1. Introduction

High-grade serous ovarian cancer is the most common type of ovarian cancer, being the leading cause of death in women diagnosed with gynecological malignancies; it appears to originate from the epithelial tissue, arising primarily from the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum [

1,

2,

3]. Following standard treatment approaches of cytoreductive surgery and platinum-based therapy, the 5-year survival rate is approximately 30% [

4,

5]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has enabled systematic investigations of genomic and molecular alterations that drive ovarian cancer aiming to identify patients who may respond to targeted therapies [

6,

7].

Notably, genomic instability is a hallmark in the formation of tumors, and i

nefficient DNA repair is a critical driving force behind cancer establishment, progression, and evolution [

8]

.

Homologous recombination repair (HRR) is a DNA repair pathway that acts on DNA double-strand breaks and interstrand cross-links [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Many tumor types including ovarian cancer exhibit a deficiency in the HRR pathway; such phenotype has been termed homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) [

13], and it has been extensively shown that the presence of HRD can make tumors present a distinct clinical constitution involving a superior response to platinum-based therapies and poly (adenosine diphosphate [ADP]–ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (PARPi) [

14,

15,

16]. The introduction of PARPis has transformed the management of

high-grade serous ovarian cancer in both relapsed and first-line treatment settings [

17,

18]. Developing methods to reliably determine the HRD status is of critical importance to optimize clinical benefit from these drugs. Thus, diagnostic companies have developed assays to determine HRD status and aid in treatment decisions; however, these assays may differ in what they evaluate and may lead to inconsistent results that can be complicated for prescribing physicians [

19]. In general, the assays have been developed to measure the causes and/or the consequences of the HRD phenotype.

The best characterized causes of HRD in ovarian cancer are germline or somatic mutations in

BRCA1 and

BRCA2 [

20]. Nonetheless, there is now clear evidence that HRD can arise through germline and somatic mutations or even methylation of a wider set of homologous recombination repair (HRR) related genes [

21,

22]. Further characterization of HRR pathway has revealed multiple protein co-factors that are necessary for functional HRR, and mutations in the genes that encode these proteins could also contribute to ovarian cancer [

21,

22]. Regarding testing the consequences of HRD phenotype, the assays are performed to estimate the genomic instability (genomic “scars”) or mutational signatures that measure the patterns of somatic mutations accumulating in HRD cancers irrespective of the underlying defect. Numerous research in ovarian cancer has identified mutational signatures of instability associated with an HRD phenotype including loss of heterozygosity (LOH), telomeric imbalances (TAI), and large-scale transitions (LST) [

23,

24,

25].

Although there are some diagnostic tests commercially available to promote tumor selection for a personalized therapy based on HRD status [

19], the Myriad MyChoice CDx is the most notorious FDA-approved tumor assay to assess chromosomal instability because it incorporates both the causes and consequences of HRD status [

26,

27], while other assays only detect potential causes of HRD status without assessing the consequences. However, this test is still vastly limited for being locally performed, highly priced, and frequently not reimbursed by medical insurance. As an alternative, other commercial assays deployable in diagnostic laboratories that screen for both HRD status and genomic instability were recently launched (SOPHiA DDM

TM HRD Solution and AmoyDx HRD Focus Panel) even though the main challenge is a lack of standardized methods to define, measure, and report HRD status. Hence, conducting studies that assess the correlation of HRD status across different assays is extremely important since it can identify sources of discordance, providing an opportunity to determine the underlying causes of inconstancy and provide information for better use of these assays for cancer treatment decisions. In this study, we aimed to examine the technical viability of in-house HRD testing, particularly for ovarian cancer diagnosis, comparing the results of two commercially available NGS-based tumor tests to the reference assay Myriad MyChoice CDx.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tumor samples

The tumor DNA samples selected for this study were obtained from 85 patients with ovarian cancer referred to genetic testing, upon a medical request, in our laboratory.

High-grade serous ovarian cancer samples originating from distinct primary tissues such as ovaries, fallopian tubes, or peritoneum were retrieved from the pathology department. Archival histological sections of 10 µm from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples were obtained, and a hematoxylin and eosin-stained slide was reviewed by pathologists to select and mark a representative tumor area for macrodissection and DNA extraction. The clinical and pathological features of all samples used in this technical validation study are presented in

Table 1 and

Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. HRD testing

In-house HRD testing assessment was conducted comparing two commercial kits: SOPHiA DDMTM Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Solution and AmoyDx HRD Focus Panel to the reference assay Myriad MyChoice CDx. Despite the different methodologies, both commercial kits allow the simultaneous detection of BRCA status and predict a genomic instability score. While MyChoice CDx testing was performed externally, with FFPE slides being sent to a reference laboratory to perform all analytical steps, the other two methods had DNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing, data analysis, and clinical interpretation performed internally. Regions with the highest tumor cell density, previously marked by a pathologist, were scrapped from five to eight slides for each sample. DNA was extracted using Maxwell RSC DNA FFPE kit (Promega) and quantified using two methods: Qubit™ dsDNA High Sensitivity (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and/or Real-Time quantitative PCR, using the TaqMan™ Fast Advanced Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the TaqMan® Copy Number Assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.2.1. SOPHiA DDMTM HRD solution

