1. Introduction

During the Cenozoic, the biogeographic provinces of Mexico were formed, and their current configuration is due to recent events such as volcanic activity starting at the Pliocene 5.33 million years ago (Ma) and continuing to the present [

1], movement of tectonic plates that closed the Isthmus of Panama (3 Ma) [

2] dropped of region's temperature between 7 and 5 ºC during the maximum glaciation, and the glacial cycles that promoted altitudinal movements of the biota during the Pleistocene 2.5-0.011 Ma [

3].These events generated a complex transition zone in Mexico, with consequences on soil formation, geological changes, and different precipitation ranges, consequently causing a complex assemblage of biota between nearctic and neotropical affinities as well as in situ speciation [4; 5]. In this scenario plant species evolved [e.g., 6] and habitats for phytophagous insects were generated.

According to the characterization of Morrone [

7], 14 biogeographic provinces in Mexico can be recognized because they combine climatic, geological, and biotic criteria. The biogeographic provinces represent historical entities of specific interactions of biota. The Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (TMVB) province has documented a higher diversity of ecosystems and species compared with other biogeographic provinces [7-9]. If there are more biotic interactions at TMVB one might expect there to be repercussions increasing the variation (phenotypic and genetic) in this area of a widely distributed species.

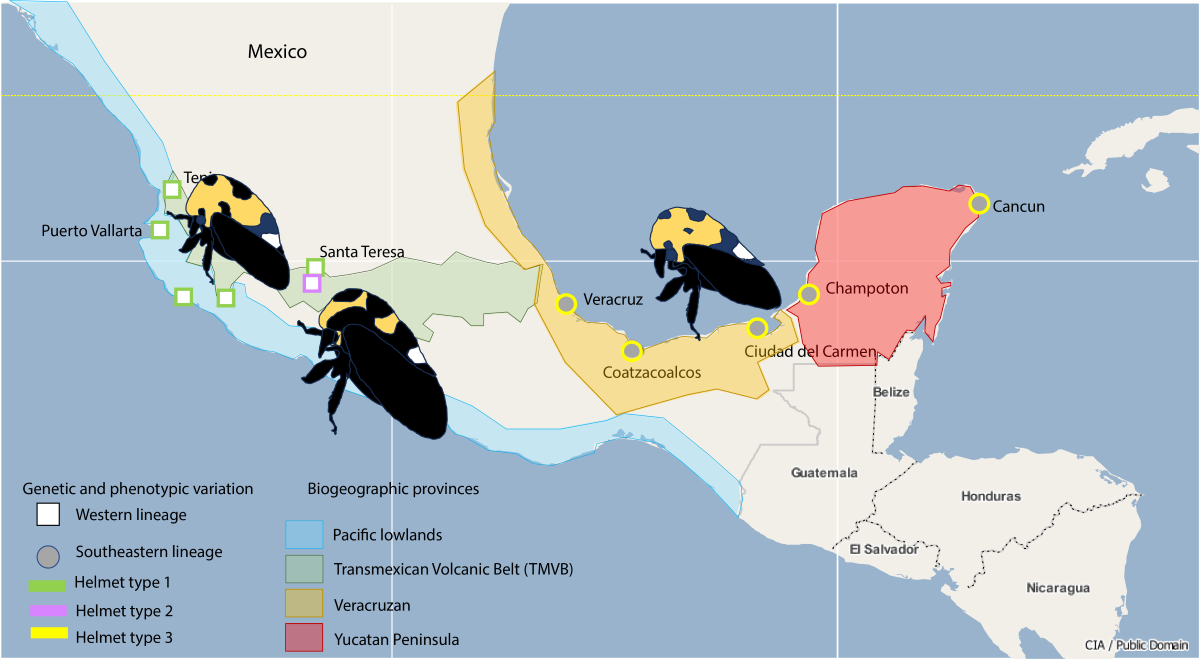

Here we investigate the intraspecific variation of the treehopper species Membracis mexicana distributed over four biogeographic provinces: the Pacific Coast, the TMVB, the Mexican Gulf, and the Yucatan Peninsula. We aimed to demonstrate phenotypic variation and phylogeographic patterns supported by the biogeographic provinces hoping to find more diversity at TMVB compared with other biogeographic provinces.

The Treehopper species (family Membracidae) are characterized by the shape of the helmet (complex three-dimensional structures that develop from the pronotum and cover the dorsal side of the insect). Species of the genus Membracis show intraspecific variation in the size and colors of the helmet, this variation has been attributed to the host plant, nutrition, temperature, and humidity [

10], but until now these hypotheses have not been tested.

