1. Introduction

Cities are crucial sites for sustainable development. More than half of the global population lives in urban areas, and the urban component of the world’s population is expected to reach 68% by 2050 [

1]. SDG 11 “Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable” is one of 17 SDGs adopted by the General Assembly of the UN in 2015 [

2]. SDG 11’s 10 targets and 15 indicators cover a broad scope of issues from affordable housing and infrastructure to cultural and natural heritage.

According to the 2023 Sustainable Development Reports, only one country of the 219 countries has SDG 11 achievement on track, and 143 (65%) countries experience significant and major challenges in its implementation [

3]. For example, only countries in Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand have achieved the indicators in reducing the proportion of the urban population living in slums (Target 11.1, “By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums” (

https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11). Note, the term “slums” has been criticized as having a stigmatizing effect but we use it here to match the UN’s own language), while the rest of the world is still far from that, and the situation continues to deteriorate [

4]. Because of such challenges, fulfilling the SDGs requires much stronger “co-production” between governments, researchers, bottom-up civil society organizations, and other players [

5] (p. 5).

In this paper, we analyze SDG good practices information collected by the UN from around the world in 2018-2021 [

6,

7] to ask, what can be learned from these initial calls about how SDG 11 has been implemented to date worldwide. We structure responses by five criteria: (1) geography of submitted good practices; (2) actors addressing SDG 11; (3) progress toward SDG 11 targets; (4) topical areas of implementation; and (5) scale of action. We seek to find out major patterns in this field, with attention to practical implications and social equity, and develop recommendations based on this data in light of existing literature on the topic. The results of this study will be helpful for policymakers, advocates, and researchers at international, national, regional, and local levels of sustainable development.

2. Background

In documents relevant to SDG 11 implementation, three thematic areas emerged: (2.1) practical issues around implementation, (2.2) measurement of progress, and (2.3) criticism of SDG 11 and its implementation.

2.1. Practical Issues Around Implementation

Most of the studies explored specific cases of SDG 11 implementation within national, regional, or local contexts. Predictably, many found that implementing sustainable city concepts is not easy. For example, Krellenberg et al. [

8] (p. 16) found that Milwaukee (USA), Saint Petersburg (Russia), and Hamburg and Magdeburg (Germany) struggled to establish a long-term commitment to sustainability, indicators, and political leadership in their strategic plans because of “insufficiently participatory, inadequately ambitions, and/or competing or overlapping with other city initiatives.” Koch et al. [

9] (p. 14) considered cities in Germany and found the main challenges: “indicators and data availability, tradeoffs with other SDGs, the role and limitations of urban planning, and the difficulties of city-wide integration of sustainability policies.”

Several studies investigated effective governance systems to support the implementation of SDG 11. Common themes included coordination between international, national, regional, and local goals and policies, and the need for bottom-up approaches but also state assistance and leadership. For example, Martínez-Córdoba et al. [

10] found that progressive municipal governments in Spain prioritized increasing civic engagement over other targets of SDG 11, while conservative governments mainly addressed housing, safe and accessible public areas, and daily solid waste removal. They concluded that ideological consensus between the levels of government positively influenced the progress toward SDG 11. In a study of three Indian cities, Tiwari et al. [

11] concluded that a bottom-up approach is essential in implementing SDG 11, but that state support for local governments to do this is needed. Zhu et al. [

12] (p. 347) discussed interactions between multiple stakeholders in implementing green building initiatives in China, whose different stakeholder roles and interests may lead to positive synergies or negative trade-offs in achieving SDG 11, and that “all parties need to do more.” Abraham and Iyer [

13] (p. 5) presented case studies of SDG implementation from Canadian and U.S. cities, concluding that “when localization has occurred, the impetus has predominantly come from the bottom-up in most of these cities” but that low awareness of the SDGs and lack of leadership are hampering North American SDG implementation.

Some authors mentioned the efficacy of different approaches: a chain-based or nexus approach to program development, for example, “the water-energy-food nexus” [

9] (p. 22), [

14] the clustering of targets from several SDGs in addressing a single local issue [

15], an integrated approach dimensions: social, environmental, economic, and political [

16]. Sustainable development of cities requires incorporating long-term thinking, a holistic perspective, and proactive leadership to address problems [

17].

2.2. Measurement of Progress

A large body of work explores various techniques for measuring progress toward SDG 11 and the SDGs in general. Several groups have applied spatial data analysis to monitor and evaluate progress toward multiple SDGs [

18,

19,

20], disaster risk mitigation, and migration [

21,

22]. Other authors addressed the localization of the indicators of SDG 11 by incorporating available measurements, including indices of social, economic, and environmental development calculated from 60 local indicators in China [

23], parameters of local budgets to the quality of women’s life in Turkey [

24], sub-national indices for each SDG in Romania [

25], and indicators of SDG 11 directly calculated based on the relevant local data in Japan [

26].

Some authors discussed the political frameworks for measuring the indicators of SDG 11 at the local level. Beisheim et al. [

27] indicated that transnational multi-stakeholder partnerships yield better results if they leverage local ownership. Valencia et al. [

28] showed that an integrated governance model with both horizontal and vertical collaboration between actors can provide coherence among global and regional agendas at the local level. Rozhenkova et al. [

29] argued that a city policy database that is regularly updated and available online is necessary.

2.3. Criticism of SDG 11 and its Implementation

Almost every source mentioned the lack of data as a main limitation in the implementation and evaluation of SDG 11 [

10,

16,

18,

30,

31]. Satterthwaite [

5] argued that the success of SDG 11 directly depends on the availability and accessibility of robust data, and Elsey et al. [

32] underlined the need for data to plan and allocate resources to address urban inequalities.

According to Mohd Khalid et al. [

33], the limited capacity of actors to collect data, inadequate coordination among governments and institutions, and limited financing cause significant problems in SDG implementation, especially in developing countries. Simon et al. [

34] claimed that none of the five cities they studied had complete, straightforward, and appropriate data on indicators available. Patel et al. [

30] found consistent SDG 11 implementation as requiring reconfiguration of governance systems because capacity in data collection and analysis is so highly variable among cities.

Another point receiving substantial criticism is the relevance and clarity of SDG 11 targets and indicators. Valencia et al. [

28] claimed that efforts to achieve some of the targets, for example, 11.5 and 11.b, addressing disaster preparedness, competition, or conflict have been very challenging to achieve. They argued many governments’ indicators address neither the quality of policy nor the effectiveness of implementation. Furthermore, excessive focus on disasters diverts attention from smaller but more frequent impacts that, over time result in severe social and economic damage. Simon et al. [

34] criticized indicator 11.2 of SDG 11 (the proportion of the population having convenient access to public transportation), arguing that this indicator should include topography, physical obstacles, and safety issues like lighting and open paths.

Šilhankova et al. [

35] argued that in practice indicators are often a tool for competition between jurisdictions, allowing them to highlight strengths and hide weaknesses in international comparisons. According to Hansson et al. [

36] (p. 230), because of the need to reduce the vagueness of indicators and avoid confusion in the implementation of SDG 11, local actors should be allowed to select indicators “that fulfill the criteria of easy measurement or collection, appropriateness, convenience, and relevance to current conditions and policies and programs.”

SDGs were criticized for a one-size-fits-all approach and for not considering different national and local capabilities and circumstances. For example, Naeem et al. argued that one city cannot directly implement the planning and policies of another site; instead, those policies need to be adjusted “according to local conditions and available resources” [

37] (p. 1).

Despite such criticisms, most authors agree that intersectional and comprehensive SDGs like SDG 11 are, in fact, very helpful in consolidating resources and addressing complex issues of global concern. The presence of critical voices means that there is still room to improve the SDG 11 framework and practices of implementation within specific national and local contexts.

3. Materials and Methods

We reviewed SDG good practices in the UN database and collected quantitative data about SDG 11 good practices submitted by all types of actors. We also developed the previously mentioned classification system to analyze the data on the implementation of SDG 11 within different contexts. Finally, we used descriptive statistics to illustrate findings from this review and sought to spell out implications and recommendations.

