1. Introduction

The emerging growth of on-demand transport services has contributed to the development of terminology with differences often not being distinct. Several definitions for different and partially overlapping concepts have emerged, including ride-sharing, ride-selling (i.e., commercial, organized by single person), ride-hailing (i.e., commercial, organized by companies) and ridepooling (i.e., commercial, organized by public institutions). Ride-sharing is among the most popular terms in shared mobility, and according to a share of studies in the literature [

1] it refers to the common use of a motor vehicle by a driver and one or several passengers, in order to share the costs. The term is used in different cases to describe: 1) the common use of a motor on-road vehicle for cost compensation in the context of a ride that the driver performs for its own account (referred also as carpooling), or 2) the common use of a professional hired vehicle among various passengers which have the same (or different) destination in order to share the costs of the ride (such as for airport transfers). Therefore, ride-sharing is divided into for-profit and non-profit (i.e., trip cost sharing) services based on the concept that is adopted by each service provider [

1].

“Ride-sharing” within this study is similar to carpooling and it is defined as the transport of persons in a motor vehicle when such transport is incidental to the principal purpose of the driver, which is to reach a destination and not to transport persons for profit [

2]. Ride-sharing has demonstrated limited uptake so far, due to business, economic and technological barriers [

1] and when combined with public transport the uncertainty for its successful planning and implementation is further increased due to multiple stakeholders involved and technological components integrated.

The literature review on multimodal traveling and ride-sharing revealed that various studies have focused on factors affecting users’ behavior towards using ride-sharing services [

1], their impacts [

3,

4,

5], the development of route planning algorithms and apps [

6,

7,

8,

9] and incentives to attract more participants [

10,

11,

12]. However, only a few of them have focused on the planning and implementation process of ride-sharing demonstrations. Most ride-sharing demonstrations are deployed in the framework of research projects or initiatives derived from these [

10,

11,

13].

Ride-sharing although is enabled by mobile applications, it is also a non-technical innovation which implies changes in travel behavior [

14]. Ensuring the participation of both drivers and passengers is a key component for designing a successful ride-sharing service, however, there are additional steps that need to be considered to test a ride-sharing service. In this sense, studying and developing a robust method for planning and implementing ride-sharing demonstrations becomes essential as it has the potential to provide guidance for future pilot schemes [

15].

This paper aims to outline the process of planning and implementing a pilot demonstration in central Athens-Greece regarding multimodal traveling with rail and ride-sharing within the context of the Ride2Rail project. The Ride2Rail project, is a European Union (EU) funded project, that aims to enhance the notion of ride-sharing by developing, testing and delivering a suite of as-a-service software components, to support planning of daily trips that will be covered partly by public transport modes and partly by private cars (ride-sharing). In our study, ride-sharing therefore complements rail and other public transport modes available in rural areas.

The process that was followed for designing the pilot study is presented and provides guidance for future similar pilot schemes. Identified challenges are linked to lessons learned to provide recommendations for the successful planning and implementation of such pilots. This research contributes to the expanding knowledge on multimodality and ride-sharing for setting up demonstration sites by outlining planning and implementation methods, and lessons learned to support involved ride-sharing stakeholders (i.e., researchers, public authorities, critical infrastructure providers, transport service providers and operators).

In the remainder of this paper, section 2 provides a summary of literature findings on ride-sharing concept with reference to planning steps and challenges. The multimodal scheme of the study is presented in section 3, including the description of the demo area and the app as well as the user engagement process. The implementation phase along with lessons learned are described and discussed in section 4 and finally, section 5 concludes the present study.

2. Background

Ride-sharing is a mobility alternative that can help accommodate the growth in urban travel demand and at the same time alleviate problems such as excessive vehicular emissions [

16]. Ride-sharing services have been found to promote sustainable transport as they reduce car utilization and minimize negative impacts related to carbon, emissions and travelling costs and congestion [

17].

2.1. Planning and Implementation

The need to shift towards public transport and multimodality can be supported by ride-sharing services which serve the first and/or last mile of a traveler’s trip. Nowadays, coordination of ride-sharing is mostly done through smart applications. Several studies have identified the following steps when planning and implementing a ride-sharing scheme [

10,

11,

18]:

Early engagement of diverse group of participants;

Technical testing of the smart application (if applicable);

Design of a survey to obtain user satisfaction after the pilot.

The Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) conducted the Carpool Pilot Project using the Avego real-time ride-sharing application [

18]. The early engagement of stakeholders, the introduction of the Avego app to early adopters, and the extensive local and/or national public relation efforts were essential steps towards planning the pilot. Regarding recruitment, the participants had to meet predefined liability and security criteria, thus an approval process was initiated by requiring several documents/certifications by potential participants. It turned out that participants were reluctant to share such information, and many dropped out of the pilot.

The European Union (EU) funded project SocialCar [

11] ran a field test in Southern Switzerland, among other cities, which also emphasized the significance of the recruitment process. During planning, the participation of a diverse group of citizens, in terms of socio-economic characteristics, was required. In order to guarantee a critical mass of offered rides, the team decided to limit the study area. An invitation was released through a press conference and a network of local partners and stakeholders were mobilized to invite their members and affiliated citizens through newsletters. Moreover, paid advertisements were executed via social media channels. During the implementation phase, participants were given clear instructions on how to use the app in a weekly basis and they were asked to complete two online surveys and participate in two focus group meetings (i.e., before and after the demo) to evaluate their attitudes and opinions. Transport vouchers were provided to them (e.g., free weekly public transport season ticket) to reward them for their participation.

Considering the technical aspects of a ride-sharing pilot, the development of the RideMyRoute application in the SocialCar project required the organization of transit data in a multi-layer temporal network to help users find optimal routes [

11]. In order to provide ride-sharing services in the journey planner, ride offers by external ride-sharing applications were also integrated; which ensured a higher offer of drivers. Regarding public transport data, most public transport companies published data using the GTFS (General Transit Feed Specification) format which was originally proposed by Google.

Despite the fact that ride-sharing uses principally ICT tools, informal ride-sharing pilots (i.e., between neighbors, or members of the same association [

19]) also provide useful insights on planning and implementation [

10,

13,

20]. The initiative of ‘Stop Covoiturage’ was launched in Val de Saône in 2013 and potential users had to register online and upon signing a commitment charter, a membership card, a car sticker for the drivers and a network map were issued [

20]. It should be noted that dedicated stops were initially defined and according to the popularity of the service new ones were added. In a similar context, the EU funded project Changing Habits for Urban Mobility Solutions (CHUMS) developed and delivered a methodology (‘the CHUMS approach’) to maximize ride-sharing demand and establish a critical mass of users. The CHUMS project applied a composite behavioral change strategy in 5 cities: Craiova (RO), Edinburgh (UK), Leuven (B), Toulouse (F) and Perugia (IT). In brief, the strategy included personalized travel plans, and the provision of a mobility jackpot lottery to attract users to shared rides. The target group was not the general public but rather restricted groups, such as work-places, large employers or universities [

10].

2.2. Challenges and Barriers

Several studies have identified social, technical, and operational challenges when planning and implementing ride-sharing schemes [

10,

11,

18,

21]. During the SR 520 pilot project, the approval process of participants (i.e., drivers and passengers) proved to be the most important obstacle and caused a large part to drop out [

18]. This resulted, as reported by several studies [

11,

12,

20], in limited recruitment of a critical mass of users. In the same context, the field-testing of SocialCar app showed that one of the main challenges was the recruitment of a significant number of participants. While locating users who are willing to test multi-modal options that include public transport and ride-sharing may be challenging, finding drivers who are eager to share their cars became more difficult [

11]. The users’ willingness to share rides was mainly attributed to psychological barriers and lack of involvement by local stakeholders [

22]. Mitropoulos, Kortsari, & Ayfantopoulou (2021) [

1] reviewed ride-sharing platforms, user factors and barriers and reported that the strongest identified barriers for ride-sharing users are mainly psychological with the most common ones being personal security, comfort, and privacy. Anthopoulos & Tzimos (2021) [

12] claimed that low ride-sharing participation is noted in Europe, and this is mainly related to high car ownership, difficulties to formulate ride-sharing schemes, lack of trust when commuting with strangers, and lack of interconnection with means of public transport in cities. Two key barriers were detected in the application of ride-sharing in Krakow, Poland - the fear for personal safety and the unwillingness of sharing rides with strangers [

23].

