Submitted:

20 July 2023

Posted:

21 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

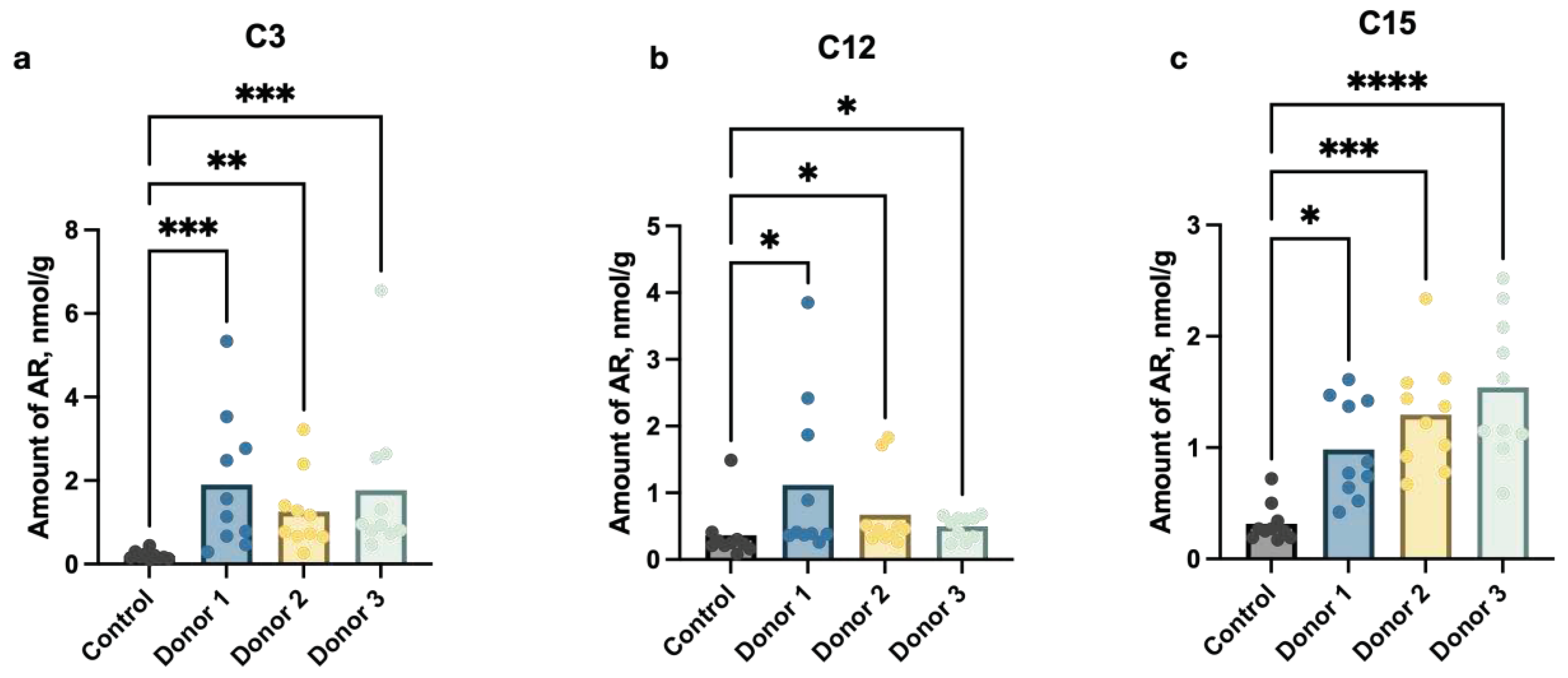

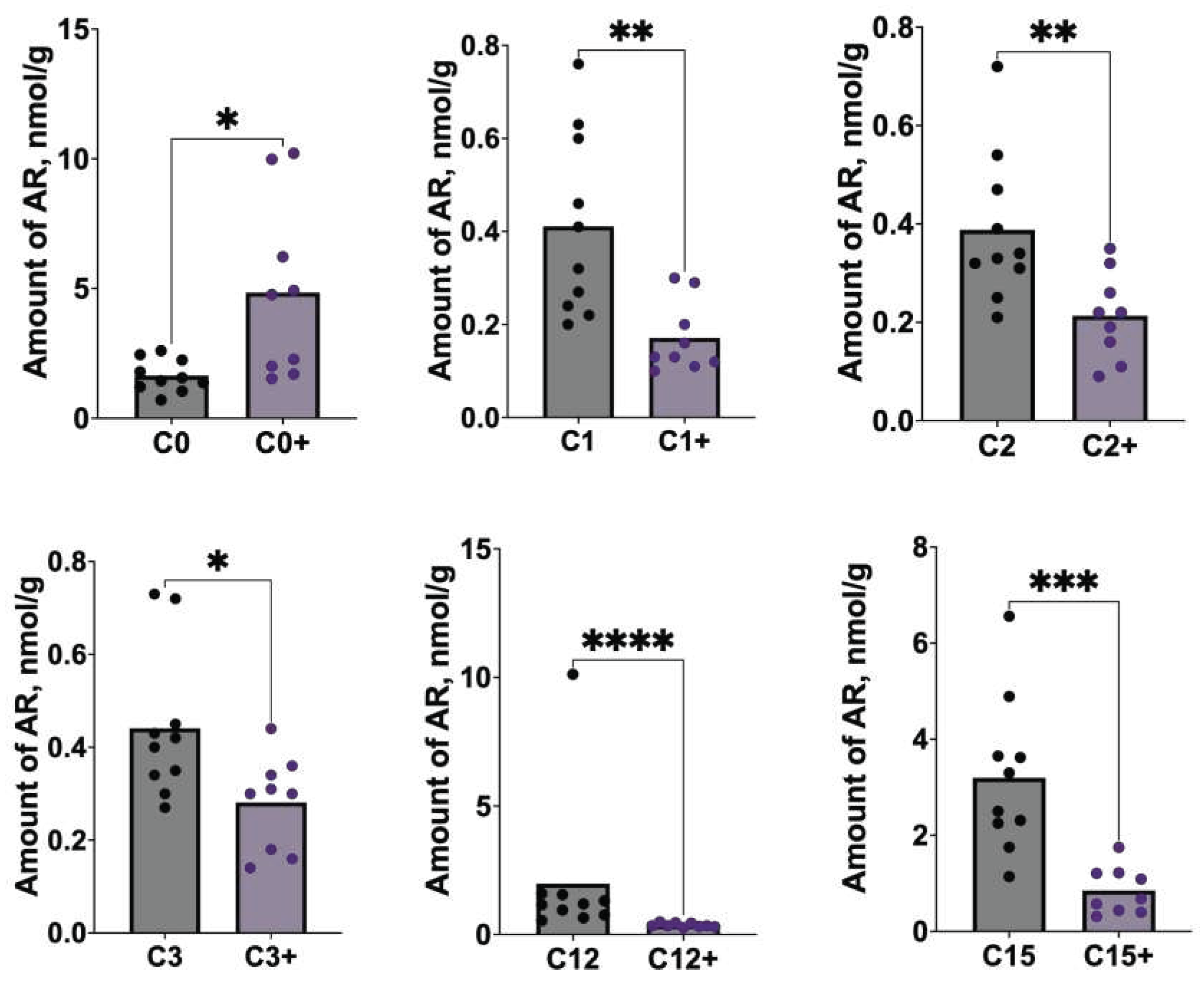

2.1. Estimation of AR content in germ-free mouse faeces after FMT

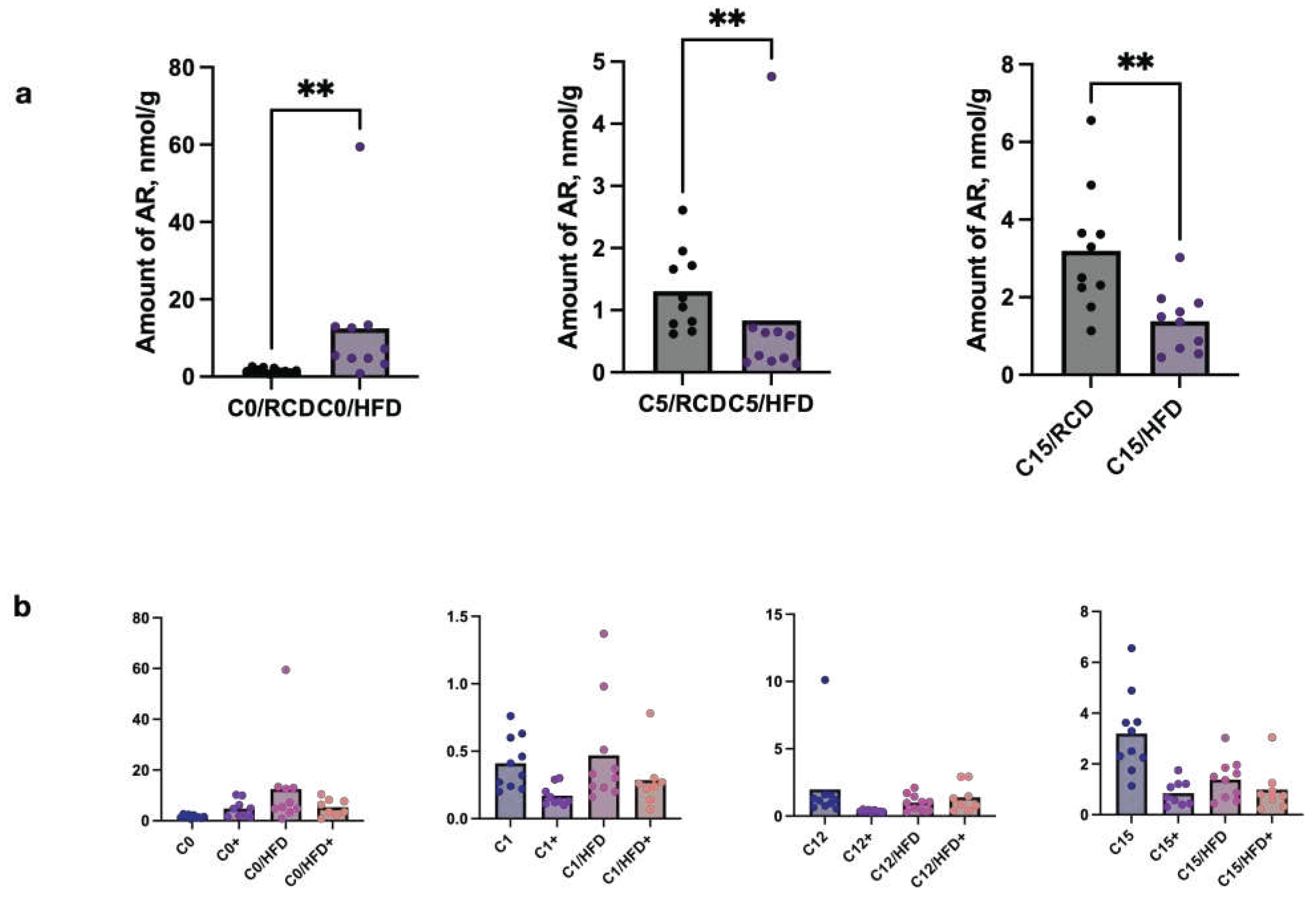

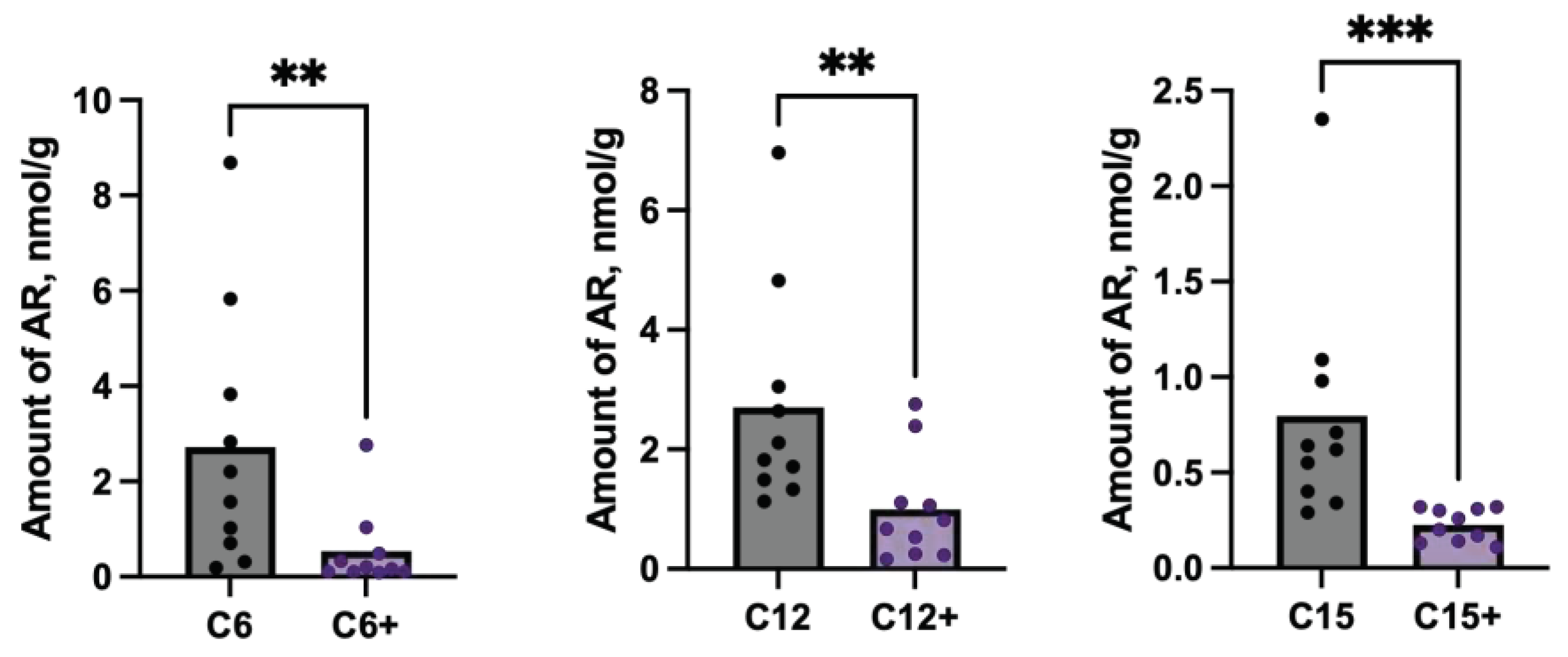

2.2. Estimation of ARs content in C57BL/6 and db/db and Ldlr (-/-) mice’s feces in dependence on diet content

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental animals and study design

4.2. Fecal microbiota transplantation

4.3. Quantitative analysis of ARs

4.4. Statistical data analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gomaa, E.Z. Human Gut Microbiota/Microbiome in Health and Diseases: A Review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 2019–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, M.J.A.; Santos, A.; Prada, P.O. Linking Gut Microbiota and Inflammation to Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Physiology 2016, 31, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabolotneva, A.A.; Shatova, O.P.; Sadova, A.A.; Shestopalov, A.V.; Roumiantsev, S.A. An