Introduction

Semiconductor metal oxides have attracted considerable attention over the past decades due to their unique combination of chemical stability, abundance, and tunable physical properties. Among them, zinc oxide (ZnO) stands out as one of the most studied n-type semiconductors, owing to its wide direct band gap (~3.2 eV), high exciton binding energy (~60 meV), and high transparency in the visible range1. These properties make ZnO a highly versatile material for a broad range of technological applications, including gas sensors2, UV photodetectors3, field-effect transistors4, solar cells5, light-emitting diodes (LEDs)6, and biomedical devices7. Moreover, ZnO is environmentally friendly, thermally stable, and cost-effective, reinforcing its attractiveness for industrial-scale implementation1.

The performance of ZnO in optoelectronic and electronic devices can be significantly improved through defect engineering and intentional doping. Intrinsic defects, such as oxygen vacancies and zinc interstitials, can strongly influence the electronic and optical behavior of ZnO. However, these defects are often difficult to control, which limits reproducibility and performance predictability. In this context, aliovalent doping emerges as a powerful approach to tailor ZnO's properties, particularly by incorporating trivalent cations such as Al³⁺, Ga³⁺, and In³⁺ into the Zn²⁺ lattice sites. These dopants introduce additional free electrons into the conduction band, enhancing the material's conductivity and modifying its band structure. Among the group III elements, aluminum is the most commonly used dopant due to its low cost, favorable ionic radius (0.53 Å for Al³⁺ vs. 0.60 Å for Zn²⁺), and effectiveness in improving ZnO's electrical and optical performance8.

Aluminum-doped ZnO (AZO) has emerged as a compelling alternative to indium tin oxide (ITO), a widely used transparent conducting oxide (TCO) material9. ITO presents excellent electrical conductivity and optical transparency, but the scarcity and high cost of indium raise sustainability and economic concerns. In contrast, AZO offers comparable properties with significantly lower cost and abundant elemental availability, making it a strong candidate for next-generation transparent electrodes in displays, touchscreens, solar cells, and smart windows9. Furthermore, AZO's compatibility with flexible substrates and its chemical robustness provide additional advantages in emerging applications, such as wearable electronics and flexible photovoltaics10-12.

To fully exploit the potential of AZO, it is critical to optimize its synthesis conditions and structural properties. The choice of synthesis route directly affects the dopant distribution, crystallite size, morphology, defect concentration, and phase purity—all of which play a central role in determining the final properties of the material. A wide variety of chemical and physical methods have been employed for the synthesis of AZO, including sol–gel, chemical vapor deposition (CVD)13, pulsed laser deposition (PLD)14, sputtering, and hydrothermal techniques15. Among these, hydrothermal synthesis stands out due to its low cost, scalability, and ability to produce nanostructured materials with controlled morphology under mild reaction conditions.

The hydrothermal method involves the crystallization of materials from aqueous solutions at elevated temperatures and pressures, typically within a sealed autoclave. This method allows precise control over nucleation and growth processes by adjusting parameters such as temperature, precursor concentration, pH, and reaction time. It also enables the formation of nanoparticles with high crystallinity and uniform shape, which are essential characteristics for optical and electronic applications. Notably, hydrothermal synthesis is a bottom-up approach, starting from molecular or ionic precursors, and allows doping at the atomic level during the crystal growth process.

Recent advances in hydrothermal synthesis include the use of microwave-assisted heating, which has demonstrated significant improvements in reaction kinetics, energy efficiency, and particle uniformity. Microwave heating induces rapid volumetric heating of the reaction medium, leading to homogeneous nucleation and faster crystallization compared to conventional convective heating. The high heating rates and localized superheating effects reduce particle aggregation and promote narrow size distribution, which are highly desirable for functional nanomaterials. In addition, microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis (MAHS) is considered a green synthesis approach due to its lower energy consumption and shorter processing times16.

