Submitted:

18 March 2025

Posted:

19 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Variable Selection

| Attributes | Source |

| Suitable vehicle types for ADRTs | (37, 52, 59, 60) |

| Suitable service offerings for ADRTs | (6, 8, 16, 30, 61) |

| Suitable trip purposes for ADRTs | (6, 37, 38, 62-64) |

| Suitable demographic groups for ADRTs | (3, 6, 65) |

| Suitable land use for ADRTs | (65-67) |

| Impacts on passenger performance from ADRTs | (6, 18, 37, 40, 68) |

| Social impacts from ADRTs | (3, 69, 70) |

| Environmental impacts from ADRTs | (29, 36, 71, 72) |

2.2. Survey Design

2.3. Study Setting

2.4. Participant Recruitment

2.5. Analytical Approach

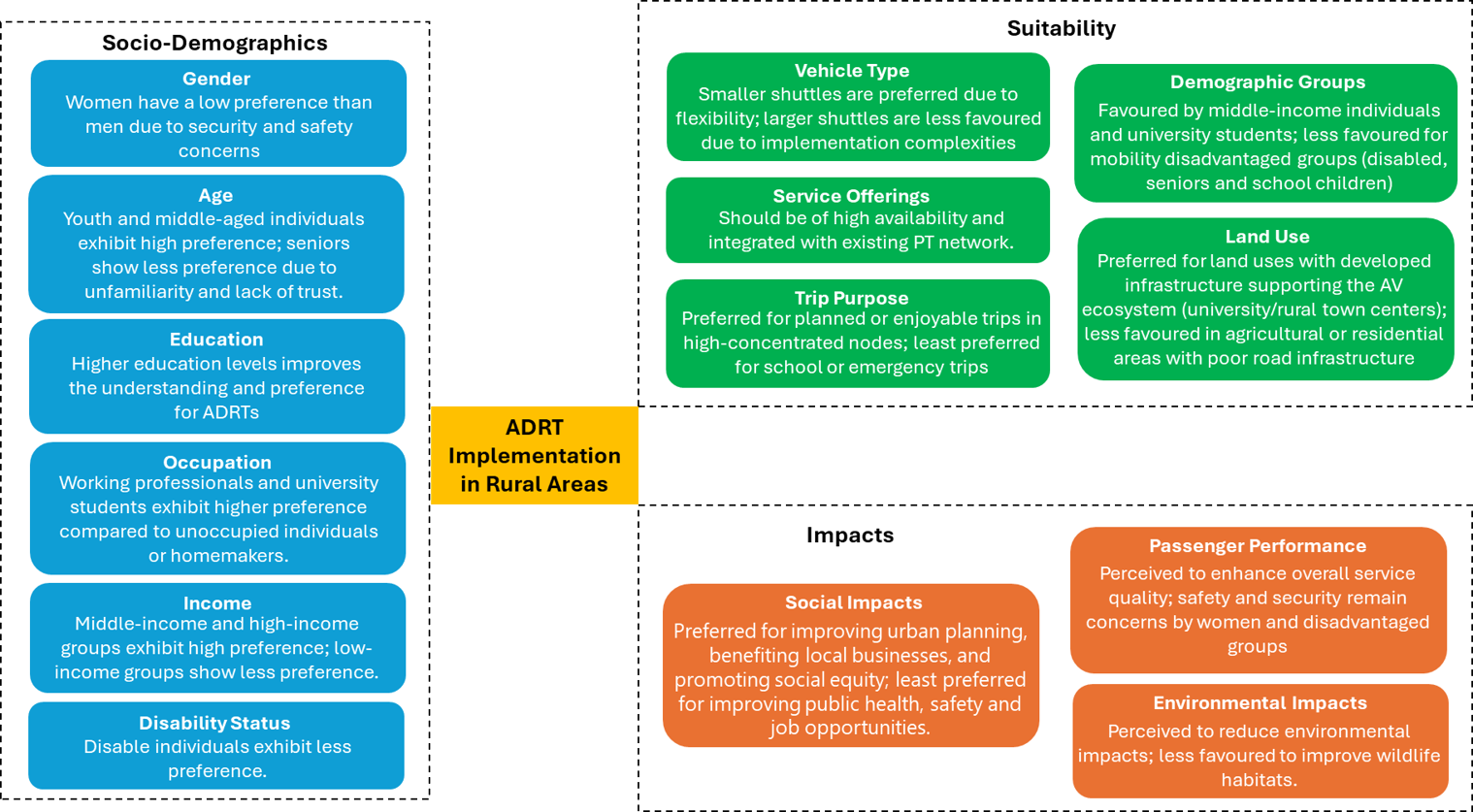

3. Results and Discussion

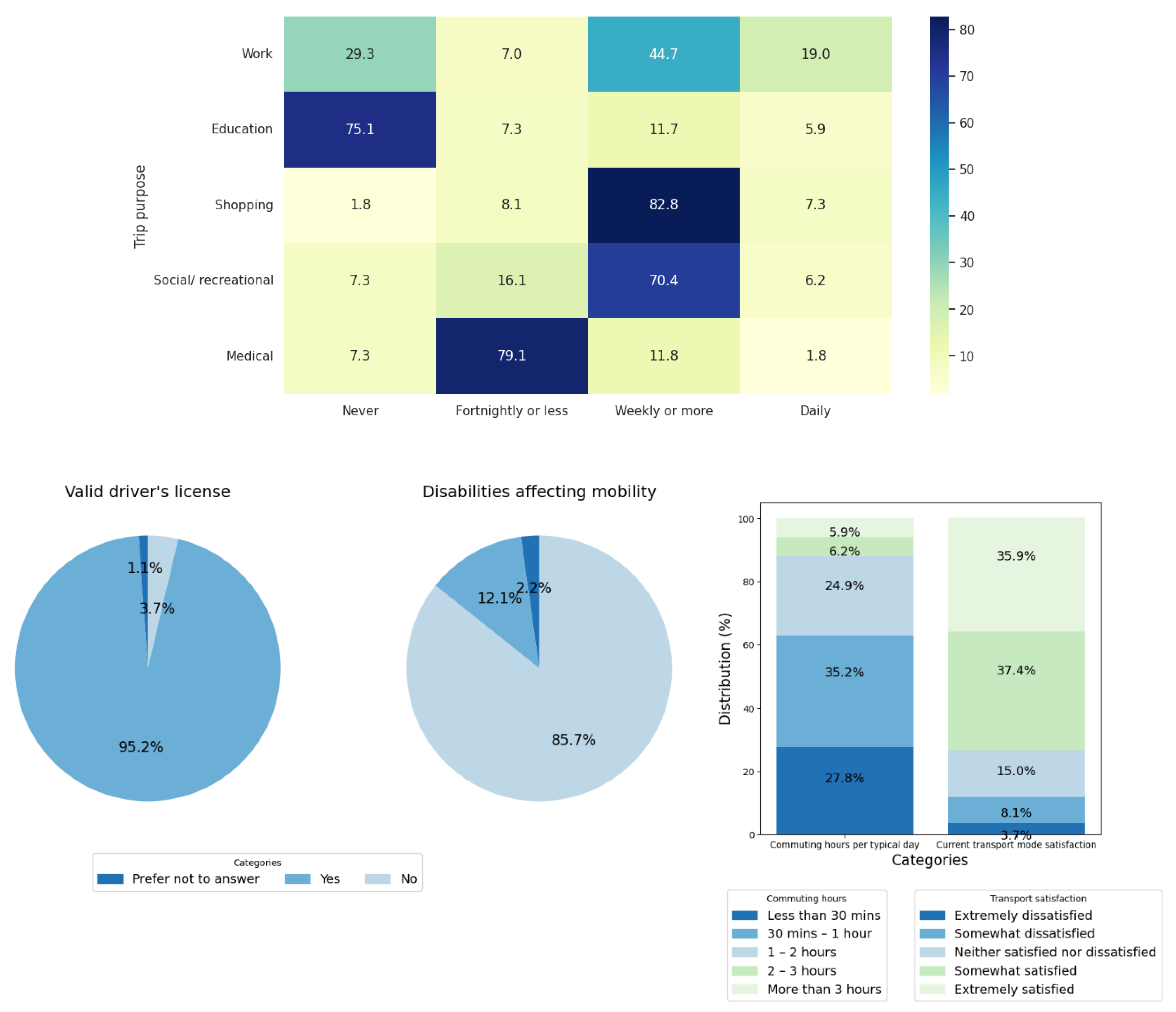

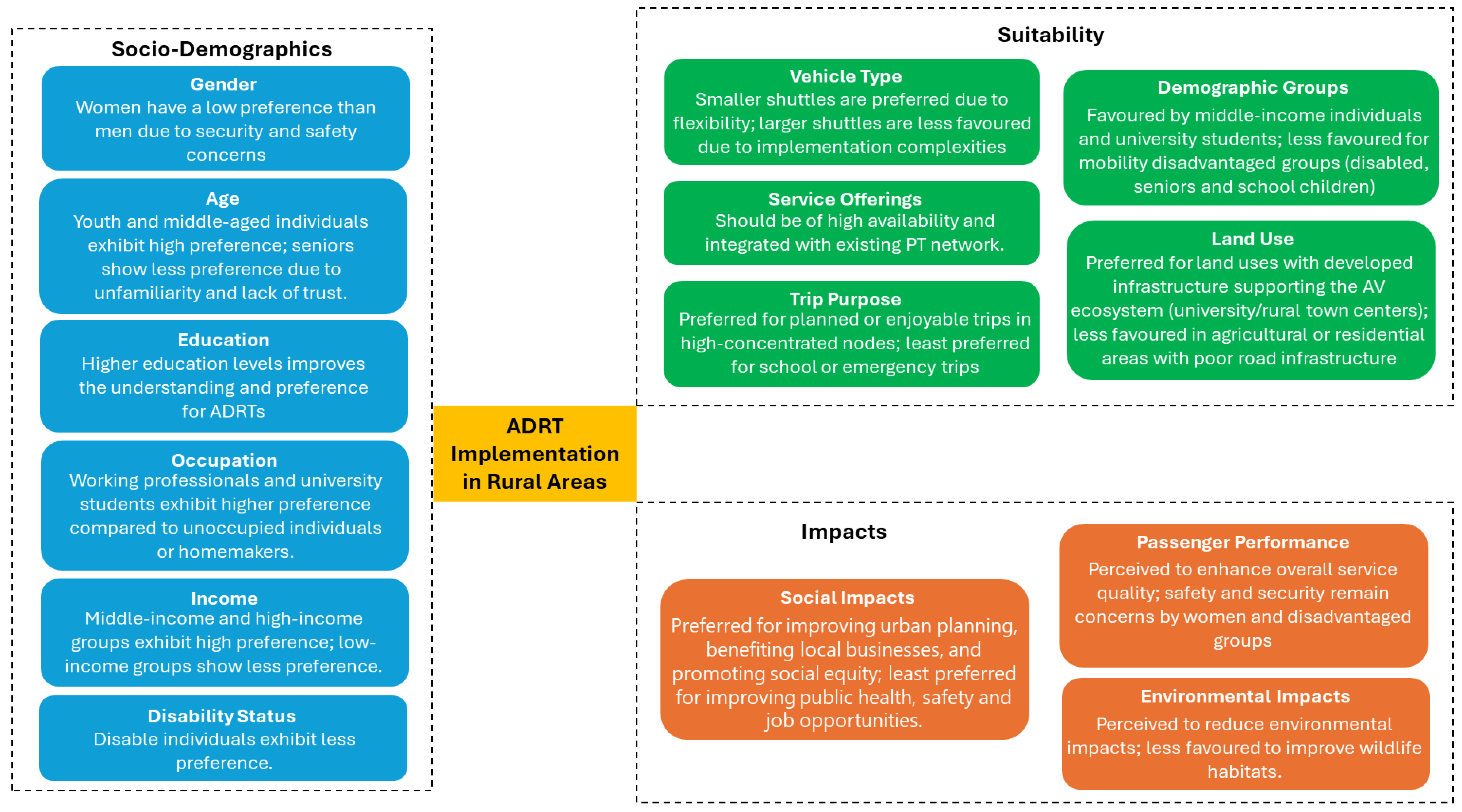

3.1. Socio-Demographic Profile of Respondents

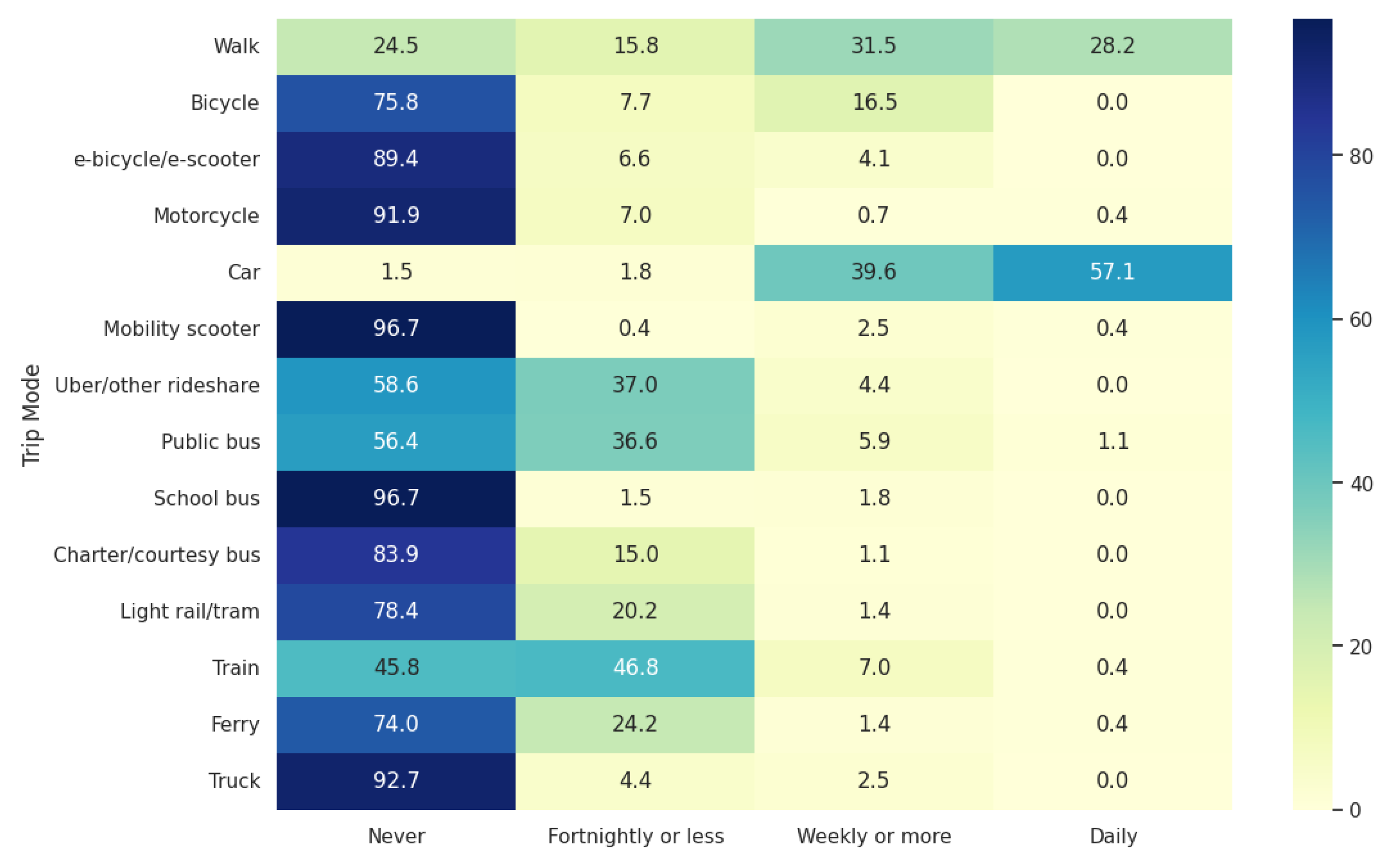

3.2. Current Travel Patterns of Respondents

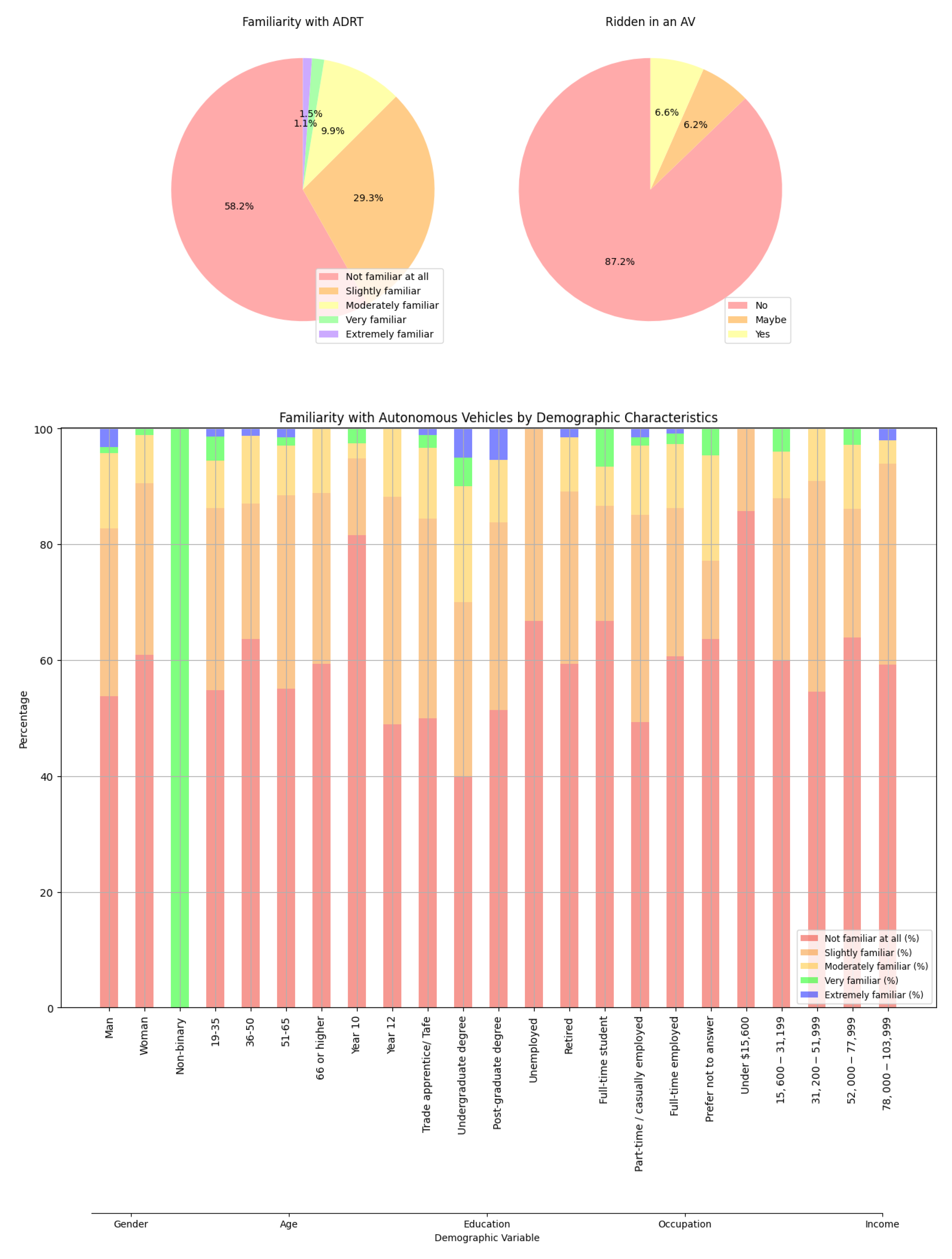

3.3. General Perception of ADRTs

3.4. Perceived Suitability of ADRTs

3.4.1. Vehicle Type

3.4.2. Service Offerings

3.4.3. Trip Purpose

3.4.4. Demographic Groups

3.4.5. Land Use

3.5. Perceived Impacts of ADRTs

3.5.1. Passenger Performance

3.5.2. Social Impacts

3.5.3. Environmental Impacts

3.6. Heterogenity in Perceptions of Suitability and Impacts of ADRTs

3.7. Effect of Demographics on Perceptions

| Response Variable | Model Sig. | Predictor Variable | Std. Error | Wald | Wald Sig. | 95% CI | ||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||||

