Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

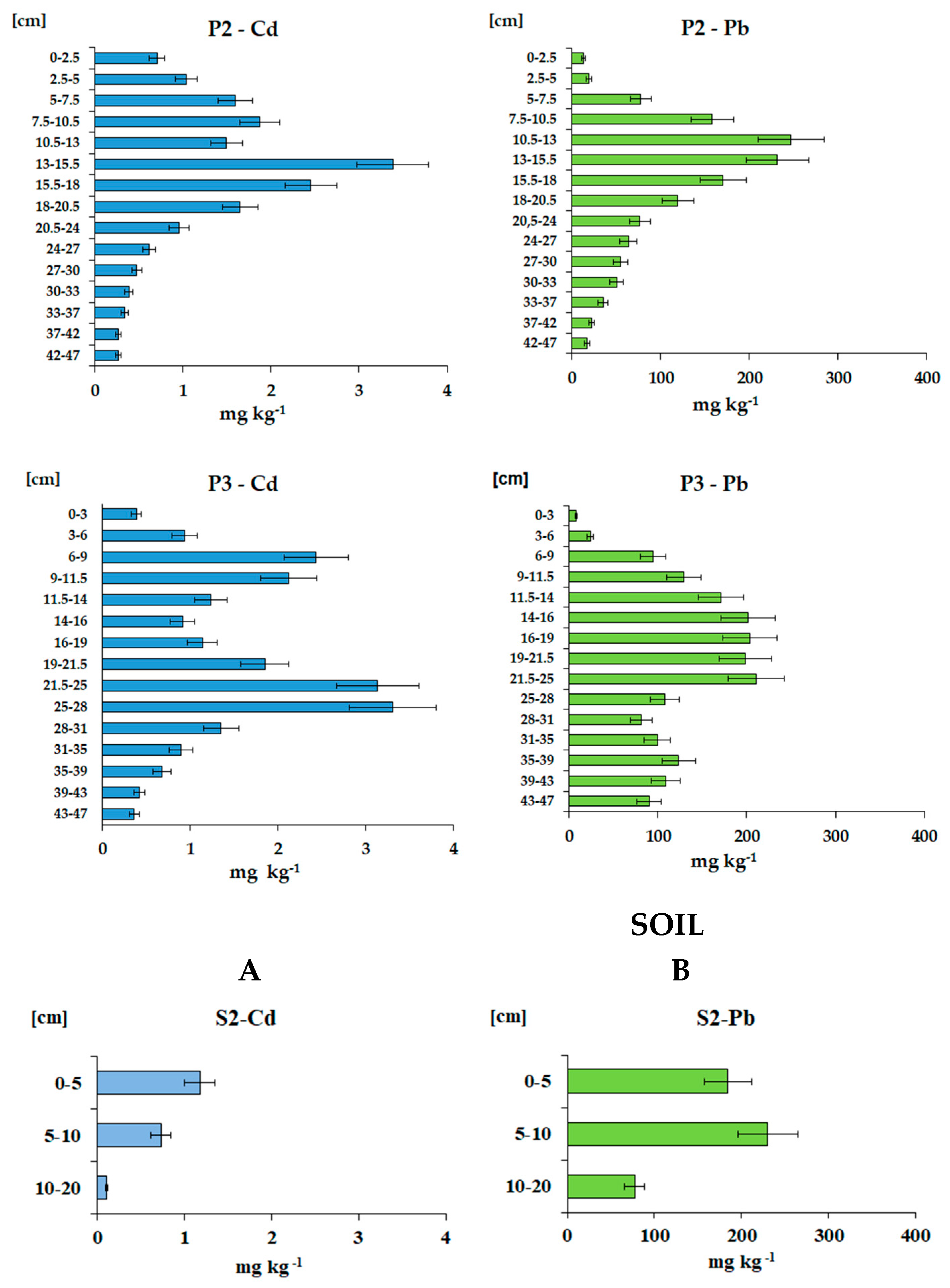

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Sample Processing and Analysis

- -

- Peat dry mass in a layer n: Mn = 103 ρdn n

- -

- Incremental loads of pollutants in a layer n: Ln= Cn Mn

- -

- Total cumulative load of a pollutant in a peat profile: ΣLn

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Soil Physico-Chemical Properties

