Submitted:

02 August 2023

Posted:

04 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

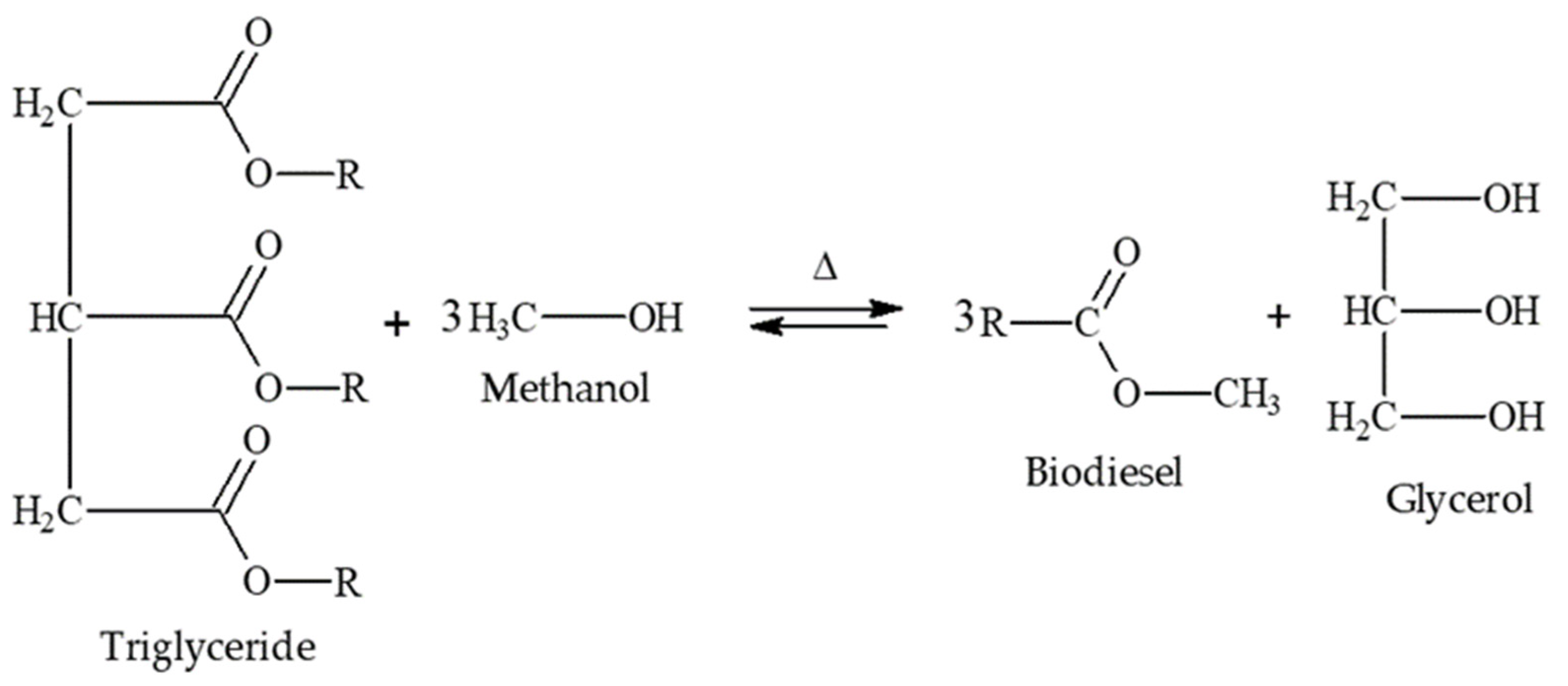

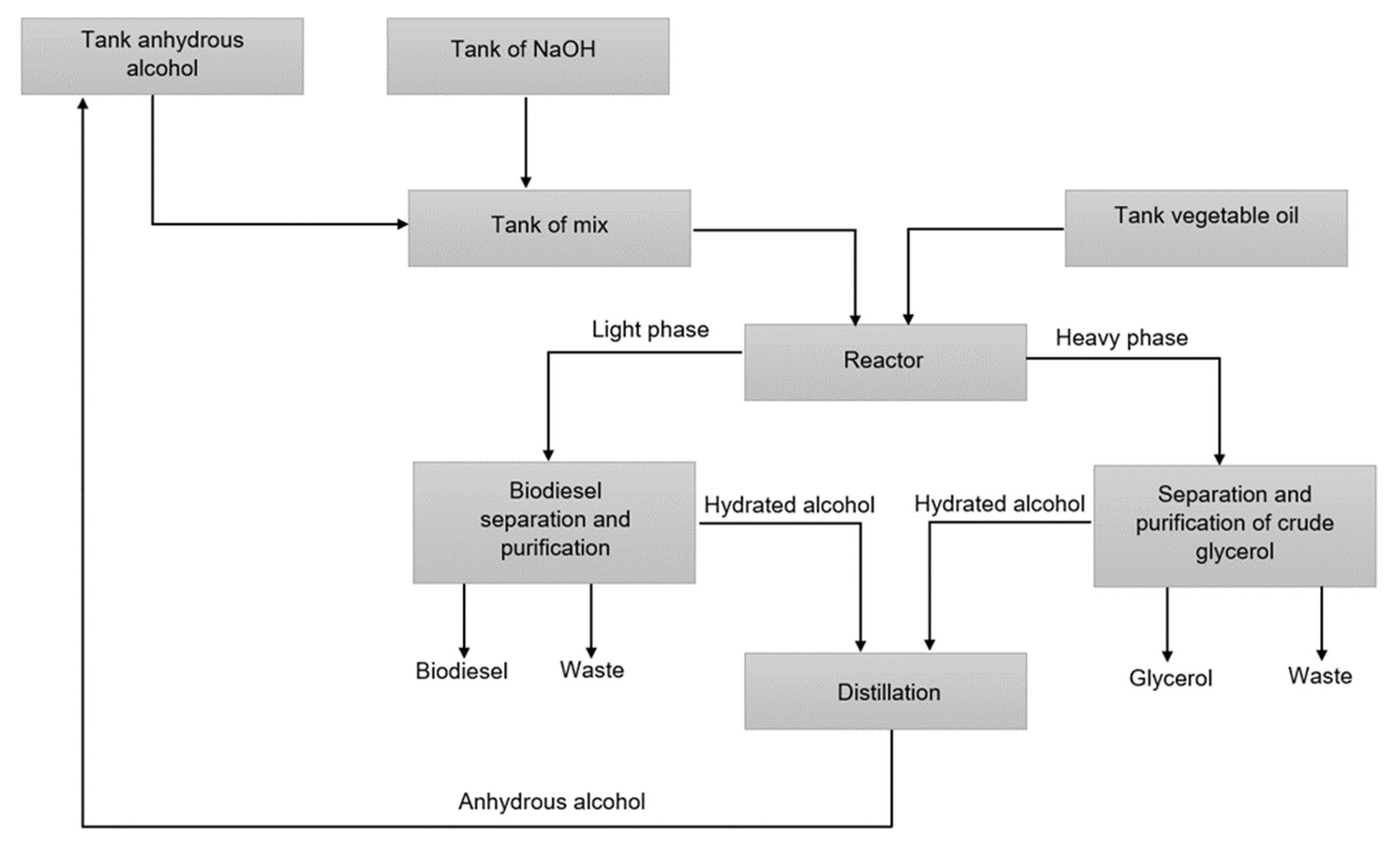

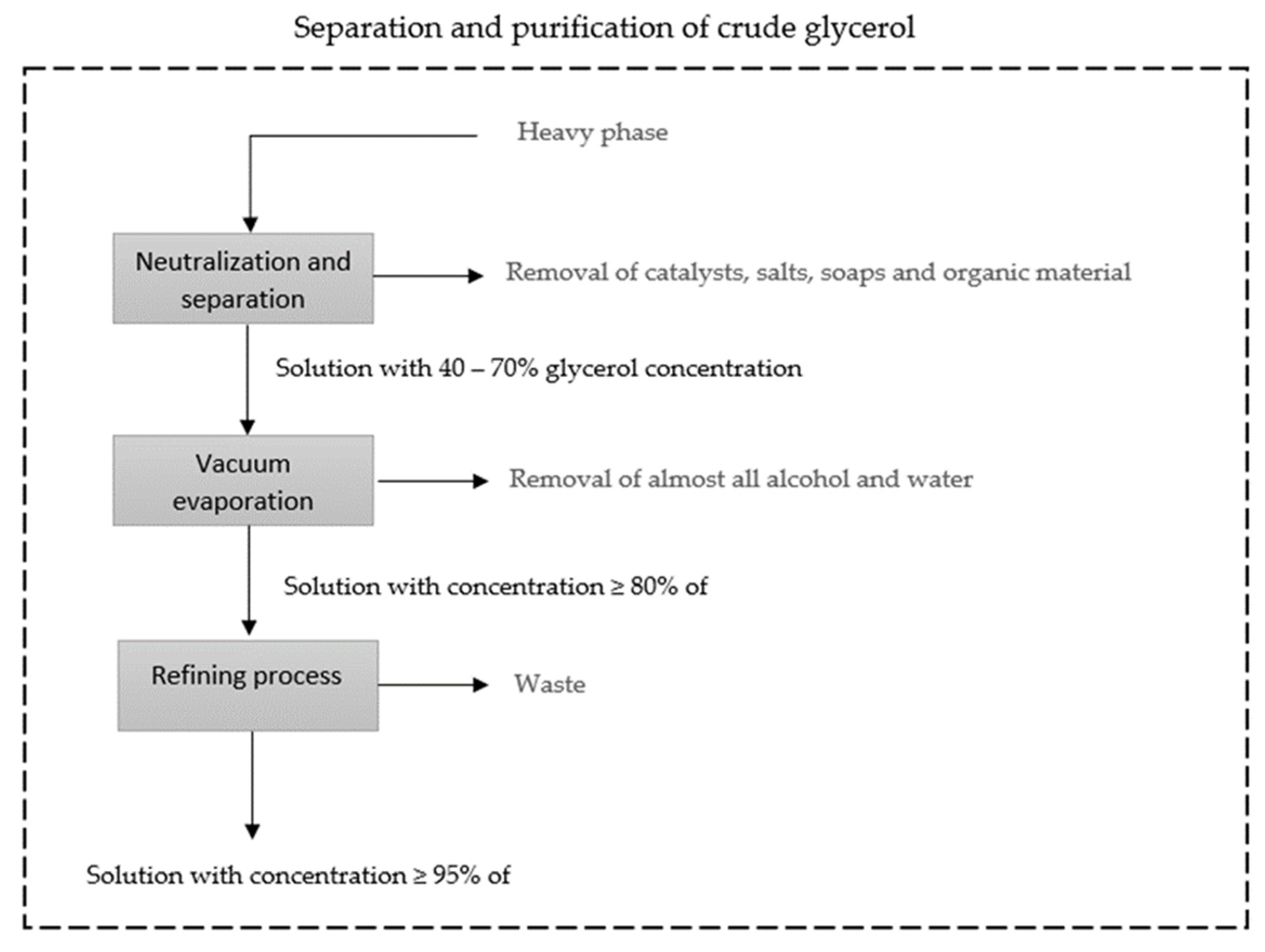

2. Glycerol

3. Biofuel production processes using glycerol as biomass

3.1. Biogas

3.2. Hydrogen

| Authors | Feedstock | Microorganism | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maru et al. (2016) | Pure glycerol and crude glycerol | Escherichia coli CECT432, Escherichia coli CECT434 e Enterobacter cloacae MCM2/1 | Co-culture of Escherichia coli CECT 432 and Enterobacter cloacae yields 1.26 mol H2/mol residual glycerol |

| Sittijunda e Reungsang (2020) | Pure glycerol and crude glycerol | Enterobacter sp., Klebsiella sp. e Klebsiella pneumoniae | The yield of hydrogen was 2.90 mol H2/mol pure glycerol and 2.05 mol H2/mol residual glycerol |

| Prakash et al. (2018) | Domestic wastewater and waste glycerol | Bacillus thuringiensis EGU4 e Bacillus amyloliquefaciens cepa CD16 | The hydrogen yield with Bacillus thuringiensis EGU4 was 100 L H2/L of residual glycerol and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain CD16 was 120 L H2/L |

| Chen et al. (2021) | Gycerol | Clostridium sp. | The yield of hydrogen 0.52 mol H2/mol glycerol for immobilized microorganisms and 0.29 mol H2/mol glycerol for suspended microorganisms |

