1. Introduction

In 2015, 193 UN member states adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, featuring 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aimed at addressing pressing global concerns such as poverty, social well-being, and environmental degradation. This joint commitment implies the emergent need to integrate various policy fields, posing a significant challenge for both policy-making and societal development. Given the central role of governments in galvanizing transformative action, the national level is critical for analyzing integrated implementation and assessing the impact of the 2030 Agenda [

1,

2]. Extensive research shows that mid-term efforts to achieve the SDGs have done little to alter the trajectory of adverse development trends. In fact, progress on the SDGs often correlates with increased ecological footprints and negative spillover effects, highlighting the urgent need to accelerate action and prioritize environmental goals to safeguard Earth's life-support systems within SDG implementation e.g., [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Successfully applying the core principles of the SDGs—indivisibility, integration, and universality—requires new approaches to policymaking and public administration, along with a strengthened role for science. However, introducing related changes often poses new demands on national decision-making and scientific systems, requiring a broad set of capacities and skills at individual, institutional, and network levels [

7,

8,

9]. In this context, capacity development is a critical area that deserves greater attention.

Despite recognizing the importance of capacity-building in both the Global South and North e.g., [

10,

11,

12], SDG Target 17.9 on means of implementation remains largely focused on developing countries. While governments are urged to prioritize investments in domestic capacity-building [

9], a deeper understanding of the distinct governance needs and multidimensional nature of required capacities remains essential [

1]. This is key to guiding more effective capacity assessments and capacity-building measures, especially in countries with limited capacity in sustainability policy. Previous work suggested a general direction of the conditions for improving policy coherence, highlighting relevant cognitive and analytical capacities alongside institutional arrangements within the SDG context [

13,

14]. However, the changing role of science in national and SDG-related governance has not received sufficient attention in these discussions. To address this problem area, the paper integrated perspectives from environmental politics and sustainability governance to draw important implications for the governance mode and cross-cutting capacities essential for advancing national SDG implementation. The identified analytical categories are applied to Bulgaria and Romania—two representative countries from the EU’s Eastern enlargement, often ranked among those with the weakest state capacities and occupying some of the lowest positions in the EU in terms of progress toward achieving the SDGs by 2030 [

15,

16,

17,

18]. The study examines whether new capacities have been established at the midpoint of the 2030 Agenda, comparing SDG implementation approaches and governance conditions in Bulgaria and Romania.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 outlines an analytical framework for assessing domestic capacities, building on prior research on national governance and capacity building for SDG implementation, while integrating key insights from the literature on social learning and reflexive governance for global public goods. The reasoning for the case selection and qualitative methodology is described in

Section 3.

Section 4 presents the empirical findings from the national contexts of Bulgaria and Romania, while

Section 5 contextualizes these findings within existing literature and discusses their implications.

Section 6 draws conclusions on the usefulness of the proposed approach and gives an outlook for future research.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. UN 2030 Agenda: Initial Progress in Implementing the SDGs

Experience with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) showed that addressing economic development and environmental protection in isolation has led to gains in some socioeconomic indicators but worsened environmental problems, including climate change, resource depletion, and biodiversity loss [

19]. Following the MDGs, UN Member States adopted the SDGs in 2015, recognizing that poverty, human development, environmental change, and the planet’s carrying capacity are deeply interconnected and must be addressed holistically at the global level. Thus, the SDGs represent a historic shift in UN efforts to unify socio-economic concerns and environmental sustainability within a universal global agenda for sustainable development. Anchored in goal-setting, the agenda introduces a distinctive approach to shaping institutional arrangements and steering global governance. The Global Goals thus represent a governance model rooted in global inclusion and comprehensive goal-setting, characterized by their legally non-binding nature, reliance on the relatively weak High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development, and flexibility to accommodate national preferences and priorities [

8].

Halfway to 2030, SDG progress is falling short—only 15% of assessable targets are on track—highlighting major governance gaps [

20,

21]. Despite some positive discursive effects, the SDGs have had limited transformative impact, triggering political processes only sluggishly. Higher-income countries tend to score better, yet their success is often linked to externalizing social and environmental costs, with even top performers contributing to environmental degradation elsewhere [

6]. Recent European studies show that socioeconomic progress often negatively impacts the environment, underscoring the urgent need to strengthen efforts toward environmental sustainability to protect the planet’s life-support systems within SDG implementation [

4,

5]. The EU average on the SDG Index reveals stark regional disparities: Northern European countries score above 80%, while Eastern European nations average around 60%. In candidate countries, fewer than one-third of SDG targets have been met or are on track, highlighting significant regional gaps within Europe [

22].

2.2. Prior Work on National Governance and Capacities for SDG Implementation

The role of governance in achieving the SDGs is widely recognized; however, designing effective governance arrangements to facilitate the necessary transformations remains a complex challenge. This involves multiple scales and diverse actors [

14], with the development of human capacities and institutional frameworks as essential prerequisites [

23]. In recent years, a substantial body of literature has emerged addressing the need for an integrated approach that spans different governance levels and sectors. Debates persist over which governance dimensions and models should take priority, given the diverse goals and sometimes competing objectives within the SDG framework. Key challenges include defining integration, managing interlinkages in practice, and clarifying the role of science in supporting policy integration [

24]. Implementing the SDGs is generally associated with the need for countries to reorganize public administrations and policymaking systems in order to strengthen both horizontal coordination across sectors and vertical coordination across levels of government. In addition, further investment is required in strategic planning, innovation, and institutional capacities to manage conflicts, overcome systemic barriers, and respond effectively to crises [

9,

25].

In their analysis of 41 high- and upper-middle-income countries, Glass and Newig [

26] identify key governance factors influencing SDG progress, including

participation, policy coherence, reflexivity and adaptation, and

democratic institutions. They find that democratic institutions, public participation, economic power, education, and geographic location support SDG achievement, while policy coherence shows no clear impact on outcomes—likely due to implementation complexity and delayed effects. Building on previous work that discusses diverse governance approaches to sustainability transformations—including

polycentricity,

transitions management, and

adaptive,

reflexive,

anticipatory, and

transformative governance— four scales that define effective SDG governance have been identified, including

spatial,

jurisdictional, sectoral, and

temporal [

14].

While the Global Goals have incrementally influenced political processes, research on their steering effects has paid little attention to policy coherence and institutional integration. Despite limited evidence of progress, efforts in this respect include assigning coordination roles to central agencies, interdepartmental bodies, and occasionally to parliaments or advisory councils [

20,

27]. No institutional model has yet been empirically proven effective in addressing SDG implementation challenges.

In their analysis of Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs) from 137 countries, Breuer, Leininger [

28] examine how governments address policy coherence and integrated SDG implementation, considering different contextual factors. Using a four-dimensional typology, including

political leadership, horizontal and

vertical integration, and

stakeholder engagement, the scholars find that sustainability policy is rarely approached holistically and only a few countries meet all criteria. Implementation is typically led by foreign affairs and environment ministries, with limited public participation. While socio-economically advanced countries are more likely to establish cross-sectoral mechanisms, political regime type has little impact on institutional design choices.

Although lessons from environmental policy integration (EPI) provide valuable insights for advancing the global agenda, the SDGs are considered to reshape our understanding of the critical policymaking dimensions necessary for advancing EPI [

13,

29]. This shift is particularly evident in terms of political will and the normative framework, where all SDGs are prioritized equally, rather than granting ‘principled priority’ to environmental concerns over other goals. Still, human and institutional capacities—central to EPI—remain highly relevant within the SDG context. Cognitive and analytical capacities are particularly crucial for policy learning in EPI, involving

systems thinking,

generating (environmental) knowledge through advisory mechanisms, and

using tools like Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA).

Strategic foresight also plays a key role in anticipating long-term environmental challenges and analyzing plausible futures. Institutional arrangements seek to break down sectoral silos by adjusting procedures and promoting interdepartmental coordination through mechanisms such as

cross-departmental working groups,

consultations, and

EIA procedures. While a dedicated

task force is recommended, responsibility for advancing EPI is increasingly shifting from environment ministries to more influential bodies like finance or foreign affairs ministries, or even the

Minister’s or President’s Office [

13].

