Submitted:

23 August 2023

Posted:

25 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Aim

3.2. Design

3.3. Details of Sensors Used

- TGS 826: The sensing element of TGS826 is a metal oxide semiconductor that has low conductivity in clean air. In the presence of a detectable gas, the sensor’s conductivity increases depending on the gas concentration in the air. A simple electrical circuit can convert the change in conductivity to an output signal corresponding to the gas concentration. The TGS826 has a high sensitivity to ammonia gas. The sensor can detect concentrations as low as 30 ppm in the air and is ideally suited to critical safety-related applications such as the detection of ammonia leaks in refrigeration systems and ammonia detection in the agricultural field [18].

- TGS 2610: TGS2610 is a semiconductor-type gas sensor that combines very high sensitivity to LP gas with low power consumption and long life. Due to the miniaturisation of its sensing chip, TGS2610 requires a heater current of only 56mA and the device is housed in a standard TO-5 package. The TGS2610 is available in two different models with different external housings but identical sensitivity to LP gas. Both models can satisfy the requirements of performance standards such as UL1484 and EN50194. TGS2610-C00 possesses a small size and quick gas response, making it suitable for gas leakage checkers. TGS2610-D00 uses filter material in its housing, eliminating the influence of interference gasses such as alcohol, resulting in a highly selective response to LP gas. This feature makes the sensor ideal for residential gas leakage detectors, which require durability and resistance against interference gas [19].

- TGS 822: The sensing element of 822 Figaro gas sensors is a tin dioxide (SnO2) semiconductor with low conductivity in clean air. In the presence of a detectable gas, the sensor’s conductivity increases depending on the gas concentration in the air. A simple electrical circuit can convert the change in conductivity to an output signal corresponding to the gas concentration. The TGS 822 is highly sensitive to the vapours of organic solvents and other volatile vapours. It also sensitive to combustible gasses such as carbon monoxide, making it an excellent general-purpose sensor. Also available with a ceramic base that is highly resistant to severe environments as high as 200°C (in TGS 823) [20].

- TGS 2602: The sensing element consists of a metal oxide semiconductor layer formed on the alumina substrate of a sensing chip together with an integrated heater. The TGS 2602 is highly sensitive to low concentrations of odourous gasses such as ammonia and HS generated from waste materials in office and home environments. The sensor also susceptible to low concentrations of VOCs, such as toluene emitted from wood finishing and construction products. Due to the miniaturisation of the sensing chip, TGS 2602 requires a heater current of only 56mA and the device is housed in a standard TO-5 package [21].

- TGS 2600: The sensing element consists of a metal oxide semiconductor layer formed on an alumina substrate of a sensing chip together with an integrated heater. In the presence of a detectable gas, the sensor’s conductivity increases depending on the gas concentration in the air. The TGS 2600 is highly sensitive to low concentrations of gaseous air contaminants in cigarette smoke, such as hydrogen and carbon monoxide. The sensor can detect hydrogen at a level of several ppm. Due to the miniaturisation of the sensing chip, TGS 2600 requires a heater current of only 42mA and the device is housed in a standard TO-5 package [22].

- TGS 2603: The sensing element consists of a metal oxide semiconductor layer formed on an alumina substrate of a sensing chip together with an integrated heater. In the presence of a detectable gas, the sensor’s conductivity increases depending on the gas concentration in the air. The TGS 2603 is highly sensitive to low concentrations of odourous gasses such as anime-series and sulfurous odour generated from waste materials or spoiled foods such as fish. By utilising the change ratio of sensor resistance from the resistance in clean air as the relative response, human perception of air contaminants can be simulated and practical air quality control can be achieved [23].

- TGS 2620: The sensing element consists of a metal oxide semiconductor layer formed on an alumina substrate of a sensing chip together with an integrated heater. In the presence of a detectable gas, the sensor’s conductivity increases depending on the gas concentration in the air. The TGS 2620 is highly sensitive to the vapours of organic solvents and other volatile vapours, making it suitable for organic vapour detectors/alarms. Due to the miniaturisation of the sensing chip, TGS 2620 requires a heater current of only 42mA and the device is housed in a standard TO-5 package [24].

- MQ138: The sensor measures the change in conductivity of a tin dioxide SnO semiconductor when exposed to VOCs. In clean air, SnO has low conductivity. However, when VOCs are present, they react with the SnO and increase its conductivity. The change in conductivity can be measured as a voltage change, which can then be used to determine the concentration of VOCs in the air. The MQ138 sensor is sensitive to various of VOCs, including formaldehyde, benzene, toluene, and acetone. It has a working range of 1 to 100 ppm for benzene [25].

- DHT 22: DHT22 is a commonly used temperature and humidity sensor. The sensor comes with a dedicated NTC to measure temperature and an 8-bit microcontroller to output temperature and humidity values as serial data. The sensor can measure temperature from -40°C to 80°C and humidity from 0% to 100% with an accuracy of ±1°C and ±1% [26].

