1. Introduction

Glyoxal (GO) and methylglyoxal (MGO) are the two most representative molecules among the naturally occurring dicarbonyls. Since such molecules are typically produced by oxidative degradation of lipids and sugars, human exposure can occur either via ingestion (e.g., food) or inhalation (e.g., electronic cigarettes) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Dicarbonyls are also produced by endogenous metabolic pathways (e.g., glycolysis, protein glycation) [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Their concentration is therefore finely regulated by a set of enzymes including glyoxalases, reductases, and dehydrogenases [

9,

10,

11,

12].

An accumulation of dicarbonyls can be due to an overload of exogenous intake of such compounds or to the depletion or dysregulation of endogenous substrates and enzymes [

2,

13,

14]. Dicarbonyls are electrophiles able to covalently bind biomolecules like DNA and proteins to generate the so-called advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) [

15,

16,

17]. An uncontrolled accumulation of AGEs (i.e., carbonylation) is correlated with the onset and progression of several human diseases [

18,

19]. The most likely explanation of the pathogenic role of AGEs is the alteration of the natural functions of biological molecules modified by dicarbonyls, along with an increased oxidative stress and immune response.

For this reason, the development of dicarbonyl binders has been advocated as a potential strategy to develop new food preservatives or new drugs for the mitigation of the accumulation of AGEs in humans, and few molecules have been already reported as binders of dicarbonyls [

20,

21,

22,

23].

However, it is hard to setup a robust, universal method for the screening of candidate binders. For carbonyl toxicants involved in human disease development (i.e., α,β-unsaturated aldehydes) a convenient chromatographic assay was successfully applied to the identification of hit compounds (e.g., carnosine) and for further studies aimed at structure optimization [

24]. The assay was built around a natural occurring molecule (i.e., HNE) identified as an analytically convenient probe that averages the reactivity of the whole class of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. HNE is analytically convenient since is stable and can be easily quantified by means of liquid chromatography, with UV detection. Upon incubation with HNE binders can be then identified as compounds able to determine a decrease over time of the residual concentration as measured by liquid chromatography.

Unfortunately, naturally occurring dicarbonyls like GO or MGO are not convenient molecular probes since they are transparent to most of the common detectors (e.g., UV or MS). Furthermore, they are hardly separated by the most common chromatography variants owing to their hydrophilicity. For these reasons, they are typically analyzed upon derivatization [

1,

3,

4,

25,

26,

27] or upon inducing other chemical reactions able to convert them in detectable molecules [

28].

Nevertheless, analytical strategies relying on derivatization before quantification are not exempt from risks. In fact, the candidate binders incubated with the molecular probe can affect the derivatization yield. Alternatively, the chemicals used for derivatization can break the adducts between the molecular probe and its binder. These are just two examples of potential side reactions leading to an underestimation or overestimation of the residual amount of molecular probe, with the risk of identifying false positives or false negatives during the screening.

To overcome such limitations, an alternative analytical strategy is herein reported. A UV responsive surrogate of naturally occurring dicarbonyls was synthesized and used as a molecular probe to assess the binding activity, without derivatization. This strategy allowed to setup a simple and cost-effective chromatographic assay that was validated by testing molecules with already stablished already binding activity towards MGO and GO.

