1. Introduction

Melanoma, a highly aggressive form of skin malignancy, accounts for the 18th most common form of cancer worldwide [

1]. In early-stage disease, surgical excision is the primary therapeutic option. In turn, advanced melanoma is often untreatable, being associated with an extremely aggressive profile and low survival rates [

2,

3]. Chemotherapy is the most employed anticancer strategy, although some limitations are associated with chemotherapeutic agents, namely low specificity, toxic side effects and development of resistance [

2]. To tackle these challenges, metal coordination is receiving special emphasis since it offers new therapeutic opportunities that are inaccessible to conventional organic or biological compounds [

4].

Although metal-based compounds have successfully impacted medicine in different areas, in anticancer therapy only the platinum(II)-based drugs cisplatin, carboplatin and oxaliplatin are clinically approved and used in about 50% of all cancer chemotherapeutic regimens [

4,

5,

6]. Nevertheless, the emergence of platinum resistance in cancer is encouraging researchers to design novel and improved molecules [

2,

5,

7]. In melanoma, different metals are being investigated for the development of drug candidates, including copper [

8,

9,

10], gold (Au) [

11,

12,

13], silver [

11], zinc [

9], vanadium [

14], ruthenium [

15,

16], among others.

Gold-based complexes are highlighted due to their versatility in terms of electronic structures and variable redox states that grant them diversified biological activities and high therapeutic potential. Since the 2000s, the use of gold in medicinal chemistry has exponentially increased, and different families of Au(I) and Au(III) complexes have been investigated for their new mechanisms of action and targets, and decreased in vivo toxicity [

17,

18,

19]. Auranofin, an alkylphosphine Au(I) drug, was approved by the FDA in 1985 for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [

17]. Currently, there are ongoing clinical trials with auranofin to repurpose it for application in other diseases, including cancer [

17,

20]. In this context, gold-based compounds as anticancer agents have been widely investigated by various groups, including coordination and organometallic derivatives [

21,

22,

23]. Recently, it has been shown that organometallic Au(III) complexes may exert their anticancer activity by covalent targeting of proteins beyond the pure coordinative binding mode [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], and as such emerge as new chemical tools for bioorthogonal transformations in vitro and in vivo, as well as novel drug leads. Amongst the possible targets, the covalent inhibition of the cancer relevant selenoenzyme thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) [

29] and of membrane transporters of water and glycerol (aquaglyceroporins, AQPs) [

30] have been recently reported. In particular, several studies by our groups have demonstrated that gold-based complexes are potent and selective inhibitors of aquaporin-3 (AQP3), a membrane transporter of water and glycerol that is overexpressed in melanoma [

31,

32,

33,

34]. The ability of gold-based complexes to modulate AQP3 activity has turned them promising molecules against cancer and particularly for melanoma management [

35].

The main factors hindering the clinical translation of gold-based compounds are their limited solubility and chemical instability in physiological milieu. These challenges may be overcome through the incorporation in drug delivery systems, a strategy that retains the compounds’ pharmacological properties and facilitates its in vivo application [

18].

Liposomes, in particular, are the most successful and versatile lipid-based nanosystem, with numerous products approved for clinical use or undergoing clinical trials [

36,

37,

38]. These lipid-based nanosystems provide protection against premature degradation and prevent undesirable effects on healthy tissues. Moreover, the surface can be modified with polyethylene glycol (PEG) to increase blood circulating times and/or functionalized with specific ligands to promote active targeting of tissues/cells [

2,

8,

39,

40]. Clinical trials of metal-based nanomedicines are limited to platinum drugs loaded in liposomes (Lipoplatin, Aroplatin, SPI-077, and LiPlaCis) [

41] and polymeric micelles (NC-6004) [

42]. Despite the benefits of using delivery systems for metal-based compounds, research on nanomedicines of gold-based compounds are scarce [

18].

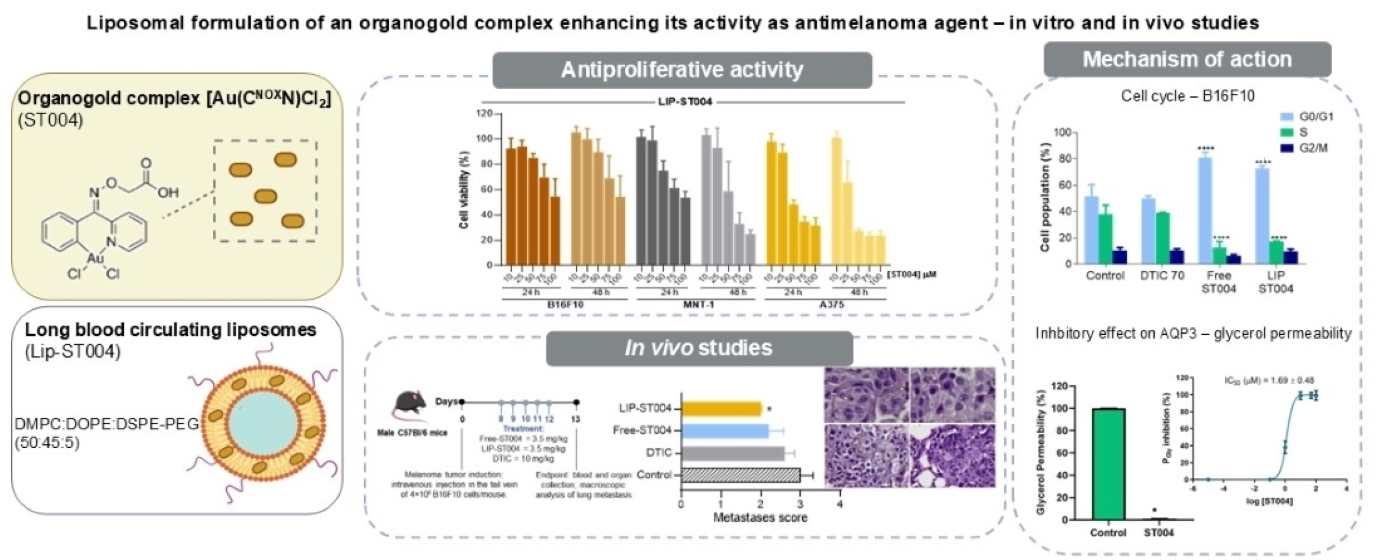

The aim of the present work was to assess the in vitro and in vivo antimelanoma potential of the Au(III) cyclometalated complex [[Au(C

NOxN)Cl

2] (C

NOxN = 2-(phenyl-(2-pyridinylmethylene)aminoxy acetic acid))] [

30], hereby designated as ST004 (

Figure 1), when in the free form and after association to long blood circulating liposomes (LIP-ST004). The compound has been previously show to react by a two-step mechanism involving reversible coordination of the cyclometalated gold(III) scaffold to thiolates of target cysteine residues, followed by reductive elimination and irreversible covalent cross-coupling reaction of the ligand to these nucleophiles. The inhibitory potency of ST004 on AQP3 was evaluated in human red blood cells (RBCs) that endogenously express AQP3. The upregulation of AQP3 has been reported in melanoma [

43]. Therefore, cytotoxicity and cell cycle assays of ST004 liposome formulations were performed in murine (B16F10) and human (A375 and MNT-1) melanoma cell lines. The gene expression of AQP3 have previously been assessed [

35,

44], with MNT-1 cells presenting higher transcript levels than A375 cells [

35]. The in vivo proof-of-concept was conducted in B16F10 murine models of subcutaneous and metastatic melanoma.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

The gold compound, ST004, was provided by Angela Casini, from the Technical University of Munich and synthesized according to a previously published procedure [

25]. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)–2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). The pure phospholipids, dimyristoyl phosphatidyl choline (DMPC; MW = 678), dioleoyl phosphatidyl ethanolamine (DOPE; MW = 744) and distearoyl phosphatidyl ethanolamine covalently linked to poly(ethylene glycol) 2000 (DSPE-PEG; MW = 2790) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Deionized water (Milli-Q system; Millipore, Tokyo, Japan) was used in all experiments. Nuclepore Track-Etched membranes were acquired from Whatman Ltd. (NY, USA). Culture media and antibiotics were obtained from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Propidium iodide (PI) was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Eugene, OR, USA) and RNase A was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Reagents for cell proliferation assays were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). All the remaining chemicals used were of analytical grade.

2.2. Cell Lines Culture Conditions

Human melanoma A375 (ATCC® CRL-1619™) and MNT-1 (ATCC® CRL-3450™) and murine melanoma B16F10 (ATCC® CRL-6475™) cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with high-glucose (4,500 mg/L), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 IU/mL of penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cells were maintained in 75 cm2 culture flasks at 37 °C in a humidified air incubator, at 5% CO2.

2.3. Red Blood Cells Sampling and Preparation

Venous blood samples were collected from anonymous human donors in citrate anticoagulant (2.7% citric acid, 4.5% trisodium citrate, and 2% glucose) to prevent coagulation. The blood was centrifuged at 750 × g for 10 min at room temperature (RT) to isolate red blood cells (RBCs). After washing three times with PBS, RBCs were diluted to a 0.5% suspension and kept on ice to be immediately used in the experiments.

2.4. Animals

Male C57BL/6 (8–10 weeks old) mice were purchased from Charles River (Barcelona, Spain). Animals were kept in ventilated cages under standard hygiene conditions, on a 12 h light / 12 h dark cycle, at 20–24 °C and 50–65% humidity. Mice had ad libitum intake of sterilized diet and acidified water. All in vivo experimental protocols were conducted according to the animal welfare organ of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Universidade de Lisboa, approved by the competent national authority Direção-Geral de Alimentação e Veterinária (DGAV) and in accordance with the EU Directive (2010/63/UE) and Portuguese laws (DR 113/2013, 2880/ 2015, 260/2016 and 1/2019) for the use and care of animals in research.

2.5. Preparation and Physicochemical Characterization of ST004 Liposomes

Liposomes were prepared by the dehydration-rehydration method. The selected phospholipids (30 μmol/mL) and ST004 (1000 μg/mL) were dissolved in chloroform, which was evaporated (Buchi R-200 rotary evaporator, Switzerland) to obtain a thin lipid film in a round-bottomed flask. The obtained lipid film was dispersed with deionized water and the so-formed suspension was frozen and lyophilized (freeze-dryer, CO, USA) overnight. The rehydration of the lyophilized powder was performed in HEPES buffer pH 7.4 (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl) in two steps. The so-formed liposomal suspension was then filtered under nitrogen pressure (10-500 lb/in2), through polycarbonate membranes of appropriate pore size until an average vesicle size of 100 nm was obtained, using an extruder device (Lipex Biomembranes Inc., Vancouver, Canada). The separation of non-incorporated ST004 was performed by gel filtration (Econo-Pac

® 10DG; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), followed by ultracentrifugation at 250,000 g, for 120 min, at 15 °C in a Beckman LM-80 ultracentrifuge (Beckman Instruments, Inc, CA, USA). The pellet was suspended in HEPES buffer pH 7.4. Liposomes were characterized in terms of incorporation parameters, mean size and surface charge. Loading capacity was defined as the final ST004 to lipid ratio (ST004/lipid)f and the incorporation efficiency (I.E.), in percentage, was determined using the equation (1):

ST004 was quantified spectrophotometrically at λ=283 nm after disruption of liposomes with ethanol. Linearity of calibration curves was ensured from 5 to 30 μM. Liposomes mean size and polydispersity index (PdI) were determined by dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer Nano Series, Nano-S Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) and zeta potential was measured by laser doppler electrophoresis (Zetasizer Nano Series, Nano-Z Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK).

