1. Introduction

Melanoma is a multifactorial disease and by far the most aggressive and dangerous skin cancer. Melanoma arises from transformed melanocytes and has the highest mutational and heterogeneous profile of any cancer, partially attributed to UV induced DNA damage and/or DNA replication errors (Eddy et al., 2021). Although melanoma accounts for less than 2% of global cancer diagnoses, it is responsible for 80% of skin cancer deaths with a growing incidence over the past decades (Castellani et al., 2023). A variety of treatments for melanoma are available; however, current or emerging chemotherapies have a limited success rate. Adjustments and switches are usually required due to the several phases of tumoral initiation and progression that leads to multidrug resistance and anti-tumor immunity. This emphasizes the importance of discovering new compounds that are safe and effective against melanoma and to use versatile technologies that can evolve against cancer advances (Chinembiri et al., 2014).

Approximately 60% of anticancer drugs are from natural origin (Cragg and Newman, 2013). Natural products have significant chemotherapeutic potential as drugs leads. However, it is a challenge to natural-based drugs cross the skin. The biological and physical characteristics of this tissue determine the responsiveness and resistance to stressful environmental factors and therapeutic treatments. While epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin, is constantly exposed to UV rays from sunlight and highly susceptible to DNA damage, the stratum corneum, the innermost layer, is a potent barrier against substance penetration due to hyperkeratinization. It limits a drug's pharmacological performance and delivery at a deep skin level. The main challenge is to increase the cutaneous penetration capacity of drugs in an effective concentration to produce a targeted tumor cytotoxicity (Laikova et al., 2019).

Despite the skin’s formidable permeability challenges, it remains an accessible interface for the delivery of therapeutic carriers such as nanoemulsions (Duarte et al., 2023). Nanotherapeutic approaches have been focused on the topical delivery of bioactives due to the ability to enhance the penetration of substances through the epidermis. The nanometric size of the droplets is a preeminent factor in promoting the transport of substances across skin layers. Nanoemulsions are delivery vehicles which can strongly interact with the stratum corneum and manipulate its barrier properties. Operating as nanocarriers, they allow the released drugs to navigate through the lipid domains for deeper accumulation and diffusion into the skin. This procedure increases drug retention in the tumor microenvironment, resulting in reduced dosage, minimal toxicity, stability, solubility and bioavailability (Krishnan and Mitragotri, 2020)

The discoveries of anticancer substances derived from natural products are still excellent prospects for exploring bioactives of natural origin applied to therapeutic technologies (Patridge et al., 2016). In this way, nanostructured systems are able to act as an interface between cells and natural compounds, optimizing their interactions. Few studies correlated the use of natural-based nanoemulsions focused on melanoma which can attract scientific interest in the nano-oncology field as an promising strategy in melanoma cancer therapy (Suh et al., 2009). A deeper understanding of the influence of chemical and physical properties of the nanocarriers has the potential to enhance the anticancer action of natural products. The nanoemulsions’ biocompatibility and their ability to target site-specific locations during drug delivery are strongly influenced by their structure and physicochemical properties modulating the interactions to the cellular biological components, affecting the safety and effectiveness of the developed nanosystem (Oliveira et al., 2022). Parameters such as structure, size and surface chemistry determine protein binding affinities, interaction with membranes, cellular internalization and impact on intracellular processes in transdermal delivery applications (Lagoa et al., 2019).

2. Melanoma Microenvironment

The understanding of key molecular events are essential to design nanotherapies that target specific steps involved in melanoma and enhance drug response rates. Wan, Jin and Wang (2020) identified seven hallmarks differentially activated in melanoma: UV response up, reactive oxygen species pathway, glycolysis, mTORC1 signal, E2F targets, unfolded protein response and DNA repair. The landscape of cancer pathways in melanoma supply an accurate prediction for the prognosis of the skin cancer.

Tumor formation is not only the malignant growth of cells but also associated changes in its microenvironment to support malignant proliferation and eventual metastasis. Stroma of melanoma is a compilation of cells including fibroblasts/myofibroblasts, endothelial cells, infiltrating immune cells, vascular and smooth muscle cells, soluble growth factors and ECM proteins. In general, quiescent fibroblasts get activated in response to the tissue damage and secrete growth factors to support tissue repair. Normal dermal fibroblasts repress the growth of early stage or metastatically incompetent primary lesions. However, a small number of metastatically competent cells overcome this resistance and show proliferative advantage upon coculture with normal dermal fibroblasts (Mundra et al., 2015).

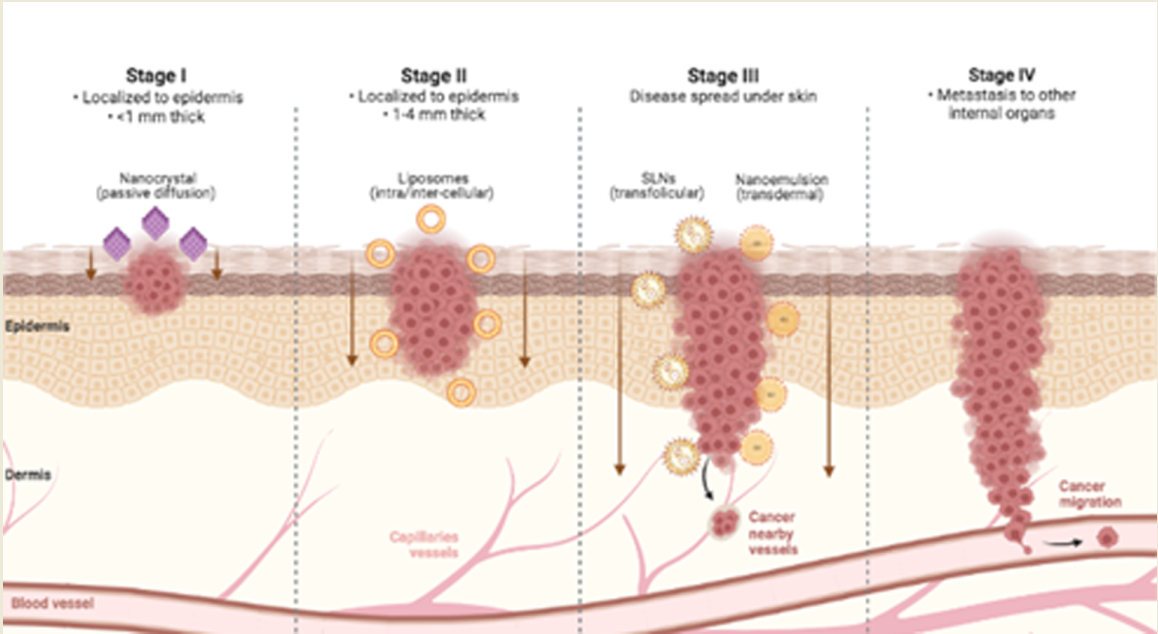

Cutaneous melanoma results from the malignant transformation of melanocytes. Melanocytes are cells distributed throughout the body in the basal layer of the epidermis with the photoprotective function of producing melanin pigment. Melanin is transported to the keratinocytes and accumulated in their supranuclear region protecting them from ultraviolet (UV)-induced DNA damage. When keratinocytes mature, a phenomenon called keratinization occurs before they die. Both dead cells and melanin perform a skin-protective external barrier process (CHESSA et al., 2020). Melanocytes acquire an initiating driver mutation during the breakthrough phase which leads to hyperplasia and nevi development. Then, some of the melanocytic nevi progress into intermediate lesions and overtime develop into melanoma in situ during the expansion phase which is initially restricted to the epidermis. As the tumor progresses and accumulates mutations, primary melanoma enters the invasive phase and becomes malignant melanoma reaching the dermis and further becoming metastatic (Eddy et al., 2021) (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Skin cancer permeation of mainly used nanocarriers for topical delivery according to tumor progression. Created with BioRender.com.

Figure 2.

Skin cancer permeation of mainly used nanocarriers for topical delivery according to tumor progression. Created with BioRender.com.

Amplification of melanocytes, abnormal growth with presentation of tissue invasion and metastasis, unlimited replicative potential, delay of cellular apoptosis, self-sufficiency of growth factors, insensitivity to growth inhibitors, and sustained angiogenesis are some characteristics presented by melanoma. These coefficients can be stimulated by oncogenic factors or by the suppression of genes to inhibit the tumor. Some alterations in signaling pathways, such as MAPK, PI3K/PTEN/PKB, and MITF, are essential contributors to the pathogenesis of melanoma. The pathogenesis involves the selective growth of cells with favorable mutations, genetic instability, and other factors such as mutagenesis, genetic predisposition, and suppression of the host's immune response (Lugović-Mihić, 2019).