| Silva et al. (2020) | Gycerol l | Enterobacter e Clostridium | The hydrogen yield for Enterobacter 0.25 mol H2/mol glycerol and Clostridium 0.01 mol H2/mol glycerol |

| Mirzoyan et al. (2019) | Lactose e glicerol | Escherichia coli | High H2 yield can be achieved during fermentation of 1 g/L lactose at pH 7.5 with H2 production rate of 21.94 mL/L |

| Toledo-Alarcon et al. (2020) | Glycerol | Clostridium sp. | The presented results allow a better understanding of the production of H2 in continuous systems, and provide informationfor future industrial applications |

3.3. Ethanol

| Authors | Feedstock | Microorganism | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunarno et al. (2019) | Crude glycerol | Enterobacter aerogenes | With 20 g/L of crude glycerol, and the pH maintained at 7, the ethanol production was 12.33 g/L |

| Oh et al. (2011) | Crude glycerol | Klebsiella pneumoniae GEM167 | The maximum production level was 21.5 g/L, with a productivity of 0.93 g/L/h |

| Stepanov e Efremenko (2017) | Glycerol | Pachysolen tannophilus | The conversion of glycerol into ethanol, using immobilized yeast, resulted in a yield of 90% in relation to the theoretical limit |

| Sunarno et al. (2020) | Crude glycerol | Enterobacter aerogenes TISTR1468 | In the fermentation process without aeration, the ethanol yield was 18.78 g/L, with aeration in continuous process it was 30.31 g/L and batch was 12.33 g/L |

| Suzuki et al. (2015) | Glycerol | Klebsiella variicola TB-83 e TB-83D | The strain TB-83D is effective for the production of ethanol from glycerol, and this strain is a mutant of Klebsiella variicola TB-83 |

| Vikromvarasiri et al. (2016) | Crude glycerol and waste water | Enterobacter e Klebsiella | The highest concentration of ethanol was 11.1 g/L obtained after 72 h of fermentation at an initial concentration of 45 g/L of glycerol |

| Lee et al. (2017) | Pure glycerol and crude glycerol | Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC 29007 imobilizado | Under optimal conditions, the ethanol production and yield were approximately 5.38 g/L and 0.96 mol-ethanol/mol-glycerol with pure glycerol, while the ethanol production and yield were approximately 5.29 g/ L and 0.91 mol ethanol/mol-glycerol with crude glycerol |

4. Considerations

5. Conclusion

References

- Ghosh, S.K. Biomass & Bio-Waste Supply Chain Sustainability for Bio-Energy and Bio-Fuel Production. Procedia Environ Sci 2016, 31, 31–39. [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, N.; Sivasankari, S.; Kiran, G.S.; Ninawe, A.; Selvin, J. Utilization of Bioresources for Sustainable Biofuels: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 73, 205–214.

