1. Introduction

The advent of improved access to next-generation sequencing (NGS) has led to the widespread implementation of cancer genomic testing in both research and clinical settings. While the extent of genomic testing varies among different healthcare systems internationally, it has become increasingly common across multiple cancer types, including lung, thyroid and head/neck cancers [

1,

2,

3]. In hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, particularly in advanced or metastatic settings, the CAPItello-291 trial [

4] demonstrated the efficacy of capivasertib plus fulvestrant for alterations in

PIK3CA and

PTEN, leading to the adoption of genomic testing platforms such as FoundationOne CDx as companion diagnostics in many countries. Furthermore, genomic testing has gained traction in rare cancers, becoming increasingly utilized in clinical practice [

5]. In breast oncology, the emergence of entities such as secretory carcinoma of the breast, which shows a high detection rate of

NTRK fusions and accessibility to TRK inhibitors, has made genomic testing an indispensable tool in breast cancer management [

6].

Phyllodes tumors represent a rare neoplasm, accounting for 0.3-1.0% of breast tumors, with a notably higher prevalence among Asian populations, including Japanese, and Hispanic populations in Latin America [

7,

8,

9]. While the etiology remains largely unknown, some cases have been associated with Li-Fraumeni syndrome [

10] . These tumors often demonstrate resistance to chemotherapy, necessitating aggressive surgical intervention when feasible. When chemotherapy is indicated, treatment typically follows advanced soft tissue sarcoma protocols, commonly employing agents such as adriamycin, ifosfamide, or pazopanib. However, the generally poor response to chemotherapy and limited data on genetic alterations that might guide treatment decisions remain significant challenges. Recent case reports have emerged describing treatments based on genetic testing and protein expression profiles [

11]. A previous comprehensive genomic profiling study of 24 phyllodes tumors revealed a high frequency of

TP53 mutations and identified potentially targetable alterations in some cases, including

KIAA1549-BRAF fusion and

FGFR3-TACC3 fusion, emphasizing the importance of genomic testing [

12].

In this study, we conducted a retrospective analysis of genomic data and treatment outcomes from unresectable advanced phyllodes tumors, utilizing the Center for Cancer Genomics and Advanced Therapeutics (C-CAT) database, Japan's national clinical genomic testing registry. Given the paucity of real-world clinical data on genomic profiles and treatment responses in this rare tumor type, our findings may provide valuable insights for clinical practice. Here, we present our analysis of genomic alterations and their correlation with treatment responses in advanced phyllodes tumors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

This retrospective cohort study analyzed clinical genomic testing results and clinical data from 80,329 patients registered in the C-CAT (Center for Cancer Genomics and Advanced Therapeutics) database between June 1, 2019, and August 2024. The analysis included data from multiple genomic testing platforms [

13] with the following coverage periods:

NCC OncoPanel: June 1, 2019 - August 15, 2024, FoundationOne CDx: June 1, 2019 - August 19, 2024, FoundationOne Liquid CDx: August 1, 2021 - August 17, 2024, Guardant360 CDx: July 24, 2023 - August 16, 2024, GenMineTOP: August 1, 2023 - August 16, 2024.

The database version used for this analysis was 20240820. Patient registration was exclusively conducted through Japanese medical institutions designated by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare as Core Hospitals for Cancer Genomic Medicine, Designated Hospitals for Cancer Genomic Medicine, or Collaborative Hospitals for Cancer Genomic Medicine. Only cases with written informed consent for secondary use of clinical genomic data from their respective institutions were included in the analysis.

This study was conducted with approval from both the Institutional Review Board of Yamagata University Hospital (approval number: 2023-105) and the C-CAT Database Utilization Review Board (approval number: CDU2023-032N).

2.2. Data Collection and Response Analysis

In this retrospective cohort study, we collected comprehensive data including demographic information (age and sex), pathological characteristics (registered histological type and tumor content), and clinical sample information specifying whether the sample was from primary or metastatic sites. We also collected details of pharmacological treatments and their responses, along with lifestyle factors including smoking and alcohol history. Family history of malignancy up to third-degree relatives was also recorded. The evaluation of treatable alterations by Expert Panel was documented; the Expert Panel refers to a specialized committee required by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare for insurance reimbursement, comprising medical oncologists, pathologists, genetic medicine specialists, and bioinformaticians. Additionally, genomic characteristics were collected, including the number of gene calls, tumor mutational burden, microsatellite instability status, and specific genetic alterations identified. The pathogenicity assessment of alterations was conducted by consulting multiple databases, including ClinVar and OncoKB, in conjunction with the Japanese Multi Omics Reference Panel (jMorp). Only variants classified as pathogenic were incorporated into our analysis.

