1. Introduction

III-V semiconductors are widely recognized as some of the most significant basic materials for the development of light-emitting devices worldwide, due to their exceptional capabilities.[

1] Nevertheless, semiconductor industry is searching for novel light emitting materials due to the high toxicity of current semiconductors and some of their alternatives, especially those based on arsenic,[

2] gallium,[

3] or lead.[

4] In addition, the production of indium, which is a common element appearing in III-V semiconductors, is highly dependent on the fluctuations of other metals markets as it is only obtained as a by-product of other metal ores processing.[

5] Apart from that, rare earth elements, which appear in the composition of current phosphors, have been classified as critical raw materials by several international organizations, which have recommended lessening their usage in the industry.[

6,

7] All of these factors have intensified the search for novel semiconductor compounds, which may overcome most of these drawbacks.

Ternary oxides, particularly those based on ZnO and TiO

2, have emerged as some of the most promising candidates to replace current light-emitting semiconductors, fulfilling all previous requirements. Furthermore, various synthesis methods can be employed to prepare oxide nanophosphors with an up to standard purity and crystallinity with controlled morphologies and particle sizes, which can be easily tuned by simply modifying synthesis conditions.[

8,

9,

10,

11]

Among these materials, bulk Zn

2GeO

4 emits in the blue-green region, peaking at 2.39 eV. Nevertheless, its photoluminescence can be considered rather complex as it is the contribution of three different signals, whose maxima occur at 2.28, 2.38 and 2.73 eV respectively.[

12] DFT calculations attribute the luminescence of Zn

2GeO

4 to Zn 3d orbitals and the presence of native defects such as oxygen vacancies and zinc interstitials.[

13,

14] However, Zn

2GeO

4 nanoparticles emit different wavelengths depending on their morphology and particle size.[

15] In particular, hexagonal microrods emit at 2.03, 2.40 and 2.86 eV,[

16] nanowires at 1.89, 2.11 and 2.34 eV,[

17] whilst small nanoparticles present luminescence signals at 2.4, 2.7 and 3.1 eV.[

18] Therefore, such remarkable variations imply that morphology may affect Zn

2GeO

4 luminescence. Nevertheless, information about the optical properties of more types of undoped Zn

2GeO

4 particles is fairly limited. Covering a broader range of nanoparticle shapes and sizes may help to correlate the emitted light with different characteristic features of Zn

2GeO

4 crystallites with the ultimate goal of generating toxic-free nanophosphors with tunable properties.

Several studies have reported the preparation of Zn

2GeO

4 nanoparticles with a myriad of morphologies employing diverse synthetic methods. Solvothermal and hydrothermal procedures stand out among these methodologies due to the fine morphological and particle size control they provide. In particular, numerous articles report the solvothermal synthesis of Zn

2GeO

4 nanorods, commonly applied as photocatalysts,[

19,

20] for biosensing,[

21] and for lithium batteries.[

22,

23] Apart from that, Zn

2GeO

4 ultrathin nanoribbons [

24] can also be obtained following a hydrothermal method, while other procedures can be employed to prepare Zn

2GeO

4 with different morphologies: CVD (nanowires),[

25,

26,

27,

28] ceramic (polycrystals),[

29] template-assisted method (hollow spheres),[

30] etc.

In this article we report the reproducible hydrothermal synthesis of short Zn2GeO4 nanorods for light-emitting applications. An exhaustive structural, morphological and luminescence characterization was conducted, which allowed us to correlate the optoelectronic properties of this material with its morphological aspects, which is of maximum importance for its possible technological applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis

Zn2GeO4 nanoparticles were synthesized following a conventional hydrothermal method. The stoichiometric amounts GeO2 (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.9%) were dissolved in a 0.33 M NaOH solution (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%) under continuous stirring. The corresponding amount of a Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O (Merck, 99.5%) solution was added dropwise and the resulting mixture was poured into a Teflon-line stainless steel autoclave. The autoclave was introduced in an oven for 12h at 100oC. The as-obtained white precipitate was centrifuged, washed several times with water until pH = 7, and dried overnight. The synthesis was carried out several times to verify the reliability of the results obtained.

2.2. Structural characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed in a Bruker D8 ADVANCE A25 diffractometer using a Cu tube in Bragg-Brentano optics with fixed slits, Ni filter and a position sensitive LynxEye SSD160-2 detector. Patterns were recorded within the 2θ range of 5−80°, using a step size of 0.01° and a collection time of 1 s per step.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) experiments were conducted in a JEOL JEM 2100 microscope, located in the facilities of the National Center of Electron Microscopy (ICTS-CNME). The spatial resolution achieved operating at 200 kV in High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy mode (HRTEM) is 0.25 nm.

