1. Introduction

Wound healing is a highly orchestrated process comprising four perpetual and concurrent phases [

1]. Firstly, homeostasis is established, followed by an immediate inflammatory response with a marked accumulation of cytokine-producing leukocytes and antimicrobial function. Subsequently, the damaged area is cleaned, followed by wound compression as the remodeling of the extracellular matrix [

1]. Mostly the process of wound healing progressed normally; however, under certain physiological conditions, such as chronic disease, malnutrition, diabetes, and aging, this process is impaired, leading to chronic wounds and has a significant onus to patients and the medical system [

1,

2]. Severity can be assumed from the fact that approximately 4.5 million people in the USA are affected by chronic wounds [

3]. Despite the disparity in etiology, chronic wounds shared certain common traits at the molecular level, comprising protraction and augmented inflammation characterized by abundant neutrophil infiltration, enhanced level of cytokines, proteases, reactive oxygen species (ROS), senescent cells, and enduring infection [

3]. Chronic and non-healing wounds, such as foot ulcers, are the secondary complications associated with diabetes that inflict constant medication; even in many cases, amputation is required [

4]. Diabetes is well characterized by the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) such as carboxymethyl lysine (CML) that integrate with skin collagen and alter epithelial cell migration and differentiation, consequently delaying wound healing [

4]. In this context, different cutting-edge treatments comprise the application of extracellular matrices, engineered skin, negative pressure, and growth factors have been broadly applied to treat chronic wounds [

3].

Notably, ozone, owing to its antioxidant, antimicrobial, and immunomodulatory effect, has been projected as a potential agent for wound healing [

5]. For instance, a marked impact of ozone therapy to accelerate wound healing and reduce amputation has been described in diabetic foot ulcers [

6]. Interestingly, ozone therapy has been documented to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, which are the established hallmarks of chronic wounds and, thus, provides a curative potential against chronic wounds [

7]. In support, numerous in vitro investigations have probed the influence of ozone on fibroblast migration and the manifestation of collagen-1, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), an important biomarker for tissue repair, which strengths ozone applicability to deal with chronic wounds [

8]. Moreover, ozone therapy is also documented for its potential to improve lipid profile, precisely by enhancing HDL-C and reducing LDL-C and TG [

9]. Also, few studies have demonstrated the correlation of HDL with chronic wound healing via switching M1 to M2 macrophages and consequent downregulation of inflammatory markers such as

iNOS, IL-6, and TNF-α [

10,

11]. Despite the several medicinal benefits, the short half-life of ozone is always a point of contention. Fortunately, this can be augmented substantially via the chemical entrapment of gaseous ozone in unsaturated substances containing plant oils. For example, the successful entanglement of ozone in olive and sunflower oil is available commercially, displaying several medicinal worth’s, primarily linked to antimicrobial and antioxidant nature [

12].

Of note, the substantial wound-healing activity of gaseous ozone [

13], ozonated water [

14], and ozone entrapped in olive oil [

15], and sesame oil [

16] have been described; however, the wound healing and tissue regenerative activity of ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) has not been studied extensively. Hitherto, most of the studies pertaining to OSO have primarily concentrated on its antimicrobial and germicidal properties [

12,

17]. We have previously documented OSO’s antimicrobial, cellular antioxidant [

18], and anti-inflammatory potential [

19] in zebrafish fed with a high cholesterol diet (HCD).

In continuation to our previous studies, the present study aimed to evaluate the healing potential of OSO on cutaneous wound stimulated by CML-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in adult zebrafish. Additionally, the role of OSO is tested for improvement of tail fin regeneration after amputation, survivability, hepatic function protection, and blood lipid profile amelioration in the CML-injected zebrafish.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) (Raydel

® Bodyone, Flambo oil) was complementary provided by Rainbow and Nature Pty, Ltd. (Thornleigh, NSW, Australia), which harbors the characteristic Oleozon

®, as described previously [

20]. The sunflower oil (SO) was procured from a retail store located in Daegu, Republic of Korea. N-ε-carboxylmethyllysine (CAS-No 941689-36-7, Cat#14580-5g), 2-phenoxyethanol (SigmaP1126; St. Louis, MO, USA), oil red O (Cat#O0625), and dihydroethidium (DHE, 104821-25-2, Cat #37291), were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Unless otherwise stated, all other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade and used as supplied.

2.2. Zebrafish Husbandry

Zebrafish were nurtured per the accredited framework of care and use of laboratory animals [

21,

22] following the procedure approved by the Animal Care Committee and the Use of Raydel Research Institute (approval code RRI-20-003). Zebrafish were maintained at 28°C (water temperature) at 14 h light and 10 h dark photoperiod in an automated water circulation tank (Bioengineering Company; Daejeon, Korea). with the consumption of normal tetrabits flake (TetrabitGmbh D49304, 47.5% crude protein, 6.5% crude fat, 2.0% crude fiber, 10.5% crude ash, containing vitamin A (29770 IU/kg), vitamin D3 (1860 IU/kg), vitamin E (200 mg/kg), and vitamin C (137 mg/kg), Melle, Germany).