Given the growing interest in sustainable, low-cost, and scalable methods for fabricating transparent conducting oxides, the development of optimized hydrothermal routes for AZO synthesis is both timely and relevant. The combination of microwave-assisted synthesis with controlled Al doping represents a promising pathway to tailor the physical properties of ZnO nanoparticles for targeted optoelectronic applications. In addition, gaining a deeper understanding of how heating mode and dopant concentration influence the structural and optical characteristics of AZO is essential for advancing the design of next-generation TCOs.

In this study, it is reported the hydrothermal synthesis of pure and Al-doped ZnO nanoparticles using both conventional heating and microwave-assisted methods in aqueous solution. We compare the effects of the two heating modes on the phase composition, crystallinity, morphology, and band gap of the resulting nanomaterials. Particular attention is given to the analysis of Al incorporation and its influence on the material’s structural integrity and defect landscape. By combining multiple characterization techniques, we provide a comprehensive understanding of how synthesis parameters affect the functional properties of AZO nanoparticles. This study contributes to the rational design of doped metal oxide nanostructures and offers practical guidelines for tuning their properties via scalable, energy-efficient methods.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of Pure and Aluminum-Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles by Conventional Hydrothermal Heating Route

Pure ZnO nanoparticles were synthesized by dissolving 20 mmol of zinc acetate (ZnC₄H₆O₄) in 50 mL of distilled water under magnetic stirring at room temperature until complete dissolution. Subsequently, 2 mL of ammonium hydroxide (NH₄OH) was added to the solution, which was then transferred to a sealed vessel and subjected to conventional hydrothermal treatment at 90 °C for 2 hours. The resulting precipitate was washed three times by centrifugation, followed by removal of the supernatant, addition of distilled water, and redispersion in an ultrasonic bath.

For the synthesis of Al-doped ZnO (AZO) nanoparticles via the same route, the procedure was identical, except that the precursor solution also contained 0.25 mmol of aluminum acetate (C₂H₅AlO₄), corresponding to the desired Al³⁺ doping level. This Al content was chosen based on literature recommendations to optimize the trade-off between optical transmittance, band gap modulation, and electrical conductivity, especially for transparent conducting oxide (TCO) applications in photovoltaics. [

5].

Synthesis of Pure and Aluminum-Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles by Microwave-Heated Hydrothermal Route

Microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis followed the same precursor concentrations and preparation steps as the conventional method. After homogenization, the solution was transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and subjected to microwave heating at 160 °C for 40 minutes. The rapid and uniform heating provided by microwave radiation is known to accelerate nucleation and growth, enabling the formation of nanoparticles with more homogeneous size and morphology. After the reaction, the products were washed and dispersed following the same protocol used for the conventionally synthesized samples.

