1. Introduction

In patients undergoing implant therapy for maxillary molar defects, the lack of existing bone height in the maxillary molars often prevents ideal implant placement. Maxillary sinus augmentation with a lateral approach (MSA) is performed to solve this problem. While MSA is a well-established treatment and its long-term prognosis is well known,[

1,

2,

3] it has been reported to be associated with several postoperative complications such as facial swelling and pain, infection, and maxillary sinusitis.[

4]

The placement of a barrier membrane has been reported to promote bone formation and increase the implant-survival rate because the barrier membrane covering the open window in MSA can prevent fibroblast invasion from connective tissue during wound healing and promote bone regeneration around the bone graft material.[

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] However, the barrier membrane has also been reported to decrease blood supply to the bone graft material and increase the risk of infection.[

11,

12,

13,

14] Barrier membranes are categorised as resorbable or non-resorbable. While non-resorbable membranes can reliably block fibroblast invasion during the bone-regeneration period, allowing for osteogenesis, another invasive surgery is needed to remove the membrane, which may lead to complications such as exposure and infection due to lack of blood flow.[

4] On the other hand, resorbable membranes do not need to be removed because the body absorbs them, and most of these membranes are made from collagen derived from animals such as pigs and cows. However, prediction of the degradation and resorption rate of membranes produced from collagen is difficult, and it remains unclear whether they maintain a defence mechanism that prevents cell invasion.[

8] Regarding the need for a covering membrane, Tarnow et al.[

15] reported that implant survival was 100% when covered with an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (e-PTFE) membrane and 93% when not covered. Tawil et al.[

16] also reported a much higher success rate when the implant was covered with a collagen membrane than when it was not covered. Ohayon et al.[

17] studied bone graft material displacement from the open window with and without a barrier membrane. They reported that a barrier membrane was useful. That bone graft displacement from the open window correlated with postoperative thickening of the maxillary sinus mucosa and postoperative complications such as infection, intraoral pain, and facial swelling. These findings indicate that barrier membranes should have selective permeability, such as resorbability, slow absorption rate, and maintaining vascular growth within the membrane.

In the present study, we prospectively evaluated the effectiveness of L-lactic acid/ε-caprolactone [P(LA/CL)], a long-term resorbable guided bone regeneration membrane, as a barrier membrane for lateral approach maxillary sinus augmentation and examined the risk factors associated with postoperative bone graft displacement and reduced bone height.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research design and ethical approval

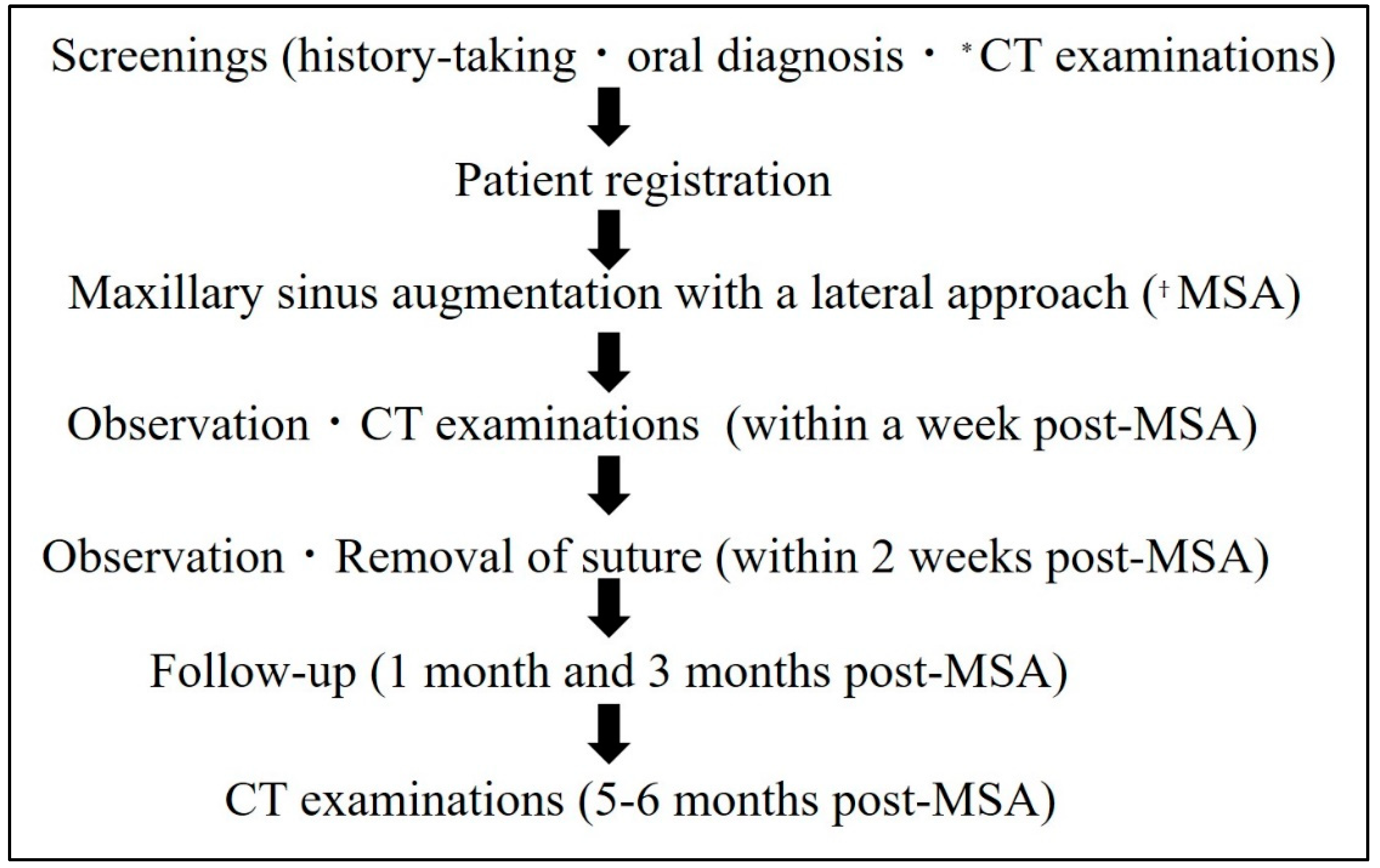

This prospective study was conducted at Showa University Dental Hospital Implant Center. The clinical trial, including patient recruitment, was conducted from October 2018 to May 2022, according to the protocol in

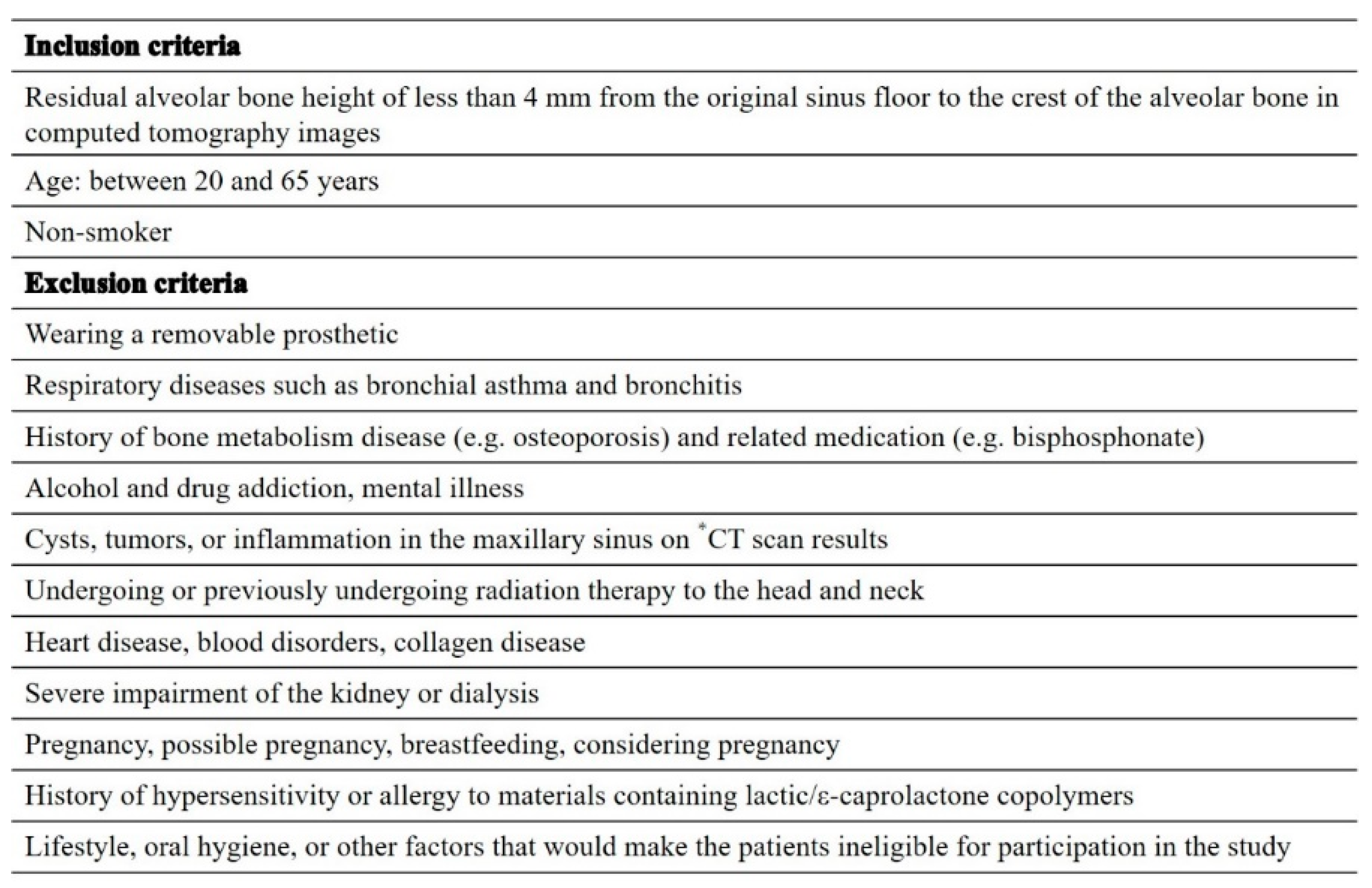

Figure 1. The study participants were non-smoking patients aged 20–65 years with maxillary molar defects requiring two-stage MSA with a residual bone height of ≤4 mm.