3.4. Methodology

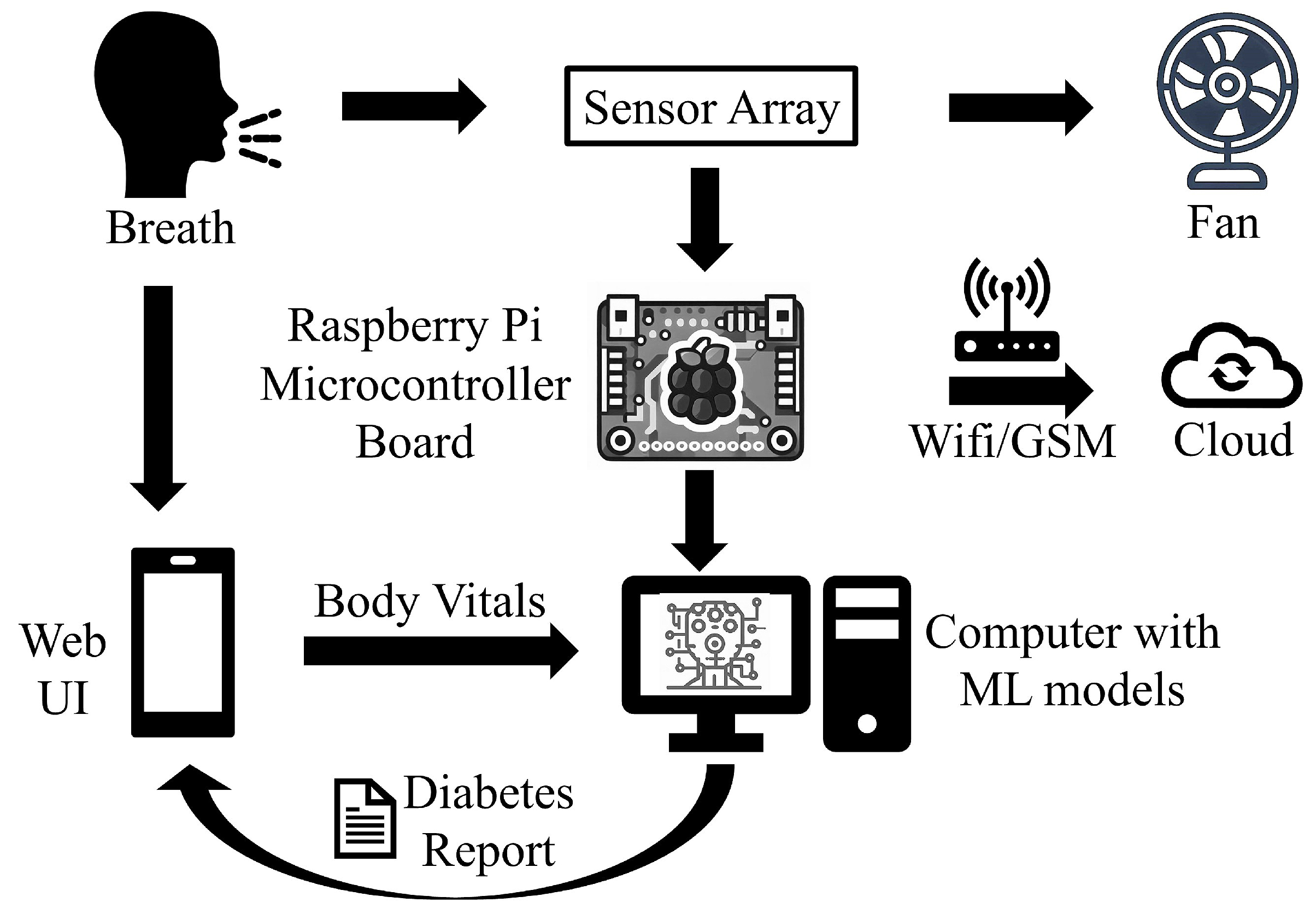

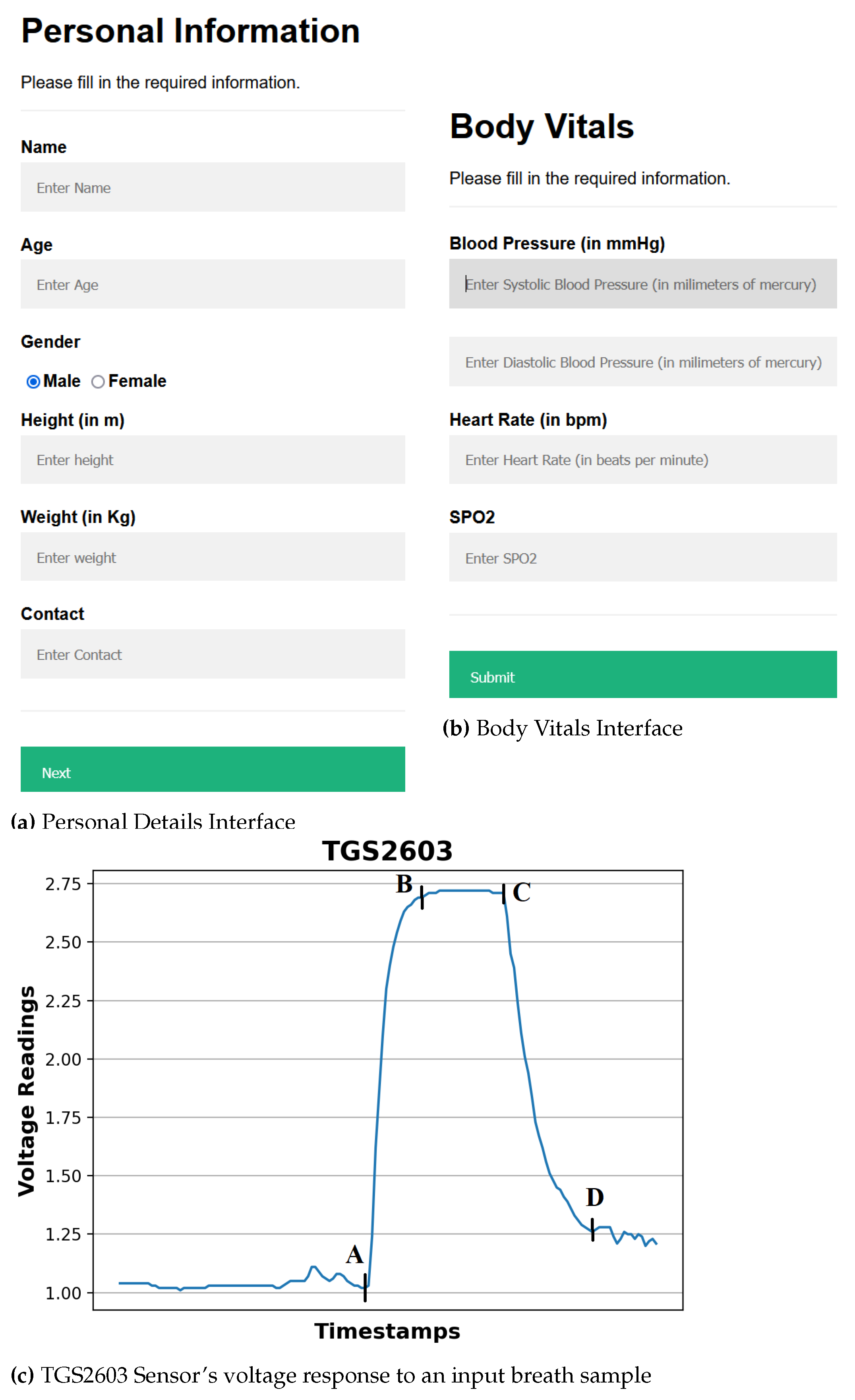

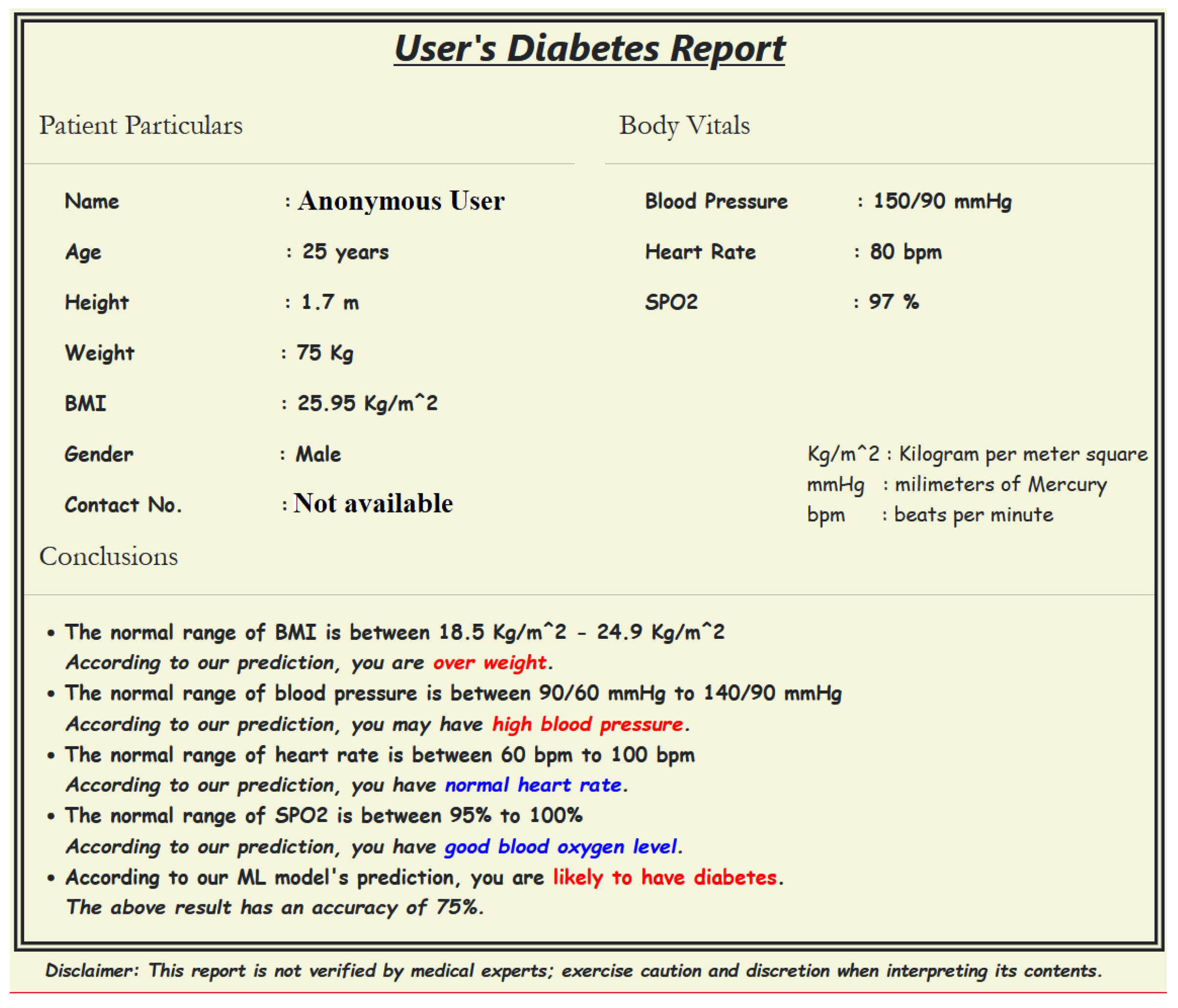

- Providing input details using a web-based interface: The procedure starts by entering the user’s demographic and body vitals information using a web-based interface (Figure 3a,b). The demographics include name, age, gender, height, and weight. To record the body vitals of a user, we make him sit in a stable position, rest for five minutes (to make his vitals stable if he has done some physical activity), and then record his blood pressure, heart rate, and blood oxygen level using standard digital health devices available in the market. These measures can also be self-recorded by a user using digital health devices or a smartwatch and can be entered into the web-based interface.

- Calibrating the sensors: To ensure accurate sensor readings, we calibrate the sensors to establish stable baselines by validating their readings under reference conditions using fresh air. This means that we expose the sensors to a known concentration of VOCs and measure their output. We can then use this data to create a calibration curve, which can be used to correct the sensor readings for any variations. To obtain a stable baseline from the sensor output, sensors need to be preheated with a microheater of the gas sensor. Once the sensor’s output stabilizes under fresh air condition breath samples signatures are obtained from the sensor array.