Results

X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

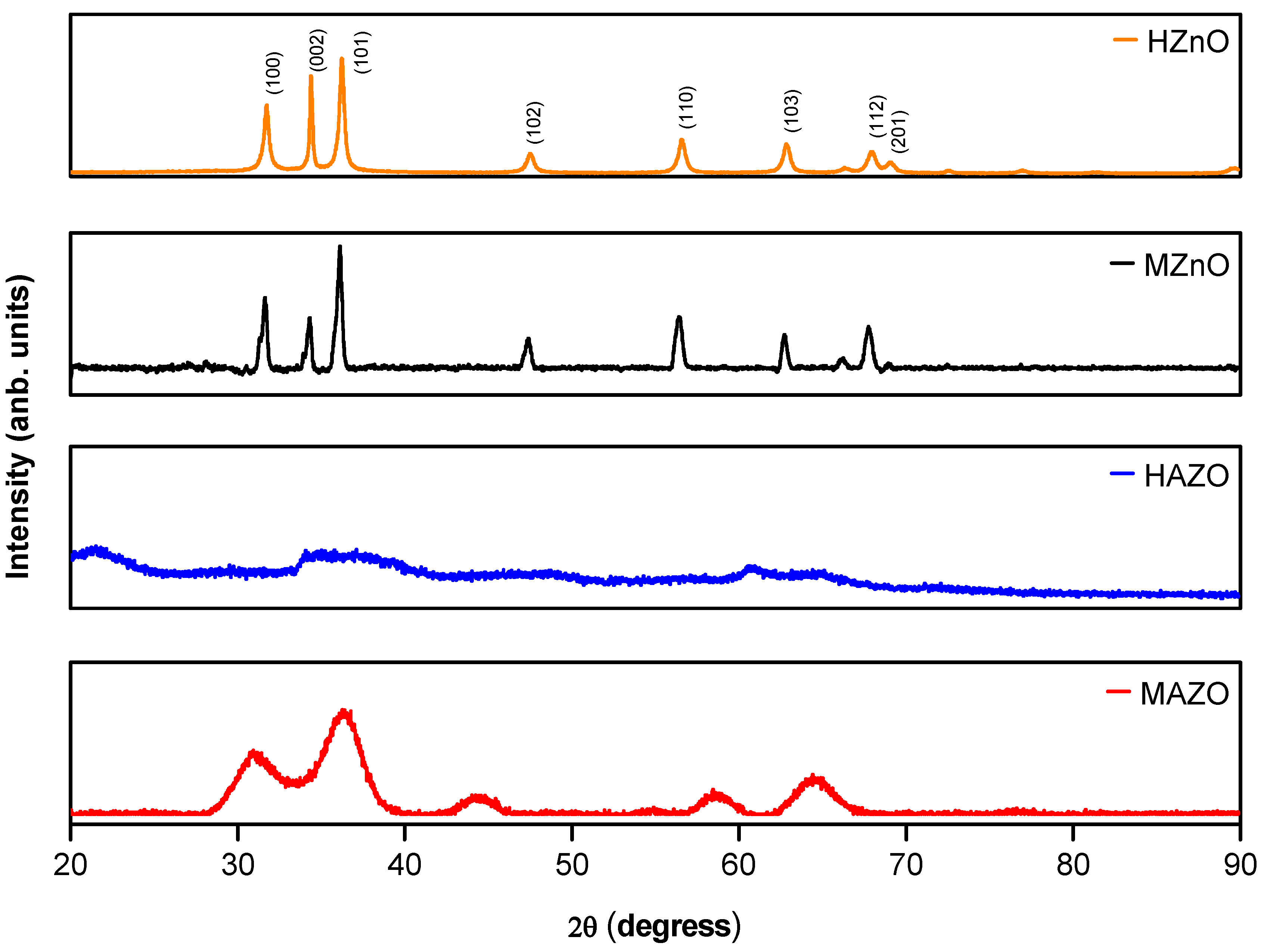

Figure 1 displays the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the ZnO samples synthesized via both conventional (HZnO and HAZO) and microwave-assisted (MZnO and MAZO) hydrothermal methods. All samples exhibit diffraction peaks corresponding to the hexagonal wurtzite structure of ZnO, with no evidence of secondary phases or impurities, indicating the successful formation of a single-phase material. The main diffraction peaks appear at 2θ values of approximately 32° (100), 35° (002), 37° (101), 48° (102), 57° (110), 63° (103), 67° (112), and 69° (201), matching the standard ZnO reference (ICSD 13953)

17.

In the doped samples (HAZO and MAZO), notable differences are observed in peak intensity and broadening, compared to their undoped counterparts. Both HAZO and MAZO present increased intensity around the (002) reflection, suggesting a preferred orientation or enhanced growth along the c-axis of the wurtzite structure. Additionally, the peak broadening observed in the doped samples indicates a decrease in crystallite size or an increase in microstrain, likely associated with the incorporation of Al³⁺ ions into the Zn²⁺ sites. The smaller ionic radius of Al³⁺ (0.53 Å) relative to Zn²⁺ (0.60 Å) may introduce local lattice distortions, affecting the long-range order of the crystal.

Microwave-assisted samples (MZnO and MAZO) exhibit broader peaks overall, which suggests the formation of smaller crystallites under microwave heating. This behavior is consistent with the rapid nucleation and limited crystal growth typically associated with microwave-induced reactions. These structural differences are critical for tuning the functional properties of AZO, as they influence electronic transport, optical absorption, and defect concentration.