Table 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of SHOWA University Clinical Research Review Board (approval number jRCTs032190123 and Oct 19th, 2019 of approval) and by the Institutional Review Board of Showa University Dental Hospital (approval No. SUDH0043). It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written informed consent for this study. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

2.2. Graft material

The artificial bone substitute was carbonate apatite (Cytrans Granules🄬, GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan: hereafter CO3Ap). CO3Ap contains 6%–9% carbonate by weight in an apatite crystal structure, and the particle size (short diameter) of CO3Ap ranges from 600 to 1,000 μm.

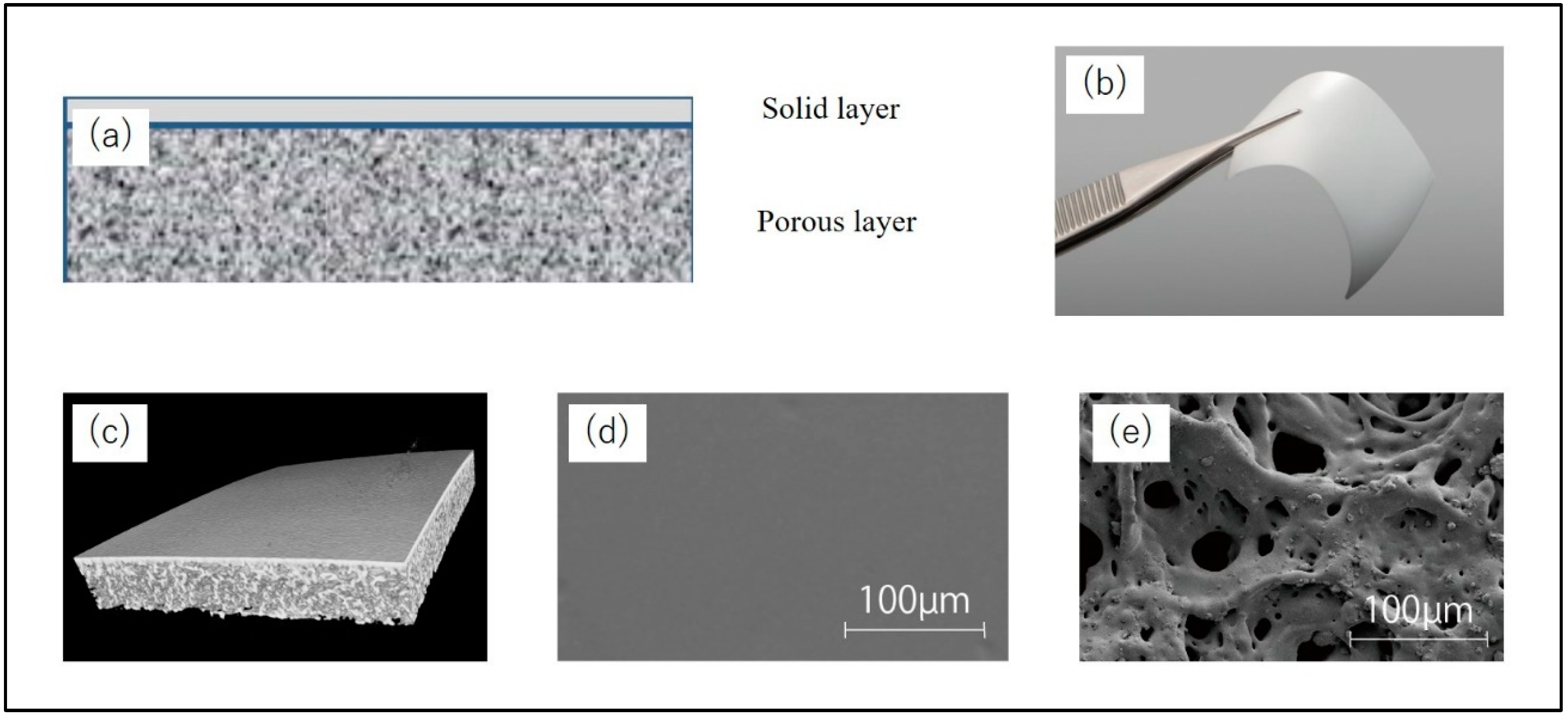

2.3. Barrier membrane material

A bilayer P(LA/CL) membrane (GMEM-B2; GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used as the barrier membrane for the open window in lateral approach MSA. GMEM-B2 has a white membrane structure moulded from a bioabsorbable polymer. It is a rectangular film measuring approximately 30 mm × 40 mm and consists of two layers, a solid layer and a porous layer, with a thickness of approximately 200 μm. The solid layer is placed on the soft tissue side, and the porous layer is on the hard tissue side. The solid layer blocks fibroblast invasion, while the porous layer promotes differentiation into osteoblasts. The GC Corporation provided GMEM-B2 (

Figure 2).

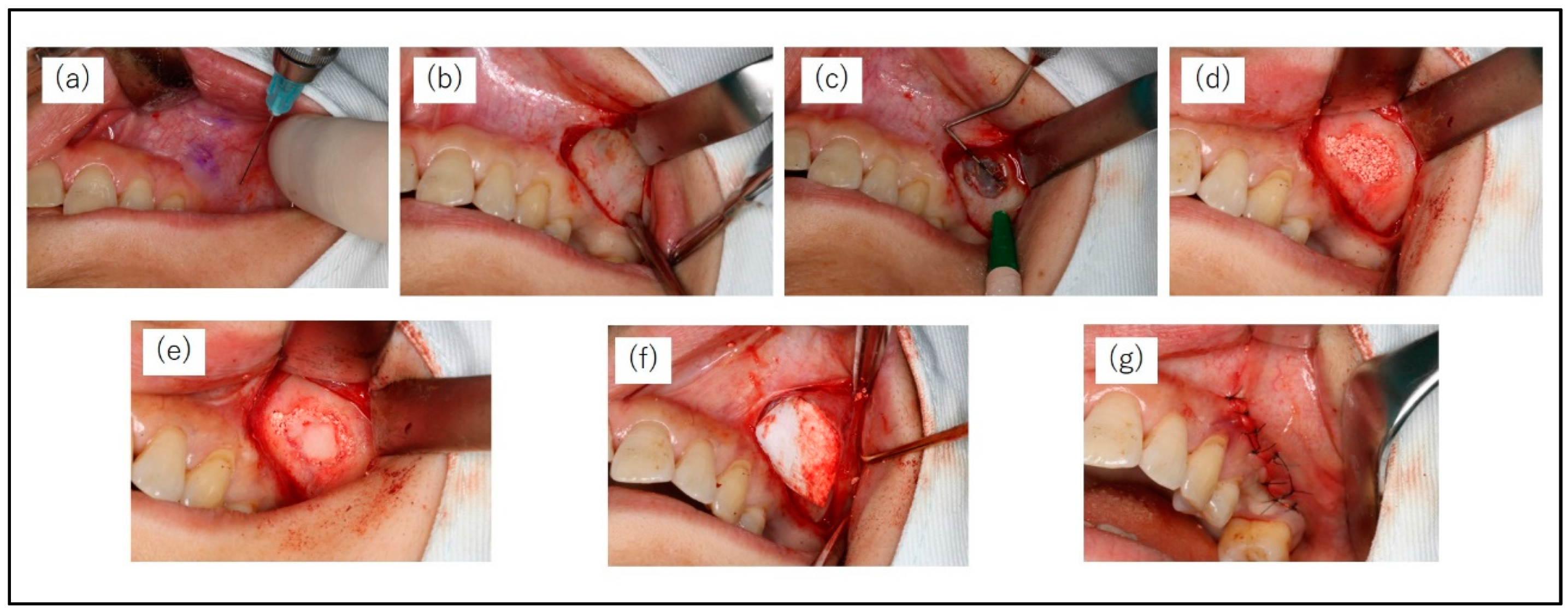

2.4. Surgical protocol

All patients were instructed to take an oral dose (1 g) of amoxicillin hydrate (Amoxicillin Capsules; Nichi-Iko Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) 1h before surgery. MSA was conducted under local infiltration anaesthesia (2% lidocaine including 1/80,000 adrenaline). The bony window of the lateral maxillary wall was designed according to the planned location(s) of the implant(s) and the anatomy of the maxillary sinus. A horizontal incision was made on the buccal side of the alveolar bone at the maxillary molar defect, and the mucoperiosteal flap was turned over to expose the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus. A small diamond bar was used to cut 360° around the entire circumference of the bone to form a bony window, which was separated from the sinus membrane. The mucosa of the maxillary sinus floor was carefully dissected and elevated using a mucosa elevator. The sinus floor mucosa was carefully checked for perforation. After elevation of the basilar membrane of the sinus, the elevated space was filled with CO3Ap granules. Finally, the bony window was repositioned, a GMEM-B2 membrane was placed over it, and the mucoperiosteal flap was sutured (

Figure 3).

To prevent postoperative infection, patients received amoxicillin 250 mg four times a day for five days and 0.2% benzethonium chloride mouthwash four times a day for two weeks, as well as loxoprofen sodium 60 mg three times a day for three days as an analgesic. Sutures were removed two weeks after surgery.

2.5. Radiographic examinations

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) examinations were performed preoperatively (pre-MSA), within one week postoperatively (post-MSA1W), and at 5–6 months postoperatively (post-MSA5M), in accordance with the protocol shown in

Figure 1. All images were obtained using the KaVo 3D eXam (KaVo Dental Systems, Biberach, Germany). The scanning parameters were 120 kVp, 5 mA, 8.9 s acquisition time, 0.25 mm thick axial slice and isotropic voxel size, and an imaging area of 16 × 16 cm.

