Submitted:

23 February 2024

Posted:

23 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

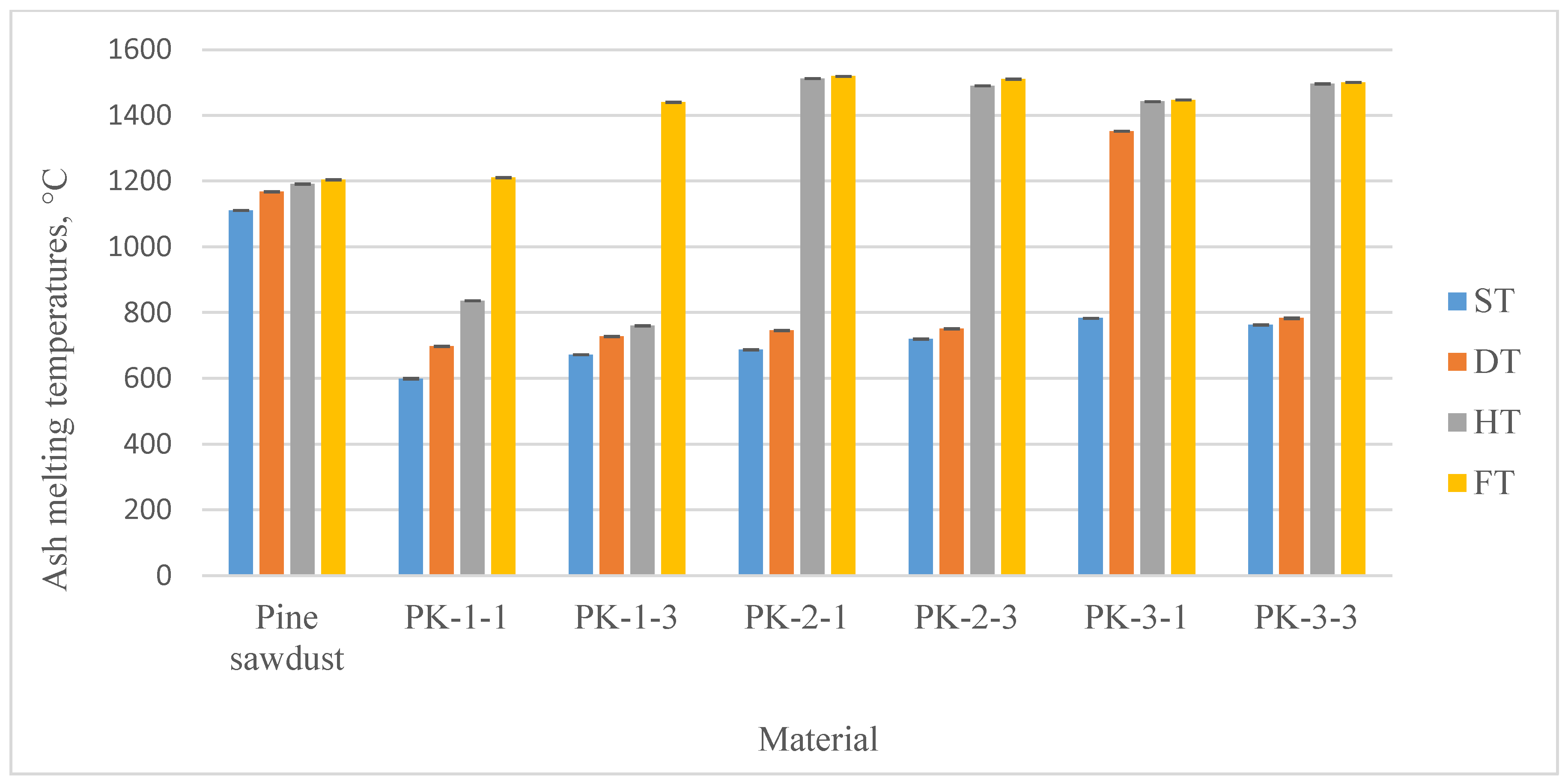

- initial point of deformation (IT) when the sharp peak is rounded;

- softening temperature (ST), when the ash cone deforms and its height decreases to the size of its diameter;

- hemisphere temperature (HT), when the sample assumes a hemispherical shape;

- melting point (FT), at which the ash melts and liquefies.

