1. Introduction

Microorganisms are ubiquitous in various environments, while the soil is the habitat with the most abundant microbial diversity on the earth (Vogel et al., 2009). Soil microorganisms can play a key role in soil carbon mineralization and accumulation, which determines soil nutrient circulation and soil fertility (Zhang et al., 2019). Nevertheless, soil microbes are very sensitive to subtle environmental differences caused by environmental pressures or natural disturbances (Caporaso et al., 2012) while changes in the soil can promote biogeochemical cycles that contribute directly or indirectly to crop growth and quality, nutrient cycling, and sustainability of soil productivity (Huang et al., 2014). There is a need to assess how cultivation, fertilization, and irrigation can affect soil microbial diversity and community structure in rice paddy fields. The identifying efficient management practices in terms of improved soil microbial and nutrient status are urgently needed.

Fertilization changed soil nutrient status, such as increased soil organic carbon and total nitrogen, which provided sufficient nutrients for microorganisms and thus induces changes in soil microbial community composition (Chen et al., 2015; Xia et al., 2015). Long-term application of nitrogen fertilizer affected the composition of the rhizosphere bacterial community, and the diversity of rhizosphere bacteria increased with the increase of nitrogen application (Jorquera et al., 2014). Nitrogen fertilizer decreased the diversity of nitrification gene amoA in the paddy soil and significantly changed the community composition of amoA and hao (Chen et al., 2011). Phosphate fertilizer promoted soil phosphorus activation and release, significantly increased soil available phosphorus content, and then changed soil microbial community composition (Grover et al., 2004). The relative abundance of beneficial microorganisms under the action of phosphorus fertilizer was increased and became the dominant flora. Balanced nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilization in the rice ecosystem significantly increased bacterial diversity (Su et al., 2015). The irrigation mode directly affected the change in soil water content, while the soil microbial community structure and function were directly affected by the degree of soil water fluctuation (Meisner et al., 2018). Even the drastic fluctuation of soil moisture affected the microbial-mediated turnover of soil elements such as carbon and nitrogen, and then continuously affected subsequent soil processes and ecosystems (Manzoni et al., 2012). Dangi et al. (2016) showed that furrow irrigation significantly improved the number of gram-positive bacteria and actinobacteria, while drip irrigation significantly increased the number of fungal gram-negative bacteria. Changes in irrigation mode can significantly affect the functional diversity of soil microbial community, and the carbon sources used by soil microorganisms in flooded irrigation for a long time were mainly lipids, the carbon sources used in intermittent irrigation and moistening irrigation were mainly amino acids and sugars, respectively (Li et al., 2020). Changes in cultivation mode strongly altered the soil microenvironment mainly through soil disturbance, and then affected the structure and functional diversity of the soil microbial community (Gil et al., 2010). The combination of conventional tillage and rotary tillage to retain crop residues could help to establish a stable and functional soil environment for soil bacterial communities in double-cropping paddy fields in southern China, long-term conventional tillage and rotation contributed to the improvement of microbial richness, Shannon index, and Macintosh index (Tang et al., 2021). The microbial community structure of light and simplified direct seeding rice field and mechanized transplanting rice field was significantly different from transplanting treatment (Lin et al., 2020). Rice seedling broadcasting partially overlapped with transplanting, but the impact of four cultivation methods on the Shannon index and Simpson index of soil microorganisms did not reach a significant level

Heilongjiang Province is the main distribution area of rice in the cold region of China, and is the largest and the most important japonica rice production area. The rice planting area has reached 3.72 million hectare and the total rice yield reached 26.114 million tons in 2019 (Chen et al., 2020). In recent years, reducing the yield gap and increasing total crop yield via., integrated cultivation techniques is a hot topic in rice production. However, at present, the effect of multiple cultivation techniques on soil microbes is not clear. Therefore, it is particularly important to construct several cultivation techniques and explore how these practices change soil microorganisms and soil nutrient status. In our previous studies, we found that increased N, P, and K accumulation from the heading stage to the mature stage under HYEY and SHY treatment may contribute to increased rice yield (Lv et al., 2020). Comparing the differences in soil microbial diversity and community structure in rice fields under different cultivation methods elucidated the mechanism of rice yield difference in the cold regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Field

The experiment was carried out in the paddy field of farmers in Wangjiaweizi (46°40′N, 125°07′E), Daqing City, Heilongjiang Province in 2021 and 2022. The soil of the experimental field was sodic saline-alkali soil. The rice variety Kenjing 8 (13 leaves on the main stem) was used as the experimental material. The harvests were performed on 23 September 2021 and 25 September 2022, respectively.

2.2. Experimental Design

Experiments were performed using a randomized block design with a plot size of 150m

2 three replicates per treatment. The experiment consisted of four treatments: no N application (N0), local farmers’ practice (FP), high-yield and high-efficiency practice (HYEY), which applies alternate wetting and drying irrigation and increasing manure to improve yield and resource-use efficiency, and super-high-yield practice (to obtain a high yield regardless of labor or fertilizer input; SHY). Treatment details are given in

Table 1. Seedlings were raised using dry bed method under greenhouse conditions (with a sowing rate of 250 g/m

2 of sprouts) and pot method (with a sowing rate of 3 sprouts per pot hole). Seedlings were transplanted after 35 days of sowing with a parallel row (transplanting density 30 cm × 10 cm) and alternate wide and narrow rows planting patters [transplanting density (20-40) cm × 13.3cm]. Irrigation including shallow water flood irrigation i.e., maintained a 2-3 cm shallow water layer during whole growth period and alternate wetting and drying irrigation for example, first irrigation was 2-3 cm shallow water layer until the soil water potential reached -20 kPa (monitored the soil water potential with a negative pressure gauge, placed the bottom of the clay head at the 15 cm soil layer). After this, irrigated a 2-3 cm shallow water layer frequently during entire growth period and stopped irrigation one week before harvest (light sun drying at the end of tillering stage). Chemical fertilizers included urea (N46%), diammonium phosphate (N18%, P

2O

5 46%), potassium sulfate (K

2O 50%), nano silicon fertilizer (effective silicon ≥ 55%, manufacturer's name). Organic fertilizer was classified as compound fertilizer (N+P+K ≥ 5%, organic matter ≥ 40%). Nano-silicon fertilizer was applied to seedling bed before transplanting. Guifuji was applied as basal fertilizer. Nitrogen fertilizer was applied at 4:3:1:2 ratio during pre-transplanting, re-greening, primary tillering, panicle initiation, and spikelet differentiation stages, respectively. Phosphate fertilizer (P

2O

5) was applied as basal fertilizer. Potassium fertilizer (K

2O) was applied at the ratio of 6:4 at the pre-transplanting and panicle initiation stage, respectively. The pre-transplanting, re-greening, primary tillering, panicle initiation, and spikelet differentiation fertilizer were applied at 12d before transplanting (1 May 2021 and 4 May 2022), vegetative (19 May 2021 and 28 May 2022),8.5 leaf age (2 June 2021 and 25 June 2022) and 10.5 leaf age (6 July 2021 and 12 July 2022), respectively. Each treatment was irrigated and drained separately to prevent mutual influence. Weeds, pest and diseases were controlled.

2.3. Soil Sample Collection

At the heading stage, rhizosphere soil was collected at depth of 20 cm in 2022. Then tried to take the soil close to the root surface (mixed 3 rice plants to 1 sample for each plot). A soil sample was naturally dried, grinded and sifted by 1 mm sifter for soil chemical determination. A fresh soil sample was transported to the laboratory in the ice bags and was stored at −80 ℃ refrigerator for the determination of soil microbial diversity.

2.4. Measurement of Soil Physical and Chemical Properties

Soil organic matter content was determined by potassium dichromate volumetric method and external heating method; soil alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen content was determined by diffusion absorption method. Soil available phosphorus content was determined by extraction of sodium bicarbonate-molybdenum antimony anti-colorization method. Soil available potassium content was determined by ammonium acetate extract-AAS method (Bao, 2005). Soil microbial diversity was investigated by Biomarker Technologies Co,LTD (Shanghai). The Illumina HiSeq technique was used for samples clustering and diversity analysis.

2.5. Data Analysis

Microsoft Excel 2010 was used for data sorting, and the physical and chemical properties of soil and microbial diversity index were statistical analyzed by SPSS 17.0 software. The differences were identified statistically significant at

P<0.05 level. The bioinformatic analysis in this study was completed using the Biomarker Biocloud Platform (

www.biocloud.org, accessed on August 6, 2024).

3. Result

3.1. Effects of Integrated Cultivation Practices on Soil Nutrients in Paddy Field

Changes in available nutrients, organic matter, and pH of paddy soil under integrated cultivation practices are shown in

Table 2. The soil alkaline nitrogen content among the four treatments is in the order SHYP>HYP>FP>N0. The alkali hydrolyzed nitrogen content of SHYP and HYP was significantly higher than other treatments. Compared with N0 and FP, SHYP treatment increased alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen by 43.4% and 28.1%, while HYP treatment increased alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen by 28.2% and 14.5%, respectively. The content of available phosphorus and available potassium under N0 soil was the highest, while the content of FP was the lowest. Available potassium under HYP and SHYP was increased by 38.4% and 15.9%, respectively. SHYP significantly increased the content of soil organic matter by 25.6%, 14.9%, and 11.5% compared with N0, FP, and HYP, respectively; Compared with N0, FP, HYP, and SHYP showed a decreasing trend in soil pH.