Regarding technical aspects, the SocialCar team who developed RideMyRoute application, reported that the most significant obstacle was the availability of data, including both the quality and quantity of the information [

11]. They also reported that the Open Street Map (OSM) cartography data proved insufficient since the automatic location of certain street addresses was often not reported right. The OSM's failure to map an address string to the correct location and automatically place an address in a different position caused the route planning algorithms to suggest incorrect routes to passengers. The complexity of route planning algorithms was reported also by Martins et al. (2021) [

8] where it is mentioned that user matching depends on spatiotemporal constraints. Regarding public transport data in SocialCar test [

11], only two out of the four cities reported that the GTFS data were of sufficient quality.

In addition to users' attitudes and technological aspects, other parameters such as the transport infrastructure could be a barrier to the adoption of ride-sharing. Potenza, Italy, introduced a ride-sharing system with a web-based match-making tool for employees and provided designated parking spaces for the riders [

13]. However, the wide availability of free parking and the fact that many people relied on private cars to take their children to school were major barriers to the uptake of the service. Mitropoulos, Kortsari, & Ayfantopoulou (2021) [

21] presented the findings of a survey conducted and report that ride-sharing combined with public transport services is more popular to drivers that live in non-urban areas due to limited accessibility to public transport.

Based on the literature’s findings, the challenges and barriers that arise during the design and implementation of ride-sharing demonstrations are summarized in

Table 1.

3. Multimodal Pilot Planning

The following sections describe the planning and implementation process of a multimodal pilot in Athens, Greece, to provide a guideline for interested stakeholders. The Ride2Rail aims to facilitate access in first/last mile of the provided transport services, to optimize multimodality and on-demand mobility, thus reducing single-occupant trips and finally to develop “smart rural transport areas”.

3.1. Demo Implementation Phases

The method that was followed consists of four distinct phases that are required for the preparation, implementation, execution and monitoring of the demonstration. More specifically the phases are:

Demo preparation: It aims to plan and provide the checklist of all technical and organizational activities needed for deploying the demonstration execution. During this phase, collaboration among local stakeholders is established.

Demo implementation: It aims to set up all technical requirements for running the demonstrations, including the integration of related software tools with required local services. Upon integration the system infrastructure and software integration will be tested.

Demo execution: The execution of the demonstration activities takes place within this phase, covering different and increasing levels of end user involvement.

Demo monitoring: It aims to define and calculate the necessary indicators and targets for allowing for cross-site comparison and assessment. The tools for monitoring are also described within this phase.

3.2. Demo Site

The city of Athens is located within the Attica Region and it is the capital and the largest city of Greece, with a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. The Region of Attica has an area of 3,808 km

2, a population of about 3,923,000 citizens and is divided administratively into 113 Municipalities, while the municipality of Athens due to its large size is subdivided into 7 districts [

24].

Attica’s public transport network consists of five different public transport modes: metro, suburban railway, tramway line, buses and trolleybuses, which are run by different operators [

25]. The Athens Metro network includes three lines with 67 stations, covering 85.3 km of railroad and transfers around 1,400,000 passengers/day [

26]. Line 1 commenced its operation in 1869, and lines 2 and 3 in 2000 with subsequent system extensions in 2004, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2013 and 2021 with a total of 39 new underground metro stations [

25,

26]. The suburban railway commenced its operation in 2004, it is 20.7 km long and connects the Athens International Airport with the city centre of Athens and the port of Piraeus [

25]. The tramway line links the centre of Athens with the port of Piraeus, the P. Faliro area (south district next to Piraeus), and the southern suburb of Voula. The tram commenced its operation in 2004 and operates in a 31.3km long network [

25,

27]. Finally, there is an extensive bus and trolley bus network, consisting of about 260 bus routes and 19 trolley bus routes, covering most of the Athens metropolitan area [

25].

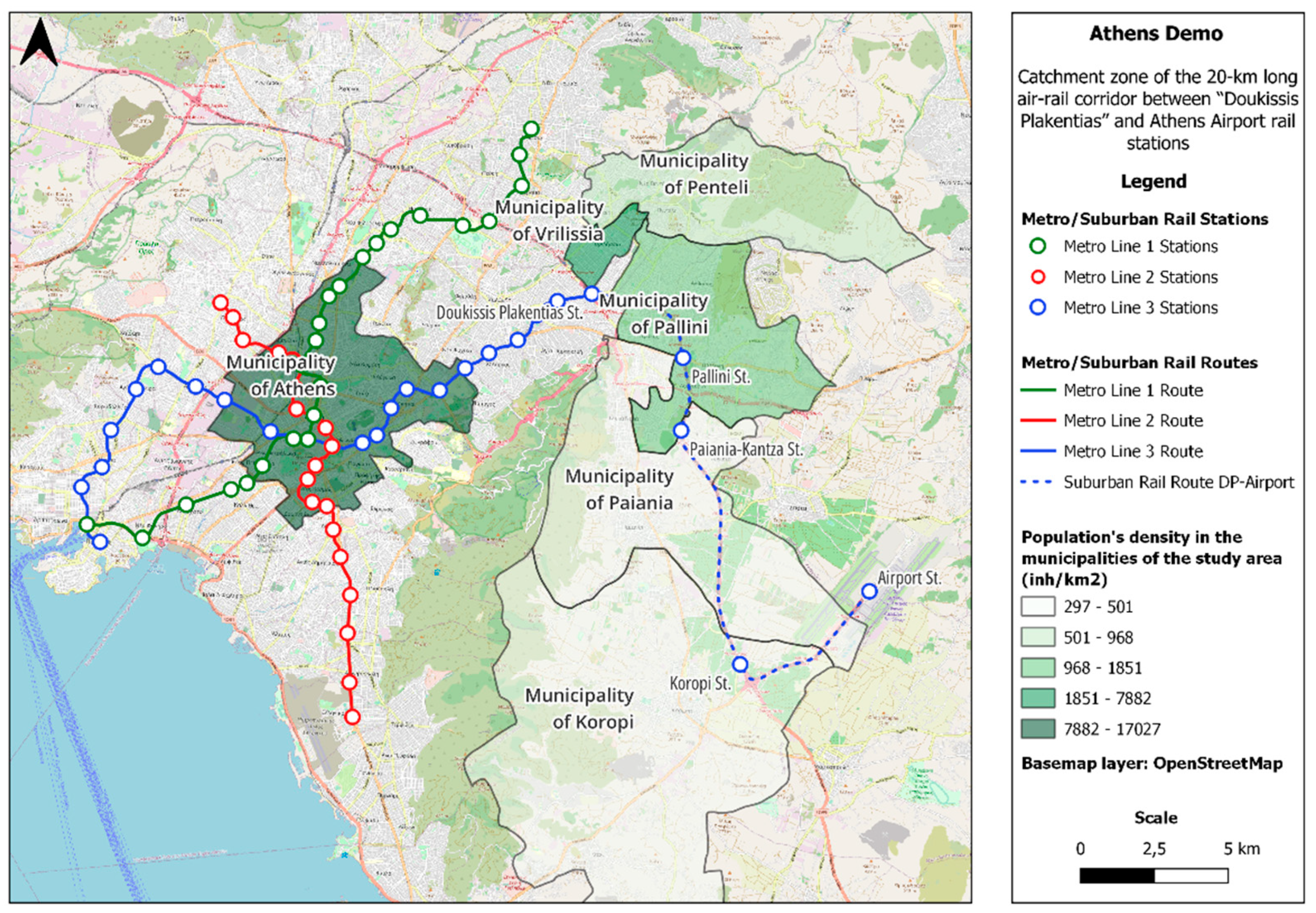

The demo area is the 20 km-long corridor between Athens Airport and the Doukissis Plakentias metro station (with Park and Ride facilities), along Attiki Odos toll motorway. This area comprises territories of five (5) municipalities with low population densities compared to the core centre of the Athens municipality (

Table 2 and

Figure 1).