3. Results and Discussion

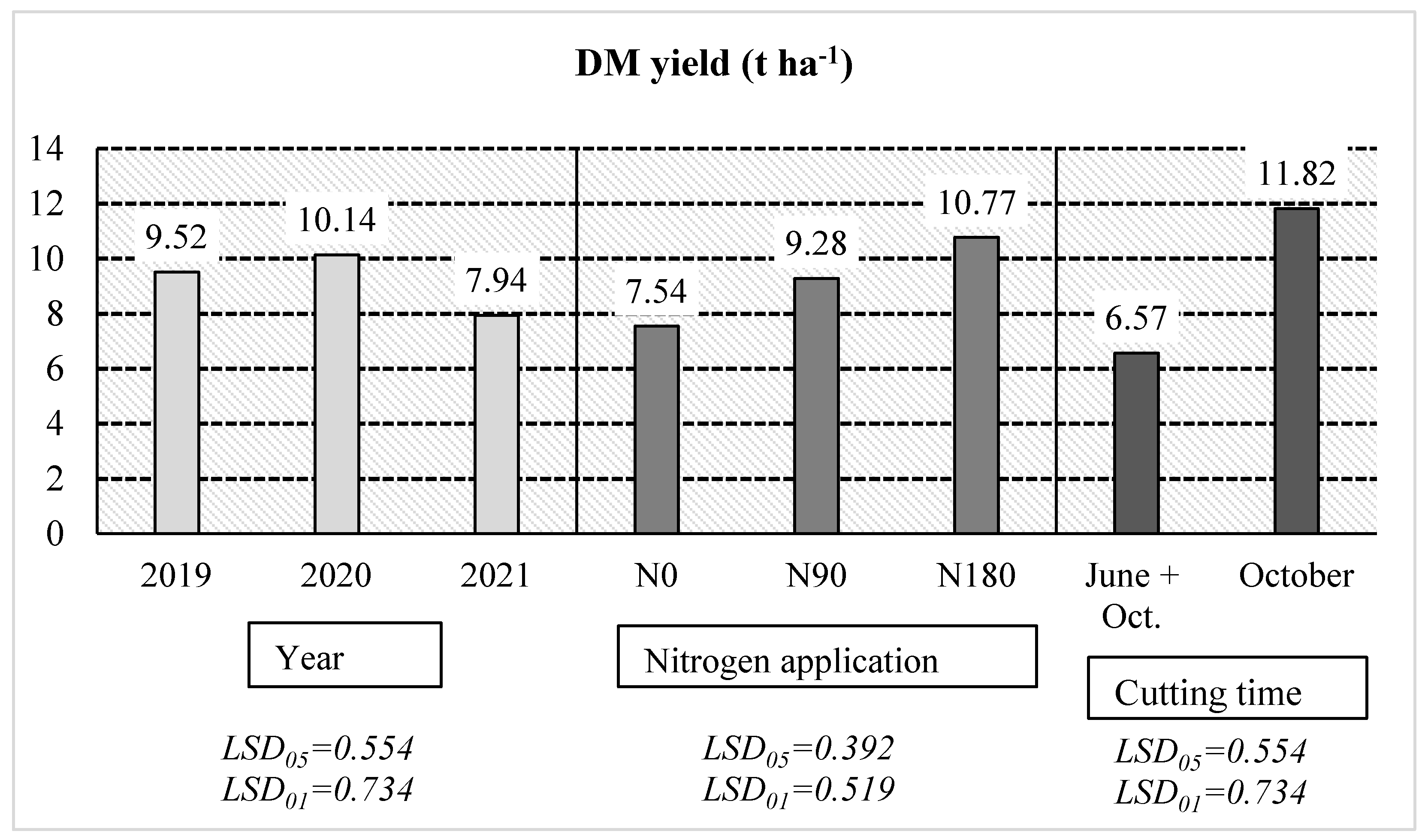

3.1. Artemisia dubia productivity and characteristics of samples

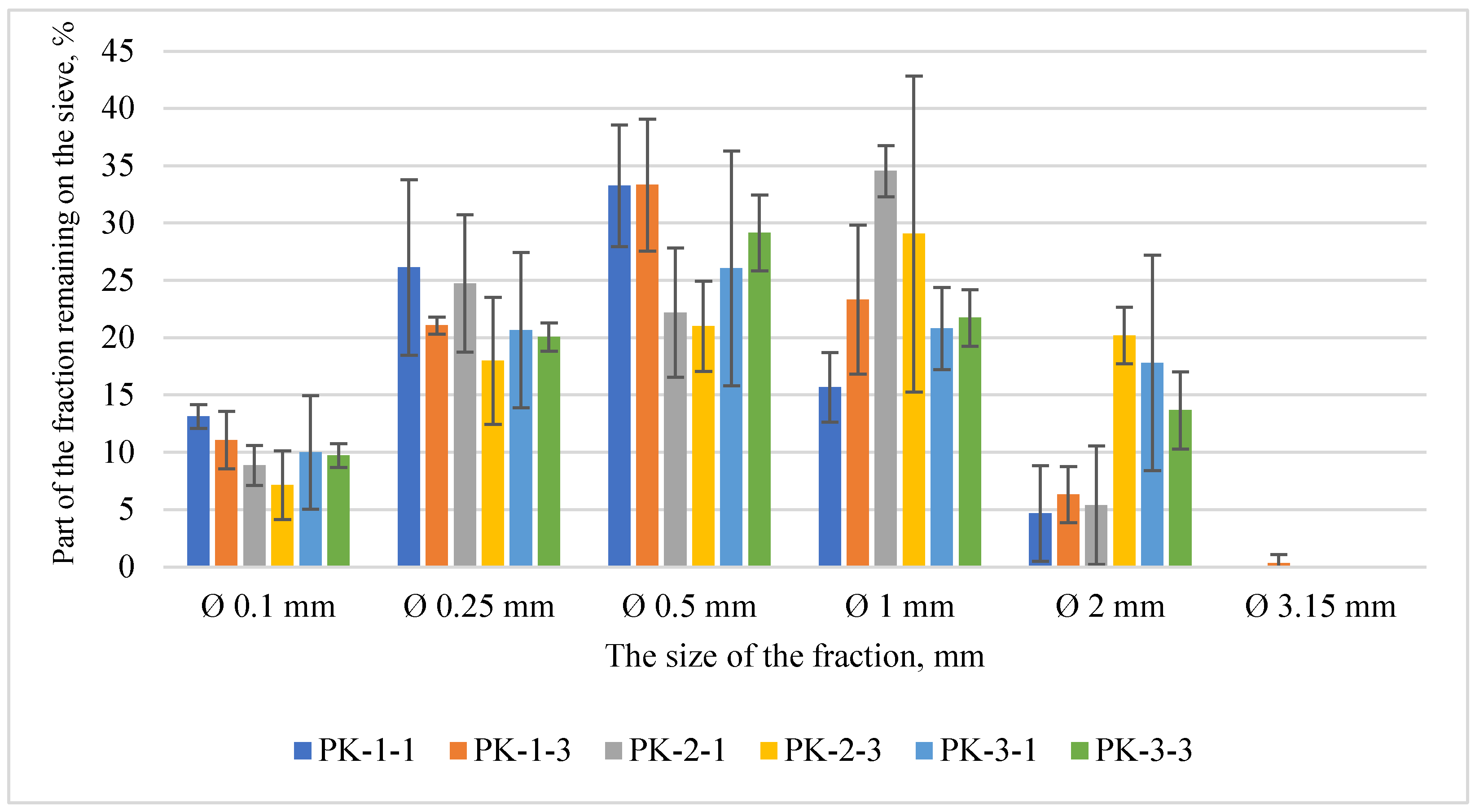

3.2. Determination of produced mill properties

3.3. Determination of pressed biofuel pellet properties

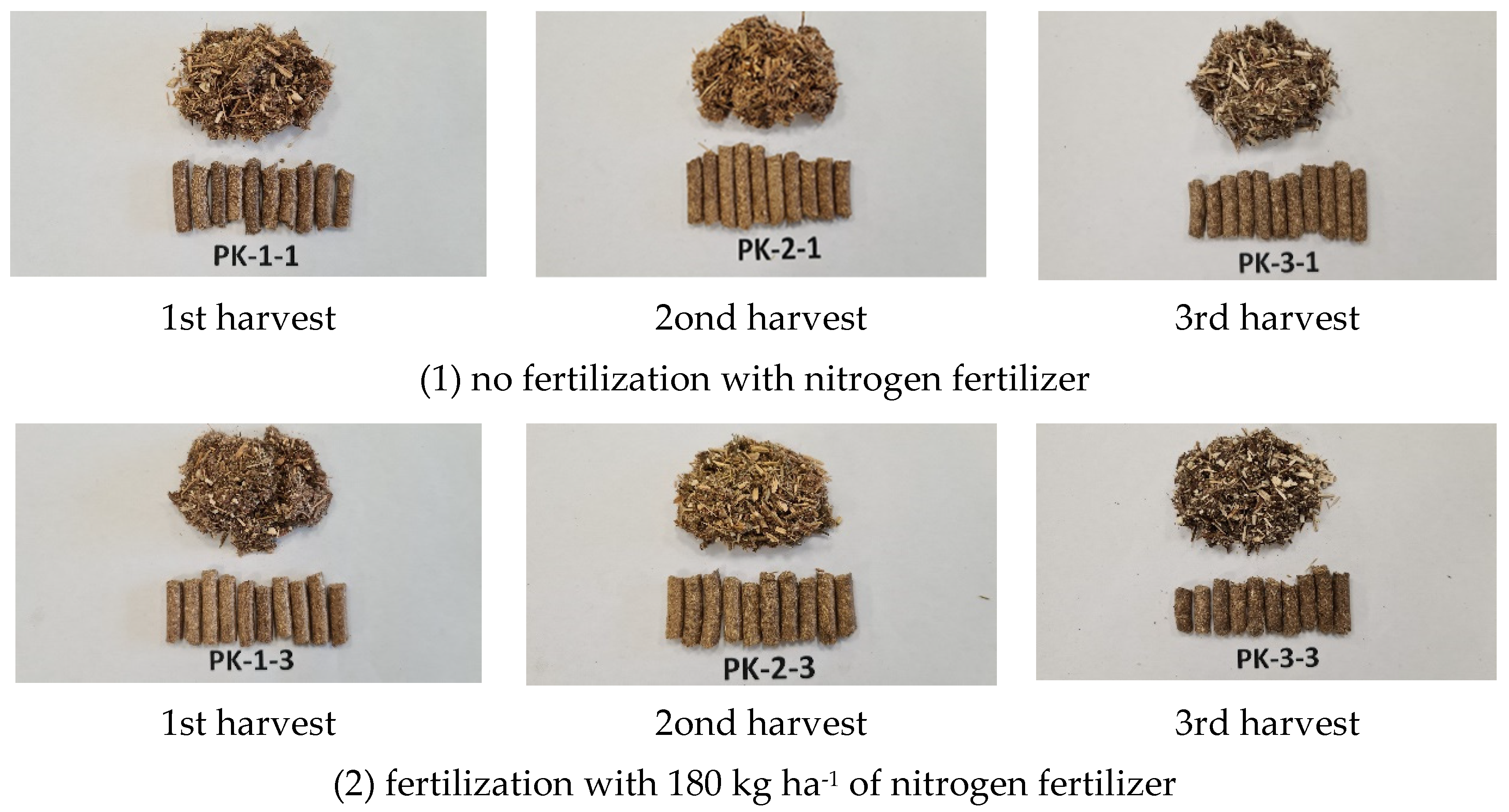

3.3.1. Pellet biometric properties

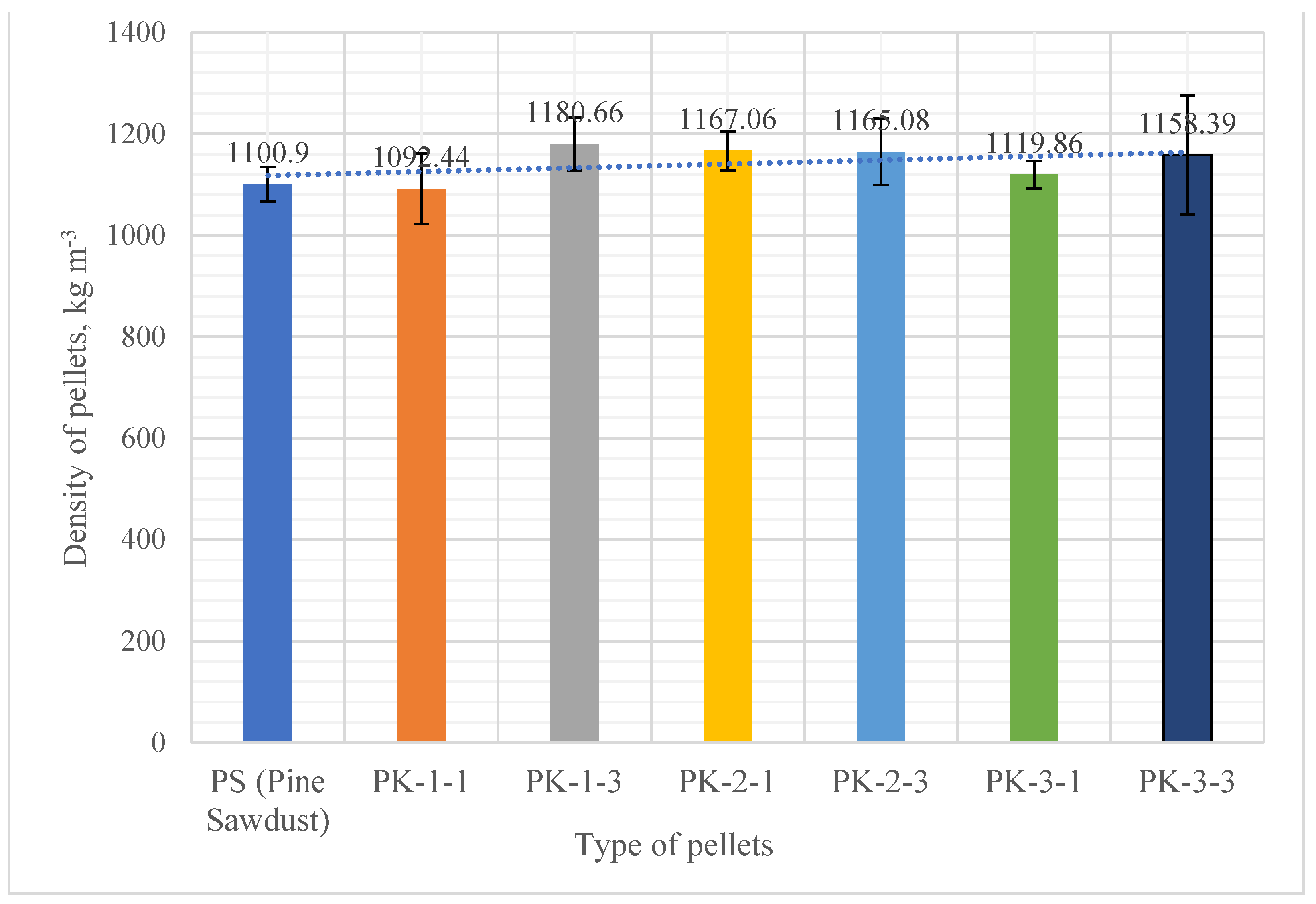

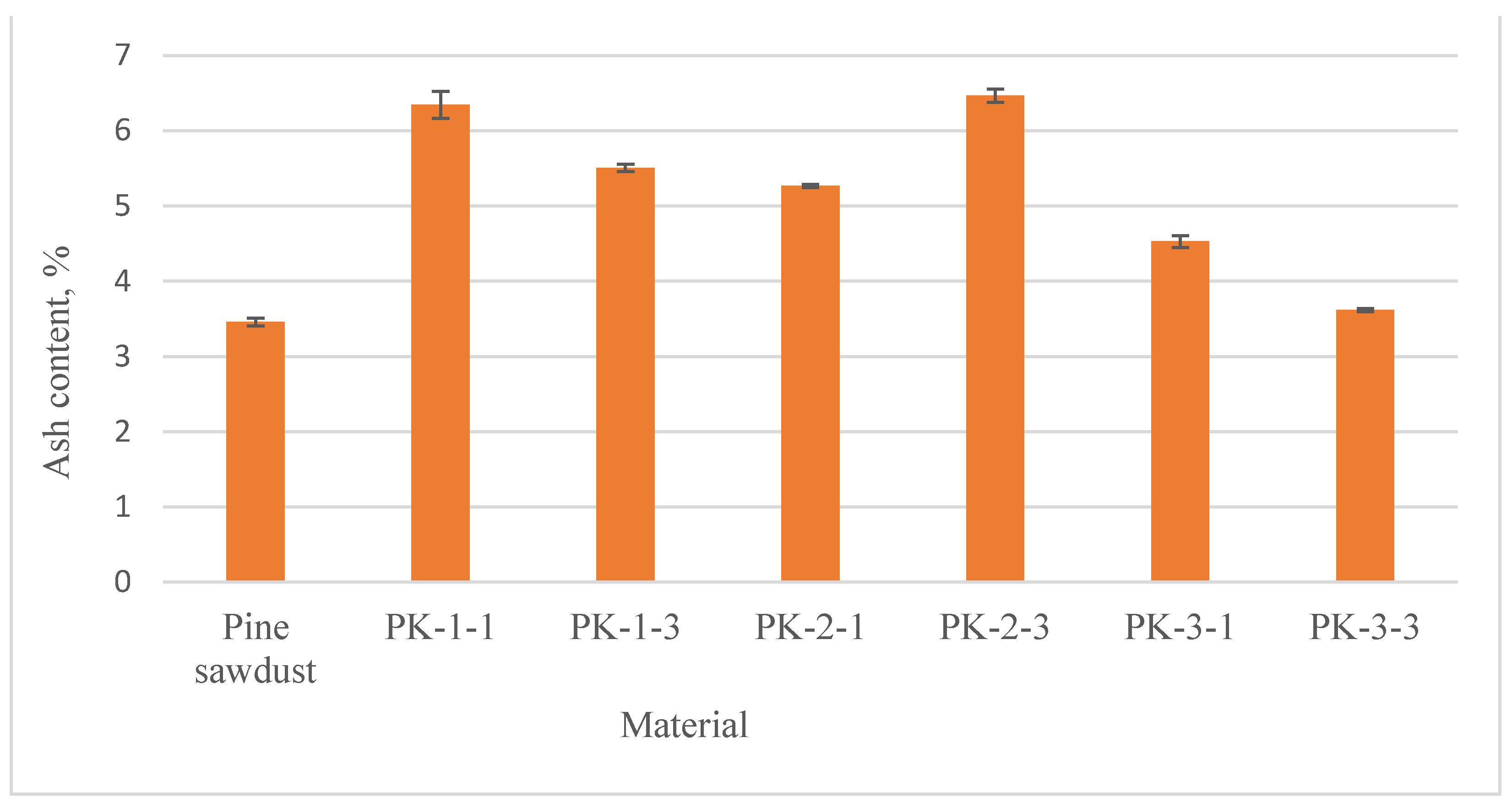

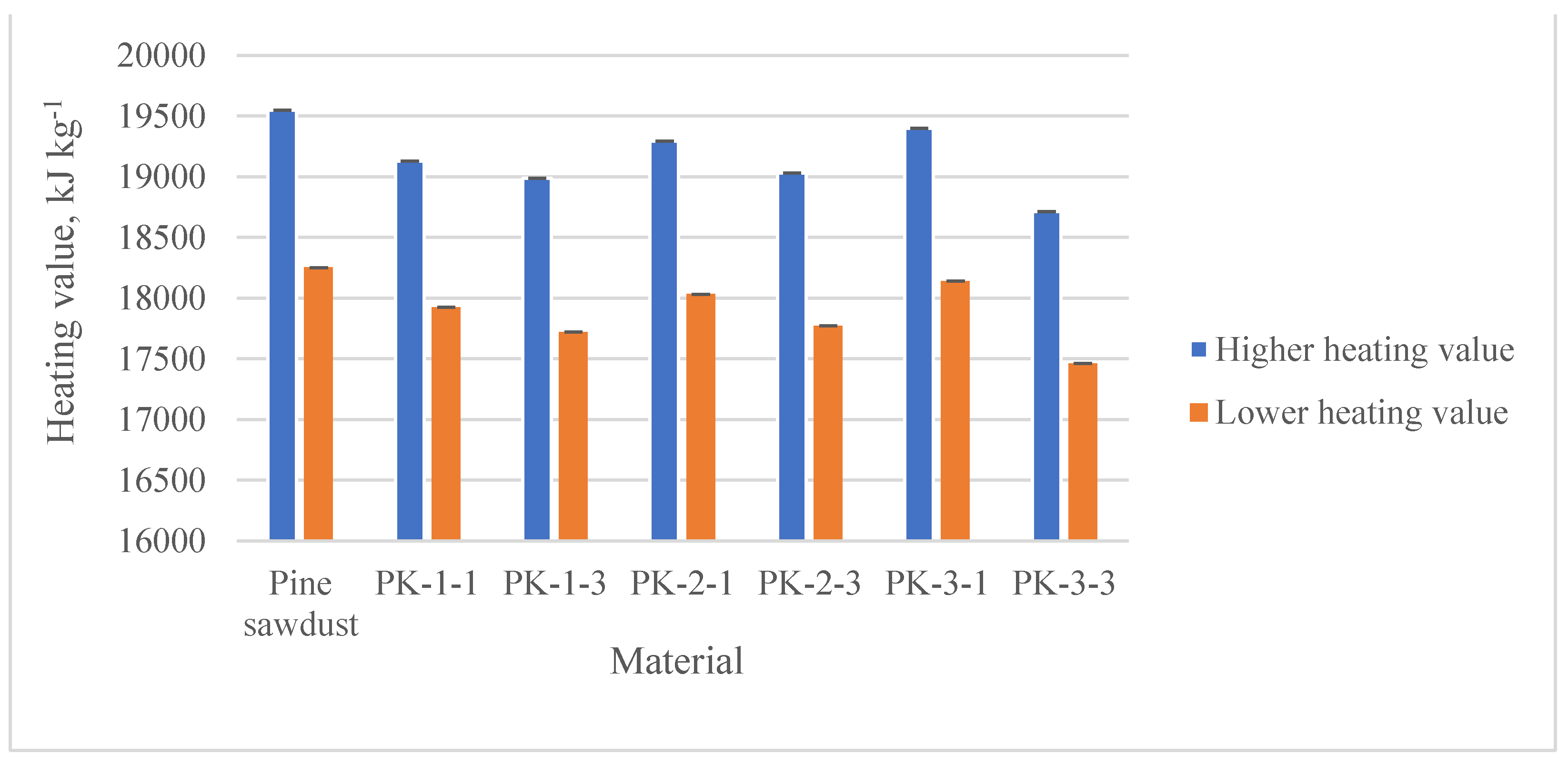

3.3.2. Pellet moisture content, density, ash content and heating value

