Submitted:

25 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

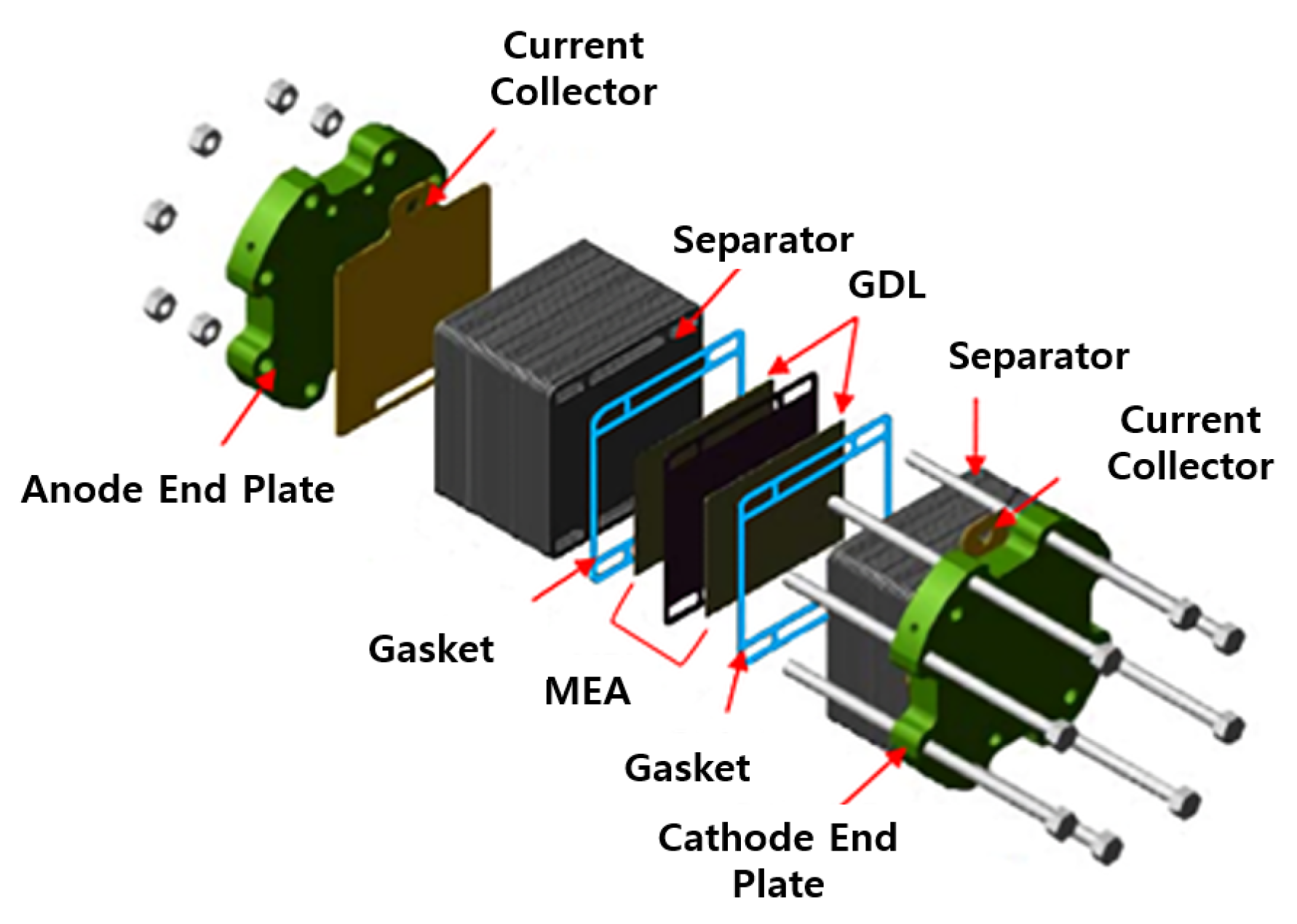

1. Introduction

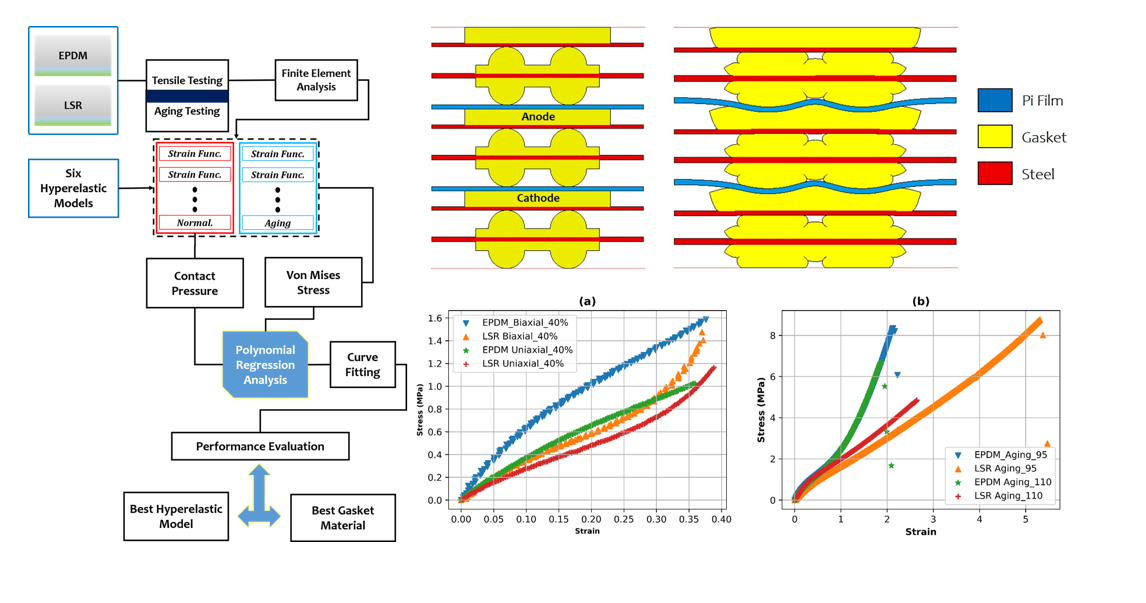

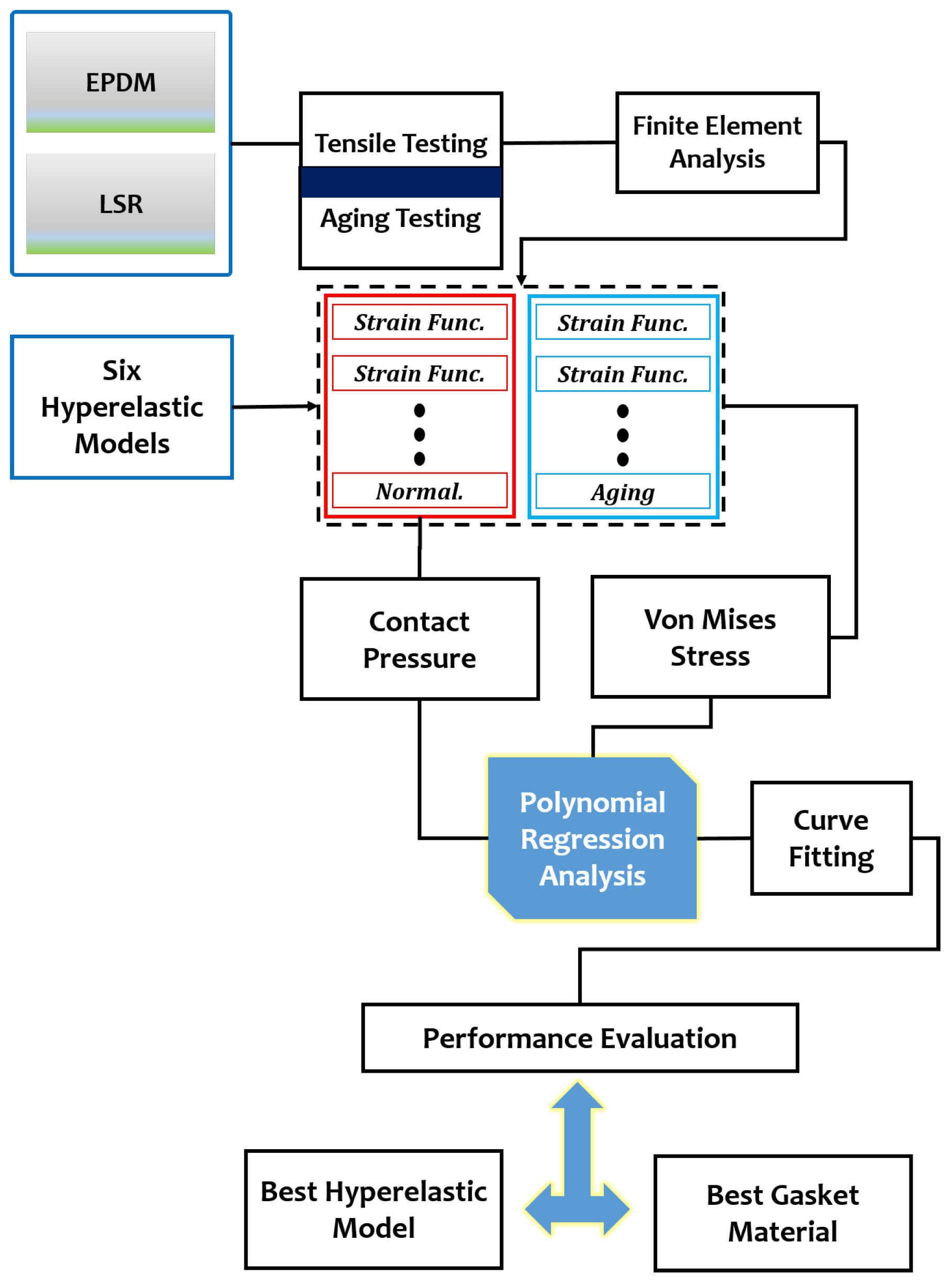

- The study addresses the research gap by providing a comprehensive and direct comparison between two widely used gasket materials, LSR and EPDM, specifically in PEMFC applications.

- The study generates experimental data for LSR and EPDM gasket materials under varying contact pressures representative of real-world PEMFC operating conditions. This experimental data is essential for validating the subsequent Finite Element Analysis (FEA) models and enhancing the accuracy and reliability of the study’s findings.

