Submitted:

04 September 2023

Posted:

05 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Syngas from biomass as raw material for methanation catalytic process

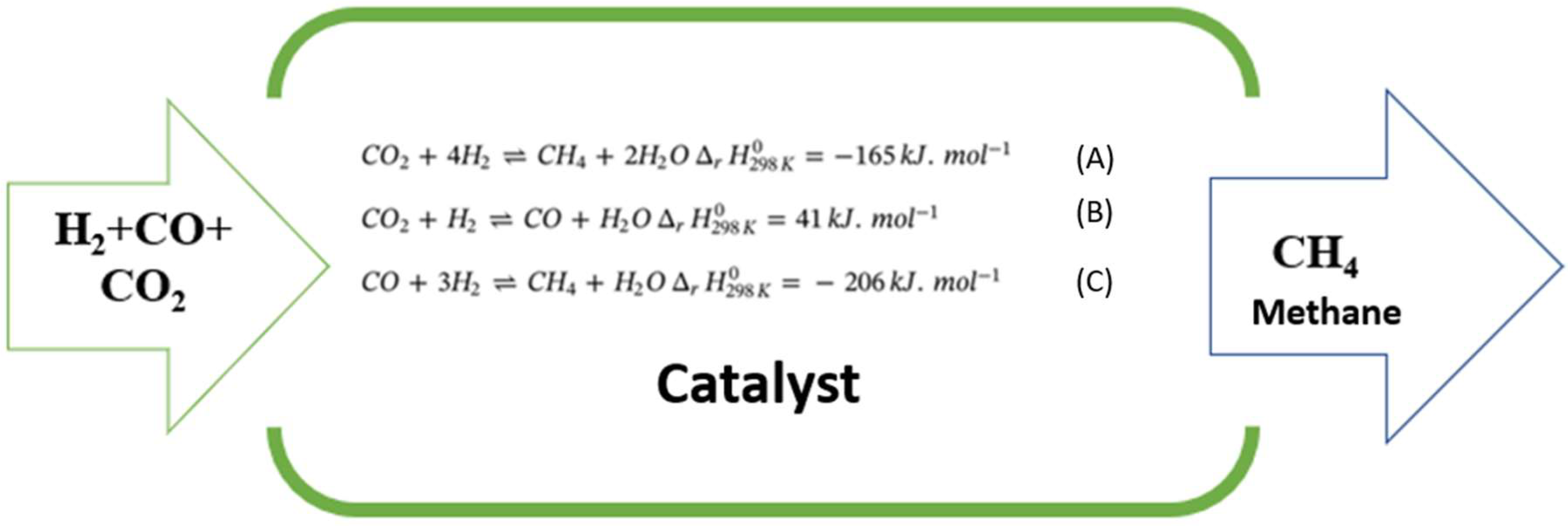

1.2. Catalytic methane production

1.3. Ni/ZrO2 catalyst

| Catalyst | Ea (kJ mol-1) | α | β | A (L g-1 h-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni/ZrO2-P | 93.61 | 0.65 | 0.29 | 2.48×1010 |

| Ni/ZrO2-C | 93.12 | 0.44 | 0.54 | 6.93×109 |

1.4. Commercial Ni/Al2O3 catalyst

| Parameter | KCO | KH2O | KCO2 | KH2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q (KJ/mol) | 40.6 | 14.5 | 9.72 | 52.0 |

| Ko (bar-1) | 2.39x10-3 | 6.09x10-1 | 1.07 | 5.2x10-5 |

| Parameter | kCO2,meth | kRWGS | kCO,meth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ea (KJ/mol) | 110 | 97.1 | 97.3 |

| ko (mol/min*g) | 1.14x108 | 1.78x106 | 2.23x108 |

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Syngas description

| Steam/biomass (S/B) ratio | S/B 0.5 | S/B 1.0 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (oC) | 700 | 800 | 700 | 800 |

| Hydrogen (%) | 48.46 | 46.51 | 54.41 | 50.19 |

| Methane (%) | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.09 |

| Carbon monoxide (%) | 24.21 | 44.06 | 18.87 | 37.81 |

| Carbon dioxide (%) | 25.05 | 7.68 | 24.81 | 11.39 |

| Ethane (%) | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| Ethylene (%) | 1.03 | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.09 |

