Submitted:

20 August 2023

Posted:

23 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Preparation

2.1.1. NO2 Monitoring Stations and National Highways Map in China

2.1.2. Himawari-8 TOAR Data

2.1.3. Meteorological and Geographic Data

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Data Matching

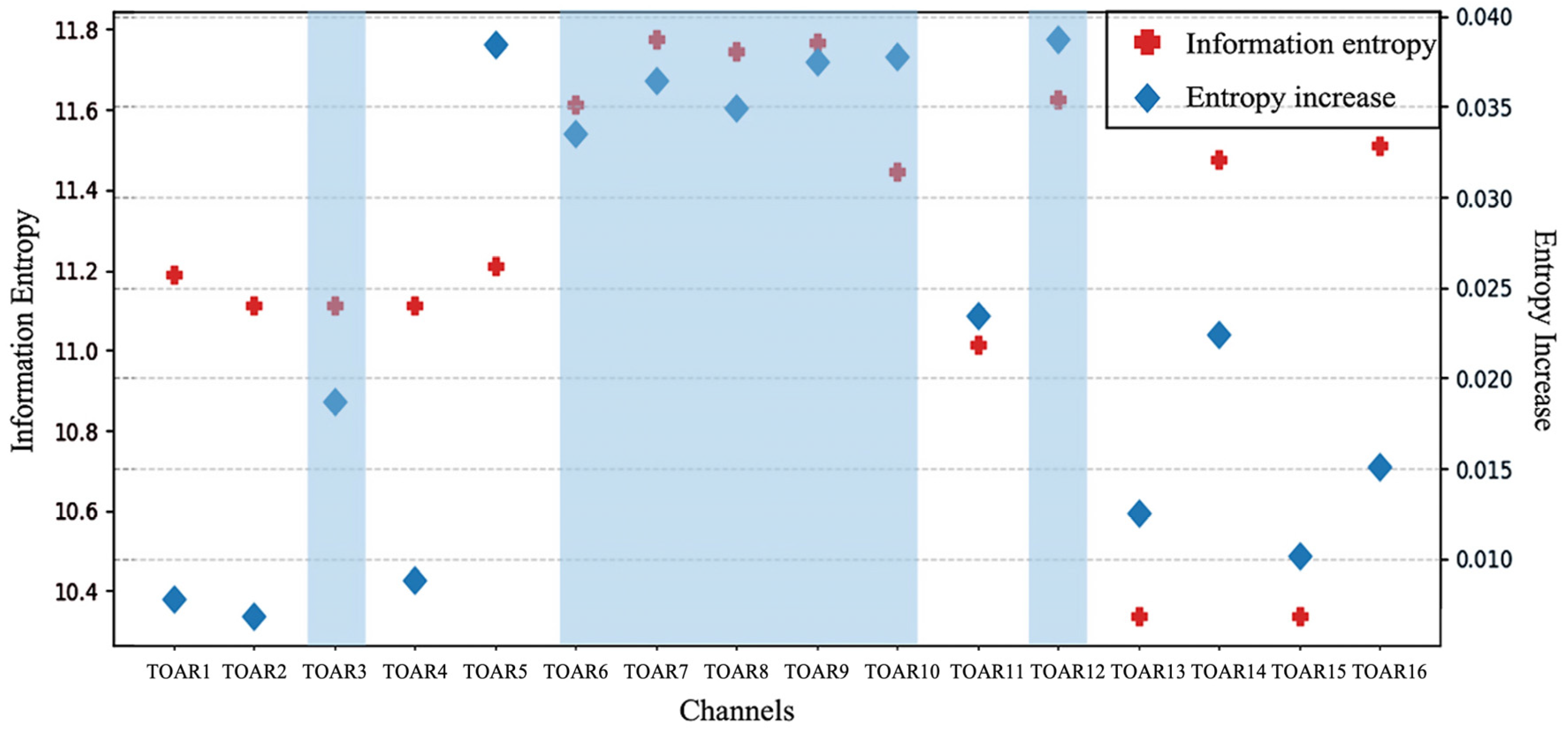

2.2.2. Feature Selection Based on Information Entropy

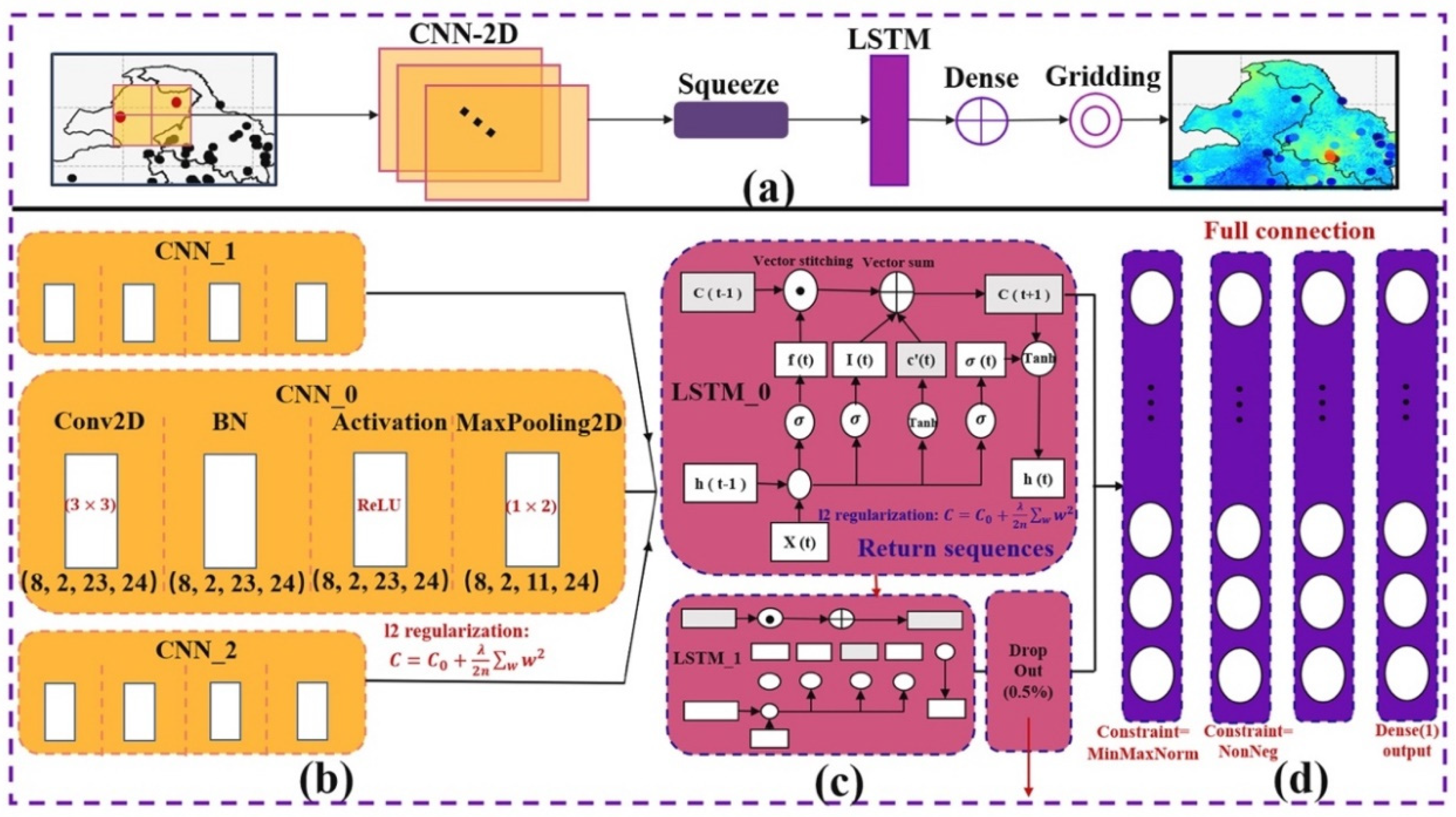

2.2.3.2. DCNN-LSTM

2.2.4. Integration Gradient Approximation and Beta Coefficients

3. Results

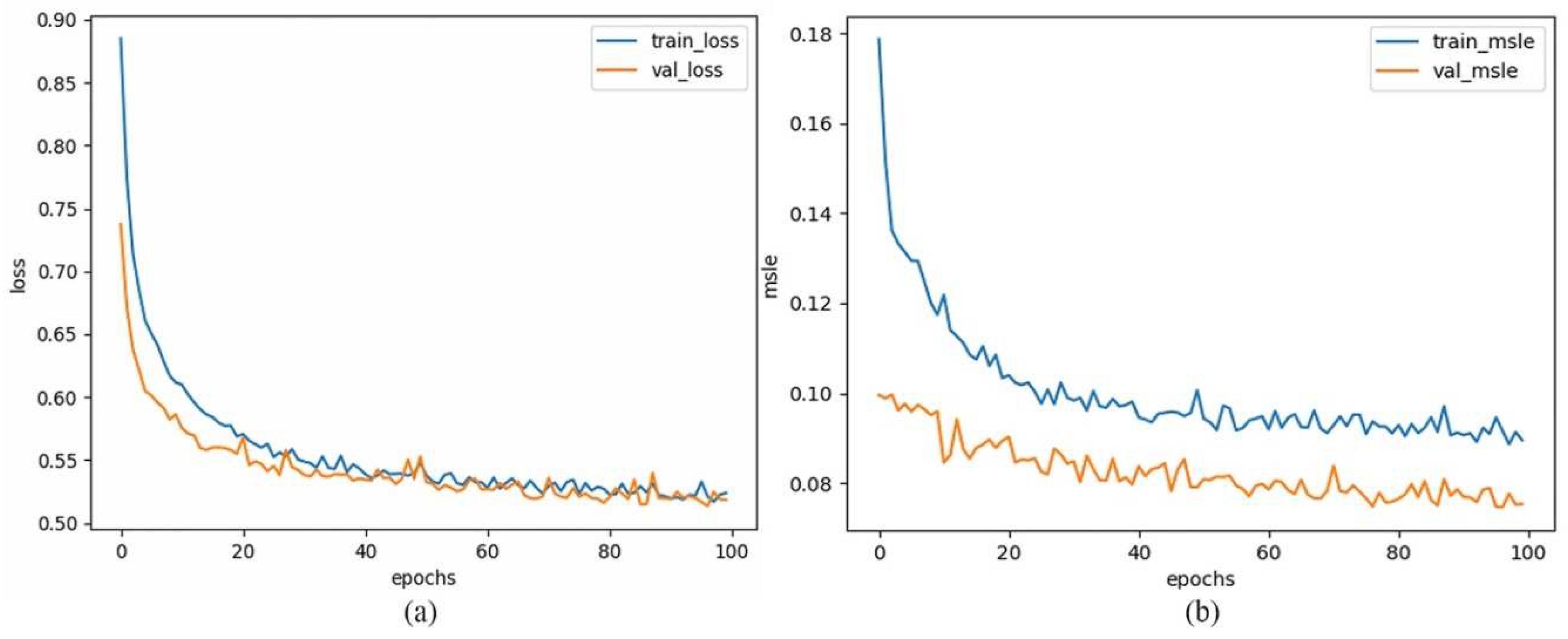

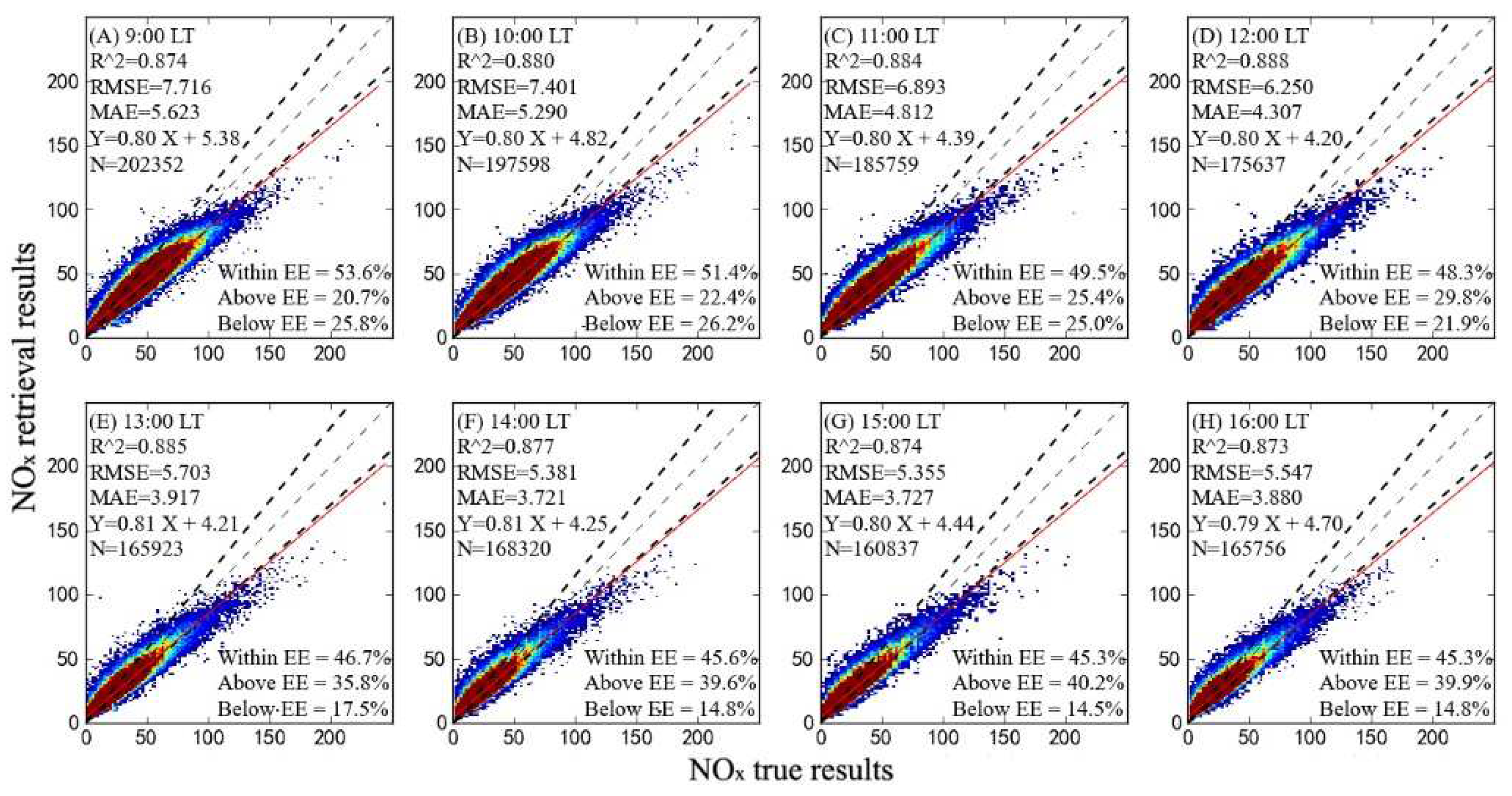

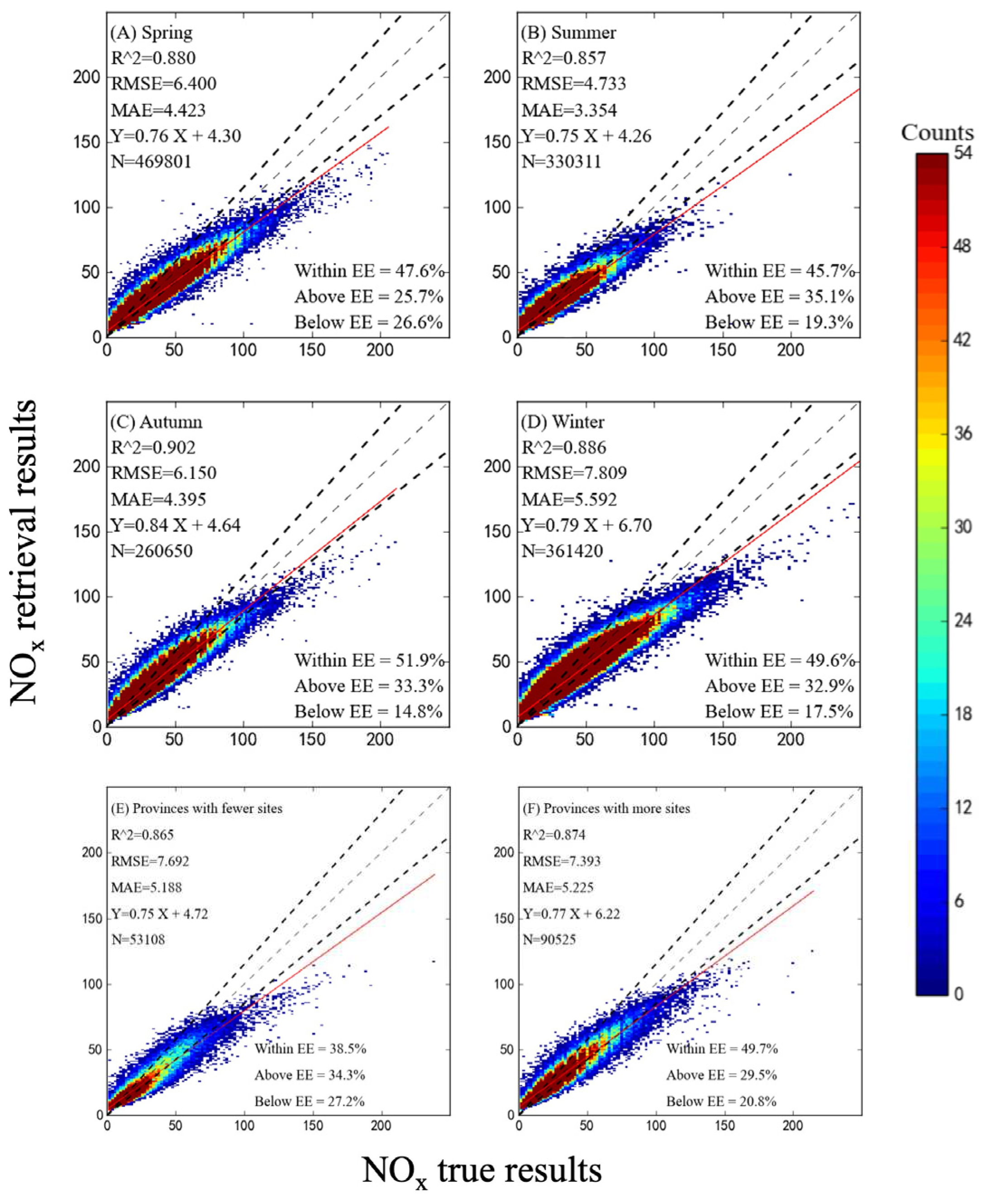

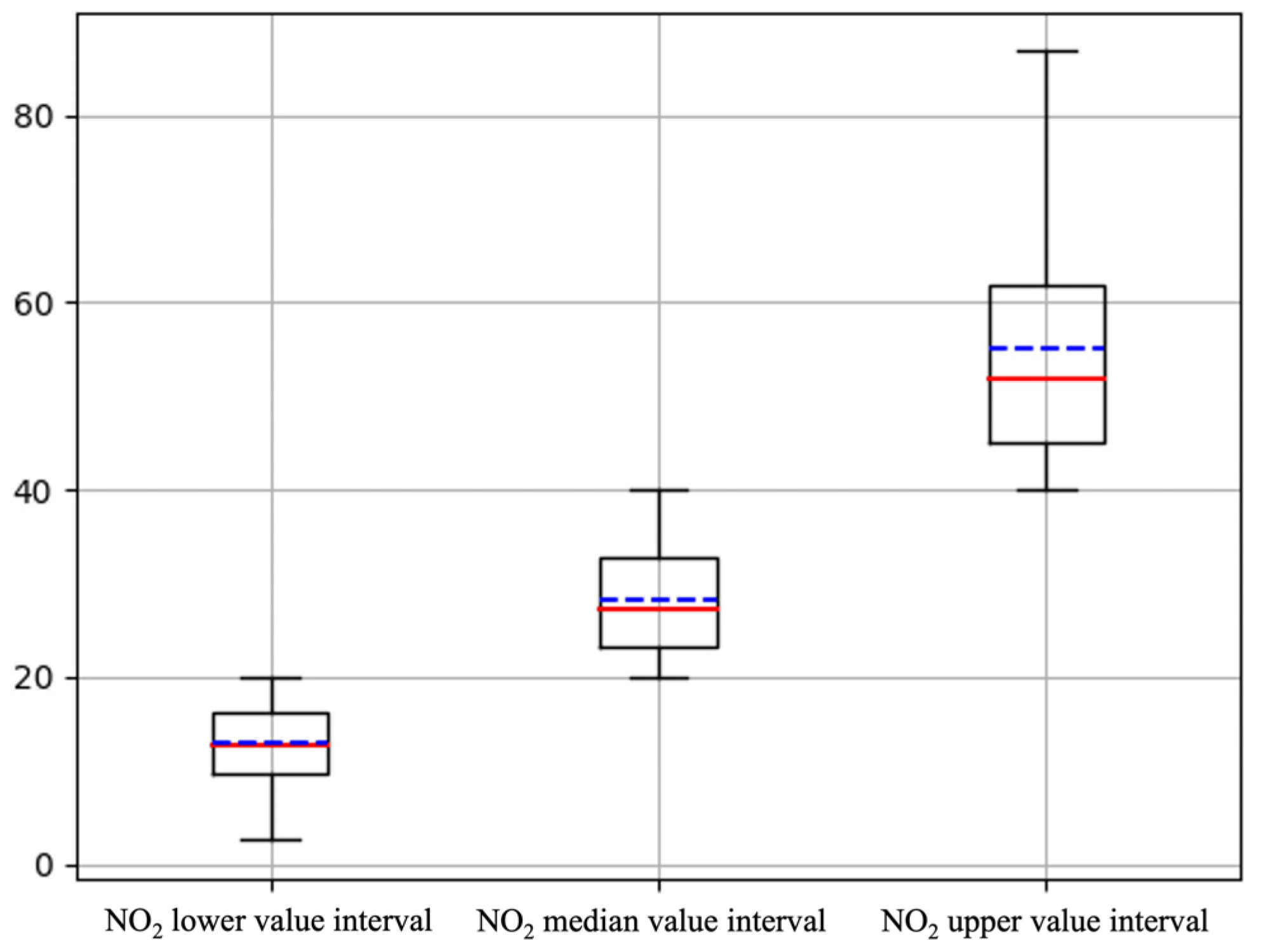

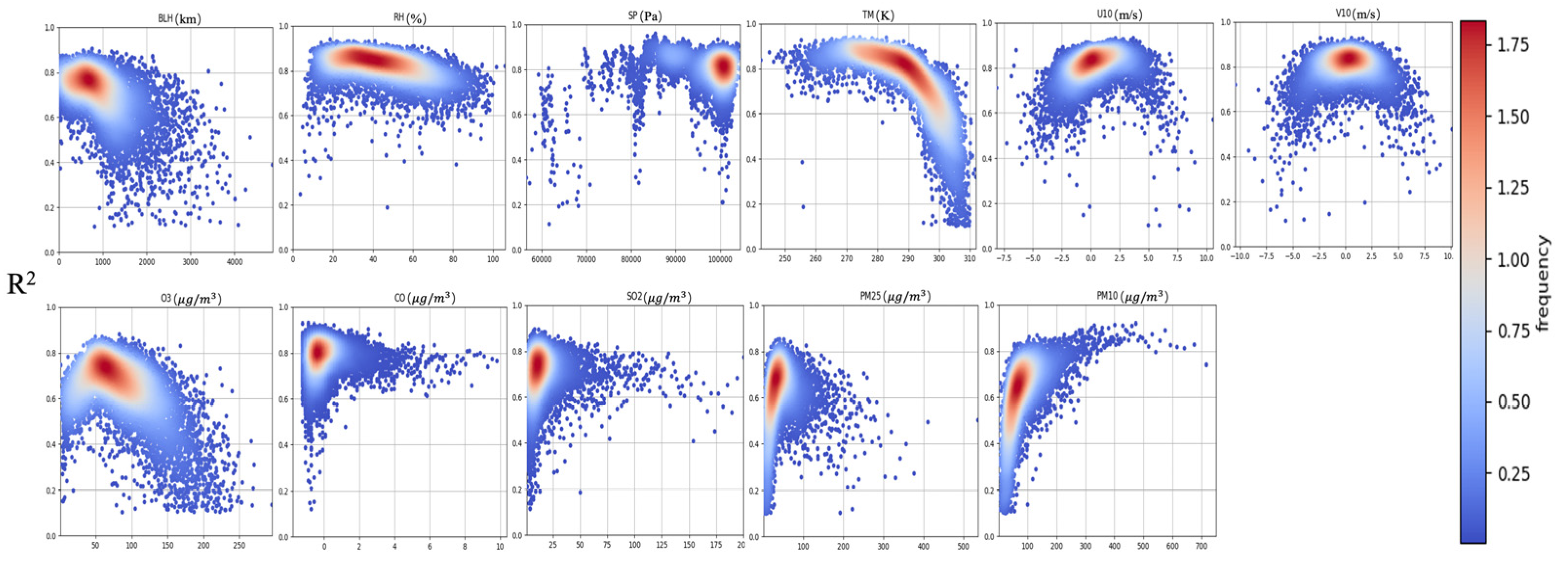

3.1. Model Performance Evaluation

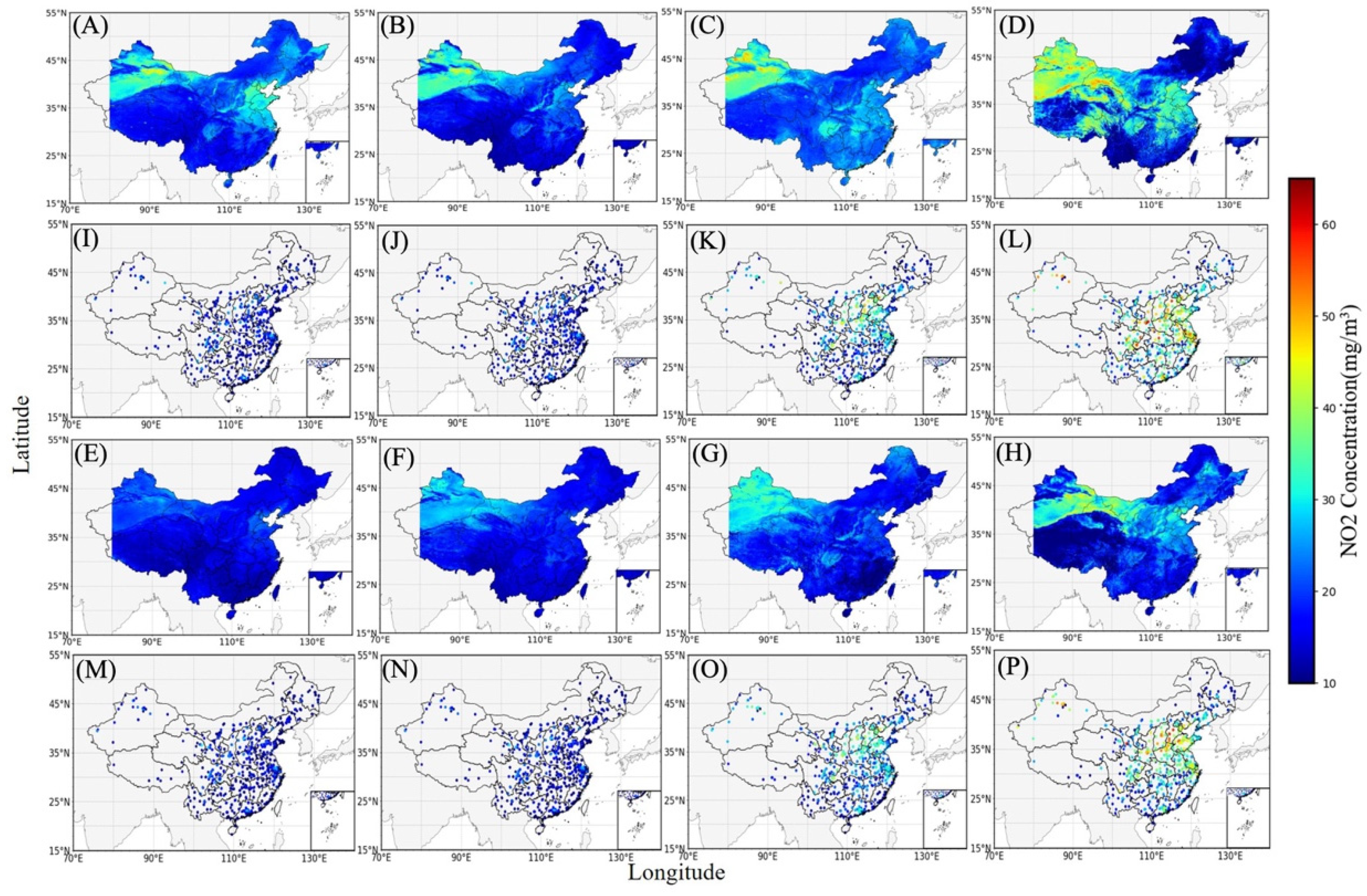

3.2. Retrieval Results

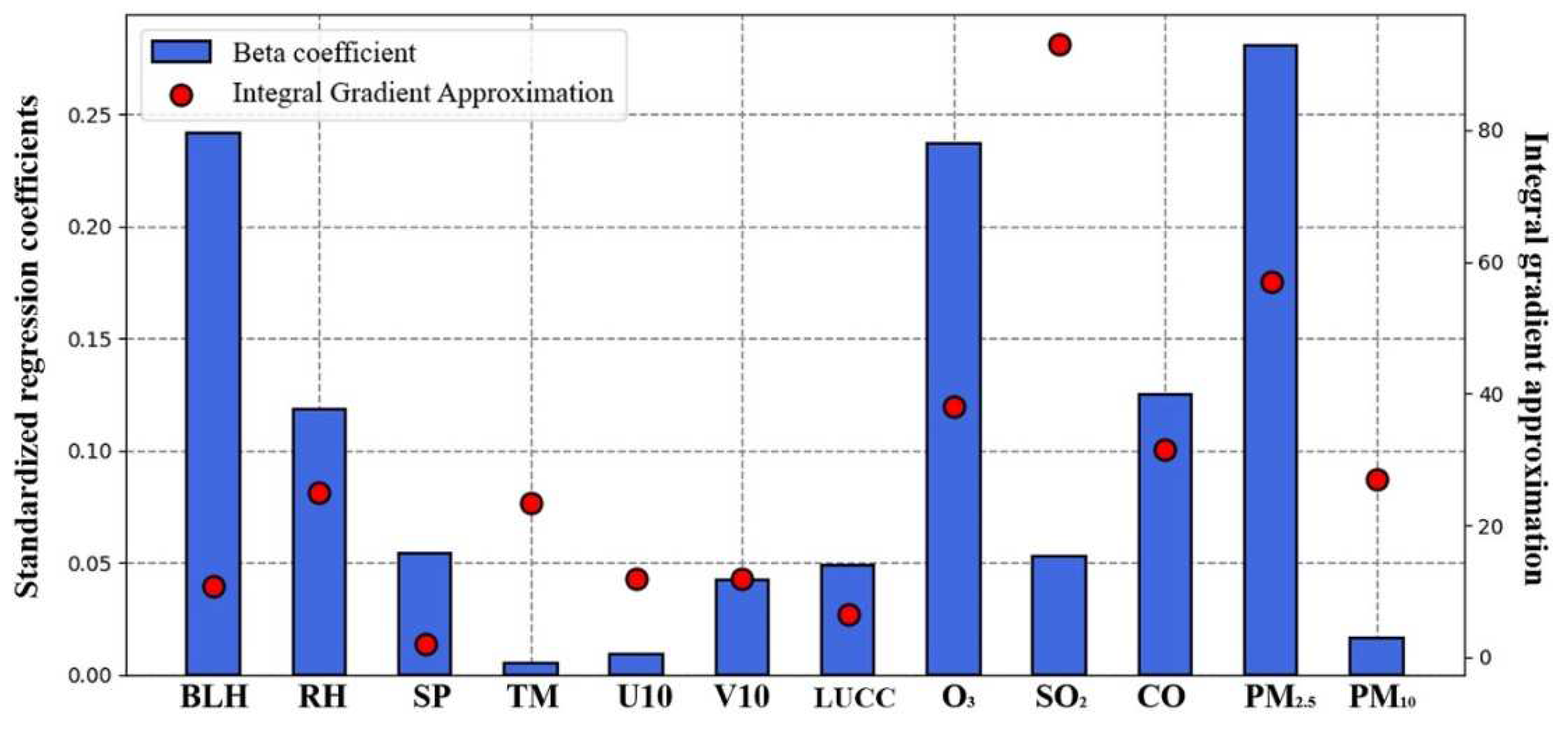

3.3. Factor Interpretability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, Q., X. Hong, and L.E. Wold. Cardiovascular Effects of Ambient Particulate Air Pollution Exposure of the article. Circulation. 2010, 121, 2755–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook and D., R. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association of the article. Circulation. 2004, 109, 2655–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciampi, Q. , et al. Nitrogen dioxide component of air pollution increases pulmonary congestion assessed by lung ultrasound in patients with chronic coronary syndromes of the article. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2022, 29, 26960–26968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S. , et al. Multiscale spatiotemporal variations of NO(x) emissions from heavy duty diesel trucks in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of the article. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 854, 158753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. and W. Chen. First satellite-based regional hourly NO(2) estimations using a space-time ensemble learning model: A case study for Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region, China of the article. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K. , et al. Spatio-temporal variations in SO(2) and NO(2) emissions caused by heating over the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region constrained by an adaptive nudging method with OMI data of the article. Sci Total Environ. 2018, 642, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L. , et al. Vertical profiles of O(3), NO(2) and PM in a major fine chemical industry park in the Yangtze River Delta of China detected by a sensor package on an unmanned aerial vehicle of the article. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.J. , et al. Global fine-scale changes in ambient NO(2) during COVID-19 lockdowns of the article. Nature. 2022, 601, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L. , et al. Analysis on the Characteristics of Air Pollution in China during the COVID-19 Outbreak of the article. Atmosphere. 2021, 12, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y. , et al. Machine learning-based estimation of ground-level NO(2) concentrations over China of the article. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y. , et al. Chemistry, transport, emission, and shading effects on NO(2) and O(x) distributions within urban canyons of the article. Environ Pollut. 2022, 315, 120347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J. , et al. The influence of solar natural heating and NO<sub>x</sub>-O<sub>3</sub> photochemistry on flow and reactive pollutant exposure in 2D street canyons of the article. The Science of the total environment. 