- Preheat the sensors: The temperature of the sensors goes up to a relatively stable level during use, which results in a change in baseline response of the sensors. Therefore, the device should be switched on for about 20 minutes until the baseline response shown on the host computer is stable.

- Regular weekly calibration of the sensors: In addition to the initial calibration, we also perform regular calibrations every two weeks to reduce the time drift. This is done by exposing the sensors to a set of 10 different standard gas samples, which include VOCs, H, CO, NH, and healthy breath samples, with two different concentrations respectively. The results of the regular calibrations are used to update the calibration curve, which ensures that the sensor readings remain accurate over time.

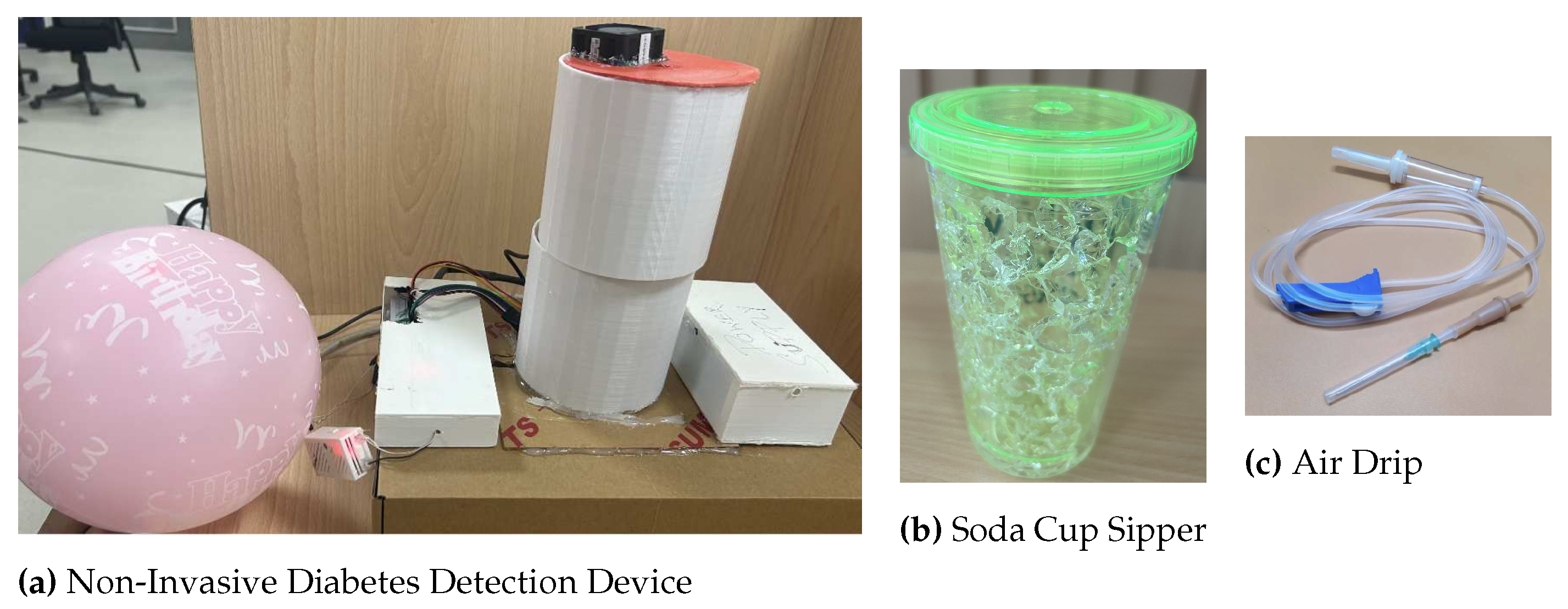

- Collecting the breath sample and infusing it into the device: A breath sample collected in a balloon is infused into the sensor-based setup with the help of a drip pipe mounted on top of the soda cup cap. The drip pipe one end is attached to the mouth of the inflated balloon, housing the breath sample, while the other end is connected to the soda cup cap containing the embedded sensors.

- Processing the breath sample and recording the data: Upon interaction with the VOCs present in the breath sample, the sensors show deflection from their baseline readings (as Figure 3c). The recorded deflection data conveyed through the MQTT protocol is directed into an InfluxDB time series database. The Grafana visualisation dashboard facilitates the visualisation of real-time sensor responses. The experimental setup comprises a Raspberry Pi hosting the MQTT server, Grafana, Node-RED, and Influx DB running as docker containers. The sensor voltage readings act as sample characteristics as they depend on the concentration of VOCs in the breath sample.

- Getting the setup ready for the following sample: After a reaction time of two seconds, we remove the cup’s cap and mount it with a fan assembly to expel the breath sample in the device. Once the voltage readings are restored to their baselines, we stop recording them for the present sample. The setup is ready to process the following breath sample.

3.5. Experimental Setting

3.6. Preprocessing the sensor voltages

3.7. Feature Extraction

3.8. ML model development

- Gradient Boosting (GBoost): GBoost a model stage-wise and generalises the model by allowing optimisation of an arbitrary differentiable loss function. Gradient boosting combines weak learners into a single strong learner in an iterative fashion. As each weak learner is added, a new model is fitted to provide a more accurate estimate of the response variable [44,45].

- Decision Tree (DT): A DT is developed by recursively splitting data based on feature values to develop subsets that are as pure as feasible, which means that each subset mainly comprises instances of a single class [46].

- K Nearest Neighbours (KNN): KNN does not make any underlying assumptions about data distribution. Given some prior data (training data), KNN classifies coordinates identified by an attribute [46].

- Ridge: Ridge Regression enhances regular linear regression by slightly changing its cost function, which results in less overfit models [47].

