1. Introduction

The velvetbean caterpillar,

Anticarsia gemmatalis (Hübner, 1818) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae), is one of the main species of the soybean pest complex [

1,

2]. It causes major economic damage to this crop across the Americas [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The main strategies employed to control

A. gemmatalis outbreaks rely on the use of synthetic insecticides, a range of selective or biorational products and the cultivation of transgenic plants expressing Bt insecticidal proteins [

5,

6,

7,

8].

The Anticarsia gemmatalis multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AgMNPV) (

Baculoviridae:

Alphabaculovirus), a natural pathogen of this pest, has played a significant role in integrated pest control programs, and was applied over ~2 million hectares annually in the early 2000s. The high pathogenicity of the virus results in the control of this pest below economic thresholds following a single application of virus occlusion bodies (OBs) to soybean crops [

9]. However, the use of AgMNPV-based insecticides has been drastically reduced over the past decade due to the widespread adoption of transgenic soybean [

10,

11,

12].

In nature, nucleopolyhedroviruses exist as heterogeneous populations composed of different genotypes [

13,

14]. Genotypic variants arise from random molecular events involving recombination, insertion, duplication, the deletion of genomic sequences or horizontal gene transfer [

15,

16]. Some of these variations confer distinct insecticidal properties, usually measured in terms of OB pathogenicity metrics, speed of kill and OB production, which can directly influence virus survival and transmission between susceptible hosts [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

Intraspecific genotypic diversity and phenotypic variation has been described among geographical isolates of a wide array of alphabaculovirus species [

19,

21,

22,

23]. Characterization of the genotypic variants present in a wild-type isolate has proved to be important for the selection and development of some of these variants as the active ingredients of virus-based insecticides [

24,

25,

26].

Indeed, the prototype AgMNPV-2D, is a majority variant present AgMNPV formulations against

A. gemmatalis [

27], was originally identified by plaque purification of a wild type isolate from Brazil [

28,

29]. However, from field experiences in other host-virus systems [

30,

31,

32], access to a range of highly insecticidal genotypic variants is important in case of isolate-dependent host resistance [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Variants can also differ in their OB production traits, which lend some variants to be more amenable than others to mass-production processes necessary for the commercialization of virus insecticides [

37].

In this study, we compared several natural isolates of AgMNPV and characterized the genotypic variants present in the most pathogenic isolate, with the aim of comparing the insecticidal traits of the individual variants with those of commercial products that were previously available against A. gemmatalis. Specifically, comparative molecular and biological analyses of three AgMNPV isolates resulted in the selection of one of them, from which eighteen genotypic variants were obtained and characterized in terms of OB pathogenicity, speed-of-kill, and OB productivity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insects, cells and virus isolates

The

Anticarsia gemmatalis population was established from larvae collected in soybean fields of Tamaulipas, Mexico and maintained at 25 ± 1 °C, 75% relative humidity and 16 h light: 8 h dark photoperiod on a wheatgerm-based semi-synthetic diet [

38].

Sf9 cells (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) were maintained in Sf-900 II medium (Gibco) at 28 °C.

The Anticarsia gemmatalis multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AgMNPV) isolates used in this study were AgMNPV-30WT (hereinafter known as Ag30WT) isolated in Mexico [

21], and AgMNPV-ABB15 (AgABB15) and AgMNPV-ABB51 (AgABB51), which both originated from the virus collection of the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA), France and were kindly provided by Miguel López-Ferber. These INRA isolates were likely to have been deposited during the studies on AgMNPV by Crozier and Ribeiro [

16]. OBs were amplified in fourth instars of

A. gemmatalis and purified by homogenization of each virus-killed larva in 1 mL of 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) followed by filtration through muslin and centrifugation at 2400

g for 5 min to eliminate insect debris. The resulting pellets were washed and resuspended in 2 vol. milli-Q water. Purified OB suspensions were titrated under phase-contrast microscopy at x400 using an improved hemocytometer (Paul Marienfeld GmbH, Lauda-Königshofen, Germany) and aliquots of each isolate were stored at -20 °C until required.

Unless otherwise stated, all bioassays and related procedures described in the following sections were performed at 25 °C, 75% relative humidity, 16 h light: 8 h dark photoperiod.

2.2. DNA extraction from OBs

Occlusion derived virions (ODVs) were released by incubating 40 µL of OB suspension (1010 OBs/mL) with 100 µL of 0.5 M Na2CO3 and 360 µL distilled water at 60 °C for 30 min. A supernatant containing the released virions was obtained by centrifugation at 5900 g for 5 min and immediately transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube and incubated with 25 µL 10% SDS, 25 µL 0.5 M EDTA and 15 µL proteinase K (20 mg/mL) at 65 °C for 1 h to degrade the virion membrane and the nucleocapsid and, hence, release the virus genome. Viral DNA was then separated from proteins by adding 150 µL MPC Protein Precipitation Reagent (Epicentre, Illumina Inc., San Diego, California, USA), vortexing vigorously for 10 s, and pelleting the debris by centrifugation at 10000 g and 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube and DNA was pelleted by adding 1 mL ice-cold absolute ethanol and centrifuged at 16200 g at 4 °C for 10 min. The pelleted DNA was washed with 500 µL 70% ethanol, and the DNA resuspended in 50 µL bidistilled water and incubated at 60 °C for 15 min.

2.3. Cloning of genotypic variants

Individual genotypes were obtained from AgABB51 by plaque purification [

39]. A concentration of 10

8 OB/mL was used to inoculate fifth instar

A. gemmatalis larvae by the droplet feeding method [

40]. At 48 h post infection (hpi), infected larvae were bled and hemolymph containing budded virions was collected and stored at -20 °C. Hemolymph was then passed through a 0.45 µm filter and used to prepare six serial dilutions in Sf-900 II (Gibco) medium with antibiotics. A 200 µL volume from each dilution was used to inoculate 5 x 10

5 Sf9 cells (Gibco) and, at 10 d post infection (dpi), clearly separated individual plaques containing individual clones were collected with a sterile Pasteur pipette and diluted in 300 µL Sf-900 II medium. Clones were then injected into the hemocoel of

A. gemmatalis fifth instar larvae that were individually placed in the wells of a cell culture plate with semi-synthetic diet and incubated at 25 °C until death or pupation.