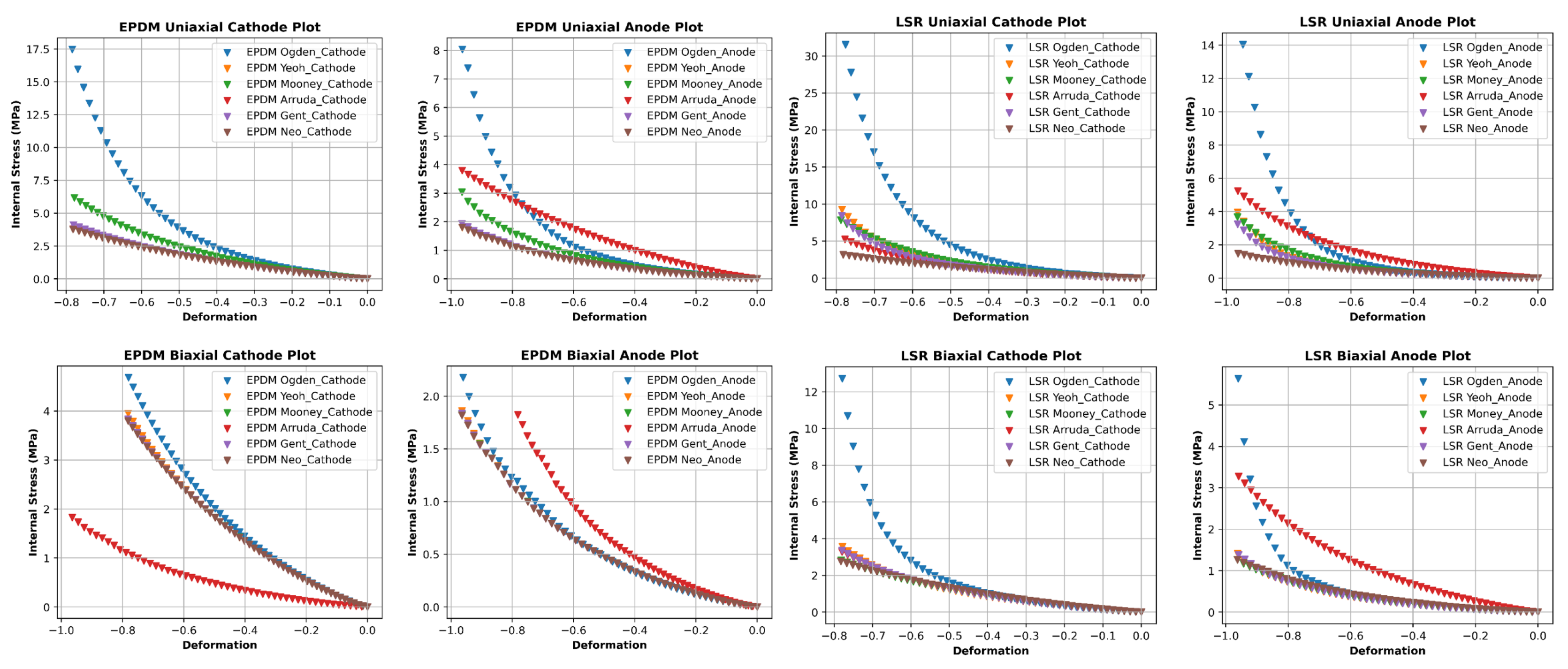

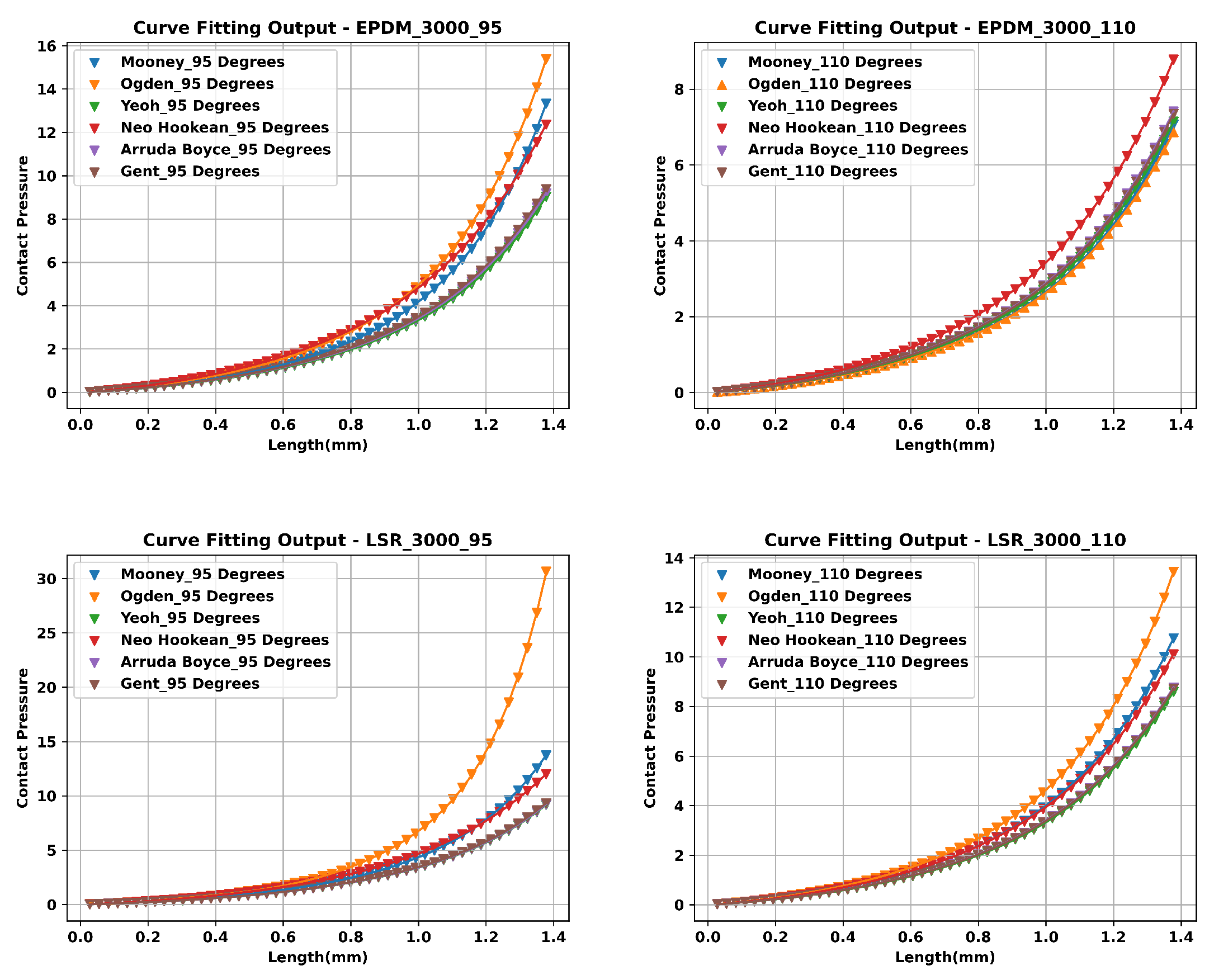

- By employing advanced Finite Element Analysis using the Marc software, the study extracts strain functions for both LSR and EPDM gaskets. This approach is significant as it enables researchers to understand how each material responds to different contact pressures, providing valuable information on their mechanical behaviour and deformation characteristics.