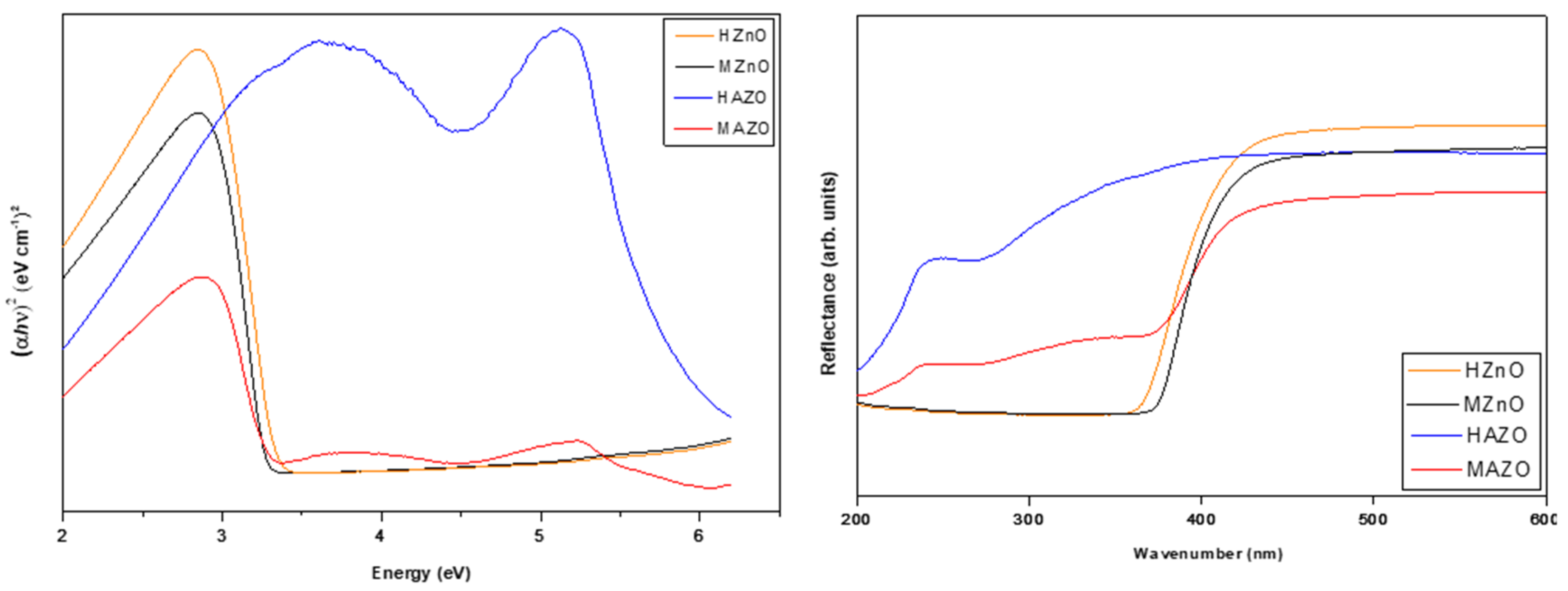

Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS)

Figure 2 shows the diffuse reflectance spectra of the four synthesized samples. The optical band gap energies were estimated using the Wood–Tauc relation, assuming a direct allowed transition. The band gap values were found to range between 3.28 and 3.43 eV. HZnO, the pure ZnO synthesized by conventional heating, exhibited the highest band gap (3.43 eV), while the doped samples (HAZO and MAZO) exhibited slightly lower values.

Although no strict monotonic trend between Al content and band gap was identified, it is evident that doping and synthesis conditions influence the optical properties. The reduction in band gap in AZO samples is commonly attributed to the Burstein–Moss effect, where the Fermi level shifts into the conduction band due to increased carrier concentration from Al doping. However, the effect of Al incorporation on band structure may also be mediated by microstructural factors such as crystallite size, particle shape, and defect states, which can vary significantly depending on the heating method.