2.3. Cutaneous Wound Formation in Adult Zebrafish and OSO Treatments

The wound healing effect of SO and OSO was assessed in 16-week-aged adult zebrafish. For wound generation, zebrafish were anaesthetized by drenching in 0.1% of 2 phenoxyethanol, followed by removal of the surface scale. A cutaneous wound of 2 mm diameter was notched into the left flank directly anterior to the anal and dorsal fin using a sterilized biopsy punch (Kai Industries co., Ltd., Oyana, Japan). The wounded zebrafish (n=60) were randomly distributed into four groups (n=15, each group). The cutaneous wound of zebrafish in Group I was topically treated with 1 μL of PBS (control), while the cutaneous wound of zebrafish in Group II was topically treated with 1 μL of 25 mg/mL CML in PBS (final 25 μg). In Groups III and IV, the cutaneous wound of zebrafish was treated with 1 μL SO (final 2%) and 1 μL OSO (final 2%) together with CML (25 μg final), respectively. After 3 min post-treatment, zebrafish from distinct groups (I-IV) were transferred into their respective chambers and maintained at 28°C.

2.4. Visual Observation and Wound Healing

Zebrafish were constantly monitored, and the wound area was measured at 0, 2, 4, 6, 24, 48, 72, 120, 168, and 264 h post-treatment using methylene blue staining as earlier described method [

23]. In brief, at different time points, zebrafish were anaesthetized, and the wound was stained with methylene blue solution (0.1%

w/v, final 2 μL) for 1 min, followed by three-time washing and subsequent visualization under a stereomicroscope (Motic SMZ 168; Hong Kong). The wound area (blue stained) was computed employing Image J software (version 1.53r,

http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/ accessed and retrieved on May 16, 2022). Percentage wound healing was quantified by comparing the wound area (mm

2) calculated at 2, 4, 6, 24, 48, 72, 120, 168, and 264 h post-treatment with the wound area at the beginning (0 h).

2.5. Histological Analysis During Wound Healing

Histology analysis concerning morphological changes and oxidative stress in the wounded site was examined during wound healing. At 72- and 168-hr post-treatment, 3 zebrafish from each group were retrieved, and tissue from the wounded site was surgically removed and fixed in 10% formaldehyde, followed by alcohol dehydration and amalgamation in paraffin. A 5 μm thick tissue section was prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) [

24] to visualize the morphological changes.

The oxidative stress status of the tissue was determined by the visualization of total reactive species (ROS) stained with dihydroethidium (DHE) as a previously described method [

25]. The stained images were observed under fluorescent microscopy (Nikon Eclipse TE2000, Tyko, Japan)at 588 nm and 605 nm excitation and emission wavelength, respectively.

2.6. Regeneration of Tail Fin

The comparative tissue regenerative effect of SO and OSO was evaluated in 16-week-aged adult zebrafish as previously described method [

26]. In brief, zebrafish (n=60) were anaesthetized by inundating in 0.1% of 2 phenoxyethanol, and the tail fin was amputated by a scalpel adjacent to dermal rays in the tail fin. Tail-fin amputated zebrafish were randomly segregated into 4 groups (n=15, each group). The zebrafish in Group I and II received intraperitoneal injection of 10 μL PBS and 250 μg CML suspended in 10 μL PBS (analogue to 3 mM CML, contemplating ~zebrafish body weight 300 mg), respectively. Zebrafish in Group II and IV received 10 μL intraperitonial injection of CML (250 μg)+SO (final 2%) and CML (250 μg)+OSO (final 2%), respectively. The tail fin regeneration was examined under the stereomicroscope (Motic SMZ 168; Hong Kong) equipped with Motic cam2300 CCD camera (Motic cam2300 CCD). Images of the tail section were captured on successive days until day 7, and the tail fin regeared area was computed employing Image J software (version 1.53r,

http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/ retrieved on June 16, 2022).

2.7. Acute Inflammation in Zebrafish

Acute inflammation in adult zebrafish was instigated by injecting CML (250 μg/10 μL of PBS), as reported earlier [

27]. Sixteen weeks aged adult zebrafish were randomly divided into 5 groups. Zebrafish in Groups I and II received intraperitoneal injections of 10 μL PBS and 10 μL CML (250 μg in PBS), respectively. Group II and III zebrafish received intraperitoneal injections of 250 μg CML suspended in 10 μL SO (final 1%) and SO (final 2%). Correspondingly, Group III and IV zebrafish were microinjected with 250 μg CML suspended individually in 10 μL of OSO (final 1% and 2%), respectively. All the groups received microinjections at the abdominal region using a 28-gauge needle after anesthetization by plunging in 0.1% 2-phenoxyethanol. The zebrafish survivability and swimming behavior were assessed at 30- and 60-min post-injection following the guidelines of OECD 2019 [

28].

Zebrafish in various groups were sacrificed after 60-min post-injection using the hypothermic shock as described previously [

19]; blood was collected immediately by the heart puncture from each zebrafish, and combined with 3 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, final concentration, 1 mM), then collected in EDTA-treated tubes. The liver tissues were collected and preserved at ultra-low temperature (-70

oC) for histological investigations.

2.8. Plasma Analysis for Lipid Profile and Hepatic Function Biomarkers

The total cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) levels in the plasma were determined using a commercial assay kit (cholesterol, T-CHO, and TGs, Cleantech TS-S; Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan). HDL-C (AM-202), aspartate transaminase (AST), and alanine transaminase (ALT) were measured using a commercially available assay kit using AM-202, AM-103K, and AM102-K (Asan Pharmaceutical, Hwasung, Korea), correspondingly.

2.9. Histological and Immunohistochemical Investigation

The hepatic tissue from zebrafish was excised surgically and processed, as mentioned in section 2.6. The hepatic morphological changes and ROS production were examined by H&E and DHE staining, respectively, as mentioned in section 2.6.