2.3. Rationale for Assessing Capacities for National SDG Implementation

2.3.1. The Role of Science for Sustainable Development and the UN SDGs

While discussions on SDG governance often emphasize institutional reform, the inclusion of new societal actors, and capacity-building, little attention has been given to processes of knowledge generation and their application within national political domains. Insights from governance research on sustainable development underscore the importance of understanding the roles of various actors and institutions, particularly the relationship between governance and knowledge production, two processes that have become increasingly intertwined [

30].

The contribution of scientific knowledge and expertise to environmental and sustainability governance is widely acknowledged as crucial across all levels - regional, national, and local [

8,

31,

32,

33,

34]. The role of science and research in advancing SDG implementation is also increasingly recognized, with science expected to serve as a ‘trusted advisor’ in aligning local targets with global thresholds and biophysical boundaries [

35]. Within the “indivisible and universal” normative SDG framework [

36], sustainability researchers are encouraged to: 1)

adopt interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary methods; 2) develop context-specific solutions with broader relevance; 3) support collaborative experimentation with stakeholders (e.g., SDG Labs); 4) integrate diverse knowledge forms—indigenous, policy-based, and academic and 5)

approach sustainability as an open-ended social learning process. Similarly, the UN Global Sustainable Development Report (2023) highlights the need for targeted capacity-building, including support for socially robust knowledge and strengthening the science-policy-society interface [

21]. This interface is seen as essential for navigating goal interactions, managing trade-offs and synergies, and setting priorities for the SDGs [

37].

In their review of science-based approaches to SDG implementation, Allen, Metternicht [

38] identify 22 expert-recommended strategies to support national efforts. These include methods for assessing SDG interlinkages and developing scenarios and transformation pathways—approaches that benefit from diverse expertise and perspectives in the scientific process. Their review of 56 countries' VNRs shows a growing use of science-based strategies, though progress is mostly limited to monitoring and evaluation. Despite advances in developing scientific tools for assessing SDG interlinkages, these methods remain largely absent from the official reports.

In the second half of SDG implementation, science is supposed to play a pivotal role in operationalizing the principles of indivisibility, integration, and universality through stronger collaboration with governments. Key action areas in this regard include [

7]: 1) conducting data-driven research on SDG interlinkages and creating accessible national databases; 2) linking the state of the environment with socio-economic progress, supporting SDG target 17.19 and the UN’s initiative “Beyond GDP”; 3) deepening understanding of biophysical boundaries and ecological footprints and their effects on human well-being; and 4) building capacity to analyze geographical spillovers through clearer concepts and improved tools, indicators, and data. Institutions promoting sustainable development should further prioritize knowledge brokering and diplomacy [

39]. In this connection, governments and research institutions must collaborate to establish open-access knowledge platforms in low- and middle-income countries, in order to integrate fragmented knowledge, evaluate transformation strategies, and support non-scientific actors in designing context-specific transformation pathways.

To reflect the developments in knowledge management and the changing role of science within normative frameworks on national governance and capacities, this work draws on recent literature about social learning and reflexive governance to examine their deeper implications for human capacities and knowledge-based institutional mechanisms in domestic systems.

2.3.2. Promoting Social Learning and Reflexive Governance in the Pursuit of the SDGs

Over the past decades, the political and institutional landscape of environmental and sustainability policy has undergone significant transformation, marked by increasingly complex interconnections and interdependencies among actors, governance levels, and policy instruments. Today, governance processes often involve not only governments but also businesses, civil society, and the scientific community, while modes of governance have expanded beyond traditional command-and-control approaches to include cooperation, learning, and voluntary compliance among state and non-state actors [

12,

30].

Unlike conventional environmental problems such as air and water pollution, which have relatively clear causes and effects, many of today’s most pressing challenges reflect transformed conditions. Issues like climate change, biodiversity loss, soil and groundwater contamination, hazardous chemical use, and urban sprawl—often referred to as ‘persistent’ or ‘creeping’ problems—represent a new type of long-term problems that traditional environmental policies have struggled to address effectively. These problems are characterized by slow, cumulative changes, high levels of complexity, and extended time frames, both for the emergence of impacts and for the development and implementation of effective solutions [

12,

40,

41]. Under these conditions, uncertainty has emerged as a defining feature of environmental problems and their related knowledge and policies. This uncertainty is particularly evident in the prognosis of environmental change and its potential consequences, the need to take political action on problems that may not yet be visible, and the unpredictable effects of policy decisions, inaction, or innovation [

40,

42,

43].

The SDG framework highlights several such environmental goals tackling persistent problems, including SDGs 13 (Climate action), 14 (Life below water), and 15 (Life on Land). Advancing sustainability, however, further requires navigating the trade-offs and interconnections among environmental, economic, and social goals. Thus, responding to the complexity, uncertainty, interconnectedness, and multi-level governance inherent in the SDG framework calls for a new approach that redefines the relationship between knowledge production and decision-making - a core factor of sustainability governance cf. [

30]. It is important to note that the concepts of institutional integration and policy coherence as used in the SDG context are rooted in rational decision-making principles within public policy and administration Candel & Biesbroek, 2016; Peters, 1998, as cited in [

27]. However, these approaches—often aligned with first-generation planning and New Public Management—are increasingly seen as inadequate for addressing the complex challenges of sustainable development and long-term environmental change [

44,

45]. Similarly, traditional governance patterns, based on regulation and market mechanisms, have proven insufficient for managing the problem characteristics defining sustainable development. In this context, scholars emphasize the need for a long-term perspective and reflexive governance approaches [

44,

45,

46].

Originating from discourses on the ecological and technological risks of industrialization, the concept of reflexive governance has become central in the field of environmental governance and sustainable development [

46,

47,

48]. It calls for critically reassessing specialized problem-solving in policy-making and social organization, which is often associated with unintended consequences like environmental degradation and systemic risks. Based on the assumption that only in deliberative and participatory processes can multiple interests, experiences, and visions be meaningfully conveyed and acknowledged, the necessity to introduce novel approaches for structuring and handling problems in society is highlighted.

The role of knowledge and processes for generating knowledge represent a core aspect of the reflexive mode of governance [

49]. In this context, social learning is treated as a key mechanism for enabling reflexive, long-term policymaking [

45,

46]. It is defined as “a process of change on a society level that is based on newly acquired knowledge, a change in predominant value structures, or of social norms which results in practical outcomes” [

30]. This process shows itself in the close interaction between science, policy and society actors in terms of producing and applying knowledge. Given the uncertainty surrounding environmental issues and their interconnections with social and economic challenges, existing knowledge must be continuously developed and integrated into policy goals and strategic frameworks. Therefore, the design and structure of the policy process may need to differ from traditional models. Within this perspective, social learning is understood as being “highly interrelated with the generation, construction and representation of scientific knowledge and the openness, flexibility and variety of the governance systems of collective decision making” [

30]. The role of science in this context is changing. While it has traditionally been perceived as an advisor of policy-makers, recent contributions suggest that there is no clear distinction between knowledge generation and decision-making processes; instead, they are interrelated and intermingled. This new perspective is grounded in well-established concepts, such as Mode-2 science [

50], co-production of knowledge [

51], sustainability science [

52], and post-normal science [

53,

54].

The outlined normative considerations have direct implications for the governance conditions required to translate the global ambitions of the 2030 Agenda (and beyond) into national contexts. Experiences with reflexive governance approches, such as transition management approach and long-term policy design, have shown the need to strengthen the capacities of societal groups and actors [

45,

55]. Thus, it remains further essential to determine the capabilities needed to design effective reflexive processes and institutions that enable societies and actors to acquire and apply relevant knowledge to both current and future actions. Building on recent literature on social learning and reflexive governance for sustainable development and global public goods, key cross-cutting capacity dimensions can be singled out, complementing prior insights on human and institutional capacities in the SDG context and guiding empirical analysis. With these capacities in place, national SDG implementation is expected to be more effective in advancing the transformative goals of the global agenda.