2.6. Cell Viability Assay

For the in vitro assessment of ST004 formulations antiproliferative activity, human (A375 and MNT-1) and murine (B16F10) melanoma cell lines were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 5x10

4 cells/mL, 200 μL/well. After 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO

2, cells were incubated with ST004 in free and liposomal forms at concentrations ranging from 10-100 μM. Negative controls were cells in the presence of complete medium and the positive control corresponded to cells incubated with dacarbazine (DTIC) at concentrations ranging from 20-100 μM. Unloaded liposomes were also tested at the same lipid concentrations corresponding to ST004-loaded liposomes. Following 24 h and 48 h incubation, medium was removed, and wells were washed with PBS (200 μL/well). Then, 50 μL of the MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL of non-FBS medium) were added to each well and incubated at 37 °C, for 1-2 h. The resulting formazan crystals were solubilized with 100 μL of DMSO and absorbance was read at 570 nm. Cell viability analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism

®8.0.1 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA,

www.graphpad.com). To determine the EC

50 values, data were plotted and fit to a standard inhibition log concentration-response curve.

2.7. Cell Cycle Analysis

Cell cycle distribution assay was performed using a propidium iodide (PI) staining protocol, followed by flow cytometry analysis [

39]. Briefly, melanoma cell lines were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5×10

4 cells/mL, 3 mL/well. After 24 h, ST004 formulations were incubated at 50, 30 and 40 μM in B16F10, A375 and MNT-1, respectively. The positive control DTIC was tested at 70 μM in all cell lines [

39]. Negative control were cells in the presence of complete culture medium. Following 24 h of incubation, cells were detached and collected. After a centrifugation step at 800

g for 5 min, 4 °C, cells were suspended in cold PBS (500 μL) and an equal volume of 80% ice-cold ethanol (-20 °C) was added drop by drop, with gentle agitation. Samples were kept at 4 °C until analysis. For data acquisition, cells were centrifuged at 850

g for 5 min, at 4 °C. Cell pellets were suspended in 300 μL of cold PBS with PI and RNase A at a final concentration of 25 and 50 μg/mL, respectively, and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Acquisition of 40,000 events

per sample was performed on a full-spectrum Cytek

® Aurora cytometer (Cytek Biosciences, Inc.). Cell cycle histograms were automatically generated for each sample using the MultiCycle AV in FCS Express

TM 7 Software (DeNovo Software, Pasadena, CA, USA).

2.8. Inhibition of AQP3 Glycerol Permeability

To evaluate the inhibitory potency of ST004 on AQP3, we performed glycerol permeability assays using human RBCs by light scattering stopped-flow spectroscopy [

33] using a HI-TECH Scientific PQ/SF-53 stopped-flow apparatus interfaced with a microcomputer. After challenging cell suspensions with an equal volume of a glycerol hyperosmotic solution (200 mM glycerol in PBS pH 7.4) at 23 °C, creating an inwardly directed glycerol gradient, the time course of volume changes was measured by following the 90° scattered light intensity at 400 nm. After the first fast cell shrinkage due to water outflow, glycerol influx in response to its chemical gradient was followed by water influx with subsequent cell reswelling. For each experimental condition, 5–7 replicates were analyzed. Baselines were acquired using the respective incubation buffers as isotonic shock solutions.

Glycerol permeability (P

gly) was calculated by P

gly = k (V

0/A), where V

0/A is the initial cell volume to area ratio, and k is the single exponential time constant fitted to the light scattering signal of glycerol influx in erythrocytes [

33].

To assess the inhibitory potency of ST004 on AQP3 activity, cells were incubated with different concentrations of compound (0-100 µM) for 30 min at RT before permeability experiments. The inhibitor concentration that corresponds to 50% inhibition (IC50) was calculated by nonlinear regression of dose–response curves (GraphPad Prism software) using the following equation: y = 100/(1 + 10((LogIC50 − x) × HillSlope)), where HillSlope describes the steepness of the family of curves.

2.9. Therapeutic Evaluation of ST004 Formulations in Murine Models of Melanoma

Subcutaneous (s.c.) and metastatic melanoma tumors were induced with 1.3×10

5 and 4×10

6 B16F10 murine melanoma cancer cells, respectively. Cells were suspended in 100 μL PBS and injected subcutaneously in the right flank of mice for the s.c. model [

8,

39,

40] or intravenously in the tail vein for the metastatic melanoma [

39]. Animals were monitored for pain or distress and weighed daily. Animals were sacrificed when they met the ethical euthanasia criteria for overall health condition (loss of weight

> to 20% or showing signs of morbidity).

In the s.c. model, tumors became palpable on day 12 after induction and treatment protocol was initiated. Experimental groups were randomly organized (n=5) and mice received tested formulations by intravenous (i.v.) administration, one

per day, for five consecutive days: Negative control group received PBS (Control); Free-ST004 and LIP-ST004 groups received formulations at 3.5 mg/kg of body weight. Tumor dimensions were regularly assessed using a digital caliper. Two days after the last treatment, mice were sacrificed, and organs of interest were collected for further analysis. Tumor volumes were calculated according to equation (2),

where L and W represent the longest and shortest axis of the tumor, respectively. Relative tumor volumes (RTV) were determined for each animal, as the ratio between volumes at the indicated day and volumes at the beginning of treatment.

In the metastatic melanoma model, seven days post-induction, mice were randomly divided in groups of 6 and received the formulations under study by i.v. route, for five consecutive days: Negative control group received PBS (Control); positive control group received DTIC at 10 mg/kg of body weight; Free-ST004 and LIP-ST004 were injected at 3.5 mg/kg body weight. At the end of the experimental protocol, lungs were macroscopically analysed, and a score based on the number of metastases was established: 1 = 0-5 metastases; 2 = 6-20 metastases; 3 = 21-50 metastases; 4 = 51-100 metastases. For histopathological analysis, samples of lungs were preserved in 10% buffered formalin for bread-slice total routine processing and paraffin embedding. Three micrometer sections were stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for morphological analysis under optical microscopy. A board-certified veterinary pathologist that was blinded to the treatment group evaluated the slides for metastasis identification. Sample examination and image capture were performed on an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a DP21 camera (Olympus).

In both murine models, the safety of tested formulations was evaluated through tissue index and serum levels of aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT). Organs of interest (liver, spleen, kidneys, and lungs) were collected and weighed for tissue index determination according to equation (3).

For hepatic enzymes assay, serum was isolated from the blood and AST and ALT levels were analyzed using a commercially available Kit (Spinreact, Spain).

2.10. Statistics

Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test and unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction were performed using GraphPad Prism®8 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA). Statistical significance was considered at p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of ST004 Liposomes

Despite their promise as anticancer agents, gold-based compounds display poor bioavailability and limited chemical stability in physiological milieu, which hamper their successful clinical translation [

12,

18]. To overcome these challenges, lipid-based nanosystems, namely liposomes, are advantageous tools for the effective protection of associated and delivery of compounds. Liposomes as drug delivery systems were able to revolutionize the pharmaceutical and medical fields, being the first that have successfully reached the clinic [

38]. Metal-based complexes have been successfully loaded in liposomes by the team [

45,

46], particularly those presenting pH sensitive properties [

47], composed by DMPC:DOPE:CHEMS:DSPE-PEG. Regarding the gold-based complex ST004, preliminary studies demonstrated that this lipid composition was not adequate in terms of stability of the compound (data not shown); and so, the selected one did not include CHEMS. Aiming to maximize the loading of ST004 in liposomes two initial concentrations of ST004 were tested: 400 and 1000 μg/mL. The obtained results are depicted in

Table 1.

Overall, ST004 liposomes presented a low mean size (ca. 100 nm) and high homogeneity (PdI < 0.1), physicochemical properties that are achieved based on the method used for their preparation [

48]. The presence of the polymer DSPE-PEG conferred a surface charge close to neutrality, as confirmed by the zeta potential values of -4 and -5 mV. The loading capacity was positively correlated with the initial ST004 concentration. The higher initial ST004 concentration of 1000 μg/mL led to an increased loading capacity (15 ± 5 μg/μmol of lipid) compared to liposomes prepared with an initial concentration of 400 μg/ml (5 ± 1 μg/μmol of lipid). Therefore, liposomes prepared with the initial ST004 concentration of 1000 μg/mL were selected for further in vitro and in vivo testing.

