The application of the precision medicine approach in cancer has been enhanced by the availability of new biomedical and informatics technologies that have enabled thorough genomic analysis of the tumor by means of Next Generation sequencing (NGS) (1). Several gene mutations have been associated with individualized therapy, allowing for a more personalized approach depending on the features of each patient's tumor (2). In the era of targeted therapy, efficient cancer care requires the utilization of biomarkers which may advise prognosis, diagnosis, and disease monitoring, in addition to treatment selection. Therefore, predictive biomarkers are presently employed successfully in a variety of tumor types in which specific therapy protocols target inherited or somatic genetic abnormalities (3)Compared to nonselective therapeutic treatments, gene-directed treatment techniques have been found to provide superior clinical effects for several malignancies.

Several tumor types have shown responses in inhibitors of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), a class of proteins involved in DNA repair pathways. Therefore, PARP Inhibitors (PARPi) are approved in ovarian, breast, prostate, and pancreatic cancers. However, it appears that this therapy is not effective in all tumor types, but is associated with specific tumor characteristics, particularly abnormalities in the DNA repair induced by a defective homologous recombination (HR) pathway (4).

The use of PARPi exploits the phenomena of synthetic lethality, in which the presence of a specific genetic event is tolerated for cell survival, but the co-occurrence of concurrent genetic events leads to cell death. Similarly, the use of PARPi in tumors with a functional HR pathway is tolerable by cancer cells, but it is lethal to cells with abnormalities in this pathway. Multiple proteins are involved in this pathway, with BRCA1 and BRCA2 being the most well-known. Tumors with defective BRCA1/2 genes have shown great sensitivity in such therapy therefore, the first PARPi approval involved ovarian tumors with germline or somatic mutations in these genes. However, the utilization of solely these genes as biomarkers may restrict the number of individuals with potential benefits from this medication. In reality, only 15–25% of ovarian cancers harbor BRCA1/2 alterations, and they are even rarer in other tumor types(5)

Consequently, the term homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) has been utilized to describe the incapacity of a cell to utilize the HR pathway to repair its damage, resulting in an accumulation of double breaks in the DNA helix (1). Patients who are likely to respond positively to PARP inhibitors can be identified using methodologies developed to determine the HRD status of the tumor. However, there are substantial discrepancies in the procedures currently used for this scope, and further study is necessary to evaluate their clinical efficacy (6).

Inactivation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mainly through somatic mutations is observed in several hereditary and sporadic cancers, a phenomenon referred to as 'BRCA-ness'. However, epigenetic changes and mutations in several other genes implicated in the HR pathway, such as the Fanconi anemia genes and the ARID1A, ATM, ATRX, BAP1, BARD1, BLM, BRIP1, CHEK1/2, MRE11A, NBN, PALB2, RAD50, RAD51, WRN, may be responsible for the presence of HRD (7). A series of genetic changes, including gametic mutations in BRCA1/2, intratumoral BRCA1/2 mutations, BRCA1 promoter methylation, and possibly other genetic causes, may indicate loss of homologous recombination function in at least 50% of patients with ovarian cancer, according to TCGA data. Therefore, alterations in other genes of the HR pathway have been exploited as biomarkers of PARPi treatment, with ambiguous results in the majority of tumor types (8).

Analysis of the BRCA1/2 and/or other HR genes’ mutational status offers a direct way to investigate the cause of HRD in cancer cells. The existence of certain genomic scars in the tumor, suggesting underlying genomic instability, might be analyzed as a second method for assessing the impact of such abnormality on the genome. The genomic and transcriptome characteristics associated with the HRD phenotype, as well as functional tests such as the identification of RAD51 foci, have been developed to assess HRD consequences following a cell's exposure to a DNA damaging agent (9)

The most common genomic scar assays reported to date are the analysis of the percentage of genomic regions with LOH or the combined use of LOH, telomeric allelic imbalance (TAI), and large-scale transitions (LSTs), giving rise to a GI score (10)Two GI commercial tests have been extensively evaluated in clinical trials the FoundationOne CDx LOH determined through tumor single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) sequencing and the myChoice HRD test (Myriad Genetics) using a GI score derived from the unweighted sum of NtAI, LST, and LOH. In the first case, a tumor is considered HRD positive if %LOH is >16% and/or a BRCA1/2 mutation is detected. For the Myriad test, positivity is consistent with a GIS score >42 and/or BRCA1/2 somatic mutation. The clinical benefit of genomic scars analysis has been proven in several clinical trials using LOH independently or in combination with LST and TAI, indicating their utility as predictive biomarkers of response to platinum-based treatment and PARPi in the context of breast and ovarian cancer. The best predictive value derives by combining the evaluation of genomic instability with tumor BRCA mutation analysis (11).

Several alternative assays that measure the HRD status for treatment decision-making have also been developed. These include NGS assays measuring LOH and or GIS, as well as genotyping arrays that evaluate SNPs, and provide a viable alternative for HRD computation. However, many of these assays are elaborate, utilizing various molecular methodologies and data processing algorithms, while various cutoffs are used to evaluate the HRD status (1). This lack of standardization among HRD tests emphasizes the significance of comparing existing testing methodologies.

The aim of the study was to investigate the utility of an NGS multigene panel for the analysis of mutations in genes of the homologous recombination (HR) pathway as well as loss of heterozygosity (LOH), as predictors of treatment response. The LOH data obtained were compared to those obtained using the Affymetrix OncoScan™ Assay, which is a SNP-array based on molecular inversion probe technology, a proven technology for identifying CNVs and LOH.

Material and Methods

Patients and DNA Extraction

In the present study, 483 metastatic cancer patients referred by their treating oncologist for extensive molecular profile analysis between 01/01/2022 and 31/6/2022 were included. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

DNA was extracted from the sample under investigation using the the MagMAX™ FFPE DNA/RNA Ultra Kit which is designed for the sequential isolation of DNA and RNA from the same formaldehyde- or paraformaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sample. Available FFPE tumor blocks were subjected to histological review by an pathologist to evaluate hematoxylin-eosin stained sections for tumor tissue evaluation as well as tumor cell content (TCC%). The measure of the isolated DNA concentration was obtained by the Qubit fluorometer.

Targeted Next Generation Sequencng Assay

An amplicon-based targeted NGS assay, the Oncomine Comprehensive Assay Plus (Thermo Fisher) was used for the analysis of 513 genes associated with targeted and immuno-oncology therapies with standard protocols, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This assay detects relevant SNVs, indels, CNVs, gene fusions, splice variants in addition to TMB and MSI simultaneously. Sequencing was carried out using the Next Generation Sequencing platform Ion GeneStudio S5 Prime System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Consequently, the Oncomine Comprehensive Plus - w2.3 - DNA - Single Sample Ion Reporter Workflow (v5.18) was applied to automatically annotate identified variants. This assay measures genomic instability using sample-level LOH in addition to the analysis for 31 HR-related gene alterations (Supplementary Table1). The algorithm utilizes heterozygous population SNPs covered by the assay to determine the ploidy levels of genomic segments. The genome is divided into contiguous segments of similar ploidy levels. Log odds ratios for variant allele frequency of observed population SNPs and copy number (CN) ratios for each segment are calculated. Log odds ratio and CN ratios are then used to infer tumor cellularity (i.e., percentage of the tumor cells in the sample) and Loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) for each genomic segment. Segment-level LOH events are intersected with targeted gene boundaries to determine LOH events in selected genes. Segment level LOH events are also aggregated to determine sample level % LOH.

