Submitted:

15 June 2023

Posted:

16 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Collection of Material

2.2. Determination of metal content

2.3. Determination of the width of the annual rings of pine trunks

2.4. Statistical data processing

3. Results

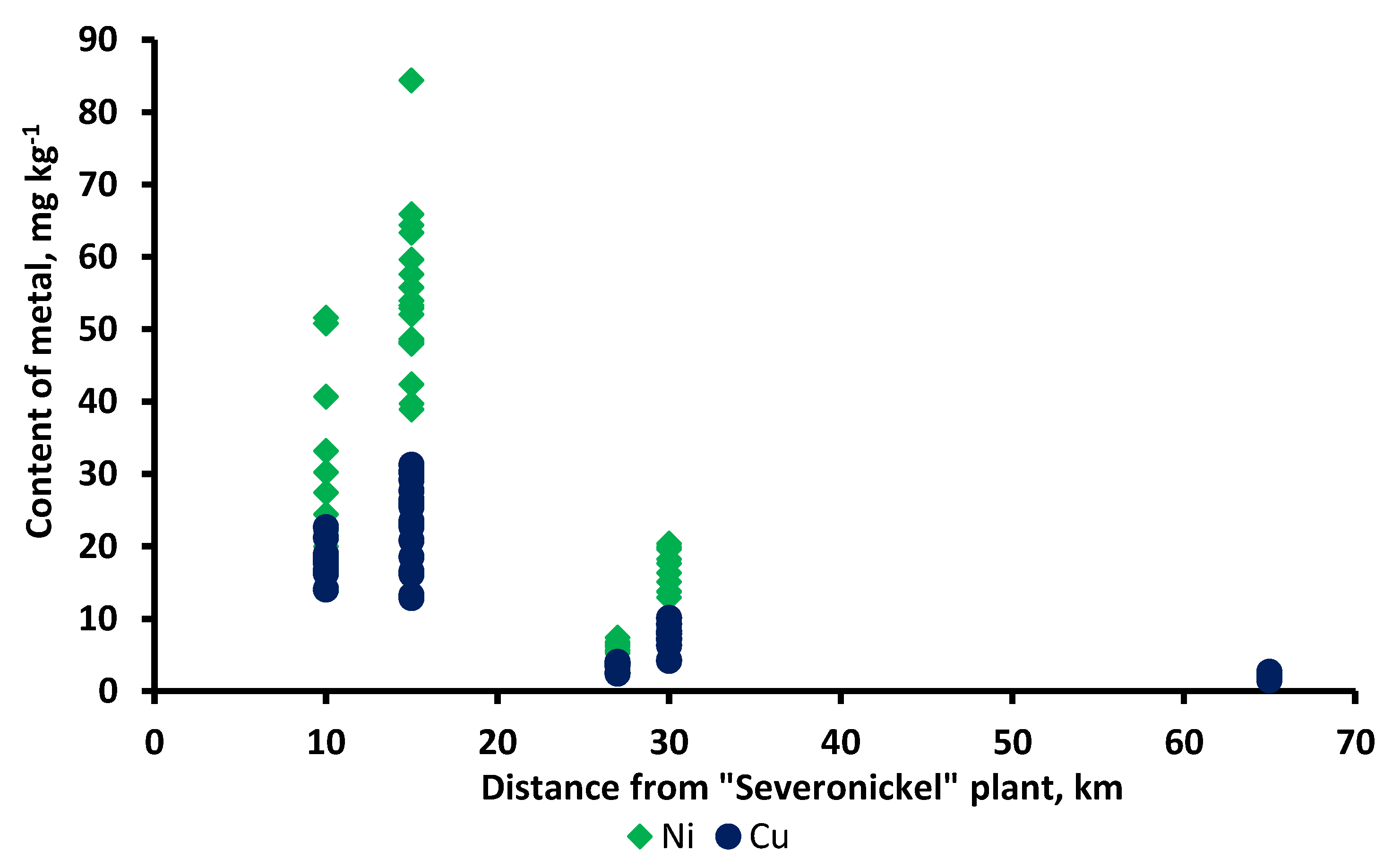

3.1. Soil properties

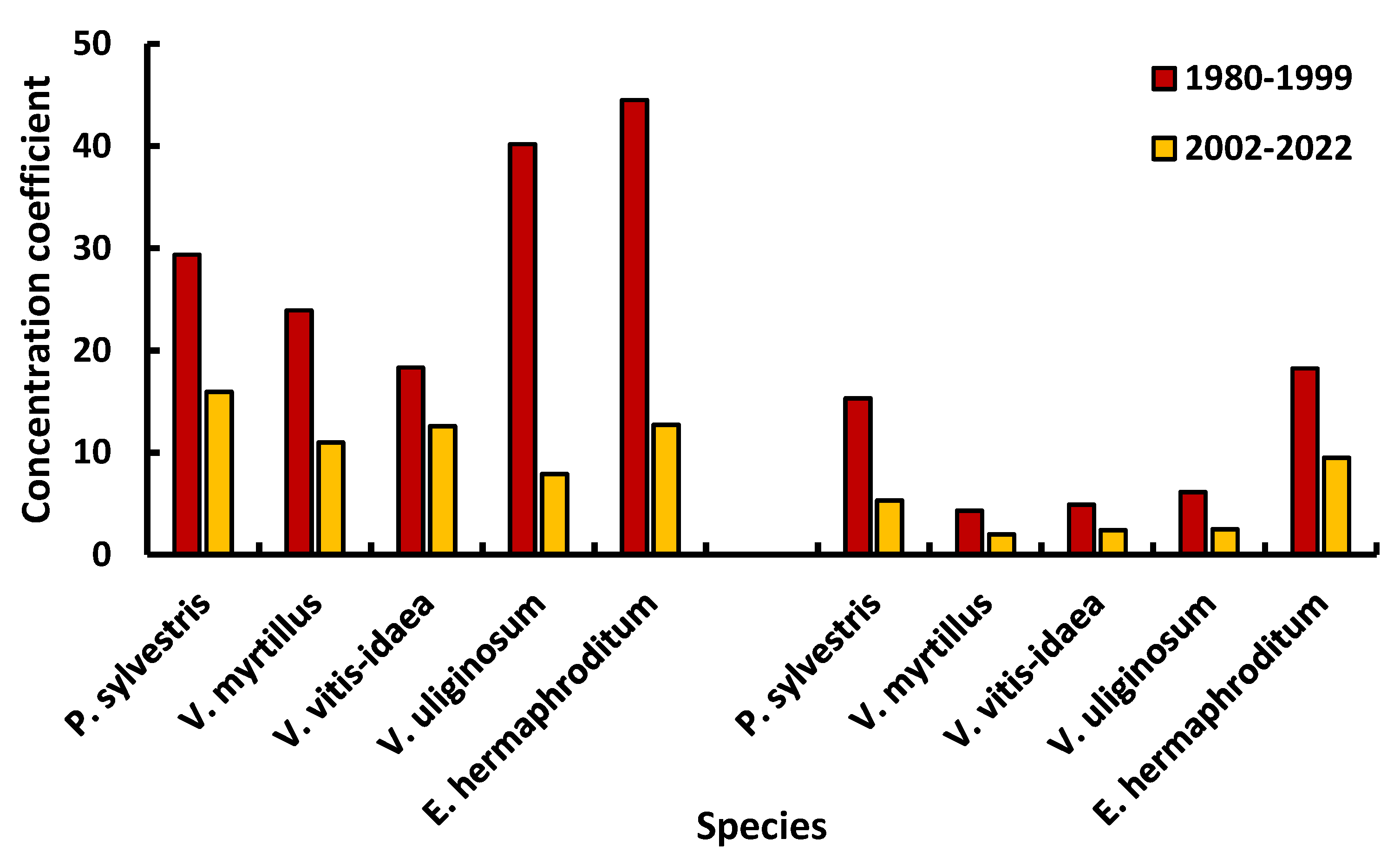

3.2. Heavy Metal Contents in Forest Plants

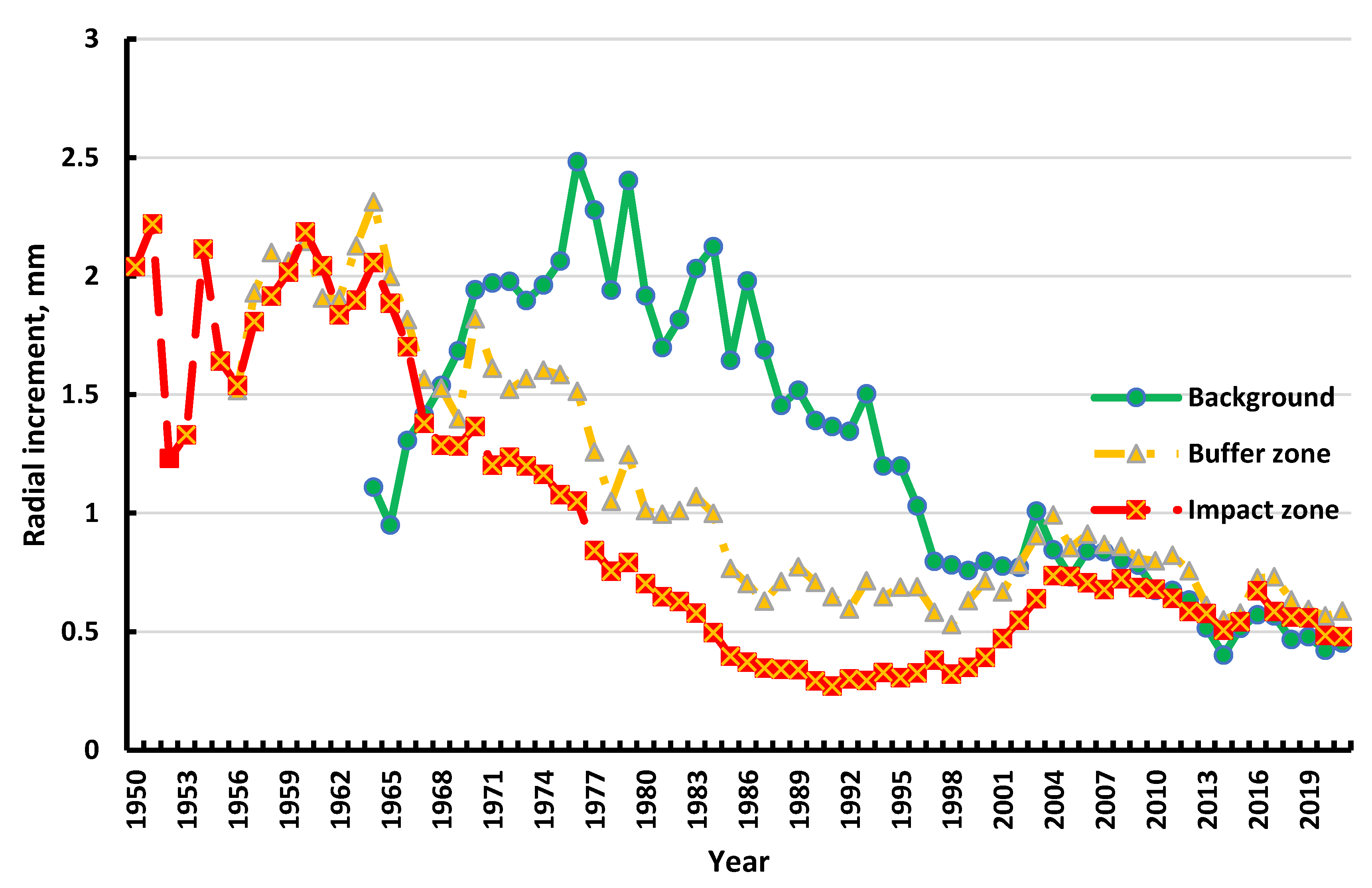

3.3. Growth Ring width of Pinus Sylvestris Trees

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Phytotoxicity

4.2. Plants Are Bioindicators of Environmental Pollution

4.3. Assessment of Potential Risks to Human Health

4.4. The Reaction of the Growth Ring Width of Pinus Sylvestris Trees to a Decrease in the Intensity of Aerotechnogenic Emissions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salemaa, M. , Vanha-Majamaa I., Derome J. 2001. Understory vegetation along a heavy-metal pollution gradient in SW Finland. Environmental Pollution. V. 112, N 3. P. 339.

- Salemaa, M.; Derome, J.; Helmisaari, H.-S.; Nieminen, T.; Vanhamajamaa, I. Element accumulation in boreal bryophytes, lichens and vascular plants exposed to heavy metal and sulfur deposition in Finland. Sci. Total. Environ. 2004, 324, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brekken, A.; Steinnes, E. Seasonal concentrations of cadmium and zinc in native pasture plants: consequences for grazing animals. Sci. Total. Environ. 