| Propane (%) | 0.74 | 0.39 | 0.82 | 0.37 |

| H2S (%) | 0.1 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.03 |

| H2/CO2 ratio | 1.93 | 6.06 | 2.19 | 4.41 |

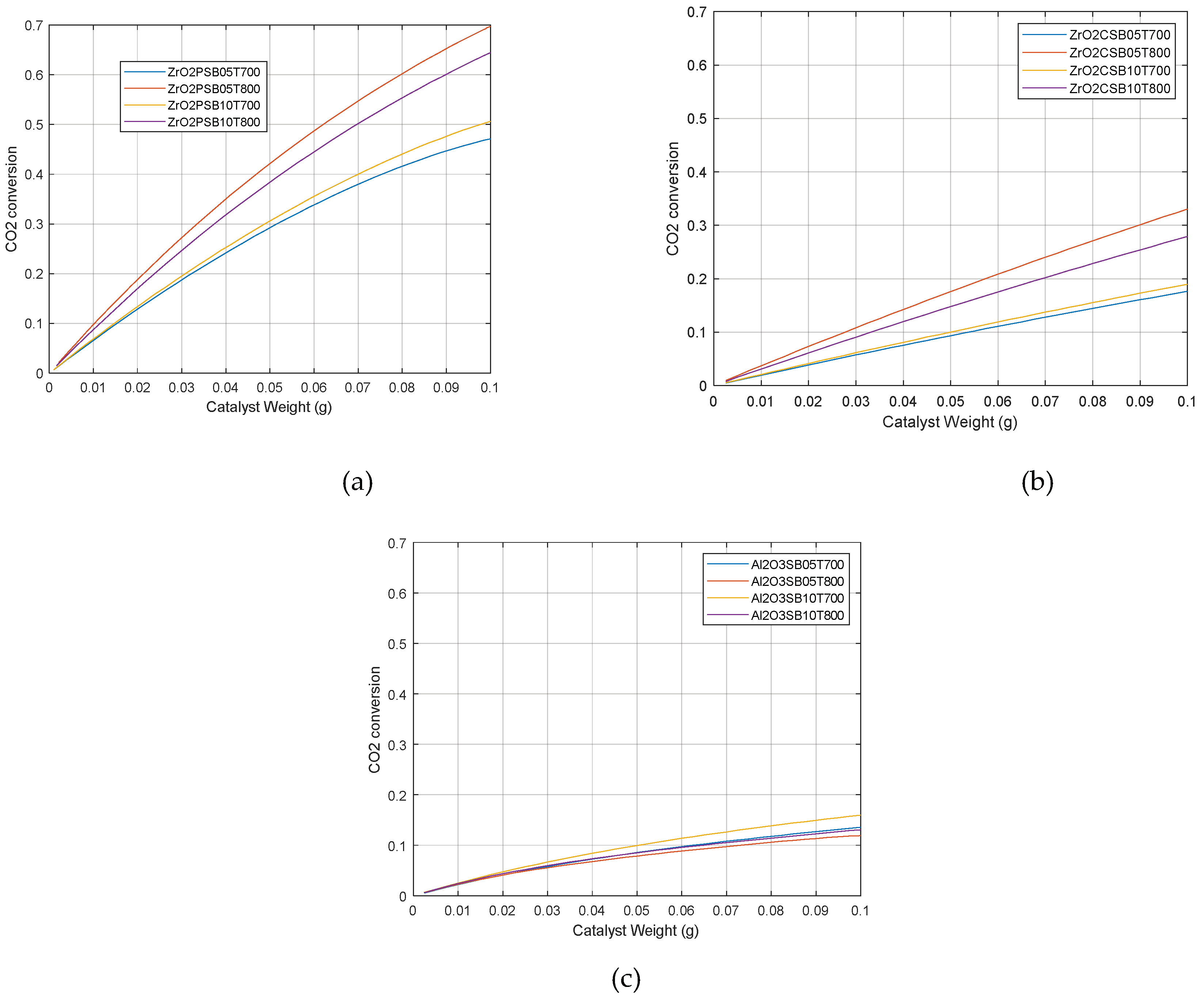

