Submitted:

05 September 2023

Posted:

07 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

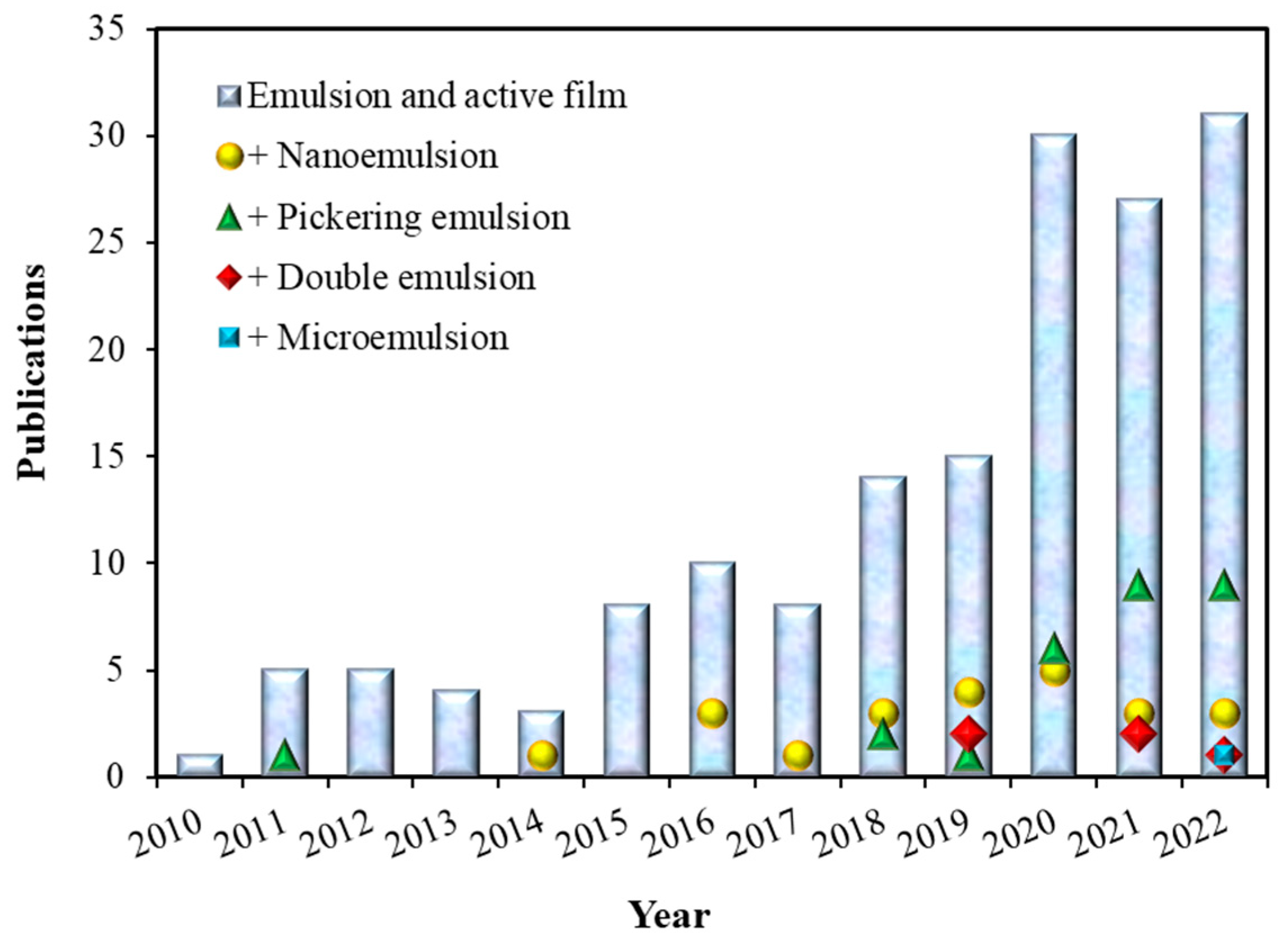

1. Introduction

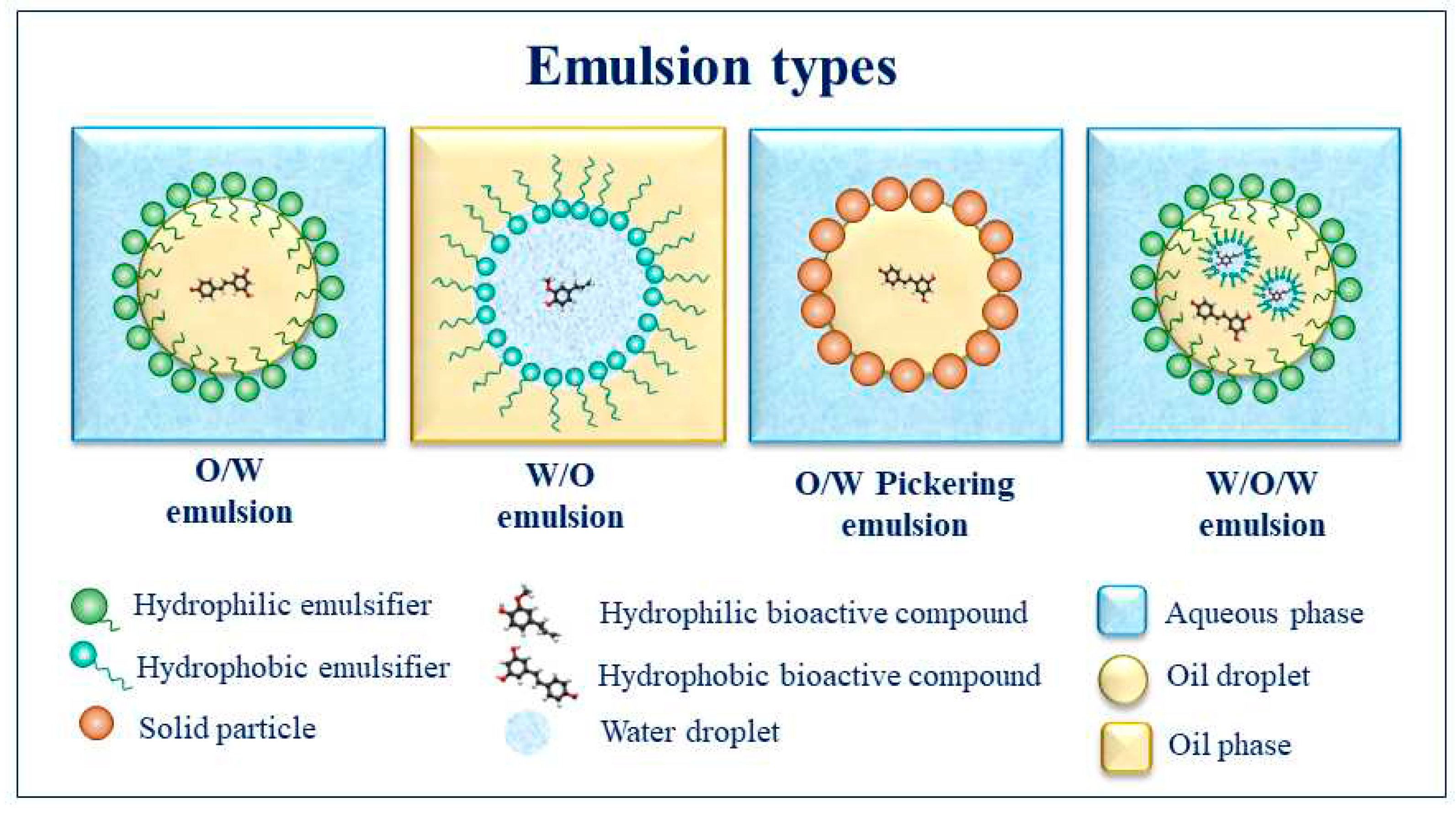

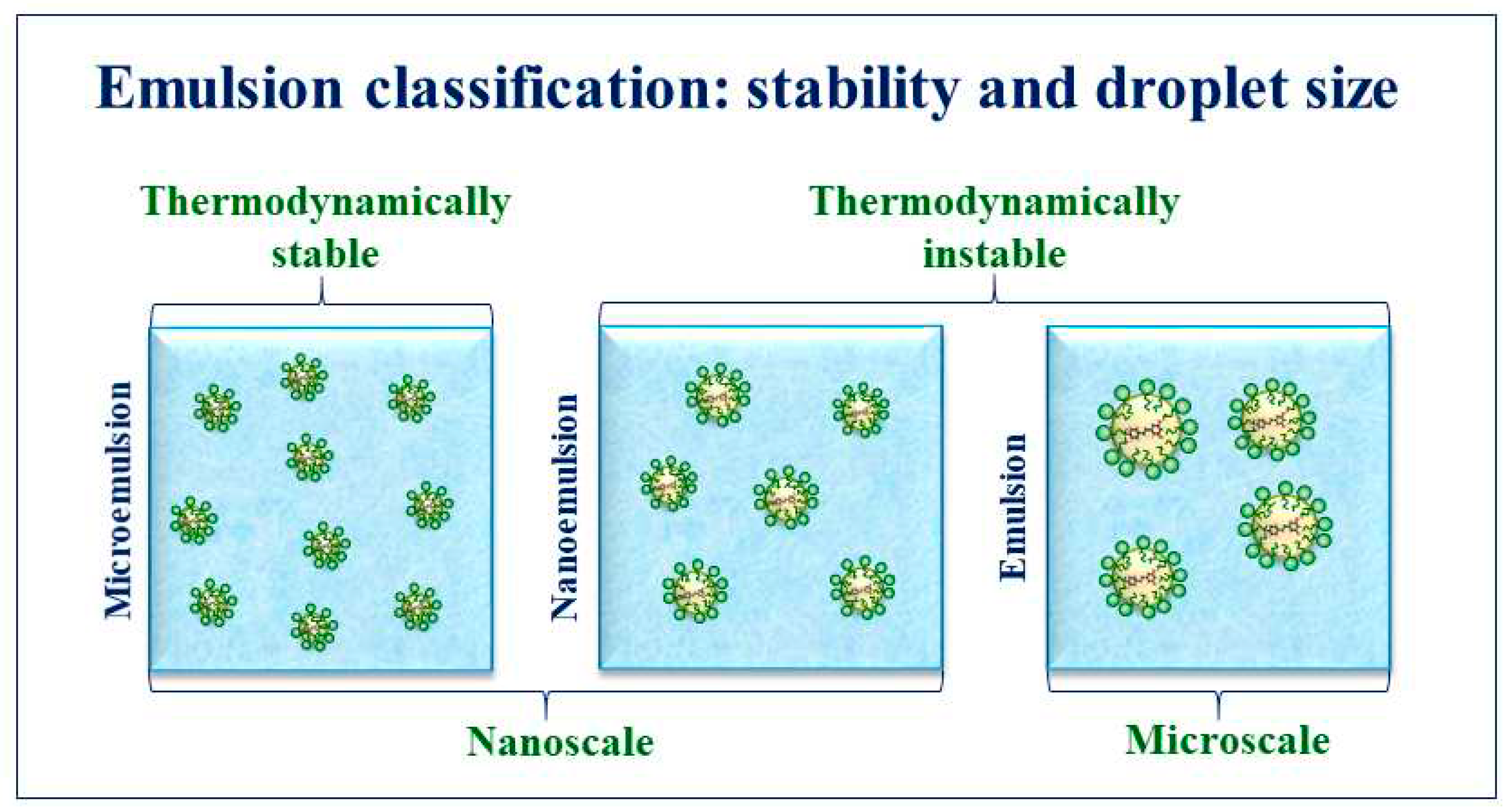

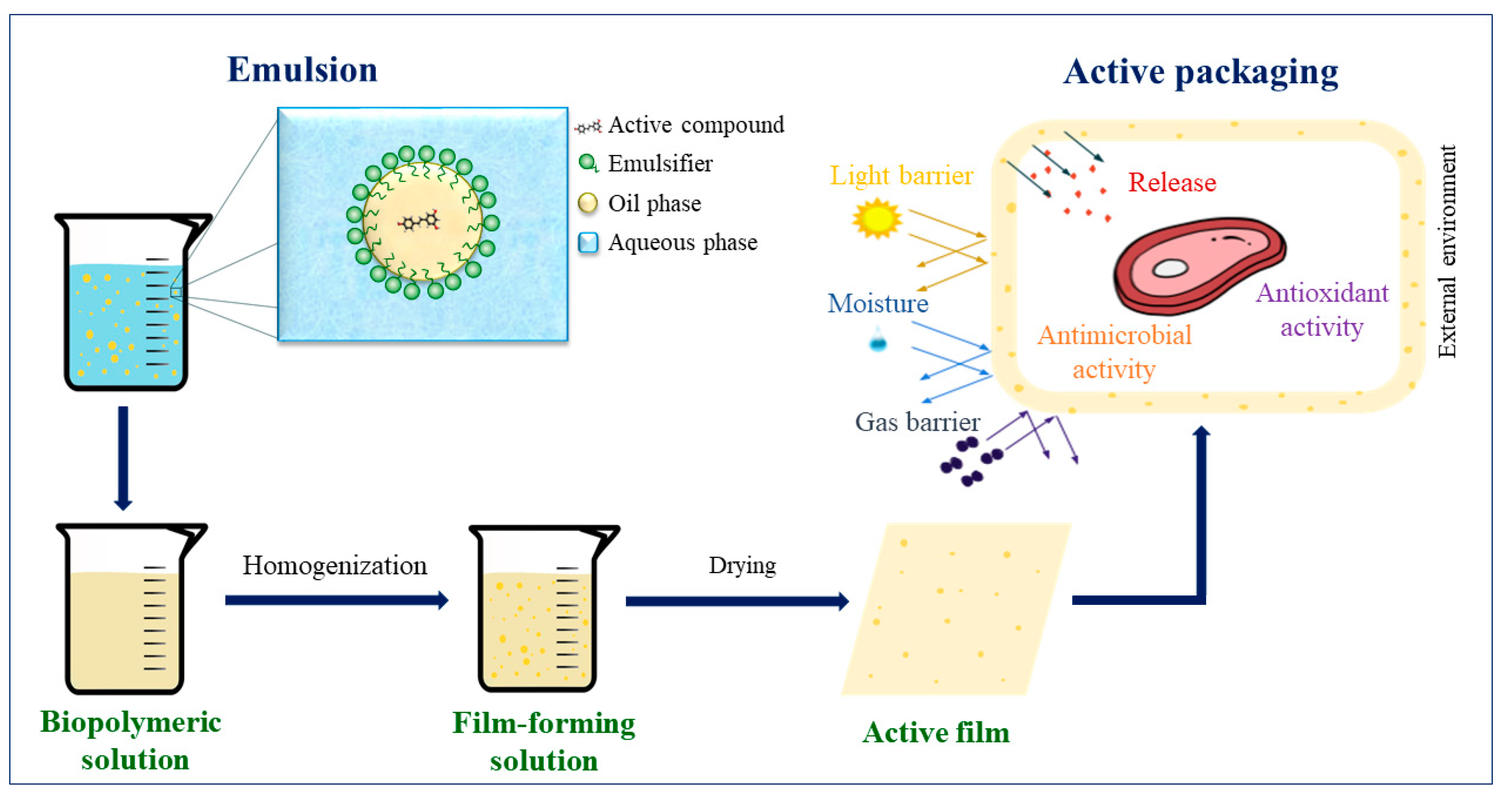

2. Emulsions

3. Films incorporated with bioactive compound-charged emulsions

3.1. Emulsion-encapsulated bioactive compound versus bioactive compound in native form

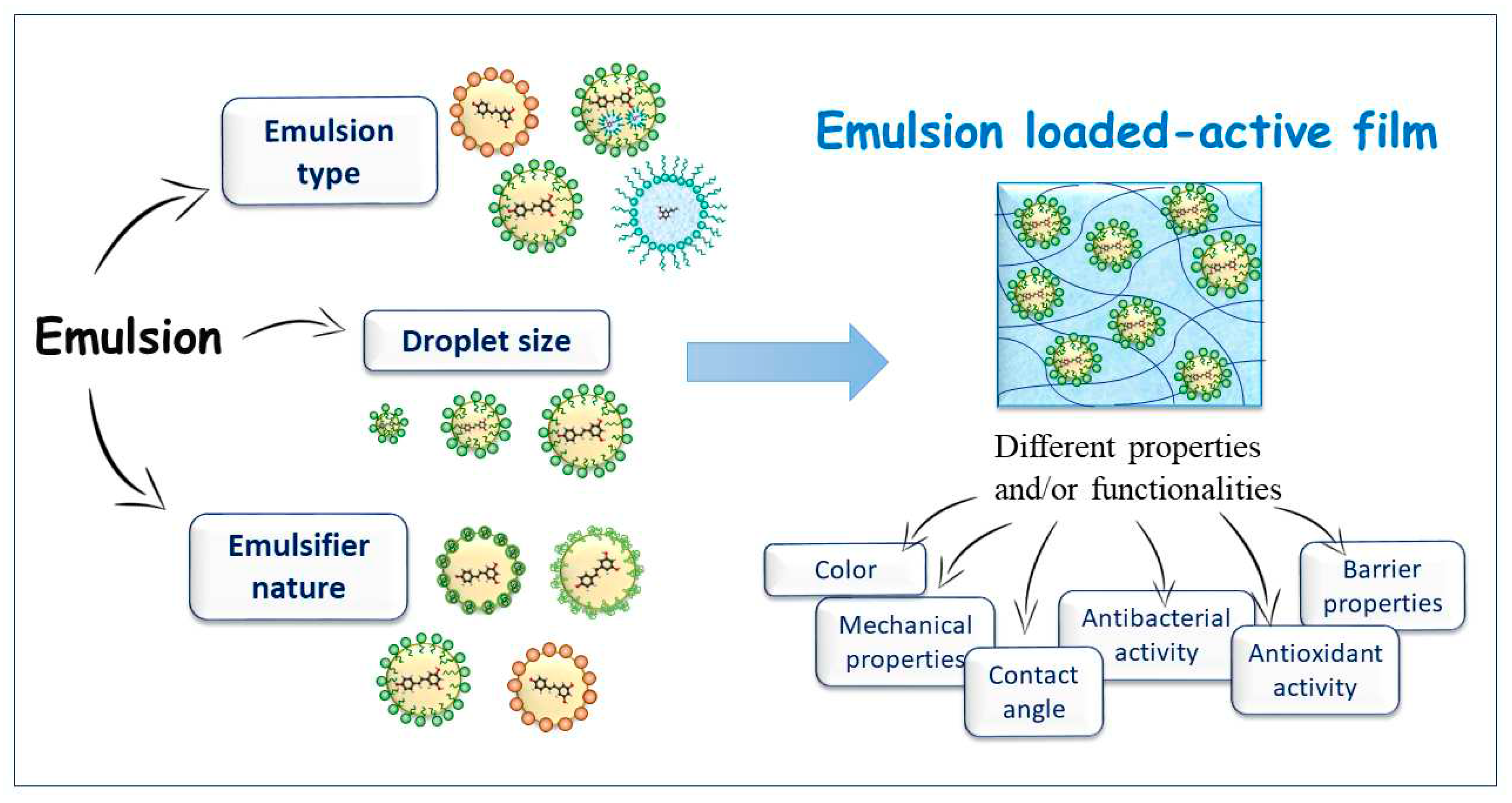

4. Influence of emulsion characteristics in active film properties

4.1. Effect of emulsion type

4.2. Effect of emulsion droplet size

4.3. Effect of emulsifier type

5. Active film stability and bioactive compound retention

6. Release properties in food simulants

7. Applications of active films incorporated with emulsions

8. Final remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rhim, J.W.; Park, H.M.; Ha, C.S. Bio-Nanocomposites for Food Packaging Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 1629–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, E.; Nematollahi, A.; Hosseini, H. Composition of Antimicrobial Edible Films and Methods for Assessing Their Antimicrobial Activity: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanani, Z.A.N.; Yee, F.C.; Nor-Khaizura, M.A.R. Effect of Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.) Peel Powder on the Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Fish Gelatin Films as Active Packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 89, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.F.S.; Martins, J.T.; Duarte, C.M.M.; Vicente, A.A.; Pinheiro, A.C. Advances in Nutraceutical Delivery Systems: From Formulation Design for Bioavailability Enhancement to Efficacy and Safety Evaluation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 270–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainelli, D.; Gontard, N.; Spyropoulos, D.; Zondervan-van den Beuken, E.; Tobback, P. Active and Intelligent Food Packaging: Legal Aspects and Safety Concerns. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, S103–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, C.; Kurek, M.; Hayouka, Z.; Röcker, B.; Yildirim, S.; Antunes, M.D.C.; Nilsen-Nygaard, J.; Pettersen, M.K.; Freire, C.S.R. A Concise Guide to Active Agents for Active Food Packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, B.; Chatha, S.A.S.; Hussain, A.I.; Zia, K.M.; Akhtar, N. Recent Advances on Polysaccharides, Lipids and Protein Based Edible Films and Coatings: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.A.; El-Sakhawy, M.; El-Sakhawy, M.A.M. Polysaccharides, Protein and Lipid -Based Natural Edible Films in Food Packaging: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 238, 116178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammak, I.; Luciano, C.G.; Pérez-Córdoba, L.J.; Monteiro, M.L.; Conte-Junior, C.A.; do Sobral, P.J.A. Advances in Biopolymeric Active Films Incorporated with Emulsified Lipophilic Compounds: A Review. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 28148–28168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiari, S.; Choulitoudi, E.; Oreopoulou, V. Edible and Active Films and Coatings as Carriers of Natural Antioxidants for Lipid Food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, F.; Haghighi, H.; Siesler, H.W.; Licciardello, F.; Pulvirenti, A. Characterization of Chitosan-Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose Blend Films Enriched with Nettle or Sage Leaf Extract for Active Food Packaging Applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 120, 106979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, L.; Gong, X.; Chi, F.; Ma, Z. Fabrication and Comparison of Active Films from Chitosan Incorporating Different Spice Extracts for Shelf Life Extension of Refrigerated Pork. LWT 2021, 135, 110181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, O.L.; Barros Santos, M.C.; Batista, A.P.; Andrigo, F.F.; Baréa, B.; Lecomte, J.; Figueroa-Espinoza, M.C.; Gontard, N.; Villeneuve, P.; Guillard, V.; et al. Active Packaging Films Containing Antioxidant Extracts from Green Coffee Oil By-Products to Prevent Lipid Oxidation. J. Food Eng. 2022, 312, 110744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.C.B.; Cunha, A.P.; da Silva, L.M.R.; Mattos, A.L.A.; de Brito, E.S.; de Souza Filho, M. de S.M.; de Azeredo, H.M.C.; Ricardo, N.M.P.S. From Mango By-Product to Food Packaging: Pectin-Phenolic Antioxidant Films from Mango Peels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Dong, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Song, H. Incorporation of Apricot (Prunus Armeniaca) Kernel Essential Oil into Chitosan Films Displaying Antimicrobial Effect against Listeria Monocytogenes and Improving Quality Indices of Spiced Beef. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, F.; Misaghi, A.; Khanjari, A.; Kamkar, A.; Gandomi, H.; Rezaeigolestani, M. Incorporation of Spice Essential Oils into Poly-Lactic Acid Film Matrix with the Aim of Extending Microbiological and Sensorial Shelf Life of Ground Beef. LWT 2018, 96, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammak, I.; Lourenço, R.V.; do Sobral, P.J.A. Active Gelatin Films Incorporated with Pickering Emulsions Encapsulating Hesperidin: Preparation and Physicochemical Characterization. J. Food Eng. 2019, 240, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tastan, Ö.; Ferrari, G.; Baysal, T.; Donsì, F. Understanding the Effect of Formulation on Functionality of Modified Chitosan Films Containing Carvacrol Nanoemulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 61, 756–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.T.; Pinzon, M.I.; Villa, C.C. Development of Active Edible Films Made from Banana Starch and Curcumin-Loaded Nanoemulsions. Food Chem. 2022, 371, 131121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, C.; Mao, L.; Ma, P.; Liu, F.; Yang, J.; Gao, Y. The Biological Activities, Chemical Stability, Metabolism and Delivery Systems of Quercetin: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 56, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessa, M.; Tsao, R.; Liu, R.; Ferrari, G.; Donsì, F. Evaluation of the Stability and Antioxidant Activity of Nanoencapsulated Resveratrol during in Vitro Digestion. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12352–12360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Dang, S.; Zhang, L.; Munsop, K.; Li, X. Corn Starch/Polyvinyl Alcohol Based Films Incorporated with Curcumin-Loaded Pickering Emulsion for Application in Intelligent Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 188, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogut, E. Active Whey Protein Isolate Films Including Bergamot Oil Emulsion Stabilized by Nanocellulose. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 23, 100430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammak, I.; do Sobral, P.J.A. Effect of Different Biopolymers on the Stability of Hesperidin-Encapsulating O/W Emulsions. J. Food Eng. 2018, 237, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Wadhwa, S.S. Industry-Relevant Approaches for Minimising the Bitterness of Bioactive Compounds in Functional Foods: A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, R.; Seyedain-Ardabili, M. A Comparative Study on the Effect of Homogenization Conditions on the Properties of the Film-Forming Emulsions and the Resultant Films. Food Chem. 2021, 352, 129319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, R.; Wang, J.; Cheng, M.; Lu, W.; Chen, M.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X. Development and Characterization of Corn Starch/PVA Active Films Incorporated with Carvacrol Nanoemulsions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1631–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Córdoba, L.J.; Norton, I.T.; Batchelor, H.K.; Gkatzionis, K.; Spyropoulos, F.; Sobral, P.J.A. Physico-Chemical, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties of Gelatin-Chitosan Based Films Loaded with Nanoemulsions Encapsulating Active Compounds. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, T.