3.2. Soil Microbial Diversity in Paddy Fields (Alpha Diversity)

Compared with FP treatment, the bacterial ACE, Chao1, and Shannon index under HYEY treatment was increased, while the Simpon index significantly decreased (

Table 3). Under SHY treatment, the bacterial ACE, Chao1, and Shannon index were decreased, while the Simpon index increased. The fungal ACE index and Chao1 index showed N0>FP>SHY>HYEY order. The fungal ACE index under FP, HYP, and SHYP treatments was significantly reduced by 30.09%, 36.12%, and 28.93% compared with N0, respectively. The Chao1 index of fungi under FP, HYEY, and SHY treatment was reduced by 30.06%, 36.50%, and 28.76% compared with N0, respectively. Fungal Simpson was in the following order HYEY>SHY>N0>FP. N0, FP, and SHY were reduced by 89.44%, 93.22%, and 87.08% compared to HYEY, respectively. The FP decreased by 35.76% compared to N0; SHY increased by 22.42% compared to N0. Integrated cultivation practices mainly affect the fungal community Alpha diversity index, bacterial community Alpha diversity index has little impact.

3.3. Correlation Analysis of Soil Nutrients and Microbial Diversity Index

Soil organic matter significantly affected bacterial ACE and Chao1, with correlation coefficients of -0.583 (

Table 4). Therefore, higher organic matter content can result in lower soil bacterial richness. However, the bacterial diversity index of Simpson and Shannon were not significantly affected by soil nutrients. Compared with bacteria, there is a certain difference in the impact of soil nutrients on fungal diversity. Fungal richness index ACE and Chao1 are significantly or extremely affected by alkaline nitrogen, available potassium, and organic matter. Soil-available potassium was the main influencing factor. However, the fungi diversity index Simpson and Shannon were not significantly affected by soil nutrients.

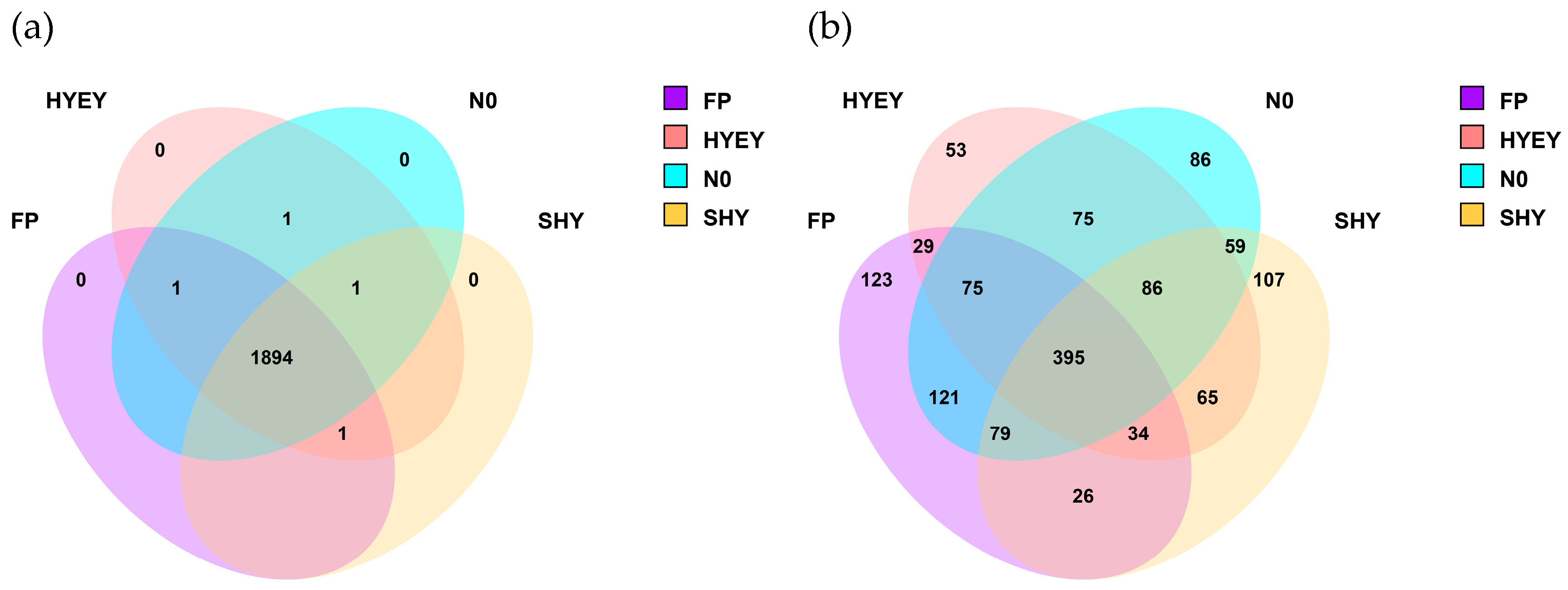

3.4. Wayne Map of the Out Distribution of Soil Bacteria and Fungal

A total number of bacterial communities OTUs was 1898, and the bacterial OTUs number common by N0, FP, HYEY, and SHY was 1894, 99.79% of the total, while specific OUT’s numbers of all four treatment were 0. FP, HYEY, and SHY could not increase the OTUs number of the bacterial community specificity, and the composition of bacterial community was similar under integrated cultivation practices (

Figure 1a). The total number of fungal communities OTUs was 1413, and the fungal OTUs number common by N0, FP, HYEY, and SHY was 395, 27.95% of the total, while specific OTUs numbers of N0, FP, HYEY, and SHY were 86, 123, 53 and 107, 26.11% of the total(

Figure 1b).

3.5. Principal Component Analysis of Microbiology

The contribution of the first principal component (PC1) of abscissa to the OTU difference of bacteria was 34.19%, the contribution of the second principal component (PC2) of ordinate to the difference of bacteria was 18.80%, the third principal component (PC3) co-dedicated 15.99% to bacterial OUT differences, and the cumulative contribution of the first principal component (PC1), second principal component (PC2), and third principal component (PC3) was 68.98% (

Figure 2a). Soil bacterial community composition under the four cultivation methods was similar. The results of

Figure 2b show that the contribution of the first principal component (PC1) to the fungal OTU differences was 22.04%, the second principal component (PC2) to the fungal OTU differences was 17.67%, and the third principal component (PC3) to the fungal OTU differences was 13.12%, and the cumulative contribution of the first (PC1), the second (PC2), and the third principal component (PC3 ) had a cumulative contribution of 52.83%. HYEY and SHY had obvious aggregation, while N0 and FP behaved as separate separations.