The metro and suburban rail also serve the 3 intermediate stations between the Airport and D. Plakentias stations: Pallini, Kantza, Koropi. For the Athens demo, two test sites were foreseen:

Paid Park &Ride (P&R) with 500 parking spaces (PS) at D. Plakentias, which is located about 12kms from the Athens’ city center (i.e., Syntagma square);

Free municipal Park &Ride with 300 PS at the Koropi station, which is located 13 kms south of D. Plakentias station.

Both stations are equipped with P&R facilities which encourage ride-sharing for multimodal travellers.

Table 3 shows the main features of the parking facilities at both sites. The utilization rate at D. Plakentias P&R station is moderate due to parking charges. At the D. Plakentia hub, the P&R operator leases the land from the metro owner. The average parking duration is estimated to be 6-8 hours. The parking lot at Koropi station is saturated during weekday morning peak hours. Furthermore, parking spillover of about 300 passenger cars are recorded on a regular basis.

The overall goal of the demo is to enhance the connection of low-density Attica Region areas to public transport (PT) modes, and specifically to the Metro lines, through the provision of demand responsive ride-sharing services.

Travelers going to Athens (north and center) from peri-urban areas, with low frequency of PT services, often use their cars for their trips. Ride-sharing services were offered through a dedicated app, for the first and/or last leg of the trip. More specifically, the objectives of the demo are:

To examine and provide input on smart multimodal integration for the PT-ride-share mode, whereas ride-sharing works as a complement to PT (i.e., feeder) for the first/last mile part of a journey, thus increasing both car occupancies and urban rail ridership, when linking low-and high-density areas of Attica;

To serve as test sites for the platform assessment, considering new forms of shared mobility;

To evaluate innovative concepts of multimodality.

The target values of the relevant indicators of the demonstration are set and described in

Table 4. The target value of each indicator represents the scope of the demo, e.g., the number of passengers involved and using the ride-sharing solutions, the number of trips surveyed, the number of trips attracted to rail or multimodal solutions, etc. The following table reports the potential demand for the demo, as assessed by local stakeholders, and the newly assessed targets.

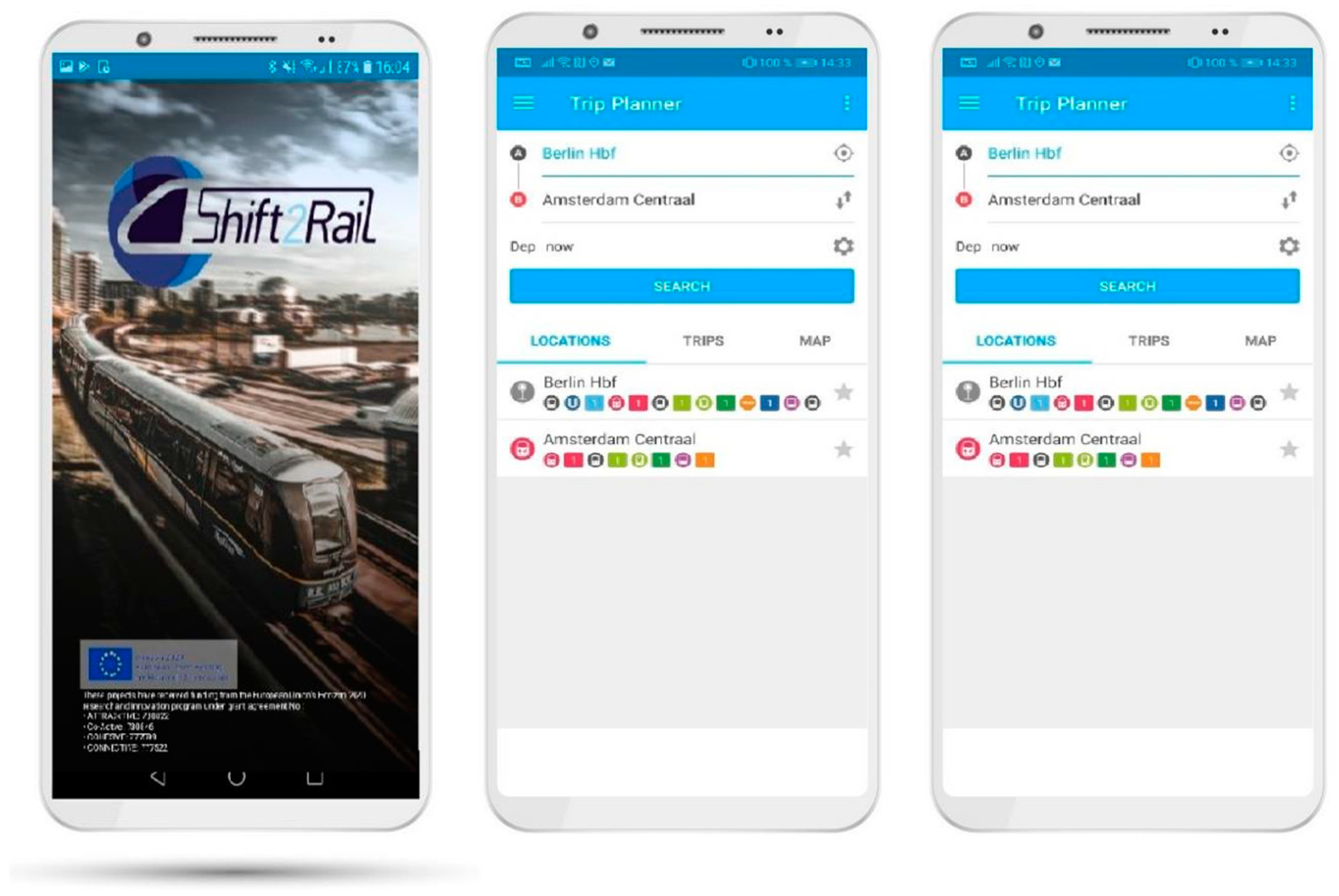

3.3. Mobile Application

The Travel Companion (TC) is an application offering intelligent multimodal mobility developed and updated by Shift2Rail IP4. The development had two main objectives:

Regarding the first objective, a module named Offer Enhancer and Ranker was developed. This module enables the characterization of the offers that appear in the user’s search so the system can classify the different options according to their preferences. This is achieved through the retrieval of information about the user’s profile and the computation of various descriptors such as quickness, comfort, environmental friendliness etc. to characterize the offers provided (Offer categorizer). Finally, a Machine Learning (ML) model that receives as input the previously mentioned features ranks the offers to be presented to users. The Agreement Ledger is a blockchain-based module to increase trust in the management of agreements between IP4 stakeholders. The Incentive Provider module determines in advance if users are eligible for travel incentives. The rewards are connected to travel offers.