2004, 326, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białońska, D.; Zobel, A.M.; Kuraś, M.; Tykarska, T.; Sawicka-Kapusta, K. Phenolic Compounds and Cell Structure in Bilberry Leaves Affected by Emissions from a Zn–Pb Smelter. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2007, 181, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, M.V. , Zvereva E.L., Zverev V.E. Impacts of point polluters on terrestrial biota. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London, New-York, 2009. 466 р.

- Pająk, M.; Gąsiorek, M.; Jasik, M.; Halecki, W.; Otremba, K.; Pietrzykowski, M. Risk Assessment of Potential Food Chain Threats from Edible Wild Mushrooms Collected in Forest Ecosystems with Heavy Metal Pollution in Upper Silesia, Poland. Forests 2020, 11, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtuń, B.; Samecka-Cymerman, A.; Żołnierz, L.; Rajsz, A.; Kempers, A.J. Vascular plants as ecological indicators of metals in alpine vegetation (Karkonosze, SW Poland). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 20093–20103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyanguzova, I. , Yarmishko, V., Gorshkov, V., Stavrova, N., and Bakkal, I. 2018. Impact of heavy metals on forest ecosystems of the European North of Russia, in Heavy Metals, London: IntechOpen. p. 91.

- Myking, T. , Aarrestad P.A., Derome J. et al. 2009. Effects of air pollution from a nickel–copper industrial complex on boreal forest vegetation in the joint Russian–Norwegian–Finnish border area. Boreal Environ. Res. V. 14. P. 279.