Treatment response was evaluated based on first-line chemotherapeutic treatment outcomes as registered in the database. Physicians at designated institutions are required to classify responses according to RECIST criteria [

14] into one of the following categories: complete response, partial response, stable disease, progressive disease, or not evaluated.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Exploratory statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

3. Results

3.1. Patients Background

The analysis cohort (

Table 1.) comprised 80,329 patients, including 40,447 males, 39,877 females, and 5 patients with unspecified gender. Age distribution analysis revealed that the 70-79 year age group was the largest with 23,252 patients, followed by the 60-69 year age group with 22,630 patients, and the 50-59 year age group with 16,846 patients. Among the registered alterations, TP53 was the most frequently observed with 48,176 cases, followed by

KRAS with 22,344 cases, and

APC with 16,446 cases. According to OncoTree classification, gastrointestinal tumors were the most common with 13,376 cases, followed by pancreatic tumors with 12,207 cases, and biliary tract tumors with 7,010 cases. Breast tumors ranked fourth with 5,229 cases. Within the breast tumor category, phyllodes tumors, a rare entity, accounted for 60 cases (

Table 2.), representing 0.07% of the total cohort and 1.1% of all breast tumors. The median age was 54 years (range: 13-79 years), and all subjects were female. Seven patients had a history of smoking, and four patients reported a history of heavy alcohol consumption. Regarding Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS), 41 patients were classified as PS 0, 14 as PS 1, two as PS 2, and one as PS 3. Family history of malignancy was present in 25 cases.

Specimens submitted for cancer genome profiling were obtained from primary tumors in 35 cases, metastatic lesions in 22 cases, blood samples in three cases, and unknown sources in two cases. Metastases were identified in 57 patients, with pulmonary metastases being most frequent (n=37), followed by bone metastases (n=10) and brain metastases (n=3). Additional metastatic sites were documented in 26 cases, including muscle and pleural involvement.

First-line chemotherapy regimens were documented for 40 patients. Anthracycline-based regimens (including adriamycin + ifosfamide, adriamycin + cyclophosphamide, or single-agent adriamycin) were most commonly administered (n=29), followed by eribulin (n=4). Other agents, including docetaxel and pazopanib, were administered in seven cases.

In accordance with Japanese insurance reimbursement requirements, expert panel reviews of genomic profiling results led to new treatment recommendations in 13 cases. Among these, one patient received pembrolizumab based on high tumor mutational burden and achieved a documented response. However, in the remaining 12 cases, the recommended treatments were not administered due to geographical constraints or patient mortality. No gene-based treatment recommendations were made for 23 cases, and expert panel discussion results were pending for 14 cases.

Microsatellite instability testing was performed in 56 cases (noting that GeneMine TOP and earlier versions of the NCC Oncopanel System did not include microsatellite instability testing capabilities). Of these, 55 cases were classified as microsatellite stable, and one case was deemed indeterminate (

Table 3).