2.3. Photoluminescence measurements

A Horiba Jobin Ybon LabRaman Hr800 confocal microscope using a 325nm He-Cd laser as excitation source was used for photoluminescence (PL) measurements at room temperature (RT). An Edinburgh Instruments FLS1000 system, equipped with a 450W Xe lamp and a helium cryostat, was employed for acquiring photoluminescence-photoluminescence excitation (PL-PLE) spectra from 4K up to RT.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structural and morphological chacacterization

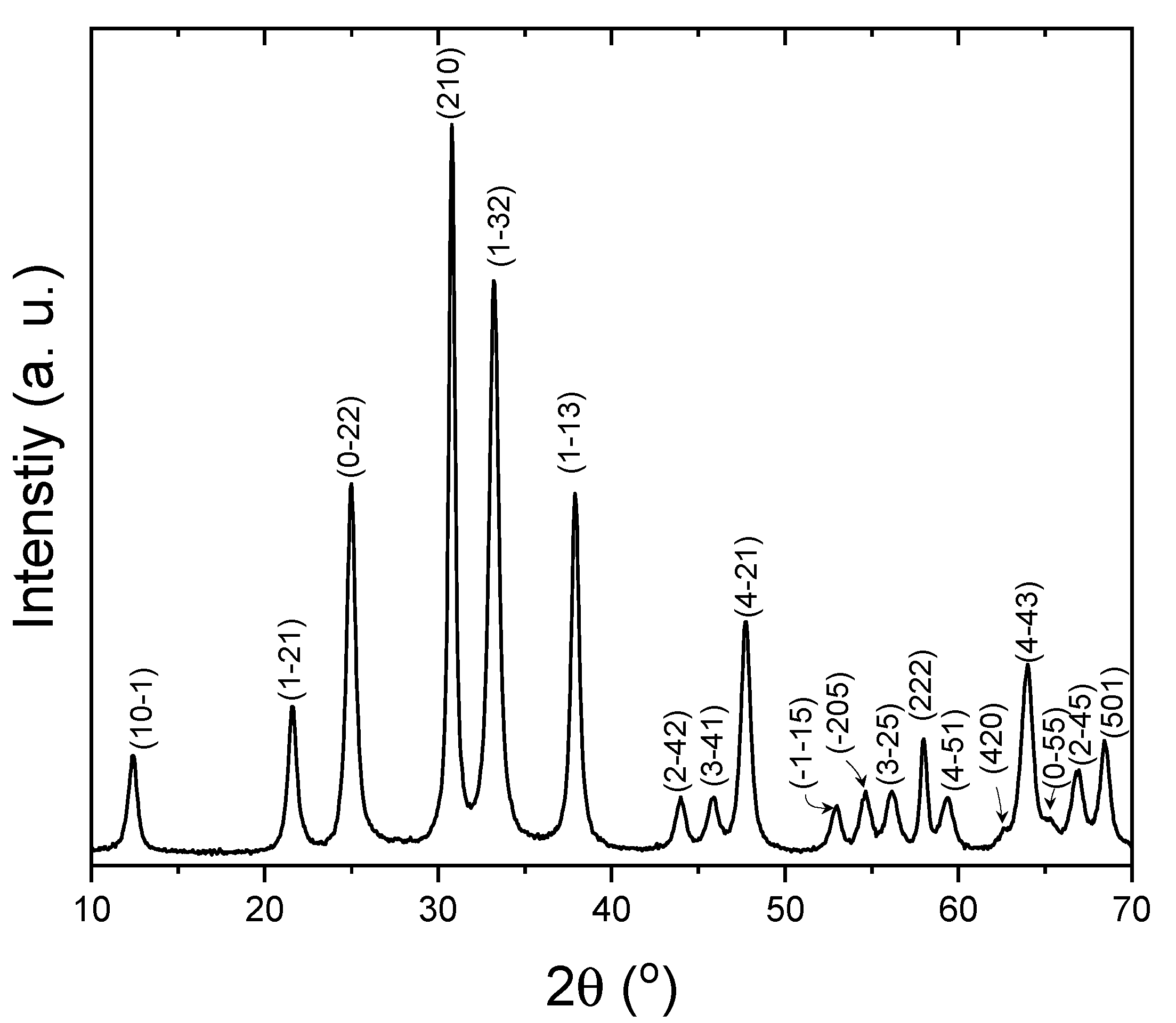

XRD was carried out in the as-synthesized nanoparticles, whose diffraction pattern is displayed in

Figure 1. All the diffraction peaks were perfectly indexed on the rhombohedral space group R-3 basis of Zn

2GeO

4 (ICSD Collection Code: 68382), with cell parameters a = b = 14.28 Å and c =9.55 Å. This diffractogram clearly shows that nanocrystals possess a willemite-like structure[

31] compared to the Zn

2GeO

4 reference, where the structure can be described as formed of tetrahedrally coordinated zinc and germanium atoms, sharing corners.[

32] The absence of additional reflections, which could be attributed to impurities, is indicative of the remarkable purity of the Zn

2GeO

4 sample, even without the need for high-temperature thermal treatments. The relative wide maxima suggest the nanoparticle nature of the material.

The average crystal size has been calculated from the values of the form factor K, the wavelength of the incident radiation λ, the full width at half maximum B, of the diffraction maximum {210}, and the diffraction angle θ, along with Scherrer formula: D = K·λ/(B·cosθ). The mean value is 17 ± 0.02 nm.

