1. Introduction

Agro-industrial activity generates large quantities of effluents and organic waste that can generate negative impacts to the environment [1; 2]. In particular, wine industry is an attractive productive activity that allows the valorization of arid ecoregions with some existing production limitations. In Argentina, viticulture is an important economic activity, reaching 204,847 ha. cultivated in 2023 [

3]. In this sense, one of the main factors limiting production is the scarcity of water resources [

3]. Viticulture generates large quantities of grape marc, wine-production sediments and stalks, among others. However, in a clear alignment with the principles of circular bioeconomy, these organic residues have the potential to be valorized by other industries that produce other value-added products, such as food grade alcohol, tartaric acid, grape seed oil and compost [4; 5; 6]. Although this approach contributes to the principles of the circular bioeconomy, it is evident that such production also generates high volumes of effluents with high organic load and salt content, with water resources being the most limiting factor for their production in arid regions [

7].

Although there are antecedents of the use of viticultural biomass for adding-value strategies, there is a lack of studies that evaluate the possible use of these effluents to valorize them and thus reducing their impact on the environment. The use of agro-industrial effluents could be a strategy to cultivate plant biomass in arid areas to be valorized as bioenergy sources, animal feed or as a co-substrate in the composting process. In this sense, the aim of this study was to evaluate alternatives for the use of these industrial effluents with high electrical conductivity in productive agro-ecosystems for the generation of vegetal biomass for energy, animal feed or raw materials for composting and further applications. All the experiments presented in this study have used real effluents and full scale reproducible tests.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Starting Materials

DERVINSA company is located at Palmira, San Martin Deparment (Mendoza Province, Argentina). DERVINSA is a company that receives 80% of the vinification organic waste generated in Argentina such as: grape marc (120,000-140,000 Tn/year), vinification sediment (40,000 Tn/year) and 20,000 Tn/year of other tartaric raw materials. From these wine production waste, this company produces tartaric acid (4,000 Tn/year), grape oil (3,000 Tn/year), food quality alcohol (3,000 Tn/year) and compost (12,000 Tn/year).

This production process generates two types of effluents: i) effluent from the processing of grape marc (EGM, generation: 25 m

3/h) and, ii) vinasse, from the processing of wine lees (V, generation: 25 m

3/h). Both effluent streams are characterised by high electrical conductivity (EC) and slightly acidic pH (

Table 1).

2.2. Exploratory Preliminary Study

An exploratory plant growth assay of the three selected forage species was conducted to evaluate the effect of dilutions of the different effluent streams on small scale experiments.

First, an initial mixture of EGM and V effluents was made in a 1:1 (v:v) ratio. Four dilutions (%, in volume) were used from this mixture: i) Control (water, 0% mixture), ii) Dilution 1 (9% mixture), iii) Dilution 2 (15% mixture) and iv) Dilution 3 (24% mixture).

Different forage species were planted: i) sorghum (Sorghum × drummondii) and ii) mixed perennial pasture composed of sweet clover (Melilotus officinalis) and wheatgrass (Thinopyrum ponticum). This resulted in 8 treatments that were evaluated in triplicate: i) Pasture-control, ii) Pasture-dilution 1, iii) Pasture-dilution 2, iv) Pasture-dilution 3, v) Sorghum-control, vi) Sorghum-dilution 1, vii) Sorghum-dilution 2 and viii) Sorghum-dilution 3.

The seeds were sown in 20 L containers with a seeding density equivalent to 16, 30 and 60 Kg/ha, for sweet clover, wheatgrass and sorghum, respectively. The substrate used was the topsoil (typical torrifluent entisol) from the demonstration/experimental site of the company's property [

8]. It was manually homogenized prior to filling the cultivation containers.

Irrigation was carried out with a frequency of 5 days with the previously described solutions, applying a total volume of 23 L per container during the crop cycle for mixed pastures and 32 L for sorghum.

This exploratory study was carried out under greenhouse conditions and lasted 43 days (temperature range: 11-28 °C, humidity range: 40-60%). At the end of the assay, the plants were harvested and the fresh and dry weight of each pot was quantified.

2.3. Experimental Design of Field Assay

A plot assay with the previously-selected dilution 1 (9%) was carried out in a plot located at the Dervinsa company (-33.040623, -68.563479). The study site is characterised by a semi-arid climate, typical of the Cuyo region (Argentina). Summer is hot and dry, with maximum temperatures that can exceed 35°C, while winter is cold and more humid, with minimum temperatures that sometimes fall below 0°C. Rainfall is low throughout the year, and it is mainly concentrated in the summer months, with an annual average of around 200-300 mm. This climate favours agricultural activities, especially viticulture and fruit production, which are characteristic of the area [

3].