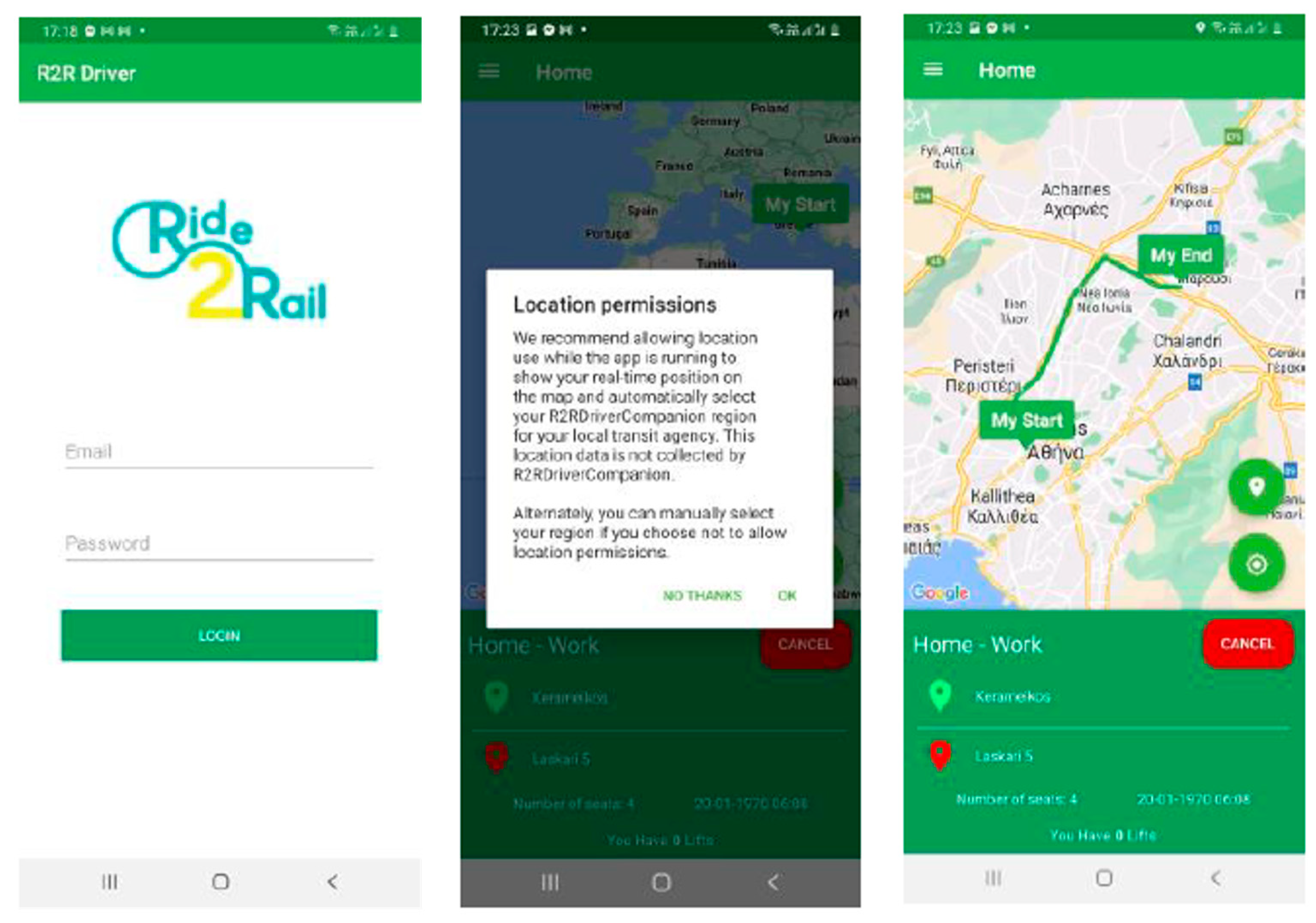

Regarding the integration of ride-sharing services, the Ride2Rail project developed a stand-alone Android application named Driver Companion (DC). Through DC drivers can create rides according to which a detailed journey plan is being designed. On the other side, TC makes this trip available to travellers that may be interested. If a traveller accepts it, then DC notifies the driver. DC provides valuable information during the journey by showing the start of each traveller as well as his/her destination.

Figure 2 illustrates snapshots from the User Interface (UI) of the DC application.

Both applications, Travel Companion and Driver Companion, were demonstrated in pilot of Athens.

3.4. User Case

During the demo period, several functionalities were tested within the “Travel Companion” and the “Driver Companion” app. More specifically the functionalities integrated in the “Travel Companion” app were: Offer Categorizer, Offer Matcher & Ranker, Agreement Ledger, Incentive provider, Crowd Based TSP. The following story telling provides the basic concept of the Athens demo-site:

Marietta is an employee living in Koropi;

She commutes daily from Koropi to Zografou;

She needs to go shopping after work;

On her return trip to home, she looks for a bus ride to reach Evangelismos metro station;

After shopping in the vicinity, rides on the metro to Doukissis Plakentias station in the late evening when bus service level is low;

Thanks to the Travel Companion, she uses a ride-sharing driver to reach home.

The Athens demo engagement strategy was twofold; on one had extensive dissemination was conducted through social media and companies’ websites, while on the other hand volunteers for the ultimate demo to test the Ride2Rail Travel Companion platform were recruited through the conduction of a Stated Preference (SP) experiment. The latter is described in section 3.5.

3.5. User Identification

Volunteers for the ultimate demo to test the Ride2Rail Travel Companion platform were recruited by conducting a Stated Preference (SP) experiment [

29]. The main aim of the survey was to investigate for the users of the metro/suburban rail system in the Attica Region, who commute from the eastern areas to Athens and vice versa, their willingness to use a ride-sharing service for their first/last mile of their trip either as drivers or as riders. For these users, at the moment the main segment of their trip is completed by metro or suburban rail, whereas the first/last segment by other means of transport or on foot.

These travellers complete a trip from home to their destination and vice versa, which usually consists of three segments:

From home to the metro/suburban rail station (Doukissis Plakentias or Koropi);

From metro/suburban rail station to another metro/suburban rail station using the metro/suburban rail or a combination of these;

From metro/suburban rail station to their final destination by any transport mode or on foot.

The reverse order applies for the return-home trip.

For the Athens-demo, the first and last segments (first/last mile) are of interest for using ride-sharing services. Trip makers with respect to first/last mile can be classified in the following categories (strata):

Travellers who use PT bus;

Travellers who drive alone (solo drivers) to/from any of the two stations;

Travellers who drive with one or more co-riders to/from any of the two stations;

Travellers who take taxi to/from any of the two stations;

Travellers who are riders – not drivers- of another car travelling to/from any of the two stations.

The first four categories may expect benefits in terms either of travel time savings, travel cost reductions, comfort and convenience or a combination of these. The last category is not of interest in the specific survey given that these specific travellers do not benefit from ride-sharing either as drivers or as riders. The completion of the survey requires 15 or even 20 min.