The pro-inflammatory IL-6 level in the hepatic tissue was determined by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining as previously described method [

29]. In brief, the tissue section was flooded with 200× diluted IHC primary antibody (ab9324, Abcam, London, UK), followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. The EnVision+ System-HRP polymer kit containing secondary antibody (1:1,000, Code K4001, Dako, Denmark) developed the IHC stained area that was visualized under an ocular microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

2.10. Statistical Analysis

All the experiments were accomplished in triplicates, and results are depicted as mean ± standard deviation. The statistical difference between the groups was determined using SPSS software (version 23.0; Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software program, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), employing one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following post hoc examination (p<0.05) using Tukey’s multiple range test. The multivariate exploratory techniques of principal component analyses (PCA) and hierarchical clustering (HCA) were performed using Minitab statistical software version 21.4.

4. Discussion

Wounds, especially chronic wounds, are a global problem that puts significant health and economic burden [

30]. There are different advancements in dealing with chronic wounds. However, most of them have certain limitations owing to the complexity of chronic wounds, where multiple events participate that varies from wound to wound. However, extravagant oxidative stress and enduring inflammation are the worthiest attributes among all the chronic wounds that provoke assorted molecular events, leading to delayed wound healing [

31]. Therefore, a curative agent must harbor pleiotropic pursuit with momentous antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity. Sunflower oil (SO) is a rich source of diverse phytoconstituents and minerals with notable functionality, including derma protective and antimicrobial activity [

32]. Fortunately, the proficiency of SO can be ameliorated prodigiously by ozonation.

Accumulative literature has cataloged OSO’s diverse functionality, including antioxidant and antimicrobial activity [

33,

34]. Recently we have accentuated the antioxidant role of OSO that thwart macrophages from apoptotic cell death [

18] and elevates zebrafish survivability, dyslipidemia, and hepatic steatosis altered by high cholesterol diet [

19]. Despite the several perks, OSO has not been probed meticulously for wound healing and tissue regeneration employing zebrafish, that considered the exemplary model for preclinical investigations [

35,

36]. Nonetheless, few preliminary observations on turtles substantiated the wound-healing role of OSO [

37]. Pertaining to this, we delved into the comparative wound healing, tissue regenerative, and hepatoprotective efficiency of SO and OSO against CML-posed adversity in zebrafish. CML is well known oxidative stressor [

31] associated with diabetic and cardiovascular diseases and often ties with a collagen matrix, leading to compromised wound healing [

4]. Herein, the CML was used to instigate oxidative stress and inflammation (to emulate the chronic wound environment), and the therapeutic implication of SO and OSO was investigated.

The collected results suggested that zebrafish treated with OSO emerge with rapid cutaneous wound healing impaired by the exposure of CML. Nevertheless, compared to SO, a profound wound-healing effect by OSO, implying the modulatory impact of ozonation on the activity of SO. The apparent reason for the difference in the healing activity is the presence of ozonized and other ozone-catalyzed compounds in OSO that are well-known for varied biological activity [

12,

38]. The results align with the previous reports implying the impact of ozonation on the ameliorated functionality of SO [

18,

19]. The better wound healing activity of OSO is strengthened by the earlier report deciphering the impact of ozone therapy on diabetic foot ulcers by the cellular induction of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelets-derived growth factors (PDGF) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [

8]. Following similar effects, we believe entrapped ozone in OSO leads to prompt wound recovery against the adversity posed by the CML.

The H&E and DHE staining of the wounded tissue documented massive neutrophil infiltration and ROS production in response to CML that SO and OSO proficiently neutralized. Moreover, a time-dependent augmentation of ROS in response to CML was observed that designates high oxidative stress, a hallmark of chronic wounds. Treatment of SO and OSO, precisely OSO, efficiently thwarts the CML-induced ROS inclining toward wound healing with time. The results of DHE staining clearly imply that CML-induced oxidative stress is the main culprit behind delayed wound healing, and the antioxidant property of OSO is a key event that leads to expedited wound recovery. The findings collectively indicated that OSO, owing to its vigorous antioxidant character, counters the CML-impelled oxidative stress and provides a lucrative environment for wound healing. Results comply with our preceding reports documenting OSO’s free radical scavenging potential and cellular antioxidant activity [

18,

19]. Additionally, several studies have cataloged the impact of ozone on the induction of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) that coordinates the synthesis of cellular antioxidants to counter oxidative stress [

39,

40].

Furthermore, it has been well established that around 60% of chronic wounds face bacterial colonization at the wounded site [

41]. Therefore, a substance with a broad range of antimicrobial action in addition to antioxidant and tissue regenerative activity is more coveted. Fortunately, OSO has an intense antibacterial activity [

18], invigorating OSO prospects as therapeutic to cure chronic wounds.

Besides the cutaneous wound healing, a comparative role of SO and OSO on tail fin regeneration and CML-induced acute paralysis was determined. Like the cutaneous wound healing, OSO2% prompted the amputated tail fin regeneration impaired by the CML injection. Contrary to this, no effect of SO2% on tail fin regeneration was observed, manifesting the influence of ozonation on the functionality of SO. The rigorous mechanism behind the tissue-productive potential of ozonated oil has yet to be fully understood. Presumably, the OSO’s antioxidant [

18] and anti-inflammatory [

19] properties lead to curative events for tissue generation. The notion is in accordance with an earlier report documenting the inflammation regulatory effect of ozonated water expedites the caudal fin regeneration of zebrafish [

42].