The soil where the plot assay was carried out belongs to the typical torrifluent entisol class [

8]. The organoleptic texture of the first horizon (0-0.40 m) was sandy, then a very compacted sandy layer (0.40 - 1.00 m) and sandy with black specks (1-1.5 m). The apparent density in the upper layer was less than 1 (0.91 g/cm

3) and that of the subsurface layer was higher (1.40 g/cm

3).

According to the elemental textural analysis, a very low clay content is detected, less than 1 % in the first 0.40 m and American silt content (2 to 50 µm) at 26 g%g and sand at 73 g%g, specifying the observed texture, sandy-frank and sandy (

Table 2).

Experimental plots were set up to evaluate the productivity of crops irrigated with the effluent mixture. Each experimental unit had an area of 1000 m2. Prior to sowing, the soil was tilled into 35 cm wide and 15 cm high ridges. A completely randomised experimental design with three replications was used, where the treatments were: i) Control (irrigated soil without crop), ii) perennial pasture (sweet clover and wheatgrass) and iii) Sorghum. According to the exploratory assay, a 9% dilution of the effluent mixture with irrigation water was selected. Sowing density was equivalent to 16, 30 and 60 kg/ha for sweet clover, wheatgrass and sorghum, respectively.

To calculate the water demand of the designed plots, the available effluent flow was analysed, the soil characteristics were evaluated, the replacement lamina was calculated, the water demand of the area and the demand of the crops. Subsequently, an irrigation schedule was designed using Winsrfr Software [

9] and the irrigation schedule was adjusted. During the plot experiments, it was necessary to arrange a new in situ adjustment of the schedule (especially in the initial stage of the crop, after sowing), as the actual demand of the plants was different from the theoretical one at the beginning of the experience, due to the depth explored by the roots of the crops (sown and/or transplanted). Thus, a total of 15 irrigations were finally used during the entire crop cycle, with an overall surface irrigation flow of 48.47 L/s for 3 hours each.

2.4. Analisys Methodology

2.4.1. Effluent Analisys

Composite samples were taken from the 9% diluted effluent. The parameters analysed to characterise the effluent were: pH, EC (dS/m), carbonates (CO₃²⁻), bicarbonates (HCO₃⁻), chloride (Cl-), sulphate (SO4-2), sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), calcium (Ca+2), magnesium (Mg) and sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) was determined as an indicator of risk of sodification or salinisation. All parameters were analysed by standardised methods described by APHA (2001) and INTA (2021) [10; 11].

2.4.2. Soil Analisys

Soil samples were taken in triplicate in the exploratory and the plot trial, at the beginning and at the end of the trials. The parameters analysed in soil samples were: pH, EC (dS/m), carbonates (meq/L), bicarbonates (meq/L), chloride (meq/L), sulphate (meq/L), sodium (Na), exchangeable potassium (Ext-K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), total nitrogen (TN), available phosphoruos (Available -P) and organic matter (OM). All parameters were analysed by standardised methods described by SAMLA (2004) [

12]. The soil texture was determined using the sedimentable volume (SV) method proposed by Nijenshon and Maffei (1996) [

13].

2.4.3. Vegetal Biomass Analisys

The aerial plant biomass generated in the exploratory study (duration: 43 days) and in the plot assay (duration: 99 days) was harvested at the end of the trials and its fresh and dry weight was determined.

A descriptive characterization of the nutrient content in plant biomass was performed. Subsamples were taken from each plot (1 kg dry matter) and subsequently, the material was homogenized and a composite sample was prepared for subsequent analysis (1 kg dry matter).The parameters analysed in the harvested aerial plant biomass from the plot assay were: EC (1:10, v:v), biomass weight, dry matter (DM), Ashes (%), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (PT), total potassium (TK), organic matter (OM) and total organic carbon and C:N ratio. All parameters were analysed by standardised methods [

12].

