1. Introduction

Forest ecosystems are one of the largest pools of terrestrial biodiversity [

1] and one of the most important ecosystems providing ecosystem goods for human well-being. However, their integrity is endangered due to the rate of regression of their surface areas at the global level. Togo is not exempt from this trend.

In Togo, according to [

1], annual forest losses are estimated at 5236 ha/year, or about 0.4% of the national forest cover in 2015 [

2]. This degradation is far from insignificant, knowing that Togo is not a country with high forestry potential. The exploitation of biomass energy represents 50% of wood harvesting [

3]. It is one of the major environmental problems at the national scale because of its contribution to forest degradation and biodiversity loss. Indeed, several spontaneous forest species of high value under various anthropogenic pressures are threatened with extinction. Several biodiversity conservation programs are implemented through the reforestation of degraded landscapes (PNR, Togo 2017-2030, AFR 100, FFF). It must be noted that exotic species are the most solicited and represented in the framework of these large reforestation programs. This intense use of exotic species in reforestation campaigns is partly explained by the fact that the reproduction techniques of these species seem to be the best documented in the scientific literature at the national and international scale. Among these species, we can cite

Tectona grandis, Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Senna siamea, Azadirachta indica, Gmelina arborea [

4,

5].

Nevertheless, at the national scale, some studies for the development of natural resources are carried out to improve silvicultural techniques for the sustainable management of indigenous species of high economic potential. Thus, we can list

Detarium senegalense [

5],

Haematostaphis barteri, Lannea microcarpa and

Sclerocarya birrea [

6];

Lawsonia inermis [

7]. However, energy species are little discussed despite the impact of their harvesting on biodiversity. Indeed, several native energy species, such as

Uapaca togoensis (Euphorbiaceae), are threatened due to excessive cutting and receive little scientific attention.

Uapaca togoensis, with the synonym

Uapaca somon (Aubrev. & Léanchi) is a plant of the Euphorbiaceae family widely distributed in West and Central Africa. It is mainly found in edge forests and wooded savannas [

8]. It is a species with a very high potential value for medicinal use. Indeed, it is used in traditional medicine to treat pneumonia, cough, fatigue, fever, rheumatic pain, vomiting, and epilepsy [

9,

10]. Screening studies on the organs of this plant have confirmed its antibacterial [

10], larvicidal [

11], antifungal and antimicrobial [

12,

13], antiplasmodial [

12], and cytotoxic [

14] virtues. It is a species highly appreciated by nearly 80% of the population of the central region of Togo as an excellent firewood with easy combustion [

15]. Ecologically, it rejects vigorously by stumps and can be suckering [

16]. It also has an excellent ability to adapt to different types of soil [

17].

Nevertheless, in nature, the natural regeneration, especially the regeneration by seedlings of the species, is compromised by phytophagous parasites of the seeds and vegetation fires. Indeed, the early passage of fires destroys the inflorescences and the fruits or seeds. The plant also has a low regeneration capacity per collected seed, estimated at only 26% [

18,

19].

Uapaca wood is highly valued in Togo and mainly in the Central region for its calorific properties [

20] and is overexploited for domestic energy needs, hence its vulnerability in its natural habitat. Natural populations are in decline in Togo. In this situation, the species deserves not only to be protected in nature but also to be domesticated for forestry purposes. However, most specific studies on this species have focused on its uses [

13,

19] and rarely on its status, availability, or regeneration potential. By the way, the factors that may influence its capacity to germinate and regenerate by cuttings are not well known.

This study contributes to the sustainable management of natural resources by determining the optimal conditions for assisted regeneration of Uapaca togoensis. Specifically, it aims to: (i) analyze the factors influencing the germinative power of U. togoensis seeds and cuttings in Togo, (ii) determine the kinetics of budburst and germination per seed, and (iii) determine the calorific value of U. togoensis wood.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Classified forest of Alédjo and botanical garden of University of Lomé

The classified forest of Alédjo is located between the Central and Kara regions in an area of 785 ha. It benefits from a humid tropical climate with a rainfall of 800 to 1600 mm/year. Average monthly temperatures range from 24.7 to 28.6°C with an average relative humidity of 40% to 80%. The population is made up of the majority ethnic groups of Tém and Kabye, who live on income from agriculture, livestock, trade, and handicrafts. Slash-and-burn agriculture, livestock breeding, and hunting significantly modify the flora and fauna.

The experimental studies were carried out in the university botanical garden located on the campus of Lomé. The city of Lomé, the capital of Togo, is located on the coast of the atlantic ocean between longitudes 1°00' and 1°50' East and latitudes 6°50' and 6°05' North. The area benefits from a sub-equatorial climate with a bimodal regime and an average rainfall of 800 and 900 mm/year. The maximum temperatures recorded vary around 28°C while the minimums are below 25°C. Exotic species dominate the woody vegetation.

Vegetal material

The experiment involved seeds, stems, and roots (cuttings) of

U. togoensis (Figure 1). It is a plant of the Euphorbiaceae family widely distributed in West and Central Africa. It grows in forest edge formations and wooded savannahs [

8]. It is an evergreen tree of about 20 m in height, with reddish brown wood. For this experiment, the seeds (fruits) used for germination tests were collected under seed trees to ensure their maturity. As for the cuttings segments, they were taken from the roots and stems of adult plants. The roots were dug up and cut from the base of their insertions not to confuse them with the roots of other species. Root and stem cuttings of about 15 cm in length and 1 to 4 cm in diameter were cut, packed immediately in aerated bags, and transported to the Laboratory of Botany and Plant Ecology of the University of Lomé. The study took place between August and December 2021 at the Botanical Garden of the University of Lome. All the plant material (seeds, roots, and stems) came from trees previously geo-referenced in the framework of a previous study in the classified forest of Alédjo on the diversity, structure, and regeneration modes of

U. togoensis in Togo [

18].

