Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

26 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

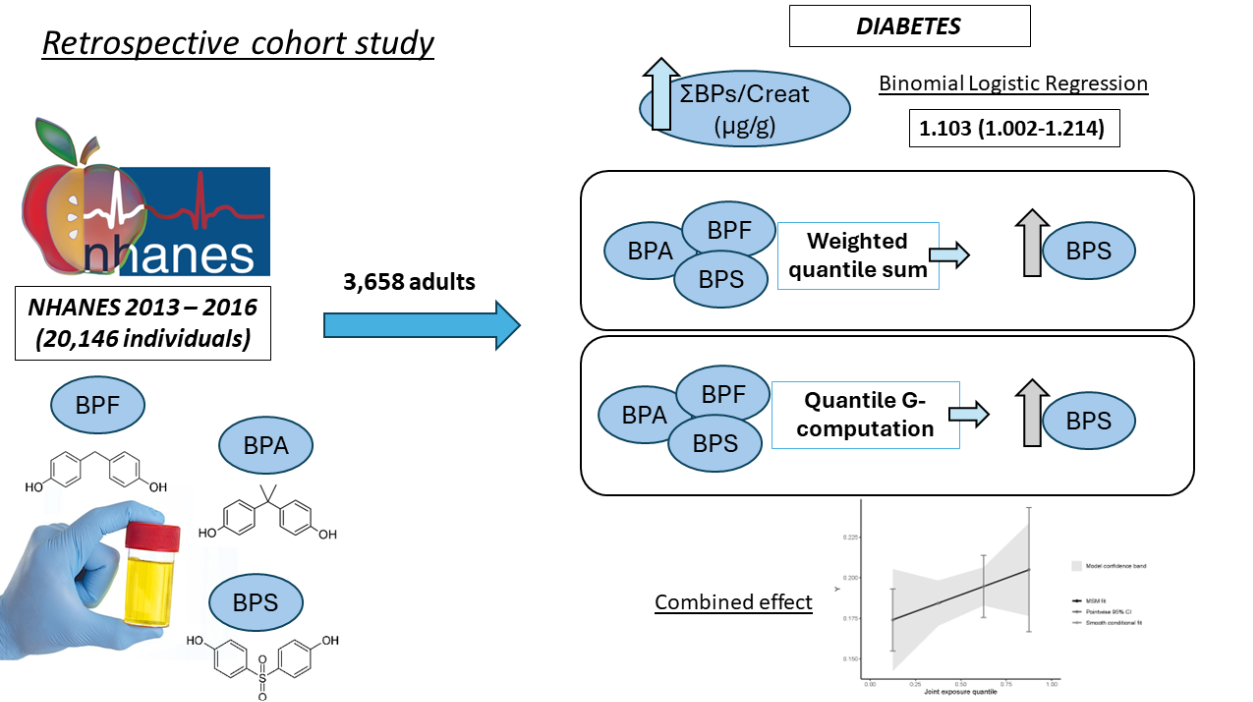

2. Materials and Methods

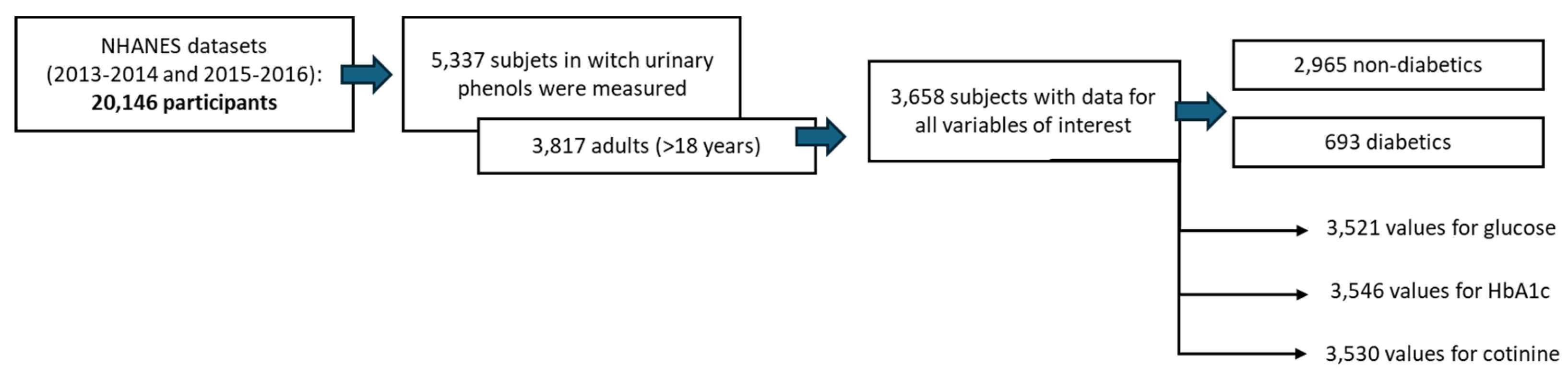

2.1. Data ExtRaction fRom the NHANES CohoRt

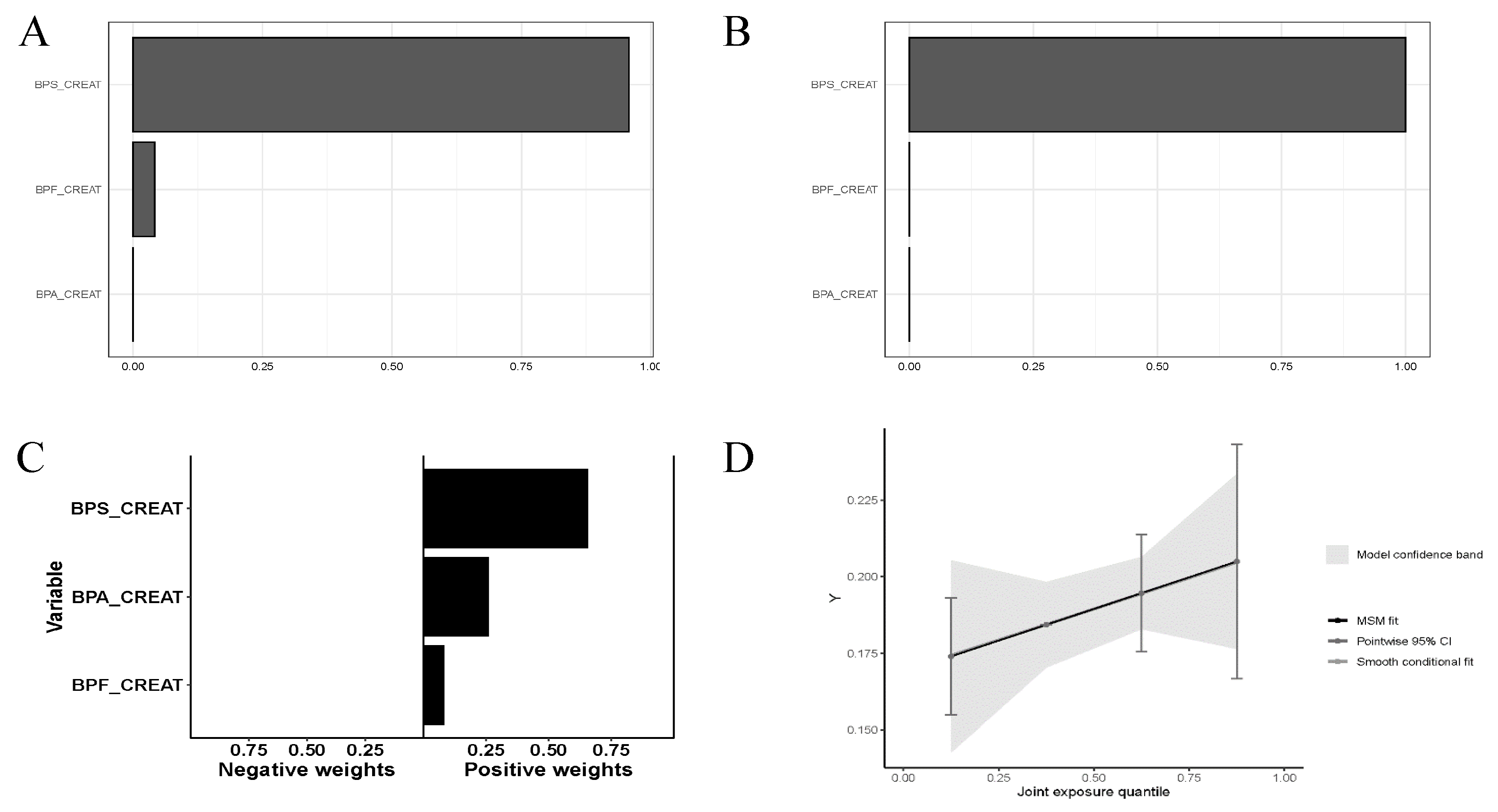

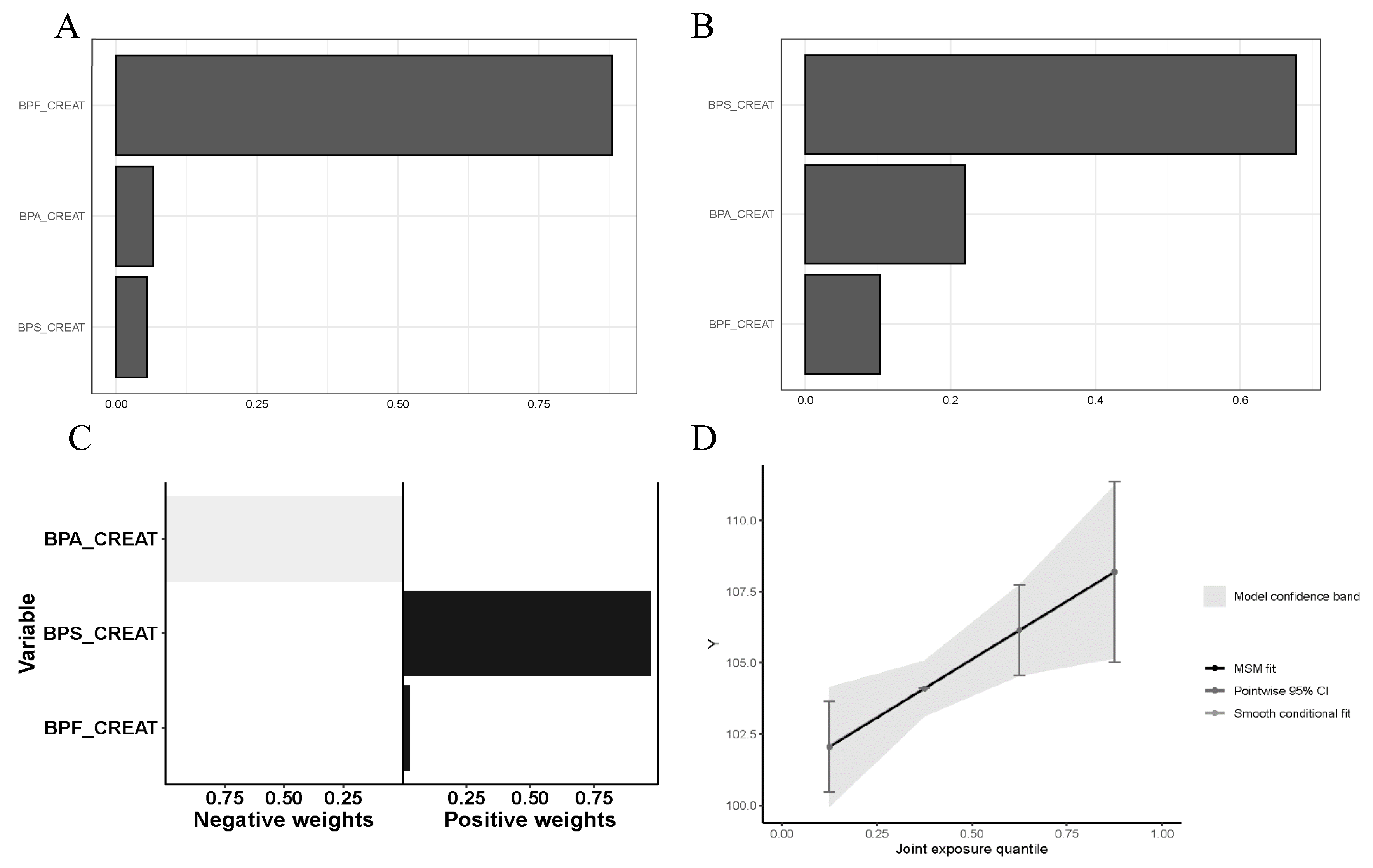

2.2. Combined URinaRy Bisphenol ExposuRe Study

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Porta, R. Anthropocene, the plastic age and future perspectives. FEBS Open Bio 2021, 11, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenberg, L.N.; Hauser, R.; Marcus, M.; et al. Human exposure to bisphenol A (BPA). Reproductive Toxicology 2007, 24, 139–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, S.A. The politics of plastics: the making and unmaking of bisphenol a ‘safety’. Am J Public Health 2009, 99 (Suppl. 3), 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, L.N.; Chahoud, I.; Heindel, J.J.; et al. Urinary, circulating, and tissue biomonitoring studies indicate widespread exposure to bisphenol A. Environ Health Perspect 2010, 118, 1055–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermabessiere, L.; Dehaut, A.; Paul-Pont, I.; et al. Occurrence and effects of