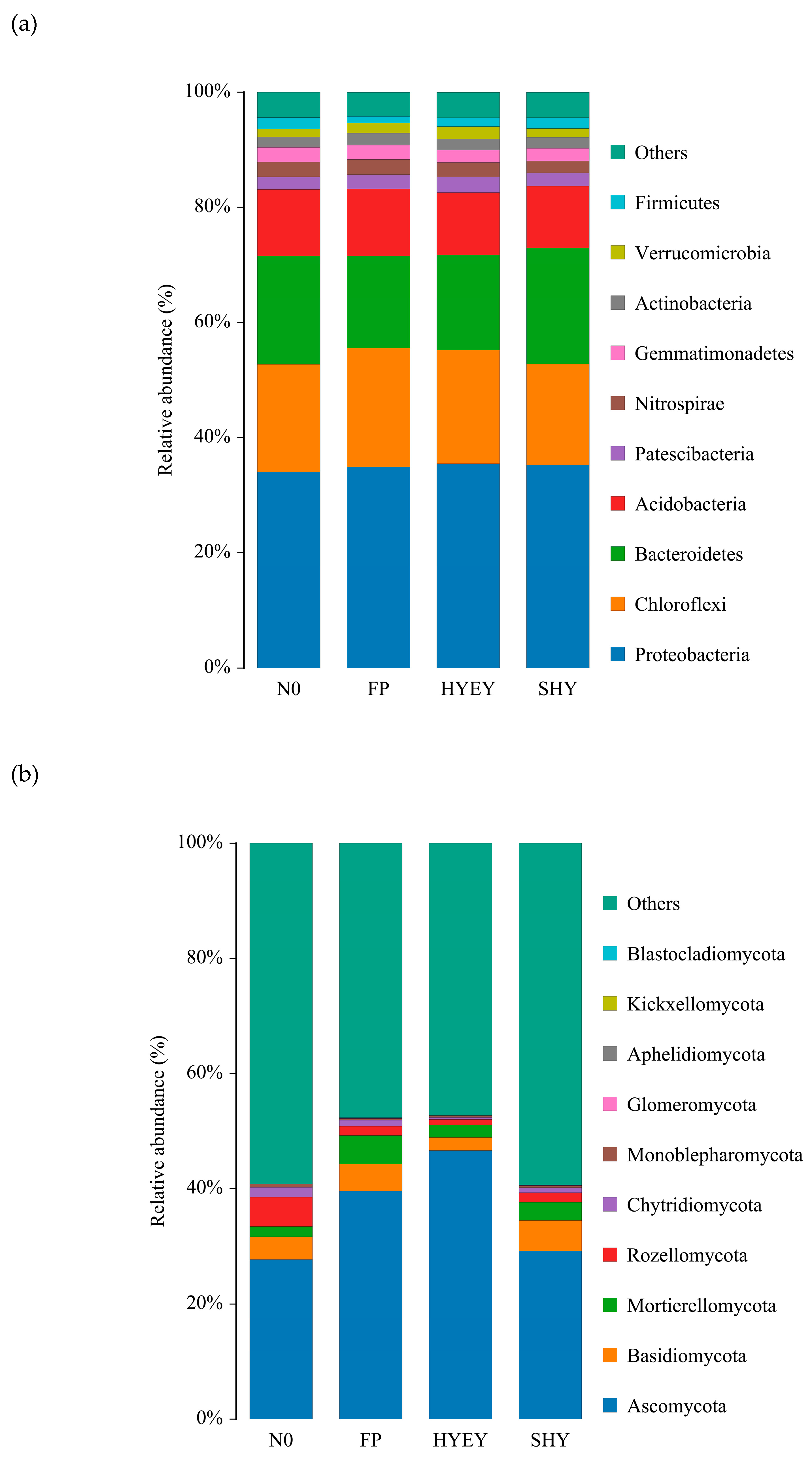

3.6. Composition Structure of Bacterial and Fungal Community at the Phylum Level

To explore the changes in species composition of bacteria and fungi in rice fields under different cultivation methods, the dominant phyla of the top 10 with relative abundance > 1% were analyzed by cluster analysis (

Figure 3a, b). At the phylum level of bacterial (

Figure 3a), Proteobacteria was an absolute dominant group, 34.03% - 35.50% of the total,

Chloroflexi, Bacteroidetes, and

Acidobacteria were preponderant groups of each treatment, 17.47% - 20.61%, 16.03% - 20.17% and 10.75% - 11.61%, respectively. The relative abundance of Proteobacteria of FP, HYEY, and SHY increased by 2.59%, 4.32%, and 3.73% respectively compared with that of N0. The relative abundance of

Chloroflexi showing FP>HYEY>N0>SHY, and the trend of Bacteroidetes was opposite of

Chloroflexi, showed SHY >N0>HYEY> FP. The relative abundance of

Chloroflexi of FP and HYEY increased by 10.19% and 5.35%, respectively compared with N0; the relative abundance of

Chloroflexi of SHY decreased by 6.53% compared with N0. The relative abundance of Bacteroidetes of SHY was increased by 7.06% compared with N0; the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes of FP and HYEY was decreased by 14.92% and 12.31%, respectively compared with N0. This indicated that there was some competition between

Chloroflexi and Bacteroidetes. The

Patescibacteria, Actinobacteria and

Verrucomicrobia of FP, HYEY, and SHY was increased compared with N0. A similar trend of

Patescibacteria and

Verrucomicrobia was HYEY>FP>SHY>N0, and the Actinobacteria of FP was the largest. The relative abundance of

Acidobacteria,

Nitrospirae,

Gemmatimonadetes, and Firmicutes of HYEY and SHY all showed a trend of less than N0 and FP.

Figure 3.

Structure and composition of the bacterial (

Figure 3a) and fungal (

Figure 3b) community at the phylum level under different treatments. N0: no nitrogen application; FP: local farmer practice; HYEY: high-yield and high-efficiency practice; SHY: super-high-yield practice.

Figure 3.

Structure and composition of the bacterial (

Figure 3a) and fungal (

Figure 3b) community at the phylum level under different treatments. N0: no nitrogen application; FP: local farmer practice; HYEY: high-yield and high-efficiency practice; SHY: super-high-yield practice.

At the phylum level of funguses (

Figure 3b), the relative abundance of phyla of others (the relative abundance ≤1 or unknown phyla) of four treatments was larger, 47.26% - 59.41% of the total. Ascomycota was an absolute dominant group, 27.71% - 46.64% of the total, while the remaining nine phyla had a low relative abundance. The relative abundance of Ascomycota of FP, HYEY and SHY was increased by 42.80%, 68.31%, and 5.27%, respectively compared with N0. This explained that FP, HYEY, and SHY had changed the dominant phyla of fungi. The

Mortierellomycota,

Glomeromycota,

Kickxellomycota, and

Blastocladiomycota of FP, HYEY, and SHY were increased over N0. Notable,

Kickxellomycota and

Blastocladiomycota were not present in N0, but

Kickxellomycota and

Blastocladiomycota appeared in FP, HYEY, and SHY. While

Aphelidiomycota only existed in N0 and HYEY, the relative abundance was 0.029% and 0.075%, respectively. Moreover, the Basidiomycota of FP and SHY all increased compared with N0.

Rozellomycota,

Chytridiomycota, and

Monoblepharomycota of FP, HYEY, and SHY were decreased compared with N0.