2.4. Viral DNA Restriction Endonuclease Analysis

For restriction endonuclease analysis, 2 µg viral DNA were digested with two units of HindIII (Fast Digest, Thermofisher) for 2 h at 37 °C. DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel immersed in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris, 20 mM acetic acid, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0) running at 18V for 15 h. DNA fragments were stained with GelRed (Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA) and photographed on a transilluminator (Gel Doc EZ Imager, Bio-Rad Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

2.5. Biological activity

The three isolates employed, Ag30WT, AgABB15 and AgABB51, were used to inoculate groups of 28 newly molted second instar larvae of

A. gemmatalis at three different concentrations (10

3, 10

5 and 10

7 OBs/mL) by the droplet feeding method [

40]. Larvae that drank the OB suspensions within 10 min were individualized in wells of a cell culture plate with semi-synthetic diet. Control larvae drank a solution that contained no OBs. These assays were performed in triplicate using different insect batches. Mortality was recorded every 24 hours until all larvae were dead or had pupated.

The pathogenicity of AgABB51 OBs, expressed as the median lethal concentration (LC

50), was determined by the droplet feeding method [

40]. Groups of 28 newly molted second instar larvae were allowed to drink OB suspensions of one of the following concentrations, expected to cause between 10% and 90% mortality: 1.2 x 10

3, 3.7 x 10

3, 1.1 x 10

4, 3.3 x 10

4 and 1.0 x 10

5 OBs/mL. Control larvae drank a solution that contained no OBs. Larvae that drank the OB suspensions within 10 min were individualized in wells of a cell culture plate with semi-synthetic diet and mortality was recorded at 24-h intervals until all larvae had died or pupated. This assay was performed in triplicate with different insect batches. Concentration-mortality data were analyzed by Probit regression to estimate LC

50 values using the software POLO Plus (Leora) [

41].

Median time to death (MTD) was estimated in AgABB51-infected second instar

s that consumed a suspension of 6.8 x 10

4 OBs/mL (estimated to result in ~90% mortality). Larvae that drank the inoculum within 10 min were individualized with semi-synthetic diet and mortality was recorded every 8 h until all larvae had died or pupated. Control larvae consumed a solution without OBs. The study was performed on three batches of insects. In order to estimate MTD values, a survival analysis was performed using the ‘Survival’ package [

42] in R (v4.2.2) [

43]. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was calculated in order to identify the best fitting model.

OB production was determined in fifth instars inoculated with an LC

99 (10

8 OBs/mL) concentration of AgABB51 OBs by the droplet feeding method [

40]. In each of the three biological replicates, dead larvae were collected individually in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube and OBs were purified in a total volume of 1 mL with milli-Q water. OB suspensions from 26 larvae from each replicate were titered in a Neubauer hemocytometer. Data were subjected to a Shapiro-Wilk normality test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test in R (v4.2.2) [

43].

An inoculum concentration equal to the LC

50 of AgABB51 OBs (1.1 x 10

4 OBs/mL) was used to evaluate the mortality response of

A. gemmatalis second instar larvae to each of the genotypic variants isolated in section 2.3. Larvae were inoculated by the droplet feeding method [

40] and incubated individually on semi-synthetic diet in the wells of a cell culture plate. Mortality was registered daily until all individuals were dead or pupated. The bioassay was performed on three batches of insects with appropriate controls. Percentage of mortality values were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test in R (v4.2.2) [

43].

2.6. Genotypic variant selection and biological characterization

The genotypic variants that induced higher mortality responses than the wild-type isolate (AgABB51) were selected for further characterization in terms of LC

50, MTD and OB production as described in section 2.5., whereas MTD values were subjected to a log-rank test using the package ‘Survival’ [

42] and a post hoc Bonferroni-corrected pairwise

t-test. OB production data were subjected to a Shapiro-Wilk normality test and one-way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Tukey HSD test. All analyses were performed using R (v4.2.2) [

43].

