Submitted:

25 June 2023

Posted:

26 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experiment Location

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sampling and Analysis

2.4. Agronomical Analysis

2.5. Microbiological Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

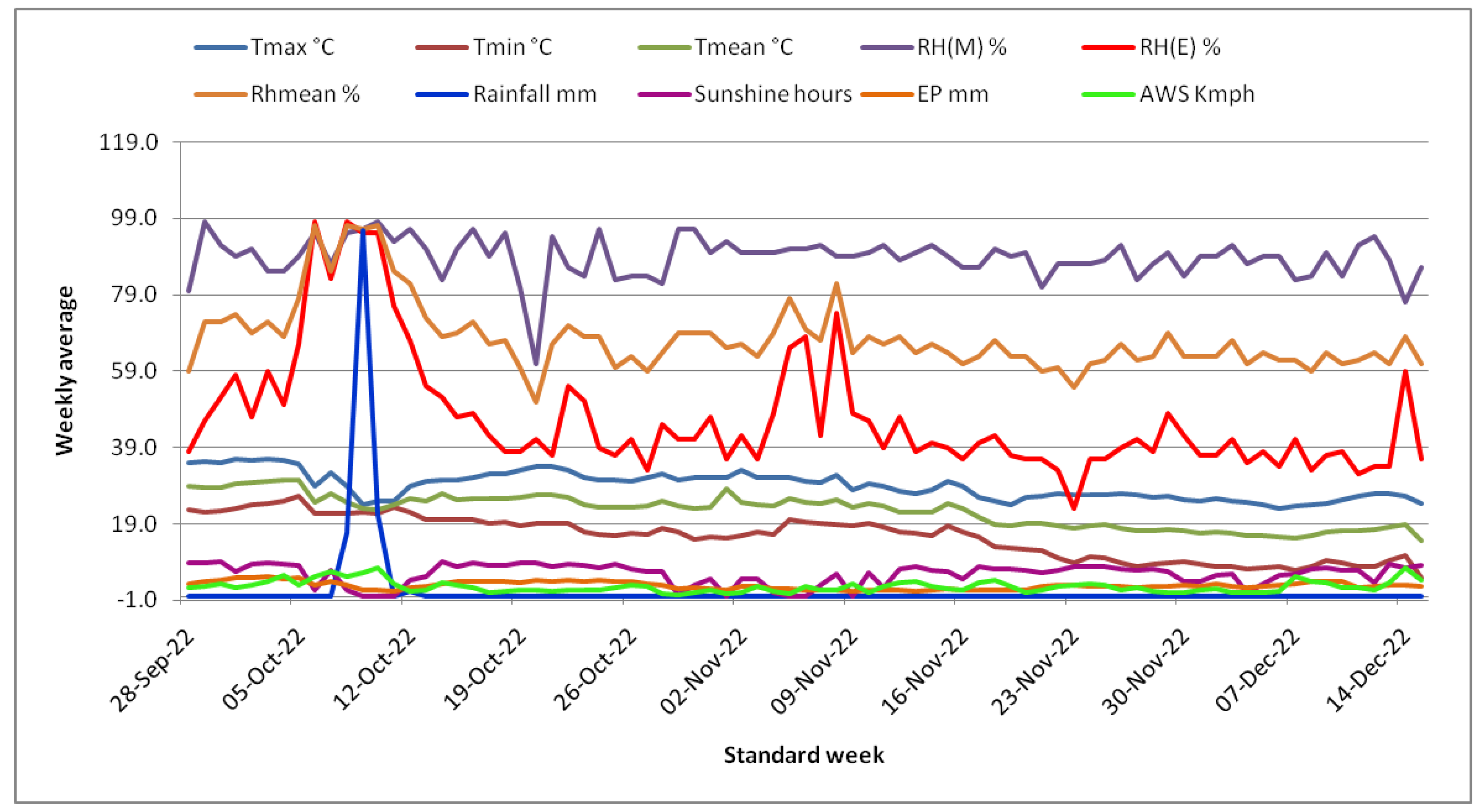

3.1. Weather conditions

| Parameters | Before filtration | After filtration |

|---|---|---|

| EC (ds /cm) | 1.84 | 1.46 |

| pH | 8.518 | 7.62 |

| Turbidity (NTU) | 639 | 199 |

| Total Nitrogen (mg/l) | 22303 | 78.25 |

| Total Phosphorous (mg/l) | 9834 | 45.23 |

| Total Potassium (mg/l) | 2899 | 39.65 |

| Soil parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Physical properties | |