2.2. Determination of dry calorific value

The calorific value was determined from samples of dry wood slices of the species

U. togoensis, whose mass varies between 350g and 500g (

Figure 2). The samples were taken from wood trunks from the wood markets located along the national road number 1 (N1) between Sokodé and Alédjo in the Central Region of Togo. The samples were selected according to their diameter (D) and classified into five categories: D <10; 10<D< 15; 15<D<20; 20<D<25, and D> 25. After labeling, these samples were sent to the Solar Energy Laboratory of the University of Lomé for analysis. The average Lower Heating Value (LHV) in Megajoule per kilogram of dry matter (Mj/kg) was estimated after five (5) measurements for each sample of fuel wood at 0% moisture, using a calorimetric bomb in accordance with the NF M03-005 standard [

21].

2.3. Germination tests of the seeds

2.3.1. Seeds treatment

The seeds were extracted from the fruits and sorted according to their apparent quality. Two types of seeds were used for the experiment. They are untreated seeds (tegumented seeds) extracted from the fruits without treatment, and detegumented seeds or scarified seeds, i.e., seeds freed from their endocarp pulp. A second sorting step was applied, this time only to the scarified seeds, during which the seeds without cotyledons were discarded and counted, then the rest with cotyledons were sorted again to separate the good cotyledons from the moldy ones. Of 835 scarified seeds, only 701 seeds, or 84%, contained grains or cotyledons, of which about 217 seeds appeared to be good, or 26% good seeds.

2.3.2. Sowing of seeds

The experiment consisted in sowing 20 untreated and 20 scarified seeds of Uapaca togoensis in plastic germinators at a depth equal to twice the diameter of the seed. Watering was done regularly every 72 hours from the day of Sowing. For this study, four types of substrates were tested, namely: washed sea sand, garden soil, sieved potting soil and standard compost. The germinators were filled to 3/4 of their capacity with these different types of substrates, and each test was repeated four times, i.e. four germinators of twenty seeds per substrate type respectively of scarified and unscarified seeds. The germinators are labeled and classified linearly according to the treatments and according to the substrates.

2.3.3. Root and stem cuttings tests

Influence of substrates on the budding potential of U. togoensis (Trial 1)

The cuttings were not pre-treated before planting. The stem cuttings were pricked obliquely and individually into 15 x 7 cm plastic pots for the test. In contrast, root cuttings were planted vertically and horizontally, taking care to cover three-quarters of the diameter or completely. Four types of substrates were used: washed sea sand, garden soil, sieved potting soil, and enriched compost. Each test was repeated ten times for each substrate type with 40 root cuttings and 40 stem cuttings.

Influence of the diameter of the cuttings (Trial 2)

The Influence of the diameter of the cuttings on the development was evaluated using only garden soil as the substrate to avoid the type of substrate had any effect on the results. Three lots of ten cuttings were taken: small diameter cuttings (stem tips) with a diameter of 2 Cm, medium diameter cuttings with a diameter between 2 and 3 cm, and large diameter cuttings with a diameter between 3 and 4 cm.

Influence of sunlight and a plastic bag on cuttings (Trial 3)

The effect of sunlight exposure and terminal tip protection was evaluated using two batches of 50 cuttings of medium diameter. Twenty-five (25) were left unprotected at the terminal tip, while a plastic film protected the other 25. Two beds were set up on garden soil: one exposed to direct sunlight and the other under natural shade created by a small shed of palm branches and the canopy of surrounding trees. This device allows for limiting the exposure of the cuttings to the outside light and maintaining a relatively low temperature.

2.3.4. Germination data collection

Daily and morning observations are made to count the germinated seeds and the appearance of buds or leaves on the cuttings. The information collected is the number of germinated seeds of the day per germinator, the number of buds per cutting, the appearance of leaves, and the number of leaves per bud.

2.3.5. Processing and analysis of germination data

The data collected on the different factors influencing U. togoensis germination were entered and coded in a Microsoft Excel table to calculate qualitative and quantitative parameters related to germination. The following parameters were considered:

Germination/budburst rate: (n=Number of germinated seeds and N=Total number of germinated seeds); the duration of germination (germination/cutting) seed in days: the difference between the date of the first day and the date of the last day of germination; the formula applied is the following one:

Dg = Dn- D1

Where Dn=last day of germination and D1 = first day of germination

the time of germination (germination / cutting) in days is still called latent life and corresponds to the time elapsed between the Sowing and the first germination [

22].

DL = D1-D0

D1 = day of the first germination; D0= day of sowing

The speed of germination (germination/planting) can be expressed by the meantime of germination (MTG), i.e. the time after which 50% of the germinated seeds are reached[

23]. In the case of the present study, for each treatment, the speed of germination of seeds was calculated using the following formula [

24]

V=Where V =germination rate in number of germs per day, G1: number of germs of the day and Di = number of days after Sowing.

The germination capacity (the maximum germination percentage obtained concerning the duration of the experiment).Where Gmax=maximum germination in % and D =the total duration of the experiment

The number of budding: it is the average number of buds per cutting;

The kinetics of bud break: the number of buds and foliage as a function of time;

The values of the parameters thus determined were subjected to a test of homogeneity and significance ANOVA on STATA 12 to determine the correlations between the various germination parameters.

Figure 1.

Experimental materials, A: seeds; B: stems; C: roots; D: washers.

Figure 1.

Experimental materials, A: seeds; B: stems; C: roots; D: washers.