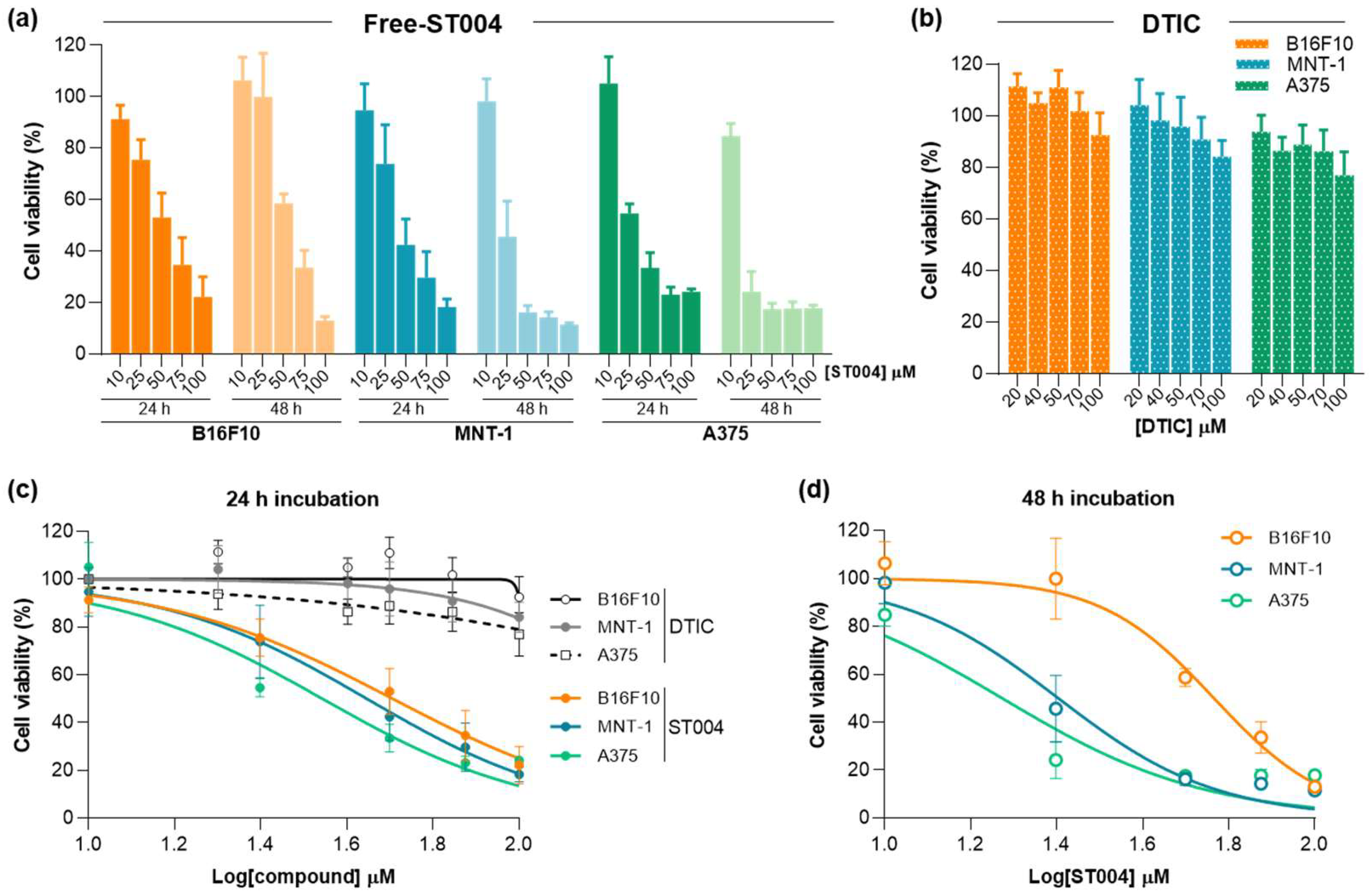

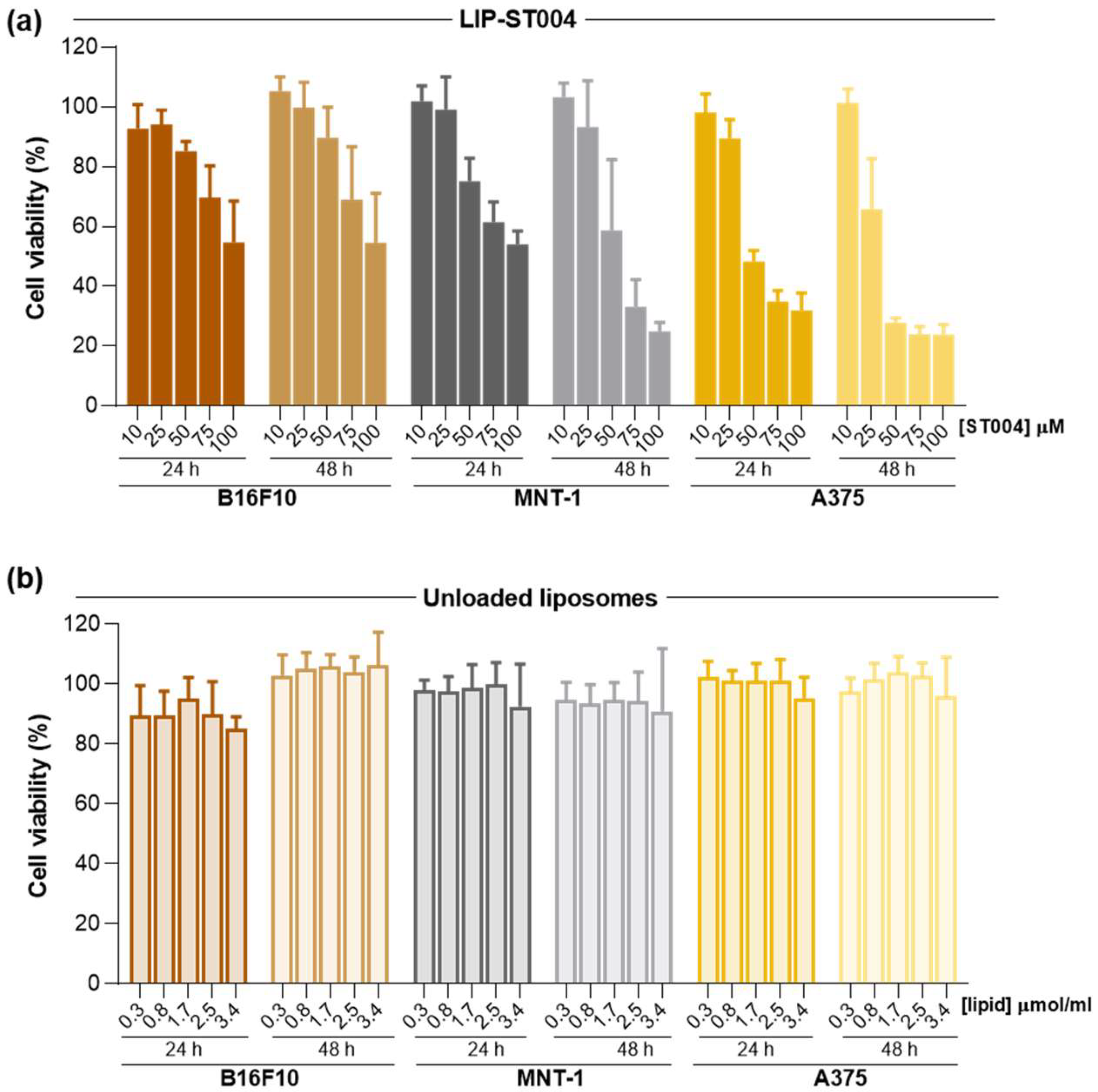

3.2. ST004 Formulations Display In Vitro Antiproliferative Activity Towards Melanoma Cell Lines

In the present work, the anticancer properties of this new gold-based complex were investigated in both free and liposomal forms. Additionally, DTIC was tested as benchmark drug to treat melanoma [

49]. Results of cell viability after incubation with Free-ST004 and DTIC are depicted in

Figure 2 and data from LIP-ST004 are depicted in

Figure 3, with the corresponding unloaded lipid composition. The EC

50 values of tested formulations are summarized in

Table 2.

ST004 in both free and liposomal forms demonstrated a concentration- and time-dependent antiproliferative activity in all melanoma cell lines, with an overall decrease of the EC

50 values at 48 h when compared to the 24 h incubation period (

Table 2). In all tested conditions, Free-ST004 displayed higher cytotoxicity compared to LIP-ST004. The lowest EC

50 was obtained for Free-ST004 in A375 cells at 48 h incubation (17 ± 1 μM) and the highest value was observed for LIP-ST004 in MNT-1 cell line after 24 h incubation (95 ± 3 μM). Recent work with four different Au(III) complexes revealed cell viabilities of around 70-100% and 80-90% for MNT-1 and A375, respectively, at the maximum tested concentration of 10 μM, after 24 h incubation [

35]. These results are in line with previous reports on different cyclometallated Au(III) [

29,

50], showing a concentration- and time-dependent effect of ST004 on melanoma cell lines.

The superior antiproliferative activity of Free-ST004 was expected since, in the free form, ST004 is readily available to act on intracellular and extracellular targets, opposed to compound in liposomal form, and may display different cell uptake mechanisms. This has also been observed in other research studies where liposomal nanoformulations displayed decreased cytotoxic activity, compared to free compound [

39,

51]. Of note, unloaded liposomes tested at the same lipid concentrations as the corresponding ST004-loaded liposomes did not affect cell viability (

Figure 3b). This confirmed that the observed antiproliferative activity of LIP-ST004 was solely due to the gold-based complex. In turn, the positive control DTIC revealed a weak antiproliferative activity, with an EC

50 > 100 μM for all tested cell lines, after 24 h incubation. This is in agreement with previous literature reports using melanoma cell lines [

40,

52,

53].

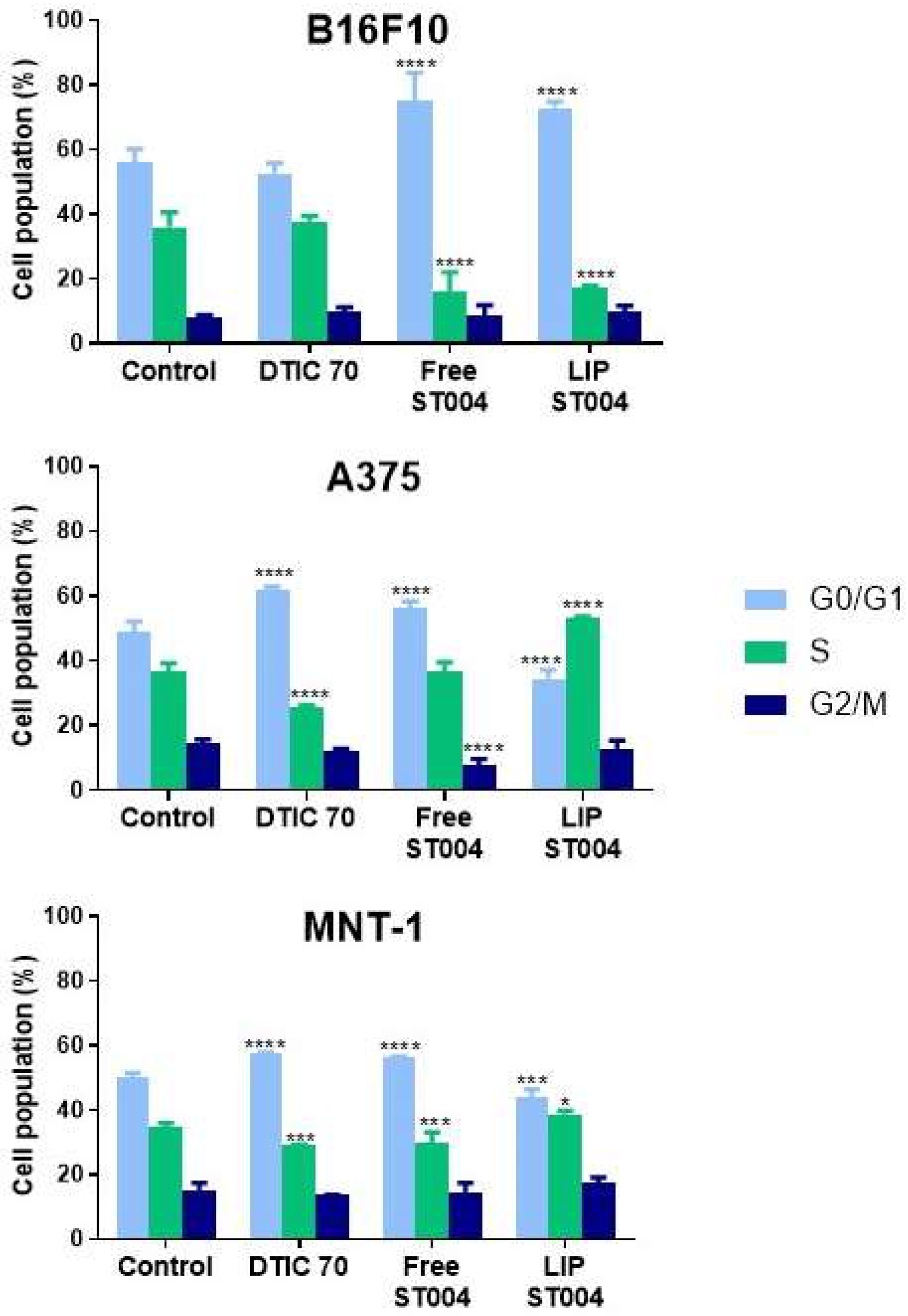

3.4. ST004 Formulations Exert Cell Cycle Alterations in Melanoma Cells

It is well established that cell cycle regulation is a key process in tumorigenesis and cancer response to therapy. A major goal of chemotherapy is to prevent tumor progression, which may be achieved by interfering with one or more phases of the cell cycle [

54]. Here, the effect of tested formulations on cell cycle progression was investigated. For that, melanoma cell lines were incubated with Free-ST004 at concentrations close to the 24 h EC

50 values: 50, 30 and 40 μM for B16F10, A375 and MNT-1 cells, respectively. LIP-ST004 was tested at the same concentrations as the free gold-based complex to allow the comparison of obtained results (

Figure 4). The concentration of the positive control, DTIC, was 70 μM for all cell lines [

39].