M. mexicana is by far the most abundant species of the genus in Central America [

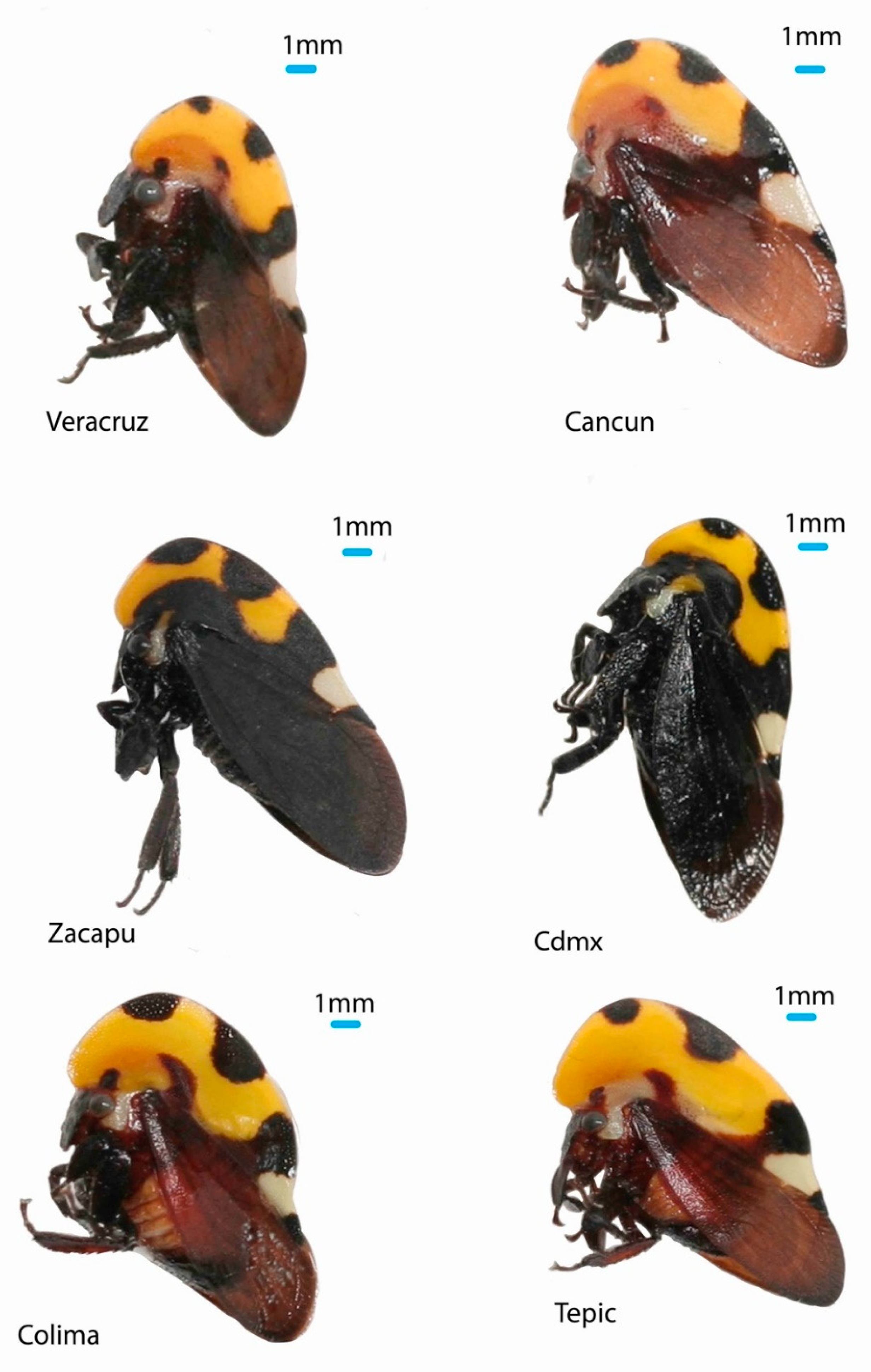

11] and is also very variable in size and color (

Figure 1). For it is an excellent model species to analyze intraspecific variation at the phenotypic and genetic levels. In this sense, we analyzed the helmet shape to characterize the phenotype and used five markers: four nuclear sequences (genes: 28S ribosomal, H2A, H3 and Wg) and one mitochondrial (COI) to estimate the genetic diversity of

M. mexicana.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

In Mexico,

Membracis mexicana is distributed throughout the tropical region along both the Pacific and Gulf coasts, including the Yucatan Peninsula. Collection permits were issued by SEMARNAT, official letters No. SGPA/DGVS/11707/19 and SGPA/DGVS/06171/20. It is important to point out that this species is not in any risk category according to NOM-059 of SEMARNAT. Based on records of insects collected and deposited in the National Insect Collection of the IB, UNAM, 15 points along the two coasts of Mexico and the center were visited. Four sampling seasons were organized in May 2019 (visiting the states of Veracruz, Puebla), December 2019 (states: Veracruz, Campeche, Quintana Roo and Yucatán) December 2021 (states: Michoacán, Guerrero) and May 2021 (states: Michoacán, Jalisco, Nayarit, Guadalajara, Colima). At each collection site, we look for the host plants reported in the literature and reviewed the plants that predominated in the area. The points were carefully chosen to represent the distribution of

M. mexicana in Mexico, (

Table 1). Additionally, sequence samples from the GenBank of

M. mexicana were added to the south of its distribution, in Guatemala and Panama (COI: AY513459.1 and AY513460.1; Wg: AY593701.1 and AY593700.1) and also, other species of Membracis for phylogenetic analysis. Species:

M. luizae (COI: KX924959.1; Wg: KX925187.1; H3 KX925047.1; 28S: KX924867.1; H2A: KX924705.1)

, M. foliata (COI: KF919641.1; Wg: AY593697.1),

M. flava (COI: AY513455.1; Wg: AY593696.1) and

M. trimaculata (COI: AY513457.1;Wg: AY593698.1).

2.2. Insect Sampling

We collected between 20 to 30 adult individuals per population (

Table 1). Each one was put in a tube with absolute alcohol and its respective label, for subsequent DNA extraction. All host plants were recorded. The upper and lower sides of small plants and shrubs were checked, to manually collect the specimens from different leaves or plants with the aim of not taking genetically related individuals. It has been reported that the adults move very short distances, and the juveniles remain feeding on the same leaf until their fifth molt, while the mother takes care of them [

10].

2.3. Geometric Morphometrics

We took pictures of each sampled insect in RAW format with a Canon 600d camera equipped with an EF-S 60mm macro lens. F2.8 (Canon (UK) Ltd., Surry, UK). In each image included a rule of 1 mm as background and a standard color chip (Colorgauge Micro, Image Science Associates LLC, Williamson, NY, USA). The images were processed with Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 24.1.0 software (Adobe Systems Software Ireland Ltd 2023).

Two-dimensional landmarks and the scale factor were recorded using the tpsDig software [

12]. We used nineteen landmarks to capture the shape of the helmet (Table SM1 and Figure SM1 in the Supplementary Material). The landmark coordinates of all specimens were aligned using a Procrustes superimposition, and shape information was extracted from landmark data. This procedure eliminates the variation of landmark configurations due to size differences, position, and orientation. To compute the centroid size, we used the tpsRelw software [

13] and its size was compared between populations with an ANOVA analysis. The measure of helmet shape differences between 2 forms, the Procrustes distance, is the square root of the sum of squared distances between landmarks after Procrustes superimposition [

14], we estimate this using MorphoJ [

15]. We conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) to explore shape data with any restriction in sample size or clustering variable, PCA produces a new set of variables (the principal components, PCs) that are not correlated [

15,

16]. To compare the helmet shape between populations or host plants we implemented a canonical variate analysis, a widely used method for analyzing group structure in multivariate data, this was performed with MorphoJ [

15]. To visualize shape differences between the mean landmark configuration and configuration shifted up or down along the respective PC axis of the PCA and CV axis of the CVA we choose the lollipop diagrams using MorphoJ and edited the plots in Adobe Illustrator (2023).

