1. Introduction

In the last years, testing on

BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants (PVs) in patients diagnosed with epithelial tubal/ovarian cancer (EOC) has become increasingly important. While germline testing for

BRCA1/2 PVs has been available for EOC patients in most medical centers for over a decade, the introduction of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor (PARPi) therapy has created the need to also identify patients with somatic PVs, as tumors with

BRCA1/2 PVs (somatic and germline) exhibit superior sensitivity towards this therapy [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommend performing both somatic and germline testing in EOC patients [

6,

7]. To efficiently perform both tests, many centers analyze DNA from tumor samples first using next-generation sequencing (NGS) and subsequently analyze germline pathogenic variants (GPVs) only in those with a PV in the tumor (also referred to as tumor PV (TPV)). Patients with a positive family history and/or no or inconclusive tumor test results are also eligible for germline testing. This sequential workflow reduces the number of referrals for genetic counseling and testing, as well as the associated patient burden, and is considered cost-effective [

8,

9,

10].

In the Netherlands, this tumor-first workflow is fully implemented in specialized centers. However, there is no standardization of testing procedures, including the techniques, gene assays, or sequence machine used for the analyses. In addition to a lack of national guidelines on testing procedures, data on the performance of the tumor tests, as well as test outcomes, throughout the Netherlands remain scarce. For these reasons, we evaluated the execution of BRCA1/2 TPV testing in the Netherlands with real-world data from 2019 and provided insight into the number of BRCA1/2 TPVs detected, and the techniques used in Dutch testing centers.

2. Materials and Methods

Patients diagnosed with EOC in 2019 in the Netherlands were identified with help of the nationwide network and registry of histo- and cytopathology in the Netherlands (PALGA) [

11]. This database contains excerpts of all pathology reports from pathology departments in The Netherlands and has full national coverage since 1991. The pathology laboratories in the Netherlands are ISO-15189 certified and quality of accredited laboratories is evaluated through various ways, including internal and external audits as well as interlaboratory quality comparisons.

Anonymous pathology reports regarding the execution of

BRCA tumor tests were retrieved from all patients diagnosed with EOC in 2019. These pathology reports were linked to data from the Netherlands Cancer Registry [

12] to obtain the FIGO stage for each patient. Patients were excluded if diagnosed with FIGO stage I or II EOC, as these patients have no indication for adjuvant PARPi therapy [

13].

For all included patients, data regarding histological subtype and

BRCA1/2 tumor NGS analyses (including amongst other variables: tumor NGS analysis performed (yes/no); tumor NGS results; technique used; and genes analyzed) were obtained from the pathology reports. Additionally, it was checked whether the tumor test was complemented with a

BRCA1 multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis (yes/no) and MLPA test result was collected (

BRCA1 PV: yes/no). Information on the detection of variants of unknown clinical significance (VUS), was also collected when reported. Dutch pathology laboratories follow national guidelines for establishing the classification and relevance of detected variants, which include close collaboration with genetics departments of medical centers [

14].

In case of a detected

BRCA1/2 TPV in EOC of ambiguous or unspecified histological subtype (e.g., carcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS)), an expert pathologist reviewed the pathology reports and further classified the tumor, if possible, based on information from the corresponding pathology reports and according to the World Health Organization classification of female genital tumors of 2020 [

15].

The following endpoints were analyzed in this cohort of advanced stage EOC patients: 1) number of diagnosed EOC by histological subtype; 2) prevalence of BRCA1/2 tumor variants by histological subtype, including TPVs and VUS; 4) (reporting of) techniques and platforms used in BRCA1/2 tumor NGS analyses, including the specific genes analyzed; and 5) lead times of BRCA1/2 tumor analyses.

Data were reported as frequencies and percentages and lead times as mean, standard deviation and minimum and maximum values. Information on the type of technique used for target enrichment was collected and classified as hybrid capture techniques or PCR-based amplicon techniques. The number of TPVs detected by BRCA1 MLPA analysis were reported separately from those detected by NGS. Differences in BRCA1/2 yield and histological subtype between hybrid capture and PCR-based techniques were compared using Chi-square exact test or Fisher’s exact test. Lead time of the BRCA1/2 tumor analyses was defined as the number of days between the date of receival of tumor material in pathology centers and the reported date of the tumor test results. Lead time could only be calculated when both dates were reported.

