Submitted:

09 August 2023

Posted:

10 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. DNA extraction

2.3. 16S rRNA sequencing

2.4. Data analysis

3. Results

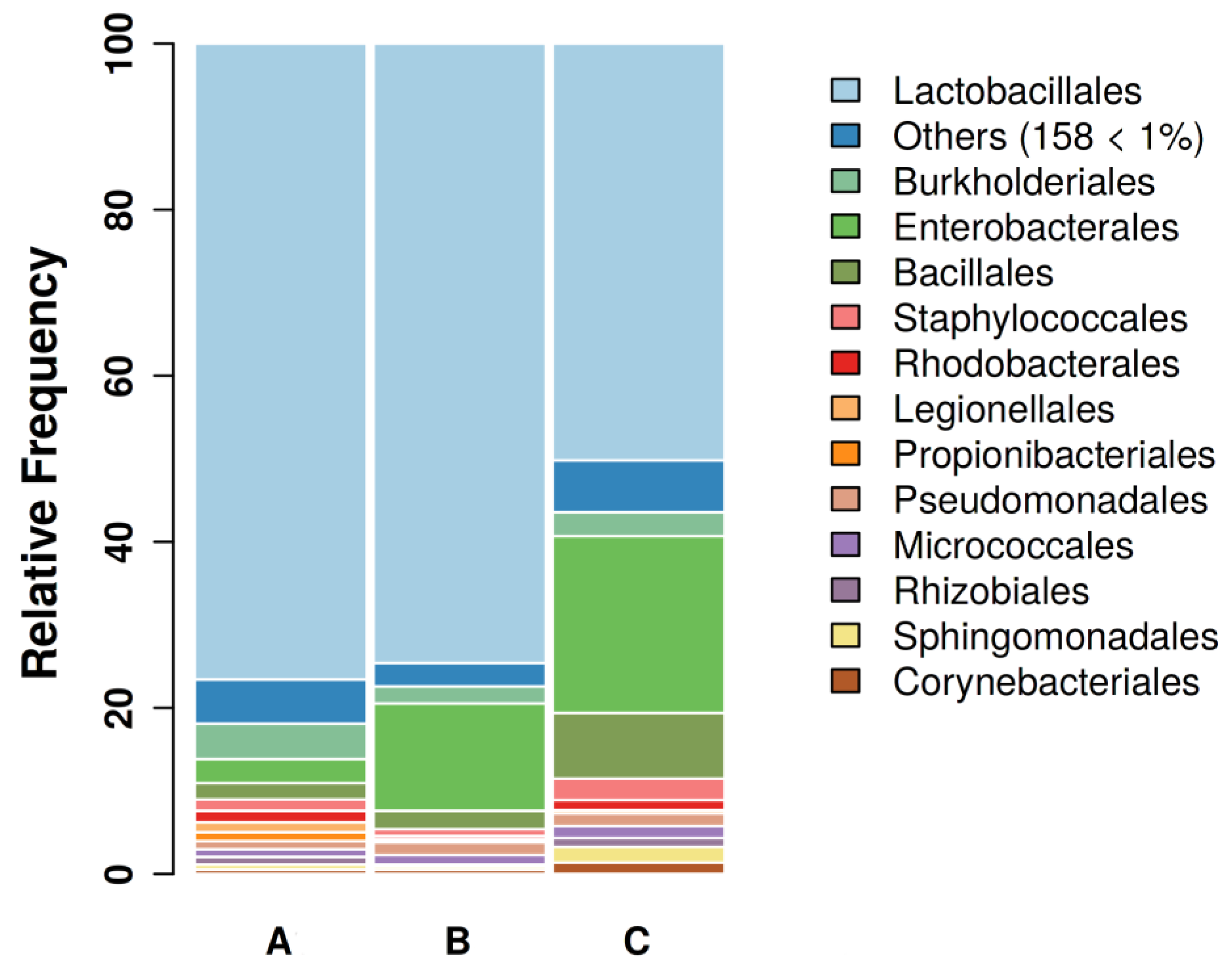

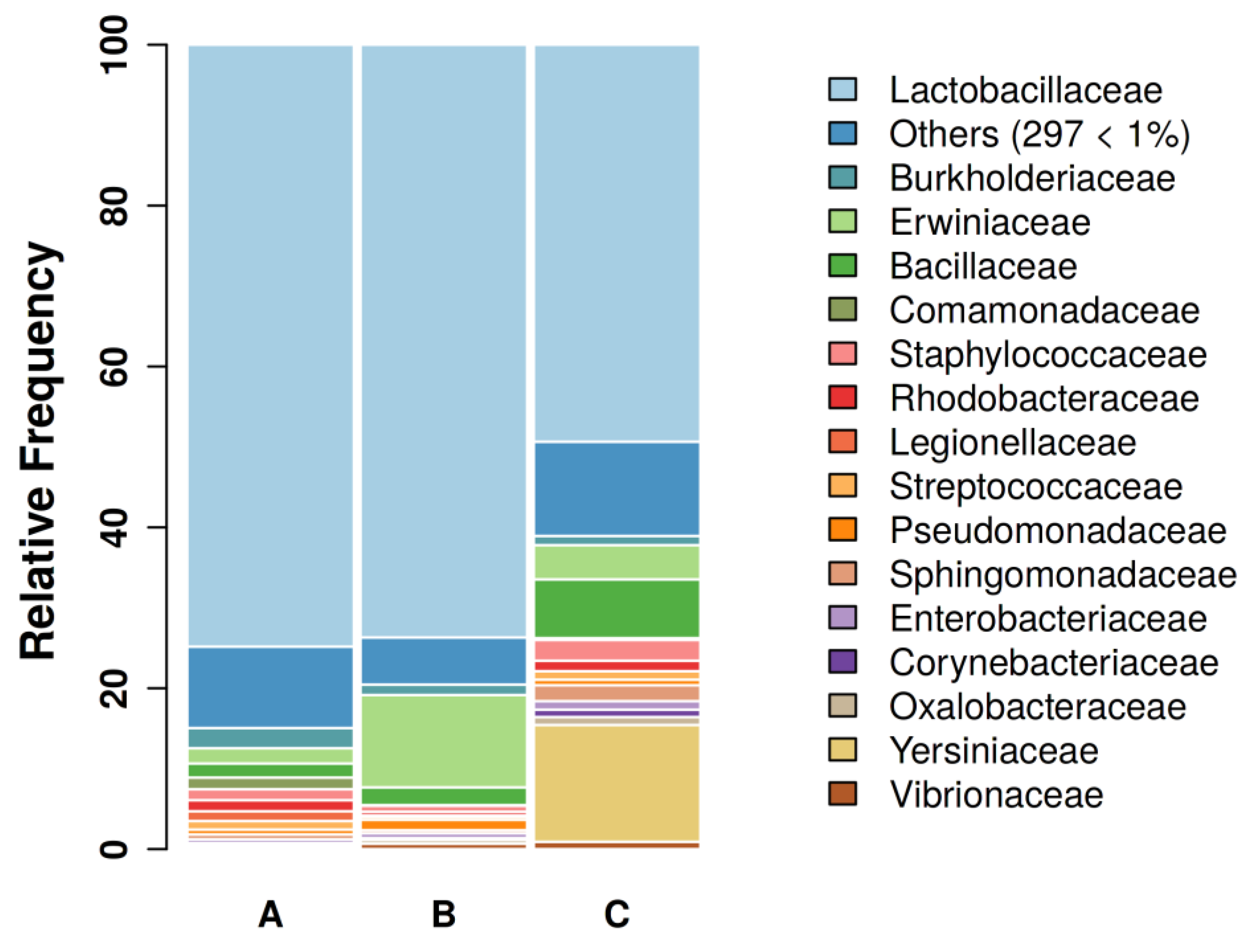

3.1. Sequencing results and GBC composition

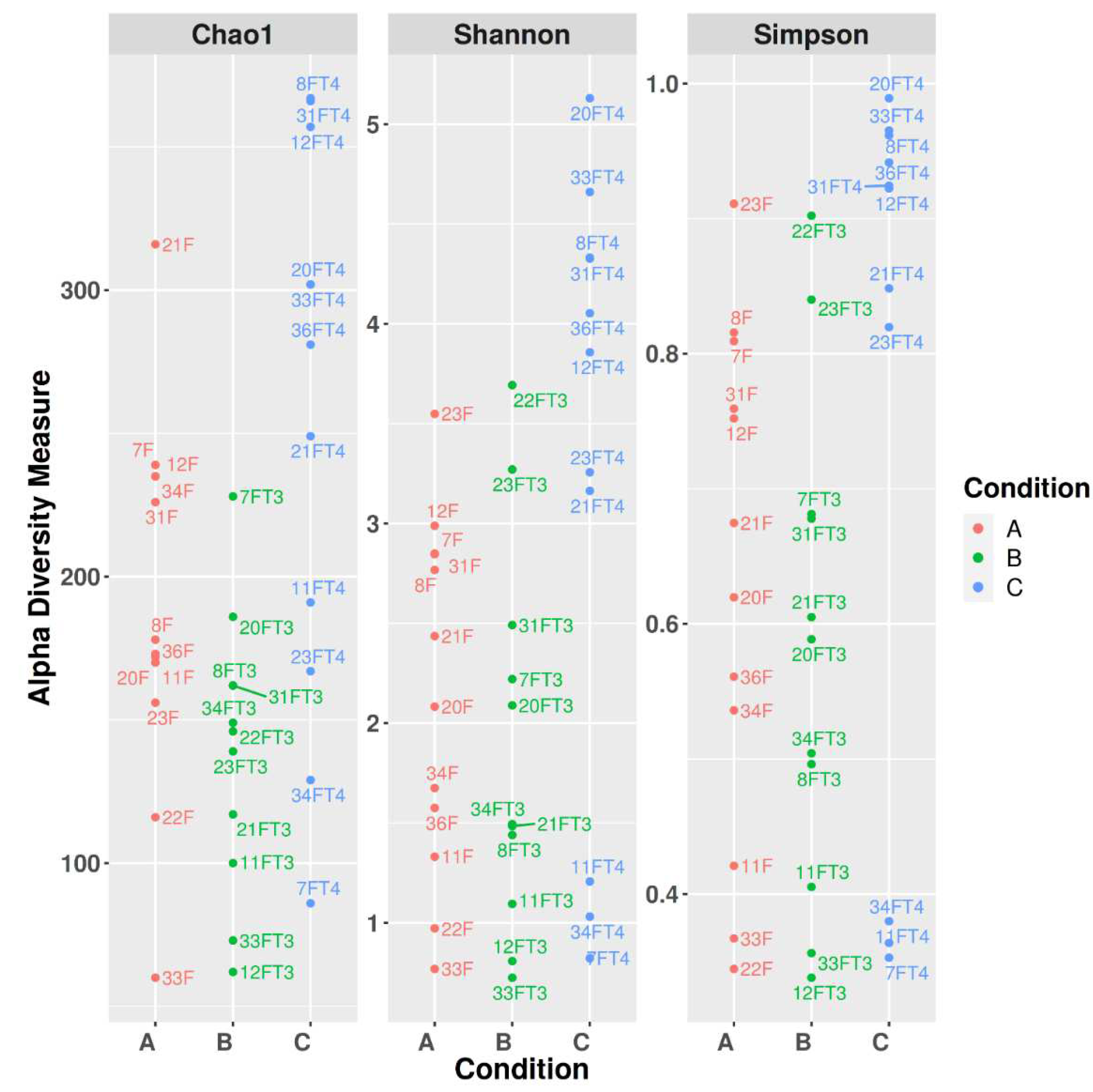

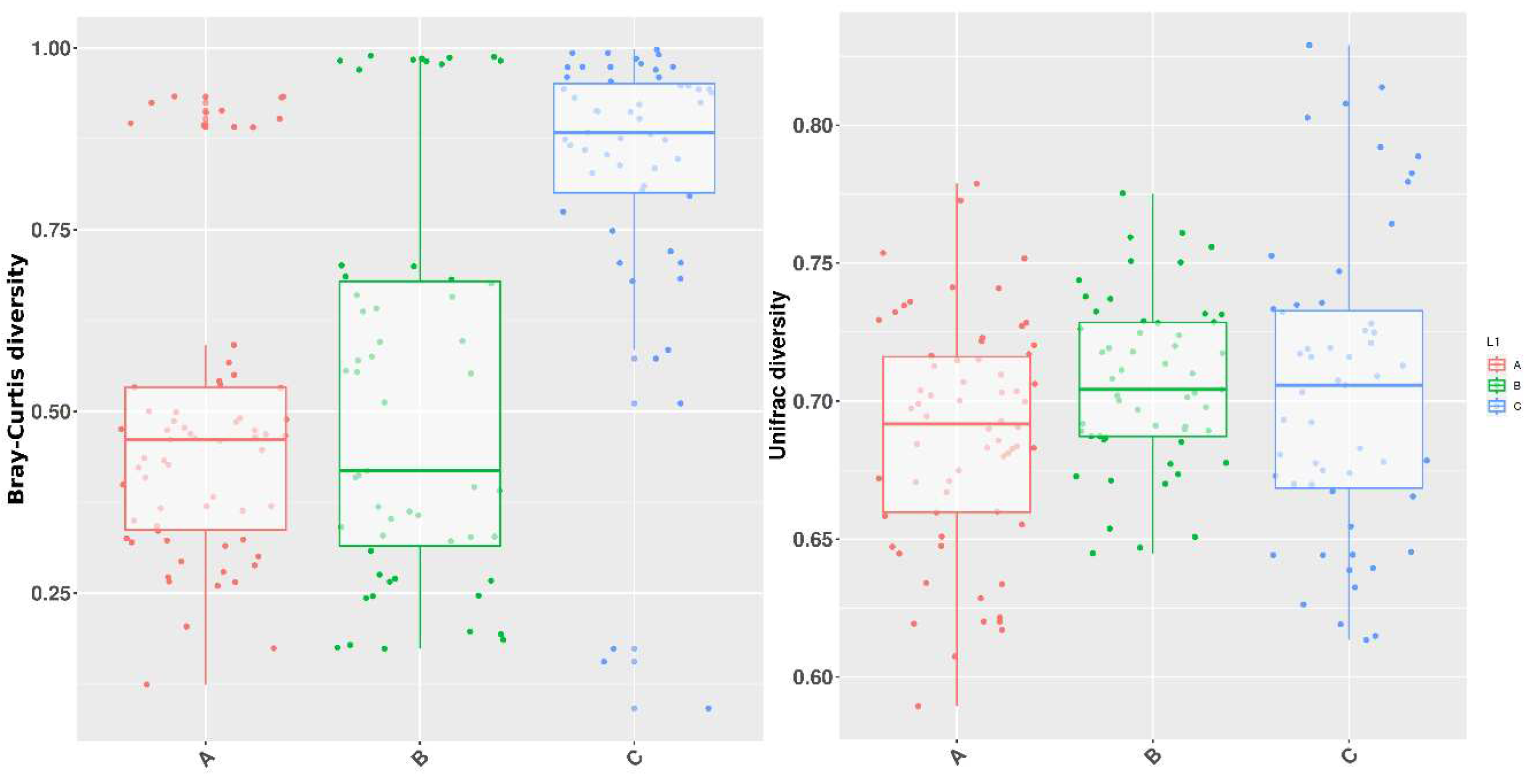

3.2. Alpha diversity

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qi, X.; Yun, C.; Pang, Y.; Qiao, J. The impact of the gut microbiota on the reproductive and metabolic endocrine system. Gut microbes 2021, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franasiak, J.M.; Scott, R.T. Introduction: microbiome in human reproduction. Fertil Steril 2015, 104, 1341–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwa, W.T.; Sundarajoo, S.; Toh, K.Y.; Lee, J. Application of emerging technologies for gut microbiome research. Singapore med j 2023, 64, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, E.; Bushnell, B.; Coleman-Derr, D.; Bowman, B.; Bowers, R. M.; Levy, A.; Gies, E.A.; Cheng, J.F.; Copeland, A.; Klenk, H.P.; Hallam, S.J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tringe, S.G.; Woyke, T. High-resolution phylogenetic microbial community profiling. ISME J 2016, 10, 2020–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.L.; Garcia-Reyero, N.