Submitted:

21 July 2023

Posted:

24 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

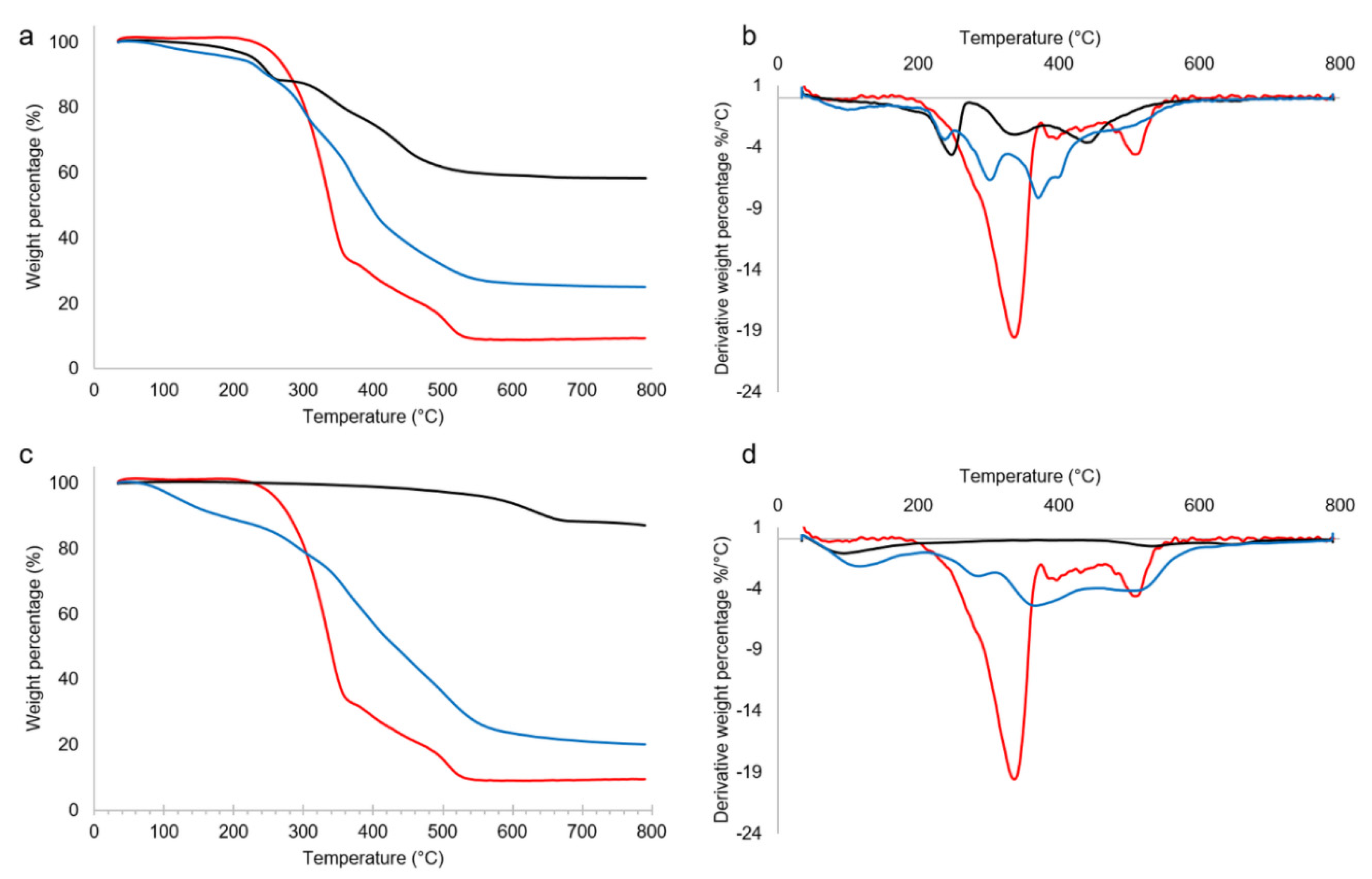

2.1. Thermal analysis