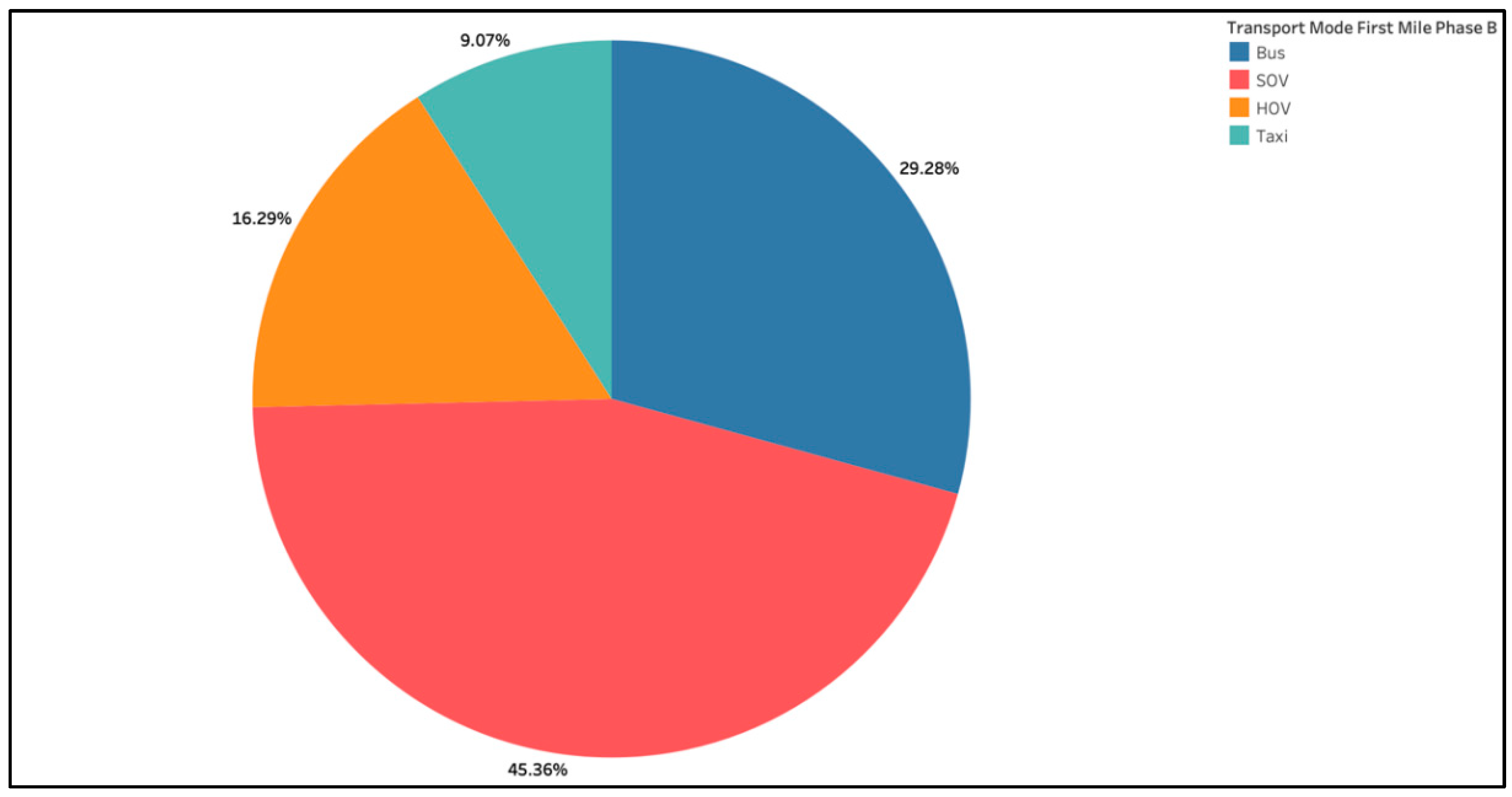

The initial questionnaire sample was 5,399 respondents; 64.5% of the interviews were conducted at D. Plakentias station while the remaining 35.5% at Koropi station. More than 95% of the questionnaires were conducted on the metro/suburban railway platforms of both stations.

More than 70% of the respondents hold a driving license, while almost 60% of the respondents own a private passenger vehicle. Survey participants were asked about their trip purpose, and more than half (51%) are commuters, approximately 25% travel for personal reasons and 3% travel for business and other purposes.

For the majority of the respondents (84.6%) the trip’s origin is their home, and for 54% of the respondents the destination is their work. Regarding the transport mode used during the first mile of their trips, almost 62% were made with a private vehicle, 45.4% as a driver with no passengers (SOV) and 16.3% as a driver with passengers (HOV). The bus was used by 29.3% of the sample and 9.1% of the respondents used a taxi during the first mile of their trip (

Figure 3).

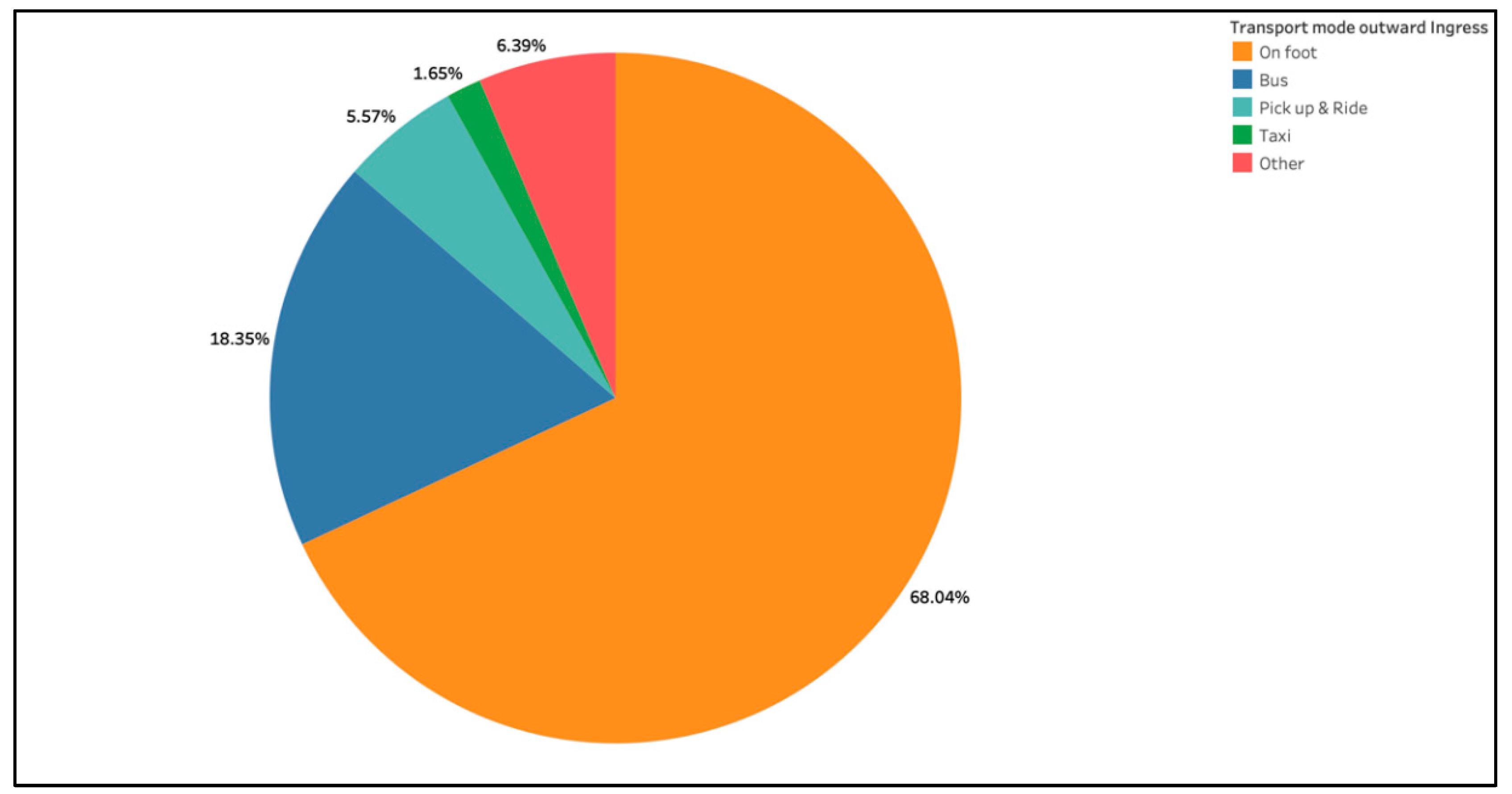

Regarding the last mile of their trip, 68% of the respondents continued their trip on foot while 18.4% continued by bus (

Figure 4).