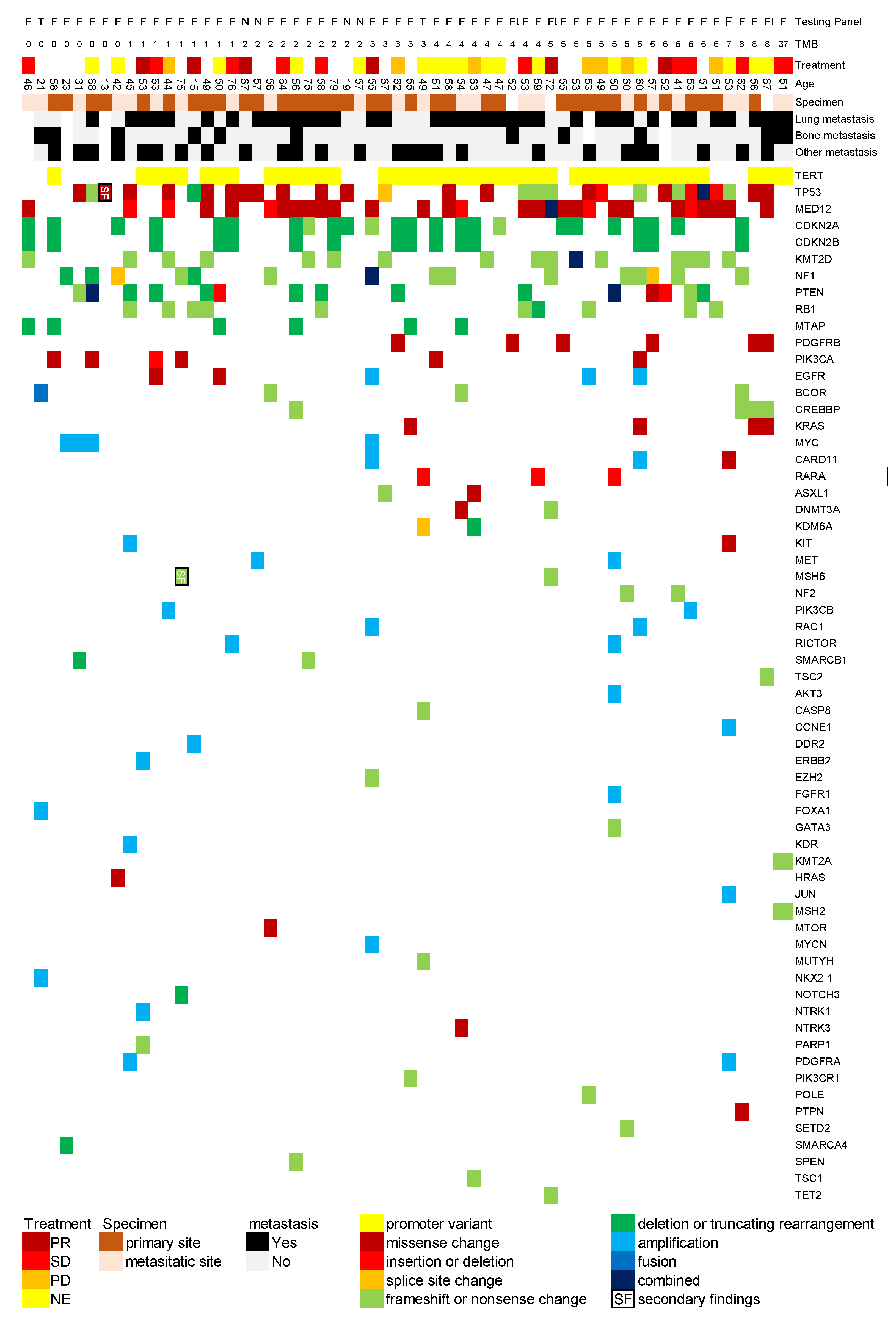

3.2. Overview of Genetic Alterations and Treatment Response

We analyzed the relationship between gene alterations identified through cancer genome profiling tests and response to first-line treatment. We created a comprehensive map illustrating the associations between gene alterations in phyllodes tumors, metastatic sites, treatment responses, tumor mutational burden (/Mb), and patient age based on database findings (

Figure 1).

TERT alterations were most frequently observed, with promoter variants detected in 42 cases (70%), though this frequency may be influenced by the test panel composition. This was followed by TP53 (30 cases, 50%), MED12 (29 cases, 52%), CDKN2A (24 cases, 40%), CDKN2B (15 cases, 25%), NF1 (15 cases, 25%), PTEN (15 cases, 25%), and RB1 (10 cases, 17%). It should be noted that TERT and MED12 are not included in the NCC Oncopanel System, necessitating careful interpretation of these results.

Several genes were detected in multiple cases (≤6 cases each), including MTAP, PIK3CA, EGFR, BCOR, CREBBP, KRAS, MYC, CARD11, RARA, ASXL1, DNMT3A, and KMD6A. However, in Japan, expert panels frequently discuss the possibility that ASXL1 and DNMT3A alterations may represent clonal hematopoiesis rather than somatic mutations caused by cancer.

Tumor mutational burden was reported as >0 /Mb in 52 cases, with a median of 4 /Mb and a maximum value of 37 /Mb. The case with 37 /Mb showed a positive response to Pembrolizumab treatment.