Overview of Alkylresorcinols Biological Properties and Effects. J Nutr Metab 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, Y.; Ogata, H.; Goto, S. Type III Polyketide Synthases: Functional Classification and Phylogenomics. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, S.-G.; Lee, S.K. 4-Hexylresorcinol-Induced Protein Expression Changes in Human Umbilical Cord Vein Endothelial Cells as Determined by Immunoprecipitation High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funabashi, M.; Funa, N.; Horinouchi, S. Phenolic Lipids Synthesized by Type III Polyketide Synthase Confer Penicillin Resistance on Streptomyces Griseus. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 13983–13991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, C.P.; Lee, H.Y.; Khosla, C. Evolution of Polyketide Synthases in Bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 4595–4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, M.B.; Izumikawa, M.; Bowman, M.E.; Udwary, D.W.; Ferrer, J.-L.; Moore, B.S.; Noel, J.P. Crystal Structure of a Bacterial Type III Polyketide Synthase and Enzymatic Control of Reactive Polyketide Intermediates. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 45162–45174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Verma, P.; Singh, A.K.; Kaushik, S.; Pandey, R.; Shi, C.; Kaur, H.; Chawla, M.; Elechalawar, C.K.; Kumar, D.; et al. Polyketide Quinones Are Alternate Intermediate Electron Carriers during Mycobacterial Respiration in Oxygen-Deficient Niches. Mol Cell 2015, 60, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiuk, M.; Kozubek, A. Biological Activity of Phenolic Lipids. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2010, 67, 841–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozubek, A.; Tyman, J.H.P. Resorcinolic Lipids, the Natural Non-Isoprenoid Phenolic Amphiphiles and Their Biological Activity. Chem Rev 1999, 99, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aura, A.-M. Microbial Metabolism of Dietary Phenolic Compounds in the Colon. Phytochemistry Reviews 2008, 7, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda-Chodak, A.; Tarko, T.; Satora, P.; Sroka, P. Interaction of Dietary Compounds, Especially Polyphenols, with the Intestinal Microbiota: A Review. Eur J Nutr 2015, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LAMPE, J.; CHANG, J. Interindividual Differences in Phytochemical Metabolism and Disposition. Semin Cancer Biol 2007, 17, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechner, A. Colonic Metabolism of Dietary Polyphenols: Influence of Structure on Microbial Fermentation Products. Free Radic Biol Med 2004, 36, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selma, M. v.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Interaction between Phenolics and Gut Microbiota: Role in Human Health. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, Y.A.; Tutel’yan, A. v.; Loiko, N.G.; Buck, J.; Sidorenko, S. v.; Lazareva, I.; Gostev, V.; Manzen’yuk, O.Y.; Shemyakin, I.G.; Abramovich, R.A.; et al. The Use of 4-Hexylresorcinol as Antibiotic Adjuvant. PLoS ONE 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukharin, O. v; Perunova, N.B.; El’-Registan, G.I.; Nikolaev, I.A.; Iavnova, S. v; Molostov, E. v; Kirillov, D.A. [Influence of Chemical Analogue of Extracellular Microbial Autoregulators on Antilysozyme Activity of Bacteria]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol.