plastic additives on marine environments and organisms: A review. Chemosphere 2017, 182, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Jung, S.; Baek, K.; et al. Functional use of CO2 to mitigate the formation of bisphenol A in catalytic pyrolysis of polycarbonate. J HazaRd MateR 2022, 423, 126992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, T.R. (Micro)plastics and the UN sustainable development goals. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem 2021, 30, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kermoysan, G.; Joachim, S.; Baudoin, P.; et al. Effects of bisphenol A on different trophic levels in a lotic experimental ecosystem. Aquatic Toxicology 2013, 144–145, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-H.H.; Zhang, X.-M.M.; Wang, F.; et al. Occurrence of bisphenol S in the environment and implications for human exposure: A short review. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 615, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljevic, T.; Harner, T. Bisphenol A and its analogues in outdoor and indoor air: Properties, sources and global levels. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 789, 148013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W. Epidemiology in diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Endocrinol 2017, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glovaci, D.; Fan, W.; Wong, N.D. Epidemiology of Diabetes Mellitus and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2019, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.Y.; Fan, S.; Thiering, E.; et al. Ambient air pollution and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Res 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gómez-Toledano, R.; Delgado-Marín, M.; Cook-Calvete, A.; et al. New environmental factors related to diabetes risk in humans: Emerging bisphenols used in synthesis of plastics. World J Diabetes 2023, 14, 1301–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmler, H.-J.J.; Liu, B.Y.; Gadogbe, M.; et al. Exposure to Bisphenol, A.; Bisphenol, F.; Bisphenol S in U.S. Adults and Children: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2014. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 6523–6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xia, W.; Liu, W.; et al. Exposure to bisphenol A substitutes and gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study in China. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Liang, J.; Liao, Q.; et al. Associations of bisphenol exposure with the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a nested case–control study in Guangxi, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 25170–25180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx?BeginYear=2013 (2016, accessed 15 January 2022).

- Moreno-Gomez-Toledano, R.; Velez-Velez, E.; Arenas, I.M.; et al. Association between urinary concentrations of bisphenol A substitutes and diabetes in adults. World J Diabetes 2022, 13, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.C.; Mínguez-Alarcón, L.; Bellavia, A.; et al. Serum beta-carotene modifies the association between phthalate mixtures and insulin resistance: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2006. EnviRon Res 2019, 178, 108729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2013-2014 Laboratory Data - Continuous NHANES. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/datapage.aspx?Component=Laboratory&Cycle=2013-2014 (accessed 11 April 2023).

- Pirkle, J.L. Laboratory Procedure Manual Benzophenone-3, bisphenol A, bisphenol F, bisphenol S, 2,4-dichlorophenol, 2,5-dichlorophenol, methyl-, ethyl-, propyl-, and butyl parabens, triclosan, and triclocarban On line SPE-HPLC-Isotope dilution-MS/MS.