2.5. Statistical Analisys

ANOVA test coupled to LSD Fisher mean comparison test (p<0.05) was used to compare the different cultures. In order to corroborate ANOVA assumptions, Shapiro-Wilk normality tests and residues regression were also carried out. InfoStat software (version 2015) was used to perform all statistical analyses (InfoStat Group, FCA, National University of Córdoba, Argentina). All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Results

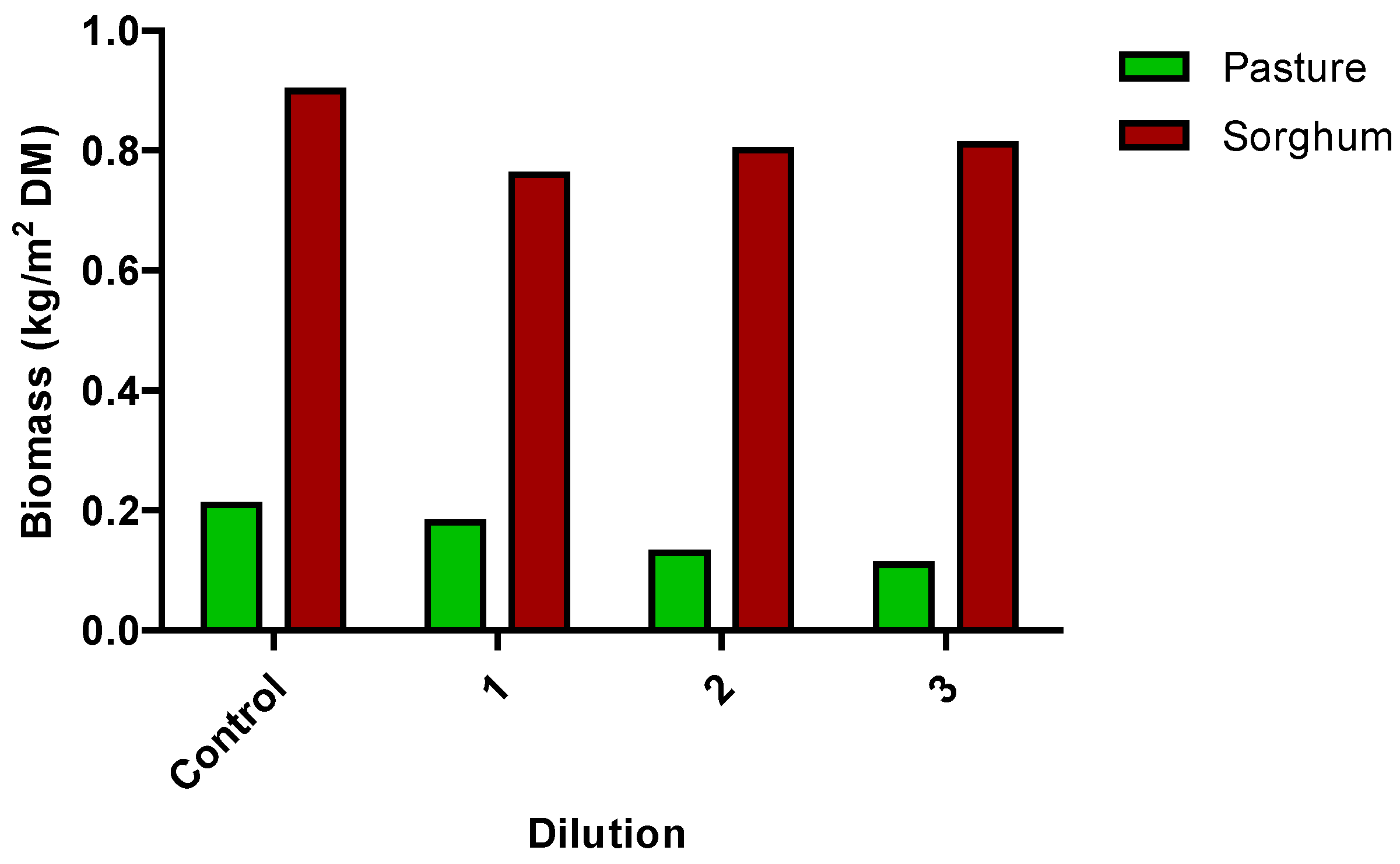

The harvested biomass results are shown in Fig. 1. These preliminary results allowed to identify that the most appropriate dilution of the effluent mixture was dilution 1 (9%) for both treatments. Therefore, the effluent mixture dilution of 9% was selected for the plot trial. It should be noted that in the sorghum treatments, 51% of the plant biomass belonged to other opportunistic plant species from to the local soil seed bank.

Figure 1.

Biomass harvested (pasture and sorghum) in the exploratory assay under greenhouse conditions.

Figure 1.

Biomass harvested (pasture and sorghum) in the exploratory assay under greenhouse conditions.