3. Results

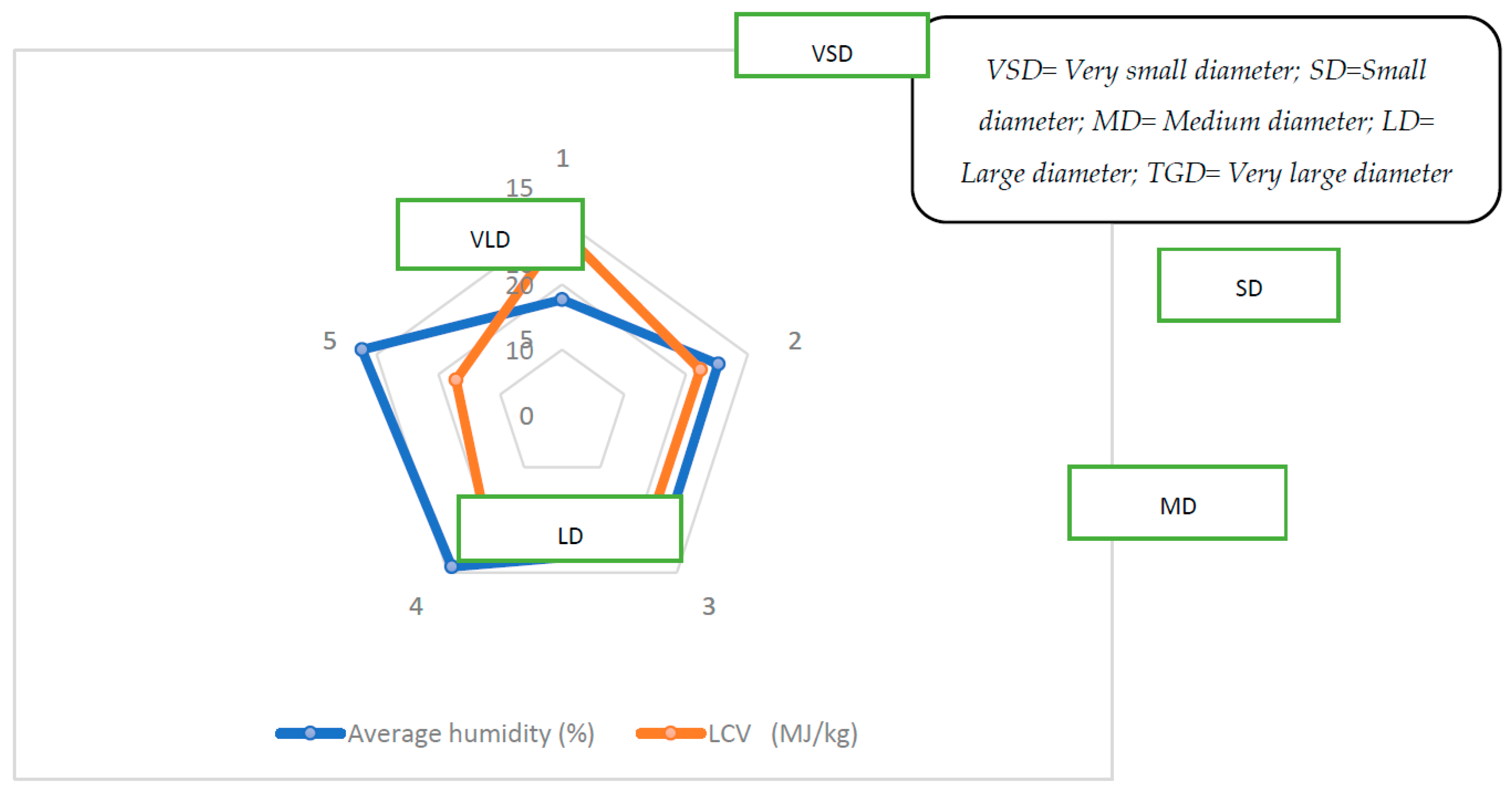

3.1. Lower calorific value (LCV) analysis of dry wood of Uapaca togoensis

The average calorific value per diameter class of dry wood of U. togoensis varies strongly between 7,35 and 12,12 Mj/Kg while the average humidity rate per class is between 17.67% and 32.36% (Table 1).

Analysis of

Table 1 reveals that the small and very small diameter wood classes are the most heat producers, releasing an average of 12.12 Mj/Kg and 9.55 Mj/Kg, respectively. The average energy released by large and medium-diameter wood is considered low, 7.35 Mj/Kg and 8.60 Mj/Kg, respectively. The analysis of the ANOVA correlation test indicates a very strong influence of the diameter size of the logs on the lower calorific value of dry wood of

U. togoensis (Pvalue=0.000).

Indeed, the smaller the diameters, the more energy the puck produces. There is no relationship between the LCV of wood and the average mass of the dry wood sample (r=0.16) regardless of diameter (

Figure 3). In contrast to the average mass by diameter class, humidity content appears to have an excellent positive linear correlation (r = 0.99) on LCV (

Figure 3). The size of the stem diameter also influences the humidity content. The larger the diameter, the wetter the stem and the lower its LCV. The ANOVA analysis indicates that the presence or absence of bark does not influence the LCV of

U. togoensis wood (Pvalue=0.606).

Table 1.

Summary table of the lower calorific value analysis of dry wood of Uapaca togoensis.

Table 1.

Summary table of the lower calorific value analysis of dry wood of Uapaca togoensis.

| Class of diameter |

Diameter (cm) |

With bark (1)/without bark (0) |

Humidity h (%) |

Average humidity (%) |

LCV (Mj/Kg) |

| Very small |

7 |

0 |

16,056 |

17,677 |

12,122 |

| Very small |

8,4 |

0 |

16,752 |

| Very small |

7,8 |

1 |

20,224 |

| Small |

12,1 |

1 |

29,1111 |

25,186 |

9,559 |

| Small |

13,5 |

1 |

24,385 |

| Small |

12,8 |

1 |

22,062 |

| Medium |

13 |

0 |

18,161 |

28,904 |

8,607 |

| Medium |

15,4 |

1 |

39,310 |

| Medium |

16 |

0 |

29,241 |

| Large |

20,6 |

1 |

31,481 |

32,367 |

7,358 |

| Large |

22 |

1 |

34,042 |

| Large |

24 |

1 |

31,578 |

| Very Large |

24 |

1 |

37,820 |

25,603 |

9,492 |

| Very Large |

26 |

0 |

20,041 |

| Very Large |

24 |

0 |

18,947 |

Figure 2.

