Submitted:

30 August 2023

Posted:

04 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Sampling and Microorganisms isolation

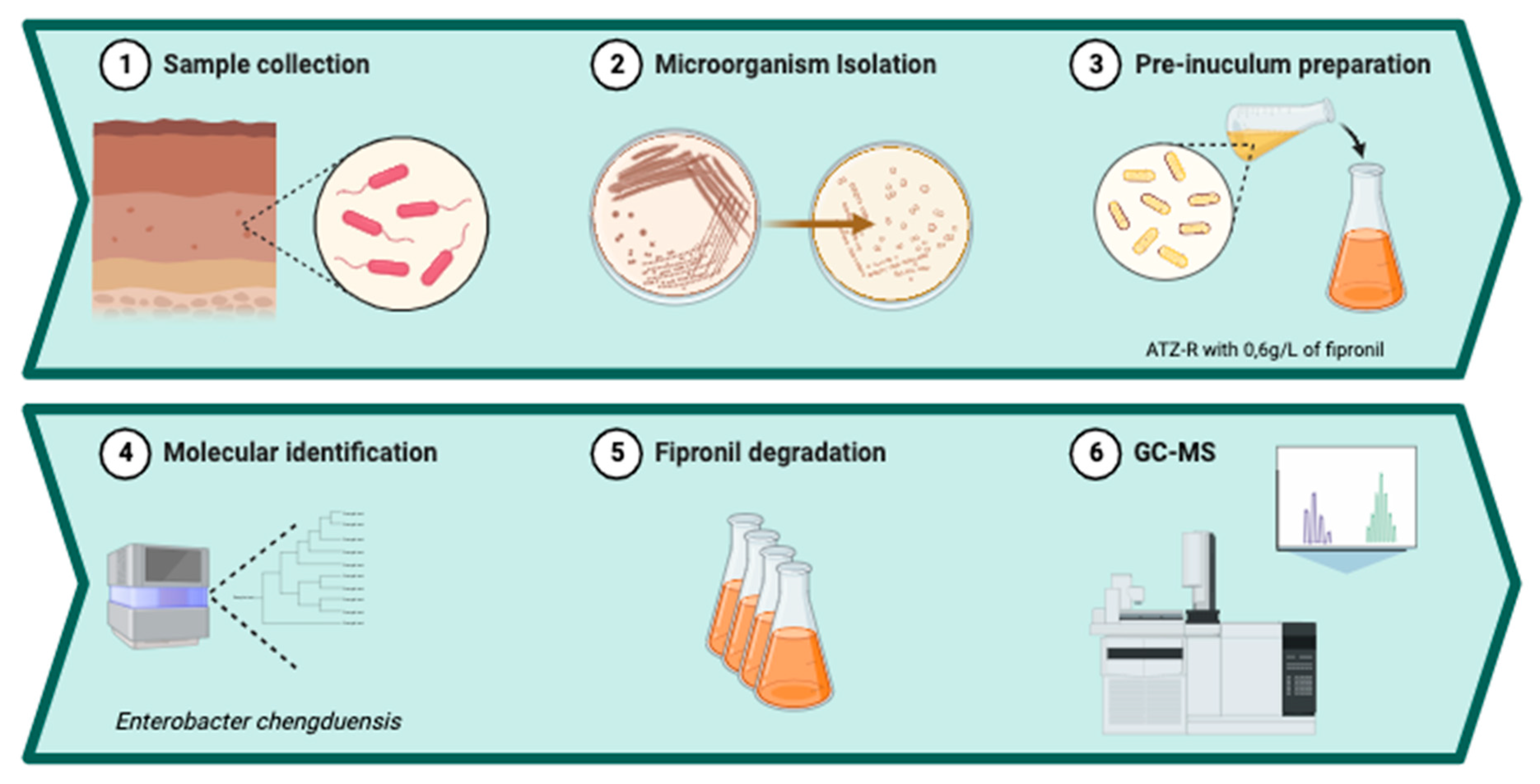

2.2. Molecular Identification of Strain and phylogenetic tree

2.3. Pre-inoculum preparation

