1. Introduction

The Annona genus includes tropical and subtropical crops of commercial importance in Mexico and the world [

1]. Among the important crops of the genus Annona in Mexico is the soursop (

Annona muricata L.), which currently has commercial plantations in different states of Mexico [

2]. Nayarit is the main producer, Vidal-Hernández et al. [

2] reported a growing area of 2,300 h with a production of 16,100 tons per year in this region. In 2019, the government of Mexico reported a national production of 30,790 tons of soursop, with a commercial value of

$248,170 million in Mexican pesos [

3].

Soursop pulp is a source of fiber, which also contains several compounds that may have health advantages if consumed in moderation. Soursop extract has demonstrated important pharmaceutical properties [

4]. The main uses of soursop are as fresh fruit and to produce pulp used as an ingredient in foods and beverages [

5]. However, fruit losses are common due to diseases, and pests occurred in preharvest and postharvest causing a great economic impact [

2]; nevertheless, the most economically important disease is anthracnose [

2]. The causative agent of this disease is the fungus

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Penz.) and the inoculation can occur in seedlings and adult plants, affecting stems, branches, leaves, flowers, and fruits; causing low yields and deteriorating the quality of the final product [

6].

A viable alternative to preserving fresh fruits and vegetables is the use of edible coatings as a protective wrap. In this sense, the use of edible coatings in highly perishable products such as fruit and vegetable provide a solution to increase their shelf life [

7]. due that protect against infections caused by fungi, mechanical damage, and effect on breathing rate, modifying the permeability of gases and water vapor [

8,

9].

Recently, the use of chitosan (poly-D-glucosamine and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine) is among the most used biopolymers for coating fruits and vegetables, due to its biocompatibility, null toxicity, high malleability, and its antimicrobial and antifungal properties [

10,

11]. Furthermore, chitosan has an excellent capacity to form semipermeable biofilms for CO2 and O2 gases. In addition, it has an antifungal effect, inhibiting the growth of mycelium, germination, and damage to hyphae and spores [

11,

12]. The use of chitosan-based coatings added with essential oils is one of the most recently tested technologies in the field of fruit coatings. The addition of essential oils of oregano, rosemary, cinnamon, cloves, garlic, eucalyptus, and chili have been shown to be efficient for the control of pathogens in postharvest, due to the active compounds present in these as carvacrol, cinnamic acid, citral, thymol, linalool, menthol, among others, inhibiting the growth of microorganisms, enhancing the shelf life of agricultural products, and maintaining the sensory properties [

8]. In this context, the aim of this research was to evaluate the effect of chitosan-based coatings with essential oils on the physiological, antifungal, and shelf-life properties of soursop fruits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Harvesting, isolation and identification of the fungus C. gloeosporioides of soursop

Soursop fruits were harvested at physiological maturity from Venustiano Carranza, Nayarit (21° 32´ 2.77´´north latitude and 104° 58´ 39.73´´ west longitude) with a warm and sub-humid climate. The fruits were washed twice, the first with simple water to remove impurities, and the second with a 2% chlorine solution. Finally, they were allowed to drain to dry.

Soursop fruits were stimulated to anthracnose development, and cuts with affected surfaces were inoculated in petri dishes with PDA. DNA was extracted from the mycelium and quantified with a Nanodrop 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) at 260 and 280 nm. ITS1F-ITS4 primer was used for Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS). The reaction was carried out on a thermocycler T100 (Bio-Rad). The products were purified with the Freeze Kit N Squeeze DNA Gel Extraction Spin Columns (Bio-Rad). Finally, the sequence obtained was compared and aligned with those of the NCBI Gen Bank database, USA, through Nucleotide BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2015) [

13,

14]

2.2. Obtaining chitosan from shrimp waste

A local seafood restaurant from Celaya, Guanajuato, México donated the shrimp wastes, which were sun-dried for 24 h and then ground in an industrial blender (TAPISA, T12 L, Cd. México, México). The chitosan conversion was according to the procedure reported by Acosta-Ferreira et al. (2020) with slight modifications. First, the chitin was demineralized by mixing the crushed residue with an HCl solution 3.6% (w/w) for 4 h at room temperature, then the demineralized material was mixed with a NaOH solution 4.5% (w/v) at 60° C for 4 h to remove proteins. Finally, the material was subjected to alkaline deacetylation mixing it with a NaOH solution of 45% (p/v) at 120° C for 2 h. Subsequently, the material was washed with common water to neutralize, then the material was dried at 45° C for 12 h. The chitosan obtained was ground to reduce the particle size prior to use.