Furthermore, OSO2% displayed a remarkable resilience against CML-induced acute paralysis, evidenced by rapid restoration of swimming activity. The precise mechanism behind the improved swimming activity and survivability has yet to be discovered. Nevertheless, OSO’s anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties are crucial to rescuing zebrafish from CML-induced toxicity. The cognition is strongly backed by our earlier finding describing the inhibition of proinflammatory IL-6 by CIGB-258, and tocilizumab leads to the recovery of zebrafish from acute paralysis [

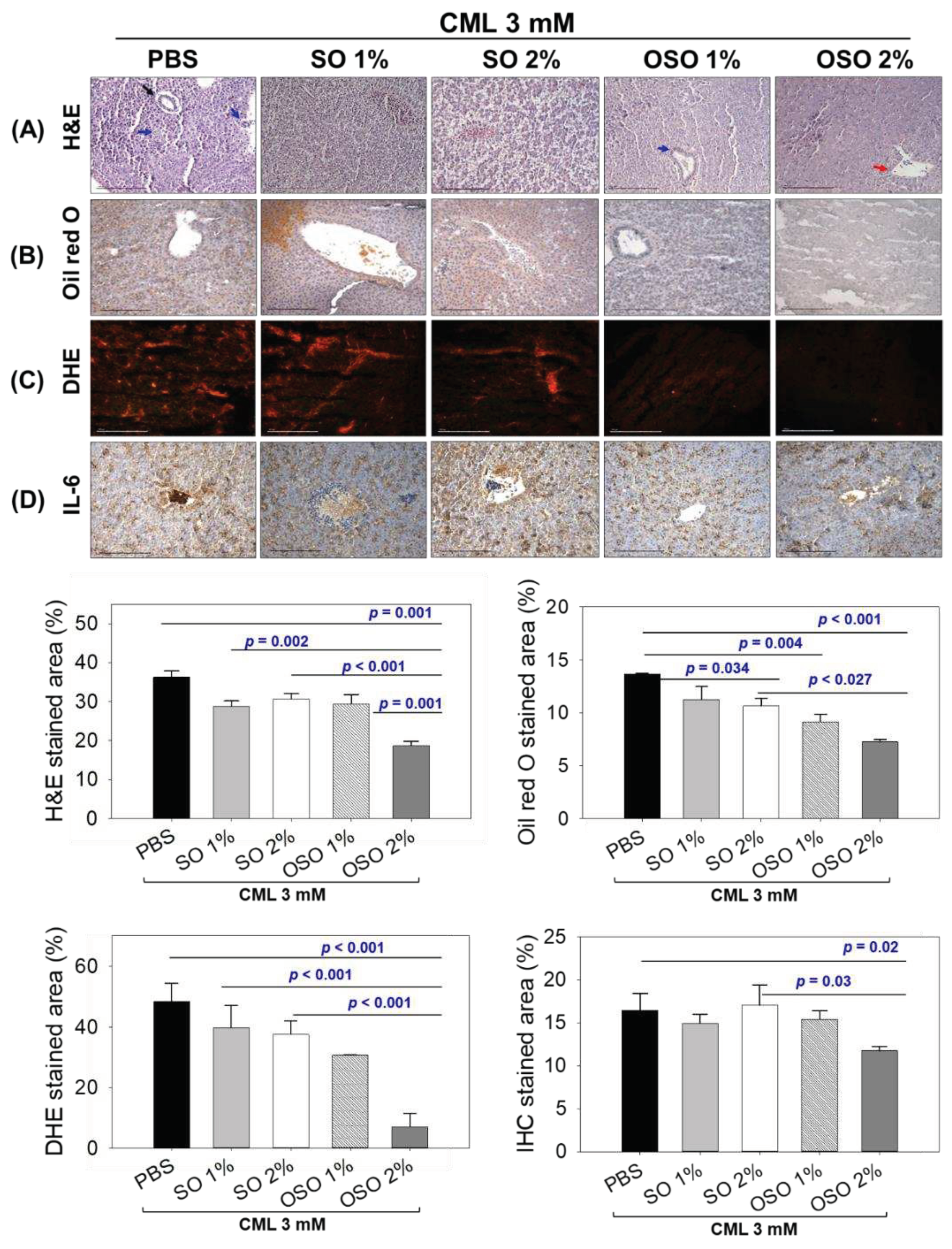

43]. Additionally, OSO2% displayed hepatoprotection against CML-induced toxicity, apparent by reduced neutrophil infiltration, as observed in H&E staining. Also, the oil red O staining demonstrates the preclusion of fatty liver changes by OSO2%. Likewise, OSO2% efficiently curtailed CML-induced IL-6 and ROS generation, indicating OSO’s anti-inflammatory and antioxidant role (

Figure 9).

Proinflammatory IL-6 is a pivotal cytokine allied with inflammatory diseases [

44] and acute paralysis [

43]. The low hepatic IL-6 level in response to OSO2% justifies that IL-6 inhibition by OSO is the primary reason for rescuing zebrafish against CML-induced acute paralysis and mortality. Evermore, several studies acknowledged a positive correlation between IL-6, liver fibrosis [

45], and fatty liver changes [

46]. Herein, we have also observed a similar trend that inhibiting IL-6 by OSO improves CML-impaired fatty liver changes. The antioxidant nature of OSO may be a reason for the lower IL-6 production, supported by the literature describing oxidative stress as a provocative factor for the induction of inflammatory pathways [

47].

