Submitted:

24 April 2024

Posted:

26 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of Coating Solutions

2.2.2. Coating Treatment

2.2.3. Evaluation of Decay Index and Marketability

2.2.4. Measurement of Respiration Rate, Weight Loss, and Firmness

2.2.5. Determination of Total Soluble Solids (TSS), Titratable Acidity (TA), and Soluble Protein Levels

2.2.6. Determination of Membrane Permeability and Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content

2.2.7. Determination of and H2O2

2.2.8. Analyses of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

2.2.9. Determination of Ascorbic Acid (AsA) and Glutathione (GSH) Levels

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

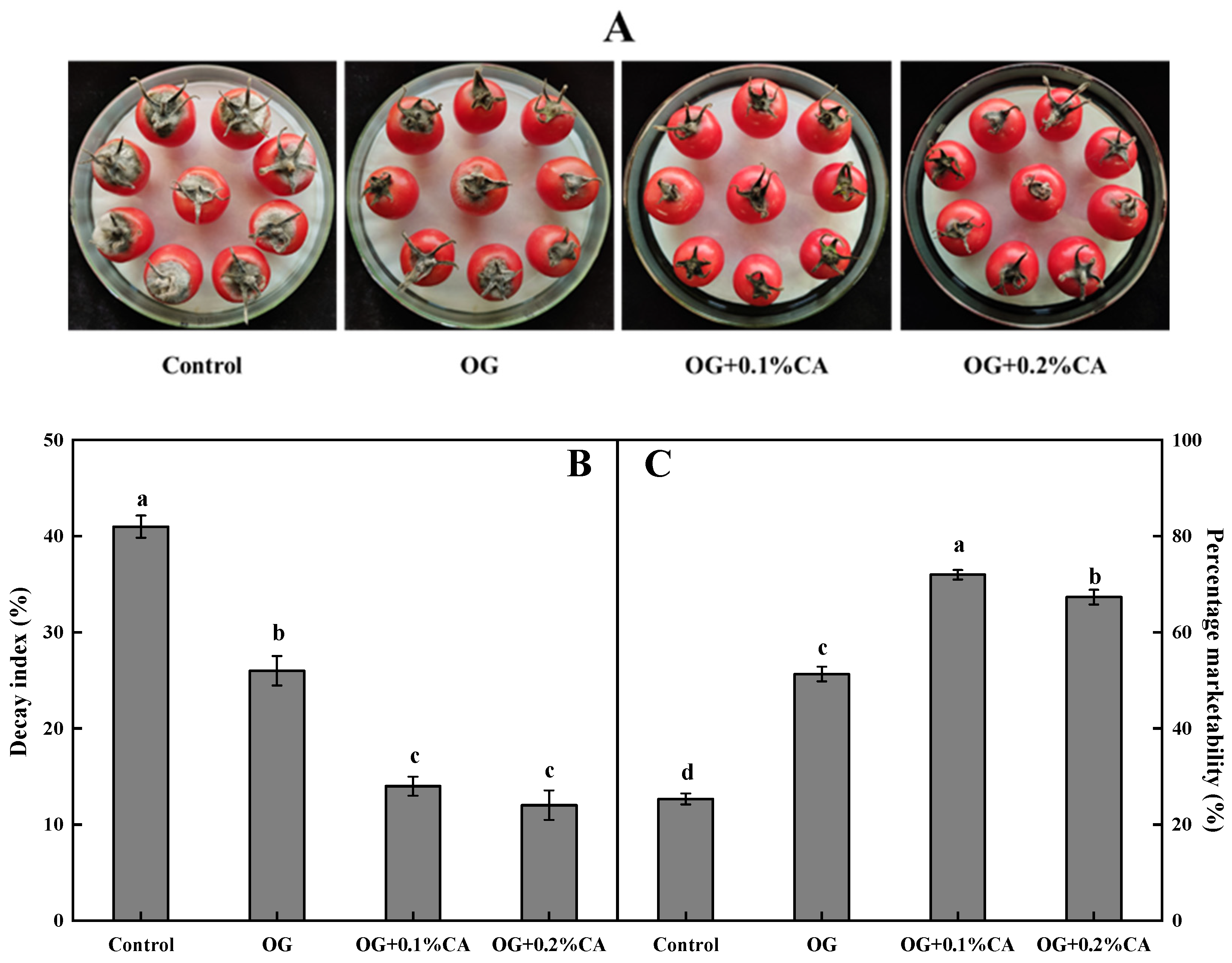

3.1. Fruit Decay Index and Marketability

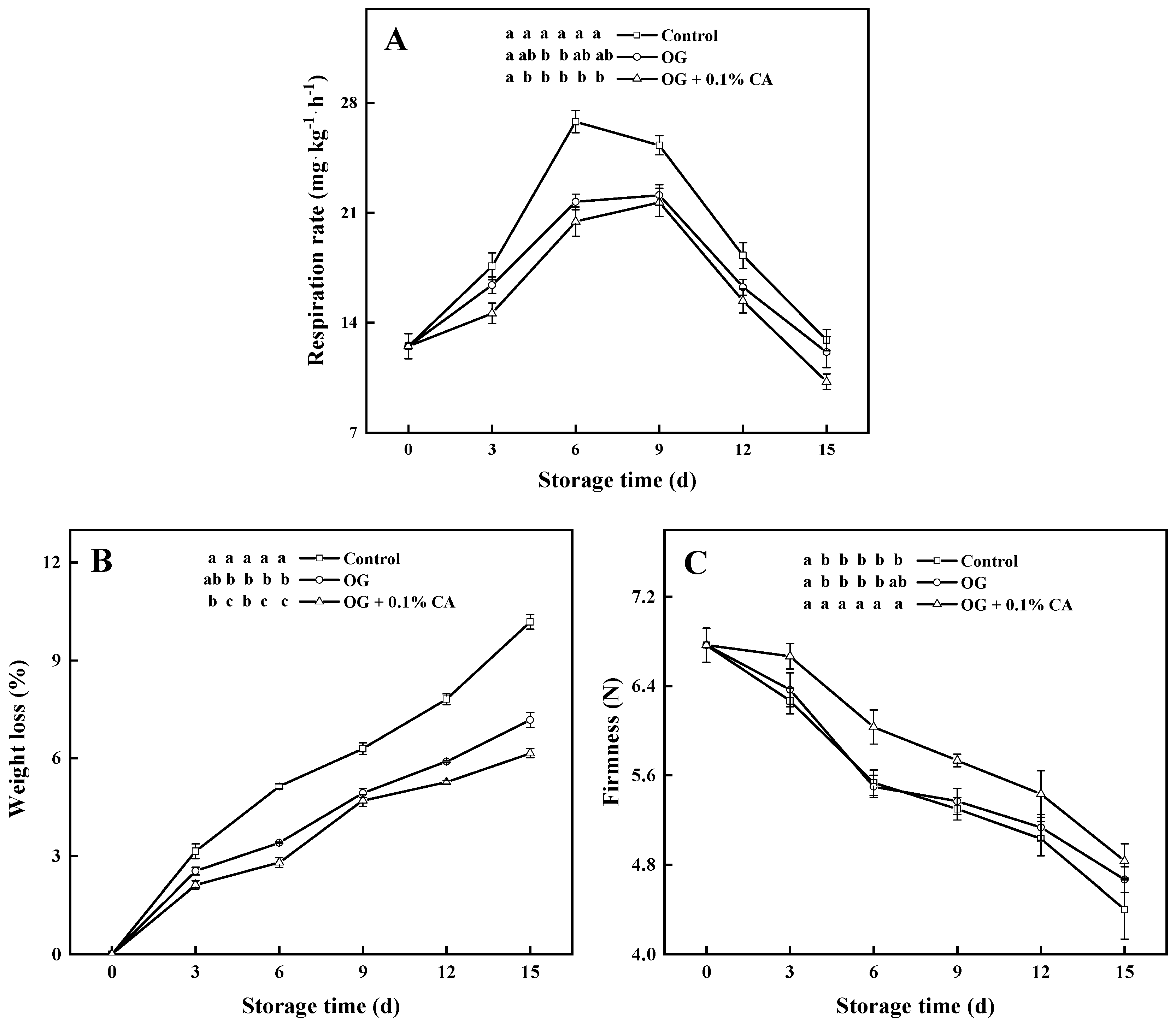

3.2. Respiration Rate, Weight Loss, and Firmness

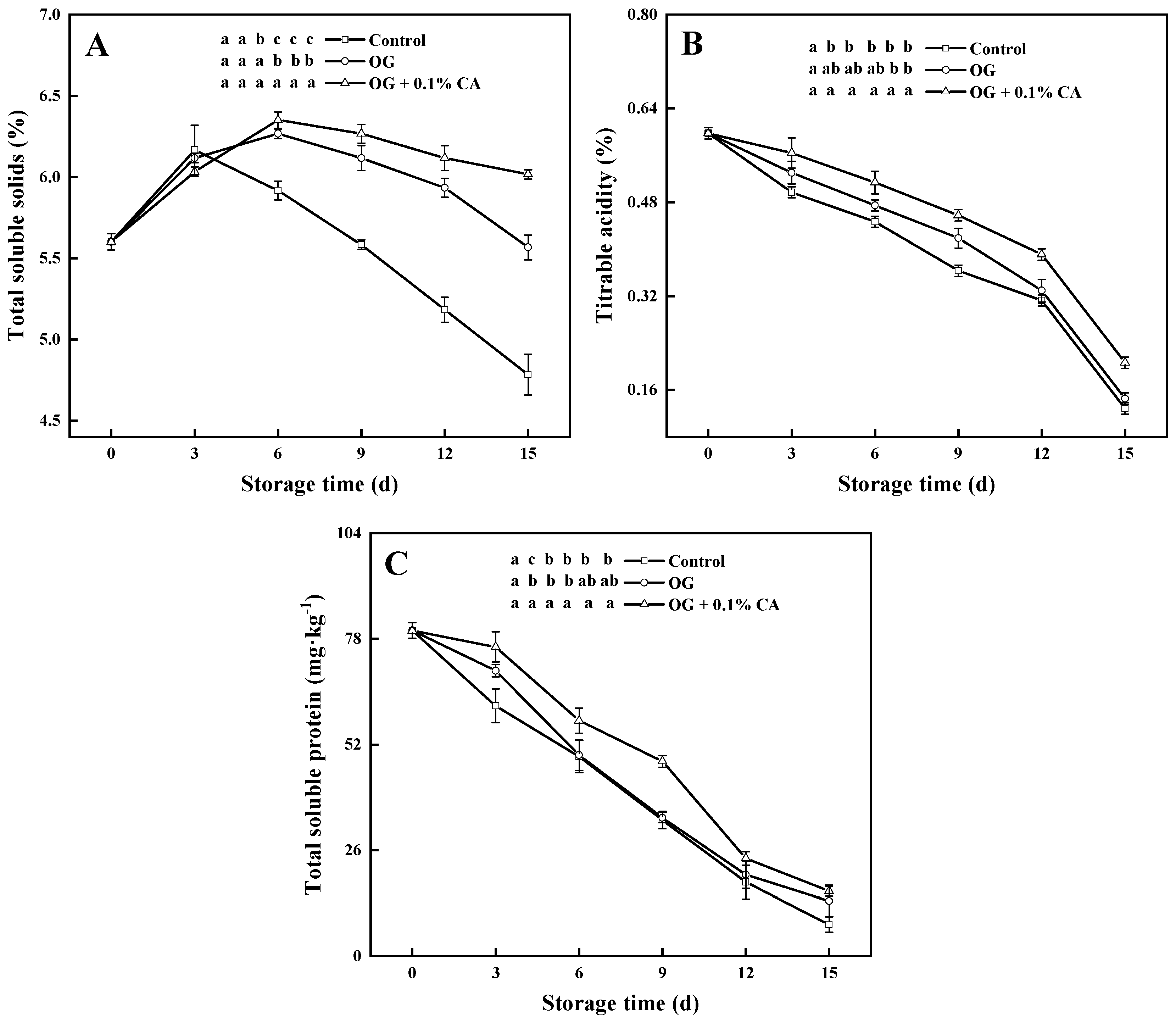

3.3. TSS, TA, and Soluble Protein Content

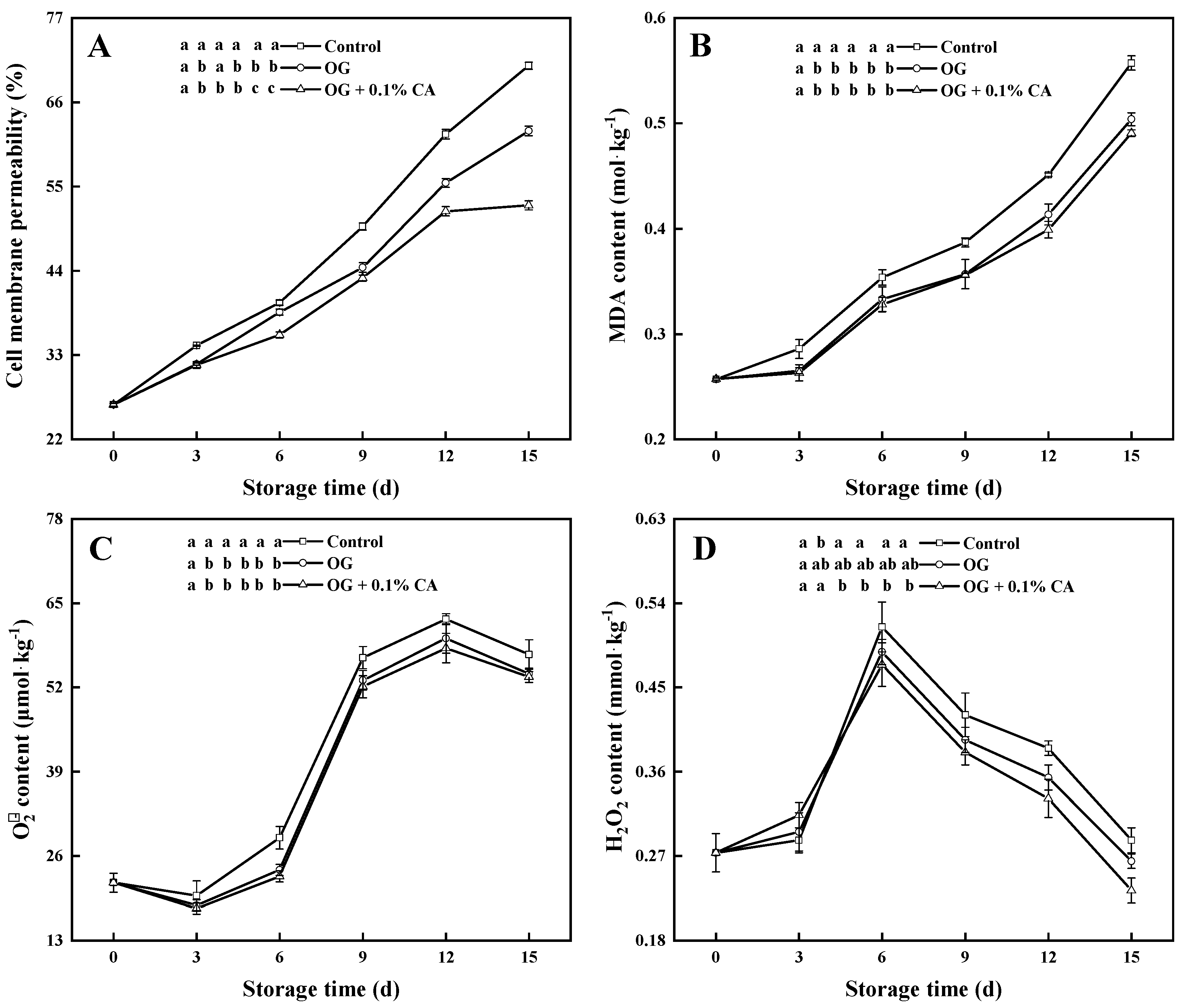

3.4. Membrane Permeability and MDA Content

3.5. and H2O2 Content

3.6. Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

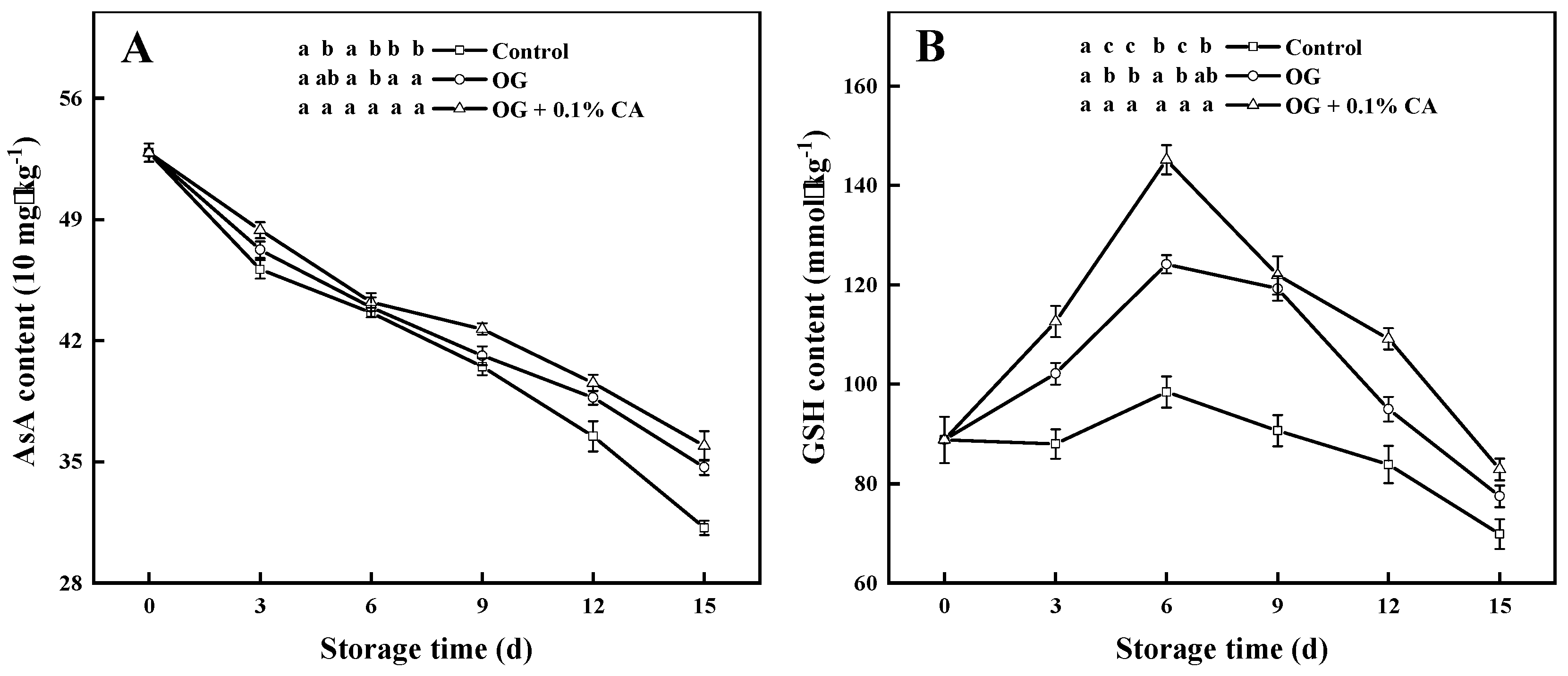

3.7. AsA and GSH Contents

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pu, Y.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Applications of Plant-Derived Food by-Products to Maintain Quality of Postharvest Fruits and Vegetables. jiaoTrends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 1105–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tao, J.; Zhang, H. Peach Gum Polysaccharides-Based Edible Coatings Extend Shelf Life of Cherry Tomatoes. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagundes, C.; Palou, L.; Monteiro, A.R.; Pérez-Gago, M.B. Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose-Beeswax Edible Coatings Formulated with Antifungal Food Additives to Reduce Alternaria Black Spot and Maintain Postharvest Quality of Cold-Stored Cherry Tomatoes. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 193, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, A.; Manjarres, J.J.; Ramírez, C.; Bolívar, G. Use of an Exopolysaccharide-Based Edible Coating and Lactic Acid Bacteria with Antifungal Activity to Preserve the Postharvest Quality of Cherry Tomato. LWT 2021, 151, 112225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzakis, N.; Xylia, P.; Chrysargyris, A. Sage Essential Oil Improves the Effectiveness of Aloe Vera Gel on Postharvest Quality of Tomato Fruit. Agronomy 2019, 9, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawab, A.; Alam, F.; Hasnain, A. Mango Kernel Starch as a Novel Edible Coating for Enhancing Shelf- Life of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum) Fruit. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safari, Z.S.; Ding, P.; Juju Nakasha, J.; Yusoff, S.F. Combining Chitosan and Vanillin to Retain Postharvest Quality of Tomato Fruit during Ambient Temperature Storage. Coatings 2020, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Maqbool, M.; Ramachandran, S.; Alderson, P.G. Gum Arabic as a Novel Edible Coating for Enhancing Shelf-Life and Improving Postharvest Quality of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2010, 58, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendía−Moreno, L.; Soto−Jover, S.; Ros−Chumillas, M.; Antolinos, V.; Navarro−Segura, L.; Sánchez−Martínez, M.J.; Martínez−Hernández, G.B.; López−Gómez, A. Innovative Cardboard Active Packaging with a Coating Including Encapsulated Essential Oils to Extend Cherry Tomato Shelf Life. LWT 2019, 116, 108584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Juhaimi, F.Y. Physicochemical and Sensory Characteristics of Arabic Gum-Coated Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Fruits during Storage: Tomato Fruits Coated with Gum Arabic. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2014, 38, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, F. Edible Coating of Fruits and Vegetables Using Natural Gums: A Review. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20, S570–S589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, H.E.; Zou, X.; Shi, J.; Mahunu, G.K.; Zhai, X.; Mariod, A.A. Quality and Postharvest-Shelf Life of Cold-Stored Strawberry Fruit as Affected by Gum Arabic (Acacia Senegal) Edible Coating. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, e12527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Anjum, M.A.; Nawaz, A.; Naz, S.; Ejaz, S.; Sardar, H.; Saddiq, B. Tragacanth Gum Coating Modulates Oxidative Stress and Maintains Quality of Harvested Apricot Fruits. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 2439–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri, M.; Barzegar, M.; Sahari, M.A.; Niakousari, M. Application of Tragacanth Gum Impregnated with Satureja Khuzistanica Essential Oil as a Natural Coating for Enhancement of Postharvest Quality and Shelf Life of Button Mushroom (Agaricus Bisporus). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etemadipoor, R.; Mirzaalian Dastjerdi, A.; Ramezanian, A.; Ehteshami, S. Ameliorative Effect of Gum Arabic, Oleic Acid and/or Cinnamon Essential Oil on Chilling Injury and Quality Loss of Guava Fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 266, 109255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidpour, R.; Hamidpour, S.; Hamidpour, M.; Shahlari, M.; Sohraby, M.; Shahlari, N.; Hamidpour, R. Russian Olive (Elaeagnus Angustifolia L.): From a Variety of Traditional Medicinal Applications to Its Novel Roles as Active Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Mutagenic and Analgesic Agent. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifian-Nejad, M.S.; Shekarchizadeh, H. Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Oleaster (Elaeagnus Angustifolia L.) Polysaccharides Extracted under Optimal Conditions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 124, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ncama, K.; Magwaza, L.S.; Mditshwa, A.; Tesfay, S.Z. Plant-Based Edible Coatings for Managing Postharvest Quality of Fresh Horticultural Produce: A Review. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, Z.; Khan, M.R.; Mubeen, R.; Hassan, A.; Saeed, F.; Afzaal, M. Exploring the Effect of Cinnamon Essential Oil to Enhance the Stability and Safety of Fresh Apples. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Liao, X.; Li, C.; Abdel-Samie, M.A.; Siva, S.; Cui, H. Cold Nitrogen Plasma Modified Cuminaldehyde/β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex and Its Application in Vegetable Juices Preservation. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, S.; Loganathan, T.; Chandran, M.; Priyanka, R.; Kavipriya, K.; Pushpalatha, G.L.G.L.; Aruna, D.; Abraham, G.; Jayakumararaj, R. ADME-Tox Profile of Cuminaldehyde (4-Isopropylbenzaldehyde) from Cuminum Cyminum Seeds for Potential Biomedical Applications. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2022, 12, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh Behbahani, B.; Noshad, M.; Falah, F. Cumin Essential Oil: Phytochemical Analysis, Antimicrobial Activity and Investigation of Its Mechanism of Action through Scanning Electron Microscopy. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 136, 103716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, Y.; Addo, K.A.