2.2.1. Determination of degree of deacetylation (DDA) and molecular weight (Mw)

The DDA of chitosan was determined using an UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Multiskan Go, USA) according with the methodology reported by Liu et al. [

15]. A calibration curve (R2=0.999) was obtained with N-acetylglucosamine and (+)-glucosamine as monomers at 201 nm. The molecular weight (Mw) was determined using an Ubbelohde viscometer at 25±1 °C. To obtain the standard curve (R2 = 0.9613), five chitosan concentrations (0.0014, 0.0012, 0.0010, 0.008, and 0.006 g mL

-1) were dissolved in CH3COOH 0.3 M/ CH3COONa 0.2 M solution and filtered through membranes with a pore size of 0.45 mm. The viscosity Mw was calculated based on the Mark-Houwink equation:

where [η] is the intrinsic viscosity, K and a are constant values to depend on the nature of the polymer and solvent as well as of the temperature, and M is the relative molecular weight. In this work, K = 0.074 mL g-1 and a = 0.76 are the empirical constants that depend of the polymer nature, the solvent and temperature [

16]

.

2.3. Preparation and application of coatings

The 1% chitosan solution (w/v) was prepared by dissolving chitosan in acetic acid 1% (v/v). The coatings were prepared by mixing 1% chitosan solution and adding cinnamon essential oils and thyme. Four treatments were established for non-inoculated and for inoculated fruits with C. gloeosporioides spores. Treatments for fruits were: 1) without coating, 2) coatings with chitosan 1%, 3) Chitosan 1% + cinnamon 0.1%, 4) Chitosan 1% + thyme 0.1%. To form the film on the soursop fruits, a thin layer of chitosan solution was applied with a food-grade brush and dried with a hair dryer (CONAIR® Corporation, USA) using air at room temperature.

2.4. Shelf life and physicochemical analysis

The monitoring of the shelf life of soursop fruits was performed by physical and chemical analyses (pH, weight loss, instrumental color, total soluble solids (TSS), titratable acidity (TA), and flavor index). The respiration (CO2) and ethylene production rates were evaluated in soursop fruits non-inoculated. Measurements were made as follows, the day of processing was considered as day 0 and after 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10.

2.4.1. Weight loss

The weight loss was established by calculating the difference between the initial weight of the soursop fruits of each experiment and the weight obtained at the end of each storage time evaluated in semi-analytical balance (Schuler Scientific, 6001), and the results were expressed as a percentage of weight loss [

17]

.

2.4.2. Instrumental color

The color measurements were made using a Konica Minolta colorimeter (Model CR-410, Germany), using the CIEL L*C*h* (Commission Internationale de L’Eclairage) system. The results were expressed as L* (which represents the percentage of brightness, 0 = dark and 100 = light), C* (represents chroma or saturation, 0 = center of lightness axis), and h* (is the hue angle, 0° = red, 90° = yellow, 180° = green and 270° = blue) [

17]

.

2.4.3. pH, soluble solid content, titratable acidity, and flavor index

The pH was determined from soursop juice with a digital potentiometer (Hanna® Instrument, HI98130), previously calibrated with saturated solution [

17]

. The SSC was done using an ATAGO optical refractometer (RX-50000i-Plus, Tokyo, Japan) at 20° C, and the results were expressed as TSS [

17]

. The TA was done by titrating 20 mL of the sample (previously mixed with 25 g of fruit and 20 mL of distilled water) and phenolphthalein using 0.096 N NaOH. The results were expressed as a percentage of citric acid [

18]

. The flavor index was determined as the ratio of TSS/TA [

17].

2.5. Respiration and ethylene production rates

The respiration and ethylene production rates were determined by placing the heavy fruits inside an airtight container of known volume; subsequently, after 2 h of keeping the fruit hermetically sealed 10 mL of the gas was then extracted from the headspace with the aid of a syringe and injected into an Agilent Gas Chromatograph (GC) (Agilent Technologies, California, USA). The GC has equipped an open column with silica porous layer packaging connected simultaneously to a flame ionization detector (FID) at 170° C and a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) at 170° C, as carrier gas N2 was used with a flow rate of 2 mL/min. The injector and furnace of the chromatograph were maintained at 150 and 80° C, respectively, and CO2 (460 ppm) and ethylene (100 ppm) standards (Quark INFRA) were used for quantification [

19]

.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The experiments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3) and data represent the mean value. Regression analyses were applied with different models for each variable. It used a linear model and polynomial models according to the data tendency, also, an ANOVA using a completely randomized design and LSD post hoc test were done (α = 0.05) for each day for respiration and ethylene variables.

3. Results

3.1. Degree of deacetylation and molecular weight of chitosan

Chitosan obtained presented low molecular weight (169 kDa) and 83% of the degree of deacetylation (DDA), these characteristics are due to the chemical treatment applied, which caused depolymerization of chitosan chains (mainly during the deactivation process under alkaline conditions) [

10]. Muley et al. [

20] reported the production of chitosan from shrimp shells by chemical treatment (deactivation with 50% NaOH) reaching 78.04% of DDA and 173 kDa of Mw. In addition, the chitosan obtained was similar in the molecular weight and DDA properties supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (50-190 kDa and 75-85% DDA, CAS Number 9012-76-4). The methodology used in this work proved to be efficient in producing quality chitosan compared to even trademarks. The chitosan obtained by the chemical method presented good physicochemical properties (molecular weight, and degree of deacetylation) to produce coatings.