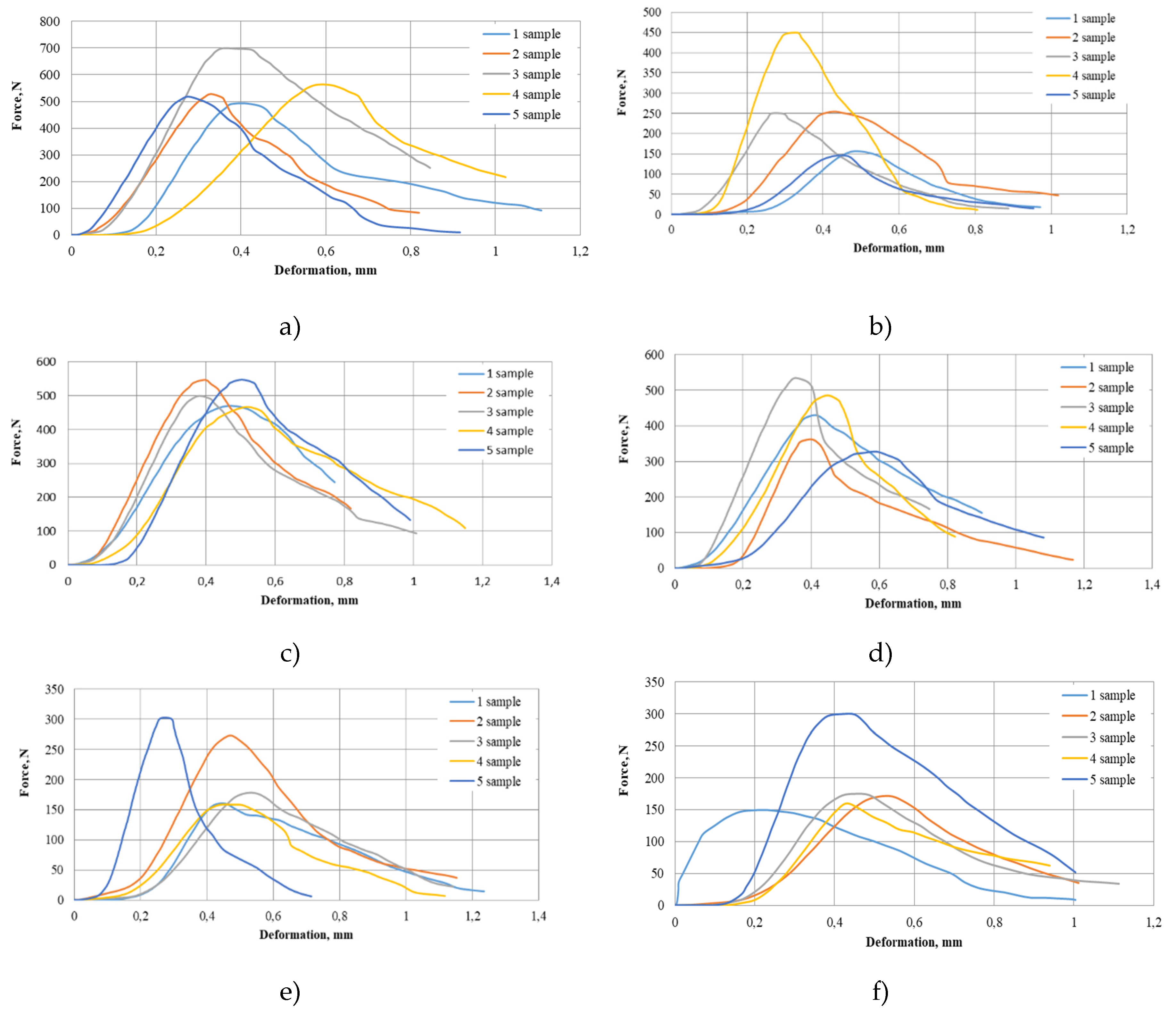

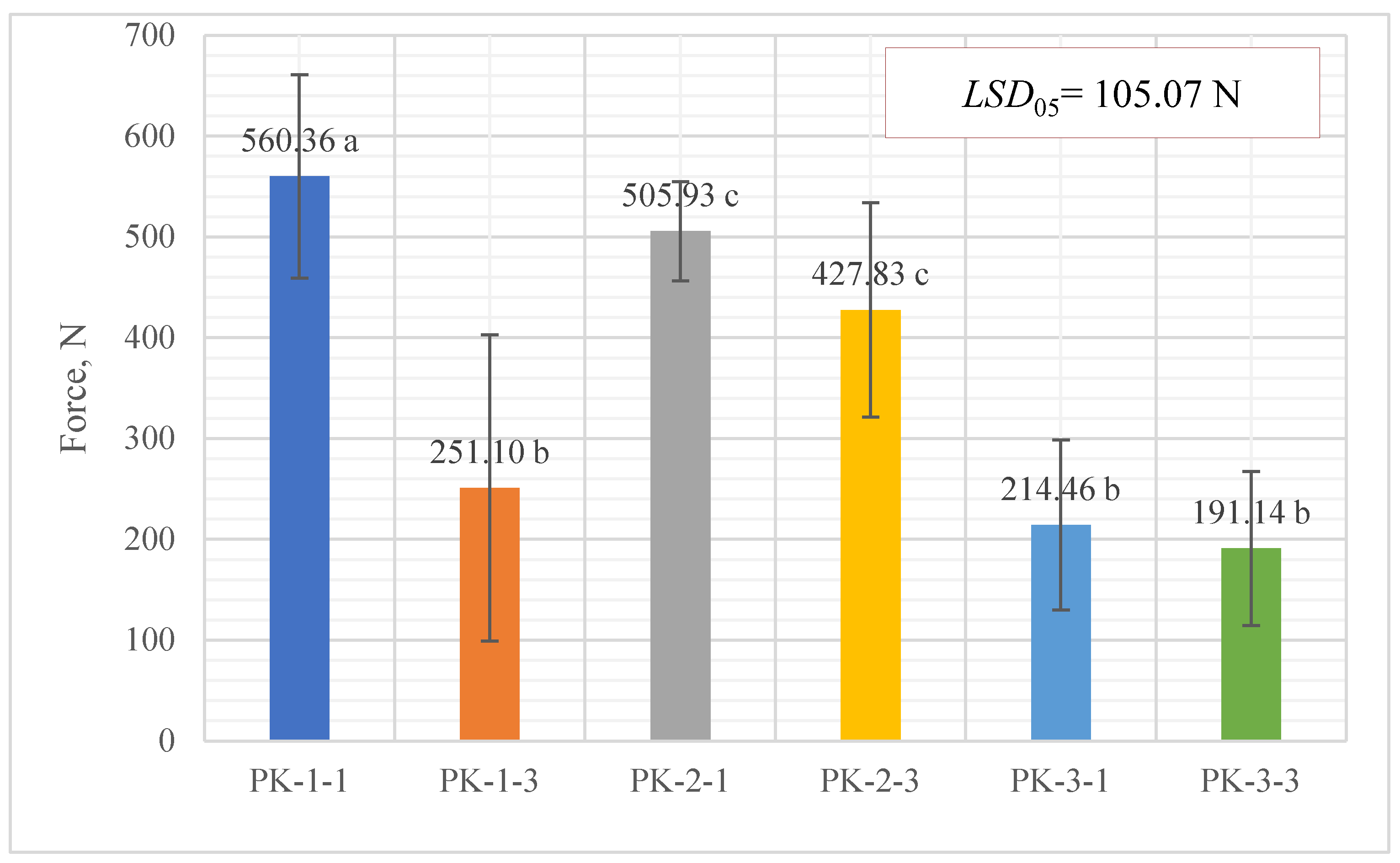

3.3.3. Evaluation of Artemisia dubia plant pellet strength and resistance to compression

3.3.4. Pellet elemental composition and ash melting temperatures

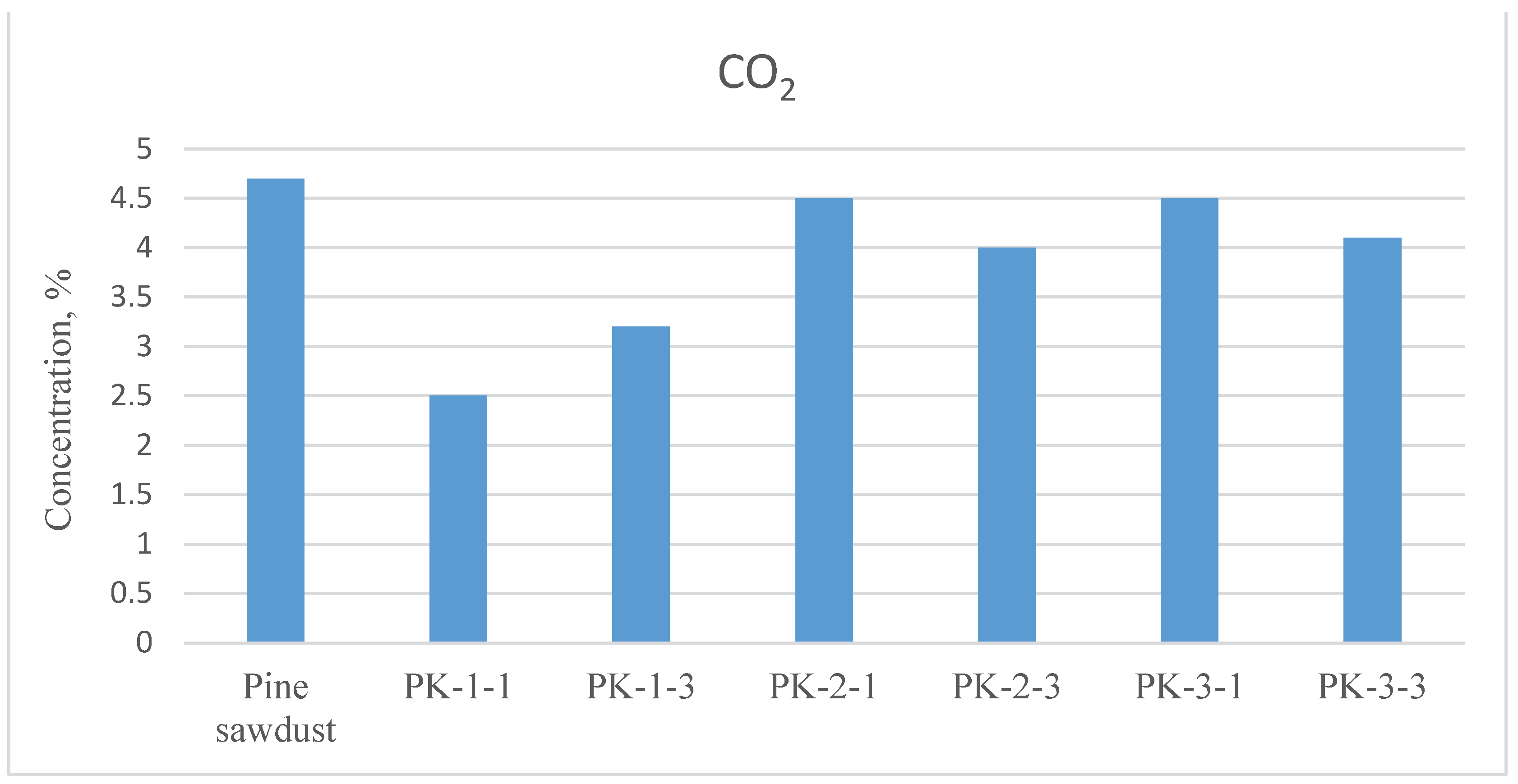

3.3.5. Determination of harmful emissions from the combustion of produced pellet

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission COM. Green paper: A 2030 framework for climate and energy policies. Brussels 