Melanoma heterogeneous profile is also conducted by phenotypic predisposition genes and driver mutations. The high-penetrance susceptibility genes involved in melanoma are CDKN2A (cyclin-dependent kinase 2A) and CDK4 (cyclin-dependent kinase 4) which plays a role in cell cycle regulator and represents 20 to 40% of gene mutations (Rossi et al., 2019). BRAF mutations act as a key player of genetic instability in melanoma with the highest mutational rate among cancer types and pathogenetic variants occurring in about 50% of malignant melanoma with over 95% of BRAF mutations including the V600E mutation, which cause the substitution of glutamic acid for valine at residue 600 of the protein. Mutations in BRAF lead to constitutive activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, which in turn mediates several phenomena, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and secretion of signal molecules, related to melanoma occurrence and progression (Castellani et al., 2023). NRAS codes for a small guanine triphosphate (GTP)-binding protein. RAS oncogenes with activating mutations have been observed in a third of all human cancers, 15–20% of melanomas carry NRAS mutations. The subset of melanomas with NRAS mutations is more aggressive compared to the absence of NRAS mutations. BRAF and NRAS are two of the most common driver mutations, but also mutually exclusively mutated, oncogenes recognised in melanoma (Laikova et al., 2019).

3. Natural-Based Anticancer Compounds Against Melanoma

Nature is a source of an abundant pool of diverse chemicals and pharmacologically active compounds. Medicinal value of natural products comes from co-evolutionary interactions among millions of species that have produced a large repertoire of defense molecules. The screening of molecules and complex mixtures from diverse biological sources has shown anticancer potential (Dinić et al., 2018).

According to the FDA, natural products are substances obtained from plants, animals, or microorganisms, whether extracted, purified, or processed in any other way, but that have not had their chemical structure significantly altered. From 1940 to 2014, in a report by Patridge and colleagues (2016), 68% of all 136 small-molecule anticancer drugs available were natural products based.

From the 17 natural products constituents of the nanoemulsions presented in this review, 16 are from plants and 1 from animal which shows phytochemicals as a large source for nanoemulsion-based anticancer agents corroborating literature data (Fontana et al., 2019). Among them, there are different classes of organic compounds as bioactive principles found in this review in this work: 4 polyphenols (daidzein, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, procyanidin, chlorogenic acid), 4 oils (bullfrog oil, açaí oil, coffee oil-algae oil, thyme essential oil), 3 terpenoids (fraxinellone, oleanolic acid and ursolic acid), 2 alkaloids (camptothecin and piplartine), 1 quinone (quinizarin) and 1 extract (Tectona grandis leaves extract). The most cited country was Brazil which highlights its incredible biodiversity and effort to fight melanoma through topical natural-based nanoemulsions approach.

The main advantages researched in natural products are their inherent biocompatibility and reduced toxicity, suggesting a tumor-selective property. All natural-based nanoemulsions described in Table 1 were non-toxic or less toxic in normal skin cell lineages (fibroblasts (NIH/3T3; CCD-986SK; PCS-201-012; HSF and keratinocytes HaCaT) compared to tumoral melanoma experimental models.

| Natural Product |

Melanoma |

Nanoemulsion |

Study |

| Substance |

Source |

Cell lineage |

Main results |

Mechanism of action |

Hydrodynamic size (nm) |

Polydispersity index (PdI) |

Zeta potential (mV) |

Encapsulation efficiency |

pH |

Stability period |

Associated Strategy |

Main results |

Ref |

| Bullfrog oil |

Rana catesbeiana |

in vitro

3T3

B16F10 |

Bullfrog oil showed concentration and time-dependent cytotoxicity against B16F10 cell lineage. At 100 µg/mL, the viability of B16F10 cells was reduced over the time. |

Bullfrog oil is internalized in the droplet, requiring more time to be delivered to the cellular membrane promoting a great inhibition of cell growth |

390 nm |

0.05 |

−25 mV |

|

5.0 (±1.6) to 5.6 (±1.4) |

90 days at 25 °C, −5 °C, 45°C

|

- |

Both the bullfrog oil itself and its topical nanoemulsion did not show cytotoxicity in 3T3 linage. However, these systems showed growth inhibition in B16F10 cells suggesting that this system would be a potential anti-melanoma agent |

Amaral-Machado, 2016 |

| Açaí oil |

Euterpe oleracea Martius |

in vitro NIH/3T3 B16F10

in vivo C57BL/6

|

Cell lines presented 85% cell death (617 μg/mL) for melanoma cells, while maintaining high viability in normal cells. Tumor bearing C57BL/6 mice treated five times (50mg oil /mL) with PDT using acai oil in nanoemulsion showed tumor volume reduction of 82% in comparison to control/tumor group |

Flow cytometry indicated that cell death occurred by late apoptosis/necrosis |

117.5 ± 2.44 nm |

0.144 |

-0.536 mV |

|

|

180 days at 7°C, 25 °C, 50 °C and -20 °C

1 year at 7°C and 25°C

|

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) |

Acai oil in nanoemulsion was an effective photosensitizer presenting significant cell killing and tumor reduction properties, representing a promising source of new photosensitizing molecules for PDT treatment of melanoma. This suggests a novel and powerful tumor-selective tool useful as adjuvant therapy for surgical procedures |

Monge- Fuentes, 2017 |

| extract from Tectona grandis leafs |

Teca tree |

in vitro B16F10

NIH3T3 |

The optimal conditions to treat B16F10 were to use TGE-NE containing 0.25 mg/ml of TGE under illumination with the red light LED |

Generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) |

18.61 nm |

0.109 |

-10.9 mV |

|

|

30 days at 4°C, 25°C and 37°C |

Photodynamic therapy (PDT)

|

Both free and nanostructured presentations possess the ability to sensitize B16 F10 cells to red light of the LED in vitro. The TGE-NE showed reasonable photocytotoxicity and was much less toxic toward normal cells in the dark compared to free TGE |

de Menezes Furtado, 2017 |

| coffee oil-algae |

coffee grounds / algae |

in vitro HACAT

B16F10 |

Animal experiments showed that a dose of 0.1% coffee oil-algae oil nanoemulsion was effective in mitigating trans-epidermal water loss, skin erythema, melanin formation, and subcutaneous blood flow. Cytotoxicity test implied effective inhibition of melanoma cell growth by nanoemulsion with an IC50 value of 26.5 µg/mL and the cell cycle arrested at G2/M phase. DHA-containing nanoemulsion prepared was effective in inhibiting UVA-induced inflammation of HaCaT cells through PPAR activation |

B16-F10 to undergo early apoptosis, late apoptosis, or necrosis. The expressions of p53, p21, cyclin B, cyclin A, Bax, and cytochrome C were upregulated, while that of CDK1,CDK2, and Bcl-2 were downregulated in a dose-dependent manner, accompanied by an increase in the activities of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9 for apoptosis of melanoma cells B16-F10 |

36.7± 0.2nm |

|

-72.72±3.61 mV |

100% DHA |

6 |

90 days at 4°C |

UV irradiation |

This nanoemulsion was efficient in ameliorating TEWL, skin erythema, and melanin formation, as well as subcutaneous blood flow rate during irradiation of mice. In addition, this nanoemulsion was effective in inhibiting melanoma cell growth with the cell cycle arrested at G2/M phase |

Yang, 2017 |

| fraxinellone (Frax) |

root bark of Dictamnus dasycarpus

|

in vitro

BPD6 (Murine BRAF-mutant melanoma)

in vivo

C57BL/6

|

Frax NE can efficiently accumulate in the tumor site after systemic administration. A significant decrease in TAFs and stroma deposition was observed and also remolded the tumor immune microenvironment, as was reflected by an increase of natural-killer cells, cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) as well as a decrease of regulatory B cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

Apoptosis.

T helper 1 (Th1) cytokines of interferon gamma (IFN-γ), which effectively elicit anti-tumor immunity, were enhanced. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) and interleukin 6 (IL6), which inhibit the development of anti-tumor immunity, were reduced

|

148.1 ± 1.3 nm |

|

|

90% |

|

20 days at 25°C |

combined with BRAF peptide vaccine (oral)

target ligand aminoethyl anisamide (AEAA)

|

Frax NE improves the antitumor effect and reprograms TAFs when combined with BRAF peptide vaccine in stroma-rich melanoma.

Apoptosis of neighboring tumor cells caused by combination therapy of Frax NE and BRAF peptide vaccine induces an antigen-specific immune response.

