1. Introduction

Lesions of the knee cartilage are very frequent, it is estimated that they occur in up to 60% of patients that are subject of a knee arthroscopic procedure [

1]. Patients with these lesions frequently experience pain, swelling, functional impairment, and a reduction in the quality of life [

2]. There is a limited capacity for self-repair of chondral defects, and it has been documented that untreated lesions can predispose the joint to increase in cartilage loss and to early onset osteoarthritis (OA) [

3]. Chondral lesions are most commonly found on the patella and medial femoral condyle [

4]. Lesions that comprise chondral full thickness, are classified as grade IV according to the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS), and are considered a real challenge for treatment, often with, slow or difficult to achieve, full recovery [

2,

5]. Several treatment options for symptomatic patients have been developed, however, no clear gold-standard treatment has been established, since most of the interventions will depend on several factors, such as: the size and place of the lesion, the presence of osteoarthritis and other comorbidities, and additional demographic variables [

6].

Currently, treatment of cartilage defects is a clinical challenge, not just from the standing point of view of the surgery and the technique implemented but also, because after the surgical intervention, the resulting reparative fibrocartilage has inferior biomechanical properties when compared to the native cartilage, and even more, reparative fibrocartilage seems to be more susceptible to degenerative changes leading to early onset OA [

7].

Several surgical techniques have been proposed to try to improve the regeneration of the articular cartilage, among them is the two-step autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) [

8], microfractures, and recently the use of hyaluronic acid-based scaffolds for chondrocyte implantation [

9]. Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a natural polymer that promotes the formation of new hyaline-like cartilage tissue that has reported satisfactory clinical results however at an elevated cost. There is also lack of standardization on techniques and lack of adequate evaluations, rendering the use of this new approached to have a limited use. The aim of this study was to analyze functionality and radiographic recovery in patients that were surgically intervened for the reparation of full thickness cartilage lesions (ICRS grade IV) of the knee, either with a hyaluronan-based 3-D scaffold or the microfracture technique over a one-year period.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Population

To be selected as study participants, patients needed to fulfill the following inclusion criteria: >18 years old, who underwent arthroscopy in the same center, and performed by the same surgeon during the observation period Jan-Dec of 2019.Exclusion criteria was the requirement for bone grafting, osteonecrosis, and the presence of concomitant inflammatory arthropathies who required intra-articular injections of steroids.

Patients were divided into two groups, according to the technique used during the arthroscopic intervention into the microfractures and HA 3-D scaffold groups. The decision for the technique selected was based on the availability of the patients’ insurance company to pay for the HA 3-D scaffold.

Clinical information from patients was obtained from the electronic medical records. Baseline assessments were obtained from measurements performed on the day of admission for surgery. At this point we collected information related to demographic aspects, characteristics of the lesion. After the surgery, we searched for patients’ clinical information at 6 and 12 months.

Ethical considerations.

The conduction of the study was reported to the local IRB, and signature of informed consent was exempt due to the retrospective nature of the study (CEI/2023/001).

Surgical techniques.

Surgery was performed in all patients under spinal anesthesia with routine sterile preparation and draping. After arthroscopic evaluation, the knee was approached with a mini-arthrotomy, the chondral defect was prepared and debrided with the use of curettes to remove chondral free fragments and calcified lesions while avoiding penetration of the subchondral bone, damaged cartilage was removed until the defect was evident, then approximately 5 mL of bone marrow aspirate cells (BMAC) was harvested from the femur. The aspirate was then located into the patient’s lesion, either by the generation of microfractures with BMA directed through the cylindric containment of the fracture, or with the use of a three-dimensional scaffold imbibed in the BMAC. For the latter, chondral defects were measured vertically and horizontally, the three-dimensional scaffolds were tailored to the defect size and shape of the lesion, soaked in BMAC, and implanted in the defect site. The scaffolds were secured to the surrounding previously cleaned cartilage using intraarticular sutures or with the use of an arthroscopic retracting system.

Functional Status.

