1. Introduction

The understanding of blooms involving gelatinous zooplankton remains limited, mainly because they are not commonly the focus of fisheries and oceanographic research efforts, resulting in a dearth of information about their origins and causes (Licandro et al., 2010; Canepa et al., 2020). The excessive proliferation of these species can negatively affect marine ecosystems’ stability through excessive predation and have adverse consequences for human activities such as tourism and fisheries, as usually these blooms are composed of stinging species (Purcell and Arai, 2001; Canepa et al., 2014). Among the gelatinous zooplankton species, Valella valella, Porpita porpita, and Physalis physalis are frequent contributors to the blooms found stranded on coasts, propelled by wind and currents (Graham et al., 2001; Canepa et al., 2020).

P. physalis, commonly called Portuguese man-of-war, is a cosmopolitan colony formed by specialized zooids, a pneumatophore, and tentacles that have stinging cells (cnidocysts) with toxins to paralyze prey and that are powerful enough to harm humans gravely (Burnett et al., 1994). It is an effective predator, comprising fish larvae up to 90% of their diet (Purcell, 1984). Gut contents analyses of colonies collected in the Gulf of Mexico and the Sargasso Sea showed that one colony consumes an average of 120 fish larvae daily (Purcell, 1984). Thus, when P. physalis is in high quantities, excessive predation can affect the marine ecosystem’s stability (Mitchell et al., 2021). P. physalis is also among the worst stinging species in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans affecting tourist and fishery activities (Canepa et al., 2020). Its sting can cause cardiac, neurological, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and allergic reactions in humans (Martínez et al., 2010; Mitchell et al., 2021).

Strandings of

P. physalis are common on the coasts but usually in low quantities (Torres-Conde et al., 2022). For example, between 1914 and 2021, less than 200 beach cast colonies per year were reported for the Mediterranean Sea (Badalamenti et al., 2021), while on the northwestern coast of Cuba, annual densities from 2018 to 2021 were estimated at less than 150 colonies/100m (Torres-Conde and Martínez-Daranas, 2020; Torres-Conde et al., 2022). Scientific reports of massive strandings of this species are scarce (

Table 1), most likely because these events are sporadic and primarily triggered by unusual meteorological and oceanographic conditions often associated with climate change.

Gelatinous zooplankton blooms have been associated with environmental factors, such as light, temperature, salinity, and food availability (Purcell et al., 2012), while onshore strandings are known to be influenced by wind and wave direction, as well as the geomorphology of the shoreline (Potin et al., 2011; Torres-Conde et al., 2021; Bourg et al., 2022). In the case of P. physalis strandings, the speed and direction of the wind have been identified as the primary factors for predicting the source of the bloom, as the pneumatophore acts as a sail that can be oriented left or right (Woodcock, 1944; Totton and Mackie, 1960; Ferrer and Pastor, 2017). The Arctic Oscillation index (AOi), the North Arctic Oscillation index (NAOi), and El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) have been used as indicators for predicting strandings. These indices demonstrate stochastic variations between positive and negative phases and are associated with climate variations in middle and high latitudes (Prieto et al., 2015; Torres-Conde, 2022).

In this study, we describe the largest documented beaching event of P. physalis and examine the climatic conditions that could have favored their transport to the northwestern coast of La Habana, Cuba, in December 2022. The results should raise awareness within the scientific community to monitor P. physalis strandings along the Atlantic coast, considering the risk they represent to human populations, tourism, and fisheries, particularly because increments in jellyfish populations are often associated with warming caused by climate change and eutrophication (Purcell et al., 2007).