Remodeling of the TME and enhanced immune cell infiltration resulted in the superior antitumor effect of the combination therapy |

Hou, 2018 |

| curcumin |

plant Curcumin longa

|

in vitro B16F10

in vivo

C57BL/6

|

The pharmacokinetic study showed that the encapsulation of curcumin inside nanoemulsions increased the total drug exposure amount (AUC0-∞), elimination half-life (T1/2), peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and biodistribution of the drug in various vital organ. The antitumor efficacy study illustrated that the application of ultrasound reduced the tumor volume and relative growth rate of the tumor. IC50

1.15 ± 0.13 µM (CurNE)

|

Ca2+ dependent expression of apoptotic inducer and curcumin would have synergistically increased the population of late apoptotic cells27. Moreover, the increased uptake of curcumin inside cells due to presence MB and ultrasound would have enhanced the signal cascade responsible for the apoptosis of cells. Ultrasound exposure also generates ROS |

60 to 120 nm |

|

-20 to -45 mV |

77 to 99% (ratios) |

|

|

ultrasound pulses

oral and IV adm |

Cur_NE from different ratios of lecithin and curcumin were developed and characterized. The ratio 2:1 showed higher internalization. The developed nanoemulsions were biocompatible with normal fibroblast cell lines and showed reduction of tumor size.. The oral delivery of the formulation followed by MB injection and ultrasound treatment provides a unique modality of oral chemotherapy for the treatment of cancer. |

Prasad, 2020 |

| Astaxanthin (AST) + peanut oil |

Haematococcus pluvialis algae |

in vitro Human foreskin fibroblasts

Caco-2 cells

B16F10

in vivo

C57BL/6

|

Fibroblasts had cell growths greater than 90% at peanut oil concentrations lower than 50% (v/v) in Figure 2(b), and the peanut oil was not toxic. After AST dosage within the nanoemulsion reached 53 μg/mL, the cell viability declined gradually. Nanoemulsion gradually reduced oxidative stresses in a dose-dependent manner because it inhibited the production of cellular ROS. After being treated with TAP-nanoemulsion in an oral form, the metastatic melanoma of the lung was reduced appreciably |

Nanoemulsion triggered apoptosis of human malignant melanoma in the lung by inhibiting Bcl-2, cyclins D1 and E, NF-κB, ERK, MEK, and MMP-1 and MMP-9 and increasing cleaved caspase-9 and caspase-3, ATM, and p21. |

~150 nm |

0.144 |

|

99% |

2.0 to 6.0 |

6 months |

oral |

AST suppressed melanoma proliferation via apoptotic mechanism in vitro and in a xenograft model, and the lung metastatic melanoma inhibition by the oral nanoemulsion administration. In particular, the expressions of three proteins (cyclin E, MEK, and MMP-1) were reduced with the addition of TAP-nanoemulsion. Overall, we confirm that TAP-nanoemulsion effectively reduced the growth of melanoma and induced lung metastatic melanoma apoptosis in mRNA and proteins. |

Haung, 2020 |

| epigallocatechin gallate + olive oil |

green tea |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nano-EGCG formulations had enhanced stability and produced greater suppression of melanoma tumor growth and angiogenesis compared with free EGCG |

Sudha, 2022 |

|

Thymus vulgaris L. (thyme) essential oil (TEO) |

Thymus vulgaris |

in vitro

A375

normal human skin fibroblast (HSF)

|

Nano is not toxic for RAW 264.7 cells and the NO suppressive action of it at the highest dose was not due to its cytotoxicity impact. Higher skin permeability of nano could be attributed to the high positive charge density of its nanodroplets, which enables it to be strongly attached to the negatively charged cell membrane of rat skin. Among all the NEs, the AOC coated NE (AOC-NE3) showed the most potent antiproliferative activity against the A-375 cancer cells, with an IC50 value of 14.38 ± 1.05 µg/mL |

The cytotoxicity assay revealed that all of the nanoemulsions can induce a dose- and structure-dependent decrease in the proliferation of melanoma cells (A-375). All the tested samples have the capacity to reduce “NO” production having anti-inflammatory activity |

179.03 to 193.91 nm |

0.19 to 0.23 |

21.83 to 24.91 |

78.6 to 91.5% |

4.5 and 7.2 |

7 days at 25°C |

- |

Among all the nanoformulations, the AOC-coated NE is the most stable one. In addition, the protective layer has significantly increased transdermal delivery of the secondary NEs. Consequently, AOC-NE3 had a transdermal delivery 1.5 times greater. AOC-NE3 exhibited excellent selectivity for melanoma cells over the healthy cells, as revealed by its selectivity index (SI = 5.02). The AOC coated nanoemulsion technology can be employed to deliver lipophilic active components transdermally |

Nasr, 2022 |

| Camptothecin + coconut oil |

Camptotheca acuminata |

melanoma cells |

Nanoemulsions provide a lipophilic environment which allows for high camptothecin loading and good stability of the drug within the droplets before release. Perfluorocarbon nanoemulsions showed the slow release of camptothecin. Ultrasound was effective to affect the droplets, thus releasing the bioactive drug at specific sites. The camptothecin-loaded nanoemulsions are capable to show cytotoxicity against melanoma cancer cells in vitro. |

The acidic extracellular environment leads to a pH gradient unique to tumor cells. This gradient favors the uptake and retention of camptothecin and its derivatives. Camptothecin incorporated into nanoemulsions composed of perfluoropentane exhibited growth-inhibiting activity in melanoma cells |

220– 420 nm |

- |

- 60 to - 75 mV |

> 90% |

4.2–5.5 |

- |

Microbubbles with Liquid perfluorocarbon |

Acoustically active nanoemulsions are a promising drug-targeting system for camptothecin, and may also allow reductions in dosage and decreases in systemic toxicity. |

Fang, 2009 |

| daidzein |

isoflavone found in soybeans and other legumes |

in vitro SK-MEL30 PCS-201-012 |

All formulations maintained the cytotoxic effect of DZ against the melanoma cells for 24 and 48 h of incubation periods. the cytotoxicity study performed using the human fibroblast cell line showed that there were no signi ficant cytotoxic effects of the DZ concentrations used |

Cell viability assay also revealed that DZ-NE formulation (equivalent to 270 μM of DZ) induced signi ficant cell death compared with pure DZ |

151.12 to 220.25 nm |

0.222 to 0.311 |

-22.57 to 19.35 |

- |

4.53–5.54 |

15 days at 4 °C and 25 °C |

- |

The results obtained suggest that the NE and NEG formulations with a controlled release profile and nanometer droplet size may be useful for the topical use of DZ and the treatment of skin cancer. Additional studies to provide the long-term stability of DZ in the NEs and NEGs formulations might be performed |

Ugur Kaplan, 2019 |

| Piplartine (PPTN) with chitosan or sodium alginate |

alkaloid amide found in Piper species |

in vitro (2D e 3D) SK-MEL-28 |

The cytotoxicity of piplartine was ~2.8-fold higher when the drug was incorporated in the chitosan-containing NE compared to its solution (IC50 = 14.6 μM) against melanoma cells. The effects of this nanocarrier on 3D melanoma tissues were concentration-related; at 0.5% piplartine, caused disorganization of the epidermis and formation of intracellular vacuoles, with very few cells remaining, at 1% piplartine elicited marked epidermis destruction |

Polysaccharides improved piplartine penetration into and across the skin in a similar manner, increasing the ratio “drug in the skin/receptor phase”. |

78.1 to 121 nm |

0.22 to 0.25 |

-23.3 to 8.3 |

- |

- |

90 days at 25 °C |

- |

Despite the interest in piplartine encapsulation, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the potential of nanocarriers to improve the cutaneous localization of the drug. Even though the effect was more pronounced in the melanoma tissue, the healthy skin equivalent was also affected, demonstrating the importance of delivering piplartine topically to the tumor lesions to avoid cytotoxic effects to healthy sites

|

Giacone, 2020 |

| Procyanidin |

Avocado peel |

In vitro

melanoma 41 B16F10 cells

non-cancerous 40 human cells (HEK293) |

decrease in melanoma B16F10 cells with IC50 = 52 ± 2 µg/mL.