To evaluate patient´s functional status, the Modified Cincinnati Knee Rating System (MCKRS) was obtained preoperatively and post-surgery at 12 months.

The system consists of 12 scored questions that cover the domains of pain, swelling, function and activity-level. The total score is calculated as the sum of all question responses, with 100 representing the best/excellent knee function, and 0 representing the worst/poor knee function [

10]. Results are interpreted as follows: <30 poor, 30-54 fair, 55-79 good, and >80 excellent.

MRI assessment & Henderson Scale.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results were collected preoperatively, six and twelve months after the surgery, performed by an independent radiology consultant blinded to the type of cartilage repair. After the evaluation of the images, the radiologist obtained a score for each patient based on a system developed by Henderson et al. [

11] Parameters reviewed included defect fill, signal, effusion, and subchondral edema, which were scored on a scale from 1 to 4, where 1 represents a normal knee and 4 a severe full thickness defect.

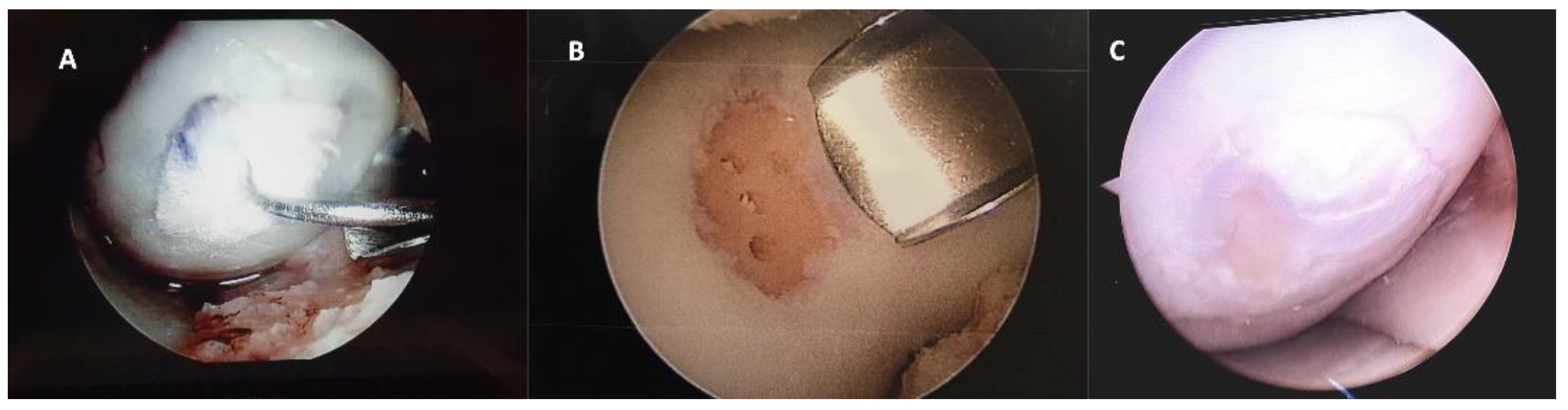

Second look arthroscopy.

In some cases, a second-look arthroscopy was performed, due to the presence of mechanical symptoms, crepitus, or pain, and for those who required surgical treatments for other reason unrelated to the previous surgical procedure. During the second look arthroscopy, grafts were inspected and evaluated according to the ICRS cartilage repair assessment scoring system, which includes the degree of defect, fill, graft integration to adjacent normal articular surface, and gross appearance of the graft surface.

Statistical Methods.

Descriptive analysis was performed by mean and SD for continuous data and proportions for categorical data, as non-parametric alternates we used medians and interquartile ranges. Inferences were made by use of chi-square for categorical data and students T test (two tailed) for continuous data and Kruskal-Wallis for variables with non-parametric distribution. We conducted an analysis of response profiles to test if there was a difference in the pattern of change over time in patients receiving the two interventions. Significant differences were set to a value of p<0.05. We used the statistical software STATA IC 16.