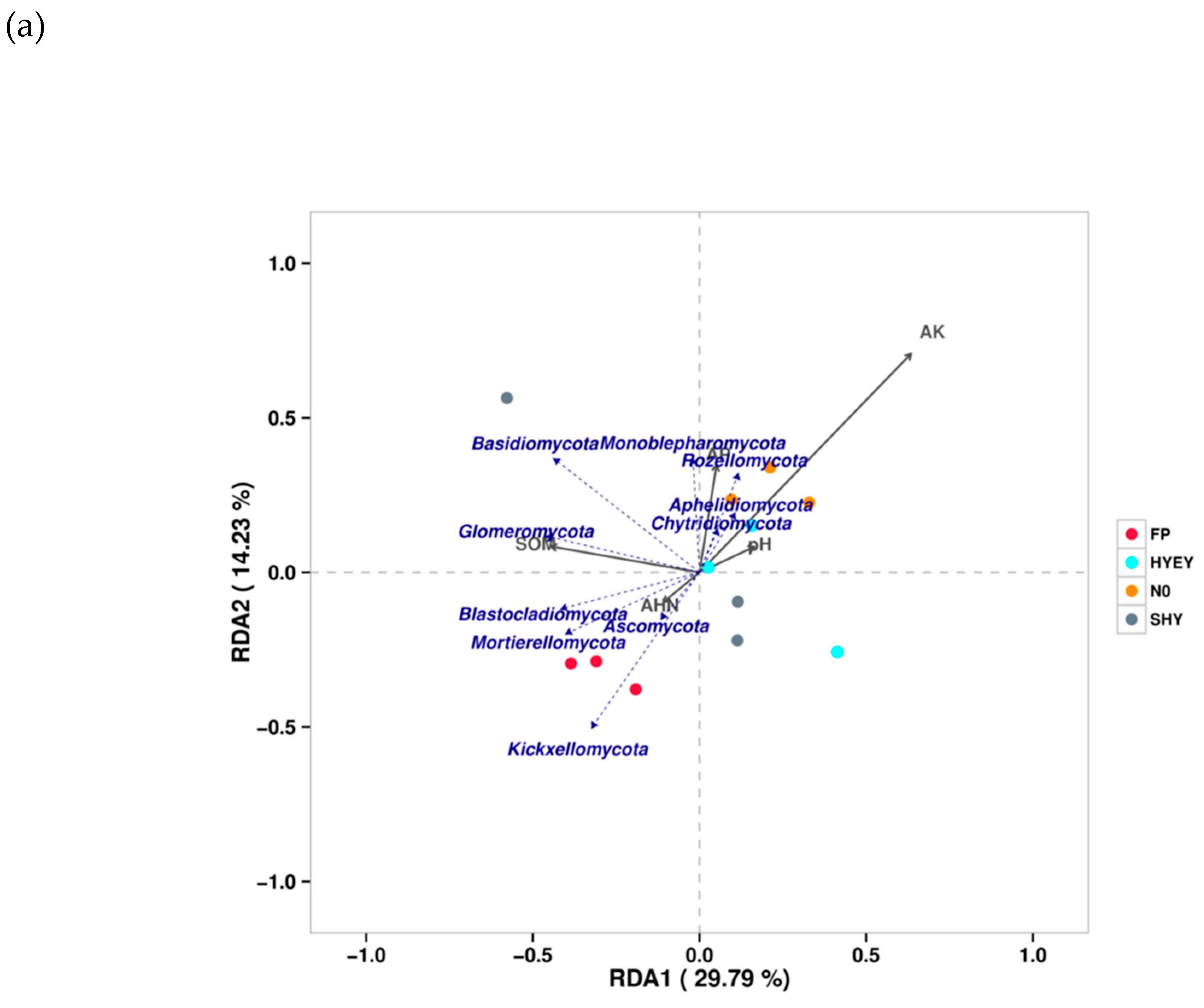

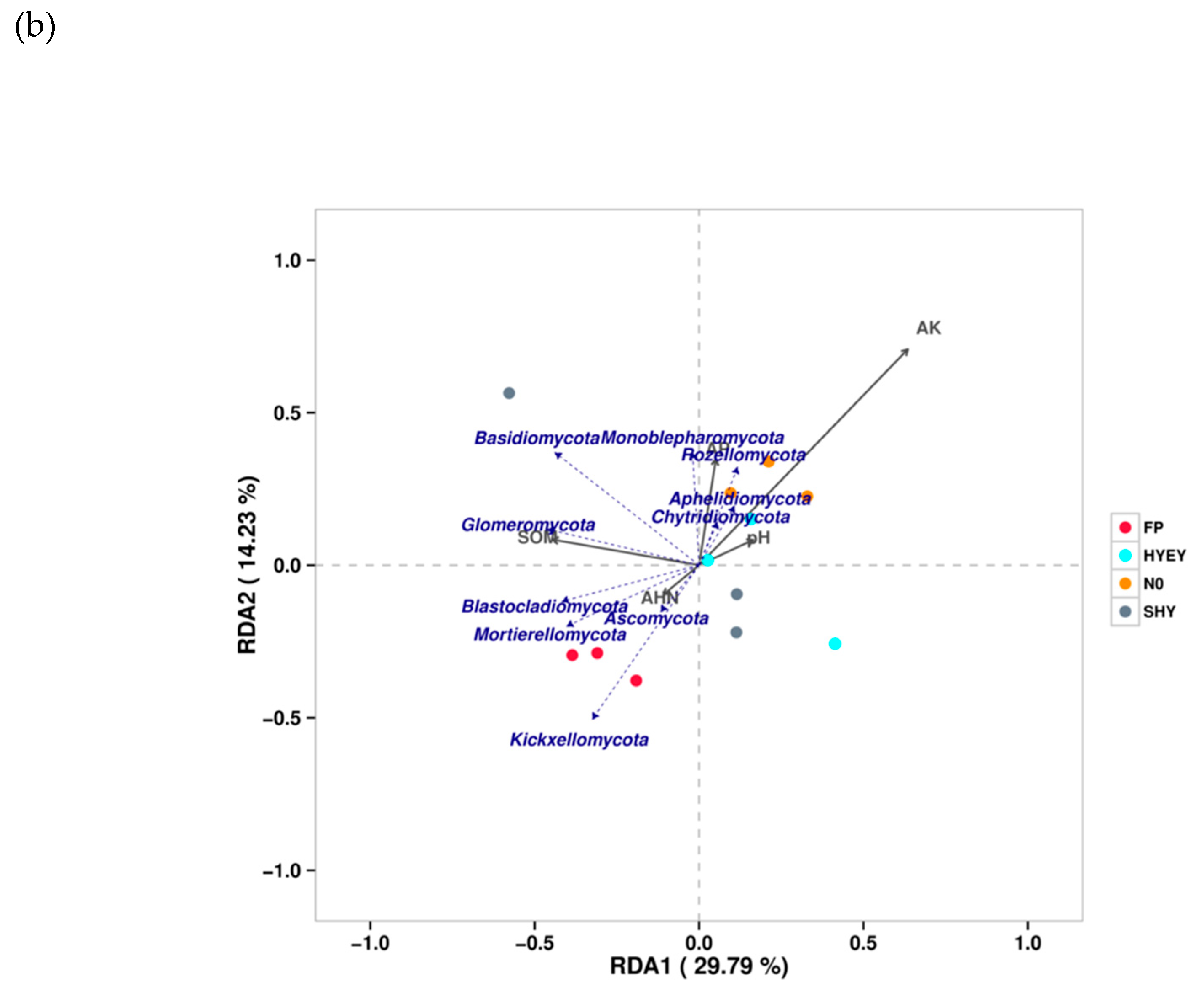

Based on RDA linear model, the relationship between soil bacteria, fungal community and environmental factors in rice paddy fields was explored (

Figure 4a, b). The principal elements 1 and 2 of environmental factors respectively explained 18.72% and 15.79% of the bacterial community, and the total explained 34.51% (

Figure 4a). The environmental factors that affected the composition of species at the phylum level of bacterial communities were available potassium and organic matter. Proteobacteria was positively correlated with soil alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen and organic matter and, negatively correlated with available phosphorus, pH, and available potassium.

Chloroflexi was negatively correlated with alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen, available phosphorus, available potassium, organic matter, and pH. This also explained the low relative abundance of Chloroflexi in N0. Bacteroidetes were the opposite, which all positively correlated with alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen, available phosphorus, available potassium, organic matter, and pH. Acidobacteria was positively correlated with soil alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen and organic matter, and negatively correlated with available phosphorus, pH, and available potassium.

Figure 4.

Redundancy analysis of the relationship between soil microbial community (

Figure 4a bacterial,

Figure 4b fungal) distribution and soil properties under different treatments. N0: no nitrogen application; FP: local farmer practice; HYEY: high-yield and high-efficiency practice; SHY: super-high-yield practice. AHN, alkaline hydrolyzable nitrogen; AK, available potassium; AP, available phosphorus; SOM, soil organic matter.

Figure 4.

Redundancy analysis of the relationship between soil microbial community (

Figure 4a bacterial,

Figure 4b fungal) distribution and soil properties under different treatments. N0: no nitrogen application; FP: local farmer practice; HYEY: high-yield and high-efficiency practice; SHY: super-high-yield practice. AHN, alkaline hydrolyzable nitrogen; AK, available potassium; AP, available phosphorus; SOM, soil organic matter.

According to

Figure 4b, the principal elements 1 and 2 of the environmental factors respectively explained 29.79% and 14.23% of the fungal community, and a total explained 44.02%. Available potassium was the main factor that affected the species composition of the fungal community at the phylum level, followed by organic matter.

Ascomycota,

Basidiomycota,

Mortierellomycota, and

Blastocladiomycota were positively correlated with soil alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen and organic matter, and negatively correlated with available phosphorus, available potassium, and pH, but the degree of correlation varied by fungal species.

Rozellomycota was negatively correlated with soil alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen and organic matter, and positively correlated with available phosphorus, available potassium, and pH.