3. Results

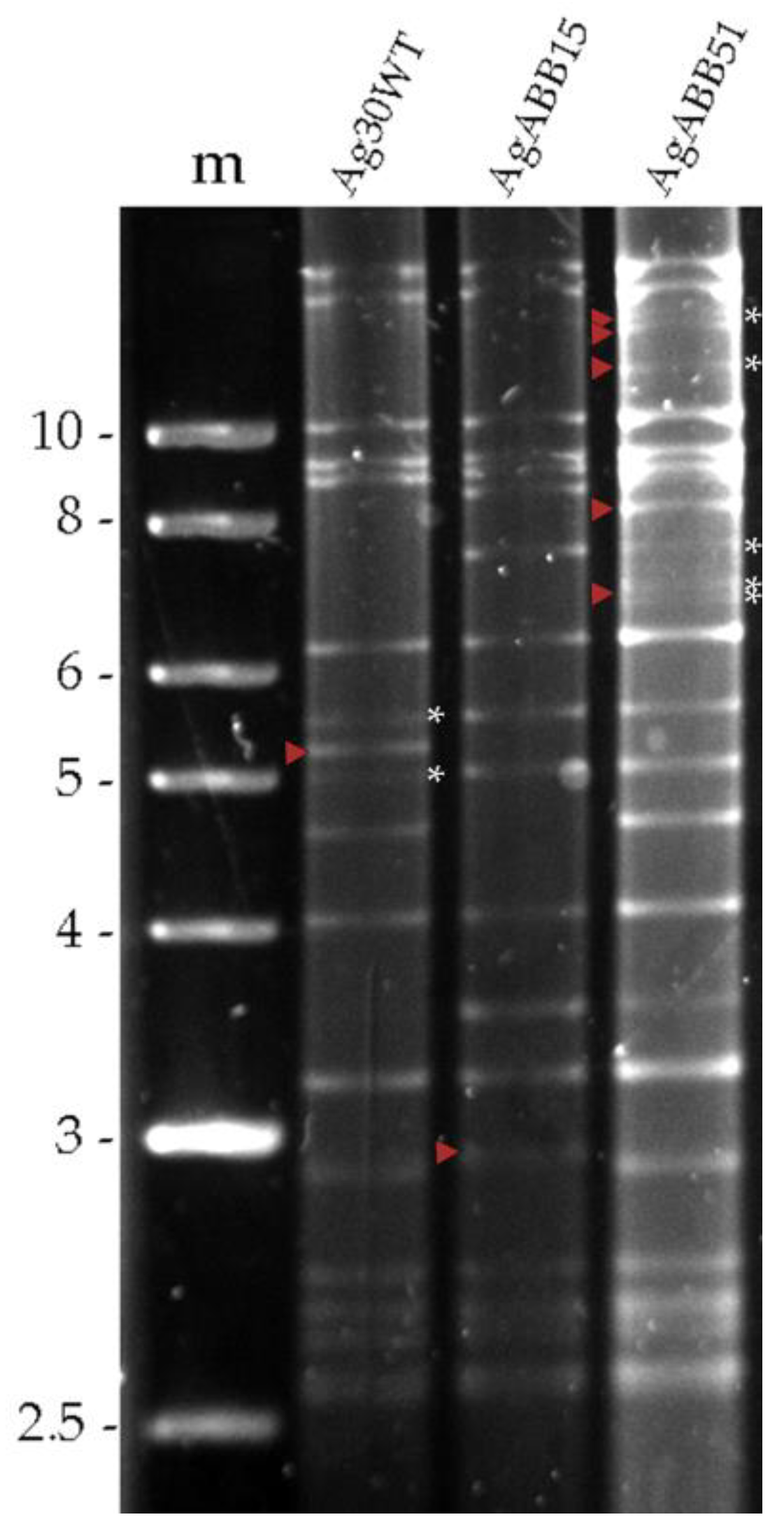

3.1. Identification of AgMNPV isolates by restriction endonuclease analysis

Analysis of the genomic DNA of three different AgMNPV isolates (Ag30WT, AgABB15 and AgABB51) revealed three slightly different REN profiles, as judged by the distinct restriction fragment length polymorphisms (

Figure 1). All the isolates appeared to generate restriction fragments in submolar concentrations, indicating the presence of different genotypic variants within each isolate (

Figure 1).

3.2. Mortality response to AgMNPV isolates

Similar mortality values were observed at the lowest and highest viral concentrations used for the three candidate isolates, but isolate AgABB51 resulted in higher larval mortality at 10

5 OBs/mL (

Table 1). Thus, we selected AgABB51 for further characterization.

3.3. Biological and genotypic characterization of AgABB51

The pathogenicity of AgABB51 OBs, in terms of the LC

50, was estimated at 1.1 x 10

4 OBs/mL. A median time to death value of 138.6 hours post inoculum (hpi) was estimated through a survival analysis using the log-normal model, which was identified as the best fitting model by comparison of distribution-dependent AIC values. The mean OB yield was 1.23 x 10

9 OBs in

A. gemmatalis fifth instars (

Table 2).

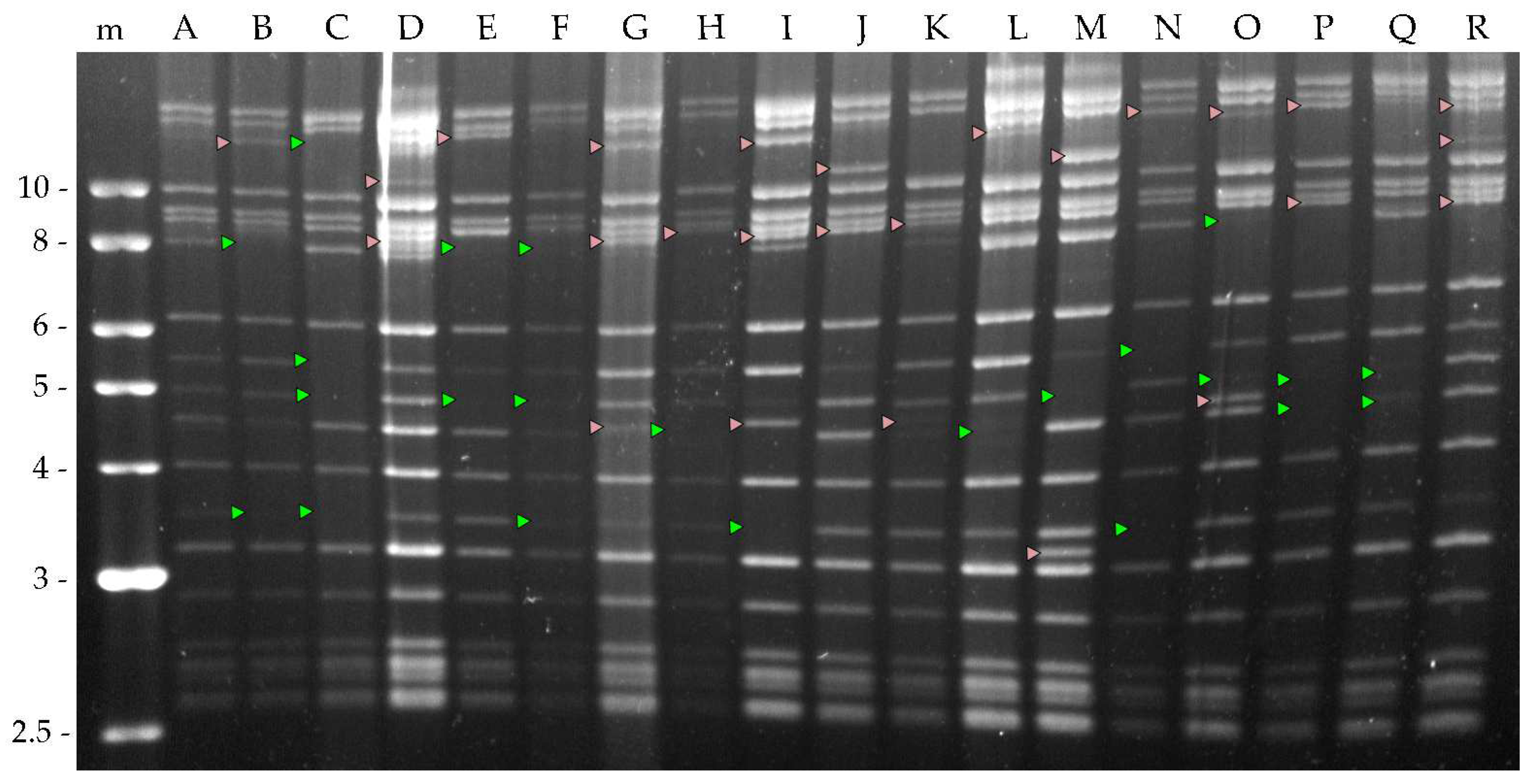

A total of 128 different clones were obtained from the plaque assay and were each amplified by injection into

A. gemmatalis fifth instar larvae. OBs from virus-killed larvae were collected and the viral DNA digested with HindIII to determine differences in their genomic profile. Eighteen different genotypic variants were obtained and named A to R (

Figure 2).

