.; et al. A Genotype-Guided Strategy for Oral P2Y12 Inhibitors in Primary PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1621–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudhuin, L.M.; Train, L.J.; Goodman, S.G.; Lane, G.E.; Lennon, R.J.; Mathew, V.; Murthy, V.; Nazif, T.M.; So, D.Y.F.; Sweeney, J.P.; et al. Point of Care CYP2C19 Genotyping after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Pharmacogenomics J. 2022, 22, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, J.H.; Wright, S.; Sharma, V.; Newman, W.G.; Payne, K.; Wilson, P. Characterizing Pharmacogenetic Programs Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: A Structured Scoping Review. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 945352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, J.K.; Dunnenberger, H.M.; Gumpper, K.F.; Haidar, C.E.; Hoffman, J.M. Integrating Pharmacogenomics into Electronic Health Records with Clinical Decision Support. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. AJHP Off. J. Am. Soc. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2016, 73, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).