| particle size distribution | |

| Sand (%) | 71 |

| Silt (%) | 14 |

| Clay(%) | 15 |

| Textural class | Sandy Loam |

| Bulk density (g/cc) | 1.52 |

| Mean Weight Diameter | 0.98 |

| Geometric Weight Diameter | 0.54 |

| Chemical properties | |

| Macro nutrients | |

| Available Nitrogen (kg/ha) | 125.66 |

| Available Phosphorous (kg/ha) | 26.55 |

| Available Potassium (kg/ha) | 281.41 |

| Organic Carbon (%) | 0.43 |

| pH | 7.21 |

| EC | 0.29 |

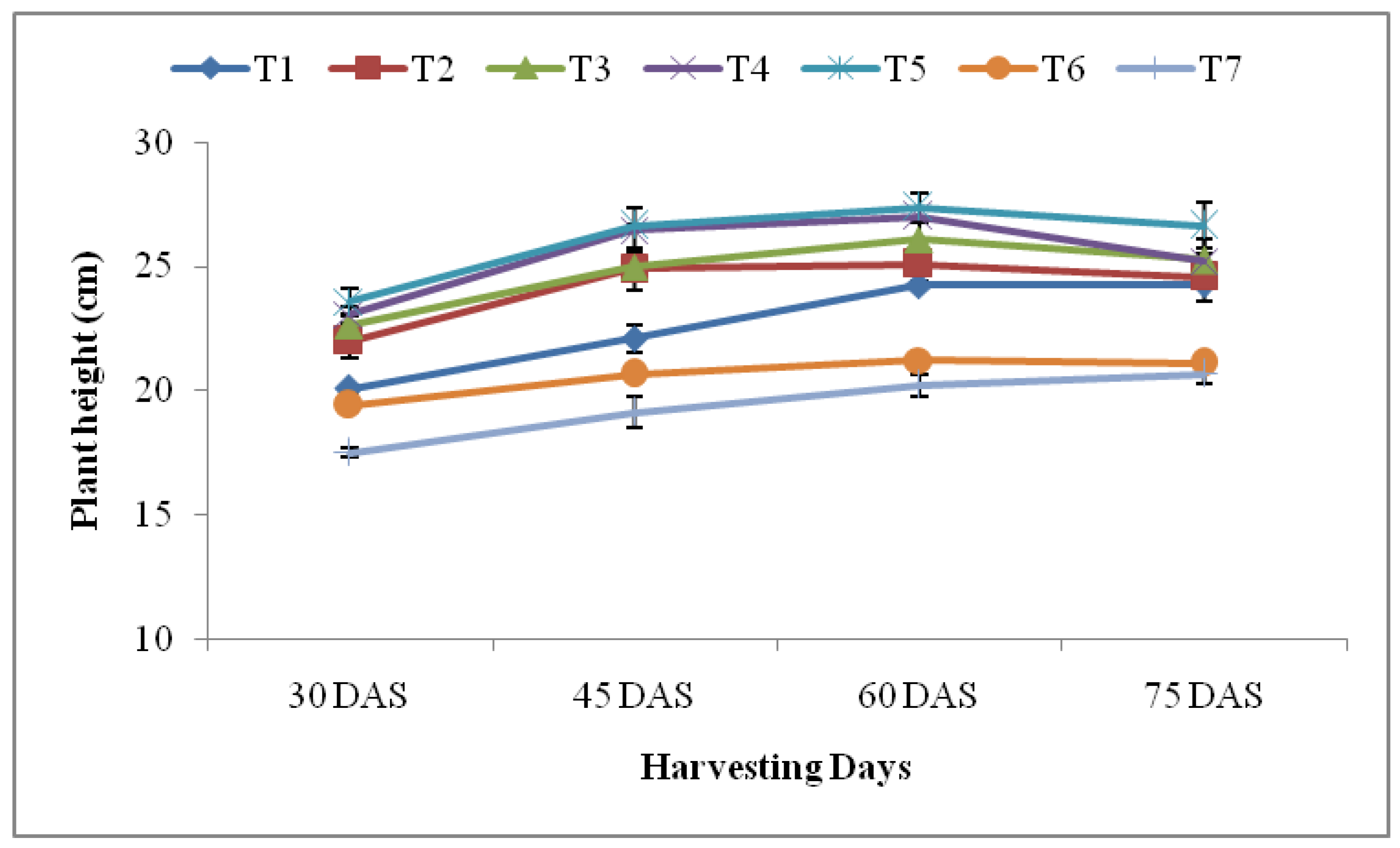

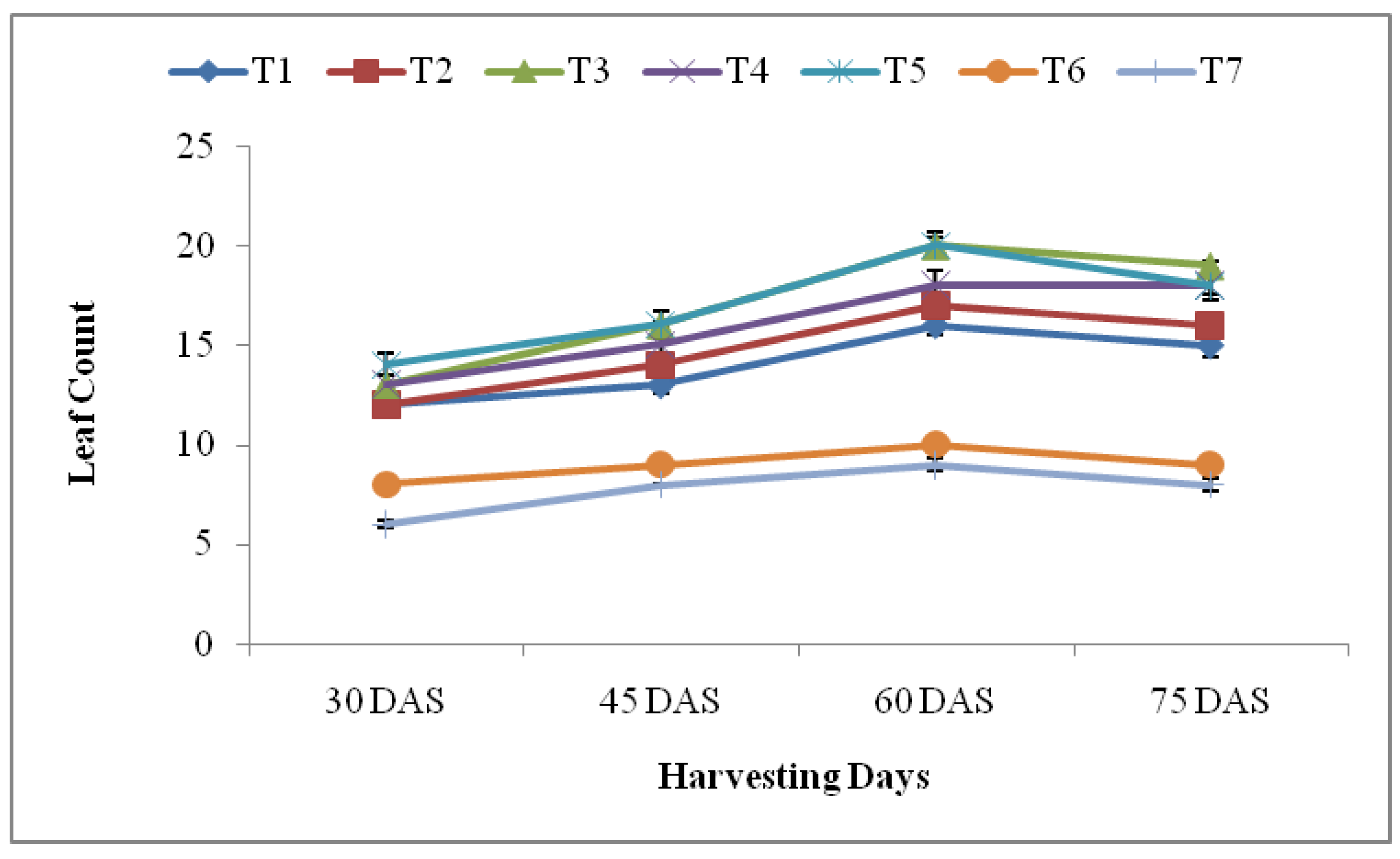

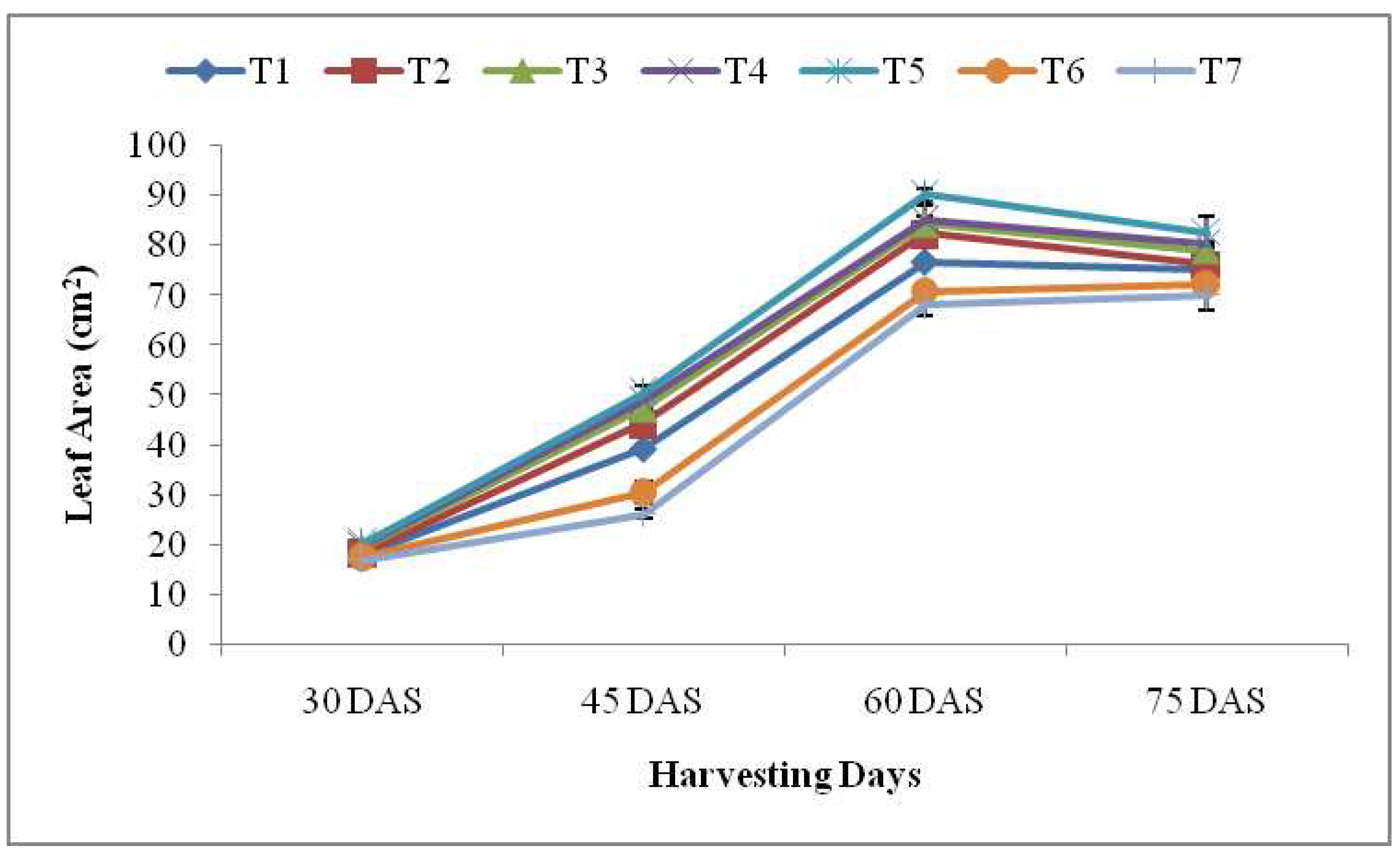