3. Results

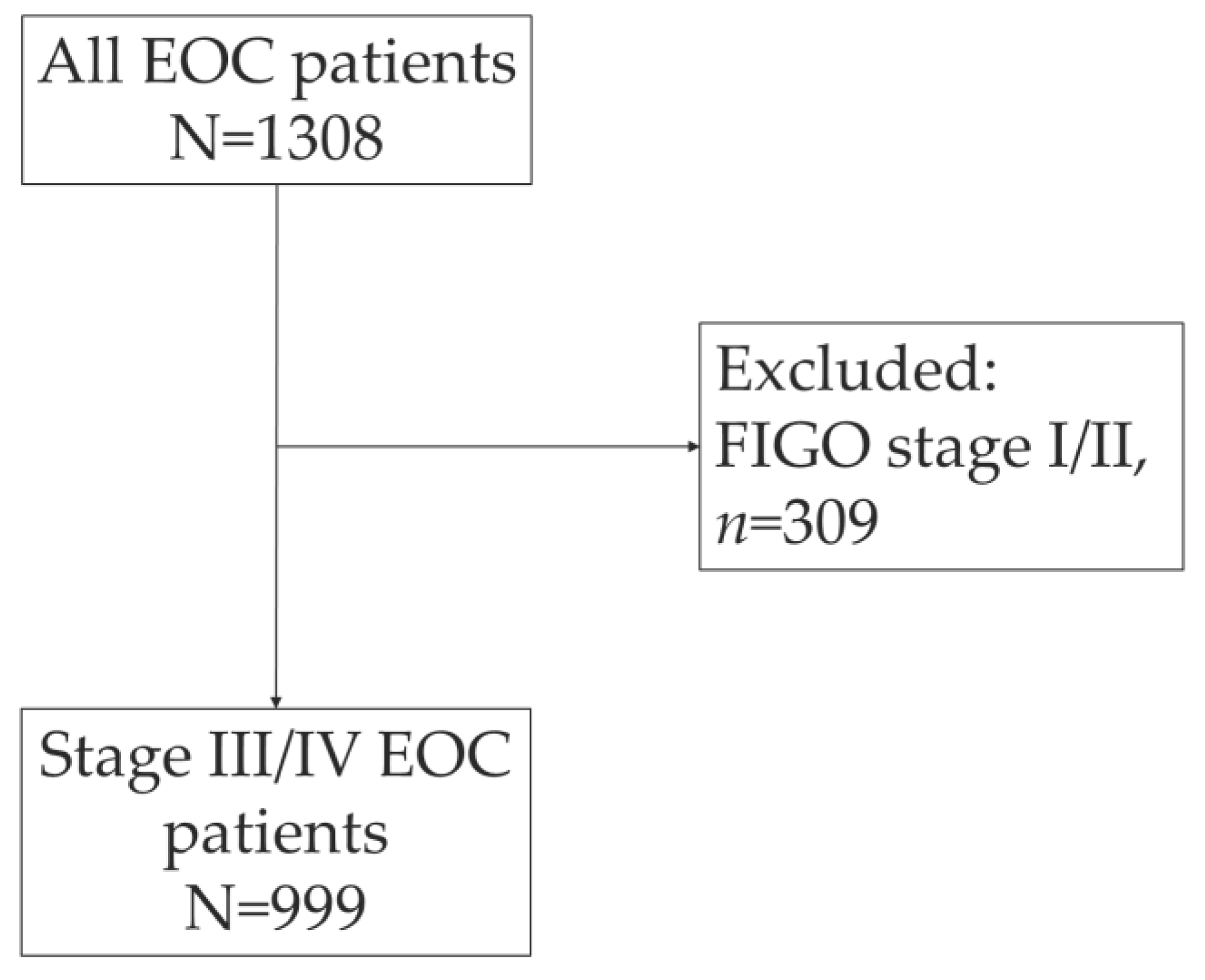

The PALGA search identified 1308 women who were diagnosed with EOC in 2019 in The Netherlands (