Furthermore, the analysis software Sequence Pilot (version 4.3.0, JSI medical systems, Ettenheim, Germany) was also used for variant annotation.

OncoScan CNV Assay (ThermoFisher)

Genomic DNA was extracted from the FFPE tumor tissue. Subsequently, hybridization was carried out on the OncoScan™ CNV Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The Chromosome Analysis Suite (ChAS) was used for the primary analysis of the CEL files and quality control calculations (MAPD, ndSNPQC). ASCAT (v3.0.0) (allele-specific copy number analysis of tumors), ((12), (13) using logR ratio and B-allele frequency of autosomal markers with GC content and replication timing correction, was used to evaluate and calculate tumor purity, ploidy, and allele-specific copy number profiles. Segmentation data from ASCAT, along with the previously described algorithms ((14)) and definitions were used to calculate the %LOH ((15))

Results

Tumor Types Analyzed and HR Gene Mutations Distribution

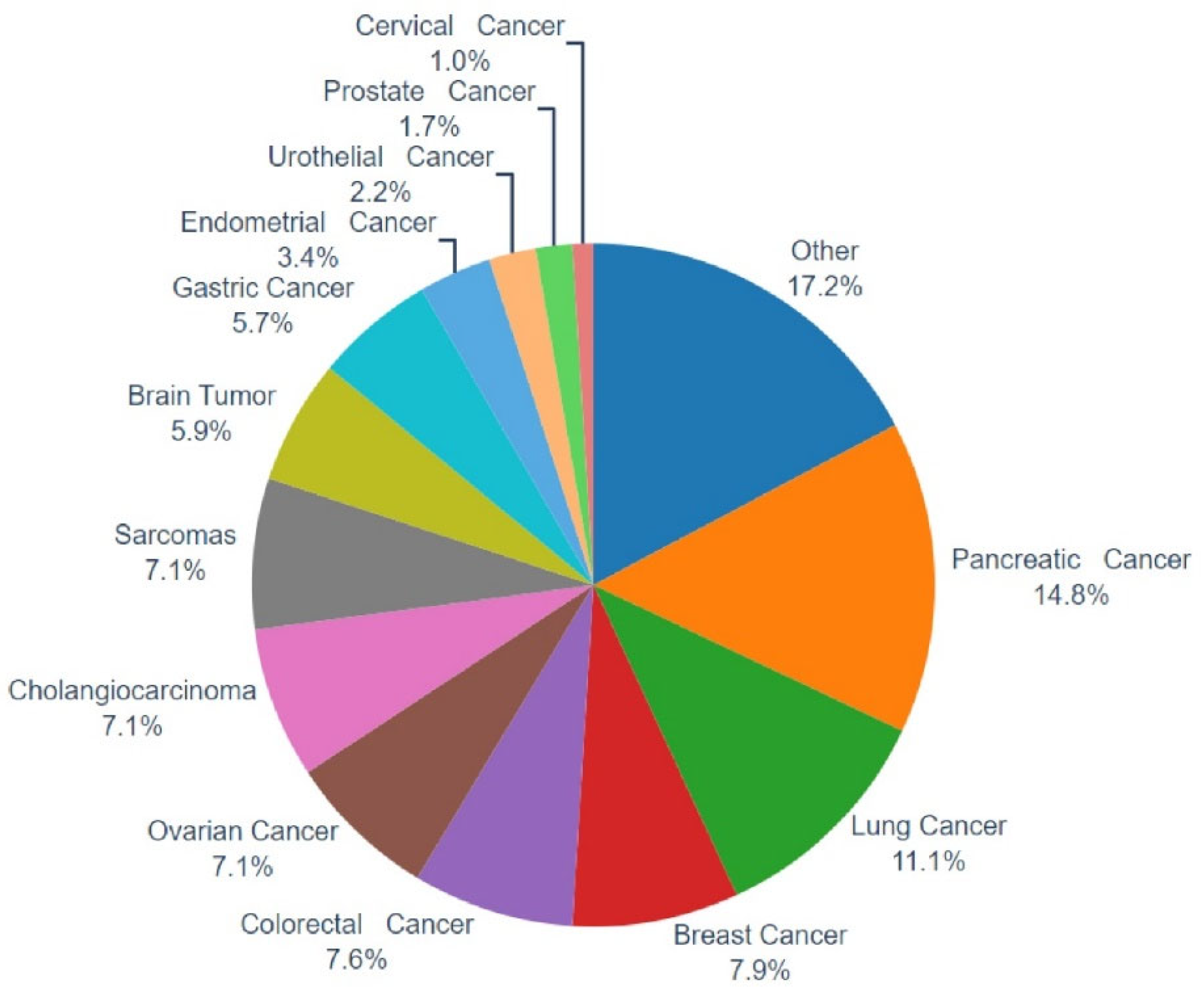

In the present work, a multigene NGS approach was employed to examine the molecular profile of 483 tumors, as well as TMB, MSI, and genomic LOH. Of those, in 406 cases evaluable tumor molecular profile analysis and LOH measurements were obtained, while in 77 cases (15.94%), the computation of %gLOH was not possible due to sample inadequacy for the measurement of such value by the NGS assay used. Various tumor histological types were investigated, including common tumor types such as lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer, as well as difficult-to-treat malignancies such as pancreatic, ovarian, brain, sarcomas, and cholangiocarcinoma, among others (

Figure 1).

A mutation in a gene involved in the homologous recombination (HR) pathway was detected in 20.93% of the tumors analyzed (85/406), with BRCA1/2 genes being the most prevalent HR altered genes detected in 5.17% (21/406) of the tumors. Tumors harboring BRCA1/2 mutations included ovarian (6/30, 20%), breast (3/32, 9.37%), pancreatic (1/60, 1.66%), colon (4/31, 12.90%), lung (2/45, 4.44%), biliary track (1/29, 3.44%), endometrial (1/13, 7.69%), adrenal gland (1/2, 50%) and tumors of unknown primary (2/19, 10.52%). Furthermore, a mutation in any of the others HR genes was identified in 15.76% (64/406) of the cases. Most of the non-BRCA1/2 HR mutations were in ARID1A (4.18%), ATRX (2.21%), and ATM (1.97%) genes. Among cancers with PARPi approval, the HR mutation rates were 27.58% for ovarian cancer, 25.00% for breast cancer, 28.57% for prostate cancer, and 10.00% for pancreatic cancer. However, HR mutations were also found in the vast majority of tumor types studied, with lung, colorectal, and cholangiocarcinoma showing the highest HR mutation rates (15.55%, 22.58%, and 27.58%, respectively).