Incubation with tested compounds for 24 h led to alterations in the cell cycle of melanoma cells when compared to controls (

Figure 4 and supplementary information,

Figures S1 and S2). The positive control, DTIC, is an alkylating agent that affects cell independently of the phase [

55]. For human melanoma cell lines under study, DTIC, the positive control, at 70 μM caused an arrest at G0/G1 phase, with a concomitant decrease in S phase population. While similar effect has been previously reported in A375 cells [

40,

56], other researchers have noted different cell cycle responses for DTIC in these cell lines but using lower or much higher concentrations. For instance, DTIC incubation with A375 (ca. 30 μM) and MNT-1 (ca. 631 μM) resulted in no effects or increased S phase cell population, respectively [

57]. In another work using B16F10 cells, a concentration-dependent effect was observed for DTIC. At ca. 137 μM and 412 μM, this drug led to a G1 and a G2 phase arrest, respectively [

58].

Incubation with Free-ST004 resulted in a significant increase in G0/G1 population in tested cell lines, being more evident in B16F10. Previous work with the Au(III) complex Auphen, an inhibitor of aquaporin (AQP)3- and AQP10-facilitated glycerol permeation, has been reported [

30,

59]. Cell cycle analysis in AQP3-expressing PC12 cells revealed accumulation in S-G2/M phases after incubation with Auphen [

59]. Moreover, while different cyclometalated Au(III) complexes have induced G2/M arrest in colorectal cancer cells [

60], other types of Au(III) cyclometalated compounds induced a G1 halt in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cell line [

61].

In turn, LIP-ST004 activity was cell line-dependent. While in B16F10 cells a G0/G1 phase halt occurred, in A375 and MNT-1 a significant increase in the cell population at S phase was observed (

Figure 4 and supplementary information,

Figure S2). In literature, distinct effects of liposomal formulations depending on the cell line have been reported. In a study with liposomes loading SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan, HeLa and Caco-2 cells displayed a sub-G1 and S phase arrest, respectively [

62].

Furthermore, the association of compounds to liposomes has been described to modify their activity on cell cycle. For instance, while liposomal C6 ceramide did not affect cell cycle progression [

63], the free form was shown to block cells at G1 phase [

64]. In addition, in A549 cells, liposomal gefitinib induced a significantly more pronounced arrest in G0/G1 phase, compared to the free drug [

65]. Further, when associated to positively charged liposomes, the drug 6-mercaptopurine caused a sub-G0/G1 arrest in HepG2 cells. In turn, the free drug stopped cell cycle progression at G2/M phase [

66]. Another example is the liposomal form of hydrogenated anacardic acid that led to a cell cycle halt at sub-G1 and G2/M phases in cancer stem cells, whereas the free form only increased sub-G1 phase [

67].

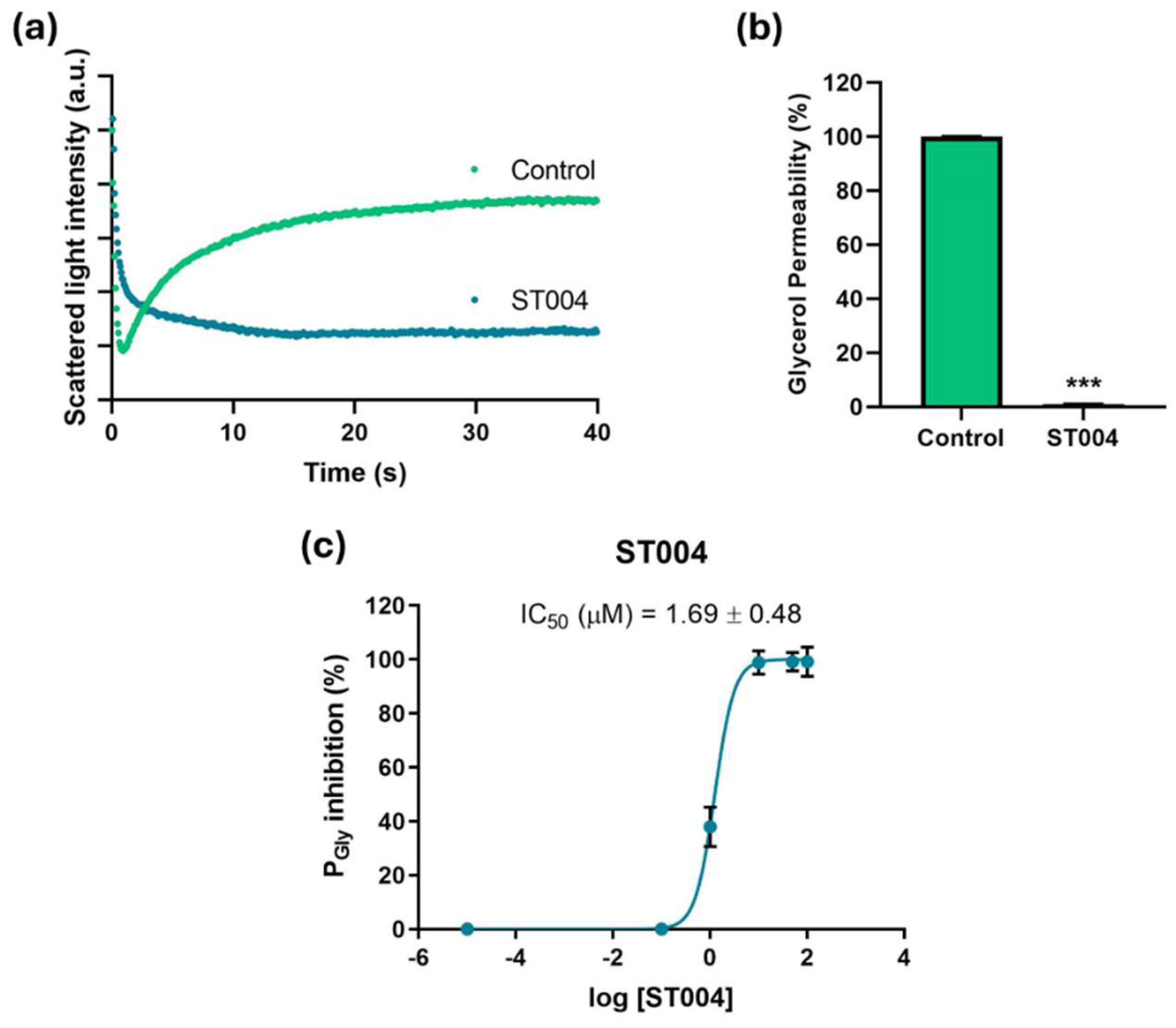

3.3. ST004 Inhibits AQP3 Activity

To gain preliminary insights into the mechanism of action of ST004, we investigated its potential inhibitory effect on AQP3 by measuring the glycerol permeability on a simple model consisting of human RBCs and using stopped-flow light scattering. Cells were challenged with a hyperosmotic glycerol solution inducing water efflux and cell shrinkage, followed by cell reswelling due to glycerol entrance via AQP3 (

Figure 5a). Glycerol permeability (Pgly) was calculated from the rate of cell reswelling in before and after cell treatment with the organogold compound ST004 (

Figure 5b).

Cells treated with ST004 exhibited an impaired glycerol permeability, revealing the strong inhibitory effect of ST004 on AQP3-mediated glycerol transport. Moreover, we assessed glycerol permeation of RBCs treated with different concentrations of ST004 (0 to 100 µM) revealing that ST004 is a potent inhibitor of AQP3 activity, with a low IC

50 (1.69 ± 0.48 µM) (

Figure 5c). Considering that AQP3 is overexpressed in melanoma, inhibiting AQP3 function may explain, at least in part, the potential of ST004 as an anticancer drug for melanoma.

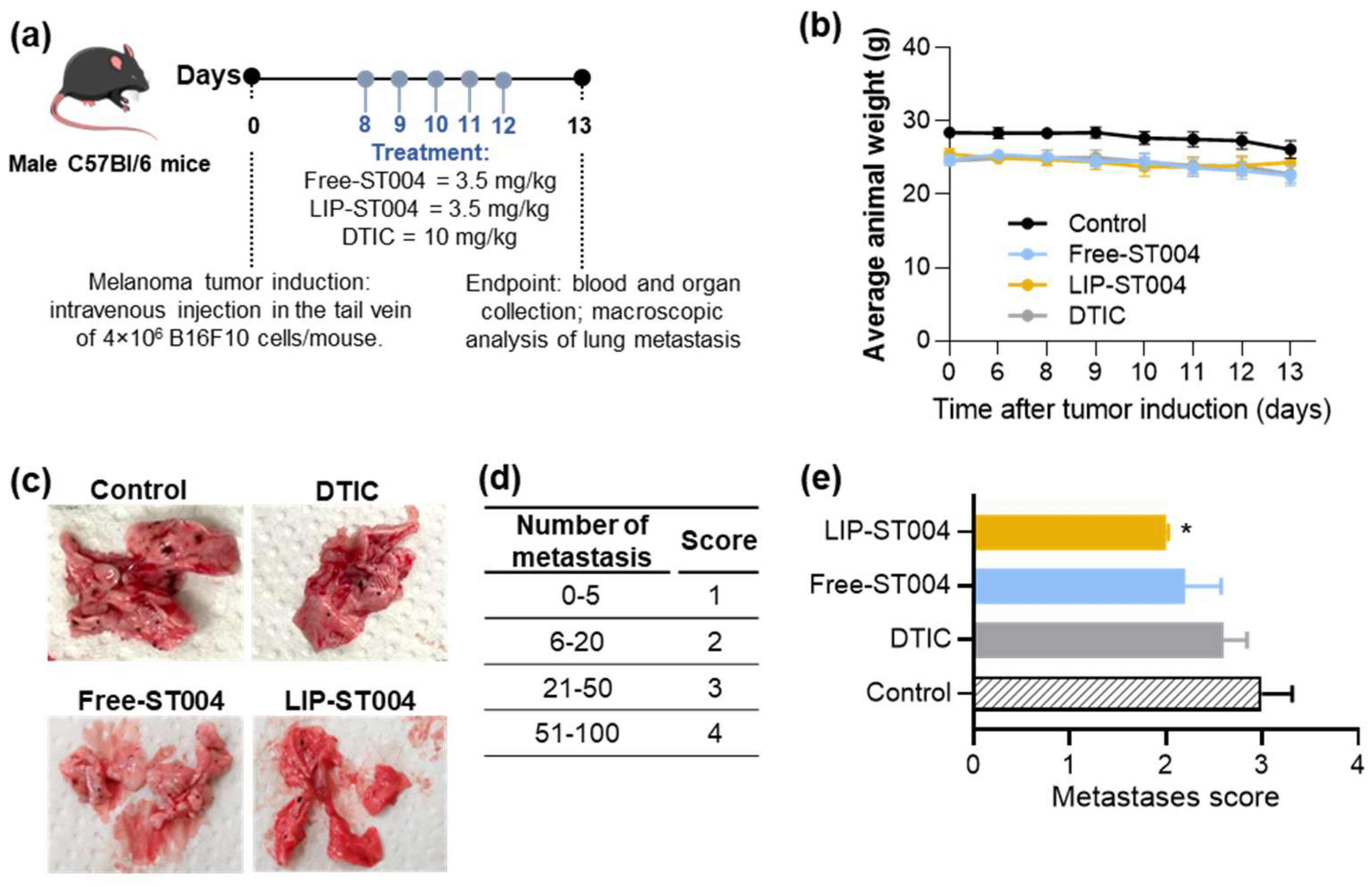

3.4. Therapeutic Evaluation of ST004 Formulations in Subcutaneous and Metastatic Murine Melanoma Models

After confirming the in vitro antimelanoma activity of the gold complex formulations, the next step was to evaluate the therapeutic potential in subcutaneous (supplementary information,

Figure S3) and metastatic (

Figure 6) murine melanoma models.