- Luque, R.; Lovett, J.C.; Datta, B.; Clancy, J.; Campelo, J.M.; Romero, A.A. Biodiesel as Feasible Petrol Fuel Replacement: A Multidisciplinary Overview. Energy Environ Sci 2010, 3, 1706–1721. [CrossRef]

- Chuah, L.F.; Klemeš, J.J.; Yusup, S.; Bokhari, A.; Akbar, M.M. A Review of Cleaner Intensification Technologies in Biodiesel Production. J Clean Prod 2017, 146, 181–193. [CrossRef]

- Mamtani, K.; Shahbaz, K.; Farid, M.M. Deep Eutectic Solvents – Versatile Chemicals in Biodiesel Production. Fuel 2021, 295.

- Demirbas, A. Competitive Liquid Biofuels from Biomass. Appl Energy 2011, 88, 17–28.

- Srilatha, K.; Prabhavathi Devi, B.L.A.; Lingaiah, N.; Prasad, R.B.N.; Sai Prasad, P.S. Biodiesel Production from Used Cooking Oil by Two-Step Heterogeneous Catalyzed Process. Bioresour Technol 2012, 119, 306–311. [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.Y.C.; Wu, X.; Leung, M.K.H. A Review on Biodiesel Production Using Catalyzed Transesterification. Appl Energy 2010, 87, 1083–1095.

- Abbaszaadeh, A.; Ghobadian, B.; Omidkhah, M.R.; Najafi, G. Current Biodiesel Production Technologies: A Comparative Review. In Proceedings of the Energy Conversion and Management; November 2012; Vol. 63, pp. 138–148.

- Faruque, M.O.; Razzak, S.A.; Hossain, M.M. Application of Heterogeneous Catalysts for Biodiesel Production from Microalgal Oil—a Review. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1–25.

- Tachibana, Y.; Shi, X.; Graiver, D.; Narayan, R. The Use of Glycerol Carbonate in the Preparation of Highly Branched Siloxy Polymers. Silicon 2015, 7, 5–13. [CrossRef]

- Badia-Fabregat, M.; Rago, L.; Baeza, J.A.; Guisasola, A. Hydrogen Production from Crude Glycerol in an Alkaline Microbial Electrolysis Cell. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 17204–17213. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.J.; Shen, J.T.; Wang, X.L.; Sun, Y.Q.; Xiu, Z.L. Stability and Oscillatory Behavior of Microbial Consortium in Continuous Conversion of Crude Glycerol to 1,3-Propanediol. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 102, 8291–8305. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Kumar, N. Scope and Opportunities of Using Glycerol as an Energy Source. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 4551–4556.

- da Silva, G.P.; Mack, M.; Contiero, J. Glycerol: A Promising and Abundant Carbon Source for Industrial Microbiology. Biotechnol Adv 2009, 27, 30–39.

- Faccendini, P.L.; Ribone, M.É.; Lagier, C.M. Selective Application of Two Rapid, Low-Cost Electrochemical Methods to Quantify Glycerol According to the Sample Nature. Sens Actuators B Chem 2014, 193, 142–148. [CrossRef]

- Anitha, M.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Kofli, N.T. The Potential of Glycerol as a Value-Added Commodity. Chemical Engineering Journal 2016, 295, 119–130.

- Zhang, X.; Yan, S.; Tyagi, R.D.; Surampalli, R.Y.; Valéro, J.R. Energy Balance of Biofuel Production from Biological Conversion of Crude Glycerol. J Environ Manage 2016, 170, 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Ladero, M.; de Gracia, M.; Tamayo, J.J.; Ahumada, I.L. de; Trujillo, F.; Garcia-Ochoa, F. Kinetic Modelling of the Esterification of Rosin and Glycerol: Application to Industrial Operation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2011, 169, 319–328. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, D.B.; Carlos, J.; Serra, V. Artigo Recebido Em 21; 2011; Vol. 12;

- Haigh, K.F.; Vladisavljević, G.T.; Reynolds, J.C.; Nagy, Z.; Saha, B. Kinetics of the Pre-Treatment of Used Cooking Oil Using Novozyme 435 for Biodiesel Production. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2014, 92, 713–719. [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, F.A.; Perdomo, L.; Millán, B.M.; Aragón, J.L. Design and Improvement of Biodiesel Fuels Blends by Optimization of Their Molecular Structures and Compositions. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2014, 92, 1482–1494. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, E.L.; Andrade, C.M.G.; Andreo Dos Santos, O. Production of Biodiesel Via Catalytic Processes: A Brief Review. International Journal of Chemical Reactor Engineering 2018, 16.

- Dasari, S.R.; Borugadda, V.B.; Goud, V. V. Reactive Extraction of Castor Seeds and Storage Stability Characteristics of Produced Biodiesel. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2016, 100, 252–263. [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.R.; Goud, V. V. Simultaneous Extraction and Transesterification of Castor Seeds for Biodiesel Production: Assessment of Biodegradability. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2017, 107, 373–387. [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Sharma, M.P.; Dwivedi, G. Impact of Alcohol on Biodiesel Production and Properties. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 56, 319–333.

- Jafari, D.; Esfandyari, M. Optimization of Temperature and Molar Flow Ratios of Triglyceride/Alcohol in Biodiesel Production in a Batch Reactor. Biofuels 2020, 11, 261–267. [CrossRef]

- Moser, B.R. Biodiesel Production, Properties, and Feedstocks. In Vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology - Plant 2009, 45, 229–266.

- Tan, K.T.; Lee, K.T. A Review on Supercritical Fluids (SCF) Technology in Sustainable Biodiesel Production: Potential and Challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011, 15, 2452–2456.