2.3.3. Resulting Implications for Domestic Capacities

Human dimension. The competencies and skills of key actors are considered a critical success factor for the effective organization and functioning of reflexive governance processes [

56]. Grothmann & Siebenhüner (2012) apply the concept of competence because it integrates key psychological factors—such as knowledge, cognition, and motivation—that are essential to the reflexive governance process and have practical applications for actor selection and training. In this context, competence is defined as “the ability to meet complex demands, by drawing on, mobilizing, and managing psychological resources – including knowledge, motivations, emotions, skills, attitudes, values and social support - in a particular context” [

56]. Making use of different governance approaches, the scholars distinguish between the key elements of reflexive governance, which is described as a

“rule-setting and rule-implementation process that includes interaction, deliberation and adaptation as areas of individual and collective behaviour” [

56]. These key areas of individual and collective behavior – interaction, deliberation and adaptation - are also seen as core competency domains essential for the functioning of any reflexive governance process [

56]. Interaction involves engaging both state and non-state actors in setting policy goals and implementing strategies, with key subcomponents including relating to others, cooperating, and managing conflicts. Deliberation, which emphasizes integrating diverse insights from science and practice through transdisciplinary learning, requires motivation to learn, the ability to understand and tolerate differing beliefs and values, and the capacity to handle complexity and find creative solutions. Adaptation refers to the iterative development of strategies and institutional responsiveness to new knowledge and developments, with key subcomponents including self-reflection, accepting failure as part of managing complex tasks, and identifying innovative solutions. Addressing specific problems, such as climate change adaptation, requires developing "uncertainty competence" tailored to the specific issue.

Knowledge-based institutional framework. Discussions on reflexive governance argue that coordinating heterogeneous actors should occur within networks, rather than institutionalized hierarchies, to facilitate exchange and learning between diverse participants [

48]. The literature points to research policy and the national research program for sustainable development, in particular, as an appropriate mechanism for enhancing reflexivity in society regarding established beliefs, norms, and priority goals of development strategies (ibid). This is viewed as a ‘tool for social learning’ [

30], providing a platform for interaction between science (both natural and social science) and society to generate problem and solution-oriented knowledge. However, designing such a program, which seeks to cross traditional boundaries of knowledge production and decision-making, presents novel challenges for scientific work compared to traditional modes of scientific activities and research organization. The main challenges include involving practitioners in processes of knowledge generation and implementation (transdisciplinarity); engaging scientific actors in decision-making processes (active policy integration); recognizing the normative role of science and sustainable development in shaping society within environmental constraints (normativity), creating open and learning-oriented policy systems (learning), and connecting knowledge generation processes to relevant domains and contexts to address global problems (international approach) [

30].

3. Research Approach and Methods

While capacity building for sustainable development is increasingly relevant to all countries, this empirical analysis focuses on Bulgaria, with comparisons to Romania. Bulgaria was selected for pragmatic reasons, particularly due to data availability and its suitability for comparison with countries that share similar background conditions from the EU’s Eastern enlargement cf. [

57]. Romania, in turn, is appropriate for this comparative analysis given its geographical proximity to Bulgaria, shared experiences under communist rule, and joint EU accession in 2007. Extending the single case study to Romania will help identify similarities and differences, as well as highlight best practices.

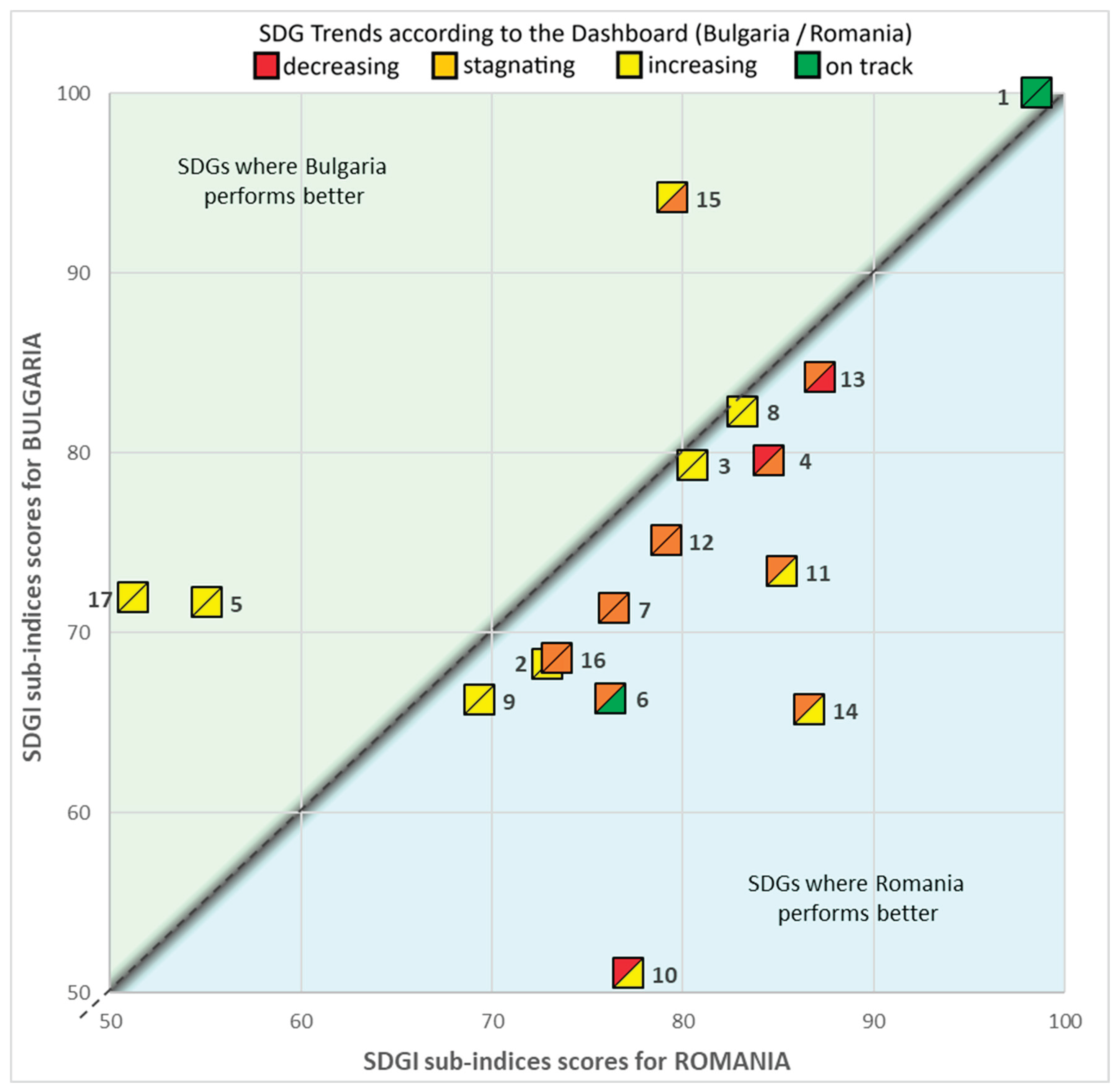

Both countries face similar challenges, including economic underdevelopment, demographic decline, and EU scrutiny regarding corruption and judicial reform. While these countries are often compared on economic indicators such as GDP growth, unemployment, and foreign investment, they are rarely examined in terms of sustainability governance capacities. A closer examination of SDG progress based on SDG Index and Dashboards, illustrated in

Figure 1, shows that Romania outperforms Bulgaria on most goals, except for Goals 5 (Gender equality), 15 (Life on Land), and 17 (Partnerships for the goals). Despite this, the overall prospects for achieving the SDGs by 2030 remain concerning. Only Goal 1 (No Poverty) is on track in both countries, with Romania also making very good progress towards Goal 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation).

An assessment of the state of SDG achievement in Bulgaria, based on Eurostat data, indicates that it is unlikely to meet the European average for any of the 17 goals by 2030 [

16]. A comparison of these findings for Bulgaria and its neighboring country Romania reveals a similar level of SDG achievement and compliance forecasts. Bulgaria’s rates are approximately 36, 28%, while Romania’s stand slightly higher at around 37,38% [

15].