Figure 1). After exclusion of patient with early-stage disease (FIGO I/II) (

n=309, 23.6%), a total of 999 EOC patients were included. Most EOC patients were diagnosed with high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) (

n=682; 68.3%), followed by low-grade serous carcinoma (

n=46, 4.6%) (

Table 1). The histological subtype was not reported in the pathology report for 5.8% of the patients.

BRCA1/2 tumor NGS analyses were performed in 502 patients (50.3%), and 62 TPVs were detected; 31 TPVs in

BRCA1 and 31 TPVs in

BRCA2 (

Table 2). A complementary MLPA analysis was performed for 344 patients (34.4%) and detected an additional 12

BRCA1 TPVs. Combining the TPVs detected through NGS and MLPA, most

BRCA1/2 TPVs were detected in HGSC (

n=67, 90.5%) (

Supplementary Table S1). The remaining seven TPVs were detected in low-grade serous carcinoma (

n=1; 1.4%), endometrioid carcinoma (

n=1; 1.4%), clear cell carcinoma (

n=1; 1.4%), carcinosarcoma (

n=3; 4.1%) and carcinoma NOS (

n=1; 1.4%). In addition, the detection of six VUS was reported in the pathology reports. Caution must be taken when interpreting the latter, since reporting a detected VUS is not universally adopted by all testing centers.