2. Methods

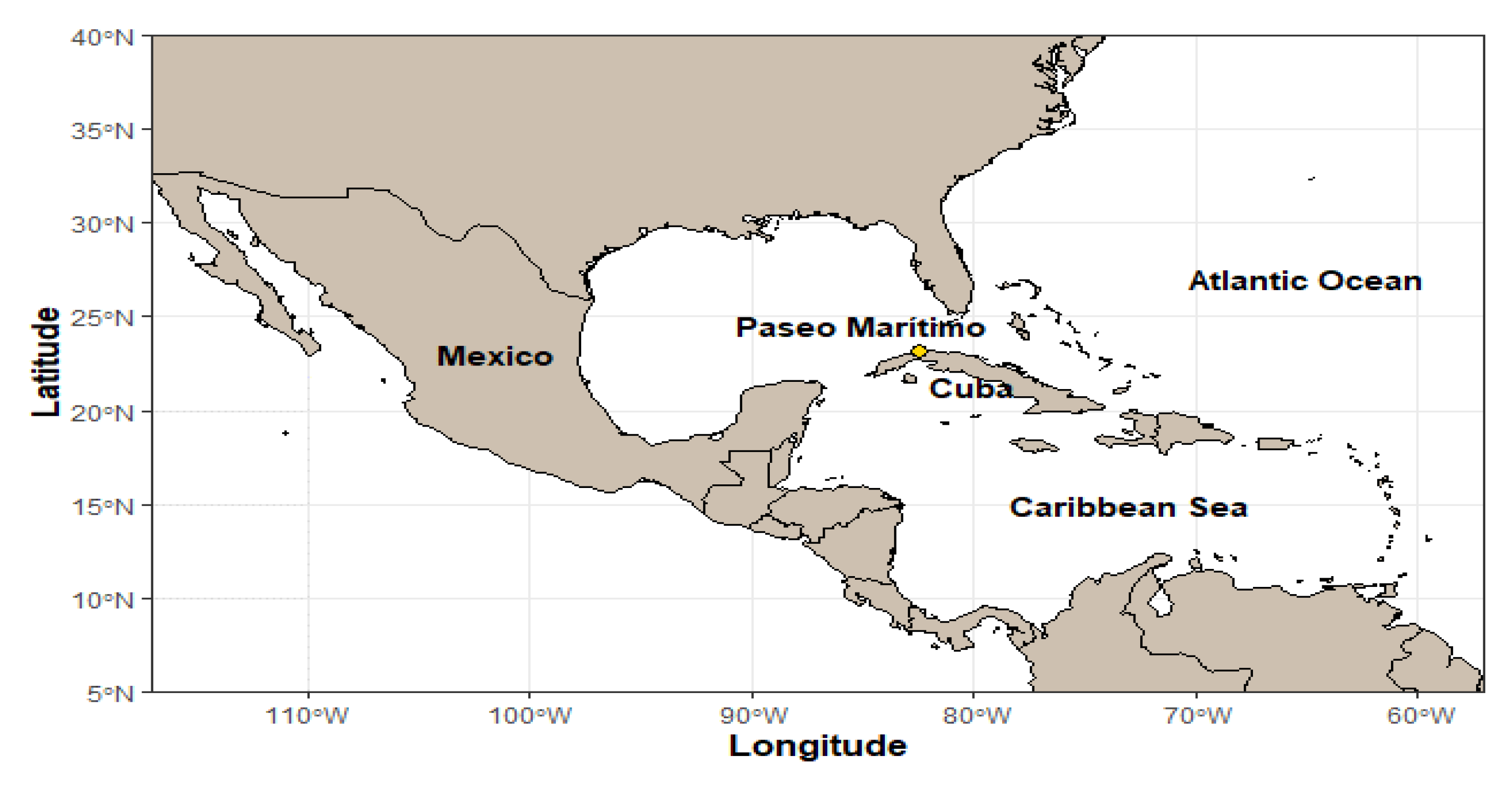

Data on a

P. physalis stranding event in December 2022 were obtained in La Habana (23

06′ 49.759′’N, 82

o26′24.072′’W), northwestern coast of Cuba, by sampling ~ 3 km of the littoral of Paseo Marítimo, from streets 1st on the east to the west (

Figure 1). The beach is dominated by rocky supralittoral and sublittoral and an abrasive rocky zone down to the terrace edge, where there is a continuous coral reef that extends to a depth of 20 m (Zlatarski and Martínez-Estalella, 1980; Caballero and de la Guardia, 2003). The dominant winds are from the northern component in the dry season and the east in the rest of the months (Martínez, 1983; Torres-Conde, 2022). The coastal area is urbanized. Locals and tourists visit the beach and coastal waters to swim, snorkel, and dive. Data on the number of people affected by

P. physalis stinging in the study area during the bloom event was provided by the Instituto de Ciencias del Mar-ICIMAR from la Habana, Cuba.