Moreover, the slightly lower band gap of MAZO compared to HAZO may indicate more efficient Al³⁺ substitution and fewer compensating defects in the microwave-assisted route. These findings are in line with the hypothesis that microwave heating promotes more homogeneous nucleation and dopant distribution, resulting in improved control over the material’s optical and electronic characteristics.

Raman Spectroscopy

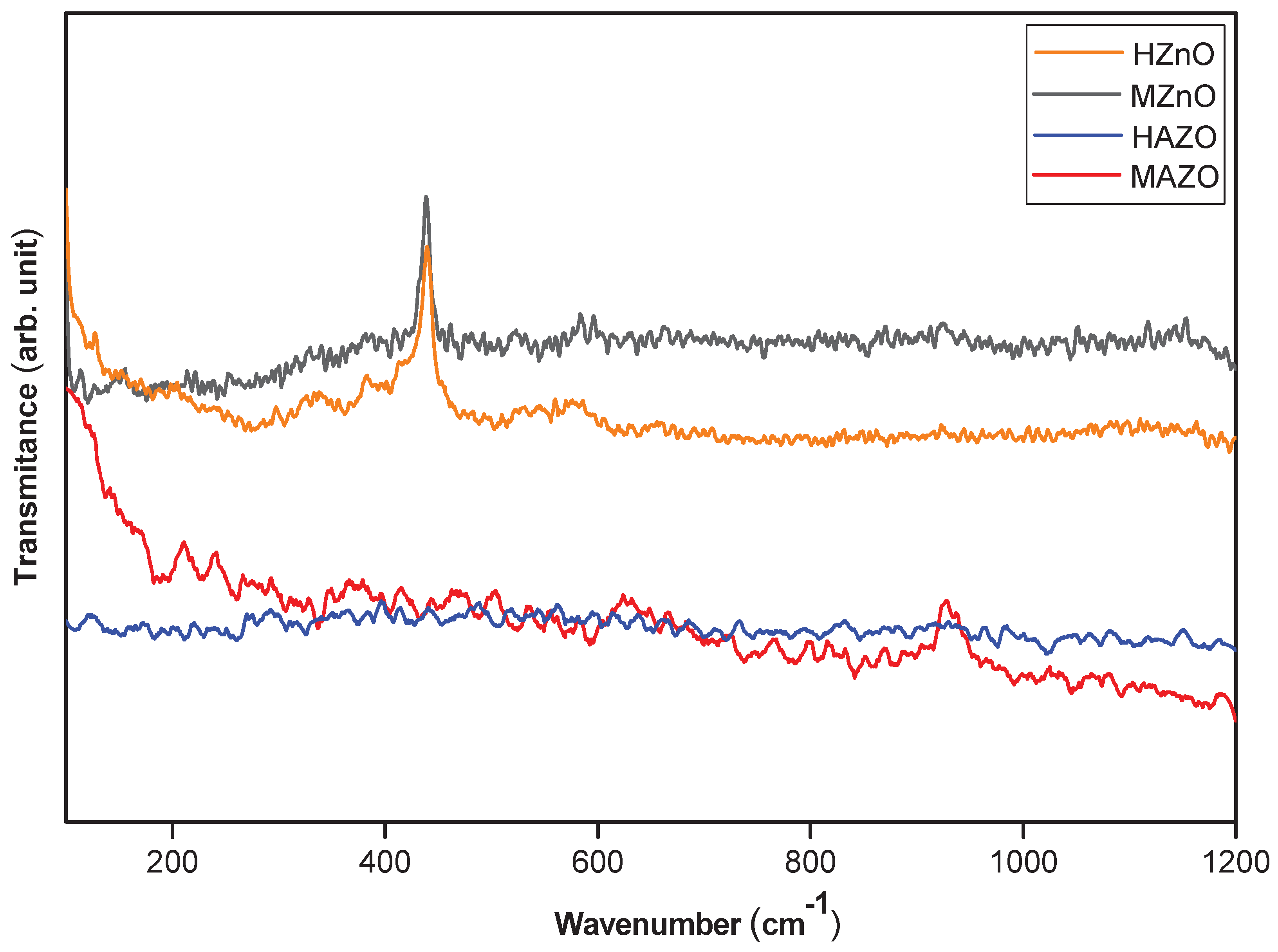

Raman spectra for all samples are shown in

Figure 4. A sharp and intense peak near 437–450 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the E₂(high) mode, which is characteristic of the wurtzite ZnO structure and indicates good crystallinity. This mode is sensitive to both crystal symmetry and strain, making it a useful probe for assessing the quality of the ZnO lattice.

