Submitted:

21 August 2023

Posted:

23 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Site Description

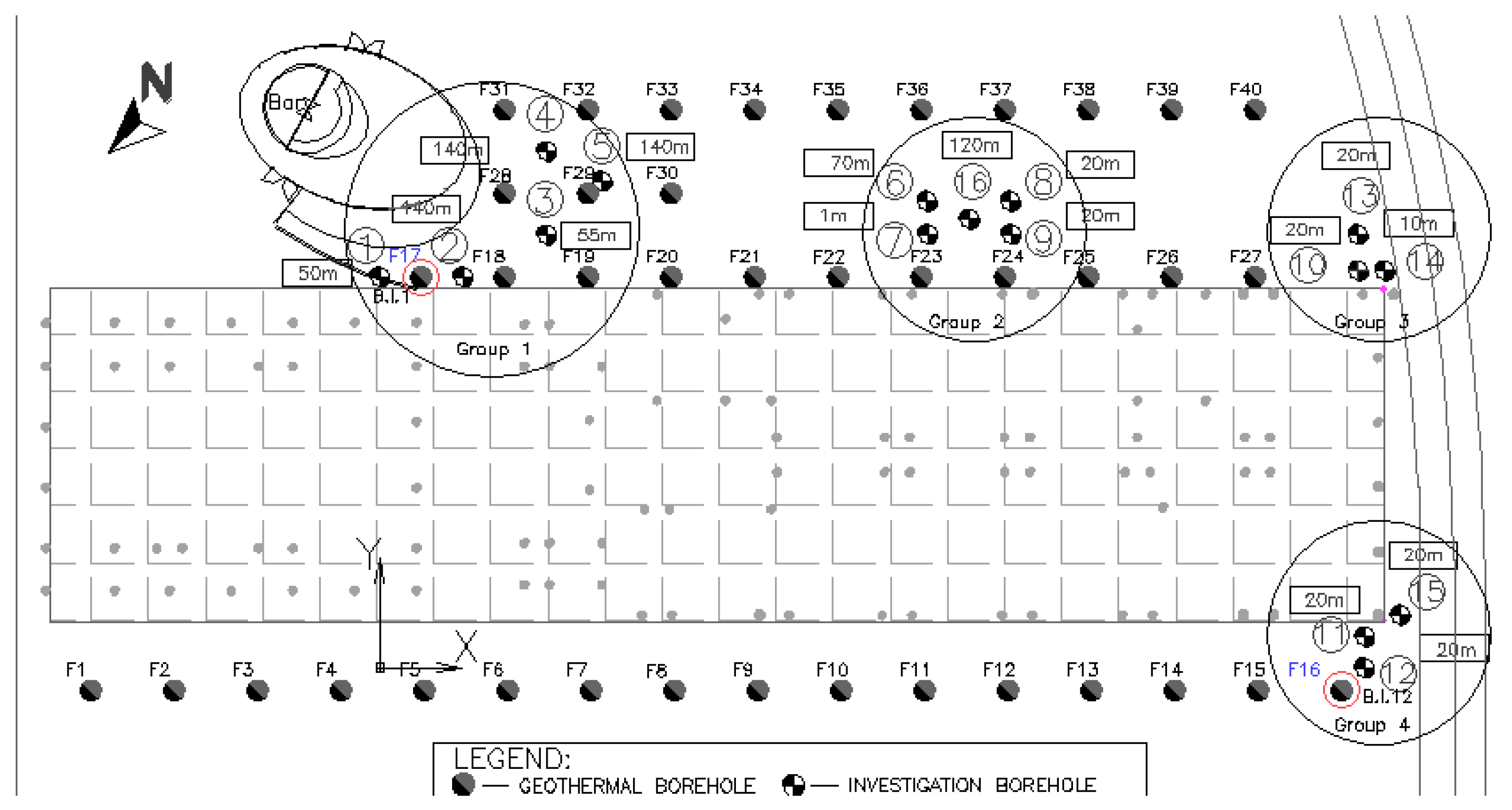

2.1. Geothermal system description

2.2. Site ground main characteristics

- Four boreholes were drilled to a depth of 7 m and intact soil samples were collected. The soils in the first 6 m were classified as soft to medium sandy clay, which stiffer soils found bellow, including silty sand and sandstone.

- Disturbed soil samples were collected from 2 boreholes, F16 and F17, which were drilled to a depth of 132 m. Index properties of the different soil layers (water content, dry unit weight of particles, grain-size distribution, and consistency limits) were obtained [25].

- A superficial layer of fine sandy clay soil up to 6 m depth;

- A layer of silt and clay between 6 m and 78 m depth, including a 6 m-layer of coarse clayey sand between 18 m and 24 m depth;

- A layer of stiff clayey sand (sandstone) up to 140 m depth, including another 6 m-layer of thin clay and sandy clay.

