Submitted:

19 July 2023

Posted:

20 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Hg0(g) – elemental mercury vapor, sparingly soluble in water, capable of persisting in the air for up to two years and capable of long-range transport.

- Hg2+(g) – oxidized form of mercury, forming easily soluble compounds in water that remain in the air for several days to several weeks.

- Hg(p) – mercury bound or adsorbed to fly ash particles, persisting in the atmosphere for several days to several weeks, and spreading only on a local scale [11].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fuels

- three different samples of hard coal (C1, C2 and C3),

- low-emission carbon fuel produced using the pyrolysis process, specially prepared for test purposes for use in residential heating (BC),

- a mixture of hard coal and low-emission carbon fuel with mass shares respectively 0.85:0.15 (CBC).

2.2. Boilers

- A manually fueled boiler with a nominal power of 12 kW (boiler no. 1 – B1).

- A manually fueled boiler with a nominal power of 15 kW (boiler no. 2 – B2).

- Boilers with automatic fuel feeding and a nominal power of 100 kW (boiler no. 3 – B3).

- A boiler with automatic fuel feeding and a nominal power of 24 kW (boiler no. 4 –B4).

- A boiler with automatic fuel feeding and a nominal power of 150 kW (boiler no. 5 – B5).

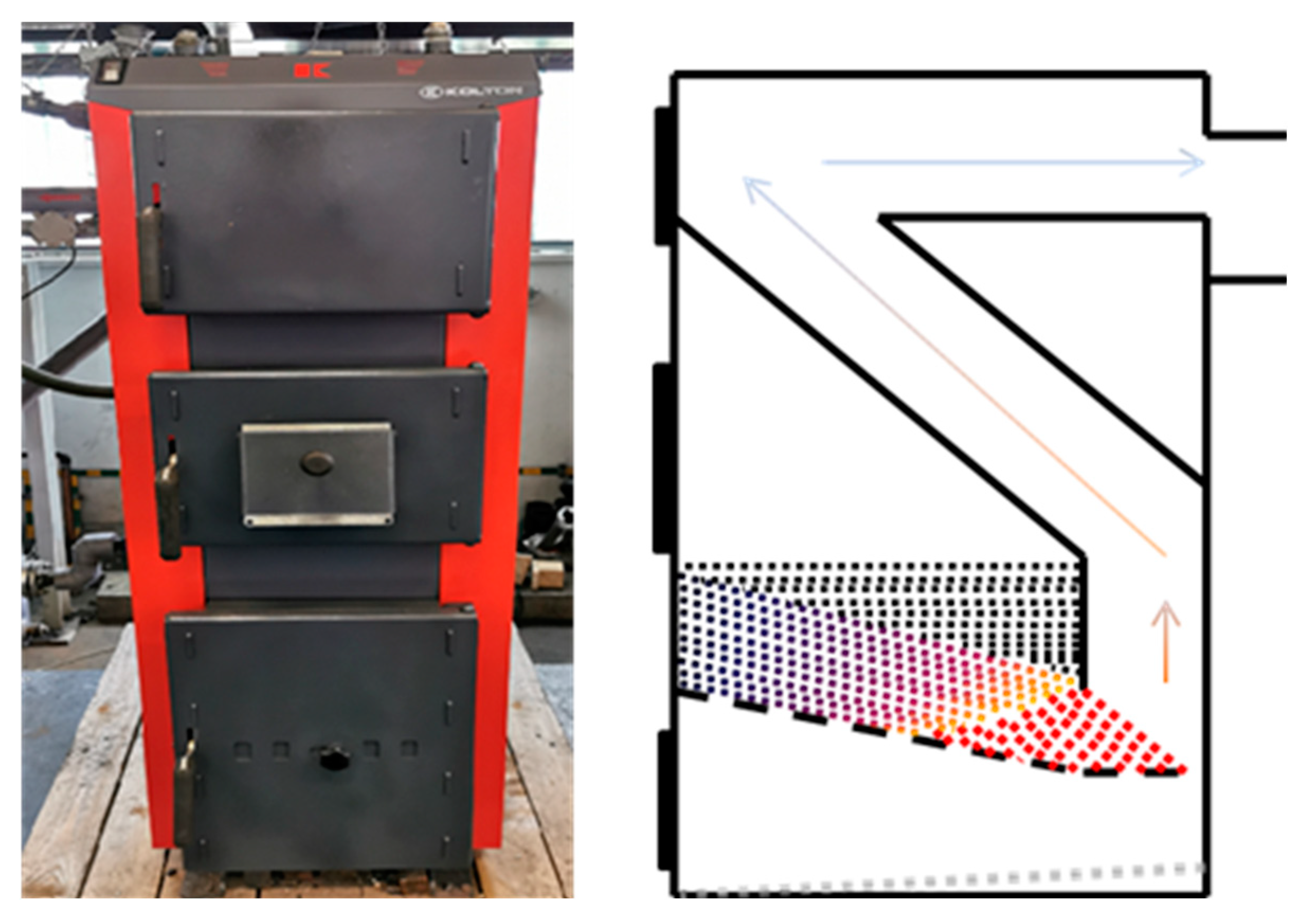

2.2.1. Boiler no. 1 (B1)

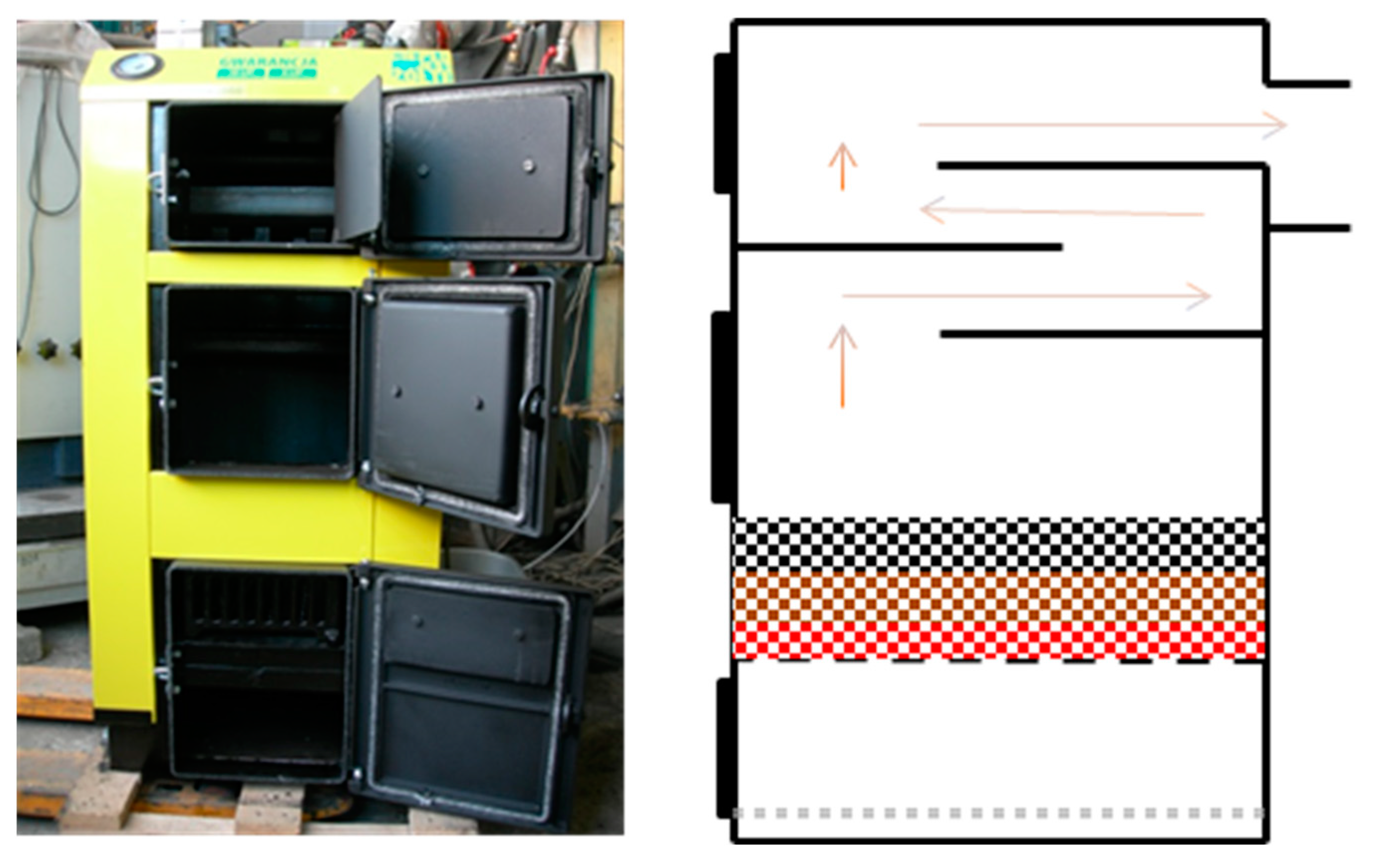

2.2.2. Boiler no. 2 (B2)

2.2.3. Boiler no. 3 (B3)

2.2.4. Boiler no. 4 (B4)

2.2.5. Boiler no. 5 (B5)

2.3. Experiments

2.3.1. Laboratory tests

2.3.2. Field trials