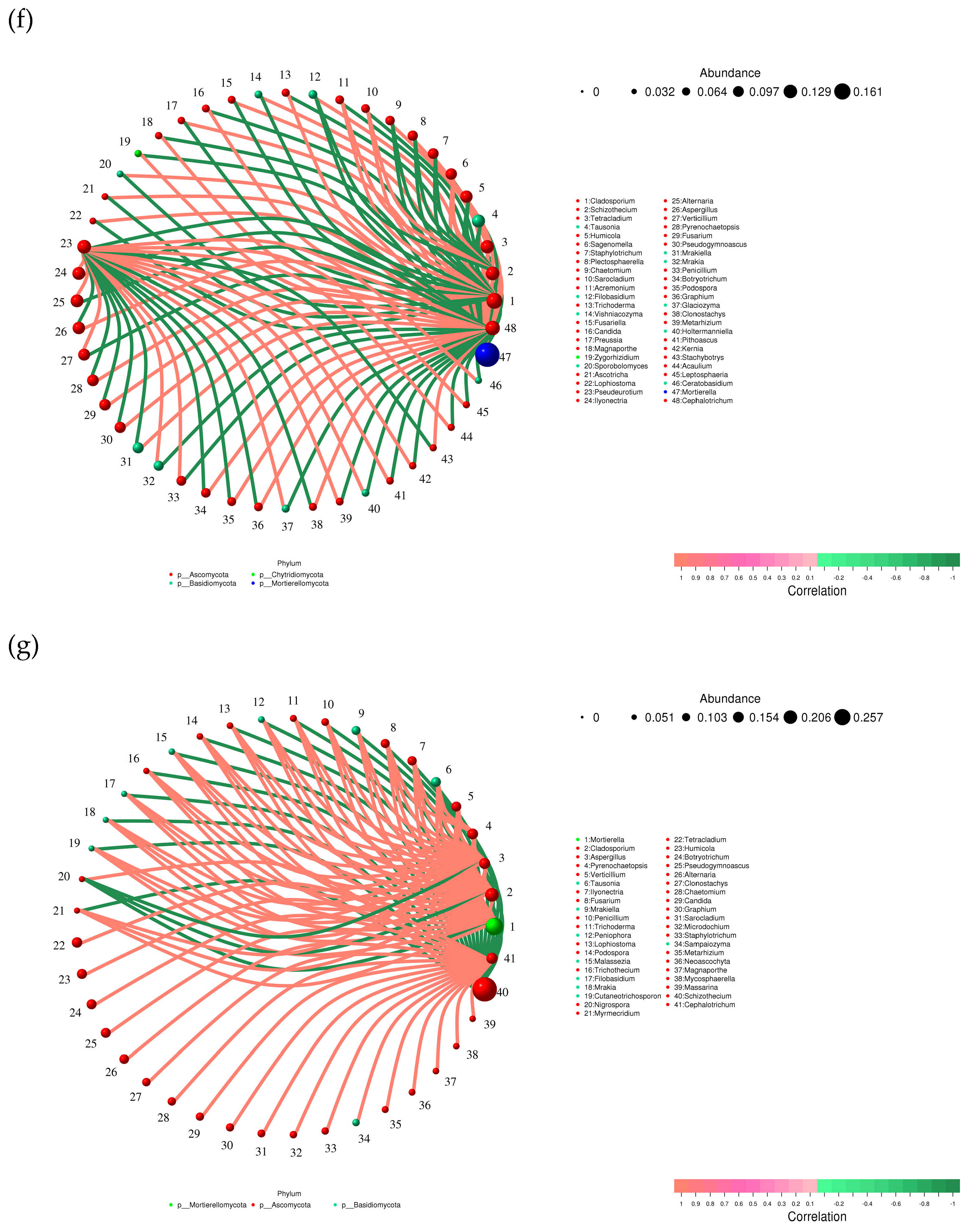

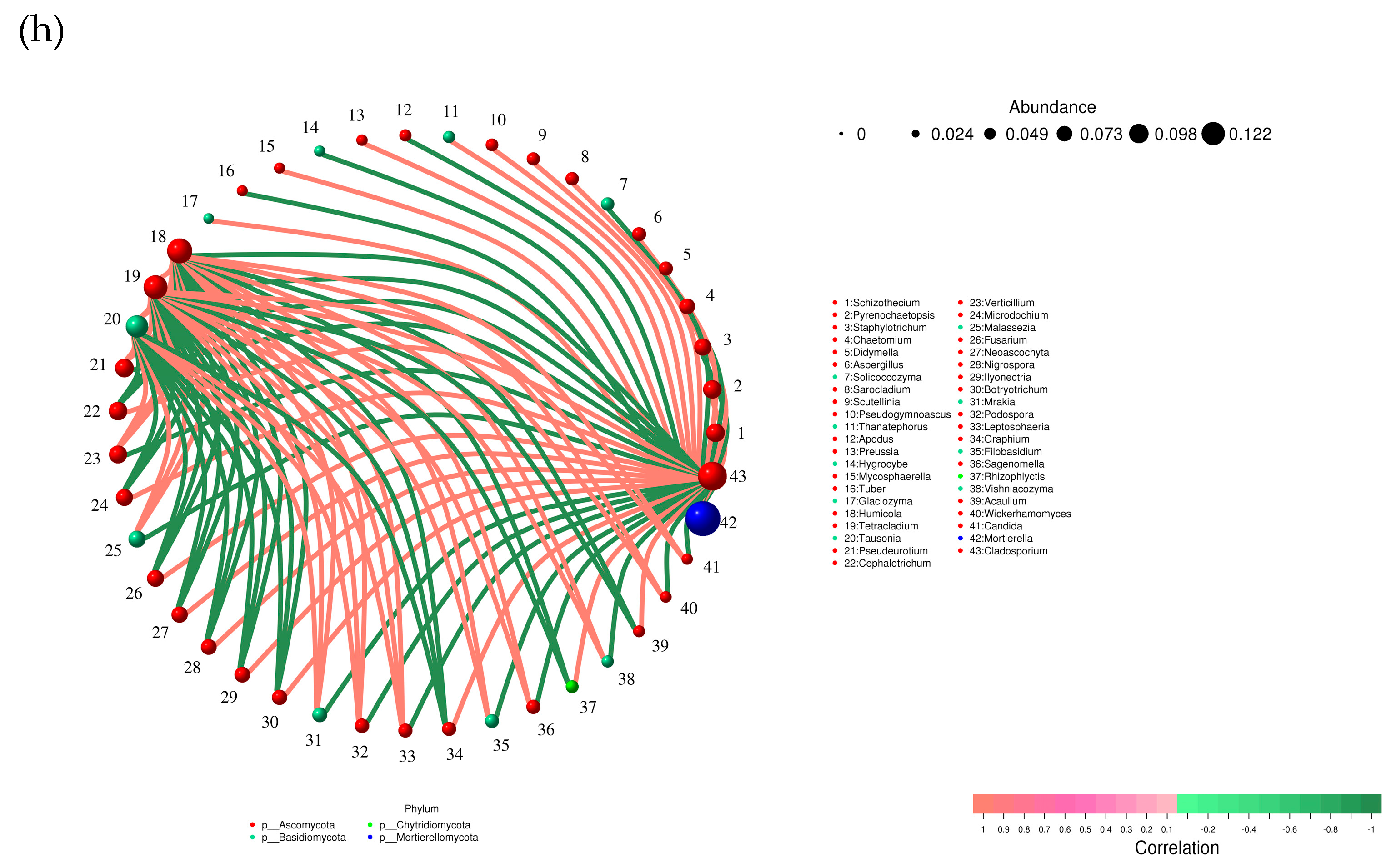

3.7. Species Correlation Network Analysis

To further explore the changes in the relationship between the species of soil microbial communities under each treatment, a species correlation network diagram was drawn based on python. The correlation network diagram was constructed based on the abundance of each species in each sample as well as the changes in Spearman (Spearman ) rank correlation analysis, and screening the data with correlation greater than 0.1 and p-value less than 0.05.

The number of pairwise positively correlated bacterial species in the N0 treatment (

Figure 5a) was 61, while it was 48 in the FP treatment (

Figure 5b), 45 in the HYEY treatment (

Figure 5c), and 55 in the SHY treatment (

Figure 5d). The number of positively correlated bacterial species among the top 50 most abundant genera across treatments followed the order: N0 > SHY > FP > HYEY. Compared to FP, the number of positively correlated species in SHY increased by 14.58%, while in HYEY, the number of positively correlated species decreased by 26.23% compared to N0.

In the N0 treatment (

Figure 5e), the number of pairwise positively correlated fungal species was 36, while it was 48 in the FP treatment (

Figure 5f), 77 in the HYEY treatment (

Figure 5g), and 51 in the SHY treatment (

Figure 5h). The number of positively correlated fungal species among the top 50 most abundant genera across treatments followed the order: HYEY > SHY > FP > N0. Compared to FP and N0, the number of positively correlated fungal species in HYEY increased by 60.42% and 113.39%, respectively. Similarly, in SHY, the number of positively correlated fungal species increased by 6.25% and 41.67%, compared to FP and N0, respectively. These results suggest that the HYEY treatment significantly influences fungal interactions in the soil.

4. Disscussion

Alpha diversity occurs within a particular region or ecosystem, and is a comprehensive indicator reflecting the species 'richness and diversity of a single sample(Grice et al., 2009). In the current study, integrated cultivation practices affected the richness index (ACE, Chao1 index) and diversity index (Shannon, Simpson index) of soil bacteria. HYEY had the highest richness indexes (ACE and Chao1 index) and the highest Shannon index, and had the lowest Simpson index. This indicated that high-yield cultivation methods can not only improve bacterial community richness, but also improve bacterial community diversity. The soil microbial diversity of FP was second only to that of HYEY. The changing trend of soil microbial diversity of SHY was contrary to HYEY. SHY had the lowest richness indexes (ACE and Chao1 index) and Shannon index, and the highest Simpson index due to excessive nitrogen application. Microbial diversity is very sensitive to environmental changes and management practices (Amadou et al., 2020), like fertilization or long-term nutrient inputs can easily affect the richness and diversity of the soil bacterial communities(Zhong et al., 2010). Overuse of nitrogen application in dryland soil led to reduced diversity of bacterial communities (Zeng et al., 2016). It has been shown that bacterial diversity was negatively associated with nitrogen application (Ling et al., 2017). Therefore, excessive nitrogen application may be a factor in reduced bacterial diversity under SHY soil. The effect of nitrogen application on the bacterial diversity in the soil was also significantly related to the water management system (Dai et al., 2018). This may be because bacteria were able to move and acquire nutrients in the soil environment using the flow of water membranes (Evans et al., 2012). Hamer et al. (2007) believed that with soil moisture content reduced, part of the active water-sensitive microbial cells disintegrated and died. Alternating dry and wet conditions can lead to reduced soil bacteria diversity in the rice ecosystem (Zhuang et al., 2017). Nitrogen application level of HYEY may be suitable for saline-alkali soil microbial growth, and on the other hand, Guifuji biological organic fertilizer may be conducive to the formation of microbial diversity. The combined use of two factors eliminated the negative effects of alternate drying and wetting. High levels of nitrogen application and alternate drying and wetting may be the main reasons for reduced microbial diversity for SHY. Soil pH has been shown the main factor affecting the structure and abundance of soil microbial communities (Zhao et al., 2014). In particularly, bacteria were most significantly affected by pH (Ahn et al., 2012). The relevant analysis of this test found that organic matter was the main factor affecting the bacterial diversity of soil bacteria, and the higher the soil organic matter content, the lower the richness and degree of soil bacterial community diversity. After the application of nitrogen and phosphorus and potassium fertilizer, the soil pH was weaker acidic (i.e. neutral or alkaline) which determine soil organic carbon as a key factor affecting the soil bacterial diversity (Dai et al., 2018). In this test, due to the obstacles of saline-alkali soil itself, changes in soil pH from N0 to SHY were small, and the impact of soil pH on bacterial diversity may also be reduced, and organic matter, as the matrix of heterotrophic bacteria, was more important in affecting bacterial diversity than soil pH. In addition, rice transplanting method, fertilization, soil available nutrients, and other biological and non-biological factors all affected the bacterial diversity of the soil.