DNA library preparation was performed using the SOPHiA DNA Library Prep kit II (SOPHiA GENETICS, USA), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. DNA inputs ranged from 3.9 to 150 ng according to the functional concentration measured by Real-Time PCR. The fragmentation time was adjusted based on the degradation level of the tumor sample. Sequencing libraries were quantified using Qubit™ dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and automated electrophoretic separation was performed to analyze the fragments size distribution using the Genomic DNA ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies). HRD testing from SOPHiA GENETICS involves a Homologous Recombination Repair (HRR) multi-gene panel and a low-pass whole genome sequencing (LP-WGS) that were carried out independently in two steps. First, the HRR panel evaluates single nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions and deletions (InDels), and copy number variations (CNVs) in the coding regions and splicing sites of the following genes:

ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDK12, CHEK1, CHEK2, FANCL, PALB2, PPP2R2A, RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, RAD54L, and

TP53. The HRR panel was sequenced in the MiSeq System from Illumina Inc, using the MiSeq Reagent kit V3 (600 cycles in a Paired-End 2x151 cycles run). The Limit of Detection (LOD) for SNVs and InDels was 5%, and the minimal depth of coverage was 500x (96.05% sensitivity and 99.99% specificity). Importantly, for the evaluation of HRD status in ovarian cancers, it has been demonstrated that only pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in

BRCA1/2 are relevant to current literature data; therefore, despite the other genes in the HRR panel only variants on these two genes were considered in this study. Second, the LP-WGS experiments were performed either on the NextSeq 550 or NovaSeq 6000 sequencing platforms from Illumina Inc, using the NextSeq Mid Output Reagent kit (300 cycles in a Paired-End 2x151 cycles run) or the NovaSeq S1 Reagent kit v1.5 (200 cycles in a Pair-End 2x101 cycles run), respectively. The targeted vertical coverage during sequencing is 1-3x. The primary sequencing output was demultiplexed by bcl2fastq v2.20.0.422, and the reads were processed to trim adapters and low-quality base calls. Data analysis was carried out using the SOPHiA DDM

TM platform, in which the reads were mapped to the human genome (hg19) and sequencing depth was computed and normalized to calculate a genome-wide coverage profile. A convolutional neural network algorithm previously trained based on data from The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA) [

28] takes as input a bitmap-like matrix that reflects the whole genome sequencing coverage profile and outputs a scalar value of Genomic Integrity Index (GII). Tumor samples with scores above 1.8 threshold indicate a GII positive status, reflecting an inability to repair double-strand breaks, whereas scores below that threshold indicate a GII negative status for which PARPi therapy would not be recommended. The GII score had a non-strict range of about -30 up to +30.

2.2.2. AmoyDx HRD Focus Panel

DNA library preparation was performed using the AmoyDx HRD Focus Panel kit (AmoyDx, China), following the manufacture’s recommendations. The assay was intended to determine the HRD status via the detection pathogenic variants in the BRCA gene and the determination of a genomic instability score in the tumor samples in a single workflow. The assay kit is based on the Halo-shape ANnealing and Defer-Ligation Enrichment (HANDLE) system technology, in which the probes contain an extension and ligation arms complementary to the target gene regions. DNA inputs ranging from 50 to 100 ng were pre-denatured and the probes hybridized to the target regions of BRCA1/2. Then, an extension and ligation step of the probes were performed, treated with exonuclease for the digestion of non-hybridized probes and free single and double-stranded DNAs in the solution. The linked probes were amplified by PCR, and the final product was purified. Libraries were quantified with Qubit™ before and after the purification step to verify material losses. A total of 100 ng of each library were polled together and the final concentration was measured on Qubit™. DNA libraries were sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 platform from Illumina Inc., using the NovaSeq SP Reagent kit v1.5 (300 cycles in a Paired-End 2x150 cycles run). In brief, the detection of pathogenic variants was conducted within the coding sequence and at the boundaries of exon-intron of BRCA gene. The estimated Genomic Scar Score (GSS) was calculated by evaluating 24,000 SNPs where GSS equal to or higher than 50 is suggestive of a positive HRD status. The GSS model from AmoyDx is built on machine learning, and it measures genomic instability by weighing distinct types of chromosomal copy number, which was grouped according to the combination of length, type, and site of copy number. Data analysis was carried out using the ANDAS System (AmoyDx, China) with the pipeline version 1.1.1.

2.2.3. Variant classification

Detected variants in

BRCA1 and

BRCA2 were classified for their clinical impact according to the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) [

29], Somatic Oncogenicity SOP—ClinGen (

https://clinicalgenome.org) [

30], and CanVIG-UK (

https://www.cangene-canvaruk.org) [

31] guidelines. Only variants classified as pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), and variants of unknown significance (VUS) were reported.

2.3. Data analysis and visualization

Comparative analysis was conducted on Python 3 with packages Pandas [

32] and SciPy [

33]. Results were considered statistically significant if p-value < 0.05. Data visualization was performed using the packages seaborn [

34] and Matplotlib [

35].

3. Results

3.1. Clinicopathological features of tumor samples

Our evaluation involved the comparison of

BRCA1/2 status and predicted genomic instability (PGI) score with the final assigned sample status obtained from the assays. For this purpose, we utilized a dataset of 85 ovarian carcinoma samples (

Table 1). The median age of the patients during the sample collection was 60 years old. It is important to note that the FFPE samples did not exhibit uniform levels of DNA input, neither quantity nor quality. The estimated tumor content ranged from 20% to over 90%, with DNA input varying from 3.9 to 150 ng.

Supplementary Table S1 presents all relevant information about the samples included in this study, including the pre-analytical variables assessed in our analysis.