- Atadashi, I.M.; Aroua, M.K.; Abdul Aziz, A.R.; Sulaiman, N.M.N. Production of Biodiesel Using High Free Fatty Acid Feedstocks. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 3275–3285.

- Bateni, H.; Karimi, K. Biodiesel Production from Castor Plant Integrating Ethanol Production via a Biorefinery Approach. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2016, 107, 4–12. [CrossRef]

- Cristina Santos de Mello, M.; Gomes D’Amato Villardi, H.; Ferreira Young, A.; Luiz Pellegrini Pessoa, F.; Medeiros Salgado, A. Life Cycle Assessment of Biodiesel Produced by the Methylic-Alkaline and Ethylic-Enzymatic Routes. Fuel 2017, 208, 329–336. [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.Y.; Lim, S.; Pang, Y.L.; Shuit, S.H.; Chen, W.H.; Lee, K.T. Synthesis of Renewable Heterogeneous Acid Catalyst from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch for Glycerol-Free Biodiesel Production. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 727. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, B.; Teixeira, J.C.; Dragone, G.; Teixeira, J.A. Oleaginous Yeasts for Sustainable Lipid Production—from Biodiesel to Surf Boards, a Wide Range of “Green” Applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2019.

- Jayakumar, M.; Karmegam, N.; Gundupalli, M.P.; Bizuneh Gebeyehu, K.; Tessema Asfaw, B.; Chang, S.W.; Ravindran, B.; Kumar Awasthi, M. Heterogeneous Base Catalysts: Synthesis and Application for Biodiesel Production – A Review. Bioresour Technol 2021, 331.

- Rastogi, R.P.; Pandey, A.; Larroche, C.; Madamwar, D. Algal Green Energy – R&D and Technological Perspectives for Biodiesel Production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 82, 2946–2969.

- Leandro Almeida, E.; Inácio Gomes, S.; Andrade, C.M.G.; Aparecida Andreo dos Santos, O. Biodiesel Production Process Versus Bioethanol Production Process. Preliminary Analysis.; Faculty of Law, University of Maribor, July 7 2017; pp. 333–342.

- Luo, X.; Ge, X.; Cui, S.; Li, Y. Value-Added Processing of Crude Glycerol into Chemicals and Polymers. Bioresour Technol 2016, 215, 144–154. [CrossRef]

- Ardi, M.S.; Aroua, M.K.; Hashim, N.A. Progress, Prospect and Challenges in Glycerol Purification Process: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 42, 1164–1173.

- Quispe, C.A.G.; Coronado, C.J.R.; Carvalho, J.A. Glycerol: Production, Consumption, Prices, Characterization and New Trends in Combustion. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2013, 27, 475–493.

- Kondaveeti, S.; Kim, I.W.; Otari, S.; Patel, S.K.S.; Pagolu, R.; Losetty, V.; Kalia, V.C.; Lee, J.K. Co-Generation of Hydrogen and Electricity from Biodiesel Process Effluents. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 27285–27296. [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, S.A.; Herrington, J.S.; Winterrowd, C.K.; Roberts, W.L.; Wendt, J.O.L.; Linak, W.P. Crude Glycerol Combustion: Particulate, Acrolein, and Other Volatile Organic Emissions. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 2013, 34, 2749–2757. [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y.; Tada, C.; Watanabe, R.; Fukuda, Y.; Chida, N.; Nakai, Y. Bioresource Technology Anaerobic Digestion of Crude Glycerol from Biodiesel Manufacturing Using a Large-Scale Pilot Plant : Methane Production and Application of Digested Sludge as Fertilizer. Bioresour Technol 2013, 140, 342–348. [CrossRef]

- Fontes, G.C.; Ramos, N.M.; Amaral, P.F.F.; Nele, M.; Coelho, M.A.Z. Renewable Resources for Biosurfactant Production by Yarrowia Lipolytica. 2012, 29, 483–493.

- Paulista, L.O.; Boaventura, R.A.R.; Vilar, V.J.P.; Pinheiro, A.L.N.; Martins, R.J.E. Enhancing Methane Yield from Crude Glycerol Anaerobic Digestion by Coupling with Ultrasound or A. Niger/E. Coli Biodegradation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 1461–1474. [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, M.S.; Manios, T. Bioresource Technology Enhanced Methane and Hydrogen Production from Municipal Solid Waste and Agro-Industrial by-Products Co-Digested with Crude Glycerol. Bioresour Technol 2009, 100, 3043–3047. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinović, S.; Danilović, B.R.; Ćirić, J.T.; Ilić, S.B.; Savić, D.S.; Veljković, V.B. Valorization of Crude Glycerol from Biodiesel Production. Chemical Industry and Chemical Engineering Quarterly 2016, 22, 461–489. [CrossRef]

- Chiodo, V.; Zafarana, G.; Maisano, S.; Freni, S.; Galvagno, A.; Urbani, F. Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell System Fed with Biofuels for Electricity Production. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 18815–18821. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.S.; Volschan, I.; Cammarota, M.C. Enhanced Biogas Production in Pilot Digesters Treating a Mixture of Sewage Sludge, Glycerol, and Food Waste. Energy and Fuels 2018, 32, 6839–6846. [CrossRef]