Diagram of the Influence of diameter size on humidity rate and lower calorific value.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the Influence of diameter size on humidity rate and lower calorific value.

Figure 3.

Evolution of LCV as a function of humidity (A) and weight (B).

Figure 3.

Evolution of LCV as a function of humidity (A) and weight (B).

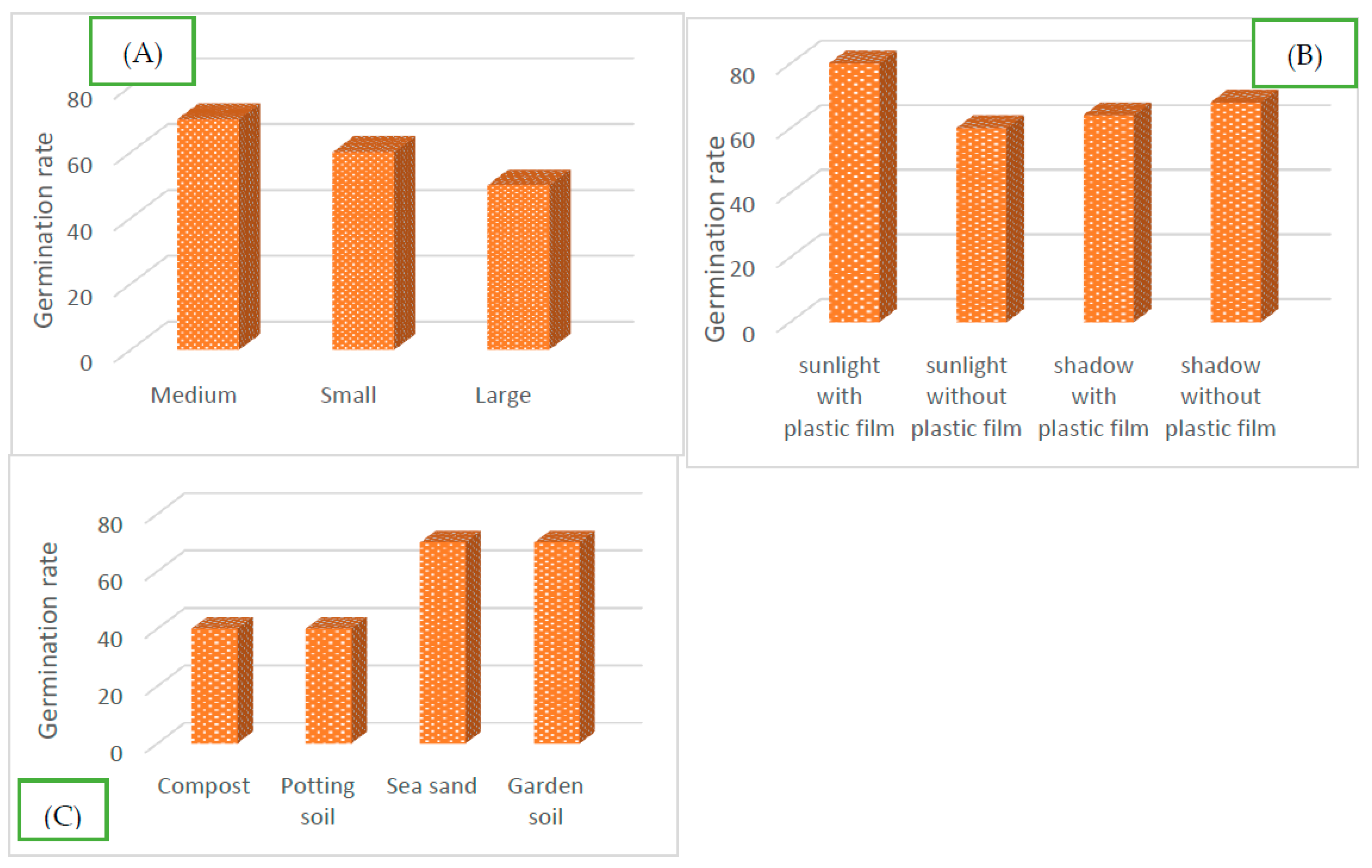

2.2. Assessment of seed germination capacity

A single unscarred seed with a germination rate of 0.00312% germinated after 20 days of experimentation and bore leaves. This germination is recorded in the standard compost. The analysis of this experimental result reveals a low capacity of regeneration by seeds of U. togoensis.

2.3. Assessment of root budding ability

Only one root cutting of medium diameter (i.e. 0.014%) germinated and bore leaves. This germination is recorded on the cuttings in the garden soil after 34 days of the experiment.