- Conti, M.; Cecchetti, G. Biological monitoring: lichens as bioindicators of air pollution assessment — a review. Environ. Pollut. 2001, 114, 471–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmens, H.; Norris, D.A.; Steinnes, E.; Kubin, E.; Piispanen, J.; Alber, R.; Aleksiayenak, Y.; Blum, O.; Coşkun, M.; Dam, M.; et al. Mosses as biomonitors of atmospheric heavy metal deposition: Spatial patterns and temporal trends in Europe. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 3144–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, O.W.; Williamson, B.J.; Spiro, B.; Udachin, V.; Mikhailova, I.N.; Dolgopolova, A. Lichen monitoring as a potential tool in environmental forensics: case study of the Cu smelter and former mining town of Karabash, Russia. Geol. Soc. London, Spéc. Publ. 2013, 384, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescott, O.L.; Simkin, J.M.; August, T.A.; Randle, Z.; Dore, A.J.; Botham, M.S. Air pollution and its effects on lichens, bryophytes, and lichen-feeding Lepidoptera: review and evidence from biological records. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2015, 115, 611–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkan V., Sh. , Lyanguzova I. V.2018. Concentration of Heavy Metals in Dominant Moss Species as an Indicator of Aerial Technogenic Load. Rus. J. of Ecology. V. 49, N2. P. 128.