2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2013:0169:FIN:en:PDF (accessed on 20 01 2024).

- De Laporte, A.V.; Weersink, A.J.; McKenney, D.W. Effects of supply chain structure and biomass prices on bioenergy feedstock supply. Applied Energy 2016, 183, 1053–1064. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Alvarez, P.; Pizarro, C.; Barrio-Anta, M.; Camara-Obregon, A.; Bueno, J.M.L.; Alvarez, A.; Gutierrez, I.; Burslem, D.F. Evaluation of tree species for biomass energy production in northwest Spain. Forests 2018, 9(4), 160. [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, X. Better use of bioenergy: A critical review of co-pelletizing for biofuel manufacturing. Carbon Capture Science & Technology 2021, 1, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Jasinskas, A.; Minajeva, A.; Šarauskis, E.; Romaneckas, K.; Kimbirauskienė, R.; Pedišius, N. Recycling and utilisation of faba bean harvesting and threshing waste for bioenergy. Renewable energy 2020, 162, 257–266. [CrossRef]

- Barmina, I.; Lickrastina, A.; Zake, M.; Arshanitsa, A.; Solodovnik, V.; Telisheva, G. Effect of main characteristics of pelletized renewable energy resources on combustion characteristics and heat energy production. Chemical Engineering 2012, 29, 901–906. [CrossRef]

- Hui, Y. Comparison of woody pellets, straw pellets, and delayed harvest system herbaceous biomass (switchgrass and miscanthus): analysis of current combustion techniques determining the value of biomass. 2011. Available online: http://edepot.wur.nl/192415 (accessed on 18 01 2024).