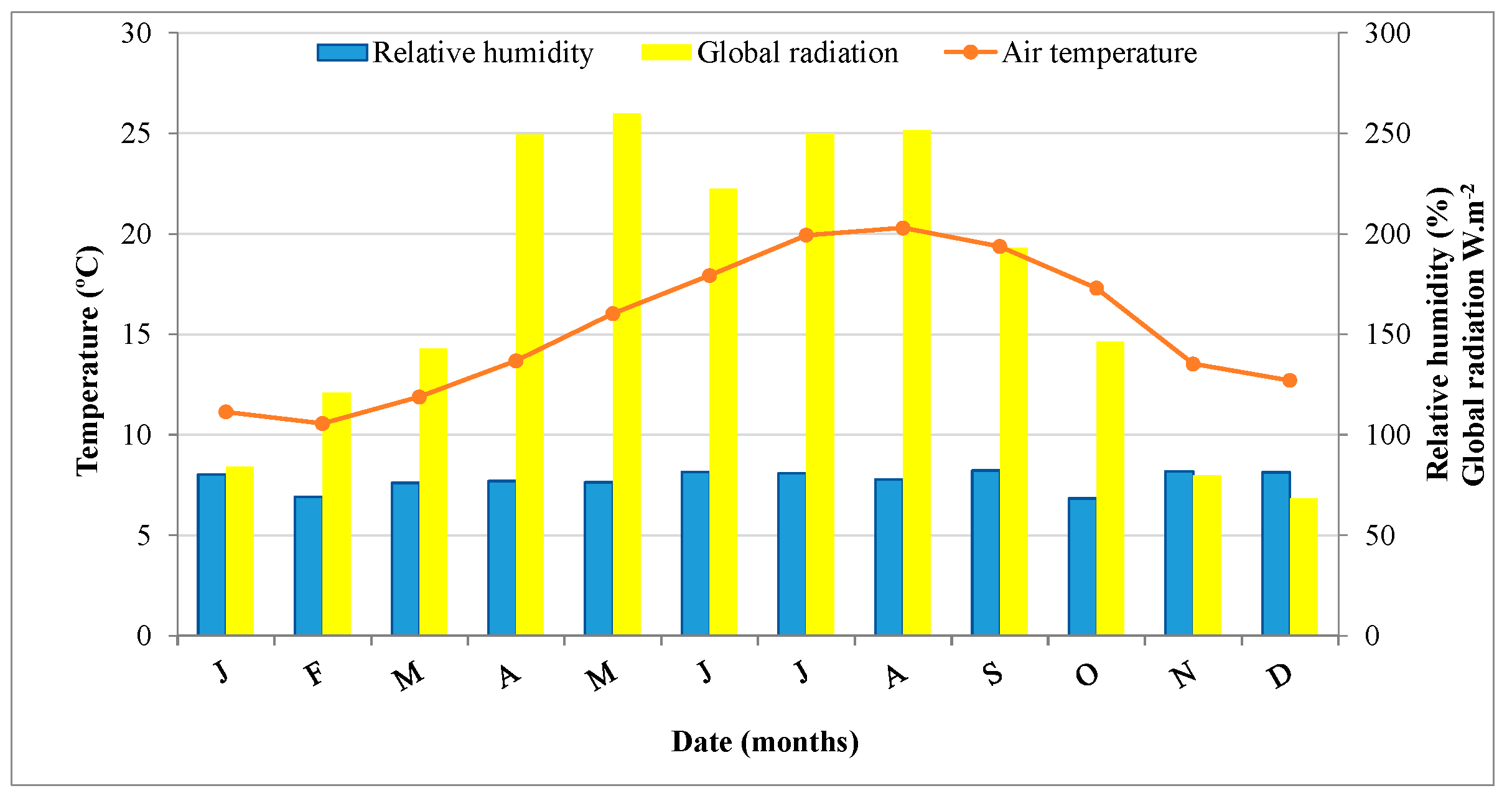

2.3. Site weather conditions

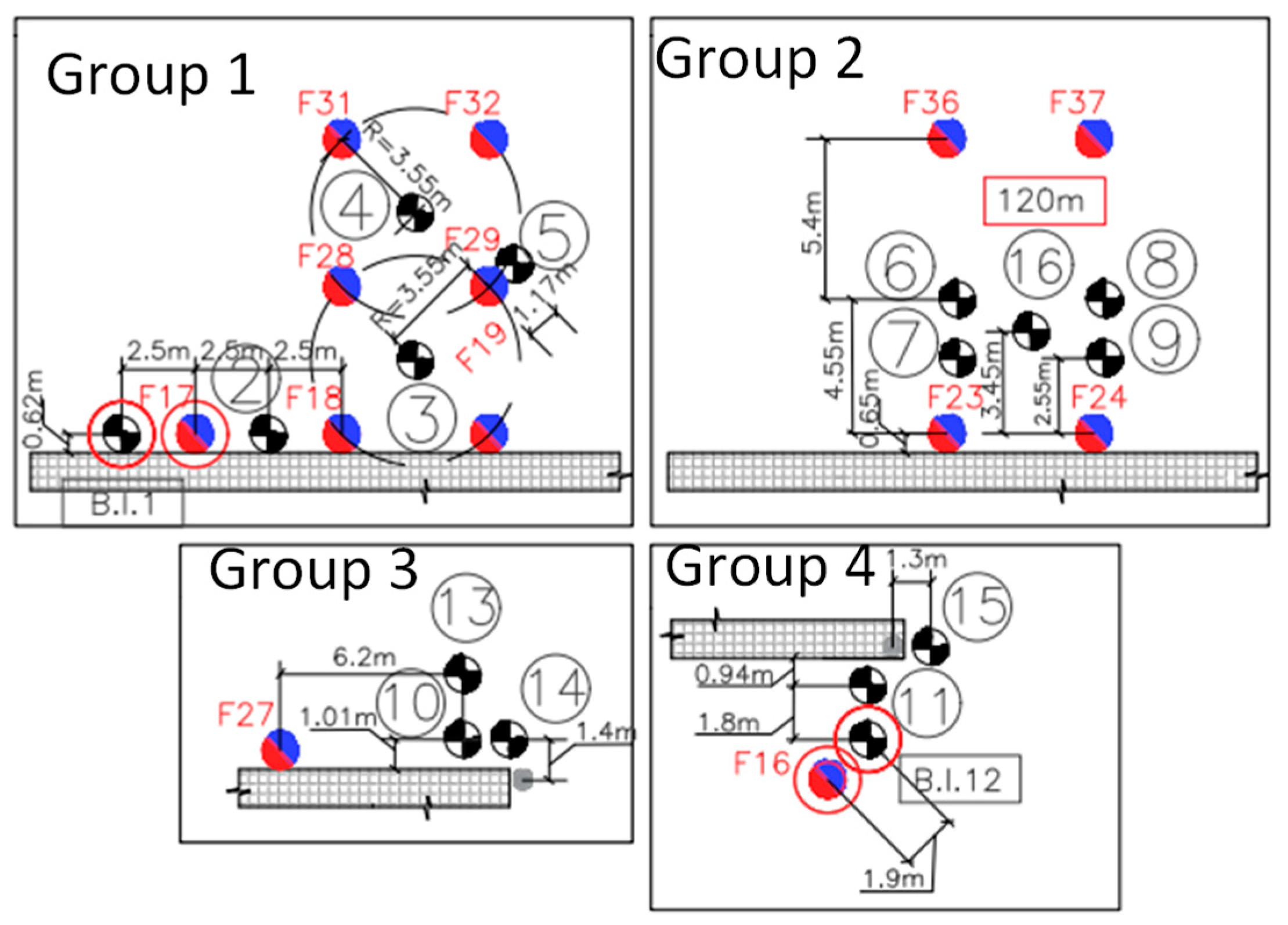

3. Ground temperature-monitoring system

4. Ground temperature data analysis

4.1. Individual annual data temperature analysis