An inter-agency review team of experts in sustainable development from across the UN system curated the UN SDG Good Practices Database. To collect these cases, the UN conducted two open calls. The purpose of these calls was to highlight examples of good practices, including those that could be replicated or scaled up by others across the globe. Each received over 700 submissions from national governments, regional offices of the UN, and other stakeholders through an online web portal. From the first open call in 2018 and 2019 (Open Call 1), experts selected 511 cases as meeting the criteria for good practices [

6], and from the second open call from 2020 to 2021 (Open Call 2) they selected 464 more [

7]. Of those 975 cases, the UN experts identified 336 good practices (34.4%) as those addressing SDG 11 (186 practices in Open Call 1 and 150 practices in Open Call 2).

We reviewed all 336 good practices marked as addressing SDG 11 and categorized them according to the following criteria:

1. Geography of submitted good practices: what country produced each practice and whether these nations represented (i) developed economies, (ii) economies in transition, and (iii) developing economies. This classification was developed by UN entities [

38].

2. Actors addressing SDG 11: whether institutions carrying out the good practice were (i) national governments and their agencies; (ii) regional (sub-national) governments and agencies; (iii) municipalities and city-level government agencies; (iv) public agencies; (v) UN entities, including regional offices and programs; (vi) civil society (non-government) organizations; (vii) international development institutions; (viii) private companies; and (ix) other actors not mentioned in the categories from (i) to (viii). For each good practice, the UN has identified one main responsible entity employing these categories.

3. Progress toward SDG 11 targets: specific targets that the good practice addressed of the ten SDG 11 targets. For example, 11.1 - Affordable housing, 11.2 - Sustainable transport system, and 11.7 - Access to green and public spaces, etc. Since very few practices directly stated which targets of SDG 11 they addressed, we identified targets based on our own analysis of the content, objectives, implementation activities, and results of individual submissions. Many practices addressed more than one target.

4. Topical areas of implementation: fields of urban development addressed by good practices, for example, management, inclusiveness, and transportation (Appendix 1). The specific field of urban development is emphasized based on the content of good practices after reviewing the Introduction, Objective, Implementation of the activities, and Results/Outputs/Impacts sections of good practices. Some good practices emphasized more than one area of implementation, in which case all were included.

5. Scale of action: (i) international, (ii) national, (iii) regional (sub-national), (iv) large cities with a population of 200,000 and over, and (v) small cities with a population under 200,000. They are determined by the actors who submitted those practices in geographical coverage and/or region sections of the UN SDG good practices.

Finally, we used descriptive statistics to analyze trends and patterns within the good practices database and drew upon the literature to spell out implications and recommendations. We did this keeping in mind that the SDGs represent just one step in a long process of developing global consensus around sustainable development directions, and will undoubtedly be improved upon by further generations of goals and indicators. Laying the groundwork now for stronger and more useful tools in the post-2030 period is an urgent need.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Geography of Submitted Good Practices

Out of 193 countries that approved the SDGs and 2030 Agenda, 86 submitted good practices for the implementation of SDG 11, including 24 developed countries, 55 developing countries, and seven countries in transition (see

Table 1).

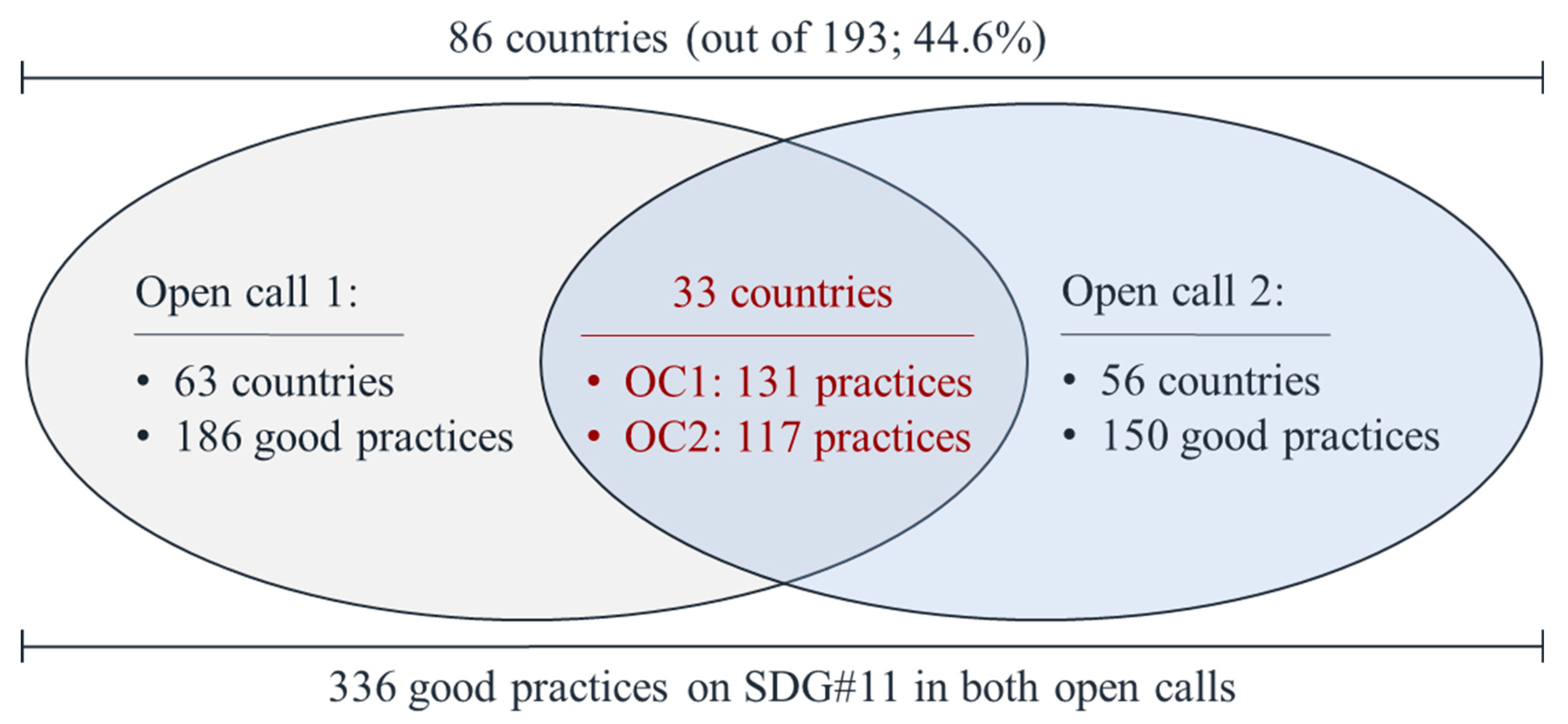

Sixty-three countries submitted good practices during the first open call and 56 during the second open call. European Union countries submitted more than any other geographical region with Spain (14), Belgium (11), and France (8) contributing the most. The USA and other Anglophone countries were notably underrepresented in their contributions, as were countries from sub-Saharan Africa.

Developing countries submitted 202 of 336 good practices (60.1%), while developed countries submitted 120 (35.7%), and those with economies in transition submitted 14 (4.2%). This breakdown was almost the same during both open calls, which seems reasonable considering that developing countries face the issues of the SDG 11 scope much more frequently than developed countries. Only 33 countries (17.1% of those that approved the 2030 Agenda) submitted good practices during both open calls (

Figure 1), thus reflecting a commitment to continuously address SDG 11 implementation.

Eleven of these 33 nations are developed (Belgium, Great Britain, Japan, Sweden, USA, etc.), while 21 are developing (Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Mexico, Turkey, etc.), and one is in transition (Russia). Even more remarkable is that those 33 nations aggregately submitted 73.8% of total good practices.

Overall, 107 of 193 countries that adopted the 2030 Agenda have not submitted any good practices for SDG 11, including 85 developing countries (36 countries from sub-Saharan Africa), 12 developed countries, and

10 countries with economies in transition. This relatively low and uneven response appears to reflect the slow growth of global coordination on sustainable urban development. Other likely reasons for low response rates include a lack of resources, data, political commitment, and lingering disempowerment of some countries from a legacy of colonialism and imperialism [

39], as well as the relatively short time frame between SDG adoption in 2015 and these UN calls. If such low response rates continue in the future, strong efforts to increase coordination, funding, and technical assistance around SDG 11 would seem appropriate.