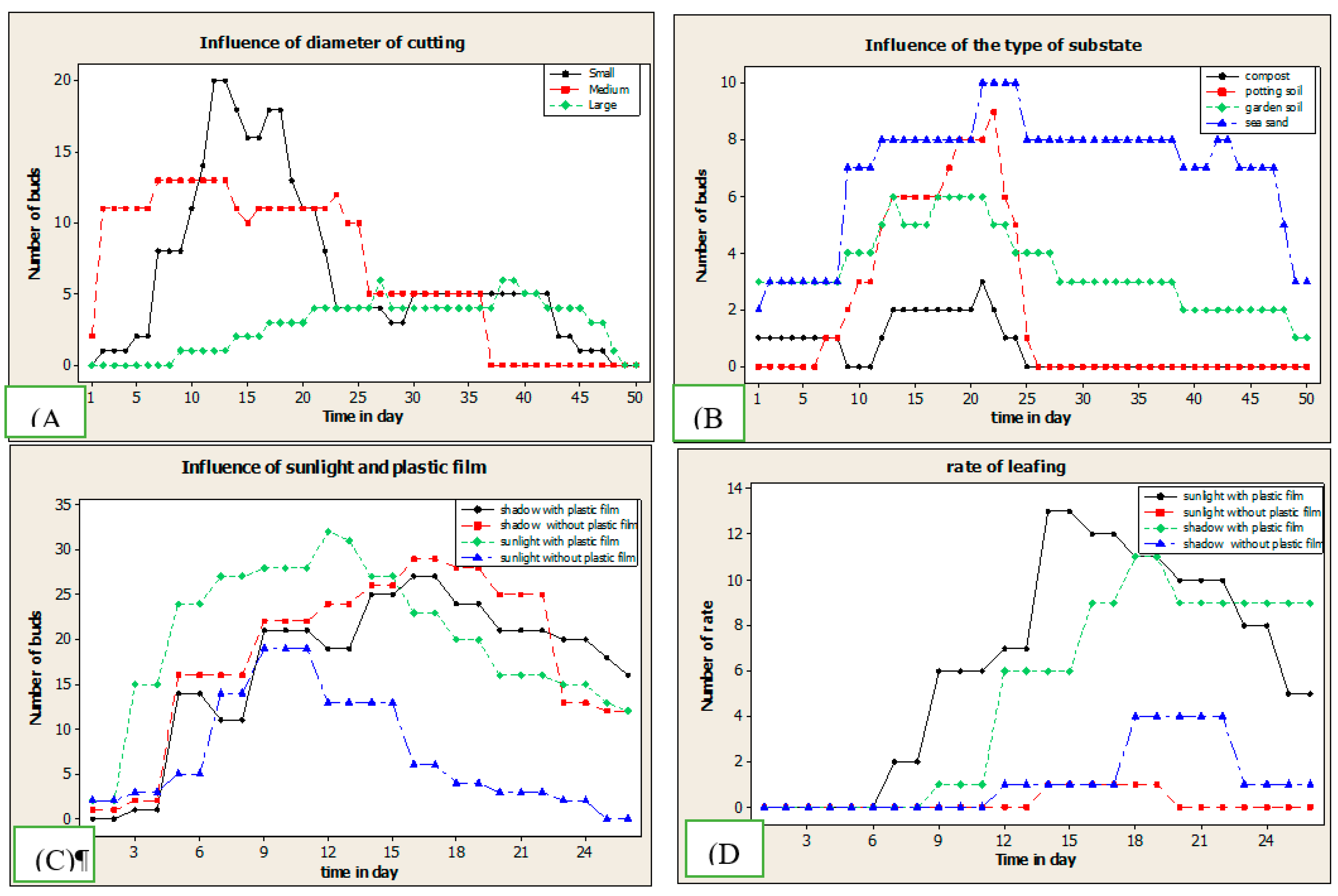

2.3. Assessment of bud break capacity per stem

2.3.1. Influence of substrate type and diameter size

Stem cuttings, whatever the diameter, bud perfectly. However, the budding remains under the Influence of the substrate type used and the cuttings' diameter. The budding is maximal in sea sand and garden soil, i.e. 70% of the stem segments bud as opposed to only 40% in standard compost and sifted soil. Also, the medium diameter cuttings are the most favorable to cutting, i.e. more than 70% against 60% and 50%, respectively for the small and large diameter segments. The analysis of variance ANOVA indicates a very significant influence of the type of substrate and the diameter segments on the ability of U. togoensis stems to bud (Prob>chi2 =0.0000).

2.3.2. Influence of plastic film and sunlight

The budburst rate of unplasticized stem segments was highest (70%) in sea sand and garden soil and low (40%) in sieved compost and potting soil (

Figure 4). However, these different budburst rates increase significantly from 40% to 50% in compost and sieved potting soil and from 70% to 90% in sea sand, for cuttings protected by plastic film. The highest budburst rate (90%) was recorded on the cuttings pricked out in sea sand and weak, only 40% in standard compost in the presence of plastic film.

The analysis of the results reveals that the plastic film covering the aerial tip of the cuttings also has a significant influence on the capacity and kinetics of budding of U. togoensis (Prob>chi2 = 0.0000).

The sunlight has a significant influence on the capacity and the timing of the budburst of the stem segments of

U. togoensis (Prob>chi2 = 0.000) (

Table 2). The maximum budburst rate reached 80% on the cuttings exposed to sunlight against only 60% for the segments in the shade (

Figure 4). The budding delay is minimal, i.e. one day when the segments are exposed to the sun. The budding delays varied between one (1) day (81% of the trials) and 7 days. The longest delay is 7 days observed on exposed but uncovered cuttings planted in sieved potting soil.

Table 2.

Summary table of the analysis of the parameters of positive correlations of Uapaca togoensis.

Table 2.

Summary table of the analysis of the parameters of positive correlations of Uapaca togoensis.

| Source |

SS |

MS |

F |

Prob > F |

Prob>chi2 |

| Plastic |

15,07 |

15,07 |

12,53 |

0,0003 |

0,000 |

| Size |

91,54 |

91,54 |

66,70 |

0,0000 |

0,000 |

| Substrate |

220,12 |

73,37 |

67,87 |

0,0000 |

0,000 |

| Exhibition |

17,11 |

5,705 |

28,33 |

0,0000 |

0,000 |

2.3.3. Budding kinetics

The budding delay of

U. togoensis cuttings is generally short. The minimum delay is only one (1) day with a maximum of 33 buds accumulated in 11 days of experiment (

Figure 6). This minimum delay of budburst of 1 day is unanimous for all the cuttings only in the garden soil and in the sea sand. However, it reaches 5 days in compost and sieved potting soil. The results of the ANOVA tests indicate a very significant influence of the type of substrate and plastic film on the budburst delay (Prob>chi2 =0.0000). Indeed, the delay of budburst varies from 1 day for small and medium diameter cuttings to 7 days for large diameter cuttings.

The kinetic curves of budburst are characterized by three stages. A phase of increase, a phase of stabilization and finally a phase of regression of the number of cuttings. Between the first and the fifth day, the budding is weak. The number of buds increases strongly between the fifth (5) and the tenth (10) day (

Figure 6). A small variation is observed on the number of buds of the cuttings planted in the compost. The maximum cumulative budding (32) is observed on the buds on day eleven on both exposed and covered cuttings.