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, X. Effects of Cuminaldehyde on Toxins Production of Staphylococcus Aureus and Its Application in Sauced Beef. Food Control 2022, 137, 108960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Kundu, M.; Dutta, S.; Mahalanobish, S.; Ghosh, N.; Das, J.; Sil, P.C. Enhancement of Anti-Neoplastic Effects of Cuminaldehyde against Breast Cancer via Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticle Based Targeted Drug Delivery System. Life Sci. 2022, 298, 120525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S. Molecular Insight into the Interactions between Starch and Cuminaldehyde Using Relaxation and 2D Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 278, 118932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhag, R.; Kumar, N.; Petkoska, A.T.; Upadhyay, A. Film Formation and Deposition Methods of Edible Coating on Food Products: A Review. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Saini, C.S. Edible Composite Bi-Layer Coating Based on Whey Protein Isolate, Xanthan Gum and Clove Oil for Prolonging Shelf Life of Tomatoes. Meas. Food 2021, 2, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Zhou, L.; Xu, J.; Jiang, F.; Zhong, Z.; Zou, L.; Liu, W. Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Based Water Barrier Coating Regulated Postharvest Quality and ROS Metabolism of Pakchoi (Brassica Chinensis L.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 185, 111804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, Z.; Bi, Y.; Zong, Y.; Gong, D.; Wang, B.; Li, B.; Sionov, E.; Prusky, D. The Effect of Environmental pH during Trichothecium Roseum (Pers.:Fr.) Link Inoculation of Apple Fruits on the Host Differential Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, C.; Jiang, L.; An, X.; Yu, M.; Xu, Y.; Ma, R.; Yu, Z. Potential Role of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Genes in the Regulation of Peach Fruit Development and Ripening. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 104, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, R.L.; Cabral, M.F.; Germano, T.A.; de Carvalho, W.M.; Brasil, I.M.; Gallão, M.I.; Moura, C.F.H.; Lopes, M.M.A.; de Miranda, M.R.A. Chitosan Coating with Trans-Cinnamaldehyde Improves Structural Integrity and Antioxidant Metabolism of Fresh-Cut Melon. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 113, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Ma, C.; Cheng, S.; Wei, B.; Liu, X.; Ji, S. Changes in Antioxidative Metabolism Accompanying Pitting Development in Stored Blueberry Fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 88, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.; Zuo, J.; Zheng, Q.; Guo, L.; Gao, L.