- Trasande, L.; Spanier, A.J.; Sathyanarayana, S.; et al. Urinary Phthalates and Increased Insulin Resistance in Adolescents. Pediatrics 2013, 132, E646–E655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahlhut, R.W.; van Wijngaarden, E.; Dye, T.D.; et al. Concentrations of urinary phthalate metabolites are associated with increased waist circumference and insulin resistance in adult U.S. males. EnviRon Health PeRspect 2007, 115, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Yu, S.H.; Lee, C.B.; et al. Effects of bisphenol A on cardiovascular disease: An epidemiological study using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2016 and meta-analysis. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 763, 142941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkle, J.L. Exposure of the US Population to Environmental Tobacco Smoke. JAMA 1996, 275, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzetti, S.; Curtin, P.; Just, A.C.; et al. _gWQS: Generalized Weighted Quantile Sum Regression_. R package version 3.0.4, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gWQS.

- Carrico, C.; Gennings, C.; Wheeler, D.C.; et al. Characterization of Weighted Quantile Sum Regression for Highly Correlated Data in a Risk Analysis Setting. J Agric Biol Environ Stat 2015, 20, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnota, J.; Gennings, C.; Wheeler, D.C. Assessment of weighted quantile sum regression for modeling chemical mixtures and cancer risk. Cancer Inform 2015, 14, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colicino, E.; Pedretti, N.F.; Busgang, S.A.; et al. Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances and bone mineral density: Results from the Bayesian weighted quantile sum regression. Environ Epidemiol 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, A. _qgcomp: Quantile G-Computation_. R package version 2.10.1, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=qgcomp.

- Rochester, J.R.; Bolden, A.L. Bisphenol S and F: A systematic review and comparison of the hormonal activity of bisphenol a substitutes. Environ Health Perspect 2015, 123, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramskov Tetzlaff, C.N.; Svingen, T.; Vinggaard, A.M.; et al. Bisphenols B, E, F, and S and 4-cumylphenol induce lipid accumulation in mouse adipocytes similarly to bisphenol A. Environ Toxicol 2020, 35, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorkiewicz, I.; Czerniecki, J.; Jarzabek, K.; et al. Cellular, transcriptomic and methylome effects of individual and combined exposure to BPA, BPF, BPS on mouse spermatocyte GC-2 cell line. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2018, 359, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.F.; Tariq, T.; Fatima, B.; et al. An insight into bisphenol A, food exposure and its adverse effects on health: A review. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1047827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.W.; Scammell, M.K.; Hatch, E.E.; et al. Social disparities in exposures to bisphenol A and polyfluoroalkyl chemicals: a cross-sectional study within NHANES 2003-2006. Environ Health 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargis, R.M.; Simmons, R.A. Environmental neglect: endocrine disruptors as underappreciated but potentially modifiable diabetes risk factors. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartle, J.C.; Navas-Acien, A.; Lawrence, R.S. The consumption of canned food and beverages and urinary Bisphenol A concentrations in NHANES 2003–2008. Environ Res 2016, 150, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.S.; Kwack, S.J.; Kim, K.B.; et al. Potential Risk of Bisphenol a Migration From Polycarbonate Containers After Heating, Boiling, and Microwaving. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2009, 72, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wu, M.; Shi, M.; et al. An Overview to Molecularly Imprinted Electrochemical Sensors for the Detection of Bisphenol, A. Sensors (Basel) 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Liang, J.; Liao, Q.; et al. Associations of bisphenol exposure with the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a nested case-control study in Guangxi, China. ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE AND POLLUTION RESEARCH. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hedderson, M.M.; Calafat, A.M.; et al. Urinary Phenols in Early to Midpregnancy and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Longitudinal Study in a Multiracial Cohort. Diabetes 2022, 71, 2539–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentor, A.; Wann, M.; Brunström, B.; et al. Bisphenol AF and bisphenol F induce similar feminizing effects in chicken embryo testis as bisphenol A. Toxicological Sciences 2020, 178, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.F.; Algonaiman, R.; Alduwayghiri, R.; et al. Exposure to Bisphenol A Substitutes, Bisphenol S and Bisphenol F, and Its Association with Developing Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Lee, Y.A.; Shin, C.H.; et al. Association of bisphenol A, bisphenol F, and bisphenol S with ADHD symptoms in children. Environ Int 2022, 161, 107093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marroqui, L.; Martinez-Pinna, J.; Castellano-Muñoz, M.; et al. Bisphenol-S and Bisphenol-F alter mouse pancreatic β-cell ion channel expression and activity and insulin release through an estrogen receptor ERβ mediated pathway. Chemosphere 2021, 265, 129051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Song, N.; et al. Occurrence, distribution and sources of bisphenol analogues in a shallow Chinese freshwater lake (Taihu Lake): Implications for ecological and human health risk. Sci Total Environ 2017, 599–600, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Lin, C.; et al. Socioeconomic and seasonal effects on spatiotemporal trends in estrogen occurrence and ecological risk within a river across low-urbanized and high-husbandry landscapes. Environ Int 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, J.; Han, L.; et al. Medium distribution, source characteristics and ecological risk of bisphenol compounds in agricultural environment. Emerg Contam 2024, 10, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palsania, P.; Singhal, K.; Dar, M.A.; et al. Food grade plastics and Bisphenol A: Associated risks, toxicity, and bioremediation approaches. J Hazard Mater 2024, 466, 133474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthra, K.T.; Chitra, V.; Damodharan, N.; et al. Microplastic emerging pollutants – impact on microbiological diversity, diarrhea, antibiotic resistance, and bioremediation. Environmental Science: Advances 2023, 2, 1469–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gómez-Toledano, R.; Jabal-Uriel, C.; Moreno-Gómez-Toledano, R.; et al. The “Plastic Age”: From Endocrine Disruptors to Microplastics – An Emerging Threat to Pollinators. Environmental Health Literacy Update - New Perspectives, Methodologies and Evidence [Working Title] 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Healthy (n=2965) | Diabetes (n=693) | p-value |