3.2. Shelf life of soursop fruits

Figure 1 show the results of chitosan-based coating of non-inoculated and inoculated fruits with C. gloesporoides. The results show that the coatings with cinnamon and thyme increased the shelf life and helped to maintain the quality of soursop fruits in inoculated and uninfected fruits. This relates to the effect of coatings and essential oils on the metabolic processes that occur at the cell wall level in the maturation process, because, by modifying the atmosphere, altering ethylene production and maturation process, which translated into an increase in the shelf life of the fruit [

21].

In this sense, Bill et al. [

22] proved that the use of thyme in chitosan coatings decreases the severity of anthracnose in avocados, while López-Mata et al. [

12] showed that the use of cinnamon chitosan coatings prolongs the shelf life of strawberries. In addition, in a study by Montalvo-González et al. [

23] in soursop, reported that wax-based coatings with 1-methylcyclopropane at 25°C achieved shelf lives of 8 days. These results are similar to those found in the present study for soursop, decreasing the severity of anthracnose compared to the control, and increasing the effect of coatings when the essential oils of thyme and cinnamon were used, extending the shelf life until day 10 and maintaining acceptable quality, even in the inoculated fruits since the pulp did not present anthracnose. Then, the chitosan-based coatings with essential oils of thyme and cinnamon proved to be a good alternative to decrease the growth of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in soursop and maintain the quality of the fruits (

Figure 2).

It is now known that the main protection barrier for fruit and vegetables are structural polysaccharides and proteins, which form networks through cohesion forces, conferring mechanical and barrier properties to gases (O2 and CO2), coatings with essential oils in fruits have been shown to help maintain these barriers, physicochemical properties, and offer antioxidant characteristics, antifungal, and antimicrobial [

24].

3.3. Physical and chemical analyses of soursop fruits

3.3.1. Weight loss determination

Figure 3 shows the effect of chitosan-based coatings on weight loss of soursop, non-inoculated (a) and inoculated with C. gloeosporioides (b). Results for cinnamon and thyme essential oil treatments showed a reduction of up to 20% and 19% in weight loss for the non-inoculated and inoculated soursops, respectively, until the 10 days of treatment. The non-inoculated treatments showed a significant difference from the control, also, the coatings with essential oils presented a significant difference compared to treatments with only chitosan. These results demonstrate that coatings with cinnamon and thyme essential oils in combination with chitosan have an effective barrier against water loss.

The present behavior is related to the semi-permeable barrier formed by the chitosan coatings added with essential oils, which is associated with reduced weight loss, browning, and improved fruit quality [

25]. In this sense, [

21] reported a weight loss of 12% in uncoated soursop at 6 days, while fruits coated with 1% chitosan lost the same weight until 9 days. On the other hand, Liu et al. [

26] showed 30% weight loss in cherimoya (control), while cherimoyas coated with 1% chitosan showed 26% weight loss at 10 days of evaluation. The results obtained in this research show weight loss values in the ranges reported by these authors.

