Submitted:

18 July 2023

Posted:

19 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Lattice dynamics

2.2. Raman scattering

2.2.1. Raman intensity profiles

2.3. Rigid-ion-model for bulk binary materials

2.4. Rigid-ion-model for (SiC)m/(GeC)n superlattices

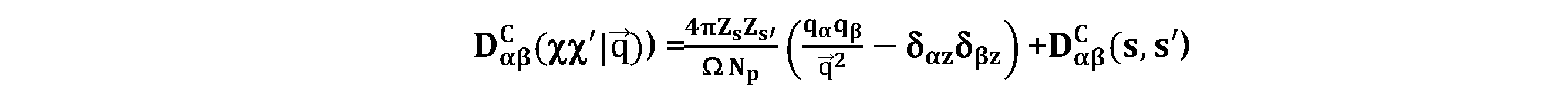

2.4.1. Coulomb interactions in superlattices

3. Numerical computations results and discussions

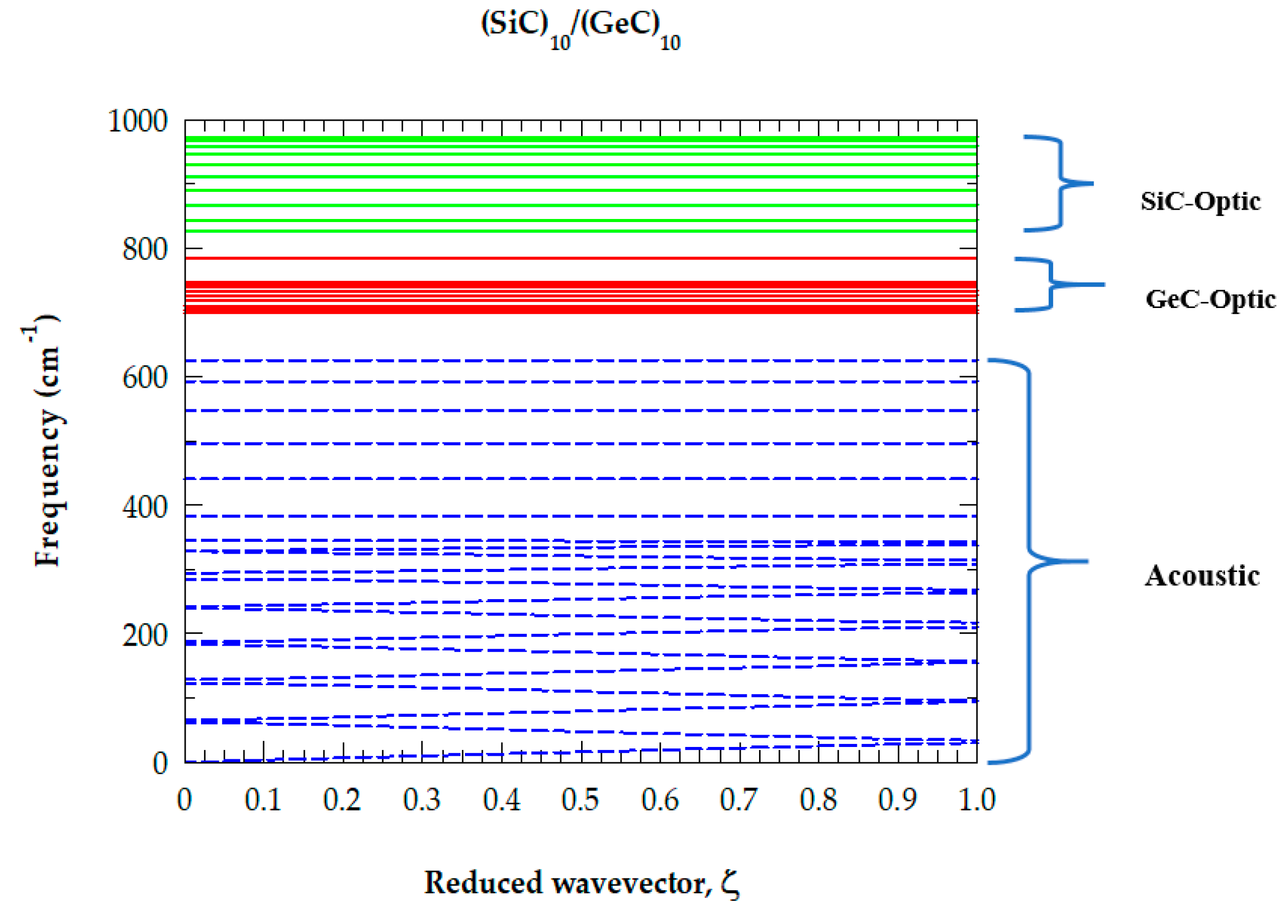

3.1. M-LCM phonon dispersions of (SiC)m/(GeC)n

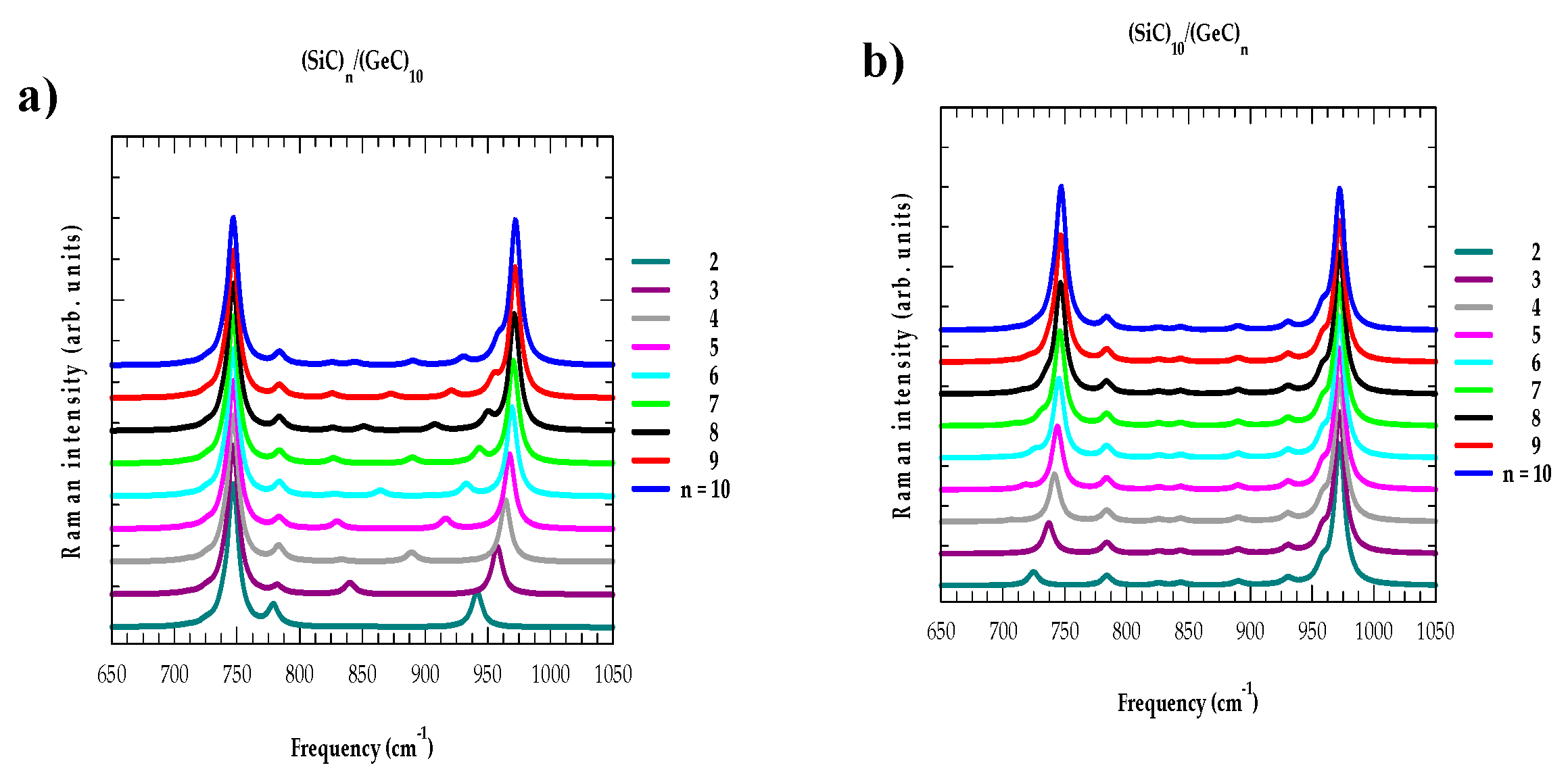

3.2. Raman scattering profiles in SLs

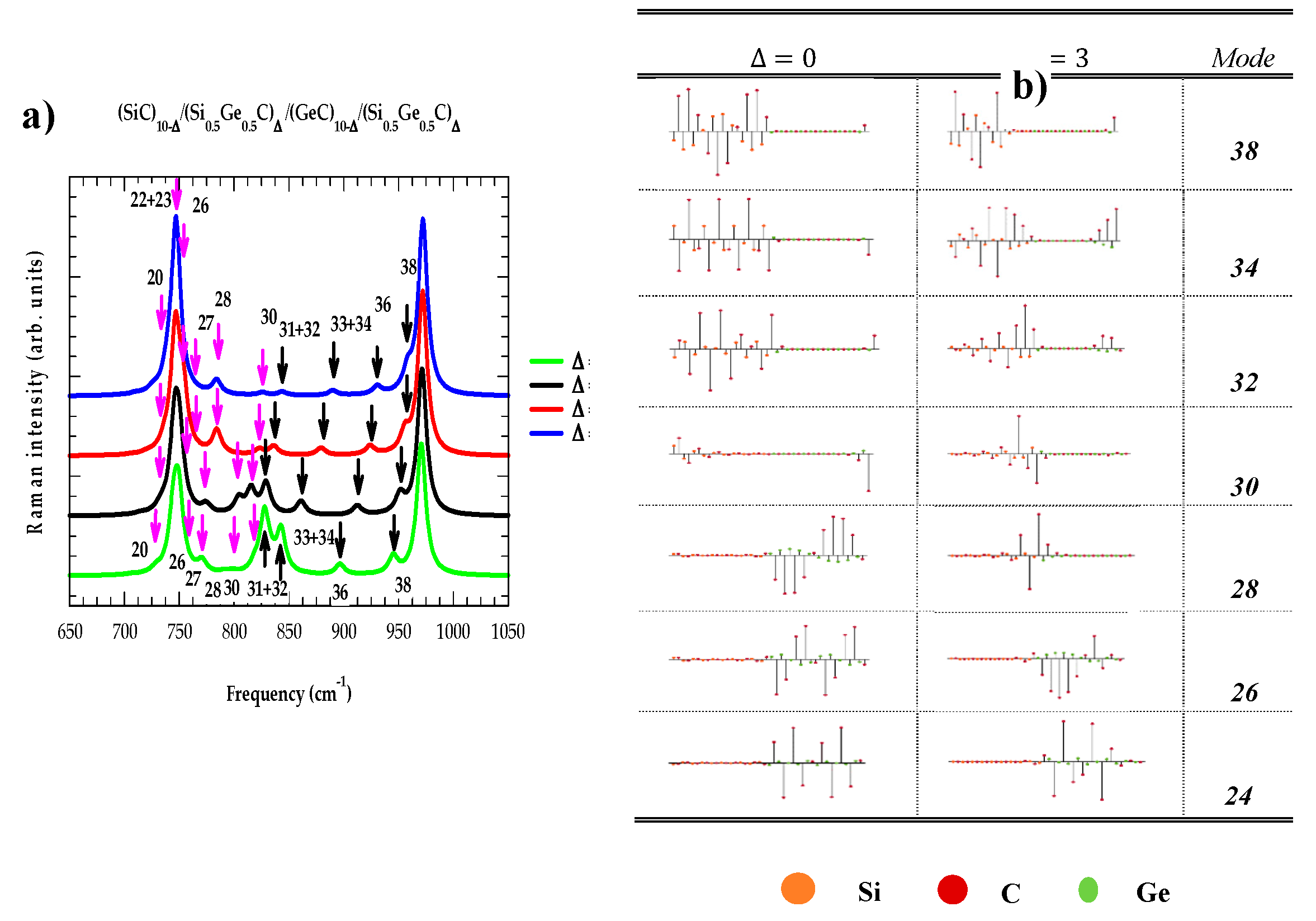

3.3. Atomic displacements in superlattices

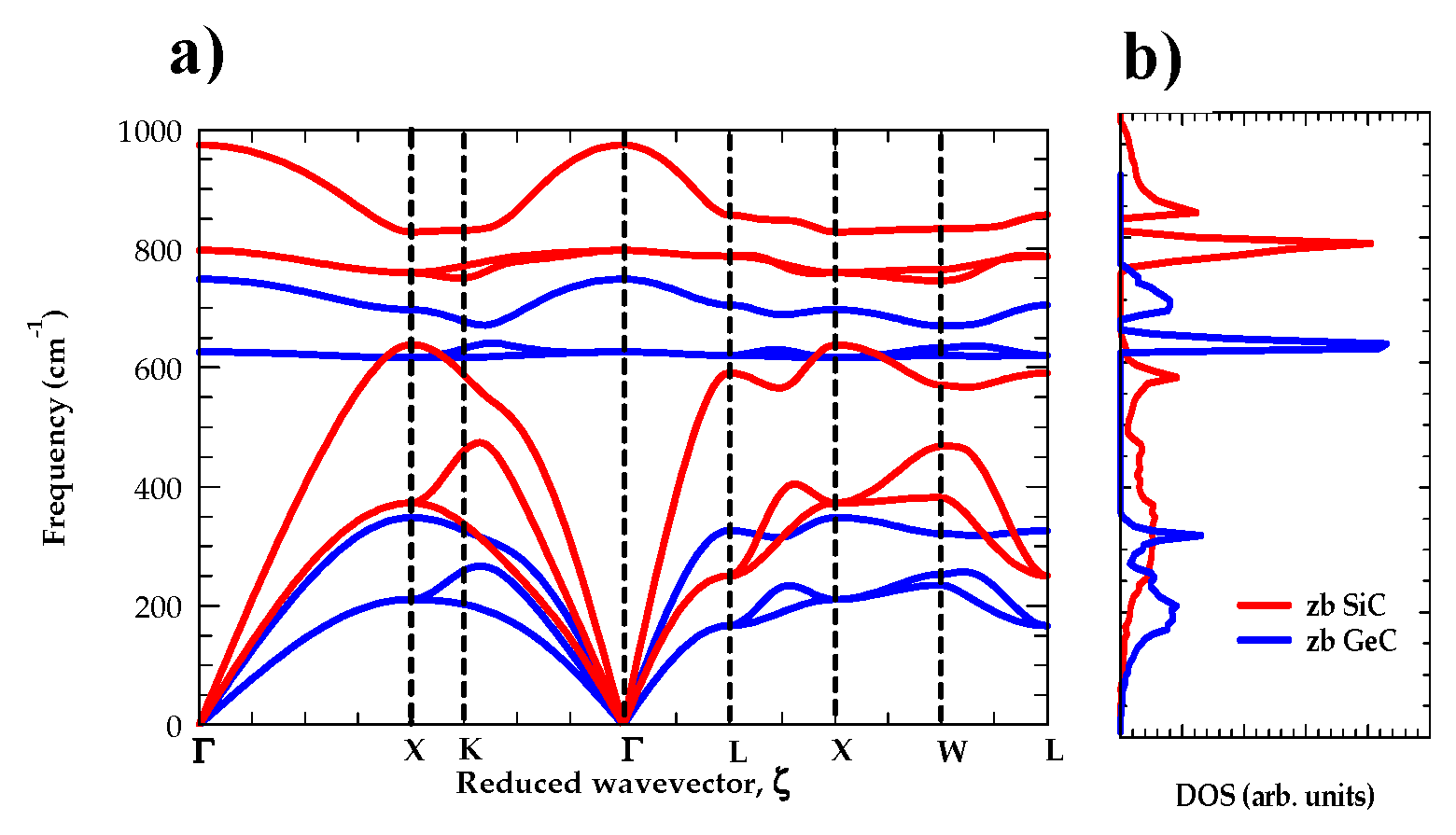

3.4. RIM calculations of bulk SiC, GeC

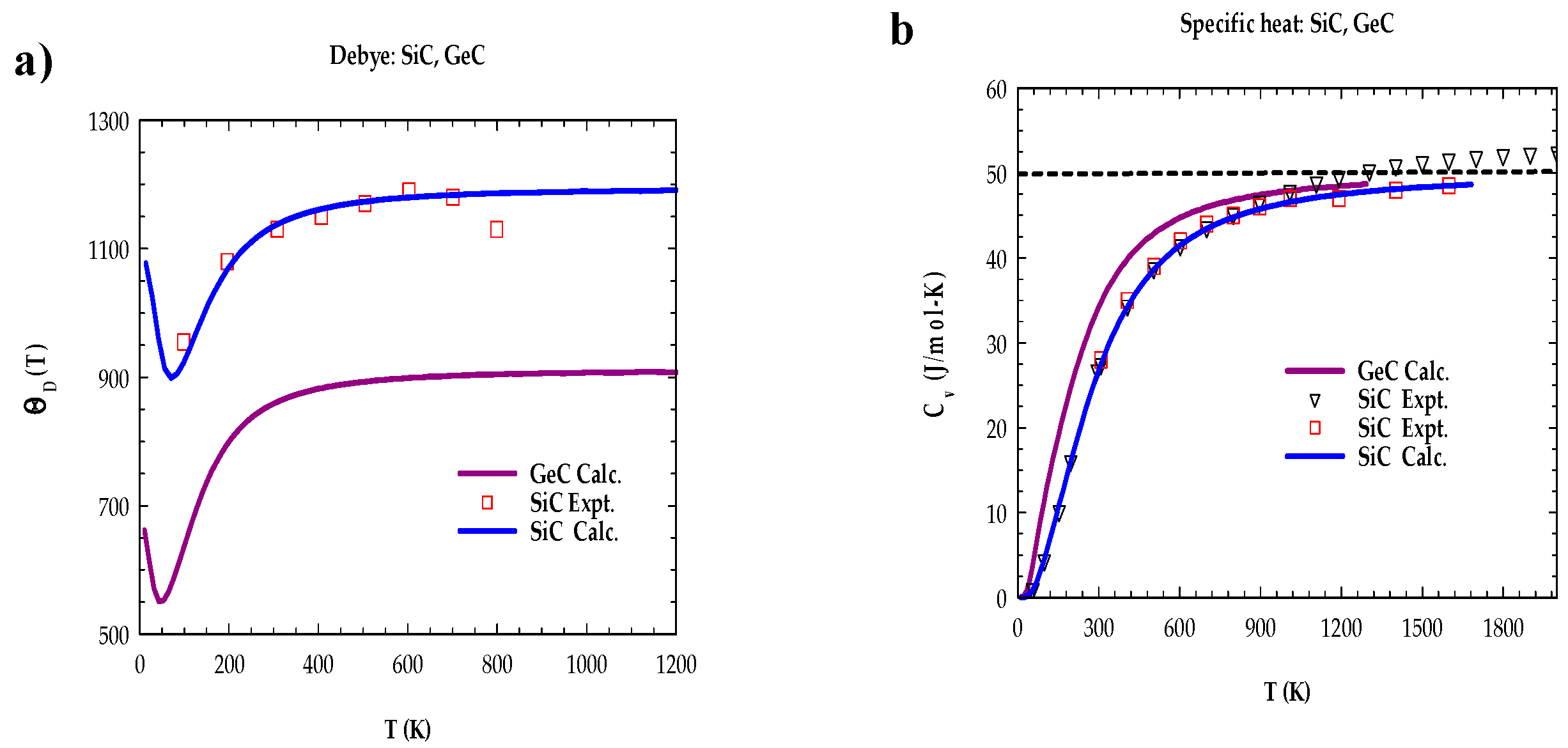

3.4.1. Debye temperature and specific heat of bulk SiC, GeC

3.5. RIM calculations of (SiC)m/(GeC)n SLs

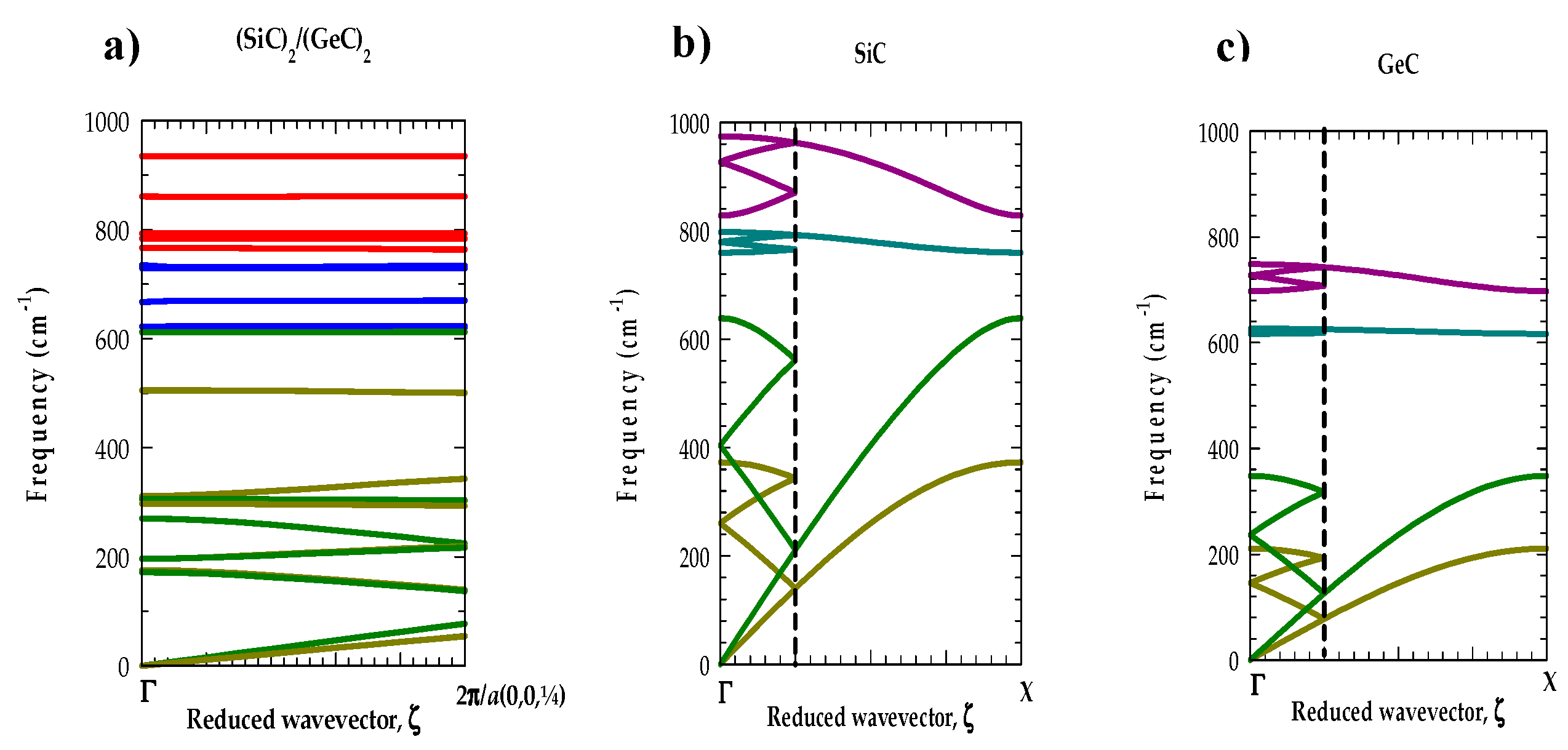

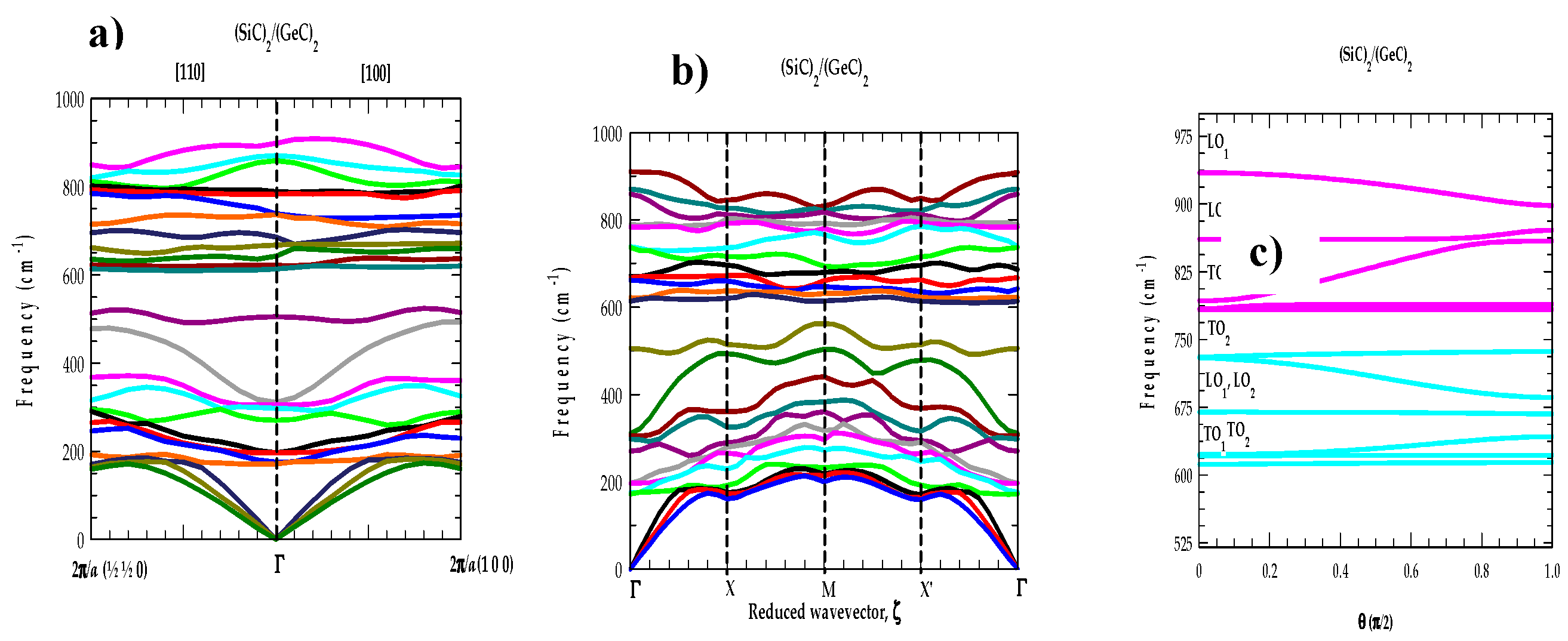

3.5.1. Phonons of SLs along the growth direction

3.5.2. Phonons of SLs perpendicular to the growth direction

3.5.3. Angular dependence of optical phonons in SLs

4. Concluding remarks