3.2. Comparison of predicted genomic instability (PGI) score across different NGS-based methods

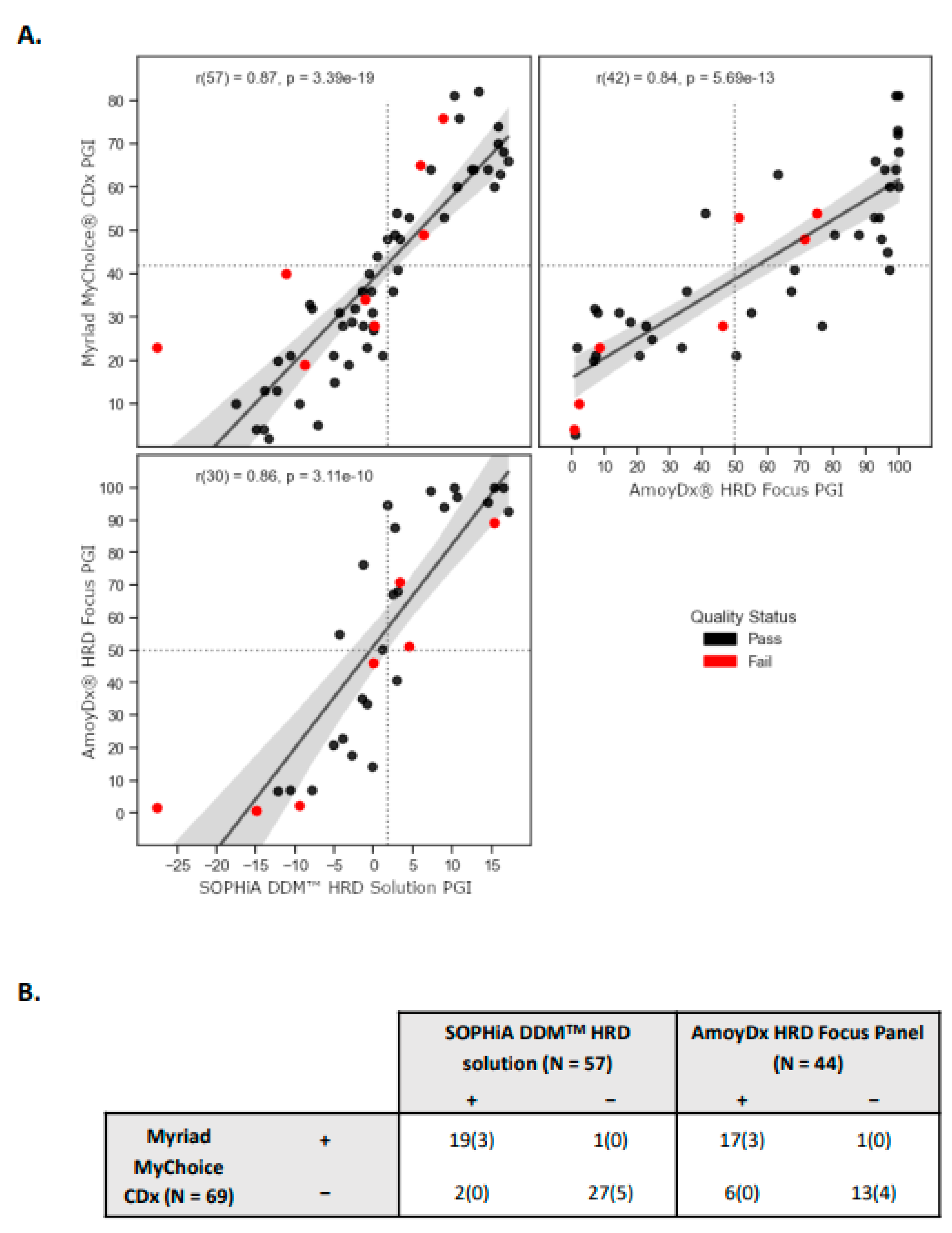

Although the three assays evaluated employ different underlying methods to assess genomic instability in tumor samples, all of them provide scalar values that reflect the PGI score (i.e., higher values indicate greater genomic instability, while lower values indicate lesser instability). We investigated the associations and discrepancies among the methods, and we found an overall strong correlation, with the highest pairwise correlation observed between Myriad and SOPHiA (R = 0.87, p-value = 3.39 × 10

−19;

Figure 1A). It is important to note that the interval ranges and the proportion of failed samples vary between the methods. Also, not all samples could be evaluated using the three methodologies due to insufficient tumor material or DNA quantity. Still, a total of 32 samples were executed across the three assays; in which, for SOPHiA’s test, 96.9% (31 samples) passed the quality control (QC) criteria. One sample was flagged as having a “silent profile” suggesting either a genome-wide profile without copy number variations (CNVs) or low tumor content. For Amoy’s test, 84.4% (27 samples) passed the QC filter, and 5 samples failed the QC criteria (

Supplementary Table S2). This finding is consistent with the 84.2% success rate reported by another group who also evaluated the same commercial assay [

36].

We subsequently evaluated the level of agreement in assigned sample statuses based on the pre-defined thresholds provided by the vendors, specifically 1.8 for SOPHiA and 50 for AmoyDx. In the case of SOPHiA’s test, we observed categorical discrepancies in 3 samples when compared to the results obtained from Myriad’s test. Specifically, 2 samples initially assigned as negative, and 1 sample assigned as positive were predicted to have the opposite status. Notably, these samples exhibited scores near the threshold values of both tests, highlighting the need for careful consideration of their categorical classification. Contrarily, we identified 7 categorical discrepancies between Myriad and AmoyDx, in which 6 samples were initially assigned as being negative by Myriad but were predicted to be positive by AmoyDx (

Figure 1B).