2. Results and discussion

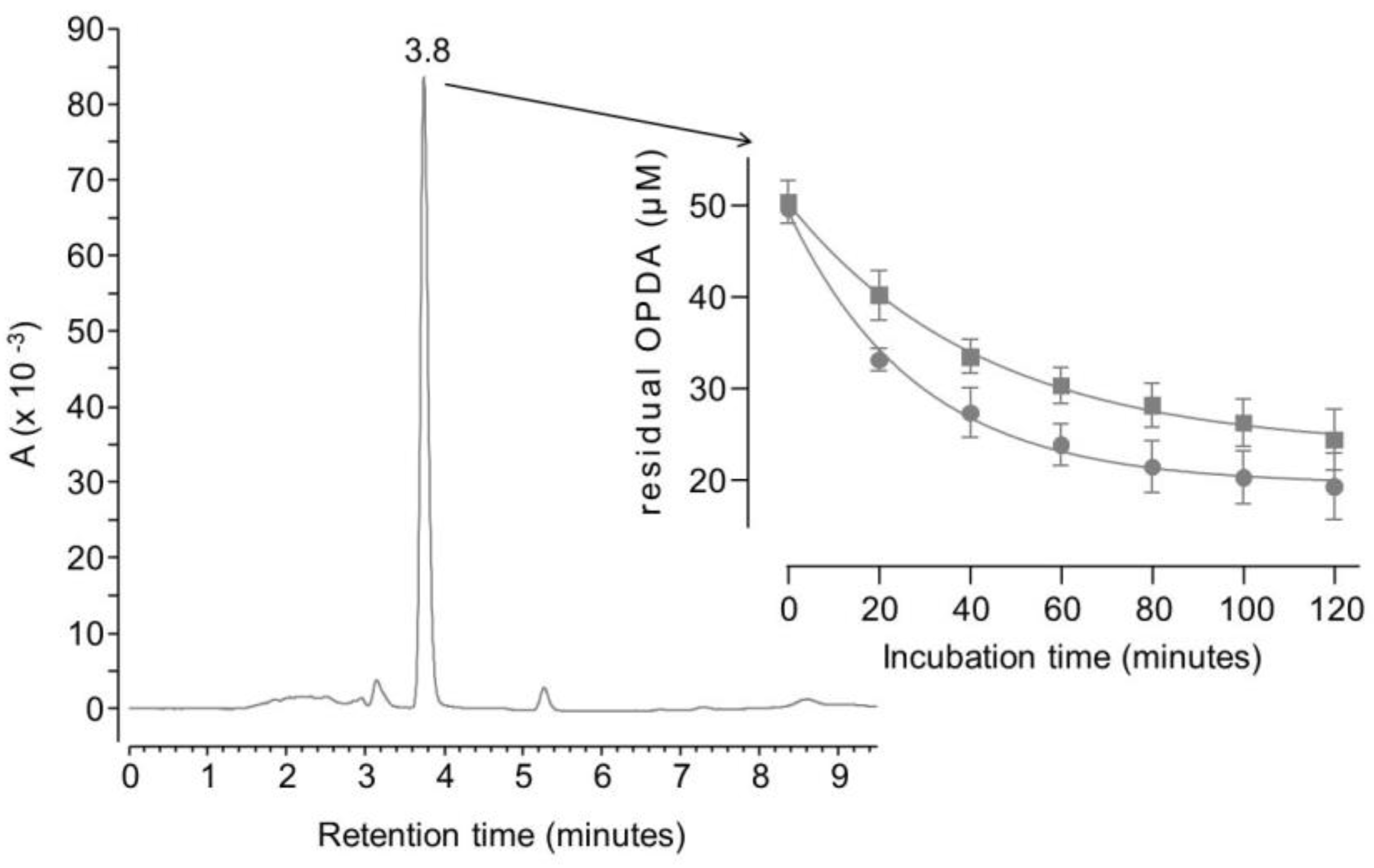

As reported in

Figure 1, OPDA is detectable at 3.8 minutes and its residual concentration decreases over time upon the incubation with either MGO or BGO.

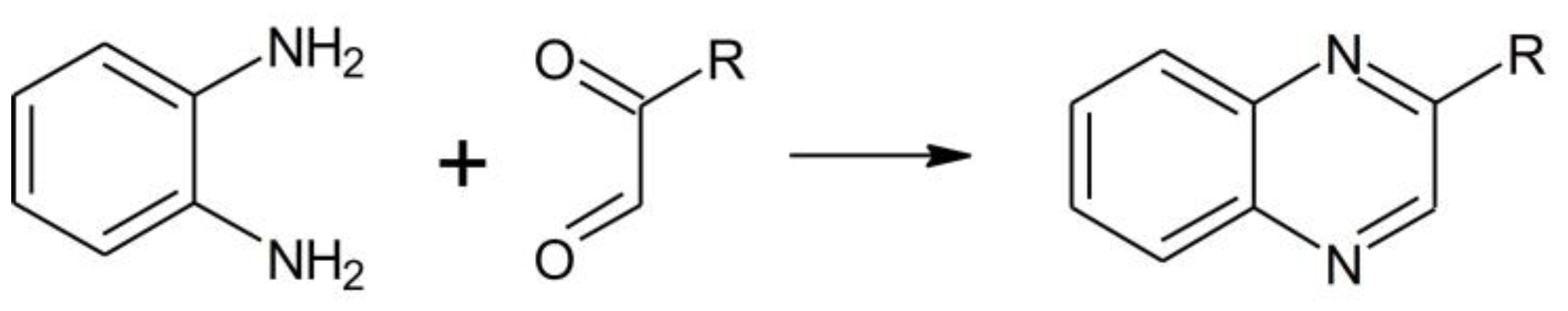

Both reactions were complete within two hours since residual OPDA reached a stable concentration of 20 µM. According to the reaction scheme reported in

Figure 2, one mole of OPDA is expected to react with an equimolar amount of MGO or BGO to produce 2-methylquinoxaline or 2-benzylquinoxaline, respectively [

25,

27].