Previous studies identify Bulgaria and Romania as facing the most pressing state capacity challenges within the EU [

17,

18]. In this regard, the comparative study presents a compelling case to examine the capacities developed in sustainable development policy after nearly two decades of EU membership. It aims to examine the conditions for SDG implementation, focusing on two key aspects that shape how implementation unfolds: the formal government decision reflecting national preferences, and the state’s administrative and institutional capacity to act. The analysis first considers the government's formal response, including political commitment, goal prioritization, and the integration of SDGs into national policies. It then explores human and institutional capacities, with a focus on skills and competencies, the SDG coordination unit, and national science and research policy.

A qualitative approach was employed to gain deeper insight into the countries’ experiences and practices in SDG implementation. Evidence from Bulgaria covers the period 2015–2024, spanning the first half of the SDG implementation time frame. This period, characterized by ongoing political instability, was marked by progress under nine different government cabinets, including five caretaker governments. To strengthen research quality and validity, the study applied triangulation of methods and data [

58]. Multiple sources of evidence were used to avoid bias and capture diverse perspectives, with interviews and document analysis as the primary methods, supplemented by participant observation.

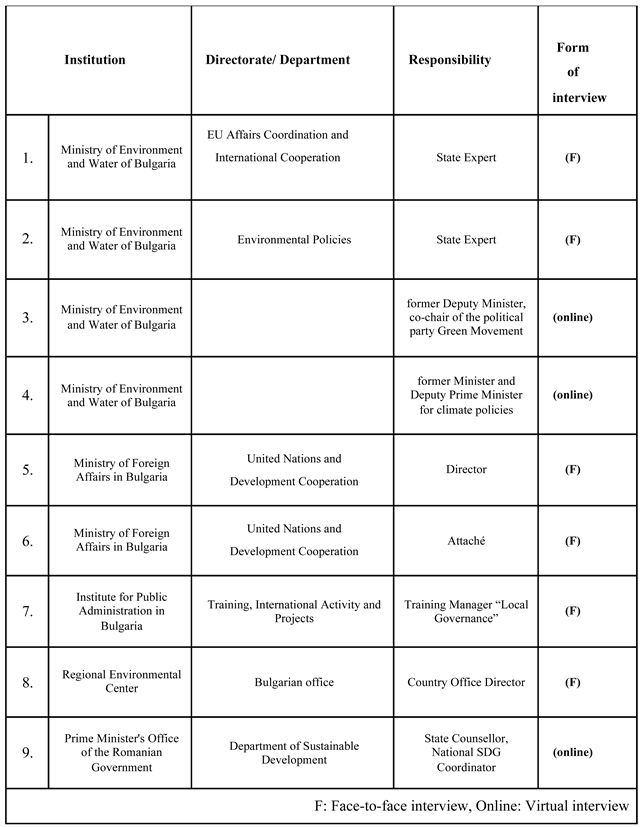

A total of nine expert interviews were conducted for this study - eight with Bulgarian officials and one with an expert on national SDG implementation in Romania. The interviewees were selected based on their expertise in managing SDG implementation (see

Appendix A for details). Six interviews were conducted in person and three online for practical reasons, lasting between 30 minutes and two hours. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed thematically. Informed consent was obtained at the beginning of each interview, granting permission to process and use the collected data. Additionally, informal interviews with civil servants were carried out during a short-term research stay at the Ministry of Environment and Water (MOEW) during Bulgaria’s EU Council Presidency in 2018. Notes from these informal conversations provided further insights into expert perceptions and practical experiences.

Although the observation period and number of interviews conducted in Bulgaria and Romania are not identical, additional insights were gathered through document analysis. Key national development strategies and reports were reviewed, including Bulgaria’s National Development Programme 2030 and the 2020 Voluntary National Review on the SDGs, as well as Romania’s 2023 Voluntary National Review: Implementing the 17 SDGs. Further information was also requested under the UNECE Aarhus Convention on access to public information.

The data were analyzed using a deductive–inductive approach: initial categories were defined deductively, while remaining open to inductive insights. Findings from both countries were then compared. To enhance the credibility of the interview data, member checks were conducted, involving respondents’ comments and approval of their statements [

59]. When applicable, the interim report was shared with interviewees to verify and, if necessary, adjust interpretations.

4. National SDG Implementation in Bulgaria and Romania

4.1. Bulgaria

4.1.1. Formal Decision on SDG Implementation

Following the adoption of the 17 SDGs by all UN Member States, Bulgaria’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs initiated a process to mainstream the goals into national policies. The objective was to inform ministries and government agencies about the global agenda and assign responsibilities for each goal. Consequently, sectoral policies and strategic plans relevant to SDG implementation were identified. Analyzing synergies and trade-offs across national policies has been identified as both a major challenge and a key future priority (VNR 2020).

Bulgaria’s national approach to SDG implementation aligns with key EU policy documents, recognizing two main strands of action: external and internal. External implementation refers to support for third countries, while internal implementation covers the full scope of domestic government action. As both an EU and UN Member State, Bulgaria’s foreign policy reflects core European values—peace, democracy, rule of law, human rights, and international cooperation—with particular emphasis on migration and improving cooperation with Southeast European countries [

60]. According to ministerial officials, domestic policies already address all SDGs implicitly, making a separate strategy unnecessary (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018, pers. comm.).

The National Development Programme ‘Bulgaria 2030’ is the country’s primary strategic planning document and serves as the formal government response to the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Ministry of Finance, 2019). Its preamble presents the global agenda as the overarching framework for national development, with commitments to be realized through individual sectoral policies (Administration of the Council of Ministers, pers. comm. 2024). The strategic document gives equal weight to all dimensions of sustainable development and sets three main goals: accelerated economic growth, demographic growth, and reduced inequalities. Following a series of government collapses linked to corruption scandals and political instability, caretaker governments redirected attention to the new National Recovery and Resilience Plan addressing COVID-19’s negative effects.

4.1.2. Domestic Capacities

Administrative skills and competencies. In 1998, Bulgaria introduced a unified civil service model through the Public Administration Act, emphasizing the role of political cabinets and political neutrality of civil servants in government activities [

61]. International organizations such as the EU and UN, along with their member states, have significantly contributed to strengthening environmental capacities in CEE through financial aid, technical support, capacity building, and increased stakeholder participation [

62,

63]. However, experts still view the capacity for pursuing EPI and delivering on the SDGs as very limited (Interviews with representatives from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, January 2018; Ministry of Environment and Water, January 2018; and Regional Environmental Center, October 2017). Key barriers to policy-making include a lack of clear vision and conceptual understanding of sustainable development as well as insufficient know-how to manage the interlinkages between its dimensions. Given the government's inability to develop effective strategic documents, one interviewee stated, "international commitments can only be implemented pro forma, based on poor-quality documents" (interview with representative, Ministry of Environment and Water, 2018). In this context, both civil servants and political actors highlight the need for specialized training in sustainable development fundamentals, strategic planning, environmental policy integration, the nexus approach, the circular economy, and sustainable consumption and production. Likewise, the 2020 VNR emphasizes the importance of strengthening administrative capacity to ensure effective SDG implementation [

60]. Although the National Institute for Public Administration (IPA) has introduced new training programs such as 'EU Actions in Climate: Green Bonds, Just Transition' and 'Recovery and Resilience Mechanism – New Challenges for 2021–2026,' it still lacks the organizational capacity to meet the increasing demand for training in SDG implementation (interview with representative, 2018 and pers. comm., IPA 2024).

SDG coordination unit. The absence of a functioning coordination mechanism for communication and cooperation across policy fields and stakeholders has long been seen as a major stumbling block to national policymaking in sustainable development – and more recently, to SDG implementation (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2021, pers. comm.; Ministry of Environment and Water, 2018; Government of Bulgaria, 2020). Since the early 2000s, several attempts to establish cross-departmental coordination, such as Council for Sustainable Development, have proven short-lived. In 2023, a new interdepartmental working group was created to update the National Indicator Framework for SDG monitoring and reporting (Government Decree 52/2023; Ministry of Education and Science, personal communication, 2024). Additionally, a National Council for Development was established as an advisory body to coordinate strategic programming documents and overseeing SDG implementation (Government Decree 77/2023). The Council's permanent working group is tasked with preparing the second VNR of SDG implementation (Resolution of the Council of Ministers 156/2024).