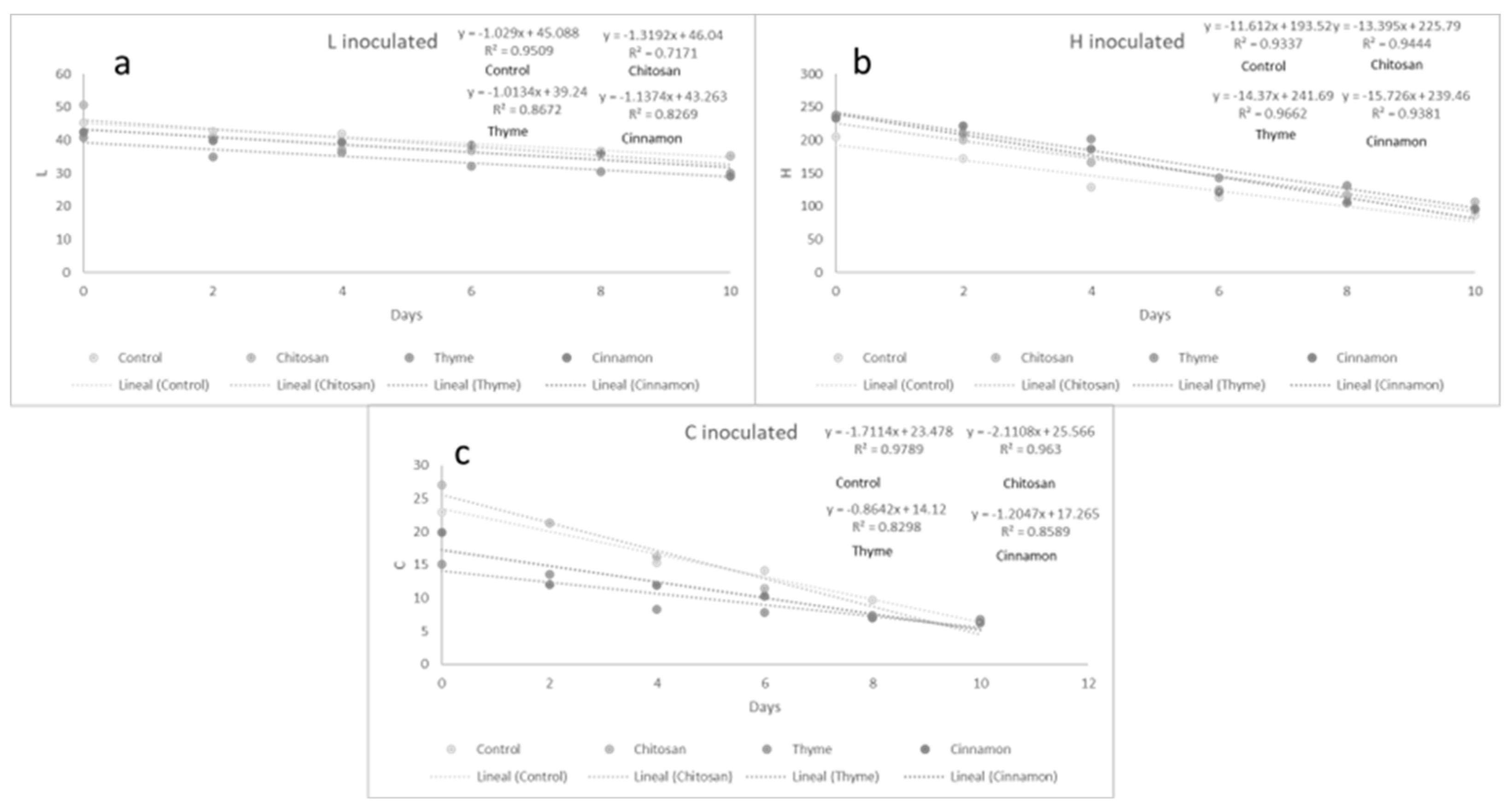

3.3.2. Instrumental color

The effect of chitosan-based coatings on the color of soursop fruits inoculated and non-inoculated with C. gloesporoides is shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. For both treatments, the green color of soursop peels changed with time, reaching a maximum value of Hue (250) at 10 days and the non-inoculated treatment using coating with thyme oil showed a significant difference from the control. In addition, as time passed, a decrease in the saturation (C*) of the green color of the fruits was observed with a significant difference.

The brightness values (L*) for the coatings with cinnamon oil presented a significant difference in the non-inoculated treatments. Moreover, the inoculated treatments do not show significant differences with any of the coatings used. In this sense, Evangelista-Lozano et al. [

27] reported brightness values like those obtained in the present study (L* = 44.5), while Hue was different with lower values (h* = 96) obtaining yellow hues. Jiménez-Zurita et al. [

28] evaluated the color of the soursop epidermis, concluding that the fruits have an opaque and poorly luminous green color (h* = 151.7 – 164.9; C* = 9.4 – 21.4; L* = 30.2 – 45.8), the color results reported are comparable to those found in the present work. The color change is a characteristic of the fruits as part of the ripening, and therefore it is used as a criterion to define the maturity index. This process is due to the degradation of the pigments of the soursop fruit, which generates changes in color saturation, causing the colors of the fruit to oscillate between yellow (carotenoids) and red-purple (anthocyanins) [

29].