In a preliminary subcutaneous model, tumors were induced by a s.c. injection of 1.3×10

5 B16F10 cells/mouse, and treatment began 12 days after (

Figure S3a). Mice received i.v. injections of the formulations at a dose of 3.5 mg/kg of body weight, for five consecutive times, once per day. All animals maintained or slightly increased their body weight (

Figure S3b). As depicted in

Figure S3c, tumor volumes at the end of the experimental protocol were 1260 ± 274, 1103 ± 384 and 1160 ± 286 mm

3 for Control, Free-ST004 and LIP-ST004 groups, respectively. In previous work accomplished by the present team an increase on the therapeutic effect for other metal-based complexes, namely copper or iron, following their incorporation in liposomes was achieved in subcutaneous melanoma murine models [

8,

68]. However, the therapeutic dose used for ST004 was very lower (3.5 mg/kg of body weight) and treatment protocol was also shorter.

Based on the absence of therapeutic activity observed in the subcutaneous melanoma model, we have also tested ST004 formulations in a B16F10 metastatic model (

Figure 6a). Here, each mouse was inoculated i.v. with 4.0×10

6 B16F10 cells and treatments began eight days post-induction. A positive control, DTIC, was also included in the animal model (at a dose of 10 mg/kg of body weigh) while ST004 formulations were administered at a dose of 3.5 mg/kg, for five consecutive days, once per day. DTIC dose was selected in accordance with previous literature reports [

40,

69]. Animal body weight was documented (

Figure 6b) and, at the end of the experiment, lungs were macroscopically examined and a score was attributed according to the number of melanoma metastases (

Figure 6c, d, e). Tissue index of major organs and hepatic biomarkers were assessed as safety parameters (

Table S2).

The metastatic B16F10 cancer model most closely simulates the features of advanced melanoma disease in patients, namely high invasiveness, resistance to treatment, and increased mortality. Moreover, as mice are immunocompetent, the complexity of tumor microenvironment and the immune system are maintained, providing a better prediction and understanding of clinical responses [

3,

39,

70,

71].

Figure 6b shows a slight decrease (not statistically significant) of body weight by all groups, with LIP-ST004 treatment leading to a partial recovery after the third treatment. In the beginning of the treatment protocol all animals presented an average body weight of (25.2 ± 0.6). At day 13 post-tumor induction, Control, DTIC, Free-ST004 and LIP-ST004 groups displayed an average body weight of 26.1 ± 1.1 g, 22.7 ± 1.0 g, 22.5 ± 1.2 g and 24.4 ± 1.6 g, respectively. In the B16F10 metastatic model, the organs that are majorly affected by melanoma metastases are the lungs and brain. Here, the extension of metastases in the lungs was different among tested groups, as confirmed by visual examination (

Figure 6c) and respective metastases score (

Figure 6d, e). A significant (p<0.05) reduction on the number of metastases was attained in LIP-ST004 group, with the lowest score of 2.0, followed by Free-ST004 (2.2), DTIC (2.6) and Control (3.0). These findings confirm the efficacy of ST004 formulations, especially when in liposomal form, in limiting the process of melanoma metastization in the lungs.

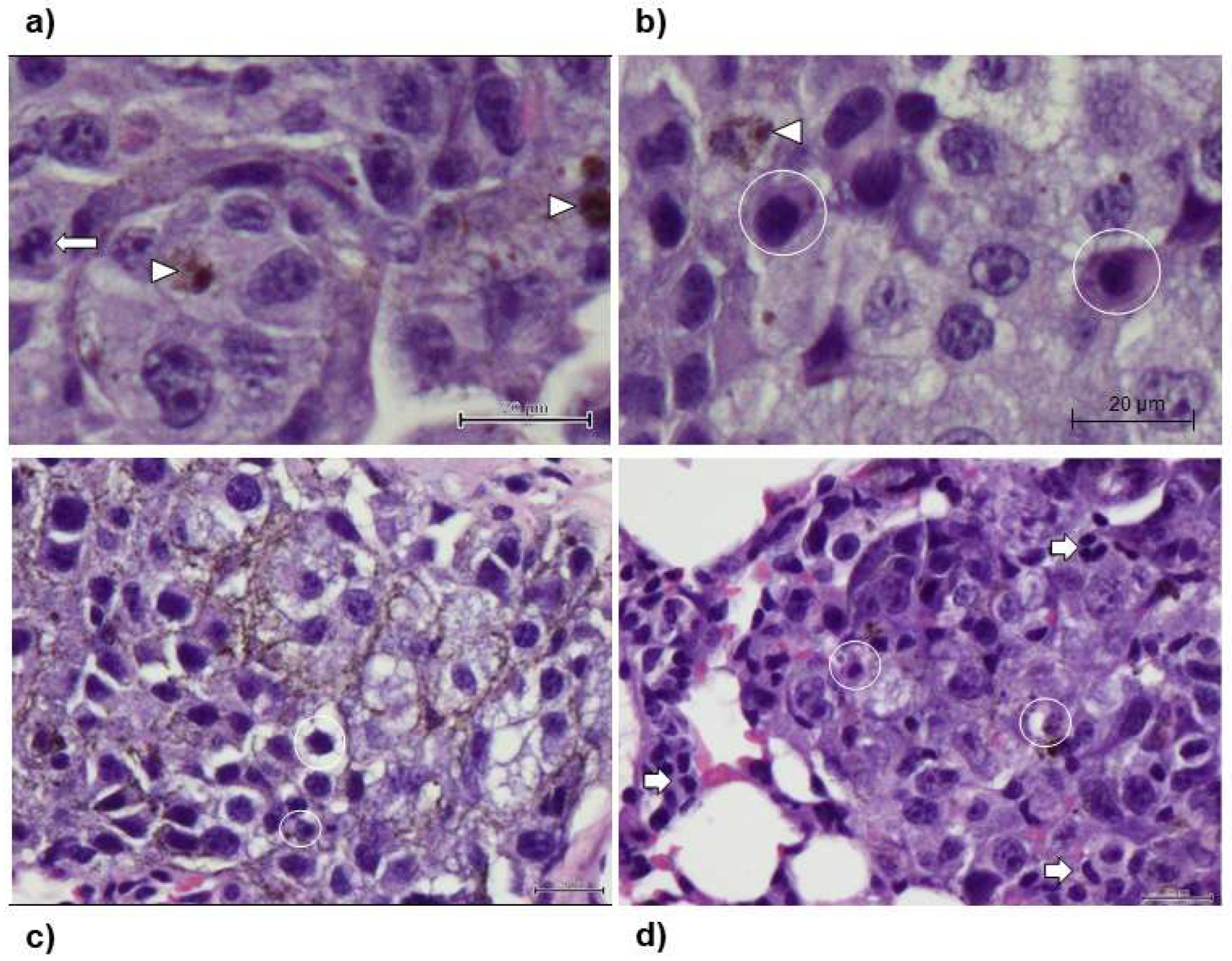

In all animals, histological analysis was also conducted (

Figure 7). This evaluation confirmed the presence of multiple foci of varying dimensions of interstitial infiltration by tight nests of round to polygonal neoplastic cells with finely vacuolated cytoplasm, occasionally containing sparse melanin granules; the cells had a large round to ovoid, pale, euchromatic nucleus, with one to four small nucleoli. Furthermore, the group of animals that received Lip-ST004 were associated to overall smaller metastatic nodules when compared to DTIC and Free-ST004 (

Figure 7d vs b) and c)).

The safety of tested formulations in both murine melanoma models was evaluated through tissue index and hepatic enzymes (

Table S2). When evaluating new compounds, a well-accepted and sensitive indicator of toxic side effects is organ weight variation [

72]. The assessment of tissue index considers the organ weight and the overall body weight of animals, and deviation from normal values may be indicative of organ atrophy and degeneration or hypertrophy, congestion and edema [

73,

74]. Besides tissue index, the serum levels of AST and ALT are relevant as safety biochemical markers for monitoring potential liver and/or skeletal/cardiac muscle damage [

74,

75]. These liver enzymes are among those applied in the clinic to identify liver injury. While under normal physiologic conditions, the levels of these enzymes may vary within a narrow range, the existence of a pathological condition or liver injury may result in more pronounced oscillations [

74,

75]. In this work, no major differences among tested groups were detected in terms of tissue index (

Tables S1 and S2). In turn, AST and ALT values observed for all groups under study were similar, including the naïve group, being within the reference intervals reported by the mice provider [

76].

5. Conclusions

In this work, the antimelanoma activity of a new gold-based complex, ST004, either in free form or after incorporation in long blood circulating liposomes, with a mean size below 100 nm, was assessed in vitro and in vivo.

Results from cytotoxicity assays demonstrated a time- and concentration-dependent antiproliferative activity of ST004 formulations, with LIP-ST004 displaying slightly decreased potency (EC50 values 31-95 μM), compared to Free-ST004 (17-58 μM). Unloaded liposomes did not affect cell viability in all tested lipid concentrations. Considering the cell cycle results, the gold-based complex disrupts normal cell proliferation. Free-ST004 halted cell cycle at G0/G1 phase in all murine and human cell lines under study. LIP-ST004 effect was cell-line dependent, leading to a G0/G1 halt in B16F10, and to an arrest in S phase in A375 and MNT-1 cells. The organogold compound also revealed a potent inhibitory effect on AQP3 activity, a member of the AQP family closely associated with cancer biological functions and aberrantly expressed in several human cancers. Further studies are necessary to fully explain the observed differences and to elucidate the mechanisms of action of this metallodrug.