National science and research policy for sustainable development. The Ministry of Education and Science, responsible for monitoring SDG 4 (Quality Education), also oversees the National Strategy for the Development of Scientific Research in Bulgaria (2017–2030). This document outlines targets and action measures to modernize the national science system and align it with European standards, aiming to position Bulgaria as a hub for advanced research and innovation. Its priorities address areas such as sustainable infrastructure, low-carbon energy, bioeconomy, medicine, human capital, and ecology. The first national research programs with allocated budget (2018–2022), aimed to reduce fragmentation in the research system, supporting basic and applied research in areas such as environment and disaster risk management, climate and energy, health, technology, and culture. A public procurement process is scheduled for 2025 to select an external evaluator for the completed programs (Ministry of Education and Science of Bulgaria, pers. comm. 2024). In 2024, a new national research initiative—“Critical and Strategic Raw Materials for a Green Transition and Sustainable Development”—was launched with a five-year budget of €4 million (Government Decree № 508, 18.07.2024), exploring the extraction, processing, and recycling of critical raw materials for the green transition. Research projects are evaluated based on alignment with EU, national, and regional priorities, as well as research quality, in accordance with the Law on the Promotion of Scientific Research and Innovations (Ministry of Education and Science, pers. comm., 2024).

4.1.3. Experts’ Perceptions

The majority of experts agree that while Bulgaria’s government formally acknowledges the SDGs in its strategic documents, their practical integration into policymaking remains fragmented. Political commitment is seen as largely symbolic, driven more by EU and international obligations than domestic initiative. Fragmented policies and poor administrative capacity hinder targeted efforts towards SDG implementation. Environmental considerations are often sidelined, with sustainable development treated in isolation rather than holistically. A lack of cross-sectoral dialogue and experience in managing trade-offs and synergies further undermines effective policy-making. Even though EU membership has strengthened legislation and civil society engagement, ongoing political instability and weak policy continuity obstruct progress. Public awareness of the sustainability challenge remains low, with little public support for related initiatives. Experts stress the need for structured, participatory knowledge generation and capacity-building within public administration. Without stronger leadership and a coherent vision, Bulgaria risks reducing the SDGs to a mere formality instead of a transformative agenda.

A range of strategic actions have been recommended to improve national governance for SDG implementation, including designating a Vice-Prime Minister for Sustainable Development with real authority, assigning an Ombudsman for Future Generations, and forming thematic intergroups in the National Assembly. The need to foster systemic thinking and advance strategic planning and environmental governance is highlighted. Ministries are encouraged to take greater ownership of policymaking and better coordinate Bulgaria’s vast array of strategic documents. There is also a call to revise the National Development Programme ‘Bulgaria 2030’ for better cross-sectoral alignment and public engagement, and to strengthen EIA procedures to ensure legal compliance and restore public trust.

4.2. Romania

4.2.1. Formal Decision on SDG Implementation

Romania has actively integrated the 2030 Agenda into its strategic framework, notably through the revised "National Sustainable Development Strategy: Horizons 2013-2020-2030," with the motto ‘Keep healthy what keeps you in good health’, emphasizing sustainability and long-term well-being. The two VNRs (2018 and 2023) highlight Romania’s commitment to fostering an enabling environment for sustainable development. Beyond reporting national progress, the country has actively contributed to international SDG efforts, including chairing the EU Council’s working group on the SDGs during its 2019 presidency and supporting various European and regional organizations. The latest VNR outlines the national implementation approach based on collaboration among ministries and central authorities, grounded in whole-of-government and whole-of-society principles. Stakeholder engagement has been further promoted through drafting strategic documents, such as a voluntary subnational report tracking SDG progress at municipal and commune levels, and youth-led efforts like the Youth Statement and the Children’s Voice, which bring younger generations’ perspectives into the 2030 Agenda [

64].

In 2016, the Romanian Parliament was the first Inter-Parliamentary Union member to endorse the 2030 Agenda. The Chamber of Deputies formed a sub-committee on Sustainable Development to advance legislative ownership of the SDGs and propose measures for their integration into parliamentary processes. In 2019, the Romanian government requested the OECD to assess its institutional and strategic framework to enhance policy coherence for sustainable development (PCSD). The assessment focused on promoting good practices, including institutionalizing political commitment, integrating long-term thinking, ensuring cross-sectoral coordination, encouraging participation, and monitoring policy coherence. In 2023, a PCSD roadmap was created to strengthen the institutional framework and administrative capacity.

4.2.2. Domestic Capacities

SDG coordination unit. Three years after adopting the OECD recommendations, Romania has established a robust institutional framework, positioning itself as a national and regional leader in implementing the global agenda. In 2015, sustainable development was a shared responsibility between the Inter-ministerial Committee for the Coordination of Environmental Integration into Sectoral Policies, led by the Minister of Environment, and the Department of Sustainable Development, coordinated by a State Counsellor. Due to limited effectiveness, the national SDG coordination was allocated in 2017 to the Department of Sustainable Development under the Prime Minister’s oversight. The UN DESA recognized the Romanian Government for enhancing public institutions’ effectiveness, emphasizing its innovation and impact in advancing the 2030 Agenda [

64]. The importance of positioning the SDG coordination unit close to the Prime Minister, rather than within the Ministry of Environment or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, has been underlined, as these ministries lack the authority to address complex, cross-sectoral issues (interview with representative, Department of Sustainable Development, Romania, 2024). Several other key institutional bodies have been established, such as the Interdepartmental Committee for Sustainable Development (2019), Parliamentary Sub-Committee for Sustainable Development (2016), Consultative Council for Sustainable Development (2020), Network of Hubs for Sustainable Development (2019), Coalition Sustainable Romania (2020), and the Romanian Court of Accounts (2022). Complementary initiatives reflecting Romania’s commitment to sustainability include the Sustainable Romania Aggregator—an open data platform for national and EU sustainability data—and the Romanian Code of Sustainability, which encourages companies to publish sustainability reports based on the German model.

Administrative capacities. In 2018, Romania became the first EU country to introduce the role of 'sustainable development expert' into its national job classification, aiming to strengthen public institutions' capacity to implement the 2030 Agenda. In this connection, the Department for Sustainable Development launched a postgraduate program to develop relevant expertise. By 2022, the first cohort of 150 experts, mostly from central authorities and the 22 regional Hubs, have completed the pilot program. By 2026, the government plans to train 2,000 additional public officials—400 from central administration and 1,600 from local authorities—with content tailored to regional and local needs. The respondent stated that the program would focus on environmental and socio-economic issues, involving experts and trainers from both national and international universities and institutions. Another notable initiative is the virtual one-stop-shop platform, which aims to support regional and local administrations in ‘localizing’ the SDGs by providing access to best practices, relevant information, and resources.

Strengthening the science-society-policy interface for implementing the SDGs. Established in 2022, the Centre of Excellence for Sustainable Development in Public Administration promotes research, education, and dialogue to align public policies with the SDGs. Headquartered in Bucharest with regional branches in all eight development regions, the Centre connects universities, research institutes, local authorities, SMEs, NGOs, and civil society. It aims to advance sustainable development at all levels of governance by strengthening sustainability modeling, offering decision-makers innovative policy options and development scenarios. Dedicated research teams should support the 2030 Agenda by proposing strategies and digital solutions to foster adaptation, transformation, and learning across institutions and communities [

64]. According to the interviewee, Romania’s strong capacity-building efforts have significantly boosted academic engagement, with the number of universities prioritizing sustainability tripling in just a few years. Recognizing the key role of academia in shifting mindsets, future plans include appointing one or two university representatives per region to drive sustainability initiatives. To further enhance societal engagement and cross-sector collaboration, EUR 1.5 million is allocated annually to civil society and academic institutions.

5. Discussion

The study compares Bulgaria’s formal response to SDG implementation (2015–2024) with Romania’s approach. While both countries have shared similar development trajectories, their SDG implementation approaches differ significantly. Although being often considered laggards in environmental and political reforms [

65], Romania has made notable progress, outperforming Bulgaria on many SDG targets. However, the broader spillover effects of this progress remain uncertain and the environment-related SDGs (12, 13, 14, and 15) are unlikely to be met in either country if current trends persist, as progress in these areas is largely stagnating or in decline.