3.2. Spinach growth

3.2.1. Plant height

3.2.2. Leaf Count

3.2.3. Leaf Area

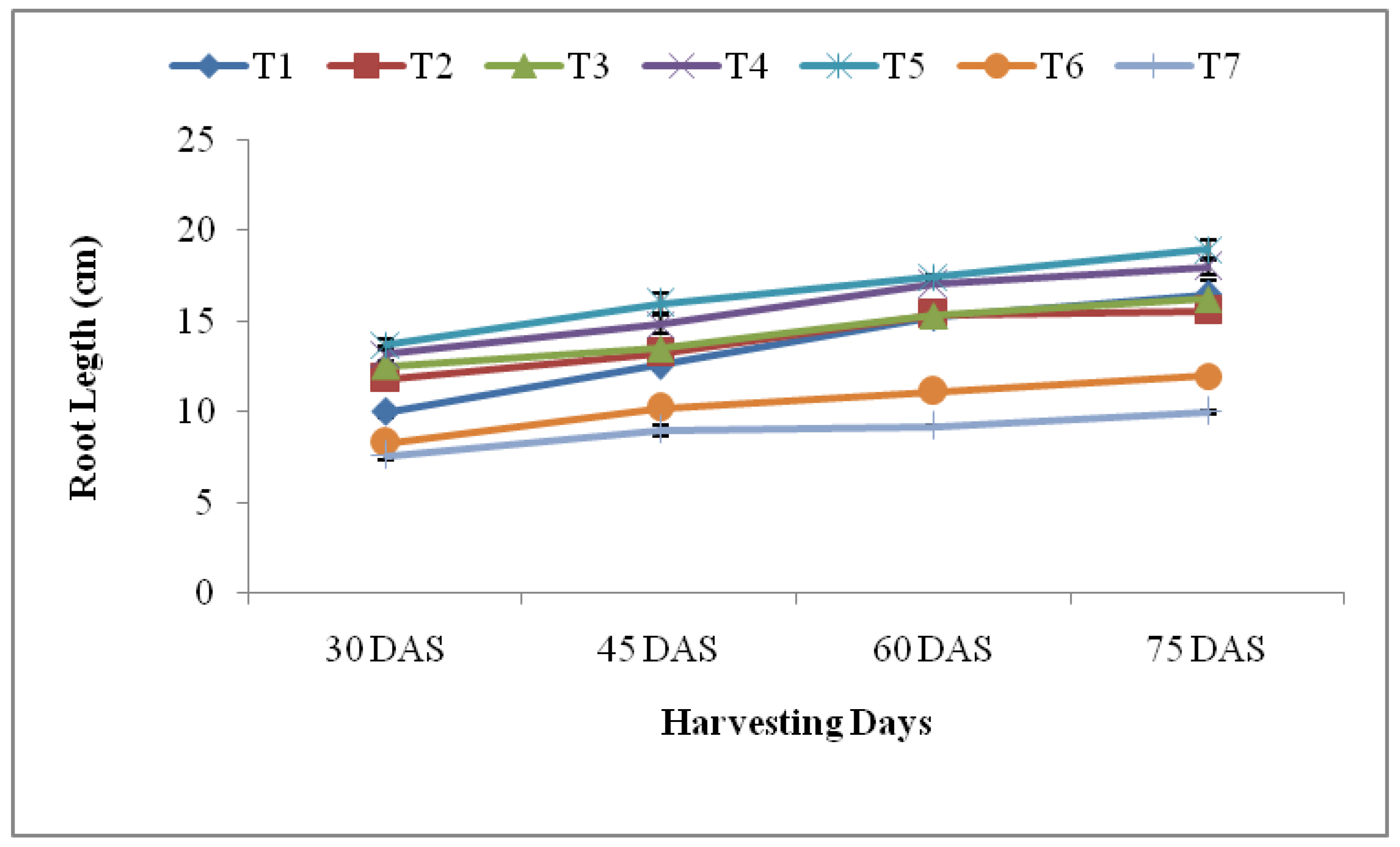

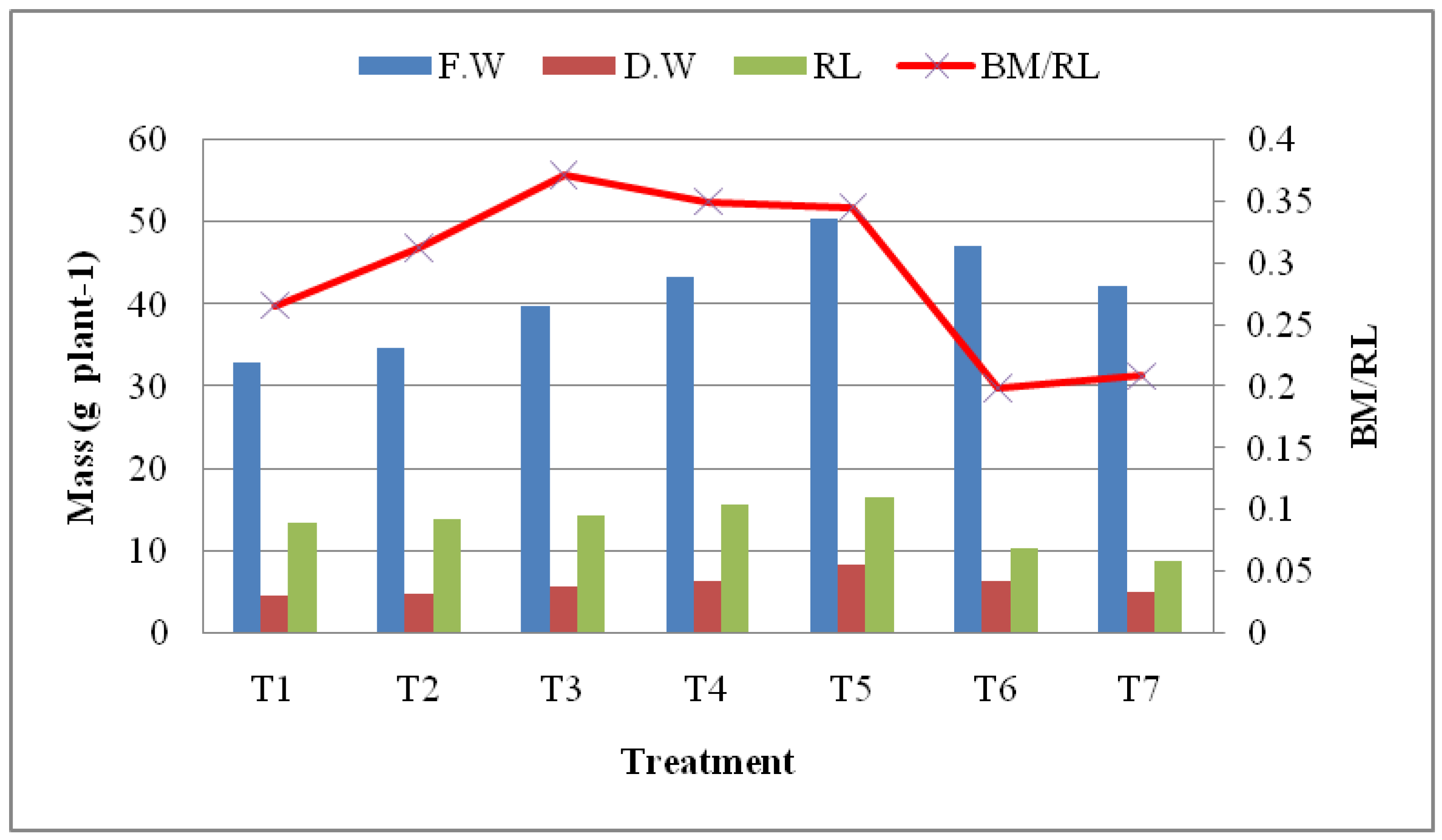

3.2.4. Root Length and Biomass

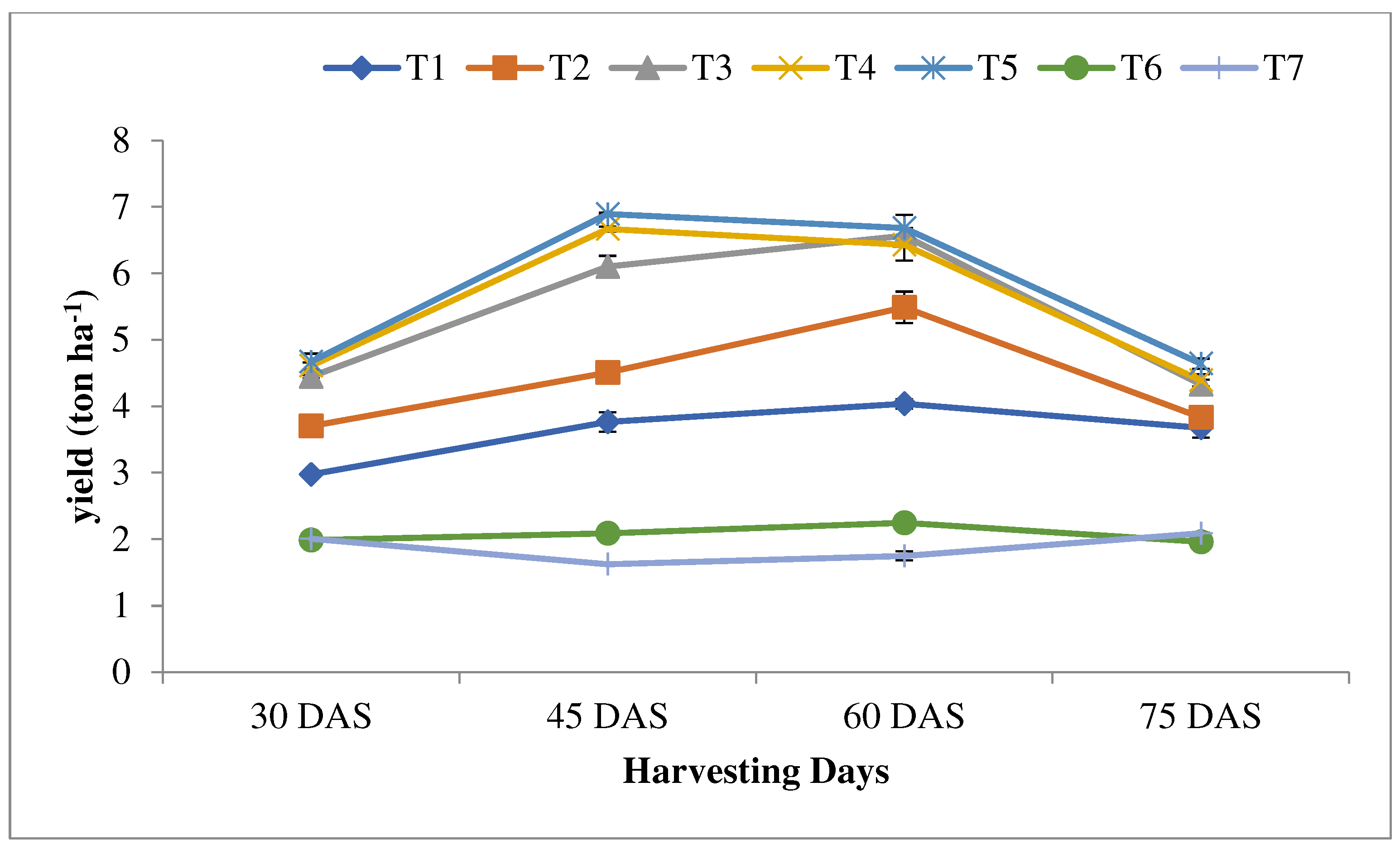

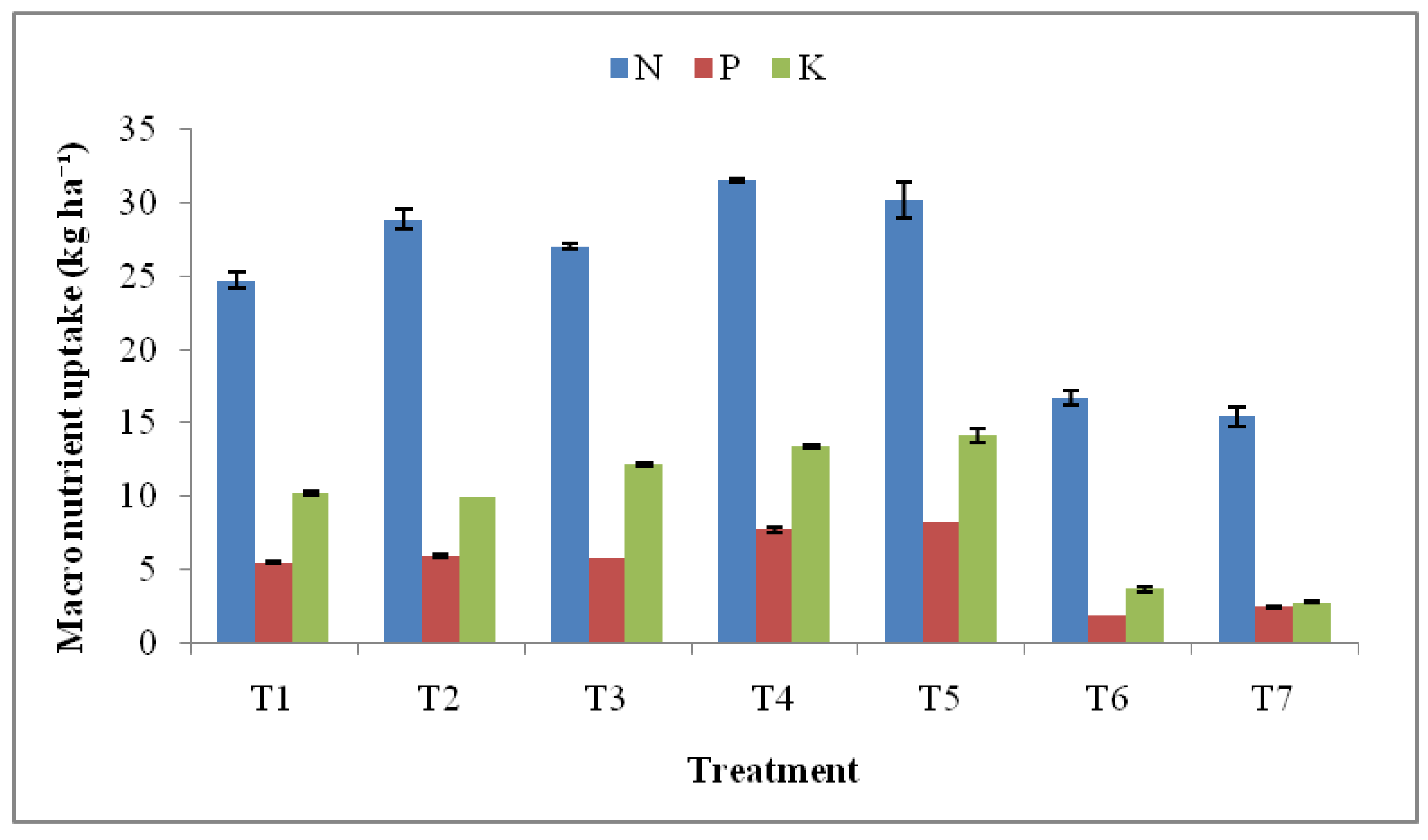