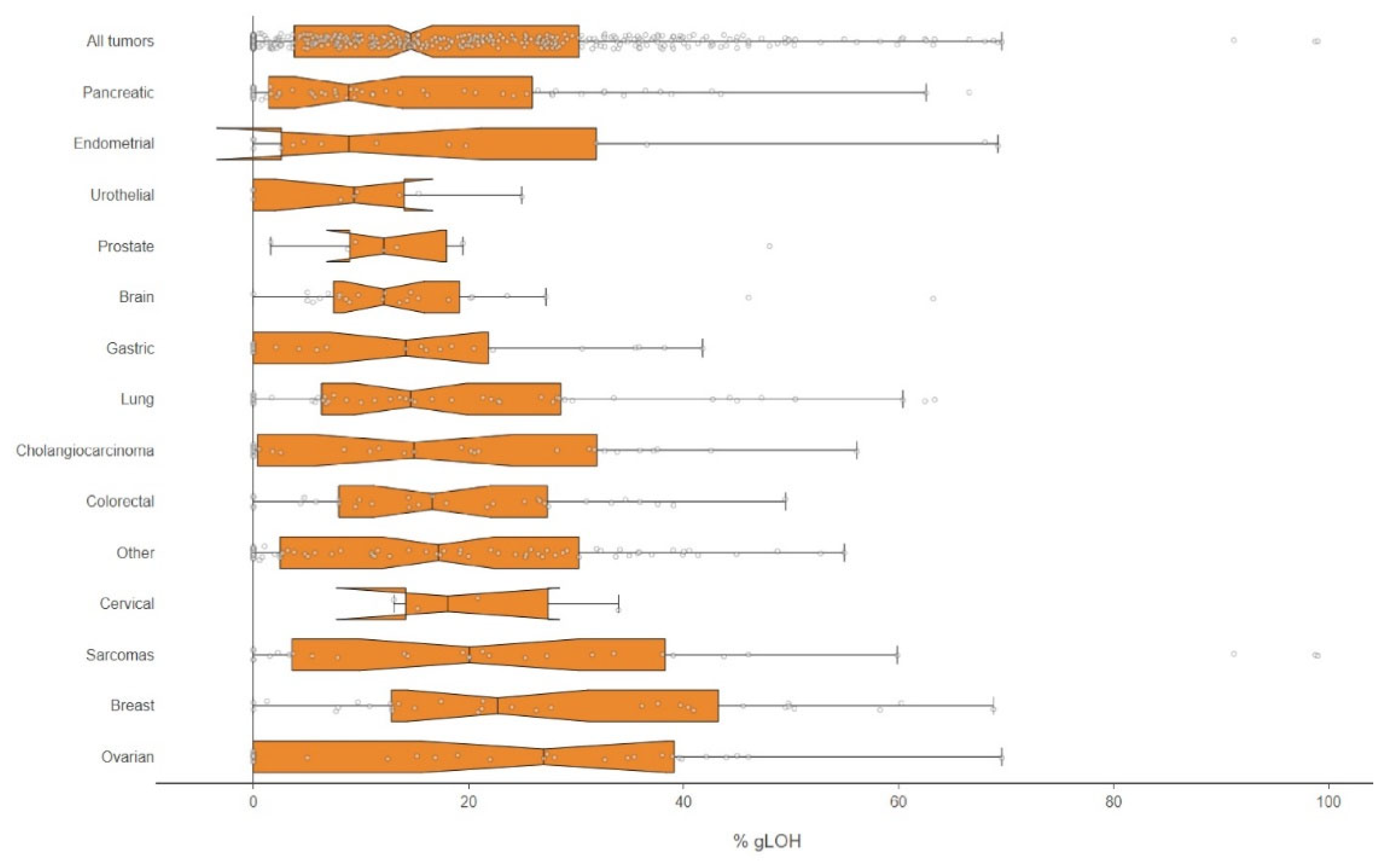

%LOH Analysis by NGS

In addition to HR mutation analysis, the LOH status was also evaluated by the NGS methodology applied. In total, 47.29% (192/406) of the samples examined had a high %LOH value and the median %LOH for all tumors with evaluable results was 14.62%, with the highest median values observed in ovarian cancer (27.00), breast cancer (22.70), and sarcomas (20.08), while the lowest values were seen in pancreatic (8.86)

(Figure 2).

