Submitted:

02 September 2023

Posted:

05 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, P.P. Chelicerates. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R774–R778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battelle, B.-A. The Eyes of Limulus Polyphemus (Xiphosura, Chelicerata) and Their Afferent and Efferent Projections. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2006, 35, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kin, A.; Błażejowski, B. The Horseshoe Crab of the Genus Limulus: Living Fossil or Stabilomorph? PLoS One 2014, 9, e108036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battelle, B.-A.; Ryan, J.F.; Kempler, K.E.; Saraf, S.R.; Marten, C.E.; Warren, W.C.; Minx, P.J.; Montague, M.J.; Green, P.J.; Schmidt, S.A.; et al. Opsin Repertoire and Expression Patterns in Horseshoe Crabs: Evidence from the Genome of Limulus Polyphemus (Arthropoda: Chelicerata). Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 1571–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, D.C.; Conley, K.W.; Plachetzki, D.C.; Kempler, K.; Battelle, B.-A.; Brown, N.L. Isolation and Expression of Pax6 and Atonal Homologues in the American Horseshoe Crab, Limulus Polyphemus. Dev. Dyn. 2008, 237, 2209–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerny, T.; Halder, G.; Kloter, U.; Souabni, A.; Gehring, W.J.; Busslinger, M. Twin of Eyeless, a Second Pax-6 Gene of Drosophila, Acts Upstream of Eyeless in the Control of Eye Development. Mol. Cell 1999, 3, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