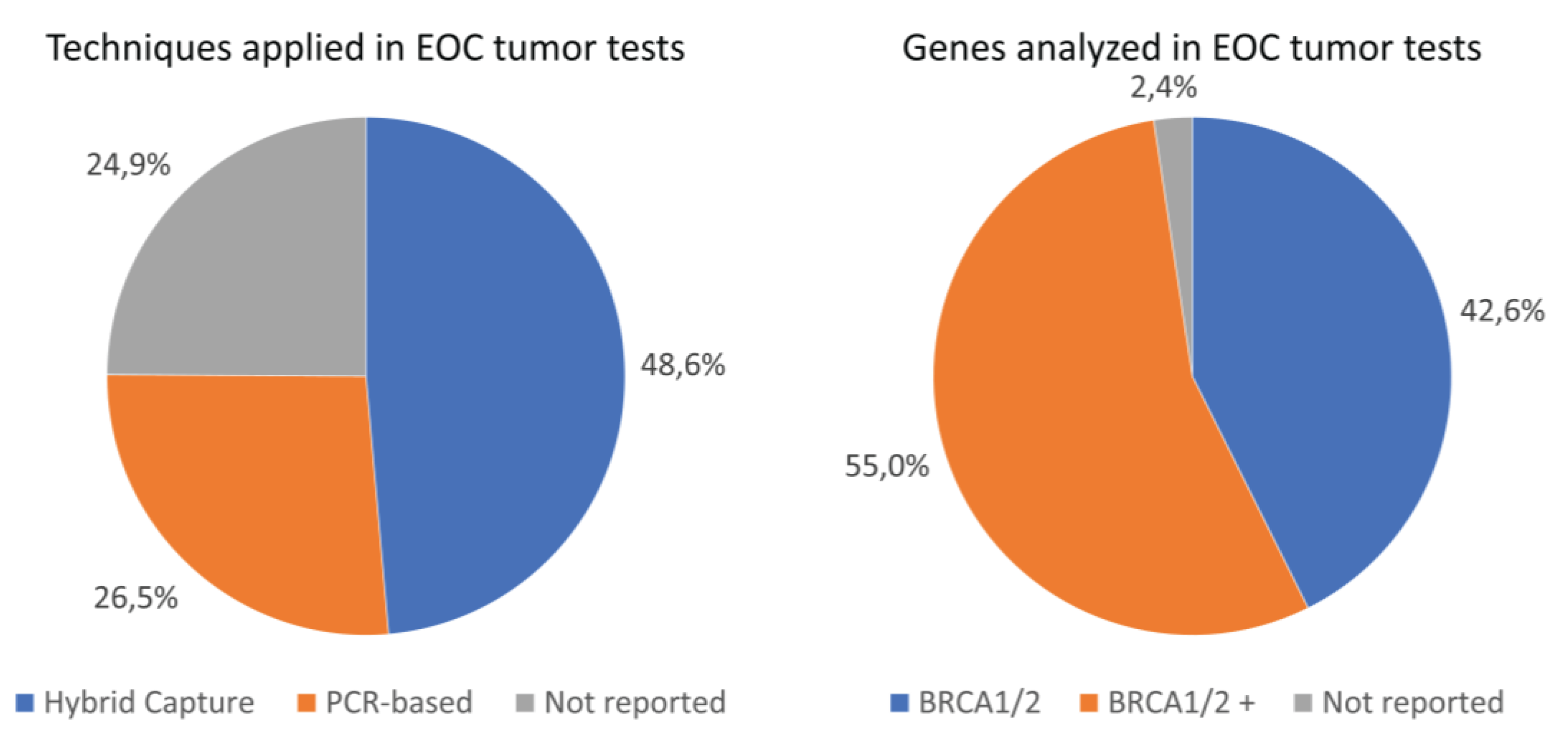

Figure 2 visualizes the distribution of different techniques applied for the target enrichment. Of the 502

BRCA1/2 tumor analyses performed in our cohort, a total of 244 analyses (48.6%) were performed using the hybrid capture technique and 133 analyses (26.5%) using the PCR-based technique (

Figure 2). Information on the target enrichment technique applied was missing for a substantial proportion of the performed

BRCA1/2 tumor analyses (unknown technique:

n=125, 24.9%). The proportion of

BRCA1/2 TPVs detected did not significantly differ between the hybrid capture and PCR-based techniques (12.3% and 21.1%, respectively, P-value=0.078), neither did the distribution of histological subtypes between the type of technique (P-value=0.882) (

Supplementary Table S2).

All tests performed using the hybrid capture technique used the single-molecule molecular inversion probes (smMIP) method:

n=244 (

Table 3). A total of four different assays were used for the PCR-based techniques: custom Ampliseq BRCAv5 assay (

n=59,44.4%); Multiplicom BRCA Tumor MASTR Plus assay (

n=62,46.6%); Oncomine BRCA Research assay (

n=11, 8.3%) and Agilent SureMASTR HRR assay (

n=1, 0.8%). Moreover, most tumor tests analyzed more genes than only

BRCA1/2 (

n=276, 55.0%). For 2.4% of all tumor tests (

n=12), the specific genes analyzed were not reported. Assays used and genes analyzed in analyses not reporting target enrichment techniques are reported in

Supplementary Table S3.

More than half of the

BRCA1/2 tumor analyses were performed on an Illumina platform (

n=262; 52.2%), 15.1% on an Ion Torrent platform, and in more than 30% of the

BRCA1/2 tumor analyses the platform used was not specified (

Supplemental Table S4). Lead times were analyzed for the cases with reported dates of receival of tumor material and test result (

n=376). Mean lead time was 38.3 days (SD=64.2 days), ranging from 0 days to 525 days (

Supplementary Table S5).

4. Discussion

The current study provides insight into the execution and outcomes of BRCA1/2 tumor analyses in patients diagnosed with EOC in 2019 in the Netherlands. Of the 999 advanced stage EOC patients included in this study, BRCA1/2 tumor NGS analyses were performed for 502 patients (50.3%). This study shows that substantial variety exists in the execution of tumor analyses in EOC regarding the techniques and assays used, and the (types of) genes analyzed.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to provide insight into the nationwide landscape of