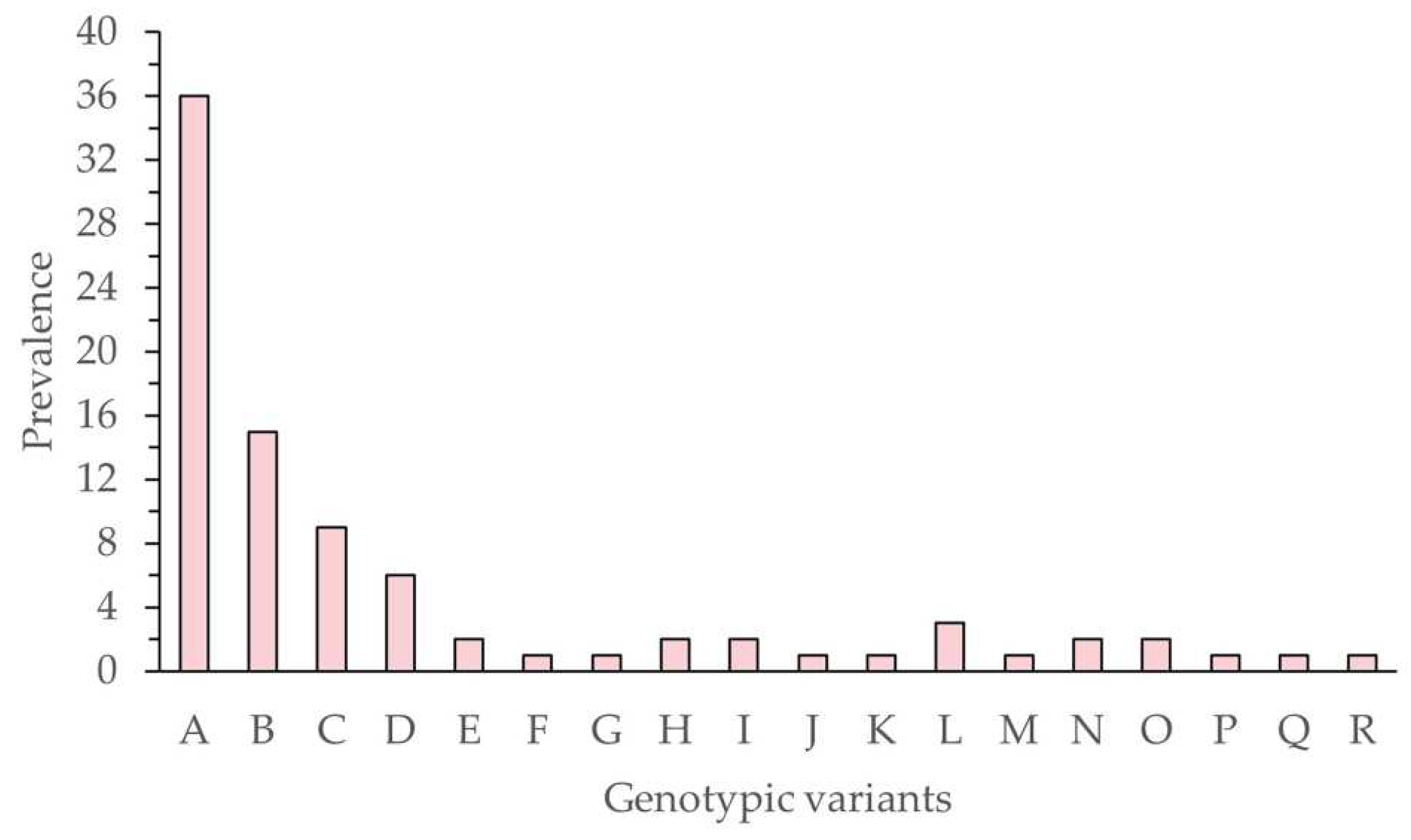

The frequency of each variant was determined as the number of times each characteristic restriction profile was observed in the 128 clones (

Figure 3).