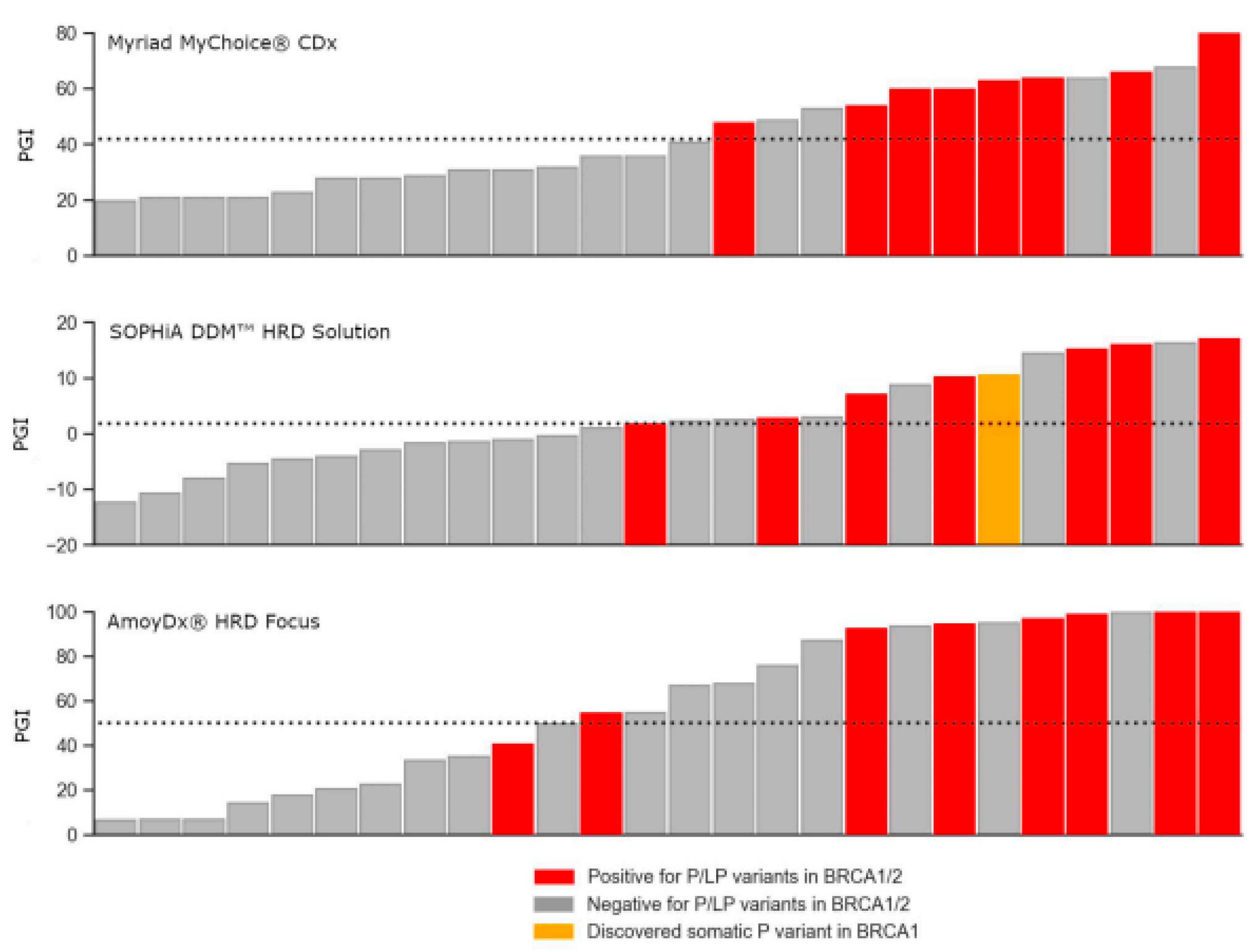

3.3. Correlation of BRCA1/2 status and predicted genomic instability (PGI) score

Considering that a high degree of genomic instability is commonly observed in

BRCA-mutated tumors [

37,

38], we investigated the association and consistency between these two markers in a set of 26 samples that we successfully executed all three methodologies and passed the quality QC criteria. All samples with a detected pathogenic variant in

BRCA1/2 were positive for genomic instability, the only exception was one sample with a pathogenic variant in

BRCA1 that was categorized as negative for genomic instability in the AmoyDx’s test. 66.7% (8 of 12) BRCA-positive samples were also HRD-positive for Myriad, 57.1% (8 of 14) for SOPHiA, and 43.8% (7 of 16) for AmoyDx. As all pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants from Myriad’s results were confirmed in the other two tests, this small association deflation between

BRCA1/2 status and PGI score is due to more samples having a PGI-positive score in the later assays. Noteworthy, the SOPHiA test was able to detect one somatic variant in

BRCA1 with a Variant Allele Fraction (VAF) of 9.8% not previously reported by the other two tests (

Figure 2).