BRCA1/2 tumor testing in EOC. Besides providing insight into the applied techniques, assays and analyzed genes, this study also highlights the lack of uniform reporting, despite high-quality centralized care and utilization of a national registration database. A great proportion of pathology reports lacked information on used techniques and assays, analyzed genes, and dates. For this reason, lead times could only be analyzed for a subset of 376 tests. Importantly, lead time is included in the criteria of national quality control standards that are currently being implemented [

16]. Inadequate reporting limited quality assessment in the current study and could limit the exchange of diagnostic information between clinicians and tailoring of a patient’s treatment in clinical practice. Fortunately, studies show that pathology reporting in oncology is changing from a narrative approach to standardized synoptic reporting, leading to significantly increased completeness of the pathology reports [

17,

18,

19].

A complementary

BRCA1 MLPA analysis was performed in 344 patients. In these patients, the MLPA analysis detected an additional 3.5% of

BRCA1 TPVs. Estimates of the prevalence of large genomic rearrangements in

BRCA1 in EOC specifically remain limited, which makes it challenging to estimate the number of TPVs missed when not performing an MLPA analysis alongside the NGS. A Slovakian study performed MLPA analyses in 39 tumor samples of high-grade serous ovarian cancer and detected one pathogenic

BRCA1 deletion (2.6%) [

20]. Pathogenic large rearrangements were also analyzed in 20,000 ovarian tumors with NGS and were detected in 0.7% of the cases, which reflected a total of 6.3% of all

BRCA1/2 TPVs detected in the cohort [

21]. This lower percentage could be explained by the lower sensitivity of NGS in detecting large deletions and duplications. Furthermore, the presence of founder mutations, as established in

BRCA1 in The Netherlands [

22], increases the number of TPVs to be detected by MLPA analysis and should be considered when making direct comparisons.

The proportion of

BRCA1/2 TPVs detected did not significantly differ between the hybrid capture technique, which constituted solely of smMIP-based assays [

23], and the PCR-based techniques and does therefore not indicate significant performance differences between the techniques regarding

BRCA1/2 TPV yield. It must be noted, that for a thorough comparison of

BRCA1/2 yield in hybrid capture versus PCR-based technique, a more diverse inclusion of hybrid capture techniques is preferred. Few studies have compared the overall performance of hybrid capture and PCR-based approaches in detecting pathogenic variants. A better overall performance was reported for the hybrid capture technique in detecting

BRCA1/2 PVs from FFPE EOC tumor samples compared to the PCR-based technique [

24], and similar findings were reported in lymphoma [

25]. In general, these studies linked the PCR-based technique to a lower sensitivity, due to amplicon dropout and insufficient cover. On the other hand, PCR-based techniques are also reported to be suitable for accurate detection of

BRCA1/2 PVs [

26]. Moreover, it requires a lower quality and quantity of DNA and is significantly less time consuming, which are important parameters for a laboratory to consider when choosing between methods [

27,

28,

29]. Results of the current study do not show quality differences between the techniques and thereby justify the use of both techniques in

BRCA1/2 TPV detection. In the Netherlands, pathology laboratories are free to choose techniques, given the technique is validated, and the national quality control standard for molecular diagnostics ensures that these techniques meet high-quality criteria [

16]. This subsequently guarantees high-quality diagnostics and care for all patients.

A total of 74

BRCA1/2 TPVs were detected in this EOC cohort (14.7% of all tests) of which 90.5% were detected in HGSC. Our overall proportion of

BRCA1/2 TPVs in EOC unselected for histotype is similar compared to the proportion we reported previously of 13% in a Dutch multi-center study including a consecutive series of EOC patients [

30]. The proportion is slightly lower compared to proportions in EOC reported by another Dutch study of 16.7%, which included a complementary MLPA analysis for all cases, and also lower compared to a proportion of 19% reported in the United States [

8,

31].