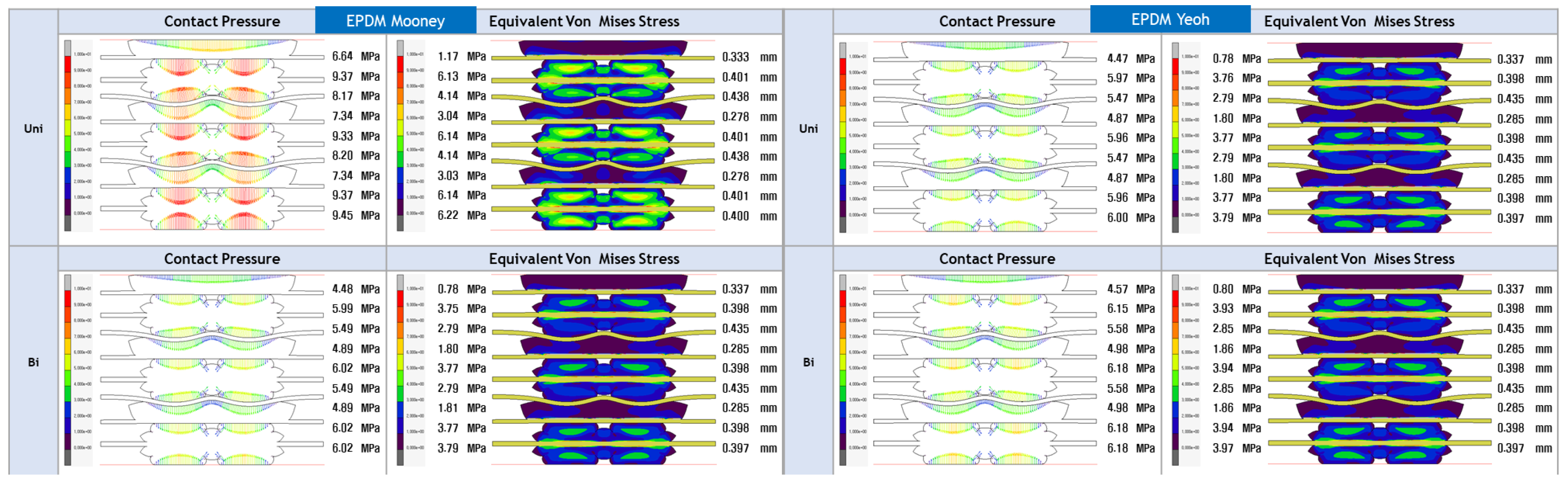

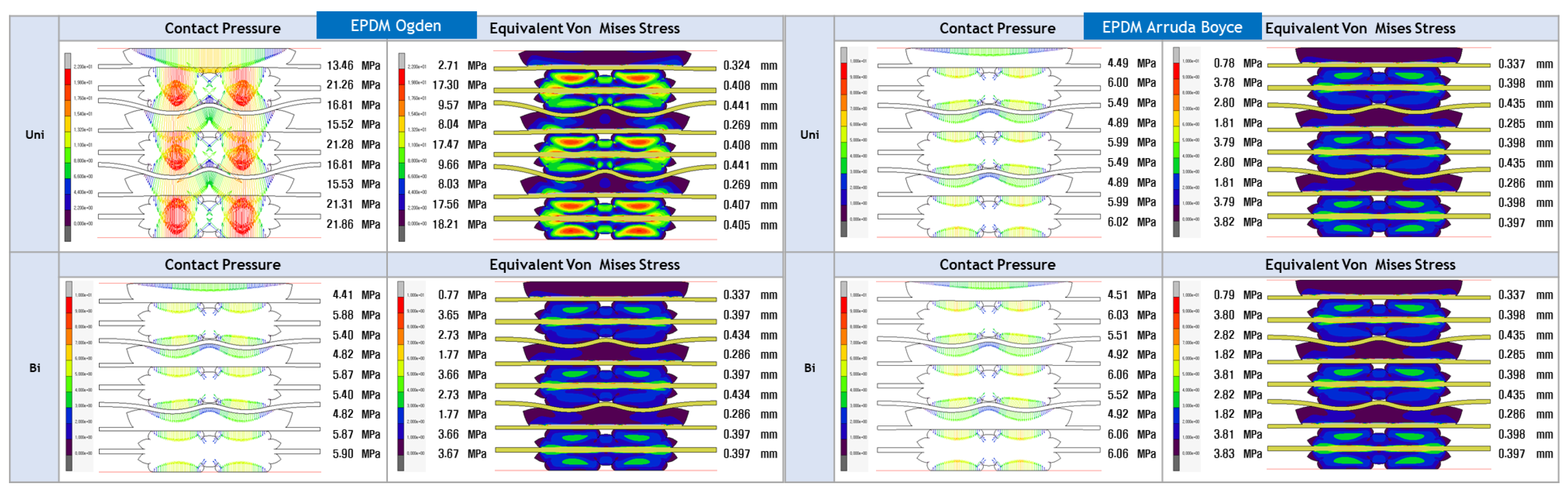

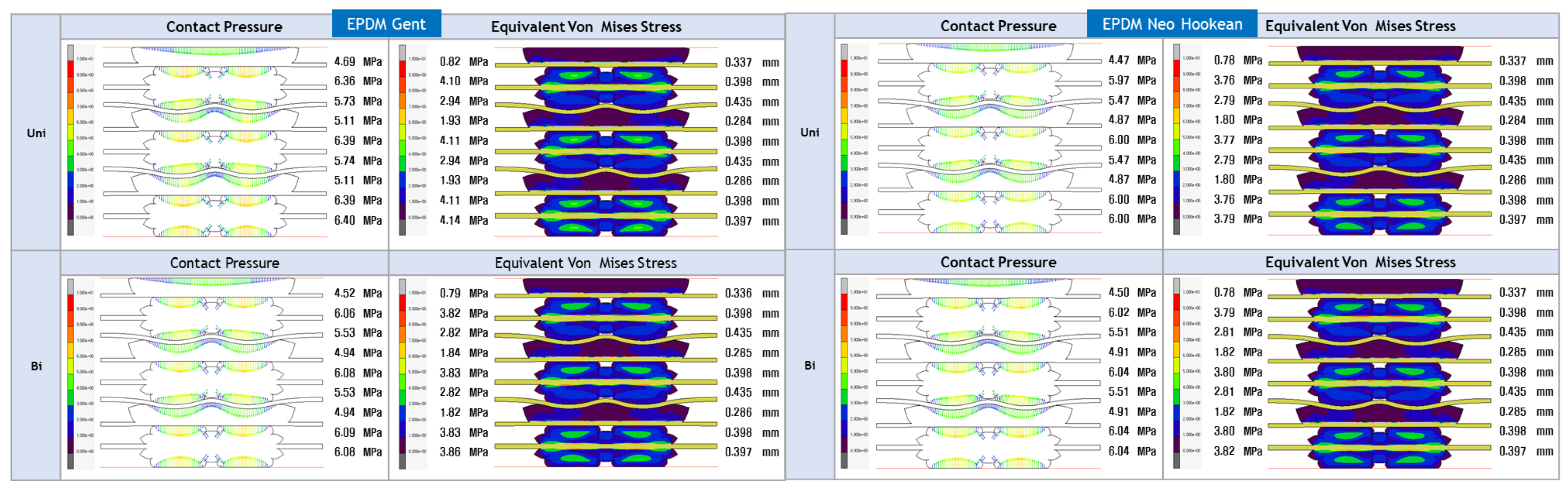

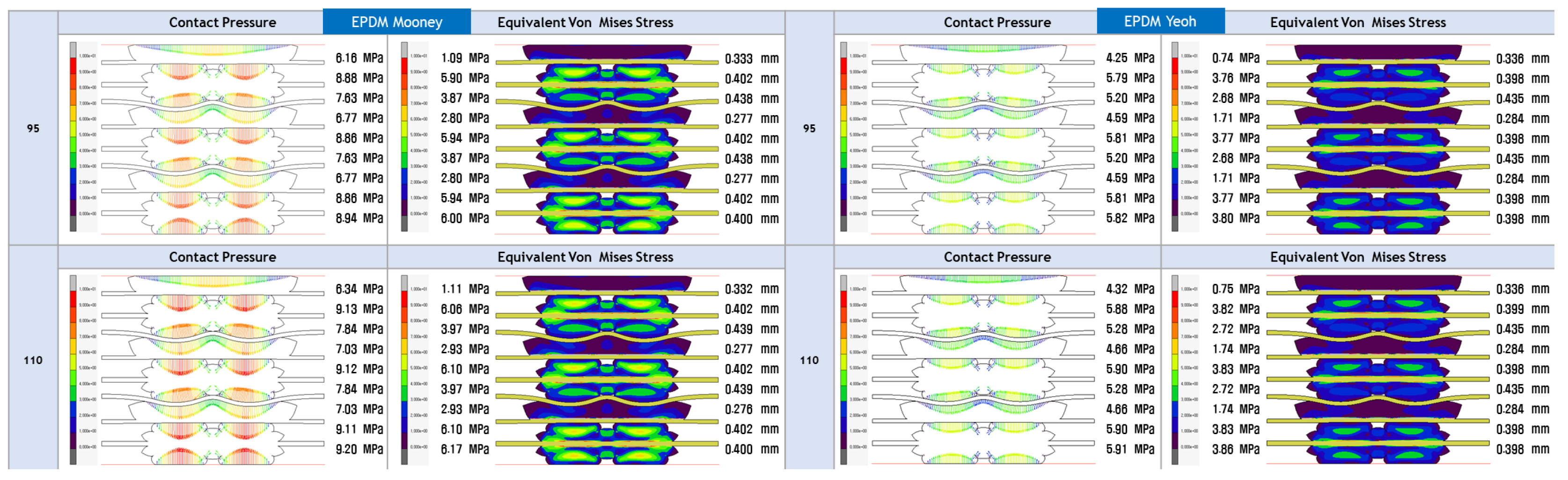

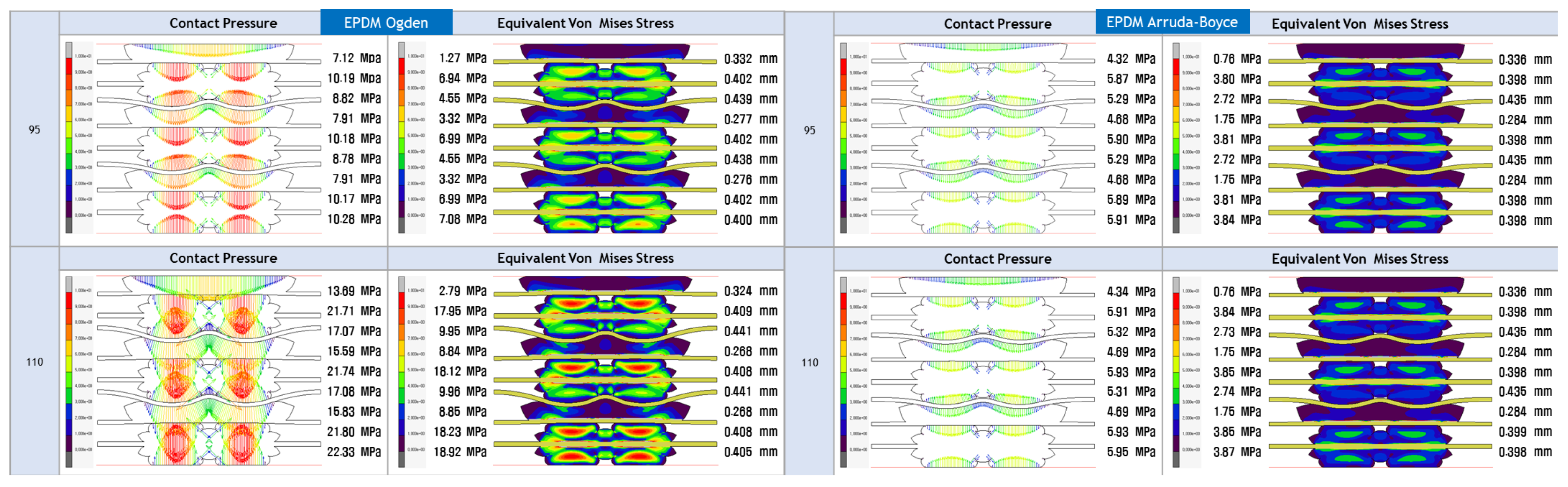

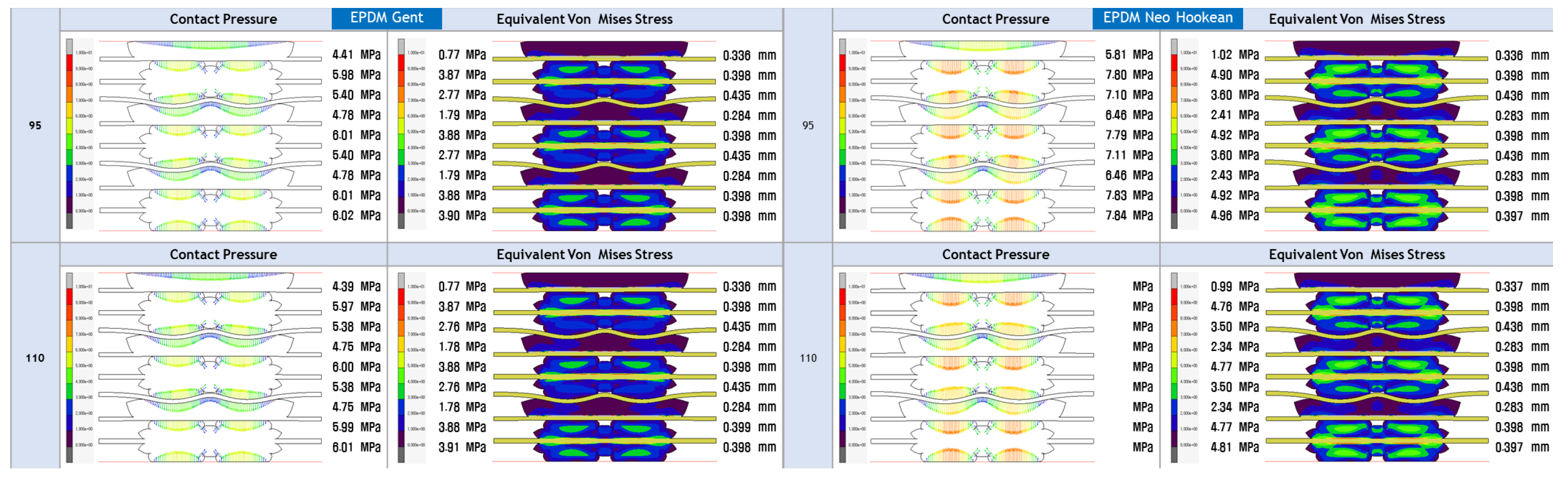

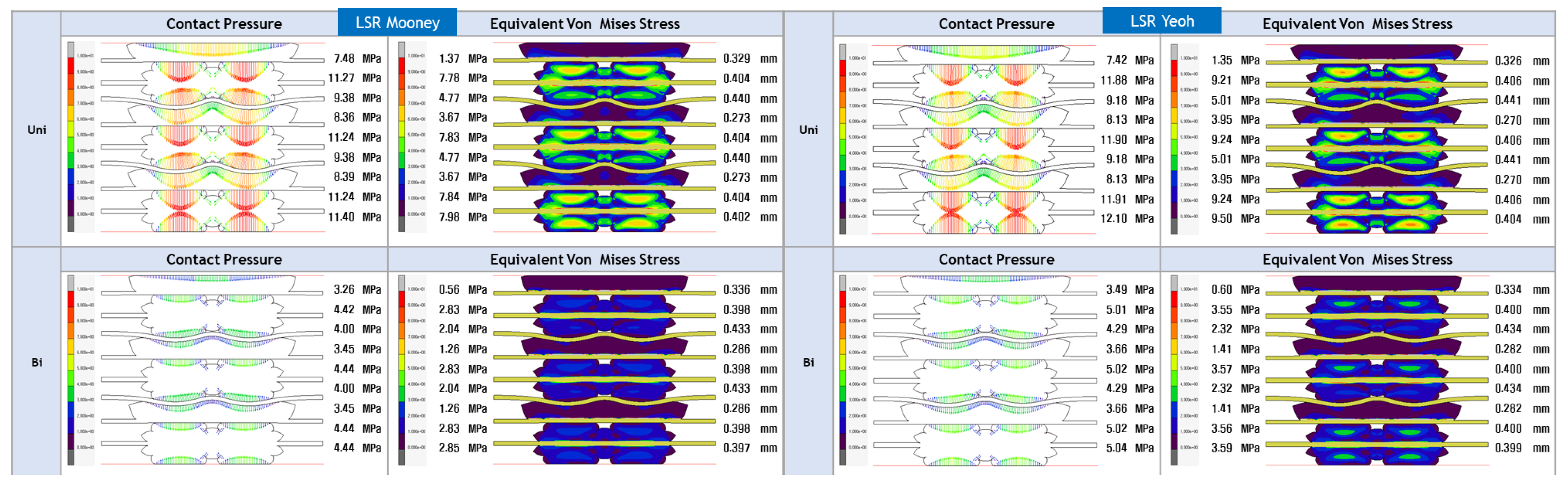