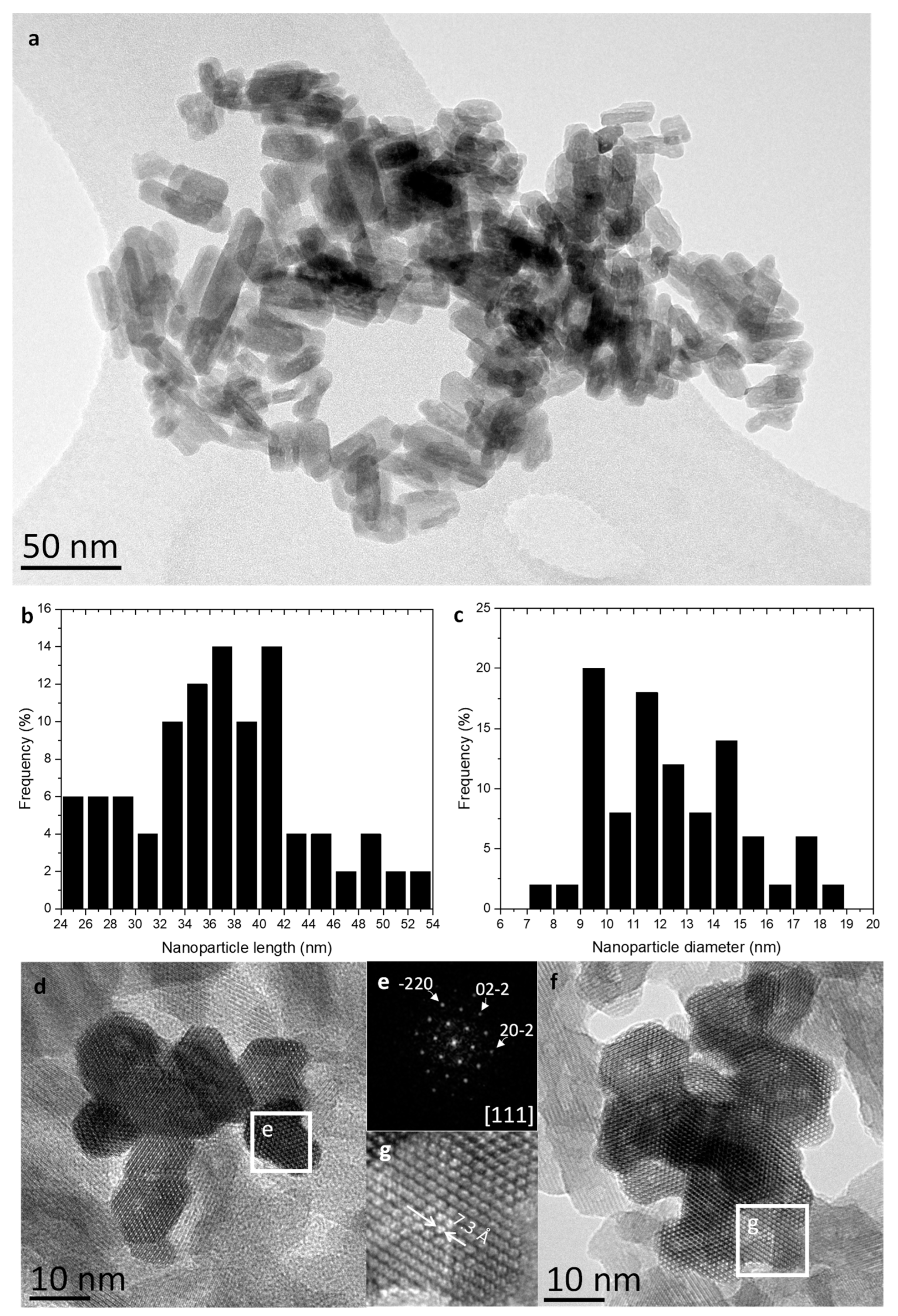

To confirm these results, transmission electron microscopy studies have been carried out. The low-magnification TEM image depicted in

Figure 2a evidence that most nanoparticles possess a short rod-like morphology. Particle length and diameter distributions are presented in

Figure 2b and c, revealing their small size. Specifically, particle length ranges between 24 and 54 nm with an average length of 37 ± 7 nm, whilst their mean diameter stands at 13 ± 3 nm, varying from 7 to 19 nm.

In addition, the study by high-resolution electron microscopy (HRTEM) confirms the structure of the Zn

2GeO

4. Figure 2d and f depict the electron micrograph top-view images of representative agglomerates of Zn

2GeO

4 nanocrystals oriented along the [111] zone axis. As suggested by these images, the radial morphology of these rod-like nanoparticles is greatly varied, but numerous cross-sections present 60

o and 120

o angles. Therefore, some of these nanoparticles may derive from distorted hexagonal and truncated triangular prismatic nanocrystals.

The digital diffraction pattern (DDP), extracted from one of the crystals (

Figure 2e) clearly show the perfect willemite-like lattice of the nanocrystals. The reflections distances and angles measured are 3.6 Å at 60

o, corresponding to {-220}, {02-2} and {20-2} planes oriented along a [111] zone axis. On the other hand, the characteristic tunnels, inherent to the willemite structure and parallel to the [111]-axis direction, can be readily discerned in

Figure 2g, which depicts a magnified region from

Figure 2f. The experimental diameter of the tunnels has been estimated using HRTEM images, and the measured values are approximately 7.3 Å, in accordance with the structure described for this oxide. [

31]

3.2. Optical characterization of the nanoparticles

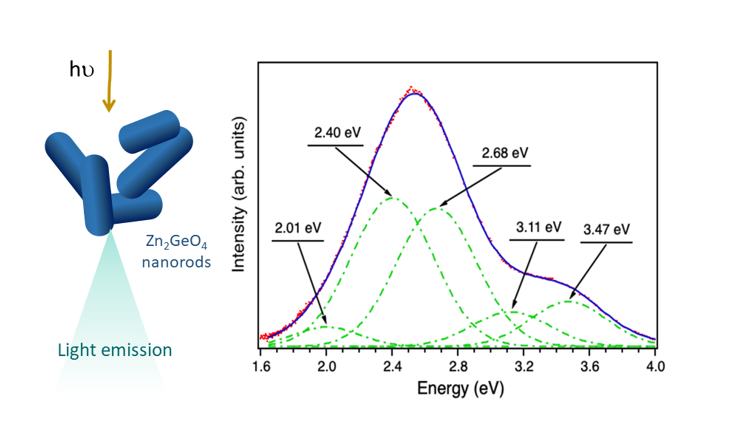

An in-depth study of the luminescence emission of the as-synthesized Zn

2GeO

4 nanoparticles was carried out. An analysis of the emission provides information about the electronic recombinations between conduction and valence bands or between the electronic levels caused by native defects within the bandgap. As a first step, room temperature luminescence of these Zn

2GeO

4 nanocrystals has been assessed.