3.2. Characteristics of Effluent Used in the Demonstration Plot for Biomass Generation

The diluted effluent used as irrigation water showed a low suitability for agricultural use, according to the normal parameters of irrigation water characterization [

14]. However, the electrical conductivity of the effluent is lower than the soil conductivity. The electrical conductivity is above 0.75 dS/m, presenting a risk of chloride and potassium toxicity. Despite this fact, the value corresponds to high K and Ca contents (

Table 3). Regarding pH, the values were found to be close to the optimal range for wastewater use, according to the published main guidelines [

14].

3.3. Effects of Cultivation and Effluent Use on Soil Properties

It was verified that the soil texture presented a higher sedimentatble volume, which could be influenced by the high organic matter content compared to the initial levels (

Table 4, 5 and 6). This value was mainly observed in the sites where sorghum and pasture were cultivated, compared to the control soil (

Table 5).

In the case of the physico-chemical variables, the pH did not show differences between the cultivated soil and the control, with no differentiation at the depth of 0.00-0.30 m. However, the pH value at the depth of 0.30-0.60 m was significantly lower in the cultivated soil than in the control treatment. The electrical conductivity in the saturation extract was high, maintaining the classification of saline soil.Although there were no significant differences between the sowing treatments, the mean EC values obtained indicated that in the plots cultivated with pasture the value was lower, representing almost half that of the plots with sorghum and the control in the 0-30 cm layer (

p>0.05). The deeper layer showed lower values but is still being a saline soil. The soluble chloride content showed the same behavior, which requires special attention as it is a highly toxic element for crops. In the surface layer, 0-30 cm, the plot cultivated with pasture showed an average value close to 10 meq/L, while in the sorghum plot it was 2.5 times higher and in the control plot 5 times higher than in the pasture plot. This indicates that sorghum did not decrease the EC, but decreased the soluble chloride content in the saturated extract. Soluble potassium remains high, with higher contents than sodium. The rest of the physico-chemical parameters were similar between treatments (

p>0.05) and slightly higher at the beginning (

Table 4). The use of the effluent resulted in an increase in soil salinity and the crops planted allowed a partial reduction in soluble salt content, thus being the pasture more efficient in nutrients absorption than sorghum.