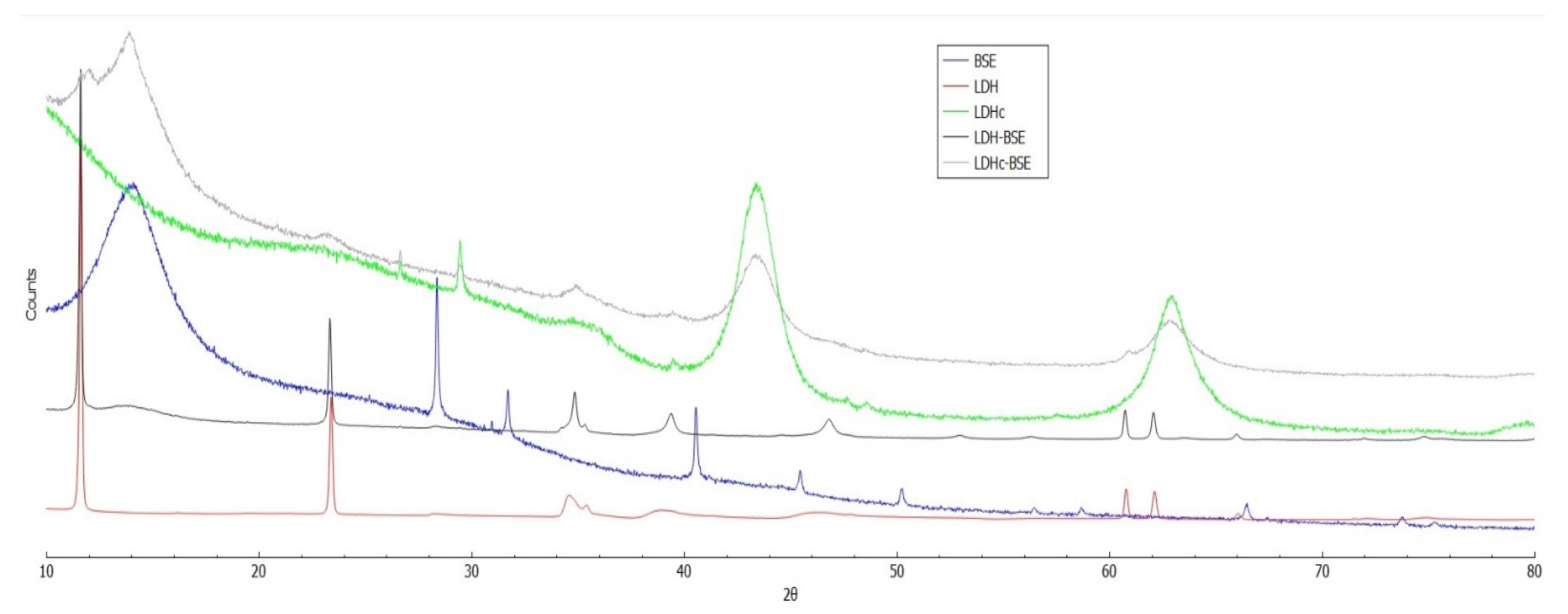

2.2. Powder X-Ray Diffraction analysis

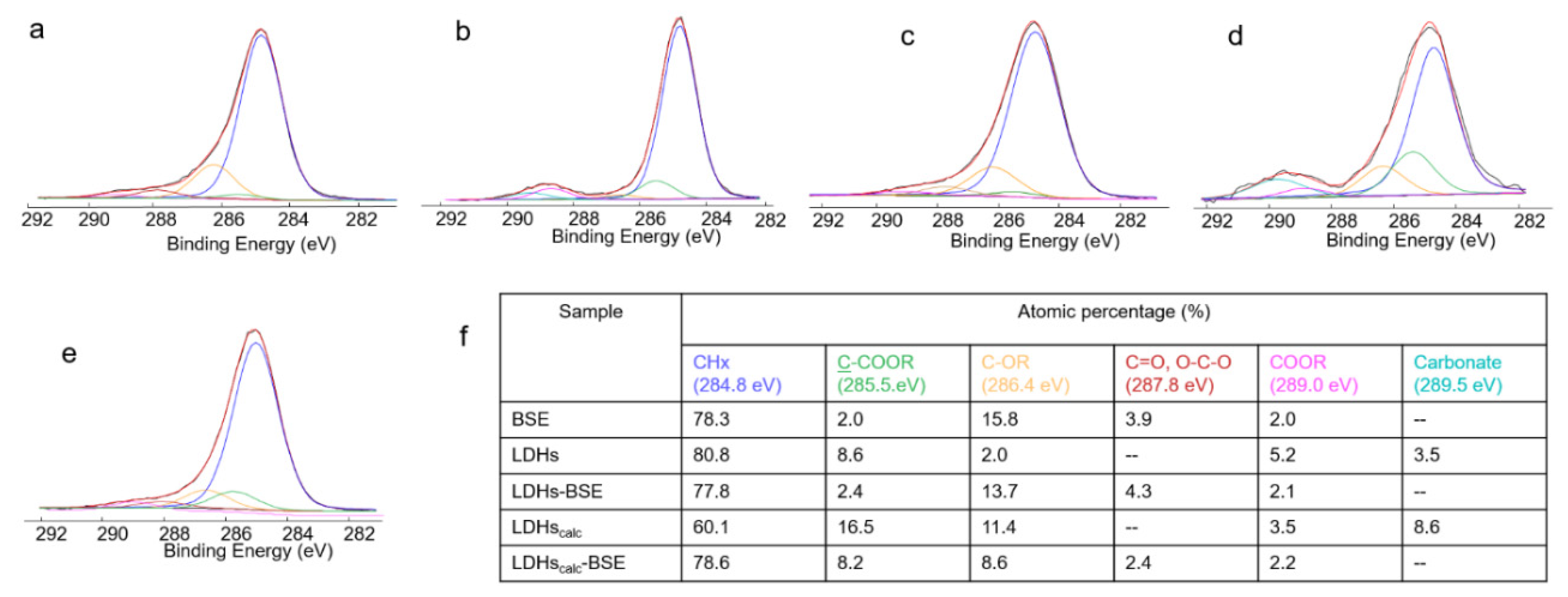

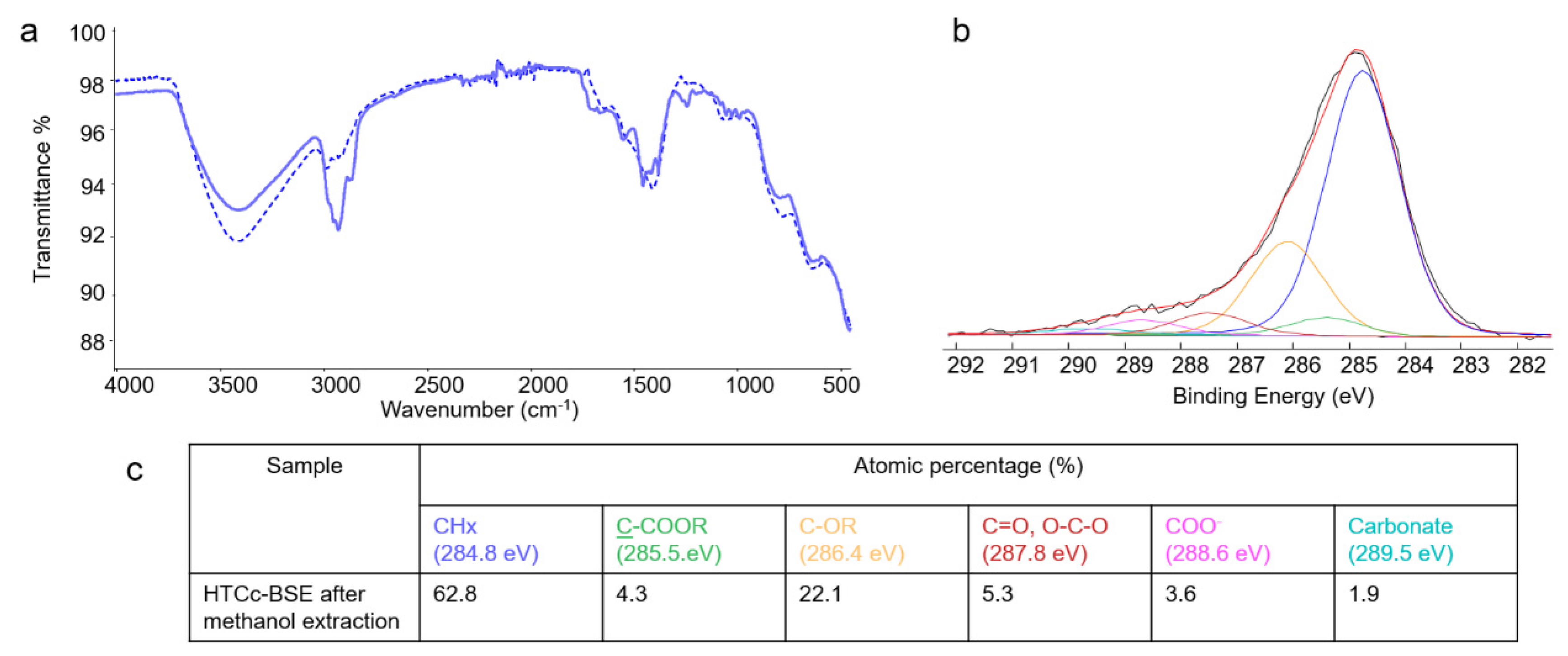

2.3. Bulk and surface investigations

| Sample | Atomic % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1s | O1s | Ca2p | Na1s | Al2p | Mg1s | Si2p | |