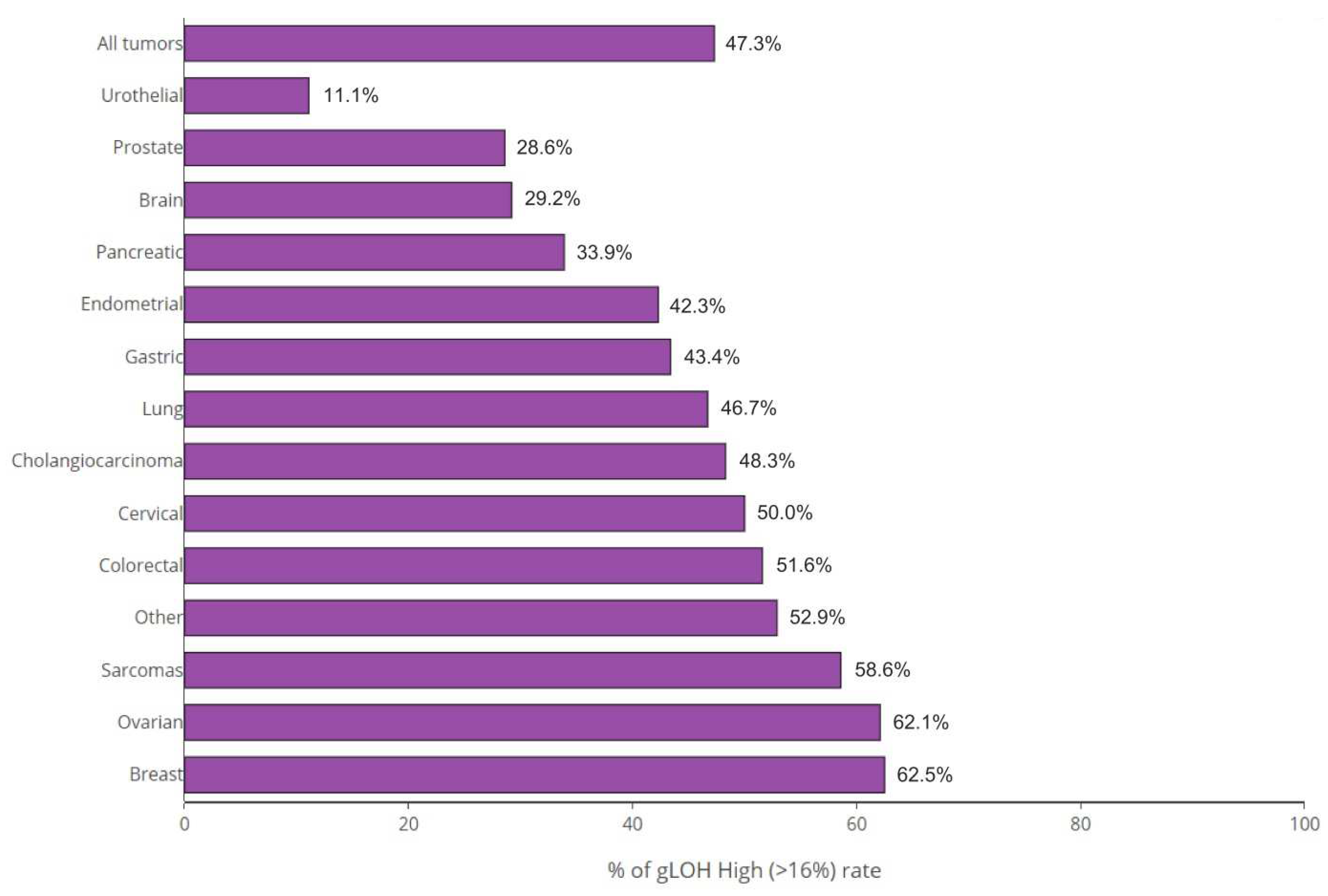

The highest rate of %gLOH positivity was observed in breast tumors, where a %LOH level over the threshold was detected in 62.50% of cases, followed by ovarian, sarcomas, and colon cancer, in which positive values were detected in 62.07%, 58.62%, and 51.61%, of cases correspondingly. On the other hand, urothelial cancer (at a rate of 11.11%), prostate cancer (at a rate of 28.57%), and brain tumors (at a rate of 29.17%) exhibited the lowest positivity rates among tumors

(Figure 3).