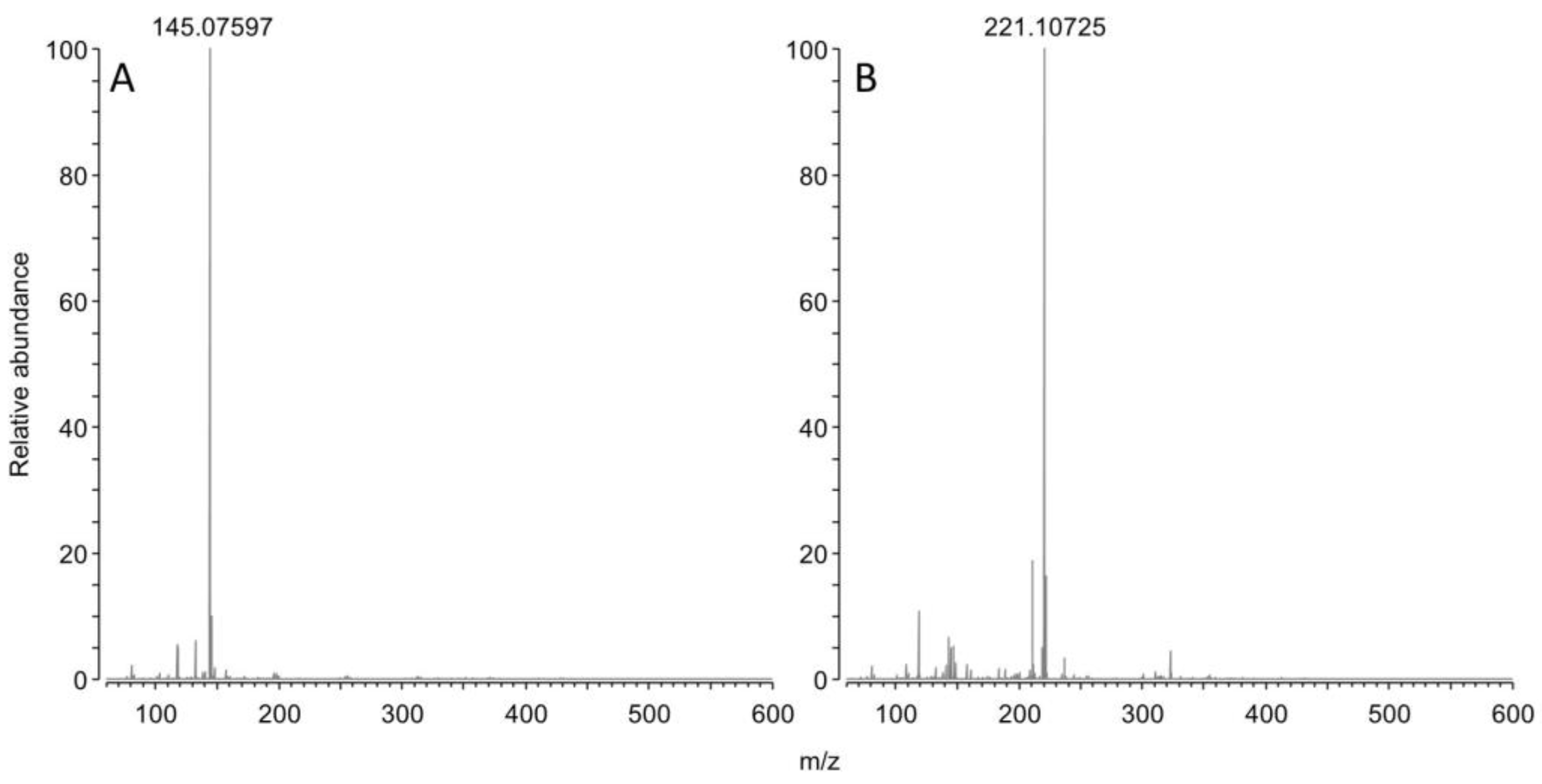

This reaction scheme is consistent with the residual concentration of OPDA at the kinetics endpoints, since a molar excess of OPDA was used (i.e., 50 µM OPDA; 30 µM of either GO or MGO). The reaction scheme is also consistent with ESI-MS experiments. Specifically, OPDA incubated with MGO produced a signal at 145.07597 m/z (

Figure 3A), which is -0.4 ppm shy from the expected m/z value for monoprotonated 2 methyl quinoxaline. Similarly, incubation with BGO produced a signal at 221.10725 m/z (

Figure 3B), which is -0.3 ppm shy from the expected m/z value for monoprotonated 2 benzyl quinoxaline.

No trace of adducts with residual acetals of MGO or BGO, nor with any other impurities were found during MS analyses. Therefore, BGO acetal was obtained as a pure compound and hydrolysis was complete for both MGO and BGO acetals.

Kinetics data of

Figure 1 fit with a one-phase exponential decay, although extra sum-of-squares F test rejects the null hypothesis that the preferred model to fit all data is one curve. Separate fitting was then performed for data collected using BGO or MGO, and the half-life of OPDA was found to be 20 minutes when it reacts with MGO, whereas a half-life of 30 minutes was found in parallel experiments with BGO. This confirms that MGO is about 1.5 as reactive as BGO towards OPDA.