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Tubbs, C.W.; Bisesi, J.H. Jr. Regulation of endocrine systems by the microbiome: Perspectives from comparative animal models. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2020, 292, 113437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góngora, E.; Elliott, K.H.; Whyte, L. Gut microbiome is affected by inter-sexual and inter-seasonal variation in diet for thick-billed murres (Uria lomvia). Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Chen, J.; Liu, K.; Tang, M.; Yang, Y. The avian gut microbiota: Diversity, influencing factors, and future directions. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 934272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, D.; Qi, G.H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.J.; Qiu, K.; Wu, S.G. Intestinal microbiota of layer hens and its association with egg quality and safety. Poult sci 2022, 101, 102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.; Wan, Q.H.; Fang, S.G. Gut microbiota of endangered crested ibis: Establishment, diversity, and association with reproductive output. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0250075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaiz-Villena, A.; Areces, C.; Ruiz-Del-Valle, V. El origen de los canarios. Revta Ornitol Práct 2012, 53, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Boseret, G.; Losson, B.; Mainil, J.G.; Thiry, E.; Saegerman, C. Zoonoses in pet birds: review and perspectives. Vet Res 2013, 44, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingfield, J.C. Organization of vertebrate annual cycles: implications for control mechanisms. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2008, 363, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Francesco, C.E.; Todisco, G.; Montani, A.; Profeta, F.; Di Provvido, A.; Foschi, G.; Persiani, T.; Marsilio, F. Reproductive disorders in domestic canaries (Serinus canarius domesticus): a retrospective study on bacterial isolates and their antimicrobial resistance in Italy from 2009 to 2012. Vet Ital 2018, 54, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.B. Topics in Medicine and Surgery. Avian Reproductive Disorders. J Exot Pet Med 2012, 21, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mazcorro, J.F.; Castillo-Carranza, S.A.; Guard, B.; Gomez-Vazquez, J.P.; Dowd, S.E.; Brigthsmith, D.J. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Bacterial Communities in Feces of Pet Birds Using 16S Marker Sequencing. Microb Ecol 2017, 73, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robino, P.; Ferrocino, I.; Rossi, G.; Dogliero, A.; Alessandria, V.; Grosso, L.; Galosi, L.; Tramuta, C.; Cocolin, L.; Nebbia, P. Changes in gut bacterial communities in canaries infected by Macrorhabdus ornithogaster. Avian Pathol 2019, 48, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; Bai, Y.; Bisanz, J.E.; Bittinger, K.; Brejnrod, A.; Brislawn, C.J.; Brown, C.T.; Callahan, B.J.; Caraballo-Rodríguez, A.M.; Chase, J.; Cope, E.K.; Da Silva, R.; Diener, C.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Douglas, G.M.; Durall, D.M.; Duvallet, C.; Edwardson, C.F.; Ernst, M.; Estaki, M.; Fouquier, J.; Gauglitz, J.M.; Gibbons, S.M.; Gibson, D.L.; Gonzalez, A.; Gorlick, K.; Guo, J.; Hillmann, B.; Holmes, S.; Holste, H.; Huttenhower, C.; Huttley, G.A.; Janssen, S.; Jarmusch, A.K.; Jiang, L.; Kaehler, B.D.; Kang, K.B.; Keefe, C.R.; Keim, P.; Kelley, S.T.; Knights, D.; Koester, I.; Kosciolek, T.; Kreps, J.; Langille, M.G.I.; Lee, J.; Ley, R.; Liu, Y.X.; Loftfield, E.; Lozupone, C.; Maher, M.; Marotz, C.; Martin, B.D.; McDonald, D.; McIver, L.J.; Melnik, A.V.; Metcalf, J.L.; Morgan, S.C.; Morton, J.T.; Naimey, A.T.; Navas-Molina, J.A.; Nothias, L.F.; Orchanian, S.B.; Pearson, T.; Peoples, S.L.; Petras, D.; Preuss, M.L.; Pruesse, E.; Rasmussen, L.B.; Rivers, A.; Robeson, M.S.; Rosenthal, P.; Segata, N.; Shaffer, M.; Shiffer, A.; Sinha, R.; Song, S.J.; Spear, J.R.; Swafford, A.D.; Thompson, L.R.; Torres, P.J.; Trinh, P.; Tripathi, A.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ul-Hasan, S.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; Vargas, F.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Vogtmann, E.; von Hippel, M.; Walters, W.; Wan, Y.; Wang, M.; Warren, J.; Weber, K.C.; Williamson, C.H.D.; Willis, A.D.; Xu, Z.Z.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Knight, R.; Caporaso, J.G. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K.; Misawa, K.; Kuma, K.; Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic acids res 2002, 30, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Species Richness: Estimation and Comparison. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; Balakrishnan, N., Colton, T., Everitt, B., Piegorsch, W., Ruggeri, F., Teugels, J.L. Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester.