In this study, compared to the Alpha diversity of soil bacterial communities, the cultivation methods had a more significant influence on the richness and diversity of the soil fungal phyla. The ACE and Chao1 indexes of the fungal community of 4 treatments all showed N0>FP>SHY>HYEY, and those of N0 were significantly higher than those of FP, HYEY, and SHY; the Shannon index of the fungal community of 4 treatments showed FP>N0> SHY>HYEY, and that of FP was significantly higher than N0, HYEY, and SHY; This suggested that HYEY and SHY were detrimental to fungal community growth. Comparison with Alpha diversity of soil bacterial communities showed that HYEY was beneficial to bacterial growth and inhibited fungal growth. This was likely because the HYEY soil environment was suitable for bacterial growth, increasing the number of some beneficial microbial bacteria in the bacterial community, and the coexistence of multiple soil microorganisms inhibited each other (Chen et al., 2015). Through soil microbial competitive exclusion(Eldridge et al., 2017), certain beneficial microbial bacteria in the bacteria community may inhibit harmful fungi in the fungus community, thus reducing the richness and diversity of fungal phyla in HYEY soil. Inorganic fertilizers not only significantly reduced fungal species, but also led to a decrease in fungal richness and diversity, and altered dominant fungal populations(Chen et al., 2017). The application of nitrogen reduced the richness and diversity of fungal classification and changed the community structure (Ji et al., 2018). This may be because fertilization stimulated the mass growth of certain specific microorganisms, but suppressed other microorganism growth, causing a decline in diversity (Chen et al., 2015). Studies also believed that root secretions affected fungal diversity (Liu et al., 2020). Peanut root secretions had more influence on the fungal community than on the bacterial community, and the growth of Mortierella and terrestrial bi-basidiomycetes was inhibited by the peanut root secretion of phenolic acid, thus reducing the relative abundance (Li et al., 2014). Fertilization promoted crop root metabolism and increased root secretion (Gao et al., 2005). Therefore, rice root secretions may be one of the factors affecting the diversity of fungal communities. In addition, the mycelium of soil fungus can both redistribute water(Vries et al.,2012), or obtain nutrients from the soil pores to relieve the pressure of water stress(Barnard et al., 2013), so the fungus is more resistant to water stress than bacteria (Zhu et al., 2019). Bacterial growth was reduced by alternating dry and wet, and the fungus remained unchanged (Bapiri et al., 2010). In this test, dry-wet alternation may have less or no impact on the diversity of fungal communities in HYEY, SHY soil. Alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen and organic matter were significantly negatively related with ACE, Chao1 index, available potassium was significantly positively related with ACE, Chao1 index, alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen, the relationship between available potassium, organic matter, and Shannon、Simpson index was insignificant. The high content of alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen and organic matter in HYEY, SHY soil resulted in a reduction of soil fungal richness. Available potassium content in N0 soil was the highest which resulted in increased soil fungal richness.

In this study, the Proteobacteria in rhizosphere soil were all absolute dominant groups under different cultivation methods, Chloroflexi, Bacteroidetes, and Acidobacteria were dominant groups. These bacteria may play an important role in rhizosphere soil. Proteobacteria is a symbiotic bacterium that grows rapidly in a C-rich environment (Jenkins et al., 2010) and is involved in the biocirculation of essential mineral nutrients in the soil (Celine et al., 2008).The high proportion of Proteobacteria in rhizosphere soil was conducive to the maintenance of soil fertility and plant growth (Chaudhry et al., 2012).The Proteobacteria was highly responsive to N input and the relative abundance increased with nitrogen application (Dai et al., 2018). The test results showed that FP, HYEY, SHY increased the relative abundance of Proteobacteria compared to N0, and Proteobacteria abundance of HYEY, SHY was higher than FP. RDA analysis showed that Proteobacteria was positively associated with alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen and organic matter. This indicated that the increase of Proteobacteria abundance in rhizosphere soil favored the accumulation of alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen and organic matter, while high organic matter content had high organic carbon content. This in turn stimulated Proteobacteria growth. Proteobacteria was negatively associated with available phosphorus, available potassium, and pH. This further explained why the Proteobacteria relative abundance of SHY was slightly lower than HYEY. In this study, FP, HYEY, and SHY reduced the relative abundance of the Firmicutes compared with N0, and showed the opposite trend to Proteobacteria. There was a nutritional competition between Proteobacteria and Firmicute (Tang et al., 2021). Rodrigues et al. (2013) believed that Firmicutes was also a trophic organism, and high carbon stimulated its growth. But Firmicutes was also an oligotrophic bacterium (Freedman et al., 2013), and high nitrogen application reduced its abundance (Li et al., 2020a). According to the above views, the presence of Proteobacteria and the relationship between nitrogen application amount and Firmicutes explained the decrease of the Firmicutes relative abundance of FP, HYEY, and SHY. RDA analysis found that Firmicutes had a positive correlation with alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen, available phosphorus, available potassium, organic matter, and pH. This explained the reason that the Firmicute’s relative abundance of HYEY, and SHY was higher than that of FP. Chloroflexi was mainly inclined to anaerobic conditions (Li et al., 2020b), was the main degradation of sugar and polysaccharide (Podosokorskaya et al., 2013), enhanced the crop absorption of soil nutrients(Kragelund et al., 2007). This study showed that FP, and HYEY increased the relative abundance of Chloroflexi compared to N0, while SHY decreases the relative abundance of Chloroflexi. RDA analysis showed that Chloroflexi had a negative correlation with alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen, available phosphorus, available potassium organic matter, and pH, which suggested that the reduced relative abundance of Asperglum favors the preservation of SHY soil fertility. Bacteroidetes was an anaerobic or facultative anaerobic eutrophic bacteria, a relative abundance of Bacteroidetes increased at a high organic level (Li et al., 2006). This study showed that Bacteroidete’s relative abundance of FP, HYEY decreased compared to N0, and the soil organic matter content of SHY was significantly higher than N0, FP, HYEY, thus the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes was the highest. Bacteroidetes had a Phosphate-solubilizing function and was positively associated with available phosphorus content (Wang et al., 2020). Acidobacteria was recognized as oligotrophic bacteria(Pascault et al., 2013) The high nutritional environment of HYEY, SHY reduced the relative abundance of the Acidobacteria compared to FP. Generally, acid bacteria can adapt to acidic soil environments with low pH (Lauber et al., 2008). This test also showed that Acidobacteria had a negative association with pH.

In agricultural soils, Ascomycota was the largest group of fungi, which degraded nonpeer fishable organic matter in the soil, and increased as nutrients increased(Leff et al., 2015). The experimental study showed that Ascomycota in rhizosphere soil of rice fields was the absolute dominant group under different cultivation methods, compared with N0, Ascomycota of FP, HYEY, and SHY was increased by 42.80%, 68.31%, and 5.27%, respectively. This suggested that high nutrient input (SHY) did not increase Ascomycota abundance, but inhibited. This was because the promoting effect of alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen and organic matter on Ascomycota did not compensate for the inhibition of available phosphorus, available potassium, and pH on Ascomycota. In addition, Ascomycota had strong drought resistance and could survive in soil moisture-limited environments (Yan et al., 2021). Most Basidiomycota fungi were rotten or parasitic fungi, which were also important decompositions in the soil (Yelle et al., 2008), and liked the soil conditions with better ventilation (Sui et al., 2016). This study showed that higher abundance of Basidiomycota in SHY, which may be due to the high level of organic matter in SHY soils. HYEY, SHY changed the growth environment of the fungal community, increased the soil available nutrients and organic matter content more suitable for the growth of rotten fungi, but the HYEY soil environment was more suited to the Ascomycota fungus, while SHY was more inclined to the Basidiomycota. This also suggested that a different fungal community adaptation to different environments led to fungal community changes under N0, FP, HYEY, and SHY.