| Suitability of ADRTs (University students) |

0.012 | Age (19-35) | 0.546 | 3.815 | 0.050 | -0.004 | 2.137 | |

| Age (36-50) | 0.547 | 7.204 | 0.007 | 0.396 | 2.538 | |||

| Age (51-65) | 0.475 | 5.444 | 0.020 | 0.1777 | 2.041 | |||

| Occupation (Retired) | 0.462 | 5.639 | 0.018 | 0.192 | 2.004 | |||

| Education level (Year 10) |

0.457 | 5.913 | 0.015 | -2.006 | -0.216 | |||

| Education level (Trade apprentice/ Tafe) |

0.387 | 10.014 | 0.002 | -1.981 | -0.466 | |||

| Disability (Yes) |

0.376 | 5.091 | 0.024 | 0.112 | 1.587 | |||

| Impacts of ADRTs (Positive influence on urban planning and development) |

0.017 | Age (36-50) | 0.545 | 4.663 | 0.031 | 0.109 | 2.243 | |

| Education level (Year 10) |

0.459 | 8.421 | 0.004 | -2.230 | -0.432 | |||

| Education level (Trade apprentice/ Tafe) |

0.384 | 5.468 | 0.019 | -1.653 | -0.145 | |||

| Disability (Yes) | 0.381 | 8.640 | 0.003 | 0.373 | 1.865 | |||

| Impacts of ADRTs (Improve public health and well-being) |

0.009 | Age (19-35) | 0.549 | 4.913 | 0.027 | 0.141 | 2.292 | |

| Age (36-50) | 0.548 | 7.253 | 0.007 | 0.402 | 2.548 | |||

| Education level (Year 10) |

0.456 | 5.520 | 0.019 | -1.964 | -0.178 | |||

| Education level (Trade apprentice/ Tafe) |

0.384 | 8.500 | 0.004 | -1.872 | -0.367 | |||

| Impacts of ADRTs (Enhance personal safety and security in public space) |

0.002 | Gender (Man) | 0.263 | 3686.049 | <0.001 | 15.433 | 16.642 | |

| Education level (Trade apprentice/ Tafe) |

0.374 | 4.166 | 0.041 | -1.497 | -0.030 | |||

| Impacts of ADRTs (Promote social equity in transport access) |

0.026 | Education level (Year 10) |

0.461 | 8.447 | 0.004 | -2.246 | -0.437 | |

| Impacts of ADRTs (Improve wildlife habitats) |

0.019 | Gender (Man) | 0.267 | 3613.159 | <0.001 | 15.526 | 16.572 | |

| Age (19-35) | 0.554 | 5.872 | 0.015 | 0.257 | 2.430 | |||

| Age (36-50) | 0.556 | 11.383 | <0.001 | 0.787 | 2.968 | |||

| Age (51-65) | 0.478 | 3.852 | 0.050 | 0.001 | 1.874 | |||

| Education level (Trade apprentice/ Tafe) |

0.386 | 6.634 | 0.010 | -1.750 | -0.238 | |||

5. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADRT | Autonomous Demand Responsive Transit |

| AV | Autonomous Vehicle |

| DRT | Demand Responsive Transit |

| FMLM | First-Mile/Last-Mile |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| PT | Public Transport |

| SAV | Shared Autonomous Vehicle |

| SEQ | South-East Queensland |

| TAFE | Technical and Further Education |

References

- Lau ST, Susilawati S. Shared autonomous vehicles implementation for the first and last-mile services. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Zuo T, Wei H, Chen N. Promote transit via hardening first-and-last-mile accessibility: Learned from modeling commuters’ transit use. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 2020;86:102446. [CrossRef]

- Golbabaei F. Challenges and opportunities in the adoption of autonomous demand responsive transit (ADRT) by adult residents of South East Queensland: Queensland University of Technology; 2023.

- Stocker A, Shaheen S. Shared Automated Vehicles: Review of Business Models. Transportation Sustainability Research Center, University of California, Berkeley: Cooperative Mobility Systems and Automated Driving; 2017. Contract No.: 2017-09.

- Shaheen S, Chan N. Mobility and the sharing economy: Potential to facilitate the first-and last-mile public transit connections. Built Environment. 2016;42(4):573-88. [CrossRef]

- Dong Z, Chen C, Ouyang J, Yan X, Liao C, Chen X, et al. Understanding commuter preferences for shared autonomous electric vehicles in first-mile-last-mile scenario. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 2025;140. [CrossRef]

- Jayatilleke S, Bhaskar A, Bunker J. Autonomous bus adoption in public transport networks: A systematic literature review on potential and prospects. Australasian Transport Research Forum Perth, Australia2023.

- Narayanan S, Chaniotakis E, Antoniou C. Shared autonomous vehicle services: A comprehensive review. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. 2020;111:255-93. [CrossRef]

- Ohnemus M, Perl A. Shared autonomous vehicles: Catalyst of new mobility for the last mile? Built Environment. 2016;42(4):589-602.

- Mo B, Cao Z, Zhang H, Shen Y, Zhao J. Competition between shared autonomous vehicles and public transit: A case study in Singapore. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. 2021;127. [CrossRef]

- Krueger R, Rashidi TH, Rose JM. Preferences for shared autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. 2016;69:343-55.

- Shen Y, Zhang H, Zhao J. Integrating shared autonomous vehicle in public transportation system: A supply-side simulation of the first-mile service in Singapore. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 2018;113:125-36. [CrossRef]

- Basu R, Araldo A, Akkinepally AP, Nahmias Biran BH, Basak K, Seshadri R, et al. Automated Mobility-on-Demand vs. Mass Transit: A Multi-Modal Activity-Driven Agent-Based Simulation Approach. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2018;2672(8):608-18.

- Militão AM, Tirachini A. Optimal fleet size for a shared demand-responsive transport system with human-driven vs automated vehicles: A total cost minimization approach. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 2021;151:52-80. [CrossRef]

- Cyganski R, Heinrichs M, von Schmidt A, Krajzewicz D. Simulation of automated transport offers for the city of Brunswick. Procedia computer science. 2018;130:872-9. [CrossRef]

- Leich G, Bischoff J. Should autonomous shared taxis replace buses? A simulation study. Transportation Research Procedia 2019;41:450–60. [CrossRef]

- Peer S, Müller J, Naqvi A, Straub M. Introducing shared, electric, autonomous vehicles (SAEVs) in sub-urban zones: Simulating the case of Vienna. Transport Policy. 2024;147:232-43. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Jenelius E, Badia H. Efficiency of Connected Semi-Autonomous Platooning Bus Services in High-Demand Transit Corridors. IEEE Open Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems. 2022;3:435-48. [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbühler J, Cats O, Jenelius E. Transitioning towards the deployment of line-based autonomous buses: Consequences for service frequency and vehicle capacity. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 2020;138:491-507. [CrossRef]

- Ongel A, Loewer E, Roemer F, Sethuraman G, Chang F, Lienkamp M. Economic Assessment of Autonomous Electric Microtransit Vehicles. Sustainability. 2019;11(3). [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbühler J, Cats O, Jenelius E. Network design for line-based autonomous bus services. Transportation. 2021;49(2):467-502. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Qu X, Ma X. Improving flex-route transit services with modular autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review. 2021;149. [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou MG, Orfanou FP, Vlahogianni EI, Yannis G, editors. Impacts of Autonomous Shuttle Services on Traffic, Safety and Environment for Future Mobility Scenarios, 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC); 2020; Rhodes, Greece: IEEE.