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmed, Z.; Ahmad, M.S. Optimization of Soya Lecithin and Tween 80 Based Novel Vitamin D Nanoemulsions Prepared by Ultrasonication Using Response Surface Methodology. Food Chem. 2019, 289, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaci, M.; Belhaffef, A.; Meziane, S.; Dostert, G.; Menu, P.; Velot; Desobry, S.; Arab-Tehrany, E. Nanoemulsions and Topical Creams for the Safe and Effective Delivery of Lipophilic Antioxidant Coenzyme Q10. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2018, 167, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.R.; Xu, W.; Mráz, J. Fabrication, Stability and Rheological Properties of Zein/Chitosan Particles Stabilized Pickering Emulsions with Antioxidant Activities of the Encapsulated Vit-D3. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 191, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, K.; Wang, M. Nano-Emulsion Prepared by High Pressure Homogenization Method as a Good Carrier for Sichuan Pepper Essential Oil: Preparation, Stability, and Bioactivity. LWT 2022, 154, 112779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Food Emulsions: Principles, Practices, and Techniques; 2nd ed.; Boca Raton : CRC Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tessaro, L.; Martelli-Tosi, M.; Sobral, P.J.D.A. Development of W/O Emulsion for Encapsulation of “Pitanga” (Eugenia Uniflora L.) Leaf Hydroethanolic Extract: Droplet Size, Physical Stability and Rheology. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e65320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, R.C.; Gomes, A.; Cunha, R.L. Tailoring W/O Emulsions for Application as Inner Phase of W/O/W Emulsions: Modulation of the Aqueous Phase Composition. J. Food Eng. 2021, 297, 110482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessaro, L.; Luciano, C.G.; Martins, M.F.L.; Ramos, A.P.; Martelli-Tosi, M.; do Amaral Sobral, P.J. Stable and Bioactive W/O/W Emulsion Loaded with “Pitanga” (Eugenia Uniflora L.) Leaf Hydroethanolic Extract. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2022, 43, 1890–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mcclements, D.J.; Wang, J.; Zou, L.; Deng, S.; Liu, W.; Yan, C.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, C.; Liu, C. Coencapsulation of (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate and Quercetin in Particle-Stabilized W/O/W Emulsion Gels: Controlled Release and Bioaccessibility. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 3691–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Lu, K.; Zhou, S.; Qi, B.; Li, Y. Co-Delivery of Insulin and Quercetin in W/O/W Double Emulsions Stabilized by Different Hydrophilic Emulsifiers. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, R.C.; Gomes, A.; Cunha, R.L. Role of Aqueous Phase Composition and Hydrophilic Emulsifier Type on the Stability of W/O/W Emulsions. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Advances in Edible Nanoemulsions: Digestion, Bioavailability, and Potential Toxicity. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 81, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammak, I.; do Sobral, P.J.A. Curcumin Nanoemulsions Stabilized with Natural Plant-Based Emulsifiers. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammak, I.; do Sobral, P.J.A.; Aquino, A.; Neves, M.A. das; Conte-Junior, C.A. Nanoemulsions: Using Emulsifiers from Natural Sources Replacing Synthetic Ones—A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2721–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClements, D.J.; Decker, E.A.; Weiss, J. Emulsion-Based Delivery Systems for Lipophilic Bioactive Components. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, R109–R124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClements, D.J. Nanoemulsions versus Microemulsions: Terminology, Differences, and Similarities. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 1719–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Rao, J. Food-Grade Nanoemulsions: Formulation, Fabrication, Properties, Performance, Biological Fate, and Potential Toxicity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 285–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artiga-Artigas, M.; Guerra-Rosas, M.I.; Morales-Castro, J.; Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Martín-Belloso, O. Influence of Essential Oils and Pectin on Nanoemulsion Formulation: A Ternary Phase Experimental Approach. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 81, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoni, C.G.; Avena-Bustillos, R.J.; Olsen, C.W.; Bilbao-Sáinz, C.; McHugh, T.H. Mechanical and Water Barrier Properties of Isolated Soy Protein Composite Edible Films as Affected by Carvacrol and Cinnamaldehyde Micro and Nanoemulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 57, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Lin, D.; Liu, D.; Yang, X. Emulsions Stabilized by Nanofibers from Bacterial Cellulose: New Potential Food-Grade Pickering Emulsions. Food Res. Int. 2018, 103, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, Q. Recent Advances on Food-Grade Particles Stabilized Pickering Emulsions: Fabrication, Characterization and Research Trends. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 55, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Quinlan, P.J.; Tam, K.C. Stimuli-Responsive Pickering Emulsions: Recent Advances and Potential Applications. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 3512–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peito, S.; Peixoto, D.; Ferreira-Faria, I.; Margarida Martins, A.; Margarida Ribeiro, H.; Veiga, F.; Marto, J.; Cláudia Paiva-Santos, A. Nano- and Microparticle-Stabilized Pickering Emulsions Designed for Topical Therapeutics and Cosmetic Applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 615, 121455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Li, Y.; Kong, F.; Liu, K.; Si, C.; Ni, Y. Lignin-Based Nanoparticles Stabilized Pickering Emulsion for Stability Improvement and Thermal-Controlled Release of Trans-Resveratrol. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 13497–13504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammak, I.; do Sobral, P.J.A. Formulation Optimization of Lecithin-Enhanced Pickering Emulsions Stabilized by Chitosan Nanoparticles for Hesperidin Encapsulation. J. Food Eng. 2018, 229, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Charcosset, C. Encapsulation of Curcumin within Oil-in-Water Emulsions Prepared by Premix Membrane Emulsification: Impact of Droplet Size and Carrier Oil Type on Physicochemical Stability and in Vitro Bioaccessibility. Food Chem. 2022, 375, 131825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aw, Y.Z.; Lim, H.P.; Low, L.E.; Surjit Singh, C.K.; Chan, E.S.; Tey, B.T. Cellulose Nanocrystal (CNC)-Stabilized Pickering Emulsion for Improved Curcumin Storage Stability. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 159, 113249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Weng, W.; Li, B. Characteristics and in Vitro Digestion of Resveratrol Encapsulated in Pickering Emulsions Stabilized by Tea Water-Insoluble Protein Nanoparticles. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozafarpour, R.; Koocheki, A. Fabrication of Emulsion Gels Based on Sonicated Grass Pea (Lathyrus Sativus L.) Protein as a Delivery System for β-Carotene: Kinetic Modeling and Release Behavior. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 184, 115020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, K.C.S.; Vicente, A.A.; Sobral, P.J.A. Development, Characterization, and Stability of O/W Pepper Nanoemulsions Produced by High-Pressure Homogenization. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2018, 11, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, S.; Law, B.; Friedman, M.; Ravishankar, S. Essential Oil Microemulsions Inactivate Antibiotic-Resistant Salmonella Newport and Spoilage Bacterium Lactobacillus Casei on Iceberg Lettuce during 28-Day Storage at 4°C. Food Control 2021, 130, 108209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhu, H.; Feng, Y.; Yu, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, B.; Lin, J.; Miao, W.; Zhou, R.; et al. Emulsions Containing Composite (Clove, Oregano, and Cinnamon) Essential Oils: Phase Inversion Preparation, Physicochemical Properties and Antibacterial Mechanism. Food Chem. 2023, 421, 136201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ding, G.; Dai, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, J.; Qin, J. Anti-Aflatoxigenic Nano-Emulsions Based on