1. Introduction

Growth factor and differentiation 5 (GDF5) is a protein that has received particular interest since mutations, in studies carried out both in mice and in humans, are related to defects in the appendicular skeleton or to abnormal joint development [

1]. The interest in this protein is corroborated by a large number of studies. In particular, during the last year, 36 papers have been published on this topic (PubMed, access on 23/07/2023), 14 of them dealing with humans.

This protein, which belongs to the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) superfamily, is encoded by the GDF5 gene. Members of this family regulate cell growth and differentiation of several tissues at both embryonic and adult stages.

GDF5 is one of the first genes expressed in the embryonic joint interzone, where it is involved in the development of skeletal elements [

2]. It contributes to accelerating the initial stages of chondrogenicity and thus controls the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes [

3,

4,

5]. It also participates in the formation of the synovial articulation, tendons, ligaments and cartilage, their maintenance, as well as in bone formation [

6].

Furthermore, GDF5 is a neurotrophic protein that has effects on dopaminergic neurons [

1] and regulates the growth of neuronal axons and dendrites, carrying out a role in inflammatory response and tissue damage [

7].

Accordingly, mutations of

GDF5 gene have been associated to several pathologies caused by skeletal defects or abnormal joint development observed in congenital diseases, including Hunter-Thompson and Grebe type chondrodysplasia [

8].

GDF5 gene mutations are also responsible for type C brachydactyly, characterized by underdevelopment or absence of phalanges and metacarpals [

9]. In addition, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have suggested that

GDF5 gene polymorphisms are associated with knee and hip arthrosis [

10,

11].

The gene, which includes four exons, has been mapped on chromosome 20 at position q11.22. Among the numerous polymorphisms present in the

GDF5 gene, eight Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified through GWAS analysis (

www.gwascentral.org). The most studied are rs143383 and rs143384, both located in the 5′ UTR region, at a distance of 227 bp (see

Table 1), which turned out to be risk factors for osteoarthritis in adults [

12]. In particular, analysis of the rs143383 SNP indicated that the T allele (corresponding to the A allele in NCBI and 1,000 genomes dataset) showed reduced transcriptional activity and is overrepresented in patients with osteoarthritis [

13]. Likewise, the C allele of rs143383 (corresponding to the G allele in NCBI and 1,000 genomes dataset) is a protective factor against susceptibility to knee osteoarthritis [

14] and stress fractures [

15].

In the same way, it has been hypothesized that the G allele of rs143383 could protect against a potential injury of the lower limbs [

16]. A recent study by Meng et al. [

17] on the whole genome suggests that rs143384 is associated with knee pain and the A allele represents the predisposing factor. More recently, rs143384 was identified as significantly associated with increased susceptibility to chronic postsurgical pain, again with the A allele carriers showing an increased risk (7). However, the contribution of the GDF5 gene has not been directly elucidated based on biological evidence.

In a different study [

18], allelic variants of

GDF5 gene, which included rs143383 and rs143384, were shown to be associated with congenital dislocation of the hip (CDH) in Caucasians. The most significant association was observed with the rs143384 SNP. Individuals homozygous for the T allele (corresponding to the A allele in NCBI and 1,000 genomes dataset) have a higher risk of developing CDH compared to carriers of the other two genotypes.

As far as the other six SNPs evidenced by GWAS analysis (reported in dbSNP as rs224330, rs224331, rs224332, rs224333, rs224334 and rs7267783), no strong evidence of association between specific alleles and clinical conditions has been reported in the literature and therefore they were not further investigated in this report.

There is an increasingly frequent use of the regulatory region of the GDF5 gene in association studies to check its putative association with osteoarticular diseases. Therefore, the present research is aimed to verify if the worldwide distribution among human populations of the gene polymorphisms, particularly for the most investigated SNP rs143384 (G-A), has been shaped by selective pressure or it is the result of random genetic drift events.

2. Materials and Methods

We sampled 94 individuals of both sexes (53 females and 41 males, 18-28 years old) from Sardinia (Italy). The criteria to be included in the sampling are that all selected participants must be apparently healthy, unrelated, born and resident in Sardinia for at least three generations.

The research was performed in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki for Human Research of 1974 (last modified in 2000), and each participant signed a written informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria (AOU) of Cagliari University (Italy).