The therapeutic evaluation of tested formulations was performed in subcutaneous and metastatic murine melanoma models. In the metastatic B16F10 murine model, a significant reduction on lung metastases was achieved in animals treated with LIP-ST004, compared to Free-ST004 and DTIC. Globally, this study emphasizes the antimelanoma potential of a new gold-based complex and the valuable benefits of using liposomes as a tool to improve its therapeutic index.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1. Gating strategy for cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry. Debris and doublets were excluded before assessing propidium iodide (PI) fluorescence. A cell cycle histogram was automatically generated for each sample using the MultiCycle AV in FCS Express 7 Software (DeNovo Software); Figure S2. Representative plots of gated B16F10, A375 and MNT-1 melanoma cells in the G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases of cell cycle in the absence (Control) or presence of DTIC at 70 μM (DTIC) or ST004 in free (Free-ST004) or liposomal (LIP-ST004) forms. A cell cycle histogram was automatically generated for each sample using the MultiCycle AV in FCS Express 7 Software (DeNovo Software); Figure S3. Therapeutic effect of tested ST004 formulations in a subcutaneous murine melanoma model. Tumor induction was performed by a s.c. injection of 1.3×105 B16F10 cells/mouse. Mice received i.v. injections of the formulations at a dose of 3.5 mg/kg of body weight, five consecutive times, once per day. Three experimental groups were established: Control (induced and non-treated mice); Free-ST004; LIP-ST004 (liposomal formulation of ST004, DMPC:DOPE:DSPE-PEG). (a) Experimental design, (b) Average animal weight, and (c) Tumor volume evolution. Tumor volumes were calculated according to the formula: V (mm3) = (L × W2)/2, where L and W represent the longest and shortest axis of the tumor, respectively. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4-5); Table S1. Tissue index and hepatic biomarkers of the subcutaneous murine melanoma model; Table S2. Tissue index and hepatic biomarkers of the metastatic murine melanoma model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.G. J.O.P.; methodology, J.O.P., M.C., J.K., A.G.-S. and M.M.G; formal analysis, J.O.P., M.C., J.K. and A.G.-S.; investigation, J.O.P., M.C., J.K., A.G.-S., R.M.N., S.R.T. and M.M.G.; resources, G.S., A.C. and M.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.O.P., M.C. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, G.S., A.C. and M.M.G.; supervision, A.C., G.S., M.M.G.; project administration, G.S. and M.M.G.; funding acquisition, G,S., M.M.G.

Funding

This work was supported by the Phospholipid Research Center (PRC), grant number MMG-2021-092/1-1 and Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), grant numbers UIDB/04138/2020, UIDP/04138/2020, PTDC/MED-QUI/31721/2017 and IDEA 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol for blood collection from healthy volunteers was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy of the University of Lisbon (Instituto Português de Sangue Protocol SN-22/05/2007). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Protocols that involved mice were carried out according to Directive 2010/63/EU and Portuguese laws (DR 113/2013, 2880/2015, 260/2016 and 1/2019) for the use and care of animals in research. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Lisboa (Animal Welfare Organ—ORBEA-FFUL) and licensed by the Portuguese competent authority (Direção Geral de Alimentação e Veterinária, license number: 003866, 10th of March 2023).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO World fact sheet: cancer.; 2021;

- Pinho, J.O.; Matias, M.; Gaspar, M.M. Emergent nanotechnological strategies for systemic chemotherapy against melanoma. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1455. [CrossRef]

- Matias, M.; Pinho, J.O.; Penetra, M.J.; Campos, G.; Reis, C.P.; Gaspar, M.M. The challenging melanoma landscape: From early drug discovery to clinical approval. Cells 2021, 10, 3088. [CrossRef]

- Anthony, E.J.; Bolitho, E.M.; Bridgewater, H.E.; Carter, O.W.L.; Donnelly, J.M.; Imberti, C.; Lant, E.C.; Lermyte, F.; Needham, R.J.; Palau, M.; et al. Metallodrugs are unique: opportunities and challenges of discovery and development. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 12888–12917. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. Cisplatin: The first metal based anticancer drug. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 88, 102925. [CrossRef]

- Casini, A.; Pöthig, A. Metals in Cancer Research: Beyond Platinum Metallodrugs. ACS Cent. Sci. 2024, 10, 242–250. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Gowda, B.H.J.; Ahmed, M.G.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Chen, Z.-S.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Kesharwani, P. Advancements in nanoparticle-based treatment approaches for skin cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 10. [CrossRef]

- Pinho, J.O.; Amaral, J.D.; Castro, R.E.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Casini, A.; Soveral, G.; Gaspar, M.M. Copper complex nanoformulations featuring highly promising therapeutic potential in murine melanoma models. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 835–850. [CrossRef]

- Côrte-Real, L.; Pósa, V.; Martins, M.; Colucas, R.; May, N. V; Fontrodona, X.; Romero, I.; Mendes, F.; Pinto Reis, C.; Gaspar, M.M.; et al. Cu(II) and Zn(II) Complexes of New 8-Hydroxyquinoline Schiff Bases: Investigating Their Structure, Solution Speciation, and Anticancer Potential. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 11466–11486. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Bulut, I.; Sergi, B.; Pósa, V.; Spengler, G.; Sciortino, G.; André, V.; Ferreira, L.P.; Biver, T.; Ugone, V.; et al. Promising anticancer agents based on 8-hydroxyquinoline hydrazone copper(II) complexes. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1106349. [CrossRef]

- Ciardulli, M.C.; Mariconda, A.; Sirignano, M.; Lamparelli, E.P.; Longo, R.; Scala, P.; D’Auria, R.; Santoro, A.; Guadagno, L.; Della Porta, G.; et al. Activity and Selectivity of Novel Chemical Metallic Complexes with Potential Anticancer Effects on Melanoma Cells. Molecules 2023, 28, 4851. [CrossRef]

- Ganga Reddy, V.; Srinivasa Reddy, T.; Privér, S.H.; Bai, Y.; Mishra, S.; Wlodkowic, D.; Mirzadeh, N.; Bhargava, S. Synthesis of Gold(I) Complexes Containing Cinnamide: In Vitro Evaluation of Anticancer Activity in 2D and 3D Spheroidal Models of Melanoma and In Vivo Angiogenesis. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 5988–5999. [CrossRef]

- Guadagno, L.; Raimondo, M.; Vertuccio, L.; Lamparelli, E.P.; Ciardulli, M.C.; Longo, P.; Mariconda, A.; Della Porta, G.; Longo, R. Electrospun Membranes Designed for Burst Release of New Gold-Complexes Inducing Apoptosis of Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7147. [CrossRef]

- Pisano, M.; Arru, C.; Serra, M.; Galleri, G.; Sanna, D.; Garribba, E.; Palmieri, G.; Rozzo, C. Antiproliferative activity of vanadium compounds: effects on the major malignant melanoma molecular pathways. Metallomics 2019, 11, 1687–1699. [CrossRef]

- Hussan, A.; Moyo, B.; Amenuvor, G.; Meyer, D.; Sitole, L. Investigating the antitumor effects of a novel ruthenium (II) complex on malignant melanoma cells: An NMR-based metabolomic approach. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 686, 149169. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, M.; Wu, X.; Guo, S.; Tian, Z.; Zhu, D.; Yang, J.; Fu, J.; Li, X.; Song, G.; et al. A Half-Sandwich Ruthenium(II) (N^N) Complex: Inducing Immunogenic Melanoma Cell Death in Vitro and in Vivo. ChemMedChem 2023, 18, e202300131. [CrossRef]

- Mertens, R.T.; Gukathasan, S.; Arojojoye, A.S.; Olelewe, C.; Awuah, S.G. Next generation gold drugs and probes: Chemistry and biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 6612–6667. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Alcántar, G.; Picchetti, P.; Casini, A. Gold Complexes in Anticancer Therapy: From New Design Principles to Particle-Based Delivery Systems. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202218000. [CrossRef]

- Salmain, M.; Bertrand, B. Emerging Anticancer Therapeutic Modalities Brought by Gold Complexes: Overview and Perspectives. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 26, e202300340. [CrossRef]

- Roder, C.; Thomson, M.J. Auranofin: Repurposing an Old Drug for a Golden New Age. Drugs R. D. 2015, 15, 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ma, X.; Chang, X.; Liang, Z.; Lv, L.; Shan, M.; Lu, Q.; Wen, Z.; Gust, R.; Liu, W. Recent development of gold(i) and gold(iii) complexes as therapeutic agents for cancer diseases. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 5518–5556. [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.-C.; Hu, D.; Wan, P.-K.; Lok, C.-N.; Che, C.-M. Anticancer Gold(III) Compounds With Porphyrin or N-heterocyclic Carbene Ligands. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 587207. [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, B.; Casini, A. A golden future in medicinal inorganic chemistry: The promise of anticancer gold organometallic compounds. Dalt. Trans. 2014, 43, 4209–4219. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.R.; Casini, A. Gold compounds for catalysis and metal-mediated transformations in biological systems. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2020, 55, 103–110. [CrossRef]

- Kung, K.K.-Y.; Ko, H.-M.; Cui, J.-F.; Chong, H.-C.; Leung, Y.-C.; Wong, M.-K. Cyclometalated gold(iii) complexes for chemoselective cysteine modification via ligand controlled C–S bond-forming reductive elimination. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11899–11902. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.R.; Bonsignore, R.; Sánchez Escudero, J.; Meier-Menches, S.M.; Brown, C.M.; Wolf, M.O.; Barone, G.; Luk, L.Y.P.; Casini, A. Exploring the Chemoselectivity towards Cysteine Arylation by Cyclometallated AuIII Compounds: New Mechanistic Insights. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 3071–3076. [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.N.; Bonsignore, R.; Thomas, S.R.; Bourissou, D.; Barone, G.; Casini, A. Cyclometalated AuIII Complexes for Cysteine Arylation in Zinc Finger Protein Domains: towards Controlled Reductive Elimination. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2019, 25, 7628–7634. [CrossRef]

- de Paiva, R.E.F.; Du, Z.; Nakahata, D.H.; Lima, F.A.; Corbi, P.P.; Farrell, N.P. Gold-Catalyzed C–S Aryl-Group Transfer in Zinc Finger Proteins. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 9305–9309.

- Skos, L.; Schmidt, C.; Thomas, S.R.; Park, M.; Geiger, V.; Wenisch, D.; Bonsignore, R.; Del Favero, G.; Mohr, T.; Bileck, A.; et al. Gold-templated covalent targeting of the CysSec-dyad of thioredoxin reductase 1 in cancer cells. Cell Reports Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 102072.