Monarda Didyma and Neopallasia Pectinata Essential Oils as Novel Green Agent for Food Preservation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 180, 114777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.; Costa, A.L.R.; Cardoso, D.D.; Náthia-Neves, G.; Meireles, M.A.A.; Cunha, R.L. Interactions of β-Carotene with WPI/Tween 80 Mixture and Oil Phase: Effect on the Behavior of O/W Emulsions during in Vitro Digestion. Food Chem. 2021, 341, 128155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Córdoba, L.J.; Sobral, P.J.A. Physical and Antioxidant Properties of Films Based on Gelatin, Gelatin-Chitosan or Gelatin-Sodium Caseinate Blends Loaded with Nanoemulsified Active Compounds. J. Food Eng. 2017, 213, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norcino, L.B.; Mendes, J.F.; Natarelli, C.V.L.; Manrich, A.; Oliveira, J.E.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Pectin Films Loaded with Copaiba Oil Nanoemulsions for Potential Use as Bio-Based Active Packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 106, 105862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, M.A.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Silva, H.D.; Ramos, P.E.; Azevedo, M.A.; Flores-López, M.L.; Rivera, M.C.; Bourbon, A.I.; Ramos, Ó.L.; Vicente, A.A. Design of Bio-Nanosystems for Oral Delivery of Functional Compounds. Food Eng. Rev. 2013, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garti, N.; McClements, D.J. Encapsulation Technologies and Delivery Systems for Food Ingredients and Nutraceuticals; First.; Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Saelices, C.; Trongsatitkul, T.; Lourdin, D.; Capron, I. Chitin Pickering Emulsion for Oil Inclusion in Composite Films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 242, 116366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonyali, B.; McDaniel, A.; Amamcharla, J.; Trinetta, V.; Yucel, U. Release Kinetics of Cinnamaldehyde, Eugenol, and Thymol from Sustainable and Biodegradable Active Packaging Films. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 24, 100484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Song, F.; Chen, R.; Deng, G.; Cao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wu, H.; Bai, M.; Zhang, P.; Hu, Y. Effect of Cellulose Nanocrystal-Stabilized Cinnamon Essential Oil Pickering Emulsions on Structure and Properties of Chitosan Composite Films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 275, 118704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Rhim, J.W. Gelatin/Agar-Based Functional Film Integrated with Pickering Emulsion of Clove Essential Oil Stabilized with Nanocellulose for Active Packaging Applications. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 627, 127220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chu, Y.; Feng, X.; Gao, C.; Wu, D.; Cheng, W.; Meng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. Effects of Zein Stabilized Clove Essential Oil Pickering Emulsion on the Structure and Properties of Chitosan-Based Edible Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 156, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Wu, J.; Sun, X.; Guo, X.; Zhu, W.; Li, Q.; Shi, X.; Tian, Y.; Wang, S. Physical Properties and Bioactivities of Fish Gelatin Films Incorporated with Cinnamaldehyde-Loaded Nanoemulsions and Vitamin C. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 135, 110103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.F.; Norcino, L.B.; Martins, H.H.A.; Manrich, A.; Otoni, C.G.; Carvalho, E.E.N.; Piccoli, R.H.; Oliveira, J.E.; Pinheiro, A.C.M.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Correlating Emulsion Characteristics with the Properties of Active Starch Films Loaded with Lemongrass Essential Oil. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 100, 105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Filho, J.G. de; Bezerra, C.C. de O.N.; Albiero, B.R.; Oldoni, F.C.A.; Miranda, M.; Egea, M.B.; Azeredo, H.M.C. de; Ferreira, M.D. New Approach in the Development of Edible Films: The Use of Carnauba Wax Micro- or Nanoemulsions in Arrowroot Starch-Based Films. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 26, 100589. [CrossRef]