A buccal swab was obtained from each participant and preserved in absolute ethanol. DNA was then extracted by salting-out method. DNA concentration and purity were determined by NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The following primers were designed with PRIMERS BLAST (accessed on 4 June 2022): Forward: 5′-AGGCAGCATTACGCCATTC-3′; Reverse: 5′-TGAATTCCAGGTCCAGCCAA-3′. DNA was amplified in a 25 μL mixture containing 200 ng of genomic DNA, 20 pmol of each primer, and 0.2 U/μL of NZYTaq II (NZytech, Lisbon, Portugal). PCR protocol consisted in an initial denaturing step at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles at 94 °C for 30 sec, 53 °C for 45 sec, and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 5′. Amplicons were sequenced with Sanger method by Macrogen—Italy Service (Milan, Italy). Allele and genotype frequencies, as well as Hardy Weinberg equilibrium, were calculated with Genepop (ver. 4.4.3). Population variability was analyzed using the 1,000 Genome dataset (

https://www.internationalgenome.org/); matrix genetic distance [

19] was performed with Phylip (ver. 3.698) using all 26 populations reported in 1,000 genomes plus the Sardinian population. Population relationships have been checked by Multidimensional Scaling (MDS), based on the matrix of genetic distances, obtained through Statistica software (ver. 7).

For revealing possible traces of selective pressure, Population Branch Statistic (PBS) was calculated. Analysis was carried out with specific R packages [

20]. Using VCFtools [

21], a filter was applied to eliminate all variants with a MAF (Minimum Allele Frequencies) ≤ 0.05, and then FST for paired populations was calculated. Finally, PBS was calculated [

22] and plotted using the ggplot2 package on R Studio.

3. Results

Genotype and allelic frequencies of SNP rs143384 in the Sardinian sample were calculated with Genepop Program (ver. 4.4.3). Genotype distribution showed that the most abundant class was represented by the heterozygotes A/G with a frequency of 57.45, while the homozygotes A/A reported a frequency of 28.72, and the homozygotes G/G showed a frequency of 13.83. As to the allelic frequencies, the ancestral allele G showed a frequency of 0.426 and the derived A allele a frequency of 0.574.

When tested for Hardy-Weinberg, Genepop gave a p value of 0.969, indicating that the Sardinian population meets the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

We then compared our data with the worldwide populations data reported in the 1,000 Genomes database: there is an evident heterogeneous distribution in allele frequency as well as in genotype frequency. In particular, allele A in Africa is present at the very low frequency of 3%, whereas in east Asia the same allele reaches a frequency of 71% (

Table 1). Our sampling is within the range of European variability, where MAF (G) varies between 35% (CEU, Utah residents with European ancestry) and 47% (Tuscan population). Compared to the only other Italian population (from Tuscany) present in the dataset, the Sardinian population shows just a modest decrease in frequency of the G allele (42.6% vs 47.2%).