- Rola, K.; Osyczka, P. Cryptogamic communities as a useful bioindication tool for estimating the degree of soil pollution with heavy metals. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 88, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, S.B. 1985. Effects of air pollution on forests. J. APCA (Air Pollution Control Association). Vol. 35. P. 512–534.

- Zvereva E., Roitto M., Kozlov M. 2010. Growth and reproduction of vascular plants in polluted environments: a synthesis of existing knowledge // Environ. Rev. 18: 355–367.

- Ayras, M. , Kashulina G. 2000. Regional patterns of element contents in the organic horizon of podzols in the central part of the Barents region (Finland, Norway and Russia), with special reference to heavy metals (Co, Cr, Fe, Ni, Pb, V and Zn) and sulphur as indicators of airborne pollution. J. Exploration Geochem. V. 68. P. 127–144.

- Kozlov, M.V.; Zvereva, E.L. Industrial barrens: extreme habitats created by non-ferrous metallurgy. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technology 2007, 6, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashulina, G. , de Caritat P., Reimann C. 2014. Snow and rain chemistry around the “Severonikel” industrial complex, NW Russia: Current status and retrospective analysis. Atmospheric Environ. V. 89. P. 672–682.

- Kashulina, G.M. Extreme pollution of soils by emissions of the copper–nickel industrial complex in the Kola Peninsula. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2017, 50, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashulina, G.M. Monitoring of Soil Contamination by Heavy Metals in the Impact Zone of Copper-Nickel Smelter on the Kola Peninsula. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2018, 51, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukina, N.V.; Orlova, M.A.; Steinnes, E.; Artemkina, N.A.; Gorbacheva, T.T.; Smirnov, V.E.; Belova, E.A. Mass-loss rates from decomposition of plant residues in spruce forests near the northern tree line subject to strong air pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 19874–19887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ershov, V.V.; Lukina, N.V.; Danilova, M.A.; Isaeva, L.G.; Sukhareva, T.A.; Smirnov, V.E. Assessment of the Composition of Rain Deposition in Coniferous Forests at the Northern Tree Line Subject to Air Pollution. Russ. J. Ecol. 2020, 51, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.G.; Lawton, J.H.; Shachak, M. Organisms as Ecosystem Engineers. Oikos 1994, 69, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkowski, R.; Buttle, J.M. Stemflow and throughfall contributions to soil water recharge under trees with differing branch architectures. Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 4068–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischbier, N. and Wagner, S. 2015. Detection, quantification and modelling of small-scale lateral translocation of throughfall in tree crowns of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) and Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst). J. Hydrol. vol. 522, pp. 228–238.

- Levia, D.F.; Germer, S. A review of stemflow generation dynamics and stemflow-environment interactions in forests and shrublands. Rev. Geophys. 2015, 53, 673–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, R.; Jóźwiak, M. 2017. The transformation of precipitation in the tree canopy in selected forest ecosystems of Poland’s Świętokrzyskie Mountains. Pol. Geograph. Rev. 89, 1, 133-153.

- Nilsson, U. , Gemmel P. 1993. Changes in growth and allocation of growth in young Pinus sylvestris and Picea abies due to competition. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 8: 213–222.

- Monserud, R.A.; Sterba, H. A basal area increment model for individual trees growing in even- and uneven-aged forest stands in Austria. For. Ecol. Manag. 1996, 80, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, S. Crown Condition and Growth Relationships within Stands of Picea abies. Scand. J. For. Res. 1999, 14, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A. The effect of size and competition on tree growth rate in old-growth coniferous forests. Can. J. For. Res. 2012, 42, 1983–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidko, D.A. , Krivets C.A., Bisirova E.M. 2010. Connection between radial increment and tree vitality of Siberian stone pine. Tomsk State University Journal. Biology. 4: 68–80.

- Bigler, C.; Bugmann, H. Growth-dependent tree mortality models based on tree rings. Can. J. For. Res. 2003, 33, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbertin, M. 2005. Forest growth as indicator of tree vitality and tree reaction to environmental stress: a review. European Journal of Forest Research 124(4): 319–333.

- Hereş, A.-M.; Kaye, M.W.; Granda, E.; Benavides, R.; Lázaro-Nogal, A.; Rubio-Casal, A.E.; Valladares, F.; Yuste, J.C. Tree vigour influences secondary growth but not responsiveness to climatic variability in Holm oak. Dendrochronologia 2018, 49, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ставрoва,..; Катютин,..; Stavrova, N.; Gorshkov, V.; Katyutin, P. 2016. Structure formation of forest tree species coenopopulations during post-fire recovery of northern taiga forest. Transactions of the Karelian Research Center of the Russian Academy of Science. Biogeography Series 3: 10–28. [CrossRef]

- Katjutin, P.N. , Stavrova N.I., Gorshkov V.V., Lyanguzov A.Yu., Bakkal I.Ju., Mikhailov S.A. 2020. Radial growth of trees differing in their vitality in the middle-aged Scots pine forests in the Kola peninsula. Silva Fennica. Vol. 54(3). article id 10263.