- Tessaro, L.; Lourenço, R.V.; Martelli-Tosi, M.; do Amaral Sobral, P.J. Gelatin/Chitosan Based Films Loaded with Nanocellulose from Soybean Straw and Activated with “Pitanga” (Eugenia Uniflora L.) Leaf Hydroethanolic Extract in W/O/W Emulsion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 186, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessaro, L.; Luciano, C.G.; Quinta Barbosa Bittante, A.M.; Lourenço, R.V.; Martelli-Tosi, M.; José do Amaral Sobral, P. Gelatin and/or Chitosan-Based Films Activated with “Pitanga” (Eugenia Uniflora L.) Leaf Hydroethanolic Extract Encapsulated in Double Emulsion. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 113, 106523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Hao, X.; Liu, G.; Yue, Y.; Duan, J. A Novel Composite Edible Film Fabricated by Incorporating W/O/W Emulsion into a Chitosan Film to Improve the Protection of Fresh Fish Meat. Food Chem. 2022, 385, 132647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debeaufort, F.; Quezada-Gallo, J.-A.; Voilley, A. Edible Films and Coatings: Tomorrow’s Packagings: A Review. Critcal Rev. Food Sci. 1998, 38, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Ni, Z.J.; Thakur, K.; Zhang, J.G.; Hu, F.; Wei, Z.J. Preparation and Characterization of Clove Essential Oil Loaded Nanoemulsion and Pickering Emulsion Activated Pullulan-Gelatin Based Edible Film. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 181, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao-Sáinz, C.; Avena-Bustillos, R.J.; Wood, D.F.; Williams, T.G.; McHugh, T.H. Nanoemulsions Prepared by a Low-Energy Emulsification Method Applied to Edible Films. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 11932–11938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoni, C.G.; Moura, M.R. d.; Aouada, F.A.; Camilloto, G.P.; Cruz, R.S.; Lorevice, M. V.; de Soares, N.F.F.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Antimicrobial and Physical-Mechanical Properties of Pectin/Papaya Puree/Cinnamaldehyde Nanoemulsion Edible Composite Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 41, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambleton, A.; Debeaufort, F.; Bonnotte, A.; Voilley, A. Influence of Alginate Emulsion-Based Films Structure on Its Barrier Properties and on the Protection of Microencapsulated Aroma Compound. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 2116–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan The, D.; Debeaufort, F.; Voilley, A.; Luu, D. Influence of Hydrocolloid Nature on the Structure and Functional Properties of Emulsified Edible Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbowiak, T.; Debeaufort, F.; Voilley, A. Influence of Thermal Process on Structure and Functional Properties of Emulsion-Based Edible Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2007, 21, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, L.M.; Landgraf, M.; Sobral, P.J.A. Gelatin-Based Films Activated with Red Propolis Ethanolic Extract and Essential Oils. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 27, 100607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Web of Science Web of Science. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/basic-search.