In the Al-doped samples, particularly MAZO, additional weak peaks are observed at ~220, 620, and 960 cm⁻¹. These bands are not attributed to the vibrational modes of pristine ZnO and are instead related to lattice distortions, defect states, or local modes induced by Al substitution. The presence of these bands supports the hypothesis that doping alters the short-range order of the lattice and introduces new vibrational features.

Furthermore, a broad band centered around 580 cm⁻¹ is detected in all samples, with higher intensity in doped ones. This feature is commonly associated with defect-related modes, such as oxygen vacancies or zinc interstitials. These defects play a crucial role in the electrical and optical behavior of ZnO and can be intentionally modulated via doping. The more pronounced 580 cm⁻¹ band in MAZO suggests that microwave synthesis may favor the formation of intrinsic defects, which can enhance free carrier concentration and modify optical absorption.

Taken together, the Raman results confirm the preservation of the wurtzite structure upon doping and reveal structural changes associated with Al incorporation. The combination of peak shifts, broadening, and new vibrational modes corroborates the findings from XRD and FTIR and underscores the importance of synthesis parameters in tuning material quality.

Conclusions

This study reported the synthesis of pure and Al-doped ZnO (AZO) nanoparticles using a hydrothermal method, comparing conventional and microwave-assisted heating in aqueous media. The results demonstrate that both heating routes successfully produced the desired phases, with structural, spectroscopic, and optical characterizations confirming the formation of AZO nanoparticles and effective Al³⁺ incorporation into the ZnO lattice.