2.6. Evaluation items

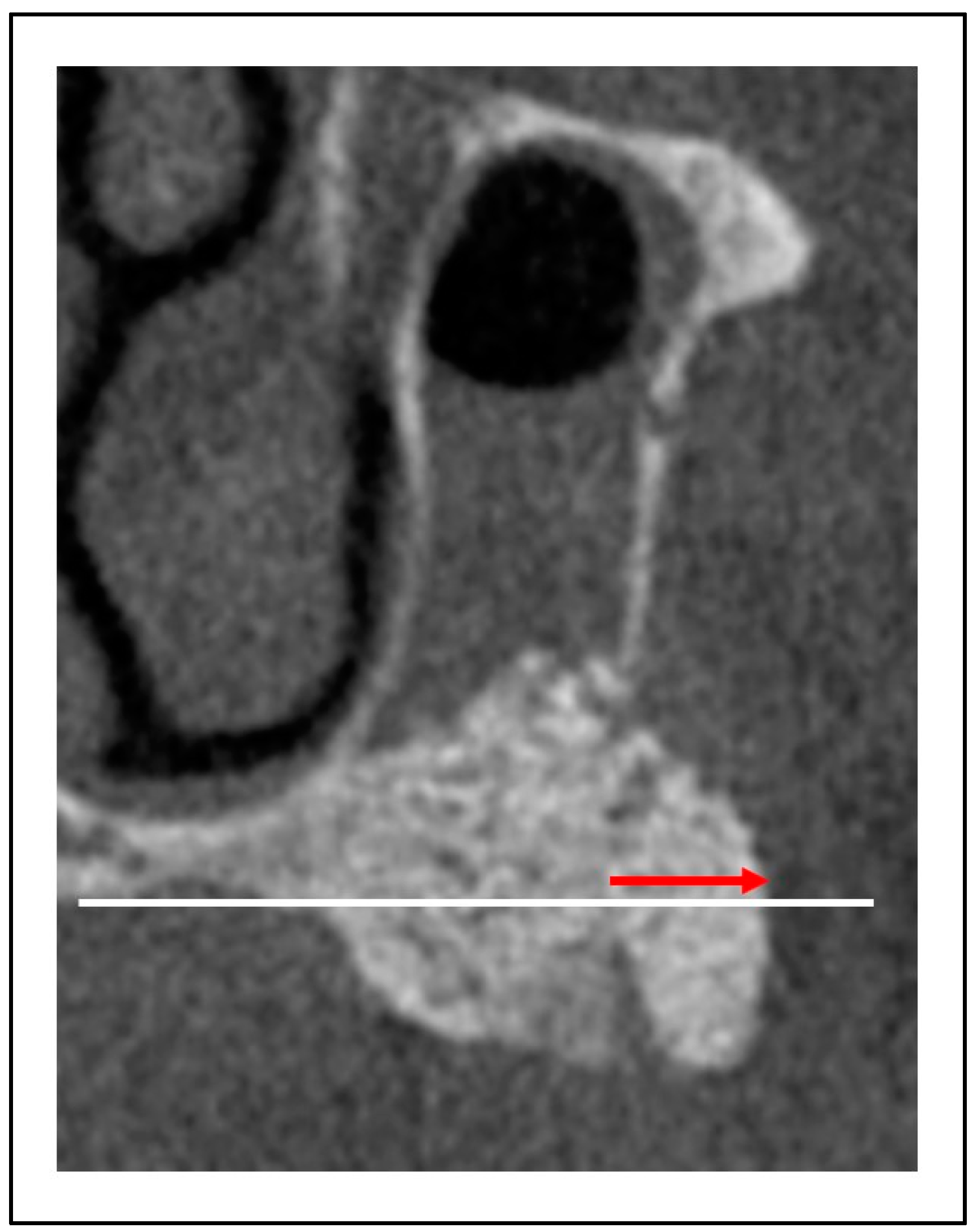

The following items were evaluated to measure the effectiveness of GMEM-B2 in MSA: Presence or absence of infection and sinusitis, exposure of barrier membrane, bone height post-MSA1W and post-MSA5M, rate of reduction of bone height post-MSA1W and post-MSA5M, presence and amount of bone graft displacement (mm;

Figure 4).

The following factors were evaluated concerning bone graft displacement and the percentage decrease in bone height (

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

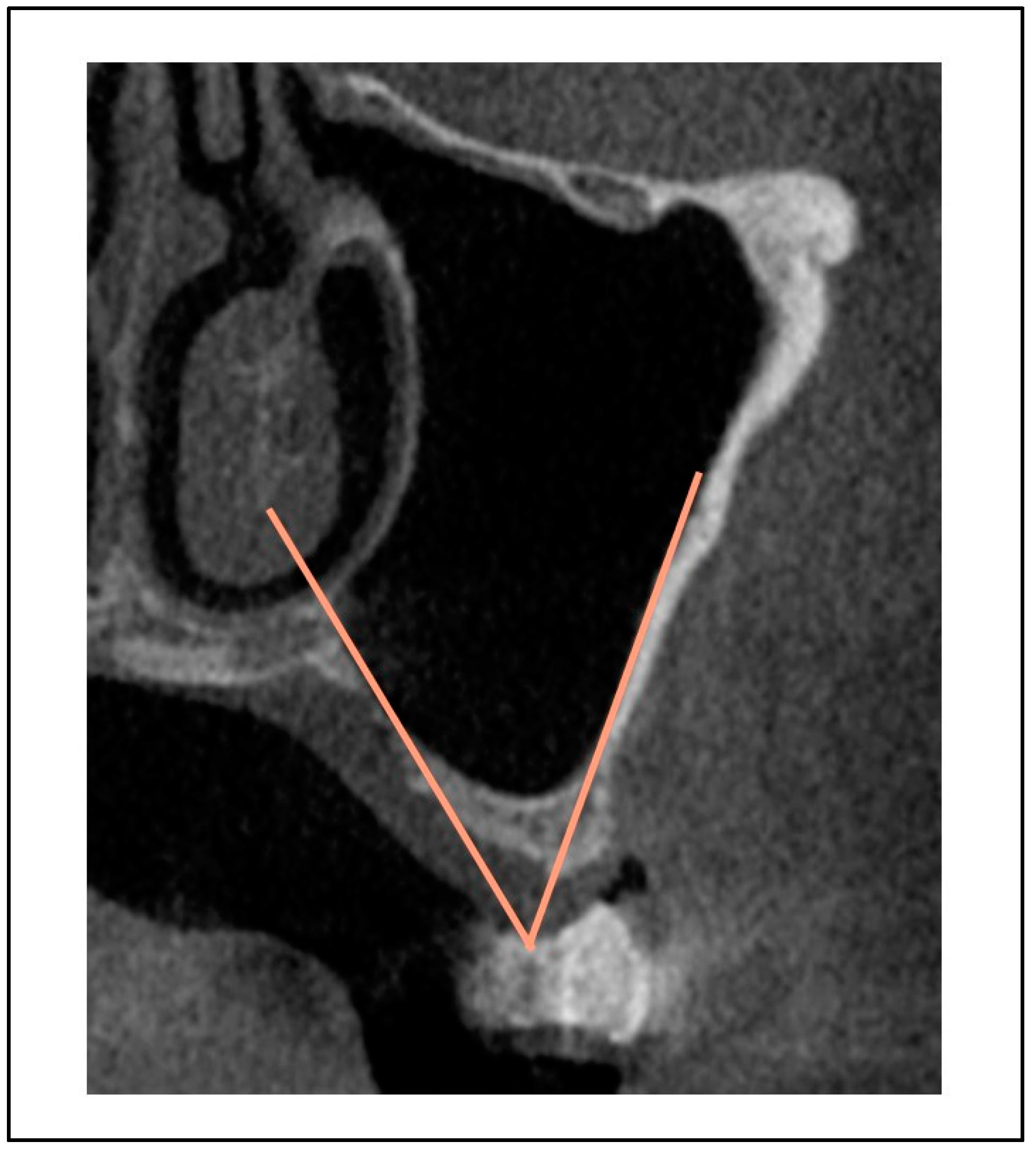

Figure 7): sex; age; maxillary sinus angle (between the lateral and medial wall of the maxillary sinus:

Figure 5); palatonasal recess (PNR), between the roof of the hard palate and the lateral wall of the nasal cavity:

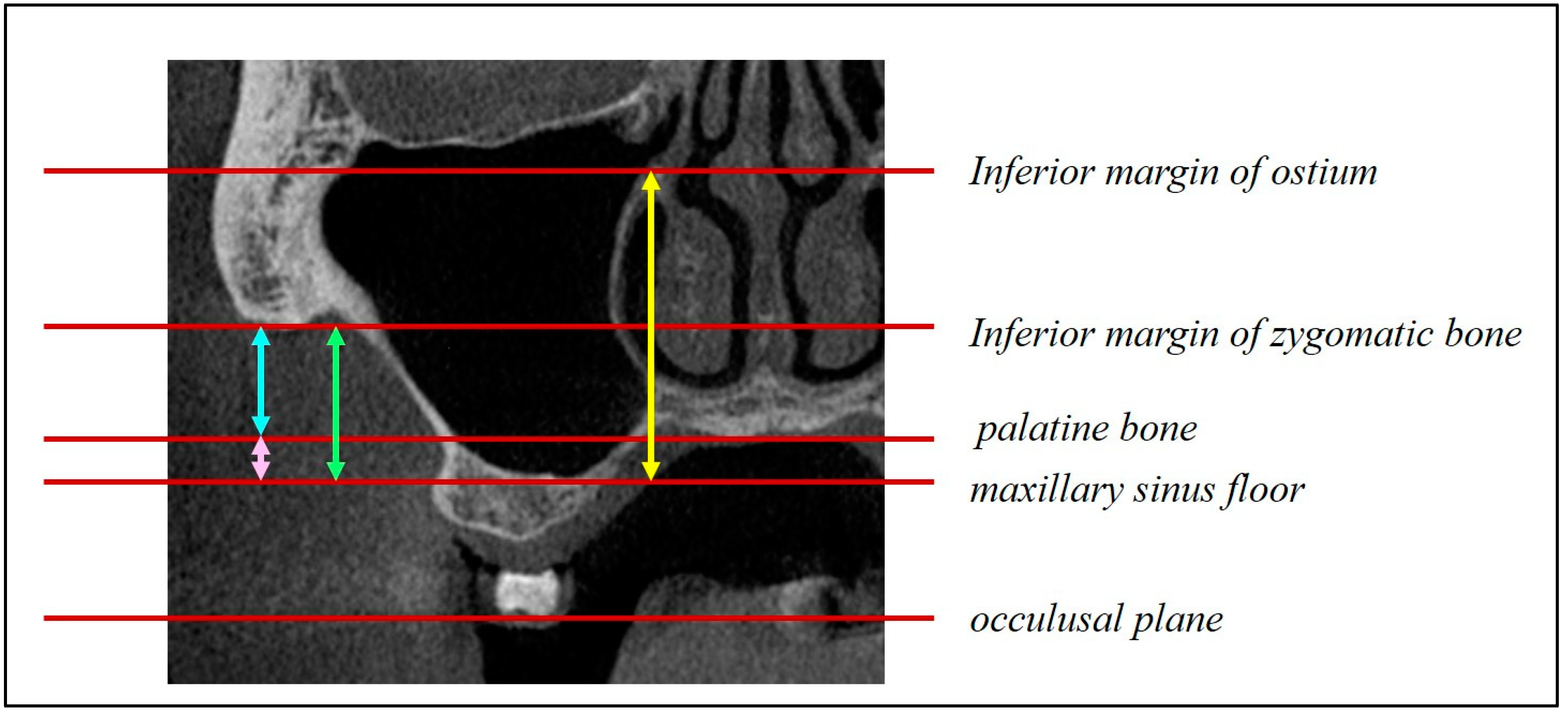

Figure 6); height from the maxillary ostium to the maxillary sinus floor (

Figure 7, yellow marker); and height from the palatal bone to the maxillary sinus floor (

Figure 7, blue marker).

The same oral and maxillofacial radiologist, with over 20 years of experience, performed all measurements.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The effectiveness of GMEM-B2 was evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The factors related to bone graft displacement and the percentage decrease in bone height were evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U test, Spearman’s correlation, and chi-square test. Moreover, multiple comparisons among the three groups were performed using the Friedman test. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant (PASW Statistics 18.0; SPSS Inc. SPSS, Japan).

3. Results

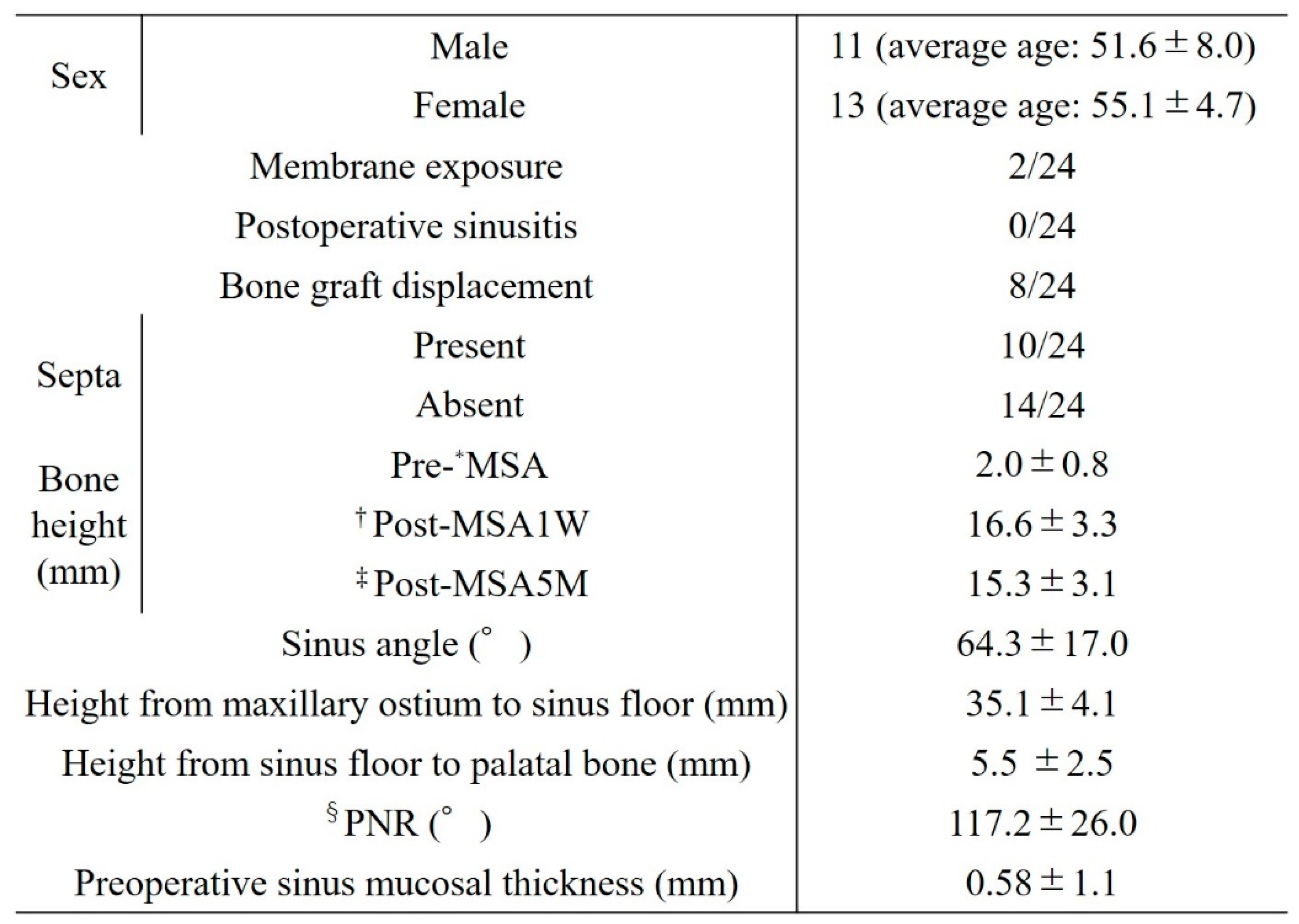

Table 2 shows the patient data. The study population included 24 patients (11 men, 13 women) aged 43–64 years (mean age, 53.5 ± 6.52 years). Bone graft displacement from the bony window was noted in 8 patients (33.3%). Partial exposure of the barrier membrane occurred in 2 patients but without postoperative inflammation, infection, or maxillary sinusitis. Intraoperative perforation of the sinus membrane during MSA was not observed in any of the patients.

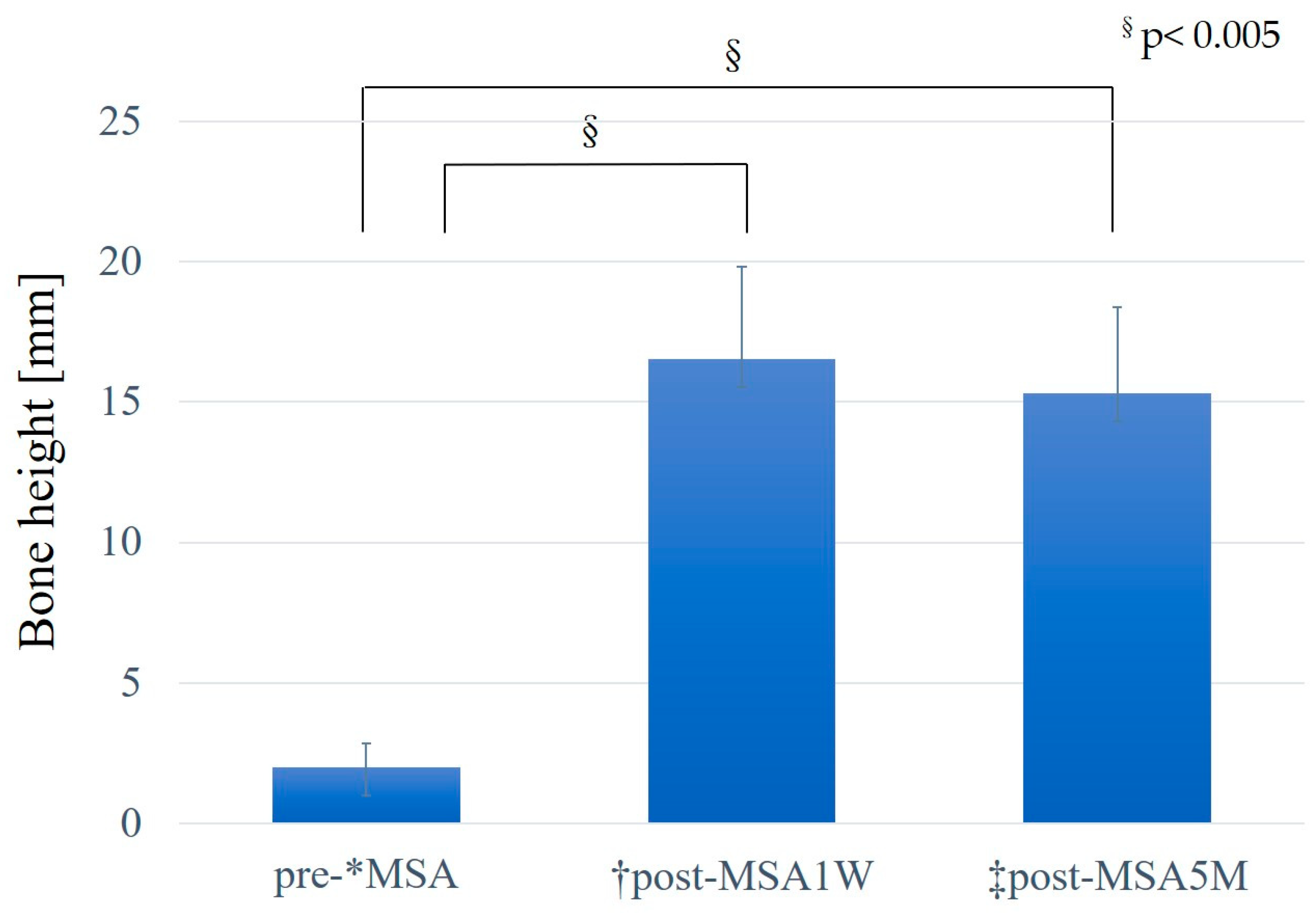

The mean preoperative existing bone height was 2.0 ± 0.8 mm, and the mean post-MSA bone height was 16.6 ± 3.3 mm post-MSA1W and 15.3 ± 3.1 mm post-MSA5M. Compared with the pre-MSA value, bone height increased significantly at both post-MSA1W and post-MSA5M (p < 0.005). However, no difference was observed in bone height between post-MSA1W and post-MSA5M (

Figure 8). Moreover, the reduction rate in maxillary sinus augmentation from post-MSA1W to post-MSA5M was 8.38% ± 4.88%.