| BSE | 86.1 | 12.6 | 0.9 | 0.4 | -- | -- | -- |

| LDH | 47.4 | 42.3 | -- | -- | 5.2 | 3.7 | 1.5 |

| LDH-BSE | 76.4 | 19,1 | -- | -- | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.1 |

| LDHc | 16.8 | 55.2 | -- | -- | 11.2 | 16.8 | 0.7 |

| LDHc-BSE | 79.1 | 16.7 | -- | -- | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

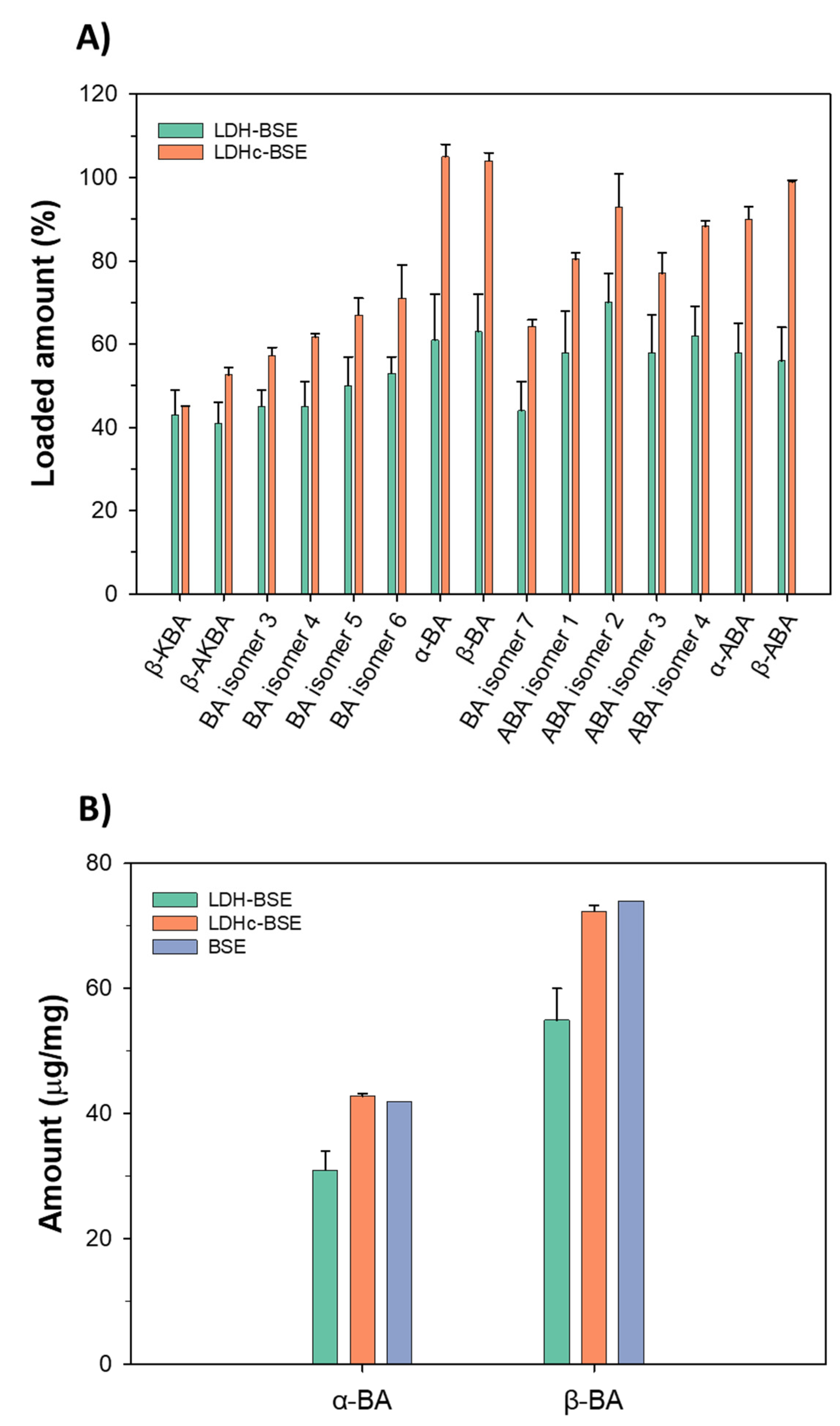