3. Results

We included a total of 33 patients, who underwent surgery during the period from Feb-Dec 2019. The group treated with HA 3-D scaffold comprised 12 patients and the group treated with microfractures was of 21 patients. All patients had lesions classified as grade IV according to the ICRS, their functional status was of fair performance and only a few had poor performance status. Most lesions were located on the right knee, and 90% of patients reported having an amateur type of physical activity.

Table 1 shows frequencies and comparisons for both groups, without significant distinctions at baseline.

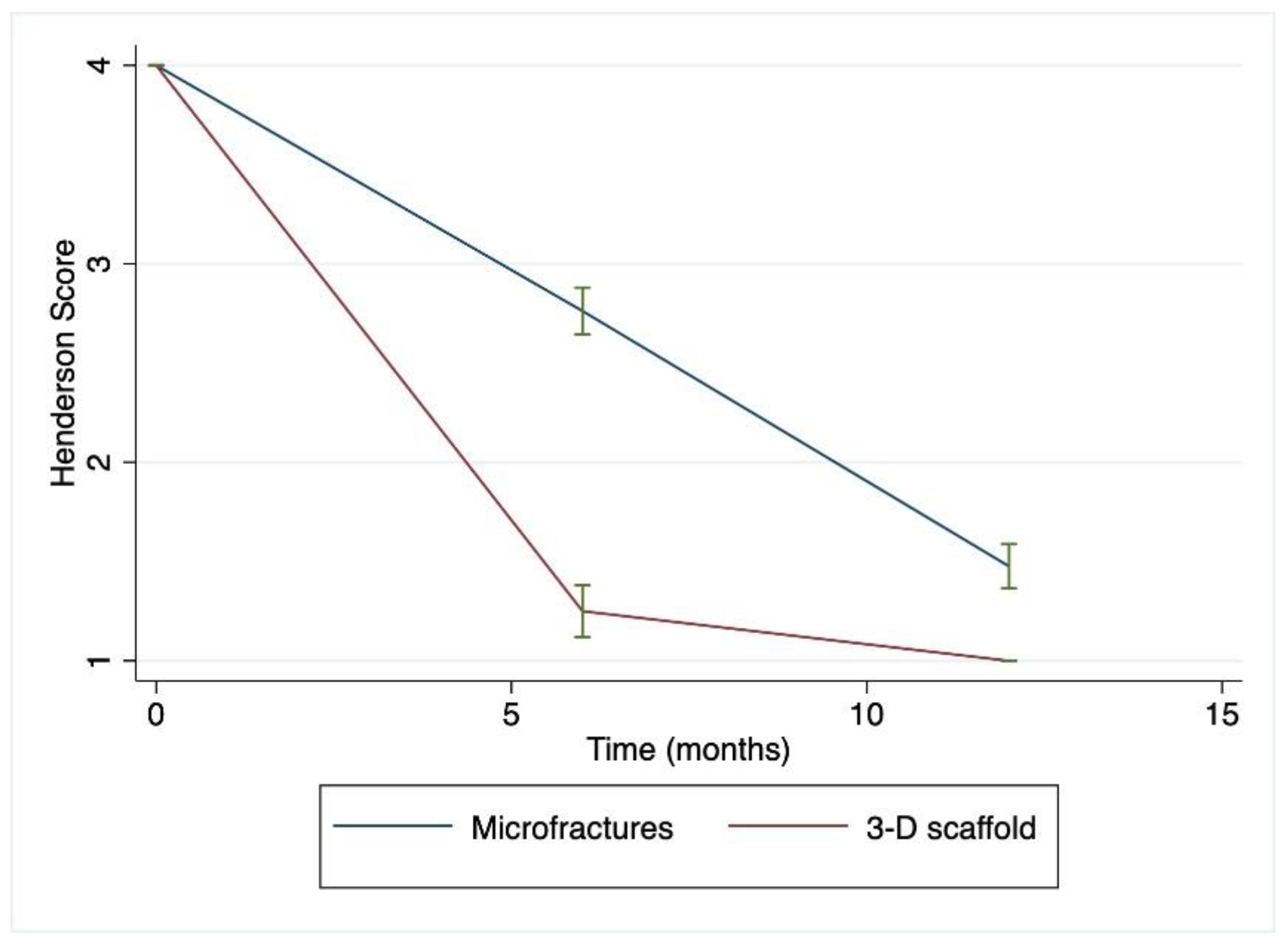

With respect to surgery and the immediate postoperative period, there were no significant complications reported for any patient. After 6 months of the surgery patients were asked to undergo a new MRI to assess changes in the Henderson scale, a statistically significant improvement was found in the group treated with the 3-D scaffold to a median (ICR) of 1 (1-1.5) (p<0.001), which was not evident in the microfractures treated group.