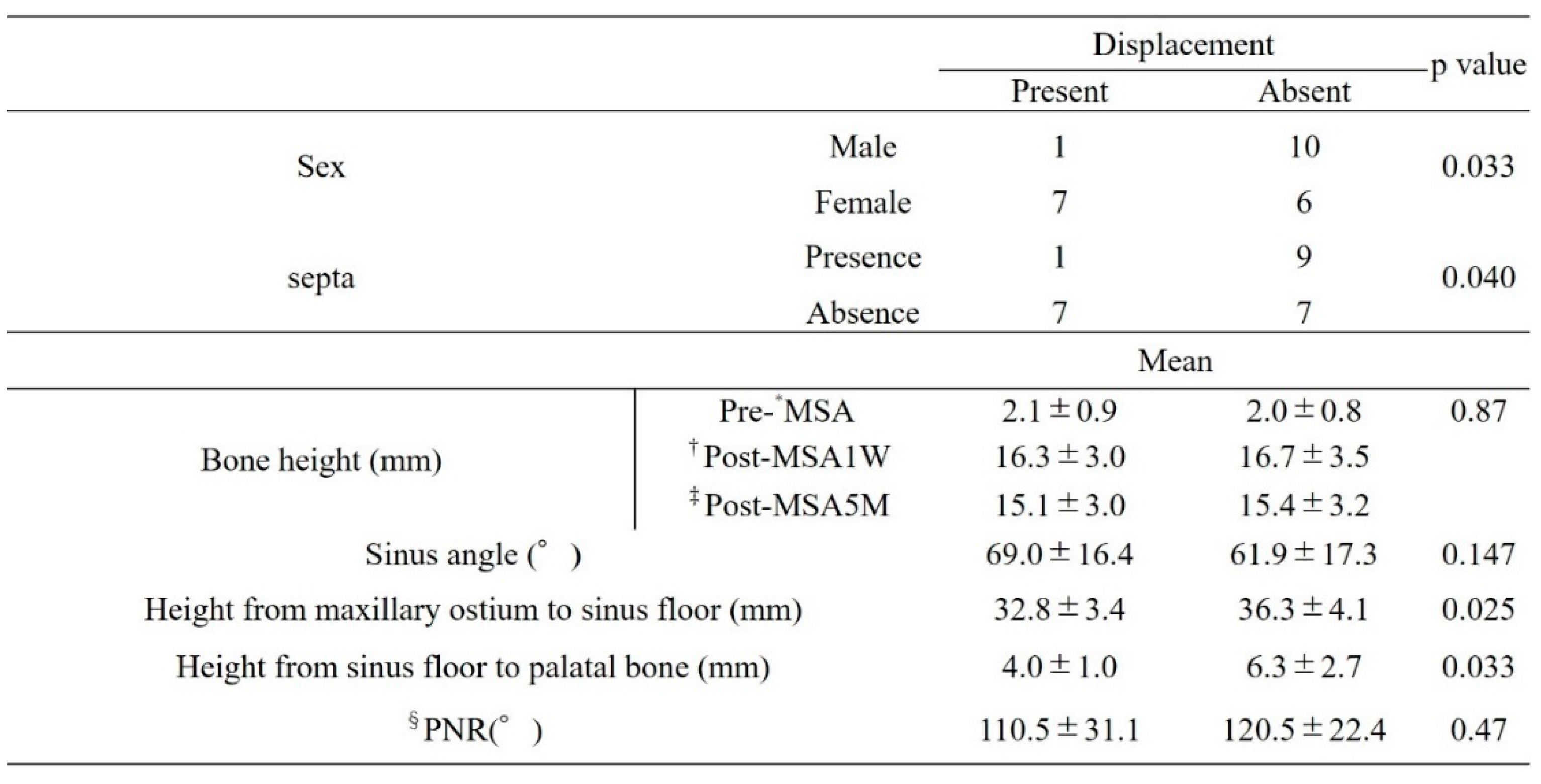

3.1. Factors related to bone graft displacement

Factors related to bone displacement from the open window included sex, presence of the septa, height from the maxillary sinus floor to the palatal bone, and height from the maxillary sinus floor to the maxillary ostium. Although not significantly different, the group without bone displacement showed greater bone height at both post-MSA1W and post-MSA5M (

Table 3).

Bone displacement was more likely in women than in men (p = 0.033), in those without a septum (p = 0.040), and in those with smaller distances from the maxillary sinus floor to the palatal bone and from the maxillary sinus floor to the maxillary ostium (p = 0.033 and p = 0.025, respectively).