3.2. Peat Physico-Chemical Properties

3.2.1. Peat Age

| Layer | Peat decomposition |

pH | pH | Eh | σ 1 | Moisture content |

Ash | OM |

| H2O | KCl | content | ||||||

| cm | mV | µS cm-1 | % | % | % | |||

| (A) PEAT | ||||||||

| P1 | (lat. 50.85114 N, long. 15.35466 E, 828 m), Ombrotrophic peat | |||||||

| 0-5 | H1 | 4.83±0.24 | 3.11±0.16 | 236±12 | 99±5 | 87.1±4.4 | 7.3±0.4 | 92.7±4.6 |

| 5-10 | H4 | 4.57±0.23 | 3.08±0.15 | 274±14 | 149±7 | 86.9±4.3 | 17.4±0.9 | 82.6±4.1 |

| 10-20 | H3 | 4.42±0.22 | 2.98±0.15 | 236±12 | 106±5 | 87.6±4.4 | 5.2±0.3 | 94.8±4.7 |

| 20-40 | H4 | 5.03±0.25 | 3.15±0.16 | 241±12 | 126±6 | 86.3±4.3 | 6.3±0.3 | 93.7±4.7 |

| P2 | (lat. 50.85175 N, long. 15.36155 E, 828 m), Ombrotrophic peat | |||||||

| 0-5 | H2 | 5.39±0.27 | 3.24±0.16 | 204±10 | 82±4 | 86.8±4.3 | 6.7±0.3 | 93.3±4.7 |

| 5-10 | H5 | 4.71±0.24 | 3.20±0.16 | 244±12 | 50±3 | 87.3±4.4 | 19.3±1.0 | 80.7±4.0 |

| 10-20 | H2 | 5.00±0.25 | 3.20±0.16 | 218±11 | 44±2 | 90.5±4.5 | 3.8±0.2 | 96.2±4.8 |

| 20-40 | H2 | 5.30±0.27 | 3.05±0.15 | 238±12 | 46±2 | 93.3±4.7 | 2.2±0.1 | 97.8±4.9 |

| P3 | (lat. 50.85208 N, long. 15.36105 E, 829 m), Ombrotrophic peat | |||||||

| 0-5 | H2 | 5.24±0.26 | 3.35±0.17 | 225±11 | 177±9 | 91.4±4.6 | 7.4±0.4 | 92.6±4.6 |

| 5-10 | H4 | 4.47±0.22 | 3.20±0.16 | 263±13 | 50±3 | 90.6±4.5 | 10.9±0.5 | 89.1±4.5 |

| 10-20 | H4 | 4.86±0.24 | 3.16±0.16 | 247±12 | 104±5 | 90.2±4.5 | 6.7±0.3 | 93.3±4.7 |

| 20-40 | H6 | 4.68±0.23 | 3.13±0.16 | 234±12 | 110±6 | 90.1±4.5 | 7.5±0.4 | 92.5±4.6 |

| (B) SOIL | ||||||||

| S2 | (lat. 50.81641 N, long. 15.37677 E, 868 m), Acid brown soil | |||||||

| 0-5 | 4.59 ± 0.23 | 3.20 ± 0.16 | 198 ± 20 | 168±8 | 66.4 ± 3.3 | 52.2 ± 2.6 | 47.8 ± 2.4 | |

| 5-10 | 4.50 ± 0.22 | 3.10 ± 0.15 | 235 ± 23 | 132±7 | 66.5 ± 3.3 | 42.1 ± 2.1 | 57.9 ± 2.9 | |

| 10-20 | 4.86 ± 0.24 | 3.88 ± 0.19 | 314 ± 31 | 72±4 | 28.4 ± 1.4 | 91.2 ± 4.6 | 8.8 ± 0.4 | |