- Pimpão, C.; Wragg, D.; Bonsignore, R.; Aikman, B.; Pedersen, P.A.; Leoni, S.; Soveral, G.; Casini, A. Mechanisms of irreversible aquaporin-10 inhibition by organogold compounds studied by combined biophysical methods and atomistic simulations. Metallomics 2021, 13, mfab053. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, A.; Oliveira, B.L.; Correia, J.D.G.; Soveral, G.; Casini, A. Emerging protein targets for metal-based pharmaceutical agents: An update. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 2689–2704. [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.P.; Ciancetta, A.; DeAlmeida, A.; Marrone, A.; Re, N.; Soveral, G.; Casini, A. Aquaporin inhibition by gold(III) compounds: new insights. ChemMedChem. 2013, 8, 1086–1092. [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.P.; Marrone, A.; Ciancetta, A.; Galán Cobo, A.; Echevarría, M.; Moura, T.F.; Re, N.; Casini, A.; Soveral, G. Targeting aquaporin function: Potent inhibition of aquaglyceroporin-3 by a gold-based compound. PLoS One 2012, 7, e37435. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, A.; Mósca, A.F.; Wragg, D.; Wenzel, M.; Kavanagh, P.; Barone, G.; Leoni, S.; Soveral, G.; Casini, A. The mechanism of aquaporin inhibition by gold compounds elucidated by biophysical and computational methods. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 3830–3833. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, I. V; Pimpão, C.; Paccetti-Alves, I.; Thomas, S.R.; Barateiro, A.; Casini, A.; Soveral, G. Blockage of aquaporin-3 peroxiporin activity by organogold compounds affects melanoma cell adhesion, proliferation and migration. J. Physiol. 2024, 602, 3111–3129.

- Perche, F.; Torchilin, V.P. Recent trends in multifunctional liposomal nanocarriers for enhanced tumor targeting. J. Drug Deliv. 2013, 2013, 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.O.; Pinho, J.O.; Lopes, J.M.; Almeida, A.J.; Gaspar, M.M.; Reis, C. Current trends in cancer nanotheranostics: Metallic, polymeric, and lipid-based systems. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 22. [CrossRef]

- Crommelin, D.J.A.; van Hoogevest, P.; Storm, G. The role of liposomes in clinical nanomedicine development. What now? Now what? J. Control. Release 2020, 318, 256–263. [CrossRef]

- Pinho, J.O.; Matias, M.; Marques, V.; Eleutério, C.; Fernandes, C.; Gano, L.; Amaral, J.D.; Mendes, E.; Perry, M.J.; Moreira, J.N.; et al. Preclinical validation of a new hybrid molecule loaded in liposomes for melanoma management. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 157, 114021. [CrossRef]

- Pinho, J.O.; Matias, M.; Godinho-Santos, A.; Amaral, J.D.; Mendes, E.; Perry, M.J.; Francisco, A.P.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Gaspar, M.M. A step forward on the in vitro and in vivo assessment of a novel nanomedicine against melanoma. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 640, 123011. [CrossRef]

- Bulbake, U.; Doppalapudi, S.; Kommineni, N.; Khan, W. Liposomal formulations in clinical use: An updated review. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 12. [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Wilson, R.H.; Calvert, H.; Boddy, A. V; Griffin, M.; Sludden, J.; Tilby, M.J.; Eatock, M.; Pearson, D.G.; Ottley, C.J.; et al. A Phase I clinical study of cisplatin-incorporated polymeric micelles (NC-6004) in patients with solid tumours. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 593–598. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, I. V; Silva, A.G.; Pimpão, C.; Soveral, G. Skin aquaporins as druggable targets: Promoting health by addressing the disease. Biochimie 2021, 188, 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Pimpão, C.; da Silva, I. V.; Mósca, A.F.; Pinho, J.O.; Gaspar, M.M.; Gumerova, N.I.; Rompel, A.; Aureliano, M.; Soveral, G. The Aquaporin-3-Inhibiting Potential of Polyoxotungstates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2467. [CrossRef]

- Nave, M.; Castro, R.E.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Casini, A.; Soveral, G.; Gaspar, M.M. Nanoformulations of a potent copper-based aquaporin inhibitor with cytotoxic effect against cancer cells. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2016, 11, 1817–1830. [CrossRef]

- Pinho, J.O.; Amaral, J.D.; Castro, R.E.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Casini, A.; Soveral, G.; Gaspar, M.M. Copper complex nanoformulations featuring highly promising therapeutic potential in murine melanoma models. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2019, 14, 835–850. [CrossRef]

- Pinho, J.O.; da Silva, I.V.; Amaral, J.D.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Casini, A.; Soveral, G.; Gaspar, M.M. Therapeutic potential of a copper complex loaded in pH-sensitive long circulating liposomes for colon cancer management. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 599, 120463.

- Gaspar, M.M.; Calado, S.; Pereira, J.; Ferronha, H.; Correia, I.; Castro, H.; Tomás, A.M.; Cruz, M.E.M. Targeted delivery of paromomycin in murine infectious diseases through association to nano lipid systems. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol. Med. 2015, 11, 1851–1860. [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.A.; Agarwala, S.S. Cutaneous melanoma: available therapy for metastatic disease. Dermatol. Ther. 2006, 19, 19–25. [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, B.; Spreckelmeyer, S.; Bodio, E.; Cocco, F.; Picquet, M.; Richard, P.; Le Gendre, P.; Orvig, C.; Cinellu, M.A.; Casini, A. Exploring the potential of gold(III) cyclometallated compounds as cytotoxic agents: variations on the C^N theme. Dalt. Trans. 2015, 44, 11911–8. [CrossRef]

- Saddiqi, M.E.; Abdul Kadir, A.; Abdullah, F.F.J.; Abu Bakar Zakaria, M.Z.; Banke, I.S. Preparation, characterization and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of free and liposome-encapsulated tylosin. OpenNano 2022, 8, 100108. [CrossRef]

- Da-Costa-Rocha, I.; Prieto, J.M. In Vitro Effects of Selective COX and LOX Inhibitors and Their Combinations with Antineoplastic Drugs in the Mouse Melanoma Cell Line B16F10. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6498. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Lee, D.G.; Joo, Y.H.; Chung, N. Synergistic inhibitory effects of the oxyresveratrol and dacarbazine combination against melanoma cells. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 22, 667. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Hu, H. The Influence of Cell Cycle Regulation on Chemotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6923. [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, F.; Turriziani, M.; Tortorelli, G.; Avvisati, G.; Torino, F.; Devecchis, L. Triazene compounds: Mechanism of action and related DNA repair systems. Pharmacol. Res. 2007, 56, 275–287. [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, A.; Wierzbicka, J.; Rybarczyk, A.; Tuckey C., R.; Slominski T., A.; Żmijewski A., M. Vitamin D and its low calcemic analogs modulate the anticancer properties of cisplatin and dacarbazine in the human melanoma A375 cell line. Int J Oncol 2019, 54, 1481–1495.

- Salvador, D.; Bastos, V.; Oliveira, H. Combined Therapy with Dacarbazine and Hyperthermia Induces Cytotoxicity in A375 and MNT-1 Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3586. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; He, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, K.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Guo, Z.; Zha, Z.-G.; Zhou, C. Effect of dacarbazine on CD44 in live melanoma cells as measured by atomic force microscopy-based nanoscopy. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 8867–8886. [CrossRef]

- Serna, A.; Galán-Cobo, A.; Rodrigues, C.; Sánchez-Gomar, I.; Toledo-Aral, J.J.; Moura, T.F.; Casini, A.; Soveral, G.; Echevarría, M. Functional inhibition of aquaporin-3 with a gold-based compound induces blockage of cell proliferation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2014, 229, 1787–1801. [CrossRef]

- Abás, E.; Bellés, A.; Rodríguez-Diéguez, A.; Laguna, M.; Grasa, L. Selective cytotoxicity of cyclometalated gold(III) complexes on Caco-2 cells is mediated by G2/M cell cycle arrest. Metallomics 2021, 13, 1–16.

- Mertens, R.T.; Parkin, S.; Awuah, S.G. Cancer cell-selective modulation of mitochondrial respiration and metabolism by potent organogold(III) dithiocarbamates. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 10465–10482. [CrossRef]

- Casadó, A.; Sagristá, M.L.; Mora Giménez, M. A novel microfluidic liposomal formulation for the delivery of the SN-38 camptothecin: characterization and in vitro assessment of its cytotoxic effect on two tumor cell lines. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 5301–5320. [CrossRef]

- Sriraman, S.K.; Pan, J.; Sarisozen, C.; Luther, E.; Torchilin, V. Enhanced Cytotoxicity of Folic Acid-Targeted Liposomes Co-Loaded with C6 Ceramide and Doxorubicin: In Vitro Evaluation on HeLa, A2780-ADR, and H69-AR Cells. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 428–437.

- Jayadev, S.; Liu, B.; Bielawska, A.E.; Lee, J.Y.; Nazaire, F.; Pushkareva, M.Y.; Obeid, L.M.; Hannun, Y.A. Role for Ceramide in Cell Cycle Arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 2047–2052. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, H.; Xu, S.; Xu, L.; Chen, E. Gefitinib encapsulation based on nano-liposomes for enhancing the curative effect of lung cancer. Cell Cycle 2020, 19, 3581–3594. [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Asseri, A.H.; Ali, E.M.M.; El-Gowily, A.H.; Khan, M.I.; Hosawi, S.; Alsolami, R.; Ahmed, T.A. Preparation of 6-Mercaptopurine Loaded Liposomal Formulation for Enhanced Cytotoxic Response in Cancer Cells. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4029. [CrossRef]

- Vien, L.T.; Nga, N.T.; Hue, P.T.K.; Kha, T.H.B.; Hoang, N.H.; Hue, P.T.; Thien, P.N.; Huang, C.-Y.F.; Van Kiem, P.; Thao, D.T. A New Liposomal Formulation of Hydrogenated Anacardic Acid to Improve Activities Against Cancer Stem Cells. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2022, 17, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Matos, C.P.; Albino, M.; Lopes, J.; Viana, A.S.; Côrte-Real, L.; Mendes, F.; Pessoa, J.C.; Tomaz, A.I.; Reis, C.P.; Gaspar, M.M.; et al. New iron(III) anti-cancer aminobisphenolate/phenanthroline complexes: Enhancing their therapeutic potential using nanoliposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 623, 121925. [CrossRef]

- Sadhu, S.S.; Wang, S.; Averineni, R.K.; Seefeldt, T.; Yang, Y.; Guan, X. In-vitro and in-vivo inhibition of melanoma growth and metastasis by the drug combination of celecoxib and dacarbazine. Melanoma Res. 2016, 26, 572–579. [CrossRef]

- Couto, G.K.; Segatto, N.V.; Oliveira, T.L.; Seixas, F.K.; Schachtschneider, K.M.; Collares, T. The melding of drug screening platforms for melanoma. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 512. [CrossRef]

- Timmons, J.J.; Cohessy, S.; Wong, E.T. Injection of Syngeneic Murine Melanoma Cells to Determine Their Metastatic Potential in the Lungs. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, 54039.

- Lazic, S.E.; Semenova, E.; Williams, D.P. Determining organ weight toxicity with Bayesian causal models: Improving on the analysis of relative organ weights. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6625. [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.-Z.; Wang, Q.; Tong, W.-Z.; Xiong, J.; Wei, Q.; Zhou, W.-H.; Yin, Z.-Q.; Yin, X.-Y.; Wang, L.-Y.; Chen, Y.-Q.; et al. Extraction and antioxidant activity of flavonoids of Morus nigra. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 22328–22336.

- Ibegbulem, C.; Chikezie, P. Levels of Acute Blood Indices Disarrangement and Organ Weights of Wistar Rats Fed with Flavour Enhancer- and Contraceptive-Containing Diets. J. Investig. Biochem. 2016, 5, 1. [CrossRef]

- Aulbach, A.D.; Amuzie, C.J. Biomarkers in Nonclinical Drug Development. In A Comprehensive Guide to Toxicology in Nonclinical Drug Development; Faqi, A.S.B.T.-A.C.G. to T. in N.D.D. (Second E., Ed.; Elsevier: Boston, 2017; pp. 447–471 ISBN 978-0-12-803620-4.