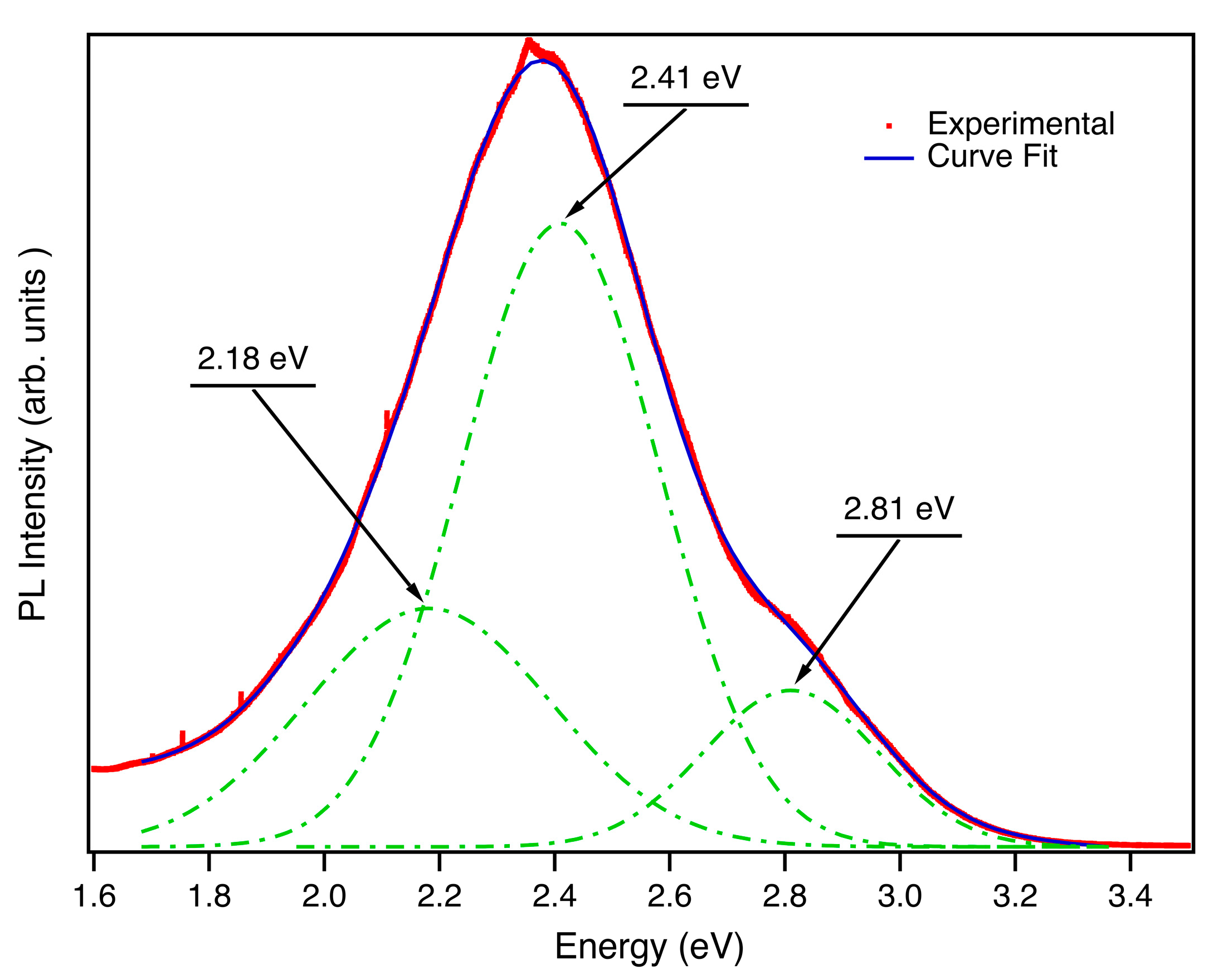

Figure 3 shows the room temperature luminescence spectrum acquired with an He-Cd laser (λ= 325 nm). A broad visible band covering practically the whole visible range is observed. PL spectra agree with the complex nature of the luminescence band involving several radiative centers. The broad luminescence emission can be deconvoluted intro three components (2.18 eV, 2.41 eV and 2.81 eV)

, as previously reported in other Zn

2GeO

4 nanoparticles growth by a different synthesis method.[

18] The green-yellow broad band whose maximum is centered at 2.41 eV is the dominant contribution to the luminescence of this material. Li and co-workers [

33] have suggested that this complex band is related to Ge centers (bands peaked at 2.18 eV and 2.41 eV) and oxygen defects (band peaked at 2.8 eV). These emission contributions are very close to the ones reported for microrods,[

16] and rather distinct to Zn

2GeO

4 nanoparticles, nanowires and Zn

2GeO

4 in bulk form. [

15,

17,

18] Hence, our results evidence that particles with similar morphologies, but clearly different particle sizes (nanorods and microrods) possess an analogous phosphor emission, which reinforces the relevant effect of morphology on the light emission efficiency of Zn

2GeO

4.