2.4. Targeted RPLC-ESI(-)-FTMS characterization of boswellic acids in BSE and LDH(c)-BSE hybrid composites

2.5. Antimicrobial activity of BSE-based composites

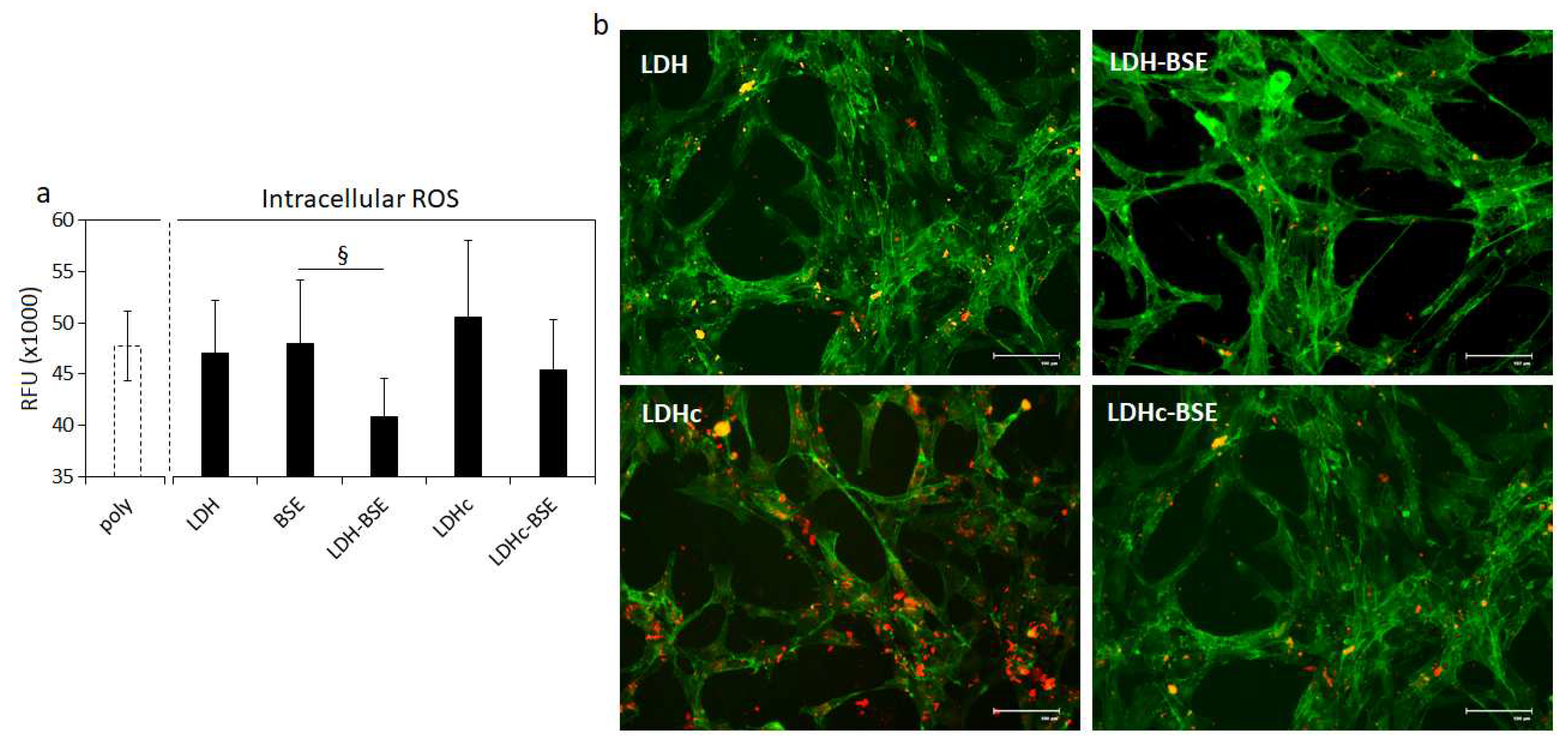

2.6. Antinflammatory activity of BSE-based composites

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of the hybrid composites based on LDH and calcined LDH