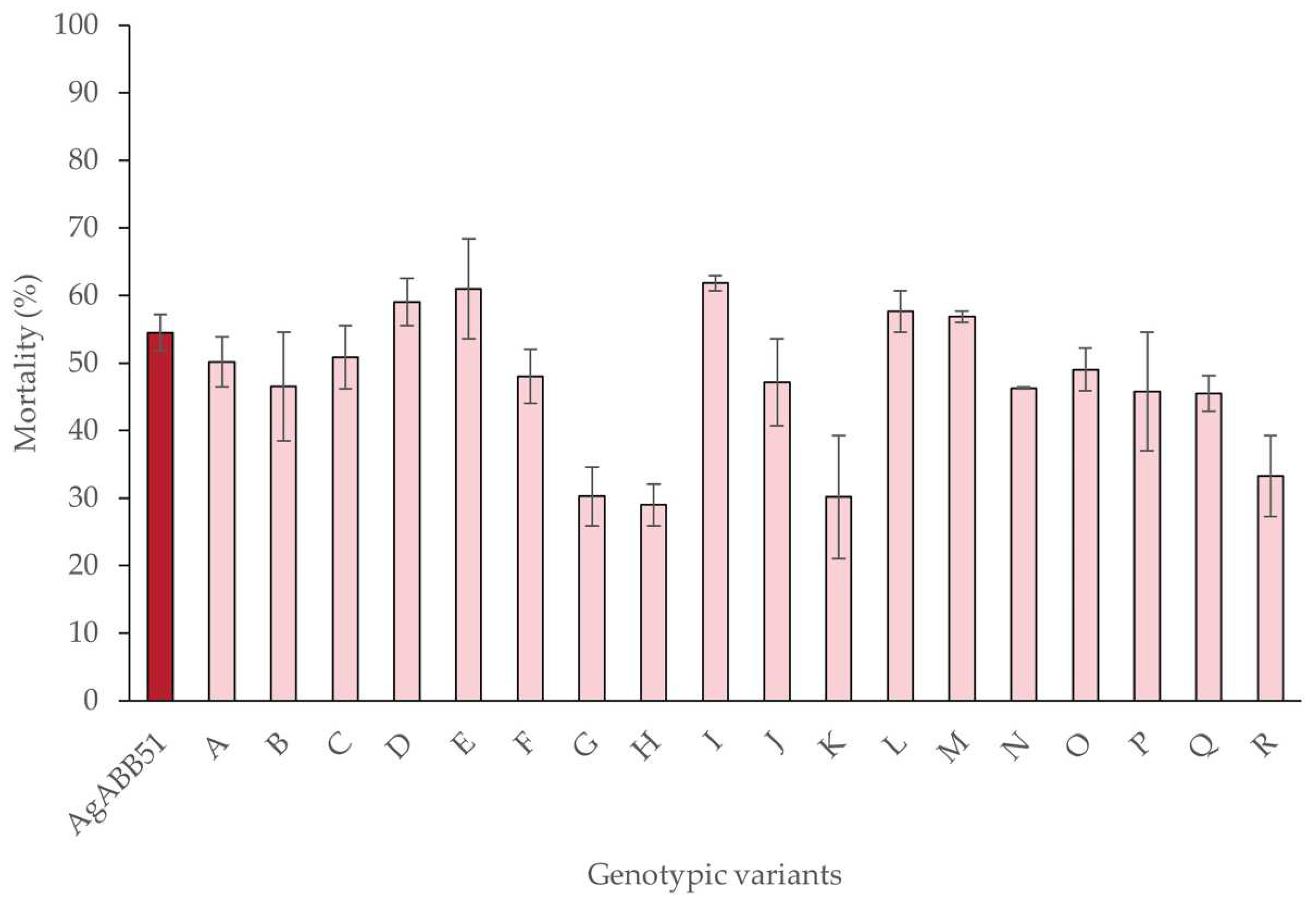

3.4. Biological characterization of AgABB51 genotypic variants

The mean percentage of mortality in larvae inoculated with each of the different genotypic variants and the wild-type AgABB51 varied significantly (χ

2 = 46.99, df = 18, p < 0.005). However, only larvae inoculated with five genotypic variant OBs (D, E, I, L, M) showed higher mortalities than larvae inoculated with AgABB51 OBs in the initial bioassays, at the concentration equal to the LC

50 of AgABB51 (1.1 x 10

4 OBs/mL). All five of these variants were selected for further characterization (

Table 3). Of these, variants E and I caused the highest mean (± SE) larval mortalities of 61.0 ± 7.4% and 61.8 ± 1.1%, respectively.

The pathogenicity of AgABB51 and the five selected genotypic variants ranged from 1 x 10

4 OBs/mL (AgABB51) to 7.6 x 10

3 OBs/mL (variant I), there were no significant differences detected among these values (

Table 3).

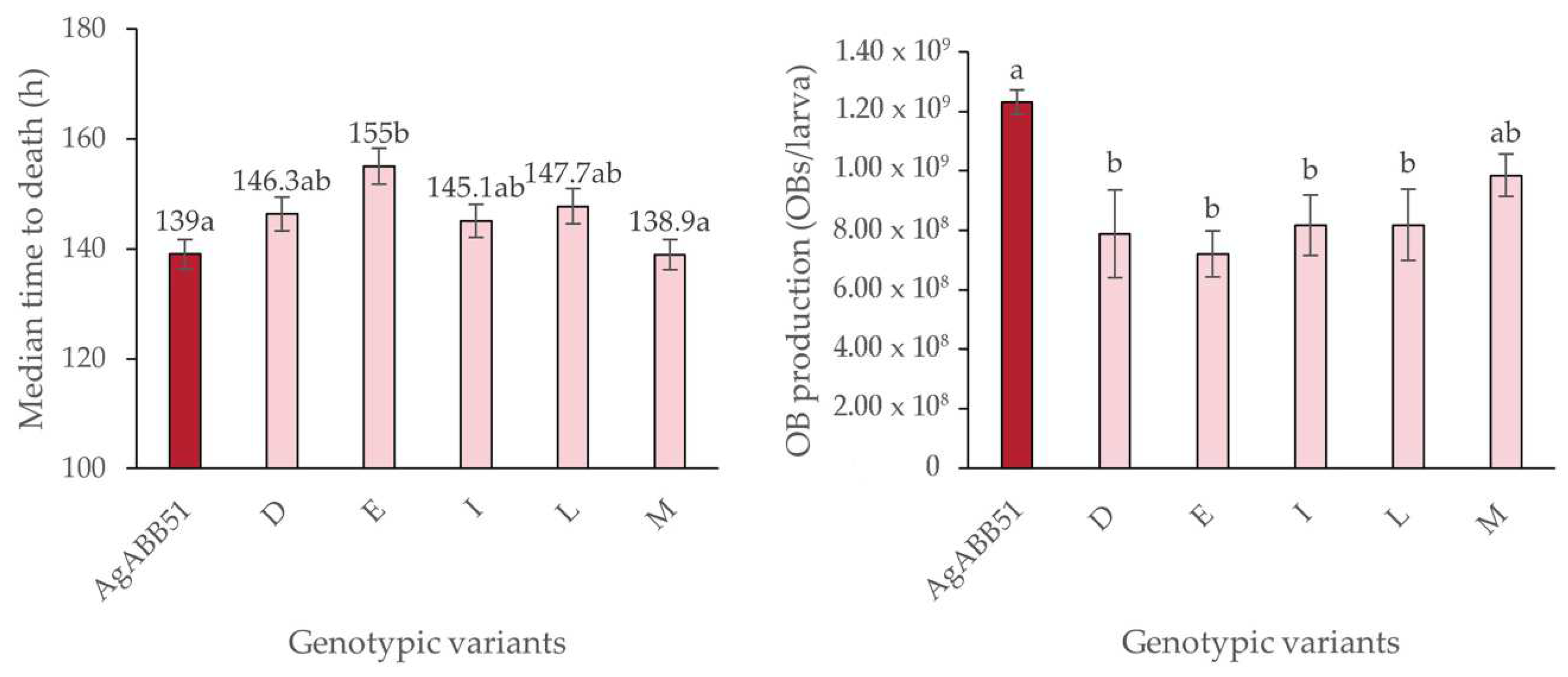

Survival analysis using the log-normal model revealed MTD values that varied between 155.0 h (variant E) and 138.9 h (variant M), compared to 139.0 h for the reference AgABB51 isolate (log-rank χ

2 = 16.3, d.f. = 5, p < 0.05). However, a post hoc Bonferroni analysis revealed that only the MTD values of AgABB51 and variant M differed significantly compared to variant E, whereas the other variants showed intermediate MTD values (

Figure 4a).