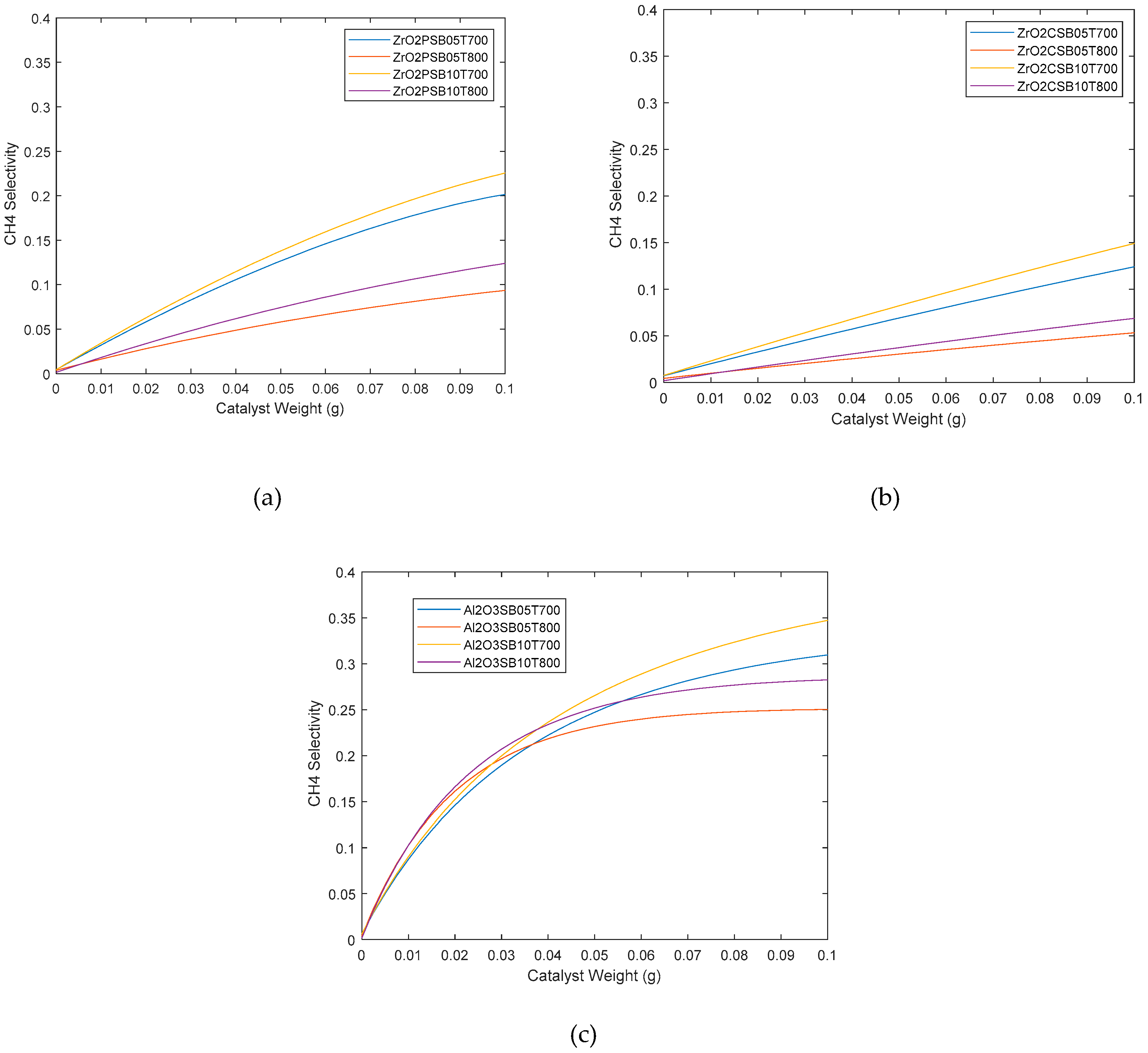

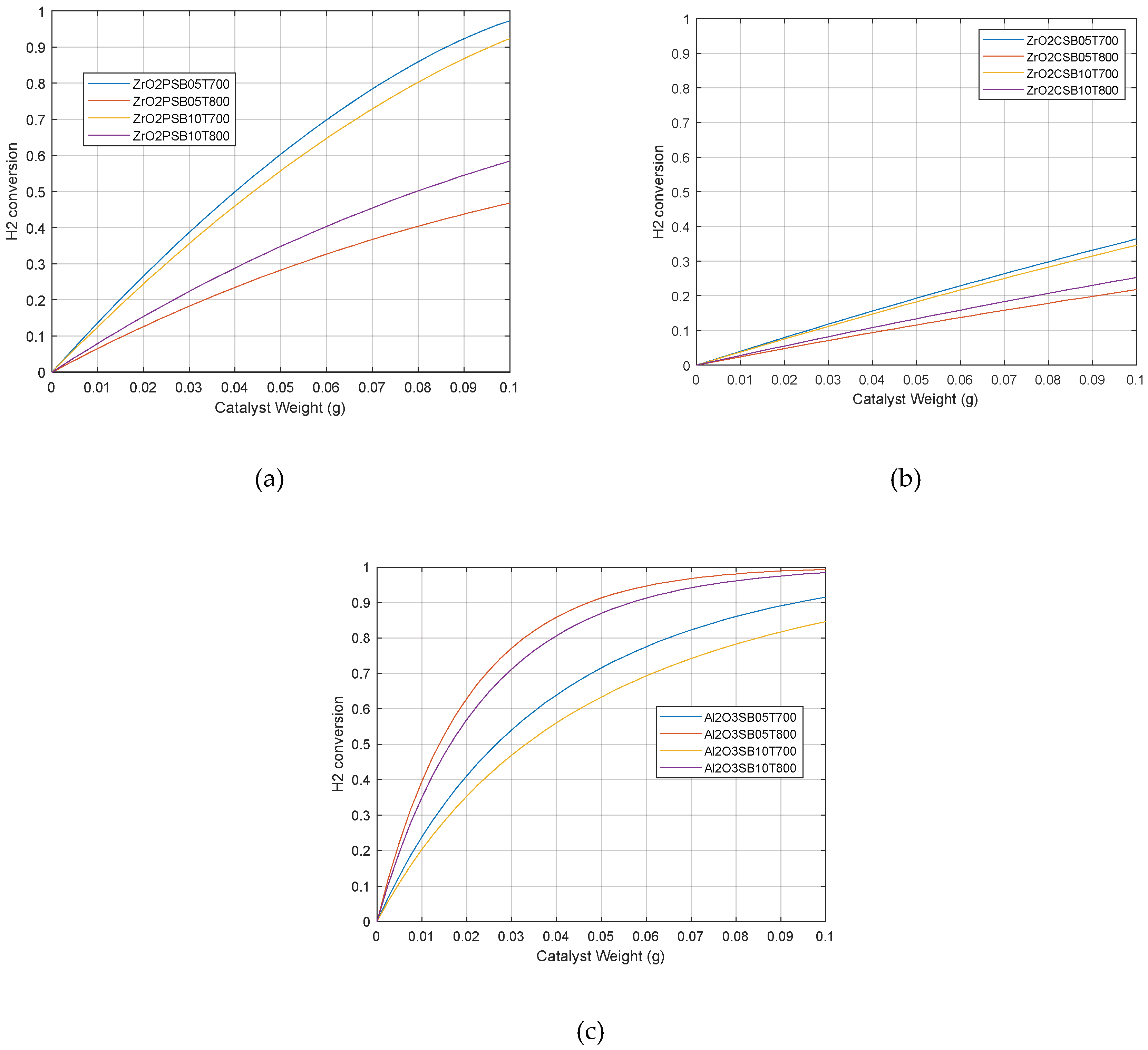

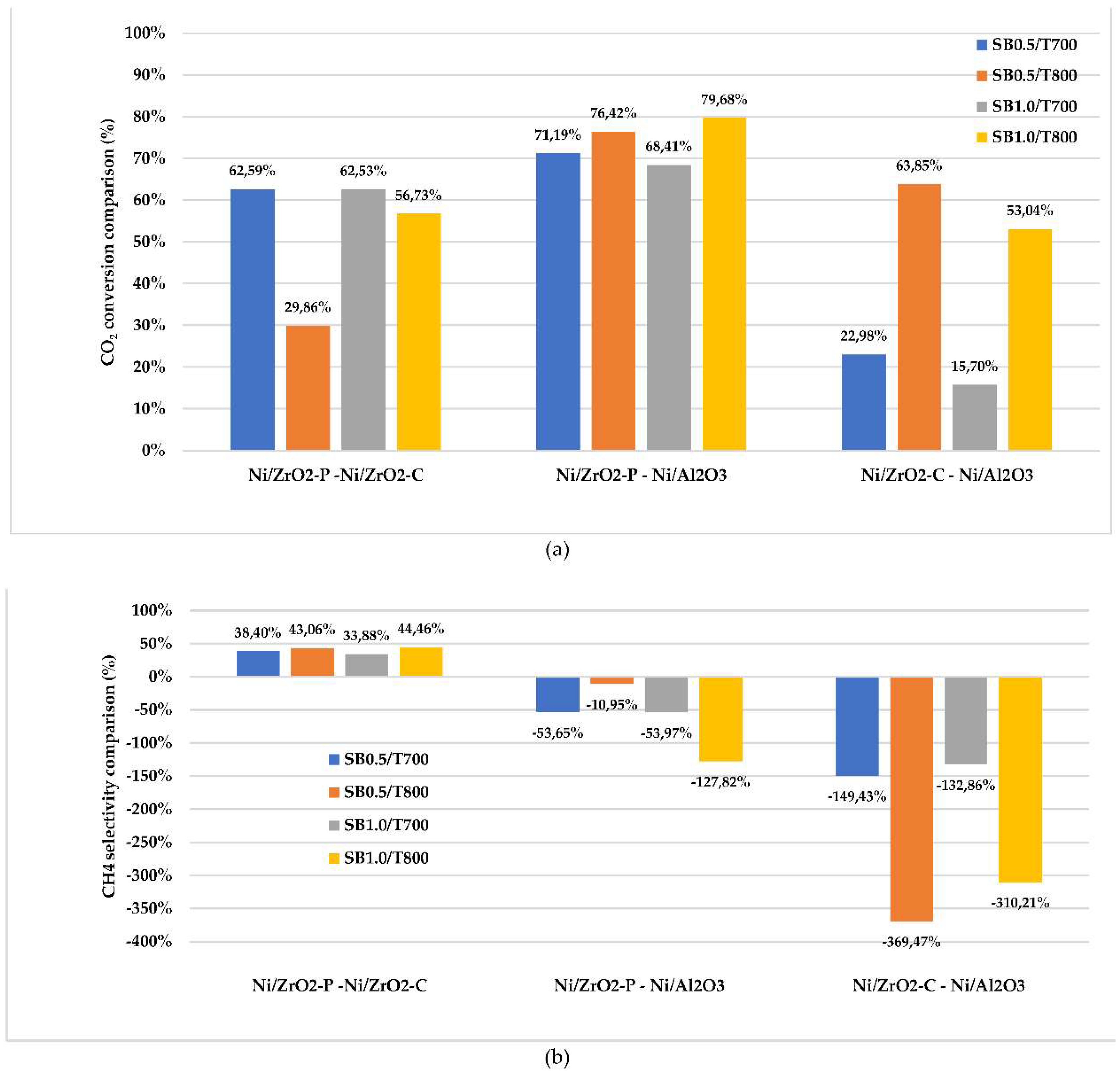