4.2. Actors Addressing SDG 11

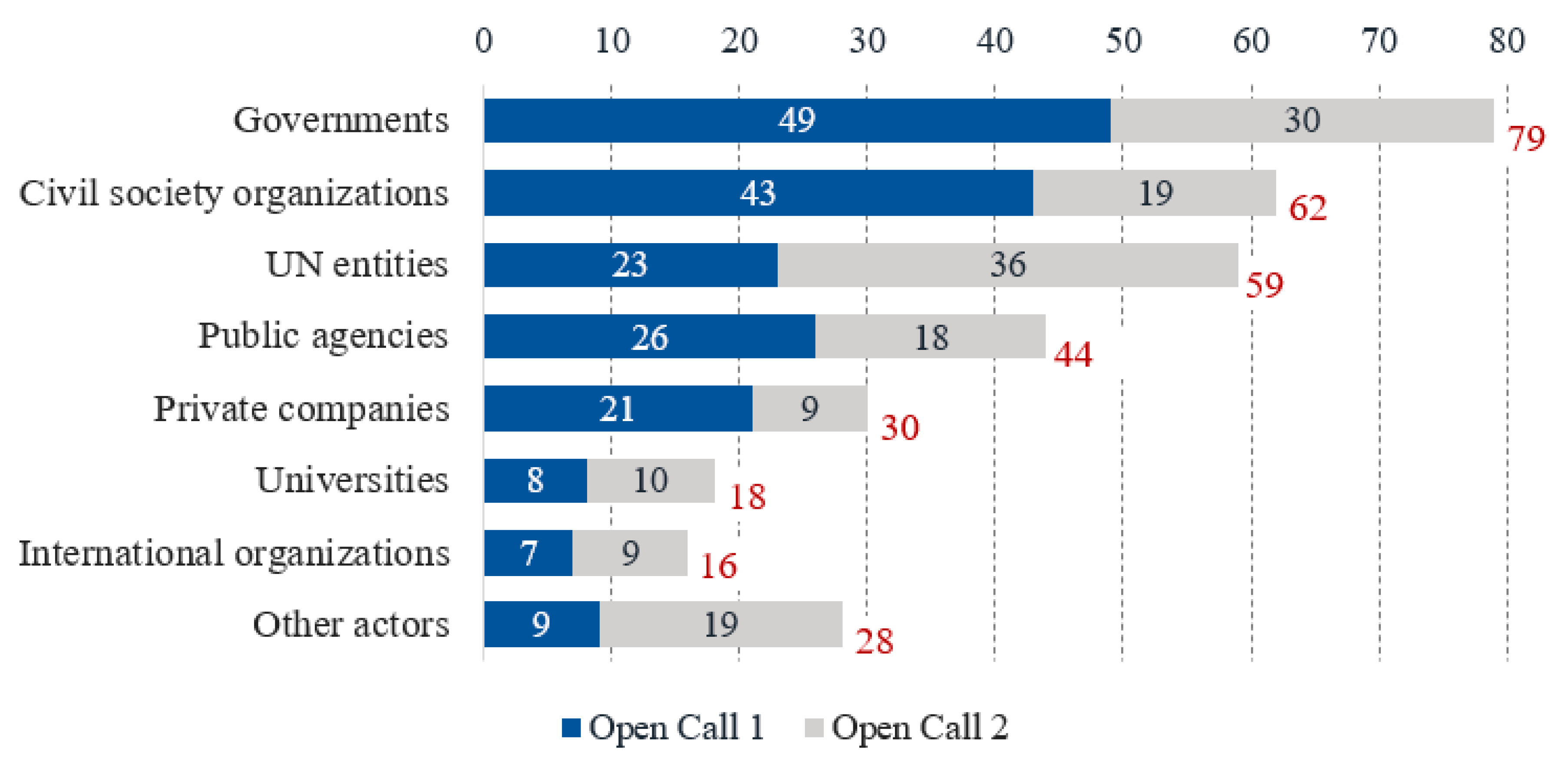

Out of 336 SDG 11 good practices, national, regional, or local governments submitted 79 (23.5% of the total), followed by civil society organizations (62 practices, or 18.5%), and UN entities (59, or 17.6%) (

Figure 2).

The distribution of submissions across scales of government was relatively even. National and sub-national authorities submitted 27 good practices each, and municipalities submitted 25. However, during the second open call, national and subnational responses fell by more than half compared to the first open call, while responses from municipalities increased slightly (14 compared to 11). A potential explanation is that at the beginning of this period, national and sub-national authorities sought to establish a general framework for SDG implementation within national agendas and strategies, while once this framework was established municipalities were encouraged to take more specific action.

The initiation of action at a national level seems to have been a common pattern. For example, after 2015 the Government of Benin developed a tool to quantify the impact of each national ministry on the SDGs. That tool analyzed the extent and depth to which each ministry's annual working plan included SDGs within budget allocations. About 6,000 activities were mapped and analyzed according to (i) their nature, (ii) how well they could embed the corresponding SDG indicators, and (iii) their potential to be localized [

40]. The Ministry of Planning and Development coordinated this exercise and submitted the tool as a good practice for the first open call. Next, the national government distributed 49 priority targets to each of the country’s 77 municipalities along with recommended actions to achieve them based on local contexts and issues [

41]. The General Directorate for the Coordination and Monitoring of the SDGs, a special task force established to coordinate efforts, then submitted that as a good practice for the second open call.

Governments took the initial lead in several other countries as well. Slovakia clustered SDGs around six national priorities with measurable outcome indicators integrated from the national to local levels and involving players in each stage [

42]. Costa Rica integrated SDGs into their national strategies and tools with open online citizen participation [

43]. Germany transferred SDGs to the local level by designing specific local objectives, targets, and indicators [

44]. The Guatemalan government provided local officials with advice and training to integrate the 2030 Agenda into local development plans [

45].

Some other examples of local (municipality-level) governments took the initiative. In Heidelberg city, Germany, the municipal Housing Action Program addressed some challenges of affordable housing, livable neighborhoods, and land-saving planning for starter households, families with children, and seniors [

46]. In Rwanda, the Masterplan 2050 of Kigali City integrated more equitable and flexible approaches to make informed decisions about effectively utilizing the city's resources [

47]. The municipal reforestation program of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil built “a natural barrier contributes to the reduction of landslides, creating resilience, and providing a better quality of life for its citizens” [

48] (p. 1).

UN entities became much more active within the second open call than in the first open call, increasing good practices submitted from 23 to 36.

That increase may have happened due to the urging of UN Secretary-General António Guterres

, who called for “ambitious actions by all stakeholders” because the “global efforts to date have been insufficient to deliver the change we need, jeopardizing the Agenda’s promise to current and future generations” [

49]

(p. 2). The call launched a “decade of action,” an initiative to strengthen existing efforts in addressing SDGs [

50]

. UN entities and affiliates led many such efforts relating to SDG 11. For example, in Indonesia, the World Meteorological Organization helped to enhance a coastal flooding forecast and early warning capability system [

51]. In Guinea-Bissau, UN-Habitat helped to improve the urban development plan of the city of Bissau [

52]. This initiative aimed at integrating the revision of Bissau’s urban development plan with national and global plans through a participatory approach to the most pressing challenges. In Nepal, the UN-Habitat supported the initiation of cleaning the debris and renovating the pond - De Pukhu, to create an open public space with traditional arts for women and youth [

53]. In Chad, UNESCO explored the Lake Chad Basin from biological shrinkage that pushed people to move out or join extremist groups [

54].

Private companies contributed 8.9% to the total number of good practices. Often these players contributed specific technologies and skills to SDG 11-related projects [

55]. Some examples include: in Austria, the planner company Arenas Basabe Palacios developed a residential block naturally integrated into the environment through the collaboration of all agents in this process [

56], Miyakoda Construction Co., Ltd. reconstructed an old wooden railroad station as a tourist attraction for a remote town in Japan [

57], and General Incorporated Association Oiden Sanson Center developed a partnership between farmers, hunters, and restaurants in Japan to control the population of wild boars and consuming their meat [

58].