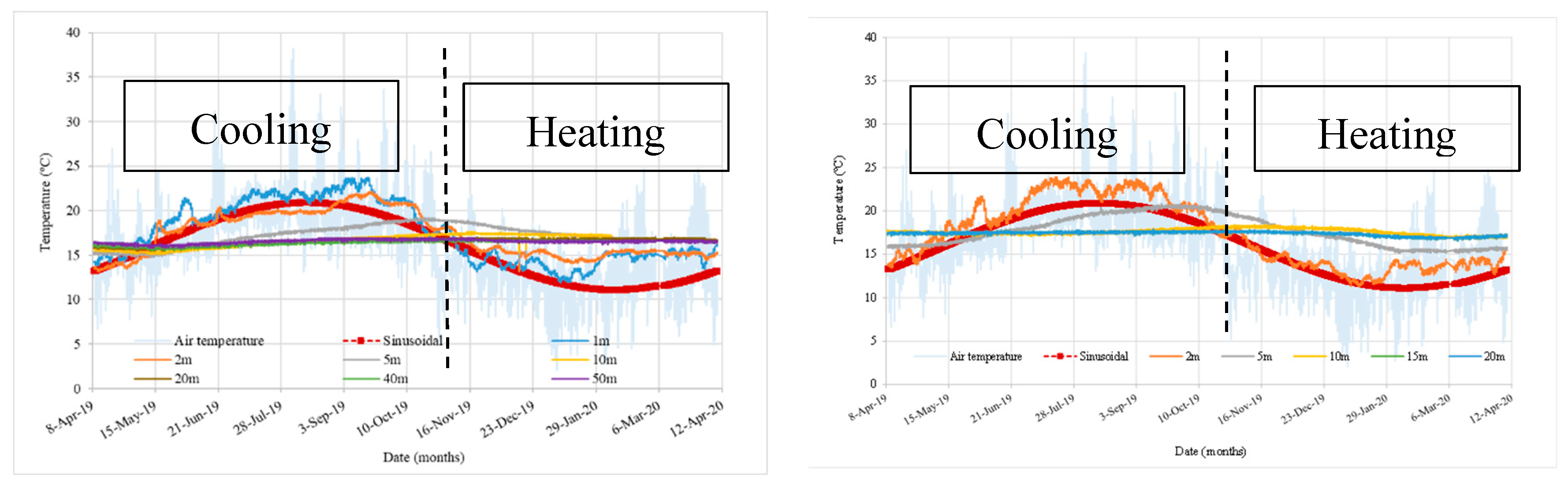

- At 1 and 2 m depths, the ground temperature, during the cooling season, is higher than the atmospheric temperature (which might be a result of the heat injection into the ground by the BHEs system);