2021, 759, 143527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. , et al. Development of an integrated machine-learning and data assimilation framework for NO(x) emission inversion of the article. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 871, 161951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X. , et al. Analysis of the Spatial–Temporal Distribution Characteristics of NO2 and Their Influencing Factors in the Yangtze River Delta Based on Sentinel-5P Satellite Data of the article. Atmosphere. 2022, 13, 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X. , et al. Nitrate pollution source apportionment, uncertainty and sensitivity analysis across a rural-urban river network based on delta(15)N/delta(18)O-NO(3)(-) isotopes and SIAR modeling of the article. J Hazard Mater. 2022, 438, 129480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. , et al. Source analysis of the tropospheric NO(2) based on MAX-DOAS measurements in northeastern China of the article. Environ Pollut. 2022, 306, 119424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. , et al. Spatiotemporal variations of NO(2) and its driving factors in the coastal ports of China of the article. Sci Total Environ 2023, 162041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J. and W. Chen. First satellite-based regional hourly NO2 estimations using a space-time ensemble learning model: A case study for Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region, China of the article. Science of The Total Environment. 2022, 820, 153289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. , et al. Multiscale time-lagged correlation networks for detecting air pollution interaction of the article. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 2022, 602, 127627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. , et al. Estimation of near-surface ozone concentration and analysis of main weather situation in China based on machine learning model and Himawari-8 TOAR data of the article. Science of the Total Environment. 2023, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.H. , et al. High temporal and spatial resolution PM2.5 dataset acquisition and pollution assessment based on FY-4A TOAR data and deep forest model in China of the article. Atmospheric Research. 