2.4. DNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Processing

The DNA extraction of the sampled insects was made with the Qiagen® DNeasy kit for blood and tissue. Except for the pronotum, the complete body of the insect was used for extraction, it was placed in a 1.5ml tube for processing, we used liquid nitrogen to homogenize the sample using a micropistile, then the protocol of the kit was followed. The amount of DNA extracted was quantified with the NanoDrop ND1000 (Thermo-Scientific). For the amplification of the five gene regions (28S, H2A, H3, Wg and COI) we used the oligos and conditions mentioned in Evangelista et al. [

17]. The chromatograms were analyzed, and the sequences were edited with the Chromas v2.6.6 program from Technelysium DNA Sequencing Software. For each sample, the quality of the sequences was checked and the ends where the bases had a quality of 30 or less were eliminated. It was visually confirmed that the peaks of the chromatogram corresponded with the read base.

The identity of the obtained sequences was verified via BLAST on the National Center for Biotechnology Information portal (

http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) using the blastn optimization algorithm, to identify and remove contaminated sequences. For each database of the sequence of each gene, the alignment was made with Clustal Omega [

18]. The evolution model of each sequence was estimated with the jmodelTest program [

19].

2.5. Genetic and Phylogeographic Analyzes

The measures of polymorphism and genetic diversity (the number of haplotypes, the values of haplotypic diversity, nucleotide diversity and theta value) and the neutrality test of each gene were estimated with the software DnaSP 6 [

20]. To determine the population structure, the intrapopulation differentiation index FCT was estimated considering the geographical distance between each sampling point and without considering it using SAMOVA 2 [

21] the analysis was run for each of the genes considering from K=2 to K= 11 (number of sampled sites). Haplotype networks for each gene were constructed with the median-joining algorithm [

22] in Network. v.2.0 and PopArt [

23].

To infer the genealogical lineages, we estimated the phylogeny per gene by Bayesian inference (BI) with BEAST v. 2 [

24]. To root the phylogeny, we used the COI and Wg gene sequences from GenBank. BEUTi was used to prepare the input, Tracer v. 1.7.1 [

25] to eliminate burn-in and checked out the convergence of chains, TreeAnotator to summarize the obtained trees, and FigTree v. 1.4.4 for its visualization. The running parameters were 10,000,000 generations for each gene, and 1000 of burn-in were removed. We also estimated a single phylogeny using the four nuclear sequences using a concatenated matrix and M. luizae as an outgroup by BI using Mr Bayes, running 10,000,000 generations, until the sampling variance reached 0.01.

For the analysis of demographic reconstruction, we used the mutation rates reported in Allio et al. [

26]. mmit= 0.009 mutations per site per million years for the mitochondrial sequence and mnuc= 0.0044 mutations per site per million years for the data set with the four nuclear sequences. Both run under the Coalescent model a Coalescent Bayesian Skyline analysis in BEAST v. 2 [

24]. The analyses were run for 30,000,000 generations and 3000 of burn-in were removed, for the convergence of chains and the visualization of Skyline Plots we use Tracer v. 1.7.1 [

25].

3. Results

3.1. Insect Sampling

Of a total of 15 sites visited, we found M. mexicana in 11 (

Table 1). Among the observations, it is worth mentioning that during the sampling of December 2020 on the Pacific coast of Mexico, we did not find M. mexicana in any host plant. We observed adults and eggs in 6 plants and only adults in Heimia salicifolia. In total, 309 adults of M. mexicana were sampled on 7 plant species: Terminalia catappa, Ficus carica, Spondias purpurea, Artocarpus altilis, Cassia fistula, Heimia salicifolia and Salix babylonica.