- Lasso: Lasso is a regression analysis method that performs both variable selection and regularisation to enhance the prediction accuracy and interpretability of the resulting statistical model. For Lasso, the coefficient estimates do not need to be unique if covariates are collinear. Lasso’s ability to perform subset selection relies on the form of the constraint and has a variety of interpretations, including in terms of geometry, Bayesian statistics and convex analysis [48,49].

- ElasticNet (ENet): ENet combines the two most popular regularised variants of linear regression: Ridge and Lasso. Ridge utilises an L2 penalty, and Lasso uses an L1 penalty. ENet uses both the L2 and the L1 penalty [50].

- Logistic Regression: It is used for predicting the categorical dependent variable using a given set of independent variables. Logistic regression predicts the output of a categorical dependent variable. Therefore the outcome must be a categorical or discrete value. It can be either Yes or No, 0 or 1, true or False, etc., but instead of giving the exact value as 0 and 1, it gives the probabilistic values between 0 and 1 [51].

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): SVM operates by determining the appropriate hyperplane for separating various classes in the data space. The hyperplane is chosen to maximise the margin, which is the distance between the hyperplane and the nearest data points of each class, also known as support vectors [52].

- eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): XGBoost is an open-source software library with a regularising gradient boosting framework for C++, Java, Python, R, Julia, Perl, and Scala. It works on Linux, Windows, and macOS. From the project description, it aims to provide a Scalable, Portable and Distributed Gradient Boosting (GBM, GBRT, GBDT) Library. It runs on a single machine, as well as the distributed processing frameworks Apache Hadoop, Apache Spark, Apache Flink, and Dask [8].

- Random Forest (RF): The RF algorithm generates multiple DTs during training by selecting random subsets of the original dataset and random subsets of characteristics for each tree. Each DT in the RF is developed using a technique known as recursive partitioning, which involves repeatedly splitting the data into subsets depending on the most discriminatory attributes, resulting in a tree-like structure [52].