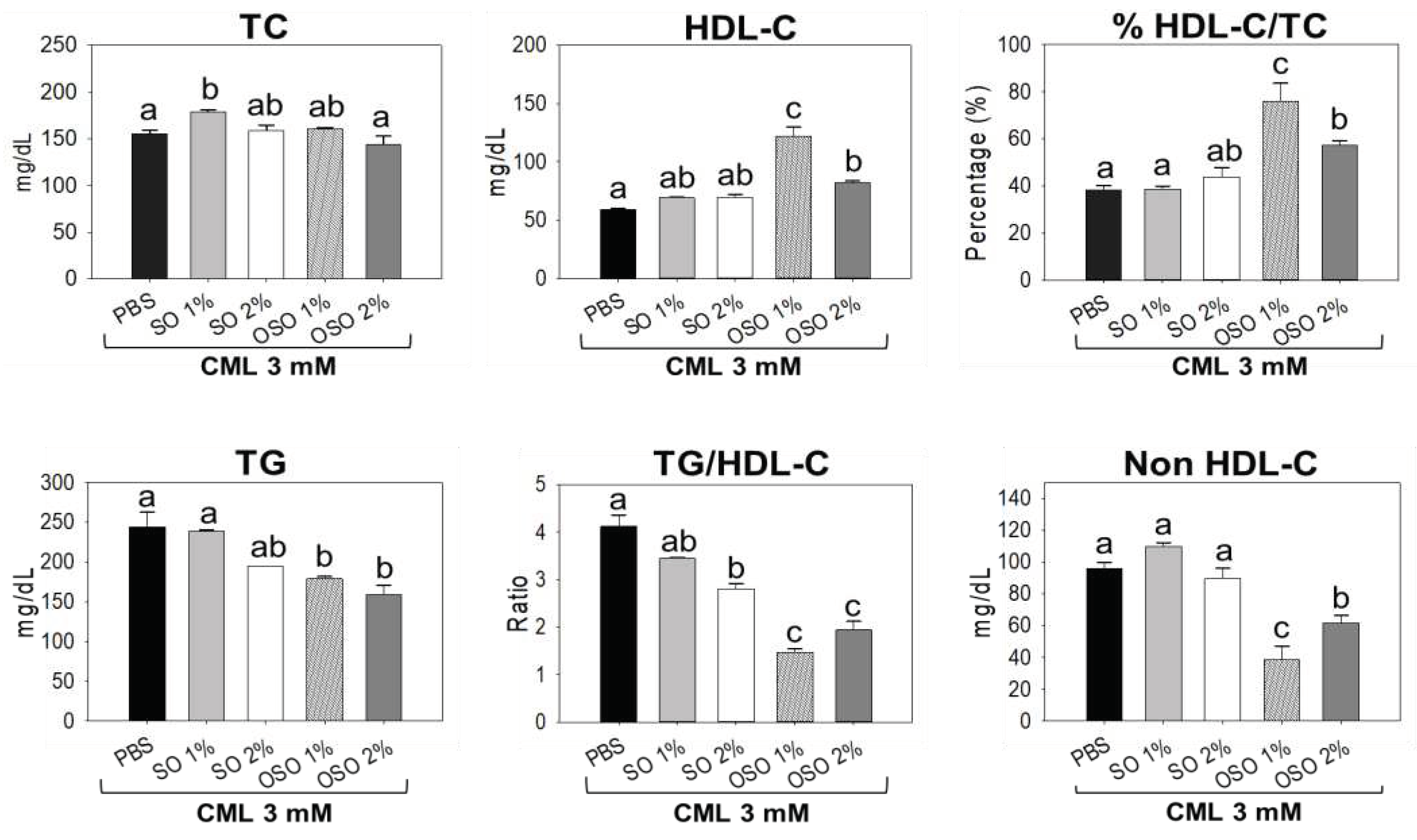

The OSO efficiently curtailed the TG, TC, and non-HDL-C and enhanced the HDL-C level, thus impact against CML-induced dyslipidemia. We assumed that diminished IL-6 production in response to OSO is the key event that balances the serum lipid profile. The notion following preceding reports suggests an association of IL-6 with an altered lipid profile [

48,

49]. In inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), elevated IL-6 levels are allied with decreased HDL-C and HDL-associated protein apoA-1 [

48,

50]. Similarly, augmented TC and alleviated levels of HDL were witnessed in psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [

49]. Many curative drugs for psoriasis, SLE, and RA balance the blood lipid profile, signifying a correlation between inflammation and serum lipid profile [

49]. Herein it was perceived that OSO inhibits the IL-6 production, which consequently amends dyslipidemia, precisely elevating HDL level.

Elevated HDL can be correlated with wound healing, as many recent reports established an association between HDL and chronic wound healing via modulation of inflammation [

51]. Perpetually, one clinical study also defines a correlation between endogenous HDL and diabetic wound healing [

52]. In addition, tropical application of HDL was found competent to cure diabetic and non-diabetic wounds [

53,

54]. These reports strengthen the current findings that OSO’s impact on HDL can prompt wound healing. More interestingly, in our previous study, we documented the influence of OSO on the structural alteration of HDL

3 [

18], leads to the amelioration of paraoxonase-1 functionality, an important biomarker to balance oxidative stress and inflammation [

55], strengthening the notion that OSO, due to HDL

3 structural alteration and elevating HDL level stimulates chronic wound healing.

Figure 1.

The comparative healing effect of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) against carboxymethyllysine (CML) exposed cutaneous wound in adult zebrafish. (A) Pictorial representation of wound stained with methylene blue (0.1% w/v) and pigment formation during 264 h post-treatment. The red arrow implies the pigment formation in the wounded area, while the blue arrow represents the wound scar. (B) Percentage wound closer during 264 h post-treatment. The percentage of the wound closer was computed by comparing the stained wound area measured at different times with respect to the wound area at 0 h. The PBS control group received a topical dose of PBS only, CML+PBS groups received a topical dose of CML (25 μg) dissolved in PBS, while the CML+SO2% and CML+OSO2% groups were co-treated with CML (25 μg) with SO 2% and OSO 2%, respectively. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate the statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time. .

Figure 1.