- Katyutin, P.N. , Gorshkov V.V. 2020. Vitality, Growth Speed and Aboveground Biomass of Pinus sylvestris (Pinaceae) in Middle-Aged North Taiga Forests. Rastitelnye resursy 56(2): 99–111.

- Gorshkov, V.V. , Stavrova N.I., Katjutin P.N., Lyanguzov A.Yu. 2021. Radial Increment of Scots Pine Pinus sylvestris L. in the Northern Taiga Lichen Pine Forests and Woodlands. Biology Bulletin. No2. P. 200–210.

- Atlegrim, O.; Sjöberg, K. Response of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) to clear-cutting and single-tree selection harvests in uneven-aged boreal Picea abies forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 1996, 86, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uotila, A.; Kouki, J. Understorey vegetation in spruce-dominated forests in eastern Finland and Russian Karelia: Successional patterns after anthropogenic and natural disturbances. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 215, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uotila, A.; Hotanen, J.-P.; Kouki, J. Succession of understory vegetation in managed and seminatural Scots pine forests in eastern Finland and Russian Karelia. Can. J. For. Res. 2005, 35, 1422–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turtiainen, M. , Salo, K., Saastomoinen, O., 2011. Variation of yield and utilisation of bilberries (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) and cowberries (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.) in Finland. Silva Fenn. 45 (2), 237–251.

- Turtiainen, M.; Miina, J.; Salo, K.; Hotanen, J.-P. Empirical prediction models for the coverage and yields of cowberry in Finland. Silva Fenn. 2013, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A. , Kouki J. 2015. Emulating natural disturbance in forest management enhances pollination services for dominant Vaccinium shrubs in boreal pine-dominated forests // Forest Ecology and Management. 350. 1–12.

- Lyanguzova, I.V. Airborne Heavy Metal Pollution and its Effects on Biomass of Ground Vegetation, Foliar Elemental Composition and Metabolic Profiling of Forest Plants in the Kola Peninsula (Russia). Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 68, S140–S149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlig, C. , Junttila J. 2001. Airborne heavy metal pollution and its effect on foliar elemental composition of Empetrum hermaphroditum and Vaccinium myrtillus in Sor-Varanger, northern Norway. Environmental Pollution. Vol. 114. P. 461–469.

- Martz, F.; Jaakola, L.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R.; Stark, S. Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Capacity of Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) Leaves in Northern Europe Following Foliar Development and Along Environmental Gradients. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakka, J.; Kouki, J. Patterns of field layer invertebrates in successional stages of managed boreal forest: Implications for the declining Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus L. population. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihalainen, M.; Alho, J.; Kolehmainen, O.; Pukkala, T. Expert models for bilberry and cowberry yields in Finnish forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 157, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroz, L. and Demczuk, M. 2010. Contents of phenolics and chemical elements in bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) leaves from copper smelter area (SW Poland). Pol. J. Ecol. vol. 58, p. 475.

- Afanasyeva, L.V. and Kashin, V.K. 2016. Accumulation and distribution of microelements in above- and underground parts Vaccinium vitis-idaea (Ericaceae) in the Southern Pre-Baikal region, Plant Res. vol. 52, p. 434.

- Fursa, N.S. , Kruglov, D.S., and Belokurov, M.M. 2017. The element composition of the leaves of plants of the Vaccinium genus. Pharmaciya. vol. 66, p. 33.

- Kandziora-Ciupa, M.; Ciepał, R.; Nadgórska-Socha, A.; Barczyk, G. A comparative study of heavy metal accumulation and antioxidant responses in Vaccinium myrtillus L. leaves in polluted and non-polluted areas. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 4920–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandziora-Ciupa, M.; Nadgórska-Socha, A.; Barczyk, G.; Ciepał, R. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals and ecophysiological responses to heavy metal stress in selected populations of Vaccinium myrtillus L. and Vaccinium vitis-idaea L. Ecotoxicology 2017, 26, 966–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcan, V. Leaching of nickel and copper from soil contaminated by metallurgical dust. Environ. Int. 2002, 28, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinn, F. 2003. TSAP-Win: time series analysis and presentation for dendrochronology and related applications: User reference. RINNTECH, Heidelberg, 110 p.

- Guiterman, C.H.; Margolis, E.Q.; Swetnam, T.W. Dendroecological Methods For Reconstructing High-Severity Fire In Pine-Oak Forests. Tree-Ring Res. 2015, 71, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps; World Soil Resources Report No. 106; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lyanguzova I., V. , Goldvirt D. K., Fadeeva I. K. 2016. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of the Pollution of Al–Fe-Humus Podzolsin the Impact Zone of a Nonferrous Metallurgical Plant Eurasian Soil Science. Vol. 49, No. 10, pp. 1189–1203.

- Evdokimova, G.A. , Mozgova N.P. 1993. Soil contamination by heavy metals in surroundings of Monchegorsk and recovering after industrial impact. Aerial pollution in Kola peninsula: Proc. Intern. Workshop. Apatity. P. 148–152.

- Kopstik, G.N. 2014. Problems and prospects concerning the phytoremediation of heavy metal polluted soils: a review. Eurasian Soil Science. N 9. P. 923–939.

- Evdokimova, G.A. , Mozgova N.P., Korneikova M.V. 2015. The content and toxicity of heavy metals in soils affected by aerial emissions from the Pechenganickel plant. Eurasian Soil Science. N 5. P. 504–510.