3.3. Physical-chemical characterization of the hybrid composites

3.3.1. Thermo-Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

3.3.2. Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) measurements

3.3.3. Bulk and Surface Chemical Characterization

3.3.4. RPLC-ESI-FTMS instrumentation and operating conditions

3.3.5. Extraction of BSE from LDH-BSE and LDHc-BSE composites

3.3.6. Quantification of boswellic acids in LDH-BSE and LDHc-BSE composites

3.4. Antibacterial evaluation

3.5. Anti-inflammatory efficacy

3.6. Statistical data analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Ammon, H. Boswellic Acids in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 1100–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iram, F.; Khan, S.A.; Husain, A. Phytochemistry and Potential Therapeutic Actions of Boswellic Acids: A Mini-Review. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2017, 7, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroš, P.; Timkina, E.; Michailidu, J.; Maršík, D.; Kulišová, M.; Kolouchová, I.; Demnerová, K. Boswellic Acids as Effective Antibacterial Antibiofilm Agents. Molecules 2022, 27, 3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Verma, S.K.; Singh, S.; Trivedi, L.; Rout, P.K.; Vasudev, P.G.; Luqman, S.; Darokar, M.P.; Bhakuni, R.S.; Misra, L. Anti-Proliferative and Antibacterial Activity of Oleo-Gum-Resin of Boswellia Serrata Extract and Its Isolate 3-Hydroxy-11-Keto-β-Boswellic Acid. J. Herb. Med. 2022, 32, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Gupta, N.K.; Dixit, V.K. Complexation with Phosphatidyl Choline as a Strategy for Absorption Enhancement of Boswellic Acid. Drug Deliv. 2010, 17, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hüsch, J.; Bohnet, J.; Fricker, G.; Skarke, C.; Artaria, C.; Appendino, G.; Schubert-Zsilavecz, M.; Abdel-Tawab, M. Enhanced Absorption of Boswellic Acids by a Lecithin Delivery Form (Phytosome®) of Boswellia Extract. Fitoterapia 2013, 84, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hüsch, J.; Gerbeth, K.; Fricker, G.; Setzer, C.; Zirkel, J.; Rebmann, H.; Schubert-Zsilavecz, M.; Abdel-Tawab, M. Effect of Phospholipid-Based Formulations of Boswellia Serrata Extract on the Solubility, Permeability, and Absorption of the Individual Boswellic Acid Constituents Present. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambe, A.; Pandita, N.; Kharkar, P.; Sahu, N. Encapsulation of Boswellic Acid with β- and Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin: Synthesis, Characterization, in Vitro Drug Release and Molecular Modelling Studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1154, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.; Dureja, H.; Garg, M. Development and Optimization of Boswellic Acid-Loaded Proniosomal Gel. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 3072–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, N.; Mehta, M.; Chellappan, D.K.; Gupta, G.; Hansbro, N.G.; Tambuwala, M.M.; AA Aljabali, A.; Paudel, K.R.; Liu, G.; Satija, S.; et al. Antiproliferative Effects of Boswellic Acid-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles on Human Lung Cancer Cell Line A549. Future Med. Chem. 2020, 12, 2019–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AGUZZI, C.; CEREZO, P.; VISERAS, C.; CARAMELLA, C. Use of Clays as Drug Delivery Systems: Possibilities and Limitations. Appl. Clay Sci. 2007, 36, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.A. de S.; Figueiras, A.; Veiga, F.; de Freitas, R.M.; Nunes, L.C.C.; da Silva Filho, E.C.; da Silva Leite, C.M. The Systems Containing Clays and Clay Minerals from Modified Drug Release: A Review. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2013, 103, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Cheng, Z.; Tan, S.; Zhu, Q. Clay Nanoparticles as Pharmaceutical Carriers in Drug Delivery Systems. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2021, 18, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, U.; Ambrogi, V.; Nocchetti, M.; Perioli, L. Hydrotalcite-like Compounds: Versatile Layered Hosts of Molecular Anions with Biological Activity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 107, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankala, R.K. Nanoarchitectured Two-Dimensional Layered Double Hydroxides-Based Nanocomposites for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 186, 114270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-J.; Oh, J.-M.; Choy, J.-H. Toxicological Effects of Inorganic Nanoparticles on Human Lung Cancer A549 Cells. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009, 103, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraketi, M.; Hosni, K.; Srasra, E. Intercalation Behavior of Salicylic Acid into Calcined Cu-Al-Layered Double Hydroxides for a Controlled Release Formulation. Surf. Eng. Appl. Electrochem. 2017, 53, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrogi, V.; Fardella, G.; Grandolini, G.; Nocchetti, M.; Perioli, L. Effect of Hydrotalcite-like Compounds on the Aqueous Solubility of Some Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 92, 1407–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Arco, M.; Fernández, A.; Martín, C.; Sayalero, M.L.; Rives, V. Solubility and Release of Fenamates Intercalated in Layered Double Hydroxides. Clay Miner. 2008, 43, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Zhang, H.; Dou, L. Layered Double Hydroxide-Based Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2014, 6, 298–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.; Zucha, W.J.; Lothenbach, B.; Mäder, U. Stability of Hydrotalcite (Mg-Al Layered Double Hydroxide) in Presence of Different Anions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 152, 106674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimirova, T.; Piperov, N.; Petrova, N.; Kirov, G. Thermal Evolution of Mg-Al-CO 3 Hydrotalcites. Clay Miner. 2004, 39, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allmann, R.J.; Neues, H.P. Die Struktur Des Hydrotalkits. Jahrb. für Mineral. Monatshefte 1969, 544–551. [Google Scholar]