The comparative healing effect of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) against carboxymethyllysine (CML) exposed cutaneous wound in adult zebrafish. (A) Pictorial representation of wound stained with methylene blue (0.1% w/v) and pigment formation during 264 h post-treatment. The red arrow implies the pigment formation in the wounded area, while the blue arrow represents the wound scar. (B) Percentage wound closer during 264 h post-treatment. The percentage of the wound closer was computed by comparing the stained wound area measured at different times with respect to the wound area at 0 h. The PBS control group received a topical dose of PBS only, CML+PBS groups received a topical dose of CML (25 μg) dissolved in PBS, while the CML+SO2% and CML+OSO2% groups were co-treated with CML (25 μg) with SO 2% and OSO 2%, respectively. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate the statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time. .

Figure 2.

Comparative effect of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) on skin morphology and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production on carboxymethyllysine (CML) treated cutaneous wound in adult zebrafish. (A) and (C) Portray Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining at 72 h- and 168 h post-treatment. The black and blue arrows represent the granulation and muscular tissue, respectively. (B) and (D) Portray dihydroethidium (DHE) staining for ROS production at 72 h- and 168 h post-treatment. The PBS (control) group revied a topical application of PBS only, CML+PBS groups received a topical dose of CML (25 μg) dissolved in PBS, while the CML+SO2% and CML+OSO2% groups were co-treated with CML (25 μg) with SO 2% and OSO 2%, respectively. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate a statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time.

Figure 2.

Comparative effect of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) on skin morphology and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production on carboxymethyllysine (CML) treated cutaneous wound in adult zebrafish. (A) and (C) Portray Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining at 72 h- and 168 h post-treatment. The black and blue arrows represent the granulation and muscular tissue, respectively. (B) and (D) Portray dihydroethidium (DHE) staining for ROS production at 72 h- and 168 h post-treatment. The PBS (control) group revied a topical application of PBS only, CML+PBS groups received a topical dose of CML (25 μg) dissolved in PBS, while the CML+SO2% and CML+OSO2% groups were co-treated with CML (25 μg) with SO 2% and OSO 2%, respectively. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate a statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time.

Figure 3.

A comparative tail fin regenerative effect of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) in carboxymethyllysine (CML) injected adult zebrafish. (A) Morphology of tail fin amid 7 days post-treatment. The red dotted line indicates the regenerated tissue at the proximal end. (B) kinetics of tail fin regenerated area. The PBS group was microinjected with PBS (vehicle), and the CML+PBS group was microinjected with CML (3 mM) dissolved in PBS. CML+SO 2% and CML+OSO 2% groups were microinjected with CML (3 mM) together with SO 2% and OSO2%, respectively. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate the statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time.

Figure 3.

A comparative tail fin regenerative effect of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) in carboxymethyllysine (CML) injected adult zebrafish. (A) Morphology of tail fin amid 7 days post-treatment. The red dotted line indicates the regenerated tissue at the proximal end. (B) kinetics of tail fin regenerated area. The PBS group was microinjected with PBS (vehicle), and the CML+PBS group was microinjected with CML (3 mM) dissolved in PBS. CML+SO 2% and CML+OSO 2% groups were microinjected with CML (3 mM) together with SO 2% and OSO2%, respectively. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate the statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time.

Figure 4.

A comparative swimming behavior and survivability of zebrafish injected with carboxymethyllysine (CML) and subsequently treated with sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO). (A) Zebrafish survivability at 60 min post-injection. (B) Mean value of percentage swimming activity and (C) Snapshots of swimming activity at 30 min and 60 min post-injection. The CML+PBS group was injected with CML (250 μg) dissolved in PBS, whereas CML+(SO1%, SO2%, OSO1%, and OSO2%) groups were co-injected with CML (250 μg) along with either SO1% or SO2% or OSO1% or OSO2%. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate the statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time.

Figure 4.

A comparative swimming behavior and survivability of zebrafish injected with carboxymethyllysine (CML) and subsequently treated with sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO). (A) Zebrafish survivability at 60 min post-injection. (B) Mean value of percentage swimming activity and (C) Snapshots of swimming activity at 30 min and 60 min post-injection. The CML+PBS group was injected with CML (250 μg) dissolved in PBS, whereas CML+(SO1%, SO2%, OSO1%, and OSO2%) groups were co-injected with CML (250 μg) along with either SO1% or SO2% or OSO1% or OSO2%. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate the statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time.

Figure 5.

Histology of hepatic tissue deciphering a comparative effect of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) on hepatic morphology, fatty liver changes, oxidative stress, and IL-6 production in carboxymethyllysine (CML) injected adult zebrafish at 60 min post-injection.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The black, blue, and red arrows represent the bile duct, arterial area, and portal vein.

(B) Oil red O staining.

(C) DHE staining for reactive oxygen species detection.

(D) IL-6 production [detected by immunocytochemistry (IHC)]. The depicted images are 400× magnified [graphic scale=0.1 mm], and the stained area was computed employing Image J software (version 1.53,

http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/ retrieved on May 16, 2022). The CML+PBS group was injected with CML (3 mM) dissolved in PBS, whereas CML+(SO1%, SO2%, OSO1%, and OSO2%) groups were co-injected with CML (3 mM) along with either SO1% or SO2% or OSO1% or OSO2%.

P value documented the pairwise statistical variation retrieved from the ANOVA employing the Turkey’s test for post hoc analysis.

Figure 5.

Histology of hepatic tissue deciphering a comparative effect of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) on hepatic morphology, fatty liver changes, oxidative stress, and IL-6 production in carboxymethyllysine (CML) injected adult zebrafish at 60 min post-injection.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The black, blue, and red arrows represent the bile duct, arterial area, and portal vein.