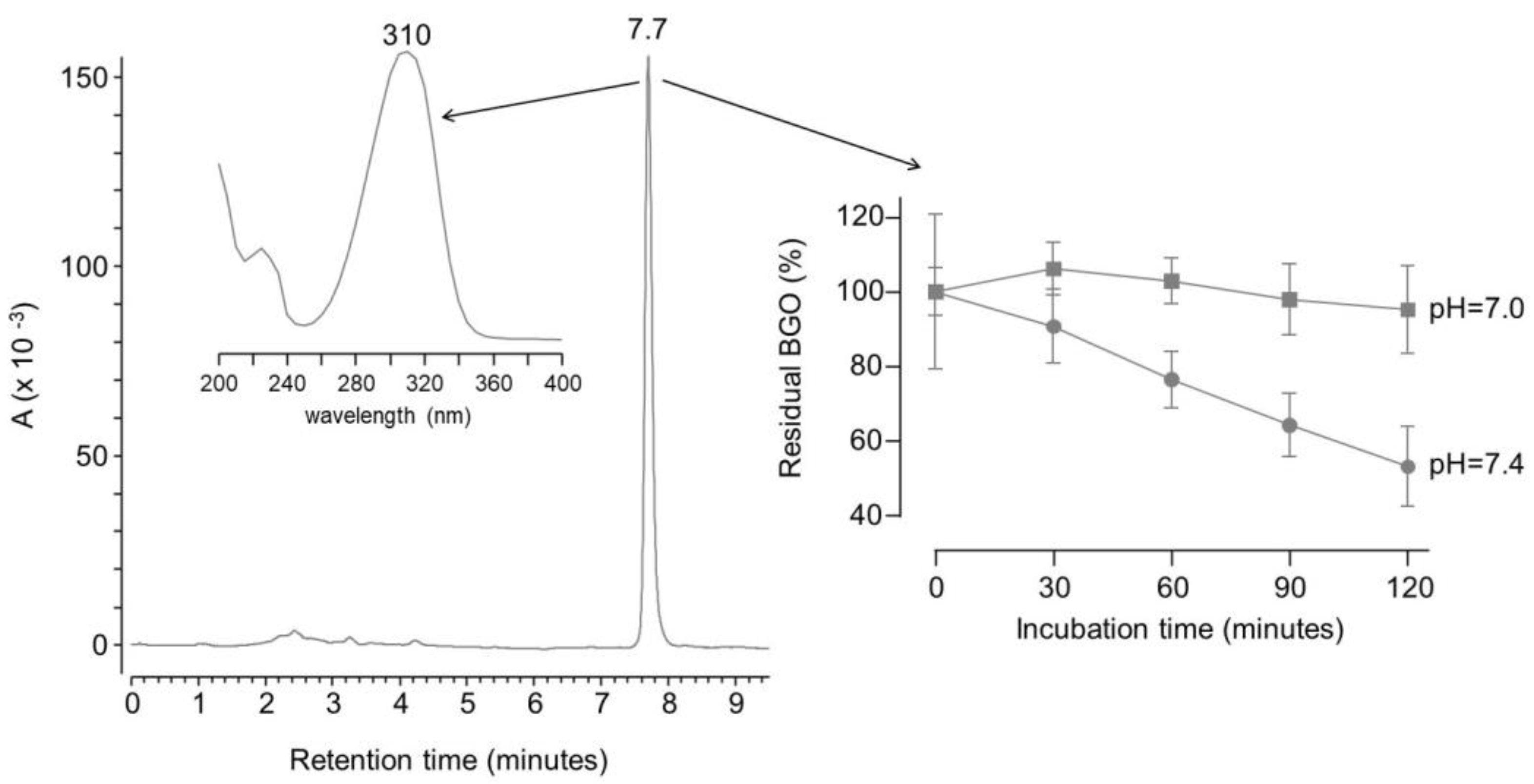

However, BGO gives a single peak chromatogram at around 7.7 minutes when analyzed by reversed phase chromatography. The peak was detectable since BGO has a characteristic UV maximum absorbance at 310 nm (see

Figure 4).

On the contrary, no peak can be obtained in the same conditions for MGO or any other naturally occurring dicarbonyl, because such molecules have no strong chromophore, nor can be easily separated by reversed phase chromatography owing to their high hydrophilicity. Since BGO compares with MGO in term of reactivity with OPDA, it can be used as surrogate of naturally occurring dicarbonyls (e.g., glyoxal, methylglyoxal) to setup an assay for the screening of dicarbonyl binders.

This assay resembles a LC-UV method that uses HNE as molecular probe to identify hit compounds able to react with α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. Such a method was successfully applied to study the properties of molecules like carnosine, pyridoxamine, aminoguanidine and hydralazine. [

23].

Therefore, the same molecules were tested under the same conditions reported in literature using BGO as molecular probe to assess their selectivity. Unlike for the HNE assay, the reaction had to be performed at pH 7 instead of 7.4, since even slightly basic conditions induced a spontaneous degradation of BGO (see

Figure 4). In fact, two-way ANOVA test on the residual concentration of BGO rejected the null hypothesis that the amount of BGO remains the same upon incubation in phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 for 60 minutes or more. On the contrary, the hypothesis was not rejected for experiments at pH 7 within 2 hours. This is not surprising since dicarbonyls can undergo benzilic acid rearrangement at basic pH [

23,

29].