3.2. Geometric Morphometric Analysis

3.2.1. Centroid Size of the Helmet

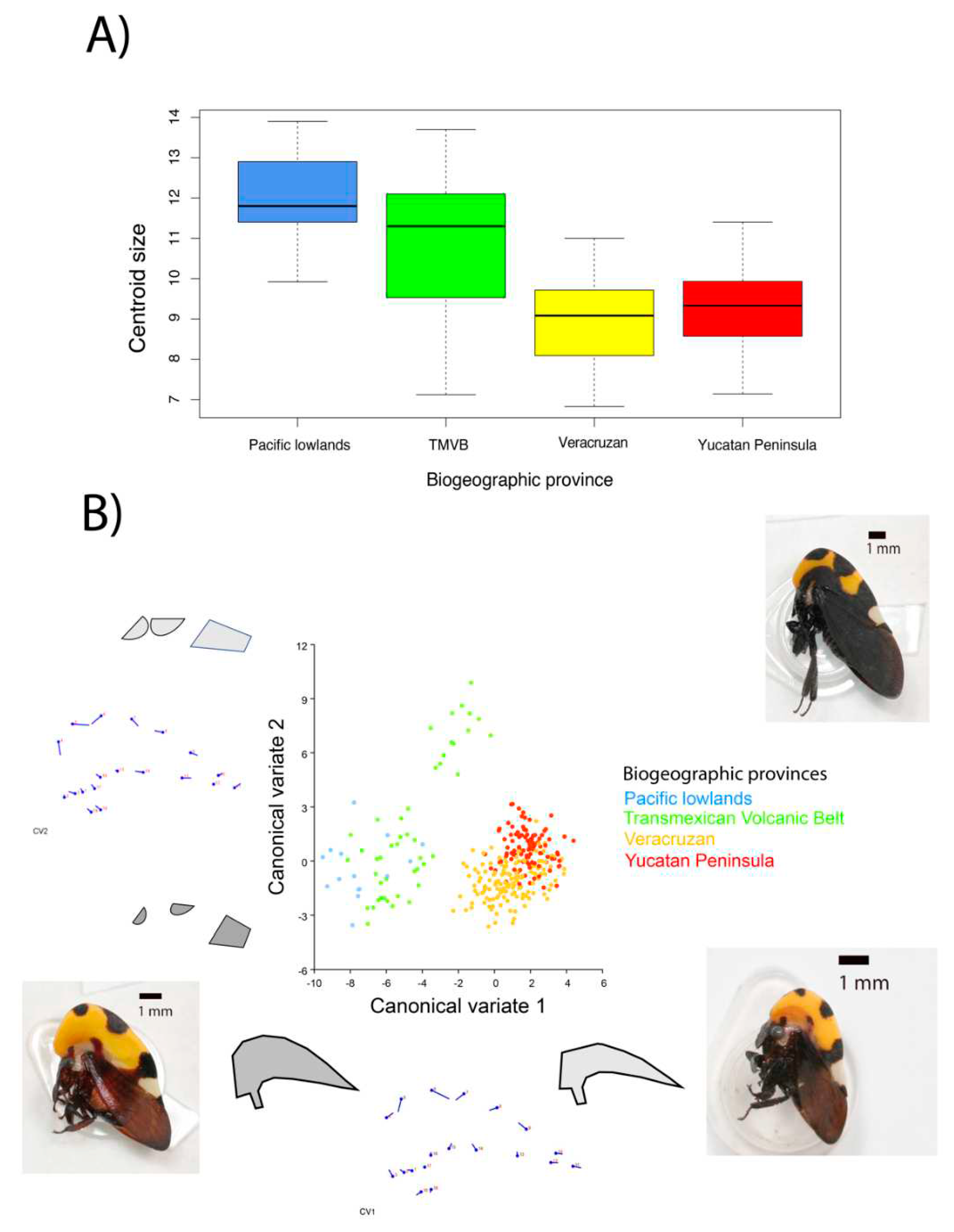

The centroid size by biogeographic province showed different sizes (

Figure 2A) indicating that Pacific lowlands and TMVB provinces have the largest helmet compared to the other provinces. The difference is statistically significant (F = 42.45, p= <2e-16), the distribution of the data indicates that the helmet of these populations are from 9 to 14 units while those of the other populations are from 7 to 11 units.

The centroid size by the host plant (Figure SM2 in the Supplementary Material) shows that the helmets sampled on T. catappa are of all sizes, but the largest helmets were sampled on Spondias purpurea, Artocarpus altilis, Cassia fistula, and Heimia salicifolia, and the smallest on Ficus carica and Salix babylonica (F = 7.894, p= 6.58e-08).

3.2.2. Principal Components of Helmet Shape

The analysis of principal components (Figure SM3 and SM4) shows that the principal axes that describe the shape of the helmet are the width with 24 % (principal component 1) and the length with 20 % (principal component 2). PC 1, the width of the helmet, separates the Pacific lowlands and TMVB (Colima, Puerto Vallarta, San Patricio, Santa Teresa, and Tepic) from the other provinces, except for Zacapu population at TMVB, whose helmet shape remains in the center of the distribution. The length of the helmet (PC2) does not allow us to discern groups, the insects in the populations seem to be distributed homogeneously, with long and short pronotums in all populations. The analysis of canonical variance by the host plant takes away the insects sampled on Sallix bonplandiana from the rest also from Zacapú population (Figure SM5). The canonical variate 1 (CV1) shows that the size of the dorsal spots are largest in their helmet and is what makes this population different from the others. .

3.2.3. Canonical Variance of Helmet Shape

The analysis of canonical variance by biogeographic province indicates three groups (

Figure 2B). In group 1 we have Pacific lowlands and TMVB provinces, in group 2 only TMVB (Zacapú), and in group 3 the Veracruzan and Yucatan peninsula provinces. The canonical variate 1 (CV1) has to do with the width of the helmet, the widest helmet occurs in group 1, the narrowest in group 3, and the intermediate ones in group 2. The canonical variate 2 (CV2) has mainly to do with the size of the dorsal spots, these only differentiate the population of Zacapu (in TMVB) from the rest, indicating larger spots.

Altogether, we found phenotypic variation in three components of the helmet of Membracis mexicana: size, width, and size of the dorsal spots. This variation is not randomly distributed. We found the helmet type 1 (large, wide, and with small dorsal spots) in Tepic, Colima, Puerto Vallarta, San Patricio, and Santa Teresa. The helmet type 2 (small, narrow, and with large dorsal spots) in Zacapu. And the helmet type 3 (small, narrow and with small spots) in Veracruz, Coatzacoalcos, Ciudad del Carmen, Champoton, and Cancun. This variation is distributed as follows in the biogeographical provinces: helmet type 1 in the Pacific Coast (Puerto Vallarta and San Patricio), helmet type 1 and 2 in the TMVB province (Tepic, Colima, Santa Teresa, and Zacapu), helmet 3 in the provinces of the Gulf of Mexico (Veracruz and Coatzacoalcos) and the Yucatan Peninsula (Ciudad del Carmen, Champoton, and Cancun).

3.3. Genetic and Phylogeographic Analyzes

3.3.1. DNA Polymorphism

A total of 844 sequences were obtained: 189 for the 28S gene, 177 for the H3 gene, 190 for the H2A gene, 147 for the Wg gene and 141 for the COI gene (Table SM2 in the Supplementary Material), each haplotypes sequences are uploaded to GenBank (ID numbers are: OR123974-OR124006 (for H2A), OR124007-OR124028 (for H3), OR124029-OR124058 (for Wg), OR120258-OR120285 (for 28S) and OR120103-OR120156 (for COI)). The diversity indices indicate high genetic diversity in all genes. For example, haplotype diversities were 0.797 (28S), 0.625 (H3), 0.425 (H2A), 0.874 (Wg) and 0.881 (COI) while nucleotide diversities were 0.01071 (28S), 0.00342 (H3), 0.00375 (H2A), 0.03121 (Wg) and 0.01807 (COI). Neutrality tests for all genes were statistically significant: The Fu and Li’s F -6.41793 (28S), -3.86732 (H3), -4.04503 (H2A) and -2.85538 (COI), just the Wg gene was positive (2.36933). Tajima D’s were significant and negative for 28S, H3 and H2A (-2.18358, -1.97102 and -2.34419), while positive and significant for Wg gene (2.81039) and negative and non-significant for COI (-1.72698).