Authorship Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Abbas, Ultrawide-bandgap semiconductor of carbon-based materials for meta-photonics-heterostructure, lasers and holographic displays, AAPPS Bulletin, 33:4 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Ji, G.; Li, Z.; Zhong, W.; Wang, F.; Liu, Z.; Xin, W.; Tian, J. Preparation, properties and applications of two-dimensional superlattices. Mater. Horizons 2022, 10, 722–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jmerik, V. Special Issue: Semiconductor Heterostructures (with Quantum Wells, Quantum Dots and Superlattices). Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Tang, D. The in-depth description of phonon transport mechanisms for XC (X=Si, Ge) under hydrostatic pressure: Considering pressure-induced phase transitions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 191, 122851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Guo, X. Y. Guo, X. Wei, S. Gao, W. Yue, Y. Li and G. Shen, Recent advances in carbon-based multi-functional sensors and their applications in electronic skin systems, Adv. Func. Mat. 31, 2104288 (2021).

- Si, Z.; Chai, C.; Zhang, W.; Song, Y.; Yang, Y. Theoretical investigation of group-IV binary compounds in the P4/ncc phase. Results Phys. 2021, 26, 104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zultak, J.; Magorrian, S.J.; Koperski, M.; Garner, A.; Hamer, M.J.; Tóvári, E.; Novoselov, K.S.; Zhukov, A.A.; Zou, Y.; Wilson, N.R.; et al. Ultra-thin van der Waals crystals as semiconductor quantum wells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, N.A.; Løvvik, O.M. Calculation of the anisotropic coefficients of thermal expansion: A first-principles approach. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 167, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Yu, B.; Xu, Y.-E. Tuning Electronic Properties of the SiC-GeC Bilayer by External Electric Field: A First-Principles Study. Micromachines 2019, 10, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. B. Drissi, N. B.-J. L. B. Drissi, N. B.-J. Kanga, S. Lounis, F. Djeffal and S. Haddad, Electron–phonon dynamics in 2D carbon based-hybrids XC (X = Si, Ge, Sn), J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 31, 135702 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Y. M. Baslaev and E. N. Malysheva, Electronic structure of single-layer superlattices (GeC)1/(SiC) 1, (SnC) 1/(SiC) 1, and (SnC) 1/GeC) 1, Semiconductors, 51, 617 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z. Controlling electronic and optical properties of layered SiC and GeC sheets by strain engineering. Mater. Des. 2016, 108, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Veettil, B.P.; Xia, H.; Karuturi, S.K.; Conibeer, G.; Shrestha, S. Synthesis of nano-crystalline germanium carbide using radio frequency magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Films 2015, 592, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Serrano, J. J. Serrano, J. Strempfer, M. Cardona, M. Schwoerer-Böhning, H. Requardt, M. Lorenzen, B.Stojetz, P.Pavone, W.J.Choyke, Determination of the phonon dispersion of zincblende (3C) silicon carbide by inelastic x-ray scattering, Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 4360 (2002). [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, S. X. Zhang, S. Quan, C. Ying and Z. Li, Theoretical investigations on the structural, lattice dynamical and thermodynamical properties of XC (X = Si, Ge and Sn), Sol. State. Commun. 151, 1545 (2011). [CrossRef]

- M. Souadkia, B. M. Souadkia, B. Bennecern and F. Kalarasse, Elastic, vibrational and thermodynamic properties of αSn based group IV semiconductors and GeC under pressure, J. Phys. Chem. Solids,74, 1615–1625 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Q. -J. Liu, Z. Q. -J. Liu, Z. -T. Liu, X. -S. Che, L. -P. Feng, and H. Tian, First-principles calculations of the structural, elastic, electronic, chemical bonding and optical properties of zinc-blende and rock salt GeC, Solid State Sciences, 13, 2177-2184 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Sahnoun, M.; Khenata, R.; Baltache, H.; Rérat, M.; Driz, M.; Bouhafs, B.; Abbar, B. First-principles calculations of optical properties of GeC, SnC and GeSn under hydrostatic pressure. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 2005, 355, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. A. Silva, E. M. A. A. Silva, E. Ribeiro, P. A. Schulz, F.Cerdeira and J. C. Bean, Linear-chain-model interpretation of resonant Raman scattering in GenSim microstructures, Phs. Rev. B 53, 15871 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Sekkal, W.; Zaoui, A. Predictive study of thermodynamic properties of GeC. New J. Phys. 2002, 4, 9–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisielowski, Z. L- Weber