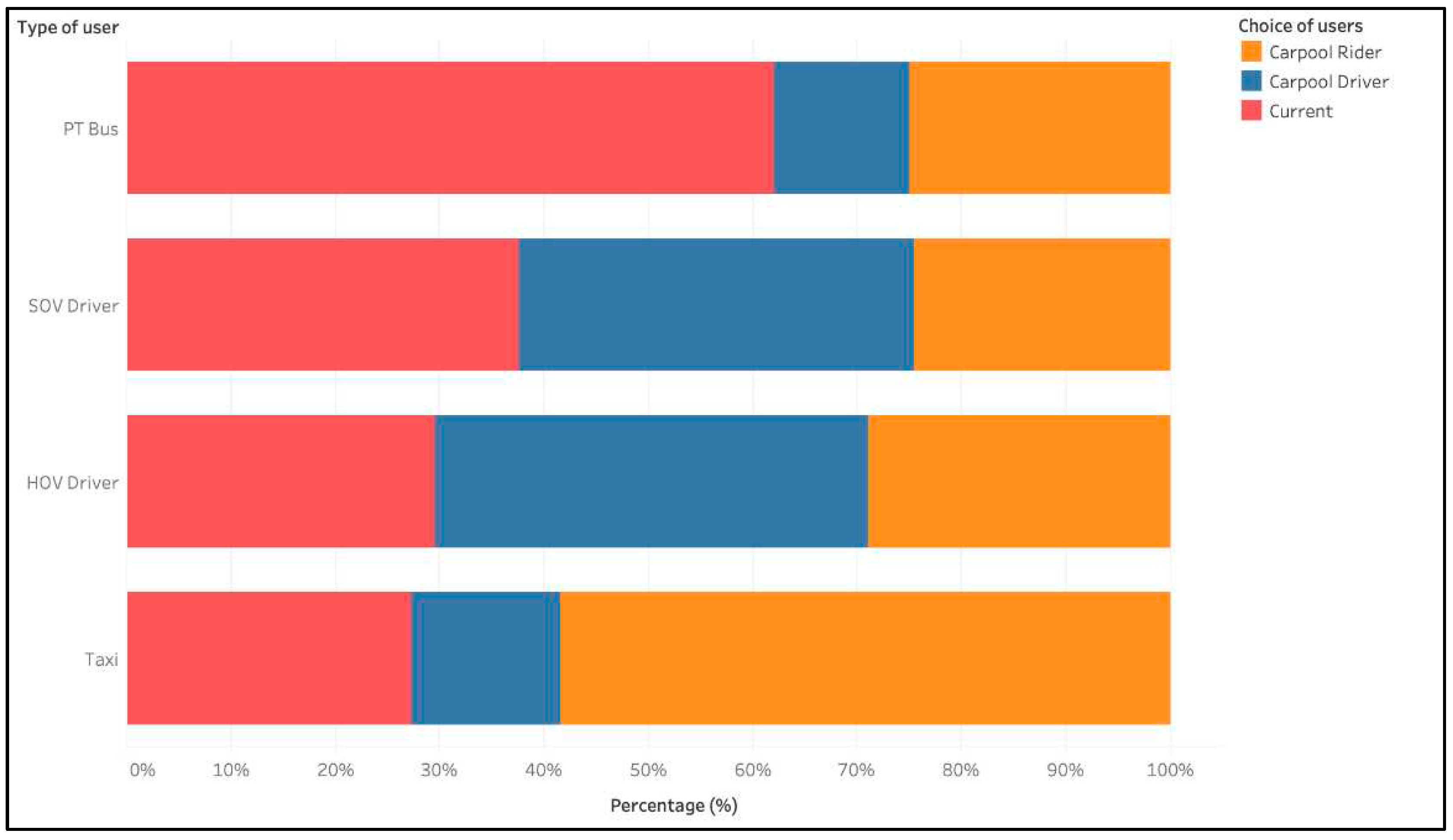

To investigate the willingness of respondents to use ride-sharing as drivers or passengers, a series of game cards with different attribute levels were presented to them. More than 57% of the sample selected ride-sharing either as a driver or a rider.

Figure 5 presents the mode choice per user type according to the current used transport mode for the first mile of their trip. Current bus users prefer mostly to continue using the bus rather than shifting to a ride-sharing option. On the contrary, taxi users prefer mostly to shift to ride-sharing as riders, while SOV or HOV drivers prefer ride-sharing as drivers.

By applying the survey results it becomes possible to estimate the number of users who are willing to change their current travel mode to another mode, i.e., becoming ride-sharing drivers or riders for their trip segment home to metro/suburban rail station.

3.6. Incentives and Participation

In the framework of the SP survey, two distinctive phases took place; during the 1st phase the screening of questionnaires at the stations took place (field survey) using Computer Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI) technique. Overall, 5,400 persons were approached with 2,000 of them being found eligible to participate in the survey. During the 2nd phase, the full SP survey was completed by the respondents at home or at work, using the Computer Assisted Web Interview (CAWI) technique. All in all, 1250 agreed to proceed and 414 completed phase 2. Following, 151 respondents of those who completed phase 2, accepted to participate in the Athens Demo by giving their email addresses. Finally, 151 invitations were sent by email to them on July 18th.

Following the SP experiment and after having sent the email, more than 100 users stated that they would be willing to participate at the Athens demo; the final number of participants however was significantly lower, probably due to the unfavourable period of the demo execution, which coincided with people’s summer vacation (July and August are considered a vacation period in Greece).

At this point it should be noted that, apart from the dissemination strategy and the SP survey, the Athens pilot partners provided specific incentives, in order to persuade identified users to participate in the Athens demo [

30]. More specifically, ride-sharing passengers were awarded a voucher of 30€ for groceries (supermarket), while drivers were awarded a 50€ voucher for gasoline. All incentives were provided by specific companies in Athens, where users could redeem them after the completion of the demo. The final figures describing the participants at the Athens demo are as follows:

Number of registered users (travelers): 19;

Number of registered users (drivers): 9;

Number of users that completed the survey: 17.

4. Demo Planning and Implementation

During the planning and implementation of the demo, several challenges were faced. First a low number of trips makers was recorded, during the completion of the SP, as respondents are used to travel by their private vehicle together with other riders or by using a Taxi. Regarding the execution of the survey, the most difficult issue was related to respondents’ consent. The used survey platform did not provide a related feature and clicking on a box was not approved as adequate by the project partners’ Data Protection Officer. To overcome this issue, hard copy statements were also developed and distributed to respondents.

The main challenges that were faced during the execution of the demo and proposed directions to address them are analyzed and presented in the following sections.

4.1. Planning of the Demo

The ride-sharing demonstration in Athens was scheduled to last two working weeks, from the 11th of July until the 22nd. However, due to various technical issues that arose during the testing week (i.e., 4-8 of July), the project partners decided to postpone it for a week. During this week all efforts were placed on the improvement of the application and on the overcoming of identified issues. As a result, the demo lasted 1 week, from 18th to 22nd July 2022. The month of July was selected in order to include, apart from local commuters, also tourists visiting Athens during the specific time period. This choice, however, had a negative side effect, since in July ambient conditions due to high temperatures are not favorable for staying (for the case of tourists) and traveling by public transport in Athens. Moreover, the postponement of the demo made the circumstances even less favorable for the participation of local users. A significant decrease in the number of actual demo participants compared to the number of participants that agreed during the SP to participate in the demo was recorded. Therefore, one of the main lessons learned is that it is of imperative importance to plan well in advance the time period during which the actual demo will take place and inform potential participants. Implementing a demo during the summer, while high temperatures are recorded and during holiday seasons, should be avoided at all costs.

Additionally, the time frame that was foreseen for the technical testing of the application was positioned one week before the actual demo. This proved to be insufficient, in terms of working days, and led to the demo being postponed and shortened by one week. The technical partners along with the demo leaders strenuously worked on optimizing the application in a very short period of time to prepare it for the demonstration. Thus, the technical testing should be scheduled to initiate at least 3 weeks before the demo and last for at least 2 weeks.

4.2. Allocation of Responsibilities

During the testing of the application, one of the issues that arose was the fact that responsibilities were not as clear as they should have been due to the high number of involved stakeholders. In several cases, more than one person from each company/organization was involved and this sometimes led to misunderstandings as to who was responsible for resolving each issue. For this reason, it is significant to allocate well in advance responsible partners for each role, and at least 1-2 persons per partner as a contact point.

4.3. Translation of the Travel Companion (TC)

During the preparation of the Travel Companion one of the issues that was extensively discussed was the translation of the application into the local language. In the case of Athens, the local partners decided that it would be better to translate the app in Greek, given that some of the user groups targeted may not be familiar to the English language. Some of the main conclusions and lessons learnt through this process are:

The demo leader needs to decide which parts of the app should be translated. It was decided that presenting a partially translated application would be confusing;

Due to lack of context, since translations took place by word rather within the application, translation does not always reflect the actual word meaning;

Location names would be useful to be available in the local language.