- Vorobeichik, E.L.; Trubina, M.R.; Khantemirova, E.V.; Bergman, I.E. Long-term dynamic of forest vegetation after reduction of copper smelter emissions. Russ. J. Ecol. 2014, 45, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadulin, M.S.; Koptsik, G.N. Carbon Dioxide Emission by Soils as a Criterion for Remediation Effectiveness of Industrial Barrens Near Copper-Nickel Plants in the Kola Subarctic. Russ. J. Ecol. 2019, 50, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabata-Pendias, A. , Pendias H. 2001. Trace elements in soil and plants. London: CRC Press. 413 p.

- Kalač, P.; Svoboda, L. A review of trace element concentrations in edible mushrooms. Food Chem. 2000, 69, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Melgar, M.J.; García, M.A.; Pérez-López, M. The Concentrations and Bioconcentration Factors of Copper and Zinc in Edible Mushrooms. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2003, 44, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M.A. , Alonso J., Melgar M.J. 2009. Lead in edible mushrooms. Levels and bioconcentration factors. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 167, pp. 777-783.

- Brzostowski, A.; Falandysz, J.; Jarzyńska, G.; Zhang, D. Bioconcentration potential of metallic elements by Poison Pax (Paxillus involutus) mushroom. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. Part A 2011, 46, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarzyńska, G. , Gucia M., Kojta A.K., Rezulak K., Falandysz J. 2011. Profile of trace elements in Parasol Mushroom (Macrolepiota procera) from Tucholskie Forest Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B, 46, pp. 741–751.

- Falandysz, J.; Frankowska, A.; Jarzynska, G.; Dryzałowska, A.; Kojta, A.K.; Zhang, D. Survey on composition and bioconcentration potential of 12 metallic elements in King Bolete (Boletus edulis) mushroom that emerged at 11 spatially distant sites. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. Part B 2011, 46, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipka, K. Falandysz J. 2017. Accumulation of metallic elements by Amanita muscaria from rural lowland and industrial upland regions. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B, 52(3), pp. 184–190.

- Juknys, R.; Augustaitis, A.; Venclovienė, J.; Kliučius, A.; Vitas, A.; Bartkevičius, E.; Jurkonis, N. Dynamic response of tree growth to changing environmental pollution. Eur. J. For. Res. 2013, 133, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacek, S.; Vacek, Z.; Bílek, L.; Simon, J.; Remeš, J.; Hůnová, I.; Král, J.; Putalová, T.; Mikeska, M. Structure, regeneration and growth of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) stands with respect to changing climate and environmental pollution. Silva Fenn. 2016, 50, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyanguzova, I.V. , Bondarenko M.S., Belyaeva A.I., Kataeva M.N., Barkan V.Sh., Lyanguzov A.Yu. 2020. Migration of Heavy Metals from Contaminated Soil to Plants and Lichens under Conditions of Field Experiment on the Kola Peninsula. Rus. J. of Ecology. V. 51, N. 6. P. 527.

- Trubina, M.R. , Vorobeichik E.L., Khantemirova E.V., Bergman I.E., Kaigorodova S.Y. 2014. Dynamics of forest vegetation after the reduction of industrial emissions: fast recovery or continued degradation? Doklady Biological Sciences. V. 458. N 1. P. 302–305.

- Alexeeva-Popova, N.V.; Drozdova, I.V. Micronutrient composition of plants in the Polar Urals under contrasting geochemical conditions. Russ. J. Ecol. 2013, 44, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seregin, I.V. , Kozhevnikova A.D. 2006. Physiological Role of Ni and its Toxic Effects on Higher Plants. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology. V. 53. № 2. С. 257-277.

- White, P.J. , Brown P. H. 2010. Plant nutrition for sustainable development and global health Annals of Botany. V. 105. P. 1073–1080.

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 629/2008 of 2 July 2008 amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs // Official Journal of the European Union. 03.07. 2008.

- JJECFA/73/SC. Joint 2010. FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. Seventy-third Meeting, Geneva, 8–17, June 2010.

- Choi Y., Y. Briefing on National and International Standards for Heavy Metals in Food. 18.10. 2012.

- Shchekalev, R.V. , Tarkhanov S.N. 2007. Radial growth of Scots pine under aerotechnogenic pollution in the Northern Dvina basin. Contemporary Problems of Ecology 2: 45–50.

- Ryabinina, Z.N.; Bastaeva, G.T.; A Lyavdanskaya, O.; Lebedev, S.V.; Kalyakina, R.G.; Ryabuhina, M.V. Radial growth of artificial forest stands under the aerotechnogenic impact of the Orenburg gas chemical complex. 2020, 579. 579. [CrossRef]

- Yarmishko, V.T. , Ignateva O.V. 2019. Impact Multi-year Monitoring of Pine Forests in the Central Part of the Kola Peninsula. Proceedings of the Russian academy of Sciences. Biological series. 6: 658–668.

- Yarmishko, V.T. , Ignatieva O.V. 2020. Growth Rate and Phytomass Structure of Pinus sylvestris (Pinaceae) in the Middle-Aged Scots Pine Forests of the Murmansk Region. Rastitelnye resursy 56(2): 314–325.