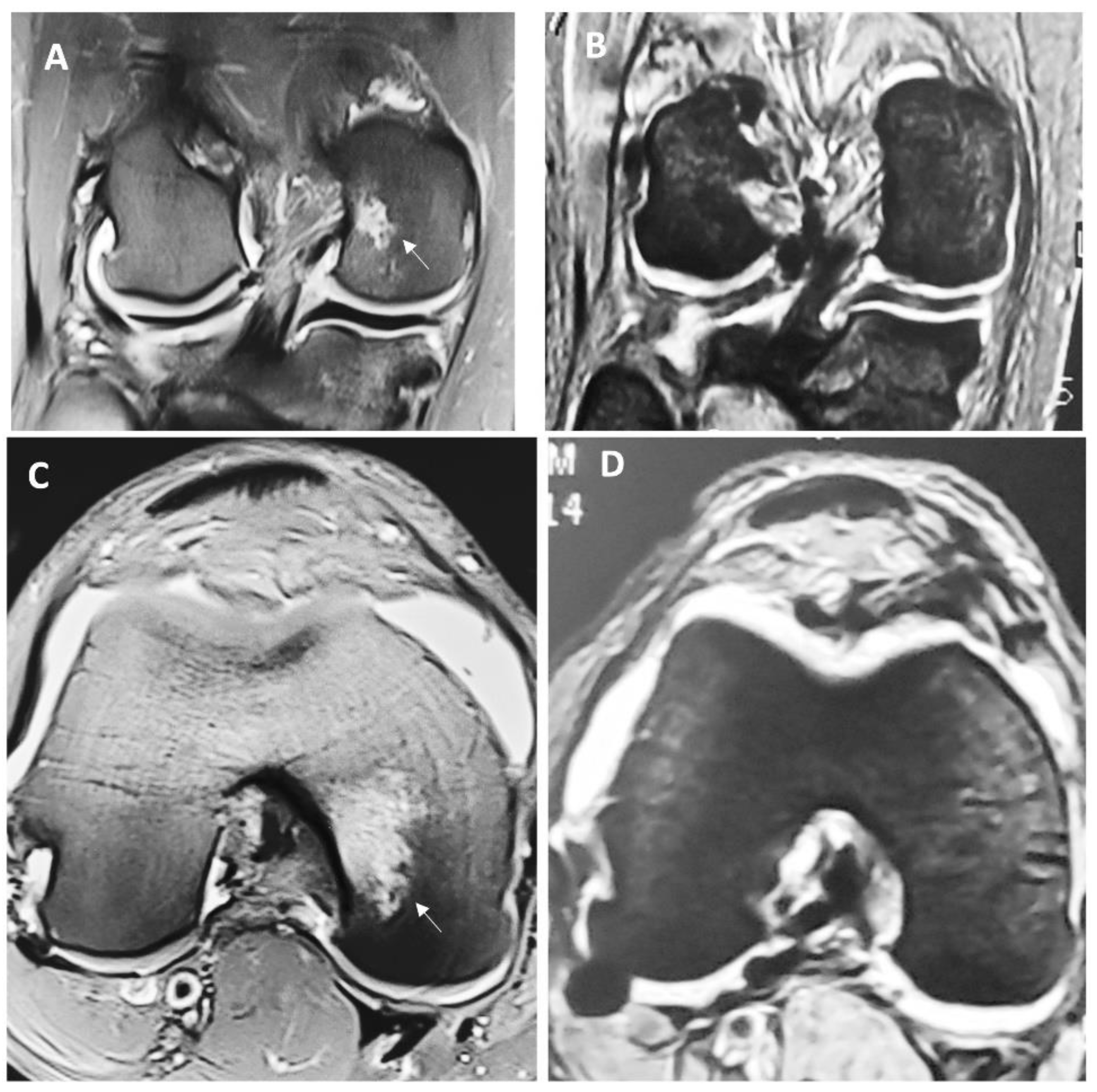

Figure 1 depicts macroscopic changes observed at 6 months in the MRI. Then, at 12 months after the surgery, there was a continued improvement for both groups, but this difference was markedly important for individuals in the HA 3-D scaffold group, since all patients from this group were found to have a Henderson scale of 1, while the group treated with microfractures still had almost half of the individuals (47.6 %) with a score of 2 (

p 0.0048). This means that all patients treated with the HA 3-D scaffold returned to a radiographic image that represents a knee with absence of fluid and edema in the joint. Conversely, in the microfractures group, this was not achieved by any patient.

Table 2 represents these comparisons between groups.