- Zhao, R.; Guan, W.; Zhou, X.; Lao, M.; Cai, L. The Physiochemical and Preservation Properties of Anthocyanidin/Chitosan Nanocomposite-Based Edible Films Containing Cinnamon-Perilla Essential Oil Pickering Nanoemulsions. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 153, 112506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Deng, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, B. Improving the Functionality of Chitosan-Based Packaging Films by Crosslinking with Nanoencapsulated Clove Essential Oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Hou, K.; Gao, C.; Feng, X.; Cheng, W.; Wu, D.; Meng, L.; Yang, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Characterization of Chitosan Film with Cinnamon Essential Oil Emulsion Co-Stabilized by Ethyl-Nα-Lauroyl-l-Arginate Hydrochloride and Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 188, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, H.; Fallah, A.A.; Bonyadian, M.; Abbasvali, M.; Soleimani, M. Effect of Edible Composite Film Based on Chitosan and Cumin Essential Oil-Loaded Nanoemulsion Combined with Low-Dose Gamma Irradiation on Microbiological Safety and Quality of Beef Loins during Refrigerated Storage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Gao, C.C.; Feng, X.; Wu, D.; Meng, L.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. Characterization of Chitosan Based Polyelectrolyte Films Incorporated with OSA-Modified Gum Arabic-Stabilized Cinnamon Essential Oil Emulsions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Critzer, F.; Davidson, P.M.; Zivanovic, S.; Zhong, Q. Physical, Mechanical, and Antimicrobial Properties of Chitosan Films with Microemulsions of Cinnamon Bark Oil and Soybean Oil. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Dong, M.; Li, L.; Jia, P.; Bu, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Development of Functional Gelatin-Based Composite Films Incorporating Oil-in-Water Lavender Essential Oil Nano-Emulsions: Effects on Physicochemical Properties and Cherry Tomatoes Preservation. LWT 2021, 142, 110987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammak, I.; do Sobral, P.J.A. Active Gelatin Films Incorporated with Eugenol Nanoemulsions: Effect of Emulsifier Type on Films Properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 2725–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammak, I.; Carvalho, R.A. de; Trindade, C.S.F.; Lourenço, R.V.; do Sobral, P.J.A. Properties of Active Gelatin Films Incorporated with Rutin-Loaded Nanoemulsions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 98, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandre, E.M.C.; Lourenço, R.V.; Bittante, A.M.Q.B.; Moraes, I.C.F.; do Sobral, P.J.A. Gelatin-Based Films Reinforced with Montmorillonite and Activated with Nanoemulsion of Ginger Essential Oil for Food Packaging Applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2016, 10, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.G.; Ferreira, R.R.; Paula, L.C.; Mitra, S.K.; Rosa, D.S. Starch-Based Films Enriched with Nanocellulose-Stabilized Pickering Emulsions Containing Different Essential Oils for Possible Applications in Food Packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 27, 100615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, S.; Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Liu, D.; Li, X. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Sodium Starch Octenylsuccinate-Based Pickering Emulsion Films Incorporated with Cinnamon Essential Oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 159, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo-Cuartas, C.; Granda-Restrepo, D.; Sobral, P.J.A.; Hernandez, H.; Castro, W. Characterization of Whey Protein-Based Films Incorporated with Natamycin and Nanoemulsion of α-Tocopherol. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadetaj, A.; Almasi, H.; Mehryar, L. Development and Characterization of Whey Protein Isolate Active Films Containing Nanoemulsions of Grammosciadium Ptrocarpum Bioss. Essential Oil. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, M.; Niakousari, M.; Golmakani, M.T. Fabrication and Characterization of Pectin Films Incorporated with Clove Essential Oil Emulsions Stabilized by Modified Sodium Caseinate. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 32, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasi, H.; Azizi, S.; Amjadi, S. Development and Characterization of Pectin Films Activated by Nanoemulsion and Pickering Emulsion Stabilized Marjoram (Origanum Majorana L.) Essential Oil. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 99, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Ren, T.; Harper, D.; Li, M. Development of Antimicrobial Films with Cinnamaldehyde Stabilized by Ethyl Lauroyl Arginate and Cellulose Nanocrystals. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbaryan, S.; Pourfathi, B.; Almasi, H. Reinforcing and Release Controlling Effect of Cellulose Nanofiber in Sodium Caseinate Films Activated by Nanoemulsified Cinnamon Essential Oil. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 21, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lu, L. xin; Qiu, X.; Tang, Y. Controlled Release Mechanism of Complex Bio-Polymeric Emulsifiers Made Microspheres Embedded in Sodium Alginate Based Films. Food Control 2017, 73, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Cai, F.; Lu, P. ZnO Nanoparticles Stabilized Oregano Essential Oil Pickering Emulsion for Functional Cellulose Nanofibrils Packaging Films with Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 190, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, Z.; Xu, F.; Cheng, Y.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Wu, P. Enhancing the Performance of Konjac Glucomannan Films through Incorporating Zein–Pectin Nanoparticle-Stabilized Oregano Essential Oil Pickering Emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Wang, W.; Chu, Y.; Gao, C.; Liu, Q.; Tang, X. Effect of Cinnamon Essential Oil Nanoemulsion Emulsified by OSA Modified Starch on the Structure and Properties of Pullulan Based Films. LWT 2020, 134, 110123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahruie, H.H.; Ziaee, E.; Eskandari, M.H.; Hosseini, S.M.H. Characterization of Basil Seed Gum-Based Edible Films Incorporated with Zataria Multiflora Essential Oil Nanoemulsion. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 166, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, K.; Chen, Y.; Ding, H.; Wu, H.; Gao, Y.; Huang, S.; Wu, H.; Kong, D.; Yang, Z.; et al. Active and Smart Biomass Film Containing Cinnamon Oil and Curcumin for Meat Preservation and Freshness Indicator. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 133, 107979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Tang, C.H.; Yin, S.W.; Yang, X.Q. Development and Characterization of Novel Antimicrobial Bilayer Films Based on Polylactic Acid (PLA)/Pickering Emulsions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 181, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Priyadarshi, R.; Rhim, J.-W. Gelatin/Agar-Based Multifunctional Film Integrated with Copper-Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Clove Essential Oil Pickering Emulsion for Enhancing the Shelf Life of Pork Meat. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Kong, R.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, M. Effect of Glyoxal Concentration on the Properties of Corn Starch/Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Carvacrol Nanoemulsion Active Films. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 171, 113864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, A.; Tonyali, B.; Yucel, U.; Trinetta, V. Formulation and Development of Lipid Nanoparticle Antifungal Packaging Films to Control Postharvest Disease. J. Agric. Food Res. 2019, 1, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Rhim, J.W. Carrageenan/Agar-Based Functional Film Integrated with Zinc Sulfide Nanoparticles and Pickering Emulsion of Tea Tree Essential Oil for Active Packaging Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 2038–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoshal, G. Shivani Thyme Essential Oil Nano-Emulsion/Tamarind Starch/Whey Protein Concentrate Novel Edible Films for Tomato Packaging. Food Control 2022, 138, 108990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, N.; Huang, L.; Cao, G.; Lin, H.; Pang, J.; Mu, R.; Wang, L. Konjac Glucomannan/Pullulan Films Incorporated with Cellulose Nanofibrils-Stabilized Tea Tree Essential Oil Pickering Emulsions. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 650, 129553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiros, Y.; Meneses, A.C. de; Alves, J.L.F.; Mumbach, G.D.; Ferreira, F.A.; Machado, R.A.F.; Bolzan, A.; Araujo, P.H.H. de Xanthan Gum-Based Film-Forming Suspension Containing Essential Oils: Production and in Vitro Antimicrobial Activity Evaluation against Mastitis-Causing Microorganisms. LWT 2022, 153, 112470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shen, R.; Yang, X.; Lin, D. Characterization of a Novel Konjac Glucomannan Film Incorporated with Pickering Emulsions: Effect of the Emulsion Particle Sizes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 179, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Cheng, W.; Feng, X.; Gao, C.; Wu, D.; Meng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. Fabrication, Structure and Properties of Pullulan-Based Active Films Incorporated with Ultrasound-Assisted Cinnamon Essential Oil Nanoemulsions. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 25, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, M.; Moundanga, S.; Favier, C.; Galić, K.; Debeaufort, F. Antimicrobial Efficiency of Carvacrol Vapour Related to Mass Partition Coefficient When Incorporated in Chitosan Based Films Aimed for Active Packaging. Food Control 2013, 32, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boostani, S.; Jafari, S.M. A Comprehensive Review on the Controlled Release of Encapsulated Food Ingredients; Fundamental Concepts to Design and Applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Suaza, L.; Acevedo-Guevara, L.; Sánchez, L.T.; Pinzón, M.I.; Villa, C.C. Characterization of Aloe Vera-Banana Starch Composite Films Reinforced with Curcumin-Loaded Starch Nanoparticles. Food Struct. 2019, 22, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, H.; Peng, Y.; Shi, J.; Wang, Q. Effect of Emulsifier Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balance (HLB) on the Release of Thyme Essential Oil from Chitosan Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 97, 105213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, H.; Rhim, J.W.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Effective Strategies of Sustained Release and Retention Enhancement of Essential Oils in Active Food Packaging Films/Coatings. Food Chem. 2022, 367, 130671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otoni, C.G.; Pontes, S.F.O.; Medeiros, E.A.A.; de Soares, N.F.F. Edible Films from Methylcellulose and Nanoemulsions of Clove Bud (Syzygium Aromaticum) and Oregano (Origanum Vulgare) Essential Oils as Shelf Life Extenders for Sliced Bread. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 5214–5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Córdoba, L.J.; Pinheiro, A.C.; de Núñez de Villavicencio-Ferrer, M.; Trindade, M.A.; Sobral, P.J.A. Applying Gelatine:Chitosan Film Loaded with Nanoemulsified Garlic Essential Oil/α-Tocopherol as Active Packaging of Sliced Omega-3-Rich Mortadella. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 6378–6388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biopolymer | Emulsion type | Active compound | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Pickering | Cinnamon EO | [69] |