3.9. Evaluation Metrics

3.10. Selecting the best-performing model for Diabetes Prediction

3.11. Ethical consideration

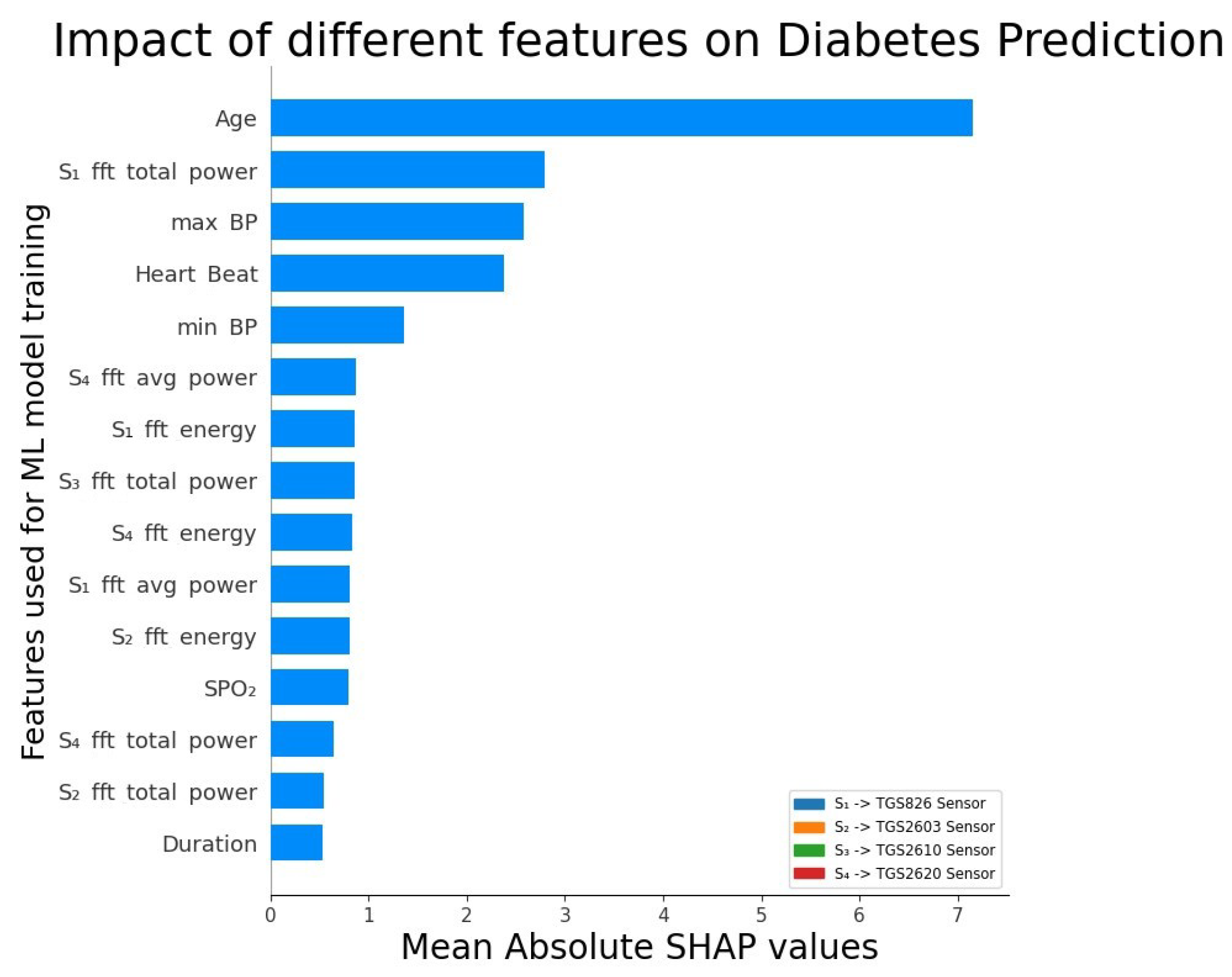

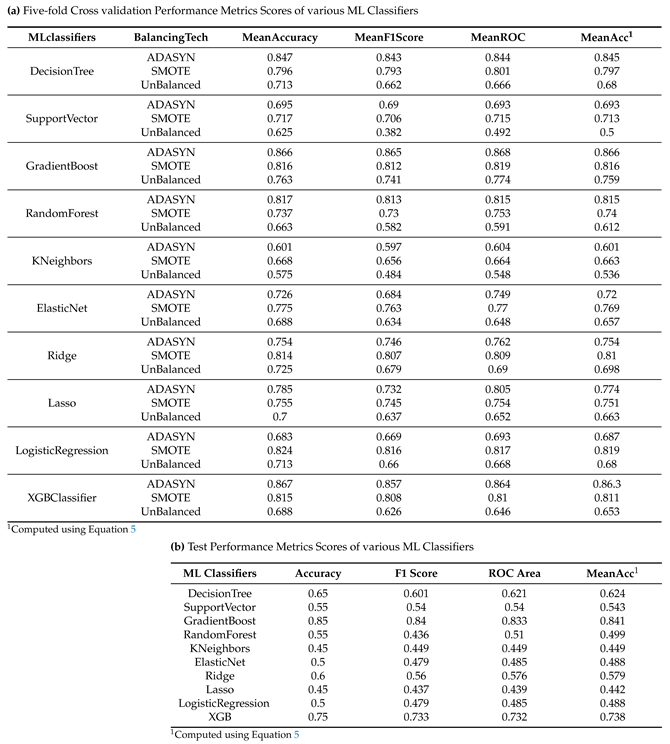

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Ferrannini, E.; Groop, L.; Henry, R.R.; Herman, W.H.; Holst, J.J.; Hu, F.B.; Kahn, C.R.; Raz, I.; Shulman, G.I.; others. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nature reviews Disease primers 2015, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.; Mbanya, J.C.; others. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes research and clinical practice 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roglic, G. WHO Global report on diabetes: A summary. International Journal of Noncommunicable Diseases 2016, 1, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, L.; Zhang, D.; Liu, D. A novel medical e-nose signal analysis system. Sensors 2017, 17, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, K.; Fardindoost, S.; Ravishankara, A.; Tasnim, N.; Hoorfar, M. Exhaled breath analysis for diabetes diagnosis and monitoring: relevance, challenges and possibilities. Biosensors 2021, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenes, J.; Müller, P.; Surridge, N. The technology behind glucose meters: test strips. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics 2008, 10, S–10. [Google Scholar]

- for Drugs, C.A.; in Health (CADTH, T.; others. Systematic review of use of blood glucose test strips for the management of diabetes mellitus. CADTH Technology Overviews 2010, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Paleczek, A.; Grochala, D.; Rydosz, A. Artificial breath classification using XGBoost algorithm for diabetes detection. Sensors 2021, 21, 4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L.; Lu, G. Non-invasive blood glucose monitoring for diabetics by means of breath signal analysis. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2012, 173, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C. Measuring breath acetone for monitoring fat loss. Obesity 2015, 23, 2327–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Chen, Z.; Gong, Z.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, C. Determination of breath acetone in 149 Type 2 diabetic patients using a ringdown breath-acetone analyzer. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2015, 407, 1641–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamungkas, R.A.; Usman, A.M.; Chamroonsawasdi, K.; others. A smartphone application of diabetes coaching intervention to prevent the onset of complications and to improve diabetes self-management: A randomized control trial. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2022, 16, 102537. [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan, M.; Vandelanotte, C.; Fenning, A.; Duncan, M.J. Diabetes self-management smartphone application for adults with type 1 diabetes: randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research 2013, 15, e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Španěl, P.; Smith, D. Progress in SIFT-MS: Breath analysis and other applications. Mass spectrometry reviews 2011, 30, 236–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Sun, W.; Lu, N.; Yan, M.; Wu, Y.; Hua, Z.; Fan, S. Development of a low-cost portable electronic nose for cigarette brands identification. Sensors 2020, 20, 4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Martinez, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, D. Recent advances on linear low-dropout regulators. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2020, 68, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhu, J.; Shen, X.; Lin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Cao, B.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Rao, W.; others. Chinese diabetes datasets for data-driven machine learning. Scientific Data 2023, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan. TGS 826 - for the detection of Ammonia, 2023.

- Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan. TGS 2603 - for the detection of LP Gas, 2023.

- Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan. TGS 2600 - for the detection of Air Contaminants, 2023.

- Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan. TGS 2603 - for the detection of Air Contaminants, 2023.

- Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan. TGS 2600 - for the detection of Air Contaminants, 2023.

- Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan. TGS 2603 - for the detection of Odour and Air Contaminants, 2023.

- Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan. TGS 2603 - for the detection of Solvent Vapors, 2023.

- Zhengzhou Winsen Electronics Technology Co., Ltd. MQ 138 - Gas Sensor for VOC gas, 2023.

- Aosong Electronics Co., Ltd. DHT 22 - Digital-output relative humidity & temperature sensor/module, 2023.

- numpy.absolute - SciPy v1.11.2 Manual.

- numpy.max - SciPy v1.11.2 Manual.

- numpy.min - SciPy v1.11.2 Manual.

- numpy.mean - SciPy v1.11.2 Manual.

- numpy.std - SciPy v1.11.2 Manual.

- numpy.gradient - SciPy v1.11.2 Manual.

- Integration (scipy.integrate) - SciPy v1.11.2 Manual.

- Hierlemann, A.; Gutierrez-Osuna, R. Higher-order chemical sensing. Chemical reviews 2008, 108, 563–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourier Transforms (scipy.fft) - SciPy v1.11.2.

- Discrete Fourier Transform (numpy.fft) - NumPy v1.25 Manual.