2.4. Assessment of leafing kinetics

A portion of the cuttings burst produced leaves under all experimental conditions. The rate of leafing varied from 0.08% (2 cuttings) to 60% for unplasticized cuttings and cuttings plasticized and exposed in sea sand, respectively. The highest leafing rates of 60% and 48% are recorded in sea sand and garden soil, respectively. Sea sand recorded the highest leafing rates in the presence or absence of the protective film, 60% and 30%, respectively.

The analysis of

Figure 3 (D) on the kinetics of foliage of

U. togoensis cuttings showed different effects in front of the various treatments and parameters such as the type of substrate, the sunshine, and the coverage of the aerial tip of a plastic bag. Indeed, the uncovered cuttings showed a much longer leafing time (13 days) than those exposed to the sun and protected by a plastic film (6 days). The average leafing time was 11 days for the protected cuttings and 20 days for the uncovered ones.

2.5. Roots budding

Daily observations of the cuttings revealed the appearance of root buds on the buried tip on 2% of the cuttings. These buds appeared only on cuttings planted in garden soil substrates.

The regeneration experiment of

U. togoensis cuttings was compromised by termite attack on almost all cuttings. The attacks occurred on cuttings that were still fresh, whether or not they were Broken. These attacks are recorded on the cuttings pricked in the substrates, garden soil, compost, and sifted soil. Nevertheless, no attack is recorded on cuttings pricked in sea sand.

Figure 5.

Illustration of termite activity and its Influence on the survival of cuttings.

Figure 5.

Illustration of termite activity and its Influence on the survival of cuttings.

Figure 6.

Budburst kinetics. Influence of (A) stem diameter, (B) type of substrate and Influence of sunlight and plastic film(C) on Number of bunds (D) number of rate.

Figure 6.

Budburst kinetics. Influence of (A) stem diameter, (B) type of substrate and Influence of sunlight and plastic film(C) on Number of bunds (D) number of rate.

4. Discussion

The calorific value of

U. togoensis wood varies significantly according to the humidity rate and ranges from 12.12 Mj/Kg to 7.35 Mj/Kg respectively at 17.67% and 32.36% humidity. This observation is not exclusive to

U. togoensis wood. The study [

25] mentions that the LCV of wood fuel varies proportionally according to the humidity rate, which can vary from 18 MJ.kg-1 at 5% of humidity to 9,5 MJ.kg-1 for 45% of humidity[

25]. Nevertheless, the highest average LCV of

U. togoensis wood is relatively low compared to several energy species in West Africa. According to [

25],

Crossopterix febrifuga and Burkea africana produce a LCV greater than 20 Mj/Kg or

Parkia biglobosa with 18 Kj/Kg. The low LCV of

U. togoensis wood would justify its only choice as fuelwood rather than charcoal. Indeed, a species of wood fuel is chosen based on its calorific value, it's capacity to burn slowly [

26] and a low smoke or spark emission [

27]. The burning speed also depends on the density of the wood species [

21]. The same criteria for choosing energy species are applied

Vitellaria paradoxa in Senegal [

21,

28]. This result corroborates with the work of [

20], which shows the appreciation of

U. togoensis wood in Togo as excellent fuelwood because the species allows the rapid cooking of food and therefore has a high calorific value.

A single untreated seed germinated after 33 days of experimentation. The germination rate is too low compared to the 60% and 32% obtained by [

18]on seeds from harvested and collected fruits, respectively. The time and storage conditions of the seeds, which can affect and deteriorate the quality of the seeds, are suspected because of the low germination rate of the seeds. The hypothesis of the conditions of conservation of seeds and the parasites would justify the 84% moldy or defective seeds identified during the scarification and sorting. The germination time of 33 days is comparatively high than the 11 days obtained by [

18]. The negative correlation between germination time and storage time is demonstrated on

U. bojeri [

29] or

U. thouarsii or on

Detarium senegalense [

5]. The rate of root budding is too low compared to those obtained on

Vitex donania [

30,

31] in Benin and on

Securidaca longipedonculata [

32].

The budburst and leafing of the various stem and root cuttings of

U. togoensis shows its potential for vegetative regeneration. Only one medium-diameter root cutting budded in garden soil and bore leaves after 34 days. The low budding rate of root cuttings is probably a physiological or genetic predisposition of the species

U. togoensis. However, the species shows in nature a vigorous stump-rejection ability and a suckering capability [

16,

18].

The best substrates for budding of

U. togoensis stems are sea sand and garden soils. The physical characteristics of these substrates concerning their relatively acceptable moisture retention capabilities could influence the ability of stems to bud. The Influence of the water content of a substrate on the budding of cuttings, which is responsible for a good water supply of the cuttings, has been demonstrated by [

33]. Indeed, plant seeds preferentially seek substrates with properties and hydromorphic or xeromorphic characteristics similar to those of their ecosystem of origin [

30,

32,

34]. Nevertheless, sea sand is a porous and light substrate characterized by a low water retention capacity and a good circulation of water and oxygen.

On the other hand, the garden soil is ecologically close to the soil of dense dry forests or wooded savannahs, similar to the ecological environment of distribution of

U. togoensis. The physical properties of the substrate used can strongly influence the regeneration capacity of the cuttings of the plant species. Thus, porous and light substrates are considered the best substrates for cuttings and rooting of

Vitex doniana; [

30] or

Dacryodes edulis, [

35,

36]. The poor Influence of sieved potting soil and standard compost substrates is probably related to their physicochemical composition. Indeed, the high concentration of nitrates, nitrites, or other chemical elements could also reduce the capacity of a good water supply and thus affect the bud break. This could act by osmosis phenomenon and seriously dehydrate the cuttings.