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kabata-Pendias, A.; Pendias, H. Biogeochemistry of trace elements, 2nd ed.; PWN Scientific Publisher: Warsaw, Poland, 1999; p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.B.; Qiu, G.L.; Fu, X.W.; He, T.R.; Li, P.; Wang, S.F. Mercury pollution in the environment. Progress in chemistry 2009, 21, 436–457. [Google Scholar]

- UN Environment, 2019. Global Mercury Assessment 2018. UN Environment Programme, Chemicals and Health Branch Geneva, Switzerland ISBN: 978-92-807-3744-8.

- Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme: Technical Background Report for the Global Mercury Assessment. Oslo 2017.

- Wichliński, M. Emisja rtęci z polskich elektrowni w świetle konkluzji BAT. Polityka energetyczna 2017, 20, pp–79. [Google Scholar]

- Pilar, L.; Borovec, K.; Szeliga, Z.; Górecki, J. Mercury emission from three lignite-fired power plants in the Czech Republic. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 212, 106628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WysokieNapiecie.pl. Available online: https://wysokienapiecie.pl/81733-produkcja-energii-elektrycznej-w-polsce/ (accessed on 17/07/2023).

- GLOBENERGIA. Available online: https://globenergia.pl/ponad-21-energii-pochodzilo-z-oze-miks-energetyczny-i-struktura-produkcji-energii-w-polsce-w-2022-r/ (accessed on 17/07/2023).

- Burmistrz, P.; Kogut, K.; Marczak, M.; Zwoździak, J. Lignites and subbituminous coals combustion in Polish power plants as a source of anthropogenic mercury emission. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 152, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pešek, J.; Bencko, V.; Sýkorová, I.; Vašíček, M.; Michna, O. Martínek, K. Some trace elements in coal of the Czech Republic, environment and health protection implications. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2005, 13, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Czaplicka, M.; Pyta, H. Transformations of mercury in processes of solid fuel combustion – review. Archives of Environmental Protection 2017, 43, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WSZYSTKOoEMISJACH.pl. Available online: https://wszystkooemisjach.pl/342/konkluzje-bat-dla-duzych-obiektow-energetycznego-spalania-lcp (accessed on 17/07/2023).

- Assessment of the potential for the application of high-efficiency cogeneration and efficient district heating and cooling in the Czech Republic. Ministerstvo Prumyslu a Obchodu, 2020.

- DIRECTIVE 2009/125/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 October 2009 establishing a framework for the setting of ecodesign requirements for energy-related products. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02009L0125-20121204 (accessed on 18/07/2023).

- Energy consumption in households in 2018. GUS, Warsaw 2019.

- Matuszek, K.; Hrycko, P.; Stelmach, S.; Sobolewski, A. Carbonaceous smokeless fuel and modern small-scale boilers limiting the residential emission. Part 1. General aspects. Przemysł chemiczny 2016, 95, 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Matuszek, K.; Hrycko, P.; Stelmach, S.; Sobolewski, A. Carbonaceous smokeless fuel and modern small-scale boilers limiting the residential emission. Part 2. Experimental tests of a new carbonaceous smokeless fuel. Przemysł chemiczny 2016, 95, 228–230. [Google Scholar]

- PN-EN 303-5+A1:2023-05 Kotły grzewcze – Część 5: Kotły grzewcze na paliwa stałe z ręcznym i automatycznym zasypem paliwa o mocy nominalnej do 500 kW – Terminologia, wymagania, badania i oznakowanie.