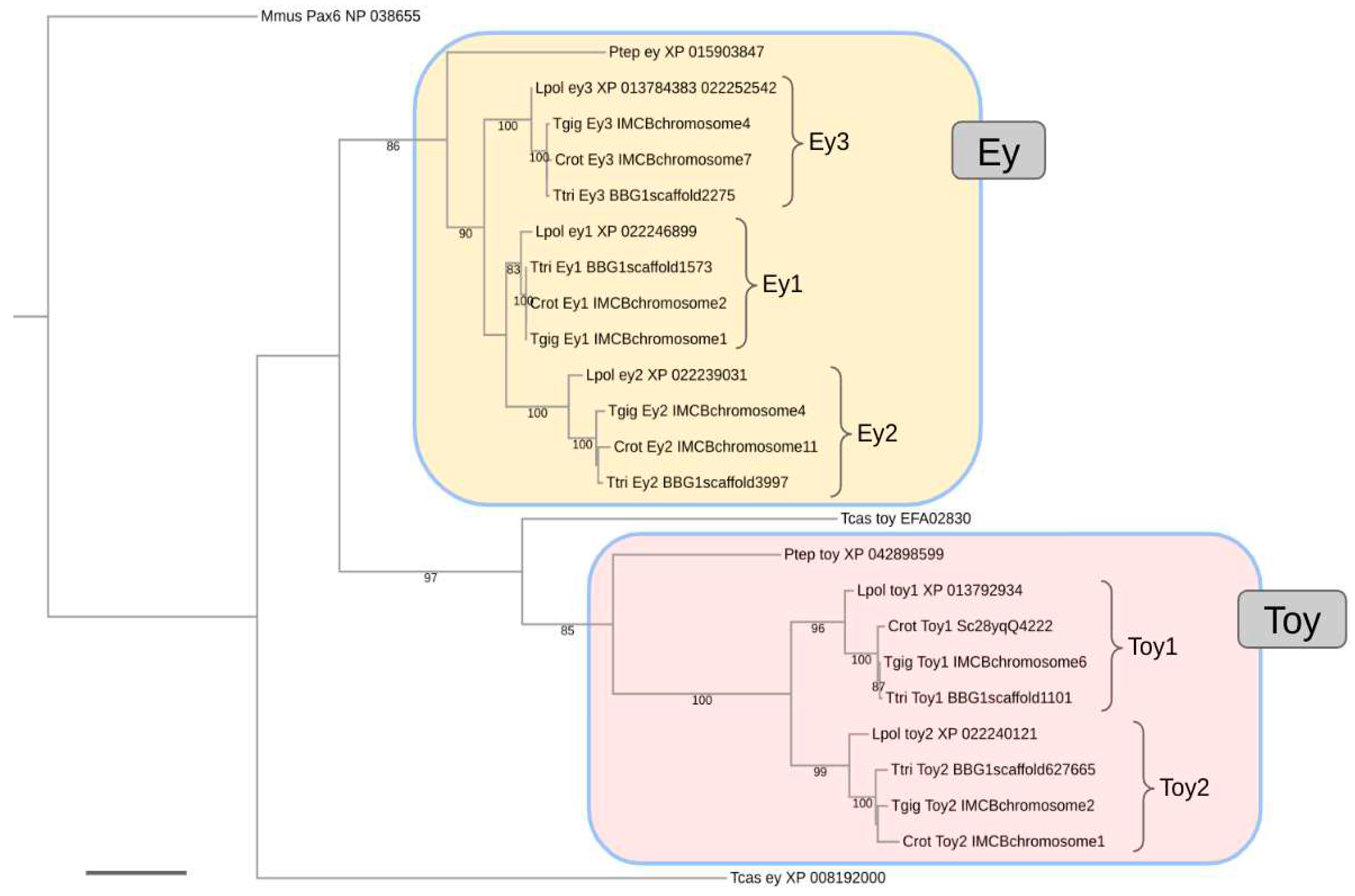

- Friedrich, M. Ancient Genetic Redundancy of Eyeless and Twin of Eyeless in the Arthropod Ocular Segment. Dev. Biol. 2017, 432, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, M. Coming into Clear Sight at Last: Ancestral and Derived Events during Chelicerate Visual System Development. Bioessays 2022, 44, e2200163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