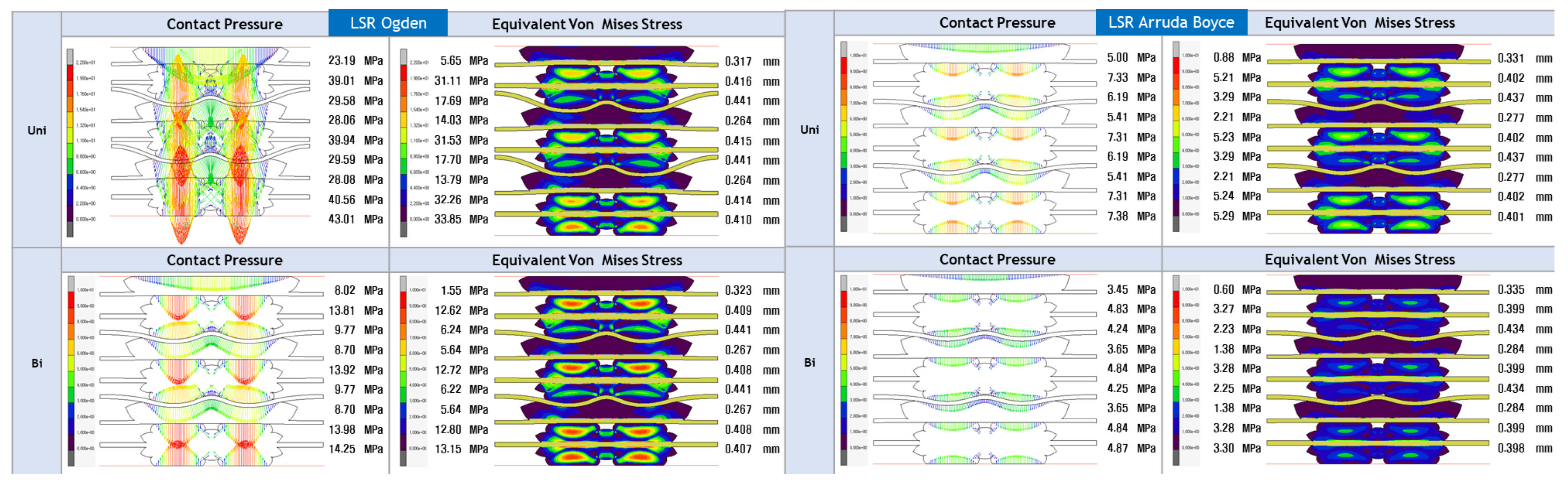

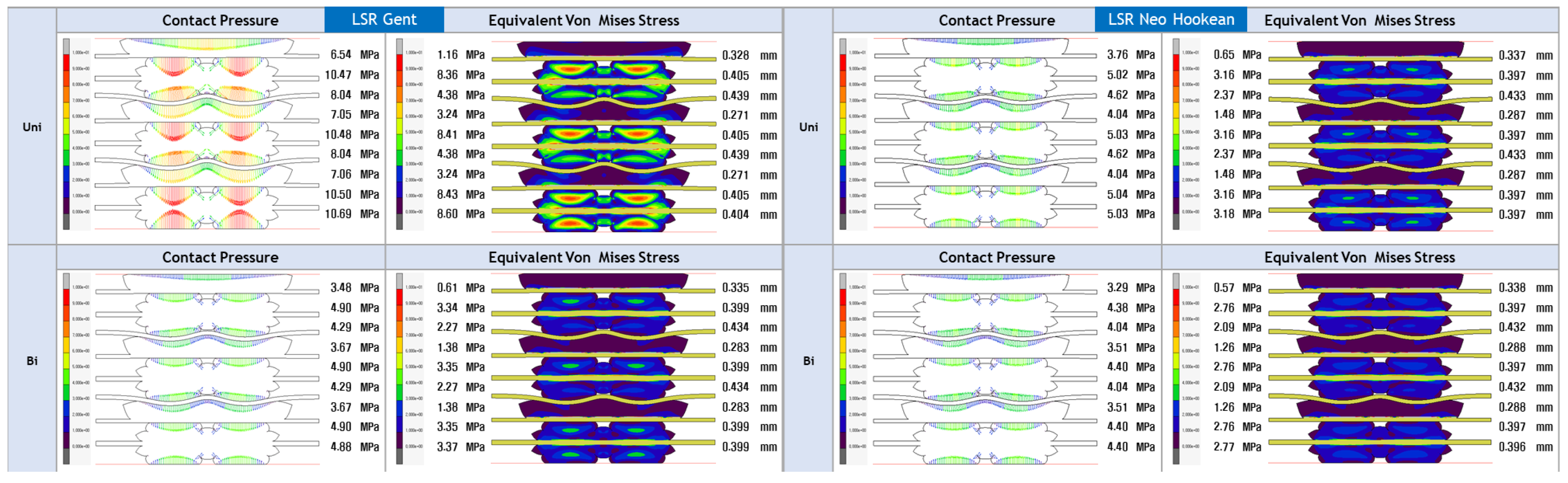

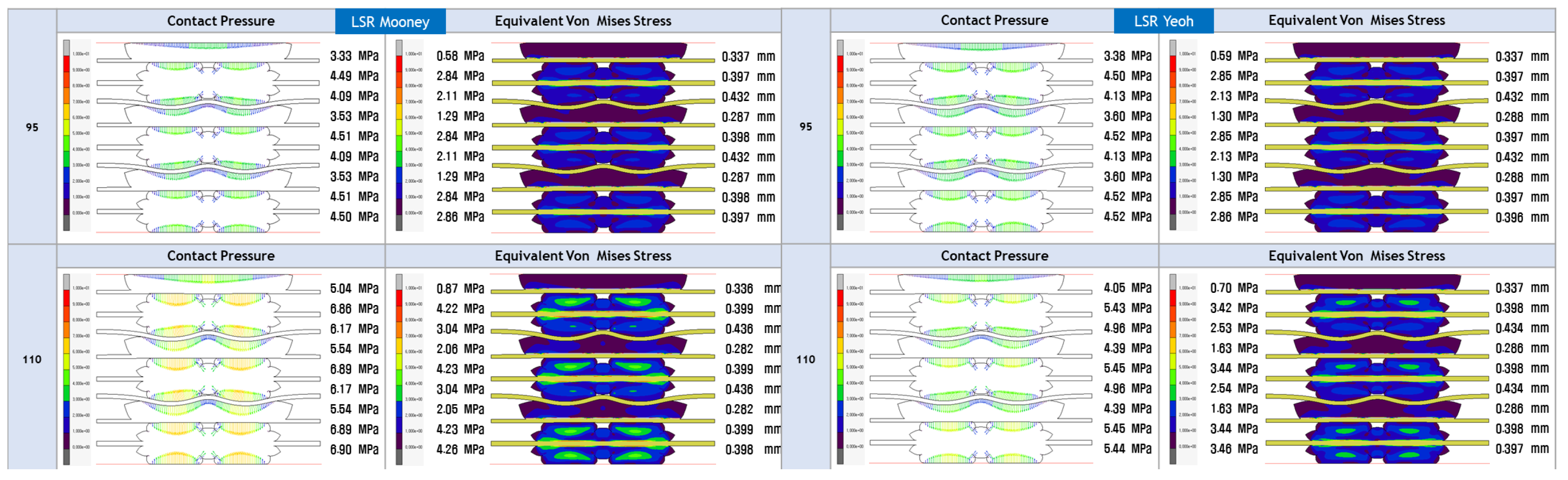

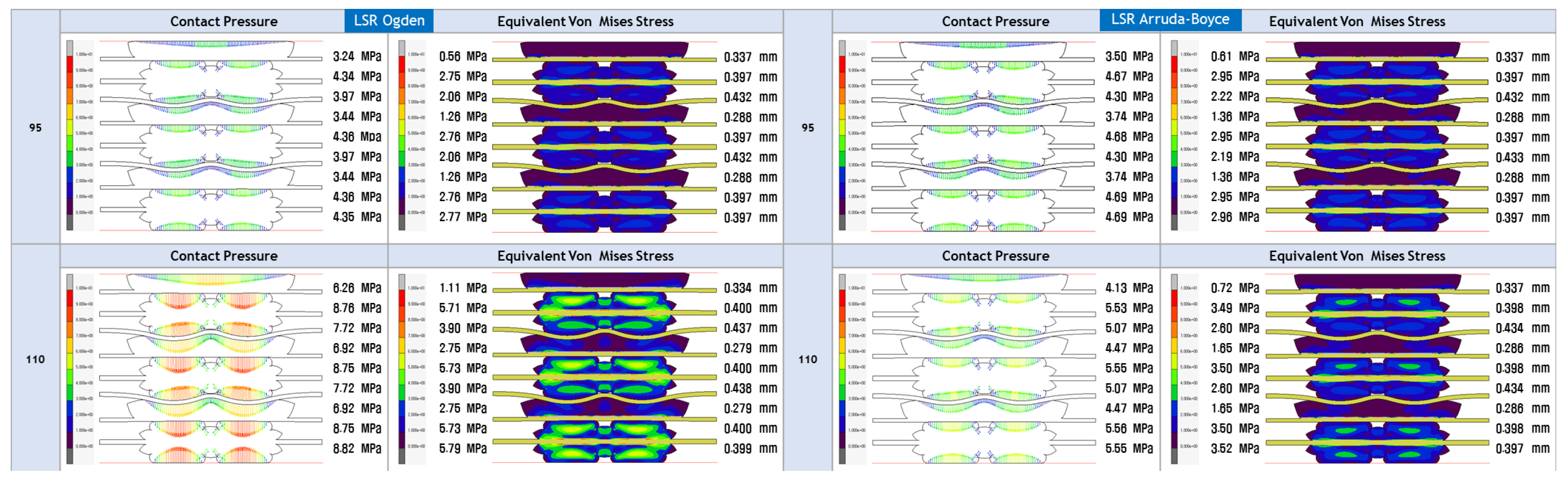

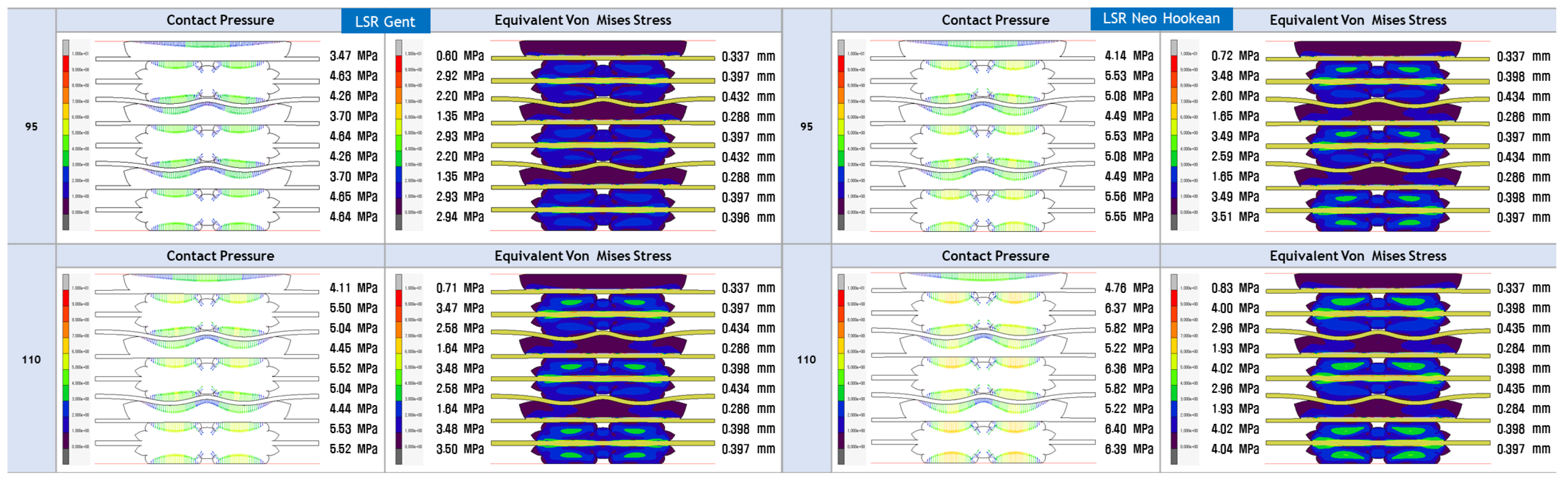

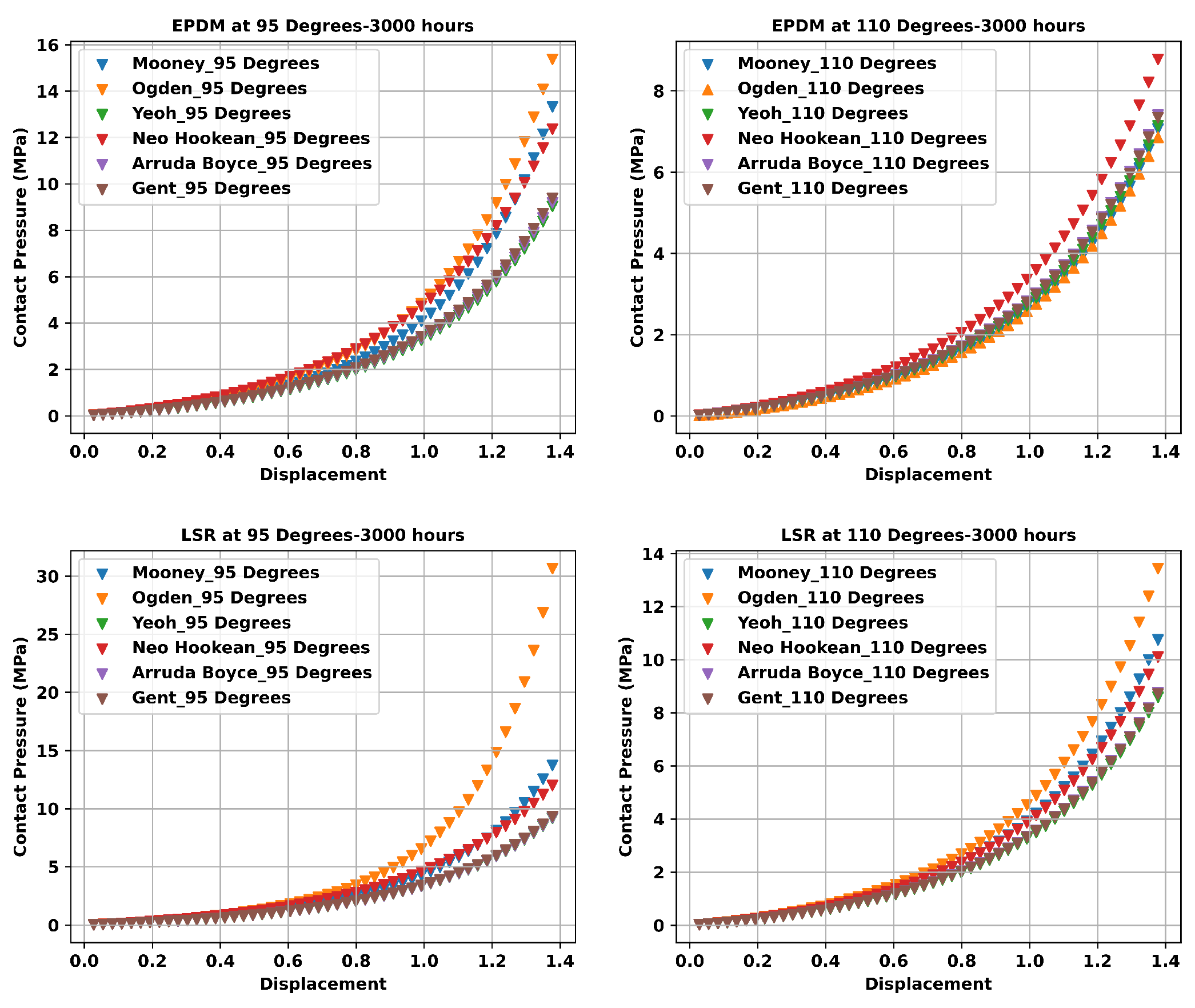

- The study’s focus is on evaluating the contact pressure distribution and Von Mises stress distribution for LSR and EPDM gaskets. These analyses shed light on each material’s sealing efficiency and mechanical stability under varying loading conditions, directly addressing the research gap concerning the structural integrity and long-term reliability of PEMFC gasket materials.