2.4. Fipronil Degradation

2.5. GC-MS conditions and analysis of fipronil biodegradation and metabolites quantification

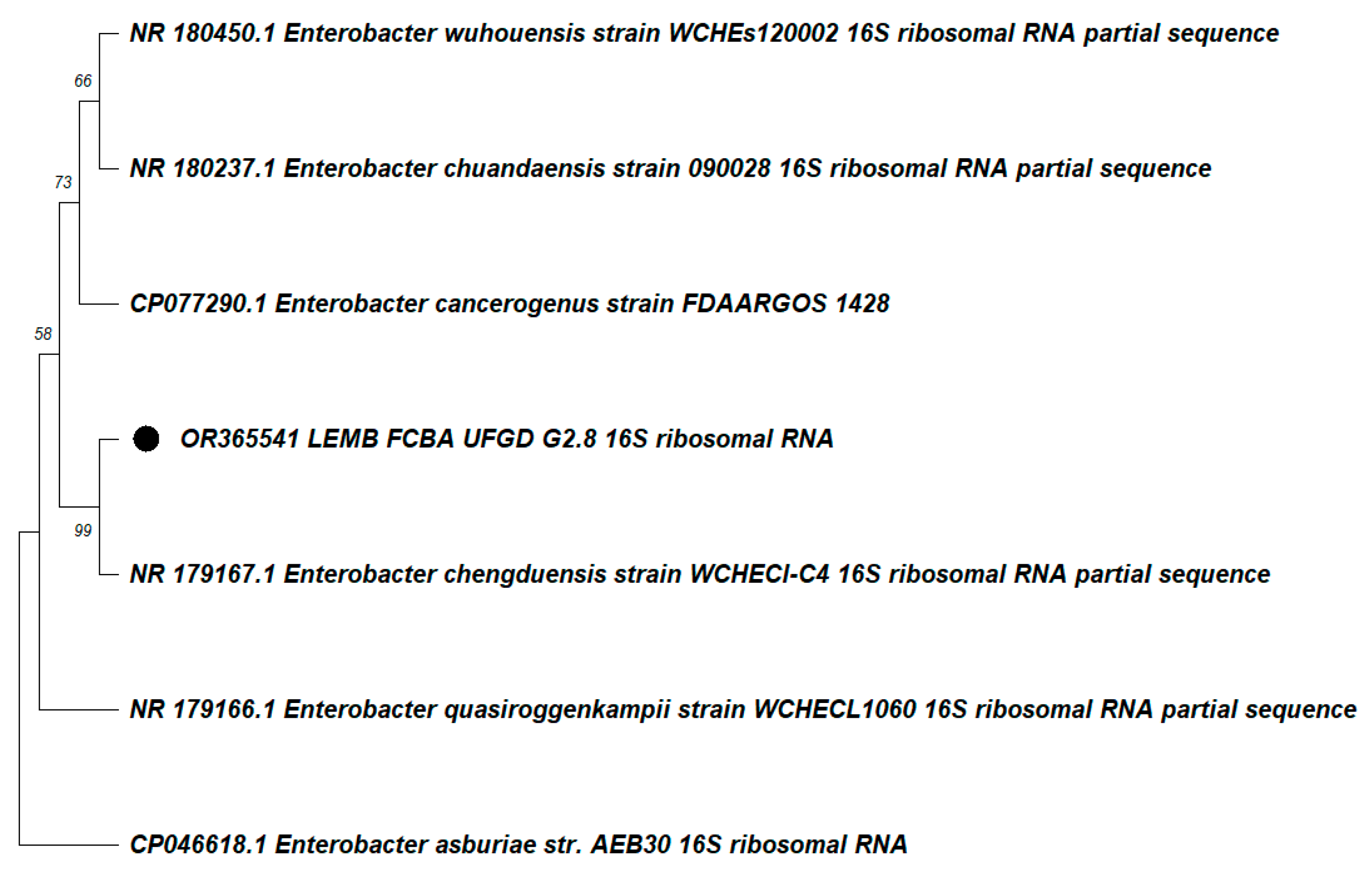

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation and molecular identification