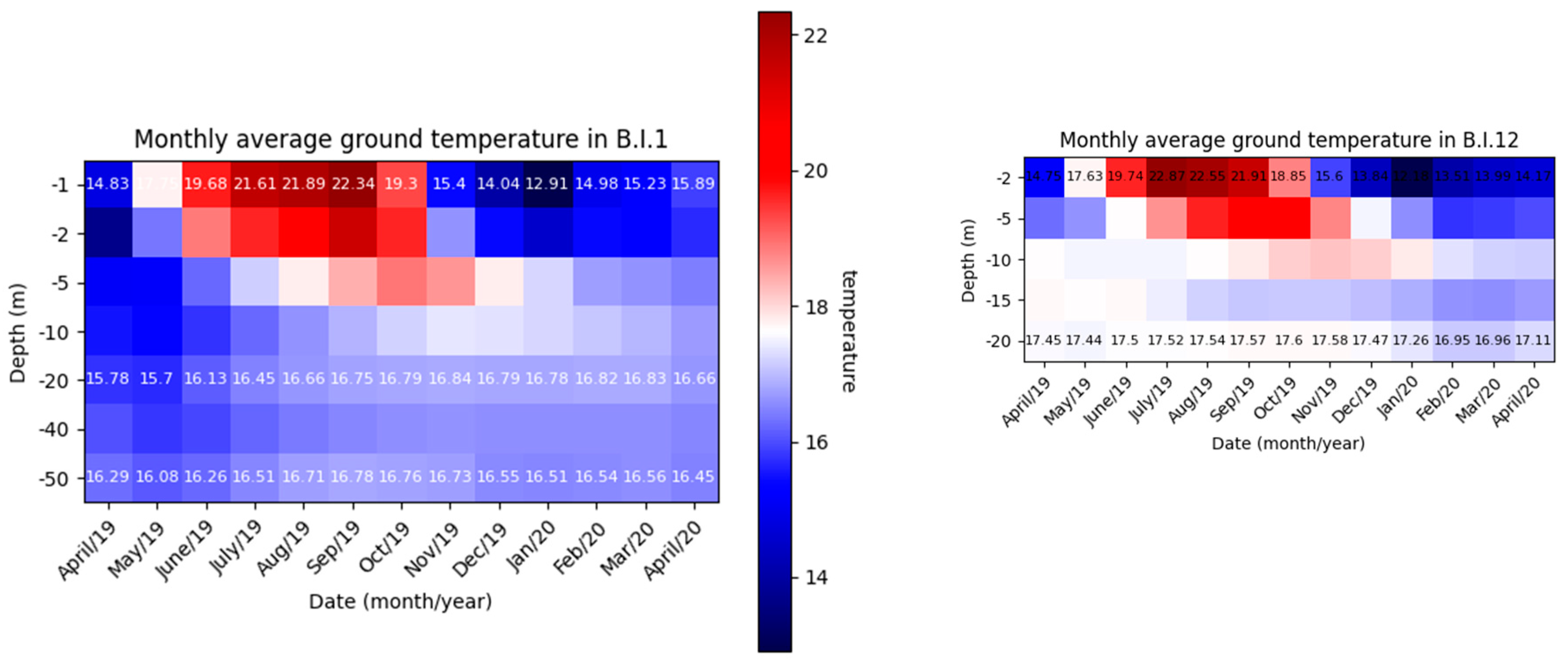

- Ground temperature monitored over time in both B.I.1 and B.I.12 at depths (1, 2, 5, and 10 m) follows the sinusoidal trend of the weather air temperature, however, with an increase in the phase shift and wavelength at depth. For instance, the minimum air temperature had occurred in January and the maximum in August. At 5 metres depth, they occurred, respectively, in April and in October. At 10 metres, the minimum temperature was registered in May and the maximum in November, with an offset of three months. This is a result of the significant thermal inertia and thermal diffusion of the near surface soil;

- It was observed a difference of 15 ºC in summer between the maximum air temperature and ground temperature at 1 m depth, and a difference of 8 ºC in winter between the minimum air temperature and the ground temperature at 1 m depth. This indicates an unbalanced thermal exchange between the building and the ground and the possibility of some trend to an increase in temperature in the long-term;

- At 15 and 20 m of depth, the ground temperature tends to have constant values between 15.3ºC and 17.4ºC in B.I.1, while in the borehole B.I.12, the ground temperature tends to have higher values between 16.35 and 18.18ºC. Thus, at a depth between 15 to 20 m, a constant temperature was observed in both boreholes;

- Ground temperature values, at 20 m of depth, is higher than the annual mean air temperature (15.46 C) by almost 1 ºC.

- At 2 m and 5 m, in summer, the average ground temperature obtained in B.I.12 is higher than that observed in B.I.1, while the opposite is observed in winter. This can be explained by the fact that B.I.12 is exposed to diurnal weather variations due to the absence of neighboring buildings, which is not the case in the B.I.1.

- At 10 m and 20 m, during the entire monitoring period, the average ground temperature obtained in B.I.12 is higher than that measured in B.I.1. The temperature difference between B.I.12 and B.I.1 varied from 0.2 ºC to 2.1ºC. This can be explained by the proximity of each investigation borehole to the closest BHE. In fact, B.I.12 is 1.9 m close to the BHE F16 and B.I.1 is located at 2.5 m from the BHE F17, therefore the BHEs operation is more visible in the B.I.12 rather than in the B.I.1.