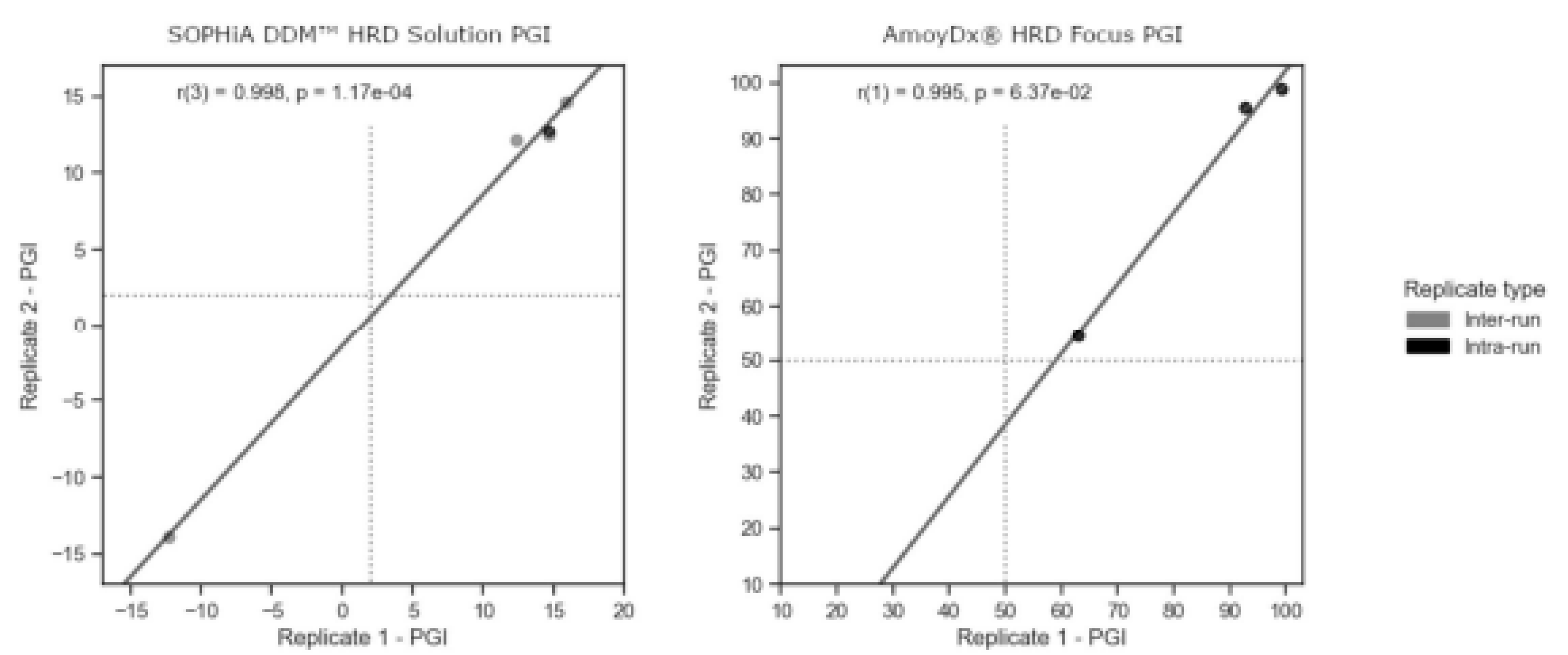

3.4. Determination of testing performance parameters

Controlling experimental variability is crucial in any clinical test. NGS-based assays, being a multi-step process, are particularly susceptible to variations that may arise from extraction, library preparation, and sequencing, as these steps involve non-deterministic processes. Even prior to these steps, the extraction of DNA from somatic specimens relies on a biopsy process that samples a heterogeneous population of cells. To evaluate the reproducibility of our experiments, we sequenced 7 unique samples as replicates within or between sequencing runs. Among them, 4 samples were sequenced across different sequencing batches, while one sample was sequenced within the same batch for SOPHiA and 3 samples within the same batch for AmoyDx (

Figure 3). Remarkably, we observed a high correlation of results for all tested samples, for SOPHiA r = 0.998 (p-value = 1.17 × 10

−4) and for AmoyDx r = 0.995 (p-value = 0.064;

Figure 3). These results highlight the consistency and reliability of the obtained data, indicating robust reproducibility within our experimental setup.

In respect to the comparison of HRD status (i.e., final assigned sample result) of the two assays to the reference Myriad’s test, the positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were 90.9% and 96.3% for SOPHiA’s test, respectively, while AmoyDx’s test achieved 75% PPV and 100% NPV. In our cohort, we identified 44.9% and 64.9% as HRD-positive tumors using SOPHiA and AmoyDx, respectively (

Table 2).