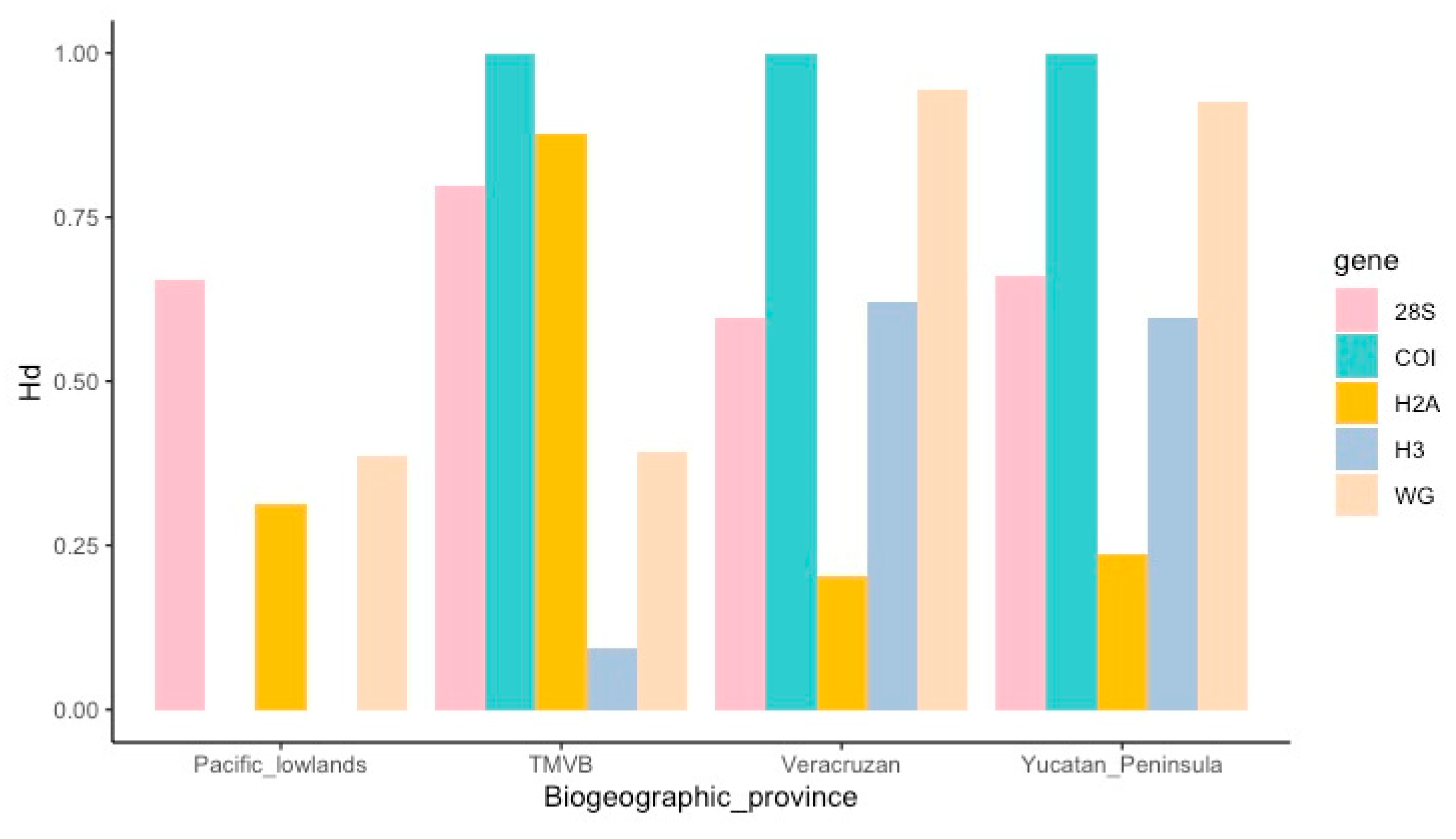

Figure 3 shows the haplotype diversity of each gene by biogeographic provinces.

3.3.2. Haplotype Networks

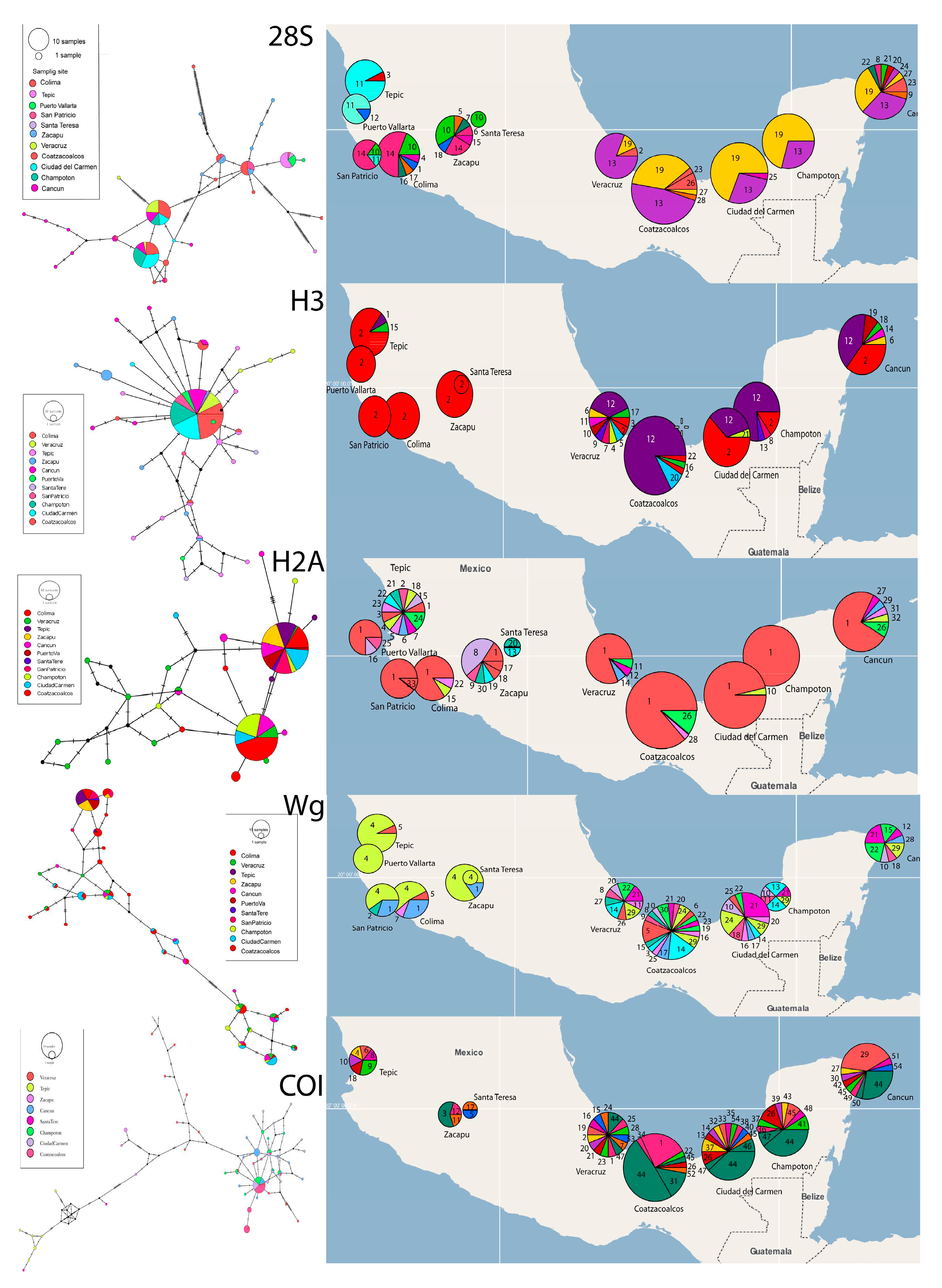

The haplotype networks for all four genes (

Figure 4A; Figures SM6 to SM10) and their geographic distribution (

Figure 4B; Figures SM11 to SM15), show large divergence and clear geographic structure. The numbers of each haplotype and the frequency of haplotypes are shown in the Supplementary Material (Figures SM6-SM15; Table SM3). For all nuclear genes, the most frequent haplotypes are found in all populations. Finally, COI amplification was not successful in samples from Puerto Vallarta, San Patricio y Colima.