- Charles River Laboratories C57BL/6 Mice Available online: https://www.criver.com/sites/default/files/resources/C57BL6MouseClinicalPathologyData.pdf (accessed on Nov 5, 2022).

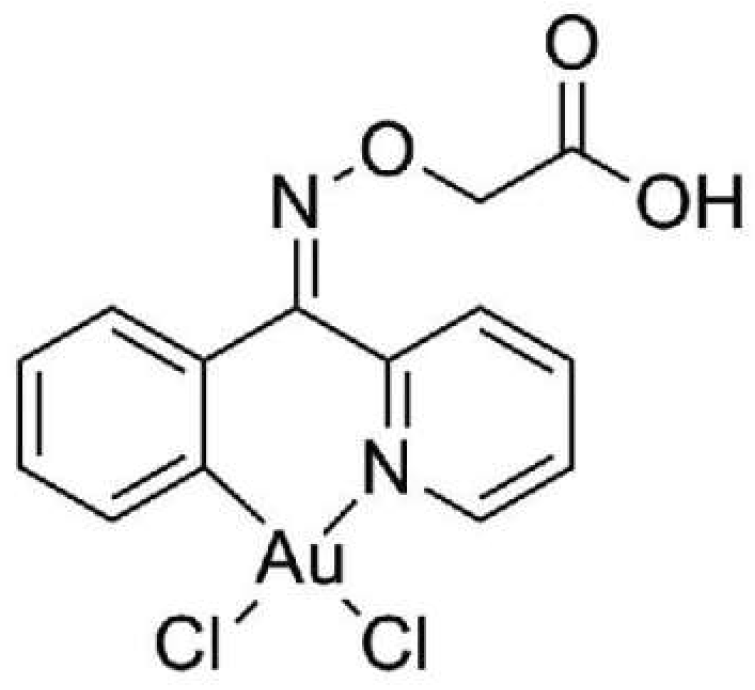

Figure 1.

Structure of the tested organogold compound, [[Au(CNOxN)Cl2] (CNOxN = 2-(phenyl-(2-pyridinylmethylene)aminoxy acetic acid))], ST004, (MW - .523.12).

Figure 1.

Structure of the tested organogold compound, [[Au(CNOxN)Cl2] (CNOxN = 2-(phenyl-(2-pyridinylmethylene)aminoxy acetic acid))], ST004, (MW - .523.12).

Figure 2.

Antiproliferative activity of Free-ST004 and DTIC against melanoma cell lines B16F10, MNT-1 and A375. (a) Cell viability after 24 and 48 h incubation with ST004 in the free form at concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 μM. (b) Cell viability after 24 h incubation with DTIC at concentrations ranging from 20 to 100 μM. (c, d) Concentration-response curves of melanoma cell lines after 24 h (c) and 48 h (d) incubation with tested formulations. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n=2-3). DTIC: dacarbazine.

Figure 2.

Antiproliferative activity of Free-ST004 and DTIC against melanoma cell lines B16F10, MNT-1 and A375. (a) Cell viability after 24 and 48 h incubation with ST004 in the free form at concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 μM. (b) Cell viability after 24 h incubation with DTIC at concentrations ranging from 20 to 100 μM. (c, d) Concentration-response curves of melanoma cell lines after 24 h (c) and 48 h (d) incubation with tested formulations. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n=2-3). DTIC: dacarbazine.

Figure 3.

Antiproliferative activity of LIP-ST004 against melanoma cell lines B16F10, MNT-1 and A375. Data corresponds to cell viability after 24 and 48 h incubation with (a) LIP-ST004 at concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 μM and (b) Unloaded liposomes were tested at the same lipid concentrations as ST004-loaded liposomes. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n=2). LIP-ST004: DMPC:DOPE:DSPE-PEG (50:45:5).

Figure 3.

Antiproliferative activity of LIP-ST004 against melanoma cell lines B16F10, MNT-1 and A375. Data corresponds to cell viability after 24 and 48 h incubation with (a) LIP-ST004 at concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 μM and (b) Unloaded liposomes were tested at the same lipid concentrations as ST004-loaded liposomes. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n=2). LIP-ST004: DMPC:DOPE:DSPE-PEG (50:45:5).

Figure 4.

Quantitative analysis of gated B16F10, A375 and MNT-1 melanoma cell lines cells in the G0/G1, S, and G2/M cell cycle phases in the absence (Control) or presence of DTIC at 70 μM (DTIC 70) or ST004 in free (Free-ST004) and liposomal (LIP-ST004) forms at 50, 30 and 40 μM for B16F10, A375 and MNT-1, respectively. LIP-ST004: DMPC:DOPE:DSPE-PEG(50:45:5). Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001 vs Control.

Figure 4.

Quantitative analysis of gated B16F10, A375 and MNT-1 melanoma cell lines cells in the G0/G1, S, and G2/M cell cycle phases in the absence (Control) or presence of DTIC at 70 μM (DTIC 70) or ST004 in free (Free-ST004) and liposomal (LIP-ST004) forms at 50, 30 and 40 μM for B16F10, A375 and MNT-1, respectively. LIP-ST004: DMPC:DOPE:DSPE-PEG(50:45:5). Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n=3). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001 vs Control.

Figure 5.

Effect of ST004 on AQP3 activity in human red blood cells (RBCs). (a) Representative stopped-flow signal showing changes in scattering light intensity when cells are confronted with a hyperosmotic glycerol solution. After a first shrinkage due to water efflux, cells reswell due to glycerol entrance via aquaporin 3 (AQP3) (control). Cell treatment with ST004 impairs glycerol influx. (b) Glycerol permeability of RBCs incubated with ST004 (100 µM for 30 min). (c) Dose–response curves of AQP3 glycerol permeability inhibition by ST004 (0-100 µM). Data are shown as means ± SD of three independent experiments. *** p < 0.001. * non-treated vs. treated cells.

Figure 5.

Effect of ST004 on AQP3 activity in human red blood cells (RBCs). (a) Representative stopped-flow signal showing changes in scattering light intensity when cells are confronted with a hyperosmotic glycerol solution. After a first shrinkage due to water efflux, cells reswell due to glycerol entrance via aquaporin 3 (AQP3) (control). Cell treatment with ST004 impairs glycerol influx. (b) Glycerol permeability of RBCs incubated with ST004 (100 µM for 30 min). (c) Dose–response curves of AQP3 glycerol permeability inhibition by ST004 (0-100 µM). Data are shown as means ± SD of three independent experiments. *** p < 0.001. * non-treated vs. treated cells.

Figure 6.

Therapeutic effect of tested formulations in a metastatic murine melanoma model. Tumor induction was performed by an i.v. inoculation of 4.0×106 B16F10 cells/mouse. Mice received i.v. injections of ST004 and DTIC formulations at a dose of 3.5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively. Treatments were given five consecutive times, once per day. Four experimental groups were established: Control (induced and non-treated mice); Free-ST004; LIP-ST004 (DMPC:DOPE:DSPE-PEG); DTIC (positive control). (a) Experimental design, (b) Average animal body weight, (c) Representative images of lungs with melanoma metastases (black dots), (d) Metastasis score established from 1 to 4 according to the number of metastases in the lungs, (e) Average metastasis score for each experimental group. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. *p<0.05 vs Control. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4-5).

Figure 6.

Therapeutic effect of tested formulations in a metastatic murine melanoma model. Tumor induction was performed by an i.v. inoculation of 4.0×106 B16F10 cells/mouse. Mice received i.v. injections of ST004 and DTIC formulations at a dose of 3.5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively. Treatments were given five consecutive times, once per day. Four experimental groups were established: Control (induced and non-treated mice); Free-ST004; LIP-ST004 (DMPC:DOPE:DSPE-PEG); DTIC (positive control). (a) Experimental design, (b) Average animal body weight, (c) Representative images of lungs with melanoma metastases (black dots), (d) Metastasis score established from 1 to 4 according to the number of metastases in the lungs, (e) Average metastasis score for each experimental group. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. *p<0.05 vs Control. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4-5).

Figure 7.

Representative histological images of lung samples stained with H&E. a) Control. Neoplastic cells vary from a round to a polygonal profile, with barely evident borders, occasionally containing small amounts of melanic pigment (arrowheads). Long arrows denote a mitotic figure; b) DTIC. Neoplastic cells maintain typical morphology and occasional melanic pigment (arrowheads). Apoptotic cells are interspersed with viable cells (circles); c) Free-ST004. Apoptotic cells are interspersed with viable cells (circles); d) Lip-ST004. Neoplastic cells are intermingled with small infiltrating lymphocytes (short arrows) and apoptotic neoplastic cells (circles).

Figure 7.

Representative histological images of lung samples stained with H&E. a) Control. Neoplastic cells vary from a round to a polygonal profile, with barely evident borders, occasionally containing small amounts of melanic pigment (arrowheads). Long arrows denote a mitotic figure; b) DTIC. Neoplastic cells maintain typical morphology and occasional melanic pigment (arrowheads). Apoptotic cells are interspersed with viable cells (circles); c) Free-ST004. Apoptotic cells are interspersed with viable cells (circles); d) Lip-ST004. Neoplastic cells are intermingled with small infiltrating lymphocytes (short arrows) and apoptotic neoplastic cells (circles).

Table 1.

Physicochemical characterization of LIP-ST004.

Table 1.

Physicochemical characterization of LIP-ST004.

Lipid composition

(molar ratio) |

[ST004]i

(μg/mL) |

ST004/lipid(i) (μg/μmol) |

ST004/lipid(f)

(μg/μmol) |

I.E. (%) |

Mean size (nm)

(PdI) |

ζ pot.

(mV) |

DMPC:DOPE:DSPE-PEG

(50:45:5) |

400 |

11 ± 3 |

5 ± 1 |

46 ± 9 |

122 ± 2

(<0.1) |

-4 ± 2 |

| 1000 |

29 ± 4 |

15 ± 5 |

51 ± 15 |

104 ± 6

(<0.1) |

-5 ± 1 |

Table 2.

Half maximal effective concentration (EC50) of ST004 formulations and DTIC towards human and murine melanoma cell lines, after 24 and 48 h incubation.

Table 2.

Half maximal effective concentration (EC50) of ST004 formulations and DTIC towards human and murine melanoma cell lines, after 24 and 48 h incubation.

| EC50 (μM) |

|---|

| |

Free-ST004 |

LIP-ST004 |

DTIC |

| Cell line |

24 h |

48 h |

24 h |

48 h |

24 h |

| B16F10 |

47 ± 3 |

58 ± 1 |

87 ± 1 |

78 ± 3 |

>100 |

| A375 |

27 ± 4 |

17 ± 1 |

49 ± 2 |

31 ± 6 |

>100 |

| MNT-1 |

37 ± 4 |

24 ± 5 |

95 ± 3 |

55 ± 14 |

>100 |

| LIP-ST004: DMPC:DOPE:DSPE-PEG(50:45:5); DTIC: dacarbazine; Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=2-3). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).