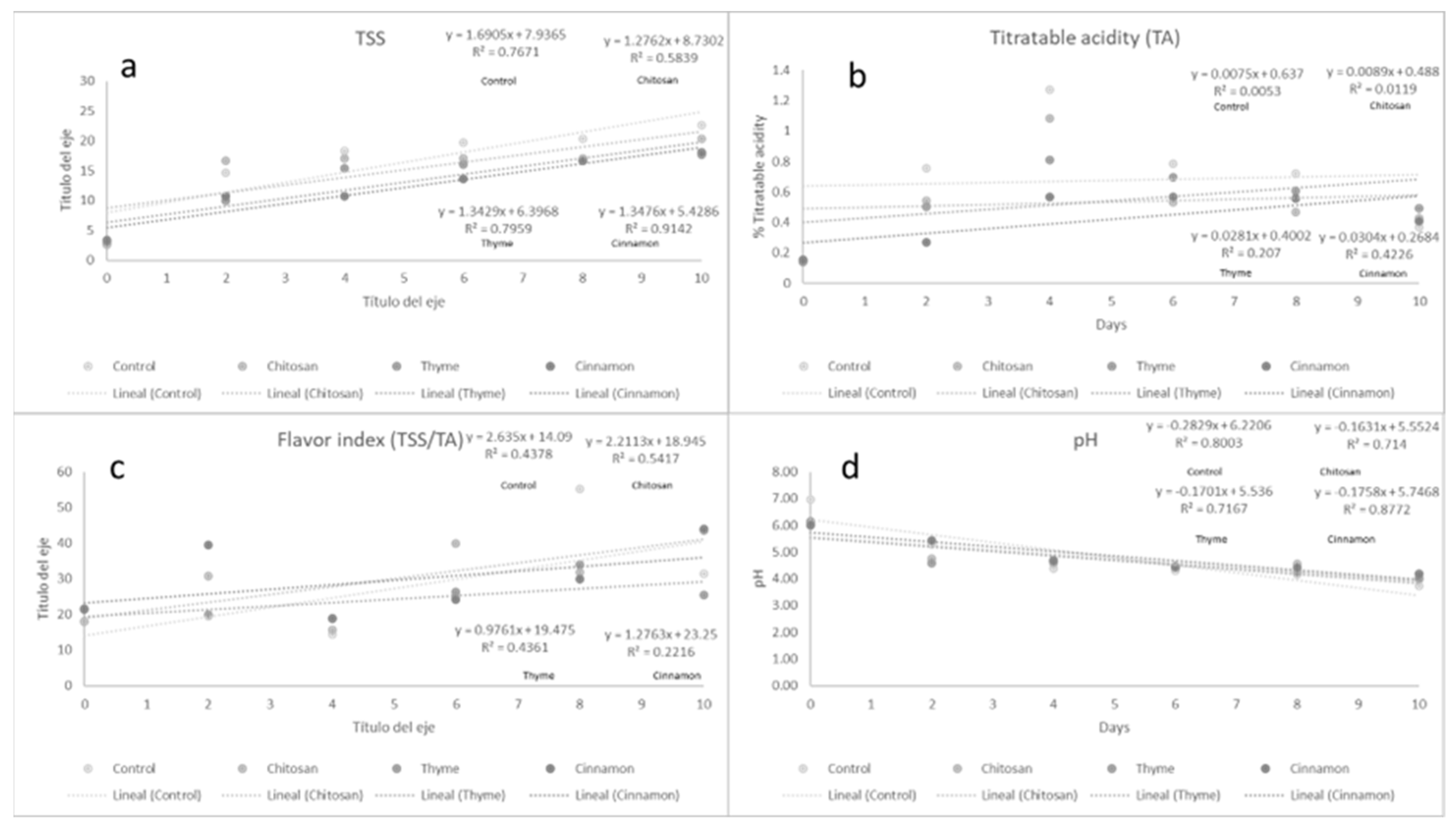

3.3.3. pH and titratable acidity

Regarding the pH parameter, there were no significant differences from day 2 to 10 in all the treatments evaluated, reaching an average value of pH = 4.5 at 10 days of evaluation,

Figure 6d. Ojeda et al. [

30] reported pH levels ranging from 3.9 to 4.3 to 22° C in soursop fruits, which was similar to the final values reported in the present research. Torres et al. [

31] reported that the pH decreases and the TSS increase in climacteric fruits are related to the degradation of starch into reducing sugars or its conversion into pyruvic acid.

Titratable acidity values showed a peak on day 4, however, from day 6 the acidity values decreased and remained similar until day 10 (

Figure 6b). This increase in the acidity values at the beginning of the maturation process is due to the hydrolysis of starch to generate organic acids and volatile compounds, later, at the end of the ripening stage these values decrease because organic acids are used as a substrate for conversion into sugars and in the breathing process [

32]. It can be observed that the fruits coated with chitosan plus cinnamon were those that presented the lowest acidity values and it agrees with what was reported by Sotelo-Alcántara et al. [

33] who reported that chitosan and cinnamon coatings promoted a low accumulation of organic acids in soursop (A. muricata L.). Likewise, Hernández-Ibáñez et al. [

34] reported a decrease in acidity in banana fruits treated with chitosan as storage days progressed, demonstrating that the maturation process decreases the concentration of organic acids in the fruits and that chitosan-based coatings can help maintain this natural process, without affecting the process or even helping.

3.3.4. Total soluble solids and flavor index

The results of total soluble solids (TSS) are shown in

Figure 6a. The uncoated soursop fruits showed the highest values of TSS at day 10 (22%), while the fruits coated with essential oils presented 18% less TSS, at the same time. This behavior with coatings has been observed by several authors.