- Wichliński, M.; Kobyłecki, R.; Bis, Z. Emisja rtęci podczas termicznej obróbki paliw. Polityka Energetyczna 2011, 14, 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Misztal, E.; Chmielniak, T.; Mazur, I.; Sajdak, M. The release and reduction of mercury from solid fuels through thermal treatment prior to combustion. Energies 2022, 15(21), 7987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichliński, M.; Kobyłecki, R.; Bis, Z. Niskotemperaturowa obróbka termiczna węgli wzbogaconych i niewzbogaconych w celu obniżenia zawartości rtęci. Polityka Energetyczna 2015, 18, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielniak, T.; Głód, K.; Kopczyński, M. Piroliza węgla dla obniżenia emisji rtęci z procesów spalania do atmosfery. In Nowe technologie spalania i oczyszczania spalin, Nowak, W.; Pronobis, M., Ed.; Publisher: Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej, Poland, 2010; pp. 389–411. [Google Scholar]

- Dziok, T. Production of low-mercury solid fuel by mild pyrolysis process. Energies 2023, 16(7), 3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Miranda, N,. Rodríguez, E.; Lopez-Anton, M.A.; García, R.; Martínez-Tarazona, M.R. A new approach for retaining mercury in energy generation processes: regenerable carbonaceous sorbents. Energies 2017, 10(9), 1311. [CrossRef]

- Telenga-Kopyczyńska, J.; Konieczyński, J.; Sobolewski, A. Emisja rtęci z procesu koksowania węgla. In Proceedings of the KOKSOWNICTWO Conference, Poland, 3–5.10.2012. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Unit | C1 | C2 | C3 | BC | CBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| moisture content | % | 4.0±0.01 | 6.6±0.02 | 13.1±0.08 | 14.9±0.09 | 7.8±0.02 |

| ash content | % | 6.3±0.01 | 11.1±0.02 | 7.0±0.01 | 6.5±0.01 | 6.2±0.01 |

| volatile matter content | % | 17.6±0.06 | 29.4±0.09 | 32.1±0.10 | 3.1±0.01 | 28.6±0.09 |

| fixed carbon | % | 72.1±0.08 | 52.9±0.13 | 47.8±0.19 | 75.5±0.11 | 57.4±0.12 |

| LCV | J/g | 29497 | 25633 | 24393 | 26065 | 27373 |

| Parameter | Unit | C1 | C2 | C3 | BC | CBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| carbon content | % | 83.1±0.4 | 72.6±0.4 | 72.7±0.4 | 88.6±0.4 | 77.4±0.4 |

| hydrogen content | % | 3.2±0.01 | 4.0±0.01 | 4.8±0.01 | 1.3±0.00 | 4.3±0.01 |

| sulfur content | % | 0.9±0.00 | 0.3±0.00 | 1.3±0.00 | 0.4±0.00 | 0.8±0.00 |

| nitrogen content | % | 1.1±0.00 | 2.0±0.00 | 1.3±0.00 | 1.6±0.00 | 1.5±0.00 |

| oxygen content | % | 5.2±0.42 | 9.2±0.43 | 11.9±0.42 | 0.4±0.41 | 9.3±0.42 |

| mercury content | mg/kg | 0.146±0.015 | 0.037±0.004 | 0.098±0.010 | 0.007±0.001 | 0.036±0.004 |

| fuel | |||||

| C1 | C2 | C3 | BC | CBC | |

| boiler no. 1 | B1/C1 | ||||

| boiler no. 2 | B2/C2 | B2/BC | |||

| boiler no. 3 | B3/C3 | B3/CBC | |||

| boiler no. 4 | B4/C3 | B4/CBC | |||

| boiler no. 5 | B5/C3 | B5/CBC | |||

| Parameter | Unit | B1/C1 | B2/C2 | B2/BC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| energy parameters | ||||