5. Conclusion

Different cultivation practices altered soil bacterial diversity and fungal communities. Compared with bacterial community diversity, the cultivation method significantly affected fungal community diversity. HYEY tillage practices increased the abundance and diversity of bacterial communities, significantly decreased the abundance and diversity of fungal communities, and significantly elevated positive soil fungal interactions. The richness and diversity of bacterial communities under SHY were decreased but fungal community abundance was increased for N0. Both, HYEY and SHY practices improved soil nutrient content, especially alkali-hydrolyzed nitrogen and organic matter. Under different cultivation methods, bacteria took Proteobacteria as the absolute dominant group, Chloroflexi, Bacteroidetes, and Acidobacteria as the dominant group; fungi took Ascomycota as the absolute dominant group. Available potassium and organic matter were the main environmental factors that affected the species composition at the phylum level of the bacterial community. Soil-available potassium was the major environmental factor that affected species composition at the phylum level of the fungal community.

Funding

This research was funded by the Opening Foundation of Collaborative Innovation Center for Genetic Improvement and High Quality and Efficiency Production of Northeast Japonica Rice, grant number KF2022-02 and Heilongjiang Provincial Higher Education Teaching Reform Project, grant number SJGY20220466.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z.; Data curation, Y.H.; Formal analysis, Y.G. and Y.Z.; Funding acquisition, X.G.; Investigation, L.X.; Project administration, H.L.; Supervision, X.G. and Y.L.; Writ-ing—original draft, Q.L.; Writing—review and editing, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ahn, J.H. , Song, J., Kim, B.Y., Kim, M.S., Joa, J.H., Weon, H.Y. 2012. Characterization of the bacterial and archaeal communities in rice field soils subjected to long–term fertilization practices. Journal of Microbiology. 50: 754–765.

- Amadou, A. , Song, A., Tang, Z.X., Li, Y.L., Wang, E.Z., Lu, Y.Q., Liu, X.D., Yi, K.K, Zhang, B., Fan, F.L. 2020. The effects of organic and mineral fertilization on soil enzyme activities and bacterial community in the below–and above–ground parts of wheat. Agronomy.10: 1452.

- Bao, S.D. Soil Agrochemical Analysis (Third Edition). Beijing: China Agricultural Press, 2005.(in Chinese).

- Bapiri, A. , Bååth, E., Rousk, J. Drying–rewetting cycles affect fungal and bacterial growth differently in an arable soil. 2010. Microbial Ecology. 60: 419–428.

- Barnard, R.L. , Osborne, C.A., Firestone, M.K. Responses of soil bacterial and fungal communities to extreme desiccation and rewetting. 2013. The ISME Journal. 7:2229–2241.

- Caporaso, J.G. , Lauber, C.L., Walters, W.A., Berg–Lyons, D., Huntley, J., Fierer, N., Owens, S.M., Betley, J., Fraser, L., Bauer, M., Gormley, N., Gilbert, J.A., Smith, G., Knight, R. 2012. Ultra–high–throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. The ISME Journal. 6:1621–1624.

- Celine, L. , Dimitris, P., Sean, M., Bernard, O., Steven, S., Safiyh, T., Donald, Z, Daniel, V.D.L. Elevated atmospheric CO2 affects soil microbial diversity associated with trembling aspen. 2008. Environmental Microbiology. 10:926–941.

- Chaudhry, V. , Rehman, A., Mishra, A., Chauhan, S.P., Nautiyal, C.S. 2012. Changes in bacterial community structure of agricultural lnd due to long–term organic and chemical amendments. Microbial Ecology. 64: 450–460.

- Chen, C.L. , Wu, M.N., Wei, W.X. 2011. Effect of long–term application of nitrogen fertilizer on the diversity of nitrifying genes (amoA and hao) in paddy soil. Environment Science. 32: 1489–1496. (in Chinese).

- Chen, D.M. , Chen, X.M., Liang, Y.J., Huo, X.J., Zhang, C.H., Duan, Y.Q., Yang, Y.H., Yuan, L. 2015. Influence of crop rotation on soil nutrients,microbial activities and bacterial community structures. Acta Prataculturae Sinica.24: 56–65. (in Chinese).

- Chen, D.M. , Yuan, L., Huang, J.G., Ji, J.H., Hou, H.Q., Liu, Y.R. 2017. Influence of long–term fertilizations on nutrients and fungal communities in typical paddy soil of south China. Acta Agronomica Sinica. 43: 286–295. (in Chinese).

- Chen, X.F. , Li, Z.P., Liu, M., Jiang, C.Y., Che, Y.P. 2015. Microbial community and functional diversity associated with different aggregate fractions of a paddy soil fertilized with organic manure and/or NPK fertilizer for 20years. Journal of Soils and Sediments. 15: 292–301.

- Chen, Z.G. , Dai, Y.Y. 2020. Analysis report of heilongjiang rice market in 2019. Heilongjiang Liangshi. 5: 23–27. (in Chinese).

- Dai, Z.M. , Su, W.Q., Chen, H.H., Barberán, A., Zhao, H.C., Yu, M.J., Yu, L., Brookes, P.C., Schadt, C.W., Chang, S.X., Xu, J.M. 2018. Long–term nitrogen fertilization decreases bacterial diversity and favors the growth of Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria in agro–ecosystems across the globe. Global Change Biology. 24: 3452–3461.

- Dangi, S.R. , Zhang, H.H., Wang, D., Gerik, J., Hanson, B.D. 2016. Soil microbial community composition in a peach orchard under different irrigation methods and postharvest deficit irrigation. Soil Science. 181: 208–215.

- Eldridge, D.J. , Delgado–Baquerizo, M., Travers, S.K., Val, J., Oliver, L., Hamonts, K., Singh, B.K. 2017. Competition drives the response of soil microbial diversity to increased grazing by vertebrate herbivores. Ecology. 98: 1922–1931.

- Evans, S.E. , Wallenstein, M.D. 2012. Soil microbial community response to drying and rewetting stress: does historical precipitation regime matter? Biogeochemistry.109: 101–116.

- Freedman, Z. , Eisenlord, S.D., Zak, D.R., Xue, K., He, Z.L., Zhou, J.Z. 2013.Towards a molecular understanding of N cycling in northern hardwood forests under future rates of N deposition. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 66: 130–138.

- Gao, R. , Lv J.L. 2005. Study on the enzyme activities and fertility change of soils by a long–term located utilization of different fertilizers. Chinese Journal of Eco–Agriculture. 13:143–145. (in Chinese).

- Gil, S.V. , Meriles, J., Conforto, C., Basanta, M., Radl, V., Hagn, A., Schloter, M., March, G.J. 2010. Response of soil microbial communities to different management practices in surface soils of a soybean agroecosystem in Argentina. European Journal of Soil Biology. 47: 55–60.

- Grice, E.A. , Kong, H.H., Conlan, S., Deming, C.B., Davis, Joie., Young, A.C., Bouffard G.G., Blakesley, R.W., Murray, P.R., Green, E.D., Turner, M.L., Segre, J.A. 2009. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science. 324: 1190–1192.

- Grover, J.P. 2004. Predation, competition, and nutrient recycling: a stoichiometric approach with multiple nutrients. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 229: 31–43.

- Hamer, U. , Unger, M., Makeschin, F. 2007. Impact of air-drying and rewetting on PLFA profiles of soil microbial communities. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science. 170: 259–264.

- Huang, X.M. , Liu, S.R., Wang, H., Hu, Z.D., Li, Z.G., You, Y.M. 2014. Changes of soil microbial biomass carbon and community composition through mixing nitrogen–fixing species with Eucalyptus urophylla in subtropical China. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 73: 42–48.

- Jenkins, S.N. , Rushton, S.P., Lanyon, C.V., Whiteley, A.S., Waite, L.S., Brookes, P.C., Kemmitt, S., Evershed, R.P., O’Donnell, A.G. 2010. Taxon–specific responses of soil bacteria to the addition of low level C inputs. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 42: 1624–1631.

- Ji, L.F. , Ni, K., Ma, L.F., Chen, Z.J., Zhao, Y.Y., Ruan, J.Y., Guo, S.W. 2018. Effect of different fertilizer regimes on the fungal community of acidic tea–garden soil. Acta Ecologica Sinica.38: 8158–8166. (in Chinese).

- Jorquera, M.A. , Martínez, O.A., Marileo, L.G., Acuña, J.J., Saggar, S., Mora, M.L.2014. Effect of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization on the composition of rhizobacterial communities of two Chilean Andisol pastures. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 30:99–107.

- Kragelund, C. , Levantesi, C., Borger, A., Thelen, K., Eikelboom, D., Tandoi, V., Kong, Y., van der Waarde, J., Krooneman, J., Rossetti, S., Thomsen, T.R., Nielsen, P.H. 2007. Identity, abundance and ecophysiology of filamentous Chloroflexi species present in activated sludge treatment plants. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 59: 671–682.

- Lauber, C.L. , Strickland, M.S., Bradford, M.A., Fierer, N. 2008. The influence of soil properties on the structure of bacterial and fungal communities across land–use types. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 40: 2407–2415.