- Ciesielczuk, T.; Poluszyńska, J.; Rosik-Dulewska, C.; Sporek, M.; Lenkiewicz, M. Uses of weeds as an economical alternative to processed wood biomass and fossil fuels. Ecological Engineering 2016, 95, 485–491. [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, M. J.; Warmiński, K.; Krzyżaniak, M.; Olba–Zięty, E. Cascaded use of perennial industrial crop biomass: The effect of biomass type and pretreatment method on pellet properties. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 185, 115104. [CrossRef]

- Černiauskienė, Ž.; Raila, A. J.; Zvicevičius, E.; Kadžiulienė, Ž.; Tilvikienė, V. Analysis of Artemisia dubia Wall. growth, preparation for biofuel and thermal conversion properties. Renewable Energy 2018, 118, 468–476. [CrossRef]

- Černiauskienė, Ž.; Raila, A. J.; Zvicevičius, E.; Tilvikienė, V.; Jankauskienė, Z. Comparative Research of Thermochemical Conversion Properties of Coarse-Energy Crops. Energies 2021, 14(19), 6380. [CrossRef]

- Tilvikiene, V.; Kadžiulienė, Z.; Liaudanskienė, I.; Zvicevičius, E.; Černiauskienė, Z.; Čipliene, A.; Raila, A.J., Baltrušaitis, J. The quality and energy potential of introduced energy crops in northern part of temperate climate zone. Renewable Energy 2020, 151, 887–895. [CrossRef]

- Rancane, S.; Makovskis, K.; Lazdina, D.; Daugaviete, M.; Gutmane, I.; Berzins, P. Analysis of economical, social and environmental aspects of agroforestry systems of trees and perennial herbaceous plants. Agronomy Research 2014, 12(2), 589–602.

- San Miguel, G.; Sánchez, F.; Pérez, A.; Velasco, L. One-step torrefaction and densification of woody and herbaceous biomass feedstocks. Renewable Energy 2022, 195, 825–840. [CrossRef]

- Neacsu, A.; Gheorghe, D. Characterization of biomass renewable energy resources from some perennial species. Revue Roumaine de Chimie 2021, 66(4), 321–329.

- Yılmaz, H.; Çanakcı, M.; Topakcı, M.; Karayel, D.; Yiğit, M.; Ortaçeşme, D. In-situ pelletization of campus biomass residues: Case study for Akdeniz University. Renewable Energy 2023, 212, 972–983. [CrossRef]

- Forbes, E. G. A.; Easson, D. L.; Lyons, G. A.; McRoberts, W. C. Physico-chemical characteristics of eight different biomass fuels and comparison of combustion and emission results in a small scale multi-fuel boiler. Energy conversion and management 2014. 87, 1162–1169. [CrossRef]

- Jablonowski, N. D.; Kollmann, T.; Meiller, M.; Dohrn, M.; Müller, M.; Nabel, M.; … Schrey, S. D. Full assessment of Sida (Sida hermaphrodita) biomass as a solid fuel. GCB Bioenergy 2020, 12(8), 618–635. [CrossRef]

- Mallik, B. B. D.; Acharya, B. D.; Saquib, M.; Chettri, M. K. Allelopathic effect of Artemisia dubia extracts on seed germination and seedling growth of some weeds and winter crops. Ecoprint: An International Journal of Ecology 2014, 21, 23–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.3126/eco.v21i0.11901.

- Ashraf, M.; Hayat, M. Q.; Mumtaz, A. S. A study on elemental contents of medicinally important species of Artemisia L. (Asteraceae) found in Pakistan. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 2010, 4(21), 2256–2263.

- Kryževičienė, A.; Šarūnaitė, L.; Stukonis, V.; Dabkevičius, Z.; Kadžiulienė, Ž. Assessment of perennial mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris L. and Artemisia dubia Wall.) potential for biofuel production. Agricultural Sciences 2010, 17, 1-2.

- Tilvikiene, V.; Kadziuliene, Z.; Raila, A.; Zvicevicius, E.; Liaudanskiene, I.; Volkaviciute, Z.; Pociene, L. Artemisia dubia Wall. – A Novel Energy Crop for Temperate Climate Zone in Europe. In Proceedings of the 23rd European Biomass Conference and Exhibition, Vienna, Austria, 1–4 June 2015.

- Kadžiulienė, Ž.; Tilvikienė, V.; Liaudanskienė, I.; Pocienė, L.; Černiauskienė, Ž.; Zvicevicius, E.; Raila, A. Artemisia dubia growth, yield and biomass characteristics for combustion. Zemdirbyste-Agriculture 2017, 104(2), 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Šiaudinis, G.; Jasinskas, A.; Karčauskienė, D.; Skuodienė, R.; Repšienė, R. The impact of nitrogen on the yield formation of Artemisia dubia Wall.: efficiency and assessment of energy parameters. Plants 2023, 12 (13), 2441. [CrossRef]

- World Reference Base (WRB) for Soil Resources, World Soil Resources Reports No. 106. FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014, 187–189. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3794en/I3794en.pdf (accessed on 16 01 2024).

- Jasinskas, A.; Streikus, D.; Vonžodas, T. Fibrous hemp (Felina 32, USO 31, Finola) and fibrous nettle processing and usage of pressed biofuel for energy purposes. Renewable energy 2020, 149, 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Minajeva, A.; Jasinskas, A.; Domeika, R.; Vaiciukevičius, E.; Lemanas, E.; Bielski, S. The Study of the faba bean waste and potato peels recycling for pellet production and usage for energy conversion. Energies 2021, 14 (10), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- ISO 17829. Solid Biofuels. Determination of Length and Diameter of Pellets; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO 18134. Solid Biofuels—Determination of Moisture Content; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Streikus, D. Assessment of technologies for processing and usage of coarse-stem and fibrous plants for energy purposes. Summary of PhD Thesis, Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas, Lithuania, Kaunas, 2020.

- LST CEN/TS 15370-1. Solid Biofuels - Methods for the Determination of Ash Melting Temperatures - Part 1; CEN/TS: Department of Standardization, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2007.

- Vareas, V.; Kask U.; Muiste P.; Pihu T.; Soosaar S. Biofuel user manual. Zara: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2007. 168 p. (in Lithuanian). Available online: https://www.ena.lt/uploads/PDF-AEI/Leidiniai-LT/4-Biokuro-zinynas.pdf (accessed on 16 01 2024).

- LAND 43-2013. Norms for Combustion Plants Emissions. Department of Standardization: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2013.

- Raudonius, S. Application of statistics in plant and crop research: Important issues. Zemdirbyste 2017, 104, 377–382.

- Ungureanu, N.; Vladut, V.; Voicu, G.; Dinca, M.N.; Zabava, B.S. Influence of biomass moisture content on pellet properties–Review. Engineering for rural development 2018, 17, 1876–1883.

- Greinert, A.; Mrówczyńska, M.; Grech, R.; Szefner, W. The Use of Plant Biomass Pellets for Energy Production by Combustion in Dedicated Furnaces. Energies 2020, 13(2), 463. [CrossRef]

- Maj, G.; Krzaczek, P.; Gołębiowski, W.; Słowik, T.; Szyszlak-Bargłowicz, J.; Zając, G. Energy Consumption and Quality of Pellets Made of Waste from Corn Grain Drying Process. Sustainability 2022, 14(13), 8129. [CrossRef]

- Tumuluru, J.S. Effect of pellet die diameter on density and durability of pellets made from high moisture woody and herbaceous biomass. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2018, 1, 44–54. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, H.H.; Ayhan, B.; Turgut, K. An assessment of the energetic properties of fuel pellets made by agricultural wastes. Scientific Papers. Series E. Land Reclamation, Earth Observation and Surveying, Environmental Engineering 2019, 8, 9–16.