- Wasilewski, F. Wavelet transforms in python, 2023.

- scipy.signal.find_peaks - SciPy v1.11.2 Manual.

- scipy.stats.skew - SciPy v1.11.2 Manual.

- scipy.stats.kurtosis - SciPy v1.11.2 Manual.

- scipy.stats.entropy - SciPy v1.11.2 Manual.

- statsmodels.tsa.ar_model.AutoReg - statsmodels 0.15.0 (+49) Stable release Manual.

- librosa.stft - librosa 0.10.1 documentation.

- Friedman, J.H. Stochastic gradient boosting. Computational statistics & data analysis 2002, 38, 367–378. [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed, B.S.; Arya, M.S.; Sangeetha, S.; Auxilia Osvin, N.V.; others. Diabetes Mellitus Disease Prediction and Type Classification Involving Predictive Modeling Using Machine Learning Techniques and Classifiers. Applied Computational Intelligence and Soft Computing 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaff, A.; Gupta, H. Extra-tree classifier with metaheuristics approach for email classification. Advances in Computer Communication and Computational Sciences: Proceedings of IC4S 2018. Springer, 2019, pp. 189–197.

- Gupta, D.; Choudhury, A.; Gupta, U.; Singh, P.; Prasad, M. Computational approach to clinical diagnosis of diabetes disease: a comparative study. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhai, M.; Ren, Z.; Ren, H.; Li, M.; Quan, D.; Chen, L.; Qiu, L. Exploratory study on classification of diabetes mellitus through a combined Random Forest Classifier. BMC medical informatics and decision making 2021, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, N.; Babu, B.V.; Rao, N.S. Survey on clinical prediction models for diabetes prediction. Journal of Big Data 2017, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujumdar, A.; Vaidehi, V. Diabetes prediction using machine learning algorithms. Procedia Computer Science 2019, 165, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olisah, C.C.; Smith, L.; Smith, M. Diabetes mellitus prediction and diagnosis from a data preprocessing and machine learning perspective. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2022, 220, 106773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 |

| Sensor Model | Manufacturer | VOCs sensitivity | Sensitivity range (in ppm)1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGS826 | Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan | VOCs, NH_3 | 30-5000 |

| TGS2610 | Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan | H_2, VOCs | 500-10,000 |

| TGS822 | Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan | VOCs, H_2, CO | 50-5000 |

| TGS2602 | Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan | VOCs, NH_3, H_2S | 1-30 |

| TGS2600 | Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan | H2, VOCS, CO | 1-100 |

| TGS2603 | Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan | NH_3, H_2S | 1-10 |

| TGS2620 | Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan | VOCs, H_2 | 50-5000 |

| MQ138 | Figaro Inc., Osaka, Japan | VOCs | 5 - 500 |

| DHT22 | Aosong Electronics Co., Ltd. | Humidity (H) and | H: 0 - 100 RH, |

| Temperature (T) | T: -40 - 80 Celsius |

| Base Feature | Feature used | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CurveMagnitude | abs(CurveMagnitude) [27] | The absolute value of curve magnitude values. |

| max(CurveMagnitude) [28] | The maximum of curve magnitude values. | |

| min(CurveMagnitude) [29] | The minimum of curve magnitude values. | |

| mean(CurveMagnitude) [30] | The mean or average of curve magnitude values. | |

| stdDev(CurveMagnitude) [31] | The median curve magnitude values. | |

| FirstDerivative [32] | max(FirstDerivative) | The maximum of first derivative of signal values. |

| min(FirstDerivative) | The minimum of first derivative of signal values. | |

| mean(FirstDerivative) | The mean of first derivative of signal values. | |

| abs(FirstDerivative) | The absolute value of the first derivative. | |

| stdDev(FirstDerivative) | The square root of the variance of the first derivative. | |

| SecondDerivative [32] | max(SecondDerivative) | The maximum of second derivative of signal values. |

| min(SecondDerivative) | The minimum of second derivative of signal values. | |

| mean(SecondDerivative) | The mean of second derivative of signal values. | |

| abs(SecondDerivative) | The absolute value of the second derivative. | |

| stdDev(SecondDerivative) | The square root of the variance of the second derivative. | |

| Slope and Integral | ||

| of five intervals [33] | Slope of five intervals | The slope of the five intervals of the curve1. |

| Integral of five intervals | The integral of the five intervals of the curve1. | |

| Phase |  |

It represents the integral of derivative over the magnitude values [34]. |

| Fast Fourier | phase | The phase is calculated based on the fft of the sensors’ reponse. |

| Transform | powerSpectrum | The square of the absolute value of fft transform. |

| (fft) [35,36] | spectralEntropy | It represents the entropy of power spectrum. |

| Wavelet [37] | waveletCoeffs | Coefficients of wavelet transformation of the sensor’s response signal. |

| Peak [38] | height | The height of the peak. |

| width | The width of the peak. | |

| area | The trapezoidal area of the peak. | |

| Shape | skewness [39] | The measure of the asymmetry of a distribution, where a positive skew indicates a longer tail on the right side and a negative skew indicates a longer tail on the left side. |

| kurtosis [40] | The measure of the tailedness of a distribution; a positive value indicates fatter tails and a negative value indicates thinner tails. | |

| entropy [41] | The measure of the disorder or randomness of a shape; a higher entropy indicates a more disordered or random shape. | |

| Auto-Regressive (AR) [42] | coefficients | These represent the relationships between past and current values of the model. |

| predictionError | The difference between the actual observed value and the ar-model’s predicted value. | |

| Short-time Fourier transform (STFT) [43] |

dominantFrequency | The frequency component that has the highest magnitude of the signal. |

| avg(magnitude(STFTcoeffs)) | The average magnitude of the STFT coefficients, calculated by taking the mean of the magnitudes over all the time frames. | |

| Sum(magnitude(STFTcoeffs)) | The sum of the magnitudes of all the STFT coefficients. | |