Jiménez-Zurita et al. [

28] pointed out that soursop must have at least 9% of TSS for consumption and that it can reach up to 16%. While Evangelista-Lozano et al. [

27] reported values between 11 and 12% of TSS and Arrazola-Paternina et al. [

35] indicated that at the stage of commercial maturity, it can reach 20.5% of TSS. In the present study, the values of TSS are between 16 and 18 on day 10, being within the limits of consumption, while the controls reached 22% of TSS. Then, the chitosan coatings do not affect the TSS values in the consumption stage. The behavior of the values of TSS is related to the degree of ripeness of the fruit since during this process sugar synthesis is promoted by the hydrolysis of starch into simpler carbohydrates of the disaccharide and monosaccharide type (glucose, sucrose, and fructose), which is promoted by the action of enzymes such as amylases [

36].

The results of the flavor index are shown in

Figure 6c, where it is possible to observe that the coatings with chitosan and cinnamon presented the highest values at 10 days. This behavior is related to the increase in sugar concentration or to the decrease in acidity values in the fruits as part of the maturation process, Sotelo-Alcántara et al. [

33] reported a flavor index of 40 in soursop fruits coated with cinnamon, a result similar to that found in the presents work at day 10.

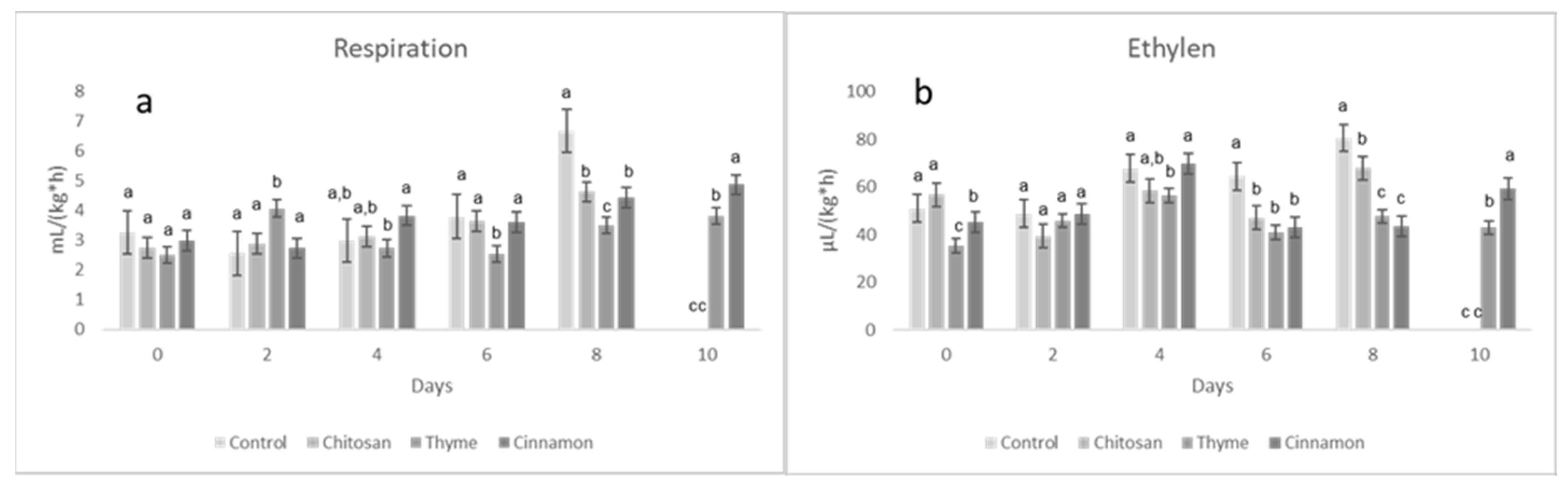

3.4. Respiration and ethylene production rates

Figure 7 shows the results for respiration and ethylene of coated soursop fruits in non-inoculated treatments. The results show similar behavior in the first 4 days between the treatments, however, after 8 days significant differences were observed between the coated and without coatings fruits, and thyme treatments were the best reducing the respiration process until 47%, also, by day 10, fruits without essential oils were completely degraded,

Figure 6a. Due to its high rate of respiration, the fruits of soursop are classified as climacteric, this type of fruit is often harvested in physiological maturity and matures after harvest because the respiratory intensity and ethylene production are high [

28]

. Respiration is a process that allows the synthesis of metabolites and causes the degradation of the fruits, in this sense, the coatings based on chitosan with cinnamon and thyme, increasing the shelf life by at least two days, due to the formation of a barrier that decreased the level of respiration and ethylene [

17].

4. Conclusions

The chitosan obtained by the chemical method presented good physicochemical properties (molecular weight, and degree of deacetylation) for the production of coatings. Respiration, ethylene, and weight loss values showed a significant reduction when chitosan coatings were applied with cinnamon and thyme, increasing the shelf life by at least two days. Chitosan-based coatings with essential oils of thyme and cinnamon proved to be a good alternative to decrease the growth of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in soursop and maintain the quality of the fruits.