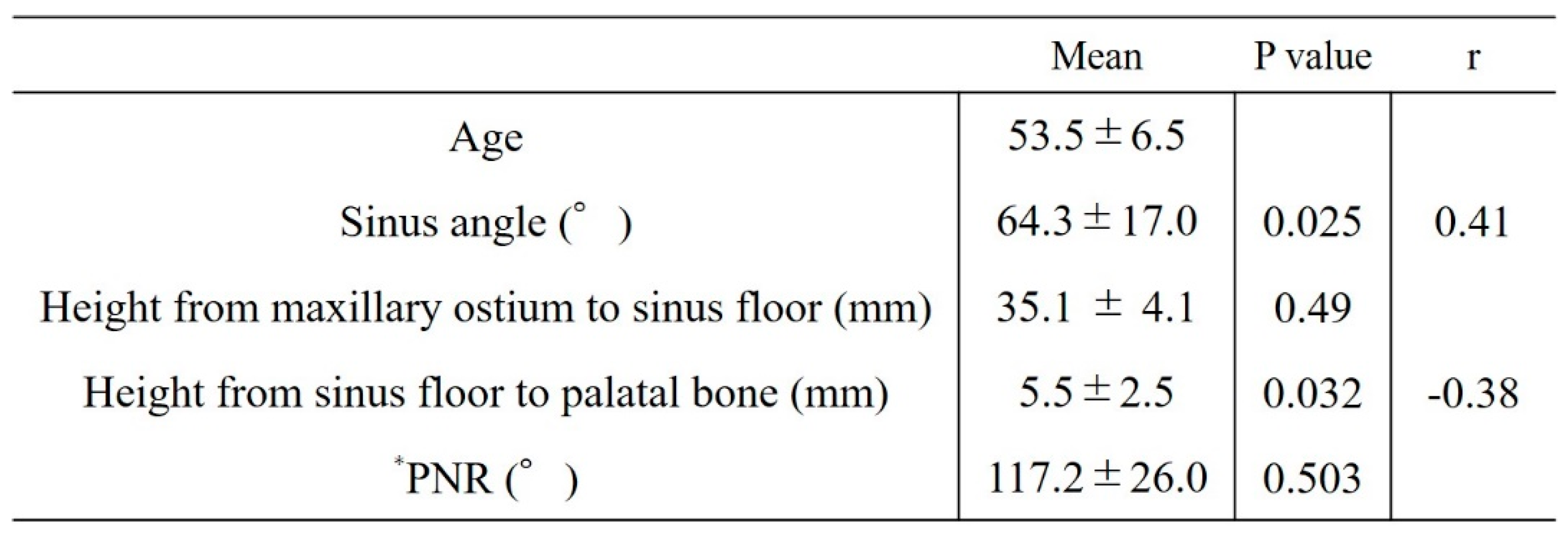

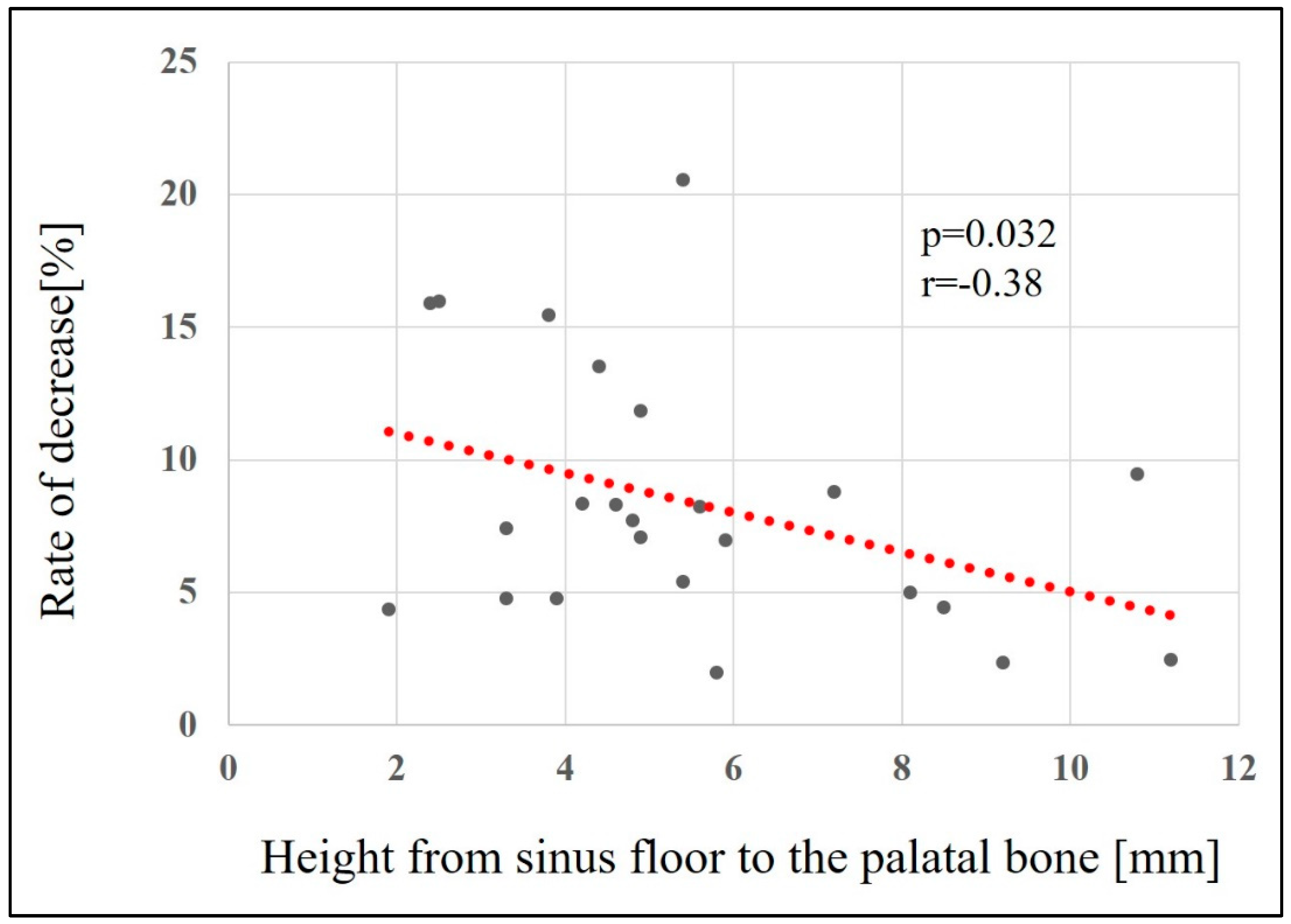

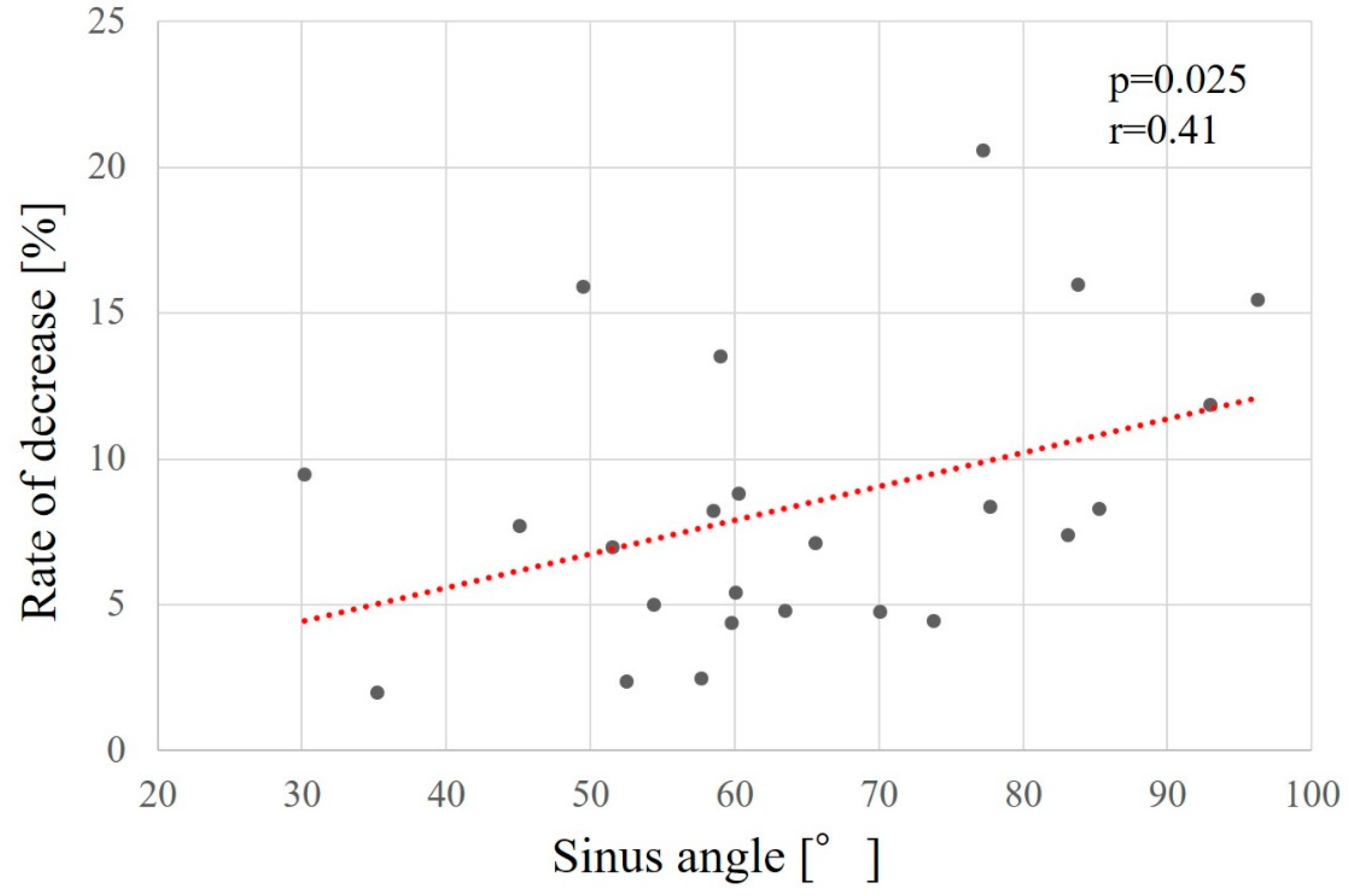

3.2. Factors associated with reduced augmentation (Table 4)

Factors related to reduced maxillary sinus augmentation were the height from the maxillary sinus floor to the palatal bone and the sinus angle. The smaller the height from the maxillary sinus floor to the palatal bone and the greater the sinus angle, the greater the decrease in augmentation (p = 0.032, r = -0.38 [

Figure 9] and p = 0.025, r = 0.41 [

Figure 10], respectively).

Table 4.

Factors related to decreased maxillary sinus augmentation.

Table 4.

Factors related to decreased maxillary sinus augmentation.

4. Discussion

The GMEM-B2 membrane used in the present study is a bioabsorbable polymer P(LA/CL) with a simple composition and is already being used as a raw material in artificial dura mater grafts.[

18] Clinical studies of maxillary sinus augmentation have reported that when the existing bone height is <4 mm in maxillary molar defects, maxillary sinus augmentation using the lateral window technique yields good clinical outcomes.[

3,

16] Particularly, in two-stage maxillary sinus augmentation, placement of a barrier membrane in the open window is essential to prevent connective tissue from penetrating into the grafted bone material and maintain the elevation of the grafted bone. This clinical study aimed to evaluate the clinical usefulness of GMEM-B2 as a barrier membrane in MSA by measuring the bone height and bone graft displacement from the open window after MSA.

Previous studies on the effectiveness of barrier membranes have evaluated MSA with various barrier membranes. In a meta-analysis, Suarez-Lopez del Amo et al.[

19] reported that placing a barrier membrane in the open window did not affect the amount of vital bone formation for at least 6 months after surgery. Other studies [

7,

20,

21] have reported that membrane use does not substantially increase vital bone volume. In contrast, Tarnow et al. [

13] reported a significant increase in vital bone volume in the group using a barrier membrane (25.5%) than in the group without a barrier membrane (11.9%), indicating a lack of consensus regarding the usefulness of barrier membranes. However, these studies did not adequately control for many relevant factors, including open window size,[

22] preoperative existing bone height,[

23] bone graft material, buccopalatal dimensions of the sinus cavity,[

24] and the biopsy collection site. In particular, for the biopsy collection site, the location and depth of the tissue sample may influence the mineralisation and the degree of bone formation. Most clinical studies collected biopsy samples from the alveolar crest, whereas the barrier membranes are placed in the open window.[

24] Therefore, we believe that previous studies may not have evaluated the true effects of barrier membranes. Moreover, a systematic review by Starch-Jensen et al. [

25] on MSA with and without barrier membranes showed no statistically significant difference in the implant survival rate or in newly formed bone and non-mineralised tissue after MSA concerning the use of a barrier membrane. The placement of a barrier membrane in an open window is effective because it increases the proportion of neonatal bone and decreases the proliferation of non-mineralised tissue, suggesting that barrier membranes are beneficial and improve bone regeneration.