4.2. Global ground temperature analysis

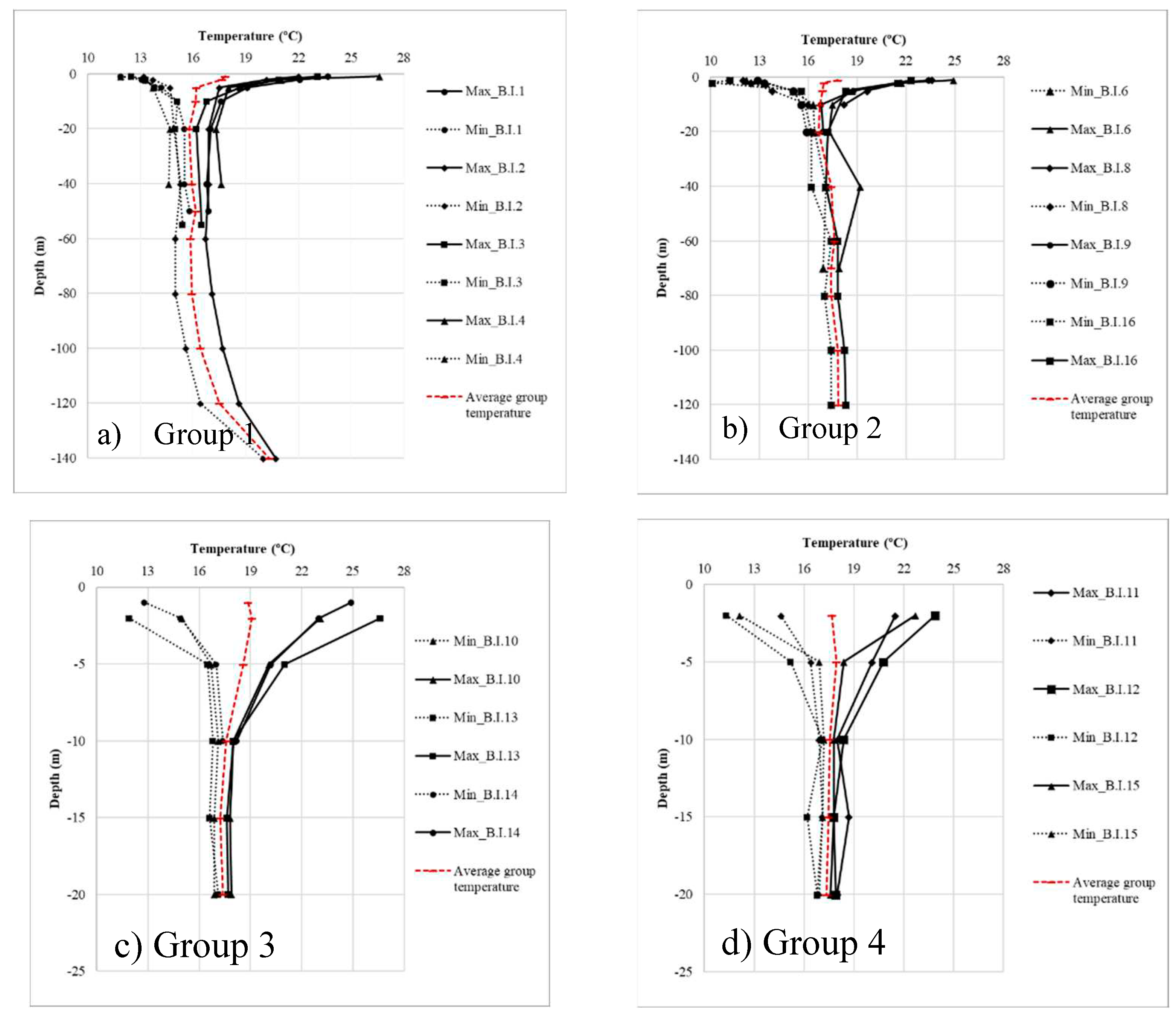

- The results are globally consistent, indicating good record quality;

- In agreement with the results previously observed in Figure 7, ground temperature in the superficial soil layers is mainly dominated by transient heat conduction, which is related to sinusoidal air temperature variations throughout the year;

- The effect of atmospheric temperature variations is observed till between 10 m and 15 m depths. It is believed that this relatively high depth of the atmospheric temperature effect is due to the relatively high conductivity resulting from the elevated position of the phreatic level (thermal conductivity superior to 2.5 W.m−1.K−1);

- At depths greater than 5 m, the monitored ground temperature shows similar results in boreholes of the same group;

- A general trend was observed in all boreholes at 1, 2 and 5 m depth: ground temperature in the heating season tends to be higher in boreholes closer to the building than in those which are farther. In the cooling season, the opposite is observed, i.e. the ground temperature is lower in boreholes closer to the building. This trend can be a result of the thermal boundary effect of the building on the surrounding ground temperature, and due to the heat flux between the building and the ground;

- The effect of the neighbouring BHE is evident throughout the depth of the monitoring boreholes, with an increase or decrease in the average temperature depending on the direction of the thermal flow;

- The difference between the extreme maximum and minimum temperature registered in the boreholes of group 1 is around 14 ºC at 2 m depth. This difference decreases to 4 ºC at 5 m depth and to 2 ºC at depth ≥ 20 m. As regard to group2, the difference is around 15 ºC at 2 m depth. This difference decreases to 6 ºC at 5 m depth and to 1 ºC at depth ≥ 20 m;

- As regards group 3 and 4, the difference between the extreme maximum and the minimum temperature registered in the borehole of group 3 and 4 is around 15 and 12 ºC at 2 m depth, respectively. This difference decreases to 4 and 7 ºC at 5 m depth and to between 1 to 2 ºC at depth ≥ 10 m. As a conclusion, the first three groups as they are located near the same façade have similar trends and values, while the fourth group has higher amplitude and difference as it is located on the opposite façade;

- The SGE system operation introduces thermal changes in the entire length of the boreholes due to the effect of circulating heat carrier fluid;

- It can be observed in group 1 that the soil layers temperature at large depths (≥ 80 m) is clearly affected by the geothermal gradient of up to 3 ºC/100m;

- It was observed that the average ground temperature of each group registered at 10 m depth shows similar values in groups 1 and 2 varying between 16 ºC and 17 ºC, and between 16 ºC and 18 ºC in groups 3 and 4. The first two groups are located in front of the same southeast façade of the case study building near to the neighbour building, while the third and fourth groups of boreholes are located near to the southwest façade which is more exposed to solar radiation due to the absence of the buildings shadings in this direction. The data suggests the existence of a boundary effect on the radiation imposed by the building.