For reference, in the soft tissue sarcoma category of the C-CAT database (excluding Gastrointestinal stromal tumor cases), the most frequently registered pathogenic genes were, in descending order: TP53, MDM2, CDK4, and CDKN2A. While some genes, such as TP53, were commonly observed in both datasets, notable differences were identified, particularly the absence of TERT and MED12 alterations in the C-CAT database.

3.3. Analysis of Gene Alterations: Correlation with Treatment Response and Potential Germline Variants

Based on the results presented in

Table 1, we conducted an exploratory analysis. Using chi-square tests, we examined the relationship between gene alterations and treatment resistance in 23 patients who received first-line chemotherapy with documented treatment responses. Treatment resistance was defined as cases showing no response (stable disease or progressive disease), while treatment response was defined as cases achieving partial response.

Analysis of the association between specific gene alterations and treatment outcomes (Table. 3) revealed that although not reaching statistical significance, cases with CDKN2A and TERT alterations showed a trend toward treatment resistance with odds ratios exceeding 3.0. Notably, none of the cases with CDKN2B alterations demonstrated treatment response (p=0.09).

Regarding hereditary tumor predisposition, our expert panel review, conducted within Japan's insurance reimbursement framework, utilized multiple reference sources including the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare research findings (Kosugi Group Report) and the European Society for Medical Oncology guidelines [

15]. Through this standardized expert panel review process, we identified secondary findings suggestive of hereditary cancer syndromes in two cases (3.3%), involving

MSH6 and

TP53 alterations respectively.

4. Discussion

The implementation of genomic profiling in clinical practice has provided valuable insights into the molecular landscape of rare tumors, including phyllodes tumors of the breast. Our analysis of 60 cases from the C-CAT database represents one of the largest cohorts of phyllodes tumors with comprehensive genomic profiling to date. The findings reveal several important aspects regarding the molecular characteristics and potential therapeutic implications for this rare neoplasm.

The most frequently observed genetic alterations in our cohort were

TERT promoter variants (70%), followed by

MED12 (52%) and

TP53 (50%) mutations. This genetic profile aligns with previous studies that have highlighted the significance of these alterations in phyllodes tumors [

16,

17]. Notably, our clinical experience has demonstrated the utility of genomic testing in distinguishing between metaplastic carcinoma and phyllodes tumors in challenging cases (unpublished data). Similar diagnostic challenges have been previously reported in the literature, with genomic profiling proving instrumental in reaching definitive diagnoses [

18]. Emerging evidence suggests that DNA methylation patterns can serve as valuable diagnostic markers in differentiating these lesions [

19], adding another molecular tool to the diagnostic arsenal. Furthermore, while the differentiation between phyllodes tumors and fibroadenomas often presents clinical challenges,

TERT promoter mutations have been established as particularly useful diagnostic markers [

20,

21,

22]. The high frequency of

TERT promoter mutations observed in our cohort further supports their significance as a crucial molecular alteration in clinical practice.

The analysis of treatment response patterns revealed interesting correlations with specific genetic alterations. Although not reaching statistical significance, cases harboring CDKN2A and TERT alterations showed a trend toward treatment resistance (Odds Ratio >3.0). Particularly noteworthy was the complete lack of treatment response in cases with CDKN2B alterations (p=0.09). These findings suggest potential molecular markers that might predict treatment outcomes, though further validation in larger cohorts is necessary.

In our previous analysis of soft tissue sarcoma cases registered in the C-CAT database, we observed distinct patterns in terms of both molecular alterations and treatment responses. While soft tissue sarcomas showed a relatively low frequency of MDM2 and CDK4 amplifications, they demonstrated a trend where wild-type TP53 status correlated with better treatment outcomes (I. Takeda, S. Suzuki, et al. unpublished data). Interestingly, phyllodes tumors, despite being classified as fibroblastic neoplasms, did not show this same correlation. This disparity suggests potential differences in molecular pathogenesis and treatment response mechanisms between phyllodes tumors and other soft tissue sarcomas, despite their classification within the broader category of fibroblastic tumors.

The identification of microsatellite stability status in our cohort, with 55 out of 56 tested cases being microsatellite stable, provides important information regarding potential immunotherapy applications. However, the observation of one case with high tumor mutational burden responding to pembrolizumab suggests that genomic profiling might identify subset of patients who could benefit from immunotherapy approaches [

23].