| Gender, men (%) | 1,389 (46.85) | 343 (49.50) | .112 |

| Age | 41.07 (40.43-41.71) | 57.08 (55.88-58.31) | .000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.8 (27.58-28.03) | 31.2 (30.69-31.72) | .000 |

| Mexican American | 434 (14.64) | 130 (18.76) | .000 |

| Other Hispanic | 317 (10.69) | 88 (12.70) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1125 (37.94) | 195 (28.14) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 640 (21.59) | 174 (25.11) | |

| Other Race - Including Multi-Racial | 449 (15.14) | 106 (15.30) | |

| Poverty-Income Ratio $ | 1.79 (0.83-3.81) | 1.53 (0.78-3.27) | .013 |

| Hypertension | 1043 (35.18) | 472 (68.11) | .000 |

| Dislipidemia | 993 (33.19) | 397 (57.29) | .000 |

| Smoking | 1266 (42.70) | 337 (48.63) | .003 |

| ΣBPs/Creat (µg/g) | 2.87 (2.78-2.97) | 3.2 (2.98-3.43) | .017 |

| ΣBP/Mol (nM) | 2.13 (2.03-2.23) | 2.21 (2.02-2.43) | .587 |

| Variable | Q1 (n= 914) | Q2 (n= 915) | Q3 (n= 915) | Q4 (n= 914) | p-value |

| Diabetes (%) | 157 (17.2) | 169 (18.5) | 175 (19.1) | 192 (21.0) | .208 |

| Gender, men (%) | 533 (58.3) | 420 (45.9) | 386 (42.2) | 393 (43.0) | .000 |

| Age | 41.6 (40.5-42.8) | 44.6 (43.4-45.8)** | 44.1 (42.8-45.3)** | 44.61 (43.4-45.8)** | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.3(27.9-28.7) | 28.2 (27.7-28.6) | 28.5 (28.1-28.9) | 28.7 (28.2-29.1) | |

| Mexican American | 139 (15.2) | 150 (16.4) | 144 (15.7) | 131 (14.3) | .000 |

| Other Hispanic | 86 (9.4) | 102 (11.1) | 110 (12.0) | 107 (11.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 307 (33.6) | 325 (35.5) | 344 (37.6) | 344 (37.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 192 (21.0) | 204 (22.3) | 199 (21.7) | 219 (24.0) | |

| Other Race - Including Multi-Racial | 190 (20.8) | 134 (14.6) | 118 (12.9) | 113 (12.4) | |

| Poverty-Income Ratio $ | 2 (0.9-4.1) | 1.8 (0.8-3.6) | 1.7 (0.8-3.6) | 1.6 (0.8-3.4)** | |