Was not significant for HEK293 |

Intracellular Proc-Nem could significantly interfere with the redox balance of tumor cells, contributing to a decrease in cellular viability |

≈160 nm |

≤ 0,1 |

± -50mV |

≈97% |

|

90 days |

- |

The nanoformulation containing avocado peel extract, procyanidins (Proc-Nem); a residue with important biological potential as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anticancer compound. (Proc-Nem) was stable under various biological and storage conditions and could be converted into a reconstitutable dry powder. Proc-Nem is safe on non-cancerous cells and effective in killing cancer cells (B16F10 cells) and preventing their malignant migration.

|

1 |

| Bullfrog oil |

Adipose tissue of the amphibian Rana Catesbeiana Shaw |

In vitro melanoma cells A2058

|

The nanosystems decreased mitochondrial activity by up to 92 ± 2% (p < 0.05). |

The study showed that free BFO induced cell apoptosis, while all nanostructured systems caused cell death through necrosis associated with an overproduction of ROS |

401±28.0 nm ± SD |

0.40±0.08 ± SD |

-28.0 ± 2 mV SD |

- |

|

- |

- |

The results allowed us to conclude that these nanosystems facilitated the bullfrog oil permeation in the melanoma cells, promoting a ROS over production and inducing cell death by necrosis, while the free BFO was able to induce melanoma cell death by late apoptosis |

2 |

Quinizarin

|

Bark of the Cinchona officinalis tree |

In vitro B16F10

cell lines fibroblastoids NIH-3T3 |

Was no significant toxic effect on NIH-3T3 cells up to concentrations of 56 µg.mL− 1

Both quinizarina and quinizarina nanoemulsion with Whey Protein and polymethylmethacrylate were cytotoxic at the concentration 268 μg mL− 1, while both associated with Photodynamic Therapy had cytotoxicity at the concentrations from 167 μg mL− 1 to 222 μg mL− 1

|

- |

≥ 305

≤ 388 |

≥ 0.43

≤ 0.62 |

≥ 31.7 mV

≤ 41.4 mV

|

80% |

|

130 days |

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) |

Atomization by nanospray drying proved efficient and offered advantages for industrial scaling. The uptake assay showed that the polymeric nanoparticle containing Quinizarin was more internalized by cells than free Quinizarin, demonstrating the high cell biocompatibility and drug delivery characteristics of the formulation for use as biological material. |

3 |

| Chlorogenic acid |

Coffee, tea, fruits, vegetables |

B16F10 |

On Melanoma B16 cells, it was determined that the finalized CA-NE formulation reduced tyrosinase activity and melanogenesis activity. |

- |

105 nm to 121 nm |

<0,3 |

-4.67 to -22.96 mV |

|

|

>60 days |

- |

In vitro and in silico findings, due to anti-tyrosinase and anti-melanogenesis efficacy and safety profile with non-mutagenic/non-toxic properties, chlorogenic acid nanoemulsion can be suggested as an innovative skin whitening formulation for cosmetic application |

4 |

| Oil of Linum usitatissimum L. and H. tiliaceus partially purified extract |

Linum usitatissimum |

B16F10 |

The substances exerted high efficacy in suppressing melanin content and tyrosinase activity in murine melanoma cells and inhibited 34% and 32% extracellular melanogenesis at 0.5 mg/mL

|

- |

~434 nm to ~520nm

|

0,27 |

-55mV to -67mV |

- |

|

>3 months |

-- |

- |

5 |

| Levan |

Zymomonas mobilis ZAG 12

|

B16F10 |

Viability below 25% at concentrations 125, and 250 µg/ mL |

- |

244 ± 2 nm |

0,122 |

−12 ± 1 mV |

- |

|

- |

Poly-isobutyl cyanoacrylate |

The obtained nanoparticles showed antiproliferative activity against MDA-MB-231 and B16F10 strains with cytotoxic activity superior to free levan. |

6

|

| Oleanolic Acid (OA) and Ursolic Acid (UA) |

Plumeria obtusa |

B16F10 |

The natural mixture incorporated into the NEm showed cytotoxic activity from 2.9 µM |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ultraviolet irradiation |

pentacyclic triterpenes loaded in a NEm system could be considered as a new potential tool for further investigation as anticancer agents |

Alvarado, 2018 |

Polyphenols are natural antioxidants and one of the most abundant organic classes presented in this review. Inflammation has a critical role in the initiation of tumor microenvironments inducing the transcription of various pro-proliferative and anti-apoptotic genes. The anticancer and the cytoprotective properties of polyphenols are generally attributed to their antioxidant and pro-oxidant properties. Polyphenols are able to generate ROS in cancer cells that lead to induction of apoptosis, suppression of cell cycle and down-regulation of proliferation through modulation of several signaling pathways (Fernandes, 2023). Daidzein (DZ) is an isoflavone, a subclass of flavonoids, has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, and also inhibits the growth of the cancer cells. Flavonoids are an important group of the polyphenolic compounds found in nearly every part of plants. In the study performed by Ugur-Kaplan and colleagues (2019), pure and nanoformulated DZ had no cytotoxic effect on the normal dermal fibroblasts. Polyphenol epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) EGCG is the main antioxidant compound in green tea. Nano-EGCG formulations had enhanced stability and produced greater suppression of melanoma tumor growth and angiogenesis compared with free EGCG (Sudha et al., 2022).

Natural oils have a renewable character, low toxicity, high biodegradability, and presence of substances with pharmacological activity. The chemical compositions of oils, also known as lipids, comprise mainly triglycerides with various fatty acid chains and small fractions of free fatty acids. Lipids, together with proteins and carbohydrates, are among the most vital nutrients for living organisms. Chemically, lipids are hydrophobic and sometimes amphiphilic molecules, allowing themselves to arrange in the biophysical environment as bilayer structures. They are likely involved in different cellular signaling pathways related to cell metabolism proliferation, and apoptosis. Specific lipids also contribute to maintaining the structure and function of skin from the surface to the hypodermis, where each layer contains different types of lipids with important roles to play. The stratum corneum comprises approximately 10 – 20% free fatty acids, 25% cholesterol, and 50% ceramides (sphingolipids) that together with corneocytes and other proteins contribute to the normal barrier properties of the skin (Fernandes et al., 2023).

Polyphenols act as ROS generators due to the presence of phenolic compounds which exert antioxidant actions on normal cells and pro-oxidant actions on tumor cells. These ROS cause oxidative damage to cancer cells, leading to cell death. It was shown by Monge-Fuentes (2017) with açai nanoemulsion that exhibits the ability to eradicate melanoma cells while preserving the viability of normal cells. Many types of cancer cells have a greater quantity of lipid receptors in their cell membranes in comparison to normal cells. Approximately 70% of açai oil is composed by fatty acids which facilitate the incorporation into target cells. Açai nanoemulsion did not have a significant impact on NIH/3T3 viability, maintaining 81.7% of fibroblasts viable. Oliveira (2022) highlighted that the cytotoxicity of bullfrog oil is related to the fatty acids present in this chemical composition since they are able to promote the viability reduction of tumor cells due to damage to the cellular membrane. The mechanism of action is still under investigation, but it is believed to involve the inhibition of cell proliferation through apoptosis, induction of oxidative stress in tumor cells, and modulation of the immune system by activating antibodies against cancer cells. Both the bullfrog oil itself and its topical nanoemulsion did not show cytotoxicity in 3T3 lineage (Amaral-Machado et al., 2016).

Algae oil rich in docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and coffee oil is a rich source of linoleic acid, both fatty acids possessing anticancer and anti-inflammation functions. Yang and Hung (2017) showed the cell viability of HaCaT remained unaffected when treated with coffee oil-algae oil nanoemulsion without irradiation. However, following UVA irradiation, the cell viability declined to 30%. Conversely, with 0.01% nanoemulsion treatment, the cell viability rose to 44.8%. Similarly, following UVB irradiation, the cell viability decreased to 40% and remained unaffected even after treatment. Thus, the DHA-containing nanoemulsion was effective in inhibiting UVA-induced inflammation of HaCaT cells through PPAR activation. The CCD986SK cell viability dropped to 83.9%, implying a slight inhibition effect at high dose coffee oil-algae oil nanoemulsion. Among essential oils, thyme essential oil (TEO) extracted from Thymus vulgaris L. (thyme) has a long history of pharmacological uses as well as favorable organoleptic properties. More than 75% of the ingredients of (TEO) are oxygenated compounds. Its suitable anticancer activity occurs through DNA fragmentation and cell apoptosis. These beneficial effects are mostly due to the presence of numerous identified chemotypes bioactives ingredients. A research from Nasr and colleagues (2022) showed that nanoemulsions with TEO associate to chitosan exhibited lower antiproliferative effects on the HSF cells as compared to their antiproliferative effects on the melanoma cells (A-375) under the same testing conditions.

Terpenoids, also known as terpenes, represented here by fraxinellone (Hou et al., 2018), oleanolic acid and ursolic acid (Alvarado et al., 2018) are a diverse large class of organic compounds found in plants, fungi, and some animals, characterized by a specific carbon skeleton composed of multiple isoprene units. Terpenes play important roles in the biosynthesis of plant secondary metabolites, such as essential oils and pigments. They interact with specific biological targets, such as enzymes, receptors, ion channels, and can also modulate signaling pathways involved in various cellular processes, including apoptosis, proliferation, and cell differentiation. In particular, the use of terpenes as adjuvant therapy in melanoma treatment has gained attention due to their ability to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents and reduce their toxicity (Wróblewska-Łuczka et al., 2023). Alkaloids such as camptothecin (Fang et al., 2009) and piplartine (Giacone et al., 2020) represent a highly diverse group of compounds containing cyclic structures with at least one basic nitrogen atom being incorporated within. These compounds have a wide distribution in the plant kingdom with diverse chemical structures showing varied cytotoxicity. Alkaloids exhibit a promising role as anticancer agents by restraining the enzyme topoisomerase which is associated with the replication of DNA, instigate apoptosis, and modulate various other intracellular targets and signaling pathways (Mondal et al., 2019). Based on the studies reported in Table 1, cytotoxic tests in normal cells by terpenoids and alkaloids were not evaluated.