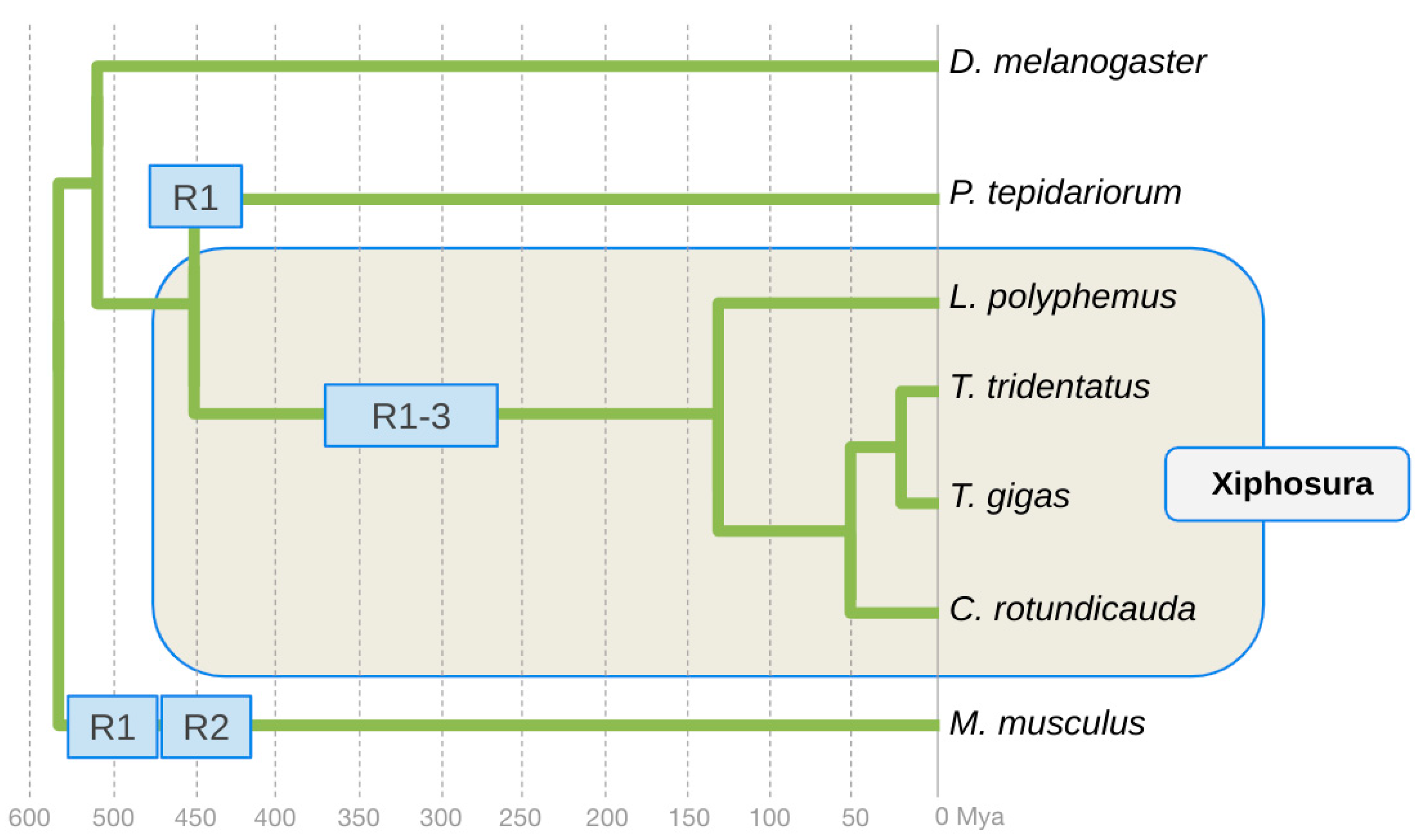

- Kenny, N.J.; Chan, K.W.; Nong, W.; Qu, Z.; Maeso, I.; Yip, H.Y.; Chan, T.F.; Kwan, H.S.; Holland, P.W.H.; Chu, K.H.; et al. Ancestral Whole-Genome Duplication in the Marine Chelicerate Horseshoe Crabs. Heredity 2016, 116, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanacredi, J.T.; Botton, M.L.; Smith, D. Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs; Springer Science & Business Media, 2009; ISBN 9780387899596. [Google Scholar]

- Lamsdell, J.C. The Phylogeny and Systematics of Xiphosura. PeerJ 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chen, D.; Ruan, L.; Kong, Y.; Shi, H.; Chen, M.; Chen, J. The Draft Genome of Horseshoe Crab Tachypleus Tridentatus Reveals Its Evolutionary Scenario and Well-Developed Innate Immunity. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