3.3.3. Analysis of Population Structure

The pattern of population structure shown by the five genes indicates a genetic break between the western populations (Tepic, Puerto Vallarta, San Patricio, Colima, Santa Teresa and Zacapú) and the southeastern populations (Veracruz, Coatzacoalcos, Ciudad del Carmen, Champotón and Cancún). The geographical distribution of each of the haplotypes reflects this break. In addition, SAMOVA values match this break since FCT reaches higher and more significant values in different clusters depending on the gene but the populations belonging to these two groups were always kept separate: West and Southeast. Each genetic marker gave us a higher FCT value when grouping different populations (

Table 2). For the 28S gene k = 6 with FCT = 0.8108 (P-value = 0.000), H3 k = 9 with FCT = 0.55096 (P-value = 0.00880), H2A gene k = 2 with FCT = 0.67267 (P-value = 0.09677), Wg k = 2 with FCT = 0.58272 (P-value = 0.00098) and COI gene k = 3 with FCT = 0.81407 (P-value = 0.00293).

3.3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

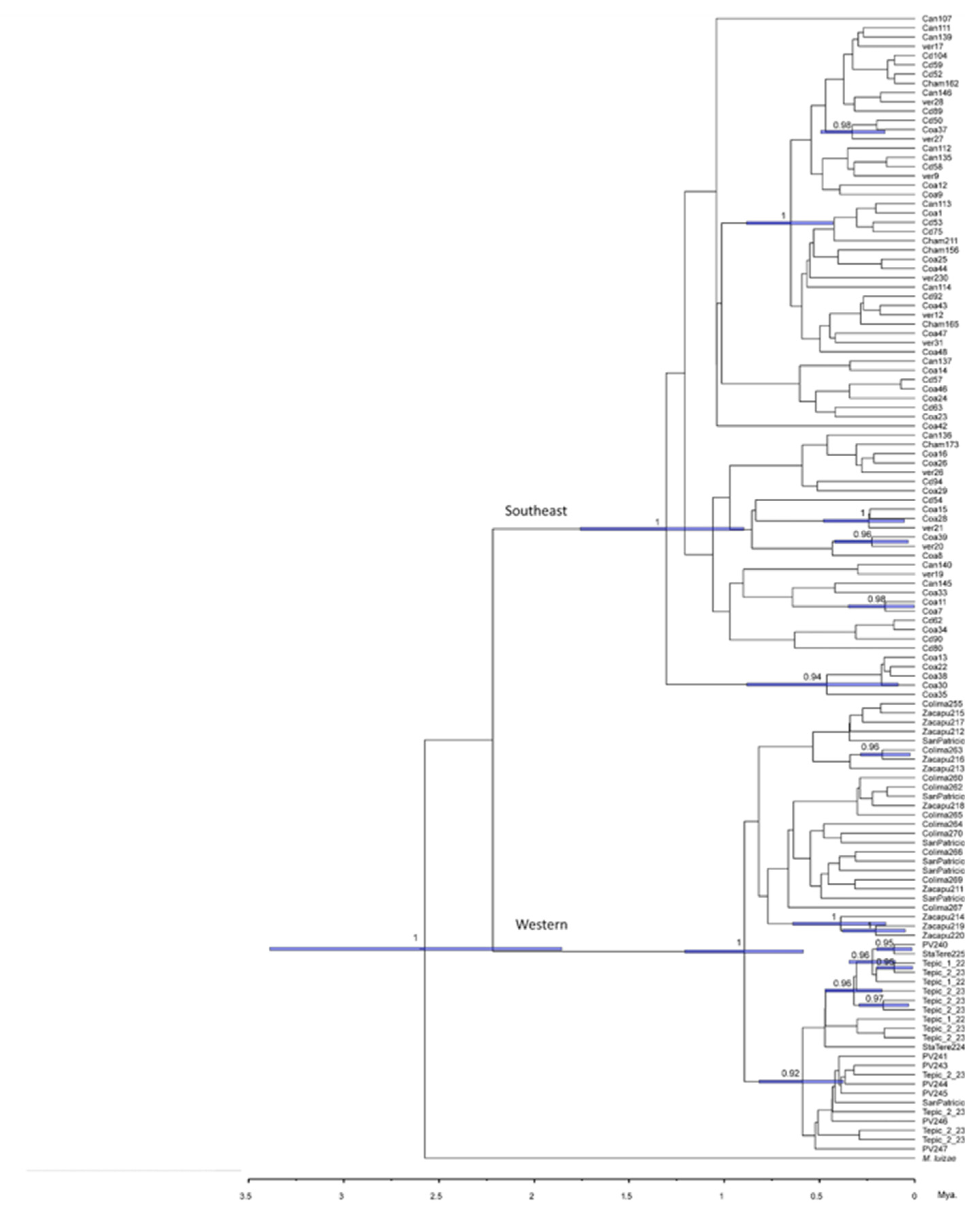

Phylogenetic analyses of the four nuclear genes estimated by Bayesian inference shows a clear division between the haplotypes belonging to these two groups (

Figure 5). The lnL value was -4785.16 with an effective sample size of 2273. It should be noted that the tree was rooted using the species Membracis luizae and the lineages of M. mexicana are divided into the populations of the west (in red) and the populations of the southeast (in blue). The phylogenies estimated for each gene also produce the same pattern (see Supplementary material, Figures SM16-SM20). For COI (Figure SM16) and Wg (Figure SM17) phylogeny, we were able to include more sequences from the GenBank of M. mexicana outside of Mexico (two individuals one from Guatemala and the other from Panama) distribution and one individual for each of the other three species (M. trimaculata, M. fava and M. foliata).

Here is important to notice in

Figure 5 that the west lineage (in red) corresponds to Pacific lowlands and TMVB (including Zacapú population, which helmet is different), and the southeast lineage (in blue) corresponds to Veracruzan and Yucatan Peninsula provinces.