2022, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S. and J. Schmidhuber. Long Short-Term Memory of the article. Neural Computation. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H. , et al. Rainfall-runoff modeling using LSTM-based multi-state-vector sequence-to-sequence model of the article. Journal of Hydrology. 2021, 598, 126378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, M.E. , et al. Deep learning classifiers for hyperspectral imaging: A review of the article. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. 2019, 158, 279–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R. , et al. A review and evaluation of the state-of-the-art in PV solar power forecasting: Techniques and optimization of the article. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2020, 124, 109792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F. , et al. Ultrasonic adaptive plane wave high-resolution imaging based on convolutional neural network of the article. NDT & E International. 2023, 138, 102891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasebi, P. , et al. Machine learning in geo- and environmental sciences: From small to large scale of the article. Advances in Water Resources. 2020, 142, 103619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, C. , et al. Estimation of Atmospheric PM10 Concentration in China Using an Interpretable Deep Learning Model and Top-of-the-Atmosphere Reflectance Data From China's New Generation Geostationary Meteorological Satellite, FY-4A of the article. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres. 2022, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.P. , et al. The climatology of planetary boundary layer height in China derived from radiosonde and reanalysis data of the article. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2016, 16, 13309–13319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.H. T. Li, and R. Svarverud. Ecological civilization: Interpreting the Chinese past, projecting the global future of the article. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions. 2018, 53, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.H. , et al. Prospect Analysis for the Complementary Development of Gas-Fueled and Electric Vehicles in China of the article. 3rd Annual International Conference on Sustainable Development [ICSD). 2017, 111, 252–258. [Google Scholar]