- UK, 2016; pp. 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Faith, D.P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol Cons 1992, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielou, E.C. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. J Theor Biol 1966, 13, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst tech j 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of Diversity. Nature 1949, 163, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Hamady, M.; Kelley, S.T.; Knight, R. Quantitative and qualitative beta diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007, 73, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozupone, C.; Knight, R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005, 71, 8228–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J.T. An ordination of upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol Monogr 1957, 27, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, P. The Distribution of the Flora in the Alpine Zone. New Phytol 1912, 11, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruesse, E.; Quast, C.; Knittel, K.; Fuchs, B.M.; Ludwig, W.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. SILVA: A Comprehensive Online Resource for Quality Checked and Aligned Ribosomal RNA Sequence Data Compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, 7188–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, D590–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2021. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ accessed on 7th August 2023.

- Anderson, M.J. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). In: Wiley statsref: statistics reference online; Balakrishnan, N., Colton, T., Everitt, B., Piegorsch, W., Ruggeri, F., Teugels, J.L. Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester,.

- UK, 2017; pp. 1–15.

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O'Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; Watanabe, K.; Wuyts, S.; Felis, G.E.; Gänzle, M.G.; Lebeer, S. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, U.; Zastrow, M.L. Metallobiology of Lactobacillaceae in the gut microbiome. J Inorg Biochem 2023, 238, 112023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin Bukhari, S.; Ahmed Alghamdi, H.; Ur Rehman, K.; Andleeb, S.; Ahmad, S.; Khalid, N. Metagenomics analysis of the fecal microbiota in Ring-necked pheasants (Phasianus colchicus) and Green pheasants (Phasianus versicolor) using next generation sequencing. Saudi J Biol Sci 2022, 29, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cesare, A.; Sirri, F.; Manfreda, G.; Moniaci, P.; Giardini, A.; Zampiga, M.; Meluzzi, A. Effect of dietary supplementation with Lactobacillus acidophilus D2/CSL (CECT 4529) on caecum microbioma and productive performance in broiler chickens. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0176309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, A.F.; Teitelbaum, D.H.; Drongowski, R.A.; Yongyi, F.; Harmon, C.M.; Coran, A.G. Probiotics up-regulate MUC-2 mucin gene expression in a Caco-2 cell-culture model. Pediatr surg int 2002, 18, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Whang, K.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Oh, S. Inhibition of Escherichia coli O157:H7 attachment by interactions between lactic acid bacteria and intestinal epithelial cells. J microbiol biotechnol 2008, 18, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Hong, Y.; Jiang, K.; Yu, L.; Xie, X.; Mi, Y.; Zhu, S.J.; Zhang, C.; Li, J. Transplantion of predominant Lactobacilli from native hens to commercial hens could indirectly regulate their ISC activity by improving intestinal microbiota. Microb biotechnol 2022, 15, 1235–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J. Ecological role of lactobacilli in the gastrointestinal tract: implications for fundamental and biomedical research. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008, 74, 4985–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, A. Avian Molting. In Sturkie's Avian Physiology, 6th ed.; Scanes, C.G., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA (US), 2015; pp. 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vézina, F.; Gustowska, A.; Jalvingh, K.M.; Chastel, O.; Piersma, T. Hormonal correlates and thermoregulatory consequences of molting on metabolic rate in a northerly wintering shorebird. Physiol Biochem Zool 2009, 82, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzel, W.J. Neurobiology of molt in avian species. Poult Sci 2003, 82, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiley, K.O. Prolactin and avian parental care: New insights and unanswered questions. Horm Behav 2019, 111, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.E. Energetics and nutrition of molt. In Avian energetics and nutritional ecology; Carey, C., Ed.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1996; pp. 158–198. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.; Lee, W.Y. Interspecific comparison of the fecal microbiota structure in three Arctic migratory bird species. Ecol Evol 2020, 10, 5582–5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewar, M.L.; Arnould, J.P.; Krause, L.; Trathan, P.; Dann, P.; Smith, S.C. Influence of fasting during moult on the faecal microbiota of penguins. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e99996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, M.U.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; Hassan, F.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Khafaga, A.F.; Batiha, G.E.; Yehia, N.; Elnesr, S.S.; Alagawany, M.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; Wang, M. The potential mechanistic insights and future implications for the effect of prebiotics on poultry performance, gut microbiome, and intestinal morphology. Poult Sci 2021, 100, 101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutteel, P. Veterinary aspects of breeding management in captive passerines. Semin avian exot pet med 2003, 12, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, O.F.A.; Claassen, E. The mechanistic link between health and gut microbiota diversity. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offret, C.; Paulino, S.; Gauthier, O.; Château, K.; Bidault, A.; Corporeau, C.; Miner, P.; Petton, B.; Pernet, F.; Fabioux, C.; Paillard, C.; Blay, G.L. The marine intertidal zone shapes oyster and clam digestive bacterial microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2020, 96, fiaa078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Gao, H.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, H.; Chen, Z.; Dong, B. Seasonal dynamics and starvation impact on the gut microbiome of urochordate ascidian Halocynthia roretzi. Anim Microbiome 2020, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graells, T.; Ishak, H.; Larsson, M.; Guy, L. The all-intracellular order Legionellales is unexpectedly diverse, globally distributed and lowly abundant. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2018, 94, fiy185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Peng, X.; Du, T.; Xia, Z.; Gao, Q.; Tang, Q.; Yi, S.; Yang, G. Alterations of the Gut Microbiota and Metabolomics Associated with the Different Growth Performances of Macrobrachium rosenbergii Families. Animals, 2023, 13, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis, B.A.; Bell, T.H.; Engler, H.I.; King, W.L. Shared and unique responses in the microbiome of allopatric lizards reared in a standardized environment. J Exp Zool A: Ecol Integr Physiol, 2023, 339, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M.P.V.; Guimarães, M.B.; Davies, Y.M.; Milanelo, L.; Knöbl, T. Bactérias gram-negativas em cardeais (Paroaria coronata e Paroaria dominicana) apreendidos do tráfico de animais silvestres. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci 2016, 53, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Y.M.; Guimarães, M.B.; Milanelo, L.; Oliveira, M.G.X.; de Gomes, V.T. de M.; Azevedo, N.P.; Cunha, M.P.V.; Moreno, L.Z.; Romero, D.C.; Christ, A.P.G.; Sato, M.I.Z.; Moreno, A.M.; Ferreira, A.J.P.; Sá, L.R.M.; Knöbl, T. A survey on gram-negative bacteria in saffron finches (Sicalis flaveola) from illegal wildlife trade in Brazil. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci 2016, 53, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Y.M.; Franco, L.S.; Barbosa, F.B.; Vanin, C.L.; Gomes, V.T.M.; Moreno, L.Z.; Barbosa, M.R.F.; Sato, M.I.Z.; Moreno, A.M.; Knöbl, T. Use of MALDI-TOF for identification and surveillance of gram-negative bacteria in captive wild psittacines. Braz J Biol 2021, 82, e233523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, J.L. Genus XXIX. Proteus, In Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed.; Brenner, D.J., Krieg, N.R., Staley, J.T., Garrity, G.M., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA (US), 2005; Volume 2, pp. 745–753. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. , Wang, A., Yang, Y., Wang, F., Liu, Y., Zhang, Y., Sharshov, K., Gui, L. Composition, diversity and function of gastrointestinal microbiota in wild red-billed choughs (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax). Int microbiol 2019, 22, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escallón, C.; Belden, L.K.; Moore, I.T. The Cloacal Microbiome Changes with the Breeding Season in a Wild Bird. Integr Org Biol 2019, 1, oby009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, J.; Hucul, C.; Reasor, E.; Smith, T.; McGlothlin, J.W.; Haak, D.C.; Belden, L.K.; Moore, I.T. Assessing age, breeding stage, and mating activity as drivers of variation in the reproductive microbiome of female tree swallows. Ecol Evol 2021, 11, 11398–11413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, L.; Molinari, R.; Farinon, B.; Merendino, N. Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on the Gut Microbiota. Int J Mol Sci. 2017, 18, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Su, W.; Rahat-Rozenbloom, S.; Wolever, T.M.; Comelli, E.M. Adiposity, gut microbiota and faecal short chain fatty acids are linked in adult humans. Nutr Diabetes 2014, 4, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geier, M.S.; Torok, V.A.; Allison, G.E.; Ophel-Keller, K.; Gibson, R.A.; Munday, C.; Hughes, R.J. Dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid does not influence the intestinal microbial communities of broiler chickens. Poult sci 2009, 88, 2399–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouhy, F.; Deane, J.; Rea, M.C.; O'Sullivan, Ó.; Ross, R.P.; O'Callaghan, G.; Plant, B.J.; Stanton, C. The effects of freezing on faecal microbiota as determined using MiSeq sequencing and culture-based investigations. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Jin, G.; Wang, G.; Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, B.; Cao, H. Current Sampling Methods for Gut Microbiota: A Call for More Precise Devices. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadley, T.L. Disorders of the psittacine gastrointestinal tract. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract 2005, 8, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Groups | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive phase | Parental care | Molting | Rest |

| N. of samples | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| A vs B | A vs C | B vs C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pielou’s Evenness | 0.622461 | 0.048900 | 0.122800 |

| Faith phylogenetic diversity | 0.026716 | 0.218355 | 0.009493 |

| Observed Features | 0.022741 | 0.056219 | 0.009453 |

| Shannon | 0.423656 | 0.042254 | 0.045201 |

| A vs B | A vs C | B vs C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bray-Curtis dissimilarity | 0.863137 | 0.002997 | 0.011988 |

| UnWeighted Unifrac | 0.001998 | 0.005994 | 0.003996 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).