- Oishi, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Itoh, N.; Nakao, R.; Yasumoto, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Kikuchi, Y.; Fukudome, S.; Okita, K.; Takano-Ishikawa, Y. Wheat Alkylresorcinols Suppress High-Fat, High-Sucrose Diet-Induced Obesity and Glucose Intolerance by Increasing Insulin Sensitivity and Cholesterol Excretion in Male Mice. J Nutr 2015, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria, U.; Fernández-Quintela, A.; Milagro, F.I.; Aguirre, L.; Martínez, J.A.; Portillo, M.P. Impact of Polyphenols and Polyphenol-Rich Dietary Sources on Gut Microbiota Composition. J Agric Food Chem 2013, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, M.G.; Bisogno, T.; Palazzo, E.; Thomas, A.; van der Stelt, M.; Brizzi, A.; de Novellis, V.; Marabese, I.; Ross, R.; van de Doelen, T.; et al. In Vitro and in Vivo Pharmacology of Synthetic Olivetol- or Resorcinol-Derived Cannabinoid Receptor Ligands. Br J Pharmacol 2006, 149, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piomelli, D. The Molecular Logic of Endocannabinoid Signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003, 4, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevalainen, T. Recent Development of CB2 Selective and Peripheral CB1/CB2 Cannabinoid Receptor Ligands. Curr Med Chem 2013, 21, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuddihey, H.; MacNaughton, W.K.; Sharkey, K.A. Role of the Endocannabinoid System in the Regulation of Intestinal Homeostasis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 14, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, S.; Pechereau, F.; Leblanc, N.; Boubertakh, B.; Houde, A.; Martin, C.; Flamand, N.; Silvestri, C.; Raymond, F.; Di Marzo, V.; et al. Rapid and Concomitant Gut Microbiota and Endocannabinoidome Response to Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. mSystems 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpouya-Bahrami, P.; Chitrala, K.N.; Ganewatta, M.S.; Tang, C.; Murphy, E.A.; Enos, R.T.; Velazquez, K.T.; McCellan, J.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P. Blockade of CB1 Cannabinoid Receptor Alters Gut Microbiota and Attenuates Inflammation and Diet-Induced Obesity. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 15645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, M.N.; Shahbazi, F.; Rondeau-Gagné, S.; Trant, J.F. The Biosynthesis of the Cannabinoids. J Cannabis Res 2021, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagzoog, A.; Cabecinha, A.; Abramovici, H.; Laprairie, R.B. Modulation of Type 1 Cannabinoid Receptor Activity by Cannabinoid By-Products from Cannabis Sativa and Non-Cannabis Phytomolecules. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J. Carberry Composition of Olivetol and Method of Use to Reduce or Inhibit the Effects of Tetrahydrocannabinol in the Human Body 2017.