Anthraquinones are important structurally diverse dyes belonging to the quinone family and their derivatives display various pharmacological activities. The uptake assay done by Gobo and colleagues (2022) showed that the polymeric nanoparticle containing QZ was more internalized by cells than free QZ, demonstrating the high cell biocompatibility and drug delivery characteristics of the formulation for use as biological material.

Menezes-Furtado (2017) focused on plant extracts. Due to the heterogeneity, plant extracts pharmacological effects are plural. Thus, the Tectona grandis leafs (TGE) extract showed that cytotoxicity towards fibroblasts cells (NIH/3T3) in the dark sharply decreased when TGE is used in association with nanoemulsions in photodynamic therapy strategy.

Natural compounds have been extensively studied by their chemopreventive potential. Their anti-proliferative, pro-apoptotic, anti-invasive and anti-angiogenic effects are showed in melanoma. Inhibition of tumor-promoting proteins and activation of tumor-suppressing cascades are the main molecular mechanisms involved in the anticancer ability of bioactives from natural origin. Moreover, a considerable number of studies reported the synergistic activity of phytochemicals and standard anti-melanoma agents (Fontana et al., 2019). All the natural products presented in this review are related to modulatory key events in melanoma through inhibition of cell division, interference in DNA replication and induced cell death pathway.

4. Nanoemulsion-Based Topical Delivery Systems

4.1. Structure

Nanoemulsions are biphasic liquid systems kinetically stable on a nanometric scale (Tadros, 2004). Its composition typically consists of three main parts: water, oil, and surfactant. Basically, the hydrophilic phase and the hydrophobic phase are dispersed through the other by shearing mechanical force that separates the phase into miniscule spherical droplets. Due to immiscible liquids character an interface is created between the two phases making the system thermodynamically unstable. Then, surfactants are added to the system as a critical step to stabilize the droplets (Wilson et al., 2022).

The properties of the surfactants control the stability of emulsions. Surfactants work at the interface between oil and water to reduce the surface tension and act as a steric barrier to avoid the fusion of nanodroplets which is driven by the system attempting to reach a state of minimal free energy. Due to the thermodynamically instability of nanoemulsions systems, they trend towards separation into two discrete phases over time. When stabilized by surfactants this time frame is extended essentially rendering nanoemulsions kinetically stable to have prolonged shelf life retaining its original properties. It is important to design reliable nanoemulsion formulations which will be exposed to stress conditions (pH, temperature, serial dilution) and/or long-term storage for therapeutic applications (Kabalnov, 1998; Wilson, 2022).

Surfactants for nanoemulsion drug delivery must be non-toxic and effectively stabilize the oil-water interface in biological media. They can interact with cell membranes and enhance drug penetration. Small molecule surfactants are the most abundantly utilized emulsifiers as they are cheap, readily synthesized with well understood surface properties. Small molecule surfactants have a head–tail morphology: a hydrophobic tail with a hydrophilic head. Small molecule surfactants are categorized by the charge of the head group into anionic, cation and non-ionic surfactants. The majority of surfactants presented in this review are non-ionic surfactants described to have uncharged polar head functional groups and typically composed of PEG combined to a fatty acid tail. It can be explained by their smaller toxicity compared to anionic and cation surfactants which is essential for biological applications where the focus is to reduce adverse effects (Wilson et al., 2022).

Another type of surfactants covered by some works in this review were phospholipids such as phosphatidylcholine and soy lecithin (Fang et al., 2009; Hou et al., 2019). As the major component of cell membrane, they have a great biocompatibility and good long-term stability. They also have a head–tail morphology characterized by a positively charged phosphate head and two fatty acid tails. Phospholipids stabilize emulsions in two ways: first, by providing an electrostatic repulsion between droplets and second, and acting as a steric barrier increasing the thermodynamic energy required to coalesce (Wilson et al., 2022). The combination of non-ionic and phospholipids surfactants was suggested by Ugur-Kaplan and colleagues (2019).

The respective hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity of the head and tail groups of surfactants can be expressed by their hydrophilic–lipophilic balance (HLB). A HLB value <10 describes a surfactant that is oil soluble and >10 a surfactant that is water soluble and is used to determine whether a surfactant can form W/O or O/W emulsions, respectively (Greth & Wilson, 1961).

Overall, all nanoemulsions from data Table 1 were oil-water (o/w) formulations. The natural products were loaded in the core structure as a way to protect them against degradation and to increase the bioavailability. The surrounded oil phase in aqueous phase overcomes lipophilicity from bioactives and enhances skin solubility. The stabilized o/w interface by surfactants allows biocompatibility and less adverse effects. The focus on topical treatments with nanoemulsions reduces systemic toxicity and dosage of components.

4.2. Size

Despite the structure of the nanosystem, the size of nanodroplets is a fundamental physicochemical parameter to ensure nanoemulsion stability and transdermal permeation of drugs. Size determines the available surface area which allows rapid penetration and drug loading of actives through skin at deeper levels. Nanometric droplets may facilitate the interaction with the cell membrane, increasing the membrane fluidity and the internalization of the bioactives creating a biodistribution profile. In this entry route, size is determinant in the binding and activation of membrane receptors, as well in the eventual expression of the proteins (Danaei et al., 2018). Nanosystems need to enter cells and diffuse through the cytosol to access the particular cytoplasmic targets where the sites of action are located (Oliveira, 2022). Previous studies had stated that the permeation potential of nanoemulsions was high due to its small droplet size. In addition, the number of droplets that could interact with stratum corneum would increase as the droplet size decreased (Ugur-Kaplan, 2019).

Nanoemulsions droplet size ranges from 10 to 1000 nm. However, the majority of nanocarriers cover the size range from 50 to 200 nm. Nanocarriers with a size of ∼50 nm are internalized more efficiently and have the greatest cellular uptake with slightly larger, >60 nm, and smaller, <20 nm, particles being rapidly cleared by the renal and reticuloendothelial systems. Related to cellular uptake pathways, small nanoparticles <200 nm are taken by pinocytosis and ∼250 nm by phagocytosis (Foroozandeh & Aziz, 2018). Larger particles will lead to an increase in the clearance rate. The uptake of nanocarriers with a size of 500 nm has a lower viability but may be promoted with the use of a constructive, complementary delivery system. Since human bodycells vary from 1–100 µm, the influence of nanometric size is also dependent on the type of cell target (Pillay, 2015).

The size of nanoemulsions covered by this review ranges from 18,61 nm of the Tectona grandis leaves extract to 420 nm of camptothecin. Half of nanoemulsions presented sizes between 50 and 200 nm, two were below 50 nm and six were above 200 nm. According to Danaei and colleagues (2018), particle size ranges from 10 to 600 nm for transdermal route of administration, then, all nanoemulsions covered in this review are inside diameter parameters for skin drug delivery.

The polydispersity index (PDI) or heterogeneity index is a measure to describe the degree of non-uniformity of a size distribution of particles and is related to the drug encapsulation rates. Values range from 0.0 to 1.0, nonetheless, in drug delivery applications a PDI of 0.3 and below is considered to be acceptable (Danaei, 2018). In particular, the polydispersity index is one of the main indicators of droplet growth caused by Ostwald Ripening effect. The presence of large droplets and small droplets together increases the size of the resulting droplets due to dissolution and mass transfer (Ugur-Kaplan, 2019). With exception of quinizarin (Gobo et al., 2022) and bullfrog oil (BFO) (Oliveira et al., 2022), all natural-based nanoemulsions presented in this review that had their PDI measured showed values according to the acceptable for nanocarriers application (PDI ≤ 0.3).

4.3. Surface Charge

The balance between the attractive van der Waals forces and the electrical repulsion in phase droplets influences the nanoemulsion therapeutic target once the system’s surface charge can facilitate the contact to the cell membrane. The Zeta potential is a scientific term for electrokinetic potential in colloidal systems, and a measure of surface charge indicating the electrostatic stability of nanosystems. It contributes to cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of drug delivery (Honary and Zahir, 2013).