- Astals, S.; Nolla-Ardèvol, V.; Mata-Alvarez, J. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Pig Manure and Crude Glycerol at Mesophilic Conditions: Biogas and Digestate. Bioresour Technol 2012, 110, 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Siles, J.A.; Martín, M.A.; Chica, A.F.; Martín, A. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Glycerol and Wastewater Derived from Biodiesel Manufacturing. Bioresour Technol 2010, 101, 6315–6321. [CrossRef]

- Beschkov, V.; Sapundzhiev, T.; Angelov, I. Modelling of Biogas Production from Glycerol by Anaerobic Process in a Baffled Multi-Stage Digestor. Biotechnology and Biotechnological Equipment 2012, 26, 3244–3248. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J. V.; Alves, M.M.; Costa, J.C. Optimization of Biogas Production from Sargassum Sp. Using a Design of Experiments to Assess the Co-Digestion with Glycerol and Waste Frying Oil. Bioresour Technol 2015, 175, 480–485. [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.C.; Su, J.J. Biogas Production by Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Dairy Wastewater with the Crude Glycerol from Slaughterhouse Sludge Cake Transesterification. Animals 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Sawasdee, V.; Haosagul, S.; Pisutpaisal, N. Co-Digestion of Waste Glycerol and Glucose to Enhance Biogas Production. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 29575–29582. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, S.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, C.; Zhou, S.; Qiu, Y.; Luo, S.; Jing, F.; et al. Glycerol Steam Reforming for Hydrogen Production over Bimetallic MNi/CNTs (M[Dbnd]Co, Cu and Fe) Catalysts. Catal Today 2020, 355, 128–138. [CrossRef]

- Cortright, R.D.; Davda, R.R.; Dumesic, J.A. Hydrogen from Catalytic Reforming of Biomass-Derived Hydrocarbons in Liquid Water. Nature 2002, 418, 964–967. [CrossRef]

- Kondratenko, E. V.; Mul, G.; Baltrusaitis, J.; Larrazábal, G.O.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Status and Perspectives of CO2 Conversion into Fuels and Chemicals by Catalytic, Photocatalytic and Electrocatalytic Processes. Energy Environ Sci 2013, 6, 3112–3135.

- Sarma, S.; Ortega, D.; Minton, N.P.; Dubey, V.K.; Moholkar, V.S. Homologous Overexpression of Hydrogenase and Glycerol Dehydrogenase in Clostridium Pasteurianum to Enhance Hydrogen Production from Crude Glycerol. Bioresour Technol 2019, 284, 168–177. [CrossRef]

- Varella Rodrigues, C.; Oliveira Santana, K.; Nespeca, M.G.; Varella Rodrigues, A.; Oliveira Pires, L.; Maintinguer, S.I. Energy Valorization of Crude Glycerol and Sanitary Sewage in Hydrogen Generation by Biological Processes. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 11943–11953. [CrossRef]

- Maru, B.T.; López, F.; Kengen, S.W.M.; Constantí, M.; Medina, F. Dark Fermentative Hydrogen and Ethanol Production from Biodiesel Waste Glycerol Using a Co-Culture of Escherichia Coli and Enterobacter Sp. Fuel 2016, 186, 375–384. [CrossRef]

- Sittijunda, S.; Reungsang, A. Valorization of Crude Glycerol into Hydrogen, 1,3-Propanediol, and Ethanol in an up-Flow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket (UASB) Reactor under Thermophilic Conditions. Renew Energy 2020, 161, 361–372. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, J.; Sharma, R.; Patel, S.K.S.; Kim, I.W.; Kalia, V.C. Bio-Hydrogen Production by Co-Digestion of Domestic Wastewater and Biodiesel Industry Effluent. PLoS One 2018, 13. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, J. Comparison of Fermentative Hydrogen Production from Glycerol Using Immobilized and Suspended Mixed Cultures. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 8986–8994. [CrossRef]

- Cristina, M.; Silva, A.; Monteggia, L.O. Hydrogen Production Potential Comparison of Sucrose and Crude Glycerol Using Different Inoculums Sources; 2020; Vol. 25;

- Mirzoyan, S.; Trchounian, A.; Trchounian, K. Hydrogen Production by Escherichia Coli during Anaerobic Utilization of Mixture of Lactose and Glycerol: Enhanced Rate and Yield, Prolonged Production. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 9272–9281. [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Alarcón, J.; Cabrol, L.; Jeison, D.; Trably, E.; Steyer, J.P.; Tapia-Venegas, E. Impact of the Microbial Inoculum Source on Pre-Treatment Efficiency for Fermentative H2 Production from Glycerol. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 1597–1607. [CrossRef]

- Cardona, C.A.; Sánchez, Ó.J. Fuel Ethanol Production: Process Design Trends and Integration Opportunities. Bioresour Technol 2007, 98, 2415–2457.

- Ganguly, A.; Chatterjee, P.K.; Dey, A. Studies on Ethanol Production from Water Hyacinth - A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 966–972.

- Yazdani, S.S.; Gonzalez, R. Anaerobic Fermentation of Glycerol: A Path to Economic Viability for the Biofuels Industry. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2007, 18, 213–219.