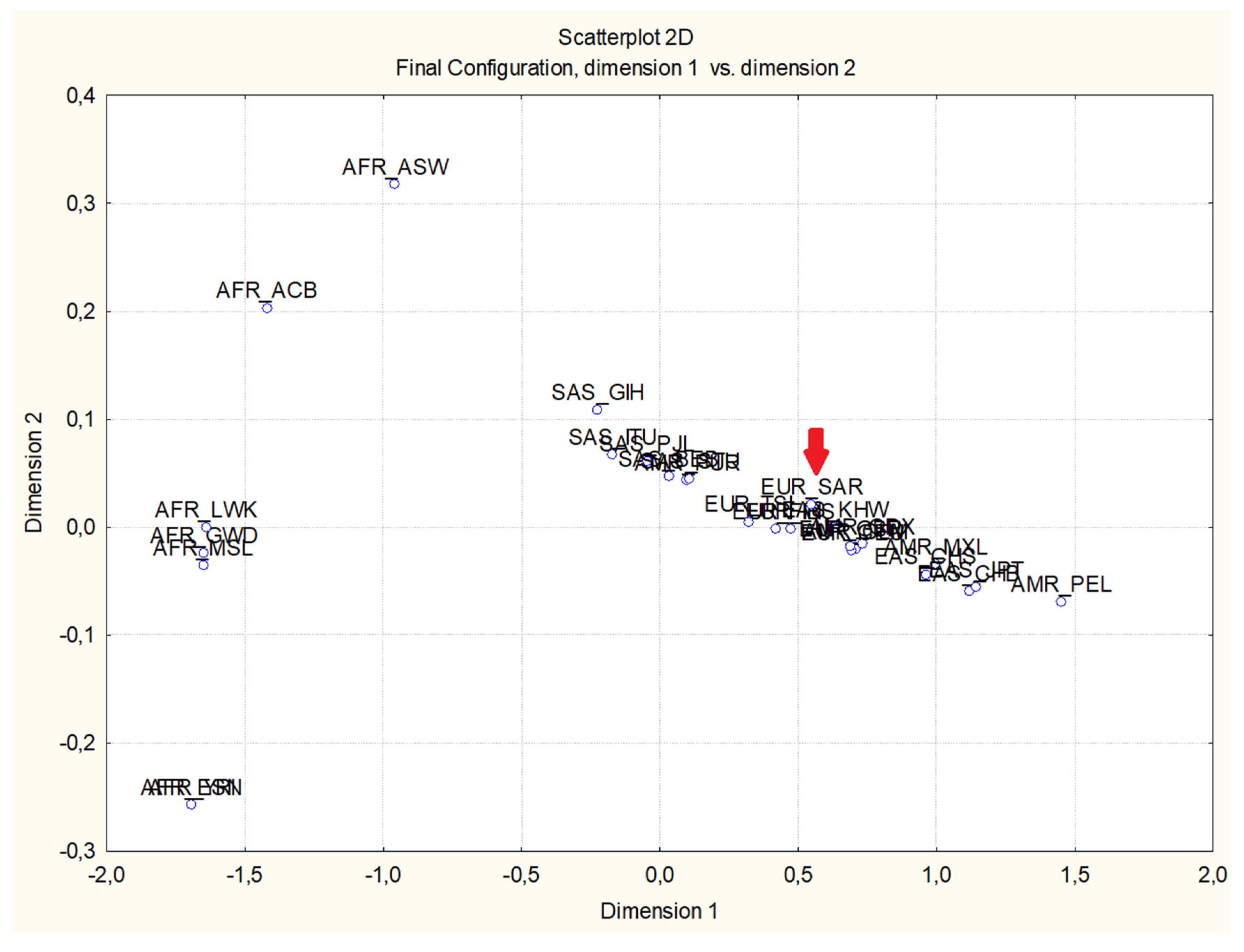

MDS analysis (

Figure 1) confirmed the strong differentiation of African populations from the others; indeed, all African populations clustered in a unique area in the 1st and 3rd quadrants, characterized by negative values of first component, while the remaining populations occupied a restricted area prevalently in the 2nd and the 4th quadrants. The Sardinian population is placed withing the European cluster. Moreover, African populations occupy a large area of the graphic, suggesting an evident heterogeneity, as expected from The Out of Africa hypothesis.

Given the remarkable variability in the worldwide frequencies’ distribution of the

SNP rs143384, we decided to check for the possible presence of a selective pressure on the gene. For this aim, we used the PBS test, which proved to be the best method for detecting traces of natural selection in the genome [

22].