- Rosell J, Allen J. Test-riding the driverless bus: Determinants of satisfaction and reuse intention in eight test-track locations. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 2020;140:166-89. [CrossRef]

- Hasan U, Whyte A, AlJassmi H. A Microsimulation Modelling Approach to Quantify Environmental Footprint of Autonomous Buses. Sustainability. 2022;14(23). [CrossRef]

- Moorthy A, De Kleine R, Keoleian G, Good J, Lewis G. Shared Autonomous Vehicles as a Sustainable Solution to the Last Mile Problem: A Case Study of Ann Arbor-Detroit Area. SAE International Journal of Passenger Cars - Electronic and Electrical Systems. 2017;10(2):328-36. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Guhathakurta S. Parking spaces in the age of shared autonomous vehicles: How much parking will we need and where? Transportation Research Record. 2017;2651(1):80-91.

- Fagnant DJ, Kockelman KM, Bansal P. Operations of Shared Autonomous Vehicle Fleet for Austin, Texas, Market. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2019;2563(1):98-106.

- Fagnant DJ, Kockelman KM. The travel and environmental implications of shared autonomous vehicles, using agent-based model scenarios. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. 2014;40:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Duan X, Si H, Xiang P. Technology into reality: Disentangling the challenges of shared autonomous electric vehicles implementation from stakeholder perspectives. Energy. 2025;316. [CrossRef]

- Azad M, Hoseinzadeh N, Brakewood C, Cherry CR, Han LD. Fully Autonomous Buses: A Literature Review and Future Research Directions. Journal of Advanced Transportation. 2019;2019:1-16. [CrossRef]

- Hasan U, Whyte A, Al Jassmi H. A Review of the Transformation of Road Transport Systems: Are We Ready for the Next Step in Artificially Intelligent Sustainable Transport? Applied System Innovation. 2019;3(1). [CrossRef]

- Golbabaei F, Yigitcanlar T, Bunker J. The role of shared autonomous vehicle systems in delivering smart urban mobility: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation. 2020;15(10):731-48. [CrossRef]

- Golbabaei; Golbabaei;, Yigitcanlar T, Paz A, Bunker J. Individual Predictors of Autonomous Vehicle Public Acceptance and Intention to Use: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2020;6(4).

- Bala H, Anowar S, Chng S, Cheah L. Review of studies on public acceptability and acceptance of shared autonomous mobility services: past, present and future. Transport Reviews. 2023;43(5):970-96. [CrossRef]

- Golbabaei F, Yigitcanlar T, Paz A, Bunker J. Perceived Opportunities and Challenges of Autonomous Demand-Responsive Transit Use: What Are the Socio-Demographic Predictors? Sustainability. 2023;15(15). [CrossRef]

- Greifenstein M. Factors influencing the user behaviour of shared autonomous vehicles (SAVs): A systematic literature review. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 2024;100:323-45. [CrossRef]

- Golbabaei F, Paz A, Yigitcanlar T, Bunker J. Navigating autonomous demand responsive transport: stakeholder perspectives on deployment and adoption challenges. International Journal of Digital Earth. 2023;17(1). [CrossRef]

- Rahimi A, Azimi G, Jin X. Examining human attitudes toward shared mobility options and autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 2020;72:133-54. [CrossRef]

- Nordhoff S, de Winter J, Payre W, van Arem B, Happee R. What impressions do users have after a ride in an automated shuttle? An interview study. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 2019;63:252-69. [CrossRef]

- Usman M, Li W, Bian J, Chen A, Ye X, Li X, et al. Small and rural towns’ perception of autonomous vehicles: insights from a survey in Texas. Transportation Planning and Technology. 2023;47(2):200-25. [CrossRef]

- Imhof S, Frölicher J, von Arx W. Shared Autonomous Vehicles in rural public transportation systems. Research in Transportation Economics. 2020;83. [CrossRef]

- Sieber L, Ruch C, Hörl S, Axhausen KW, Frazzoli E. Improved public transportation in rural areas with self-driving cars: A study on the operation of Swiss train lines. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 2020;134:35-51. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Jiang Z, Noland RB, Mondschein AS. Attitudes towards privately-owned and shared autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 2020;72:297-306. [CrossRef]

- Wang N, Tang H, Wang Y-J, Huang GQ. Antecedents in rural residents’ acceptance of autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 2024;132:104244. [CrossRef]

- Cao W, Chen Y, Wang K. Revolutionizing commutes: Unraveling the factors shaping Chinese consumers’ acceptance of shared autonomous vehicles (SAVs) with an integrated UTAUT2 model. Research in Transportation Business & Management. 2024;57. [CrossRef]

- Golbabaei F, Yigitcanlar T, Paz A, Bunker J. Understanding Autonomous Shuttle Adoption Intention: Predictive Power of Pre-Trial Perceptions and Attitudes. Sensors (Basel). 2022;22(23). [CrossRef]

- Debbaghi F-Z, Rombaut E, Vanhaverbeke L. Exploring the influence of a virtual reality experience on user acceptance of shared autonomous vehicles: A quasi-experimental study in Brussels. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 2024;107:674-94. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y-H, Lai Y-C. Exploring autonomous bus users’ intention: Evidence from positive and negative effects. Transport Policy. 2024;146:91-101. [CrossRef]

- Mason J, Classen S. Develop and Validate a Survey to Assess Adult’s Perspectives on Autonomous Ridesharing and Ridehailing Services. Future Transportation. 2023;3(2):726-38. [CrossRef]

- Dolins S, Karlsson M, Strömberg H, editors. AVs Have a Sharing Problem: Examining User Acceptance of Shared, Autonomous Public Transport in Sweden. 2023 IEEE 26th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC); 2023 24-28 Sept. 2023.

- Chng S, Anowar S, Cheah L. Understanding Shared Autonomous Vehicle Preferences: A Comparison between Shuttles, Buses, Ridesharing and Taxis. Sustainability. 2022;14(20). [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Wu J, Zhu C, Hu K, Du Y. Factors Influencing the Acceptance of Robo-Taxi Services in China: An Extended Technology Acceptance Model Analysis. Journal of Advanced Transportation. 2022;2022:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Classen S, Mason JR, Hwangbo SW, Sisiopiku V. Predicting Autonomous Shuttle Acceptance in Older Drivers Based on Technology Readiness/Use/Barriers, Life Space, Driving Habits, and Cognition. Front Neurol. 2021;12:798762.