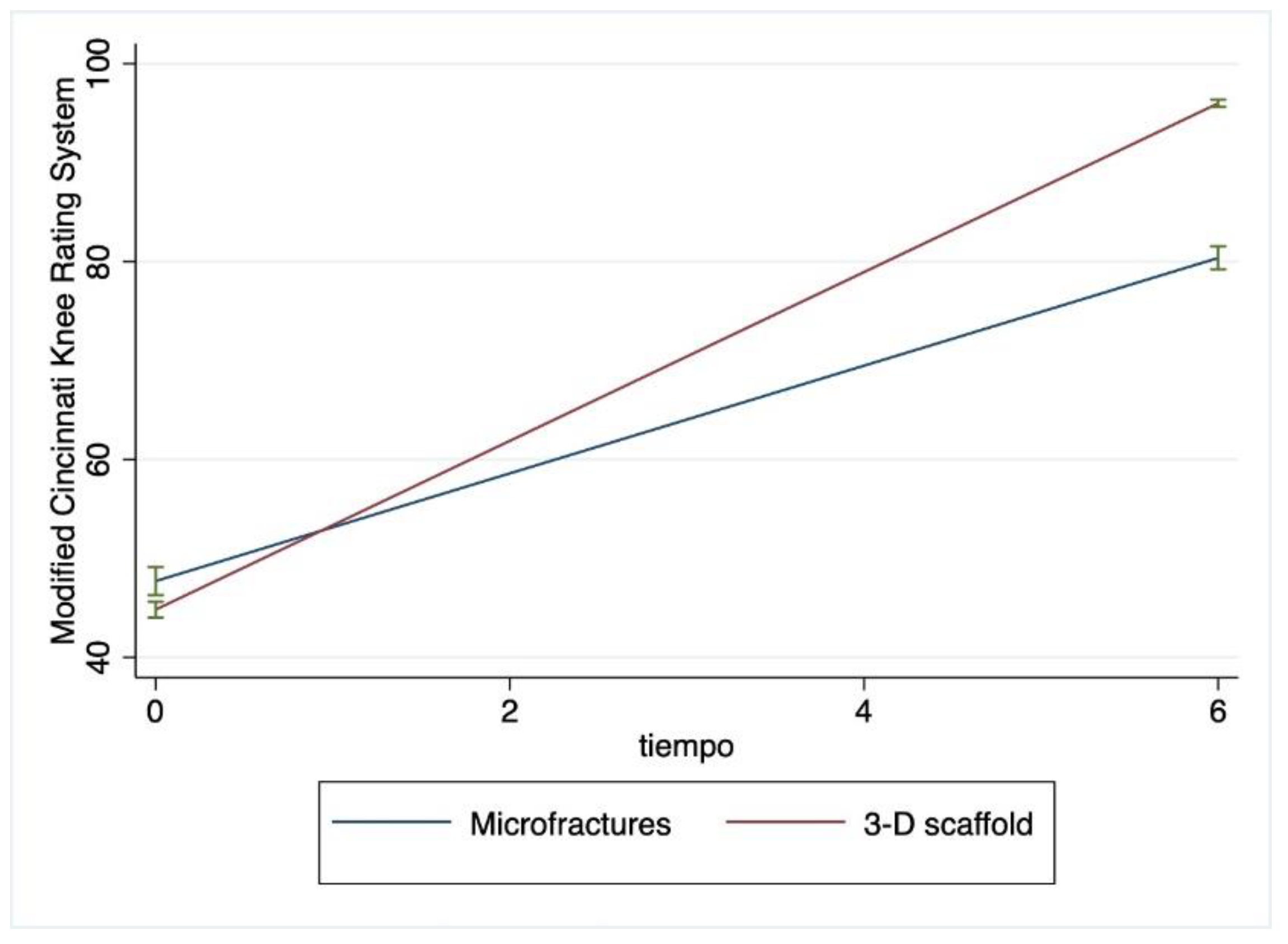

With respect to functionality, patients in the group treated with HA 3-D Scaffold were able to progress to an excellent functionality (>80) in the following 6 months having a near perfect score in the MCKRS, which represents, the capacity to perform physical activity, while in the group treated with microfractures the highest score was related to only a moderate capacity for physical activity.

The mean Henderson and MCKRS scores over time can be observed to change at different rates for patients being treated with two surgical approaches (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

After 12 months of follow-up a small number of patients required a new arthroscopy, during this second look the integrity of the graft was verified to assess the degree of defect, fill, graft integration to adjacent normal articular surface, and gross appearance of the graft surface, we were unable to observe a case without integration to adjacent normal articular tissue (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Our findings support an evident improvement in the group of patients treated with the use of HA 3-D scaffold, seen at 6 months after surgery that progress towards the end of the study at 12 months. According to our findings, the usage of 3-D scaffold for the treatment of cartilage defects is effective and superior to microfractures, with evidence related to less time for total recovery of functional status (MCKRS), and faster improvement in MRI findings (Henderson Score).

Surgical alternatives to treat chondral defects include chondroplasty, microfracture, and osteochondral allograft transplantation [