- Yu, K.O.; Kim, S.W.; Han, S.O. Engineering of Glycerol Utilization Pathway for Ethanol Production by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Bioresour Technol 2010, 101, 4157–4161. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Yoo, H.Y.; Lee, S.K.; Chun, Y.; Kim, H.R.; Bankeeree, W.; Lotrakul, P.; Punnapayak, H.; Prasongsuk, S.; Kim, S.W. Significant Impact of Casein Hydrolysate to Overcome the Low Consumption of Glycerol by Klebsiella Aerogenes ATCC 29007 and Its Application to Bioethanol Production. Energy Convers Manag 2020, 221. [CrossRef]

- Sunarno, J.N.; Prasertsan, P.; Duangsuwan, W.; Cheirsilp, B.; Sangkharak, K. Biodiesel Derived Crude Glycerol and Tuna Condensate as an Alternative Low-Cost Fermentation Medium for Ethanol Production by Enterobacter Aerogenes. Ind Crops Prod 2019, 138. [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.K.; Hwang, K.R.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.R.; Lee, J.S. Recent Developments and Key Barriers to Advanced Biofuels: A Short Review. Bioresour Technol 2018, 257, 320–333. [CrossRef]

- Stepanov, N.; Efremenko, E. Immobilised Cells of Pachysolen Tannophilus Yeast for Ethanol Production from Crude Glycerol. N Biotechnol 2017, 34, 54–58. [CrossRef]

- Sunarno, J.N.; Prasertsan, P.; Duangsuwan, W.; Cheirsilp, B.; Sangkharak, K. Improve Biotransformation of Crude Glycerol to Ethanol of Enterobacter Aerogenes by Two-Stage Redox Potential Fed-Batch Process under Microaerobic Environment. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 134. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Seta, K.; Nishikawa, C.; Hara, E.; Shigeno, T.; Nakajima-Kambe, T. Improved Ethanol Tolerance and Ethanol Production from Glycerol in a Streptomycin-Resistant Klebsiella Variicola Mutant Obtained by Ribosome Engineering. Bioresour Technol 2015, 176, 156–162. [CrossRef]

- Vikromvarasiri, N.; Haosagul, S.; Boonyawanich, S.; Pisutpaisal, N. Microbial Dynamics in Ethanol Fermentation from Glycerol. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 15667–15673. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Lee, J.H.; Yang, X.; Yoo, H.Y.; Han, S.O.; Park, C.; Kim, S.W. Re-Utilization of Waste Glycerol for Continuous Production of Bioethanol by Immobilized Enterobacter Aerogenes. J Clean Prod 2017, 161, 757–764. [CrossRef]

- Pereyra, D. de L.A.D.; Rueger, I.B.; Barbosa, P.A.M. de A.; Peiter, F.S.; da Silva Freitas, D.M.; de Amorim, E.L.C. Co-Fermentation of Glycerol and Molasses for Obtaining Biofuels and Value-Added Products. Brazilian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2020, 37, 653–660. [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Manzardo, A.; Mazzi, A.; Fedele, A.; Scipioni, A. Emergy Analysis and Sustainability Efficiency Analysis of Different Crop-Based Biodiesel in Life Cycle Perspective. The Scientific World Journal 2013, 2013.

- Viana, M.B.; Freitas, A. V.; Leitão, R.C.; Pinto, G.A.S.; Santaella, S.T. Anaerobic Digestion of Crude Glycerol: A Review. Environmental Technology Reviews 2012, 1, 81–92. [CrossRef]

- Quispe, C.A.G.; Coronado, C.J.R.; Carvalho, J.A. Glycerol: Production, Consumption, Prices, Characterization and New Trends in Combustion. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2013, 27, 475–493.

- Bułkowska, K.; Białobrzewski, I.; Klimiuk, E.; Pokój, T. Kinetic Parameters of Volatile Fatty Acids Uptake in the ADM1 as Key Factors for Modeling Co-Digestion of Silages with Pig Manure, Thin Stillage and Glycerine Phase. Renew Energy 2018, 126, 163–176. [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.; Ghosh, P.; Tyagi, B.; Vijay, V.K.; Vijay, V.; Thakur, I.S.; Kamyab, H.; Nguyen, D.D.; Kumar, A. Advances in Biogas Valorization and Utilization Systems: A Comprehensive Review. J Clean Prod 2020, 273. [CrossRef]

- Kurahashi, K.; Kimura, C.; Fujimoto, Y.; Tokumoto, H. Value-Adding Conversion and Volume Reduction of Sewage Sludge by Anaerobic Co-Digestion with Crude Glycerol. Bioresour Technol 2017, 232, 119–125. [CrossRef]

- Vivek, N.; Pandey, A.; Binod, P. Biological Valorization of Pure and Crude Glycerol into 1,3-Propanediol Using a Novel Isolate Lactobacillus Brevis N1E9.3.3. Bioresour Technol 2016, 213, 222–230. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.E.; Rehmann, L. The Role of 1,3-Propanediol Production in Fermentation of Glycerol by Clostridium Pasteurianum. Bioresour Technol 2016, 209, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Poladyan, A.; Baghdasaryan, L.; Trchounian, A. Escherichia Coli Wild Type and Hydrogenase Mutant Cells Growth and Hydrogen Production upon Xylose and Glycerol Co-Fermentation in Media with Different Buffer Capacities. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 15870–15879. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.L.A.; Bracher, J.M.; Papapetridis, I.; Verhoeven, M.D.; De Bruijn, H.; De Waal, P.P.; Van Maris, A.J.A.; Klaassen, P.; Pronk, J.T. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Strains for Second-Generation Ethanol Production: From Academic Exploration to Industrial Implementation.