and S. Nakamura, Atomic scale indium distribution in a GaN/In0.43Ga0.57N/Al0.1Ga0.9N quantum well structure, Jpn. J. Phys. 36, 6932 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Behr, R. Niebuhr, J. Wagner, K. -H. Bachem and U. Kaufman, Resonant Raman scattering in GaN/(AlGa)N single quantum wells, Appl. Phys. Lett. 70, 363 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Pezoldt, J.; Cimalla, V.; Masri, P.; Schröter, B. The Influence of Surface Preparation on the Properties of SiC on Si(111). Phys. Status solidi (a) 2001, 185, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, G.; Wang, D.-L.; Wu, C.-E.; Wu, C.-J.; Lin, Y.-T.; Lin, H.-H. InAsPSb quaternary alloy grown by gas source molecular beam epitaxy. J. Cryst. Growth 2007, 301-302, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Goldberg, M.E. Y. Goldberg, M.E. Levinshtein, S.L. Rumyantsev, in: M.E. Levinshtein, S.L. Rumyantsev, M.S. Shur (Eds.), Properties of advanced semiconductor materials GaN, AlN, SiC, BN, SiC, SiGe, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 2001, pp. 93–148; G.A. Slack, S.F. Bartram, Thermal expansion of some diamond like crystals, J. Appl. Phys. 46, 89 (1975).

