Submitted:

23 August 2023

Posted:

24 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

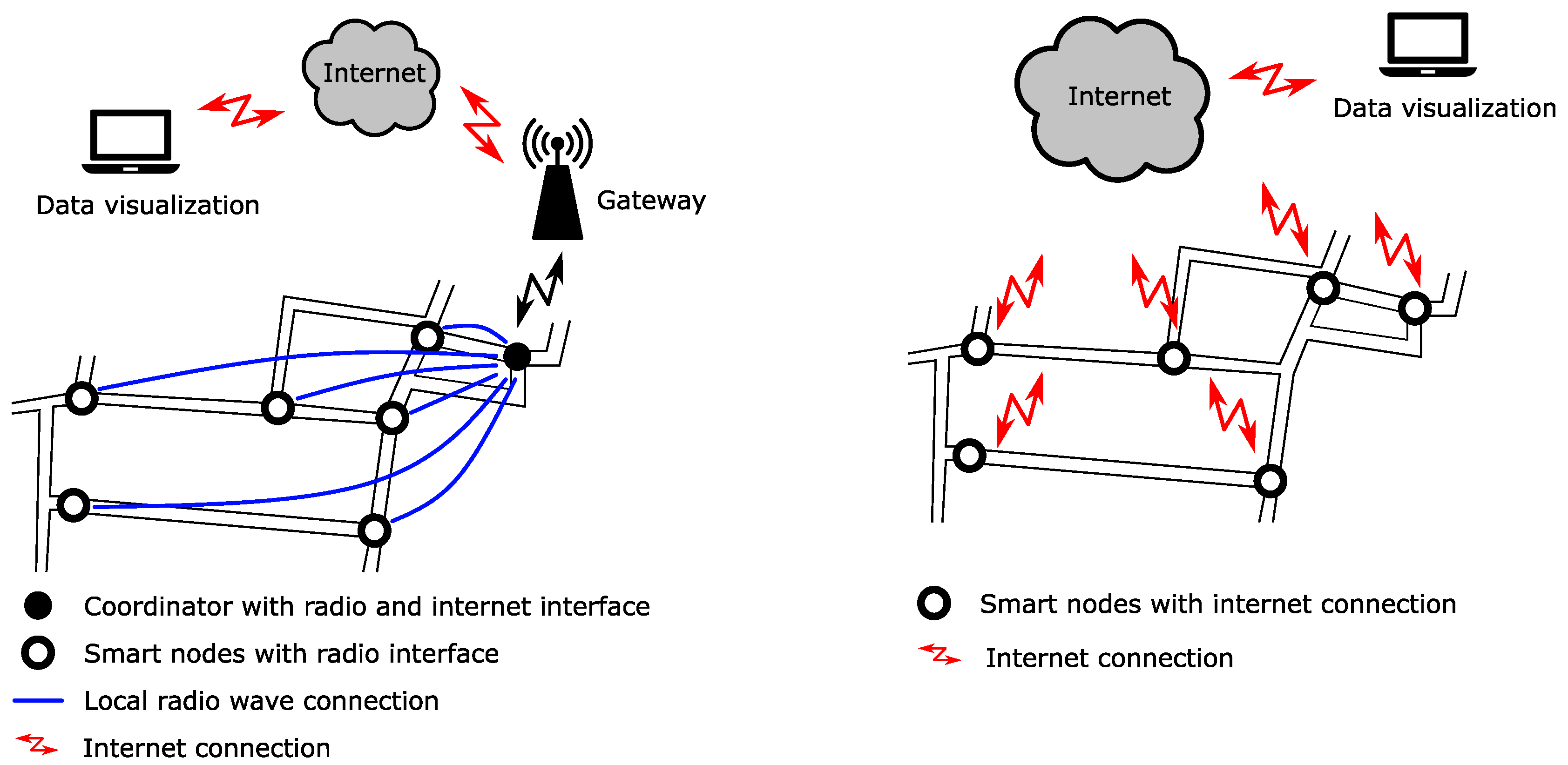

2. Review of SWG Based on Standard Radio Communication

2.1. Water Quality Assessment

2.2. Monitoring and Optimization of Pipeline Network

2.3. Hydraulic and Water Quality Monitoring

2.4. Wireless Communication Parameters

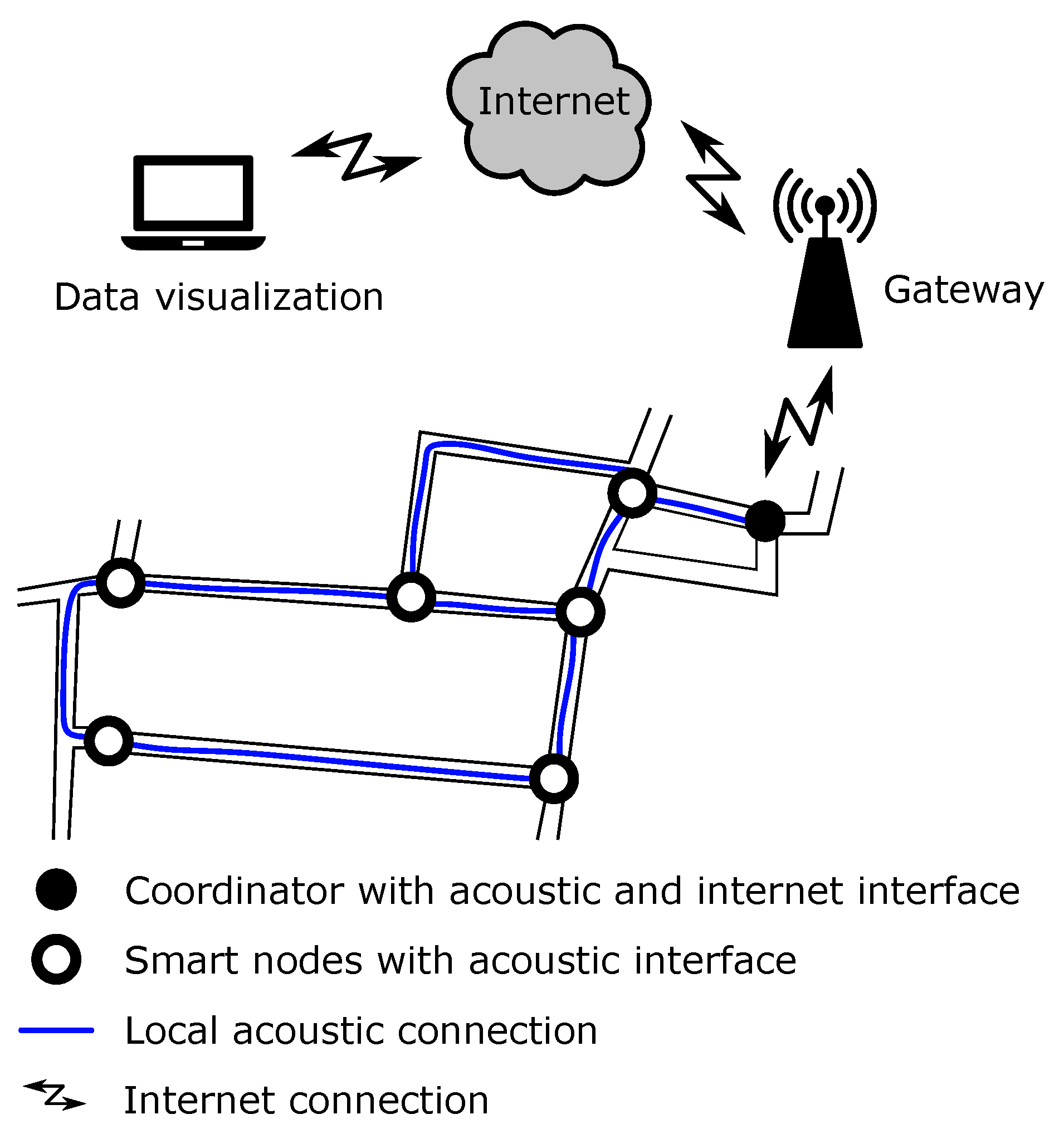

3. Acoustic Based Communication

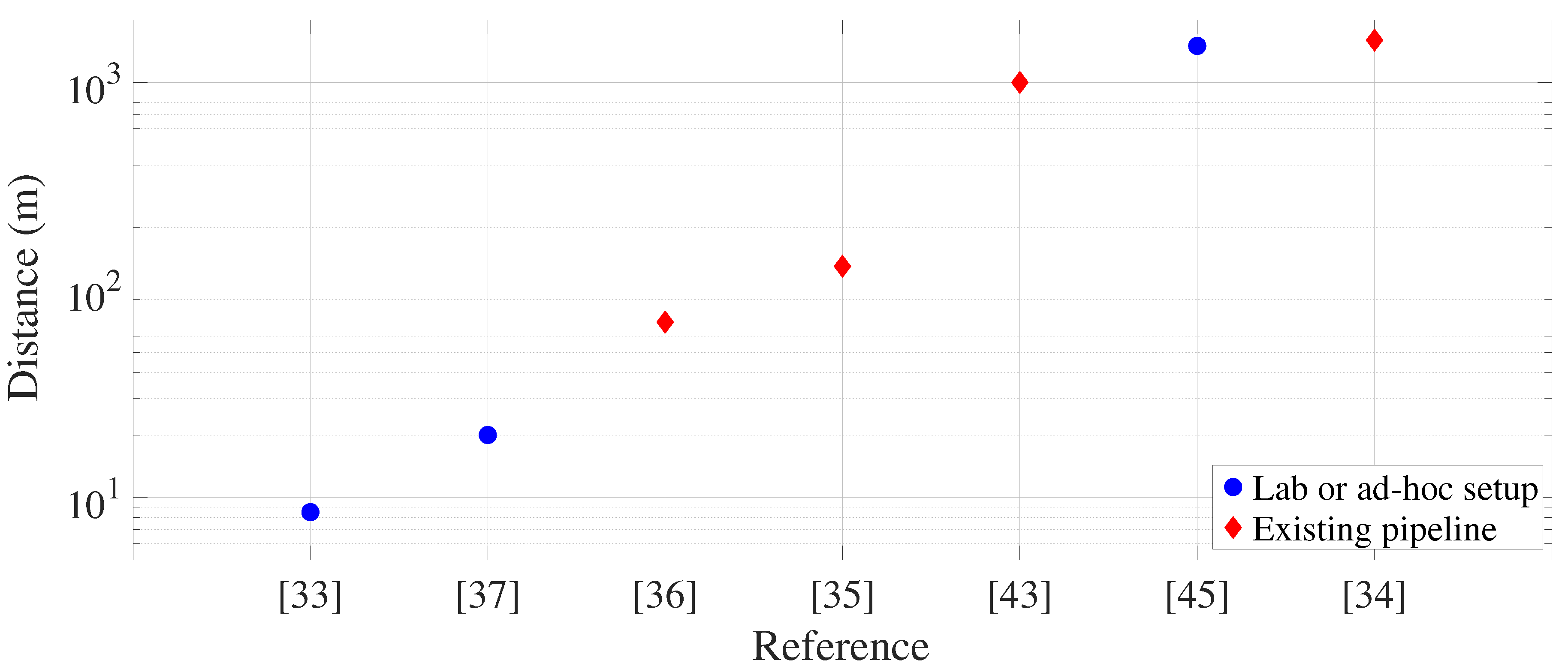

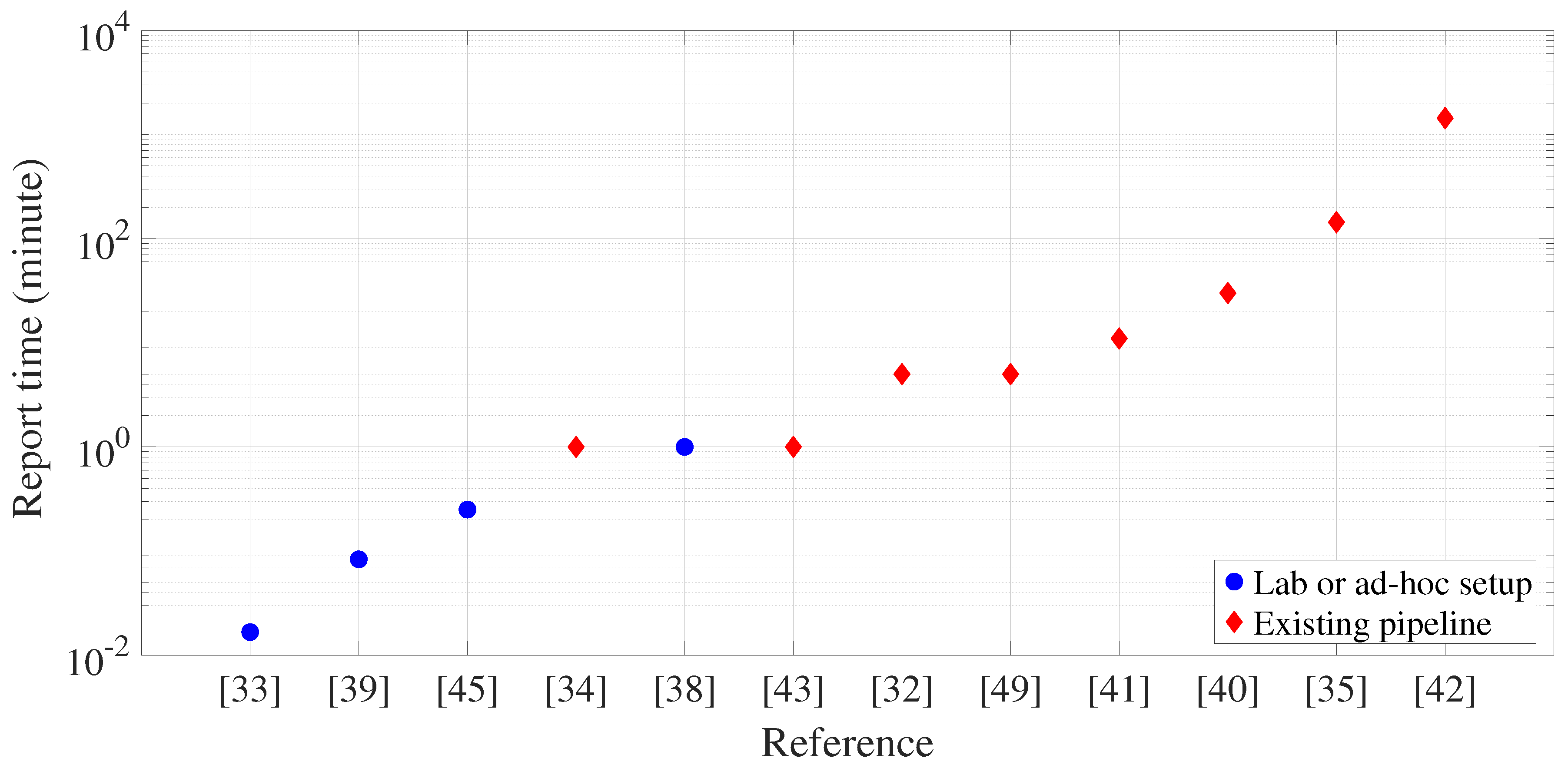

3.1. Existing Works Based on Guided Acoustic Communication

3.2. Joseph et al. [13]

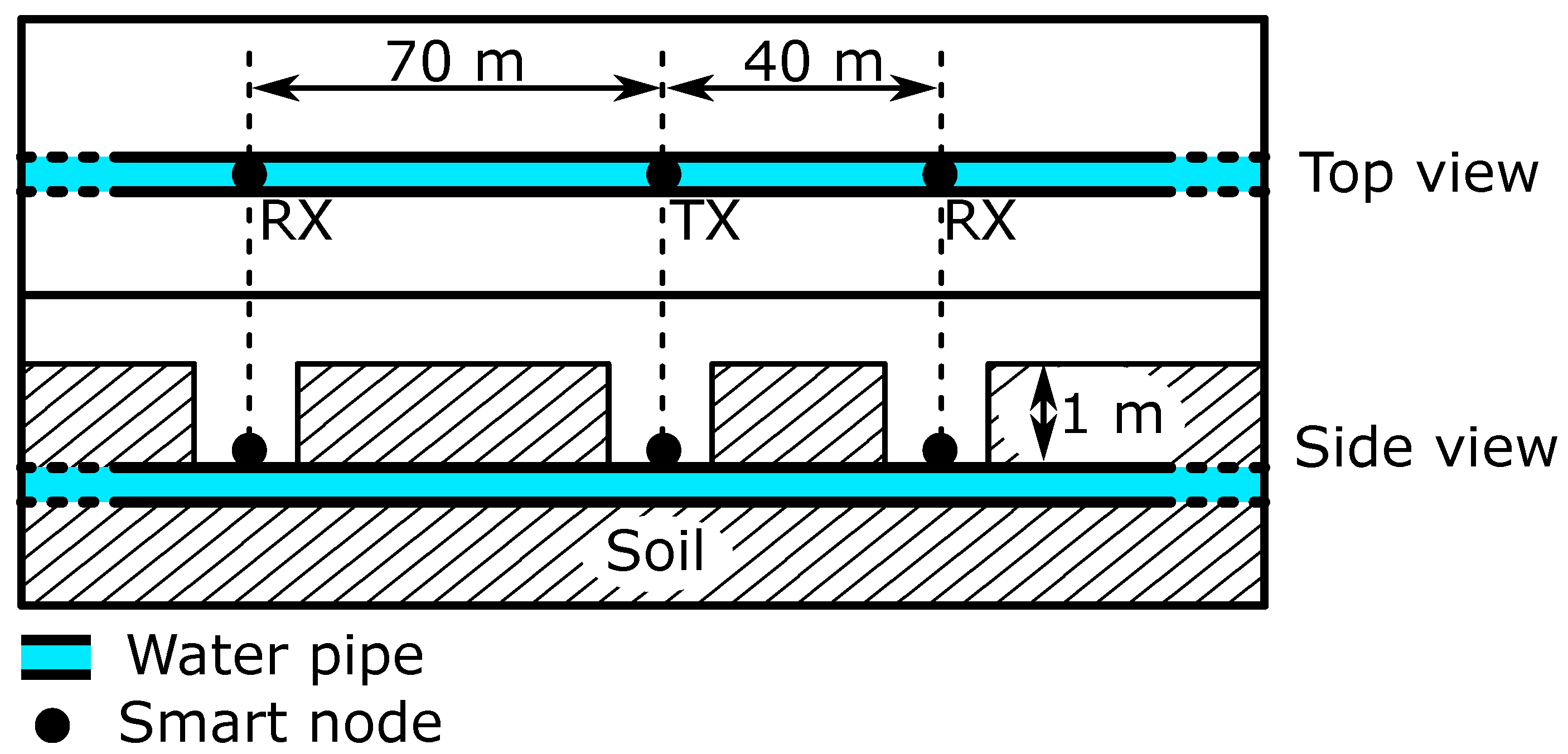

3.3. Fishta et al. [21]

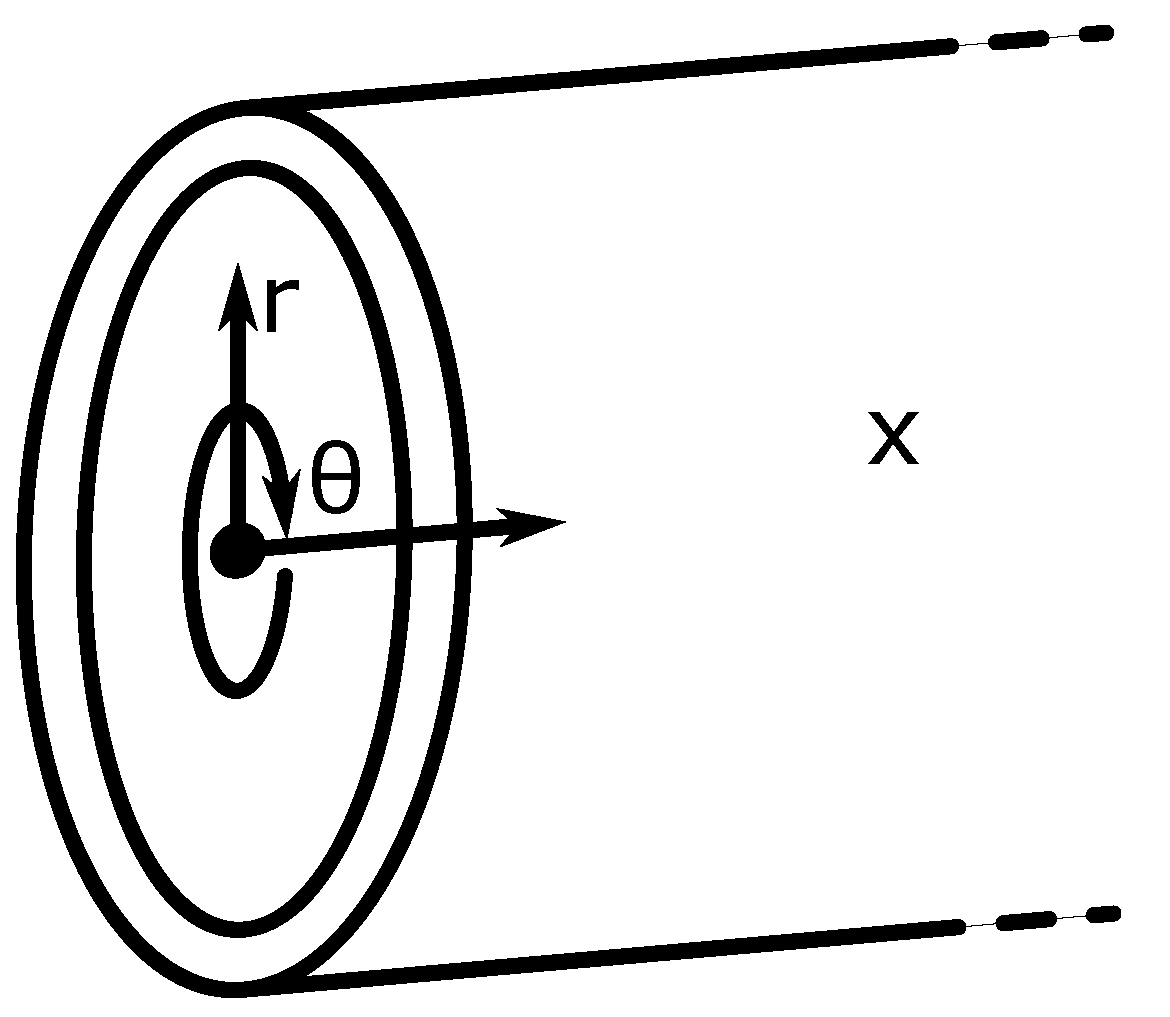

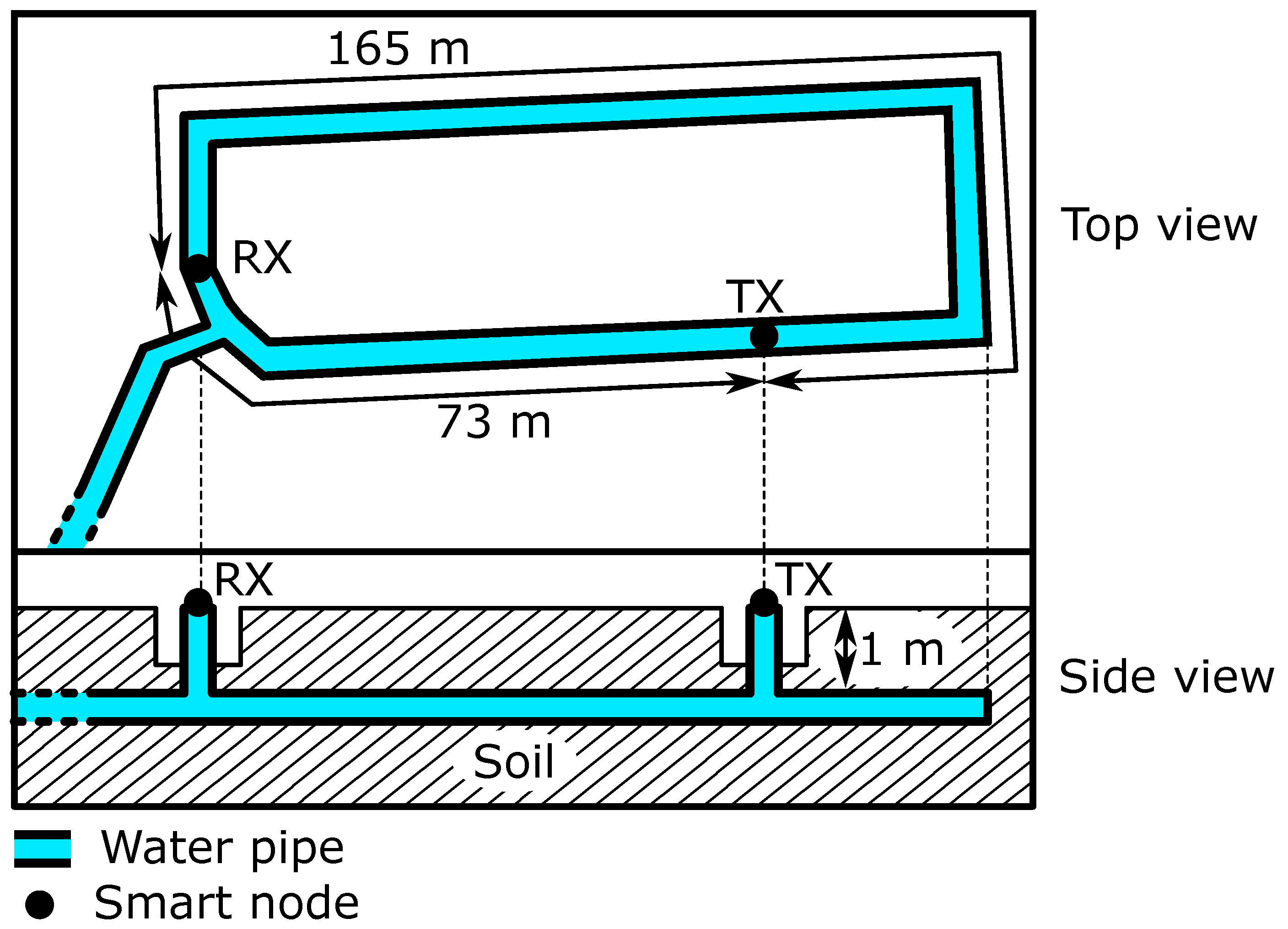

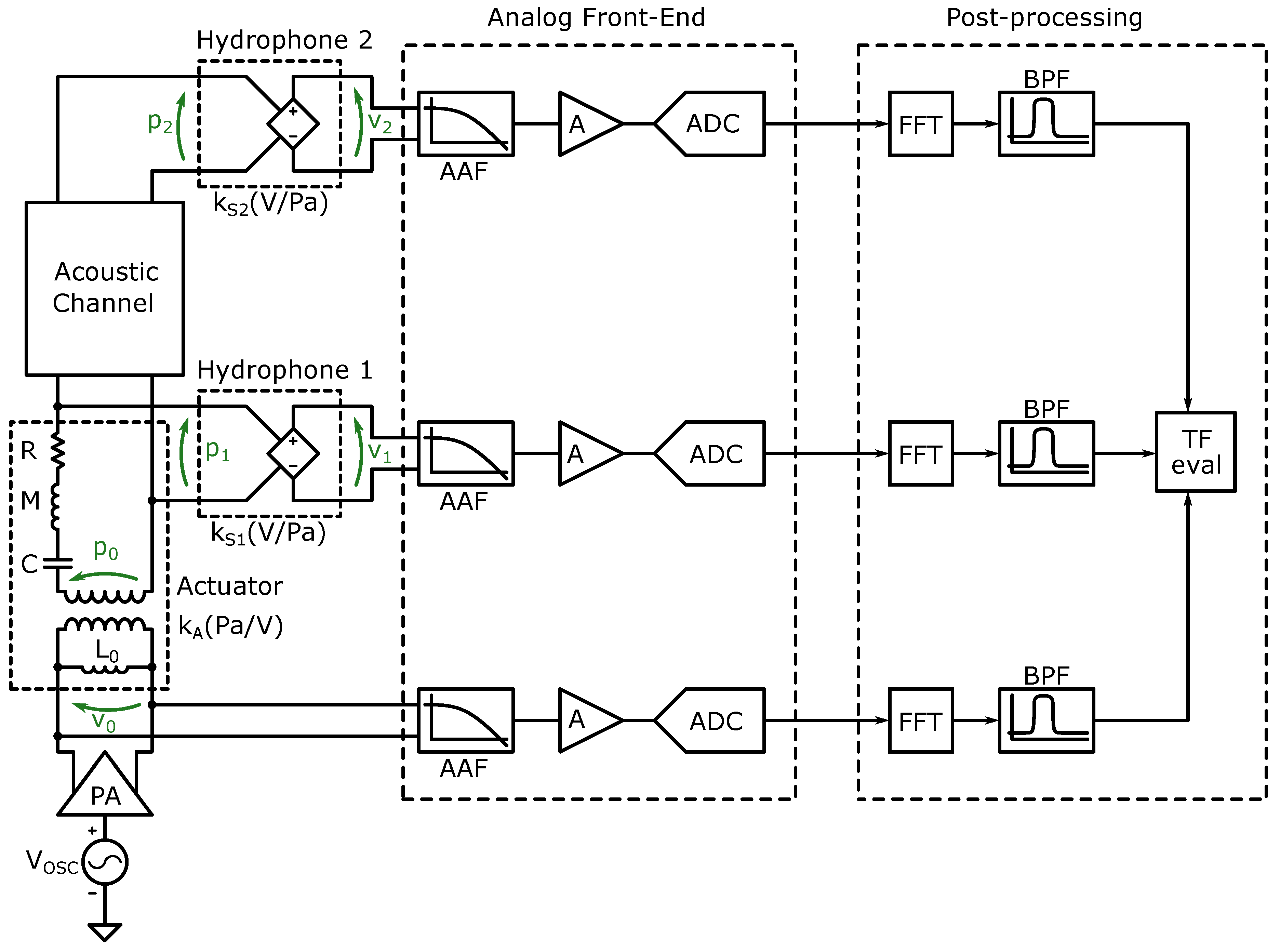

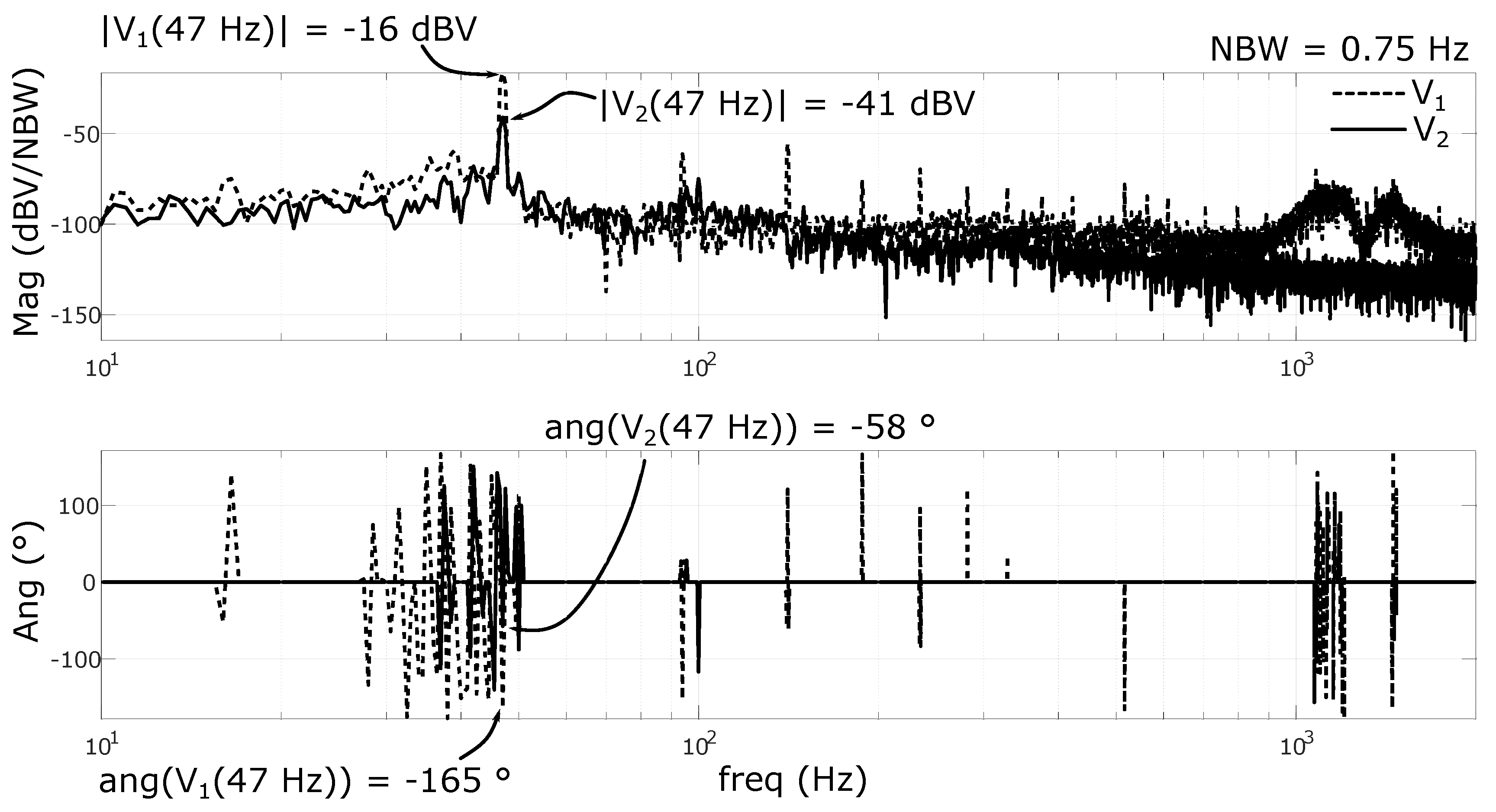

4. Characterization and Design of Acoustic Communication Systems

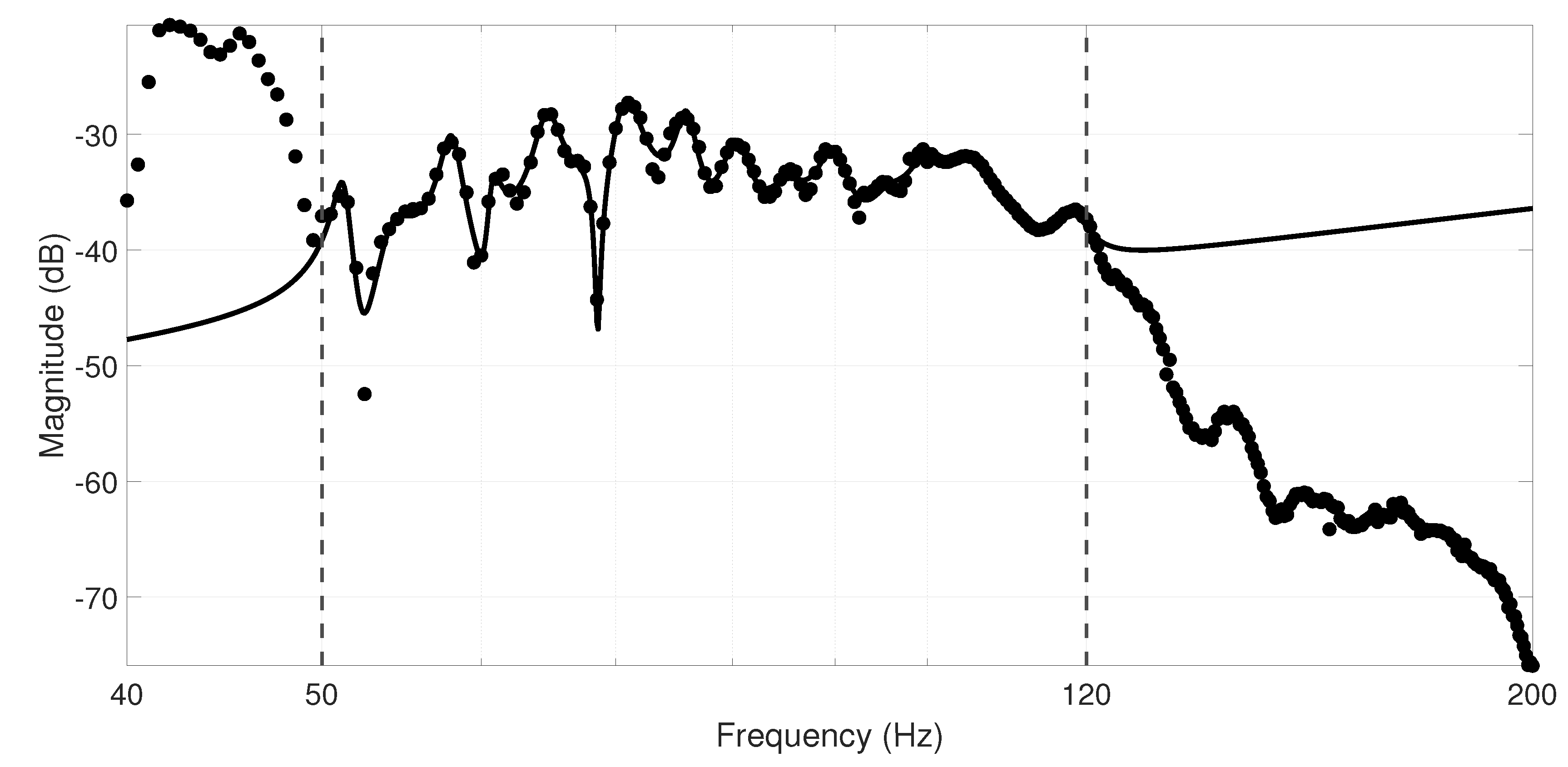

4.1. Channel Characterization

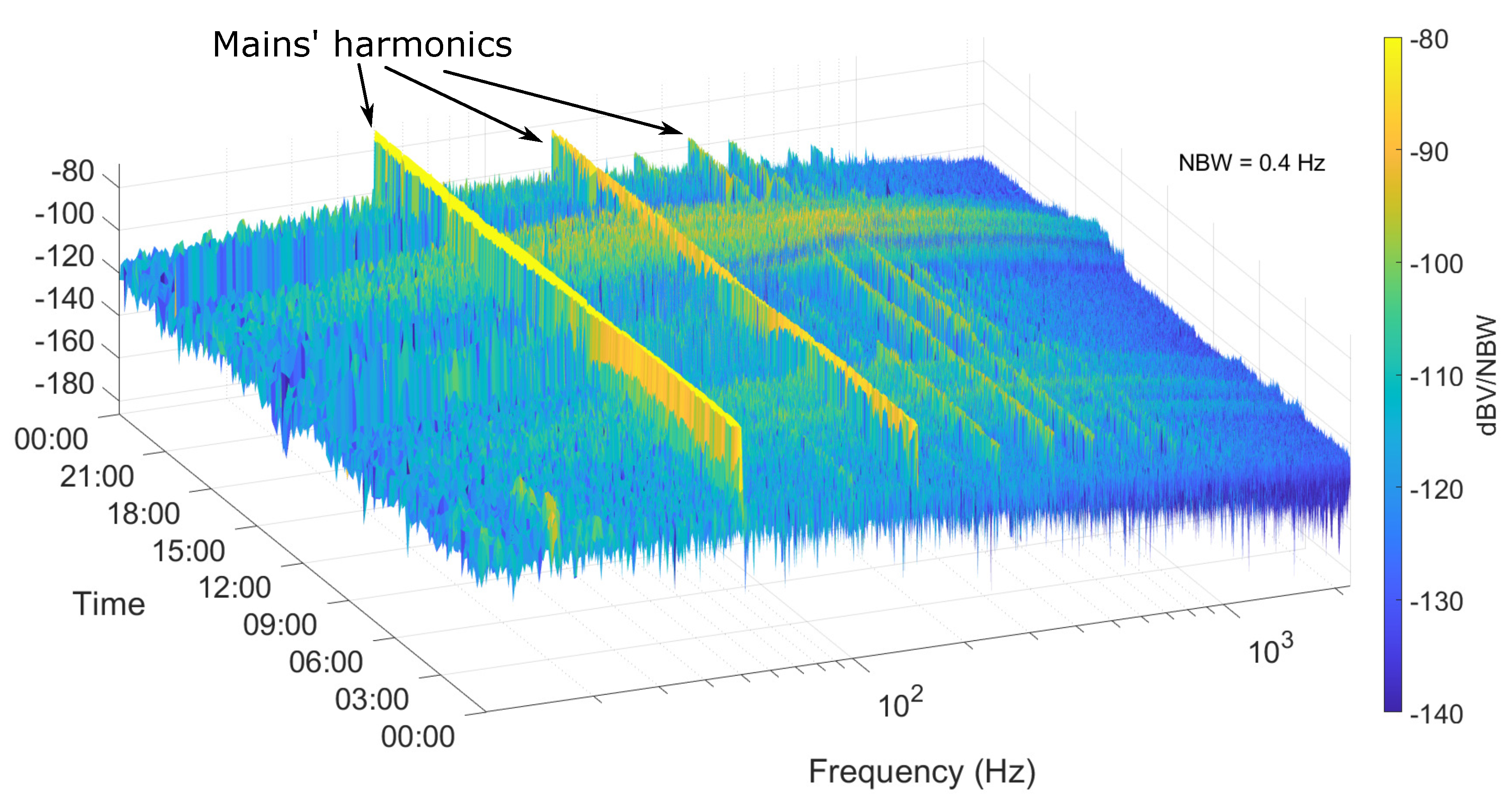

4.2. Noise Characterization

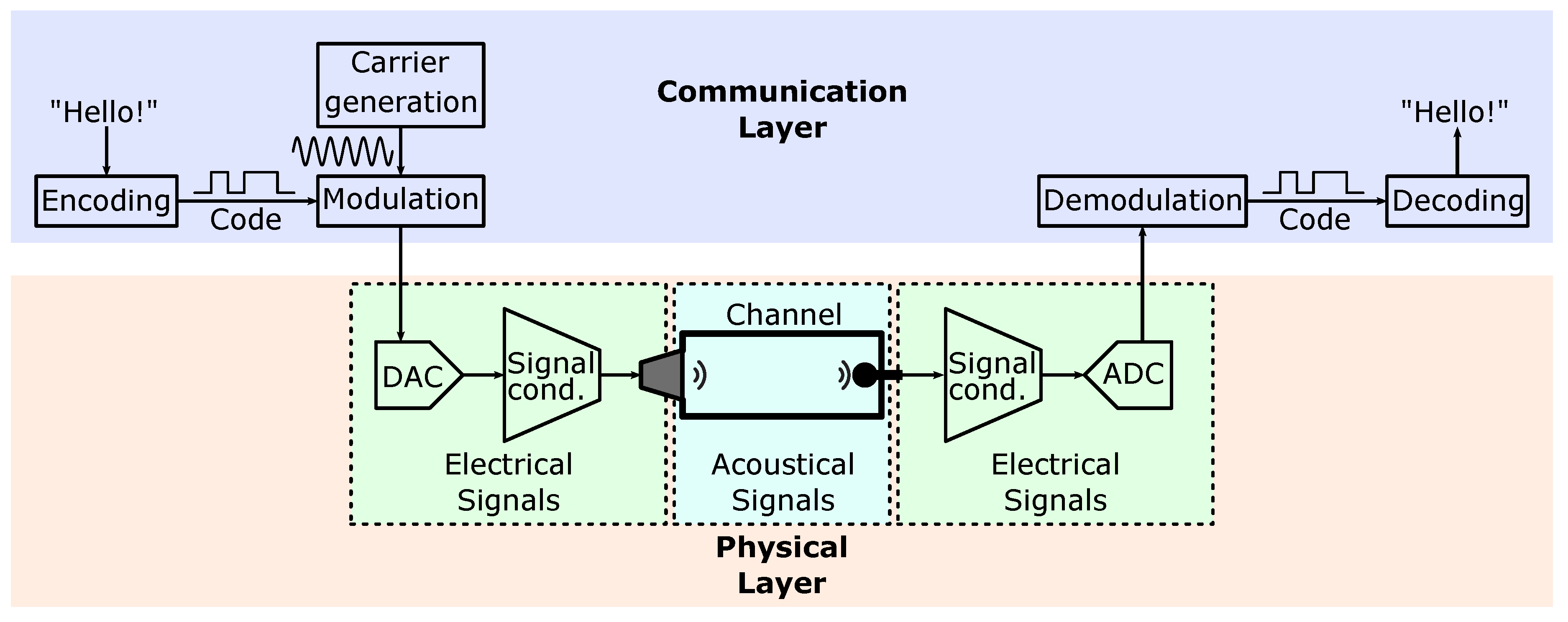

4.3. Communication Layer

5. Conclusions and Future Trends

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lalle, Y.; Fourati, M.; Fourati, L.C.; Barraca, J.P. Communication Technologies for Smart Water Grid Applications: Overview, Opportunities, and Research Directions. Computer Networks 2021, 190, 107940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, S.A.; Maiolo, M.; Brusco, A.C.; Turco, M.; Pirouz, B.; Greco, E.; Spezzano, G.; Piro, P. Smart Technologies for Water Resource Management: An Overview. Sensors 2022, 22, 6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariq, S.; Hu, Z.; Zayed, T. Micro-Electromechanical Systems-Based Technologies for Leak Detection and Localization in Water Supply Networks: A Bibliometric and Systematic Review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 289, 125751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharani Baanu, B.; Jinesh Babu, K.S. Smart Water Grid: A Review and a Suggestion for Water Quality Monitoring. Water Supply 2021, 22, 