3.3.5. Historical Demography

The historical demographic reconstruction using both data sets, the four nuclear markers and mitochondrial, showed a recent population expansion within less than 1 Ma (Figure SM21 in the Supplementary Material). The Ne of females increases from 7 to 20, while the nuclear genes show that the increase of Ne was from 5 to 80.

4. Discussion

In this study, we explored how the morphological and genetic variation of

M. mexicana is distributed over a wide geographic scale. Richter [

10] has mentioned that the different morphs of Membracis species could be explained by the identity of the host plant. In our work, we did not find much evidence for this, so the role of the host plant in morphological variation is still not clear. One limitation of our study is that most of the insects were found and sampled on

Terminalia catappa and as a consequence our sampling design could not be properly used for testing the Richter hypothesis. Our data suggests that the geographic component partially explains the phenotypic variation in this species. In particular this is apparent by the analysis of the centroid size of the helmet since type 1 is larger than types 2 and 3, and it is found in the TMVB province which would suggest that altitude is playing a role in this trait. This pattern has been seen in other insects such as

Heliconius butterflies where individuals with larger wings are found at higher altitudes. This pattern is found at both intraspecific and interspecific levels [

27].

As we expected we found more genetic diversity in the TMVB province compared with the other provinces. Three genes showed haplotypic diversity values above 0.75 in this province (

Figure 3). Moreover, this pattern of genetic variation is consistent with two lineages in southeastern and western areas (

Figure 5). The western lineage (Pacific Coast and TMVB provinces) corresponds to helmet types 1 and 2, and the southeast lineage (Mexican Gulf and Yucatan Peninsula provinces) corresponds to helmet type 3. The probable cause of this genetic break that distinguishes these two genetic lineages could be the magmatic activity of the Veracruz area during the Pleistocene. This has been described in other insect species like

Canthon cyanellus (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) where the separation between lineages in this area occurred in a time range of 1.63 to 0.91 Ma [

28]. We found for

M. mexicana that the divergence occurred between 2 and 1 Ma.

It is difficult to compare the phylogeographic pattern of

M. mexicana with other species because its distribution covers a wide altitudinal range (from 0 to 2240 MASL) while in published work the studied species are either from highlands or lowlands. For example, in species distributed only in biogeographic provinces covering highlands like

Peromyscus melanophrys group (Rodentia: Muridae) [

29] and

Amazilia cyanocephala (Apodiformes: Trochilidae; [

30]) show genetic barriers explained by lowlands between mountain systems. On the other hand, and in species distributed only in biogeographic provinces covering lowlands show the mountain systems as barriers for genetic flow. Also, the genetic lineages of Neotropical species that have been found predate the closure of the Isthmus of Panama for example,

Boa constrictor imperator (Squamata: Boidae) which shows two lineages one at the Pacific coast and other at the Mexican Gulf that diverged 7 Ma [

31], and

Dasypus novemcinctus with two lineages that diverged prior to the closing of the Panama Isthmus (Cingulata: Dasypodidae; [

32]). Our data indicate that the southeastern and western lineages of

M. mexicana differentiated in Mexico after the closing of the Isthmus of Panama. Possibly the southeastern is more ancestral because in the phylogenetic estimates of Wg and COI we incorporated sequences from the southern distribution of

M. mexicana (Guatemala and Panama) and the haplotypes are clustered with southeastern lineage (Figures SM6 and SM7 ), however, we could only incorporate two samples from Central America which means that more samples from a wider area in the neotropics are needed to test this hypothesis. What we can mention is that it is in one of the first phylogeographic studies of an insect so widely distributed in the biogeographical provinces that it is found in lowlands and highlands.

The reconstruction of historical demography using nuclear and mitochondrial genes shows very similar patterns since both Skyline Plots show a constant size of the population for a long time and a recent population expansion. The only difference between mtDNA and ncDNA is that ncDNA allowed us to visualize the dynamics up to 6 million years ago while mtDNA only up to 3.5 million years ago. The mutation rates for mitochondrial and nuclear sequences made it possible to see that the population expansion of these members occurred recently and is temporally consistent. The expansion appears to have started approx. 150,000 years ago and continues to the present. Perhaps the relatively stable paleoclimate of the Holocene [

33] favored the population expansion over the biogeographic provinces.

In conclusion, the TMVB harbours more intraspecific variation of M. mexicana than other biogeographic. provinces. The relationship between morphology and genetics of M. mexicana shows that geography is playing an important role in population structuring. Finally, we found that the southeaster lineage matches with morphotype 3 and the western lineage with morphotypes 1 and 2

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure SM1: Landmark position. Figure SM2 Centroid size of helmet by host plant. Figure SM3 PCA colored by population.Figure SM4 PCA colored by host plant.Figure SM5 CVA using host plant as classifier variable. Figure SM6 Mitochondrial COI gene haplotype network. Figure SM7 Nuclear WG gene haplotype network. Figure SM8 Nuclear 28S gene haplotype network. Figure SM9 Nuclear H2A gene haplotype network. Figure SM10 Nuclear H3 gene haplotype network. Figure SM11 Geographic distribution and frequency of COI haplotypes. Figure SM12 Geographic distribution and frequency of WG haplotypes. Figure SM13 Geographic distribution and frequency of 28S haplotypes. Figure SM14 Geographic distribution and frequency of H2A haplotypes. Figure SM15 Geographic distribution and frequency of H3 haplotypes. Figure SM16 Bayesian phylogeny using COI. Figure SM17 Bayesian phylogeny using WG. Figure SM18 Bayesian phylogeny using 28S gene segment. Figure SM19 Bayesian phylogeny using H2A gene segment. Figure SM20 Bayesian phylogeny using H3 gene segment. Figure SM21 Skyline plot using mitochondrial (A) and nuclear markers (B). Table SM1 Landmark definition. Table SM2 Variation of genetic markers. Table SM3 Number and frequency of haplotypes.

Author Contributions

MD and DP participated in conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—review and editing the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research was funded by PAPIIT-UNAM, number IA209420 .