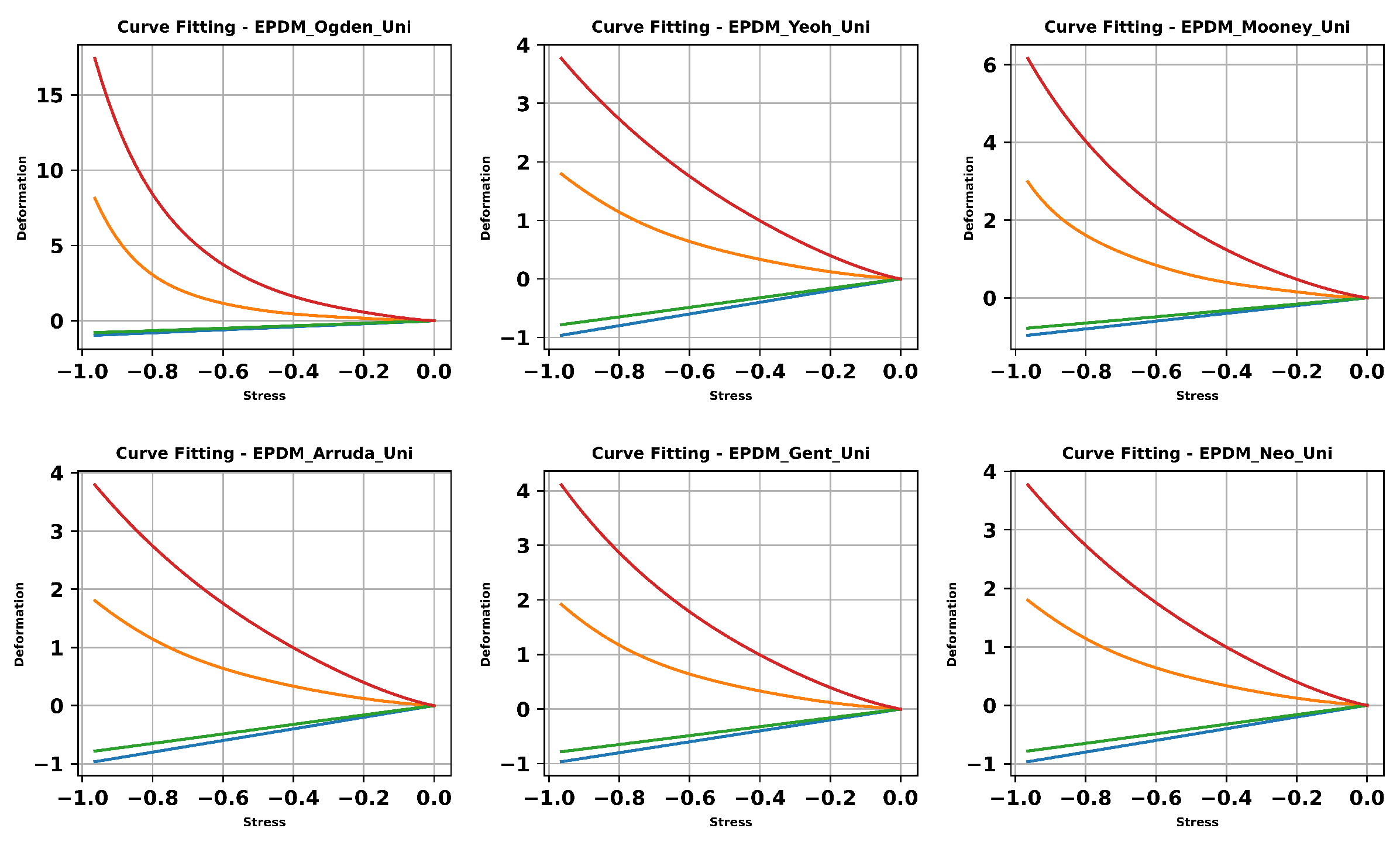

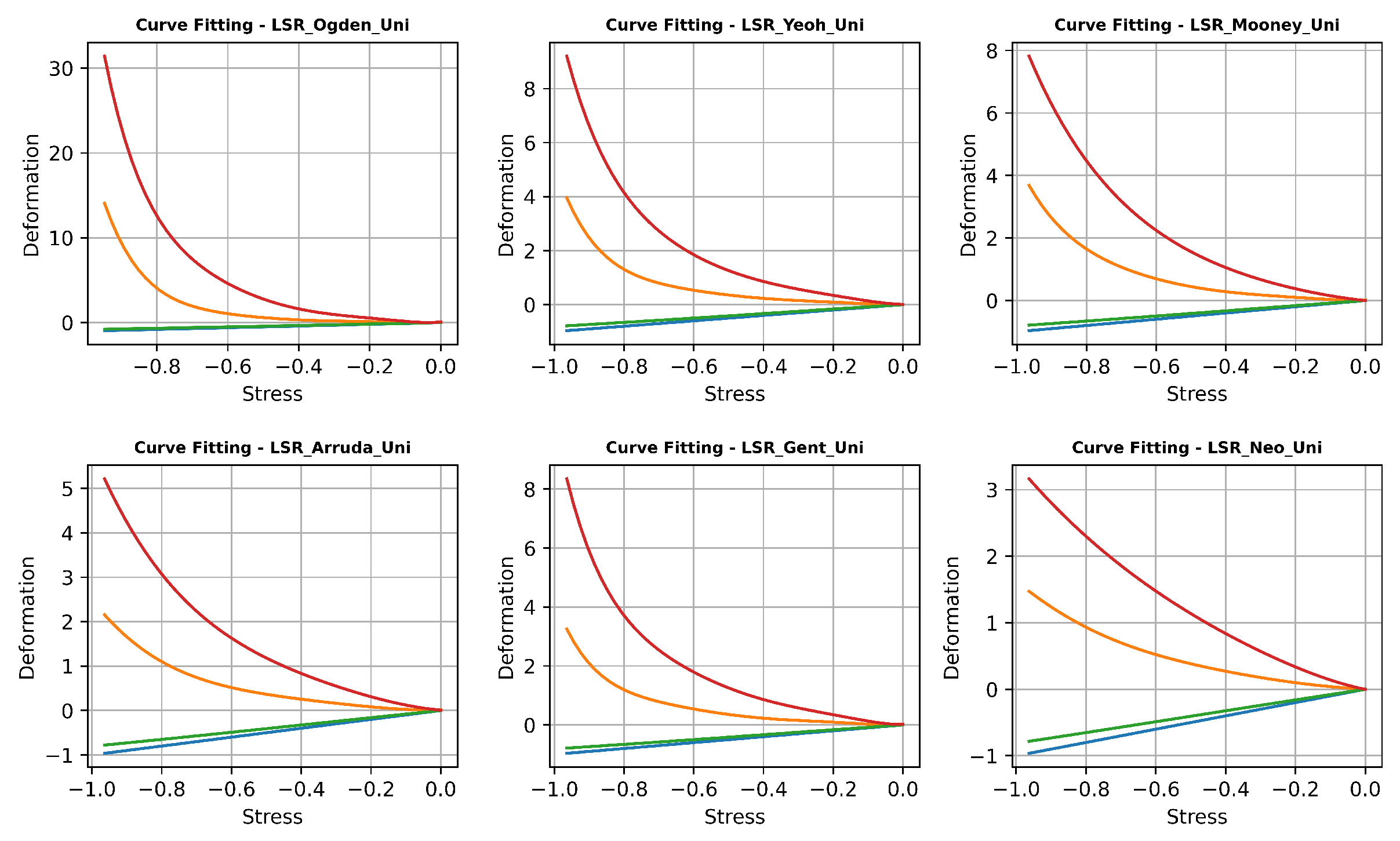

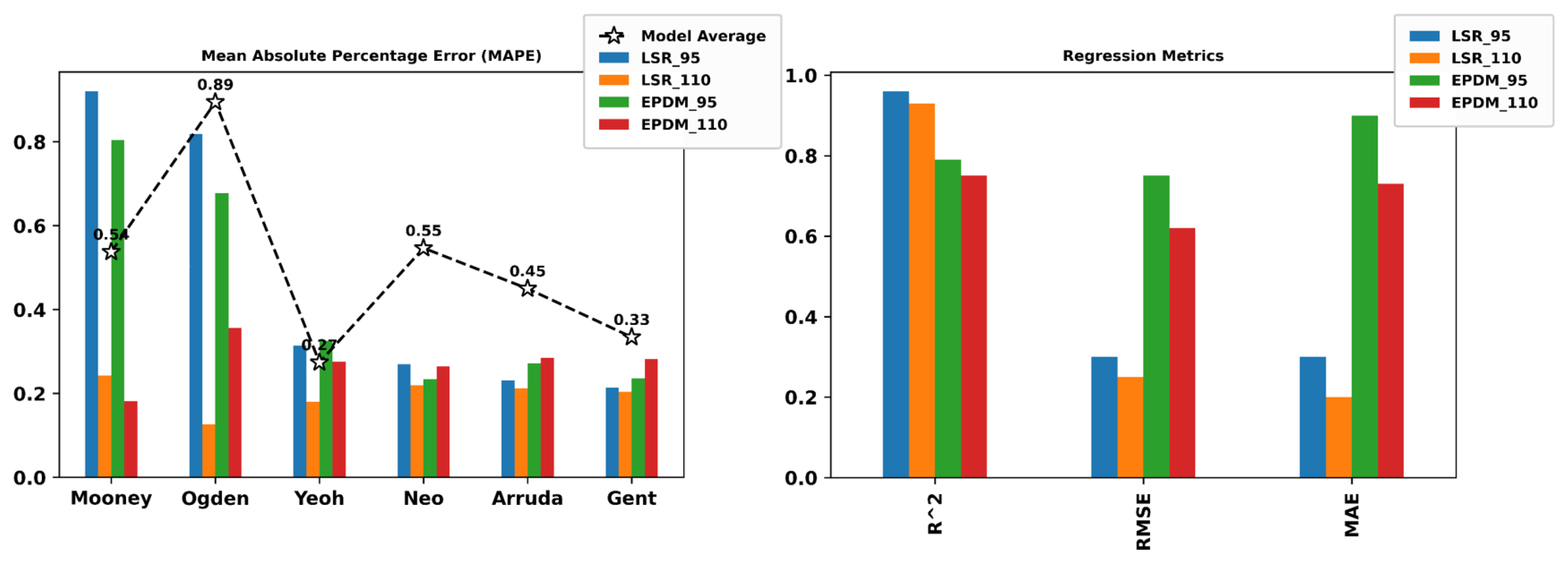

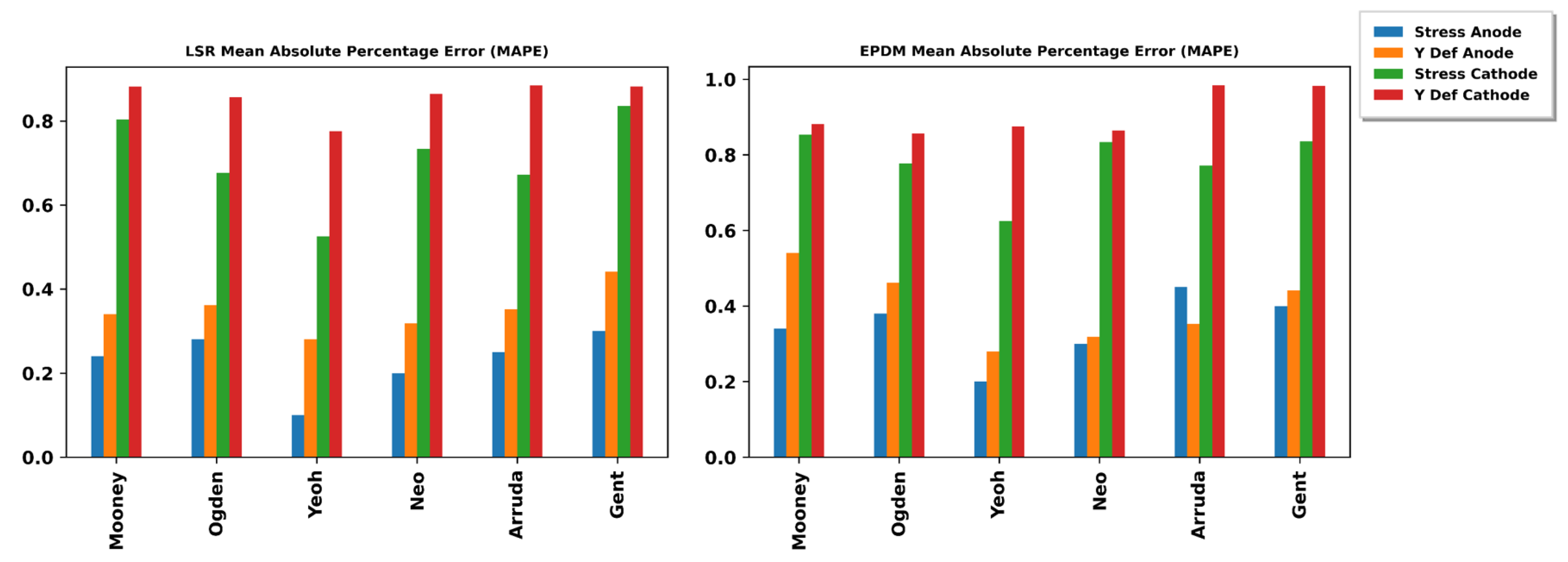

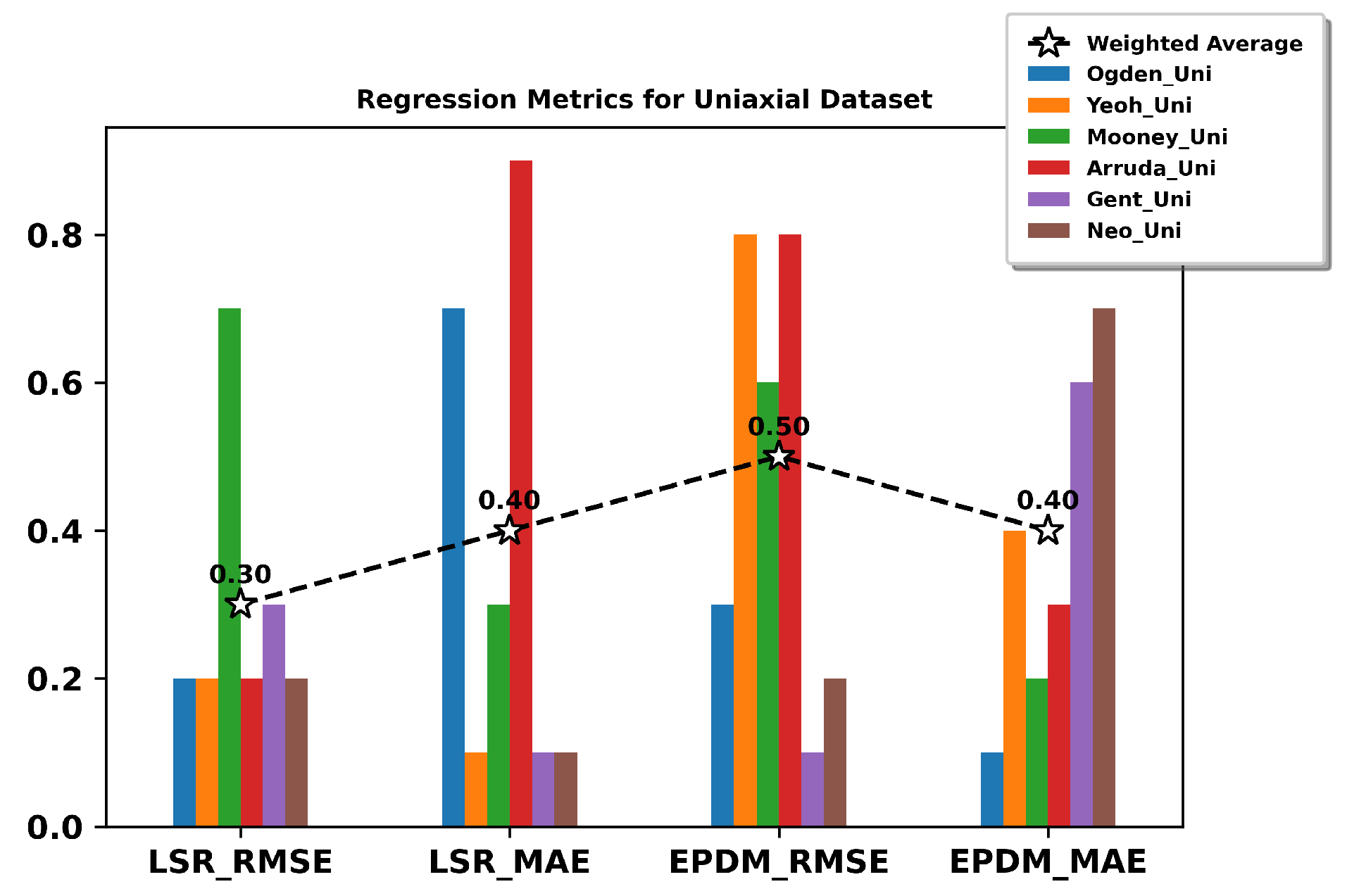

- The study aims to assess the accuracy of various hyperelastic models, such as Ogden, Gent, Mooney-Rivlin, Yeoh, Neo-Hookean, and Arruda-Boyce, in representing the mechanical behaviour of LSR and EPDM gasket materials. By evaluating these models and their predictions against experimental and FEA data, this research will provide valuable insights into the most appropriate hyperelastic model for accurately simulating the behaviour of gaskets in PEMFC applications.