In terms of OB production, none of the selected genotypic variants was more productive than the AgABB51 isolate and larvae infected by the variants D, E, I and L produced fewer OBs than those infected by the AgABB51 isolate (F

5,121 = 8.533; p < 0.001) (

Figure 4b).

4. Discussion

Three field-collected AgMNPV isolates were compared in terms of restriction endonuclease profile characteristics and their respective insecticidal properties. AgABB51 was recognized as the most genotypically diverse, as judged by the greater number of RFLPs and submolar fragments within its restriction profile, suggesting the presence of more than one genotypic variant in the wild-type isolate. The

A. gemmatalis mortality response induced by these isolates was tested at three different concentrations. Albeit similar mortality values were observed at the lowest and highest viral concentrations, AgABB51 resulted in the highest mortality response (87%) at an intermediate inoculum concentration (

Table 1). AgABB51 was therefore selected for further biological and genotypic characterization. The OB pathogenicity (LC

50) and speed-of-kill (MTD) values of this isolate were 1.1 x 10

4 OBs/mL and 138.6 hours in second instars, respectively, whereas OB production averaged 1.23 x 10

9 OBs in each virus-killed fifth instar (

Table 2). Although the AgMNPV-2D variant was not included in our bioassays and comparisons of the results of different experimental events tend to be difficult, the AgABB51 LC

50 and MTD values seemed lower than those of AgMNPV-2D, suggesting that AgABB51 might possess traits that would favor its use as a biological insecticide [

21,

27,

44,

45].

A total of 128 clones were obtained by plaque purification of the AgABB51 isolate. From these, 18 different genotypic variants (AgABB51-A to R) were identified based on their HindIII restriction profiles (

Figure 2). A similar heterogeneity has been reported in the population structure of other alphabaculoviruses [

20,

46,

47], including other AgMNPV isolates [

16,

21,

29,

48].

Minor variation in the genome sequence can have a direct impact on the insecticidal phenotype of genotypic variants [

37,

49,

50]. In line with this idea, 13 of the AgABB51 variants caused a mortality similar to or lower than that of AgABB51-wt, whereas five variants (D, E, I, L and M) caused mortality slightly higher (56.8 - 61.8%) than the wild-type isolate.

There was no clear correlation between the frequency of the variant in the isolate (

Figure 3) and virus-induced mortality (

Figure 4), as previously observed by other authors [

20,

21,

50,

51]. One reason may be that variants that are amenable to cell culture conditions are not necessarily the most pathogenic or transmissible variants in nature [

22,

51,

52,

53]. The alternative

in vivo cloning method was originally developed to purify variants from alphabaculovirus isolates [

54,

55], but is a highly labor-intensive method that has largely been abandoned in favor of plaque purification [

20].

The five selected variants from AgABB51 were not significantly more pathogenic than the AgABB51-wt (

Table 3). None of these variants displayed a faster speed-of-kill or higher OB production than AgABB51-wt (

Figure 4). Indeed, for most of these variants slower speed of kill was associated with lower OB production per larva, which deviates from the finding that speed of kill is often correlated with higher OB production, presumably because the virus has more time to replicate and the insect can continue to grow during the infection period [

56,

57,

58]. It appears therefore, that the AgABB51 isolate is genotypically structured so that the speed-of-kill favors rapid insect-to-insect transmission in combination with high OB production which also increases the probability of transmission. These emergent traits likely arise from interactions among the component genotypes, a phenomenon also observed in experiments involving the production of variant mixtures in other alphabaculoviruses [

59].

On a more general note, the study of the highly diverse AgABB51 population also highlights the importance of collective infectious units in virus transmission [

13,

60,

61]. The polyploid nature of viruses that disperse in groups, such as alphabaculoviruses, has important consequences for viral evolution, as it increases the probability of coinfection and recombination and complementation among coinfecting variants. Cells infected with multiple virus genomes will favor interactions between viruses, that may result in changes in viral pathogenesis, the diversity of the virus progeny and the evolution of host resistance [

61].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C.; formal analysis, A.P.; funding acquisition, P.C.; investigation, A.P.; resources, T.W.; methodology, A.P., I.B. and P.C.; writing - original draft preparation, A.P.; writing - review and editing, A.P., D.M., T.W. and P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovacion, grant number AGL2017-83498-C2-1-R. A.P. received a predoctoral grant PRE2018-086829 from the Agencia Estatal de Investigación (Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación) of the Spanish Government.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miguel López-Ferber for providing two of the AgMNPV isolates and Noelia Gorría and Itxaso Ibáñez for insect rearing. J. Sebastián Gómez Díaz (INECOL) provided logistical support to T.W.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bueno, R.C.O.; Bueno, A. de F.; Moscardi, F.; Postali Parra, J.R.; Hoffmann-Campo, C.B. Lepidopteran Larva Consumption of Soybean Foliage: Basis for Developing Multiple-Species Economic Thresholds for Pest Management Decisions. Pest Management Science 2011, 67, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscardi, F.; Carvalho, R.C.Z. de Consumo e utilização de folhas da soja por Anticarsia gemmatalis Hüb. (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) infectada, em diferentes estádios larvais, por seu vírus de poliedrose nuclear. Anais da Sociedade Entomológica do Brasil 1993, 22, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer Crop Science Bayer - Crop Pests Compendium - Anticarsia Gemmatalis by Bayer Crop Science AG Available online:. Available online: https://www.agriculture-xprt.com/products/bayer-anticarsia-gemmatalis-617566 (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Musser, F.R.; Catchot, A.L.; Conley, S.P.; Davis, J.A.; Difonzo, C.; Greene, J.K.; Lorenz, G.M.; Owens, D.; Reisig, D.D.; Roberts, P.; et al. 2019 Soybean Insect Losses in the United States. Midsouth Entomologist 2020, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, F.O.; Abreu, J.Á. de; Christ, L.M.; Rosa, A.P.S.A. da Insecticides Management Used in Soybean for the Control of Anticarsia gemmatalis (Hübner, 1818) (Lepidoptera: Eribidae). Journal of Agricultural Science 2018, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrande, P.E.; Vivan, L.M. Pragas Da Soja. Tecnologia e Produção: Soja e Milho 2011/2012, 2012; 155–206. [Google Scholar]