The binding on the cell membrane followed by the internalization of bioactives is directly associated with surface charge. The surface charge of nanodroplets determines bio-nano interactions. The negatively charged cancer cell membrane enhances the uptake of positively charged nanoparticles which potentialize the electrostatic interaction and can be more effective in terms of retained effect and tumor diffusion. In particular, positively charged nanoparticles have higher internalization than neutral and negatively charged ones. However, the uptake of positively charged nanocarriers may disrupt the integrity of cell membrane and lead to an increase in toxicity. Neutrally charged nanocarriers reduce the cellular uptake as compared to negatively charged ones. Moreover, the internalization of negatively charged nanocarriers leads to gelation of membranes, while positively charged ones cause fluidity. In addition to the uptake rate, surface charges also affect the uptake mechanisms. More specifically, positively charged nanocarriers are mainly internalized by the cell via macropinocytosis whereas clathrin-/caveolae-independent endocytosis is the mechanism for the uptake of negatively charged nanocarriers (Foroozandeh & Aziz, 2018)

As a general rule, zeta potentials between ≥ 30 mV and ≤60 mV in absolute values maintain a stable nanosystem. Zeta potential ≥ ±30 mV indicates that the repulsive forces are greater than the attractive ones, keeping monodisperse droplets, while ~ ±20 mV are prone to have only short-term stability. However, low values < 5 mV tend to aggregate rapidly as a result of the attractive forces. Extremely positive or negative zeta potential values cause larger repulsive forces, whereas repulsion between particles with similar electric charge prevents aggregation of the particles and accordingly ensures easy redispersion (Németh, 2022)

According to Table 1, all natural products were negatively charged, except by thyme essential oil and quinizarin. Açaí oil (Monge- Fuentes, 2017), Tectona grandis leaves extract (Menezes Furtado, 2017), daidzein (Ugur Kaplan, 2019) and Levan (Silva, 2023) presented zeta potential values below ±20 mV which may induces nanoemulsion droplets aggregation over time despite stability tests.

Nanosystems with different types or ratios of components can alter the sensitivity to fusion with cancer cells. Hence it is important to design suitable formulations for drug delivery and therapeutic benefits (Fang, 2009). Rational design of the nanostructure composition taken together with their nanometric droplets distribution and surface charge enhances the skin permeation of nanoemulsions at a deep level. The surfactants keep a stable nanosystem, large superficial areas create better contact with the stratum corneum and balanced forces facilitate membrane interactions, respectively. Incorporate co-surfactants and additives is possible to minimize the surfactant dosage, enhance stability, physicochemical properties and therapeutic effect of natural products. All these properties make nanoemulsions an ideal platform for topical drug delivery (Duarte et al., 2023).

5. Nanoemulsions to Overcome Natural-Based Against Melanoma

The understanding of the role of nanostructures in the cellular machinery are fundamental to evolve these nanotherapeutic approaches. The choice of drugs and their combination is important since synergism optimizes therapeutic potential without increasing the dose of individual agents. An ideal drug delivery system maintains the bioactive within a desired therapeutic release after a single dose and targets the drug to a specific region while simultaneously lowering the systemic levels of the drug. (Lagoa et al., 2019).

Nanostructures carriers are used in order to ensure controlled delivery of active substances into the skin and have distinct advantages over free drugs including improved bioavailability, stability against degradation, reduced clearance and unique biological interactions (Wilson, 2022). Free drugs circulate throughout the body and permeate the cell membrane through passive diffusion. This nonselective distribution and cellular permeability of anticancer drugs is the primary reason for dose-limiting toxicity (Mundra, Li and Mahato, 2015).

According to the studies analyzed in this review, nanostructured systems increased the therapeutic effect of natural products. It is noteworthy that most of them were more effective with less quantity of substance compared to their free form. It corroborates with the literature on nanocarrier-mediated enhancement of cytotoxicity for natural products agents (Fontana et al., 2019). Nanometric droplets need much less bioactive to act. The reduction in dosage is a huge advantage since commercialization of natural compounds for cancer treatment may result in excessive exploration of natural resources and technique problems with producing a consistent quantity and quality substance. The rational use of natural products is essential for its viability and sustainability. Moreover, the release of free natural drugs can be highly toxic and not direct, targeting non-tumoral cells (Chinembiri, 2014). Despite these advantages, there are few commercially available options for melanoma topical management. This motivated studies with nanoemulsions for cutaneous delivery of cytotoxic natural agents (Giacone, 2020).

Drug Delivery and Natural Products Pharmacokinetics

From the data presented in this review, we list three main abilities common in all studies related to nanoemulsion potential as a delivery system of natural products: structure able to internalize unstable and hydrophobic bioactives, nanometric droplet size to overcome cellular barriers and slow release of the drug in the cell interior. These properties make nanoemulsions effective drug delivery vehicles for natural products enhancing skin permeation and optimizing therapeutic effects.

Drugs with low water solubility require cosolvent for their administration and cause systemic toxicity, whereas water-soluble drugs are rapidly eliminated through kidney restricting the plasma residence time for their partition to tumor. Overcome hydrophobicity is one of the main concerns about natural products and ligand interactions can be critical for effective solubilization of these drugs into skin (Mundra, Li and Mahato, 2015).

Studies of Amaral-Machado (2016) nanostructured bullfrog oil (BFO) to improve its non-degradable organoleptic characteristics and low permeation through the skin to increase its therapeutic effect and maintain its safety to non-tumoral cells. In a continuous work, Oliveira (2022) revealed BFO emulsified nanosystems increase the ability to deliver BFO across all cellular compartments due to the increase of BFO droplets surface contact to the cells, enhancing its interaction to the cell membrane or its cell uptake. It may lead to a different cell death pathway melanoma lineage. Additionally, the emulsified systems showed a higher increase in BFO cytotoxic effect, which can be associated with their composition, surfactant concentration, and droplet size. The study showed that free BFO induces apoptosis, while nanostructures cause cell death by necrosis via super production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). This difference can be explained by the greater ability of nanosystems to distribute BFO in all cellular compartments, intensifying its effect It highlights how structure and physicochemical parameters of nanoemulsions can influence therapeutic effects.

In an effort to overcome insolubility, instability, and toxicity of camptothecin clinical application, Feng and colleagues (2009) loaded this phytochemical in a liquid perfluorocarbons and coconut oil core. Despite the high lipophilicity, nanoemulsions showed an encapsulation level of >90% for camptothecin loading. The entrapment of camptothecin in nanoemulsions retarded the drug’s release and showed higher cytotoxicity than the free drug according to in vitro tests, even with less bioactive.

Nanocarrier-mediated improvement of the cytotoxicity of other lipophilic drugs, such as fraxinellone (Frax), Oleanolic Acid (OA) and Ursolic Acid (UA), Daidzein, Açaí oil, piplartine. Possible justifications for the cytotoxicity enhancement when the drug was incorporated in the nanocarrier include the more efficient delivery and the nanocarrier ability to reduce precipitation of lipophilic drugs in the culture medium, suggesting formulation efficacy. (Giacone, 2020).

To overcome hydrophobicity, Frax was loaded in a combination of surfactants with oils by Hou (2018). The small size facilitated the uptake of nanoparticles due to the binding with the cell surface, as a result more AEAA-modified nanoemulsion entered cells with overexpressed sigma receptors enhancing tumor-target ability of Frax. Nanoemulsified Frax improved its pharmacokinetics profile and did not produce any adverse reactions at the tested dosage levels, though administered for a long time. Other natural products such as Oleanolic Acid (OA) and Ursolic Acid (UA) also had their cell incorporation enhanced in a nanoemulsified form through nanometric particle size diffusion. The antioxidant and anticancer activities of OA/UA mixture nanoemulsions were higher when incorporated into a nanoemulsion, possibly being due to the synergistic action that the castor oil phase gives to these natural compounds. (Alvarado, 2018)

In the same way, Ugur-Kaplan and colleagues (2019) nanoemulsified Daidzein (DZ) to overcome its poor water solubility and low partition coefficient of oil/water. As a result, DZ nanoemulsions increased droplet surface area and residence time at topical application due to the slow drug release of nanodroplets. DZ nanoemulsions were more stable in terms of physical and active substance stability than the conventional DZ emulsions. In addition, they suggest a gelation process to increase the viscosity of nanoemulsions.

Nanostructured systems are commonly used as photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy (PDT), a widely known strategy to treat skin cancer. Açaí oil was nanoemulsified to overcome hydrophobicity. The small sized and monodisperse nanodroplets enable greater permeability into biological tissues facilitating cell uptake and leading to widespread damage to organelles. It also allowed low dark cytotoxicity (Monge-Fuentes, 2017). Conversely, toxicity of nanostructured extract of Tectona grandis leafs (TGE) was reduced toward normal cells in the dark compared to free TGE. The ability of a nanoemulsion to avoid or minimize toxic effects of a natural product when there is no exposure of the cell to red light is an important aspect for photodynamic therapy since it protects skin from sensibilization (Menezes-Furtado, 2017). Gobo and colleagues (2022) concluded that higher the quinizarin (QZ) concentration and the higher LED light fluence, statistically greater the induction of B16F10 cell death as compared to the control.