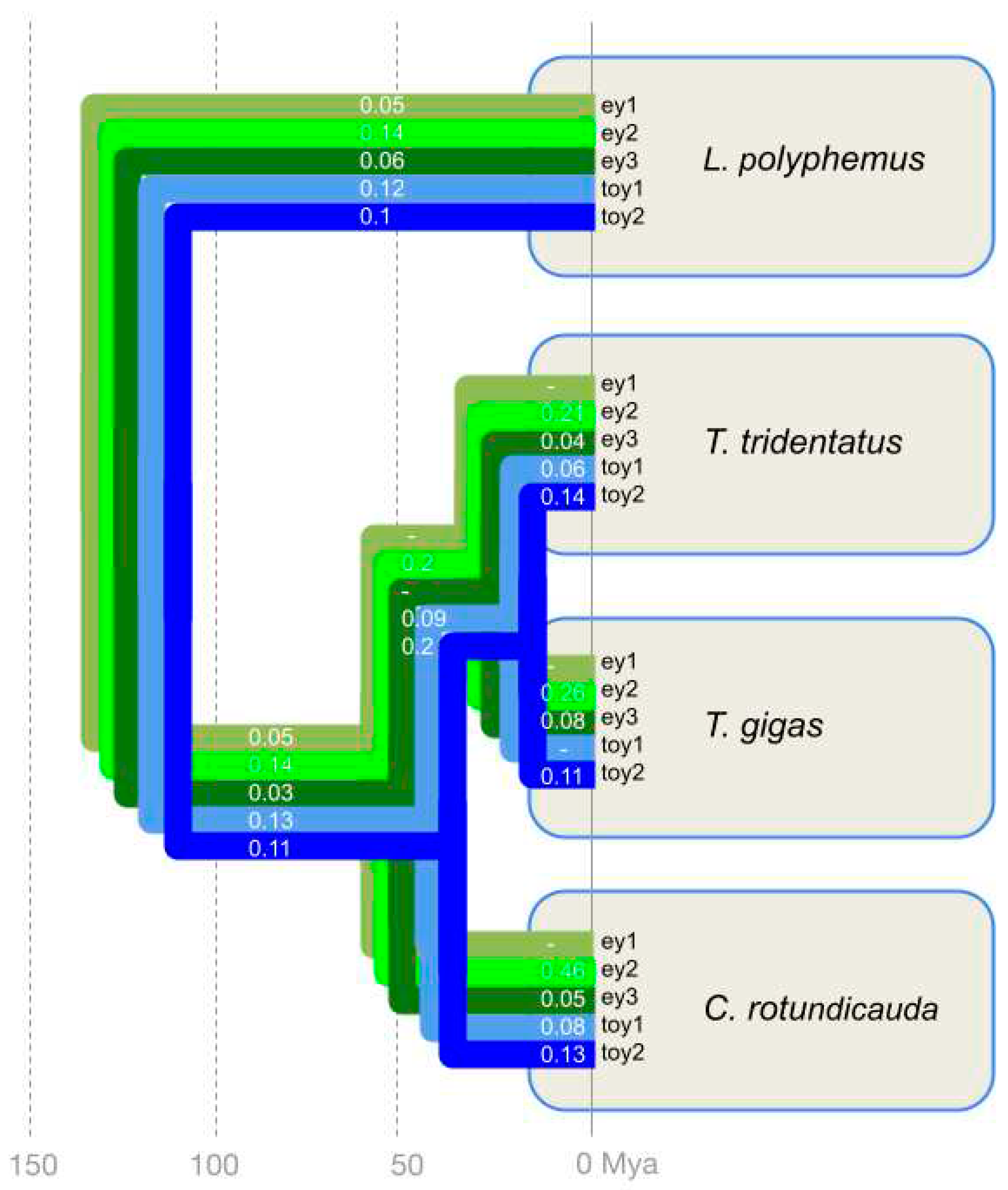

- Obst, M.; Faurby, S.; Bussarawit, S.; Funch, P. Molecular Phylogeny of Extant Horseshoe Crabs (Xiphosura, Limulidae) Indicates Paleogene Diversification of Asian Species. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2012, 62, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shingate, P.; Ravi, V.; Prasad, A.; Tay, B.-H.; Garg, K.M.; Chattopadhyay, B.; Yap, L.-M.; Rheindt, F.E.; Venkatesh, B. Chromosome-Level Assembly of the Horseshoe Crab Genome Provides Insights into Its Genome Evolution. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shingate, P.; Ravi, V.; Prasad, A.; Tay, B.-H.; Venkatesh, B. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of the Coastal Horseshoe Crab (Tachypleus Gigas). Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 1748–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nong, W.; Qu, Z.; Li, Y.; Barton-Owen, T.; Wong, A.Y.P.; Yip, H.Y.; Lee, H.T.; Narayana, S.; Baril, T.; Swale, T.; et al. Horseshoe Crab Genomes Reveal the Evolution of Genes and microRNAs after Three Rounds of Whole Genome Duplication. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simakov, O.; Marlétaz, F.; Yue, J.-X.; O’Connell, B.; Jenkins, J.; Brandt, A.; Calef, R.; Tung, C.-H.; Huang, T.-K.; Schmutz, J.; et al. Deeply Conserved Synteny Resolves Early Events in Vertebrate Evolution. Nat Ecol Evol 2020, 4, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, S. Evolution by Gene Duplication. 1970.