- Murúa, M.G.; Vera, M.A.; Herrero, M.I.; Fogliata, S.V.; Michel, A. Defoliation of Soybean Expressing Cry1Ac by Lepidopteran Pests. Insects 2018, 9, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, R.C.O.F.; Raetano, C.G.; Junior, J.D.; Carvalho, F.K. Integrated Management of Soybean Pests: The Example of Brazil. Outlooks on Pest Management 2017, 28, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardi, F. Assessment of the Application of Baculoviruses for Control of Lepidoptera. Annual Review of Entomology 1999, 44, 257–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Gómez, D.R. Microbial Control of Soybean Pest Insects and Mites. In Microbial Control of Insect and Mite Pests: From Theory to Practice; Elsevier Inc.: Londrina, Paraná, Brazil, 2017; pp. 199–208. ISBN 978-0-12-803566-5. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardi, F.; de Souza, M.L.; de Castro, M.E.B.; Lara Moscardi, M.; Szewczyk, B. Baculovirus Pesticides: Present State and Future Perspectives. In Microbes and Microbial Technology; Ahmad, I., Ahmad, F., Pichtel, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, 2011; pp. 415–445. ISBN 978-1-4419-7930-8. [Google Scholar]

- Valicente, F.H. Entomopathogenic Viruses. In Natural Enemies of Insect Pests in Neotropical Agroecosystems; Souza, B., Vázquez, L.L., Marucci, R.C., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Switzerland, 2019; pp. 137–150. ISBN 978-3-030-24733-1. [Google Scholar]

- Clavijo, G.; Williams, T.; Muñoz, D.; Caballero, P.; López-Ferber, M. Mixed Genotype Transmission Bodies and Virions Contribute to the Maintenance of Diversity in an Insect Virus. Proc Biol Sci 2010, 277, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandson, M.A. Genetic Variation in Field Populations of Baculoviruses: Mechanisms for Generating Variation and Its Potential Role in Baculovirus Epizootiology. Virol. Sin. 2009, 24, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito, A.F.; Braconi, C.T.; Weidmann, M.; Dilcher, M.; Pereira Alves, J.M.; Gruber, A.; de Andrade Zanotto, P.M. The Pangenome of the Anticarsia gemmatalis multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (AgMNPV). Genome Biology and Evolution 2016, 8, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croizier, G.; Ribeiro, H.C.T. Recombination as a Possible Major Cause of Genetic Heterogeneity in Anticarsia gemmatalis nuclear polyhedrosis virus Wild Populations. Virus Research 1992, 26, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabodevilla, O.; Ibañez, I.; Simón, O.; Murillo, R.; Caballero, P.; Williams, T. Occlusion Body Pathogenicity, Virulence and Productivity Traits Vary with Transmission Strategy in a Nucleopolyhedrovirus. Biological Control 2011, 56, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.L.; Puttler, B.; Popham, H.J.R. Genomic Sequence Analysis of a Fast-Killing Isolate of Spodoptera frugiperda multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus. Journal of General Virology 2008, 89, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, D.L.; Popham, H.J.R.; Harrison, R.L. Genetic Variation and Virulence of Nucleopolyhedroviruses Isolated Worldwide from the Heliothine Pests Helicoverpa armigera, Helicoverpa zea, and Heliothis virescens. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 2011, 107, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguirre, E.; Beperet, I.; Williams, T.; Caballero, P. Genetic Variability of Chrysodeixis includens nucleopolyhedrovirus (ChinNPV) and the Insecticidal Characteristics of Selected Genotypic Variants. Viruses 2019, 11, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Angel, C.; Lasa, R.; Rodríguez-del-Bosque, L.A.; Mercado, G.; Beperet, I.; Caballero, P.; Williams, T. Anticarsia gemmatalis nucleopolyhedrovirus from Soybean Crops in Tamaulipas, Mexico: Diversity and Insecticidal Characteristics of Individual Variants and Their Co-Occluded Mixtures. Florida Entomologist 2018, 101, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory, J.S.; Green, B.M.; Paul, R.K.; Hunter-Fujita, F. Genotypic and Phenotypic Diversity of a Baculovirus Population within an Individual Insect Host. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 2005, 89, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Miller, L.K. Isolation of Genotypic Variants of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Virol 1978, 27, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrizubieta, M.; Simón, O.; Caballero, P.; Williams, T. Nuevos genotipos del nucleopoliedrovirus simple de Helicoverpa armigera (HearSNPV), procedimiento para su producción y uso como agente de control biológico. Patent ES2555165, 29 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, P.; Bernal, A.; Simón, O.; Carnero, A.; Hernández-Suárez, E.; Williams, T.G. Nuevos genotipos del nucleopoliedrovirus simple de Chrysodeixis chalcites (ChchSNPV), procedimiento para su producción y uso como agente de control biológico. Patent ES2504866, 8 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, P.; Murillo, R.; Muñoz, D.; Williams, T. El Nucleopoliedrovirus de Spodoptera exigua (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Como Bioplaguicida: Análisis de Avances Recientes En España. Revista Colombiana de Entomología 2009, 35, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.V.; Wolff, J.L.C.; Garcia-Maruniak, A.; Ribeiro, B.M.; de Castro, M.E.B.; de Souza, M.L.; Moscardi, F.; Maruniak, J.E.; de Andrade Zanotto, P.M. Genome of the Most Widely Used Viral Biopesticide: Anticarsia gemmatalis multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus. Journal of General Virology 2006, 87, 3233–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, G.E.; Knell, J.D. A Nuclear polyhedrosis virus of Anticarsia gemmatalis: I. Ultrastructure, Replication, and Pathogenicity. The Florida Entomologist 1977, 60, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruniak, J.E.; Garcia-Maruniak, A.; Souza, M.L.; Zanotto, P.M.A.; Moscardi, F. Physical Maps and Virulence of Anticarsia gemmatalis nucleopolyhedrovirus Genomic Variants. Archives of Virology 1999, 144, 1991–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Jehle, J.A.; Rucker, A.; Nielsen, A.L. First Evidence of CpGV Resistance of Codling Moth in the USA. Insects 2022, 13, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehle, J.A.; Schulze-Bopp, S.; Undorf-Spahn, K.; Fritsch, E. Evidence for a Second Type of Resistance against Cydia pomonella granulovirus in Field Populations of Codling Moths. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2016, 83, e02330–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, K.; Washburn, J.O.; Volkman, L.E. Midgut-Based Resistance of Heliothis virescens to Baculovirus Infection Mediated by Phytochemicals in Cotton. Journal of Insect Physiology 2000, 46, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, K.E.; Asser-Kaiser, S.; Sayed, S.M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Jehle, J.A. Overcoming the Resistance of Codling Moth against Conventional Cydia pomonella granulovirus (CpGV-M) by a New Isolate CpGV-I12. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 2008, 98, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, M.M.; Eberle, K.E.; Radtke, P.; Jehle, J.A. Baculovirus Resistance in Codling Moth Is Virus Isolate-Dependent and the Consequence of a Mutation in Viral Gene Pe38. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 15711–15716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abot, A.R.; Moscardi, F.; Fuxa, J.R.; Sosa-Gómez, D.R.; Richter, A.R. Development of Resistance By Anticarsia gemmatalis from Brazil and the United States to a Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus under Laboratory Selection Pressure. Biological Control 1996, 7, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.M.; Falleiros, A.M.F.; Moscardi, F.; Gregório, E.A. Susceptibility/Resistance of Anticarsia gemmatalis Larvae to Its nucleopolyhedrovirus (AgMNPV): Structural Study of the Peritrophic Membrane. J Invertebr Pathol 2007, 96, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, G.; Williams, T.; Villamizar, L.; Caballero, P.; Simón, O. Deletion Genotypes Reduce Occlusion Body Potency but Increase Occlusion Body Production in a Colombian Spodoptera frugiperda nucleopolyhedrovirus Population. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e77271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, G.L.; Leppla, N.C.; Dickerson, W.A. Velvetbean Caterpillar: A Rearing Procedure and Artificial Medium123. Journal of Economic Entomology 1976, 69, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.A.; Possee, R.D. The Baculovirus Expression System. A Laboratory Guide; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1992; ISBN 0-412-37150-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, P.R.; Wood, H.A. In Vivo and in Vitro Bioassay Methods for Baculoviruses. In The Biology of Baculoviruses; Granados, R.R., Federici, B.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1986; Volume 2, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Polo Plus, version 1.0. LeOra Software: Parma, MO, USA, 2003.