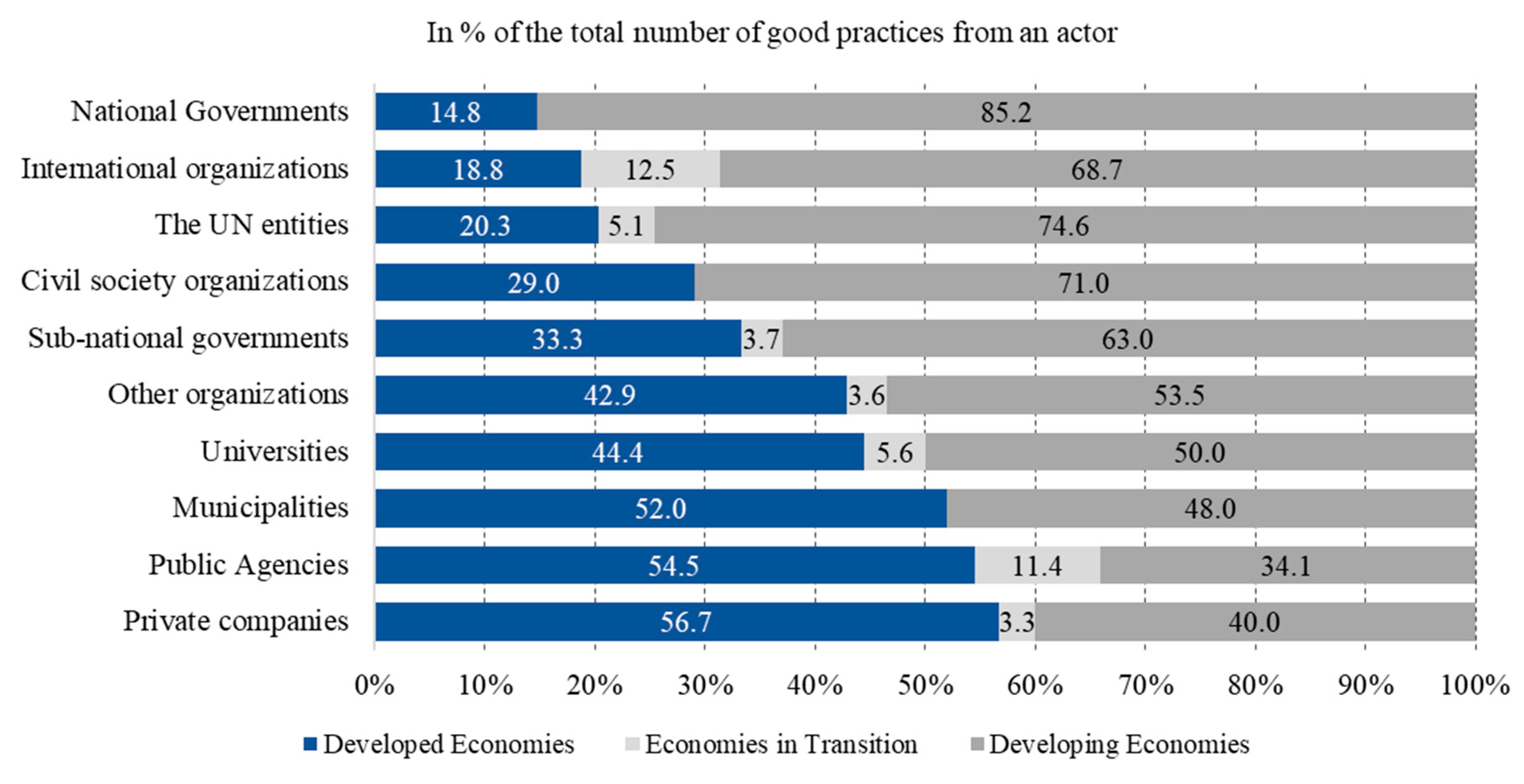

The contribution of actors varied by country because of their types of economies (

Figure 3).

Although the contribution of municipalities was almost equal between developed and developing countries, national and sub-national governments along with the UN entities, international institutions, and civil society organizations played a more active role in addressing SDG 11 in developing countries. This is to be expected given that the missions of these organizations are often to support developing nations. On the other hand, private companies and public agencies played an active role in the good practices of developed countries.