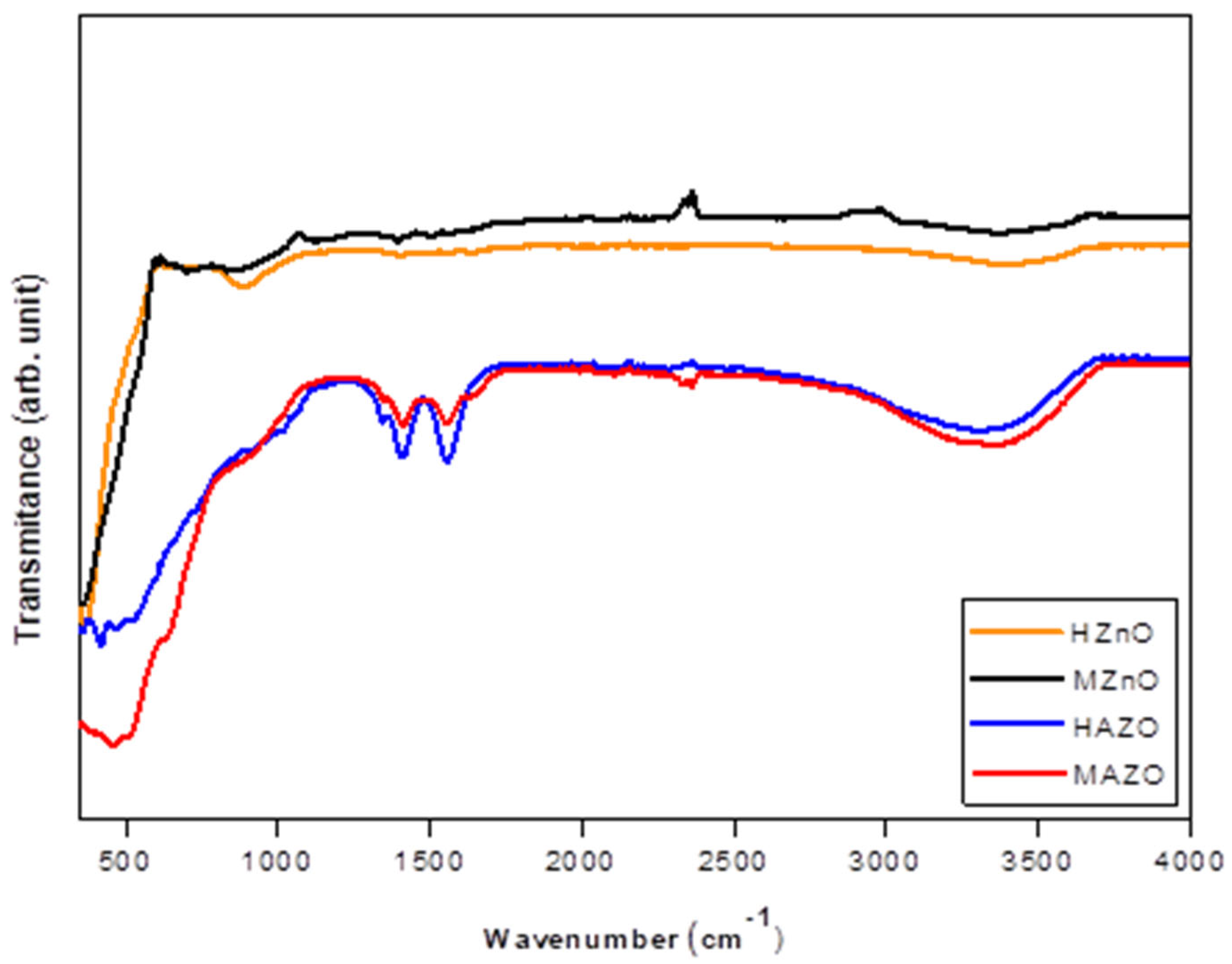

XRD analyses revealed that all samples maintained the wurtzite structure, with Al doping leading to broader peaks and reduced crystallinity, particularly in microwave-assisted samples. These observations are consistent with the smaller crystallite sizes and enhanced defect formation associated with rapid microwave-induced nucleation. FTIR and Raman spectroscopy further confirmed Al–O bond formation and the presence of structural distortions and oxygen-related defects, especially in MAZO. These defects, such as oxygen vacancies and Zn interstitials, are crucial for modulating the electronic and optical properties of AZO materials.

Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy showed band gap energies ranging from 3.28 to 3.43 eV, with higher values observed in undoped ZnO. The reduction in band gap upon doping suggests the influence of Al incorporation and associated defects, which are also supported by the Raman and FTIR data. Notably, microwave-assisted synthesis resulted in smaller, more uniform nanoparticles with a narrower size and shape distribution, which is advantageous for optoelectronic applications requiring precise control of particle morphology.

Overall, this work highlights the potential of microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis as an efficient, scalable, and environmentally friendly approach for producing high-quality AZO nanoparticles. The comparative analysis demonstrates that microwave heating not only accelerates reaction kinetics but also facilitates improved dopant incorporation and defect engineering. These findings provide valuable insights for the design of transparent conducting oxides (TCOs) with tunable properties, contributing to the advancement of next-generation optoelectronic devices.

Future work may explore the electrical characterization of AZO films derived from these nanoparticles, as well as their integration into devices such as solar cells, light-emitting diodes, and UV sensors.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) – Brazil, under Finance Code 001, and supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) – Brazil. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) and the Graduate Program in Materials Science and Engineering (PPGCEM – UFSCar) for their essential technical infrastructure and scholarly support, which significantly contributed to the successful execution of this study.