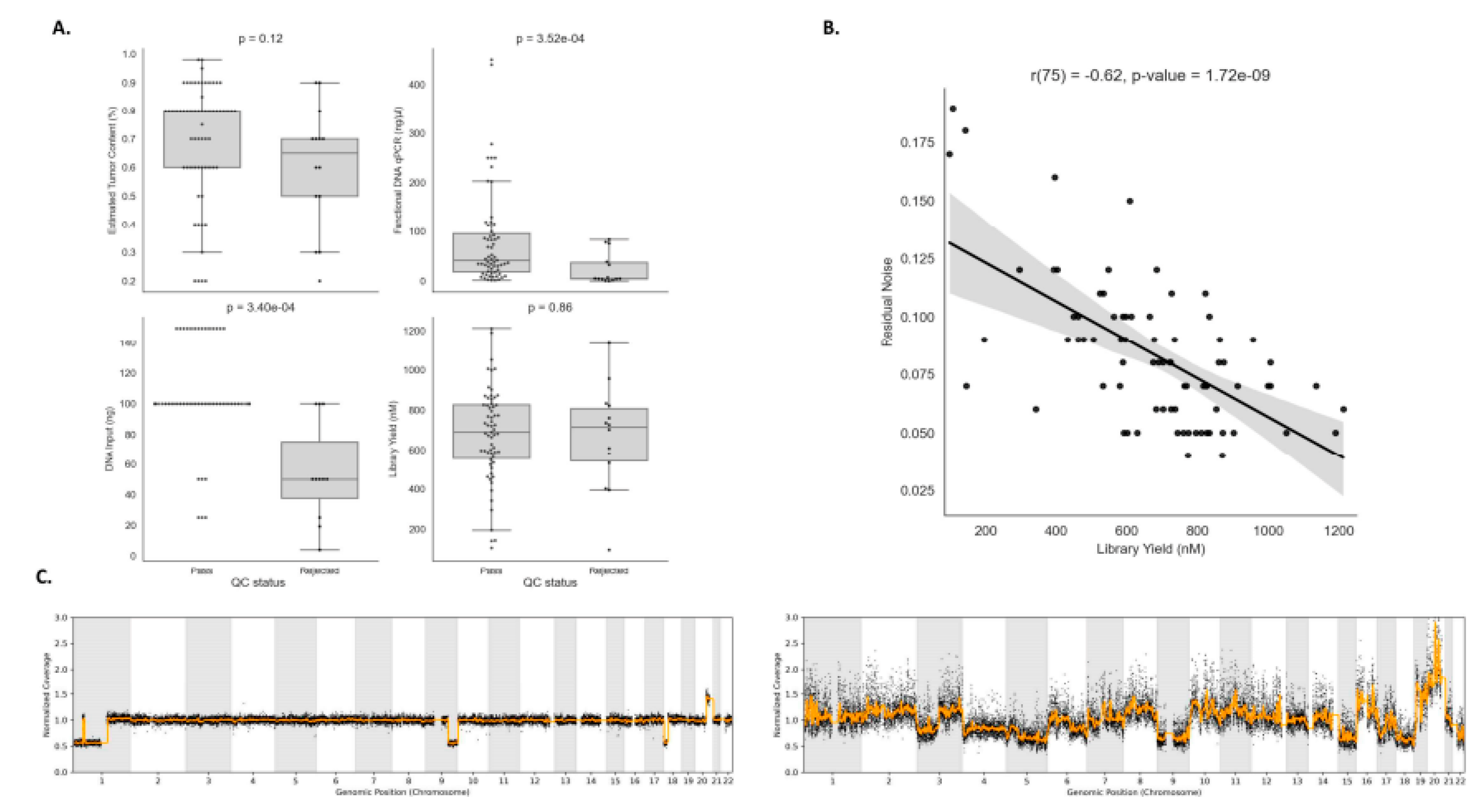

3.5. Association of pre-analytical variables with low confidence NGS results

Pre-analytical variables verification is a crucial step to ensure a reliable experiment result, and it can also assist in the prediction of samples that are likely to pass or fail during the QC step. Both in-house HRD testing protocols evaluated suggest at least 30% estimated tumor content, but have slightly different ranges for DNA input requirement, between 10–200 ng for SOPHiA, and 50–100 ng for AmoyDx. Among the four pre-analytical variables evaluated, we observed that only functional DNA qPCR and DNA input were statistically significant between pass and low-confidence experiments (p-value = 3.52 × 10

−4; p-value = 3.40 × 10

−4) (

Figure 4A). However, we observed a negative correlation between DNA library yield and residual noise (R = -0.62, p-value = 1.72 × 10

−9), which is computed by measuring the standard deviation of the normalized genome sequencing coverage profile with respect to the smoothed normalized genome sequencing coverage profile (

Figure 4B). Indeed, it is expected that samples with low values of library yield have more fragmented DNA, resulting in potential amplification biases and less uniform coverage in the genome, making the analysis of those experiments more challenging.

Figure 4C shows two examples of samples that have low and high residual noise profiles.

4. Discussion

HRD testing provides relevant information to personalize patients’ treatment options, and it has been progressively incorporated in diagnostic laboratories. Although the Myriad MyChoice® CDx assay was clinically validated and became a reference in the market, unfortunately, the test is not accessible to all patients. Besides being high-priced and not reimbursed, a centralized assay poses significant challenges such as the considerable rejection rate due to the strict quality requirements of externalized technical procedures and the increased turnaround time. Thus, considering the clinical need for a lower-cost, highly accurate, and reduced laboratory turnaround time, other assays were recently launched to determine HRD status. However, the methodologies are different and the uncertainty in how to measure and report HRD status can potentially lead to low adoption of this test in clinical routine. To simplify technical procedures workflows and data analysis interpretation, many attempts have been made by several medical centers to employ in-house HRD testing. Here, we report our experience implementing HRD testing in a clinical diagnostic setting. We evaluated the feasibility of in-house HRD testing, comparing the results of two commercially available NGS-based tumor tests to the reference assay Myriad MyChoice® CDx. The use of a clinically representative dataset of tumor samples allowed a systematic assessment of detection power and concordance rate of HRD status across the assays, identifying sources of inconstancy and providing information for better use of these assays for clinical decision making.