- Gurumurthy KM, Kockelman KM. Analyzing the dynamic ride-sharing potential for shared autonomous vehicle fleets using cellphone data from Orlando, Florida. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems. 2018;71:177-85. [CrossRef]

- Vicente AL. Traffic microsimulation of Autonomous Vehicles Flow in Ronda de Dalt of Barcelona: Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya; 2022.

- Tian Q, Wang DZW, Lin YH. Optimal deployment of autonomous buses into a transit service network. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review. 2022;165. [CrossRef]

- Jayatilleke S, Bhaskar A, Bunker J. Unveiling the Challenges and Opportunities of Autonomous Bus Integration in Rural and Suburban Areas: An Expert Interview Study. [Manuscript submitted for publication]. 2025.

- Wang Z, Safdar M, Zhong S, Liu J, Xiao F. Public Preferences of Shared Autonomous Vehicles in Developing Countries: A Cross-National Study of Pakistan and China. Journal of Advanced Transportation. 2021;2021(1):5141798. [CrossRef]

- Földes D, Csiszár C, editors. Framework for planning the mobility service based on autonomous vehicles. 2018 Smart City Symposium Prague (SCSP); 2018 24-25 May 2018.

- Földes D, Csiszar C, editors. Framework for planning the mobility service based on autonomous vehicles. 2018 Smart City Symposium Prague (SCSP); 2018.

- Faroqi H, Mesbah M. Inferring trip purpose by clustering sequences of smart card records. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. 2021;127:103131. [CrossRef]

- Kwak SK, Kim JH. Statistical data preparation: management of missing values and outliers. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2017;70(4):407-11. [CrossRef]

- Sari Aslam N, Ibrahim MR, Cheng T, Chen H, Zhang Y. ActivityNET: Neural networks to predict public transport trip purposes from individual smart card data and POIs. Geo-spatial Information Science. 2021;24(4):711-21. [CrossRef]

- Kim SW, Gwon GP, Hur WS, Hyeon D, Kim DY, Kim SH, et al. Autonomous Campus Mobility Services Using Driverless Taxi. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 2017;18(12):3513-26. [CrossRef]

- Westerman H, Black J. Preparing for Fully Autonomous Vehicles in Australian Cities: Land-Use Planning—Adapting, Transforming, and Innovating. Sustainability. 2024;16(13).

- Miller J, How JP, editors. Demand estimation and chance-constrained fleet management for ride hailing. 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2017 24-28 Sept. 2017.

- Lai W-T, Chen C-F. Behavioral intentions of public transit passengers—The roles of service quality, perceived value, satisfaction and involvement. Transport policy. 2011;18(2):318-25.

- Transport and Infrastructure Council. T2 Cost Benefit Analysis. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development; 2018.

- Whitmore A, Samaras C, Hendrickson CT, Scott Matthews H, Wong-Parodi G. Integrating public transportation and shared autonomous mobility for equitable transit coverage: A cost-efficiency analysis. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Silva Ó, Cordera R, González-González E, Nogués S. Environmental impacts of autonomous vehicles: A review of the scientific literature. Science of The Total Environment. 2022;830:154615. [CrossRef]

- Silva I, Calabrese JM. Emerging opportunities for wildlife conservation with sustainable autonomous transportation. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2024;22(2). [CrossRef]

- Labaw PJ. Advanced questionnaire design. Cambridge, Mass.: Abt Books; 1980.

- Mortoja MG, Yigitcanlar T. Why is determining peri-urban area boundaries critical for sustainable urban development? Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 2021;66(1):67-96.

- Sunshine Coast Council. Public transport 2024 [Available from: https://www.sunshinecoast.qld.gov.au/living-and-community/roads-and-transport/transport-options/public-transport.

- Lockyer Valley Regional Council. Getting Around 2024 [Available from: https://www.lockyervalley.qld.gov.au/our-region/about-the-lockyer-valley/getting-around.

- Kline R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling2016.

- Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review. 2019;31(1):2-24. [CrossRef]

- Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology. 1932.

- Collins LM. Research Design and Methods. In: Birren JE, editor. Encyclopedia of Gerontology (Second Edition). New York: Elsevier; 2007. p. 433-42.

- McCrum-Gardner E. Which is the correct statistical test to use? British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2008;46(1):38-41. [CrossRef]

- Kothari C. Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Age International. 2004.

- Gupta A, Gupta N. Research methodology: SBPD publications; 2022.

- Pandey P, Pandey MM. Research methodology: Tools and techniques2015.

- Kadkhodaei M, Shad R, Ziaee SA. Affecting factors of double parking violations on urban trips. Transport Policy. 2022;120:80-8. [CrossRef]

- Khan SK, Shiwakoti N, Stasinopoulos P, Chen Y, Warren M. The impact of perceived cyber-risks on automated vehicle acceptance: Insights from a survey of participants from the United States, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia. Transport Policy. 2024;152:87-101. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Cao J, Douma F. The impacts of vehicle automation on transport-disadvantaged people. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Kittelson & Associates B, P., Group, K., Institute, T. A. M. T., & Arup. Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual. Washington D.C.; 2013. Report No.: 978-0-309-28344-1.

- Gurumurthy KM, Kockelman KM, Zuniga-Garcia N. First-Mile-Last-Mile Collector-Distributor System using Shared Autonomous Mobility. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. 2020;2674(10):638-47. [CrossRef]

- Wen J, Chen YX, Nassir N, Zhao J. Transit-oriented autonomous vehicle operation with integrated demand-supply interaction. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. 2018;97:216-34. [CrossRef]

- Scheltes A, de Almeida Correia GH. Exploring the use of automated vehicles as last mile connection of train trips through an agent-based simulation model: An application to Delft, Netherlands. International Journal of Transportation Science and Technology. 2017;6(1):28-41. [CrossRef]

- Salazar M, Lanzetti N, Rossi F, Schiffer M, Pavone M. Intermodal Autonomous Mobility-on-Demand. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems. 2020;21(9):3946-60.

- Fielbaum A, Pudāne B. Are shared automated vehicles good for public- or private-transport-oriented cities (or neither)? Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 2024;136:104373. [CrossRef]

- Milford M, Anthony S, Scheirer W. Self-Driving Vehicles: Key Technical Challenges and Progress Off the Road. IEEE Potentials. 2020;39(1):37-45. [CrossRef]

- Lazányi K. Perceived Risks of Autonomous Vehicles. Risks. 2023;11(2):26. [CrossRef]

- Islam MR, Abdel-Aty M, Lee J, Wu Y, Yue L, Cai Q. Perception of people from educational institution regarding autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 2022;14:100620. [CrossRef]

- Günthner T, Proff H. On the way to autonomous driving: How age influences the acceptance of driver assistance systems. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour. 2021;81:586-607. [CrossRef]

- Thomas E, McCrudden C, Wharton Z, Behera A. Perception of autonomous vehicles by the modern society: A survey. IET Intelligent Transport Systems. 2020;14(10):1228-39. [CrossRef]

- Srour Zreik R, Harvey M, Brewster SA, editors. Age Matters: Investigating Older Drivers’ Perception of Level 3 Autonomous Cars as a Heterogeneous Age Group. Adjunct Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications; 2023.