1434–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, A.M.; Karray, F.; Jmal, M.W.; Abid, M.; Manzoor Qasim, S.; BenSaleh, M.S. Towards Realisation of Wireless Sensor Network-Based Water Pipeline Monitoring Systems: A Comprehensive Review of Techniques and Platforms. IET Science, Measurement & Technology 2016, 10, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Camargo, E.T.; Spanhol, F.A.; Slongo, J.S.; da Silva, M.V.R.; Pazinato, J.; de Lima Lobo, A.V.; Coutinho, F.R.; Pfrimer, F.W.D.; Lindino, C.A.; Oyamada, M.S.; et al. Low-Cost Water Quality Sensors for IoT: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, W.; Hoashi, Y.; Paredes Aguilar, L.L.; Postigo-Malaga, M.; Garcia-Bravo, J.M.; Min, B.C. A Low-Cost and Small USV Platform for Water Quality Monitoring. HardwareX 2019, 6, e00076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaropoulos, K.; Salamone, S.; Sela, L. Frequency-Based Leak Signature Investigation Using Acoustic Sensors in Urban Water Distribution Networks. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2023, 55, 101905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurgiutiu, V. Structural Health Monitoring with Piezoelectric Wafer Active Sensors; Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.; Ye, L. Identification of Damage Using Lamb Waves: From Fundamentals to Applications; Number 48 in Lecture Notes in Applied and Computational Mechanics; Springer: Berlin, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Wang, N.; Ho, M.; Zhu, J.; Song, G. Design of a New Stress Wave Communication Method for Underwater Communication. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2021, 68, 7370–7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Murch, R.D. Channel Characterization of Acoustic Waveguides Consisting of Straight Gas and Water Pipelines. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 6807–6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, K.M.; Watteyne, T.; Kerkez, B. Awa: Using Water Distribution Systems to Transmit Data: Awa: Using to Transmit Data. Transactions on Emerging Telecommunications Technologies 2018, 29, e3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokossalakis, G. Acoustic Data Communication System for In-Pipe Wireless Sensor Networks. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma, H.; Nakamura, K.; Ueha, S. Two-Way Communication over Gas Pipe-Line Using Multicarrier Modulated Sound Waves with Cyclic Frequency Shifting. Acoustical Science and Technology 2006, 27, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantaris, G.S.; Makris, N.A. Underwater Wireless In-Pipe Communications System. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT); 2015; pp. 1945–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, K.M.; Kerkez, B. Enabling Communications for Buried Pipe Networks. In Proceedings of the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2014, Portland, Oregon; 2014; pp. 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farai, O.; Metje, N.; Anthony, C.; Chapman, D. Analysis of Acoustic Signal Propagation for Reliable Digital Communication along Exposed and Buried Water Pipes. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkhami Meybodi, S.; Pardo, P.; Dohler, M. Magneto-Inductive Communication among Pumps in a District Heating System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Antennas, Propagation and EM Theory; 2010; pp. 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jing, L.; Lu, Y.; Stojanovic, M.; Murch, R. Performance of Coherent OFDM and Differentially Coherent OFDM Communication Systems in Water Pipeline Channels. In Proceedings of the Global Oceans 2020: Singapore – U.S. Gulf Coast; 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishta, M.; Raviola, E.; Fiori, F. A Wireless Communication System for Urban Water Supply Networks Based on Guided Acoustic Waves. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 108955–108964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heifetz, A.; Shribak, D.; Huang, X.; Wang, B.; Saniie, J.; Young, J.; Bakhtiari, S.; Vilim, R.B. Transmission of Images With Ultrasonic Elastic Shear Waves on a Metallic Pipe Using Amplitude Shift Keying Protocol. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 2020, 67, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.; Saulnier, G.J.; Wilt, K.W.; Curt, E.; Scarton, H.A.; Litman, R.B. Low-Power, Low-Rate Ultrasonic Communications System Transmitting Axially along a Cylindrical Pipe Using Transverse Waves. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 2015, 62, 1788–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.S.; Han, W.K.; Guan, Y.L.; Lee, Y.H.; Sun, S. Optimization of Acoustic Communication for Industrial Drilling. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Conference on Information Communication Technologies; 2013; pp. 1060–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, W. A Robust Underwater Acoustic Communication Approach for Pipeline Transmission. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Communications and Computing (ICSPCC); 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Qi, C.; Huang, C.; Chen, J.; Song, A.; Song, G.; Pan, M. Riding Stress Wave: Underwater Communications Through Pipeline Networks. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 2021, 46, 1450–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhang, G.; Song, G. Design of a Networking Stress Wave Communication Method along Pipelines. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2022, 164, 108192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuptuk, N.; Hazell, P.; Watson, J.; Hailes, S. A Systematic Review of the State of Cyber-Security in Water Systems. Water 2021, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, A.; Boccelli, D.L.; Herrera, M.; Creaco, E.; Cominola, A.; Sitzenfrei, R.; Taormina, R. Smart Urban Water Networks: Solutions, Trends and Challenges. Water 2021, 13, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousso, B.Z.; Lambert, M.; Gong, J. Smart Water Networks: A Systematic Review of Applications Using High-Frequency Pressure and Acoustic Sensors in Real Water Distribution Systems. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 410, 137193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoa Bui, X.S.; Marlim, M.; Kang, D. Water Network Partitioning into District Metered Areas: A State-Of-The-Art Review. Water 2020, 12, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.T.T.; Chen, W.J.; Li, K.H.; Huang, P.; Chu, H.H. TriopusNet: Automating Wireless Sensor Network Deployment and Replacement in Pipeline Monitoring. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks; New York, NY, USA, 2012. IPSN’12. pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Preis, A.; Iqbal, M.; Whittle, A.J. Water Distribution System Monitoring and Decision Support Using a Wireless Sensor Network. In Proceedings of the 2013 14th ACIS International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Parallel/Distributed Computing; 2013; pp. 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.J.R.; Manera, L.T.; Campos, M.V. Low-Cost Wireless Sensor Network Applied to Real-Time Monitoring and Control of Water Consumption in Residences. Revista Ambiente & Água 2019, 14, e2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Authors: Chinnusamy, S. IoT Enabled Monitoring and Control of Water Distribution Network: (084). WDSA / CCWI Joint Conference Proceedings 2018, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.; Wang, R.; Ping, J.; Jing, Y.; Sun, J. Water Supply Network Monitoring Based on Demand Reverse Deduction (DRD) Technology. Procedia Engineering 2015, 119, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, S. Wireless Sensor Networks for Water Loss Detection. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cloete, N.A.; Malekian, R.; Nair, L. Design of Smart Sensors for Real-Time Water Quality Monitoring. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 3975–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, H.; Mauricio, D. Smart Water Consumption Measurement System for Houses Using IoT and Cloud Computing. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2020, 192, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrou, T.P.; Anastasiou, C.C.; Panayiotou, C.G.; Polycarpou, M.M. A Low-Cost Sensor Network for Real-Time Monitoring and Contamination Detection in Drinking Water Distribution Systems. IEEE Sensors Journal 2014, 14, 2765–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machell, J.; Mounce, S.R.; Boxall, J.B. Online Modelling of Water Distribution Systems: A UK Case Study. Drinking Water Engineering and Science 2010, 3, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Padillo, J.; Puig, F.; García Morillo, J.; Montesinos, P. IoT Platform for Failure Management in Water Transmission Systems. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 199, 116974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, M.; Gong, J.; Zhang, C.; Marchi, A.; Dix, L.; Lambert, M.F. Leak-Before-Break Main Failure Prevention for Water Distribution Pipes Using Acoustic Smart Water Technologies: Case Study in Adelaide. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 2020, 146, 05020020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Kumar, A.; Rathod, N.; Jain, P.; Mallikarjun, S.; Subramanian, R.; Amrutur, B.; Kumar, M.S.M.; Sundaresan, R. Towards an IoT Based Water Management System for a Campus. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE First International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2); 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Jain, P. Real-Time Water Quality Monitoring System Using Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Computer, Communications and Electronics (Comptelix); 2017; pp. 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Simitha, K.M.; Raj, S. IoT and WSN Based Water Quality Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA); 2019; pp. 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, S.K.; Shenbagalakshmi, G.; Revathi, T. Design of Smart Sensors for Real Time Drinking Water Quality Monitoring and Contamination Detection in Water Distributed Mains. International Journal of Engineering & Technology 2018, 7, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, K.; Anusuya, E.; Kumar, R.; Son, L.H. Real-Time Water Quality Monitoring Using Internet of Things in SCADA. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2018, 190, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, A.; N, S.M.; S, A.; Natarajan, K.; Shobha, K.R.; Paventhan, A. An IoT Based 6LoWPAN Enabled Experiment for Water Management. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Networks and Telecommuncations Systems (ANTS); 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoianov, I.; Nachman, L.; Madden, S.; Tokmouline, T.; Csail, M. PIPENET: A Wireless Sensor Network for Pipeline Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2007 6th International Symposium on Information Processing in Sensor Networks; 2007; pp. 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitre, M.; Shahabudeen, S.; Stojanovic, M. Underwater Acoustic Communications and Networking: Recent Advances and Future Challenges. Marine Technology Society Journal 2008, 42, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Pompili, D.; Melodia, T. Underwater Acoustic Sensor Networks: Research Challenges. Ad Hoc Networks 2005, 3, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.; Green, D. Underwater Acoustic Communications and Networks for the US Navy’s Seaweb Program. In Proceedings of the 2008 Second International Conference on Sensor Technologies and Applications (Sensorcomm 2008); 2008; pp. 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, C.; Cazzolato, B. Acoustic Analyses Using Matlab and Ansys, zeroth ed.; CRC Press, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishta, M.; Raviola, E.; Fiori, F.; Calza, F.; Tornaboni, A. Experimental Characterization of In-Pipe Acoustic Communication Channels Through Measurement of Pressure Transfer Functions. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 27th International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA); 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishta, M.; Raviola, E.; Fiori, F. A Baseband Wireless VNA for the Characterization of Multiport Distributed Systems. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCune, E. Practical Digital Wireless Signals, 1. publ ed.; The Cambridge RF and Microwave Engineering Series; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Ref. | Deployed location |