4.3. Progress toward SDG 11 Targets

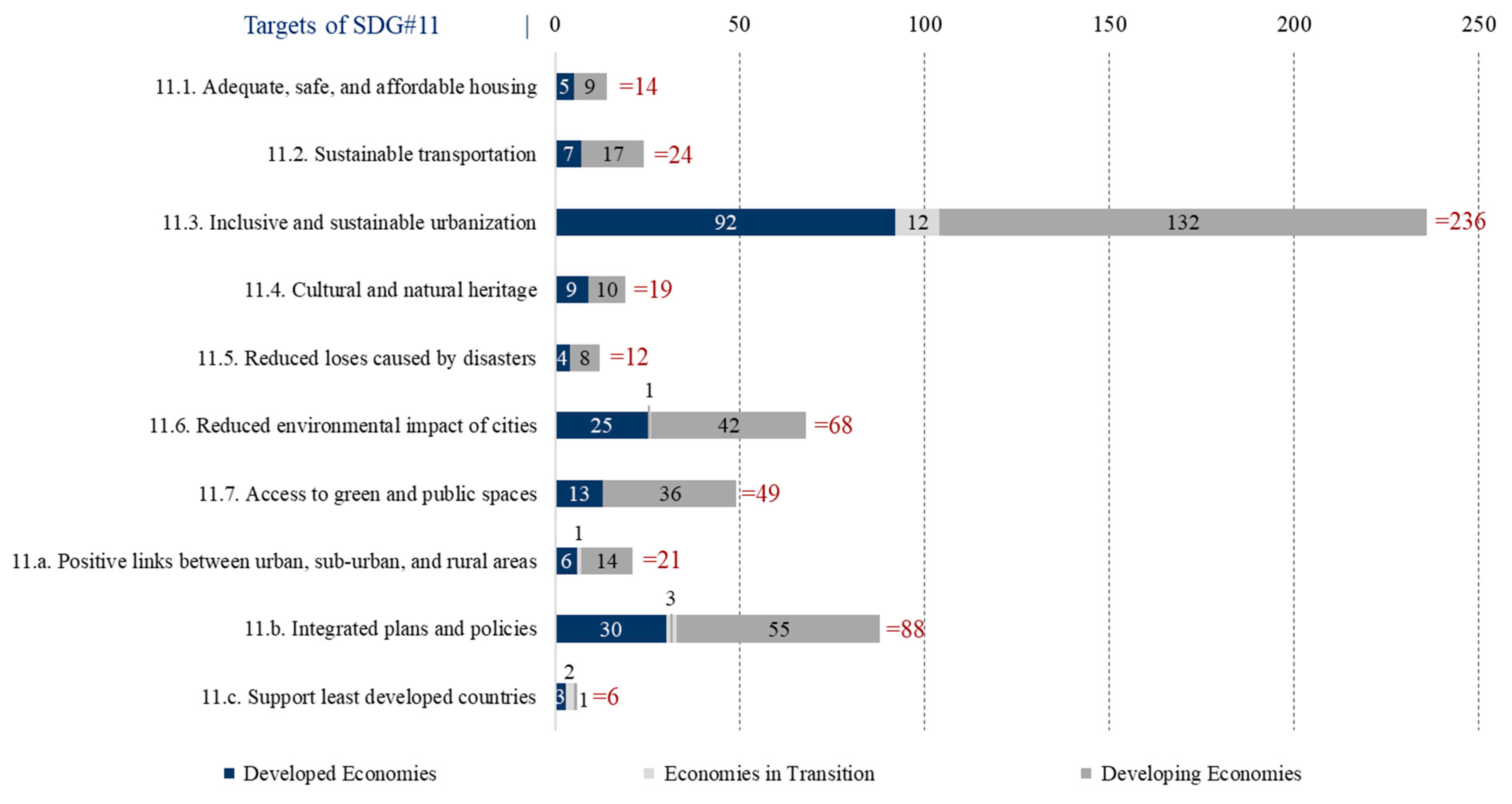

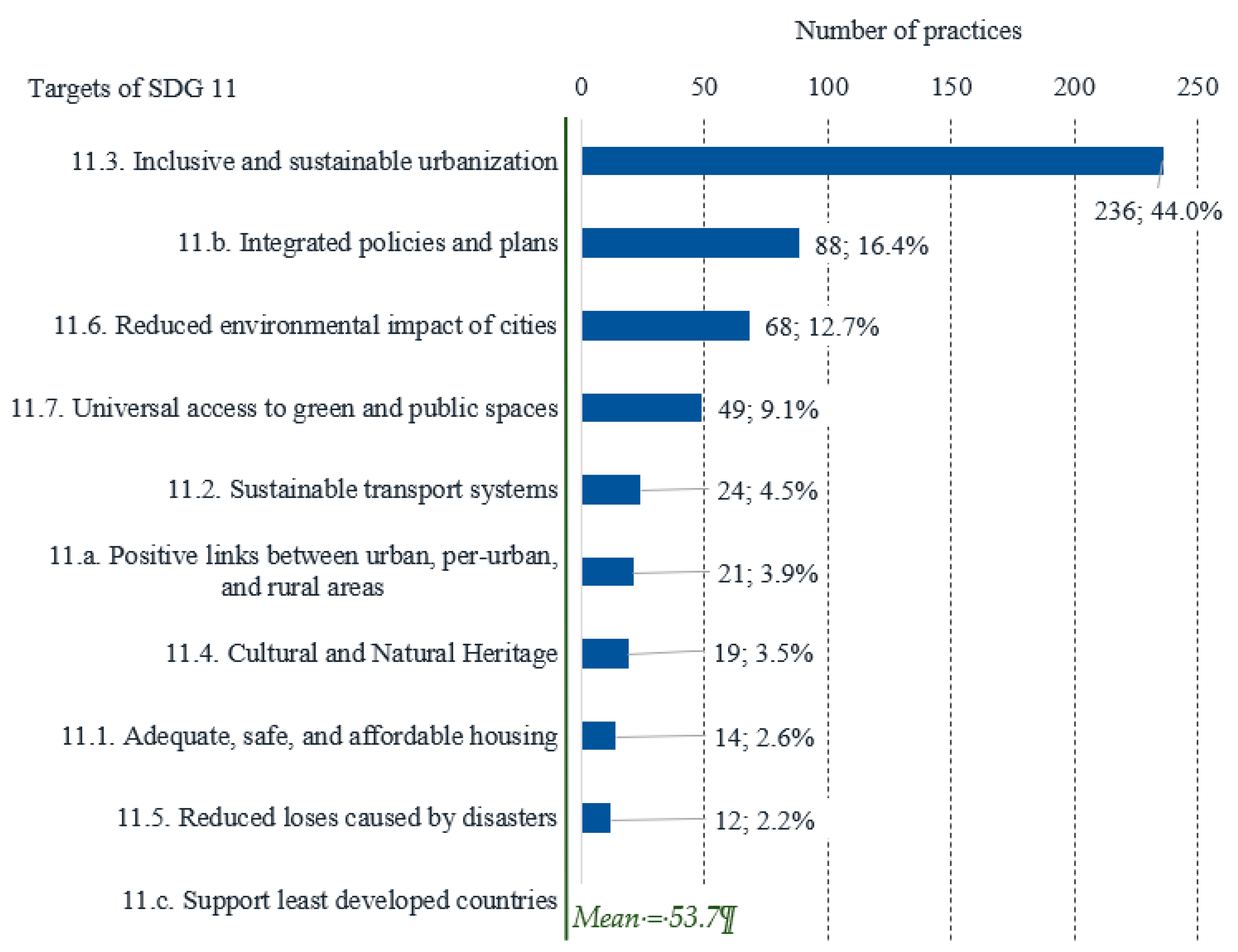

Good practices submitted to the UN emphasized some SDG 11 targets more than others (

Figure 4).

82% addressed SDG 11 targets of inclusive and participatory planning (11.3), integrated policies and plans (11.b), environmental impact (11.6), and safe and inclusive green and public spaces (11.7). In contrast, relatively few addressed targets related to supporting least developed countries (11.c), reducing the damage from disasters (11.5), and adequate, safe, and affordable housing (11.1). We note that the same order of targets is maintained between developed and developing countries in the distribution of good practices by targets of SDG 11 and types of economies (Appendix 2).

During the second open call, the number of good practices addressing sustainable urban planning, including resource efficiency, adaptation to climate change, and resilience to disasters (11.b) increased, while the number of good practices addressing sustainable transport systems (11.2), protecting natural and cultural heritage (11.4), and affordable and safe housing (11.1) fell. This may reflect a growing concern with climate topics. In general, linking specific projects to SDG 11 targets is difficult. The UN targets are expressed in language that is often vague and overlaps categories; targets 11.3, 11.b, and 11.6 could include almost any topic related to sustainable urban development. Because of these problems, the current set of targets seems widely disregarded. For example, Koch and Krellenberg [

59] (p. 1) report that “

only a few of the original targets and indicators for SDG 11 are used in the German context.”

4.4. Topical Areas of Implementation of Good Practices

We distributed good practices among 28 categories developed from the review based on their prime focuses (Appendix 1). Not surprisingly, most addressed planning (18.4%), inclusiveness (15.6%), capacity building (11.9%), and management (11.9%). However, while progressing from the first open call to the second open call the focus of many good practices shifted from planning to actions. Most of the good practices from the second open call addressed inclusiveness (21.9%), capacity building (20.0%), a healthier environment (10.6%, including carbon emission and other climate-change-related issues), and management (9.4%), and only 7.5% addressed planning.

Although the list of areas of implementation is relatively inclusive, a couple of areas were notably lacking. None of the best practices specifically mentioned environmental justice or climate change. This is likely because best practices related to these topics were submitted under other UN SDG Goals, and may mean that reporting of such areas needs to be better linked to SDG 11.

When we disaggregated good practices by focus areas and actors, we found that governments, public agencies, and civil society organizations most often addressed planning and management (73% of practices in each group). Civil society organizations, private companies, and public agencies addressed reducing waste most often (84.6% of practices cumulatively), far more than municipalities (7.7%) and governments at the national and sub-national levels (no practices). UN entities, civil society organizations, and universities contributed almost half of the good practices in capacity building (47.9%). International organizations submitted the highest portion of good practices in wildlife protection (42.9%). UN entities, international organizations, and universities contributed all of the good practices in disaster control.

Considering the distribution of focus areas addressed by each actor, we found that civil society organizations most often addressed the issues of inclusiveness (24.4% of practices) and planning (15.4%). In turn, the UN entities most often addressed inclusiveness (18.8%) and capacity building (15.9%).

Some clustering occurred in the distribution of focus areas by the types of economies. In particular, developing countries contributed around 95% of good practices addressing access to green and public spaces, 83% in disaster control, and 80% in water supply. Developing countries also submitted all the good practices addressing human rights, transportation, energy, infrastructure, sport, and technology. On the other hand, developed countries contributed the majority of good practices addressing wildlife conservation (57.4%), food supply (54.5%), and air quality (50.1%). Thus, questions arise around prioritization of the most pressing issues between developing and developed countries. All issues should ideally be addressed by both. It is perhaps natural that developing countries should prioritize issues connected with basic infrastructure and services, but reasons for other priority differences are less clear, and more research may be needed to determine why countries at different points of economic development have these different foci.

The good practices of developed countries were usually more process-oriented and technology-based than those of developing countries. Usually, they provide system-forming and data-driven tools to help solve the problems of global concern or cover gaps in knowledge and policy rather than directly resolve specific issues. For example, the Urban Data Platform of the European Commission collected data on 60 indicators from about 800 urban areas across Europe to support decision-making with information on indicator status and trends [

60]. To support regional actors in SDG implementation, the German Council for Sustainable Development, an advisory board to the Federal Government, organized four Regional Hubs for Sustainability Strategies to link SDG-related activities across governmental entities by sharing knowledge, experience, and data. The Federal Government provides 17 million euros to support such communication “in a manner which is otherwise virtually impossible in a federal state” [

61] (p, 1).

Conversely, actors from developing countries usually focused their good practices on problems of day-to-day concern (a problem-solving approach). For example, one project in India intended to make a local river free of solid waste and disease-causing microorganisms. Volunteers and students led by a civil society organization removed over 300 tons of garbage from the river bed and planted 1,000 trees on the riverside, improving the habitat for 130 bird species [

62]. In Brazil the Travessia (Crossing) program provided door-to-door transportation to more than 2,000 residents with special needs in 28 municipalities, allowing them to access education, health, work, and leisure services [

63]. In Mexico the International Fund for Animal Welfare launched its “Casitas Azules” program to help community members keep their dogs and the surrounding wildlife safe, distributing dog houses and predator-free chicken coops to disadvantaged households [

64].