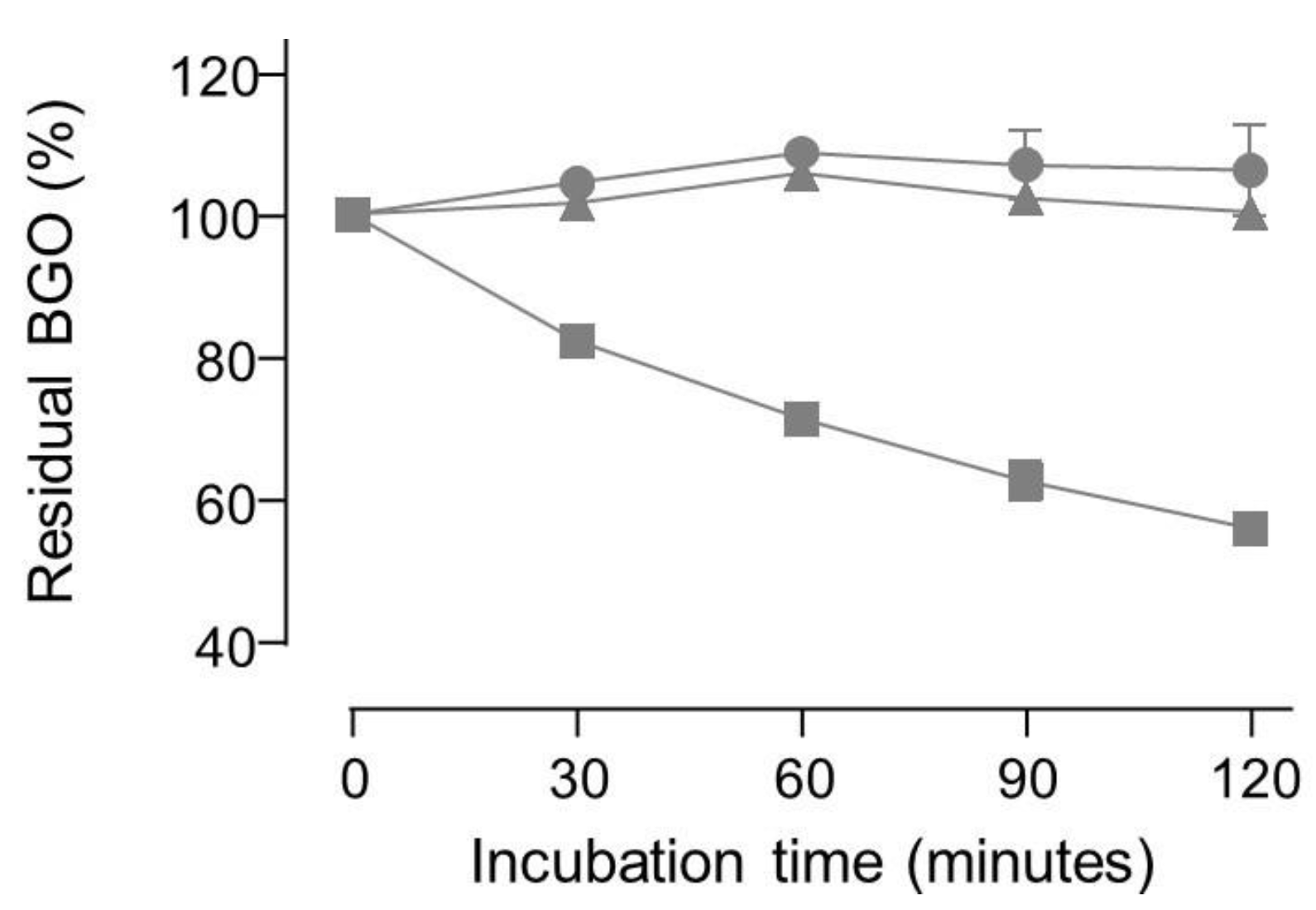

No apparent degradation of BGO was observed in neutral buffered solutions even when carnosine or pyridoxamine were added, whereas aminoguanidine induced a decrease in BGO concentration over time (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

plot of the residual concentration of 50 µM BGO upon incubation in phosphate buffer at pH=7 with 1 mM carnosine (circles) or 1 mM pyridoxamine (triangles) or 1 mM aminoguanidine (squares).

Figure 5.

plot of the residual concentration of 50 µM BGO upon incubation in phosphate buffer at pH=7 with 1 mM carnosine (circles) or 1 mM pyridoxamine (triangles) or 1 mM aminoguanidine (squares).

Incubation with hydralazine produced a very fast decrease in BGO peak area since less than 0.1% of the initial amount was detectable at 30 minutes and right after spiking hydralazine into BGO solution the peak area was already below 20% of a reference sample (i.e., 50 µM BGO). ESI-MS experiments confirmed that no adducts between BGO and carnosine or pyridoxamine were detectable. As for OPDA experiments, BGO produced adducts detectable by ESI-MS with both aminoguanidine and hydralazine (data not shown). ESI-MS experiments indicated also that MGO and BGO reacts by the same mechanism already reported in literature [

23].

The reactivity of the tested compounds is partly consistent with the literature. Specifically, both aminoguanidine and hydralazine have been already reported as dicarbonyl binders [

23,

30]. However, literature data suggest similar reaction kinetics with MGO, whereas the experiments with BGO suggest that hydralazine reacts way faster than aminoguanidine with dicarbonyls. Although also a mild reactivity of MGO with carnosine have been reported [

23], no reactivity with BGO was found by the LC-UV herein reported, nor ESI-MS signals of carnosine adducts with BGO or MGO. Such discrepancies can be attributed to the experimental designs. In fact, literature data showing a reactivity of carnosine with MGO have been collected after 24 h incubation at pH 7.4 with reagents in the millimolar concentration range [

23]. Such conditions can be conducive to benzilic acid rearrangement [

29]. The impact of such side reaction was not investigated for the assay used in literature, since the method was not designed to detect MGO or its degradation product deriving from benzilic acid rearrangement. Therefore, the results obtained by the new LC-UV assay using BGO at pH 7 look more reliable since side reactions were minimized.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

HPLC grade water (18 MΩ x cm) was purified with a Milli-Q water system (Millipore; Milan; Italy). HPLC grade solvents and all the other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Merck Life Science, Milan, Italy). Benzylglyoxal dimethylacetal was synthesized as reported in subsection 3.2.

3.2. Synthesis of benzylglyoxal dimethylacetal

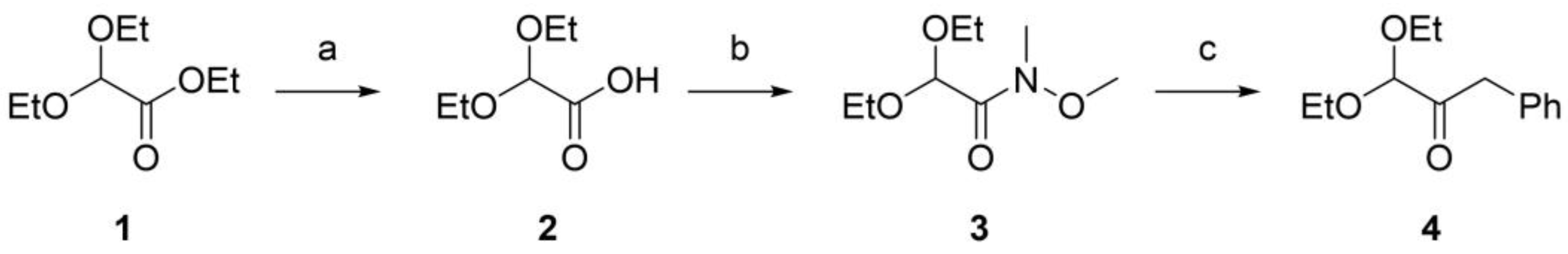

The general scheme of the procedures for the synthesis of benzylglyoxal dimethylacetal is reported in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Synthesis of benzylglyoxal dimethylacetal: (a) 1N NaOH, EtOH, RT; (b) N-methylmorpholine, EDC·HCl, HOBT, N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine·HCl, DCM, RT; (c) BnMgBr, THF, 0 °C.