- Urazgildin, R.V. , Kulagin A.Yu. 2021. Structural and functional responses of arboreal plants to anthropogenic factors: Damages, adaptations and strategies. Part. III. Impact on the radial increment and on the rootage. Biosfera 13(4): 188–205.

- Yarmishko, V.T.; Ignat’eva, O.V. 2021. Communities of Pinus sylvestris L. in the technogenic environment in the European north of Russia: structure, features of growth, condition. Siberian Journal of Forestry Science. 3: 44–55.

- Kucherov, S.E. Muldashev A.A. 2003. Radial increment of Scots pine in the vicinity of the Karabash copper smelter. Contemporary Problems of Ecology 2: 43–49.

- Wertz, B. 2012. Dendrochronological evaluation of the impact of industrial emissions on main coniferous species in the Kielce Upland. Sylwan 156(5): 379–390.

- Stravinskiene, V.; Bartkevicius, E.; Plausinyte, E. Dendrochronological research of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) radial growth in vicinity of industrial pollution. Dendrochronologia 2013, 31, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensuła, B.; Opała, M.; Wilczyński, S.; Pawełczyk, S. Long- and short-term incremental response of Pinus sylvestris L. from industrial area nearby steelworks in Silesian Upland, Poland. Dendrochronologia 2015, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensuła, B.; Wilczyński, S.; Monin, L.; Allan, M.; Pazdur, A.; Fagel, N. Variations of tree ring width and chemical composition of wood of pine growing in the area nearby chemical factories. Geochronometria 2017, 44, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barniak, J.; Krąpiec, M. The Tree-Ring Method of Estimation of the Effect of Industrial Pollution on Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Tree Stands in the Northern Part of the Sandomierz Basin (SE Poland). Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2016, 227, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- uszczyńska, K. , Wistuba M., Malik I. 2018. Reductions in tree-ring widths of silver fir (Abies alba Mill.) as an indicator of air pollution in southern Poland // Environmental and Socio-Economic Studies. Vol. 6(3). P. 44-5.

- Rutkiewicz, P.; Malik, I. Spruce tree-ring reductions in relation to air pollution and human diseases a case study from Southern Poland. Environ. Socio-economic Stud. 2018, 6, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Zone | Age (1.3 m), years | Diameter (1.3 m), cm | Height, m |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background | 52±4* (45–59) |

15.3±2.6 (11.0–21.2) |

10.6±1.0 (9.0–12.4) |

| Buffer | 59±6 (40–65) |

15.4±4.4 (8.4–24.6) |

11.4±2.5 (6.0–15.5) |

| Impact | 63±4 (45–72) |

12.5±2.8 (9.2–19.0) |

8.1±1.3 (6.0–10.5) |

| Zone | Period | Metal | Mean | SD | Min | Max | CV [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | 1981–1997 | Ni | 9.1 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 16 | 42 |

| Cu | 9.2 | 4.6 | 2.8 | 18 | 49 | ||

| Co | 1.0 | 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0 | ||

| 2002–2018 | Ni | 13.3 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 22 | 45 | |

| Cu | 17.9 | 4.8 | 13.1 | 27 | 27 | ||

| Co | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 18 | ||

| Buffer | 1981–1997 | Ni | 49 | 17.3 | 17.8 | 68 | 35 |

| Cu | 54 | 31.4 | 13.7 | 110 | 58 | ||

| Co | 1.3 | 0.53 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 40 | ||

| 2002–2018 | Ni | 118 | 51.4 | 68 | 238 | 44 | |

| Cu | 264 | 123 | 174 | 547 | 46 | ||

| Co | 3.4 | 0.59 | 2.5 | 4.4 | 17 | ||

| Impact | 1981–1997 | Ni | 490 | 233 | 127 | 880 | 47 |

| Cu | 713 | 392 | 99 | 1200 | 55 | ||

| Co | 7.4 | 5.2 | 2.3 | 14.8 | 70 | ||

| 2002–2018 | Ni | 546 | 146 | 282 | 800 | 27 | |

| Cu | 1330 | 439 | 820 | 2180 | 33 | ||

| Co | 14.8 | 4.4 | 8.5 | 21.6 | 30 |

| Zone | Metal | N | a | b | R2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | Ni | 27 | 0.212 | -412.2 | 0.2586 | 0.0157 |

| Cu | 27 | 0.399 | -783.8 | 0.6316 | 0.00001 | |

| Co | 15 | 0.007 | -13.7 | 0.3278 | 0.0324 | |

| Buffer | Ni | 27 | 2.587 | -5088 | 0.4333 | 0.0002 |

| Cu | 27 | 7.878 | -15589 | 0.5636 | 0.00001 | |

| Co | 17 | 0.068 | -134.0 | 0.7545 | 0.00001 | |

| Impact | Ni | 27 | 3.732 | -6945 | 0.0716 | 0.1772 |

| Cu | 27 | 23.21 | -45364 | 0.3641 | 0.0009 | |

| Co | 17 | 0.228 | -443.7 | 0.3344 | 0.0150 |

| Specie | Metal | Mean | SD | CV [%] | Min | Max | z (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | |||||||