- Mohsenzadeh, A.; Zamani, A.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Bioethylene Production from Ethanol: A Review and Techno-Economical Evaluation. ChemBioEng Reviews 2017, 4, 75–91.

- Bateni, H.; Karimi, K. Biodiesel Production from Castor Plant Integrating Ethanol Production via a Biorefinery Approach. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2016, 107, 4–12. [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.O.; Kim, S.W.; Han, S.O. Reduction of Glycerol Production to Improve Ethanol Yield in an Engineered Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Using Glycerol as a Substrate. J Biotechnol 2010, 150, 209–214. [CrossRef]

- Farobie, O.; Sasanami, K.; Matsumura, Y. A Novel Spiral Reactor for Biodiesel Production in Supercritical Ethanol. Appl Energy 2015, 147, 20–29. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.S.; Mardina, P.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.Y.; Kalia, V.C.; Kim, I.W.; Lee, J.K. Improvement in Methanol Production by Regulating the Composition of Synthetic Gas Mixture and Raw Biogas. Bioresour Technol 2016, 218, 202–208. [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, A.; Melegari De Souza, S.N.; Divino De Lima Afonso, A.; Ricieri, R.P. Confecção e Avaliação de Um Sistema de Remoção Do CO 2 Contido No Biogás; 2004; Vol. 26;

- Bozzano, G.; Manenti, F. Efficient Methanol Synthesis: Perspectives, Technologies and Optimization Strategies. Prog Energy Combust Sci 2016, 56, 71–105.

- Su, Z.; Ge, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, L.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y. Methanol Production from Biogas with a Thermotolerant Methanotrophic Consortium Isolated from an Anaerobic Digestion System. Energy and Fuels 2017, 31, 2970–2975. [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, A.; Mirvakili, A.; Chahibakhsh, S.; Shariati, A.; Rahimpour, M.R. Simultaneous Methanol Production and Separation in the Methanol Synthesis Reactor to Increase Methanol Production. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification 2020, 158. [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Zahedi, G.; Klemeš, J.J. A Review of Cleaner Production Methods for the Manufacture of Methanol. J Clean Prod 2013, 57, 19–37. [CrossRef]

- Sittijunda, S.; Reungsang, A. Methane Production from the Co-Digestion of Algal Biomass with Crude Glycerol by Anaerobic Mixed Cultures. Waste Biomass Valorization 2018, 11, 1873–1881. [CrossRef]

- Hogendoorn, C.; Pol, A.; Nuijten, G.H.L.; Op den Camp, H.J.M. Methanol Production by “Methylacidiphilum Fumariolicum” Solv under Different Growth Conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol 2020, 86. [CrossRef]

- Bannantine, J.P.; Register, K.B.; White, D.M. Application of the Biosafety RAM and EProtocol Software Programs to Streamline Institutional Biosafety Committee Processes at the USDA-National Animal Disease Center. Applied Biosafety 2018, 23, 100–105.

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Molecular weight | 92.09 g/mol |

| Density at 20°C | 1.261 g/cm³ |

| Viscosity at 20°C | 1499 cP |

| Specific heat at 26°C | 2.42 J/g |

| Heat of formation | 159.6 Kcal/g mol |

| Heat of combustion | 1662 KJ/mol |

| Heat of fusion | 18.3 KJ/mol |

| Fusion point | 17.8 °C |

| Flash point | 177 °C |

| Point of combustion | 204 °C |

| Point of decomposition | 290 °C |

| Authors | Feedstock | Microorganism | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astals et al. (2012) | Swine effluent and crude glycerol | Pig manure was used as inoculum | The best yield was obtained with 4% crude glycerol added to the bioreactor, obtaining a 400% increase in biogas production with respect to monodigestion | |

| Siles et al. (2010) | Crude glycerol and wastewater from the biodiesel production process | Active methanogenic granular biomass | Maximum production was 310 mL of CH4/g per organic matter removed | |

| Beschkov et al. (2012) | Crude glycerol | Klebsiella sp. | The authors carried out the modeling of a multistage biodigester; and from this modeling it is possible to estimate the number of stages necessary so that one stage does not inhibit the other | |

| Fountoulakis et al. (2009) | Urban effluent and crude glycerol | The inoculum was obtained from the anaerobic sludge from the municipal station | The authors observed the production of 1400 mL CH4/d before without adding glycerol and 2094 mL CH4/d after adding glycerol | |

| Oliveira (2015) | Crude glycerol and residual frying oil | Sargassum sp. | Without the addition of glycerol and residual oil, the biochemical potential of Sargassum sp. was 181 ± 1 L CH4/L of DOC and the methane rate increased 56% with the addition of glycerol and 46% with the addition of residual oil | |

| Sawasdee et al. (2019) | Glucose and glycerol | The inoculum was obtained from cassava starch sludge | The highest yield of biogas production was in the 5:5 ratio of glycerol/glucose with a maximum production rate of 8 mL/h | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).