- Therneau, T.M. A Package for Survival Analysis in R; 2023; https://CRAN.Rproject.org/package=survival.

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022.

- Ferreira, B.C.; Melo, F.L.; Silva, A.M.R.; Sanches, M.M.; Moscardi, F.; Ribeiro, B.M.; Souza, M.L. Biological and Molecular Characterization of Two Anticarsia gemmatalis multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus Clones Exhibiting Contrasting Virulence. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 2019, 164, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, E.B.; Cordeiro, B.A.; Ribeiro, B.M.; de Castro, M.E.B.; Soares, E.F.; Báo, S.N. An Anticarsia gemmatalis multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus Mutant, VApAg, Induces Hemocytes Apoptosis in Vivo and Displays Reduced Infectivity in Larvae of Anticarsia gemmatalis (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Virus Research 2007, 130, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsaro, B.G.; Fraser, M.J. Characterization of Genotypic and Phenotypic Variation in Plaque-Purified Strains of HzSNPV Elkar Isolate. Intervirology 1987, 28, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, D.J.; Vanbergen, A.J.; Watt, A.D.; Hails, R.S.; Cory, J.S. Phenotypic Variation between Naturally Co-Existing Genotypes of a Lepidopteran Baculovirus. Evolutionary Ecology Research 2001, 3, 687–701. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, H.C.T.; Pavan, O.H.O.; Muotri, A.R. Comparative Susceptibility of Two Different Hosts to Genotypic Variants of the Anticarsia gemmatalis nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 1997, 83, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogembo, J.G.; Chaeychomsri, S.; Kamiya, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Katou, Y.; Ikeda, M.; Kobayashi, M. Cloning and Comparative Characterization of Nucleopolyhedroviruses Isolated from African Bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera,(Lepidoptera: Noctudiae) in Different Geographic Regions. Journal of Insect Biotechnology and Sericology 2007, 76, 1_39–1_49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, A.; Simón, O.; Williams, T.; Muñoz, D.; Caballero, P. A Chrysodeixis chalcites single-nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus Population from the Canary Islands Is Genotypically Structured To Maximize Survival. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2013, 79, 7709–7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, O.; Williams, T.; Lopez-Ferber, M.; Caballero, P. Genetic Structure of a Spodoptera frugiperda nucleopolyhedrovirus Population: High Prevalence of Deletion Genotypes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2004, 70, 5579–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijlman, G.P.; van den Born, E.; Martens, D.E.; Vlak, J.M. Autographa californica baculoviruses with Large Genomic Deletions Are Rapidly Generated in Infected Insect Cells. Virology 2001, 283, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, M.; Voncken, J.W.; van Lier, F.L.; Tramper, J.; Vlak, J.M. Detection and Analysis of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus Mutants with Defective Interfering Properties. Virology 1991, 183, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I.R.L.; Crook, N.E. In Vivo Isolation of Baculovirus Genotypes. Virology 1988, 166, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, D.; Castillejo, J.I.; Caballero, P. Naturally Occurring Deletion Mutants Are Parasitic Genotypes in a Wild-Type Nucleopolyhedrovirus Population of Spodoptera exigua. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1998, 64, 4372–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.; Sathiah, N.; Rabindra, R. Optimizing the Time of Harvest of Nucleopolyhedrovirus Infected Spodoptera litura (Fabricius) Larvae under in Vivo Production Systems. Current Science 2005, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Cory, J.S.; Myers, J.H. Adaptation in an Insect Host–Plant Pathogen Interaction. Ecology Letters 2004, 7, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, O.; Williams, T.; López-Ferber, M.; Taulemesse, J.-M.; Caballero, P. Population Genetic Structure Determines Speed of Kill and Occlusion Body Production in Spodoptera frugiperda multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus. Biological Control 2008, 44, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; López-Ferber, M.; Caballero, P. Nucleopolyhedrovirus Coocclusion Technology: A New Concept in the Development of Biological Insecticides. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuán, R. Collective Infectious Units in Viruses. Trends Microbiol 2017, 25, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeks, A.; Sanjuán, R.; West, S.A. The Evolution of Collective Infectious Units in Viruses. Virus Res 2019, 265, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).