This study shows that EOC tumor tests for

BRCA1/2 TPV detection were already performed for 50% of all patients before this was officially recommended by national and international guidelines [

6,

7,

32]. Currently, the tumor testing is implemented nationwide, testing is centralized mostly in academic hospitals, and comprehensive gene panels are more frequently applied. It should be noted that the

BRCA1/2 tumor test rate of 50.3% reported in this study does not imply that only half of all patients received

BRCA1/2 testing. The timeframe analyzed here was before national guidelines recommended tumor testing in EOC, and therefore it is likely that medical centers followed former guidelines and referred patients for genetic counseling and germline testing instead [

33].

This study has several strengths and limitations. Strengths include the analysis of real-world clinical data with full nationwide coverage of all EOC pathology reports. Linking the data from narrative pathology reports to clinical characteristics such as FIGO stage allowed us to tailor this evaluation to the population of interest, namely FIGO stage III/IV patients. Nevertheless, data requests from national registries are subject to prespecified timeframes and the possibility exists that tumor tests were requested beyond this timeframe for patients in our population. This may have led to an underestimation of the proportion of EOC patients who received a tumor test. Finally, this study analyzed the execution of tumor tests before full completion of the nationwide implementation of the tumor testing and therefore it is likely that not all centers who are currently performing the tumor testing are included.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the heterogeneity in the execution of EOC tumor testing in The Netherlands in 2019 despite centralization of testing in specialized centers. Findings of this study are not indicative of quality differences between techniques used and nationally implemented quality control standards ensure high-quality implementation of reliable BRCA1/2 tumor testing. This is crucial for identifying all patients with BRCA1/2 TPVs to provide high quality of care as well as for guiding genetic cascade testing to ultimately prevent cancer in unaffected relatives with BRCA1/2 GPVs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Prevalence of

BRCA1/2 TPVs by histological subtype of EOC. Table S2: Prevalence of

BRCA1/2 TPVs and histological subtypes for analyses reporting hybrid capture or PCR-based techniques. Table S3: Assays used and genes analyzed in analyses not reporting target enrichment techniques. Table S4: Type of platforms used for

BRCA1/2 tumor tests. Table S5: Lead times for

BRCA1/2 tumor tests, reported in days.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L., A.E., J.B., M.M., and G.B.; methodology, G.B.; formal analysis, L.L., A.E., G.B.; investigation, L.L.; data curation, L.L..; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, A.E., J.B., S.W., M.M., G.B.; supervision, G.B.; project administration, S.W.; funding acquisition, S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and data requests were approved by the scientific and privacy committees of IKNL (application number: K21.046) AND PALGA (application number: LZV2020-224).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the registration team of the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization (IKNL) for the collection of data for the Netherlands Cancer Registry.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- DiSilvestro, P., et al., Overall Survival With Maintenance Olaparib at a 7-Year Follow-Up in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer and a BRCA Mutation: The SOLO1/GOG 3004 Trial. J Clin Oncol, 2023. 41(3): p. 609-617.

- Fong, P.C., et al., Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med, 2009. 361(2): p. 123-34.

- Ledermann, J., et al., Olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed serous ovarian cancer: a preplanned retrospective analysis of outcomes by BRCA status in a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2014. 15(8): p. 852-61.

- Mirza, M.R., et al., Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2016. 375(22): p. 2154-2164.

- Coleman, R.L., et al., Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet, 2017. 390(10106): p. 1949-1961.

- Konstantinopoulos, P.A., et al., Germline and Somatic Tumor Testing in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol, 2020. 38(11): p. 1222-1245.

- Colombo, N., J.A. Ledermann, and E.G.C.E.a. clinicalguidelines@esmo.org, Updated treatment recommendations for newly diagnosed epithelial ovarian carcinoma from the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol, 2021. 32(10): p. 1300-1303.

- Vos, J.R., et al., Universal Tumor DNA BRCA1/2 Testing of Ovarian Cancer: Prescreening PARPi Treatment and Genetic Predisposition. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2020. 112(2): p. 161-169.

- Kwon, J.S., et al., Germline Testing and Somatic Tumor Testing for BRCA1/2 Pathogenic Variants in Ovarian Cancer: What Is the Optimal Sequence of Testing? JCO Precis Oncol, 2022. 6: p. e2200033.