- ISO 17225-6. Solid biofuels — Fuel specifications and classes — Part 6: Graded non-woody pellets, Department of Standardization, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2021.

- Rajput, S.P.; Jadhav, S.V.; Thorat, B.N. Methods to improve properties of fuel pellets obtained from different biomass sources: Effect of biomass blends and binders. Fuel Processing Technology 2020, 199, 106255. [CrossRef]

- Matin, B.; Leto, J.; Antonovi´c, A.; Brandi´c, I.; Juriši´c, V.; Matin, A.; Kriˇcka, T.; Grubor, M.; Kontek, M.; Bilandžija, N. Energetic Properties and Biomass Productivity of Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) under Agroecological Conditions in Northwestern Croatia. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1161. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Mlonka-Mędrala, A.; Lenz, V.; Nelles M. Evaluation of bottom ash slagging risk during combustion of herbaceous and woody biomass fuels in a small-scale boiler by principal component analysis. Biomass Convers Biorefinery 2019, 11, 1211–1229. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | PK-1-1 | PK-1-3 | PK-2-1 | PK-2-3 | PK-3-1 | PK-3-3 | Pine sawdust (PS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length, mm |

25.77 | 25.33 | 25.79 | 23.97 | 24.66 | 21.82 | 30.73 ± 0.88 |

| Diameter, mm | 6.22 | 6.32 | 6.39 | 6.32 | 6.25 | 6.31 | 6.09 ± 0.13 |

| Mass, g |

0.93 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.91 ± 0.05 |

| Density, kg m-3 |

1192.44 ±69.72 |

1180.66 ±52.25 |

1167.06 ±38.11 |

1165.08 ±65.87 |

1119.86 ±26.65 |

1158.39 ±117.84 |

1100.90 ±34.00 |

| Moisture content, % |

9.98 ± 0.33 | 8.85 ± 0.61 | 9.26 ± 0.37 | 8.80 ± 0.55 | 9.66 ± 0.55 | 10.49 ± 0.40 | 7.50 ± 0.55 |

| Ash content, % |

6.35 ± 0.18 | 5.51 ± 0.05 | 5.27 ± 0.02 | 6.47 ± 0.09 | 4.53 ± 0.08 | 3.62 ± 0.02 | 3.46 ± 0.05 |

| LHV, MJ kg-1 |

17.92 ± 1.01 | 17.72 ± 0.30 | 18.03 ± 0.05 | 17.77 ± 0.30 | 18.14 ± 0.28 | 17462 ± 0.25 | 18.25 ± 0.59 |

| Parameter | PK-1-1 | PK-1-3 | PK-2-1 | PK-2-3 | PK-3-1 | PK-3-3 | Pine sawdust (PS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemisia dubia plant pellets elemental composition, % | |||||||

| C, % | 48.67 ± 0.20 | 47.34 ± 0.12 | 48.33 ± 0.09 | 47.52 ± 0.10 | 48.73 ± 0.11 | 49.36 ± 0.01 | 49.87 ± 0.11 |

| N, % | 1.22 ± 0.09 | 1.41 ± 0.13 | 1.00 ± 0.03 | 1.51 ± 0.01 | 0.68 ± 0.02 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.47 ± 0.01 |

| H, % | 5.51 ± 0.01 | 5.79 ± 0.06 | 5.76 ± 0.09 | 5.75 ± 0.02 | 5.76 ± 0.02 | 5.73 ± 0.05 | 5.94 ± 0.03 |

| S, % | 0.07 ± 4.91 | 0.07 ± 8.77 | 0.06 ± 2.78 | 0.06 ± 11.49 | 0.05 ± 2.34 | 0.06 ± 5.49 | 0.06 ± 2.28 |

| O, % | 37.8 | 39.6 | 39.4 | 38.4 | 39.9 | 40.0 | 40.1 |

| Cl, % | 0.37 ± 9.81 | 0.30 ± 5.86 | 0.20 ± 10.04 | 0.25 ± 8.77 | 0.37 ± 9.81 | 0.38 ± 8.77 | 0.07 ± 1.31 |

| Artemisia dubia plant pellets ash melting temperatures, °C | |||||||

| ST, °C | 599 ± 1.56 | 672 ± 0.42 | 687 ± 0.62 | 720 ± 0.79 | 783 ± 0.54 | 763 ± 0.93 | 1111 ± 0.38 |

| DT, °C | 698 ± 0.81 | 728 ± 0.78 | 746 ± 0.76 | 751 ± 0.19 | 1352 ± 0.63 | 783 ± 0.90 | 1168 ± 0.48 |

| HT, °C | 836 ± 0.32 | 760 ± 0.37 | 1512 ± 0.19 | 1490 ± 0.19 | 1442 ± 0.39 | 1496 ± 0.87 | 1191 ± 0.59 |

| FT, °C | 1211 ± 0.58 | 1440 ± 0.39 | 1519 ± 0.28 | 1510 ± 0.37 | 1447 ± 0.29 | 1500 ± 0.19 | 1204 ± 0.47 |

| Independent variables, x |

Depended variables, Y | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C, % | O, % | H, % | N, % | S, % | Cl, % | |

| C, % | 1.000 | 0.433 | n | -0.880** | -0.334 | n |

| O, % | - | 1.000 | 0.775* | -0.676 | -0.498 | n |

| H, % | - | - | 1.000 | -0.479 | -0.398 | -0.724 |

| N, % | - | - | - | 1.000 | 0.587 | 0.330 |

| S, % | - | - | - | - | 1.000 | n |

| Independed variable x | Depended variables, Y | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humidity, % |

Density, kg m-3 |

Ash content, % | LHV, MJ kg-1 |

ST, °C |

DT, °C |

HT, °C |

FT, °C |

|

| C, % | n | -0.635 | -0.792* | 0.393 | 0.667 | 0.499 | n | -0.502 |

| O, % | n | -0.682 | -0.883** | 0.344 | 0.618 | 0.564 | 0.305 | n |

| H, % | -0.739 | -0.744 | -0.621 | n | 0.807* | 0.496 | n | n |

| N, % | n | 0.848* | 0.853* | n | -0.759* | -0.784* | -0.301 | 0.347 |

| S, % | n | 0.723 | 0.459 | n | -0.400 | -0.758* | -0.809* | -0.351 |

| Cl,% | 0.901** | 0.496 | n | 0.398 | -0.711 | n | n | n |

| Plant species | CO2 | CO | NOx | CxHy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ppm | ppm | ppm | |

| PK-1-1 | 2.5 | 8303 | 157 | 1109 |

| PK-1-3 | 3.2 | 3219 | 150 | 307 |

| PK-2-1 | 4.5 | 2447 | 169 | 206 |

| PK-2-3 | 4.0 | 4121 | 206 | 495 |

| PK-3-1 | 4.5 | 702 | 111 | 40 |

| PK-3-3 | 4.1 | 2555 | 141 | 287 |

| Pine sawdust | 4.7 | 188 | 111 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).