4.5. Scale of Action

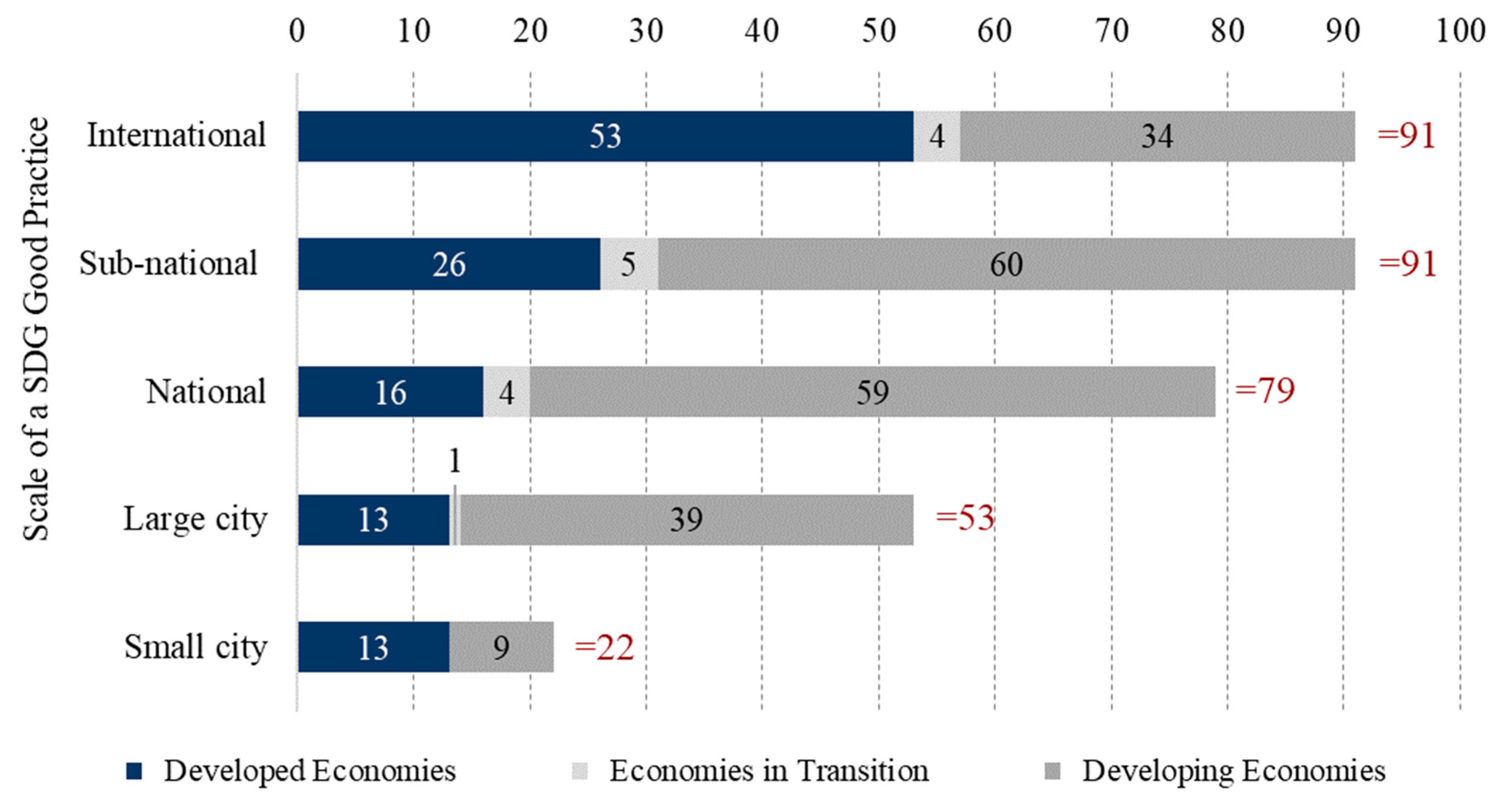

Most good practices addressed SDG 11 at international (27.1%), national (27.1%), and regional levels (23.5%). The number of good practices with international effects significantly increased in the second open call (likely because of the general increase in good practices from UN entities), while the number of good practices with impacts exclusively on the municipal scale decreased from 55 to 20. In part, this may be because UN entities most often addressed SDG 11 in ways that had international, national, and sub-national impacts, whereas civil society organizations addressed SDG 11 at more local scales.

The distribution of good practices by the scale of coverage and types of economies demonstrated that developing countries mainly submitted good practices at regional and national levels and large cities. Developed countries realized good practices at an international scale, and they addressed a small number of good practices at large and small city levels (

Figure 5).

In addition, we analyzed the distribution of good practices by scale and actors (

Table 2).

Public agencies contributed the most to international-scale actions (to some extent, because of the European Commission and its bodies). In turn, municipalities and private companies developed almost 60% of good practices addressing SDG 11 in small cities. Likely, local authorities and agencies in charge of the SDGs implementation considered those challenges best fit the municipal scale. They did not count this local scale as a part of efforts in line with a global guideline for peace and prosperity for people and the planet (the 2030 Agenda).

On the other hand, the fastest-growing urban agglomerations today are cities with fewer than one million inhabitants. Thus, we expect that the number of good practices related to the contexts of large and small cities will grow in an ongoing “decade of action,” and the focus gradually shift from a “big picture” to more local and specific practices.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Our study revealed multiple patterns within SDG 11 good practice submissions collected during the first two UN open calls.

First, although a majority of good practices were submitted by developing countries, only 55 of 140 such nations made submissions. These countries face large urban sustainability challenges and usually have fewer resources available than more developed nations because of the legacies of colonialism and imperialism. Efforts are needed by the global community (especially historically colonizing nations) to fund and support SDG 11 efforts in developing countries, including assisting with data collection and knowledge sharing.

Second, only 33 countries (17.1% of those that approved the 2030 Agenda) submitted SDG 11 good practices during both open calls. This seems to indicate that a relatively small number of countries continuously address SDG 11 and prioritize sharing their experiences. The corollary recommendation would be to improve the visibility of UN calls, support the implementation and evaluation of SDG 11 programs, and reward those countries that initiate these programs and participate in the global sharing of information.

Third, public sector agencies submitted the most SDG 11 good practices, which is to be expected given that governments have the most direct mandate to improve urban sustainability. However, the percentage of good practices submitted by the public sector was much larger in developing countries than in developed ones, where private companies, universities, and other organizations played a larger role. This may reflect a stronger civil society and more active private sector in developed countries, but it may also imply the need for governments in wealthy nations to take SDG 11 more seriously as a centerpiece of urban policy.

Fourth, good practices most frequently addressed SDG 11 targets of inclusive and participatory planning (11.3), integrated policies and plans (11.b), environmental impact (11.6), and safe and inclusive green and public spaces (11.7). Relatively few addressed issues of affordable and safe housing (11.1) and sustainable transport (11.2). The latter targets are written to emphasize social equity dimensions, and equity-related dimensions of SDG 11 such as affordable housing likely need greater emphasis worldwide. That being said, many SDG 11 cover a broad scope of issues and arguably lack focus, and we recommend that follow-on UN frameworks improve targets’ wording and focus.

Fifth, after a detailed disaggregation of good practices by focus area, we found that most addressed issues of planning, inclusiveness, capacity-building, and management (about 58% of good practices cumulatively, out of 28 categories). At their best, such tools increase societies’ ability to solve problems of global concern. Such ability is particularly needed in the developing world, which had less emphasis on these focus areas. However, a focus on tools can also distract from efforts for on-the-ground change as participants undertake process studies, model-building, theory production, and speculative technology development. Given the urgent need for action on climate and sustainability, it would seem important for all types of projects to focus as directly as possible on changing conditions.

Finally, most good practices addressed issues in ways that had international, national, or regional impacts. This would seem generally positive, given that urban sustainability issues extend globally—a sign that “thinking globally and acting locally” is becoming a more common practice worldwide.