3.4. Biomass Generation from Mixed Grassland and Sorghum

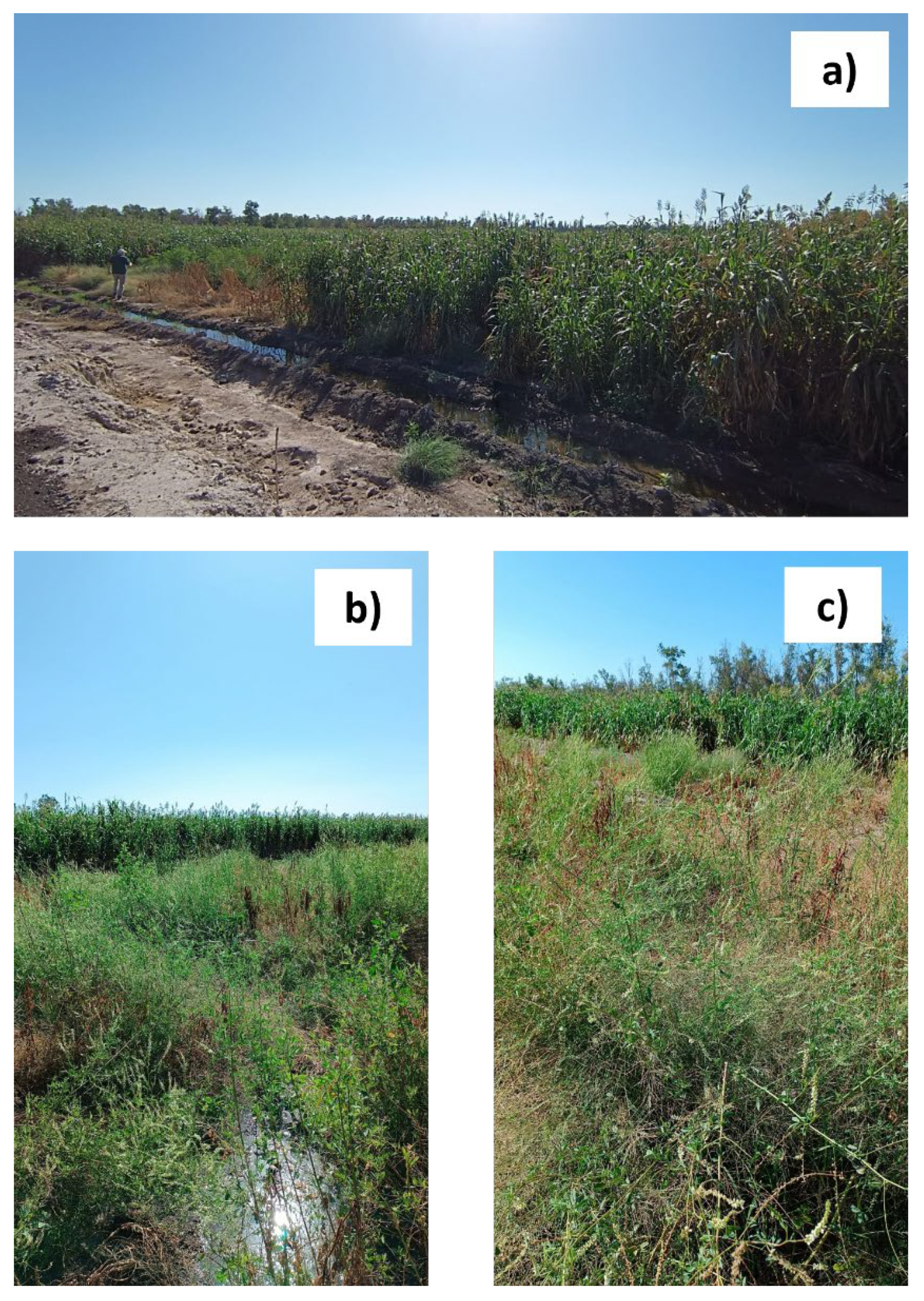

Sorghum plots showed better homegenity in settlement (Fig. 2), while pasture showed more variability in this parameter, reaching an average dry biomass yield equivalent to 32.6 and 6.5 Tn/ha, respectively (

Table 7). On the other hand, these results suggest that sorghum has better establishment abilities in saline soils irrigated with high salinity effluents. These results are in agreement with the exploratory study.

Figure 2.

a) General view of the plots cultivated in the field assay (in the front: perennial pasture; in the background: sorghum); b) North view of the plots cultivated in the field assay (in the front: perennial pasture; in the background: sorghum); c) South view of the plots cultivated in the field assay (in the front: perennial pasture; in the background: sorghum).

Figure 2.

a) General view of the plots cultivated in the field assay (in the front: perennial pasture; in the background: sorghum); b) North view of the plots cultivated in the field assay (in the front: perennial pasture; in the background: sorghum); c) South view of the plots cultivated in the field assay (in the front: perennial pasture; in the background: sorghum).