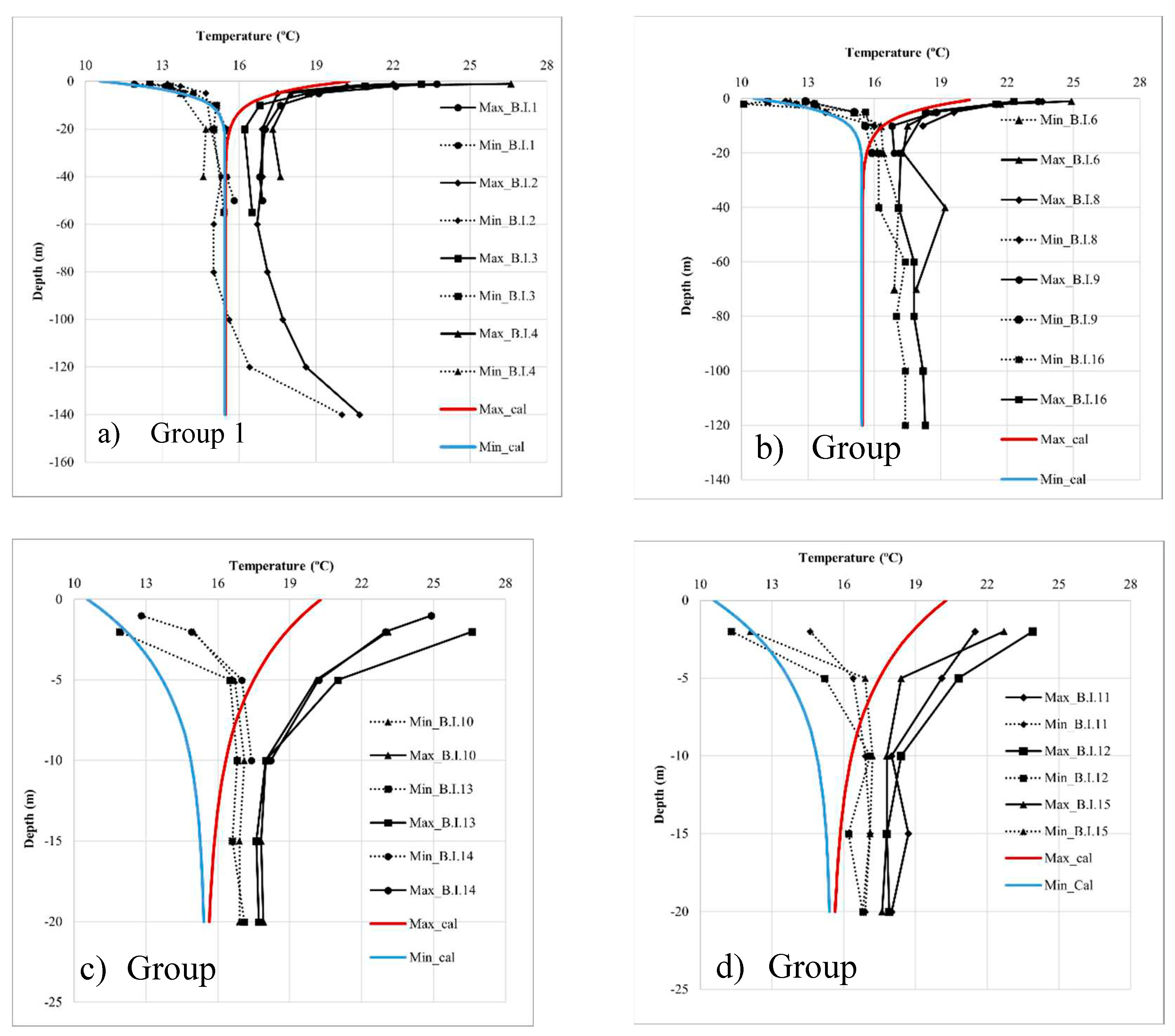

5. Undisturbed initial ground temperature estimation

- At 1 m and 2 m depths, soil temperature tends to close to the undisturbed ground temperature in winter, while in summer, the monitored temperature tends to be higher, showing a possible effect of the shallow geothermal system operation and/or of building boundary effect;

- The effect of the shallow geothermal system operation can also be observed at depth ≥ 20 m depth, where the extreme ground temperature measured in each group compared with the extreme numerical temperature. As regards to group 1, it is observed that the minimum temperature profile measured in boreholes of this group is 2ºC lower than the minimum numerical temperature. On the other hand, the maximum temperature measured in boreholes of this group is 1ºC higher than the maximum temperature computed numerically;

- At higher depths, boreholes in this group have higher ground temperatures in winter and summer than the numerically computed undisturbed ground temperature. This can also be attributed to the effect of the geothermal gradient mentioned above;

- A difference of 1 to 2 degrees between the maximum and the minimum ground temperature profiles was observed in the four groups, which in turn can manifest the ground capacity to respond thermally to the building energy needs by exchanging energy through the boreholes.

6. Conclusions and remarks

- Temperature profiles show that the impact of the seasonal atmospheric temperature variations action reaches depths as high as 20 m, probably due to the saturation conditions of soils and sand percentage in the proximity of Aveiro Lagoon, which results in the relatively high thermal conductivity range; and eventually due to some convection effect towards the lagoon which increased the heat transport;

- There is an effect of the geothermal system operation all over the entire boreholes depths obtained in groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, with the ground temperature amplitudes of 12 to 15 ºC at 1 m depth. This ground temperature amplitudes decrease to 1 to 2 ºC at depth higher than 10 m;

- There is an effect of the presence of the building and of the radiation that is evidenced by a higher thermal amplitude in relation to the maximum temperatures at the shallowest levels and on the southeast-oriented facades;

- Some of the deeper boreholes show an increase in temperature, which may be due to the development of a geothermal gradient.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Energy Agency IEA (2022). https://www.iea.org/, accessed on 16 of August of 2023.