Author Contributions

Francisco Morales-Chávez: formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft preparation. Carlos Núñez-Colín: data curation, validation, supervision; Luis Mariscal-Amaro: methodology, investigation, supervision; Adán Morales-Vargas: writing—review and editing, visualization; Iran Alia-Tejacal: methodology, funding acquisition; Edel Rafael Rodea-Montero: data curation, validation, writing—review and editing; Claudia Grijalva-Verdugo: writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; Rafael Veloz-García: funding acquisition, supervision, validation; Jesús Rubén Rodríguez-Núñez: conceptualization, project administration, funding acquisition, writing—original draft preparation.

Acknowledgments

To the fund SAGARPA-CONACYT, with project number 2015-04-266891 for the financing of the project and to the Department of Genomic Services LANGEBIO, CINVESTAV-Campus Guanajuato for the sequencing services.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no interest conflicts.

References

- Rodríguez-Núñez JR, Campos-Rojas E, Andrés-Agustín J, Alia-Tejacal I, Peña-Caballero V, Madera-Santana TM, Núñez-Colín CA. Distribution, eco-climatic characterization, and potential growing regions of Annona cherimola Mill. (Annonaceae) in Mexico. Ethnobiol. Conserv. 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Hernández L, López-Moctezuma H, Vidal-Martínez A, Ruiz-Bello R, Castillo RD, Chiquito-Contreras G. La situación de las annonaceae en México: principales plagas, enfermedades y su control. Rev Bras Frutic. 2014, 36, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIAP. Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Agrícola y Pesquera. In: Cierre agrícola SEMARNAT 2021. México, Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. Available online: https://nube.siap.gob.mx/cierreagricola/ (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Afzaal M, Saeed F, Asghar A, Shah YA, Ikram A, Ateeq H, Hussain M, Ofoedu CE, Chacha JS. Nutritional and Therapeutic Potential of Soursop. J. of Food Quality. 2022, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiencheu B, Egbe A.C, Achidi AU, Tenyang N, Ngongang EFT, Djikeng FT, Foss BT. Nutritional, organoleptic, and phytochemical properties of soursop (Annona muricata) pulp and juice after postharvest ripening. European J. Nutr. Food Safety. 2021, 13, 15-28.

- Huang H, Tian C, Huang Y, Huang H. Biological control of poplar anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Penz.) Penz. & Sacc. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2020, 30, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero C, Falguera V, Muñoz A. Películas y recubrimientos comestibles: importancia y tendencias recientes en la cadena hortofrutícola. Revista Tumbaga. 2010, 5, 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-García L, Bautista-Baños S, Barrera-Necha L, Bosquez-Molina E, Alia-Tejacal I, Estrada-Carrillo M. Compuestos antimicrobianos adicionados en recubrimientos comestibles para uso en productos hortofrutícolas. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. 2010, 28, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, M. A, Niaz B, Saeed F, Afzaal M, Islam F, Hussain M., Mahwish, Khalid, H.M.S, Siddeeg A, Al-Farga A. Edible coatings for enhancing safety and quality attributes of fresh produce: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2022, 25, 1817–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Núñez JR, Madera-Santana T, Sánchez-Machado D, López-Cervantes J, Soto H. Chitosan/hydrophilic plasticizer-based films: preparation, physicochemical and antimicrobial properties. J. Polym. Enviro. 2014, 22, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocira A, Kozłowicz K, Panasiewicz K, Staniak M, Szpunar-Krok E, Hortynska P. Polysaccharides as edible films and coatings: characteristics and influence on fruit and vegetable quality—A review. Agron. 2021, 11, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mata M, Ruiz-Cruz S, Navarro-Preciado C, Ornelas-Paz J, Estrada-Alvarado I, Gassos-Ortega L, Rodrigo-García J. Efecto de recubrimientos comestibles de quitosano en la reducción microbiana y conservación de la calidad de las fresas. Biotecnia. 2012, 14, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardes M, Bruns TD. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White TJ, Burns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., and White, T.J. (Eds.). PCR Protocol: A Guide to Methods and Applications (315-322) (1990) USA, Academic Press.

- Liu N, Chen X. G., Park H.J., Liu C.G., Liu C.G.S., Meng X.H., Yu L.J., Effect of MW and concentration of chitosan on antibacterial activity of Escherichia coli, Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 64, 60–65. [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Ferreira S,; Castillo O,; Madera-Santana T,; Mendoza-García A,; Núñez-Colín C,; Grijalva-Verdugo C,; Villa-Lerma G,; Morales-Vargas A,; Rodríguez-Núñez R. Production and physicochemical characterization of chitosan for the harvesting of wild microalgae consortia. Biotechnol Rep. 2020, 28, e00554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madera-Santana T, De Dios-Aguilar A, Colín-Chávez C, Mariscal-Amaro A, Núñez-Colín C, Veloz-García R, Guzmán-Maldonado H, Peña-Caballero V, Grijalva-Verdugo C, Rodríguez-Núñez R. Recubrimiento a base de quitosano y extracto acuoso de hoja de Moringa oleífera obtenido por UMAE y su efecto en las propiedades fisicoquímicas de fresa (Fragaria x ananassa). Biotecnia. 2019, 21, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. (2007). Official methods of analysis (18th ed.). Washington, DC: Association of Official Analytical Chemists.