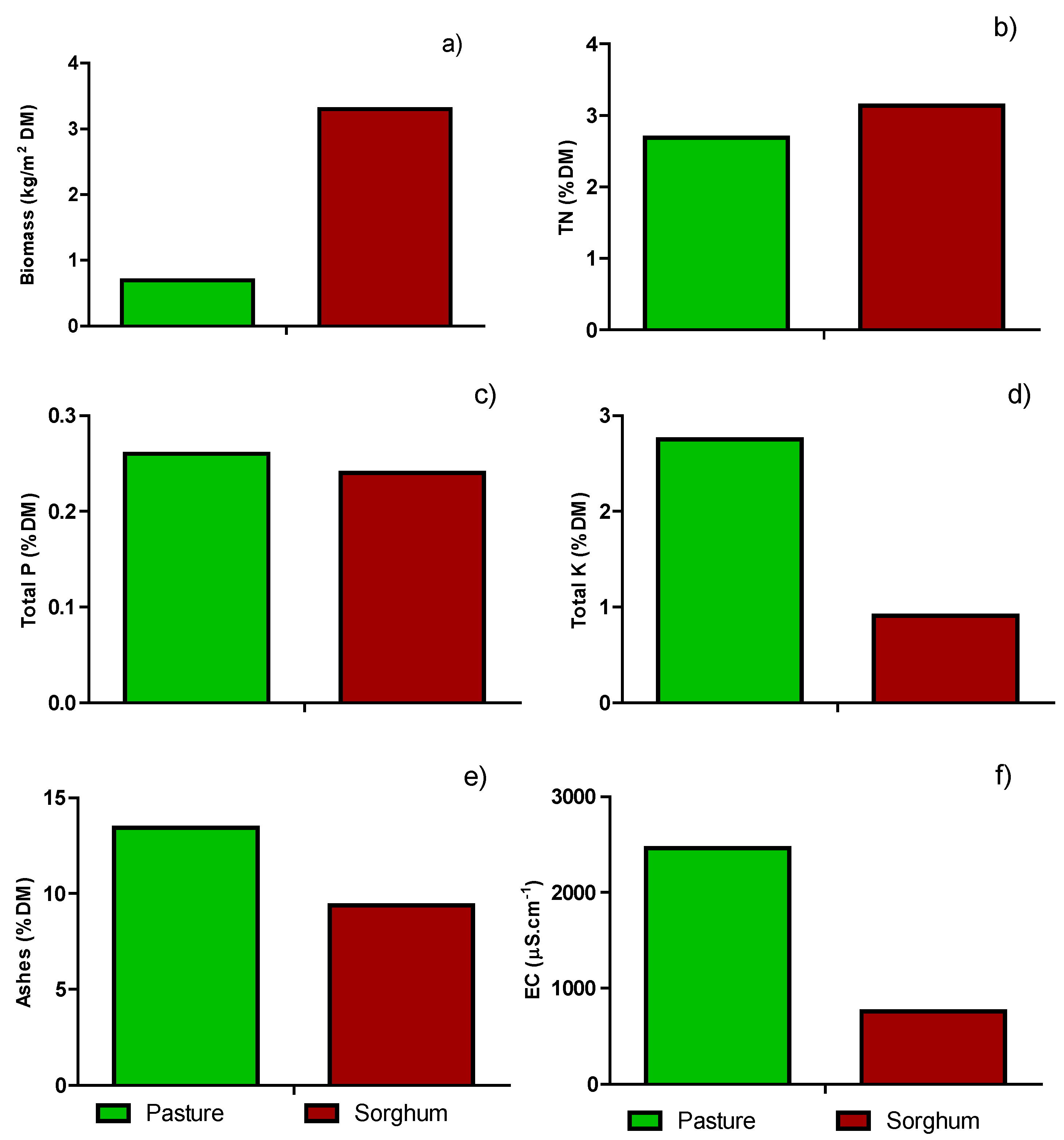

Although sorghum had a higher biomass yield than pasture (Fig. 3), pasture was more efficient in nutrient uptake in different soil extracts (

Table 5 and 6).This is closely related to the nutrient analysis found in plant biomass (Fig. 3). Most of the analysed macronutrients (NPK), ash content and soluble salts (EC) are more concentrated in the pasture biomass.

This fact presents different alternatives according to the production objectives. If the main strategy has the objective of maximising biomass production (e.g. for bioenergy, animal feed or composting ), the most appropriate approach would be to plant a summer annual crop such as sorghum. On the contray, if the strategy is to capture as much of the nutrients provided by the effluent, the most appropriate approach would be to plant a summer polyphytic pasture (e.g. sweet clover and wheatgrass).

Figure 3.

a) Biomass harvested (pasture and sorghum) in the plot assay under (kg/m2 dry weight); b) Total nitrogen contend in biomass; c) Total phophorous contend in biomass; d) Total potassium content in biomass; e) Ashes content in biomass; f) Electrical conductivity in biomass.

Figure 3.

a) Biomass harvested (pasture and sorghum) in the plot assay under (kg/m2 dry weight); b) Total nitrogen contend in biomass; c) Total phophorous contend in biomass; d) Total potassium content in biomass; e) Ashes content in biomass; f) Electrical conductivity in biomass.

4. Discussion

From the results obtained in this study, it is evident that the use of distillery effluents from the processing of viticulture by-products represents a valuable strategy in the sustainable management of water resources and waste in arid regions. Regarding this, recent research has shown that these nutrient-rich effluents can be effectively used in crop irrigation, contributing to agricultural production and reducing pollution load in arid regions. For instance, Buelow et al. (2015) analyzed the reuse of viticultural wastewater in a drought context in California [

15]. The authors note that the treatment of this wastewater reduces the levels of biological oxygen demand (BOD

5) and dissolved organic carbon, which minimizes the negative effects on soil and plants. However, dissolved salts, especially sodium and potassium, persist after treatment, presenting a challenge for irrigation use. Despite this, overall salinity was moderate, and the treated water is, in most cases, suitable for salinity-tolerant crops such as grapes [

15]. In this sense, the effluents treated in our study also presented high levels of salts, mainly Ca>K>Na>Mg (EC of EGM: 13.57 dS/cm; EC of V: 17.88 dS/cm). Therefore, it is recommended to dilute the effluent (9%). This dilution made it possible to reduce water consumption by 9% and to provide nutrients for the crops.