- Yang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Li, Y.; El-kott, A.F.; Bani-Fwaz, M.Z. Anti-Breast Adenocarcinoma and Anti-Urease Anti-Tyrosinase Properties of 5-Pentylresorcinol as Natural Compound with Molecular Docking Studies. J Oleo Sci 2022, 71, ess22024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, S.; Ohama, M.; Suzuki, M.; Katayanagi, Y.; Kayashima, Y.; Tezuka, H. Research Article Short Alkyl Chain-Length Resorcinol Olivetol Protects Against Obesity with Mitochondrial Activation by Pgc-1α Deacetylation. SSRN Electronic Journal 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, C.G.; Croft, K.D.; Kennedy, D.O.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. The Effects of Polyphenols and Other Bioactives on Human Health. Food Funct 2019, 10, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rejman, J.; Kozubek, A. Long-Chain Orcinol Homologs from Cereal Bran Are Effective Inhibitors of Glycerophosphate Dehydrogenase. Cellular and Molecular Biology Letters 1997, 2, 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Shestopalov, A.V.; Gaponov, A.M.; Zabolotneva, A.A.; Appolonova, S.A.; Markin, P.A.; Borisenko, O.V.; Tutelyan, A.V.; Rumyantsev, A.G.; Teplyakova, E.D.; Shin, V.F.; et al. Alkylresorcinols: New Potential Bioregulators in the Superorganism System (Human–Microbiota). Biology Bulletin 2022, 49, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, T.A.F.; Rogero, M.M.; Hassimotto, N.M.A.; Lajolo, F.M. The Two-Way Polyphenols-Microbiota Interactions and Their Effects on Obesity and Related Metabolic Diseases. Front Nutr 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarewicz, M.; Drożdż, I.; Tarko, T.; Duda-Chodak, A. The Interactions between Polyphenols and Microorganisms, Especially Gut Microbiota. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeli, S.; Böhnke, J.; Feldpausch, M.; Gorzelniak, K.; Janke, J.; Bátkai, S.; Pacher, P.; Harvey-White, J.; Luft, F.C.; Sharma, A.M.; et al. Activation of the Peripheral Endocannabinoid System in Human Obesity. Diabetes 2005, 54, 2838–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muccioli, G.G.; Naslain, D.; Bäckhed, F.; Reigstad, C.S.; Lambert, D.M.; Delzenne, N.M.; Cani, P.D. The Endocannabinoid System Links Gut Microbiota to Adipogenesis. Mol Syst Biol 2010, 6, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Dopart, R.; Kendall, D.A. Controlled Downregulation of the Cannabinoid CB1 Receptor Provides a Promising Approach for the Treatment of Obesity and Obesity-Derived Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Stress Chaperones 2016, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, D.A.; Gentry, C.; Alenmyr, L.; Killander, D.; Lewis, S.E.; Andersson, A.; Bucher, B.; Galzi, J.-L.; Sterner, O.; Bevan, S.; et al. TRPA1 Mediates Spinal Antinociception Induced by Acetaminophen and the Cannabinoid Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabiorcol. Nat Commun 2011, 2, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | AR | p_value | Spearmen correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stool samples of adults | |||

| Berger-Parker Dominance | C15 | 0.015 | 0.26 |

| Inverse Simpson Index | C15 | 0.045 | 0.21 |

| Gini–Simpson Index | C15 | 0.045 | 0.21 |

| Distinct OTUs | C0 | 0.019 | 0.26 |

| Chao1 Richness | C0 | 0.021 | 0.25 |

| Distinct OTUs | C3 | 0.030 | 0.24 |

| Chao1 Richness | C3 | 0.042 | 0.22 |

| Stool samples of children | |||

| Inverse Simpson Index | C5 | 0.033 | 0.26 |

| Gini–Simpson Index | C5 | 0.033 | 0.26 |

| Group of animals | Number of animals | Material for transplantation | Route of administration | Microbiota donor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (control) | 10 | 0,9% NaCl solution | Intragastric | N/A |

| 2 | 10 | Fecal microbiota sample from Donor 1 | Intragastric | Donor 1. Male, 42 yo |

| 3 | 10 | Fecal microbiota sample from Donor 2 | Intragastric | Donor 2. Male, 36 yo |

| 4 | 10 | Fecal microbiota sample from Donor 3 | Intragastric | Donor 3. Female, 28 yo |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).