To understand better the origin of these emission bands, PL and PLE spectra were acquired at RT and at low temperature (4K).

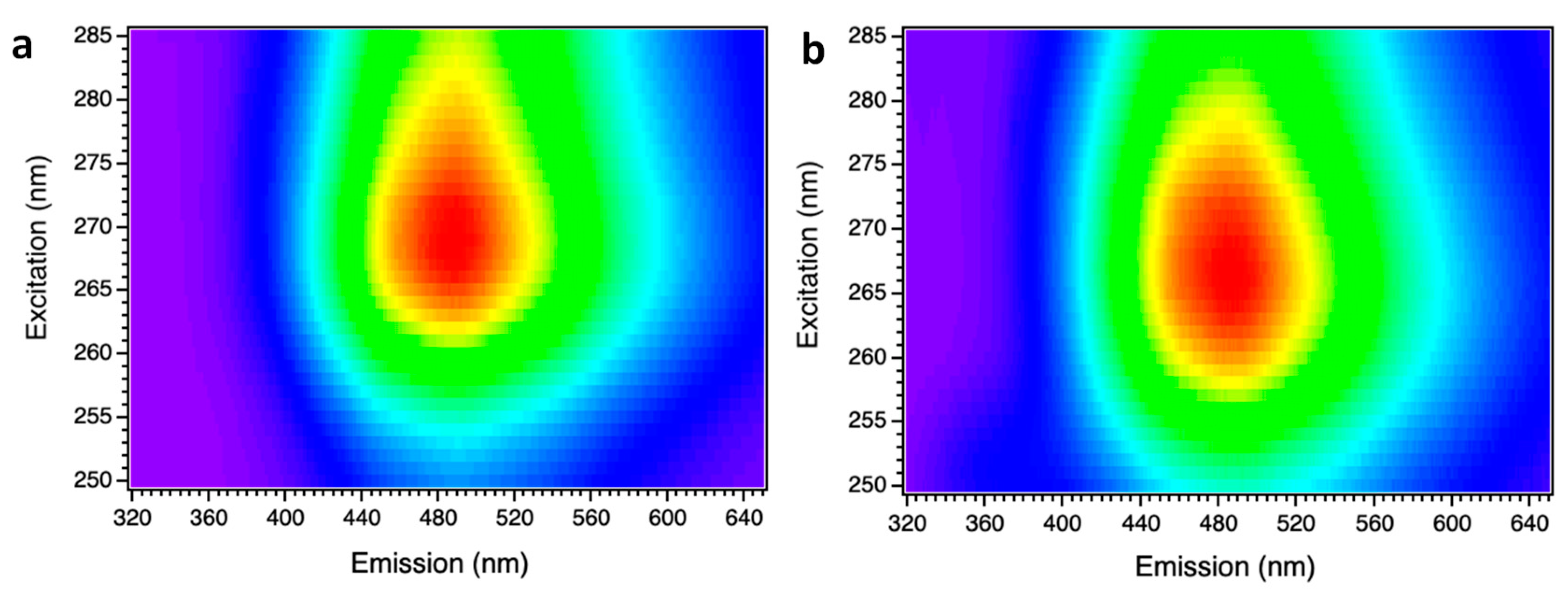

Figure 4 shows two PL-PLE maps:

Figure 4a recorded at RT, and

Figure 4b at 4K. In both cases, spectra were collected varying the excitation wavelength between 250-285 nm (4.96 – 4.35 eV) in order to ensure an excitation energy over, or close to the bandgap energy to be used, while the light emitted was recorded between 320-650 nm (3.88 – 1.9 eV).

Analyzing the data from these emission maps, a broadening of the emission spectra occurs as temperature increases. Furthermore, it can be observed that the maximum emission of the sample occurs with an excitation in the range of 265-270 nm for 4K, and that this range increases to 260-280 nm when the sample is at RT. Using an excitation with an energy above the gap of the material produces an UV emission increase centered between 320 and 400 nm. Additionally, it is possible to observe how this emission decreases due to a reduction in the gap of the material when temperature rises.