Bulgaria has adopted a largely formal and passive approach to SDG implementation, influenced by ongoing political instability. The SDGs are embedded in the main national strategic framework and are being pursued primarily through sectoral policies. Although widely acknowledged, the need for capacity-building remains pressing, as the national administration continue to struggle with limited human and institutional capacities. In 2023, the Council of Ministers was formally given the responsibility for coordinating SDG implementation, alongside the establishment of a dedicated institutional unit. While the first national research programs (2018–2022 and beyond) have been initiated, key sustainability criteria (e.g., transdisciplinarity, normativity, policy integration) have not yet been incorporated into project evaluations. In contrast, Romania prioritizes policy coherence in SDG implementation through a holistic approach featuring centralized coordination, parliamentary involvement, and a strong inter-institutional framework. Since establishing the Department of Sustainable Development under the Prime Minister’s oversight in 2017, Romania has leveraged international partnerships and created new bodies and initiatives to engage both government and society in advancing the SDGs and strengthen the science-policy interface.

Although both countries are candidates for OECD membership, Romania has taken proactive measures to build national and local expertise and develop an innovative governance framework for implementing the SDGs. This progress is mainly fueled by strong political commitment, parliamentary backing, and leadership. Collaboration with international partners has also driven key strategic and institutional reforms and strengthened administrative capacity. However, limited data currently restricts further evaluation of the effectiveness of related capacity-building programs.

SDG integration efforts in both countries have aimed to balance the different dimensions of sustainable development, albeit with a stronger emphasis on social and economic concerns. However, selectively prioritizing certain SDGs is believed to undermine the 2030 Agenda’s core principles of indivisibility and integration, ultimately impeding overall progress [

66]. Overlooking goals like climate action (SDG 13) or sustainable consumption and production (SDG 12) weakens global sustainability because these goals are closely linked to others (Weitz et al., 2023). Therefore, securing socio-economic progress without compromising the environmental SDGs necessitates integrating environmental concerns into development processes, underscoring the ongoing relevance of the EPI concept. Such an approach aligns with the normative goal of sustainable development, which aims to shape society within Earth's biophysical limits [

67], and is consistent with the ‘planetary boundaries’ framework, defining the environmental thresholds within which humanity can operate safely [

68].

Similar to this study's findings, Tosun and Leininger [

69] show that countries interpret and approach SDG integration and policy coherence differently, largely due to domestic policy-making processes rather than SDGs’ interlinkages, income level, or political centralization. Other comparative studies also highlight persistent gaps in assessing and managing SDG interlinkages e.g., [

70,

71].

Weak national capacities have long prevented compliance with international and European environmental and sustainable development norms in Bulgaria and the wider CEE region. Common barriers highlighted in the literature include limited conceptual understanding of sustainable development and insufficient administrative and institutional capacities e.g., [

72,

73,

74,

75]. While Bulgaria has yet to launch targeted efforts to address emerging skills gaps, Romania’s comprehensive capacity-building program merits further exploration for potential policy transfer. Both countries have initiated the modernization and Europeanization of their research systems; however, the integration of sustainability science into policy, research, and education across Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) is still in its early stages [

76,

77,

78]. Further conceptual and empirical research is needed to deepen the understanding of the role that science, as well as science and research policy, can play in fostering social learning and reflexive governance in the region. To date, experiences with public participation approaches—such as citizen science—remain underdeveloped in the Lower Danube Basin. Their potential is constrained by limited collaboration among scientists, authorities, and citizens, scarce resources, urban–rural disparities, and persistent patterns of social exclusion [

79].

A meta-analysis of the SDG steering effects during the early implementation phase found that impacts were primarily discursive—shaping how stakeholders understand and communicate sustainable development—while deeper normative and institutional effects remained limited [

20]. According to this framework, it can be said that Romania exhibits notable discursive, institutional, and normative changes, suggesting a transformative impact. By contrast, the impact in Bulgaria has been more modest, confined primarily to discursive and institutional dimensions.

The literature on capacities for SDG implementation rests mainly on earlier efforts to promote EPI. Drawing on the literature on reflexive governance and social learning, this paper provides new insights into the competencies, skills, and knowledge-based institutional mechanisms essential for effective national SDG governance. The study’s deductive-inductive approach proved useful in uncovering deeper normative implications for domestic capacities while remaining open to empirical realities. Yet, the findings reveal a significant mismatch between the capacities required and those currently available, highlighting the urgent need for targeted capacity-building programs. In this respect, a more systematic and conceptual analysis to capacity development for sustainability governance in the Eastern enlargement is generally lacking.

5. Conclusions

The success of the UN 2030 Agenda in achieving its transformative goal—ensuring global environmental sustainability while tackling urgent social and economic challenges—depends on the policy efforts of all member states. These efforts are shaped not only by governments’ genuine commitment but also by their capacity to put the SDGs’ core principles into practice. Understanding the capacity dimensions essential for effective national implementation is both conceptually and practically significant, as it helps consolidate fragmented insights and supports the development of comprehensive frameworks for assessing domestic capacities. This, in turn, enables policymakers and both national and international organizations to design targeted capacity-building interventions.

Addressing the problem characteristics of SDG implementation—uncertainty, complexity, interconnectedness, and multi-level governance—calls for long-term orientation and reflexive approaches that go beyond traditional rational policy-making. Promoting social learning is key in this context to reflect the changing relationship between knowledge production and governance. Building on these normative insights, the study identifies key cross-cutting aspects to complement existing frameworks on governance capacity for advancing environmental policy integration (EPI) and national SDG implementation. These include general competencies and skills of key actors, as well as conditions enabling adequate interaction between science, society, and policy. Given the persistent cognitive and institutional barriers in current policymaking practices, the need to develop these capacities has become critical.

Halfway to 2030, this study provides indicative findings on national responses and capacity allocation in two representative EU Eastern enlargement countries. The data suggests that the SDGs have had a transformative political impact in Romania and limited steering effects in Bulgaria. However, it remains unclear whether recent discursive, institutional, and normative changes will be sufficient to achieve the environmental goals while advancing social and economic targets. A longitudinal study could help assess the long-term impact of these changes on policy coordination and SDG progress.

Despite political commitment to the 2030 Agenda, Bulgaria has faced prolonged political instability and capacity deficits, leading to a largely formal approach to SDG implementation. In contrast, Romania has adopted a proactive approach by introducing an innovative governance framework and investing in capacity building across all levels—driven by political support, leadership, and international collaboration. Further work is needed to assess the feasibility of adapting Romania’s capacity-building model to Bulgaria. Although CEE countries share broadly similar background conditions, the findings cannot be generalized to other countries without a more comprehensive cross-national study to identify country-specific needs and best practices. Future studies could also explore government action on external SDG implementation, including support for developing countries and responses to international spillover effects.

Broadening SDG analysis to include countries' ability to deliver on the global goals can help explain performance and variation in implementation strategies. The concept of capacity building has been used, for example, to compare countries’ differing abilities and the extent to which these abilities have been developed in the field of environmental policy [

80]. Similarly, the analytical categories developed in this study could contribute to a more universal framework for assessing domestic capacities in sustainable development, highlighting factors such as skills and competencies, conditions for knowledge generation, and the openness of policy systems.

Having implications beyond the 2030 Agenda, further conceptual and empirical work is needed to determine how effective capacity development processes should be designed in this context. Key questions that arise include: Which interventions are most effective in changing cognitive abilities and behavior? Who should organize these learning processes, and which actors should be involved? What costs are associated with their implementation, and how should they be financed?

To enhance the effectiveness of national SDG implementation in Bulgaria, policymakers should consider the following recommendations, derived from conceptual analysis and expert interviews:

Strengthen political and legislative commitment – Strengthen the role of the National Assembly by forming intergroups on the topic and appointing an Ombudsman for future generations.

Adopt an environmentally integrated approach – Avoid cherry-picking SDGs, ensuring socio-economic progress does not come at the expense of environmental degradation, adopt an EPI approach and strengthen EIA procedures.