The detection of potential germline variants in 3.3% of cases (involving

MSH6 and

TP53) highlights the importance of considering hereditary cancer syndromes in patients with phyllodes tumors. This finding aligns with previous reports of phyllodes tumors occurring in the context of Li-Fraumeni syndrome and other hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes [

24].

Our study has several limitations. The retrospective nature and the potential selection bias inherent in a registry-based study should be considered when interpreting the results. Additionally, the variation in genomic testing platforms used, particularly regarding the detection of specific alterations such as TERT promoter variants and MED12 mutations, which were not included in all panels, may affect the reported frequencies of these alterations. The accuracy of data entry and classification in large-scale registry databases also warrants careful consideration, as these factors could potentially impact our findings.

These findings suggest several directions for future research, including the validation of potential predictive biomarkers for treatment response and the exploration of novel therapeutic approaches based on specific molecular alterations. The identification of potentially actionable alterations in select cases warrants further investigation into targeted therapy approaches.

5. Conclusions

This comprehensive genomic profiling study of phyllodes tumors provides insights into their molecular landscape and potential therapeutic implications, suggesting the value of genomic testing in advancing our understanding of this challenging disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and Y.S.; methodology, S.S.; software, S.S. and Y.S.; validation, S.S.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, S.S..; resources, S.S..; data curation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, S.S.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Yamagata University Center of Excellence (YU-COE).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the “Ethical Guidelines for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects” and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine. (approval number: 2023-105) and the C-CAT Database Utilization Review Board (approval number: CDU2023-032N).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written and oral informed consent were obtained from the participants at genome designated hospitals.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated during this study is not publicly accessible due to confidentiality agreements as part of the ethics approval process.