(B) Oil red O staining.

(C) DHE staining for reactive oxygen species detection.

(D) IL-6 production [detected by immunocytochemistry (IHC)]. The depicted images are 400× magnified [graphic scale=0.1 mm], and the stained area was computed employing Image J software (version 1.53,

http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/ retrieved on May 16, 2022). The CML+PBS group was injected with CML (3 mM) dissolved in PBS, whereas CML+(SO1%, SO2%, OSO1%, and OSO2%) groups were co-injected with CML (3 mM) along with either SO1% or SO2% or OSO1% or OSO2%.

P value documented the pairwise statistical variation retrieved from the ANOVA employing the Turkey’s test for post hoc analysis.

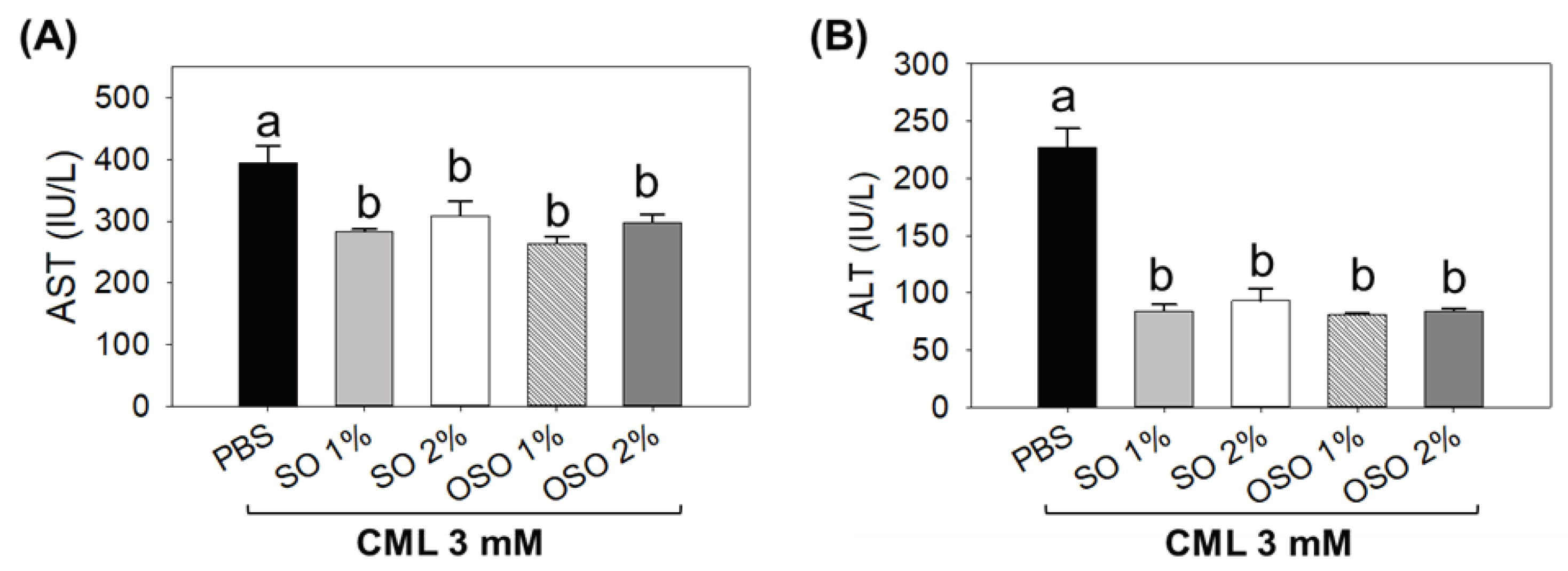

Figure 6.

Effect of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) on the liver function biomarkers (A) Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and (B) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in carboxymethyl lysine (CML) injected adult zebrafish. The CML+PBS group was injected with CML (3 mM) dissolved in PBS, whereas CML+(SO1%, SO2%, OSO1%, and OSO2%) groups were co-injected with CML (3 mM) along with either SO1% or SO2% or OSO1% or OSO2%. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate the statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time.

Figure 6.

Effect of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) on the liver function biomarkers (A) Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and (B) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in carboxymethyl lysine (CML) injected adult zebrafish. The CML+PBS group was injected with CML (3 mM) dissolved in PBS, whereas CML+(SO1%, SO2%, OSO1%, and OSO2%) groups were co-injected with CML (3 mM) along with either SO1% or SO2% or OSO1% or OSO2%. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate the statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time.

Figure 7.

Comparative analysis of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) on blood lipid profile of the carboxymethyl lysine (CML) injected adult zebrafish. The CML+PBS group was injected with CML (3 mM) dissolved in PBS, whereas CML+(SO1%, SO2%, OSO1%, and OSO2%) groups were co-injected with CML (3 mM) along with either SO1% or SO2% or OSO1% or OSO2%. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate the statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time. The TC, HDL-C, and TG are acronyms for total cholesterol, triglyceride, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Figure 7.