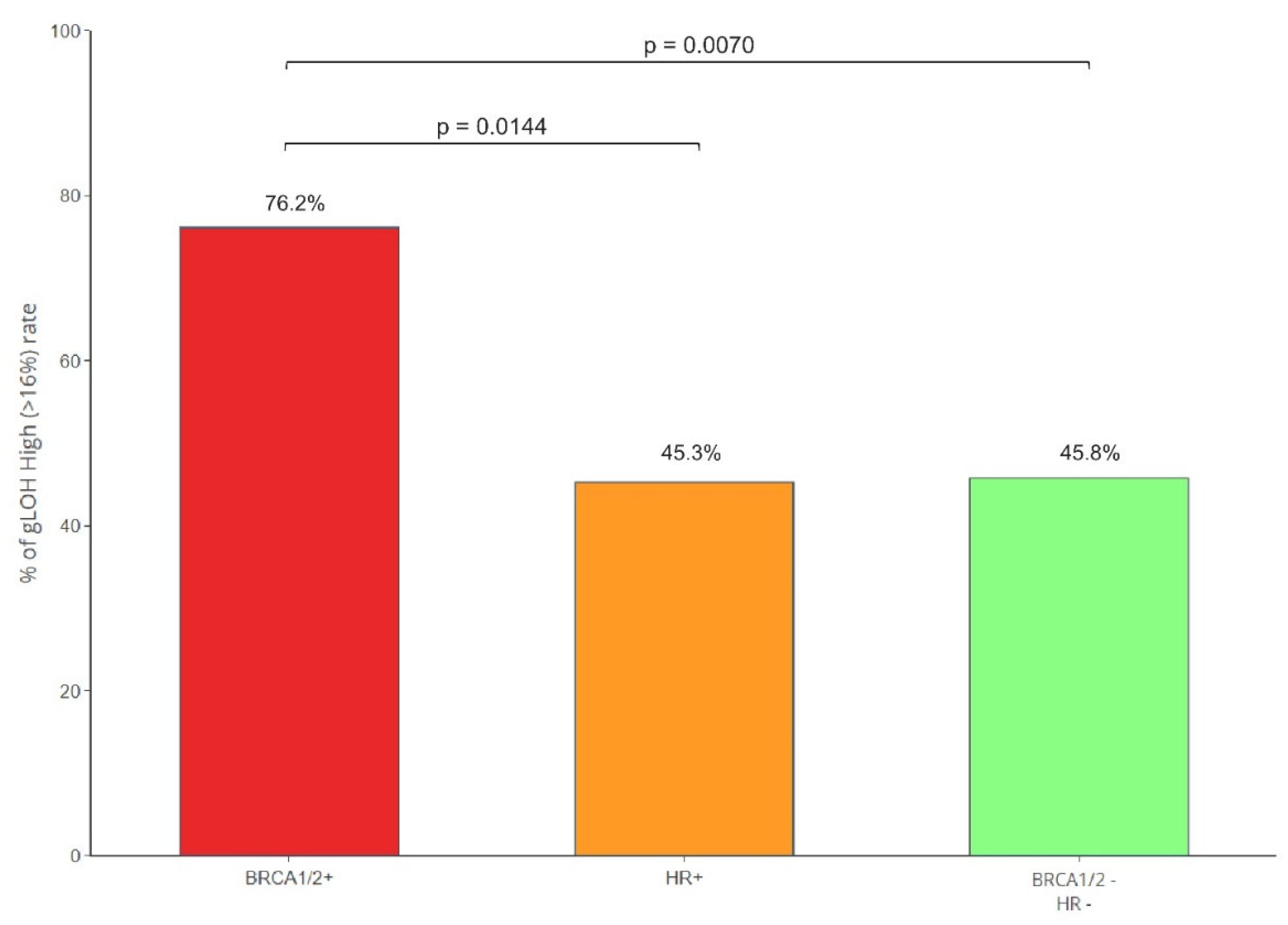

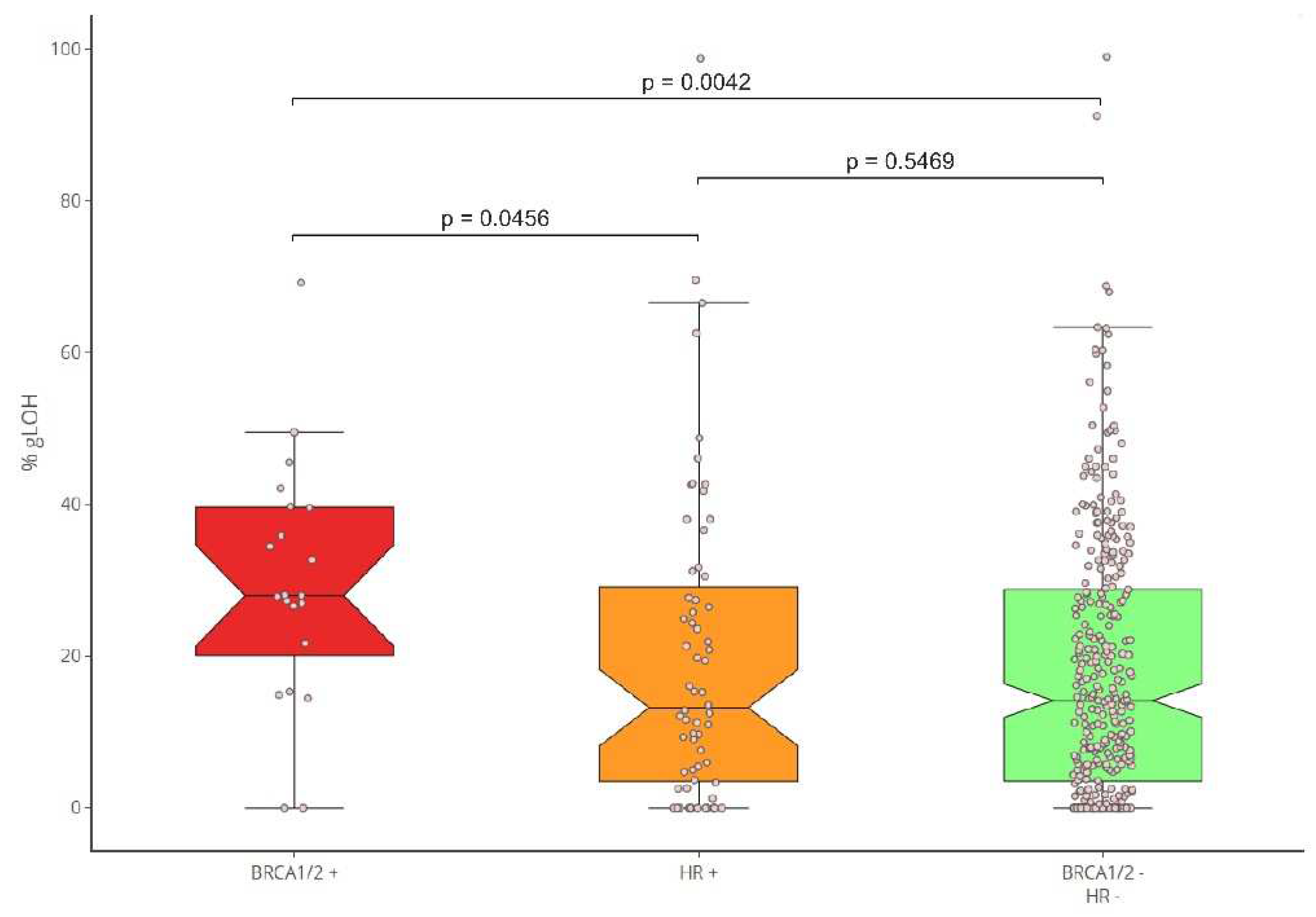

Moreover, the correlation between the presence of HR mutations and the LOH status was evaluated. To achieve this, the LOH levels of BRCA1/2-positive cancers in comparison to those bearing mutations in additional HR genes (HR+/BRCA1/2-), and the HR-negative samples were calculated. %gLOH was highly correlated with the presence of mutations in the BRCA1/2 genes since 76.19% (16/21) of the tumors harboring such alterations had a high %gLOH value (p=0.007). The LOH association was stronger for BRCA1 compared to BRCA2 mutated tumors (p=0.0152 versus 0.2416). However, in all 9 BRCA1/2 mutated ovarian and breast tumors, a high LOH value was detected, indicating a stronger association for both genes with LOH positivity in these tumor types.

Additionally, no association of LOH with other HR genes was identified, as only 45.31% (29/64) of non-BRCA1/2, HR-positive tumors had a high %LOH value, similar to the percentage of 45.79% (147/321) reported in HR-negative tumors (p < .10). (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

b: %gLOH positivity rates per HR status.

Figure 4.

b: %gLOH positivity rates per HR status.

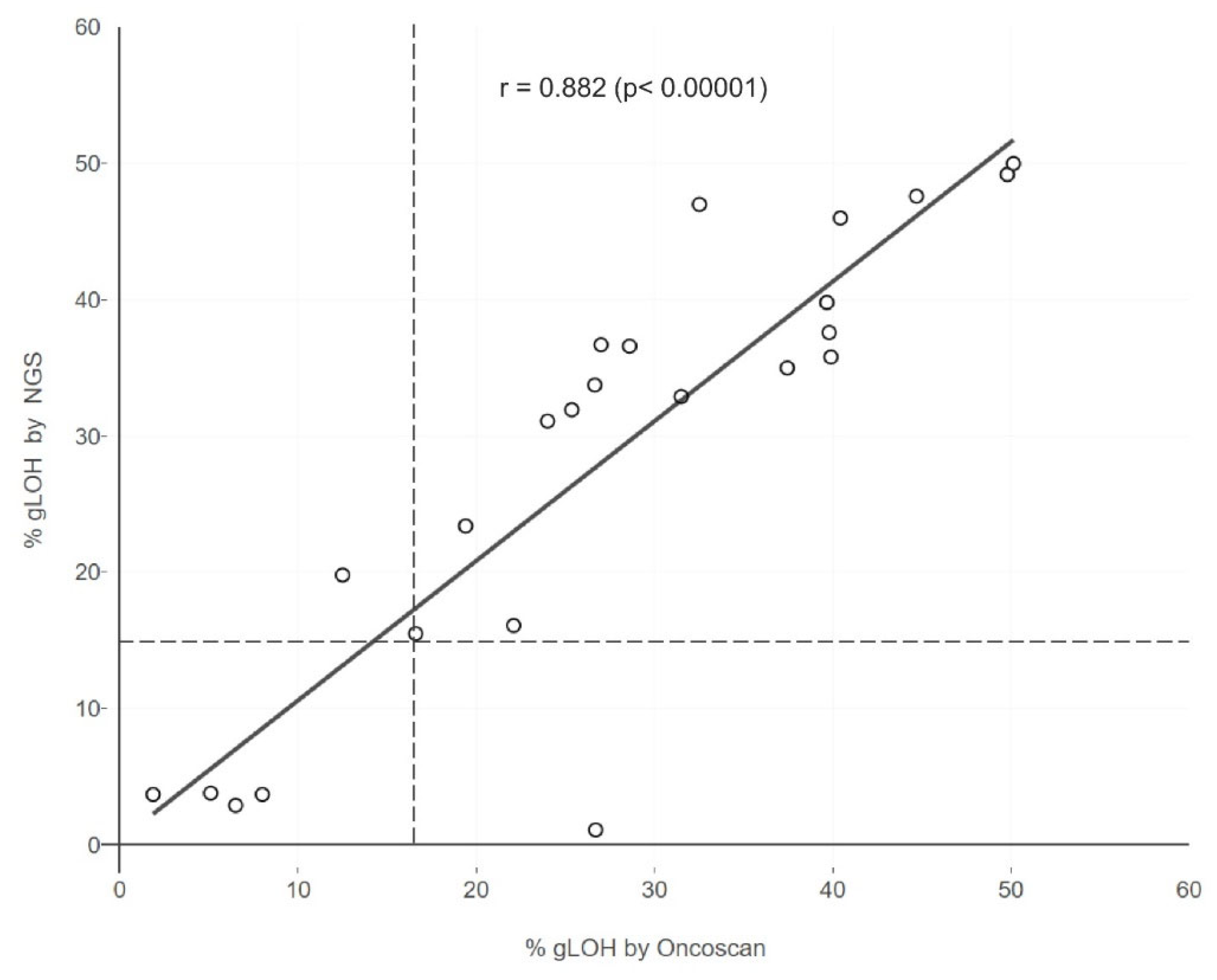

Concordance of %LOH Analysis Results by Two Methodologies

In addition, in order to evaluate the performance of the NGS technique used in the calculation of %LOH, a comparison was conducted between the results obtained with NGS and those generated with the Oncoscan SNP array assay, a gold standard method for LOH computation. Lin's Concordance Correlation Coefficient was 0.87 for the 24 evaluable samples examined simultaneously by both assays

(Figure 5). This indicates the validity of the results acquired using the NGS methodology employed.