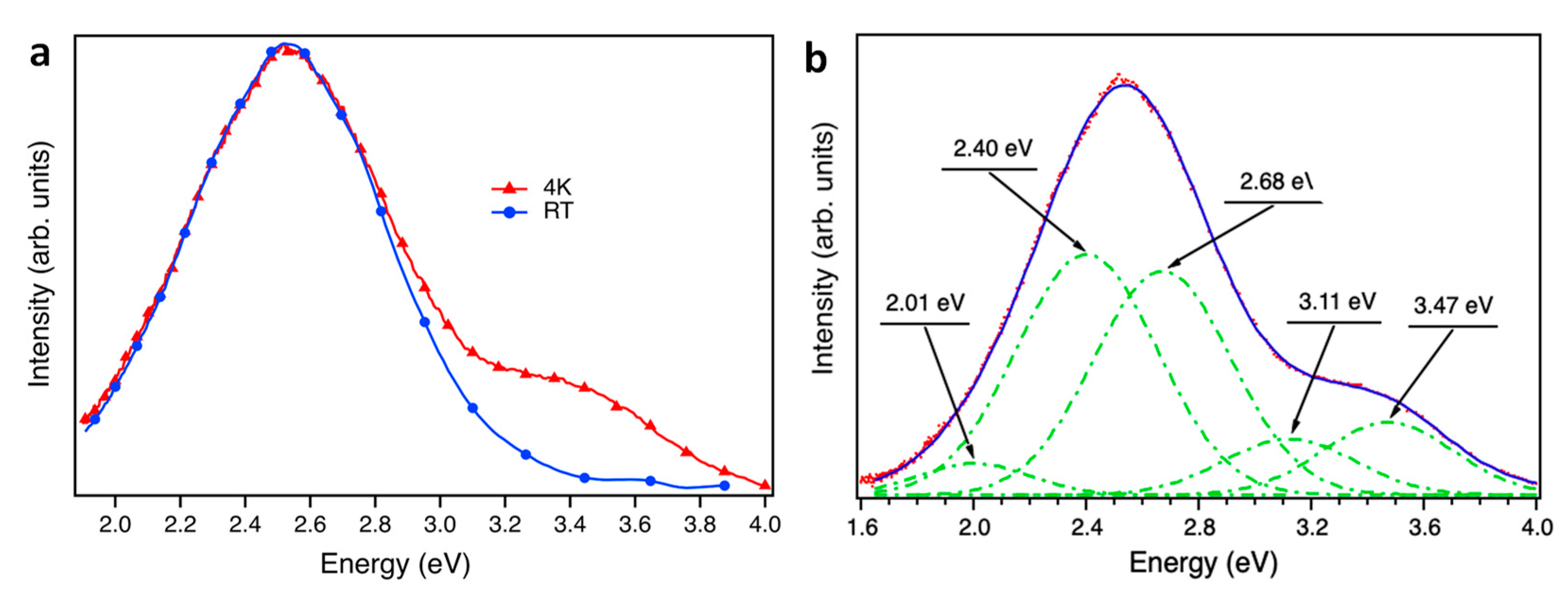

Figure 5 shows emission spectra at RT and at 4K, acquired on the sample from 320 to 650 nm with an excitation wavelength of 250 nm in order to ensure an excitation energy over the bandgap energy.[

18] At this excitation energy, a relatively intense emission centered at 3.4 eV is observed, which has been previously attributed to a recombination of V

O level electrons, acting as donor centers, with valence bands holes.[

12] Therefore, the intensity of this band is directly related to oxygen vacancies. The broad feature observed in

Figure 5a is not composed by a unique emission band as it is shown in

Figure 5b. Deconvolution of the PL spectrum at 4K shows that it is composed of five gaussian emissions: three in the visible range (2.19 eV, 2.53 eV and 2.80 eV) and two gaussian emissions in the ultraviolet range (3.35 eV and 3.59 eV). The intensity evolution of the PLE spectrum of these two UV bands allows us to calculate the optical band gap of the nanoparticles.