4.4. Travel Companion (TC) Download

The Travel Companion was developed into two different modules: the Driver Companion and the Travel Companion. In case a user wished to participate as both a driver (offering rides) and as a traveler (being a passenger), he or she needed to download and install these two different applications. This procedure presupposed that the user had quite a high technological knowledge when it comes to installing and using apps. This, however, is not the case for the average user which was targeted by the project demo.

Moreover, a separate user guide and Terms and Conditions were offered to drivers and travelers. It would be more efficient and user friendly if there was only one download requested, one user guide to go through and one T&C document to agree with.

4.5. Operational and Technical Issues

The main operational and/or technical challenges that were noted and should be resolved in future endeavors are:

The addresses and POIs from other countries (also participating in the project and demos) need to either be erased or hidden during the time period of the demo in a particular city. It was confusing for users to identify an address through places from other countries;

Using the available map was the easiest way to identify an origin or destination; related also to the above-mentioned challenge;

Loading a ride request or a ride offer required more than the average waiting time for a mobile user;

Ride offers from drivers were sometimes not matched to any traveler;

The technical terminology used in the guidelines provided made them unfriendly to daily users.

4.6. Survey

During the execution of the demo, the users were asked to complete a survey in order to rate their overall satisfaction with the Travel Companion (TC). The survey was sent twice during the demo week and once at the end of it, reminding the users to participate.

After completing the survey, the users were asked to send an email with a code that was provided to them at the end of the survey to receive their gift (supermarket or gas station voucher). The format of the provided code was misleading thus participants did not send it back to request their prize.

The main conclusion drawn from this procedure was that the survey should be automatically sent to the user immediately after the use of the app. It was observed that once the email was sent, 3-5 users would enter the survey and complete it on the spot. This proves that users tend to complete the survey when it is sent to them, thus if the survey had been sent to participants at the end of the trip, the number of completed surveys would have been much higher.

4.7. Lessons Learned

The discussion of the lessons learned during the planning and implementation of the ride-sharing service is summarized in the list that follows.

Lack of awareness: One of the primary barriers to ride-sharing demonstrations is the lack of awareness [

31,

32] and understanding among potential participants. More specifically, participants may not be familiar with the concept of ride-sharing or the benefits that it offers. It requires effective marketing and communication strategies to raise awareness and educate the public about the advantages of ride-sharing. In this context, the CHUMS project included in its measures an awareness-raising event called the Carpool Week [

10]. Finally, the duration of the incentives after the completion of the demo should be considered to persuade participants to use the mobility service for longer (if the duration is extended beyond the demo period).

Limited participation: Ride-sharing demonstrations require a critical mass of participants, both drivers and passengers, to be effective [

11,

18]. If the number of people willing to share rides is limited, it becomes challenging to impossible to form viable ride-sharing groups and develop a successful and sustainable service. Achieving a sufficient number of participants can be difficult, especially in areas with low population density or where public transport options are readily available. For example, a corridor strategy was adopted in Carpool Pilot Project [

18] to build towards critical mass according to a previous Avego study. Due to the large number of participants that dropped out, restricting the service on only two routes made sense in the context of focused marketing, approval and adoption activities to achieve critical mass and to facilitate a useful pool of “approved” participants.

Geographic constraints: Ride-sharing demonstrations may face geographical challenges as in areas with dispersed populations or inadequate road infrastructure, it can be difficult to establish convenient ride-sharing routes. Commuters may need to travel long distances to meet up with other participants, wait in isolated-not designated areas, thus reducing the feasibility and attractiveness of ride-sharing.

Scheduling and flexibility: Coordinating schedules among participants can be a significant challenge. In real life though, people have different work schedules, varying commitments, and unexpected changes in their daily routines. Aligning schedules and ensuring flexibility can be difficult, leading to potential difficulties in organizing and maintaining ride-sharing arrangements in advance. Stiglic et al. (2016) [

33] studied the impact on the matching rate of different flexibility scenarios in conjunction with the number of announced trips in dynamic ride sharing systems. Results showed that low system-wide matching flexibility of 5 min significantly limits the ability of the system to establish matches. On the other hand, a higher matching flexibility can make up for a lack of density. For example, a matching flexibility of 30 min results in matching rates of 55.9% on average at the lowest density. A solution to this may be the establishment of ride-sharing services among limited communities (e.g., companies, universities) as implemented in CHUMS and various CIVITAS initiatives [

10,

13].

Trust and compatibility: Successful ride-sharing depends on establishing trust and compatibility among participants [

1,

21,

30,

34]. People need to feel comfortable with their fellow passengers, especially when it comes to safety, reliability, and adhering to agreed-upon rules. Building trust within a ride-sharing group or community requires time that is not available within the framework of a ride-sharing demonstration., If participants do not feel compatible or comfortable, they may hinder the success of the ride-sharing demonstration or service. To address this issue, some ride-sharing schemes [

10,

13] defined as target groups limited communities such as big companies or universities.

Incentives and disincentives: The availability and effectiveness of incentives plays a crucial role in promoting ride-sharing as indicated in previous ride-sharing studies [

18,

21,

35,

36,

37]. Lack of appropriate incentives, such as reduced tolls, dedicated ride-sharing lanes, or financial, may discourage potential participants from engaging in such demonstrations. Similarly, disincentives, such as limited parking spaces or inconvenient pick-up and drop-off locations, can deter individuals from choosing ride-sharing as a comfortable transport option.

Regulatory and legal challenges: Ride-sharing demonstrations may face regulatory and legal barriers. Local transport regulations, insurance requirements, liability concerns, and privacy issues may pose challenges to the implementation of ride-sharing initiatives. According to Anthopoulos and Tzimos (2021) [

12], the lack of interconnection with means of public transport in cities has been reported as a significant challenge for the implementation of ride-sharing schemes. Overcoming these obstacles requires collaboration between relevant authorities, policy-makers, and stakeholders.

Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach involving public awareness campaigns, supportive policies, infrastructure development, effective scheduling tools, and incentives to encourage participation. It also requires ongoing evaluation and adaptation of strategies to ensure the long-term success of ride-sharing demonstrations.

5. Conclusions

The overall execution of the demo proved that the ride-sharing concept is in general considered a viable solution, both as a stand-alone mode and as part of a multimodal trip, for transport in urban and peri-urban areas. However, several projects and studies confirm that when planning and implementing a ride-sharing scheme a variety of challenges need to be addressed including, the engagement of a critical mass of users, the support of digital services and participants’ feedback.

In this study, the planning and implementation process together with main challenges and lessons learnt related to the ride-sharing/public transport demo in Athens were outlined. These are summarized below:

Efficient planning of the demo is of imperative importance for its success. Holiday seasons should be avoided, while sufficient time should be foreseen for testing the application, before making it available to actual users;

Clear responsibilities should be allocated to involved parties throughout all phases: planning, testing, demo execution;

Having the application translated into the local language is an added value and a facilitator of the demo’s success. This however is true only in the case of a high quality, ideally professional, translation;

Technical testing of the application should be carried out enough time before the pilot (e.g., at least 3 weeks) and last a sufficient period of time (e.g., at least 2 weeks);

The ride-sharing app should be available in only one download, accompanied with one user guide and one document of Terms and Conditions to which the user needs to agree;

No POIs from other countries should be included in the app, shorter loading time, efficient matching between driver and traveler and a user-friendly guide are a few of the operational and technical issues that need to be resolved;

A short survey which is sent immediately after the user has tested the app ensures high participation in the evaluation and provision of high-quality input.

Except for demo challenges, the present study also presents additional limitations such as the rather low number of participants. It should be further noted that travel protection measures against COVID-19 were active in Athens during the demo period, which posed major limitations to demo pilot partners to recruit travelers (i.e., convince travelers to participate to the trials and conduct trips and specially to persuade drivers to share their private vehicles with strangers). This fact contributed further to negative percentage change in terms of commuters.