References

- Azeez, H. H.; Barzinjy, A. A.; Hamad, S. M. Structure, Synthesis and Applications of ZnO Nanoparticles: A Review. Jordan Journal of Physics 2020, 13 (2), 123-135. [CrossRef]

- Franco, M. A.; Conti, P. P.; Andre, R. S.; Correa, D. S. A review on chemiresistive ZnO gas sensors. Sensors and Actuators Reports 2022, 4. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Jiang, D. Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, X.; Duan, Y. H.; Sun, J. M.; Shan, C. C.; Li, Q.; Li, M.; Fei, X. M. Enlarged responsivity-ZnO honeycomb nanomaterials UV photodetectors with light trapping effect. Nanotechnology 2020, 31 (10). [CrossRef]

- Ditshego, N. M. J. ZnO Nanowire Field Effect Transistor for Biosensing: A Review. Journal of Nano Research 2019, 60, 94-112. [CrossRef]

- Consonni, V.; Briscoe, J.; Kärber, E.; Li, X.; Cossuet, T. ZnO nanowires for solar cells: a comprehensive review. Nanotechnology 2019, 30 (36). [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F. Zinc oxide light-emitting diodes: a review. Optical Engineering 2019, 58 (1). [CrossRef]

- Cruz, D. M.; Mostafavi, E.; Vernet-Crua, A.; Barabadi, H.; Shah, V.; Cholula-Díaz, J. L.; Guisbiers, G.; Webster, T. J. Green nanotechnology-based zinc oxide (ZnO) nanomaterials for biomedical applications: a review. Journal of Physics-Materials 2020, 3 (3). [CrossRef]

- Gurylev, V.; Perng, T. P. Defect engineering of ZnO: Review on oxygen and zinc vacancies. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2021, 41 (10), 4977-4996. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. G.; Lin, D.; Li, P.; Yang, G. C.; Liu, Y. C. ZnO transparent conducting thin films codoped with anions and cations. Chinese Science Bulletin-Chinese 2020, 65 (25), 2678-2690. [CrossRef]

- Morinigo, L. E.; Sequeira, K. M.; Vaveliuk, P.; Richard, D.; Tejerina, M. R. Aluminum-doped zinc oxide thin films: A dual approach using experimental techniques and DFT-based calculations. Materials Science and Engineering B-Advanced Functional Solid-State Materials 2025, 318. [CrossRef]

- Sweet, W. J.; Oldham, C. J.; Parsons, G. N. Conductivity and touch-sensor application for atomic layer deposition ZnO and Al:ZnO on nylon nonwoven fiber mats. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A 2015, 33 (1). [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. W.; Seo, J. W.; Park, B.; Hwang, S.; Kim, Y.; Song, P.; Shin, M.; Kwon, J. D. Flexible multi-layered coloring transparent electrode composed of AZO-based materials. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 473. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Y.; Wai, H. S. Influence of Seeds Layer on the Control of Growth and Crystallinity of AZO Films Deposited by Mist Vapor Deposition Applying for Photocatalytic Activity. Topics in Catalysis 2023, 66 (5-8), 523-532. [CrossRef]

- Anyanwu, V. O.; Moodley, M. K. PLD of transparent and conductive AZO thin films. Ceramics International 2023, 49 (3), 5311-5318. [CrossRef]

- Burunkaya, E.; Kiraz, N.; Kesmez, Ö.; Çamurlu, H. E.; Asiltürk, M.; Arpaç, E. Preparation of aluminum-doped zinc oxide (AZO) nano particles by hydrothermal synthesis. Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology 2010, 55 (2), 171-176. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Park, S. J. Conventional and Microwave Hydrothermal Synthesis and Application of Functional Materials: A Review. Materials 2019, 12 (7). [CrossRef]

- Moungsrijun, S.; Sujinnapram, S.; Sutthana, S. Synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide prepared with ammonium hydroxide and photocatalytic application of organic dye under ultraviolet illumination. Monatshefte Fur Chemie 2017, 148 (7), 1177-1183. [CrossRef]

- Anbuvannan, M.; Ramesh, M.; Viruthagiri, G.; Shanmugam, N.; Kannadasan, N. Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity of ZnO nanoparticles prepared by biological method. Spectrochimica Acta Part a-Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2015, 143, 304-308. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).