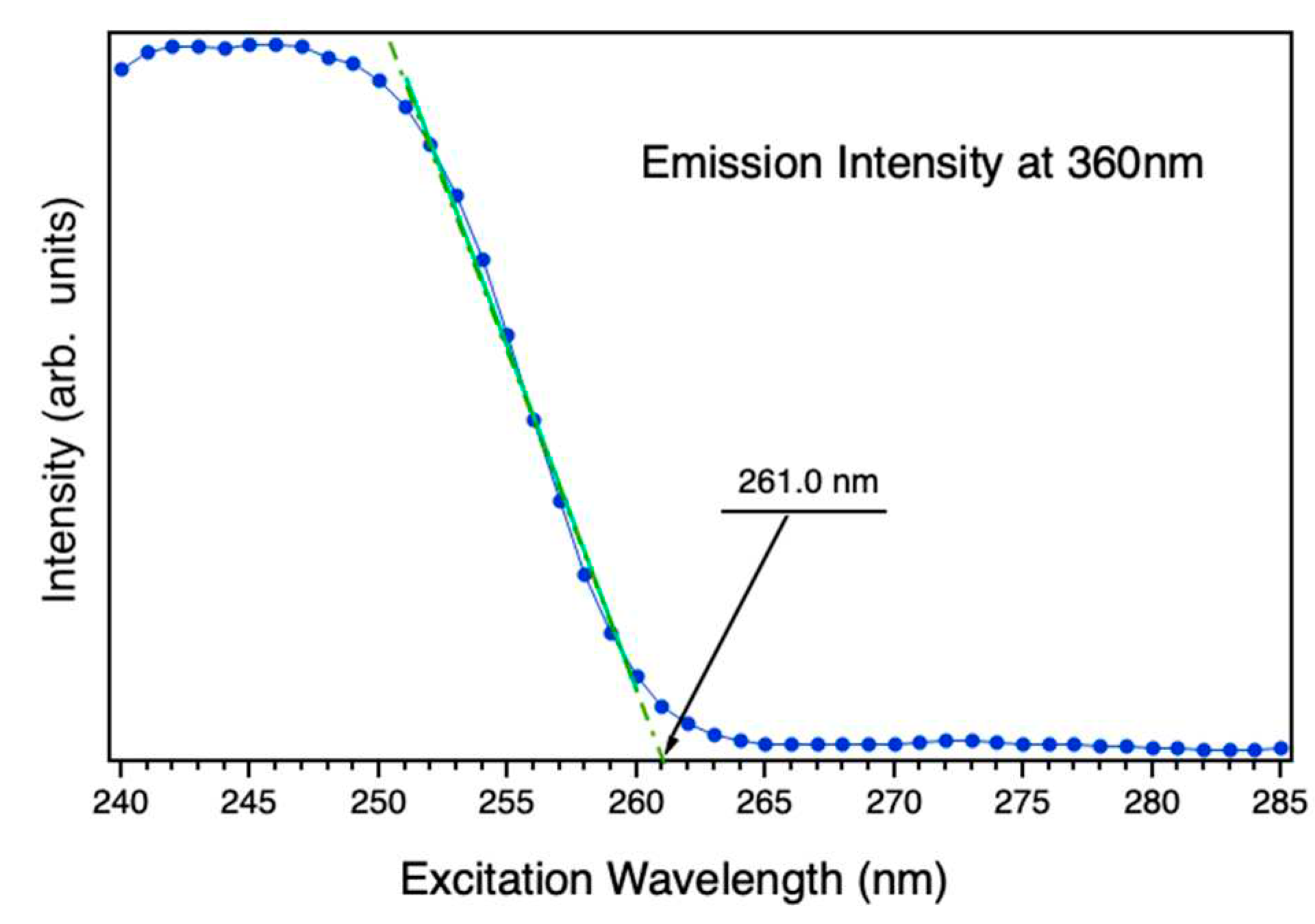

In that sense,

Figure 6 shows the intensity emission of the nanoparticles at 360nm (3.44 eV) varying the excitation wavelength from 250 nm to 285 nm. The extrapolation of the sharp PLE decay at the shortest wavelengths to a linear function provides the value of the energy bandgap. The fitting linear curve of this extrapolation is plotted by the green discontinuous line the

Figure 6. The calculated optical band gap of the nanoparticles is estimated at 4.75 eV at 4K, which is analogous to the reported for microwires (4.76 eV) and slightly larger than Zn

2GeO

4 long nanowires (4.68 eV).[

34] Nevertheless, it greatly differs from the DFT-calculated bulk Zn

2GeO

4 (4.4 eV), and is smaller than the experimental Zn

2GeO

4 thin layers band gap (4.9 ± 0.1 eV).[

35]

These results clearly evidence the influence of crystallite morphology in the optoelectronic properties of Zn2GeO4 as nanoparticles with radically different external shapes present rather distinctive optoelectronic responses.

4. Conclusions

Zn2GeO4 short nanorods were successfully prepared by a reproducible hydrothermal synthesis. Nanoparticles are homogeneous in both particle size and morphology, with no impurities. PL spectra collected at both room temperature and at 4K are rather wide, covering almost all the visible range being centered in the green-yellow region. Spectra can be deconvoluted in several emission contributions, which are attributed to native vacancies. These contributions are comparable to the ones reported for Zn2GeO4 microrods, revealing the clear influence of Zn2GeO4 morphology on its luminescence. Zn2GeO4 nanorods bandgap was estimated (4.75 eV), which is similar to the one obtained for microwires and nanowires, and clearly different from bulk Zn2GeO4. This strongly reinforces that morphology is a crucial parameter in the emission of Zn2GeO4. Further analyses will be performed to analyze oxygen and germanium vacancies in these nanorods to compare with other Zn2GeO4 morphologies with the aim to shed light onto their relationship with particle size and morphology, and their contribution to the variations in the as-observed Zn2GeO4 optoelectronic properties.

Author Contributions

MT and JRC: conceptualization; MT, JML and PH: methodology; MT and PH: formal analysis; MT and PH: investigation; MT and PH: writing – original draft preparation; MT, PH and JRC: writing – review and editing; JMGC and BM: supervision; JMGC and BM: funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through Research Projects PID 2020-113753RB-100 and PID2021-122562NB-I00.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare “The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Del Alamo, J.A. Nanometre-Scale Electronics with III-V Compound Semiconductors. Nature 2011, 479, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A. Toxicity of Indium Arsenide, Gallium Arsenide, and Aluminium Gallium Arsenide. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2004, 198, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitambar, C.R. Medical Applications and Toxicities of Gallium Compounds. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010, 7, 2337–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, M.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zeng, K.; Li, K.; Niu, G.; He, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Tang, J. Lead-Free, Blue Emitting Bismuth Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots. Angew Chem Int Ed 2016, 128, 15236–15240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfantazi, A.M.; Moskalyk, R.R. Processing of Indium: A Review. Miner Eng 2003, 16, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission First Commission Interim Report on the Implementation of Pilot Projects and Preparatory Actions 2012; 2012.

- US Department of Energy U.S. Department of Energy’s Strategy to Support Domestic Critical Mineral to Support Domestic Critical Mineral and Material Supply Chain; 2021.