Figure 5.

Synthesis of benzylglyoxal dimethylacetal: (a) 1N NaOH, EtOH, RT; (b) N-methylmorpholine, EDC·HCl, HOBT, N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine·HCl, DCM, RT; (c) BnMgBr, THF, 0 °C.

3.2.1. Synthesis of 2,2-diethoxyacetic acid (compound 2, Figure 1)

1 N NaOH (2.8 mL) was added to a solution of ethyl 2,2-diethoxyacetate (compound 1,

Figure 1, 0.5 mL, 2.80 mmol) in ethanol (1.5 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 1h at room temperature. The organic solvent was evaporated under vacuum and the aqueous phase was extracted with diethyl ether (2 mL). The aqueous layer was then acidified and extracted with ethyl acetate (4 × 5 mL) and the combined organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na

2SO

4. The solvent was removed

in vacuo to give 2,2-diethoxyacetic acid as a clear oil (403 mg, 2.72 mmol). Yield: 97.3%. TLC (DCM/MeOH 7:3 + 1% formic acid) Rf: 0.63 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 4.96 (s, 1H), 3.78 – 3.63 (m, 4H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 7H).

3.2.2. Synthesis of 2,2-Diethoxy-N-methoxy-N-methyl-acetamide (compound 3, Figure 1)

To a stirred solution of 2,2-diethoxyacetic acid (403 mg, 2.72 mmol) in DCM (10 ml) at 0 °C, N-methylmorpholine (0.45 mL, 4.08 mmol), EDC hydrochloride (548 mg, 2.86 mmol), and HOBT (438 mg, 2.86 mmol) were added. Then N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine hydrochloride (292 mg, 2.99 mmol) was added to the solution. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. Afterward, the solvent was evaporated in vacuo, the crude was dissolved in diethyl ether (10 mL), washed with a 10% aqueous solution of HCl (3 mL), and with a 10% aqueous solution of NaHCO3 (2 x 3 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and the solvent was removed in vacuo to give 2,2-Diethoxy-N-methoxy-N-methyl-acetamide as a clear oil (300 mg, 1.57 mmol). Yield: 57.7%. TLC (cyclohexane: ethyl acetate 8:2) Rf: 0.27 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.33 (bs, 1H), 3.80 – 3.58 (m, 5H), 3.47 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.21 (bs, 3H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.22 – 1.17 (m, 3H).

3.2.3. Synthesis of Benzylglyoxal dimethylacetal (compound 4, Figure 1)

Benzylmagnesiumbromide was freshly prepared from benzylbromide (0.56 mL, 4.71 mmol) and magnesium (1.72 gr, 70.65 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (7.5mL) Then, it was added under vigorous stirring to a solution of 2,2-Diethoxy-N-methoxy-N-methyl-acetamide (300 mg, 1.57 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (5 mL). The reaction was stirred for 2 h at 0 °C. The reaction was quenched with 20 mL of a 10% aqueous solution of HCl, and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 20 mL). Afterward, the combined organic phases were sequentially washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure, affording a crude that was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (cyclohexane/dichloromethane 6:4). The pure product Benzylglyoxal dimethylacetal was isolated as a colorless oil (187 mg, 0.84 mmol). Yield: 53.6%. TLC (cyclohexane: ethyl acetate 8:2) Rf: 0.81 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39 – 7.17 (m, 5H), 4.64 (s, 1H), 3.90 (s, 2H), 3.81 – 3.64 (m, 2H), 3.63 – 3.45 (m, 2H), 1.25 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 203.13, 133.76, 129.74, 128.44, 126.81, 102.34, 63.38, 43.65, 26.91, 15.14.

3.3. Stock solutions

Titrated stock solutions of methylglyoxal (MGO) and benzylglyoxal (BGO) were obtained by acidic hydrolysis of the corresponding dimethylacetals. To provide the best hydrolysis yield the reaction was performed at 60 °C for 5 hours in 1 M hydrochloric acid containing 50% of acetonitrile to ensure solubilization of BGO. The hydrolysis yield and stock solution concentration were determined indirectly by using a chromatographic assay to determine the residual amount of ortho-phenylenediammine (OPDA, see subsubsection 3.4.1). Briefly, an aliquot was picked up from the reaction batch and diluted a hundred folds in 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7 containing 50 % acetonitrile and a molar excess of OPDA. The reaction with OPDA provides derivatization of dicarbonyls to produce 2-substituted quinoxaline derivatives, as from the reaction scheme reported in

Figure 2 [

25,

27]. The moles of MGO or BGO can be then calculated as the difference between the moles of OPDA added and the residual moles at the end of the incubation.