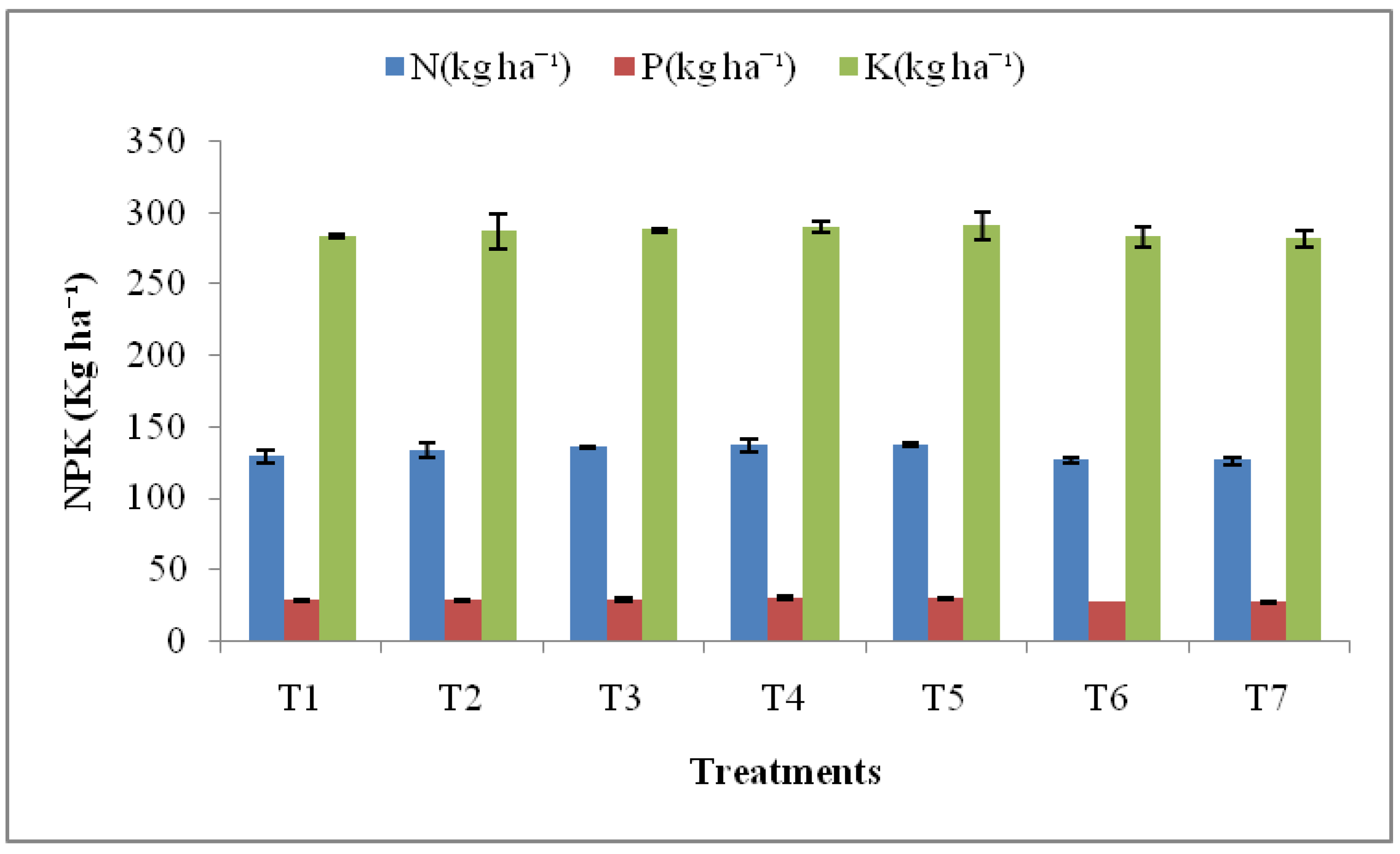

3.3. Spinach nutrient uptake

3.4. Effect on soil

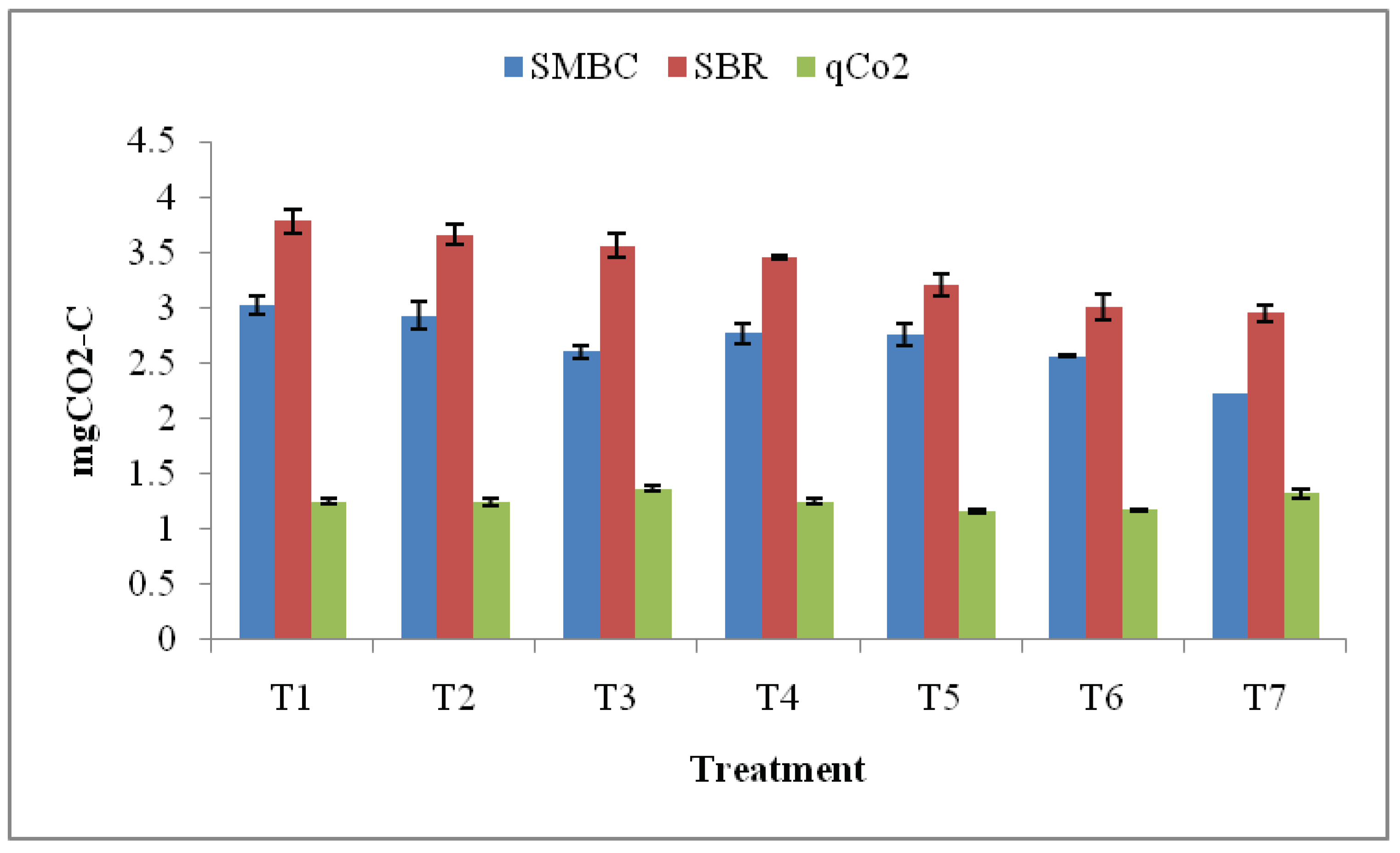

3.5. Microbiological parameters

| Treatment | Mean Dehydrogenase (μg TPF formed g -1 soil h-1) | Mean Alkaline Phosphatase (μg PNP formed g-1 soil h-1) | Mean Acid Phosphatase (μg PNP formed g-1 soil h-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (BSN) | 0.780 | 68.53 | 86.45 |

| T2 (40% RDF+BSN) | 0.760 | 58.68 | 79.85 |

| T3(60% RDF+BSN) | 0.798 | 60.18 | 77.35 |

| T4(80% RDF+BSN) | 0.807 | 57.87 | 79.69 |

| T5(100% RDF) | 0.610 | 57.22 | 78.71 |

| T6 ( Slurry Broadcasting) | 0.747 | 52.73 | 70.61 |

| T7 (Control) | 0.712 | 44.38 | 62.73 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. In 20th Edn. American Public Health Association; American Water Works Association and Water Environmental Federation: Washington, DC, 1998.