- Bavykin, D. V.; Friedrich, J.M.; Walsh, F.C. Protonated Titanates and TiO2 Nanostructured Materials: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Adv Mater 2006, 18, 2807–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Berger, S.; Schmuki, P. TiO2 Nanotubes: Synthesis and Applications. Angew Chem Int Ed 2011, 50, 2904–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, C.B.; Ng, L.Y.; Mohammad, A.W. A Review of ZnO Nanoparticles as Solar Photocatalysts: Synthesis, Mechanisms and Applications. Renew Sust Energ Rev 2018, 81, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. Zinc Oxide Nanostructures: Growth, Properties and Applications. J Phys - Condensed Matter 2004, 16, R829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jing, X.; Wang, L. Luminescence of Native Defects in Zn2GeO4. J Electrochem Soc 2007, 154, H500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.Y.; Lu, H.L.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.Q.; Zhou, P.; Ding, S.J.; Zhang, D.W. The Electronic Structures and Optical Properties of Zn2GeO4 with Native Defects. J Alloys Compd 2015, 619, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolado, J.; Martínez-Casado, R.; Hidalgo, P.; Gutierrez, R.; Dianat, A.; Cuniberti, G.; Domínguez-Adame, F.; Díaz, E.; Méndez, B. Understanding the UV luminescence of zinc germanate: The role of native defects. Acta Mater 2020, 196, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Yuan, M.; Ou, K.; Zhao, W.; Tian, T.; Duan, W.; Zhang, X.; Yi, L. Controlled Preparation of Undoped Zn2GeO4 Microcrystal and the Luminescent Properties Resulted from the Inner Defects. Mater Today Commun 2021, 27, 102359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, P.; López, A.; Méndez, B.; Piqueras, J. Synthesis and Optical Properties of Zn2GeO4 Microrods. Acta Mater 2016, 104, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Huang, S.; Chen, X. Structural, Vibrational and Luminescence Properties of Longitudinal Twinning Zn2GeO4 Nanowires. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolado, J.; García-Fernández, J.; Hidalgo, P.; González-Calbet, J.; Ramírez-Castellanos, J.; Méndez, B. Intense Cold-White Emission Due to Native Defects in Zn2GeO4 Nanocrystals. J Alloys Compd 2022, 898, 162993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Low, Z.X.; Li, L.; Razmjou, A.; Wang, K.; Yao, J.; Wang, H. ZIF-8/ Zn2GeO4 Nanorods with an Enhanced CO2 Adsorption Property in an Aqueous Medium for Photocatalytic Synthesis of Liquid Fuel. J Mater Chem A Mater 2013, 1, 11563–11569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ding, K.; Hou, Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, X. Synthesis and Photocatalytic Activity of Zn2GeO4 Nanorods for the Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Water. ChemSusChem 2008, 1, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, Q.; Zheng, W.; Liu, H.; Yin, C.; Wang, F.; Chen, X.; Yuan, Q.; Tan, W. One-Dimensional Luminous Nanorods Featuring Tunable Persistent Luminescence for Autofluorescence-Free Biosensing. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 8185–8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.K.; Lai, M.O.; Lu, L. Zn2GeO4 Nanorods Synthesized by Low-Temperature Hydrothermal Growth for High-Capacity Anode of Lithium Battery. Electrochem Commun 2011, 13, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.R.; Jung, C.S.; Im, H.S.; Park, K.; Park, J.; Cho, W. Il; Cha, E.H. Zn2GeO4 and Zn2SnO4 Nanowires for High-Capacity Lithium- and Sodium-Ion Batteries. J Mater Chem A Mater 2016, 4, 10691–10699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Kou, J.; Chen, X.; Tian, Z.; Gao, J.; Yan, S.; Zou, Z. High-Yield Synthesis of Ultralong and Ultrathin Zn2GeO4 Nanoribbons toward Improved Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 into Renewable Hydrocarbon Fuel. J Am Chem Soc 2010, 132, 14385–14387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, Q.; Gan, L.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Golberg, D.; Zhai, T. High - Performance Solar-Blind Deep Ultraviolet Photodetector Based on Individual Single-Crystalline Zn2GeO4 Nanowire. Adv Funct Mater 2016, 26, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Lee, P.S. Synthesis and Structure Characterization of Ternary Zn2GeO4 Nanowires by Chemical Vapor Transport. J Phys Chem C 2009, 113, 14135–14139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Liu, F.; Li, X.; Pan, Z.W. Luminescent Zn2GeO4 Nanorod Arrays and Nanowires. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2013, 15, 7488–7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, H.; Liang, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, D.; Shen, G. Zn2GeO4 and and In2Ge2O7 Nanowire Mats Based Ultraviolet Photodetectors on Rigid and Flexible Substrates. Opt Express 2012, 20, 2982–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, F.; Wei, X.; Jiang, B.; Chen, Y.; Duan, C.; Yin, M. Luminescence Properties and the Thermal Quenching Mechanism of Mn2+ Doped Zn2GeO4 Long Persistent Phosphors. Dalton T 2018, 47, 1303–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, G.; Yu, J.C.; Guo, Y. In Situ Synthesis of Zn2GeO4 Hollow Spheres and Their Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity for the Degradation of Antibiotic Metronidazole. Dalton T 2013, 42, 5092–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breternitz, J.; Fritsch, D.; Franz, A.; Schorr, S. A Thorough Investigation of the Crystal Structure of Willemite-Type Zn2GeO4. Z Anorg Allg Chem 2021, 647, 2195–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaska, K.-H.; Eck, J.C.; Pohl, D. New Investigation of Willemite. Acta Cryst. 1978, 34, 3324–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Su, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gao, M.; Chen, Q.; Feng, Y. Syntesis and Photoluminiescence Properties of Hierarchical Zinc Germanate Nanoestructures. J Comput Theor Nanosci 2010, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C.; Singh, N.; Lee, P.S. Wide-Bandgap Zn2GeO4 Nanowire Networks as Efficient Ultraviolet Photodetectors with Fast Response and Recovery Time. Appl Phys Lett 2010, 96, 053108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Trefflich, L.; Selle, S.; Hildebrandt, R.; Krüger, E.; Lange, S.; Yu, J.; Sturm, C.; Lorenz, M.; Wenckstern, H. Von; et al. Ultrawide Bandgap Willemite-Type Zn2GeO4 epitaxial Thin Films. Appl Phys Lett 2023, 122, 031601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).