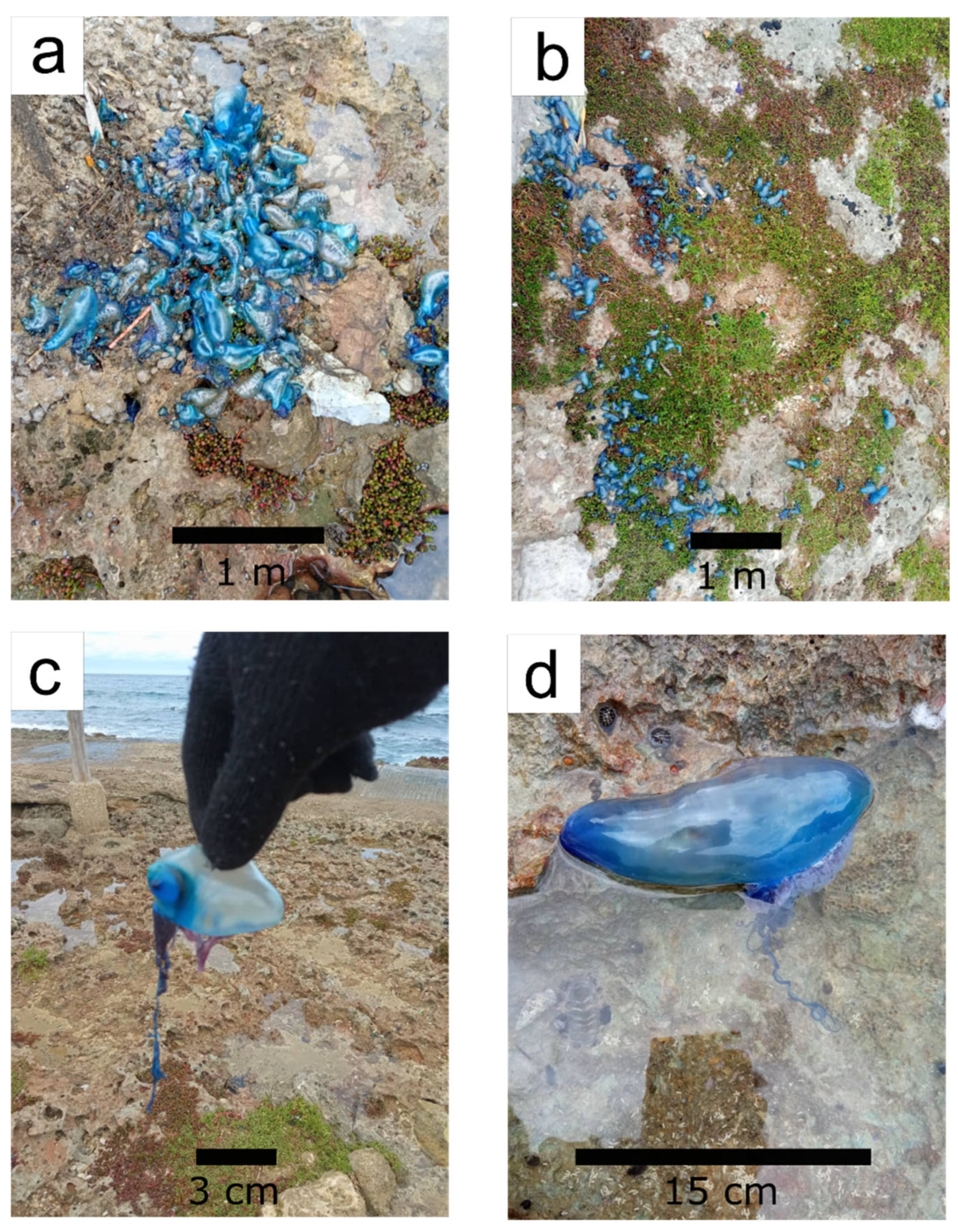

Samplings were conducted between the 27th and 31st of December 2022, when the massive arrival of