Correlation of gLOH with Mutation Status and Immunotherapy Biomarkers

Moreover, the correlation of LOH with other molecular biomarkers such as non-HR gene alterations, TMB and MSI was also assessed. In 402 samples a TMB value was also available, with a median TMB of 4.75 Mut/Mb. 15.87% of the LOH high samples had a high TMB value (>=10mut/megabase), compared to 10.79% in the LOH low group. Thus in accordance with previous studies, there was no association between gLOH and TMB (p=0.1398).

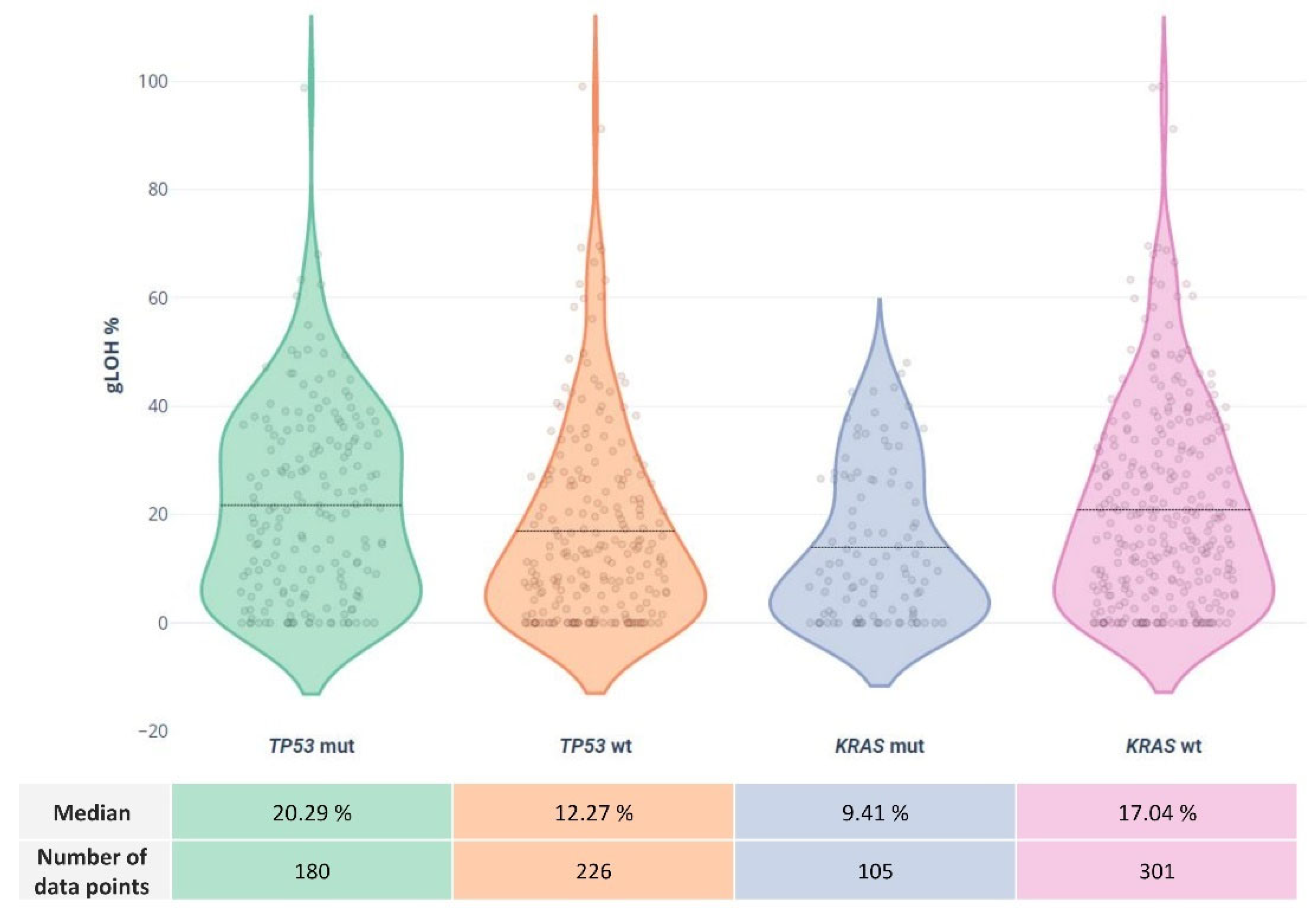

Concerning alterations in other non-HR genes, a high mutation rate of 44.35% was observed for the TP53 gene, followed by KRAS mutations at a rate of 25.86%. Other commonly altered genes included PIK3CA (7.63%), APC (7.14%), TERT (5.91%), NRAS (5.42%), and SMAD4 (5.17%).

The LOH status was highly correlated to

TP53 and

KRAS status. Of the 192 LOH-High samples, 53.12% were also positive for

TP53 mutations compared to 37.38% of the LOH low cases (p=0.0019). In addition,

KRAS variations showed a statistically significant association with lower %LOH values, since a

KRAS mutation rate of 19.27% was observed among the high LOH group vs 31.77% among the low LOH group (p=0.0045). These results are in accordance with recent research showing an association between the presence of

TP53 and

KRAS gene alterations and high LOH values ((16)). No other gene mutations seemed to be correlated with the LOH value of the tumor sample in our cohort

(Figure 6). Moreover, as previously reported, the 5 MSI high samples in our cohort were additionally characterized by high TMB and low LOH levels, indicating a negative MSI-LOH correlation.

Discussion

In the present study an NGS panel including 513 DNA genes, was used for the analysis of alterations in genes of the HR pathway as well as for the evaluation of the LOH status in various tumor types.

In our study, at least 1 HR gene alteration was identified in 20.93% of the cases, with BRCA1/2 genes being the prevalent HR mutated genes, concerning in 24.70% of HR mutation-positive cases. In accordance with previous studies, a high rate of HR mutations was detected in ovarian, breast, and prostate cancers (27.58%, 25.00%, 28.50%), which is consistent with the PARPi approval in these tumor types. Moreover, other tumor types such as lung colorectal and cholangiocarcinoma also exhibit high rates of HR mutations (15.55%, 22.58%, and 27.58%, respectively) while the lowest HR mutation frequency was observed in pancreatic and brain tumors (10.00% and 12.50% respectively). The pan-cancer presence of HR gene alterations indicates that the use of such genes as biomarkers of platinum and PARPi treatments should be evaluated in a wider range of tumor types. However, the modest mutation rate of some of these genes makes their contribution to PARPi sensitivity unclear, whereas for others clinical evidence is beginning to emerge in a variety of cancer histologies.