On the other hand, Livia et al. (2020) analyzed wastewater treatment alternatives for viticulture wastewater considering technical, economic, social and environmental aspects. The results show that wastewater derived from viticulture can be complemented but does not fully replace conventional water sources in the region. Among the options evaluated, the septic tank combined with a constructed wetland was the most sustainable according to local preferences. This study underlines the importance of integrating environmental and social criteria in decision-making on wastewater reuse [

16]. This aspect should be considered, to avoid salinity risks associated with water balance and nutrient uptake by crops. In the case of this study, the challenge is to have an adequate effluent containment system, diluted effluent channelling and sufficient arable land to avoid salinisation problems. In addition, the water demand of the crops and the atmospheric demand must be taken into account in order to design a correct irrigation programme, avoiding temporary waterlogging and salt accumulation.

Recent studies have evaluated the use of vinasse, a liquid residue generated in the production of alcohol from sugar cane, sugar beet, mezcal and tequila, as a soil amendment. Although they provide nutrients and organic matter, they can also alter soil properties, increase salinity and negatively affect microbiota. The application of vinasse increases greenhouse gas emissions (CO₂, CH₄ and N₂O), which contributes to global warming. The authors conclude that its agricultural use requires regulations and controlled doses to minimize environmental impact, especially in soils with high salinity and in areas close to water sources [

17]. The effluent in our study presented different characteristics to those evaluated by these authors, presenting less risk of salinity and organic load. However, the recommendations by Moran-Salazar et al. (2016) should be considered to avoid environmental problems due to a cumulative effect of the application of effluents derived from the distillation of wine by-products.

Khaskhoussy et al. (2020) evaluated the use of distillery effluent in maize (

Zea mays) irrigation, finding that this wastewater not only promoted vegetative growth, but also improved soil properties, increasing the availability of essential nutrients [

18]. This finding is consistent with our research that reported an increase in the biomass of crops irrigated with wine effluent, evidencing the possibility of reusing these by-products in agricultural systems in arid regions with high environmental constraints. The authors highlight that treated wastewater can be used for irrigation in different soil types, and that factors such as pH, clay content, carbonates and organic matter affect the accumulation of toxic metals in plants and soil. However, high levels of certain metals in crops vary between species, suggesting that the risk may depend on the type of crop. The authors highlight the importance of more field studies and advanced analytical techniques to better assess contamination and health risks, especially in the prolonged use of treated wastewater in the face of stricter environmental regulations [

18]. These recommendations are applicable to our study because, although the application of the diluted effluent promoted crop establishment and growth, the salt content in the soil was increased.

A long-term study suggests that the inorganic material present in effluents accumulates with successive applications over time, which is of concern as most wastewater treatment processes fail to significantly reduce salt concentrations in wastewater flows. However, it is highlighted that the application of effluents generated in the industrialization of viticultural by-products is an alternative that can provide greater competitiveness of the sector in arid environments, generating vegetal biomass for various uses in a circular economy framework [

19]. In this sense, the authors highlight that the incorporation of distillery effluent from viticultural waste into irrigation systems not only allows for sustainable waste management, but also optimizes the use of water resources and improves agricultural productivity. The combination of these approaches may be key to promoting more sustainable agricultural practices in viticulture, improving productivity in arid areas and generating biomass for various commercial purposes. The present study confirms the conclusion provided by Mosse et al. (2012) that the diluted effluent now allowed the water resource to be reduced by 9% and provided nutrients and water for optimal development of pasture and sorghum. However, precautions should be taken to avoid problems associated with soil salinity.

5. Conclusions

Agro-industrial waste and effluents pose challenges in arid areas due to water scarcity and high organic loads. This study explores using effluents to grow plant biomass, showing sorghum as highly efficient in dry biomass yield (32.6 Tn/ha) compared to pasture (6.5 Tn/ha). Sorghum’s tolerance to salinity makes it suitable for bioenergy, animal feed, or as a compost co-substrate, while pastures, though lower in biomass, excel in nutrient capture, ideal for nutrient recovery goals. Both crops help moderate soil salinity, with pasture reducing electrical conductivity more effectively. This flexibility enables tailored crop choices based on biomass or nutrient recovery objectives, warranting further research on economic and long-term impacts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F.R. and M.U.; methodology, P.F.R., L.E.M. and F.F.; software, F.F. and I.F.P..; validation, G.A. and F.D.B..; formal analysis, I.F.P..; investigation, P.F.R..; resources, P.M., G.F. and P.F.R..; data curation, I.F.P., G.A and P.F.R..; writing—original draft preparation, P.F.R and A.S.; writing—review and editing, P.F.R and A.S.; visualization, P.F.R and A.S.; supervision, P.F.R and M.U.; project administration, G.A.; funding acquisition, P.F.R, G.F. and P.M.