In the clinical setting, HRD status is determined by measuring either evidence for the potential cause or consequence of HRD status. Although patients with germline mutations in

BRCA1/2 are defined as harboring HRD tumor phenotype, there is a group of approximately 20% of patients that present a positive HRD status based on tumor genomic analyses. For this reason, we selected tumor assays that allowed simultaneous detection of

BRCA status and genomic instability. It is also worth mentioning that we extensively tested commercial solutions available at the time of our analysis, even before one of them was released to the market, but this is an area of active research and development by vendors, and new kits with improvements are being released from time to time. Nonetheless, to our knowledge, SOPHiA DDM

TM HRD solution and AmoyDx

® HRD Focus Panel are still the main two commercially available assays deployable in the clinical setting that provide a more comprehensive analysis to determine HRD status. In our analysis, we observed an overall strong correlation across the three assays evaluated, regardless of the different underlying methods employed to assess genomic instability in tumor samples. The highest pairwise correlation observed was between Myriad and SOPHiA and this assay achieved PPV and NPV, 90.0% and 96.3%, respectively; but we could also observe inter-assay discordances in cases with a PGI score close to the predefined cut-off values. Interestingly, our findings are consistent with previous reports regarding overall agreement scores and success rates among the three commercial assays [

39,

40].

Despite our results showing that employment of in-house HRD testing is feasible, defining technical procedures workflows as well as data analysis is not trivial, and many aspects should be considered to achieve successful implementation. The control of pre-analytical conditions of tumor samples is one of the critical aspects that should be taken into consideration. Inappropriate tissue handling (delayed fixation and over-fixation, inferior paraffin wax quality, and inadequate melting temperature) may modify the quality of the sample, impacting molecular test results. We also anticipate that tumor samples previously submitted to neoadjuvant chemotherapy are more suitable to result in unsatisfactory genomic instability analysis. For NGS-based tumor assays, representative tumor area selection and assessment of the percentage of neoplastic cells, necrosis, and inflammatory components are also important. A minimum of 30% tumor component is recommended to guarantee the detection of a variant through molecular techniques. For some cancers with HRD, this can be difficult to achieve due to abundant inflammatory cell infiltration and such limitations for the analysis should be clearly stated in the medical report. It is recommended that molecular laboratories and pathology departments maintain quality standards within both pre-analytical and analytical steps. Noteworthy, as shown in our results, when low levels of functional qPCR and insufficient amounts of DNA input are used during library preparation steps, there is an increased chance of low confidence/inconclusive results for the sample being tested. Also, we demonstrated a negative correlation between library yield and residual noise from sequencing experiments. Low-confidence sequencing results because of low DNA library concentration can be related to more fragmented DNA molecules, resulting in potential amplification biases and less uniform coverage in the whole genome.

In our clinical routine procedure, we could significantly reduce the turnaround time with in-house HRD testing. From the test request to the available medical report was on average 7 days, whereas the Myriad MyChoice® CDx turnaround time in any diagnostic setting in Brazil is 27 days, being affected by international testing transportation. In addition, the cost of in-house HRD testing corresponds to nearly one-third the price of the Myriad MyChoice® CDx. Considering the clinical need to offer the most effective therapy for the patient in a timely manner, with a widespread testing routine, allowing more patients to benefit from advances in precision medicine, these aspects are crucial to establish the clinical utility of an assay. However, despite the compelling evidence and advantages of implementing in-house HRD testing, our study presents some limitations. The clinical validity and utility of in-house HRD testing was beyond the scope of this research and we were unable to contribute with results on this aspect. It is likely that most patients in this study are still undergoing adjuvant treatment and are waiting to start maintenance treatment. Maintenance treatment and follow-up are fundamental parameters, particularly in discordant cases to assess the clinical outcomes or the benefit from personalized therapy. We were also unable to calculate the failure rate between in-house HRD testing with the reference Myriad MyChoice® CDx assay. This would be valuable to provide a measure of the reliability of the test.

In conclusion, our study shows that the implementation of in-house HRD testing in diagnostic laboratories is technically feasible and it can be reliably performed with commercial assays. Also, the turnaround time is compatible with clinical needs, being an ideal alternative to offer to a broader number of patients, while still maintaining high-quality standards at more accessible price tiers. This is the largest HRD testing evaluation using different methodologies and provides a clear picture of the robustness of NGS-based tests currently offered in the market. The present data can be a valuable resource for other clinical laboratories that aim to implement an in-house HRD testing routine.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.-S.; J.E.K.; F.M.; C.S.-N.; G.L.Y.; Methodology, A.B.; P.M.P.; Validation, C.A.S.; J.S.S.; M.C.B.; F.A.O.; M.G.P.; Formal analysis, R.G.-S.; J.E.K.; Data curation, R.G.-S.; J.E.K.; Writing—Review & Editing, R.G.-S.; D.V.; Supervision, F.M.; C.S.-N.; G.L.Y.; Project administration, F.M.M.; L.G.A.; P.M.M.; A.B.O.; F.M.; Funding acquisition, C.S.-N.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee from Hospital Nove de Julho (CAAE: 55810222.0.0000.5455), and informed consent was obtained from all patients for genetic testing.

Acknowledgments

G.L.Y was affiliated with the Instituto da Criança and Centro de Pesquisas Sobre Genoma Humano e Células Tronco at the University of Sao Paulo at the time of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

G.L.Y. reports that he served as a genomic consultant to DASA. All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- Lisio, M. A., Fu, L., Goyeneche, A., Gao, Z. H. & Telleria, C. High-grade serous ovarian cancer: Basic sciences, clinical and therapeutic standpoints. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, vol. 20 . [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. et al. Cell origins of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancers 2018, vol. 10 . [CrossRef]

- Reid, B. M., Permuth, J. B. & Sellers, T. A. Epidemiology of ovarian cancer: a review. Cancer Biology and Medicine 2017, vol. 14 9–32. [CrossRef]

- Nick, A. M., Coleman, R. L., Ramirez, P. T. & Sood, A. K. A framework for a personalized surgical approach to ovarian cancer. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2015, vol. 12 239–245. [CrossRef]

- Pomel, C. et al. Cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer. Cancer Imaging 7, 210–215 (2007).