Overall, both open calls of the UN can be seen as producing much useful data related to SDG 11. However, response rates were relatively low, particularly from developing countries, and the level of detail in individual responses varied widely. Some submissions contained sufficient details for analyses, while others just superficially described the initiatives. For example, those submissions did not include information about (i) implementation of the project/activity; (ii) results/outputs/impact; (iii) enabling factors and constraints; (iv) sustainability and replicability. Also, we noted previously that UN staff may have placed submissions emphasizing environmental justice or climate change under other SDGs; these may need to be better linked to SDG 11 since they also affect cities. Our analysis points to the need for better and more systematic reporting on SDG implementation globally, more focus on SDG 11 dimensions related to social equity, and a more active public sector role in implementing and reporting on the SDGs in developed countries.

As follow-on research further evaluation of specific good practices through in-depth case study methods would be useful to both scholars and practitioners. Another promising area of research would clarify relationships between SDG 11 and its targets to enhance planning, monitoring, and progress evaluation (this would likely be useful for all SDGs). Finally, we suggested that clarifying the classification, selection, and systematization criteria of good practices within further open calls would contribute to a shared understanding of SDG implementation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W., J.L., N.B. and G.N.; methodology, S.W., J.L., N.B., and G.N; formal analysis, S.W., J.L., N.B. and G.N; investigation, S.W., J.L., N.B., and G.N.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W., J.L., N.B. and G.N.; writing—review and editing, S.W., J.L., N.B. and G.N.; visualization, S.W., J.L., N.B. and G.N; supervision, S.W., J.L., and N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The Distribution of the Submitted Practices by Focus Areas

| ## |

Focus Area |

First Open Call |

Second Open Call |

Both Open Calls |

| Number of practices |

% of the total |

Number of practices |

% of the total |

Number of practices |

% of the total |

| 1 |

Planning |

62 |

25.5% |

12 |

7.5% |

74 |

18.4% |

| 2 |

Management |

33 |

13.6% |

15 |

9.4% |

48 |

11.9% |

| 3 |

Inclusiveness |

28 |

11.5% |

35 |

21.9% |

63 |

15.6% |

| 4 |

Raising awareness |

22 |

9.1% |

5 |

3.1% |

27 |

6.7% |

| 5 |

Capacity building |

16 |

6.6% |

32 |

20.0% |

48 |

11.9% |

| 6 |

Reducing wastes |

11 |

4.5% |

2 |

1.3% |

13 |

3.2% |

| 7 |

Healthier environment |

10 |

4.1% |

17 |

10.6% |

27 |

6.7% |

| 8 |

Green/public spaces |

10 |

4.1% |

9 |

5.6% |

19 |

4.7% |

| 9 |

Housing |

9 |

3.7% |

1 |

0.6% |

10 |

2.5% |

| 10 |

Wildlife |

7 |

2.9% |

- |

0.0% |

7 |

1.7% |

| 11 |

Disaster control |

5 |

2.1% |

1 |

0.6% |

6 |

1.5% |

| 12 |

Tourism |

5 |

2.1% |

4 |

2.5% |

9 |

2.2% |

| 13 |

Water supply |

4 |

1.6% |

6 |

3.8% |

10 |

2.5% |

| 14 |

Volunteering |

3 |

1.2% |

2 |

1.3% |

5 |

1.2% |

| 15 |

Transportation |

3 |

1.2% |

- |

0.0% |

3 |

0.7% |

| 16 |

Human rights |

2 |

0.8% |

2 |

1.3% |

4 |

1.0% |

| 17 |

Cultural heritage |

2 |

0.8% |

1 |

0.6% |

3 |

0.7% |

| 18 |

Infrastructure |

2 |

0.8% |

- |

0.0% |

2 |

0.5% |

| 19 |

Air quality |

2 |

0.8% |

- |

0.0% |

2 |

0.5% |

| 20 |

Energy |

1 |

0.4% |

- |

0.0% |

1 |

0.2% |

| 21 |

Sports |

1 |

0.4% |

- |

0.0% |

1 |

0.2% |

| 22 |

Technology |

1 |

0.4% |

- |

0.0% |

1 |

0.2% |

| 23 |

Food supply |

1 |

0.4% |

10 |

6.3% |

11 |

2.7% |

| 24 |

Healthcare |

1 |

0.4% |

- |

0.0% |

1 |

0.2% |

| 25 |

Education |

1 |

0.4% |

- |

0.0% |

1 |

0.2% |

| 26 |

COVID |

- |

0.0% |

4 |

2.5% |

4 |

1.0% |

| 27 |

Public Safety |

- |

0.0% |

1 |

0.6% |

1 |

0.2% |

| 28 |

International Development |

1 |

0.4% |

1 |

0.6% |

2 |

0.5% |

| In Total |

243 |

100.0% |

160 |

100.0% |

403 |

100.0% |

Appendix B

The Distribution of Good Practices by the Targets of SDG 11 and Types of Economies

References

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 68% of the world population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, says UN. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html (accessed on 23/08/2023).

- United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 07/08/2022).

- Sustainable Development Solution Network. Sustainable Development Report 2023. Implementing the SDG Stimulus. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2023/sustainable-development-report-2023.pdf (accessed on 10/08/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division. Sustainable Development Goals Progress Chart 2022. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/Progress-Chart-2022.pdf (accessed on 10/08/2022).

- Satterthwaite, D. A new urban agenda? Environment and Urbanization 2016, 28, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. SDG Good Practices. The First Open Call. SDGs Knowledge Platform. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnerships/goodpractices (accessed on 10/02/2021).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. SDG Good Practices. The Second Open Call. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/action-networks/good-practices-second-call (accessed on 8/02/2022).

- Krellenberg, K.; Bergsträßer, H.; Bykova, D.; Kress, N.; Tyndall, K. Urban sustainability strategies guided by the SDGs - A tale of four cities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, F.; Krellenberg, K.; Reuter, K.; Libbe, J.; Schleicher, K.; Krumme, K.; Kern, K. How can the Sustainable Development Goals be implemented? Challenges for cities in Germany and the role of urban planning. DISP 2019, 55, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Córdoba, P.J.; Amor-Esteban, V.; Benito, B.; García-Sánchez, I.M. The commitment of Spanish local governments to Sustainable Development Goal 11 from a multivariate perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, G.; Chauhan, S.S.; Varma, R. Challenges of localizing sustainable development goals in small cities: Research to action. IATSS Research 2021, 45, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhai, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Kang, S. Analysis on synergies and trade-offs in green building development: From the perspective of SDG 11. Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment 2019, 17, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, D.B.; Iyer, S.D. Introduction: Localizing SDGs and Empowering Cities and Communities in North America for Sustainability. In Promoting the Sustainable Development Goals in North American cities: Case studies & best practices in the science of sustainability indicators, 1st ed.; Abraham, D.B., Iyer, S.D., Eds.; Springer, Cham: Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.H.; Amjad, M.; Qamar, A.; Asim, M.; Mahmood, W.; Khalid, W.; Rehman, A. Nexus implementation of sustainable development goals (SDGs) for sustainable public sector buildings in Pakistan. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 52, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.; Reis, R.M.; Gaivizzo, L.H.B.; Litre, G.; Rodrigues Filho, S.; Saito, C.H. Scaling up SDGs Implementation: emerging cases from state, development and private sectors. In The contribution of community-based recycling cooperatives to a cluster of SDGs in semi-arid Brazilian peri-urban settlements, 1st ed.; Nhamo, G., Odularu, G., Mjimba, V., Eds.; Springer, Cham: Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, A.C.; Smart, J.C.; Davey, P. Can learned experiences accelerate the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 11? A framework to evaluate the contributions of local sustainable initiatives to delivery SDG 11 in Brazilian municipalities. European Journal of Sustainable Development 2018, 7, 517–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, S.M. Reimagining Sustainable Cities: Strategies for Designing Greener, Healthier, More Equitable Communities, 1st ed.; University of California Press; Oakland, USA, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 1–249. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Reimagining_Sustainable_Cities/mM1DEAAAQBAJ? Available online: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Reimagining_Sustainable_Cities/mM1DEAAAQBAJ?