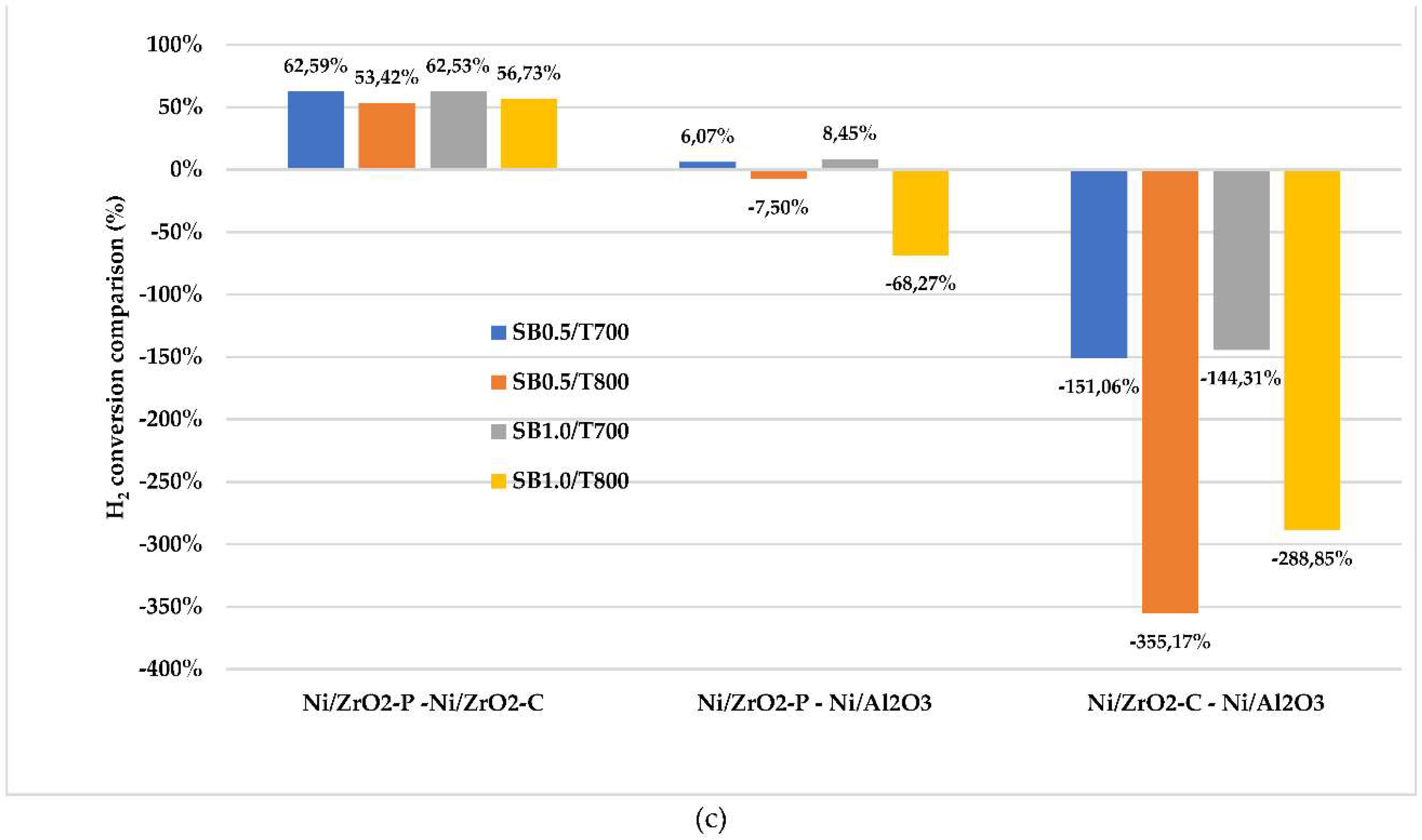

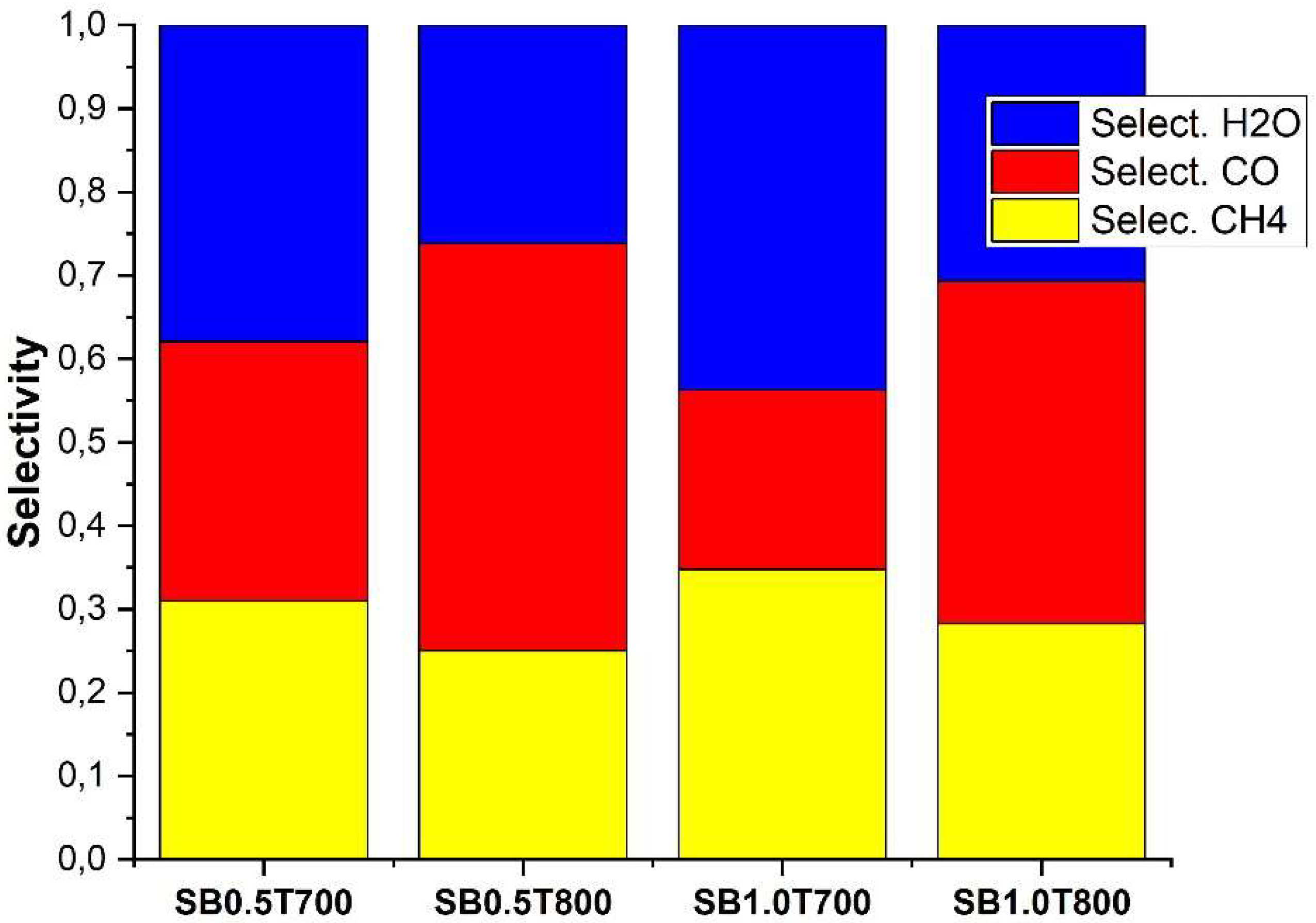

2.2. Catalytic simulation of methanation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Gasification experimental system