2. Motivation, Literature Review, and Related Works

3. Theoretical Backgrounds

3.1. Overview of Gasket Material Selection

3.2. Overview of Hyper-elastic Constitutive Models

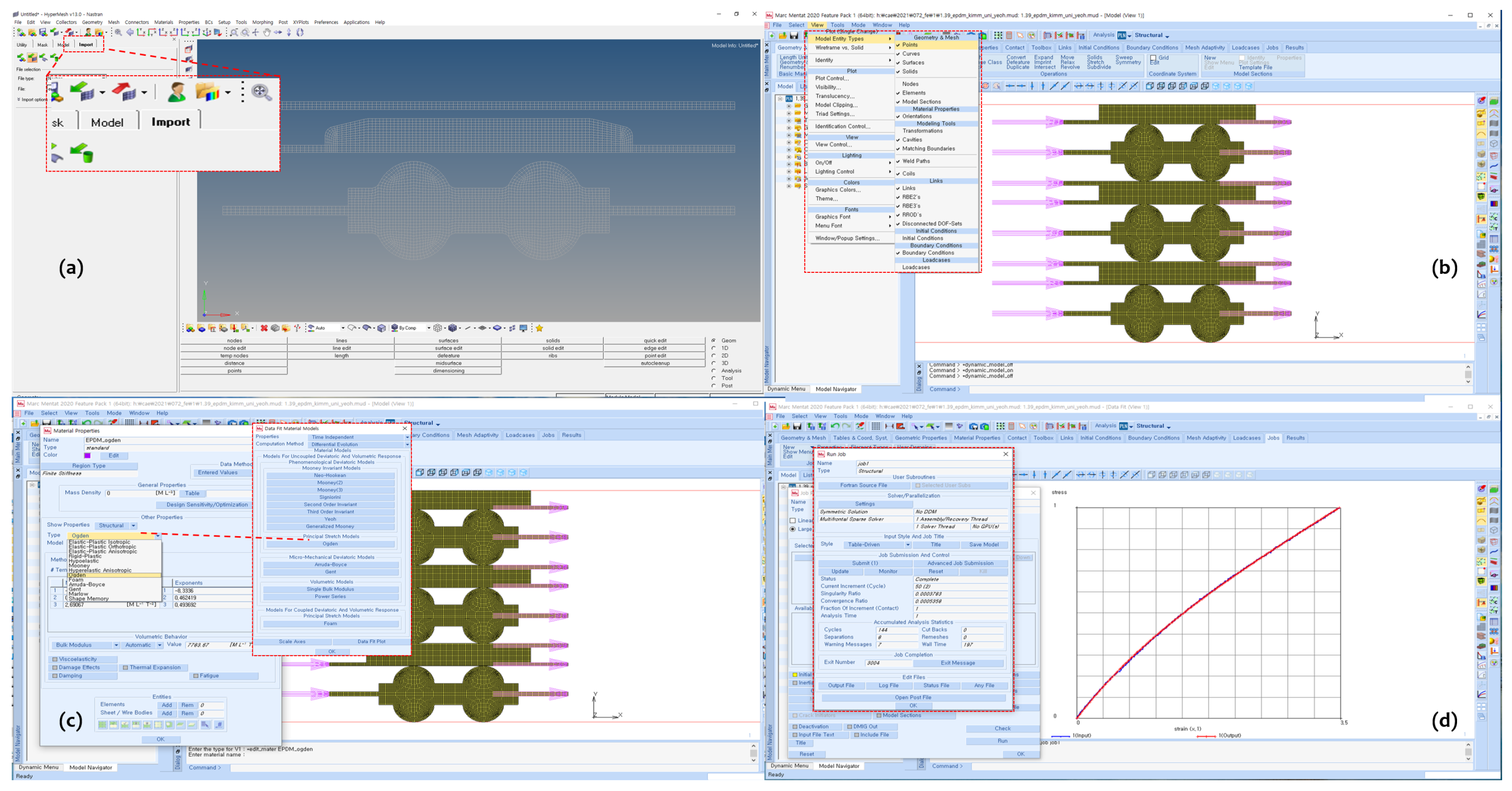

4. Proposed Gasket Material FEA Model

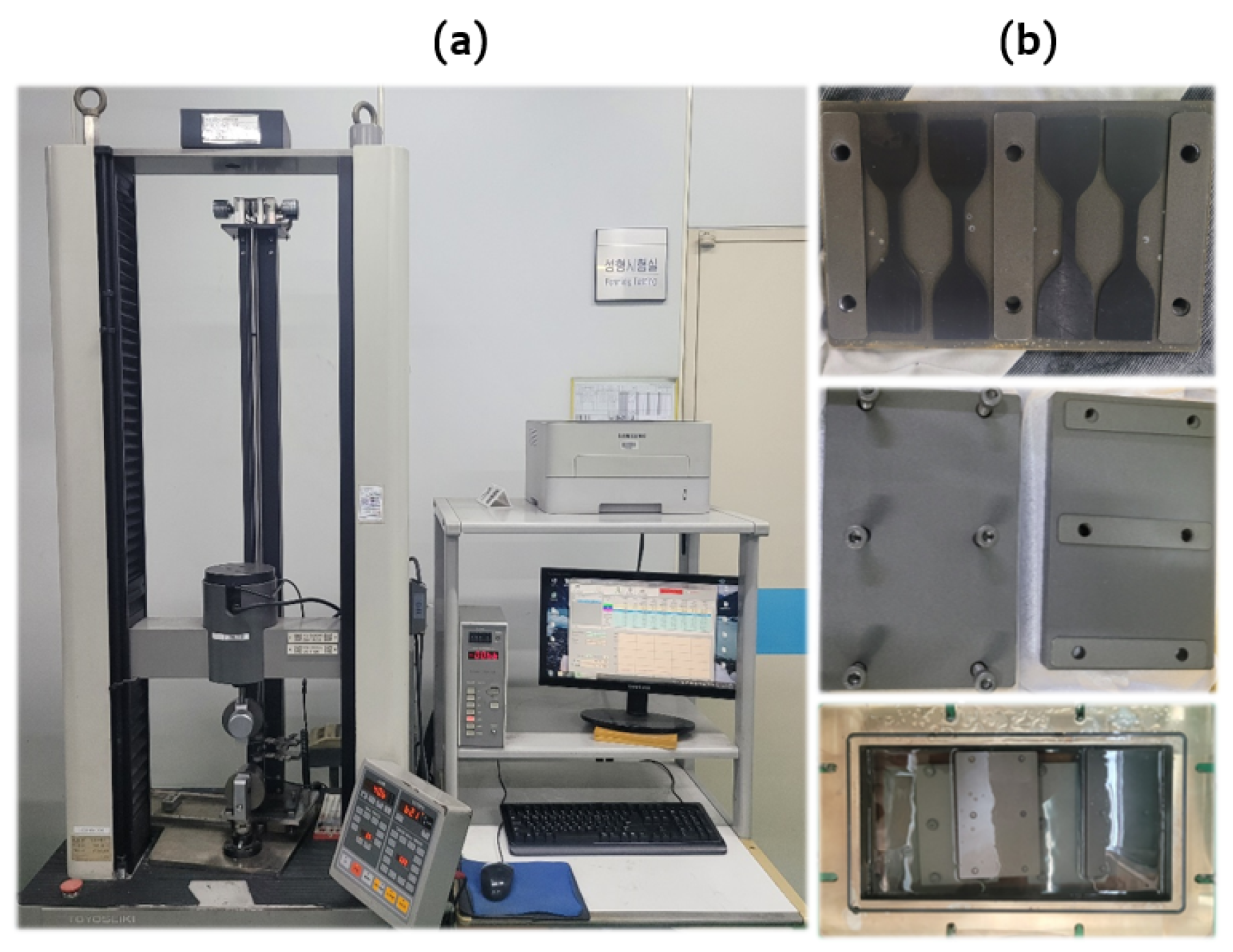

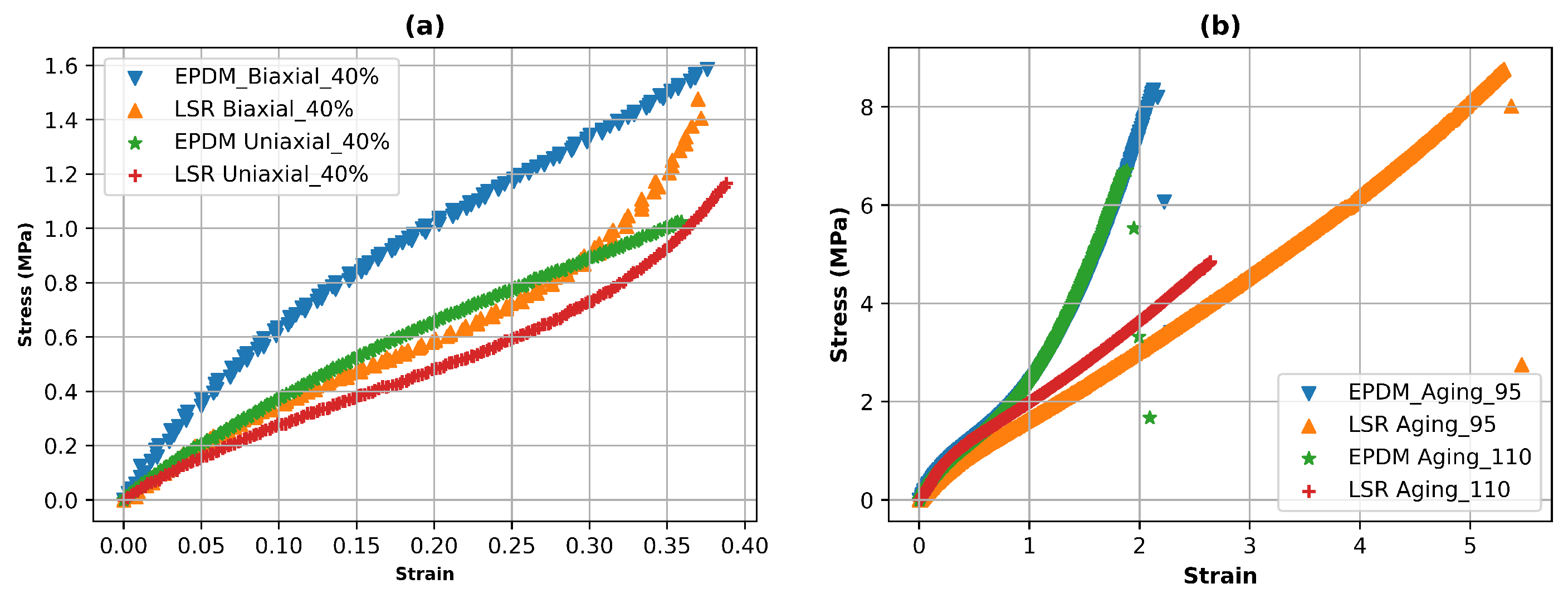

4.1. Experimental Testing for the Gasket Materials

4.2. Gasket Material FEA Modelling Characterization

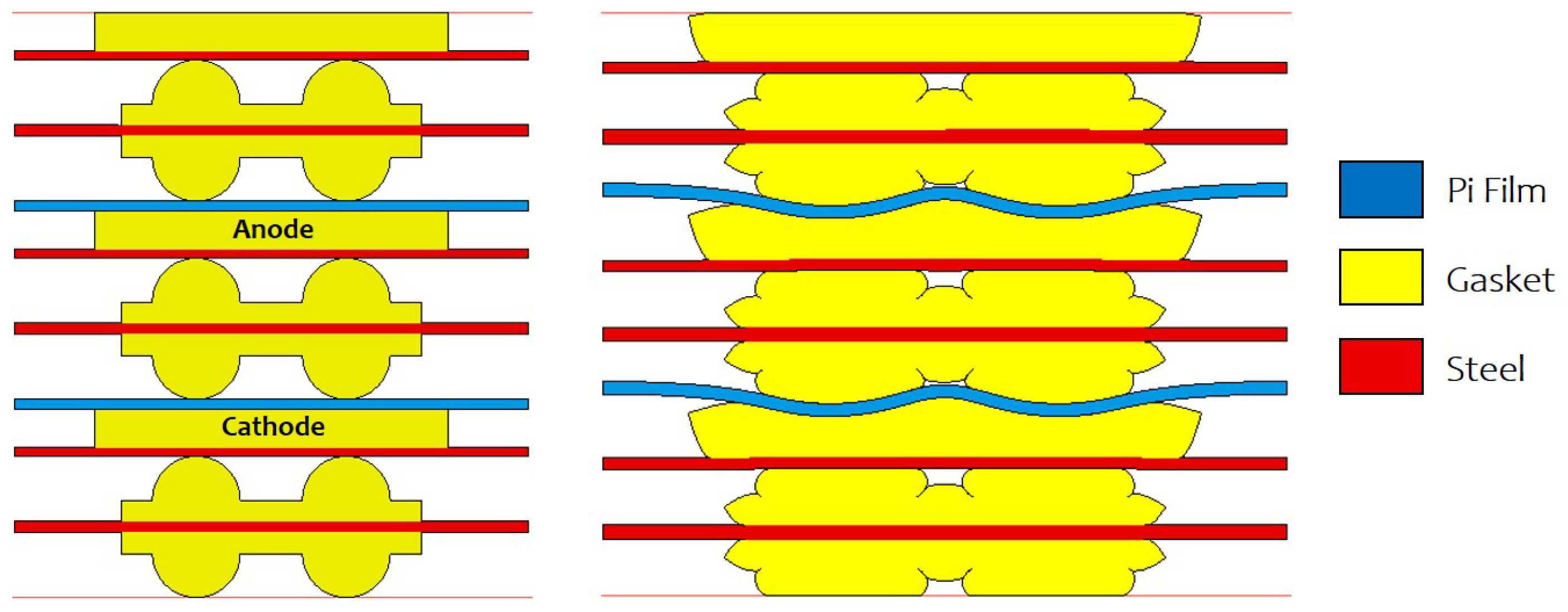

4.3. FEA Modelling Visualization

4.4. FEA Modelling Output and Curve Fitting Assessment

4.5. Proposed Non-Linear Regression Analysis

5. Non-Linear Regression Performance Metrics

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATIR-FTIR | Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| CR | Cluoropene Rubber |

| EPDM | Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| FEP | Fluorinated Ethylene Propylene |

| LSR | Liquid Silicon Rubber |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MEA | Membrane Electrode Assembly |

| MSE | Mean Square Error |

| NBR | Nitrite Butadiene Rubber |

| PEMFC | Proton-exchange membrane fuel cell |

| PFSA | Perfluoro Sulfonic Acid |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| R2 | R-Squared |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| VMQ | Silicone Rubber Vinyl Methyl Silicone |

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

Appendix A

References

- Manoharan, Y.; Hosseini, S.E.; Butler, B.; Alzhahrani, H.; Senior, B.T.F.; Ashuri, T.; Krohn, J. Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles; Current Status and Future Prospect. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2296. [CrossRef]

- John M. T.; Peter P. E.; Peter J. D.; Gari P. O.; Decarbonising energy: The developing international activity in hydrogen technologies and fuel cells, Journal of Energy Chemistry, Volume 51, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Asif J.; Sikander R.; Tanveer I.; Hafiza Aroosa A. K.; Haris M. K.; Babar Azeem, M.Z. Mustafa, Abdulkader S. H.; Current status and future perspectives of proton exchange membranes for hydrogen fuel cells, Chemosphere, Volume 303, Part 3, 2022, 135204, ISSN 0045-6535. [CrossRef]

- Pourrahmani, H.; Siavashi, M.; Yavarinasab, A.; Matian, M.; Chitgar, N.; Wang, L.; Van herle, J. A Review on the Long-Term Performance of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells: From Degradation Modeling to the Effects of Bipolar Plates, Sealings, and Contaminants. Energies 2022, 15, 5081. [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Wilberforce, T.; Alanazi, A.; Vichare, P.; Sayed, E.T.; Maghrabie, H.M.; Elsaid, K.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Novel Trends in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Energies 2022, 15, 4949. [CrossRef]

- Vikas K.; Poornesh K.; Koorata, U. S.; Pranav P.; Soney C. G. Review on physical and chemical properties of low and high-temperature polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell (PEFC) sealants, Polymer Degradation and Stability, Volume 205, 2022, 110151, ISSN 0141-3910. [CrossRef]

- Yiqing W.; Tahrizi A.; Yilin W.; Ying C.; Eric D. W.; Mark H. E.; Kenneth G. R.; Yong W.; Feng G.; Unmesh M.; Rohil D.; Dylan T.; Hongmei A.; Yuhui Z.;, Krishna K. A comparative study between real-world and laboratory accelerated aging of Cu/SSZ-13 SCR catalysts, Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, Volume 318, 2022, 121807, ISSN 0926-3373. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O.A.; Al Khattab, R. Fresh Properties and Sulfuric Acid Resistance of Sustainable Mortar Using Alkali-Activated GGBS/Fly Ash Binder. Polymers 2022, 14, 591. [CrossRef]

- Winter, L.; Lampke, T. Influence of Hydrothermal Sealing on the High Cycle Fatigue Behavior of the Anodized 6082 Aluminum Alloy. Coatings 2022, 12, 1070. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Tan, Y.; Li, B.; Ming, P.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, C. A Review of the Transition Region of Membrane Electrode Assembly of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells: Design, Degradation, and Mitigation. Membranes 2022, 12, 306. [CrossRef]

- Ke S.; Yimin W.; Yuhang D.; Hongjie X.; Philip M.; Tobias S.; Katharina B.; Christopher E.; Hannes W. W.; Jens S.; Juergen F.; Kai Z.; Florian W.; Matthias T.; Matthias S.; Albert A. Assembly techniques for proton exchange membrane fuel cell stack: A literature review, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 153, 2022, 111777, ISSN 1364-0321. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H., Lee, Y. K., and Kim, D. H. Mechanical properties of gasket elastomers for sealing applications. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2016, 133(42), 43873. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, A., and Shim, Y. Tensile behaviour of silicone rubber gaskets under different temperature conditions. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2017, 134(44), 44635. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J., Lee, C., and Kim, J. Tensile and compression properties of soft rubber gaskets used in automotive applications. Polymer Testing, 2015, 42, 42-47. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., and Li, X. Influence of filler type on the mechanical properties of nitrile rubber gaskets for sealing applications. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2017, 134(22), 45217. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Yang, J., and Li, Y. Tensile properties and stress relaxation behaviour of silicone rubber gaskets for automotive applications. Polymer Testing, 2015, 47, 90-95. [CrossRef]

- Cheon, K.-M.; Akpudo, U.E.; Kareem, A.B.; Nwabufo, O.C.; Jeon, H.-R.; Hur, J.-W. An FEA-Assisted Decision-Making Framework for PEMFC Gasket Material Selection. Energies 2022, 15, 2580. [CrossRef]

- Olayinka A.; Emblom W.J. Surface roughness of AISI 1010 and AISI 304 of PEMFC bipolar plates with microscale hydroformed capillary channels. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture. 2022; 236(10):1332-1340. [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan-Davis, Sebnem: Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) fuel cell seals durability. Loughborough University. 2016, Thesis. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/21749.