- Sacerdot, C.; Louis, A.; Bon, C.; Berthelot, C.; Roest Crollius, H. Chromosome Evolution at the Origin of the Ancestral Vertebrate Genome. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, Y.; Shingate, P.; Ravi, V.; Pillai, N.E.; Prasad, A.; McLysaght, A.; Venkatesh, B. Reconstruction of Proto-Vertebrate, Proto-Cyclostome and Proto-Gnathostome Genomes Provides New Insights into Early Vertebrate Evolution. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwager, E.E.; Sharma, P.P.; Clarke, T.; Leite, D.J.; Wierschin, T.; Pechmann, M.; Akiyama-Oda, Y.; Esposito, L.; Bechsgaard, J.; Bilde, T.; et al. The House Spider Genome Reveals an Ancient Whole-Genome Duplication during Arachnid Evolution. BMC Biol. 2017, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchler, J.A.; Yang, H. The Multiple Fates of Gene Duplications: Deletion, Hypofunctionalization, Subfunctionalization, Neofunctionalization, Dosage Balance Constraints, and Neutral Variation. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 2466–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmin, E.; Taylor, J.S.; Boone, C. Retention of Duplicated Genes in Evolution. Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weadick, C.J.; Chang, B.S.W. Complex Patterns of Divergence among Green-Sensitive (RH2a) African Cichlid Opsins Revealed by Clade Model Analyses. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des Marais, D.L.; Rausher, M.D. Escape from Adaptive Conflict after Duplication in an Anthocyanin Pathway Gene. Nature 2008, 454, 762–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vavouri, T.; Semple, J.I.; Lehner, B. Widespread Conservation of Genetic Redundancy during a Billion Years of Eukaryotic Evolution. Trends Genet. 2008, 24, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, M.A.; Boerlijst, M.C.; Cooke, J.; Smith, J.M. Evolution of Genetic Redundancy. Nature 1997, 388, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberles, D.A.; Kolesov, G.; Dittmar, K. Understanding Gene Duplication through Biochemistry and Population Genetics. Evolution after gene duplication 2010, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, M. The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution. Sci. Am. 1979, 241, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notredame, C.; Higgins, D.G.; Heringa, J. T-Coffee: A Novel Method for Fast and Accurate Multiple Sequence Alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 302, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML Version 8: A Tool for Phylogenetic Analysis and Post-Analysis of Large Phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for Inference of Large Phylogenetic Trees. In Proceedings of the 2010 Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE); 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, C.; Liberles, D.A. A Systematic Search for Positive Selection in Higher Plants (Embryophytes). BMC Plant Biol. 2006, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberles, D.A. Evaluation of Methods for Determination of a Reconstructed History of Gene Sequence Evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001, 18, 2040–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.B.; Grenier, J.K.; Weatherbee, S.D. From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, N.; Epstein, J.A. Getting Your Pax Straight: Pax Proteins in Development and Disease. Trends Genet. 2002, 18, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronhamn, J.; Frei, E.; Daube, M.; Jiao, R.; Shi, Y.; Noll, M.; Rasmuson-Lestander, A. Headless Flies Produced by Mutations in the Paralogous Pax6 Genes Eyeless and Twin of Eyeless. Development 2002, 129, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, J.; Pauli, T.; Seimiya, M.; Udolph, G.; Gehring, W.J. Genetic Interactions of Eyes Absent, Twin of Eyeless and Orthodenticle Regulate Sine Oculis Expression during Ocellar Development in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 2010, 344, 1088–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, G.; Callaerts, P.; Gehring, W.J. Induction of Ectopic Eyes by Targeting Expression of the Eyeless Gene in Drosophila. Science 1995, 267, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudouin-Gonzalez, L.; Harper, A.; McGregor, A.P.; Sumner-Rooney, L. Regulation of Eye Determination and Regionalization in the Spider Parasteatoda Tepidariorum. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schomburg, C.; Turetzek, N.; Schacht, M.I.; Schneider, J.; Kirfel, P.; Prpic, N.-M.; Posnien, N. Molecular Characterization and Embryonic Origin of the Eyes in the Common House Spider Parasteatoda Tepidariorum. Evodevo 2015, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, L.; Schmid, A.; Eriksson, B.J. Differential Expression of Retinal Determination Genes in the Principal and Secondary Eyes of Cupiennius Salei Keyserling (1877). Evodevo 2015, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.P.; Isambert, H. OHNOLOGS v2: A Comprehensive Resource for the Genes Retained from Whole Genome Duplication in Vertebrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D724–D730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Weber, M.; Zarinkamar, N.; Posnien, N.; Friedrich, F.; Wigand, B.; Beutel, R.; Damen, W.G.M.; Bucher, G.; Klingler, M.; et al. Probing the Drosophila Retinal Determination Gene Network in Tribolium (II): The Pax6 Genes Eyeless and Twin of Eyeless. Dev. Biol. 2009, 333, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Q.; Chen, Q.; Friedrich, M. The Pax6 Genes Eyeless and Twin of Eyeless Are Required for Global Patterning of the Ocular Segment in the Tribolium Embryo. Dev. Biol. 2014, 394, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, G.; Callaerts, P.; Flister, S.; Walldorf, U.; Kloter, U.; Gehring, W.J. Eyeless Initiates the Expression of Both Sine Oculis and Eyes Absent during Drosophila Compound Eye Development. Development 1998, 125, 2181–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvekl, A.; Callaerts, P. PAX6: 25th Anniversary and More to Learn. Exp. Eye Res. 2017, 156, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements, J.; Hens, K.; Francis, C.; Schellens, A.; Callaerts, P. Conserved Role for the Drosophila Pax6 Homolog Eyeless in Differentiation and Function of Insulin-Producing Neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 16183–16188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feiner, N.; Meyer, A.; Kuraku, S. Evolution of the Vertebrate Pax4/6 Class of Genes with Focus on Its Novel Member, the Pax10 Gene. Genome Biol. Evol. 2014, 6, 1635–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manousaki, T.; Feiner, N.; Begemann, G.; Meyer, A.; Kuraku, S. Co-Orthology of Pax4 and Pax6 to the Fly Eyeless Gene: Molecular Phylogenetic, Comparative Genomic, and Embryological Analyses. Evol. Dev. 2011, 13, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.J.; Beavan, A.; Chabot, P.J.; McPeek, M.A.; Pisani, D.; Fromm, B.; Simakov, O. MicroRNAs as Indicators into the Causes and Consequences of Whole-Genome Duplication Events. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2022, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aase-Remedios, M.E.; Ferrier, D.E.K. Improved Understanding of the Role of Gene and Genome Duplications in Chordate Evolution With New Genome and Transcriptome Sequences. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, L.Z.; Ocampo Daza, D. A New Look at an Old Question: When Did the Second Whole Genome Duplication Occur in Vertebrate Evolution? Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).