| Double emulsion | Nisin/carvacrol | [77] | |

| Pickering | Cinnamon and perilla EO | [87] | |

| Double emulsion | “Pitanga” leaf extract | [76] | |

| Pickering | Clove EO | [88] | |

| Nanoemulsion | Cinnamon EO | [89] | |

| Nanoemulsion | Cumin EO | [90] | |

| Pickering | Clove EO | [71] | |

| Emulsion | Cinnamon EO | [91] | |

| Microemulsion | Cinnamon bark oil | [92] | |

| Nanoemulsion | Carvacrol | [18] | |

| Gelatin | Nanoemulsion | Lavender EO | [93] |

| Double emulsion | “Pitanga” leaf extract | [76] | |

| Nanoemulsion | Cinnamaldehyde | [72] | |

| Pickering | Hesperidin | [17] | |

| Nanoemulsion | Eugenol | [94] | |

| Nanoemulsion | α-tocopherol, garlic essential oil and cinnamaldehyde | [63] | |

| Gelatin | Nanoemulsion | Rutin | [95] |

| Nanoemulsion | Ginger EO | [96] | |

| Starch | Nanoemulsion | Curcumin | [19] |

| Pickering | Ho wood, cardamom, and cinnamon EO | [97] | |

| Emulsion | Lemongrass EO | [73] | |

| Micro and nanoemulsion | Carnauba wax | [74] | |

| Pickering | Cinnamon EO | [98] | |

| Whey protein (WPI) | Nanoemulsion | Bergamot oil | [23] |

| Nanoemulsion | α-tocopherol | [99] | |

| Nanoemulsion | Grammosciadium ptrocarpum Bioss. EO | [100] | |

| Pectin | Emulsion | Clove EO | [101] |

| Nanoemulsion and Pickering | Marjoram EO | [102] | |

| Nanoemulsion | Copaiba oil | [64] | |

| Pickering | Cinnamaldehyde | [103] | |

| Sodium caseinate | Nanoemulsion | Cinnamon EO | [104] |

| Sodium alginate | Emulsion | Cinamon EO | [105] |

| Soy protein isolate | Micro and nanoemulsion | Carvacrol and cinnamaldehyde | [47] |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) | Emulsion | Licorice EO | [26] |

| Cellulose nanofibrils | Pickering | Oregano EO | [106] |

| Konjac glucomannan | Pickering | Oregano EO | [107] |

| Pullulan | Nanoemulsion | Cinnamon EO | [108] |

| Emulsion | Cinnamaldehyde, thymol and eugenol | [68] | |

| Basil seed gum | Nanoemulsion | Zataria multiflora EO | [109] |

| Chitosan/gelatin | Pickering | Cinnamon EO and curcumin | [110] |

| Double emulsion | “Pitanga” leaf extract | [76] | |

| Nanoemulsion | a-tocopherol, cin- namaldehyde and garlic EO | [28] | |

| Nanoemulsion | α-tocopherol, garlic EO and cinnamaldehyde | [63] | |

| Chitosan/Sodium caseinate blend | Nanoemulsion | α-tocopherol, garlic EO and cinnamaldehyde | [63] |

| Chitosan/Polylactic acid bilayer | Pickering | Thymol | [111] |

| Gelatin/agar | Pickering | Clove EO | [70] |

| Pickering | Clove EO | [112] | |

| Gelatin/pullulan | Nanoemulsion and Pickering | Clove EO | [79] |

| Starch/PVA | Pickering | Curcumin | [22] |

| Nanoemulsion | Carvacrol | [113] | |

| Nanoemulsion | Carvacrol | [27] | |

| Pectin/Papaya puree | Nanoemulsion | Cinnamaldehyde | [81] |

| Pullulan/xanthan gum/locust bean gum | Nanoemulsion | Cinnamaldehyde, thymol and eugenol | [114] |

| Carrageenan/agar | Pickering | Tea tree oil | [115] |

| Tamarind starch/WPI | Nanoemulsion | Thyme EO | [116] |

| Konjac glucomannan/pullulan | Pickering | Tea tree EO | [117] |

| Property | Emulsion type | Droplet size | Emulsifier | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emulsion | Nanoemulsion | Pickering | Smaller | Bigger | |||

| WVP | Decreased | - | Increased | - | - | - | [69] |

| - | Decreased | Decreased | - | - | - | [79] | |

| - | Decreased | Decreased | - | - | - | [102] | |

| - | - | - | Decreased | Increased | - | [26] | |

| - | - | - | Decreased² | Decreased | - | [74] | |

| - | - | - | Decreased | Increased | - | [87] | |

| - | - | - | Decreased | Decreased² | - | [119] | |

| - | - | - | Decreased³ | [89] | |||

| Moisture absorption/ content | - | Increased | Decreased | - | - | - | [79] |

| - | - | - | No effect | No effect | - | [74] | |

| - | - | - | No effect | Decreased² | - | [119] | |

| - | Increased | Decreased | - | - | - | [102] | |

| Water contact angle | Increased | - | Increased | - | - | - | [69] |

| - | - | - | Increased | Increased | - | [119] | |

| - | - | - | No effect | No effect | - | [74] | |

| Surface roughness | - | Decreased | Increased | - | - | - | [79] |

| - | - | - | No effect | Increased | - | [26] | |

| - | - | - | Increased | Decreased² | - | [119] | |

| Tensile strength | Decreased | - | Decreased | - | - | - | [69] |

| - | Decreased | Increased | - | - | - | [79] | |

| - | Decreased | Increased | - | - | - | [102] | |

| - | - | - | Decreased² | Decreased | - | [26] | |

| - | - | - | No effect | Decreased | - | [87] | |

| - | - | - | Decreased² | Decreased | - | [119] | |

| - | - | - | Decreased² | Decreased | - | [74] | |

| - | - | - | - | - | Increased³ | [89] | |

| - | - | - | - | - | Increased4 | [94] | |

| Elongation at break | Decreased | - | Decreased | - | - | - | [69] |

| - | Increased | Decreased | - | - | - | [79] | |

| - | No effect | Increased/ decreased* | - | - | - | [102] | |

| - | - | - | Increased | Increased² | - | [26] | |

| - | - | - | Increased | Decreased | - | [87] | |

| - | - | - | Increased | Increased | - | [74] | |

| - | - | - | - | - | Decreased³ | [89] | |

| - | - | - | - | - | Decreased4 | [94] | |

| UV-vis light barrier | Decreased | - | Decreased | - | - | - | [69] |

| - | - | - | Increased | Increased² | - | [74] | |

| - | - | - | Increased | Increased² | - | [87] | |

| - | - | - | Increased² | Increased | - | [119] | |

| Antioxidant activity1 | - | Highest | Lowest | - | - | - | [79] |

| - | Highest | Lowest | - | - | - | [102] | |

| - | - | - | Highest | Lowest | - | [87] | |

| - | - | - | - | - | Highest4 | [94] | |

| Antimicrobial activity1 | No effect | - | Effect | - | - | - | [69] |

| No effect | No effect | - | - | - | [102] | ||

| - | - | - | Higher effect | Lower effect | - | [26] | |

| - | - | - | - | - | Higher effect³ | [89] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).