P. physalis occurred (

Figure 2 a-b). All colonies along the ~3 km coast were counted in a ~5 m wide stripe. Additionally, 0.25 m

2 quadrats were placed every 50 m along the beach 10 m from the shoreline to quantify the density, the percentage of each dimorphic form (left-handed or right-handed), and the size of the colonies (accuracy = 1 mm). Colony density was standardized to a square meter. Possible differences in the frequency of

P. physalis among dimorphic forms and size were tested with a chi-square test. A post hoc analysis for Pearson’s chi-squared test was used for paired comparison. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all tests. All analyses and graphics were done in R (R Core Team 2023) using packages: ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016), ggpubr (Kassambara, 2020), and GAD (Sandrini-Neto and Camargo, 2012).

Wind direction, wave height and direction, and air temperature were obtained for the eight days before the massive beaching of

P. physalis from the Windguru website (

https://www.windguru/cz/). The climatic situation for the month of the arrival was obtained from the monthly summaries of the Cuban Meteorology Institute (

https://www.insmet.cu). The daily Arctic Oscillation Index (AOi) and the North Atlantic Oscillation Index (NAOi) for the month of the massive beaching (December 2022) were attained from the database of the United States Climate Prediction Center (

www.cpc.ncep.noaa.goc) (CPC, 2023) (Supplementary

Table 1).

3. Results and Discussion

Between December 27th and 31st, 2022, 85 individuals, including tourists, experienced

P. physalis stings at the study site, with 38 suffering severe allergic reactions. No fatalities were reported. Along the studied shoreline, 10,441