Comparative analysis of sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO) on blood lipid profile of the carboxymethyl lysine (CML) injected adult zebrafish. The CML+PBS group was injected with CML (3 mM) dissolved in PBS, whereas CML+(SO1%, SO2%, OSO1%, and OSO2%) groups were co-injected with CML (3 mM) along with either SO1% or SO2% or OSO1% or OSO2%. The letters (a-b) above the graphs indicate the statistical difference (p<0.05) among the groups at the given time. The TC, HDL-C, and TG are acronyms for total cholesterol, triglyceride, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

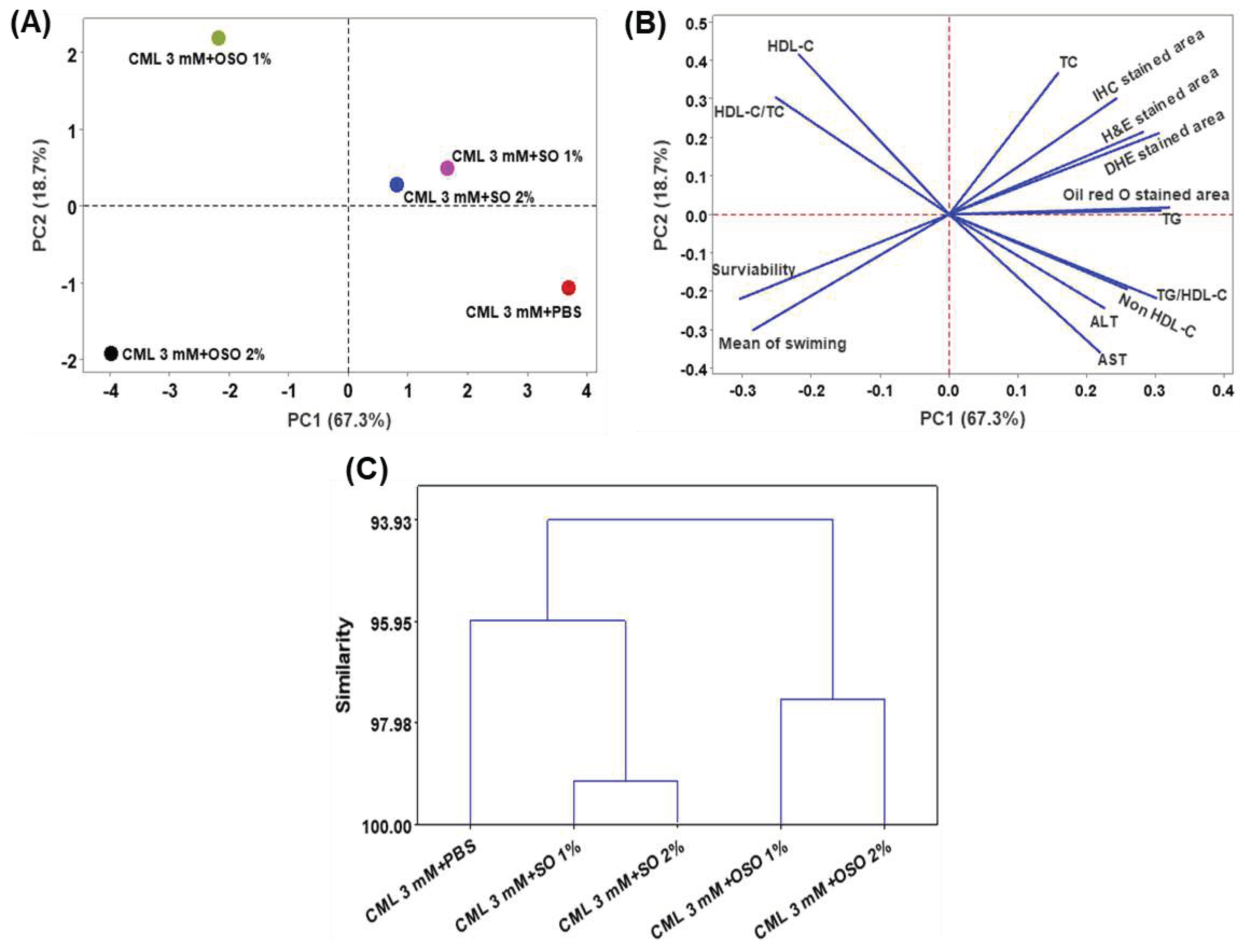

Figure 8.

Multivariate analysis based on tested parameters (survivability, swimming, liver function biomarkers, histology, and blood lipid profile) of zebrafish stimulated by carboxymethyllysine (CML) and subsequently treated with sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO). (A) and (B) are the scoring plot and loading plot, respectively, obtained from principal component analysis (PCA). (C) Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA). The PCA and HCA were performed using Minitab statistical software version 21.4. The CML+PBS group was injected with CML (3 mM) dissolved in PBS, whereas CML+(SO1%, SO2%, OSO1%, and OSO2%) groups were co-injected with CML (3 mM) and SO1% or SO2% or OSO1% or OSO2%. AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride. .

Figure 8.

Multivariate analysis based on tested parameters (survivability, swimming, liver function biomarkers, histology, and blood lipid profile) of zebrafish stimulated by carboxymethyllysine (CML) and subsequently treated with sunflower oil (SO) and ozonated sunflower oil (OSO). (A) and (B) are the scoring plot and loading plot, respectively, obtained from principal component analysis (PCA). (C) Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA). The PCA and HCA were performed using Minitab statistical software version 21.4. The CML+PBS group was injected with CML (3 mM) dissolved in PBS, whereas CML+(SO1%, SO2%, OSO1%, and OSO2%) groups were co-injected with CML (3 mM) and SO1% or SO2% or OSO1% or OSO2%. AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride. .

Figure 9.

Summary of ozonated sunflower (OSO) mediated events that counters cabboxymethyllysine (CML) impelled hazards leads to cutaneous wound healing, tissue regeneration and hepatoprotection in zebrafish.

Figure 9.

Summary of ozonated sunflower (OSO) mediated events that counters cabboxymethyllysine (CML) impelled hazards leads to cutaneous wound healing, tissue regeneration and hepatoprotection in zebrafish.