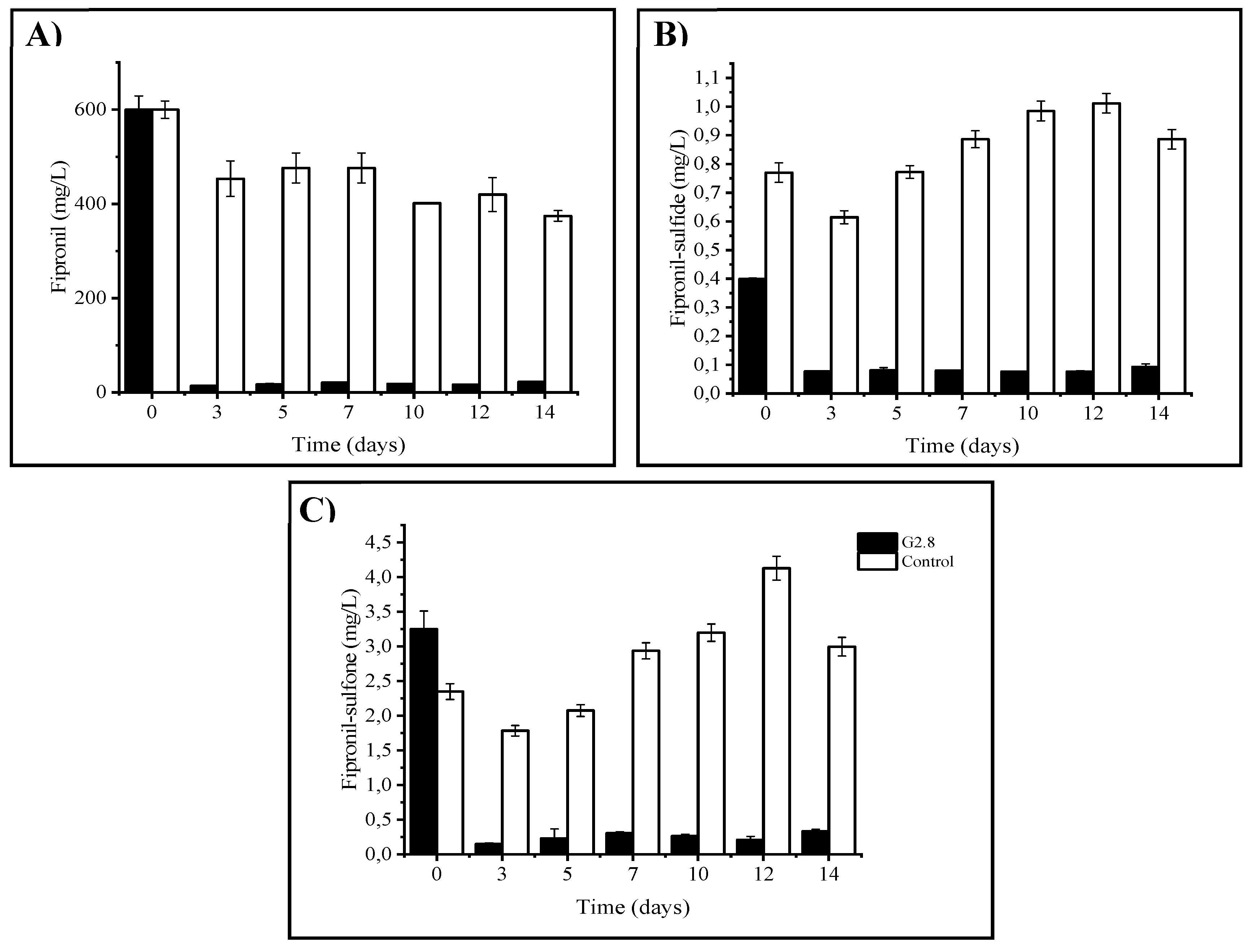

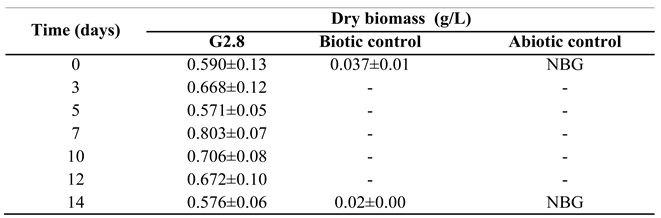

3.1. Fipronil degradation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonfá, M.R.L.; do Prado, C.C.A.; Piubeli, F.A.; Durrant, L.R. Fipronil Microbial Degradation: An Overview From Bioremediation to Metabolic Pathways. In Pesticides Bioremediation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 81–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, P.; Gangola, S.; Ramola, S.; Bilal, M.; Bhatt, K.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, S. Insights into the Toxicity and Biodegradation of Fipronil in Contaminated Environment. Microbiol Res 2023, 266, 127247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, J.G.; Birolli, W.G.; Porto, A.L.M. Biodegradation of the Pesticides Bifenthrin and Fipronil by Bacillus Isolated from Orange Leaves. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2023, 195, 3295–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.Y.; Lim, J.W.; Lim, M.C.; Song, N.E.; Woo, M.A. Aptamer-Based Fluorescent Assay for Simple and Sensitive Detection of Fipronil in Liquid Eggs. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering 2020, 25, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangola, S.; Sharma, A.; Joshi, S.; Bhandari, G.; Prakash, O.; Govarthanan, M.; Kim, W.; Bhatt, P. Novel Mechanism and Degradation Kinetics of Pesticides Mixture Using Bacillus Sp. Strain 3C in Contaminated Sites. Pestic Biochem Physiol 2022, 181, 104996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, C.C.A. do; Pereira, R.M.; Durrant, L.R.; Júnior, R.P.S.; Bonfá, M.R.L. Fipronil Biodegradation and Metabolization by Bacillus Megaterium Strain E1. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.; Satyanarayana, G.N.V.; Patel, D.K.; Satish, A. Bioaccumulation, Biotransformation and Toxic Effect of Fipronil in Escherichia Coli. Chemosphere 2019, 231, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Park, S.; Song, G.; Lim, W. Developmental Toxicity of Fipronil in Early Development of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Larvae: Disrupted Vascular Formation with Angiogenic Failure and Inhibited Neurogenesis. J Hazard Mater 2020, 385, 121531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Otín, M.R.; Ballestero, D.; Navarro, E.; Mainar, A.M.; Val, J. Effects of the Insecticide Fipronil in Freshwater Model Organisms and Microbial and Periphyton Communities. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, H.R.; Pestana, J.L.T.; Novais, S.C.; Leston, S.; Ramos, F.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Devreese, B.; Lemos, M.F.L. Assessment of Fipronil Toxicity to the Freshwater Midge Chironomus Riparius: Molecular, Biochemical, and Organismal Responses. Aquatic Toxicology 2019, 216, 105292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Murr, A. elhakeem I.; Abd El Hakim, Y.; Neamat-Allah, A.N.F.; Baeshen, M.; Ali, H.A. Immune-Protective, Antioxidant and Relative Genes Expression Impacts of β-Glucan against Fipronil Toxicity in Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis Niloticus. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2019, 94, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldaniya, D.M.; Singh, S.; Saini, L.K.; Gandhi, K.D. Persistence and Dissipation Behaviour of Fipronil and Its Metabolites in Sugarcane Grown Soil of South Gujarat. Int J Chem Stud 2020, 8, 1524–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniyal, S.; Paliwal, R.; Sharma, R.K.; Rai, J.P.N. Degradation of Fipronil by Stenotrophomonas Acidaminiphila Isolated from Rhizospheric Soil of Zea Mays. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.; Wu, H.; Guo, J.; Kimaro, F.M.E. Microbial Degradation of Fipronil in Clay Loam Soil. Water Air Soil Pollut 2004, 153, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Sharma, A.; Rene, E.R.; Jagadeesh, A.; Zhang, W.; Chen, S. Bioremediation of Fipronil Using Bacillus Sp. FA3 : Mechanism, Kinetics and Resource Recovery Potential from Contaminated Environments. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2021, 39, 101712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 16S Ribosomal DNA Amplification for Phylogenetic Study. J Bacteriol 1991, 173, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, D.A.; Karsch-mizrachi, I.; Lipman, D.J.; Ostell, J.; Rapp, B.A.; Wheeler, D.L. GenBank. 2000, 28, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The Neighbor-Joining Method: A New Method for Reconstructing Phylogenetic Trees. Mol Biol Evol 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, K.; Singh, B.; Jariyal, M.; Gupta, V.K. Bioremediation of Fipronil by a Bacillus Firmus Isolate from Soil. Chemosphere 2014, 101, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wu, X.; Lin, Z.; Pang, S.; Mishra, S.; Chen, S. Biodegradation of Fipronil: Current State of Mechanisms of Biodegradation and Future Perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 105, 7695–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uniyal, S.; Paliwal, R.; Sharma, R.K.; Rai, J.P.N. Degradation of Fipronil by Stenotrophomonas Acidaminiphila Isolated from Rhizospheric Soil of Zea Mays. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizaquível, P.; Pérez-Cataluña, A.; Yépez, A.; Aristimuño, C.; Jiménez, E.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Vignolo, G.; Aznar, R. Pyrosequencing vs. Culture-Dependent Approaches to Analyze Lactic Acid Bacteria Associated to Chicha, a Traditional Maize-Based Fermented Beverage from Northwestern Argentina. Int J Food Microbiol 2015, 198, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guima, S.E.S.; Piubeli, F.; Bonfá, M.R.L.; Pereira, R.M. New Insights into the Effect of Fipronil on the Soil Bacterial Community. Microorganisms 2022, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelini, L.T.D.; Alberice, J.A.; Eugênio, P.F.M.; Pozzi, E.; Urbaczek, A.C.; Diniz, L.G.R.; Carrilho, E.N.V.M.; Carrilho, E.; Vieira, E.M. Burkholderia Thailandensis: The Main Bacteria Biodegrading Fipronil in Fertilized Soil with Assessment by a QuEChERS/GC-MS Method. J. Braz. Chem. Soc 2018, 29, 1934–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, B.; Gupta, V.K. Biodegradation of Fipronil by Paracoccus Sp. in Different Types of Soil. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 2012, 88, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaniar, K.R.; Tazkiaturrizki, T.; Rinanti, A. Fipronil Removal at Various Temperature and Pollutant Concentration by Using Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Brevibacterium Sp. in Liquid Media. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2021, 1098, 052071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skariyachan, S.; Taskeen, N.; Kishore, A.P.; Krishna, B.V.; Naidu, G. Novel Consortia of Enterobacter and Pseudomonas Formulated from Cow Dung Exhibited Enhanced Biodegradation of Polyethylene and Polypropylene. J Environ Manage 2021, 284, 112030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J.; Silambarasan, S. Biomineralization and Formulation of Endosulfan Degrading Bacterial and Fungal Consortiums. Pestic Biochem Physiol 2014, 116, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangaraj, S.; Bankole, P.O.; Sadasivam, S.K. Microbial Degradation of Azo Dyes by Textile Effluent Adapted, Enterobacter Hormaechei under Microaerophilic Condition. Microbiol Res 2021, 250, 126805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Feng, Y.; Zong, Z. Characterization of a Strain Representing a New Enterobacter Species, Enterobacter Chengduensis Sp. Nov. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2019, 112, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wei, L.; Feng, Y.; Kang, M.; Zong, Z. Enterobacter Huaxiensis Sp. Nov. and Enterobacter Chuandaensis Sp. Nov., Recovered from Human Blood. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2019, 69, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Dong, C.; Wang, S.; Danso, B.; Dar, M.A.; Pandit, R.S.; Pawar, K.D.; Geng, A.; Zhu, D.; Li, X.; et al. Host-Specific Diversity of Culturable Bacteria in the Gut Systems of Fungus-Growing Termites and Their Potential Functions towards Lignocellulose Bioconversion. Insects 2023, 14, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.X.F.; Drigo, B.; Doolette, C.L.; Vasileiadis, S.; Donner, E.; Karpouzas, D.G.; Lombi, E. Repeated Applications of Fipronil, Propyzamide and Flutriafol Affect Soil Microbial Functions and Community Composition: A Laboratory-to-Field Assessment. Chemosphere 2023, 331, 138850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomazini, R.; Saia, F.T.; van der Zaan, B.; Grosseli, G.M.; Fadini, P.S.; de Oliveira, R.G.M.; Gregoracci, G.B.; Mozetto, A.; van Vugt-Lussenburg, B.M.A.; Brouwer, A.; et al. Biodegradation of Fipronil: Transformation Products, Microbial Characterisation and Toxicity Assessment. Water Air Soil Pollut 2021, 232, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangola, S.; Bhatt, P.; Kumar, A.J.; Bhandari, G.; Joshi, S.; Punetha, A.; Bhatt, K.; Rene, E.R. Biotechnological Tools to Elucidate the Mechanism of Pesticide Degradation in the Environment. Chemosphere 2022, 296, 133916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, J.; Gajendiran, A. Biodegradation of Fi Pronil and Its Metabolite Fi Pronil Sulfone by Streptomyces Rochei Strain AJAG7 and Its Use in Bioremediation of Contaminated Soil. Pestic Biochem Physiol 2019, 155, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfand, J.; Lefevre, G.; Luthy, R. Metabolization and Degradation Kinetics of the Urban-Use Pesticide Fipronil by White Rot Fungus: Trametes Versicolor. Environ Sci Process Impacts 2016, 18, 1256–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendiran, A.; Abraham, J. Biomineralisation of Fipronil and Its Major Metabolite, Fipronil Sulfone, by Aspergillus Glaucus Strain AJAG1 with Enzymes Studies and Bioformulation. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girvan, H.M.; Munro, A.W. Applications of Microbial Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Biotechnology and Synthetic Biology. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2016, 31, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wu, X.; Lin, Z.; Pang, S.; Mishra, S.; Chen, S. Biodegradation of Fipronil: Current State of Mechanisms of Biodegradation and Future Perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 105, 7695–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).