- Bartniczak, B.; Raszkowski, A. Implementation of the Sustainable Cities and Communities Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) in the European Union. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, F.; Daniel, J.; Jackson, L.; Neale, A. Earth observation-based ecosystem services indicators for national and subnational reporting of the sustainable development goals. Remote Sensing of Environment 2020, 244, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liang, D.; Sun, Z.; Chen, F.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Bian, J.; Wei, Y.; Huang, L.; <named-content content-type="background:red">Chen, Y. ; Peng, D.; Li, X.; Lu, S.; Liu, J.; Shirazi, Z. Measuring and evaluating SDG indicators with Big Earth Data. Science Bulletin 2022, 67, 1792–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirasteh, S.; Varshosaz, M. Geospatial information technologies in support of disaster risk reduction, mitigation and resilience: Challenges and recommendations. In Sustainable Development Goals Connectivity Dilemma, 1st Ed.; Rajabifard, A., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilino, M.; Tarantino, C.; Adamo, M.; Barbanente, A.; Blonda, P. Earth observation for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 11 indicators at local scale: Monitoring of the migrant population distribution. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Liu, B.; Duan, Z.; Yang, W. Measuring local progress of the 2030 agenda for SDGs in the Yangtze River Economic Zone, China. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2022, 24, 7178–7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunluk-Senesen, G. Wellbeing gender budgeting to localize the UN SDGs: Examples from Turkey. Public Money & Management 2021, 41, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, J.; Ivan, K.; Török, I.; Temerdek, A.; Holobâcă, I.H. Indicator-based assessment of local and regional progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): An integrated approach from Romania. Sustainable Development 2021, 29, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, K.; Yamada, T. A framework to assess the local implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 11. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 84, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisheim, M.; Ellersiek, A.; Goltermann, L.; Kiamba, P. Meta-governance of partnerships for sustainable development: Actors’ perspectives from Kenya. Public Administration and Development 2018, 38, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, S.C.; Simon, D.; Croese, S.; Nordqvist, J.; Oloko, M.; Sharma, T.; Taylor Buck, N.; Versace, I. Adapting the sustainable development goals and the New Urban Agenda to the city level: Initial reflections from a comparative research project. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 2019, 11, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozhenkova, V.; Allmang, S.; Ly, S.; Franken, D.; Heymann, J. The role of comparative city policy data in assessing progress toward the urban SDG targets. Cities 2019, 95, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Z.; Greyling, S.; Simon, D.; Arfvidsson, H.; Moodley, N.; Primo, N.; Wright, C. Local responses to global sustainability agendas: learning from experimenting with the urban sustainable development goal in Cape Town. Sustainability science 2017, 12, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfvidsson, H.; Simon, D.; Oloko, M.; Moodley, N. Engaging with and measuring informality in the proposed urban sustainable development goal. African Geographic Review 2017, 36, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsey, H.; Thomson, D.; Lin, R.; Maharjan, U.; Agarwal, S.; Newell, J. Addressing inequities in urban health: Do decision-makers have the data they need? Urban Health 2016, 93, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Khalid, A.; Sharma, S.; Kunar Dubey, A. Concerns of developing countries and the sustainable development goals: Case for India. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology 2020, 28, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; Arfvidsson, H.; Anand, G.; Bazaz, A.; Fenna, G.; Foster, K.; Jain, G.; Hansson, S.; Evans, L.M.; Moodley, N.; et al. Developing and testing the urban sustainable development goal’s targets and indicators – a five-city study. Environment and Urbanization 2015, 28, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šilhankova, V.; Pondelicek, M.; Struha, P. Agenda 2030, Sustainable Cities and its Indicators. In 20th International Colloquium on Regional Sciences, Kurdějov, 14–16 June; Klímová, V., Žítek, V., Eds.; Brno: Masarykova univerzita, 2017; pp. 506–512. Available online: https://is.muni.cz/do/econ/soubory/katedry/kres/4884317/Sbornik2017.pdf#page=506.

- Hansson, S.; Arfvidsson, H.; Simon, D. Governance for sustainable urban development: The double function of SDG indicators. Area Development and Policy 2019, 4, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S.; Cao, C.; Fatima, K.; Najmuddin, O.; Acharya, B. Landscape greening policies-based land use/land cover simulation for Beijing and Islamabad - An implication of sustainable urban ecosystems. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Economic Situation and Prospects 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/WESP2019_BOOK-ANNEX-en.pdf (accessed on 10/08/2022).

- Langan, M. The UN Sustainable Development Goals and Neo-Colonialism. In Neo-Colonialism and the Poverty of' Development in Africa. Contemporary African Political Economy, 1st ed.; Sahle, E.N., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2017, Volume 1, pp. 177–205. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10. 1007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Measuring the impact of ministerial programs on the SDGs. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/measuring-impact-ministerial-programs-sdgs (accessed on 08/07/2022).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Specialization of SDG Priority targets in Benin. SDG Good Practices: The Second Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/spatialisation-des-cibles-prioritaires-des-odd-au-benin (accessed on 07/10/2022).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Six national priorities towards implementation of the 2030 Agenda. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/six-national-priorities-towards-implementation-2030-agenda (accessed on 17/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. National development plan with SDGs contribution and formulated with public participation. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/national-development-plan-sdgs-contribution-and-formulated-public-participation (accessed on 10/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Globally sustainable municipalities in North-Rhine Westphalia - developing 15 integrated municipal sustainability strategies to localize the SDGs. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/globally-sustainable-municipalities-north-rhine-westphalia-developing-15-integrated (accessed on 17/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. National priorities for development in territories. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/national-priorities-development-territories (accessed on 17/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Ten points for implementing the housing action program. SDG Good Practices: The Second Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/10-points-implementing-housing-action-program-short-10-points-housing (accessed on 17/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Kigali city Masterplan 2050. SDG Good Practices: The Second Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/kigali-city-masterplan-2050 (accessed on 7/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Rio de Janeiro reforestation program. SDG Good Practices: The Second Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/rio-de-janeiros-reforestation-program-refloresta-rio (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/ (accessed on 10/08/2022).

- United Nations Sustainable Development Group. Decade of Action. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/2030-agenda/decade-action (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Coastal flooding forecast strengthened in Indonesia. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/coastal-flooding-forecast-strengthened-indonesia (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. BISSAU 2030: integrating the sustainable development goals into Bissau’s urban development plan. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/bissau-2030-integrating-sustainable-development-goals-bissaus-urban-development-plan (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Revitalization of the open public space – De Pukhu, Bungamati. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/revitalization-open-public-space-sdg-117-de-pukhu-bungamati (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Biosphere and heritage of the lake Chad. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/biosphere-and-heritage-lac-chad-biopalt (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The private sector and the SDGs: the need to move beyond “Business as Usual. ” Sustainable Development 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Wildgarten Quartier. An innovative, ecological and democratic neighborhood in Vienna, Austria. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/wildgarten-quartier-innovative-ecological-and-democratic-neighborhood-vienna-austria (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Revitalization of region spreading from renovation of the station building. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/revitalization-region-spreading-renovation-station-building (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Toyota wild boar meat curry. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/toyota-wild-boar-meat-curry (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- Koch, F.; Krellenberg, K. How to contextualize SDG 11? Looking at indicators for sustainable urban development in Germany. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2018, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Urban data platform. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/urban-data-platform (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Regional Hubs for sustainability strategies (RENN): building bridges for Agenda 2030 implementation in Germany. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/regional-hubs-sustainability-strategies-renn-building-bridges-agenda-2030 (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Giving life to ecosystem of Indian river: case of Swachh Sabarmati (cleaning river Sabarmati in Gujarat). SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/giving-life-ecosystem-indian-river-case-swachh-sabarmati-cleaning-river-sabarmati (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Program Travessia (Crossing): make cities inclusive, resilient, sustainable. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/program-travessia-crossing-connected-sdg-11-make-cities-inclusive-resilient (accessed on 11/01/2023).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Casitas Azules (little blue houses) – SDG 3, SDG 8, SDG 11, SDG 12, SDG 13, SDG 15. SDG Good Practices: The First Open Call Database. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/casitas-azules-little-blue-houses-sdg-3-sdg-8-sdg-11-sdg-12-sdg-13-sdg-15 (accessed on 11/01/2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).