Aim | Water quality sensors |

Hydraulic sensors |

Wireless protocol |

Nro. nodes |

Extension or distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [33] | Singapore | leak detection, water quality monitoring, on-line hydraulic calibration, model-based prediction | pH, conductivity, temperature, ORP | pressure, hydrophone, flow | 3G | 10s | 80 km2 |

| [34] | laboratory | domestic water consumption monitoring | none | flow | Zigbee | 1 | 8.5 km |

| [35] | IIT Madras campus, Chennai, India | Remote water level monitoring and valve attuation | none | water level | LoRa and GSM | 5 | 1.6 km |

| [36] | Portion of UWSS in Shenzen, China | Water demand estimation without flow sensors | none | pressure | Zigbee | 24 | 130 m |

| [37] | Civil Eng. dept., Strovolos, Cyprus | multi-parameter decision system for leak detection and localization | none | pressure, hydrophone, flow | 433 MHz motes | 4 | 70 m |

| [38] | laboratory | real-time water quality monitoring | pH, conductivity, temperature, ORP | flow | Xbee | 1 | 20 m |

| [39] | laboratory | Domestic water consumption monitoring and leak alert | none | flow | WiFi | 1 | n/a |

| [40] | laboratory | Online water quality monitoring | pH, turbidity, conductivity, ORP temperature | flow | Zigbee | 1 | n/a |

| [41] | 160k people city in UK | Hydraulic model to optimize UWSS management | none | pressure, flow | GPRS | n/a | n/a |

| [42] | ten municipalities near Cordova, Spain | Detection and classification of incidents in water supply network | none | pressure | Sigfox | 8 | 600 km2 |

| [43] | Adelaide city center Australia | Leaks detection and localization | none | hydrophone | 3G | 305 | 6.2 km2 |

| [44] | India Institute of Science campus, Bangalore, India | Water distribution management, water level in tanks | none | water level | sub-1 GHz radio | 10 | 1 km |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).