- Wu, F.; Chen, B.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Pan, M. Degradation of Silicone Rubbers as Sealing Materials for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells under Temperature Cycling. Polymers 2018, 10, 522. [CrossRef]

- Jun Feng, Qinglian Zhang, Zhengkai Tu, Wenmao Tu, Zhongmin Wan, Mu Pan, Haining Zhang, Degradation of silicone rubbers with different hardness in various aqueous solutions, Polymer Degradation and Stability, Volume 109, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. W., Chien, C. H., Tan, J., Chao, Y. J., and Van Zee, J. W. Dynamic mechanical characteristics of five elastomeric gasket materials aged in a simulated and accelerated PEM fuel cell environment. international journal of hydrogen energy, 2011, 36(11), 6756-6767. [CrossRef]

- Jie Zhang, Yang Hu, Sealing performance and mechanical behaviour of PEMFCs sealing system based on thermodynamic coupling, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 45, Issue 43, 2020, Pages 23480-23489. [CrossRef]

- Shen, L., Xia, L., Han, T., Wu, H., and Guo, S. Improvement of hardness and compression set properties of EPDM seals with alternating multilayered structure for PEM fuel cells. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2016, 41(48), 23164-23172. [CrossRef]

- Hu, G., Zhang, P., Wang, G., Zhang, M., and Li, M. The influence of rubber material on sealing performance of packing element in compression packer. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 2017, 38, 120-138. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. W., Chien, C. H., Tan, J., Chao, Y. J., and Van Zee, J. W. Chemical degradation of five elastomeric seal materials in a simulated and accelerated PEM fuel cell environment. Journal of Power Sources, 2011, 196(4), 1955-1966. [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan-Davis, S., Clarke, J., and Armour, S. Comparison of accelerated aging of silicone rubber gasket material with aging in a fuel cell environment. Journal of applied polymer science, 2013, 129(3), 1446-1454. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Tan, J., Wang, Y., Liu, Z., and Feng, Q. Chemical and mechanical degradation of silicone rubber under two compression loads in simulated proton-exchange membrane fuel-cell environments. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2019, 136(33), 47855. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H., Wan, Z., Chen, X., Wan, J., Luo, L., Zhang, H., and Tu, Z. (2016). Temperature and humidity effect on aging of silicone rubbers as sealing materials for proton exchange membrane fuel cell applications. Applied Thermal Engineering, 2016, 104, 472-478. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, C.; Fan, P.; Kuang, Y.; Dong, Z. The Sealing Effect Improvement Prediction of Flat Rubber Ring in Roller Bit Based on Yeoh-Revised Model. Materials 2022, 15, 5529. [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Wu, J.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Su, B.; Wang, Y. Effect of Geometric Error on Friction Behavior of Cylinder Seals. Polymers 2021, 13, 3438. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.C.; Mendes, A.d.O.; Ribeiro, M.L.; Vieira, A.C.; Carta, A.M.; Fiadeiro, P.T.; Costa, A.P. FEM Analysis Validation of Rubber Hardness Impact on Mechanical and Softness Properties of Embossed Industrial Base Tissue Papers. Polymers 2022, 14, 2485. [CrossRef]

- Latif R. F. and Shafi Khan N. "Comparative Analysis of Various Hyperelastic Models for Neoprene Gasket at Ranging Strains," 2019 16th International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technology (IBCAST), Islamabad, Pakistan, 2019, pp. 179-188. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. K., Kim, Y. H., and Kim, J. Y. Development of silicone-based gasket material for PEMFCs. Journal of Power Sources, 2018 284, 289-298. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., and Liu, Q. A review on proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) gasket materials. Journal of Power Sources, 2016, 308, 101-119. [CrossRef]

- Haque, M. E., and Danquah, M. K. A review on the design, selection and optimization of gasket materials for proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC). Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2015, 47, 766-776. [CrossRef]

- Rau, N., and Spiess, W. Fluorinated Ethylene Propylene (FEP) gaskets for proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs): An overview. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2016, 133(14), 43189. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. J., and Kim, J. Y. Performance comparison of silicone and fluoropolymer gaskets for proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs). Journal of Power Sources, 2018, 389, 157-166. [CrossRef]

- Baker, J. M., and Kim, Y. Dynamic mechanical analysis of an EPDM rubber. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2013, 130(1), 378-384. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, N. C., and Bose, S. K. Studies on the thermal and mechanical properties of EPDM and its composites. Polymer Composites, 2015, 36(3), 631-637. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Chen, J., and Han, X. Preparation and properties of EPDM/organic silica hybrid nanocomposites. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2015, 132(43), 42076. [CrossRef]

- Hiltunen, M., Nurminen, J., and Ahola, S. Effect of filler type and content on the properties of EPDM rubber compounds. Rubber Chemistry and Technology, 2015, 88(3), 564-576. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Zhang, Y., and Han, X. Synthesis and properties of EPDM/organoclay nanocomposites. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2013, 128(6), 4117-4123. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y., Xu, L., and Du, Y. Recent advances in liquid silicone rubber (LSR) materials and applications. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2020, 137(3), 48180. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H., Lee, H. J., and Kim, K. H. Preparation and mechanical properties of liquid silicone rubber/silicone rubber composite materials. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2019, 136(22), 47758. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H. W., and Li, J. H. Application of liquid silicone rubber (LSR) materials in medical and healthcare products. Polymers, 2020, 12(6), 1019. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Li, Q., Li, H., and Qiu, Q. A review of liquid silicone rubber (LSR) material and its processing technologies. Polymers, 2019, 11(12), 2288. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Li, C., Li, S., and Zhang, X. Properties and applications of liquid silicone rubber (LSR) in 3D printing. Polymers, 2020, 12(10), 1866. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., and Lin, T. The research progress of liquid silicone rubber (LSR) materials in the field of soft-touch consumer electronics. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2019, 136(24), 48005. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Sun, Y., and Liu, Y. Study on the thermal stability and mechanical properties of liquid silicone rubber (LSR) under high-temperature conditions. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2019, 136(12), 46936. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Wang, L., and Lu, J. The research progress of liquid silicone rubber (LSR) materials in the field of aerospace. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2019, 136(18), 46580. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S. K., Kim, Y. J., and Jeong, J. S. Characterization of FKM and VQM elastomers used in various sealing applications. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2019, 136(33), 46699. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., and Lee, Y. J. Performance comparison of FKM and VQM elastomers in high-temperature sealing applications. Journal of Polymer Engineering, 2017, 37(9), 831–839. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J., and Lee, S. H. Evaluation of mechanical and dynamic mechanical properties of FKM and VQM elastomers. Journal of Elastomers and Plastics, 2015, 47(3), 165–173. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Liu, Y., and Chen, X. FKM and VQM elastomers as dynamic seal materials: A review. Journal of Polymer Engineering, 2019, 39(12), 901–913. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J. H., and Kim, J. H. Chemical and thermal stability of FKM and VQM elastomers in high-temperature applications. Journal of Polymer Science and Technology, 2017, 27(2), 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Murea, C.M. Updated Lagrangian for Compressible Hyperelastic Material with Frictionless Contact. Appl. Mech. 2022, 3, 533-543. [CrossRef]

- Ogden, R., Saccomandi, G. & Sgura, I. Fitting hyperelastic models to experimental data. Computational Mechanics 34, 484–502 2004. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B., Lee, S.B., Lee, J. et al. A comparison among Neo-Hookean model, Mooney-Rivlin model, and Ogden model for chloroprene rubber. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 13, 759–764 2012. [CrossRef]

- Khaniki, H.B., Ghayesh, M.H., Chin, R. et al. A review on the nonlinear dynamics of hyperelastic structures. Nonlinear Dyn 110, 2022, 963–994. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Li, J., and Niu, S. A viscoelastic constitutive model for gasket materials under dynamic loading. Journal of Applied Mechanics and Technical Physics, 2019, 60(6), 763-771. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Su, J., and Hu, X. A constitutive model for gasket material based on the logarithmic strain rate. Journal of Applied Mechanics and Technical Physics, 2017, 58(2), 244-252. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., and Liu, Y. Constitutive models for gasket materials considering the nonlinear behaviour of fibre-reinforced rubber composites. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics, 2015, 77, 16-25. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., and Jiang, H. A new hyperelastic constitutive model for gasket materials under large deformation. Journal of Mechanics, 2017, 33(6), 797-807. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Li, H., and Niu, S. An improved constitutive model for gasket materials considering the nonlinear behaviour of rubber composites. International Journal of Mechanics and Materials in Design, 2018 14(1), 53-65. [CrossRef]

- Singla, M.K.; Nijhawan, and P. Oberoi; A.S. Hydrogen fuel and fuel cell technology for cleaner future: a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28, 2021, 15607–15626. [CrossRef]

| EPDM | LSR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Uni | Uni + Bi | Uni | Uni + Bi |

| Mooney Rivlin | = 4.72729e-07 | = 0.646931 | = 4.38303e-08 | = 0.421825 |

| = 0.749213 | = 6.03391e-11 | = 0.50852 | = 6.03424e-11 | |

| = 0.143837 | = 0.00225633 | = 0.422279 | = 0.0257173 | |

| Yeoh | = 0.643052 | = 0.644965 | = 0.479358 | = 0.3965 |

| = 4.30289e-11 | = 5.07886e-08 | = 9.36578e-09 | = 5.4214e-09 | |

| = 2.56582e-08 | = 0.00478875 | = 0.379155 | = 0.0479549 | |

| Ogden | M = -0.209622 E = -8.3336 | M = -2.14506e-05 E = -0.0658951 | M = -0.256473 E = -9.15496 | M = -2.31696e-07 E = -22.8029 |

| M = 0.0826136 E = 0.462419 | M = -1.27328e-05 E = -0.0417977 | M = -0.0108753 E = -9.06697 | M = 0.35083 E = 4.46914 | |

| M = 2.69067 E = 0.493692 | M = 0.939258 E = 2.81305 | M = 0.000119912 E = 24.9996 | M = 5.80656e-05 E = 24.9999 | |

| Neo-Hookean | = 0.643045 | 0.647817 | = 0.538368 | = 0.468658 |

| Arruda Boyce | = 1.26113 | = 1.27561 | = 0.336706 | = 0.492217 |

| = 33.1881 | = 44.4993 | = 1.1 | = 1.84821 | |

| Gent | = 3.80574 | = 3.86915 | = 2.79158 | = 2.39144 |

| = 16.5941 | = 93.0439 | = 4.52345 | = 7.1634 | |

| EPDM | LSR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | ||||

| Mooney Rivlin | = 1.89472e-09 | = 2.69426e-08 | = 0.430276 | = 0.3454 |

| = 0.609227 | = 0.639308 | = 0.0162594 | = 0.33012 | |

| = 0.194325 | = 0.193217 | = 0.016835 | = 0.0323504 | |

| Yeoh | = 0.559296 | = 0.571377 | = 0.475585 | = 0.573542 |

| = 0.026558 | = 0.0237455 | = 0.00318065 | = 0.00468581 | |

| = 0.00294048 | = 0.00393118 | = 2.74909e-13 | = 2.83474e-10 | |

| Ogden | M = -0.664004 E = -3.93474 | M = -0.146388 E = -9.04283 | M = -0.402385 E = -0.686773 | M = -0.563078 E = -3.63278 |

| M = -2.20126e-05 E = -0.0664976 | M = -0.913931 E = -1.97932 | M = 0.626279 E = 2.41526 | M = -0.000248025 E = -0.0898954 | |

| M = 0.0757264 E = 4.91726 | M = -0.000730606 E = -0.0493021 | M = 7.91621e-13 E = 15.2995 | M = 0.328036 E = 2.76844 | |

| Neo-Hookean | = 0.843536 | = 0.817821 | = 0.594852 | = 0.685988 |

| Arruda Boyce | = 0.942321 | = 0.917499 | = 0.972442 | = 1.1427 |

| = 3.61357 | = 3.33084 | = 28.6273 | = 20.9499 | |

| Gent | = 3.54155 | = 3.49077 | = 2.95009 | = 3.50546 |

| = 15.1266 | = 13.6892 | = 119.115 | = 88.4981 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).