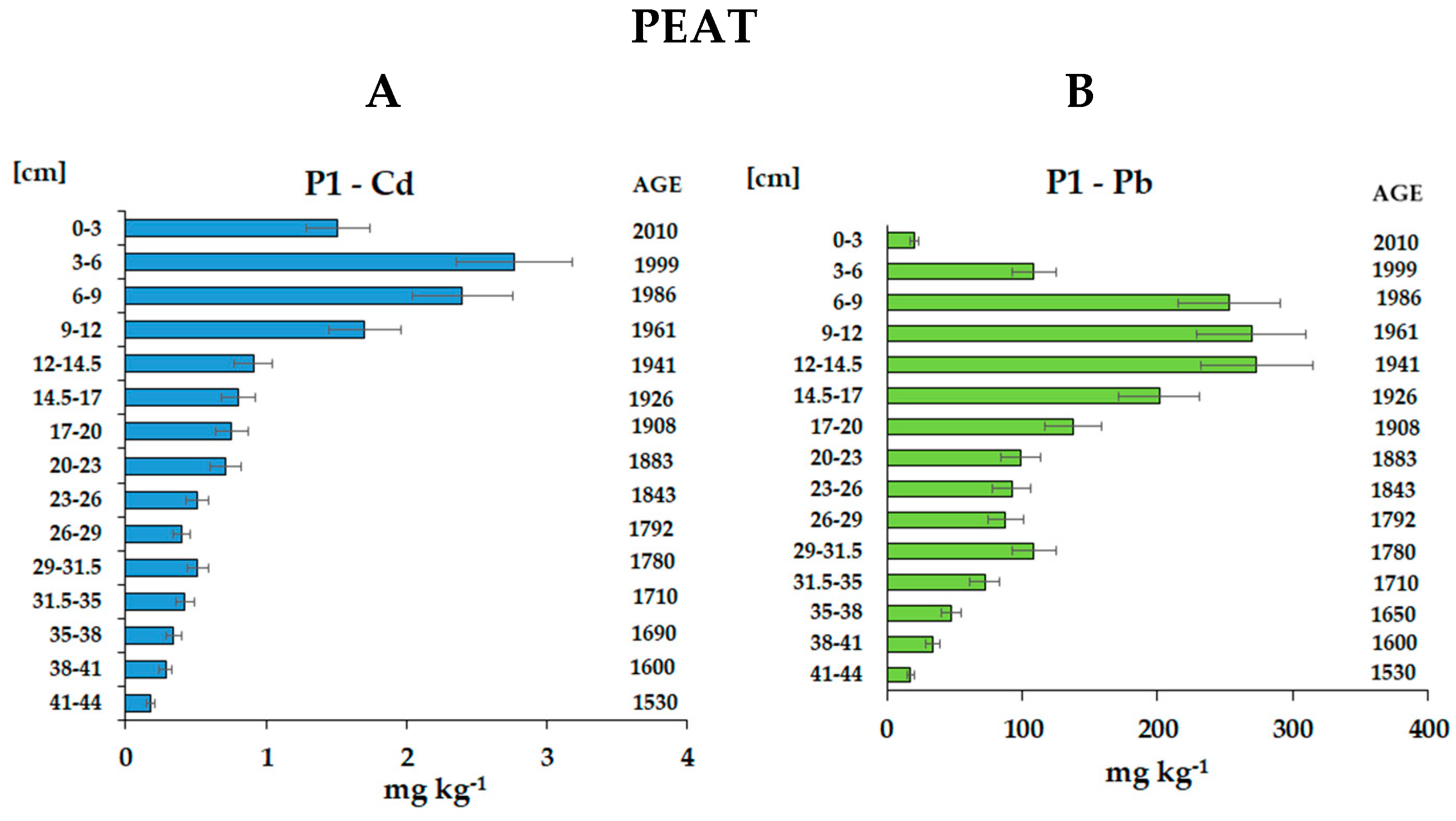

3.3. Contents and Distribution of Cd and Pb from Atmospheric Depositionin the Peat and Soil Profiles

3.3.1. Peat as a Repository of Cd and Pb Atmospheric Deposition

3.3.2. Distribution and Cumulative Loads of Cd and Pb from Atmospheric Deposition in Peat Profiles

3.4. Accumulation of Cd and Pb in Undisturbed Soil Layer

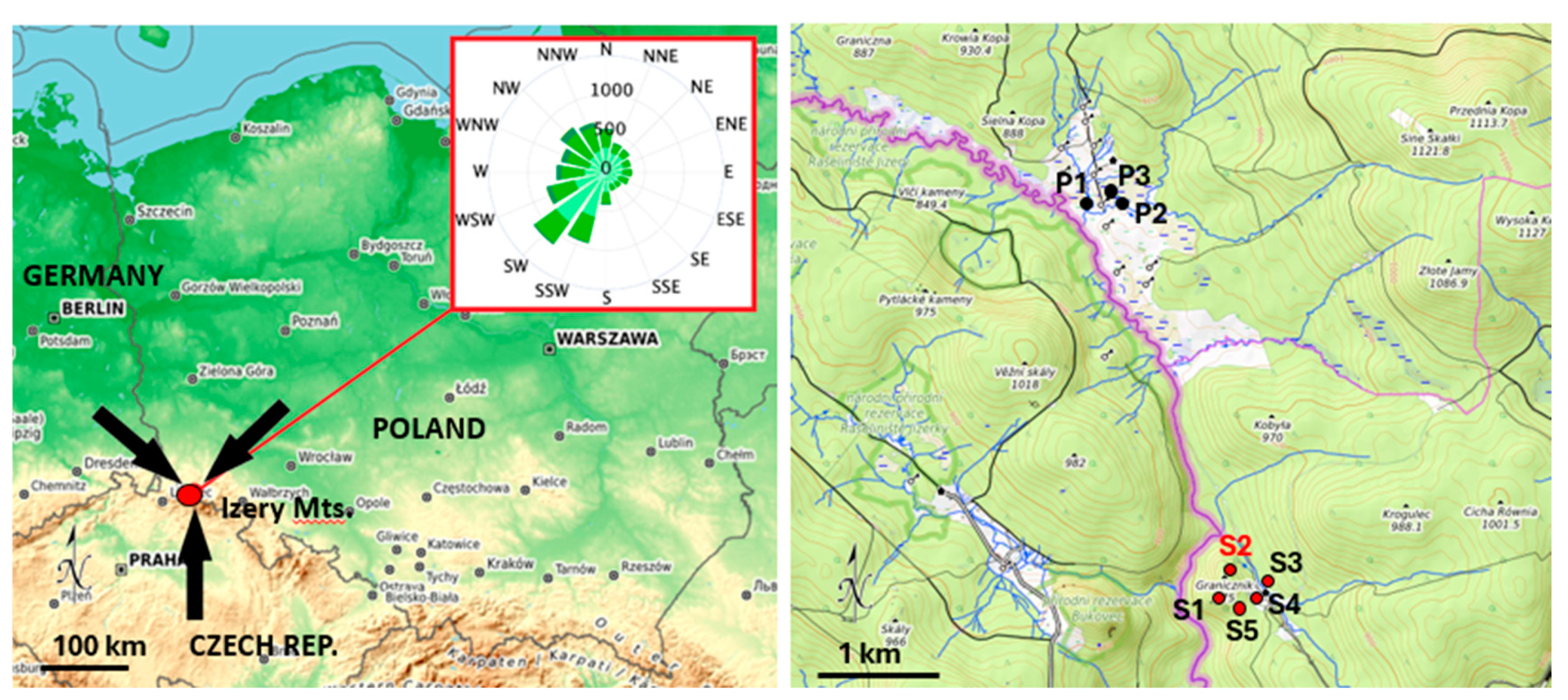

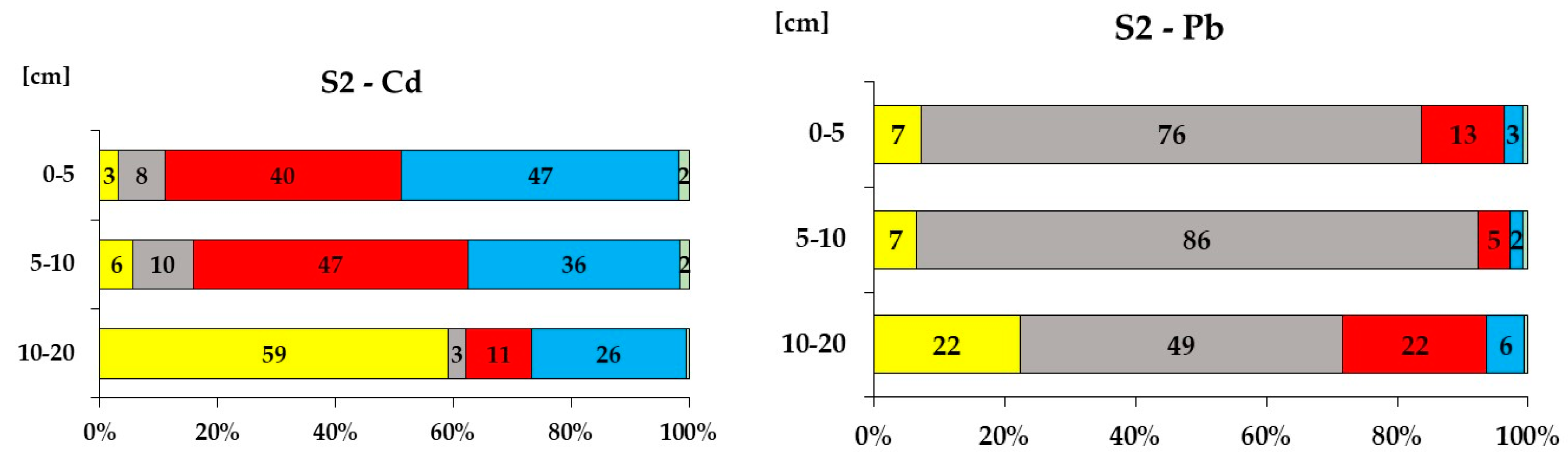

3.5. Cd and Pb Chemical Fractionation in Peat and Soil

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amundsen, C.E.; Hanssen, J.E.; Semb, A.; Steinnes, E. Long-range atmospheric transport of trace elements in southern Norway. Atmospheric Environment, Part A, General Topics, 1992, 26, 1309–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinnes, E.; Allen, R.O.; Petersen, H.M.; Rambæk, J.P.; Varskog, P. Evidence of large scale heavy-metal contamination of natural surface soils in Norway from long-range atmospheric transport. Science of The Total Environment 1997, 205, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinnes, E.; Berg, T.; Uggerud, H.T. Three decades of atmospheric metal deposition in Norway as evident from analysis of moss samples. Science of The Total Environment 2011, 412-413, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickel, S.; Hertel, A.; Pesch, R.; Schröder, W.; Steinnes, E.; Uggerud, H.T. Modelling and mapping spatio-temporal trends of heavy metal accumulation in moss and natural surface soil monitored 1990-2010 throughout Norway by multivariate generalized linear models and geostatistics. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 99, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miszczak, E.; Stefaniak, S.; Michczyński, A.; Steinnes, E.; Twarowska, I. A novel approach to peatlands as archives of total spatial pollution loads from atmospheric deposition of airborne elements complementary to EMEP data: priority pollutants (Pb, Cd, Hg). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 135776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, D.; Xue, Z.; Wu, H.; Jiang, M. Identification of anthropogenic contributions to heavy metals in wetland soils of the Karuola Glacier in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Ecological Indicators 2019, 98, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrie, L.A.; Gregor, D.; Hargrave, B.; Lake, R.; Muir, D.; Shearer, R.; Tracey, B.; Bidleman, T. Arctic contaminants: sources, occurrence and pathways. Science of The Total Environment 1992, 22, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.-L; Dang, N.-L.; Kok, Y.-Y.; Yap, K.-S.I.; Phang, S.-M.; Convey, P. Heavy metal pollution in Antarctica and its potential impacts on algae. Polar Science 2019, 20, Part–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLRTAP, 1979. Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution. Geneve, November 13th, 1979.

- EMEP, 1984. The Protocol on Long-term Financing of the Cooperative Programme for Monitoring and Evaluation of the Long-range Transmission of Air Pollutants in Europe, Geneva (Switzerland), 28 September 1984.

- EEA (European Environment Agency). European Union emission inventory report 1990-2022 - Under the UNECE convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution (Air Convention). EEA Technical Report No. 8/2024. EPA: Copenhagen, 2024. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/european-union-emissions-inventory-report-1990-2022 (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Aas, W.; Halvorsen, H. L.; Pfaffhuber, K. A. Heavy metals and POP measurements 2022. EMEP/CCC report 3/2024. Kjeller: NILU. Available online: https://projects.nilu.no/ccc/reports/EMEP_CCC-Report_3_2024_HMandPOP_09-09-2024_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Ilyin, I.; Batrakova, N.; Gusev, A.; Rozovskaya, O.; Shatalov, V.; Strizhkina, I.; Vulykh, N.; Travnikov, O. Status Report 2/2023. Heavy metals and POPs: Pollution assessment of toxic substances on regional and global scales; Meteorological Synthesizing Centre – East: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2023; Available online: http://msceast.org/reports/2_2023.pdf.