Although the duration of the demo was not long, the findings regarding challenges for implementing ride-sharing to public transport did not divert from the literature findings, which reveals that lessons learned, and the planning process may be transferable to other locations.

To conclude, successful stakeholder engagement in the early stages results in a higher acceptance for multimodal traveling. Eventually, stakeholder engagement should evolve towards more structured and permanent collaboration forms that enable strategic functions, as well as evaluation and oversight, which should lead to an achievement of desired mobility patterns and environmental objectives [

15]. Future research steps should focus towards developing a robust technological application that considers local participants’ characteristics and build business models that will enable the collaboration of public transport and ride-sharing providers to develop a reliable and sustainable multimodal system.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, A.K.; methodology, L.M. and A.K.; formal analysis, L.M., A.K., and E.M; resources, L.M., A.K., and A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M., A.K., and E.A; writing—review and editing, L.M. and G.A.; visualization, L.M.; supervision, A.K. and G.A.; funding acquisition, G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 881825.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mitropoulos, L.; Kortsari, A.; Ayfantopoulou, G. A Systematic Literature Review of Ride-Sharing Platforms, User Factors and Barriers. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code of Virginia Code - Chapter 14. Ridesharing. Available online: https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacodefull/title46.2/chapter14/ (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Seyedabrishami, S.; Mamdoohi, A.; Barzegar, A.; Hasanpour, S. Impact of Carpooling on Fuel Saving in Urban Transportation: Case Study of Tehran. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2012, 54, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, Susan; Cohen, Adam; Bayen, Alexandre The Societal Value of Carpooling: The Environmental and Economic Value of Sharing a Ride. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Noussan, M.; Jarre, M. Assessing Commuting Energy and Emissions Savings through Remote Working and Carpooling: Lessons from an Italian Region. Energies 2021, 14, 7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Bucher, D.; Kissling, J.; Weibel, R.; Raubal, M. Multimodal Route Planning with Public Transport and Carpooling. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2018, 20, 3513–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.; Nelson, J.D.; Cottrill, C.D. MaaS for the Suburban Market: Incorporating Carpooling in the Mix. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2020, 131, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.D.C.; De La Torre, R.; Corlu, C.G.; Juan, A.A.; Masmoudi, M.A. Optimizing Ride-Sharing Operations in Smart Sustainable Cities: Challenges and the Need for Agile Algorithms. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2021, 153, 107080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Hwang, K.; Li, D. Intelligent Carpool Routing for Urban Ridesharing by Mining GPS Trajectories. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2014, 15, 2286–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, D.; Van Den Bergh, G. D4.2 Impacts of CHUMS Measures; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Derboni, M.; Rizzoli, A.-E.; Montemanni, R.; Jamal, J.; Kovacs, N.; Cellina, F. Challenges and Opportunities in Deploying a Mobility Platform Integrating Public Transport and Car-Pooling Services. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anthopoulos, L.G.; Tzimos, D.N. Carpooling Platforms as Smart City Projects: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIVITAS Sustainable Mobility Highlights 2002-2012.

- Lygnerud, K.; Nilsson, A. Business Model Components to Consider for Ridesharing Schemes in Rural Areas – Results from Four Swedish Pilot Projects. Research in Transportation Business & Management 2021, 40, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitropoulos, L.; Kortsari, A.; Mizaras, V.; Ayfantopoulou, G. Mobility as a Service (MaaS) Planning and Implementation: Challenges and Lessons Learned. Future Transportation 2023, 3, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, N.; Nam, D.; Yu, J.; Jayakrishnan, R. Promoting Peer-to-Peer Ridesharing Services as Transit System Feeders. Transportation Research Record 2017, 2650, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Threats from Car Traffic to the Quality of Urban Life: Problems, Causes, and Solutions; Gärling, T., Steg, L., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-08-048144-9. [Google Scholar]

- AVEGO SR 520 Real-Time Ridesharing Pilot Summary Report. 2011; 33.

- Pigalle, E.; Aguiléra, A. Ridesharing in All Its Forms – Comparing the Characteristics of Three Ridesharing Practices in France. Journal of Urban Mobility 2023, 3, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reducing Commuter Traffic in Val de Saône with Carpooling (France) | Eltis. Available online: https://www.eltis.org/discover/case-studies/reducing-commuter-traffic-val-de-saone-carpooling-france (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Mitropoulos, L.; Kortsari, A.; Ayfantopoulou, G. Factors Affecting Drivers to Participate in a Carpooling to Public Transport Service. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechita, E.; Crişan, G.-C.; Obreja, S.-M.; Damian, C.-S. Intelligent Carpooling System: A Case Study for Bacău Metropolitan Area. In New Approaches in Intelligent Control; Nakamatsu, K., Kountchev, R., Eds.; Intelligent Systems Reference Library; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; Volume 107, pp. 43–72. ISBN 978-3-319-32166-0. [Google Scholar]

- Parezanović, T.; Petrović, M.; Bojković, N. Carpooling as a Measure for Achieving Sustainable Urban Mobility: European Good Practice Examples. Machines. Technologies. Materials. 2015, 9, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Economopoulou, M.A.; Economopoulou, A.A.; Economopoulos, A.P. A Methodology for Optimal MSW Management, with an Application in the Waste Transportation of Attica Region, Greece. Waste Management 2013, 33, 2177–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spyropoulou, I. Impact of Public Transport Strikes on the Road Network: The Case of Athens. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2020, 132, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkadoula, M.; Giannakopoulou, K.; Goumas, G.; Tsarmpopoulou, M.; Leoutsakos, G.; Deloukas, A.; Apostolopoulos, I.; Kiriazidis, D. Energy Audit in Athens Metro Stations for Identifying Energy Consumption Profiles of Stationary Loads. International Journal of Sustainable Energy 2022, 41, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiko Metro, S.A. Official Website. Available online: https://www.emetro.gr/?lang=en (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Official Website. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/home/ (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Attiko Metro, S.A. TSA416/22 Final Report, “Revealed and Stated Preference Survey for Willingness to Accept Carpooling”. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Asimakopoulou, M.N.; Mitropoulos, L.; Milioti, C. Exploring Factors Affecting Ridesharing Users in Academic Institutes in the Region of Attica, Greece. Transportation Planning and Technology 2022, 45, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaube, V.; Kavanaugh, A.; Pérez-Quiñones, M. Leveraging Social Networks to Embed Trust in Rideshare Programs.; January 1 2010. 8.

- Malichová, E.; Pourhashem, G.; Kováčiková, T.; Hudák, M. Users’ Perception of Value of Travel Time and Value of Ridesharing Impacts on Europeans’ Ridesharing Participation Intention: A Case Study Based on MoTiV European-Wide Mobility and Behavioral Pattern Dataset. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglic, M.; Agatz, N.; Savelsbergh, M.; Gradisar, M. Making Dynamic Ride-Sharing Work: The Impact of Driver and Rider Flexibility. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2016, 91, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, S.; Buchmann, M. Empty Seats Traveling : Next-Generation Ridesharing and Its Potential to Mitigate Traffic- and Emission Problems in the 21st Century. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, L.E.; Maier, R.; Friman, M. Why Do They Ride with Others? Meta-Analysis of Factors Influencing Travelers to Carpool. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Cohen, A. Shared Ride Services in North America: Definitions, Impacts, and the Future of Pooling. Transport Reviews 2019, 39, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homem de Almeida Correia, G.; de Abreu e Silva, J.; Viegas, J. Using Latent Attitudinal Variables Estimated through a Structural Equations Model for Understanding Carpooling Propensity. Transportation Planning and Technology 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloukas, A.; Georgiadis, G.; Papaioannou, P. Shared Mobility and Last-Mile Connectivity to Metro Public Transport: Survey Design Aspects for Determining Willingness for Intermodal Ridesharing in Athens. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2020; Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).