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2016). Mapping and Analysis of the Current and Future (2020-2030) heating/cooling fuel deployment (fossils/renewables). Retrieved from: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/publications/mapping-and-analyses-current-and-future-2020-2030-heatingcooling-fuel-deployment-fossilrenewables-1_en, accessed on 16 of August of 2023.

- Haar, Lawrence. "An empirical analysis of the fiscal incidence of renewable energy support in the European Union.". Energy Policy 2020, 143, 111483. [CrossRef]

- Brandl, Heinz. Energy foundations and other thermo-active ground structures. Géotechnique 2006, 56, 81–122. [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, I.; Florides, G.; Tassou, S.; Tsiolakis, E.; Christodoulides, P. Methodology for estimating the ground heat absorption rate of Ground Heat Exchangers. Energy 2017, 127, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roka, R.; Figueiredo, A.; Vieira, A.; Cardoso, J. A systematic review on shallow geothermal energy system: A light into six major barriers. Soils and Rocks 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.; Alberdi-Pagola, M.; Christodoulides, P.; Javed, S.; Loveridge, F.; Nguyen, F.; Cecinato, F.; Maranha, J.; Florides, G.; Prodan, I.; Van Lysebetten, G.; Ramalho, E.; Salciarini, D.; Georgiev, A.; Rosin-Paumier, S.; Popov, R.; Lenart, S.; Poulsen, S. E.; Radioti, G. Characterisation of ground thermal and thermo-mechanical behaviour for shallow geothermal energy applications. Energies 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, I.; Sebarchievici, C. Using Ground-Source Heat Pump Systems for Heating/Cooling of Buildings. In (Ed.), Advances in Geothermal Energy. IntechOpen 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florides, G.; Kalogirou, S. Ground heat exchangers—A review of systems, models and applications, Renew. Energy 2007, 32, 2461–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larwa, B. Heat transfer model to predict temperature distribution in the ground. Energies 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badache, M.; Eslami-Nejad, P.; Ouzzane, M.; Aidoun, Z.; Lamarche, L. A new modelling approach for improved ground temperature profile determination. J. Renew. Energy 2016, 85, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorska-Silva, I.; Kadela, M.; Fedorowicz, L. Variations of Ground Temperature in Shallow Depths in the Silesian Region. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 603, 052024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popiel, C. O.; Wojtkowiak, J.; Biernacka, B. Measurements of temperature distribution in ground. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 2001, 25, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcek, A. O.; Tinjum, J. M.; Hart, D. J. Numerical Modeling of Ground Temperature Response in a Ground-Source Heat Pump System (GSHP). Geo-Congress 2014 Technical Papers. [CrossRef]

- Beier, R. A.; Smith, M. D.; Spitler, J. D. Reference data sets for vertical borehole ground heat exchanger models and thermal response test analysis. Geothermics 2011, 40, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Wang, Y. Modeling the interactions between the performance of ground source heat pumps and soil temperature variations. Energy for Sustainable Development 2014, 23, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Shen, R.; Feng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Soil thermal balance analysis for a ground source heat pump system in a hot-summer and cold-winter region. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S. , Zeng, Y., Wen, J., Zhao, H., Su, Z. Estimation of Penetration Depth from Soil Effective Temperature in Microwave Radiometry. Remote Sens 2018, 10, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naicker, S. S.; Rees, S. J. Performance analysis of a large geothermal heating and cooling system. Renewable Energy 2018, 122, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinti, F.; Carri, A.; Kasmaee, S.; Valletta, A.; Segalini, A.; Bonduà, S.; Bortolotti, V. Ground temperature monitoring for a coaxial geothermal heat exchangers field: Practical aspects and main issues from the first year of measurements. Rudarsko-Geološko-Naftni Zbornik 2018, 33, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vienken, T.; Kreck, M.; Dietrich, P. Monitoring the impact of intensive shallow geothermal energy use on groundwater temperatures in a residential neighbourhood. Geotherm Energy 2019, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Lee, Y. Evaluation of ground temperature changes by the operation of the geothermal heat pump system and climate change in Korea. Water 2020, 12, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, A.; Lapa, J.; Cardoso, C.; Macedo, J.; Rodrigues, F.; Vieira, A.; Pinto, A.; Maranha, J.R. Shallow geothermal systems for Aveiro University departments: A survey through the energy efficiency and thermal comfort. 17th European Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, ECSMGE 2019 Proceedings, Reykjavik, Iceland, 1 -. 6 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, J.M.; Lopes, J.F.; Dekeyser, I. Tidal Propagation in Ria de Aveiro Lagoon, Portugal. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Part B: Hydrology, Oceans and Atmosphere 2000, 25, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Néri, C. S. G. Study of Mechanical Behaviour of soils under the influence of Geothermal Systems. Master degree thesis, Aveiro University, Aveiro, Portugal, (in Portuguese), 2016.

- TPSYS02 Thermal Conductivity Measurement System. 2003. Hukseflux Thermal Sensors. Available at: http://www.hukseflux.com.