Promote cross-sectoral communication – Facilitate communication across sectors and departments to manage synergies and trade-offs between the SDGs.

Foster science-policy-society interaction – Create adequate conditions for collaboration between science, policy, and society, such as through national science and research programs for sustainable development.

Build capacities for sustainable development – Develop the necessary competencies and skills across national and local authorities to enhance the effectiveness of policy-making and strategic documents.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Prior informed consent was obtained from all interviewees involved in the study.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| CEE |

Central and Eastern Europe |

| EPI |

Environmental Policy Integration |

| PCSD |

Policy coherence for sustainable development |

| VNR |

Voluntary National Review |

References

- Hickmann, T., Biermann, F., Sénit, C.-A., et al. Scoping article: research frontiers on the governance of the Sustainable Development Goals. Global Sustainability 2024, 7, p. e7; [CrossRef]

- Stafford-Smith, M., Griggs, D., Gaffney, O., et al. Integration: the key to implementing the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability Science 2017, 12(6), p. 911-919; [CrossRef]

- Hametner, M.; Kostetckaia, M. Frontrunners and laggards: How fast are the EU member states progressing towards the sustainable development goals? Ecological Economics 2020, 177, p. 106775; [CrossRef]

- Hametner, M. Economics without ecology: How the SDGs fail to align socioeconomic development with environmental sustainability. Ecological Economics 2022, 199, p. 107490; [CrossRef]

- Firoiu, D., Ionescu, G.H., Cismaș, L.M., et al. Can Europe Reach Its Environmental Sustainability Targets by 2030? A Critical Mid-Term Assessment of the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15(24), p. 16650; [CrossRef]

- Moinuddin, M.; Olsen, S.H. Examining the unsustainable relationship between SDG performance, ecological footprint and international spillovers. Scientific Reports 2024, 14(1), p. 11277; [CrossRef]

- Weitz, N., Carlsen, H., Bennich, T., et al. Returning to core principles to advance the 2030 Agenda. Nature Sustainability 2023, 6; [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Kanie, N.; Kim, R. Global governance by goal-setting: the novel approach of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2017, 26-27, p. 26-31; [CrossRef]

- United Nations Global Sustainable Development Report 2023: Times of crisis, times of change: Science for accelerating transformations to sustainable development.; Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the Secretary-General: New York, 2023; Available online: https://desapublications.un.org/publications/global-sustainable-development-report-2023#:~:text=Citation%3A%20Independent%20Group%20of%20Scientists,%2C%20New%20York%2C%202023 (accessed on: 25. June 2025).

- Sagar, A. Capacity Development for the Environment: A View for the South, A View for the North. Annual Review of Energy and the Environment 2000, 25(1), p. 377-439; [CrossRef]

- Sagar, A.D.; VanDeveer, S.D. Capacity Development for the Environment: Broadening the Scope. Global Environmental Politics 2005, 5(3), p. 14-22; [CrossRef]

- Jänicke, M.; Jörgens, H. New Approaches to Environmental Governance. In Environmental governance in global perspective: new approaches to ecological modernisation; Jänicke, M., Jacob, K., Eds.; Freie Universität, Environmental Policy Research Centre: Berlin, 2007; 167-210.

- Nilsson, M.; Persson, Å. Policy note: Lessons from environmental policy integration for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Environmental Science & Policy 2017, 78, p. 36-39; [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Malekpour, S.; Mintrom, M. Cross-scale, cross-level and multi-actor governance of transformations toward the Sustainable Development Goals: A review of common challenges and solutions. Sustainable Development 2023, 31(3), p. 1250-1267; [CrossRef]

- Firoiu, D., Ionescu, G.H., Băndoi, A., et al. Achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDG): Implementation of the 2030 Agenda in Romania. Sustainability 2019, 11(7), p. 2156; [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, G., Jianu, E., Patrichi, I., et al. Assessment of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Implementation in Bulgaria and Future Developments. Sustainability 2021, 13, p. 12000; [CrossRef]

- Kramer, J. EU Enlargement and the Environment: Six Challenges. Environmental Politics 2004, 13(1), p. 290-311; [CrossRef]

- Andonova, L. Transnational Politics of the Environment. The European Union and Environmental Policy in Central and Eastern Europe; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2004.

- United Nations The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015; UN: New York, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf (accessed on: 23. June 2025).

- Biermann, F., Hickmann, T., Sénit, C.-A., et al. Scientific evidence on the political impact of the Sustainable Development Goals. Nature Sustainability 2022, 5(9), p. 795-800; [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition - July 2023; UN DESA: New York, 2023; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/ (accessed on: 10. December 2023).

- Lafortune, G., Fuller, L., Kloke-Lesch, A., et al. European Elections, Europe’s Future and the Sustainable Development Goals. SDSN and SDSN Europe; Dublin University Press: Paris, 2024; Available online: https://doi.org/10.25546/104407 (accessed on: 23. June 2025).

- Gupta, J.; Nilsson, M. Toward a Multi-level Action Framework for Sustainable Development Goals. In Governing through Goals: Sustainable Development Goals as Governance Innovation; Kanie, N., Bierman, F., Eds.; MIT Press, 2017; 275-294.

- Bennich, T.; Weitz, N.; Carlsen, H. Deciphering the scientific literature on SDG interactions: A review and reading guide. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 728, p. 138405; [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F., Stevens, C., Bernstein, S., et al. Global Goal Setting for Improving National Governance and Policy. In Governing through Goals: Sustainable Development Goals as Governance Innovation; Kanie, N., Biermann, F., Eds.; The MIT Press, 2017; 75–98.

- Glass, L.-M.; Newig, J. Governance for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How important are participation, policy coherence, reflexivity, adaptation and democratic institutions? Earth System Governance 2019, 2, p. 100031; [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M., Vijge, M.J., Alva, I.L., et al. Interlinkages, Integration and Coherence. In The Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals: Transforming Governance Through Global Goals?; Sénit, C.-A., Biermann, F., Hickmann, T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2022; 92-115.

- Breuer, A., Leininger, J., Malerba, D., et al. Integrated policymaking: Institutional designs for implementing the sustainable development goals (SDGs). World Development 2023, 170, p. 106317; [CrossRef]

- Bornemann, B.; Weiland, S. The UN 2030 Agenda and the Quest for Policy Integration: A Literature Review. Politics and Governance 2021, 9(1), p. 96-107; DOI: doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i1.3654.

- Luks, F.; Siebenhüner, B. Transdisciplinarity for social learning? The contribution of the German socio-ecological research initiative to sustainability governance. Ecological Economics 2007, 63, p. 418-426; [CrossRef]

- UNEP/UNECE GEO-6 Assessment for the pan-European region; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/geo-6-global-environment-outlook-regional-assessment-pan-european-region (accessed on: 20. June 2025).

- Gupta, A., Andresen, S., Siebenhüner, B., et al. Science Networks. In Global Environmental Governance Reconsidered; Biermann, F., Pattberg, P., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2012; 69-94.

- Future Earth Strategic Research Agenda 2014. Priorities for a global sustainability research strategy; International Council for Science: Paris, 2014; Available online: https://council.science/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Future-Earth-Strategic-Research-Agenda-2014.pdf (accessed on: 24. June 2025).

- Pregernig, M.; Böcher, M. The role of expertise in European environmental governance: theoretical perspectives and empirical evidence. In Long-Term Policies: Governing Social-Ecological Change; Siebenhüner, B., Arnold, M., Eisenack, K., et al., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2013; 29-46.

- Griggs, D., Stafford Smith, M., Rockström, J., et al. An integrated framework for Sustainable Development Goals. Ecology abd Society 2014, 19, p. 49; [CrossRef]

- Stafford-Smith, M., Cook, C., Sokona, Y., et al. Advancing sustainability science for the SDGs. Sustainability Science 2018, 13(6), p. 1483-1487; [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M., Chisholm, E., Griggs, D., et al. Mapping interactions between the sustainable development goals: lessons learned and ways forward. Sustainability Science 2018, 13(6), p. 1489-1503; [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Priorities for science to support national implementation of the sustainable development goals: A review of progress and gaps. Sustainable Development 2021, 29(4), p. 635-652; [CrossRef]

- Messerli, P., Kim, E.M., Lutz, W., et al. Expansion of sustainability science needed for the SDGs. Nature Sustainability 2019, 2(10), p. 892-894; [CrossRef]

- Siebenhüner, B., Arnold, M., Eisenack, K., et al. Long-term governance for social-ecological change; Routledge: New York, 2013.