For example, an HR gene with sustained association with PARPi sensitivity is PALB2. In patients with pancreatic, ovarian, prostate, and breast cancer harboring PALB2 mutations, the clinical benefit to PARPi observed in various studies approaches the one typically seen for BRCA-altered tumors. In a recent study of metastatic breast cancer patients treated with olaparib, responses were only seen in patients with alterations in the PALB2 and those with somatic BRCA1/2, but not those with alterations in low-risk genes such as CHEK2 and ATM (17). RAD51C and RAD51D genes have also shown high evidence of association with PARPi. In, a post hoc exploratory biomarker analysis of pre- and post-platinum samples of the ARIEL2 trial, RAD51C and RAD51D mutations were associated with similar sensitivity to rucaparib as the BRCA1/2 alterations (18). However, these gene alterations have significantly reduced mutation rates, rendering difficult the evaluation of their predictive value. PALB2 alterations for example have been identified in 2 of the 406 tumors tested (with probable germline origin), while in only one case a RAD51C alteration was detected. Likewise, none of the five HGOC patients with biallelic deletion of BRIP1 who were included in the ARIEL2 trial showed an objective response, and two had platinum-resistant/refractory illness at admission (19).

Nevertheless, the sensitivity to PARPi of patients with mutations in other HR genes remains undefined. In addition to BRCA1/2, alterations in 15 other HR genes have been FDA-approved as biomarkers for Olaparib treatment in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). The approval was based on the results obtained from the phase III PROFOUND study, evaluating the effectiveness and safety of the PARPi olaparib compared with antiandrogen treatment. However, response rates were inconsistent and much lower in individuals with HR mutations other than BRCA, resulting in EMA approval of Olaparib solely for patients with BRCA1/2 mutations. In numerous phase II and III clinical studies (20) little or no response to multiple PARPi was reported in diverse tumor types carrying HR mutations in genes such as CHEK2, ATM, FANCA, and CDK12. Nonetheless, more research into the role of other HR genes on treatment sensitivity is required. In PrCa, for instance, biallelic loss of ATM is linked with enhanced responsiveness to PARP inhibitors (21)

Moreover, in several cases, HR gene mutations have been associated with another biomarker of PARPi sensitivity, the presence of LOH.

In several tumor types, particularly breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancer, a strong correlation was observed between increased gLOH and biallelic alterations in other HR genes beyond BRCA1 and BRCA2, including BARD1, PALB2, FANCC, RAD51C, and RAD51D. In contrast, monoallelic/heterozygous alterations in HR genes were not associated with elevated gLOH (16). Moreover, gLOH has also been associated with non-HR gene alterations such as TP53 loss and KRAS gene alterations. This has also been observed in our cohort. However, in a significant subset of tumors, the causative effect of PARPi sensitivity cannot be identified by gene mutation analysis. Thus, the analysis of genomic scars generated due to HR deficiency has emerged as a valuable biomarker of PARPi sensitivity capable to detect additional patients eligible for this treatment without apparent HR defects through direct analysis of gene alterations.

In this study a multigene NGS panel was used, giving the possibility of parallel analysis of gene alterations and the percentage gLOH in various tumor types. 47.29% of the samples analyzed exhibited increased %LOH, indicating the possible use of PARPi in a wider range of tumor types. The LOH positivity prevalence varied among tumor types, with the breast exhibiting the highest positivity rate followed by ovarian tumors and sarcomas and (62.50%, 62.07% and 58.62% respectively). On the opposite, the lowest percentage of %gLOH positivity was observed in urothelial tumors (11.11% of the cases). Moreover, pancreatic, and prostate cancers, two tumors with PARPi approval and HR mutations present, exhibited low %LOH, with positivity rates being 35.00% and 28.57% respectively. This is in agreement with other studies showing variable GIS scores and LOH values in these tumor types, which could impact treatment sensitivity (22,23). However, the magnitude of LOH impact on PARPi sensitivity still remains unclear.

High LOH was not correlated to HR mutation detection, since high LOH values were also present in 45.31% of the tumors without HR gene alterations and in 45% of HR mutation-positive cases. In contrast, BRCA1/2 mutations were strongly associated with increased LOH value, as 76.19% of BRCA1/2-positive cases exhibited a high %LOH. BRCA1/2 alterations are identified in various malignancies. Similarly, in our cohort, BRCA1/2 mutations were present in tumors without PARPi approval, such as endometrial, lung, colon, and biliary tract tumors, as well as in a case of a tumor of unknown primary origin. However, only in half of these cases a high LOH value was also present, which could result in reduced PARPi sensitivity. For example, in the SAFIR02-BREAST study evaluating patients with metastatic Breast cancer, in BRCA1/2 carriers treated with Olaparib, a much higher benefit from treatment was achieved when a high BRCA LOH or GIS score was also present (HR=0.32)(24) .

Previous studies have shown the association of LOH with increased sensitivity to PARPi. In the ARIEL3 study of rucaparib maintenance treatment versus placebo in the second-line, platinum-sensitive setting, LOH helped distinguish those who benefited from rucaparib, but it was not fully predictive, as 30% of patients without BRCA1/2 alterations and with low LOH had progression-free survival of over one year, compared to 5% in the placebo group (25).

In addition, a comparison of the employed NGS methodology and the Oncoscan SNP array assay, a method with demonstrated validity for LOH calculation, revealed an almost perfect agreement between the two methods in the 24 samples examined (Lin's Concordance Correlation Coefficient = 0.87). However, a previous study showed moderate concordance between %LOH and the GIS results obtained by all three types of genomic scars (LOH+LST+TAI). Based on these results, the comparison between %LOH and Myriad's GIS at the threshold of 42 revealed a percentage of positive agreement between MyChoice GIS and %LOH of 64.9% in the 3,336 commercial ovarian cancer samples and 82.5% in the 176 ovarian cancer samples from the SCOTROC4 study (26). These data underline that a degree of overlapping sensitivity exists between these two genomic scar detection methods, but that they cannot be considered equivalent. Despite this, comprehensive NGS assays such as the one used in this study may be useful in providing additional clinically relevant tumor genomic information, since a single analysis provides results related to genomic scars such as LOH along with information concerning the mutational status of important targetable genes, including those of the HR pathways, tumor mutational burden, and microsatellite instability status. Besides such an approach can identify the concomitant presence of LOH and HR mutations in certain cases, which could be a more valuable predictive marker of PARPi sensitivity compared to the analysis of each of these events individually (10)

Furthermore, in our cohort, no statistically significant association was observed in our cohort between LOH and other non-HR gene mutations or high TMB values. This is in agreement with other studies (27).

Conclusions

BRCA1/2 mutations were highly associated with increased LOH value whereas the presence of LOH did not correlate to HR mutations. Additionally, the pancancer presence of HR gene alterations indicates that the use of such genes as biomarkers of platinum and PARPi treatments should be evaluated in a wider range of tumor types. In conclusion the addition of analysis of the gLOH seems to be useful for the detection of additional patients eligible for PARPis.