12]; however chondroplasty and microfractures are options typically performed to treat smaller lesions (<2 cm), larger lesions will frequently require a matrix-induced implantation of cells. Osteochondral transplantation has been frequently used to approach lesions larger than 2 cm or grade III and above, the graft can be obtained from a donor (allograft) or it can be obtained from the same patient (autograft); in the present study, we were able to perform autografts which significantly simplified the procedure since there is no need to perform matching [

13]. Additionally, we had no side effects, related to rejection of the graft.

The autograft used in the present study, came after a bone marrow aspirate from each patients’ femur, which is demonstrated to contain high levels of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), cytokines and chemokines (TGF-b and PDGF) [

14].

Although several studies have aimed in the comparison of results with different therapeutic approaches, most previous clinical trials included patients with isolated or focal midsized defects. However, one previous study with a randomized controlled design found that an aragonite-based scaffold was superior to the microfractures treatment in patients with grade III or superior osteochondral lesions [

15]. They found that up to 78% of patients treated with the scaffold had a significant improvement compared to 34% in the microfractures group (

p<0.0001), after 2 years follow-up [

15]; our study showed an even faster response visible at 6 months after surgery. A faster response and recovery observed in the present study, could be due to the use of a hyaluronic acid based 3-D scaffold. The microstructure, porosity, and addition of supplements to the scaffold have been identified as important characteristics to allow cell fixation, proliferation, differentiation, and further invasion, leading to vascularization and tissue repair. The microstructure needs to provide the required structural strength to support external loads, and the porosity needs to allow the diffusion of nutrients and soluble factors effortlessly through the extent of the scaffold [

16].