| fuel flow | kg/h | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.8 |

| lambda | - | 1.95 | 2.21 | 3.30 |

| boiler efficiency | % | 76.0 | 72.2 | 67.6 |

| boiler power | kW | 12.4 | 15.4 | 18.6 |

| relative thermal load of the boiler | % | 103.4 | 102.7 | 124.0 |

| flue gas parameters | ||||

| flue gas temperature | °C | 187.8 | 256.0 | 254.5 |

| chimney draught | Pa | -11.8 | -25.2 | -31.5 |

| O2 concentration | % | 10.33 | 11.57 | 14.57 |

| CO2 concentration | 9.40 | 8.08 | 5.84 | |

| converted to 10% O2 | 9.69 | 9.42 | 10.00 | |

| CO concentration | mg/Nm3 | 436.1 | 4256.1 | 2755.1 |

| converted to 10% O2 | 458.9 | 4967.4 | 4712.1 | |

| SO2 concentration | 967.8 | 259.8 | 178.5 | |

| converted to 10% O2 | 996.7 | 303.0 | 305.3 | |

| NO concentration | 161.6 | 143.6 | 47.9 | |

| converted to 10% O2 | 255.1 | 256.6 | 112.8 | |

| dust concentration | 22.3 | 144.4 | 31.1 | |

| converted to 10% O2 | 23.0 | 166.9 | 53.2 | |

| TOC concentration | 31.5 | 101.2 | 45.9 | |

| converted to 10% O2 | 32.5 | 116.7 | 78.6 | |

| emissions | ||||

| CO2 | kg/GJ | 95.8 | 91.2 | 93.4 |

| CO | g/GJ | 231.1 | 2433.2 | 2229.4 |

| SO2 | g/GJ | 498.2 | 148.4 | 144.4 |

| NO | g/GJ | 127.4 | 125.7 | 59.4 |

| dust | g/GJ | 11.5 | 81.8 | 25.2 |

| TOC | g/GJ | 16.3 | 57.1 | 37.2 |

| Parameter | Unit | B3/C3 | B3/CBC | B4/C3 | B4/CBC | B5/C3 | B5/CBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| energy parameters | |||||||

| fuel flow | kg/h | 6.5 | 6.3 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 12.2 | 11.7 |

| lambda | - | 2.4 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 4.1 | 3.9 |

| boiler efficiency | % | 88.5 | 87.5 | 71.4 | 79.5 | 70.6 | 74.3 |

| boiler power | kW | 39.0 | 41.9 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 58.4 | 66.1 |

| relative thermal load of the boiler | % | 39.0 | 41.9 | 18.3 | 20.0 | 38.9 | 44.1 |

| flue gas parameters | |||||||

| flue gas temperature | °C | 117.6 | 118.6 | 202.3 | 207.0 | 172.3 | 181.6 |

| chimney draught | Pa | 30.3 | 30.7 | 22.0 | 25.0 | 20.7 | 28.9 |

| O2 concentration | % | 12.52 | 11.81 | 15.60 | 13.48 | 16.00 | 15.73 |

| CO2 concentration | 7.13 | 7.86 | 4.48 | 6.43 | 4.18 | 4.45 | |

| converted to 10% O2 | 9.25 | 9.41 | 9.13 | 9.41 | 9.20 | 9.29 | |

| CO concentration | mg/Nm3 | 654.6 | 607.9 | 1507.1 | 660.9 | 475.9 | 462.0 |

| converted to 10% O2 | 849.1 | 727.8 | 3069.4 | 967.2 | 1047.9 | 964.9 | |

| SO2 concentration | 1207.7 | 786.3 | 570.0 | 542.8 | 611.3 | 396.5 | |

| converted to 10% O2 | 1566.6 | 941.3 | 1160.8 | 794.4 | 1346.1 | 828.1 | |

| NO concentration | 345.2 | 342.0 | 294.9 | 259.4 | 187.8 | 197.4 | |

| converted to 10% O2 | 447.8 | 409.3 | 600.7 | 379.5 | 413.0 | 412.1 | |

| dust concentration | 128.3-133.8 | 82.7-100.3 | 138.5-151.3 | 89.5-105.1 | 67.6-70.3 | 55.1-62.0 | |

| converted to 10% O2 | 166.4-173.6 | 99.0-120.1 | 282.1-308.2 | 131.0-153.8 | 148.9-154.8 | 115.1-129.5 | |

| emissions | |||||||

| CO2 | kg/GJ | 89.4 | 90.4 | 88.2 | 90.3 | 88.9 | 89.2 |

| CO | g/GJ | 415.1 | 353.5 | 1500.7 | 469.7 | 511.8 | 468.5 |

| SO2 | g/GJ | 765.8 | 457.3 | 567.5 | 385.8 | 657.4 | 402.1 |

| NO | g/GJ | 218.9 | 198.9 | 293.6 | 184.4 | 201.9 | 200.2 |

| dust | g/GJ | 81.4-84.8 | 48.1-58.3 | 137.9-150.7 | 63.6-74.7 | 72.7-75.6 | 55.9-62.9 |

| Parameter | Unit | B1/C1 | B2/C2 | B2/BC | B3/C3 | B3/CBC | B4/C3 | B4/CBC | B5/C3 | B5/CBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hg flux delivered with fuel | mg/kg | 0.140 | 0.035 | 0.006 | 0.085 | 0.033 | 0.085 | 0.033 | 0.085 | 0.033 |

| ng/GJ | 4.75 | 1.37 | 0.23 | 3.48 | 1.21 | 3.48 | 1.21 | 3.48 | 1.21 | |

| amount of Hg delivered with fuel | % | 100 | ||||||||

| amount of Hg remaining in bottom ash | % | 5.76 | 1.92 | 2.75 | 1.83 | 2.90 | 0.78 | 3.05 | 1.99 | 3.74 |

| amount of Hg emitted into the atmosphere | % | 94.24 | 98.08 | 97.25 | 98.17 | 97.10 | 99.22 | 96.95 | 98.01 | 96.26 |