- Del Arco, M.; Cebadera, E.; Gutiérrez, S.; Martín, C.; Montero, M.J.; Rives, V.; Rocha, J.; Sevilla, M.A. Mg,Al Layered Double Hydroxides with Intercalated Indomethacin: Synthesis, Characterization, and Pharmacological Study. J. Pharm. Sci. 2004, 93, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, J.; del Arco, M.; Rives, V.; Ulibarri, M.A. Reconstruction of Layered Double Hydroxides from Calcined Precursors: A Powder XRD and 27Al MAS NMR Study. J. Mater. Chem. 1999, 9, 2499–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Román, M.S.; Holgado, M.J.; Salinas, B.; Rives, V. Characterisation of Diclofenac, Ketoprofen or Chloramphenicol Succinate Encapsulated in Layered Double Hydroxides with the Hydrotalcite-Type Structure. Appl. Clay Sci. 2012, 55, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Cui, L.; Ai, S.; Fan, H.; Zhu, L. Electrochemical Determination of Bisphenol A at Mg–Al–CO3 Layered Double Hydroxide Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mališová, M.; Horňáček, M.; Mikulec, J.; Hudec, P.; Jorík, V. FTIR Study of Hydrotalcite. Acta Chim. Slovaca 2018, 11, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giglio, E.; Ditaranto, N.; Sabbatini, L. Polymer Surface Chemistry: Characterization by XPS. In Polymer Surface Characterization; De Gruyter, 2022; pp. 45–88.