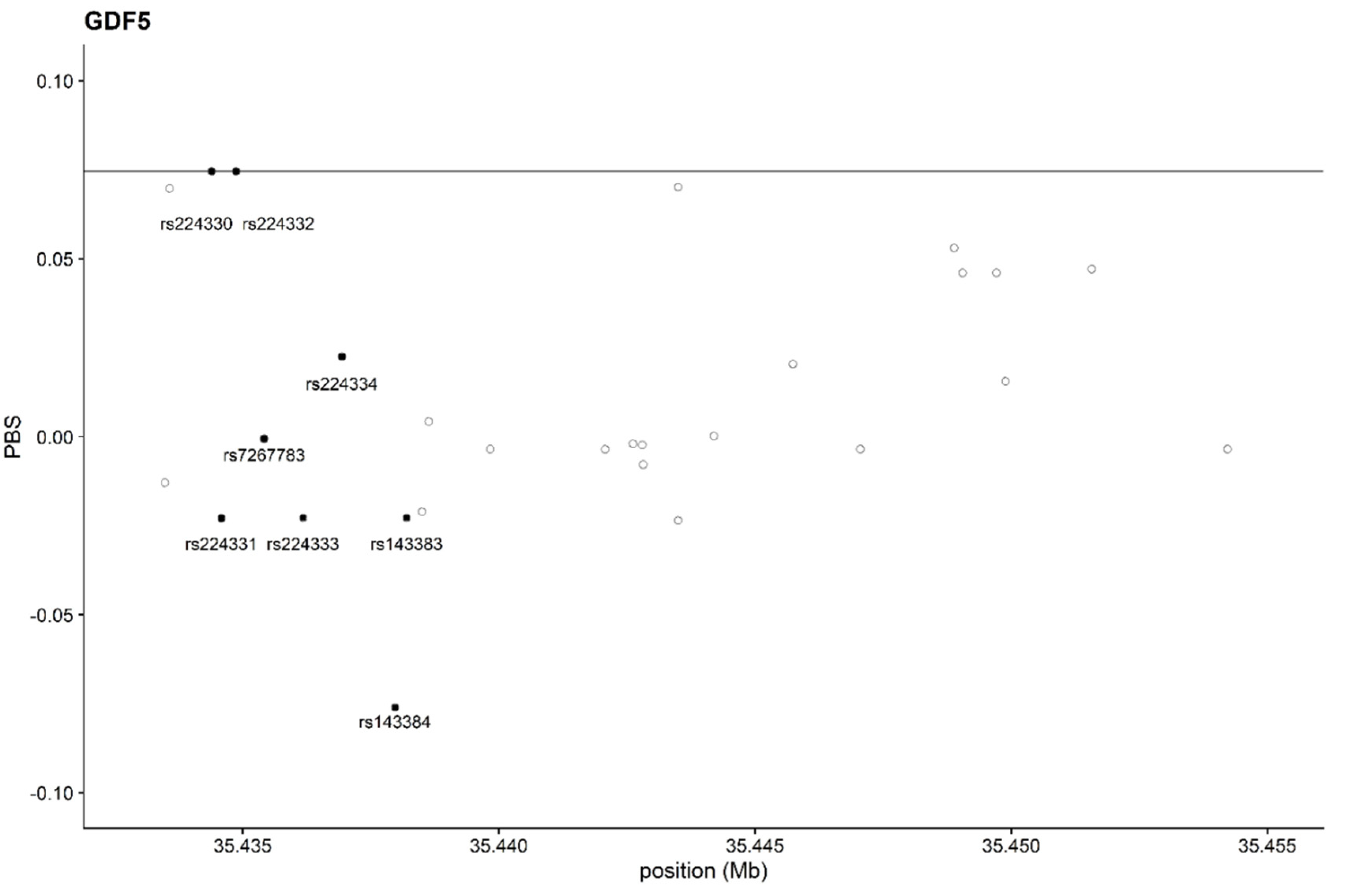

In the plot of PBS (

Figure 2) no outliers among the SNPs in

GDF5 gene have been identified: the two SNPS rs224330 and rs224332 are located at the top of the empirical distribution of PBS values for

GDF5, just on the line of 99.9th percentile, whilst the two SNPs reported as potentially correlated with osteoarticular diseased or muscular flexibility (rs143384 and 143383) have low values of PBS, suggesting no signal of selective pressure in those areas of the genes.

4. Discussion

In the present research, we have investigated the possible evolutionary forces that have shaped the frequencies of the polymorphism rs143384 G/A, which is considered a risk factor for osteoarthritis in adults according to several GWAS studies.

The worldwide distribution of rs143384 SNP mirrors the spread of modern humans out of Africa according to the Single Origin Model [

23] that originated in Africa about 200K years ago and then initially migrated to South Asia from 100K to 70K years ago, reaching more recently Europe and North-East Asia about 50-45K years ago, eventually colonizing the Americas 20-15K years ago. Indeed, African population appears almost monomorphic for the ancestral G allele, while the derived A allele appears to be rather frequent in the Southern Asian regions that were reached by the early expansion of Homo sapiens, with a progressive increase in the areas of more recent colonization such as Europe, East Asia and the Americas (

Table 1). This overall clinal distribution from the ancestral modern human homeland (

Figure 1), pointing out to an isolation by distance model, suggests the combined effect of gene flow, genetic drift and possible founder effects due to subsequent waves of migrations. The Sardinian sample falls within the European variability, not showing any sign of genetic peculiarity of the island population, unlike previously observed for other markers [

24]. It should be noted that rs143383

, the other SNP found associated to osteoarthritis by GWAS analysis, shows an analogous worldwide allelic distribution (

Table 1).