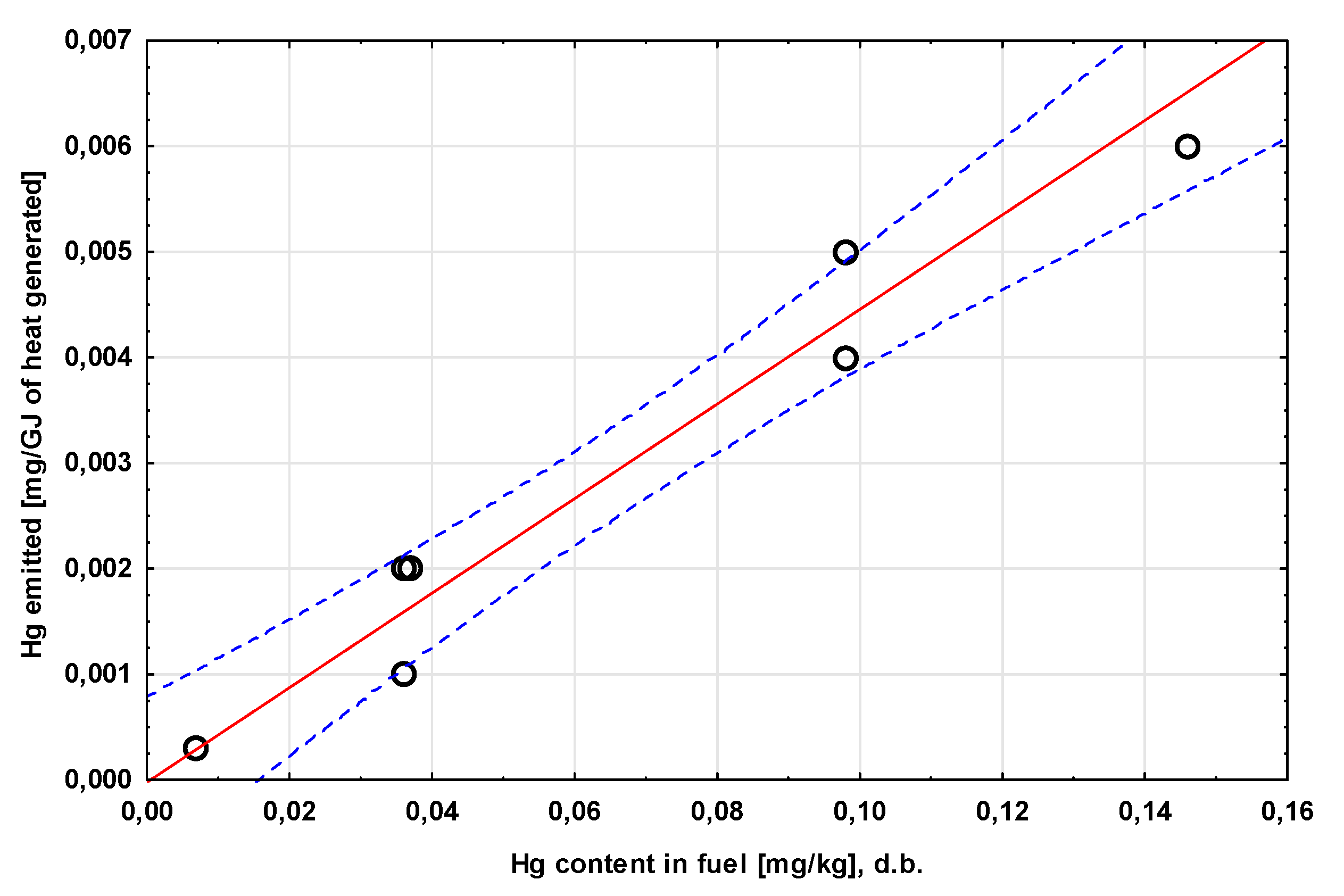

| the amount of Hg emitted with flue gas (including dust) per GJ of useful heat generated | mg/GJ | 6×10-3 | 2×10-3 | 3×10-4 | 4×10-3 | 1×10-3 | 5×10-3 | 1×10-3 | 5×10-3 | 2×10-3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).