- Baral, K.R.; Labouriau, R.; Olesen, J.E.; Petersen, S.O. Nitrous oxide emissions and nitrogen use efficiency of manure and digestate applied to spring barley. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 239, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, D.B.P.; Nabel, M.; Jablonowski, N.D. Biogas-digestate as nutrient source for biomass production of Sida hermaphrodita, Zea mays L. and Medicago sativa L. J. Energy Proc. 2014, 59, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharad, S.G.; Korde, S.D.; Pravina, S.; Baviskar, M.N. Effect of organic manure and number of cutting on growth, yield and quality of Indian spinach. Asian, J. Hort. 2013, 8, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, M.; Gautam, B.; Sarma, P.K.; Hazarika, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; M, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Goswami, R.K.; Kakati, N. Effect of organic sources of nutrients on growth yield and quality of spinach beet( Beeta vulgaris var bengalensis Hort.)cv All Green. Trends. Biosci. 2017, 10, 1490–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Blaha, L. The importance of root -shoot ratio for crops production. HSOA J. Agron. Agric. Sci. 2019, 2, 012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BP energy outlook. BP Energy Economics. 2018. Available online: https:// www.bp.com/energyoutlook.

- Casida L.E., Jr.; Klein, D.A.; Santoro, T. Soil dehydrogenase activity. Soil Science 1964, 98, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J. Effects of different harvest start times on leafy vegetables (Lettuce, Pak Choi and Rocket) in a reaping and regrowth system. 2008.

- Głowacka, A.; Szostak, B.; Klebaniuk, R. Effect of Biogas digestate and mineral fertilisation on the soil properties and yield and nutritional value of switchgrass forage. Agron. J. 2020, 10, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; An, Y.J.; Hwang, J.; Kim, S.B.; Park, B. The effects of organic manure and chemical fertiliser concentrations of yellow poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera Lin.) in a nursery system. Journal of forest science and technology 2016, 12, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.L. Soil Chemical Analysis; Prentice Hall of India Pvt., Ltd.: New Delhi, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, M.K.; Jana, J.C. Evaluation of vermicompost and farmyard manure in nutrient management of spinach (Beta vulgaris var. bengalensis). Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2009, 79, 538–541. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, M.Y.; Azad, A.K.; Hasan, M.K.; Nasreen, A.; Naher, Q.; Baset, M.A. Effect of Plant Spacing and Sources of Nutrients on the Growth and Yield of Cabbage. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 2002, 5, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Suller, L.; Provolo, G.; Brennan, D.; Howlin, T.; Carton, O.T.; Lalor, S.T.J.; Richards, K.G. A note on the estimation of nutrient value of cattle slurry using easily determined physical and chemical parameters. Irish Journal of Agricultural Food Research 2010, 49, 93–97. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11019/171.

- Moller, K.; Muller, T. Effects of anaerobic digestion on digestate nutrient availability and crop growth: a review. Eng. Life Sci. 2012, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Q.A.; Edwardsa, C.A.; Biermanb, P.; Metzgerc, J.D.; Lucht, C. Effects of vermicomposts produced from cattle manure, food waste and paper waste on the growth and yield of peppers in the field. Pedobiologia 2005, 49, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, O.E.; Fortuna, A.M.; Harrison, J.H.; Whitefield, E.; Cogger, C.G.; Kennedy, A.C.; Bary, A.I. Comparison of raw dairy manure slurry and an aerobically digested slurry as N sources for grass forage production. Int. J. Agron. 2012, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preetha, D. Biotic enrichment of organic wastes from ayurveda prepareation. M.Sc (Ag); Kerla Agriculture University: Thrissur, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Purbajanti, E.D.; Slamet, W.; Fuskhah, E. Rosiyda Effects of organic and inorganic fertilizers on growth, activity of nitrate reductase and chlorophyll contents of peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2019, 250, 12048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Gica, R.B.; Yost, R.S.; Porter, G. Biomass production and nutrient removal by tropical grasses subsurface drip-irrigated with dairy effluent. Grass Forage Sci. 2012, 67, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.N.; Pathak, H.; Das, D.K.; Tomar, R.K. Use of flyash and biogas slurry for improving wheat yield and physical properties of soil. J. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2005, 107, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.H.; Seomun, S.; Choi, Y.D.; Jang, G. Root development and stress tolerance in rice: the key to improving stress tolerance without yield penalties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Agarwal, S. Impact of organic fertilizers on growth, yield and quality of spinach beet. Indian Journal of Plant Sciences 2014, 3, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, A.; Moyer, B. Phosphorus forms in manure and compost and their release during simulated rainfall. Journal of Environmental Quality 2000, 29, 1462–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, N.; Taube, F.; Wienforth, B.; Kluß, C.; Kage, H.; Herrmann, A. Nitrogen leaching losses after biogas residue application to maize. Soil &TillageRes. 2013, 130, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabai, M.A. Soil Enzymes. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2 Microbiological and Biochemical Properties; Page, A.L., Ed.; The American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, 1994; pp. 775–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehlan, S.K.; Thakral, K.K. Effect of different levels of nitrogen and leafcutting on leaf and seed yield of coriander (Coriandrum sativum). J. Spices.Aromat.Crops. 2008, 17, 180–182. Available online: https://updatepublishing.com/journal/index.php/josac/article/view/4915.

- Tiang, J.; Bryks, B.C.; Yada, R.Y. Feeding the world into the future–food and nutrition security: the role of food science and technology. Front. Life Sci. 2016, 9, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. N. Transforming Our World; The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; U.N.: New York, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.Q. Biogas Technology and Application; Chemical Industry Press: Beijing, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).