- E.L. Kern, D.W. Hamill, H.W. Deem, H.D. Sheets, Thermal properties of β-silicon carbide from 20 to 2000 °C, Mater. Res. Bull. 4, 25 (1969). [CrossRef]

- T-Y. Seong, G. R. T-Y. Seong, G. R. Booker, A. G. Norman, and G. B. Stringfellow, Modulated Structures and Atomic Ordering in InPySb1-y Layers Grown by Organometallic Vapor Phase Epitaxy, Jpn. J. of Appl. Phys., 47, 2209–2212 (2008). [CrossRef]

- K. W. Böer and U. W. Pohl, in Semiconductor Physics, 2nd Edition (Springer Nature, Switzerland, 2023), Part V Defects: Optical properties of defects, p.

- V. V. Romanov, B. S. V. V. Romanov, B. S. Ermakov, V. A. Kozhevnikov, K. F. Stelmakh and S. A. Vologzhanina, Lanthanide doping of AIIIBV crystals, IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 826, 012010 (2020).

- Wang, B.; Nolan, R.; Marshall, H. COVID-19 Immunisation, Willingness to Be Vaccinated and Vaccination Strategies to Improve Vaccine Uptake in Australia. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, S. Properties of Semiconductor Alloys. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Zou, M.; Lu, D.; Chen, H.; Wang, B.; Wang, S.; Xu, F. Probing Surface Information of Alloy by Time of Flight-Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometer. Crystals 2021, 11, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaren, I.; Annand, K.J.; Black, C.; Craven, A.J. EELS at very high energy losses. Microscopy 2017, 67, i78–i85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshni, Y. Temperature dependence of the energy gap in semiconductors. Physica 1967, 34, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.M.; Ma, K.Y.; Jaw, D.H.; Cohen, R.M.; Stringfellow, G.B. Photoluminescence of InSb, InAs, and InAsSb grown by organometallic vapor phase epitaxy. J. Appl. Phys. 1990, 67, 7034–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, F.E.; Hebb, M.H. Theoretical Spectra of Luminescent Solids. Phys. Rev. 1951, 84, 1181–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Shionoya, T. S. Shionoya, T. Koda, K. Era, and H. Fujiwara, Nature of luminescence Transitions in ZnS crystals, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn., 19, 1157-1167 (1964). [CrossRef]

- V. Mastelaro, A. M. V. Mastelaro, A. M. Flank, M. C. A. Fantini, D. R. S. Bittencourt, M. N. P. Carren˜o, I. Pereyra, On the structural properties of a-Si1-xCx:H thin films, J. Appl. Phys. 79, 1324–1329 (1996).

- H.W. Zheng, Z.Q. H.W. Zheng, Z.Q. Wang, X.Y. Liu, C.L. Diao, H.R. Zhang, Y.Z. Gu, Local structure and magnetic properties of Mn-doped 3C-SiC nanoparticles, App. Phys. Lett. 99, 222512 (2011). [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Duan, L.; Li, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, J. Investigation of microstructures and optical properties in Mn-doped SiC films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 7070–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Wu, X.; Zhuge, L. The structure and photoluminescence properties of Cr-doped SiC films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 4711–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarde, P.; Flank, A. Analysis of Si-K edge EXAFS in the low k domain. J. de Phys. 1986, 47, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takuo Monguchi, Hiroshi Fujioka, Takeshi Uragami, Hironobu Ohuchi, Kanta Ono, Yuji Baba, Masaharu Oshimaa, X-ray absorption studies of anodized monocrystalline 3C-SiCX-ray absorption studies of anodized monocrystalline 3C-SiC, J. Electrochem. Soc. 147, 741–743 (2000).

- L. Liu, Y. M. L. Liu, Y. M. Yiu, T. K. Sham, L. Zhang and Y. Zhang, Electronic structures and optical properties of 6H- and 3C-SiC microstructures and nanostructures from X-ray absorption fine structures, X-ray excited optical luminescence, and theoretical studies, J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 6966–6975 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Geurts, J. Raman spectroscopy from buried semiconductor interfaces: Structural and electronic properties. Phys. Status solidi (b) 2014, 252, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. -B. Wu, M. J. -B. Wu, M. -L. Lin, X. Cong, H. -N. Liu and P. -H. Tan, Raman spectroscopy of graphene-based materials and its applications in related devices, Chem. Soc. Rev., 47, 1822 (2018).