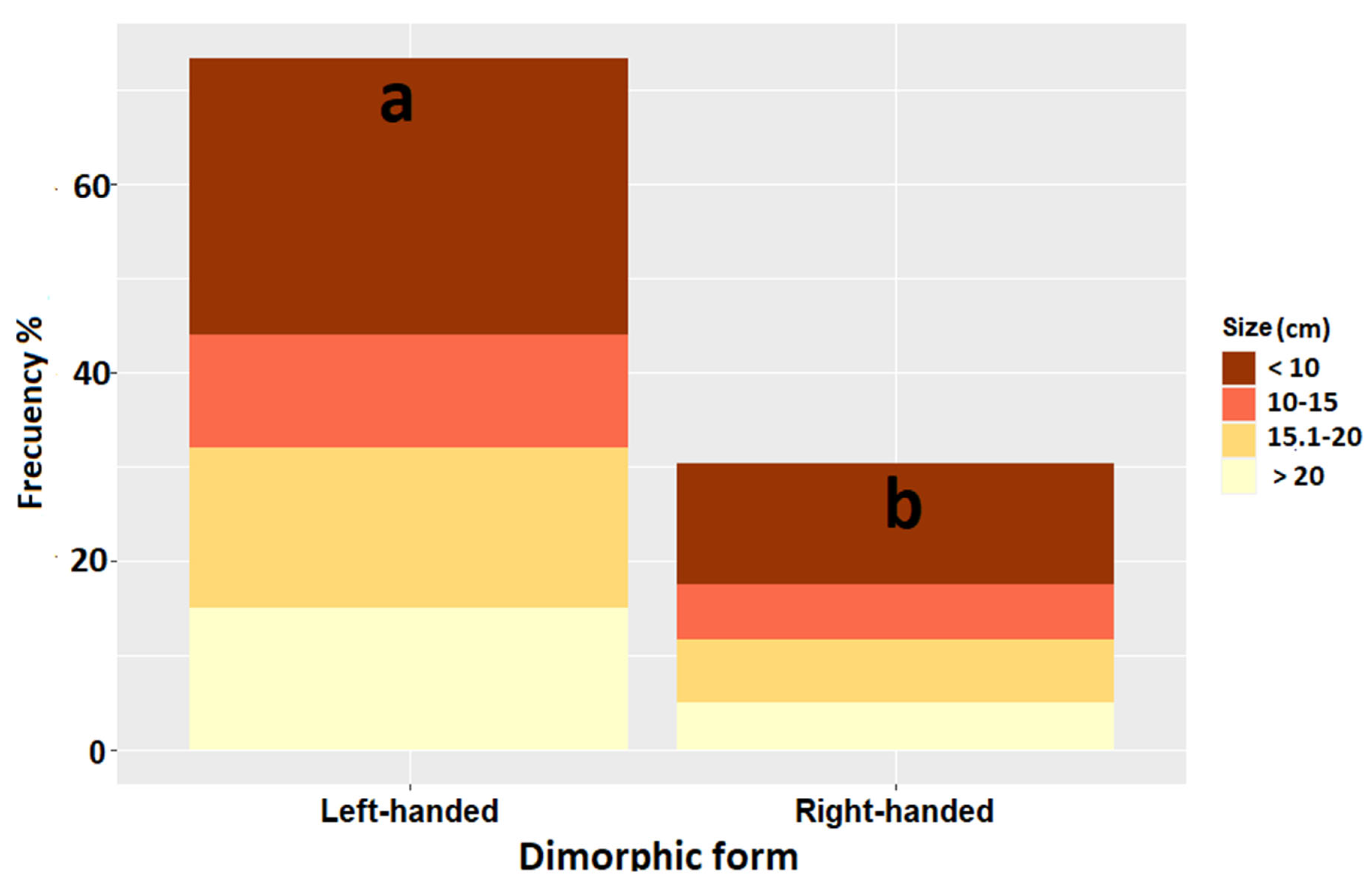

Physalia physalis colonies were recorded (~345 colonies per 100 m). The average colony density was 29.3 per m² (SE: 30.2). Statistical significant differences in the frequency of

P. physalis were found between the dimorphic forms (χ-squared= 31.48, df = 1, p = 0.001) and sizes (χ-squared= 18.21, df = 3, p = 0.008). Left-handed colonies were more prevalent (71.4%) than right-handed colonies (28.6%), with 68.8% of the total being in a juvenile state (≤ 10 cm) (

Figure 2c-d,

Figure 3). A week before the strandings, the prevailing winds and waves were northeasterly, with a mean wind speed of 12.1 km/h, a mean wave height of ~1 m, mean air temperature of 22.3 °C, and mean water temperature of 27.4 °C (

Table S1). The Arctic and North Atlantic Oscillation indices displayed negative values (AOi: -2.59; NAOi: -0.13) (

Table S2). Four days before the strandings (December 24, 2022), a cold front reached the coast of La Habana, bringing northeasterly winds reaching 24 km/h, an average wave height of 1.5 m, and an average air temperature of 19 °C.

The number of P. physalis colonies that washed ashore during the last week of December of 2022 was two to seven times higher than the annual records (range: 44-145 per 100 m) along the northwestern coast of Cuba in previous surveys (Torres-Conde et al., 2021; Torres-Conde, 2022). The density of strandings was also significantly higher than that reported in other massive swarm events of the Portuguese Man-of-War. For instance, from February 2010, 10,373 P. physalis colonies were stranded along ~50 km of Doñona National Park in Spain (~20 colonies per 100 m). This event was likely influenced by unique climatic conditions during the previous winter, including a negative NAOi (-4.64) and anomalous strong westerly winds (Prieto et al., 2015). Also, in 2010, over 3,500 colonies arrived on the Basque coast in August (~1.4 colonies per 100 m), possibly due to a combination of west-southwesterly and northwesterly winds between August 2009 and August 2010 (Ferrer and Pastor, 2017). In the summer of 2015, another massive stranding event occurred in Chile’s central and south-central coast, associated with the Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), where nearly 200 people were stung; the density of stranded colonies (1 colony per 100 m; Canepa et al., 2020) was considerably lower than the one recorded in the present study.