References

- Pokorska-Bocci A, Stewart A, Sagoo GS, Hall A, Kroese M, Burton H. “Personalized medicine”: what’s in a name? Per Med. 2014 Mar;11(2):197–210. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. Cancer biomarkers for targeted therapy. Biomark. Res. 2019, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toss A, Venturelli M, Peterle C, Piacentini F, Cascinu S, Cortesi L. Molecular Biomarkers for Prediction of Targeted Therapy Response in Metastatic Breast Cancer: Trick or Treat? Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Jan 4;18(1). [CrossRef]

- Buchtel, K.M.; Postula, K.J.V.; Weiss, S.; Williams, C.; Pineda, M.; Weissman, S.M. FDA Approval of PARP Inhibitors and the Impact on Genetic Counseling and Genetic Testing Practices. J. Genet. Couns. 2017, 27, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittica G, Ghisoni E, Giannone G, Genta S, Aglietta M, Sapino A, et al. PARP Inhibitors in Ovarian Cancer. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2018 Oct 3;13(4):392–410. [CrossRef]

- How, J.A.; Jazaeri, A.A.; Fellman, B.; Daniels, M.S.; Penn, S.; Solimeno, C.; Yuan, Y.; Schmeler, K.; Lanchbury, J.S.; Timms, K.; et al. Modification of Homologous Recombination Deficiency Score Threshold and Association with Long-Term Survival in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brok, W.D.D.; Schrader, K.A.; Sun, S.; Tinker, A.V.; Zhao, E.Y.; Aparicio, S.; Gelmon, K.A. Homologous Recombination Deficiency in Breast Cancer: A Clinical Review. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2017, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinopoulos, P.A.; Ceccaldi, R.; Shapiro, G.I.; D'Andrea, A.D. Homologous Recombination Deficiency: Exploiting the Fundamental Vulnerability of Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 1137–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Baek, J.Y.; Cha, Y.J.; Ahn, J.B.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, K.-W.; Kim, J.-W.; Chang, W.J.; Park, J.O.; et al. A Phase II Study of Avelumab Monotherapy in Patients with Mismatch Repair-Deficient/Microsatellite Instability-High or POLE-Mutated Metastatic or Unresectable Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 52, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Wiel, A.M.A.; Schuitmaker, L.; Cong, Y.; Theys, J.; Van Hoeck, A.; Vens, C.; Lambin, P.; Yaromina, A.; Dubois, L.J. Homologous Recombination Deficiency Scar: Mutations and Beyond—Implications for Precision Oncology. Cancers 2022, 14, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boros, B.D.; Schoch, K.M.; Kreple, C.J.; Miller, T.M. Antisense Oligonucleotides for the Study and Treatment of ALS. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Loo, P.; Nordgard, S.H.; Lingjærde, O.C.; Russnes, H.G.; Rye, I.H.; Sun, W.; Weigman, V.J.; Marynen, P.; Zetterberg, A.; Naume, B.; et al. Allele-specific copy number analysis of tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 16910–16915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross EM, Haase K, Van Loo P, Markowetz F. Allele-specific multi-sample copy number segmentation in ASCAT. Cowen L, editor. Bioinformatics [Internet]. 2021 Jul 27;37(13):1909–11. 1909. [CrossRef]

- Imanishi, S.; Naoi, Y.; Shimazu, K.; Shimoda, M.; Kagara, N.; Tanei, T.; Miyake, T.; Kim, S.J.; Noguchi, S. Clinicopathological analysis of homologous recombination-deficient breast cancers with special reference to response to neoadjuvant paclitaxel followed by FEC. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 174, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abkevich, V.; Timms, K.M.; Hennessy, B.T.; Potter, J.; Carey, M.S.; Meyer, L.A.; Smith-McCune, K.; Broaddus, R.; Lu, K.H.; Chen, J.; et al. Patterns of genomic loss of heterozygosity predict homologous recombination repair defects in epithelial ovarian cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 1776–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphalen CB, Fine AD, André F, Ganesan S, Heinemann V, Rouleau E, et al. Pan-cancer Analysis of Homologous Recombination Repair–associated Gene Alterations and Genome-wide Loss-of-Heterozygosity Score. Clinical Cancer Research. 2022 Apr 1;28(7):1412–21. [CrossRef]

- Tung, N.M.; Robson, M.E.; Ventz, S.; Santa-Maria, C.A.; Nanda, R.; Marcom, P.K.; Shah, P.D.; Ballinger, T.J.; Yang, E.S.; Vinayak, S.; et al. TBCRC 048: Phase II Study of Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer and Mutations in Homologous Recombination-Related Genes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 4274–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swisher, E.M.; Kwan, T.T.; Oza, A.M.; Tinker, A.V.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Oaknin, A.; Coleman, R.L.; Aghajanian, C.; Konecny, G.E.; O’malley, D.M.; et al. Molecular and clinical determinants of response and resistance to rucaparib for recurrent ovarian cancer treatment in ARIEL2 (Parts 1 and 2). Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan Coyne G, Karlovich C, Wilsker D, Voth AR, Parchment RE, Chen AP, et al. PARP Inhibitor Applicability: Detailed Assays for Homologous Recombination Repair Pathway Components. Onco Targets Ther. 2022;15:165–80.

- De Bono, J.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira, S.; Porta, N.; Arce-Gallego, S.; Seed, G.; Llop-Guevara, A.; Bianchini, D.; Rescigno, P.; Paschalis, A.; Bertan, C.; Baker, C.; et al. Biomarkers Associating with PARP Inhibitor Benefit in Prostate Cancer in the TOPARP-B Trial. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 2812–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco-Barcia, V.; Muñoz, A.; Castro, E.; Ballesteros, A.I.; Marquina, G.; González-Díaz, I.; Colomer, R.; Romero-Laorden, N. The Homologous Recombination Deficiency Scar in Advanced Cancer: Agnostic Targeting of Damaged DNA Repair. Cancers 2022, 14, 2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotan, T.L.; Kaur, H.B.; Salles, D.C.; Murali, S.; Schaeffer, E.M.; Lanchbury, J.S.; Isaacs, W.B.; Brown, R.; Richardson, A.L.; Cussenot, O.; et al. Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) score in germline BRCA2- versus ATM-altered prostate cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2021, 34, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andre, F.; Filleron, T.; Kamal, M.; Mosele, F.; Arnedos, M.; Dalenc, F.; Sablin, M.-P.; Campone, M.; Bonnefoi, H.; Lefeuvre-Plesse, C.; et al. Genomics to select treatment for patients with metastatic breast cancer. Nature 2022, 610, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, R.L.; Oza, A.M.; Lorusso, D.; Aghajanian, C.; Oaknin, A.; Dean, A.; Colombo, N.; Weberpals, J.I.; Clamp, A.; Scambia, G.; et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1949–1961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ngoi NYL, Tan DSP. The role of homologous recombination deficiency testing in ovarian cancer and its clinical implications: do we need it? ESMO Open. 2021 Jun;6(3):100144. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, K.; Wang, H. Loss of heterozygosity related to TMB and TNB may predict PFS for patients with SCLC received the first line setting. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).