3.2. Mathematical model for the methanation catalytic packed bed reactor simulation

- Negligible radial diffusion: concentration and temperature profiles are assumed to be constants, which leads to a one-dimensional model.

- Constant radial speed.

- Temperature and pressure profiles in the catalyst are assumed to be constants (homogeneous catalytic particle).

- As in [13], the mechanisms related to catalyst deactivation, such as sulfur poisoning or carbon formation via the Boudouard reaction, are not taken into consideration or disregarded in the present study.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Champon, A. Bengaouer, A. Chaise, S. Thomas, and A. C. Roger, “Carbon dioxide methanation kinetic model on a commercial Ni/Al2O3 catalyst,” J. CO2 Util., vol. 34, no. March, pp. 256–265, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.jcou.2019.05.030. [CrossRef]

- V. Scharl, F. Fischer, S. Herrmann, S. Fendt, and H. Spliethoff, “Applying Reaction Kinetics to Pseudohomogeneous Methanation Modeling in Fixed-Bed Reactors,” Chem. Eng. Technol., vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 1224–1233, 2020, doi: 10.1002/ceat.201900535. [CrossRef]

- K. P. Brooks, J. Hu, H. Zhu, and R. J. Kee, “Methanation of carbon dioxide by hydrogen reduction using the Sabatier process in microchannel reactors,” Chem. Eng. Sci., vol. 62, no. 4, pp. 1161–1170, 2007, doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2006.11.020. [CrossRef]

- L. Shen, J. Xu, M. Zhu, and Y. F. Han, “Essential role of the support for nickel-based CO2 methanation catalysts,” ACS Catal., vol. 10, no. 24, pp. 14581–14591, 2020, doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c03471. [CrossRef]

- M. Romero-Sáez, A. B. Dongil, N. Benito, R. Espinoza-González, N. Escalona, and F. Gracia, “CO2 methanation over nickel-ZrO2 catalyst supported on carbon nanotubes: A comparison between two impregnation strategies,” Appl. Catal. B Environ., vol. 237, no. March, pp. 817–825, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.06.045. [CrossRef]

- M. Marchi, E. Neri, F. M. Pulselli, and S. Bastianoni, “CO2 recovery from wine production: Possible implications on the carbon balance at territorial level,” J. CO2 Util., vol. 28, no. October, pp. 137–144, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.jcou.2018.09.021. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Clark, “Green chemistry for the second generation biorefinery – sustainable chemica manufacturing based on biomass,” J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol., vol. 82, no. May, pp. 603–609, 2007, doi: 10.1002/jctb. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Aristizábal-Alzate, P. N. Alvarado, and A. F. Vargas, “Biorefinery concept applied to phytochemical extraction and bio-syngas production using agro-industrial waste biomass: A review,” Ing. e Investig., vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 22–36, 2020, doi: 10.15446/ing.investig.v40n2.82539. [CrossRef]

- P. Esquivel and V. M. Jiménez, “Functional properties of coffee and coffee by-products,” Food Res. Int., vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 488–495, 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.05.028. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Murthy and M. Madhava Naidu, “Sustainable management of coffee industry by-products and value addition—A review,” Resour. Conserv. Recycl., vol. 66, pp. 45–58, 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2012.06.005. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Aristizábal-Alzate, P. N. Alvarado-Torres, and A. F. Vargas-Ramírez, “Simulation of methanol production from residual biomasses in a Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 packed bed reactor,” Rev. Fac. Ing., no. 102, pp. 115–124, 2022, doi: 10.17533/udea.redin.20200907. [CrossRef]

- P. A. U. Aldana et al., “Catalytic CO2 valorization into CH4 on Ni-based ceria-zirconia. Reaction mechanism by operando IR spectroscopy,” Catal. Today, vol. 215, pp. 201–207, 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2013.02.019. [CrossRef]

- S. Rönsch, J. Köchermann, J. Schneider, and S. Matthischke, “Global Reaction Kinetics of CO and CO2 Methanation for Dynamic Process Modeling,” Chem. Eng. Technol., vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 208–218, 2016, doi: 10.1002/ceat.201500327. [CrossRef]

- N. D. M. Ridzuan, M. S. Shaharun, M. A. Anawar, and I. Ud-Din, “Ni-Based Catalyst for Carbon Dioxide Methanation: A Review,” Catalysts, vol. 12, p. 469, 2022.