- Saltveit, M.E. , Respiratory metabolism. In: Gross, K. C., Wang, C. Y., Saltveit, M. (Eds.), Agricultural Handbook 66—The Commercial Storage of Fruits, Vegetables, and Florist and Nursery Stocks. USDA Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC. Available from the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA orat 2016. Available online: http://www.ba.ars.usda.gov/ hb66/contents.html.

- Muley A, Chaudhari A, Mulchandani H, Singhal R. Extraction and characterization of chitosan from prawn shell waste and its conjugation with cutinase for enhanced thermo-stability. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Guerrero A, González-Estrada R, Romanazzi G, Landi L, Gutiérrez-Martínez P. Effects of chitosan in the control of postharvest anthracnose of soursop (Annona muricata) fruit. Rev. Mex. Ing. Química. 2020, 19, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bill M, Sivakumar D, Korsten L, Thompson K. The efficacy of combined application of edible coatings and thyme oil in inducing resistance components in avocado (Persea americana Mill.) against anthracnose during post-harvest storage. Crop Prot. 2014, 64, 159-167. [CrossRef]

- Montalvo-González E, León-Fernández E, Rea-Paez H, Mata-Montes De Oca M, Tovar-Gómez B. Uso combinado de 1-Meticiclopropeno y emulsiones de cera en la conservación de guanábana (Annona muricata). Rev. Bras.Frutic. 2014, 36, 206–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aider, M. Chitosan application for active bio-based films production and potential in the food industry. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador A, Cuquerella J, Monterde A. Efecto del quitosano aplicado como recubrimiento en mandarinas ‘fortune’. Rev. Iberoam Tecnol. Postcos. 2003, 5, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Liu J, Li H, Yuan C, Zhong J, Chen Y. Influence of postharvest citric acid and chitosan coating treatment on ripening attributes and expression of cell wall related genes in cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.) fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 198, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista-Lozano S, Cruz-Castillo G, Pérez-González S, Mercado-Silva E, Dávila-Ortiz G. Producción y calidad frutícola de guanábanos (Annona muricata L.) provenientes de semilla de jiutepec, Morelos, México. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 2003, 9, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Zurita J, Balois-Morales R, Alia-Tejacal I, Juárez-López P, Sumaya-Martínez T, Bello-Lara E. Caracterización de frutos de guanábana (Annona muricata L.) en Tepic, Nayarit, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 2016, 7, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Pinzón IM, Fischer G, Corredor G. Determinación de los estados de madurez del fruto de la gulupa (Passiflora edulis Sims). Agron. Colom. 2007, 25, 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda G, Coronado J, Nava R, Sulbarán B, Araujo D, Cabrera L. Caracterización fisicoquímica de la pulpa de la guanábana (Annona muricata) cultivada en el occidente de Venezuela. Boletín del Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas. 2007, 41, 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Torres R, Montes EJ, Pérez OA, Andrade RD. Relation of color and maturity stage with physicochemical, properties of tropical fruits. Inf. Tecnol. 2013, 24, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussán-Sarria S, Torres-León C, Reyes-Calvache M. Efecto del recubrimiento comestible sobre los atributos fisicoquı́micos de mango ‘Tommy Atkins’ mínimamente procesado y refrigerado. Acta Agron. 2014, 63, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelo-Alcántara A, Alia-Tejacal I, Rodríguez-Núñez R, Campos-Rojas E, Juárez-López P, Pérez-Arias A. Postharvest effects of a chitosan-cinnamon essential oil coating on soursop fruits (Annona muricata L.). Acta Hortic. 2022, 1340. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ibáñez A, Bautista-Baños S, Gutiérrez-Martínez P. Potential of chitosan for controlling crown rot disease of banana (Musa acuminate) fruit cv. ’Enano gigante’. In: Nevárez, M.G. and Ortega-Rivas, E. (Eds). Food science and food biotechnology essentials: A contemporary perspective. México, Asociación Mexicana de Ciencias de los Alimentos, A.C. 2012, 129-136.

- Arrazola-Paternina S, Barrera-Violeth L, Villalba-Cadavid I. Determinación física y bromatológica de la guanábana cimarrona (Annona glabra L.) del departamento de Córdoba. Orinoquia. 2013, 17, 159-166.

- Romanazzi G, Sanzani S, Bi Y, Tian S, Gutiérrez-Martínez P, Alkan N. Induced resistance to control postharvest decay of fruit and vegetables. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 122, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).