- X. Cong, M. X. Cong, M. Lin and P. -H. Tan, Lattice vibration and Raman scattering of two-dimensional van der Waals heterostructure, Journal of Semiconductors, 40, 091001 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Omanakuttan, G.; Xu, L.; Liu, T.; Huang, Z.; Lourdudoss, S.; Xie, C.; Sun, Y.-T. Optical and interfacial properties of epitaxially fused GaInP/Si heterojunction. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 055308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Liu, X.-L.; Lin, M.-L.; Tan, P.-H. Application of Raman spectroscopy to probe fundamental properties of two-dimensional materials. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2020, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Song, Y.; Liu, T.; Dong, B.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. Interfacial stress characterization of GaN epitaxial layer with sapphire substrate by confocal Raman spectroscopy. Nanotechnol. Precis. Eng. 2021, 4, 023002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.; Zahn, D.R.T. Plasmon-enhanced Raman spectroscopy of two-dimensional semiconductors. J. Physics: Condens. Matter 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Fix, J.P.; Krayev, A.V.; Flanery, C.; Colgrove, M.; Sulkanen, A.R.; Wang, M.; Liu, G.-Y.; Borys, N.J.; Kung, P. Nanoscale Raman Characterization of a 2D Semiconductor Lateral Heterostructure Interface. ACS Nano 2021, 16, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Velson, N.; Zobeiri, H.; Wang, X. Thickness-Dependent Raman Scattering from Thin-Film Systems. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 2995–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Kunc, Dynamique de réseau de composés ANB8-N présentant la structure de la blende, Ann. Phys. (Paris) 8, 319 (1973-74). [CrossRef]

- Bevk, J.; Mannaerts, J.P.; Feldman, L.C.; Davidson, B.A.; Ourmazd, A. Ge-Si layered structures: Artificial crystals and complex cell ordered superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1986, 49, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, H.-J. Herzog, H. Dambkes, and G. Abstreiter, in Layered Structures and Epitaxy, Vol. 56 of Materials Research Society Proceedings, edited by M. Gibson et al. (MRS, Pittsburgh, 1986).

- B. Zhu and K. A. Chao, Phonon modes and Raman scattering in GaAs/Ga1-xAlxAs, Phys. Rev. B 36, 4906 (1987).

- B. Jusserand and M. Cardona, in Light Scattering in Solids V, edited by M. Cardona and G. Güntherodt, Topics in Applied Physics Vol. 66 Springer, Heidelberg,1989, p. 49.

- Dharma-Wardana, M.W.C.; Aers, G.C.; Lockwood, D.J.; Baribeau, J.-M. Interpretation of Raman spectra of Ge/Si ultrathin superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 1990, 41, 5319–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. Wang, G. A. H. Wang, G. A. Farias and V. N. Freire, Interface related exciton-energy blueshift in GaN/AlxGa1-xN zinc-blende and wurtzite single quantum wells, Phys. Rev. B 60, 5705 (1999). [CrossRef]

- D. N. Talwar in Dilute III-V Nitride Semiconductors and Material Systems—Physics and Technology, edited by A. Erol Springer Series in Materials Science 105 (Springer-Verlag, 2008) Ch. 9, p. 222.

- Plumelle, P.; Vandevyver, M. Lattice Dynamics of ZnTe and CdTe. Phys. Status solidi (b) 1976, 73, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, S. Baroni, P. Giannozzi, and S. de Gironcoli, Effects of disorder on the Raman spectra of GaAs/AlAs superlattices, Phys. Rev. B 45, 4280 (1992). [CrossRef]

- S. -F. Ren, H. S. -F. Ren, H. Chu, and Y. -C. Chang, Anisotropy of optical phonons and interface modes in GaAs-AlAs superlattices, Phys. Rev. B 37, 8899 (1988). [CrossRef]

- Kanellis, New approach to the problem of lattice dynamics of modulated structures: Application to superlattices, Phys. Rev. B 35, 746 (1987). [CrossRef]

- Hurley, D.C.; Tamura, S.; Wolfe, J.P.; Morkoç, H. Imaging of acoustic phonon stop bands in superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 58, 2446–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, S.; Wolfe, J.P. Coupled-mode stop bands of acoustic phonons in semiconductor superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 1987, 35, 2528–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PhysicalParameter Expt. | SiCTheory | GeC Our Theory | Our | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c11 c12 c44 a0 LO(Γ) TO(Γ) LO(X) TO(X) LA(X) TA(X) LO(L) TO(L) LA(L) TA(L) |

39.0a) 14.2a) 25.6a) 4.36a) 972b) 796b) 829b) 761b) 640b) 373b) 838b) 766b) 610b) 266b) 1080c) 1270d) 26.84d) |

38.5-39.0e) 13.2-14.2e) 24.3-25.6e) 4.28-4.40e) 945-956e) 774-783e) 807-829e) 741-755e) 622-629e) 361-366e) 817-838e) 747-766e) 601-610e) 257-261e) |

38.7f) 14.3f) 25.8f) 4.36f) 974f) 797f) 828f) 760f) 639f) 373f) 857f) 787f) 591f) 251f) 1080f) 1186f) 26.24f) |

31.8 e) 10.4 e) 19.2 e) 4.59 e) 748 e) 626 e) 697 e) 617 e) 348 e) 214 e) 705 e) 612 e) 331 e) 162 e) |

31.9f) 10.7f) 17.6f) 4.59f) 749f) 626f) 698f) 617f) 348f) 210f) 705f) 621f) 326f) 166f) 670f) 904f) 34.3f) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).