Our data suggest that the arrival of the Portuguese Man-of-War in large numbers along Cuba’s northwestern coast was facilitated by specific meteorological and oceanographic conditions, primarily driven by the most negative mean AOi in the past 11 years (CPC, 2023). Negative AOi values promote the influx of cold fronts with robust northeasterly winds and low air temperatures from high latitudes to mid-latitudes (Thompson and Wallace, 2001; Thompson et al., 2003; Cedeño, 2015). Previous studies by Torres-Conde et al. (2021) and Torres-Conde (2022) have established an association between P. physalis and holopelagic Sargassum spp. strandings on the northwestern coast of Cuba with a negative AOi phase, cold fronts, and moderately strong northeasterly winds (> 18 km/h), which align with the conditions observed in the current study.

The dimorphic form of P. physalis is used to predict the source of stranded colonies (Ferrer and González, 2020). Ferrer and Pastor (2017) propose the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre (NASG), encompassing the Sargasso Sea, as the primary source of P. physalis strandings along Atlantic Ocean coasts. Our results support this hypothesis as a higher percentage of left-handed colonies were stranded in La Habana in December 2022, influenced by predominantly northeast winds and waves. The high prevalence of juvenile colonies likely corresponds to the breeding season of P. physalis, which typically occurs in autumn in the northern hemisphere (between September and December; Ferrer and González, 2020). The small left-handed colonies were likely carried from the NASG towards the north coast of Cuba by a combination of wind and current conditions generated by an unusually negative NAOi.

Global climate change has caused abrupt and abnormal behaviors in the NAOi, AOi, and ENSO patterns, which in turn influence meteorological conditions with changes in temperature, wind, and currents, which alter the distribution of marine species in the Atlantic Ocean (Fromentin and Planque, 1996; Thompson and Wallace, 2001; Prieto et al., 2015; Marx et al., 2021). One notable case is the extensive strandings of the holopelagic Sargassum spp. in the Caribbean, with high ecological, economic, and human-health-related repercussions (van Tussenbroek et al., 2017; Rodríguez-Martínez et al., 2023). Similarly to the holopelagic Sargassum, climate change and eutrophication may play a role in P. physalis blooms (Hanisak and Samuel, 1987; Purcell et al., 2012; Brooks et al., 2018; Bourg et al., 2022). However, further research is needed to assess the environmental conditions that favor the reproduction of P. physalis and the occurrence of blooms. Not enough historical data is available to determine if P. physalis is increasing its distribution and abundance and if blooms are becoming more frequent.

The high density of P. physalis that was stranded on the northwestern coast of Cuba in 2022 and the risk it implies for human health should serve as a warning to the scientific community about the importance of implementing systematic monitoring efforts along the Atlantic coasts to gain a comprehensive understanding of the distribution and influx patterns of P. physalis. Climate change and eutrophication could turn isolated blooms of P. physalis into recurring events and affect a higher number of countries and territories. For example, in February 2023, strandings of P. physalis with a density of 20 colonies per 100 m occurred in a 70 km coastal stripe in the north of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, where historically only isolated colonies were observed sporadically (Aldana-Arana, pers. comm.). Monitoring initiatives will provide invaluable insights, enhance prediction capabilities, and effectively manage future massive strandings in coastal regions. Monitoring initiatives should also include the Sargasso Sea to comprehend the specific conditions that may be responsible for the occurrence of P. physalis blooms in the Atlantic.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author contribution: “EGTC, RERM, conceived and designed the research; EGTC, performed the experiments; EGTC, RERM, wrote and edited the manuscript.” All authors contributed critically to drafts and gave final approval for publication. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The first author thanks El Programa de Doctorado del Posgrado de Ciencias Biólogicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Teconología (CONAHCYT) for the doctorate grant. We thank Instituto de Ciencias del Mar-ICIMAR from la Habana, Cuba, for providing the data on the number of people affected by P. physalis stinging, and Dr. Dalila Aldana-Arana for the P. physalis estimated densities in the northern coast of the Yucatan Peninsula.