- Hassan HM, Ferguson MR, Vrkljan B, Newbold B, Razavi S. Older adults and their willingness to use semi and fully autonomous vehicles: A structural equation analysis. Journal of transport geography. 2021;95:103133. [CrossRef]

- Golbabaei F, Dwyer J, Gomez R, Peterson A, Cocks K, Bubke A, et al. Enabling mobility and inclusion: Designing accessible autonomous vehicles for people with disabilities. Cities. 2024;154:105333. [CrossRef]

- Nourinejad M, Bahrami S, Roorda MJ. Designing parking facilities for autonomous vehicles. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological. 2018;109:110-27. [CrossRef]

- Kumakoshi Y, Hanabusa H, Oguchi T. Impacts of shared autonomous vehicles: Tradeoff between parking demand reduction and congestion increase. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 2021;12:100482. [CrossRef]

- Patel RK, Etminani-Ghasrodashti R, Kermanshachi S, Rosenberger JM, Pamidimukkala A, Foss A. Identifying individuals’ perceptions, attitudes, preferences, and concerns of shared autonomous vehicles: During- and post-implementation evidence. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 2023;18:100785. [CrossRef]

- Lavieri PS, Garikapati VM, Bhat CR, Pendyala RM, Astroza S, Dias FF. Modeling individual preferences for ownership and sharing of autonomous vehicle technologies. Transportation research record. 2017;2665(1):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Nazari F, Noruzoliaee M, Mohammadian AK. Shared versus private mobility: Modeling public interest in autonomous vehicles accounting for latent attitudes. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. 2018;97:456-77. [CrossRef]

- Schuß M, Wintersberger P, Riener A. Security Issues in Shared Automated Mobility Systems: A Feminist HCI Perspective. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2021;5(8):43. [CrossRef]

- Eby DW, Molnar LJ, Zakrajsek JS, Ryan LH, Zanier N, Louis RMS, et al. Prevalence, attitudes, and knowledge of in-vehicle technologies and vehicle adaptations among older drivers. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2018;113:54-62. [CrossRef]

- Lee C, Seppelt B, Reimer B, Mehler B, Coughlin JF, editors. Acceptance of vehicle automation: Effects of demographic traits, technology experience and media exposure. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting; 2019: SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

- Greenwood PM, Lenneman JK, Baldwin CL. Advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS): Demographics, preferred sources of information, and accuracy of ADAS knowledge. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour. 2022;86:131-50.

- Kim S, Anjani S, van Lierop D. How will women use automated vehicles? Exploring the role of automated vehicles from women’s perspective. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 2024;27:101228. [CrossRef]

| Predictor variable | Category | N=273 n(%) |

| Gender | Man | 93 (34.1) |

| Woman | 179 (65.6) | |

| Non-binary | 1 (0.4) | |

| Age | 19-35 | 73 (26.7) |

| 36-50 | 77 (28.2) | |

| 51-65 | 69 (25.3) | |

| 66 or higher | 54 (19.8) | |

| Education Level |

Year 10 | 38 (13.9) |

| Year 12 | 51 (18.7) | |

| Trade apprentice/ Tafe | 90 (33.0) | |

| Undergraduate degree | 57 (20.9) | |

| Post-graduate degree | 37 (13.6) | |

| Employment status | Unemployed/ Homemaker | 18 (6.6) |

| Retired | 64 (23.4) | |

| Full-time/ Part-time student | 15 (5.5) | |

| Part-time / casually employed | 67 (24.5) | |

| Full-time employed | 109 (39.9) | |

| Annual Household income | Prefer not to answer | 22 (8.1) |

| Under $15,600 | 7 (2.6) | |

| $15,600 - $31,199 | 25 (9.2) | |

| $31,200 - $51,999 | 33 (12.1) | |

| $52,000 - $77,999 | 36 (13.2) | |

| $78,000 - $103,999 | 49 (17.9) | |

| $104,000 or more | 101 (37.0) |

| Variable | Gender | Age | Occupational Level | Education Level | Household Income | Disability Status | Driver’s License Status |

| X2 and Significance | |||||||

| Familiarity with ADRTs | 75.101 P = <0.001 |

8.880 P = 0.713 |

10.515 P = 0.838 |

26.693 P = 0.045 |

17.291 P = 0.836 |

8.175 P = 0.417 |

8.974 P = 0.345 |

| Ridden in an AV | 19.211 P = <0.001 |

2.544 P = 0.864 |

16.505 P = 0.036 |

9.429 P = 0.307 |

13.583 P = 0.328 |

11.310 P =0.023 |

7.994 P = 0.092 |

| Response Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Strongly Agree | Somewhat Agree | Neutral | Somewhat Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted |

| Vehicle Type | ||||||||

| Small shuttle | 3.56 | 1.136 | 56 | 104 | 75 | 14 | 24 | 0.816 |

| Minibus shuttle | 3.45 | 1.203 | 55 | 93 | 73 | 24 | 28 | 0.705 |

| Standard sized conventional bus | 2.90 | 1.304 | 40 | 48 | 81 | 53 | 51 | 0.870 |

| Service offering | ||||||||

| Completely replace conventional buses | 2.65 | 1.303 | 24 | 59 | 57 | 64 | 69 | 0.922 |

| Operate as a connector to existing fixed route bus services | 3.51 | 1.170 | 51 | 111 | 64 | 20 | 27 | 0.904 |

| Connector to longer distance services | 3.40 | 1.205 | 53 | 86 | 78 | 28 | 28 | 0.902 |

| Operate as private taxi services | 3.30 | 1.236 | 51 | 77 | 79 | 35 | 31 | 0.905 |

| Accommodate as a multipurpose service | 3.34 | 1.199 | 50 | 80 | 82 | 34 | 27 | 0.905 |

| Integrated with other transport offerings | 3.51 | 1.164 | 59 | 89 | 80 | 22 | 23 | 0.901 |

| Operate 24/7 | 3.62 | 1.238 | 79 | 81 | 68 | 19 | 26 | 0.916 |

| Trip Purpose | ||||||||

| Work | 3.38 | 1.145 | 43 | 96 | 83 | 25 | 26 | 0.906 |

| School | 2.87 | 1.249 | 26 | 71 | 66 | 62 | 48 | 0.915 |

| University | 3.41 | 1.201 | 52 | 93 | 71 | 30 | 27 | 0.901 |

| Shopping | 3.40 | 1.149 | 43 | 101 | 75 | 29 | 25 | 0.905 |

| Medical | 3.22 | 1.238 | 46 | 75 | 77 | 43 | 32 | 0.907 |

| Leisure | 3.40 | 1.162 | 47 | 91 | 85 | 23 | 27 | 0.904 |

| Emergency | 2.50 | 1.237 | 20 | 39 | 73 | 66 | 75 | 0.934 |

| Special events or gatherings | 3.45 | 1.153 | 48 | 99 | 81 | 18 | 27 | 0.904 |

| Demographic Group | ||||||||

| School children | 2.72 | 1.279 | 21 | 67 | 64 | 56 | 65 | 0.953 |

| University students | 3.45 | 1.172 | 48 | 104 | 72 | 21 | 28 | 0.949 |

| Working professionals | 3.56 | 1.130 | 55 | 105 | 74 | 16 | 23 | 0.949 |

| Senior citizens | 3.21 | 1.284 | 48 | 76 | 71 | 40 | 38 | 0.900 |

| Tourists | 3.48 | 1.173 | 49 | 108 | 68 | 20 | 28 | 0.984 |

| Leisure travellers | 3.50 | 1.141 | 49 | 106 | 76 | 16 | 26 | 0.984 |

| People with physical disabilities | 2.92 | 1.308 | 34 | 65 | 73 | 46 | 55 | 0.984 |