- Leff, J.W. , Jones, S.E., Prober, S.M., Barberán, A., Borer, E.T., Firn, J.L., Harpole, W.S., Hobbie, S.E., Hofmockel, K.S., Knops, J.M.H., McCulley, R.L., La, P.K., Risch, A.C., Seabloom, E.W., Schütz, M., Steenbock, C., Stevens, C.J., Fierer, N. 2015. Consistent responses of soil microbial communities to elevated nutrient inputs in grasslands across the globe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112: 10967–10972.

- Li, Q. , Li, C., Fang, B.H., Liu, Y., Kuang, W., Chen, K.L., Zhou, X.Q., Wang, W.X., Zhang Y.Z. 2020. Effect of different irrigation modes in paddy soil on microbial community functional diversity. Genomics and Applied Biology. 39: 1632–1641. (in Chinese).

- Li, X. , Sun, M.L., Zhang, H.H., Xu, N., Sun, G.Y. 2016. Use of mulberry–soybean intercropping in salt–alkali soil impacts the diversity of the soil bacterial community. Microbial Biotechnology. 9: 293–304.

- Li, X. , Zhang, H.H., Sun, M.L., Xu, N., Sun, G.Y., Zhao, M.C. 2020. Land use change from upland to paddy field in mollisols drives soil aggregation and associated microbial communities. Applied Soil Ecology. 146:103351.

- Li, X.G. , Ding, C.F., Hua, K., Zhang, T.L., Zhang, Y.N., Zhao, L., Yang, Y.R., Liu, J.G., Wang, X.X. 2014. Soil sickness of peanuts is attributable to modifications in soil microbes induced by peanut root exudates rather than to direct allelopathy. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 78: 149–159.

- Li, Y.Z. , Song, D.P., Liang, S.H., Dang, P.F., Qin, X.L., Liao, Y.C., Siddique, K.H.M. 2020. Effect of no–tillage on soil bacterial and fungal community diversity: A meta–analysis. Soil and Tillage Research. 204: 104721.

- Lin, X.B. , Shi, H., Wu, L., Cheng, Y.H., Cai, S., Huang, S.S., He, S.L., Huang, Q.R., Zhang, K. 2020. Effects of cultivation methods on soil microbial community structure and diversity in red paddy. Ecology and Environmental Sciences. 29:2206–2214. (in Chinese).

- Ling, N. , Chen, D.M., Guo, H., Wei, J.X., Bai, Y.F., Shen, Q.R., Hu, S.J. 2017. Differential responses of soil bacterial communities to long–term N and P inputs in a semi–arid steppe. Geoderma. 292: 25–33.

- Liu, H. , Pan, F.J., Han, X.Z., Song, F.B., Zhang, Z.M., Yan, J., Xu, Y.L. 2020. A comprehensive analysis of the response of the fungal community structure to long–term continuous cropping in three typical upland crops. Journal of Integrative Agriculture. 19: 866–880.

- Lv, Y.D. , Yue Hu, Y., Jiang, H.F., Lan, Y.C., Wang, H.Y., Xu, L.Q., Yin, D.W., Zheng, G.P., Guo, X.H.2020. Agronomic practices affect rice yield and nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium accumulation, allocation and translocation. Agronomy journal. 112: 1238–1249.

- Manzoni, S. , Schimel, J.P., Porporato, A. 2012. Responses of soil microbial communities to water stress: results from a meta–analysis. Ecology. 93:930–938.

- Meisner, A. , Jacquiod, S., Snoek, B.L, Ten, H.F.C., van der Putten, W.H. Drought legacy effects on the composition of soil fungal and prokaryote communities. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2018, 9:294.

- Pascault, N. , Ranjard, L., Kaisermann, A., Bachar, D., Christen, R., Terrat, S., Mathieu, O., Lévêque, J., Mougel, C., Henault, C., Lemanceau, P., Péan, M., Boiry, S., Fontaine, S., Maron P.A. 2013. Stimulation of different functional groups of bacteria by various plant residues as a driver of soil priming effect. Ecosystems. 16:810–822.

- Podosokorskaya, O.A. , Bonch–Osmolovskaya, E.A., Novikov, A.A., Kolganova, T.V., Kublanov, I.V. 2013. Ornatilinea apprima gen. nov. sp. nov. a cellulolytic representative of the class Anaerolineae. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 63: 86–92.

- Rodrigues, J.L.M. , Pellizari, V.H., Mueller, R., Baek, K., Jesus, E.D.C., Paula, F.S., Mirza, B., Hamaoui, G.S., Tsai, S.M., Feigl, B., Tiedje, J.M., Bohannan, B.J.M., Nüsslein, K. 2013. Conversion of the Amazon rainforest to agriculture results in biotic homogenization of soil bacterial communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110: 988–993.

- Su, J.Q. , Ding, L.J., Xue, K., Yao, H.Y., Quensen, J., Bai, S.J., Wei, W.X., Wu, J.S., Zhou, J.Z., Tiedje. J.M., Zhu, Y.G. 2015. Long–term balanced fertilization increases the soil microbial functional diversity in a phosphorus–limited paddy soil. Molecular Ecology. 24: 136–150.

- Sui, X. , Zhang, R.T., Xu, N., Liu Y.N., Chai, C.R., Wang, J.F., Fu, X.L., Zhong, H.X., Ni, H.W. 2016. Fungal community structure of different degeneration deyeuxia angustifolia wetlands in Sanjiang plain. Environmental Science. 37:3598–3605. (in Chinese).

- Tang, H.M. , Xiao, X.P., Li, C., Cheng, K.K., Shi, L.H., Pan, X.C., Li, W.Y., Wen, L., Wang, K. 2021. Tillage and crop residue incorporation effects on soil bacterial diversity in the double–cropping paddy field of southern China. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science. 67: 435–446.

- Vogel, T.M. , Simonet. P., Jansson, J.K., Hirsch, P.R., Tiedje, J.M., van Elsas, J.D., Bailey, M.J., Nalin, R., Philippot, L. 2009. TerraGenome: a consortium for the sequencing of a soil metagenome. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 7:252.

- Vries, F.T. , Liiri, M.E., Bjørnlund, L., Bowker, M.A., Christensen, S., Setälä, H.M., Bardgett, R.D. 2012. Land use alters the resistance and resilience of soil food webs to drought. Nature Climate Change. 2: 276–280.

- Wang, D. , Zhao, Y.G., Ma, R., Yang, P., Zhang, C., Zhou, D.J., Sun, F.J., Zhang, F.H. 2020. Effects of microbial fertilizers on soil improvement and bacterial communities in saline–alkali soils of lycium barbarum. Journal of Agricultural Biotechnology. 28: 1499–1510. (in Chinese).

- Xia, X. , Shi, K., Huang, Q.R., Li, D.M., Liu, M.Q., Li, H.X., Hu, F., Jiao, J.G. 2015. The changes of microbial community structure in red paddy soil under long–term fertilization. Acta Pedologica Sinica. 52:697–705. (in Chinese).

- Yan, R. , Feng, W., Wang, X.J. 2021. Composition and diversity of soil fungi community under different sand–fixing plants in the Hulun Buir Desert. Science of Soil and Water Conservation. 19: 60–68. (in Chinese).

- Yelle, D.J. , Ralph, J., Lu, F.C., Hammel, K.H. 2008. Evidence for cleavage of lignin by a brown rot basidiomycete. Environmental Microbiology. 10: 1844–1849.

- Zeng, J. , Liu, X.J., Song, L., Lin, X.G., Zhang, H.Y., Shen, C.C., Chu, H.Y. 2016. Nitrogen fertilization directly affects soil bacterial diversity and indirectly affects bacterial community composition. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 92: 41–49.

- Zhang, W.W. , Wang, C., Xue, R., Wang, L.J. 2019. Effects of salinity on the soil microbial community and soil fertility. Journal of Integrative Agriculture. 18: 1360–1368.

- Zhao, J. , Ni, T., Li, Y., Xiong, W., Ran, W., Shen, B., Shen, Q.R., Zhang, R.F. 2014. Responses of bacterial communities in arable soils in a rice–wheat cropping system to different fertilizer regimes and sampling times. PloS ONE. 9, e85301.

- Zhong, W.H. , Gu, T., Wang, W., Zhang, B., Lin, X.G., Huang, Q.R., Shen, W.S. 2010. The effects of mineral fertilizer and organic manure on soil microbial community and diversity. Plant and Soil. 326: 523.

- Zhu, Y.Z. , Li, Y.Y., Han, J.G., Yao, H.Y. 2019. Effects of changes in water status on soil microbes and their response mechanism: A review. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology. 30:4323–4332. (in Chinese).

- Zhuang, L.J. 2017 Effects of wetting and drying conditions on the abundance of anaerobic ammonium oxidation bacteria and ammonia oxidizing archaea in soil. Shanghai: Donghua University. (in Chinese).

- Lv, Y. , Hu, Y., Sun, F., Huo, W., Li, H., Liu, L., Yin, D., Zheng, G., & Guo, X. 2022. Yield and Resource Utilization Efficiency Gap in Early Maturing Japonica Rice Cultivars under Different Management Strategies—A Different Location Investigation. Agriculture, 12(7), 1010.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).