Acknowledgments

We extend our deepest gratitude to all the patients. In the process of preparing this English manuscript, we used artificial intelligence-based language editing tools to enhance clarity and readability (DeepL, Grammarly, Google Translation, ChatGPT and Claude).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Naito, T.; Noji, R.; Kugimoto, T.; Kuroshima, T.; Tomioka, H.; Fujiwara, S.; Suenaga, M.; Harada, H.; Kano, Y. The Efficacy of Immunotherapy and Clinical Utility of Comprehensive Genomic Profiling in Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma of Head and Neck. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylén, C.; Mechera, R.; Maréchal-Ross, I.; Tsang, V.; Chou, A.; Gill, A.J.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J.; Robinson, B.G.; Sywak, M.S.; Sidhu, S.B. , et al. Molecular Markers Guiding Thyroid Cancer Management. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, D.; Johnson, A.; Sklar, J.; Lindeman, N.I.; Moore, K.; Ganesan, S.; Lovly, C.M.; Perlmutter, J.; Gray, S.W.; Hwang, J. , et al. Somatic Genomic Testing in Patients With Metastatic or Advanced Cancer: ASCO Provisional Clinical Opinion. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40, 1231–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.C.; Oliveira, M.; Howell, S.J.; Dalenc, F.; Cortes, J.; Gomez Moreno, H.L.; Hu, X.; Jhaveri, K.; Krivorotko, P.; Loibl, S. , et al. Capivasertib in Hormone Receptor-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2023, 388, 2058–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, R.; Tang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Huang, H.; Wu, D.; Fang, H.; Bai, Y.; Sun, C. , et al. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Rare Tumors: Routes to Targeted Therapies. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, S.K.; Yates, M.E.; Yang, S.; Oesterreich, S.; Lee, A.V.; Wang, X.S. Fusion-associated carcinomas of the breast: Diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic significance. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2022, 61, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, C.L.; Thomas, A.; Ng, B.K. Cystosarcoma phyllodes--Asian variations. Aust N Z J Surg 1988, 58, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, L.; Deapen, D.; Ross, R.K. The descriptive epidemiology of malignant cystosarcoma phyllodes tumors of the breast. Cancer 1993, 71, 3020–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimiento, J.M.; Gadgil, P.V.; Santillan, A.A.; Lee, M.C.; Esposito, N.N.; Kiluk, J.V.; Khakpour, N.; Hartley, T.L.; Yeh, I.T.; Laronga, C. Phyllodes tumors: race-related differences. J Am Coll Surg 2011, 213, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krings, G.; Bean, G.R.; Chen, Y.Y. Fibroepithelial lesions; The WHO spectrum. Semin Diagn Pathol 2017, 34, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conduit, C.; Luen, S.; Xu, H.; Byrne, D.; Fox, S.; Desai, J.; Hamilton, A. Using Genomic Sequencing to Explain an Exceptional Response to Therapy in a Malignant Phyllodes Tumor. JCO Precis Oncol 2020, 4, 1263–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozad, S.; Sheehan, C.E.; Gay, L.M.; Elvin, J.A.; Vergilio, J.A.; Suh, J.; Ramkissoon, S.; Schrock, A.B.; Hirshfield, K.M.; Ali, N. , et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of malignant phyllodes tumors of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017, 162, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bando, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Mitani, S.; Sawada, K.; Mishima, S.; Komine, K.; Okugawa, Y.; Hosoda, W.; Ebi, H. Japanese Society of Medical Oncology clinical guidelines: Molecular testing for colorectal cancer treatment, 5th edition. Cancer Sci 2024, 115, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M. , et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandelker, D.; Donoghue, M.; Talukdar, S.; Bandlamudi, C.; Srinivasan, P.; Vivek, M.; Jezdic, S.; Hanson, H.; Snape, K.; Kulkarni, A. , et al. Germline-focussed analysis of tumour-only sequencing: recommendations from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann Oncol 2019, 30, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, M.K.; Ooi, A.S.; Thike, A.A.; Tan, P.; Zhang, Z.; Dykema, K.; Furge, K.; Teh, B.T.; Tan, P.H. Molecular classification of breast phyllodes tumors: validation of the histologic grading scheme and insights into malignant progression. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011, 129, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, J.Y.; Shao, Y.; Poon, I.K.; Ni, Y.B.; Kwan, J.S.; Chow, C.; Shea, K.H.; Tse, G.M. Analysis of recurrent molecular alterations in phyllodes tumour of breast: insights into prognosis and pathogenesis. Pathology 2022, 54, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeong, J.; Thike, A.A.; Young Ng, C.C.; Md Nasir, N.D.; Loh, K.; Teh, B.T.; Tan, P.H. A genetic mutation panel for differentiating malignant phyllodes tumour from metaplastic breast carcinoma. Pathology 2017, 49, 786–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.; Stirzaker, C.; Ramkomuth, S.; Harvey, K.; Chan, B.; Lee, C.S.; Karim, R.; Deng, N.; Avery-Kiejda, K.A.; Scott, R.J. , et al. Detailed DNA methylation characterisation of phyllodes tumours identifies a signature of malignancy and distinguishes phyllodes from metaplastic breast carcinoma. J Pathol 2024, 262, 480–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Ong, C.K.; Lim, W.K.; Ng, C.C.; Thike, A.A.; Ng, L.M.; Rajasegaran, V.; Myint, S.S.; Nagarajan, S.; Thangaraju, S. , et al. Genomic landscapes of breast fibroepithelial tumors. Nat Genet 2015, 47, 1341–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Joseph, N.M.; Ravindranathan, A.; Stohr, B.A.; Greenland, N.Y.; Vohra, P.; Hosfield, E.; Yeh, I.; Talevich, E.; Onodera, C. , et al. Genomic profiling of malignant phyllodes tumors reveals aberrations in FGFR1 and PI-3 kinase/RAS signaling pathways and provides insights into intratumoral heterogeneity. Mod Pathol 2016, 29, 1012–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, M.; Ogawa, R.; Yoshida, H.; Maeshima, A.; Kanai, Y.; Kinoshita, T.; Hiraoka, N.; Sekine, S. TERT promoter mutations are frequent and show association with MED12 mutations in phyllodes tumors of the breast. Br J Cancer 2015, 113, 1244–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marabelle, A.; Fakih, M.; Lopez, J.; Shah, M.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Nakagawa, K.; Chung, H.C.; Kindler, H.L.; Lopez-Martin, J.A.; Miller, W.H., Jr. , et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol 2020, 21, 1353–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyami, H.; Yoo, T.K.; Cheun, J.H.; Lee, H.B.; Jung, S.M.; Ryu, J.M.; Bae, S.J.; Jeong, J.; Yoon, C.I.; Ahn, J. , et al. Clinical Features of Breast Cancer in South Korean Patients with Germline TP53 Gene Mutations. J Breast Cancer 2021, 24, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).