The diameter of the cuttings is a characteristic influencing the budburst of

U. togoensis stems. Medium-diameter cuttings are the most suitable and adapted to budburst. The Influence of the size of the cuttings on the ability to bud is thought to be related to their physicochemical composition or the content of accumulated starch reserves [

31,

32]. Nutrient reserves of starch stimulate and promote bud formation [

31]. Medium-diameter cuttings are more favorable for budburst and foliage formation. These results allow us to put forward the hypothesis that the middle parts of the stems contain a large number of latent buds of optimal maturity [

32]. This hypothesis is confirmed by the work of [

37] on cuttings from young branches of

Piliostigma reticulatum. The minimum delay of budburst and foliage set is relatively short for

U. togoensis, respectively, one (1) day and six (6) days. Similar results were reported by [

38] on

Jatropha curcas.

5. Conclusions

In the light of the indications obtained, the vegetative propagation of U. togoensis is possible and more efficiently by stem cuttings than by root cuttings. The parameters influencing the budding and leafing of the stems are the type of substrate used, the diameters of the cuttings and the protection of the terminal tips by a plastic film. The best substrates are sea sand and garden soil. Nevertheless, the protection of the terminal end of the cuttings and the exposure to the sun are conditions which improve the yield of budding of the stems. The calorific value of U. togoensis wood varies proportionally to the humidity rate, ranging from 12.12 Mj/Kg to 7.35 Mj/Kg respectively at 17.67% and 32.36% humidity, which proves that it is an excellent firewood that deserves to be valorized. The results obtained can be used to develop silvicultural programs for U. togoensis. However, further research is needed to determine the best conditions for seed conservation and in situ seeding power.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the experimental design, data collection and analysis, and writing and editing of the manuscript. NL and FF collected plant materials, performed germination tests, and initial data analysis. NL, FF, and LY also performed the laboratory analysis of the lower heating value of dry U. togoensis wood. All authors contributed to the proofreading and editing of the manuscript. The supervision of the research was done by KD, PH, KD, LY, WK, BK, and AK. All authors read and accepted the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this work express their deep gratitude to the Support Program for the Fight against Climate Change (PALCC), a program financed by the European Union and the Togolese government for their financial support in the realization of this study. We are also grateful to the managers of the Laboratory of Botany and Plant Ecology of the University of Lomé for their technical support. The authors cannot forget all the actors who contributed during the field work, the collection of cuttings, and the installation of the nursery.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- MERF-REDD+. Niveau de référence des forêts (NRF) du Togo; 2020.

- MERF. Evaluation des politiques et mesures d’atténuation des changements climatiques mis en œuvre par le Togo dans le secteur de la Foresterie et autres Affectations des Terres (FAT) en vue de réduire les émissions des gaz à effet de serre dudit secteur dans le cadre de la Quatrième Communication Nationale (4CN) et le Deuxième Rapport Biennal Actualisé (2RBA) sur les changements climatiques; 2021.

- MERF-REDD+. Processus d’élaboration et manuel d’utilisation du Système d’Information sur la filière Bois Energie; 2017.

- Akpene, A.D.; Chaix, G.; Monteuuis, O.; Langbour, P.; Guibal, D.; Tomazello, M.; Kokutse, A.; Kokou, K. Mise au point d’une stratégie d’amélioration des plantations de teck au Togo. In Proceedings of the Conférence Matériaux 2014-Colloque Ecomatériau; 2014; p. 10 p. [Google Scholar]

- Sogo, M.; Etsè, K.; Kamou, H.; Bammite, D.; Padakali, E.; Guelly, K. Caractéristiques germinatives des graines et vitesse de croissance des jeunes plants de deux espèces forestières au Togo: Detarium senegalense JF Gmel.(Fabaceae) et Mansonia altissima (A. chev.) A. Chev.(Sterculaceae). Afrique science 2017, 13, 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Agbogan, A.; Bammite, D.; Wala, K.; Bellefontaine, R.; Dourma, M.; Akpavi, S.; Woegan, Y.; Tozo, K.; Akpagana, K. Regeneration naturelle d’un fruitier spontane: Lannea microcarpa Engl. et K. Krause au nord du Togo. Agronomie Africaine 2017, 29, 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.N.; Quashie, M.A.; Radji, R.; Segla, K.N.; Adjonou, K.; Kokutse, A.D.; Kokou, K. Etude de la germination de Lawsonia inermis L. sous différentes contraintes abiotiques. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 2019, 13, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkill, H. The useful plants of West Africa. Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew 1985, 1, p319. [Google Scholar]

- Olorukooba, A.B.; Chindo, B.A.; Ejiofor, J.I.; Maiha, B.B. Effect of fractions from the methanol stem bark of Uapaca togoensis (Pax) on oxidative indices in Plasmodium berghei infected mice. Journal of Pharmaceutical Development and Industrial Pharmacy 2021, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Koné, W.M.; Atindehou, K.K.; Kacou-N, A.; Dosso, M. Evaluation of 17 medicinal plants from Northern Cote d'Ivoire for their in vitro activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines 2007, 4, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azokou, A.; Koné, M.W.; Koudou, B.; Tra Bi, H.F. Larvicidal potential of some plants from West Africa against Culex quinquefasciatus (Say) and Anopheles gambiae Giles (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Vector Borne Diseases 2013, 50, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Olorukooba, A.; Maiha, B.; Chindo, B.; Ejiofor, J.; Hamza, A. Antiplasmodial studies on the ethyl acetate fraction of the stem bark extract of Uapaca togoensis Pax.(Euphorbiaceae) in mice. Bayero Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 2016, 9, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seukep, J.; Sandjo, L.; Ngadjui, B.; Kuete, V. Antibacterial activities of the methanol extracts and compounds from Uapaca togoensis against Gram-negative multi-drug resistant phenotypes. South African Journal of Botany 2016, 103, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuete, V.; Sandjo, L.P.; Seukep, J.A.; Zeino, M.; Mbaveng, A.T.; Ngadjui, B.; Efferth, T. Cytotoxic compounds from the fruits of Uapaca togoensis towards multifactorial drug-resistant cancer cells. Planta Medica 2015, 81, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainge, M.N.; Nchu, F.; Peterson, A.T. Diversity, above-ground biomass, and vegetation patterns in a tropical dry forest in Kimbi-Fungom National Park, Cameroon. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dourma, M.; Wala, K.; Bellefontaine, R.; Batawila, K.; Guelly, K.-A.; Akpagana, K. Comparaison de l'utilisation des ressources forestières et de la régénération entre deux types de forêts claires à Isoberlinia au Togo. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Adiza, A. Etude d’une recette traditionnelle, des écorces de tronc de Sclerocarya birrea Hosch et de Uapaca togoensis Pax utilisées dans le traitement du diabète. Mém. Doctorat Pharmacie, Université Bamako, Mali, 141p 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miberkassa, B. Diversite, Structure, Modes De Regeneration Et Usages De Uapaca Togoensis Pax (Euphorbiaceae) Dans La Région Centrale Au Togo,. université de Lomé, 2017.