- V. Tongnan et al., “Process intensification of methane production via catalytic hydrogenation in the presence of ni-ceo2/cr2o3 using a micro-channel reactor,” Catalysts, vol. 11, no. 10, 2021, doi: 10.3390/catal11101224. [CrossRef]

- Molino, S. Chianese, and D. Musmarra, “Biomass gasification technology: The state of the art overview,” J. Energy Chem., vol. 25, pp. 10–25, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.jechem.2015.11.005. [CrossRef]

- hmad, N. A. Zawawi, F. H. Kasim, A. Inayat, and A. Khasri, “Assessing the gasification performance of biomass: A review on biomass gasification process conditions, optimization and economic evaluation,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 53, pp. 1333–1347, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.09.030. [CrossRef]

- V Bridgwater, “The technical and economic feasibility of biomass gasification for power generation,” vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 631–653, 1995.

- S. Heidenreich and P. U. Foscolo, “New concepts in biomass gasification,” Prog. Energy Combust. Sci., vol. 46, pp. 72–95, 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.pecs.2014.06.002. [CrossRef]

- H. Beohar, B. Gupta, V. K. Sethi, and M. Pandey, “Parametric Study of Fixed Bed Biomass Gasifier : A review,” Int. J. Therm. Technol., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 134–140, 2012.

- S. M. Santos, A. C. Assis, L. Gomes, C. Nobre, and P. Brito, “Waste Gasification Technologies: A Brief Overview,” Waste, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 140–165, 2022, doi: 10.3390/waste1010011. [CrossRef]

- M. La Villetta, M. Costa, and N. Massarotti, “Modelling approaches to biomass gasification: A review with emphasis on the stoichiometric method,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 74, no. November 2016, pp. 71–88, 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.02.027. [CrossRef]

- N. Couto, A. Rouboa, V. Silva, E. Monteiro, and K. Bouziane, “Influence of the biomass gasification processes on the final composition of syngas,” Energy Procedia, vol. 36, pp. 596–606, 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2013.07.068. [CrossRef]

- J. C. G. da Silva, J. L. F. Alves, G. D. Mumbach, S. L. F. Andersen, R. de F. P. M. Moreira, and H. J. Jose, “Hydrogen-rich syngas production from steam gasification of Brazilian agroindustrial wastes in fixed bed reactor: kinetics, energy, and gas composition,” Biomass Convers. Biorefinery, 2023, doi: 10.1007/s13399-023-04585-z. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Sansaniwal, K. Pal, M. A. Rosen, and S. K. Tyagi, “Recent advances in the development of biomass gasification technology: A comprehensive review,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 72, no. January, pp. 363–384, 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.038. [CrossRef]

- E. Aristizábal-Alzate, “Aplicación del concepto de biorrefinería a la pulpa de café, mediante extracción fitoquímica y procesos termoquímicos, para la obtención de productos de alto valor agregado,” Instituoto Tecnológico Metropolitano de Medellín, 2019.

- J. Lin et al., “Enhanced low-temperature performance of CO2 methanation over mesoporous Ni/Al2O3-ZrO2 catalysts,” Appl. Catal. B Environ., vol. 243, pp. 262–272, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.10.059. [CrossRef]

- Grimalt-Alemany, I. V. Skiadas, and H. N. Gavala, “Syngas biomethanation: state-of-the-art review and perspectives,” Biofuels, Bioprod. Biorefining, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 139–158, 2018, doi: 10.1002/bbb.1826. [CrossRef]

- X. Jia, X. Zhang, N. Rui, X. Hu, and C. jun Liu, “Structural effect of Ni/ZrO2 catalyst on CO2 methanation with enhanced activity,” Appl. Catal. B Environ., vol. 244, no. June 2018, pp. 159–169, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.11.024. [CrossRef]

- H. Knözinger and K. Kochloefl, “Heterogeneous Catalysis and Solid Catalysts,” Ullmann’s Encycl. Ind. Chem., 2003, doi: 10.1002/14356007.a05_313. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Fogler, Elementos de ingeniería de las reacciones químicas. Pearson Educación, 2001.

- O. Levenspiel, “Ingenieria de las reacciones quimicas,” Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, vol. 53, no. 9. pp. 277–293, 2002, doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).