- Schneider, V.; Leifeld, P.; Malang, T. Coping with creeping catastrophes: national political systems and the challenges of slow-moving policy problems. In Long-term governance for social-ecological change; Siebenhüner, B., Arnold, M., Eisenack, K., et al., Eds.; Routledge: New York, 2013; 221-239.

- Jänicke, M.; Jörgens, H. Strategic Environmental Planning and Uncertainty: A Cross-National Comparison of Green Plans in Industrialized Countries. Policy Studies Journal 2000, 28, p. 612-632; [CrossRef]

- Grunwald, A. Working Towards Sustainable Development in the Face of Uncertainty and Incomplete Knowledge. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2007, 9(3-4), p. 245-262; [CrossRef]

- Voß, J.-P.; Bauknecht, D.; Kemp, R. Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, 2006.

- Voß, J.-P.; Smith, J.; Grin, J. Designing Long-term Policy: Rethinking Transition Management. Policy Science 2009, 42, p. 275-302; [CrossRef]

- Brousseau, E.; Dedeurwaerdere, T.; Siebenhüner, B. Reflexive Governance and Global Public Goods; MIT Press: Cambridge, 2012.

- Beck, U. The risk society-towards a new modernity; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 1992.

- Voß, J.-P.; Kemp, R. Sustainability and reflexive governance: introduction. In Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development; Voß, J.-P., Bauknecht, D., Kemp, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, 2006.

- Brousseau, E.; Dedeurwaerdere, T.; Siebenhüner, B. Knowledge Matters: Institutional Frameworks to Govern the Provision of Global Public Goods. In Reflexive Governance for Global Public Goods; Brousseau, E., Dedeurwaerdere, T., Siebenhüner, B., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, , 2012; 243-282.

- Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., et al. The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies; SAGE Publications, 1994.

- Jasanoff, S. States of knowledge: the co-production of science and social order; Routledge, 2004.

- Kates, R.W., Clark, W.C., Corell, R., et al. Sustainability Science. Science 2001, 292(5517), p. 641-642; [CrossRef]

- Funtowicz, S.O.; Ravetz, J.R. Science for the post-normal age. Futures 1993, 25(7), p. 739–755; [CrossRef]

- Funtowicz, S.O.; Ravetz, J.R. The Worth of a Songbird - Ecological Economics as a Post-Normal Science. Ecological Economics 1994, 10(3), p. 197-207; [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, E., Kivisaari, S., Lovio, R., et al. Designed to travel? Transition Management encounters environmental and innovation policy histories in Finland. Policy Sciences 2009, 42(4), p. 409–427; [CrossRef]

- Grothmann, T.; Siebenhüner, B. Reflexive Governance and the Importance of Individual Competencies: The Case of Adaptation to Climate Change in Germany. In Reflexive Governance and Global Public Goods; Brousseau, E., Dedeurwaerdere, T., Siebenhüner, B., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, 2012; 299-313.

- Van Evera, S. Guide to methods for students of political science; Cornell University Press, 1997.

- Flick, U. Triangulation in Qualitative Research. In A companion to qualitative research; Flick, U., Kardorff, E.v., Steinke, I., Eds.; Sage Publications: London; Thousand Oaks, Calif., 2004; 178-183.

- Flick, U. Managing Quality in Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: London, 2007.

- Government of Bulgaria Voluntary National Review of the Republic of Bulgaria of the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals.; Council of Ministers, 2020; Available online: https://hlpf.un.org/countries/bulgaria/voluntary-national-review-2020 (accessed on: 24. June 2025).

- Arabadzhiyski, N. Пoлитики за развитие на администрацията на изпълнителната власт в Република България през Втoрия прoграмен периoд на членствo в Еврoпейския съюз. (Policies for developing Bulgaria’s executive administration during the second EU membership period). In Conference proceedings “10 Years in the EU - on the development of public policies and legislation”, New Bulgarian University, 2018.

- Andonova, L.; VanDeveer, S. EU expansion and the internationalization of environmental politics in Central and Eastern Europe. In Comparative Environmental Politics; Steinberg, P., VanDeveer, S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass, 2012; 287-313.

- VanDeveer, S. Effectiveness, Capacity Development and International Environmental Cooperation. In Handbook of Global Environmental Politics Dauvergne, P., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2005.

- Government of Romania Romania 2023 Voluntary National Review: Implementing the 17 SDGs Romania.; Department of Sustainable Development: Romania, 2023; Available online: https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/index.php/en/2023/romania-2023-voluntary-national-review-implementing-17-sdgs (accessed on: 20. June 2025).

- Knill, C.; Heichel, S.; Arndt, D. Really a front-runner, really a Straggler? Of environmental leaders and laggards in the European Union and beyond — A quantitative policy perspective. Energy Policy 2012, 48, p. 36-45;

- Forestier, O.; Kim, R.E. Cherry-picking the Sustainable Development Goals: Goal Prioritization by National Governments and Implications for Global Governance. Sustainable Development 2020, 28, p. 1269-1278; [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.; Farley, J. Ecological economics: principles and applications. Ecological Economics; Island Press: Washington, DC, 2004.

- Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, p. 472-475; [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Leininger, J. Governing the Interlinkages between the Sustainable Development Goals: Approaches to Attain Policy Integration. Global Challenges 2017, 1(9); [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Prioritising SDG targets: assessing baselines, gaps and interlinkages. Sustainability Science 2019, 14(2), p. 421-438; [CrossRef]

- Paneva, A.; Dokov, H.; Stamenkov, I. Reporting and Measuring Progress Towards the SDGs: Evidence from Central and Eastern Europe. Preprint. 2025; [CrossRef]

- Börzel, T. Coping with Accession to the European Union. New Modes of Environmental Governance; Palgrave Macmillan UK: Basingstoke, 2009.

- Jörgens, H. Governance by Diffusion: Implementing Global Norms Through Cross-National Imitation and Learning. In Governance for Sustainable Development. The Challenge of Adapting Form to Function; Lafferty, W., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, 2004; 246-283.

- Medarova-Bergström, K.; Steger, T.; Paulsen, A. The Case of EPI in Central and Eastern Europe. In Governance for the environment: a comparative analysis of environmental policy integration; Goria, A., Sgobbi, A., von Homeyer, I., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltanham, UK, 2010; 179-199.

- Simeonova, V.; van der Valk, A. Environmental policy integration: Towards a communicative approach in integrating nature conservation and urban planning in Bulgaria. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, p. 80-93; [CrossRef]

- Adomßent, M., Fischer, D., Godemann, J., et al. Emerging areas in research on higher education for sustainable development – management education, sustainable consumption and perspectives from Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Cleaner Production 2014, 62, p. 1-7; [CrossRef]

- Dlouhá, J.; Glavič, P.; Barton, A. Higher education in Central European countries – Critical factors for sustainability transition. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 151, p. 670-684; [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Sustainability Science in Central and Eastern Europe. Summary Statement of the Bratislava workshop: Bratislava: German, Austrian and Slovak National Commissions for UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2014; Available online: https://www.unesco.lt/images/wordpress/uploads/2014/06/Sustainability-Science-in-CEE-Summary-Statement-Bratislava-workshop-17June2014.pdf (accessed on: 20. June 2025).

- Cârstea, E.M.; Popa, C.L.; Donțu, S.I. Citizen Science for the Danube River—Knowledge Transfer, Challenges and Perspectives. In The Lower Danube River: Hydro-Environmental Issues and Sustainability; Negm, A., Zaharia, L., Ioana-Toroimac, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; 527-554.

- Jänicke, M. The Political System’s Capacity for Environmental Policy: The Framework for Comparison. In Capacity Building in National Environmental Policy. A Comparative Study of 17 Countries; Weidner, H., Jänicke, M., Eds.; Springer, 1997; 1-18.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).