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Q.; Hu, W. Red LED Irradiation Maintains the Postharvest Quality of Broccoli by Elevating Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Reducing the Expression of Senescence-Related Genes. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 251, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.-J.; Zhang, B.; Yan, H.; Feng, J.-T.; Ma, Z.-Q.; Zhang, X. Effect of Lotus Leaf Extract Incorporated Composite Coating on the Postharvest Quality of Fresh Goji (Lycium Barbarum L.) Fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 148, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhang, K.; Liu, S. Evaluation of 1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) and Low Temperature Conditioning (LTC) to Control Brown of Huangguan Pears. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 259, 108738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wei, L.; Li, C.; Cai, G.; Zhu, T. Combined Effects of Ultrasound and Aqueous Chlorine Dioxide Treatments on Nitrate Content during Storage and Postharvest Storage Quality of Spinach (Spinacia Oleracea L.). Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, Q. Exogenous Melatonin Delays Postharvest Fruit Senescence and Maintains the Quality of Sweet Cherries. Food Chem. 2019, 301, 125311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Tang, Q.; Li, C.; Duan, B.; Li, X.; Wei, M.; Li, J. Acibenzolar-S-Methyl Treatment Enhances Antioxidant Ability and Phenylpropanoid Pathway of Blueberries during Low Temperature Storage. LWT 2019, 110, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meitha, K.; Pramesti, Y.; Suhandono, S. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidants in Postharvest Vegetables and Fruits. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, e8817778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbdellaoui, M.; Bouhlali, E.; Bouhlali, E.d.T.; Rhaffari, L.E. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activities of the Essential Oils of Cumin (Cuminum Cyminum) Conducted Under Organic Production Conditions. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2019, 22, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, B.; Wu, S.; Siddiqui, M.W. Incorporating Essential Oils or Compounds Derived Thereof into Edible Coatings: Effect on Quality and Shelf Life of Fresh/Fresh-Cut Produce. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Garcia, I.; Cruz-Valenzuela, M.R.; Silva-Espinoza, B.A.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A.; Moctezuma, E.; Gutierrez-Pacheco, M.M.; Tapia-Rodriguez, M.R.; Ortega-Ramirez, L.A.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F. Oregano (Lippia Graveolens) Essential Oil Added within Pectin Edible Coatings Prevents Fungal Decay and Increases the Antioxidant Capacity of Treated Tomatoes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 3772–3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Lu, M.; Wang, S. Effect of Oligosaccharides Derived from Laminaria Japonica-Incorporated Pullulan Coatings on Preservation of Cherry Tomatoes. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmai, W.N.S.M.; Latif, N.S.A.; Zain, N.M. Efficiency of Edible Coating Chitosan and Cinnamic Acid to Prolong the Shelf Life of Tomatoes. J. Trop. Resour. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 7, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, R.M.; Nair, B.R. Improvement of Shelf Life Quality of Tomatoes Using a Novel Edible Coating Formulation. Plant Sci. Today 2019, 6, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfoudhi, N.; Hamdi, S. Use of Almond Gum and Gum Arabic as Novel Edible Coating to Delay Postharvest Ripening and to Maintain Sweet Cherry (P Runus Avium) Quality during Storage: Almond Gum as Novel Edible Coating. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 1499–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmu, S.B.; Mishra, H.N. The Effect of Edible Coating Based on Arabic Gum, Sodium Caseinate and Essential Oil of Cinnamon and Lemon Grass on Guava. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, G.; Muda Mohamed, M.T.; Ali, A.; Ding, P.; Ghazali, H.M. Effect of Gum Arabic Coating Combined with Calcium Chloride on Physico-Chemical and Qualitative Properties of Mango (Mangifera Indica L.) Fruit during Low Temperature Storage. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 190, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maringgal, B.; Hashim, N.; Mohamed Amin Tawakkal, I.S.; Muda Mohamed, M.T. Recent Advance in Edible Coating and Its Effect on Fresh/Fresh-Cut Fruits Quality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 96, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, A.; Génard, M.; Lobit, P.; Mbeguié-A-Mbéguié, D.; Bugaud, C. What Controls Fleshy Fruit Acidity? A Review of Malate and Citrate Accumulation in Fruit Cells. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1451–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshetu, A.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Forsido, S.F.; Kuyu, C.G. Effect of Beeswax and Chitosan Treatments on Quality and Shelf Life of Selected Mango (Mangifera Indica L.) Cultivars. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruelas-Chacon, X.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Montañez, J.; Aguilera-Carbo, A.F.; Reyes-Vega, M.L.; Peralta-Rodriguez, R.D.; Sanchéz-Brambila, G. Guar Gum as an Edible Coating for Enhancing Shelf-Life and Improving Postharvest Quality of Roma Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.). J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, e8608304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Zheng, H.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Jin, T.; Liu, S.; Zheng, L. UV-C Treatment Enhances Organic Acids and GABA Accumulation in Tomato Fruits during Storage. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 128126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Li, F.; Zhang, X. Combined Effects of 1-Methylcyclopropene and Tea Polyphenols Coating Treatment on the Postharvest Senescence and Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism of Bracken (Pteridium Aquilinum Var. Latiusculum). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 185, 111813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Wang, X. Guar Gum and Ginseng Extract Coatings Maintain the Quality of Sweet Cherry. LWT 2018, 89, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.M.B.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Ghaderi Ghahfarrokhi, M.; Eş, I. Basil-Seed Gum Containing Origanum Vulgare Subsp. Viride Essential Oil as Edible Coating for Fresh Cut Apricots. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 125, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, M.S.; Ejaz, S.; Hussain, S.; Ali, S.; Sardar, H.; Azam, M.; Ullah, S.; Khaliq, G.; Saleem, M.S.; Nawaz, A.; et al. Synergistic Effect of Gum Arabic and Carboxymethyl Cellulose as Biocomposite Coating Delays Senescence in Stored Tomatoes by Regulating Antioxidants and Cell Wall Degradation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 201, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, H.; Xu, Y.