References

- Badalamenti, R., Tiralongo, F., Arizza, V., Lo Brutto, S., 2021. The Portuguese man-of war one of the most dangerous marine species, has always entered the Mediterranean Sea: standings, sightings and museum collections. Res. Sq. (preprint). [CrossRef]

- Bourg, N. , Schaeffer, A., Cetina-Heredia, P., Lawes, J.C., Lee D., 2022. Driving the blue fleet: Temporal variability and drivers behind bluebottle (Physalia physalis) beachings off Sydney, Australia. PLoS ONE. 17(3): e0265593. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.T. , Coles, V.J., Hood, R.R., Gower, J.F.R., 2018. Factors controlling the seasonal distribution of pelagic Sargassum. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 599, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Burnett, J.W. , Fenner, P.J., Kokelj, F., Williamson, J.A. 1994. Serious Physalia (Portuguese man o’war) stings: implications for scuba divers. J. Wilderness Med. 5, 71-76. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, H. , de la Guardia, E., 2003. Arrecifes de coral utilizados como zonas de colectas para exhibiciones en el Acuario Nacional de Cuba. I. Costa noroccidental de La Habana. Rev. Invest. Mar. 24 (3), 205–220.

- Canepa, A., Fuentes, V., Sabatés, A., Piraino, S., Boero, F., Gili, J.-M., 2014. Pelagia noctiluca in the Mediterranean Sea. In: Pitt, K.A. & Lucas, C.H. (Eds.). Jellyfish blooms. Springer Science Business Media, Dordrecht, pp. 237–265.

- Canepa, A. , Purcell, J.E., Córdova, P., Fernández, M., Palma, S., 2020. Massive strandings of pleustonic Portuguese Man-of-War (Physalia physalis) related to ENSO events along the southeastern Pacific Ocean. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 48(5), 806-817. [CrossRef]

- Cedeño, A.R. , 2015. Oscilación Ártica y frentes fríos en el occidente de Cuba. Rev. Cub. Meteorol. 21 (1), 91–102.

- CPC., 2023. Climate Prediction Center web. Washington, United States of America. NAOi data: https://ftp.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/cwlinks/norm.daily.nao.index.b500101.current.ascii and AOi data: https://ftp.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/cwlinks/norm.daily.ao.index.b500101.current.ascii. (Accessed 10 June 2023).

- Ferrer, L. , Pastor, A., 2017. The Portuguese man-of-war: Gone with the wind. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 14, 53-62. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, L. , Gonzalez, M., 2020. Relationship between dimorphism and drift in the portuguese man-of-war. Cont. Shelf. Res. 212(2021), 104268. [CrossRef]

- Fierro, P. , Arriagada, L., Piñones, A., Araya, J.F., 2021. New insights into the abundance and seasonal distribution of the Portuguese man-of-war Physalia physalis (Cnidaria: Siphonophorae) in the southeastern Pacific. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 41 (2021) 101557. [CrossRef]

- Fromentin, J.M. , Planque, B., 1996. Calanus and environment in the eastern North Atlantic. II. Influence of the north Atlantic oscillation on C. finmarchicus and C. helgolandicus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 134, 111–118. [CrossRef]

- Graham, W.M. , Pagès, F. Hamner, W.M., 2001. A physical context for gelatinous zooplankton aggregations: a review. Hydrobiologia. 451, 199-212. [CrossRef]

- Hanisak, M.D. , Samuel, M.A., 1987. Growth rates in culture of several species of Sargassum from Florida, USA. Hydrobiology 151, 399–404. [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A., 2020. Ggpubr:’ ggplot2’ based publication ready plots. https://cran. r-project.org/web/packages/ggpubr/index.html. (Accessed 10 February 2023).

- Licandro, P. , Conway, D.V.P., Yahia, D.M.N., Fernandez de Puelles, M.L., Gasparini, S., Hecq, J.H., Tranter, P., Kirby, R.R., 2010. A blooming jellyfish in the northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean. Biological Letters. 6, 688-691. [CrossRef]

- Lluis-Riera, M. , 1983. Régimen hidrológico de la plataforma insular de Cuba. Cien. de la Tierra y el Espacio. 7, 81–110.

- Martínez, R.M. , Zálvez, M.E.V., Jara, I.M., La Orden, J.M., 2010. Picadura por Carabela Portuguesa, una medusa algo especial. Rev. Clín. Med. Fam. 3 (2), 143–145.