| Pinus sylvestris | Ni |

5.0 2.3 |

2.5 0.6 |

50 26 |

2.0 | 7.8 | 2.143 (0.085) |

| Cu |

4.3 2.3 |

2.2 0.6 |

51 26 |

1.5 | 6.8 | 1.760 (0.139) |

|

| Vaccinium myrtillus | Ni |

5.0 3.8 |

2.6 0.4 |

52 11 |

3.3 | 8.0 | 1.069 (0.326) |

| Cu |

7.3 6.6 |

1.8 3.3 |

25 50 |

2.8 | 11.7 | 0.299 (0.775) |

|

| Vaccinium vitis-idaea | Ni |

5.0 2.3 |

2.6 0.4 |

52 17 |

2.0 | 7.8 | 2.316 (0.060) |

| Cu |

4.8 4.4 |

1.2 2.4 |

25 55 |

2.5 | 8.6 | 0.241 (0.818) |

|

| Vaccinium uliginosum | Ni |

2.8 3.0 |

0.5 0.9 |

18 30 |

2.0 | 4.2 | –0.276 (0.790) |

| Cu |

5.4 3.7 |

0.6 2.3 |

11 62 |

2.2 | 8.8 | 1.222 (0.257) |

|

| Empetrum hermaphroditum | Ni |

12.9 5.7 |

2.9 2.7 |

22 47 |

3.2 | 16.1 | 3.439 (0.018) |

| Cu |

9.3 3.1 |

1.6 0.5 |

17 16 |

2.7 | 10.5 | 7.532 (0.001) |

|

| Buffer zone | |||||||

| Pinus sylvestris | Ni |

39.0 12.0 |

10.6 2.6 |

27 22 |

8.4 | 49 | 5.037 (0.004) |

| Cu |

18.1 4.9 |

10.4 1.5 |

57 31 |

3.4 | 30 | 2.603 (0.048) |

|

| Vaccinium myrtillus | Ni |

24.1 18.9 |

6.8 5.6 |

28 30 |

8.0 | 31.8 | 1.221 (0.262) |

| Cu |

10.7 8.7 |

4.5 3.9 |

42 45 |

3.4 | 15.8 | 0.718 (0.496) |

|

| Vaccinium vitis-idaea | Ni |

24.2 11.0 |

4.2 4.1 |

17 37 |

7.5 | 28.3 | 4.550 (0.003) |

| Cu |

7.8 5.9 |

2.1 2.2 |

27 37 |

3.5 | 10.0 | 1.283 (0.240) |

|

| Vaccinium uliginosum | Ni |

11.7 8.2 |

2.0 3.2 |

17 39 |

2.8 | 11.8 | 1.462 (0.204) |

| Cu |

9.3 5.2 |

2.0 2.3 |

22 44 |

2.1 | 10.7 | 2.163 (0.083) |

|

| Empetrum hermaphroditum | Ni |

32.7 24.5 |

12.0 10.3 |

37 42 |

13.2 | 45.0 | 0.845 (0.446) |

| Cu |

11.7 7.5 |

3.6 1.6 |

31 21 |

6.0 | 15.5 | 1.816 (0.143) |

|

| Impact zone | |||||||

| Pinus sylvestris | Ni |

147 37.5 |

39.7 18.5 |

27 49 |

20.6 | 190 | 5.480 (0.002) |

| Cu |

65.5 12.3 |

32.7 5.7 |

50 46 |

4.8 | 103 | 3.755 (0.009) |

|

| Vaccinium myrtillus | Ni |

119 41.1 |

23.2 11.6 |

19 28 |

24.9 | 136 | 7.350 (0.001) |

| Cu |

31.2 13.2 |

8.1 5.6 |

26 42 |

6.3 | 40 | 4.123 (0.003) |

|

| Vaccinium vitis-idaea | Ni |

91 30 |

33.1 12.7 |

36 42 |

14.4 | 117 | 4.470 (0.002) |

| Cu |

23.5 10.7 |

5.7 6.2 |

24 58 |

4.2 | 25.1 | 3.416 (0.009) |

|

| Vaccinium uliginosum | Ni |

114 23.6 |

39.6 4.3 |

35 18 |

21.5 | 30.2 | 5.960 (0.002) |

| Cu |

33.2 9.2 |

6.3 4.7 |

19 51 |

5.9 | 34.8 | 6.650 (0.001) |

|

| Empetrum hermaphroditum | Ni |

576 72 |

220 38.5 |

38 53 |

36.5 | 1060 | 12.072 (0.000) |

| Cu |

169 30 |

74 9.4 |

44 31 |

12.4 | 315 | 5.866 (0.001) |

|

| Zone | Period | Mean | SD | Min | Max | CV [%] | z (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | 1980–1999 | 1.462 | 0.414 | 0.758 | 2.125 | 28 | 4.842 (<0.001) |

| 2000–2019 | 0.685 | 0.160 | 0.402 | 1.008 | 23 | ||

| Buffer zone | 1980–1999 | 0.755 | 0.166 | 0.530 | 0.549 | 22 | –0.555 (0.58) |

| 2000–2019 | 0.758 | 0.124 | 1.069 | 0.993 | 16 | ||

| Impact zone | 1980–1999 | 0.401 | 0.133 | 0.271 | 0.703 | 33 | –4.071 (<0.001) |

| 2000–2019 | 0.611 | 0.094 | 0.391 | 0.736 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).