- Olivier, M.; Zerbo, P.; Boussim, J.I.; Guinko, S. Les plantes des galeries forestières à usage traditionnel par les tradipraticiens de santé et les chasseurs Dozo Sénoufo du Burkina Faso. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 2012, 6, 2170–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaina, A.; Wala, K.; Koumantiga, D.; Folega, F.; Koffi, A. Impact de l'exploitation du bois-énergie sur la végétation dans la préfecture de Tchaoudjo au Togo. Revue de Géographie de l’Université de Ouagadougou 2018, 1, 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, A.; Coulibaly-Lingani, P.; Lamien, N. Préférences des femmes et pouvoir calorifique d’essences de bois d’énergie utilisées pour la caisson de la bière locale et du beurre de karité au Burkina Faso. Journal of Applied Biosciences 2020, 156, 16139–16146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmahioul, B.; Khelil, B.; Kaïd-Harche, M.; Daguin, F. Étude de la germination et de l’effet du substrat sur la croissance de jeunes semis de I L. Germination study and substrate effect on the growth of young seedlings of Pistacia vera L. Acta Botanica Malacitana 2010, 35, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Côme, D. Obstacles to germination. Obstacles to germination. 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, F.S.; Watson, C.E.; Cabrera, E.R. Seed vigor testing of subtropical corn hybrids. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidou, S.; Nzihou, J.; Bouda, M.; Rogaume, T.; Koulidiati, J.; Segda, B. Contribution à l’évolution du pouvoir calorifique inférieur du déchet modèle des pays en développement: cas de la fraction combustible des ordures ménagères (OM) du Burkina Faso. Sciences et Structure de la Matière 2013, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ajonina, G.; Usongo, L. Preliminary quantitative impact assessment of wood extraction on the mangroves of Douala-Edea Forest Reserve, Cameroon. Tropical biodiversity 2001, 7, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Folefack, D.P.; Abou, S. Commercialisation du bois de chauffe en zone sahélienne du Cameroun. Science et changements planétaires/Sécheresse 2009, 20, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gning, O.N.; Sarr, O.; Gueye, M.; Akpo, L.E.; Ndiaye, P.M. Valeur socio-économique de l’arbre en milieu malinké (Khossanto, Sénégal). Journal of Applied Biosciences 2013, 70, 5617–5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randrianavosoa, H.; Andrianoelina, O.; Ramamonjisoa, L. Tolérance à la dessiccation des graines d’Uapaca bojeri, Euphorbiaceae. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 2011, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapongmetsem, P.M.; Fawa, G.; Noubissie-Tchiagam, J.B.; Nkongmeneck, B.A.; Biaou, S.H.; Bellefontaine, R. VEGETATIVE PROPAGATION Of VITEX DONIANA SWEET fROM ROOT SEGMENT CuTTINGS. BOIS & FORETS DES TROPIQUES 2016, 327, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sanoussi, A.; Ahoton, L.; Odjo, T. Propagation of Black Plum (Vitex donania Sweet) Using Stem and Root Cuttings in the Ecological Conditions of South Benin. Tropicultura 2012, 30. [Google Scholar]

- OUMAROU, Z.H.; HAMAYA, Y.; TSOBOU, R.; ABDOULAYE, H.; BELLEFONTAINE, R.; MAPONGMETSEM, P.M. Multiplication végétative de Securidaca longepedunculata Fresen par bouturage de segments de racine. Afrique Science 2018, 14, 388–399. [Google Scholar]

- Grange, R.; Loach, K. Environmental factors affecting water loss from leafy cuttings in different propagation systems. Journal of Horticultural Science 1983, 58, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loach, K. Rooting of cuttings in relation to the propagation medium. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mialoundama, F.; Avana, M.; Youmbi, E.; Mampouya, P.; Tchoundjeu, Z.; Mbeuyo, M.; Galamo, G.; Bell, J.; Kopguep, F.; Tsobeng, A. Vegetative propagation of Dacryodes edulis (G. Don) HJ Lam by marcots, cuttings and micropropagation. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods 2002, 12, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elomo, C.; Nguénayé, B.; Tchoundjeu, Z.; Assah, E.; Tsobeng, A.; Avana, M.-L.; Bell, M.J.; Nkeumoe, F. Multiplication végétative de Dacryodes edulis (G. Don) HJ Lam. par marcottage aérien. Afrika focus 2014, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Traore, M. Etude de la phénologie, de la régénération naturelle et des usages de Piliostigma reticulatum (DC) Hochst en zone Nord soudanienne du Burkina Faso. Mémoire de fin de cycle, Institut du Développement Rura1IUniversité Polytechnique de Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 68p 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Thiam, A.; Samba, S.A.N.; Samb, C.O.; Niang, A. Multiplication par bouturage de Jatropha curcas L.: influence du nombre de nœuds, du diamètre, de la durée et du temps de conservation des boutures. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 2019, 13, 2573–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).