3.4. Methods

3.4.1. Ortho-phenylenediammine binding kinetics

The analyses were provided by a Surveyor HPLC system equipped with a Gemini C18 column (250 ×2.1 mm, 5 μM particle size, 110 Å pore size, Phenomenex, Milan, Italy). An Optisolv mini filter 0.5 mm (Sigma) was installed before the column to protect it from particulates. A solution of OPDA (50 µM in 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7 containing 50 % acetonitrile) was spiked with MGO or BGO down to 30 µM final concentration and incubated into the autosampler at 37 °C. Aliquots of 3 µL were picked up at different times and injected into the column. The elution of the analytes was performed at 30 °C by a 200 µL/min flowrate with the mobile phase reported in

Table 1.

UV detection within a wavelength range from 200 to 400 nm was provided by a photodiode array detector. Instrument control and data analysis were provided by the software Xcalibur 2.07 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rodano, MI, Italy).

3.4.2. Direct determination of dicarbonyl binding activity

Dicarbonyl binding activity was determined by measuring over time the residual amount of BGO by means of LC-UV. For each tested compound a stock solution was prepared in water or the most appropriate solvent to ensure solubilization. The compounds were then separately spiked into 100 mM phosphate buffer containing 10 % acetonitrile and 50 µM BGO down to 1 mM final concentration and incubated into the autosampler at 37 °C. The analytical platform and analysis method are the same reported in subsubsection 3.4.1.

3.4.3. Mass spectrometry

The samples were diluted tenfold in 30% aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid and infused at 5 µL/min flowrate directly into a Finnigan Ion Max 2 electrospray (ESI) by using a glass microliter syringe. Sample nebulization and ionization were provided by using a metal capillary 140 mm long and with a 160 µm inner diameter, and applying a spray voltage of 5 kV, 20 units of sheath gas (nitrogen), and a capillary temperature of 275 °C. MS spectra were collected by an LTQ-Orbitrap™ XL-ETD mass spectrometer within a scan range from 60 to 600 m/z. The analyzer was working on 5x10

5 ion per scan, with a resolution of 100000 (full width at half-maximum at 400 m/z). Lock mass option was enabled to provide real time internal mass calibration. Reference masses were 20 ions identified as background ESI trace contaminants and already listed as common mass spectrometry contaminants [

31]. Instrument control was provided by the software LTQ Tune plus 2.5.5 and data extraction and analysis by Xcalibur 2.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rodano, MI, Italy).

3.4.4. NMR spectroscopy

1H-NMR spectra were recorded using an FT-spectrometer operating at 300 MHz while 13C-NMR at 75.43 MHz. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm relative to the residual solvent (CHCl3) as an internal standard. Signal multiplicity is designed according to the following abbreviations: s = singlet, d = doublet, dd = doublet of doublets, t = triplet, m = multiplet, and br s = broad singlet. Purifications were performed by flash chromatography using silica gel (particle size 40–63 μm, Merck) on IsoleraTM (Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden) apparatus.