The characteristics and potentials of chitosan as well as its capability to form extremely stable chitosan-coated secondary make it a very attractive platform to formulate stable nanoemulsion delivery systems. However, chitosan’s limited aqueous solubility has limited its widespread use in the formulation of nanoemulsions. Nasr and colleagues (2022) modified the surface properties of thyme oil nanoemulsions by coating them with an oppositely charged biopolymer oligochitosan and also lecithin, offering a promising strategy for improving the stability and applicability of nanoemulsions. When using this approach, a multilayer nanoemulsion is formed generating mutual electrostatic and steric repulsive interactions that can prevent aggregation forming a suitable dispersion. This chitosan-lecithin nanosystem had a transdermal delivery 1.5 times greater than primary nanoemulsion. Nanoemulsion multilayers adhesion showed that mixing different emulsifiers can create multifunctional nanoplatforms for effective transdermal delivery of bioactives.

Giocone (2020) promoted the incorporation of polysaccharides in nanoemulsions as a way to optimize piplartine cutaneous delivery. Piplartine's physicochemical characteristics, which include low molecular weight (317.3 g/mol) and a logP of 2.4, make it a good candidate for topical administration, although they often require larger amounts of surfactants/co-surfactants. Chitosan and sodium alginate are bioadhesive polymers able to adhere to mucous membranes, however, with opposite charge. The polysaccharides improved piplartine penetration into and across the skin (1.3–1.9-fold) in a similar manner, increasing the ratio “drug in the skin/receptor phase” by 1.4–1.5-fold compared to the plain nanoemulsion and highlighting their relevance for cutaneous localization. Alginate was less effective at improving the electrical stabilization of the nanoemulsion. Chitosan bioadhesive ability has been attributed mainly to electrostatic interactions with negatively charged surfaces which may be responsible to maintain droplet size and zeta potential more stable than sodium alginate over time. The concentration of piplartine necessary to reduce cell viability to 50% (IC50) was approximately 2.8-fold lower when it was nanoencapsulated in NE-C-OA (5.1 μM) compared to its solution (14.6 μM), demonstrating an increase in piplartine cytotoxicity against melanoma.

Oleic acid addition as an oil phase component to the chitosan-containing nanoemulsion further increased drug penetration (~1.9–2.0-fold), as did increases in drug content from 0.5 to 1%. The effects of this nanocarrier on 3D melanoma tissues were concentration-related; at 1%, piplartine elicited marked epidermis destruction. Since piplartine is a lipophilic compound, a possible reason for cutaneous localization is the affinity to skin and/or formulation components (that are partitioned in the tissue). Other possible explanations for nanocarrier-mediated skin targeting involve the rapid drug release when the drug is associated with the nanocarrier surface (and interface, in the case of nanoemulsions), and formulation adsorption at the membrane of cutaneous cells. These results support how the structure is important to enhance physicochemical properties and to increases pharmacokinetics of natural products in nanoemulsions.

It has been shown that phenolic compounds, when incorporated into polymeric nanoparticles, enhance anticancer effects. Sudha and colleagues (2022) synthesized a nanoformulation using the natural biopolymer chitosan to encapsulate polyphenol epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) to improve its bioavailability. Nanoparticles made up of biodegradable and biocompatible polymers such as chitosan have been extensively utilized due to their ability to control the time and rate of release of the incorporated compound improving bioavailability. Free EGCG is very susceptible to oxidation, which starts during direct contact with air. In addition to EGCG’s strong antioxidative activity, it undergoes auto- oxidation to form reactive oxygen species, resulting in polymerization and decomposition that leads to ineffective bioavailability. Additionally, EGCG is unstable under visible and UV light illumination, losing hydrogen atoms, leading to auto-oxidation. The release kinetics showed a constant release of EGCG, indicating the efficiency of the preparation method to provide sustained activity. EGCG loading in nanoparticles can protect it from adverse environmental conditions, delay its degradation and improve its bioavailability. EGCG encapsulated in chitosan has been shown to have higher stability than free EGCG.

In this concern, all systems showed the ability to improve the natural products effect without affecting its safety, which can be explained by the physicochemical characteristics (size, PdI, and zeta potential), stability (kinetic and thermodynamic), and composition (biocompatible compounds) of each nanostructured system. Therefore, nanoemulsions have been designed to overcome natural products limitations, thus enhancing their therapeutic potential, by promoting the capacity of these natural-based drugs (Lagoa et al., 2019).

6. Conclusions

In this review we present results of articles that exhibited natural-based nanoemulsion strategies to overcome melanoma heterogeneity and mutational profile. Nanoemulsified bioactives are more effective in tumor experimental models than free natural drugs. We focused on convert standard and reproducible methods to evaluate nanoemulsions structure and pharmacochemical parameters. Moreover, natural products were associated with their class common biocompatibility and antimelanoma activity. With this study, we aim to contribute to increase the current arsenal of topical nano-based formulations applicable for pharmacological skin cancer management.

More studies and fundamental understanding of the complex interactions between nanoemulsions and biological systems will accelerate the translation of their real clinical applications. We suggest that future studies should focus on the advancement of clinical trials that may confirm the safety and effectiveness of such natural-based nanosystems, thus developing more reliable and accessible topical treatments for melanoma. Integrating multiple models and computational approaches emerge as key opportunities to advance melanoma therapy discovery.

Author Contributions

IOA and CMC participated mainly in the draft, organizing the topics, and actualizing the literature and writing. IVGS and GSP wrote data of skin cancer. RAC revised the cancer topics. RE and MAFS analyzed data and revised drug delivery topics. GPFL contributed to the study's conception and design, and supervised, and revised the study. All the authors revised and approved the final version to be published.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq); Carlos Chagas Filho Research Support Foundation (FAPERJ); Programa de Oncobiologia - Fundação do Câncer.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare relevant to this article's content.

References

- Suh, W.H.; Suh, Y.-H.; Stucky, G.D. Multifunctional nanosystems at the interface of physical and life sciences. Nano Today 2009, 4, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Pellegrini, C.; Cardelli, L.; Ciciarelli, V.; Di Nardo, L.; Fargnoli, M.C. ; Discab; L’aquila; Rome; Italy Familial Melanoma: Diagnostic and Management Implications. Dermatol. Pr. Concept. 2019, 9, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddy, K.; Shah, R.; Chen, S. Decoding Melanoma Development and Progression: Identification of Therapeutic Vulnerabilities. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, N.; Yin, C.; Zhu, B.; Li, X. Ultraviolet Radiation and Melanomagenesis: From Mechanism to Immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, G.; Buccarelli, M.; Arasi, M.B.; Rossi, S.; Pisanu, M.E.; Bellenghi, M.; Lintas, C.; Tabolacci, C. BRAF Mutations in Melanoma: Biological Aspects, Therapeutic Implications, and Circulating Biomarkers. Cancers 2023, 15, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chessa, C.; Bodet, C.; Jousselin, C.; Wehbe, M.; Lévêque, N.; Garcia, M. Antiviral and Immunomodulatory Properties of Antimicrobial Peptides Produced by Human Keratinocytes. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Yu, J.; Guo, Z.; Jiang, H.; Wang, C. Camptothecin-based prodrug nanomedicines for cancer therapy. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 17658–17697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.J.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Flowers, J.L.; Gamcsik, M.P.; Colvin, O.M.; Manikumar, G.; Wani, M.C.; Wall, M.E. Camptothecin analogues with enhanced antitumor activity at acidic pH. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2000, 46, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinić, J.; Podolski-Renić, A.; Jeremić, M.; Pešić, M. Potential of Natural-Based Anticancer Compounds for P-Glycoprotein Inhibition. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 4334–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinembiri, T.N.; Du Plessis, L.H.; Gerber, M.; Hamman, J.H.; Du Plessis, J. Review of Natural Compounds for Potential Skin Cancer Treatment. Molecules 2014, 19, 11679–11721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patridge, E.; Gareiss, P.; Kinch, M.S.; Hoyer, D. An analysis of FDA-approved drugs: natural products and their derivatives. Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagoa, R.; Silva, J.; Rodrigues, J.R.; Bishayee, A. Advances in phytochemical delivery systems for improved anticancer activity. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 38, 107382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cragg, G.M.; Newman, D.J. Natural products: A continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 3670–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laikova, K.V.; Oberemok, V.V.; Krasnodubets, A.M.; Gal’chinsky, N.V.; Useinov, R.Z.; Novikov, I.A.; Temirova, Z.Z.; Gorlov, M.V.; Shved, N.A.; Kumeiko, V.V.; et al. Advances in the Understanding of Skin Cancer: Ultraviolet Radiation, Mutations, and Antisense Oligonucleotides as Anticancer Drugs. Molecules 2019, 24, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, V.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles for topical drug delivery: Potential for skin cancer treatment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 153, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadros, T.; Izquierdo, P.; Esquena, J.; Solans, C. Formation and stability of nano-emulsions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 108–109, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanoemulsions for drug delivery Russell J. Wilson, Yang Li, Guangze Yang.