Funding

This research was funded by Technical Assistance Agreement Institutional INTA - DERVINSA, INTA Project PD 122 (Code: 1.7.2.L4.PD.I122) and FONCYT Project (Code: PICT 2021-I-INVI-00431).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the cooperation of DERVINSA company.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sánchez, Ó.J., Ospina, D.A., Montoya, S. Compost supplementation with nutrients and microorganisms in composting process. Waste Manag. 2017, 69, 136–153. [CrossRef]

- Laca, A., Gancedo, S., Laca, A., & Díaz, M. Assessment of the environmental impacts associated with vineyards and winemaking. A case study in mountain areas. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 1204–1223.

- Instituto Nacional de Vitivinicultura (INV). Informe anual de superficie 2023. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/inv/vinos/estadisticas/superficie/anuarios (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Kontogiannopoulos, K.N. , Patsios, S.I., Karabelas, A.J., Tartaric acid recovery from winerylees using cation exchange resin: Optimization by response surface methodology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 165, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigno, G., Marinoni, L., & Garrido, G. D. State of the art in grape processing by-products. In Handbook of grape processing by-products. Editor: Galanakis, C.M. Academic Press. Vienna, Austria; Volume 1, 2017, 1-27.

- Muhlack, R. A., Potumarthi, R. and Jeffery, D. W. Sustainable wineries through waste valorisation: A review of grape marc utilisation for value-added products. Waste Manag. 2018, 72, 99-118.

- Pinter, I. F., Fernández, A. S., Martínez, L. E., Riera, N., Fernández, M., Aguado, G. D., & Uliarte, E. M. Exhausted grape marc and organic residues composting with polyethylene cover: Process and quality evaluation as plant substrate. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 246, 695-705.

- Conicet. Soil map of the province of Mendoza, Argentina. Available online: https://www.mendoza-conicet.gob.ar/ladyot/catalogo/cdandes/g0407.htm (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Bautista, E., Schlegel, J. L., & Strelkoff, T. S. WinSRFR 4.1-user manual. 2012, USDA-ARS Arid Land Agricultural Research Center, 21881.

- APHA. Standard methods for examination of water and wastewater, 18th edition. Washington, USA, 1992.

- NTA. Compendium of analytical methods for the characterization of agricultural and agro-industrial waste, compost and effluents. 1st ed. Editors: Martinez, L., Rizzo, P.F., Bres, P.A., Riera, N.I., Beily, M.E., Young, B.J. INTA Ed., Argentina (in Spanish). 2021; pp. 1-166.

- SAMLA. Compilation of laboratory techniques. Methodological Support System for Laboratories of Soil, Water, Vegetable and Organic Amendment Analysis (SAMLA). Secretariat of Agriculture, Livestock, Fishing and Foods, Buenos Aires, Argentina (in Spanish). 2004.

- Nijenshon, L., Maffei, J. Estimación de la salinidad y otras características edáficas a través de los volúmenes de sedimentación. Cienc. Del Suelo. 1996, 14: 119–121.

- Jeong, H.; Kim, H.; Jang, T. Irrigation Water Quality Standards for Indirect Wastewater Reuse in Agriculture: A Contribution toward Sustainable Wastewater Reuse in South Korea. Water. 2016, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelow, M. C., Steenwerth, K., Silva, L. C., Parikh, S. J. Characterization of winery wastewater for reuse in California. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2015, 66(3), 302–310. [CrossRef]

- Livia, S., María, M. S., Marco, B., Marco, R. Assessment of wastewater reuse potential for irrigation in rural semi-arid areas: the case study of Punitaqui, Chile. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy. 2020, 22, 1325-1338.

- Moran-Salazar, R.G., Sanchez-Lizarraga, A.L., Rodriguez-Campos, J., Davila-Vazquez, G., Marino-Marmolejo, E. N., Dendooven, L., Contreras-Ramos, S. M. Utilization of vinasses as soil amendment: consequences and perspectives. SpringerPlus. 2016, 5, 1007. [CrossRef]

- Khaskhoussy, K., Kahlaoui, B., Misle, E., Hachicha, M. Impact of Irrigation with Treated Wastewater on Physical-Chemical Properties of Two Soil Types and Corn Plant (Zea mays). J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 1377–1393. [CrossRef]

- Mosse, K. P. M., Patti, A. F., Smernik, R. J., Christen, E. W., Cavagnaro, T. R. Physicochemical and microbiological effects of long-and short-term winery wastewater application to soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 201, 219-228.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).