| Hypertension | 338 (37.0) | 396 (43.3) | 378 (41.3) | 403 (44.1) | .010 |

| Dislipidemia | 327 (35.8) | 352 (38.5) | 341 (37.3) | 370 (40.5) | .204 |

| Smoking | 360 (239.4) | 370 (40.4) | 419 (45.8) | 454 (49.7) | .000 |

| Variable | Q1 (n= 916) | Q2 (n= 915) | Q3 (n= 912) | Q4 (n= 915) | p-value |

| Diabetes (%) | 158 (17.2) | 195 (21.3) | 174 (19.1) | 166 (18.1) | .142 |

| Gender, men (%) | 416 (45.4) | 444 (48.5) | 450 (49.3) | 422 (46.1) | .274 |

| Age | 45.4 (44.2-46.7) | 44.8 (43.6-46) | 42.4 (41.2-43.6)** | 42.4 (41.2-43.6)*** | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1 (26.7-27.5) | 28.2 (27.8-28.6)**** | 29 (28.6-29.5)**** | 29.3 (28.9-29.8)**** | |

| Mexican American | 122 (13.3) | 131 (14.3) | 159 (17.4) | 152 (16.6) | .000 |

| Other Hispanic | 69 (7.5) | 110 (12.0) | 119 (13.0) | 107 (11.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 424 (46.3) | 342 (37.4) | 294 (32.2) | 260 (28.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 131 (14.3) | 183 (20.0) | 213 (23.4) | 287 (31.4) | |

| Other Race - Including Multi-Racial | 170 (18.6) | 149 (16.3) | 127 (13.9) | 109 (11.9) | |

| Poverty-Income Ratio $ | 2.4 (1 – 4.5) | 1.8 (0.9-3.5)**** | 1.5 (0.7-3.2)**** | 1.5 (0.7-3.3)**** | |

| Hypertension | 364 (39.7) | 395 (43.2) | 362 (39.7) | 394 (43.1) | .225 |

| Dislipidemia | 353 (38.2) | 366 (40.0) | 347 (38.0) | 324 (35.4) | .234 |

| Smoking | 372 (40.6) | 417 (45.6) | 409 (44.8) | 405 (44.3) | .142 |

| ΣBPs/Creat | ΣBPs / Mol | Glucose | HbA1c | Cholesterol | Cotinine | |

| ΣBPs / creat | 1 | ** | - | * | - | ** |

| ΣBPs / Mol | .391** | 1 | - | * | - | ** |

| Glucose | .033 | .031 | 1 | ** | - | * |

| HbA1c | .035* | 0.36* | .757** | 1 | - | * |

| Cholesterol | .009 | -.017 | .007 | .029 | 1 | - |

| Cotinine | .085** | .078** | -.040* | -.033* | -.015 | 1 |

| BP mixture | Covariates | OR (95 % CI) | p-value |

| ΣBPs / creat | 1 | 1.132 (1.038-1.235) | .005 |

| 2 | 1.102 (1.003-1.211) | .043 | |

| 3 | 1.103 (1.002-1.214) | .045 | |

| ΣBPs / Mol | 1 | 1.024 (0.960-1.092) | .468 |

| 2 | 1.024 (0.955-1.097) | .509 | |

| 3 | 0.989 (0.920-1.064) | .773 |

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |

| Variable | Ref. | OR (95% CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) |

| 1Diabetes (1) | Ref. | 1.09 (0.86-1.39) | 1.14 (0.90-1.45) | 1.28 (1.01-1.62)* |

| 1Diabetes (2) | Ref. | 1.01 (0.78-1.30) | 1.05 (0.81-1.36) | 1.16 (0.90-1.50) |

| 1Diabetes (3) | Ref. | 1.03 (0.80-1.34) | 1.10 (0.85-1.43) | 1.21 (0.93-1.56) |

| 2Diabetes (1) | Ref. | 1.30 (1.03-1.64)* | 1.13 (0.89-1.44) | 1.06 (0.84-1.35) |

| 2Diabetes (2) | Ref. | 1.27 (0.99-1.62) | 1.12 (0.87-1.45) | 1.04 (0.80-1.35) |

| 2Diabetes (3) | Ref. | 1.14 (0.89-1.48) | 0.98 (0.76-1.28) | 0.89 (0.68-1.17) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).