The use of a scaffold with hyaluronic acid (HA), has considered to add some important characteristics such as: frictionless movement of the knee and promotion of proliferation of cells in vitro [

17]. Since, it was demonstrated that the presence of HA enhances synovial fluid viscosity and creates a hydrated pathway by which cells can move and migrate [

18]. Furthermore, HA increases chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation and contributes to the inhibition of enzymatic cartilage destruction [

19,

20].

The most frequent complication in surgeries associated to failure of the intervention is colonization with bacteria and the development of an infectious disease, some infectious agents can be multidrug resistant, since they are more commonly found in hospitals, the use of supplements with antibacterial properties could also aim in improving results from surgical interventions [

21].

Some of the limitations in our study are related to the retrospective design, and selection bias could be present. The access to the scaffold by insurance companies, might select patients to have other common attributable variables, that could partially explain a faster recovery, such as increased access to additional resources for clinical improvement, including physiotherapy [

22] or access to new anti-inflammatory drugs or being able to rest for a longer period of time, without the need to return early to work or daily activities [

23]. It has been shown that activity level and knee function after treatment are influenced by preoperative demographic and psychological variables related to the type of insurance they had. We did analyze general demographic variables but not psychosocial factors, which are also related to the functional outcomes after knee surgery, by influencing activity level [

6]. New studies with RCT design could resolve this bias.

5. Conclusions

The use of a HA based 3-D scaffold proved to be superior in the postoperative period, with evidence of total recovery in radiographic (Henderson scale) and functionality (MCKRS) faster when compared to the microfractures technique. Future studies with a RCT design would be useful to address for selection bias, and to learn if this benefit persists over a longer period, especially when subjects normalize their physical activity demand for laboring and performance of physical activity.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection was done by NV, MC and GJJ, analysis was performed by MGZC. The first draft of the manuscript was written by NV, MC, GJJ, and MGZC, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