- Ambade, B. , et al. Health Risk Assessment, Composition, and Distribution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Drinking Water of Southern Jharkhand, East India of the article. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2021, 80, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambade, B. , et al. COVID-19 lockdowns reduce the Black carbon and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons of the Asian atmosphere: source apportionment and health hazard evaluation of the article. Environment, Development and Sustainability. 2021, 23, 12252–12271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charakopoulos, A.K., G. A. Katsouli, and T.E. Karakasidis. Dynamics and causalities of atmospheric and oceanic data identified by complex networks and Granger causality analysis of the article. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 2018, 495, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K. , et al. Causality guided machine learning model on wetland CH4 emissions across global wetlands of the article. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 2022, 324, 109115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Implication | Time series length | Unit | Spatial resolution | Temporal resolution | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO2 | NO2 observation data | March 2018 to February 2020 | μg/m³ | site | Hourly | CNEMC |

| TOAR1 | AHI blue band (0.46μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR2 | AHI green band (0.51μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR3 | AHI red band (0.64μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR4 | AHI Near-infrared band (0.86μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR5 | AHI Near-infrared band (1.5μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR6 | AHI Near-infrared band (2.3μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR7 | AHI Infrared band (3.9μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR8 | AHI Infrared band (6.2μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR9 | AHI Infrared band (6.9μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR10 | AHI Infrared band (7.3μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR11 | AHI Infrared band (8.6μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR12 | AHI Infrared band (9.6μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR13 | AHI Infrared band (10.4μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR14 | AHI Infrared band (11.2μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR15 | AHI Infrared band (12.4μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| TOAR16 | AHI Infrared band (13.3μm) | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Hourly | JMA |

| BLH | Boundary layer height | March 2018 to February 2020 | m | 0.25°×0.25° | Hourly | ERA-5 |

| TM | 2m temperature | March 2018 to February 2020 | K | 0.1°×0.1° | Hourly | ERA-5 |

| RH | Relative humidity | March 2018 to February 2020 | % | 0.25°×0.25° | Hourly | ERA-5 |

| U10 | 10m u component of wind | March 2018 to February 2020 | m/s | 0.1°×0.1° | Hourly | ERA-5 |

| V10 | 10m v component of wind | March 2018 to February 2020 | m/s | 0.1°×0.1° | Hourly | ERA-5 |

| SP | Surface pressure | March 2018 to February 2020 | Pa | 0.1°×0.1° | Hourly | ERA-5 |

| LUCC | The type of surface | March 2018 to February 2020 | / | 0.05°×0.05° | Yearly | NASA |

| Key hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Loss | Mean Absolute Error |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Learning Rate | 0.0009 |

| Epoch | 100 |

| Batch size | 8 |

| Activation functions | ReLU |

| Regularizing functions | Regularizers.L2 (0.005) |

| Hidden layers | 30 |

| Dropout | 0.05 |

| Trainable params | 39708 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).