- Zhang, C.; Sun, L.; Tian, R.; Jin, H.; Ma, S.; Gu, B. Combination of Quantitative Analysis and Chemometric Analysis for the Quality Evaluation of Three Different Frankincenses by Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography and Quadrupole Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2015, 38, 3324–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.A.; Qazi, G.N.; Taneja, S.C. Boswellic Acids: A Group of Medicinally Important Compounds. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Börner, F.; Werner, M.; Ertelt, J.; Meins, J.; Abdel-Tawab, M.; Werz, O. Analysis of Boswellic Acid Contents and Related Pharmacological Activities of Frankincense-Based Remedies That Modulate Inflammation. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmiech, M.; Lang, S.J.; Werner, K.; Rashan, L.J.; Syrovets, T.; Simmet, T. Comparative Analysis of Pentacyclic Triterpenic Acid Compositions in Oleogum Resins of Different Boswellia Species and Their In Vitro Cytotoxicity against Treatment-Resistant Human Breast Cancer Cells. Molecules 2019, 24, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ning, Z.; Lu, C.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y. Triterpenoid Resinous Metabolites from the Genus Boswellia: Pharmacological Activities and Potential Species-Identifying Properties. Chem. Cent. J. 2013, 7, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmiech, M.; Ulrich, J.; Lang, S.J.; Büchele, B.; Paetz, C.; St-Gelais, A.; Syrovets, T.; Simmet, T. 11-Keto-α-Boswellic Acid, a Novel Triterpenoid from Boswellia Spp. with Chemotaxonomic Potential and Antitumor Activity against Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asteggiano, A.; Curatolo, L.; Schiavo, V.; Occhipinti, A.; Medana, C. Development, Validation, and Application of a Simple and Rugged HPLC Method for Boswellic Acids for a Comparative Study of Their Abundance in Different Species of Boswellia Gum Resins. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Biharee, A.; Kumar, A.; Jaitak, V. Antimicrobial Terpenoids as a Potential Substitute in Overcoming Antimicrobial Resistance. Curr. Drug Targets 2020, 21, 1476–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourmouziadi Laleni, N.; Gomes, P.D.C.; Gkatzionis, K.; Spyropoulos, F. Propolis Particles Incorporated in Aqueous Formulations with Enhanced Antibacterial Performance. Food Hydrocoll. Heal. 2021, 1, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, D.; Chen, G.; Cheng, J.; Wen, J.; Pei, N.; Zeng, H.; Li, Y. Boswellic Acid Captivated Hydroxyapatite Carboxymethyl Cellulose Composites for the Enhancement of Chondrocytes in Cartilage Repair. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 5605–5613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasagoudr, S.S.; Hegde, V.G.; Chougale, R.B.; Masti, S.P.; Dixit, S. Influence of Boswellic Acid on Multifunctional Properties of Chitosan/Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) Films for Active Food Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeckel, D.; Werz, O. Boswellic Acids: Biological Actions and Molecular Targets. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006, 13, 3359–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharti, A.C.; Donato, N.; Singh, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin (Diferuloylmethane) down-Regulates the Constitutive Activation of Nuclear Factor–ΚB and IκBα Kinase in Human Multiple Myeloma Cells, Leading to Suppression of Proliferation and Induction of Apoptosis. Blood 2003, 101, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamna, F.; Yamaguchi, S.; Cochis, A.; Ferraris, S.; Kumar, A.; Rimondini, L.; Spriano, S. Conferring Antioxidant Activity to an Antibacterial and Bioactive Titanium Surface through the Grafting of a Natural Extract. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonifacio, M.A.; Cochis, A.; Cometa, S.; Gentile, P.; Scalzone, A.; Scalia, A.C.; Rimondini, L.; De Giglio, E. From the Sea to the Bee: Gellan Gum-Honey-Diatom Composite to Deliver Resveratrol for Cartilage Regeneration under Oxidative Stress Conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 245, 116410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfieri, M.L.; Riccucci, G.; Ferraris, S.; Cochis, A.; Scalia, A.C.; Rimondini, L.; Panzella, L.; Spriano, S.; Napolitano, A. Deposition of Antioxidant and Cytocompatible Caffeic Acid-Based Thin Films onto Ti6Al4V Alloys through Hexamethylenediamine-Mediated Crosslinking. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 29618–29635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Börner, F.; Pace, S.; Jordan, P.M.; Gerstmeier, J.; Gomez, M.; Rossi, A.; Gilbert, N.C.; Newcomer, M.E.; Werz, O. Allosteric Activation of 15-Lipoxygenase-1 by Boswellic Acid Induces the Lipid Mediator Class Switch to Promote Resolution of Inflammation. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2205604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddhu, N.S.S.; Guru, A.; Satish Kumar, R.C.; Almutairi, B.O.; Almutairi, M.H.; Juliet, A.; Vijayakumar, T.M.; Arockiaraj, J. Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Molecules from Boswellia Serrate Suppresses Lipopolysaccharides Induced Inflammation Demonstrated in an in-Vivo Zebrafish Larval Model. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 7425–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, S. Anion-Exchange Properties of Hydrotalcite-Like Compounds. Clays Clay Miner. 1983, 31, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.M.; Milestone, N.B.; Newman, R.H. The Use of Hydrotalcite as an Anion Absorbent. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1995, 34, 1196–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochis, A.; Azzimonti, B.; Della Valle, C.; De Giglio, E.; Bloise, N.; Visai, L.; Cometa, S.; Rimondini, L.; Chiesa, R. The Effect of Silver or Gallium Doped Titanium against the Multidrug Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii. Biomaterials 2016, 80, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, S.; Cochis, A.; Cazzola, M.; Tortello, M.; Scalia, A.; Spriano, S.; Rimondini, L. Cytocompatible and Anti-Bacterial Adhesion Nanotextured Titanium Oxide Layer on Titanium Surfaces for Dental and Orthopedic Implants. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| E. coli | P. aeruginosa | S. aureus | S. epidermidis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSE | 124 (± 5) | 15 (± 3) | 18 (± 3) | 15 (± 10) |

| LDH | 150 (± 1) | 15 (± 4) | 20 (± 1) | 18 (± 3) |

| LDH-BSE | 46 (± 2)§ | 12 (± 3) | 12 (± 3)§ | 11 (± 1) |

| LDHc | 120 (± 1) | 16 (± 8) | 17 (± 6) | 29 (± 3) |

| LDHc-BSE | 68 (± 2)§ | 12 (± 1) | 15 (± 1) | 20 (± 3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).