- Marx, W. , Haunschild, R., Bornmann, L., 2021. Heat waves: a hot topic in climate change research. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 146, 781-800. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.O. , Bresnihan, S., Scholz, F., 2021. Mortality and skin pathology of farmed atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) caused by exposure to the jellyfish Physalia physalis in ireland. J. Fish Dis. 44(11), 1861–1864. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto, L. , Macías, D., Peliz, A., Ruiz, J., 2015. Portuguese Man-of-War (Physalia physalis) in the Mediterranean: a permanent invasion or a casual appearance? Sci. Rep. 5, 11545. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, J.E. , 1984. Predation on fish larvae by Physalia physalis, the Portuguese man of war. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Series. 19, 189-191.Purcell, J.E., Arai, M.N., 2001. Interactions of pelagic cnidarians and ctenophores with fish: a review. Hydrobiologia. 451, 27-44. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, J.E. , Uye, Sh., Lo, W., 2007. Anthropogenic causes of jellyfish blooms and their direct consequences for humans: a review. Mar. Ecol. Progr. Ser. 350, 153-174. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, J.E. , Atienza, D., Fuentes, V., Olariaga, A., Tilves, U., Colahan, C., Gili, J.-M., 2012. Temperature effects on asexual reproduction rates of scyphozoan polyps from the NW Mediterranean Sea. Hydrobiologia. 690, 169-180. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E. , Torres-Conde, E.G., Jordán-Dahlgren, E., 2023. Pelagic Sargassum cleanup cost in Mexico. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 237 (2023), 106542. [CrossRef]

- Sandrini-Neto, L., Camargo, M.G., 2012. GAD based publication ready plots. https:// https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/GAD/index.html. (Accessed 10 February 2023).

- Thompson, D.W.J. , Wallace, J.M., 2001. Regional climate impacts of the northern hemisphere annular mode. Science. 293, 85–89. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.W.J. , Lee, S., Baldwin, M.P., 2003. Atmospheric processes governing the northern hemisphere annular mode/North Atlantic oscillation. In: Hurrel, J.W., Kushnir, Y., Ottersen, G., Visbeck, M. (Eds.), The North Altantic Oscillation: Climatic Significance and Environmental Impact, vol. 134. Geophys. Monogr. Ser. 134, 81–112. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Conde, E.G. , Martínez-Daranas, B., 2020. Oceanographic and spatio-temporal analysis of pelagic Sargassum drift in PLyas del Este, La Habana, Cuba. Rev. Invest. Mar. 40 (1), 22-41.

- Torres-Conde, E.G. , Martínez-Daranas, B., Prieto, L., 2021. La Habana littoral, an area of distribution for Physalia physalis within the Atlantic Ocean. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 44, 101752. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Conde, E.G. 2022. Is simultaneous arrival of pelagic Sargassum and Physalia physalis a new threat to the Atlantic coast? Estuar. Coast. Shelf. Sci. 275(2022), 107971.

- Totton, A. , Mackie, G., 1960. “Studies on Physalia physalis”, discover. For. Rep. 30, 301–340.

- Van Tussenbroek, B.I. , Hernández-Arana, H.A., Rodríguez-Martínez, R.E., Espinoza-Avalos, J., Canizales-Flores, H.M., González-Godoy, C.E., Barbara-Santos, M.G., Vega-Zepeda, A., ColladoVides, L., 2017. Severe impacts of brown tides caused by Sargassum spp. on near-shore Caribbean seagrass communities. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 272, 281. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H., 2016. Ggplot2 based publication ready plots. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org. (Accessed 6 June 2023).

- Woodcock, A.H. , 1944. A theory of surface water motion deduced from the wind-induced motion of the Physalia. J. Mar. Res. 5, 196–205.

- Zlatarski, V.N. , Martínez-Estalella, N., 1980. Escleractinios de Cuba con datos sobre sus organismos asociados (en ruso). Editorial Academia de Bulgaria, Sofía, Bulgaria.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).