Several recent studies, based on GWAS analysis, have suggested that some allelic variants may be associated to several pathologies; therefore, we investigated if their distribution could be the result of a natural selection.

The search for selective forces within the human genome is becoming increasingly important in evolutionary studies, particularly in evolutionary medicine. It is well known that SNPs related to advantageous or disadvantageous phenotypes can be selected (either fixed or removed) by evolutionary forces. The loss of disadvantageous alleles (negative selection) generally reduces the degree of variance among populations, whilst the fixation of a new variant (positive selection) leads to an increment of population differentiation [

25].

The PBS analysis here reported does not show evidence of selective pressure on the whole

GDF5 gene and, in particular, the rs143384 polymorphism here considered fell in the lower percentile in respect to all the other variants (

Figure 2).

In conclusion, even though literature data showed an association with pathological conditions, the allelic variation for rs143384 is consistent with a worldwide distribution that has been shaped by random events following the modern human migration out of Africa. Therefore, the observed variation might be due to genetic drift (including founder effect and/or bottleneck), gene flow and other demographic changes that the populations may have gone through. Finally, the data reported in the present study are not in contrast with the data reported in the literature; indeed, it is entirely possible that SNP rs143384 may be truly associated with osteoarticular diseases. However, there is no evidence of natural selection, probably because such pathologies are not early onset. Therefore, such variant is expected to have a negligible, if any, effect on the individual fitness, with no apparent consequence on reproductive ability. In this scenario, the distribution of rs143384 polymorphism is the result of random evolutionary forces.