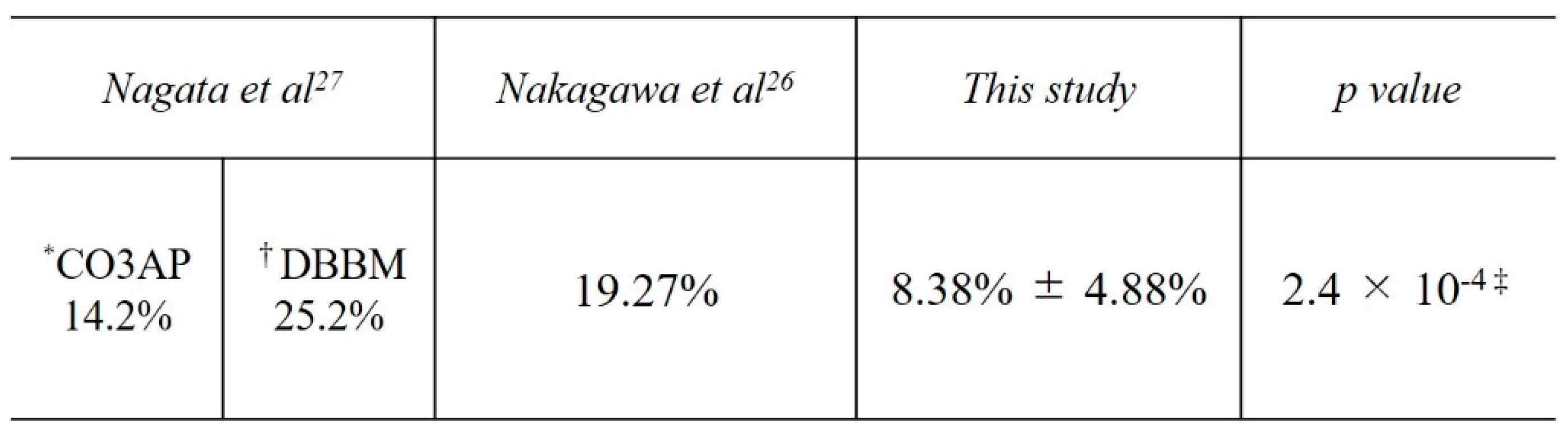

In the present study, the mean bone height pre-MSA was 2.02 ± 0.81 mm, whereas the mean height post-MSA1W was 16.26 ± 3.09 mm and post-MSA5M was 15.05 ± 2.99 mm, indicating a mean reduction of 8.38% ± 4.88% in augmentation. In a similar study that did not use barrier membranes, Nakagawa et al. [

26] investigated bone height immediately after MSA and at 7 ± 2 months by CBCT when using CO3Ap, a bone graft material similar to that used in our study. The bone height immediately after MSA was 13.3 ± 1.7 mm and that at 7 ± 2 months after SFA was 10.7 ± 1.9 mm, a reduction of 19.27%. In a study comparing CO3AP to deproteinized bovine bone mineral (DBBM; Bio-OssⓇ) as a control group that was similar to the present study but did not use barrier membranes, Nagata et al.[

27] evaluated the bone graft volume reduction rate immediately after MSA and 6 months postoperatively, reporting rates of 14.2% for CO3AP and 25.2% for DBBM. Compared with studies that did not use barrier membranes, this study showed a significantly lower reduction in bone height (

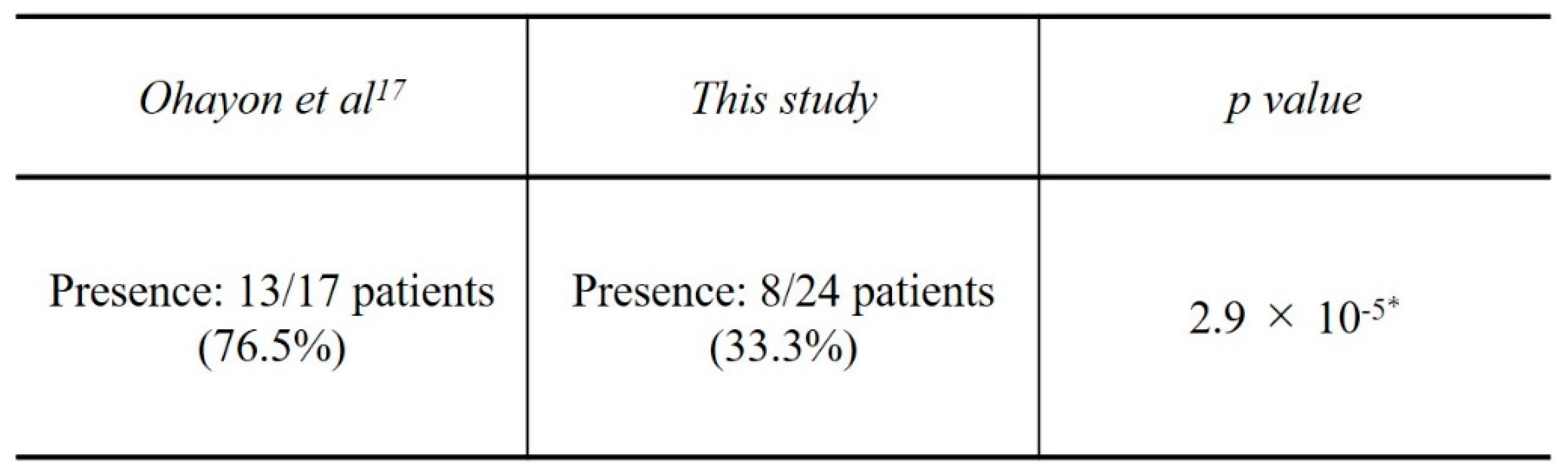

Table 5). Moreover, the study observed bone graft displacement in eight patients (33.3%). Few studies have examined bone graft displacement. Ohayon et al. [

17] investigated the amount of bone displacement from open windows with and without collagen barrier membranes. They reported that bone graft displacement occurred in 76.5% of patients using a collagen barrier membrane. GMEM-B2 appears to be effective as a barrier membrane since the bone graft displacement rate in the present study was significantly smaller than that obtained with collagen barrier membranes in the study by Ohayon et al. (

Table 6).

The results of our study also showed that sinus angle and the height from the palatal bone to the maxillary sinus floor were factors related to reduced maxillary sinus elevation, with smaller distances from the palatal bone to the maxillary sinus floor and larger sinus angles being associated with larger decrease rates. Factors related to bone graft displacement included sex, presence of a septum, height from the maxillary sinus floor to the palatal bone, and height from the maxillary sinus floor to the natural mouth. Bone displacement was more likely to occur in women, those without a septum, and those with smaller distances from the palatal bone to the maxillary sinus floor and smaller distances from the maxillary sinus floor to the natural mouth. In the study by Ohayon et al. [

17] on bone displacement, the authors stated that swelling of the maxillary sinus floor mucosa after MSA increases pressure in the sinus cavity and places physiological pressure on the bone graft material; consequently, if the open window is not covered with a membrane, the bone graft material will move toward the open window and even displace through it. They reported that postoperative bone graft displacement is associated with sinus membrane swelling, exacerbated by factors that increase sinus pressure, such as sniffing, sneezing, and bleeding reactions, and that pressure from sinus membrane swelling and bleeding can cause bone graft material to displace outside the sinus cavity. Consistent with reports showing that the volume of the maxillary sinus is smaller in women than in men,[

28] the results of the present study suggest that maxillary sinuses that are smooth, have smaller volumes, and lack a septal wall may be increase bone displacement through the open window, which reduces the amount of augmentation.

The limitations of this study include the absence of pathological assessments or evaluations and comparisons with other membranes because this was a single-arm study. Pathological assessments would require controlling for the size and location of the open window and the tissue collection site, which were not controlled in previous reports. Long-term follow-up studies on the relationship with the anatomical morphology of the maxillary sinus, including the ostiomeatal complex, and changes in bone mass after MSA are needed.

5. Conclusions

In comparison with other previously reported membranes, the P(LA/CL) membrane could serve as a useful barrier membrane for MSA. Factors related to bone graft displacement included sex, presence of a septum, height from the maxillary sinus floor to the palatal bone, and height from the maxillary sinus floor to the natural mouth.

Author Contributions

Kikue Yamaguchi: Data curation; Conceptualization; Methodology; Validation; Investigation; Writing-original draft preparation; Visualization. Motohiro Munakata: Conceptualization; Methodology, Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing-review and editing; Supervision. Daisuke Sato: Validation; Investigation; Resources; Writing-review and editing. Yu Kataoka; Resources; project administration. Ryota Kawamata; Software; Formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of SHOWA University Clinical Research Review Board (approval number jRCTs032190123 and Oct 19th, 2019 of approval) and by the Institutional Review Board of Showa University Dental Hospital (approval No. SUDH0043). It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written informed consent for this study. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants gave written informed consent for this study. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