No additional reports have been made available for the public.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Curl, W.W.; Krome, J.; Gordon, E.S.; Rushing, J.; Smith, B.P.; Poehling, G.G. Cartilage injuries: a review of 31,516 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy 1997, 13, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widuchowski, W.; Widuchowski, J.; Trzaska, T. Articular cartilage defects: study of 25,124 knee arthroscopies. Knee 2007, 14, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guermazi, A.; Hayashi, D.; Roemer, F.W.; Niu, J.; Quinn, E.K.; Crema, M.D.; Nevitt, M.C.; Torner, J.; Lewis, C.E.; Felson, D.T. Brief Report: Partial- and Full-Thickness Focal Cartilage Defects Contribute Equally to Development of New Cartilage Damage in Knee Osteoarthritis: The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017, 69, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, D.; Calvo, R.; Vaisman, A.; Carrasco, M.A.; Moraga, C.; Delgado, I. Knee chondral lesions: incidence and correlation between arthroscopic and magnetic resonance findings. Arthroscopy 2007, 23, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophia Fox, A.J.; Bedi, A.; Rodeo, S.A. The basic science of articular cartilage: structure, composition, and function. Sports Health 2009, 1, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, T.; Roberts, S.; Richardson, J.B.; Gallacher, P.; Bailey, A.; Kuiper, J.H. Relationship Between Activity Level and Knee Function Is Influenced by Negative Affect in Patients Undergoing Cell Therapy for Articular Cartilage Defects in the Knee. Orthop J Sports Med 2023, 11, 23259671231151925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldring, M.B.; Marcu, K.B. Cartilage homeostasis in health and rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther 2009, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knutsen, G.; Drogset, J.O.; Engebretsen, L.; Grontvedt, T.; Ludvigsen, T.C.; Loken, S.; Solheim, E.; Strand, T.; Johansen, O. A Randomized Multicenter Trial Comparing Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation with Microfracture: Long-Term Follow-up at 14 to 15 Years. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016, 98, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, E.; Gobbi, A.; Filardo, G.; Delcogliano, M.; Zaffagnini, S.; Marcacci, M. Arthroscopic second-generation autologous chondrocyte implantation compared with microfracture for chondral lesions of the knee: prospective nonrandomized study at 5 years. Am J Sports Med 2009, 37, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.G.; Jones, E.C.; Allen, A.A.; Altchek, D.W.; O'Brien, S.J.; Rodeo, S.A.; Williams, R.J.; Warren, R.F.; Wickiewicz, T.L. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of four knee outcome scales for athletic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001, 83, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, I.; Francisco, R.; Oakes, B.; Cameron, J. Autologous chondrocyte implantation for treatment of focal chondral defects of the knee--a clinical, arthroscopic, MRI and histologic evaluation at 2 years. Knee 2005, 12, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, F.; Harris, J.D.; Abrams, G.D.; Frank, R.; Gupta, A.; Hussey, K.; Wilson, H.; Bach, B., Jr.; Cole, B. Trends in the surgical treatment of articular cartilage lesions in the United States: an analysis of a large private-payer database over a period of 8 years. Arthroscopy 2014, 30, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrity, J.T.; Stoker, A.M.; Sims, H.J.; Cook, J.L. Improved osteochondral allograft preservation using serum-free media at body temperature. Am J Sports Med 2012, 40, 2542–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Themistocleous, G.S.; Chloros, G.D.; Kyrantzoulis, I.M.; Georgokostas, I.A.; Themistocleous, M.S.; Papagelopoulos, P.J.; Savvidou, O.D. Effectiveness of a single intra-articular bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) injection in patients with grade 3 and 4 knee osteoarthritis. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschuler, N.; Zaslav, K.R.; Di Matteo, B.; Sherman, S.L.; Gomoll, A.H.; Hacker, S.A.; Verdonk, P.; Dulic, O.; Patrascu, J.M.; Levy, A.S.; et al. Aragonite-Based Scaffold Versus Microfractures and Debridement for the Treatment of Knee Chondral and Osteochondral Lesions: Results of a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Sports Med 2023, 3635465231151252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Orozco, Y.; Betancur, A.; Moreno, A.I.; Fuentes, K.; Lopera, A.; Suarez, O.; Lobo, T.; Ossa, A.; Pelaez-Vargas, A.; et al. Fabrication of polycaprolactone/calcium phosphates hybrid scaffolds impregnated with plant extracts using 3D printing for potential bone regeneration. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freymann, U.; Endres, M.; Neumann, K.; Scholman, H.J.; Morawietz, L.; Kaps, C. Expanded human meniscus-derived cells in 3-D polymer-hyaluronan scaffolds for meniscus repair. Acta Biomater 2012, 8, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockmeier, S.F.; Shaffer, B.S. Viscosupplementation therapy for osteoarthritis. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2006, 14, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagishita, K.; Sekiya, I.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Shinomiya, K.; Muneta, T. The effect of hyaluronan on tendon healing in rabbits. Arthroscopy 2005, 21, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, D.J.; Byrne, C.A.; Alkhayat, A.; Eustace, S.J.; Kavanagh, E.C. Injectable Viscoelastic Supplements: A Review for Radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017, 209, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduga, M.B.; Bobinski, R.; Dutka, M.; Ulman-Wlodarz, I.; Bujok, J.; Pajak, C.; Cwiertnia, M.; Kurowska, A.; Dziadek, M.; Rajzer, I. Analysis of the antibacterial properties of polycaprolactone modified with graphene, bioglass and zinc-doped bioglass. Acta Bioeng Biomech 2021, 23, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toonstra, J.L.; Howard, J.S.; Uhl, T.L.; English, R.A.; Mattacola, C.G. The role of rehabilitation following autologous chondrocyte implantation: a retrospective chart review. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2013, 8, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ebert, J.R.; Smith, A.; Edwards, P.K.; Hambly, K.; Wood, D.J.; Ackland, T.R. Factors predictive of outcome 5 years after matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation in the tibiofemoral joint. Am J Sports Med 2013, 41, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).