Author Contributions

L.F.: Data curation, Formal analysis and Investigation; P.F.: Validation and Writing—review & editing; M.M.: Data curation and Resources; R.R.: Validation and Writing—original draft: C.M.C.: Conceptualization, Supervision and Writing—review & editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria (AOU) of Cagliari University (Italy).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all participants who made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sullivan, A.M.; O’Keeffe, G.W. The role of growth/differentiation factor 5 (GDF5) in the induction and survival of midbrain dopaminergic neurons: relevance to Parkinson’s disease treatment. J. Anat. 2005, 207, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storm, E.E.; Huynh, T.V.; Copeland, N.G.; Jenkins, N.A.; Kingsley, D.M.; Lee, S.J. Limb alterations in brachypodism mice due to mutations in a new member of the TGF beta-superfamily. Nature 1994, 368, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis-West, P.H.; Abdelfattah, A.; Chen, P.; Allen, C.; Parish, J.; Ladher, R.; Allen, S.; MacPherson, S.; Luyten, F.P.; Archer, C.W. Mechanisms of GDF-5 action during skeletal development. Development 1999, 126, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Shirai, T.; Morishita, S.; Uchida, S.; Saeki-Miura, K.; Makishima, F. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase functionally contributes to chondrogenesis induced by growth/differentiation factor-5 in ATDC5 cells. Exp. Cell Res. 1999, 250, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, P.; Edwards, C.; Archer, C.W.; Francis-West, P. Growth/differentiation factor-5 (GDF-5) and skeletal development. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2001, 83-A Suppl 1(Pt 1), S23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, C.W.; Dowthwaite, G.P.; Francis-West, P. Development of synovial joints. Birth Defects Res. C. Embryo Today 2003, 69, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Nie, H.; Bu, G.; Yuan, W.; Wang, S. The effect of common variants in GDF5 gene on the susceptibility to chronic postsurgical pain. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.T.; Kilpatrick, M.W.; Lin, K.; Erlacher, L.; Lembessis, P.; Costa, T.; Tsipouras, P.; Luyten, F.P. Disruption of human limb morphogenesis by a dominant negative mutation in CDMP1. Nat. Genet. 1997, 17, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinkovsky, A.; Robin, N.H.; Thomas, J.T.; Irons, M.; Lynn, A.; Goodman, F.R.; Reardon, W.; Kant, S.G.; Brunner, H.G.; van der Burgt, I.; Chitayat, D.; McGaughran, J.; Donnai, D.; Luyten, F.P.; Warman, M.L. Mutations in CDMP1 cause autosomal dominant brachydactyly type C. Nat. Genet. 1997, 17, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, M.S.; Yerges-Armstrong, L.M.; Liu, Y.; Lewis, C.E.; Duggan, D.J.; Renner, J.B.; Torner, J.; Felson, D.T.; McCulloch, C.E.; Kwoh, C.K.; Nevitt, M.C.; Hochberg, M.C.; Mitchell, B.D.; Jordan, J.M.; Jackson, R.D. Genome-Wide Association Study of Radiographic Knee Osteoarthritis in North American Caucasians. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naureen, Z.; Lorusso, L.; Manganotti, P.; Caruso, P.; Mazzon, G.; Cecchin, S.; Marceddu, G.; Bertelli, M. Genetics of pain: From rare Mendelian disorders to genetic predisposition to pain. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91(13-S), e2020010. [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin, J. Genetic contribution to osteoarthritis development: current state of evidence. Curr Opin. Rheumatol. 2015, 27, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Mabuchi, A.; Shi, D.; Kubo, T.; Takatori, Y.; Saito, S.; Fujioka, M.; Sudo, A.; Uchida, A.; Yamamoto, S.; Ozaki, K.; Takigawa, M.; Tanaka, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Ikegawa, S. A functional polymorphism in the 5’ UTR of GDF5 is associated with susceptibility to osteoarthritis. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Jin, S.; Lu, J.; Ouyang, C.; Guo, J.; Xie, Z.; Shen, H.; Wang, P. Association between growth differentiation factor 5 rs143383 genetic polymorphism and the risk of knee osteoarthritis among Caucasian but not Asian: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2020, 22, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Chang, Q.; Huang, T.; Huang, C. Prospective cohort study of the risk factors for stress fractures in Chinese male infantry recruits. J. Int. Med. Res. 2016, 44, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stastny, P.; Lehnert, M.; De Ste Croix, M.; Petr, M.; Svoboda, Z.; Maixnerova, E.; Varekova, R.; Botek, M.; Petrek, M.; Kocourkova, L.; Cięszczyk, P. Effect of COL5A1, GDF5, and PPARA Genes on a Movement Screen and Neuromuscular Performance in Adolescent Team Sport Athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2057–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Adams, M.J.; Palmer, C.N.A. 23andMe Research Team; Shi, J.; Auton, A.; Ryan, K.A.; Jordan, J.M.; Mitchell, B.D.; Jackson, R.D.; Yau, M.S.; McIntosh, A.M.; Smith, B.H. Genome-wide association study of knee pain identifies associations with GDF5 and COL27A1 in UK Biobank. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouault, K.; Scotet, V.; Autret, S.; Gaucher, F.; Dubrana, F.; Tanguy, D.; El Rassi, C.Y.; Fenoll, B.; Férec, C. Evidence of association between GDF5 polymorphisms and congenital dislocation of the hip in a Caucasian population. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010, 18, 1144–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.; Weir, B.S.; Cockerham, C.C. Estimation of the coancestry coefficient: Basis for a short-term genetic distance”. Genetics 1983, 105, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. 2021. Available online: https://www.R-project.org.

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. 1000 Genomes Project Analysis Group. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Liang, Y.; Huerta-Sanchez, E.; Jin, X.; Cuo, Z.X.; Pool, J.E.; Xu, X.; Jiang, H.; Vinckenbosch, N.; Korneliussen, T.S.; et al. Sequencing of 50 Human Exomes Reveals Adaptation to High Altitude. Science 2010, 329, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, R.L.; Stoneking, M.; Wilson, A.C. Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution. Nature 1987, 325, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calò, C.M.; Vona, G.; Robledo, R.; Francalacci, P. From old markers to next generation: reconstructing the history of the peopling of Sardinia. Ann Hum Biol. 2021, 48, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiro, L.B.; Laval, G.; Quach, H.; Patin, E.; Quintana-Murci, L. Natural selection has driven population differentiation in modern humans. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).