- Harbin, L. M., Gallion, H. H., Allison, D. B. & Kolesar, J. M. Next Generation Sequencing and Molecular Biomarkers in Ovarian Cancer—An Opportunity for Targeted Therapy. Diagnostics 12, (2022).

- Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, vol. 144 646–674. [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S., Gorgoulis, V. G. & Halazonetis, T. D. Genomic instability an evolving hallmark of cancer. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2010, vol. 11 220–228. [CrossRef]

-

Prevalence of Homologous Recombination-Related Gene Mutations Across Multiple Cancer Types. (2018).

- Thompson, L. H. & Schild, D. Homologous recombinational repair of DNA ensures mammalian chromosome stability. Mutation Research vol. 477 (2001).

- Thacker, J. The role of homologous recombination processes in the repair of severe forms of DNA damage in mammalian cells.

- Radhakrishnan, S. K., Jette, N. & Lees-Miller, S. P. Non-homologous end joining: Emerging themes and unanswered questions. DNA Repair (Amst) 17, 2–8 (2014).

- Marquard, A. M. et al. Pan-cancer analysis of genomic scar signatures associated with homologous recombination deficiency suggests novel indications for existing cancer drugs. Biomark Res 3, (2015).

- Lupo, B. & Trusolino, L. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in cancer: Old and new paradigms revisited. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Reviews on Cancer vol. 1846 201–215 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.07.004 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. et al. First-line PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer: Summary of an ESMO Open—Cancer Horizons round-table discussion. ESMO Open vol. 5 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lord, C. J. & Ashworth, A. PARP inhibitors: Synthetic lethality in the clinic. Science (2017) vol. 355 1152–1158. [CrossRef]

- Golia D’Augè, T. et al. Prevention, Screening, Treatment and Follow-Up of Gynecological Cancers: State of Art and Future Perspectives. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 50, 160 (2023).

- Giannini, A. et al. PARP Inhibitors in Newly Diagnosed and Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y. C., Lin, P. H. & Cheng, W. F. Homologous Recombination Deficiency Assays in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: Current Status and Future Direction. Frontiers in Oncology (2021) vol. 11 . [CrossRef]

- Norquist, B. M. et al. Inherited mutations in women with ovarian carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2, 482–490 (2016).

- Pennington, K. P. & Swisher, E. M. Hereditary ovarian cancer: Beyond the usual suspects. Gynecologic Oncology (2012) vol. 124 347–353. [CrossRef]

- Moschetta, M., George, A., Kaye, S. B. & Banerjee, S. BRCA somatic mutations and epigenetic BRCA modifications in serous ovarian cancer. Annals of Oncology vol. 27 1449–1455 Preprint at . [CrossRef]

- Abkevich, V. et al. Patterns of genomic loss of heterozygosity predict homologous recombination repair defects in epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 107, 1776–1782 (2012).

- Birkbak, N. J. et al. Telomeric allelic imbalance indicates defective DNA repair and sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents. Cancer Discov 2, 366–375 (2012).

- Popova, T. et al. Ploidy and large-scale genomic instability consistently identify basal-like breast carcinomas with BRCA1/2 inactivation. Cancer Res 72, 5454–5462 (2012).

- Ray-Coquard, I. et al. Olaparib plus Bevacizumab as First-Line Maintenance in Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 381, 2416–2428 (2019).

- Moore, K. et al. Maintenance Olaparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 379, 2495–2505 (2018).

- Nik-Zainal, S. et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature 534, 47–54 (2016).

- Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine 17, 405–424 (2015).

- Horak, P. et al. Standards for the classification of pathogenicity of somatic variants in cancer (oncogenicity): Joint recommendations of Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen), Cancer Genomics Consortium (CGC), and Variant Interpretation for Cancer Consortium (VICC). Genetics in Medicine 24, 986–998 (2022).

- Garrett, A. et al. Cancer Variant Interpretation Group UK (CanVIG-UK): An exemplar national subspecialty multidisciplinary network. J Med Genet 57, 829–834 (2020).

- Heldens, S. et al. litstudy: A Python package for literature reviews. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

- Waskom, M. seaborn: statistical data visualization. J Open Source Softw 6, 3021 (2021).

- hunter2007.

- Fumagalli, C. et al. In-house testing for homologous recombination repair deficiency (HRD) testing in ovarian carcinoma: a feasibility study comparing AmoyDx HRD Focus panel with Myriad myChoiceCDx assay. Pathologica 114, 288–294 (2022).

- Timms, K. M. et al. Association of BRCA1/2 defects with genomic scores predictive of DNA damage repair deficiency among breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Research 16, (2014).

- Konstantinopoulos, P. A., Ceccaldi, R., Shapiro, G. I. & D’Andrea, A. D. Homologous recombination deficiency: Exploiting the fundamental vulnerability of ovarian cancer. Cancer Discovery (2015) vol. 5 1137–1154 . [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, C. et al. In-house testing for homologous recombination repair deficiency (HRD) testing in ovarian carcinoma: a feasibility study comparing AmoyDx HRD Focus panel with Myriad myChoiceCDx assay. Pathologica 114, 288–294 (2022).

- 40. Pepe, F. et al. In-house homologous recombination deficiency testing in ovarian cancer: A multi-institutional Italian pilot study. J Clin Pathol (2023). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).