4. Conclusions

BGO can be considered as a convenient surrogate of naturally occurring dicarbonyls, of which retains the same reaction mechanism and compares with them in terms of kinetics, although it can be directly analyzed by reversed phase chromatography with an UV detector, without derivatization. Such features make it a good molecular probe for the setup of a simple and cost-effective chromatographic assays for the identification of hit compounds able to bind dicarbonyls. Such a method parallels other known LC-UV assays that were built for the identification of hit compounds able to bind other classes of naturally occurring carbonyl compounds (i.e., α,β-unsaturated aldehydes). The herein described assay can have a significant impact in pharmaceutical research especially for the characterization of the selectivity profile of candidate drugs and preservatives aimed at detoxifying specific aldehyde classes that are involved in cell damage and human disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, LR; methodology, AA, LF and LR; validation, LR; formal analysis, LR; investigation, AA, ES and LF; writing—original draft preparation, AA and LR; writing—review and editing, LF and LR; supervision, LR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arribas-Lorenzo, G.; Morales, F.J. Analysis, Distribution, and Dietary Exposure of Glyoxal and Methylglyoxal in Cookies and Their Relationship with Other Heat-Induced Contaminants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 2966–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.; Choi, Y.S.; Na, H.G.; Bae, C.H.; Song, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.-D. Glyoxal and Methylglyoxal as E-cigarette Vapor Ingredients-Induced Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine and Mucins Expression in Human Nasal Epithelial Cells. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2020, 35, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ho, C.-T. Flavour chemistry of methylglyoxal and glyoxal. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4140–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Ishida, J.; Xuan, Z.X.; Nakamura, A.; Yoshitake, T. Determination of Glyoxal, Methylglyoxal, Diacethyl, and 2, 3-Pentanedione in Fermented Foods by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Fluorescence Detection. J. Liq. Chromatogr. 1994, 17, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, J.N.; Wood, K.D.; Knight, J.; Assimos, D.G.; Holmes, R.P. Glyoxal Formation and Its Role in Endogenous Oxalate Synthesis. Adv. Urol. 2012, 2012, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornalley, P.J.; Langborg, A.; Minhas, H.S. Formation of glyoxal, methylglyoxal and 3-deoxyglucosone in the glycation of proteins by glucose. Biochem. J. 1999, 344 Pt 1, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Karmakar, K.; Chakravortty, D. Cells producing their own nemesis: Understanding methylglyoxal metabolism. IUBMB Life 2014, 66, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.A.; Thornalley, P.J. The formation of methylglyoxal from triose phosphates. Investigation using a specific assay for methylglyoxal. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1993, 212, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, N.; Xue, M.; Thornalley, P.J. Dicarbonyls and glyoxalase in disease mechanisms and clinical therapeutics. Glycoconj. J. 2016, 33, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre, G.; Kikonyogo, A.; Pietruszko, R. Methylglyoxal as substrate and inhibitor of human aldehyde dehydrogenase: Comparison of kinetic properties among the three isozymes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1998, 119, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagt, D.L.V.; A Hunsaker, L. Methylglyoxal metabolism and diabetic complications: roles of aldose reductase, glyoxalase-I, betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase and 2-oxoaldehyde dehydrogenase. Chem. Interactions 2003, 143-144, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Jagt, D.L.; Robinson, B.; Taylor, K.K.; Hunsaker, L.A. Reduction of trioses by NADPH-dependent aldo-keto reductases. Aldose reductase, methylglyoxal, and diabetic complications. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 4364–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichard, G.A., Jr.; Skutches, C.L.; Hoeldtke, R.D.; Owen, O.E. Acetone metabolism in humans during diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes 1986, 35, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abordo, E.A.; Minhas, H.S.; Thornalley, P.J. Accumulation of α-oxoaldehydes during oxidative stress: a role in cytotoxicity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 58, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, T.W.; Westwood, M.E.; McLellan, A.C.; Selwood, T.; Thornalley, P.J. , Binding and modification of proteins by methylglyoxal under physiological conditions. A kinetic and mechanistic study with N alpha-acetylarginine, N alpha-acetylcysteine, and N alpha-acetyllysine, and bovine serum albumin. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 32299–32305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Thornalley, P.J.; Dawczynski, J.; Franke, S.; Strobel, J.; Stein, G.; Haik, G.M. Methylglyoxal-Derived Hydroimidazolone Advanced Glycation End-Products of Human Lens Proteins. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 5287–5292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Cohenford, M.A.; Dutta, U.; Dain, J.A. The structural modification of DNA nucleosides by nonenzymatic glycation: an in vitro study based on the reactions of glyoxal and methylglyoxal with 2′-deoxyguanosine. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 390, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.W.T.; Gonzalez, E.D.J.L.; Zoukari, T.; Ki, P.; Shuck, S.C. Methylglyoxal and Its Adducts: Induction, Repair, and Association with Disease. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1720–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalkwijk, C.; Stehouwer, C.D.A. Methylglyoxal, a Highly Reactive Dicarbonyl Compound, in Diabetes, Its Vascular Complications, and Other Age-Related Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 100, 407–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondrak, G.T.; Cervantes-Laurean, D.; Roberts, M.J.; Qasem, J.G.; Kim, M.; Jacobson, E.L.; Jacobson, M.K. Identification of α-dicarbonyl scavengers for cellular protection against carbonyl stress. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002, 63, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Wang, Y.; Lo, C.-Y.; Ho, C.-T. Methylglyoxal: its presence and potential scavengers. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löbner, J.; Degen, J.; Henle, T. Creatine Is a Scavenger for Methylglyoxal under Physiological Conditions via Formation of N-(4-Methyl-5-oxo-1-imidazolin-2-yl)sarcosine (MG-HCr). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 2249–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colzani, M.; De Maddis, D.; Casali, G.; Carini, M.; Vistoli, G.; Aldini, G. Reactivity, Selectivity, and Reaction Mechanisms of Aminoguanidine, Hydralazine, Pyridoxamine, and Carnosine as Sequestering Agents of Reactive Carbonyl Species: A Comparative Study. Chemmedchem 2016, 11, 1778–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vistoli, G.; Orioli, M.; Pedretti, A.; Regazzoni, L.; Canevotti, R.; Negrisoli, G.; Carini, M.; Aldini, G. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Carnosine Derivatives as Selective and Efficient Sequestering Agents of Cytotoxic Reactive Carbonyl Species. Chemmedchem 2009, 4, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzsche, S.; Billig, S.; Rynek, R.; Abburi, R.; Tarakhovskaya, E.; Leuner, O.; Frolov, A.; Birkemeyer, C. Derivatization of Methylglyoxal for LC-ESI-MS Analysis—Stability and Relative Sensitivity of Different Derivatives. Molecules 2018, 23, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhu, Y.; He, S.; Fan, J.; Hu, Q.; Cao, Y. Development and Validation of a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Method for the Determination of Diacetyl in Beer Using 4-Nitro-o-phenylenediamine as the Derivatization Reagent. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3013–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, A.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Almeida, P.J.; Oliva-Teles, M.T. Determination of glyoxal, methylglyoxal, and diacetyl in selected beer and wine, by hplc with uv spectrophotometric detection, after derivatization with o-phenylenediamine. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 1999, 22, 2061–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, N.; González-Sánchez, J.M.; Demelas, C.; Clément, J.-L.; Monod, A. A fast and efficient method for the analysis of α-dicarbonyl compounds in aqueous solutions: Development and application. Chemosphere 2023, 319, 137977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, T.W.; Dehn, W.M. The Benzilic Acid Rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1930, 52, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornalley, P.J. Glutathione-dependent detoxification of α-oxoaldehydes by the glyoxalase system: involvement in disease mechanisms and antiproliferative activity of glyoxalase I inhibitors. Chem. Interactions 1998, 111-112, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, B.O.; Sui, J.; Young, A.B.; Whittal, R.M. Interferences and contaminants encountered in modern mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 627, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).