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Multiple 1-MCP Treatment More Effectively Alleviated Postharvest Nectarine Chilling Injury than Conventional One-Time 1-MCP Treatment by Regulating ROS and Energy Metabolism. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; An, L.; Du, M.; Tian, Y. Effect of Polysaccharide Derived from Osmunda Japonica Thunb-Incorporated Carboxymethyl Cellulose Coatings on Preservation of Tomatoes. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e14239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Lin, H.; Fan, Z.; Wang, H.; Lin, M.; Chen, Y.; Hung, Y.-C.; Lin, Y. Inhibitory Effect of Propyl Gallate on Pulp Breakdown of Longan Fruit and Its Relationship with ROS Metabolism. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 168, 111272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Gu, X.; Zhao, L.; Li, B.; Wang, K.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, H. Pichia Caribbica Improves Disease Resistance of Cherry Tomatoes by Regulating ROS Metabolism. Biol. Control 2022, 169, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Lei, B.; et al. Citral Induces Plant Systemic Acquired Resistance against Tobacco Mosaic Virus and Plant Fungal Diseases. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 183, 114948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechowiak, T.; Grzelak-Błaszczyk, K.; Sójka, M.; Skóra, B.; Balawejder, M. Quality and Antioxidant Activity of Highbush Blueberry Fruit Coated with Starch-Based and Gelatine-Based Film Enriched with Cinnamon Oil. Food Control 2022, 138, 109015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banani, H.; Olivieri, L.; Santoro, K.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L.; Spadaro, D. Thyme and Savory Essential Oil Efficacy and Induction of Resistance against Botrytis Cinerea through Priming of Defense Responses in Apple. Foods 2018, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Cai, Z.; Ba, L.; Qin, Y.; Su, X.; Luo, D.; Shan, W.; Kuang, J.; Lu, W.; Li, L.; et al. Maintenance of Postharvest Quality and Reactive Oxygen Species Homeostasis of Pitaya Fruit by Essential Oil P-Anisaldehyde Treatment. Foods 2021, 10, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, H.; Sun, Q. Preparation of Crosslinked Active Bilayer Film Based on Chitosan and Alginate for Regulating Ascorbate-Glutathione Cycle of Postharvest Cherry Tomato (Lycopersicon Esculentum). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 130, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).