| People with sensory disabilities | 2.91 | 1.304 | 35 | 61 | 75 | 48 | 54 | 0.984 |

| People with cognitive disabilities | 2.77 | 1.250 | 24 | 57 | 82 | 51 | 59 | 0.984 |

| Low-income individuals | 3.39 | 1.126 | 47 | 80 | 105 | 15 | 26 | 0.984 |

| Middle-income individuals | 3.47 | 1.091 | 47 | 93 | 96 | 15 | 22 | 0.984 |

| High-income individuals | 3.39 | 1.155 | 49 | 83 | 93 | 22 | 26 | 0.984 |

| Land Use | ||||||||

| Residential neighbours | 3.31 | 1.204 | 41 | 100 | 65 | 37 | 30 | 0.910 |

| Industrial/ business parks | 3.47 | 1.160 | 52 | 98 | 74 | 25 | 24 | 0.903 |

| University precincts | 3.74 | 1.171 | 77 | 106 | 55 | 11 | 24 | 0.901 |

| Agricultural land areas | 2.97 | 1.212 | 33 | 60 | 83 | 60 | 37 | 0.942 |

| Tourist destinations | 3.52 | 1.176 | 57 | 99 | 70 | 22 | 25 | 0.904 |

| Town centres | 3.52 | 1.234 | 65 | 93 | 63 | 24 | 28 | 0.905 |

| Response Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Strongly Agree | Somewhat Agree | Neutral | Somewhat Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted |

| Impact on Passenger Performance | ||||||||

| Improve quality of service | 3.22 | 1.127 | 28 | 93 | 97 | 22 | 33 | 0.884 |

| Improve user experience | 3.21 | 1.097 | 30 | 82 | 102 | 33 | 26 | 0.882 |

| Improve accessibility | 3.48 | 1.108 | 48 | 102 | 76 | 28 | 19 | 0.901 |

| Improve safety | 2.77 | 1.158 | 22 | 43 | 107 | 52 | 49 | 0.891 |

| Improve security | 2.70 | 1.136 | 19 | 43 | 96 | 68 | 47 | 0.899 |

| Social Impacts | ||||||||

| Create new job opportunities | 2.70 | 1.211 | 20 | 58 | 69 | 73 | 53 | 0.944 |

| Improve social inclusion for disadvantaged groups | 3.18 | 1.184 | 36 | 77 | 93 | 33 | 34 | 0.928 |

| Enhance community interaction and social cohesion | 3.06 | 1.097 | 24 | 68 | 113 | 36 | 32 | 0.925 |

| Benefit local businesses and economic activity | 3.22 | 1.112 | 28 | 91 | 95 | 30 | 29 | 0.929 |

| Influence urban planning and development | 3.36 | 1.112 | 36 | 100 | 88 | 23 | 26 | 0.930 |

| Improve public health and well-being | 3.01 | 1.096 | 26 | 56 | 117 | 43 | 31 | 0.928 |

| Enhance personal safety and security in public spaces | 2.81 | 1.185 | 28 | 76 | 118 | 21 | 30 | 0.932 |

| Promote social equity in transport access | 3.19 | 1.084 | 39 | 102 | 85 | 19 | 28 | 0.928 |

| Environmental Impacts | 3.41 | 1.201 | 52 | 93 | 71 | 30 | 27 | 0.901 |

| Reduce GHG emissions | 3.38 | 1.132 | 39 | 102 | 85 | 19 | 28 | 0.911 |

| Reduce noise pollution | 3.53 | 1.088 | 50 | 102 | 86 | 14 | 21 | 0.910 |

| Reduce local air pollution | 3.51 | 1.095 | 47 | 106 | 82 | 16 | 22 | 0.904 |

| Reduce heat in built-up areas | 3.22 | 1.078 | 34 | 69 | 115 | 32 | 23 | 0.912 |

| Improve wildlife habitats | 2.86 | 1.105 | 20 | 47 | 125 | 38 | 43 | 0.942 |

| Variable | Gender | Age | Occupational Level | Education Level | Household Income | Disability Status | Driver’s License Status |

| Significance | |||||||

| Suitable vehicle types for ADRTs | |||||||

| Small shuttle | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | ns |

| Minibus shuttle | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Standard-sized conventional bus | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | ns |

| Suitable service offerings for ADRTs | |||||||

| Completely replace conventional buses | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Operate as a connector to existing fixed route bus services | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Connector to longer distance services | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Operate as private taxi services | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Accommodate as a multipurpose service | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Integrated with other transport offerings | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Operate 24/7 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Suitable trip purposes for ADRTs | |||||||

| Work | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| School | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| University | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Shopping | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Medical | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Leisure | ns | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Emergency | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Special events or gatherings | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Suitable demographic groups for ADRTs | |||||||

| School children | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| University students | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | * | ns |

| Working professionals | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns |

| Senior citizens | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Tourists | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Leisure travellers | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| People with physical disabilities | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| People with sensory disabilities | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| People with cognitive disabilities | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Low-income individuals | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Middle-income individuals | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| High-income individuals | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns |

| Suitable land use for ADRTs | |||||||

| Residential neighbours | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Industrial/ business parks | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| University precincts | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns |

| Agricultural land areas | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Tourist destinations | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Town centres | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Impacts on passenger performance from ADRTs | |||||||

| Improve quality of service | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Improve user experience | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Improve accessibility | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Improve safety | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Improve security | ** | * | * | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Social impacts from ADRTs | |||||||

| Create new job opportunities | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Improve social inclusion for disadvantaged groups | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Enhance community interaction and social cohesion | ns | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Benefit local businesses and economic activity | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Influence urban planning and development | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | * | ns |

| Improve public health and well-being | ns | * | ns | * | ns | ns | ns |

| Enhance personal safety and security in public spaces | ** | * | ns | * | ns | ns | ns |

| Promote social equity in transport access | ns | * | ns | * | ns | ns | ns |

| Environmental impacts from ADRTs | |||||||

| Reduce GHG emissions | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns |

| Reduce noise pollution | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Reduce local air pollution | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Reduce heat in built-up areas | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Improve wildlife habitats | * | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).