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GENBANK (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/).The ID numbers are: OR123974-OR124006 for H2A partial gene sequence, OR124007-OR124028 for H3 partial gene sequence, OR124029-OR124058 for Wg partial gene sequence, OR120258-OR120285 for 28S partial gene sequence and OR120103-OR120156 for COI partial gene sequence.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferrari, L. (2000). Avances en el conocimiento de la Faja Volcánica Transmexicana durante la última década. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana. [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, A. , Lessios, H. A., Coates, A. G., Eytan, R. I., Restrepo-Moreno, S. A., Cione, A. L.,... & Stallard, R. F. Formation of the Isthmus of Panama. Science advances, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, M., Lozano-García, S., Vázquez-Selem, L., & Ortega, B. Evidencias de cambio climático y ambiental en registros glaciales y en cuencas lacustres del centro de México durante el último máximo glacial. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana 2010, 62, 359-377 SIN_DOI <http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-33222010000300005&lng=es&nrm=iso>. ISSN 1405-3322. [CrossRef]

- Mastretta-Yanes, A. , Moreno-Letelier, A., Pinero, D., Jorgensen, T. H., & Emerson, B. C. Biodiversity in the Mexican highlands and the interaction of geology, geography and climate within the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt. Journal of Biogeography, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrone, J. J. Fundamental biogeographic patterns across the Mexican Transition Zone: an evolutionary approach. Ecography 2010, 33(2), 355-361. 2. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Ortega, J. S., Salinas-Rodríguez, M. M., Martínez, J. F., Molina-Freaner, F., Pérez-Farrera, M. A., Vovides, A. P., ... & Kajita, T. The phylogeography of the cycad genus Dioon (Zamiaceae) clarifies its Cenozoic expansion and diversification in the Mexican transition zone. Annals of Botany 2018, 121(3), 535-548. [CrossRef]

- Morrone, J. J., Espinosa Organista, D., & Llorente Bousquets, J. (2002). Mexican biogeographic provinces: preliminary scheme, general characterizations, and synonymie. Acta zoológica mexicana, (85), 83-108 SIN DOI versión On-line ISSN 2448-8445versión impresa ISSN 0065-1737.

- Halffter, G. Biogeography of the montane entomofauna of Mexico and Central America. Annual review of entomology 1987, 32(1), 95-114. 1. [CrossRef]

- Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., Da Fonseca, G. A., & Kent, J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, 403(6772), 853. [CrossRef]

- Richter, L. (2017). Membracidae Colombianae. Revision de las especies Colombianas del genero Membracis. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, 222-246. SIN_DOI. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, W. W. 1894-1909. Biologia Centrali-Americana. Insecta Rhynchota. Hemiptera-Homoptera Vol 11 part I. 1-339. SIN_DOI. [CrossRef]

- Rohlf F (2007) tpsRelw. Available from http://life.bio.sunysb.

- Rohlf F (2007) tpsDig. Available from http://life.bio.sunysb.

- Bookstein F. L. (1997) Morphometric Tools for Landmark Data. Cambridge, UK. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521585988.

- Klingenberg, C. P. MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Molecular ecology resources 2011, 11(2), 353-357. 2. [CrossRef]

- Klingenberg, C. P., & McIntyre, G. S. Geometric morphometrics of developmental instability: analyzing patterns of fluctuating asymmetry with Procrustes methods. Evolution 1998, 52(5), 1363-1375. [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, O., Sakakibara, A. M., Cryan, J. R., & Urban, J. M. A phylogeny of the treehopper subfamily Heteronotinae reveals convergent pronotal traits (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha: Membracidae). Systematic Entomology 2017, 42(2), 410-428. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. D., Gibson, T. J., & Higgins, D. G. (2003). Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Current protocols in bioinformatics, (1), 2-3. [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R., & Posada, D. (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature methods, 9(8), 772. [CrossRef]

- Librado, P., & Rozas, J. (2009). DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics, 25(11), 1451-1452. [CrossRef]

- Dupanloup, I., Schneider, S., & Excoffier, L. (2002). A simulated annealing approach to define the genetic structure of populations. Molecular ecology, 11(12), 2571-2581. 12. [CrossRef]

- Bandelt, H. J., Forster, P., & Röhl, A. (1999). Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Molecular biology and evolution, 16(1), 37-48. [CrossRef]

- Leigh, JW. & Bryant D (2015). PopART: Full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6(9):1110–1116. [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, R., Heled, J., Kühnert, D., Vaughan, T., Wu, C. H., Xie, D., ... & Drummond, A. J. (2014). BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS computational biology, 10(4), e1003537. [CrossRef]

- Rambaut A, Drummond AJ, Xie D, Baele G and Suchard MA (2018) Posterior summarisation in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Systematic Biology. [CrossRef]

- Allio, R., Donega, S., Galtier, N., & Nabholz, B. (2017). Large variation in the ratio of mitochondrial to nuclear mutation rate across animals: implications for genetic diversity and the use of mitochondrial DNA as a molecular marker. Molecular biology and evolution, 34(11), 2762-2772. [CrossRef]

- Montejo-Kovacevich, G., Smith, J. E., Meier, J. I., Bacquet, C. N., Whiltshire-Romero, E., Nadeau, N. J., & Jiggins, C. D. Altitude and life-history shape the evolution of Heliconius wings. Evolution 2019, 73(12), 2436-2450. [CrossRef]

- Nolasco-Soto, J., González-Astorga, J., de Los Monteros, A. E., Galante-Patiño, E., & Favila, M. E. (2017). Phylogeographic structure of Canthon cyanellus (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae), a Neotropical dung beetle in the Mexican Transition Zone: Insights on its origin and the impacts of Pleistocene climatic fluctuations on population dynamics. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 109, 180-190. [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Rico, S. , León-Paniagua, L., Vázquez-Domínguez, E., & Navarro-Sigüenza, A. G. (2014). Evolutionary diversification and speciation in rodents of the Mexican lowlands: the Peromyscus melanophrys species group. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gómez, F., Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, C., & Ornelas, J. F. Genetic, phenotypic and ecological divergence with gene flow at the Isthmus of Tehuantepec: the case of the azure-crowned hummingbird (Amazilia cyanocephala). Journal of Biogeography 2013, 40(7), 1360-1373. [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Atilano, M., Burbrink, F., & Vázquez-Domínguez, E. (2014). Phylogeographical structure within Boa constrictor imperator across the lowlands and mountains of Central America and Mexico. Journal of Biogeography, 41(12), 2371-2384. 12. [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, M. C., Piñero, D., Eguiarte, L. E., Gasca, J., & Medellín, R. A. (2012). Genetic structure and diversity of the nine-banded armadillo in Mexico. Journal of Mammalogy, 93(2), 547-559. [CrossRef]

- Barry, R. G., & Hall-McKim, E. A. (2018). Polar environments and global change. Cambridge University Press. SIN_DOI.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).