- Kabalnov, A. Thermodynamic and theoretical aspects of emulsions and their stability. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 1998, 3, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugovic-Mihic, L.; Cesic, D.; Vukovic, P.; Bilic, G.N.; Situm, M.; Spoljar, S. Melanoma Development: Current Knowledge on Melanoma Pathogenesis. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2019, 27, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Foroozandeh, P.; Aziz, A.A. Insight into Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking of Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugan, K.; Choonara, Y.E.; Kumar, P.; Bijukumar, D.; du Toit, L.C.; Pillay, V. Parameters and characteristics governing cellular internalization and trans-barrier trafficking of nanostructures. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 2191–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honary, S.; Zahir, F. Effect of Zeta Potential on the Properties of Nano-Drug Delivery Systems - A Review (Part 1). Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 12, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, Z.; Csóka, I.; Jazani, R.S.; Sipos, B.; Haspel, H.; Kozma, G.; Kónya, Z.; Dobó, D.G. Quality by Design-Driven Zeta Potential Optimisation Study of Liposomes with Charge Imparting Membrane Additives. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, L.P.; Yu, X.Y.; Zhang, R.Q. Effects of genistein and daidzein on the cell growth, cell cycle, and differentiation of human and murine melanoma cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002, 13, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greth, G.G.; Wilson, J.E. Use of the HLB system in selecting emulsifiers for emulsion polymerization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1961, 5, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, F.; Raimondi, M.; Di Domizio, A.; Moretti, R.M.; Marelli, M.M.; Limonta, P. Unraveling the molecular mechanisms and the potential chemopreventive/therapeutic properties of natural compounds in melanoma. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019, 59, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajadimajd, S.; Bahramsoltani, R.; Iranpanah, A.; Patra, J.K.; Das, G.; Gouda, S.; Rahimi, R.; Rezaeiamiri, E.; Cao, H.; Giampieri, F.; et al. Advances on Natural Polyphenols as Anticancer Agents for Skin Cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 151, 104584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral-Machado, L.; Xavier-Júnior, F.H.; Rutckeviski, R.; Morais, A.R.V.; Alencar, N.; Dantas, T.R.F.; Cruz, A.K.M.; Genre, J.; Da Silva-Junior, A.A.; Pedrosa, M.F.F.; et al. New Trends on Antineoplastic Therapy Research: Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana Shaw) Oil Nanostructured Systems. Molecules 2016, 21, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Monge-Fuentes, V.; Muehlmann, L.A.; Longo, J.P.; Silva, J.R.; Fascineli, M.L.; de Souza, P.; Faria, F.; Degterev, I.A.; Rodriguez, A.; Carneiro, F.P.; et al. Photodynamic therapy mediated by acai oil (Euterpe oleracea Martius) in nanoemulsion: A potential treatment for melanoma. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017, 166, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtado, C.d.M.; de Faria, F.S.E.D.V.; Azevedo, R.B.; Py-Daniel, K.; Camara, A.L.d.S.; da Silva, J.R.; Oliveira, E.d.H.; Rodriguez, A.F.R.; Degterev, I.A. Tectona grandis leaf extract, free and associated with nanoemulsions, as a possible photosensitizer of mouse melanoma B16 cell. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2017, 167, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-C.; Hung, C.-F.; Chen, B.-H. Preparation of coffee oil-algae oil-based nanoemulsions and the study of their inhibition effect on UVA-induced skin damage in mice and melanoma cell growth. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, ume 12, 6559–6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hou, L.; Liu, Q.; Shen, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, F.; Huang, L. Nano-delivery of fraxinellone remodels tumor microenvironment and facilitates therapeutic vaccination in desmoplastic melanoma. Theranostics 2018, 8, 3781–3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sudha, T.; A Salaheldin, T.; Darwish, N.H.; A Mousa, S. Antitumor/Anti-Angiogenesis Efficacy of Epigallocatechin Gallate Nanoformulated with Antioxidant in Melanoma. Nanomedicine 2022, 17, 1039–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasr, A.M.; Mortagi, Y.I.; Elwahab, N.H.A.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Shati, A.A.; Elbehairi, S.E.I.; Elshaarawy, R.F.M.; Kamal, I. Upgrading the Transdermal Biomedical Capabilities of Thyme Essential Oil Nanoemulsions Using Amphiphilic Oligochitosan Vehicles. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fang, J.-Y.; Hung, C.-F.; Hua, S.-C.; Hwang, T.-L. Acoustically active perfluorocarbon nanoemulsions as drug delivery carriers for camptothecin: Drug release and cytotoxicity against cancer cells. Ultrasonics 2009, 49, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, A.B.U.; Cetin, M.; Orgul, D.; Taghizadehghalehjoughi, A.; Hacımuftuoglu, A.; Hekimoglu, S. Formulation and in vitro evaluation of topical nanoemulsion and nanoemulsion-based gels containing daidzein. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 52, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacone, D.V.; Dartora, V.F.; de Matos, J.K.; Passos, J.S.; Miranda, D.A.; de Oliveira, E.A.; Silveira, E.R.; Costa-Lotufo, L.V.; Maria-Engler, S.S.; Lopes, L.B. Effect of nanoemulsion modification with chitosan and sodium alginate on the topical delivery and efficacy of the cytotoxic agent piplartine in 2D and 3D skin cancer models. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, H.L.; Calpena, A.C.; Garduño-Ramírez, M.L.; Ortiz, R.; Melguizo, C.; Prados, J.C.; Clares, B. Nanoemulsion Strategy for Ursolic and Oleanic Acids Isolates from Plumeria Obtusa Improves Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activity in Melanoma Cells. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda-Opazo, P.; Gotteland, M.; Oyarzun-Ampuero, F.A.; Garcia, L. Design, development and evaluation of nanoemulsion containing avocado peel extract with anticancer potential: A novel biological active ingredient to enrich food. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 111, 106370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, W.; Alencar, E.; Rocha, H.; Amaral-Machado, L.; Egito, E. Nanostructured systems increase the in vitro cytotoxic effect of bullfrog oil in human melanoma cells (A2058). Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 145, 112438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobo, G.G.; Piva, H.L.; Tedesco, A.C.; Primo, F.L. Novel quinizarin spray-dried nanoparticles for treating melanoma with photodynamic therapy. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budama-Kilinc, Y.; Gok, B.; Kecel-Gunduz, S.; Altuntas, E. Development of nanoformulation for hyperpigmentation disorders: Experimental evaluations, in vitro efficacy and in silico molecular docking studies. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, E.E.; Mueller, K.L.; Adams, D.J.; Anandasabapathy, N.; Aplin, A.E.; Bertolotto, C.; Bosenberg, M.; Ceol, C.J.; Burd, C.E.; Chi, P.; et al. Melanoma models for the next generation of therapies. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 610–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Jin, L.; Wang, Z. Comprehensive analysis of cancer hallmarks in cutaneous melanoma and identification of a novel unfolded protein response as a prognostic signature. Aging 2020, 12, 20684–20701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danaei, M.; Dehghankhold, M.; Ataei, S.; Hasanzadeh Davarani, F.; Javanmard, R.; Dokhani, A.; Khorasani, S.; Mozafari, M.R. Impact of Particle Size and Polydispersity Index on the Clinical Applications of Lipidic Nanocarrier Systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundra, V.; Li, W.; I Mahato, R. Nanoparticle-Mediated Drug Delivery for Treating Melanoma. Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 2613–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.; Rodrigues, P.; Pintado, M.; Tavaria, F. A systematic review of natural products for skin applications: Targeting inflammation, wound healing, and photo-aging. Phytomedicine 2023, 115, 154824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, A.; Gandhi, A.; Fimognari, C.; Atanasov, A.G.; Bishayee, A. Alkaloids for cancer prevention and therapy: Current progress and future perspectives. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 858, 172472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wróblewska-Łuczka, P.; Cabaj, J.; Bargieł, J.; Łuszczki, J.J. Anticancer effect of terpenes: focus on malignant melanoma. Pharmacol. Rep. 2023, 75, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).