They would like to thank Editage (www. editage.com) for English language editing. No funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abe, G.L.; Sasaki, J.I.; Katata, C.; Kohno, T.; Tsuboi, R.; Kitagawa, H.; Imazato, S. Fabrication of Novel Poly(Lactic Acid/Caprolactone) Bilayer Membrane for GBR Application. Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson, B.E.; Tan, W.C.; Zwahlen, M.; Lang, N.P. A Systematic Review of the Success of Sinus Floor Elevation and Survival of Implants Inserted in Combination With Sinus Floor Elevation. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 216–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starch-Jensen, T.; Aludden, H.; Hallman, M.; Dahlin, C.; Christensen, A.E.; Mordenfeld, A. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Long-Term Studies (Five or More Years) Assessing Maxillary Sinus Floor Augmentation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testori, T.; Weinstein, T.; Taschieri, S.; Wallace, S.S. Risk Factors in Lateral Window Sinus Elevation Surgery. Periodontol. 2000 2019, 81, 91–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artzi, Z.; Kozlovsky, A.; Nemcovsky, C.E.; Weinreb, M. The Amount of Newly Formed Bone in Sinus Grafting Procedures Depends on Tissue Depth as Well as the Type and Residual Amount of the Grafted Material. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galindo-Moreno, P.; Moreno-Riestra, I.; Ávila-Ortiz, G.; Padial-Molina, M.; Gallas-Torreira, M.; Sánchez-Fernández, E.; Mesa, F.; Wang, H.L.; O’Valle, F. Predictive Factors for Maxillary Sinus Augmentation Outcomes: A Case Series Analysis. Implant Dent. 2012, 21, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, A.; Ricci, M.; Covani, U.; Nannmark, U.; Azarmehr, I.; Calvo-Guirado, J.L. Maxillary Sinus Augmentation Using Prehydrated Corticocancellous Porcine Bone: Hystomorphometric Evaluation After 6 Months. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2012, 14, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassling, V.; Purcz, N.; Braesen, J.H.; Will, M.; Gierloff, M.; Behrens, E.; Açil, Y.; Wiltfang, J. Comparison of Two Different Absorbable Membranes for the Coverage of Lateral Osteotomy Sites in Maxillary Sinus Augmentation: A Preliminary Study. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2013, 41, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; European Workshop on Periodontology Group, C. Advances in Bone Augmentation to Enable Dental Implant Placement: Consensus Report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol., European Workshop on Periodontology Group C 2008, 35, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickert, D.; Slater, J.J.R.H.; Meijer, H.J.A.; Vissink, A.; Raghoebar, G.M. Maxillary Sinus Lift With Solely Autogenous Bone Compared to a Combination of Autogenous Bone and Growth Factors or (Solely) Bone Substitutes. A Systematic Review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 41, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, S.S.; Froum, S.J. Effect of Maxillary Sinus Augmentation on the Survival of Endosseous Dental Implants. A Systematic Review. Ann. Periodontol. 2003, 8, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artese, L.; Piattelli, A.; Di Stefano, D.A.; Piccirilli, M.; Pagnutti, S.; D’Alimonte, E.; Perrotti, V. Sinus Lift With Autologous Bone Alone or in Addition to Equine Bone: An Immunohistochemical Study in Man. Implant Dent. 2011, 20, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, B.S.; Margolin, M.D.; Cogan, A.G.; Taylor, M.; Wollins, J. Residual Lateral Wall Defects Following Sinus Grafting With Recombinant Human Osteogenic Protein-1 or Bio-Oss in the Chimpanzee. Int. J. Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1998, 18, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wallace, S.S.; Tarnow, D.P.; Froum, S.J.; Cho, S.C.; Zadeh, H.H.; Stoupel, J.; Del Fabbro, M.; Testori, T. Maxillary Sinus Elevation by Lateral Window Approach: Evolution of Technology and Technique. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2012, 12, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnow, D.P.; Wallace, S.S.; Froum, S.J.; Rohrer, M.D.; Cho, S.C. Histologic and Clinical Comparison of Bilateral Sinus Floor Elevations With and Without Barrier Membrane Placement in 12 Patients: Part 3 of an Ongoing Prospective Study. Int. J. Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2000, 20, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Tawil, G.; Mawla, M. Sinus Floor Elevation Using a Bovine Bone Mineral (Bio-Oss) With or Without the Concomitant Use of a Bilayered Collagen Barrier (Bio-Gide): A Clinical Report of Immediate and Delayed Implant Placement. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2001, 16, 713–721. [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon, L.; Taschieri, S.; Friedmann, A.; Del Fabbro, M. Bone Graft Displacement After Maxillary Sinus Floor Augmentation With or Without Covering Barrier Membrane: A Retrospective Computed Tomographic Image Evaluation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2019, 34, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, G.; Hoshino, J.; Kinoshita, Y.; Sugita, Y.; Kubo, K.; Maeda, H.; Arimura, H.; Matsuda, S.; Ikada, Y.; Kinoshita, Y. Evaluation of Guided Bone Regeneration With Poly(Lactic Acid-co-Glycolic Acid-co-ε-Caprolactone) Porous Membrane in Lateral Bone Defects of the Canine Mandible. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2012, 27, 587–594. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-López Del Amo, F.; Ortega-Oller, I.; Catena, A.; Monje, A.; Khoshkam, V.; Torrecillas-Martínez, L.; Wang, H.L.; Galindo-Moreno, P. Effect of Barrier Membranes on the Outcomes of Maxillary Sinus Floor Augmentation: A Meta-analysis of Histomorphometric Outcomes. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2015, 30, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.S.; Kan, J.Y.K.; Boyne, P.J.; Goodacre, C.J.; Lozada, J.L.; Rungcharassaeng, K. The Effects of Resorbable Membrane on Human Maxillary Sinus Graft: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2009, 24, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hallman, M.; Sennerby, L.; Lundgren, S. A Clinical and Histologic Evaluation of Implant Integration in the Posterior Maxilla After Sinus Floor Augmentation With Autogenous Bone, Bovine Hydroxyapatite, or a 20:80 Mixture. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2002, 17, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avila-Ortiz, G.; Wang, H.L.; Galindo-Moreno, P.; Misch, C.E.; Rudek, I.; Neiva, R. Influence of Lateral Window Dimensions on Vital Bone Formation Following Maxillary Sinus Augmentation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2012, 27, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avila-Ortiz, G.; Neiva, R.; Galindo-Moreno, P.; Rudek, I.; Benavides, E.; Wang, H.L. Analysis of the Influence of Residual Alveolar Bone Height on Sinus Augmentation Outcomes. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2012, 23, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, G.; Wang, H.L.; Galindo-Moreno, P.; Misch, C.E.; Bagramian, R.A.; Rudek, I.; Benavides, E.; Moreno-Riestra, I.; Braun, T.; Neiva, R. The Influence of the Bucco-Palatal Distance on Sinus Augmentation Outcomes. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starch-Jensen, T.; Mordenfeld, A.; Becktor, J.P.; Jensen, S.S. Maxillary Sinus Floor Augmentation With Synthetic Bone Substitutes Compared With Other Grafting Materials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Implant Dent. 2018, 27, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, T.; Kudoh, K.; Fukuda, N.; Kasugai, S.; Tachikawa, N.; Koyano, K.; Matsushita, Y.; Sasaki, M.; Ishikawa, K.; Miyamoto, Y. Application of Low-Crystalline Carbonate Apatite Granules in 2-Stage Sinus Floor Augmentation: A Prospective Clinical Trial and Histomorphometric Evaluation. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2019, 49, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, K.; Fuchigami, K.; Kitami, R.; Okuhama, Y.; Wakamori, K.; Sumitomo, H.; Kim, H.; Okubo, M.; Kawana, H. Comparison of the Performances of Low-Crystalline Carbonate Apatite and Bio-Oss in Sinus Augmentation Using Three-Dimensional Image Analysis. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2021, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Munakata, M.; Kataoka, Y.; Uesugi, T.; Shimoo, Y. Effects of Missing Teeth and Nasal Septal Deviation on Maxillary Sinus Volume: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2022, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Study protocol. *MSA, maxillary sinus augmentation with a lateral approach; †CT, computed tomography.

Figure 1.

Study protocol. *MSA, maxillary sinus augmentation with a lateral approach; †CT, computed tomography.

Figure 2.

Barrier membrane material (GMEM-B2). A bilayer P(LA/CL) membrane (GMEM-B2) has a white membrane structure molded from a bioabsorbable polymer. (a) Structural diagram. GMEM-B2 consists of two layers, a solid layer and a porous layer, (b) GMEM-B2 is a rectangular film measuring approximately 30 mm × 40 mm and has a thickness of approximately 200 μm. (c) CT image. (d, e) SEM image of a solid layer and a porous layer.*CT, computed tomography; †SEM, scanning electron microscopy.

Figure 2.

Barrier membrane material (GMEM-B2). A bilayer P(LA/CL) membrane (GMEM-B2) has a white membrane structure molded from a bioabsorbable polymer. (a) Structural diagram. GMEM-B2 consists of two layers, a solid layer and a porous layer, (b) GMEM-B2 is a rectangular film measuring approximately 30 mm × 40 mm and has a thickness of approximately 200 μm. (c) CT image. (d, e) SEM image of a solid layer and a porous layer.*CT, computed tomography; †SEM, scanning electron microscopy.

Figure 3.

Surgical protocol of the maxillary sinus augmentation operation with lateral window technique. (a) Pre-operation (b) A mucoperiosteal flap is performed. (c) Dimensions of the minimally invasive lateral window. (d) After elevation of the basilar membrane of the sinus, the elevated space is filled with CO3Ap granules. (e) The bony window is repositioned, (f) A GMEM-B2 membrane is placed over it, and the mucoperiosteal flap is sutured.

Figure 3.

Surgical protocol of the maxillary sinus augmentation operation with lateral window technique. (a) Pre-operation (b) A mucoperiosteal flap is performed. (c) Dimensions of the minimally invasive lateral window. (d) After elevation of the basilar membrane of the sinus, the elevated space is filled with CO3Ap granules. (e) The bony window is repositioned, (f) A GMEM-B2 membrane is placed over it, and the mucoperiosteal flap is sutured.

Figure 4.

Presence and amount of bone graft displacement (mm).

Figure 4.

Presence and amount of bone graft displacement (mm).

Figure 5.

Maxillary sinus angle (between the lateral and medial wall of maxillary sinus).

Figure 5.

Maxillary sinus angle (between the lateral and medial wall of maxillary sinus).

Figure 6.

Palatonasal recess ([PNR], between the roof of the hard palate and the lateral wall of the nasal cavity).

Figure 6.

Palatonasal recess ([PNR], between the roof of the hard palate and the lateral wall of the nasal cavity).

Figure 7.

Distance from the maxillary sinus floor to the maxillary ostium (yellow arrow) and distance from the maxillary sinus floor to the palatal bone (blue arrow).

Figure 7.

Distance from the maxillary sinus floor to the maxillary ostium (yellow arrow) and distance from the maxillary sinus floor to the palatal bone (blue arrow).

Figure 8.

Changes in bone height. *MSA, maxillary sinus augmentation with a lateral approach. †Post-MSA1W, 1 week after MSA. ‡Post-MSA5M, 5–6 months after MSA. §P < 0.005, Multiple comparisons among the three groups were performed using the Friedman test.

Figure 8.

Changes in bone height. *MSA, maxillary sinus augmentation with a lateral approach. †Post-MSA1W, 1 week after MSA. ‡Post-MSA5M, 5–6 months after MSA. §P < 0.005, Multiple comparisons among the three groups were performed using the Friedman test.

Figure 9.

Relationship between height from sinus floor to the palatal bone and the rate of bone height reduction.

Figure 9.

Relationship between height from sinus floor to the palatal bone and the rate of bone height reduction.

Figure 10.

Relationship between the sinus angle and the rate of bone height reduction.

Figure 10.

Relationship between the sinus angle and the rate of bone height reduction.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 3.

Factors related to bone graft displacement.

Table 3.

Factors related to bone graft displacement.

Table 5.

Reduction in bone height from a week to 5–6 months postoperatively.

Table 5.

Reduction in bone height from a week to 5–6 months postoperatively.

Table 6.

Rate of bone graft displacement.

Table 6.

Rate of bone graft displacement.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).