| energy(STFT) | The overall power of the signal in the frequency domain. | |

| centroid(STFTcoeffs) | The weighted average of the frequencies in the STFT, where the weights are the magnitudes of the STFT coefficients. | |

| bandwidth(STFT) | The range of frequencies represented by a single STFT coefficient, determined by the window length. | |

| rolloff(STFT) | The frequency at which the magnitude of the STFT coefficients drops to -3dB, typically used as a measure of the sharpness of the transition between the passband and the stopband. |

| ML Classifiers | Parameter name | Parameter values |

|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree | criterion | (`gini’, `entropy’, `log_loss’) |

| splitter | (`best’, `random’) | |

| max depth | (2 to 10, step size of 1) | |

| min samples split | (2 to 10, step size of 1) | |

| Support Vector | C | (0.1 to 10, step size of 0.1) |

| kernel | (`linear’, `poly’, `rbf’, `sigmoid’, `precomputed’) | |

| degree | (3 to 10, step size of 1) | |

| gamma | (`scale’, `auto’, , `float’) with (0.001 to 1, step size of 0.005) for `float’ | |

| GradientBoost | learning rate | (0.01 to 10, step size of 0.01) |

| n estimators | (5 to 500, step size of 5) | |

| subsample | (0.01 to 1, step size of 0.01) | |

| criterion | (`friedman mse’, `squared error’) | |

| min samples split | (2 to 10, step size of 1) | |

| max depth | (2 to 10, step size of 1) | |

| RandomForest | n estimators | (5 to 500, step size of 5) |

| criterion | (`gini’, `entropy’, `log loss’) | |

| min samples split | (2 to 10, step size of 1) | |

| max depth | (2 to 10, step size of 1) | |

| max features | (`sqrt’, `log2’) | |

| min samples leaf | (1 to 10, step size of 1) | |

| KNeighbors | n neighbors | (5 to 100, step size of 5) |

| weights | (`uniform’, `distance’) | |

| algorithm | (`auto’, `ball tree’, `kd tree’, `brute’) | |

| leaf size | (30 to 100, step size of 3) | |

| ElasticNet | alpha | (0.01 to 1, step size of 0.01) |

| l1 ratio | (0.01 to 1, step size of 0.01) | |

| fit intercept | (True, False) | |

| max iter | (1000 to 5000, step size of 100) | |

| selection | (`cyclic’, `random’) | |

| Ridge | solver | (`auto’, `svd’, `cholesky’, `lsqr’, `sparse_cg’, `sag’) |

| fit intercept | (True, False) | |

| max iter | (1000 to 5000, step size of 100) | |

| Lasso | alpha | (0.1 to 10, step size of 0.1) |

| fit intercept | (True, False) | |

| copy X | (True, False) | |

| max iter | (1000 to 5000, step size of 100) | |

| selection | (`cyclic’, `random’) | |

| LogisticRegression | penalty | (`l1’, `l2’, `elasticnet’, None) |

| dual | (True, False) | |

| C | (0.1 to 10, step size of 0.1) | |

| fit intercept | (True, False) | |

| solver | (`lbfgs’, `liblinear’, `newton-cg’, `newton-cholesky’, `saga’, `sag’) | |

| max iter | (1000 to 5000, step size of 100) | |

| multi class | (`auto’, `ovr’, `multinomial’) | |

| XGBoost | max depth | (1 to 10, step size of 1) |

| alpha | (0.1 to 10, step size of 0.1) | |

| booster | (`gbtree’, `gblinear’) | |

| eta | (0.01 to 1, step size of 0.01) | |

| min child weight | (1 to 10, step size of 1) |

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Age | age of the user. |

| Gender | gender of the user, i.e., male, female, or other. |

| BP | User’s max and min BP values |

| SPO2 | Oxygen level in Blood |

| Heart Rate | Heart Rate of the Patient. |

| Fast Fourier Transform (fft) |

phase powerSpectrum spectralEntropy |

| Phase |  |

| FirstDerivative | max(FirstDerivative) |

| min(FirstDerivative) | |

| mean(FirstDerivative) | |

| abs(FirstDerivative) | |

| stdDev(FirstDerivative) | |

| SecondDerivative | max(SecondDerivative) |

| min(SecondDerivative) | |

| mean(SecondDerivative) | |

| abs(SecondDerivative) | |

| stdDev(SecondDerivative) | |

| Slope and Integral | Slope of five intervals1. |

| of five intervals | Integral of five intervals1. |

| ML Classifiers | Hyper tuned Parameter values |

|---|---|

| DecisionTree | criterion: `entropy’, splitter: `best’, max depth: 5, min samples split: 2 |

| SupportVector | C: 10, kernel: `rbf’, degree: not relevant1, gamma: `auto’ |

| GradientBoost | learning rate: 1, n estimators: 100, subsample: 1, criterion: `friedman mse’, min samples split: 2, max depth: 3 |

| RandomForest | n estimators: 100, criterion: `entropy’, min samples split: 2, max depth: 9, max features: `sqrt’, min samples leaf: 1 |

| KNeighbors | n neighbors: 7, weights: `distance’, algorithm: `auto’, leaf size: 30 |

| ElasticNet | alpha: 0.1, l1 ratio: 0.5, fit intercept: `True’, max iter: 1000, selection: `cyclic’ |

| Ridge | solver: `auto’, fit intercept: `True’, max iter: 1000 |

| Lasso | alpha: 0.1, fit intercept: `True’, copy X: `True’, max iter: 1000, selection: `cyclic’ |

| LogisticRegression | penalty: `l2’, dual: `False’, C: 10, fit intercept: `True’, solver: `lbfgs’, max iter: 1000, multi class: `ovr’ |

| XGBoost | max depth: 5, alpha: 0.1, booster: `gbtree’, eta: 0.3, min child weight: 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).