- Witjes, V.M., et al., The most efficient and effective BRCA1/2 testing strategy in epithelial ovarian cancer: Tumor-First or Germline-First? Gynecol Oncol, 2023. 174: p. 121-128.

- Casparie, M., et al., Pathology databanking and biobanking in The Netherlands, a central role for PALGA, the nationwide histopathology and cytopathology data network and archive. Cell Oncol, 2007. 29(1): p. 19-24.

- Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL), About the NCR. 2022.

- Tew, W.P., et al., PARP Inhibitors in the Management of Ovarian Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol, 2020. 38(30): p. 3468-3493.

- Federatie Medisch Specialisten, Informatie en informed consent moleculaire tumordiagnostiek. 2023.

- Cree, I.A., et al., Revising the WHO classification: female genital tract tumours. Histopathology, 2020. 76(1): p. 151-156.

-

Kwaliteitsstandaard Organisatie van moleculaire pathologie diagnostiek in de oncologie. 2023.

- Baranov, N.S., et al., Synoptic reporting increases quality of upper gastrointestinal cancer pathology reports. Virchows Arch, 2019. 475(2): p. 255-259.

- Sluijter, C.E., et al., The effects of implementing synoptic pathology reporting in cancer diagnosis: a systematic review. Virchows Arch, 2016. 468(6): p. 639-49.

- Snoek, J.A.A., et al., The impact of standardized structured reporting of pathology reports for breast cancer care. Breast, 2022. 66: p. 178-182.

- Janikova, K., et al., Small-scale variants and large deletions in BRCA1/2 genes in Slovak high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Pathol Res Pract, 2023. 246: p. 154475.

- Jones, M.A., et al., The landscape of BRCA1 and BRCA2 large rearrangements in an international cohort of over 20 000 ovarian tumors identified using next-generation sequencing. Genes Chromosomes Cancer, 2023. 62(10): p. 589-596.

- Petrij-Bosch, A., et al., BRCA1 genomic deletions are major founder mutations in Dutch breast cancer patients. Nat Genet, 1997. 17(3): p. 341-5.

- Neveling, K., et al., BRCA Testing by Single-Molecule Molecular Inversion Probes. Clin Chem, 2017. 63(2): p. 503-512.

- Zakrzewski, F., et al., Targeted capture-based NGS is superior to multiplex PCR-based NGS for hereditary BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene analysis in FFPE tumor samples. BMC Cancer, 2019. 19(1): p. 396.

- Hung, S.S., et al., Assessment of Capture and Amplicon-Based Approaches for the Development of a Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Pipeline to Personalize Lymphoma Management. J Mol Diagn, 2018. 20(2): p. 203-214.

- Bosdet, I.E., et al., A clinically validated diagnostic second-generation sequencing assay for detection of hereditary BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. J Mol Diagn, 2013. 15(6): p. 796-809.

- Ballester, L.Y., et al., Advances in clinical next-generation sequencing: target enrichment and sequencing technologies. Expert Rev Mol Diagn, 2016. 16(3): p. 357-72.

- Samorodnitsky, E., et al., Evaluation of Hybridization Capture Versus Amplicon-Based Methods for Whole-Exome Sequencing. Hum Mutat, 2015. 36(9): p. 903-14.

- Mertes, F., et al., Targeted enrichment of genomic DNA regions for next-generation sequencing. Brief Funct Genomics, 2011. 10(6): p. 374-86.

- Kramer, C., et al., Causality and functional relevance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants in non-high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas. J Pathol, 2024. 262(2): p. 137-146.

- Hennessy, B.T., et al., Somatic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 could expand the number of patients that benefit from poly (ADP ribose) polymerase inhibitors in ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2010. 28(22): p. 3570-6.

- Commissie Richtlijnen Gynaecologische Oncologie (CRGO), Richtlijn Erfelijk en familiar ovariumcarcinoom. 2022.

- Commissie Richtlijnen Gynaecologische Oncologie (CRGO), Richtlijn Erfelijk en familiar ovariumcarcinoom. 2015.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).