- Farouki, O. Evaluation of methods for calculating soil thermal conductivity. US Army Corps of Engineers, Cold Regions Research & Engineering Laboratory 1982, 82, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Aljundi, K.; Vieira, A.; Maranha, J.; Lapa, J.; Cardoso, R. Effects of Temperature, Test Duration and Heat Flux in Thermal Conductivity Measurements under Transient Conditions in Dry and Fully Saturated States. E3S Web of Conferences 2020, 195, 04007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Rohn, J.; Xiang, W.; Bertermann, D.; Blum, P. A review of ground investigations for ground source heat pump (GSHP) systems. Energy Build 2016, 117, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michot, A.; Smith, D. S.; Degot, S.; Gault, C. Thermal conductivity, and specific heat of kaolinite: Evolution with thermal treatment. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2008, 28, 2639–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H. R.; Rees, S. W. Measured and simulated heat transfer to foundation soils. Géotechnique 2009, 59, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Zeitschrift. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Portuguese Institute for Sea and Atmosphere, I. P. (IPMA, IP). Retrieved from https://www.ipma.pt/pt accessed on 16 of August of 2023.

- Kusuda, T. ; R. Achenbach, P. Earth Temperature and Thermal Diffusivity at Selected Stations in the United States. In National Bureaau of Standards Report, 1965.

- Cui, W.; Liao, Q.; Chang, G.; Chen, G.; Peng, Q.; Jen, T. C. Measurement and prediction of undisturbed underground temperature distribution. ASME 2011 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. IMECE 2011, 4, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M. R.; Zain, M. F. M.; Kaish, A. B. M. A.; Jamil, M. Underground soil and thermal conductivity materials-based heat reduction for energy-efficient building in tropical environment. Indoor Built Environ. 2015, 24, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hinti, I.; Al-Muhtady, A.; Al-Kouz, W. Measurement and modelling of the ground temperature profile in Zarqa, Jordan for geothermal heat pump applications. J. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 123, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| λ (W.m−1.K−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry soil | Saturateda and unsaturatedb | ||||

| Soil type | Depth (m) | Experimental value | Reference value | Experimental value | Reference value |

| Clay and sandy clay | 0 - 6 | [0.21, 0.39] | 0.35 | [1.13, 2.40]a Sr ≈ 35% |

[1.42, 2.70]b |

| Claystone | 6 - 10 | - | 0.15 | [1.88, 2.59]a Sr ≈ 70% |

[1.18-1.80]b |

| [up to 2.50]a | |||||

| Depth (m) | Gs | w% | n | Sr | λ (W.m-1.K-1) |

Soil type | Unified Soil Classification System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 – 6 | 2.62 | 13.74 | 0.42 | 0.5 | 1.93 | Fine | Clay and sandy clay (ML) |

| 6 – 18 | 2.63 | 18.38 | 0.32 | 1.0 | 2.60 | Fine | Claystone (CL) |

| 18 – 24 | 2.65 | 10.58 | 0.22 | 1.0 | 3.25 | Coarse | Clayey sand (SC) |

| 24 – 78 | 2.64 | 32.81 | 0.44 | 1.0 | 2.11 | Fine | Claystone (CL) |

| 78 – 84 | 2.64 | 24.57 | 0.39 | 1.0 | 2.24 | Coarse | Clayey sand (SC) |

| 84 – 90 | 2.62 | 31.44 | 0.45 | 1.0 | 1.98 | Fine | Clay and sandy clay (ML) |

| 90 – 132 | 2.63 | 23.84 | 0.38 | 1.0 | 2.28 | Coarse | Clayey sand (SC) |

| Depth (m) | Gs | w% | n | Sr |

λ (W.m-1.K-1) |

Soil type | Unified Soil Classification System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 – 6 | 2.64 | 9.30 | 0.20 | 0.5 | 2.49 | Coarse | Clay and sandy clay (ML) |

| 6 – 18 | 2.59 | 18.90 | 0.33 | 1.0 | 2.57 | Fine | Claystone (CL) |

| 18 – 24 | 2.58 | 17.20 | 0.31 | 1.0 | 2.69 | Coarse | Clayey sand (SC) |

| 24 – 78 | 2.57 | 39.57 | 0.50 | 1.0 | 1.81 | Fine | Claystone (CL) |

| 78 – 84 | 2.56 | 21.90 | 0.36 | 1.0 | 2.40 | Coarse | Clayey sand (SC) |

| 84 – 90 | 2.58 | 21.70 | 0.36 | 1.0 | 2.41 | Coarse | Clay and sandy clay (ML) |

| 90 – 132 | 2.62 | 20.56 | 0.35 | 1.0 | 2.46 | Coarse | Clayey sand (SC) |

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of investigation borehole | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 16 | 10 | 13 | 14 | 11 | 12 | 15 |

| Depth (m) | 50 | 140 | 55 | 40 | 120 | 70 | 10 | 20 | 120 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Source | Location | Soil type | λ (W.m-1.K-1) |

Penetration depth (m) |

Annual average air temperature (ºC) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diurnal | Annual | |||||

| [34] | Lemont, USA | * | 0.6 to 4.0 | 0.9 | 3.0 | 10.0 |

| [13] | Poznan, Poland | Sandy soil, loam and clay until 3 m Silty soil after 3 m depth |

1.8 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 9.4 |

| [35] | Chongqing, China | Sandstone and mudstone | 2.5 | 1.0 | 11.0 | 18.2 |

| [36] | Malaysia | Sandy soil | N.A. | 0.5 | 10.0 | 27.5 |

| [37] | Zarqa, Jordan | Fine-silty, mixed, calcareous | 1.2 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 21 |

| [18] | Jamshedpur, India | Sand and clay | N.A. | 0.4 | 4.0 | 28.7 |

| a | Aveiro, Portugal | 2.2 to 4.4 | 1.0 | 10.0 | 15.5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).