- Shotyk, W.; Blaser, P.; Grünig, A.; Cheburkin, A.K. A new approach for quantifying cumulative, anthropogenic, atmospheric lead deposition using peat cores from bogs: Pb in eight Swiss peat bog profiles. Sci.Total Environ. 2000, 249, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Daoushy, F.; Tolonen, K. Lead-210 and heavy metal contents in dated ombrotrophic peat hummocks from Finland. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. 1984, 223, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, N.R.; Eisenreich, S.J.; Grigal, D.F.; Schurr, K.T. Mobility and diagenesis of Pb and 210Pb in peat. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1990, 54, 3329–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiss, J.; Byers, C.; Clover, D.; D’Amore, D.; Love, A.; Menzies, M.A.; Powell, J.; Todd, W. Transport of lead and diesel fuel through a peat soil near Juneau, AK: a pilot study. J. Contamin. Hydrol. 2004, 74, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Roux, G. Fate of Natural and Anthropogenic Particles in Peat Bogs. Inaudgural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde, Ruprecht-Karls-Universitãt, Heidelberg (Germany). 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, M.; Erel, Y.; Zemanova, L.; Bottrell, S.H.; Adamova, M. A comparison of lead pollution record in Sphagnum peat with known historical Pb emission rates in the British Isles and in the Czech Republic. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 8997–9006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.; Pacherova, P. Mobility of trace metals in pore waters of two Central European peat bogs. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 394, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smieja-Król, B.; Fiałkiewicz-Kozieł, B. , Sikorski J.; Palowski B. Heavy metal behaviour in peat - a mineralogical perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 5924–5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, S.V.; Tolu, J.; Bindler, R. Downwash of atmospherically deposited trace metals in peat and the influence of rainfall intensity: An experimental test. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 506-507, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremiason, J.D.; Baumann, E.I.; Sebestyen, S.D.; Agther, A.M.; Seelen, E.A.; Carlson-Stehlin, B.J.; Funke, M.M.; Cotner, J.B. Contemporary mobilization of legacy Pb stores by DOM in a boreal peatland. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 3375–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, N.A.; Sebestyen, S.; Oleheiser, K.C. Variation in peatland porewater chemistry over time a space along a bog to fen gradient. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 697, 134252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vleeschouwer, F.; Fagel, N.; Cheburkin, A.; Pazdur, A.; Sikorski, J.; Mattielli, N.; Renson, V.; Fiałkiewicz, B.; Piotrowska, N.; Le Roux, G. Anthropogenic impacts in North Poland over the last 1300 years - A record of Pb, Zn, Cu, Ni and S in an ombrotrophic peat bog. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 5674–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vleeschouwer, F.; Baron, S.; Cloy, J.M.; Enrico, M.; Ettler, V.; Fagel, N.; Kylander, M. (….); Le Roux, G. Comment on: “A novel approach to peatlands as archives of total cumulative spatial pollution loads from atmospheric deposition of airborne elements complementary to EMEP data: priority pollutants (Pb, Cd, Hg)” by Ewa Miszczak, Sebastian Stefaniak, Adam Michczyński, Eiliv Steinnes and Irena Twardowska. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 138699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twardowska, I.; Steinnes, E.; Miszczak, E. Reply to the comments on “A novel approach to peatlands as archives of total cumulative spatial pollution loads from atmospheric deposition of airborne elements complementary to EMEP data: Priority pollutants (Pb, Cd, Hg)” by V. De Vleeschouwer et al. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 139153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, J.; Berger, F.; Ciechanowicz-Kusztal, R.; Jodłowska-Opyd, G.; Kallweit, D.; Keder, J.; Kulaszka, W.; Novák, J. Common Report on Air Quality in the Black Triangle Region 2002, ČHMU, WIOŚ, LfUG, UBA. 2003. Available online: www.env.cz (accessed on 25 September 2024). www.chmi.cz; www.umweltbundesamt.de; www.umwelt.sachsen.de/lfug; www.jgora.pios.gov.pl/wwm/index.htm.

- Migoń, P. Geomorphological evolution of the Polish part of the Sudetes - A review of results of recent research. Geografie-Sbornik ČGS, 2003, 108, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glina, B.; Bogacz, A. Concentration and pools of trace elements in organic soils in the Izera Mountains. J. Elem. 2013, 18, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.meteoblue.

- Popowski, B. Results of a palynological analysis of peat sediments from Izerskie Bagno (Izerskie Mts). Acta Botanica Silesiana 2005, 2, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Matula, J.; Wojtun, B.; Tomaszewska, K.; Zolnierz, L. Peatlands of Polish part of Karkonosze and Izera Mountains. Ann. Silesiae 1997, 27, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Brogowski, Z.; Borzyszkowski, J.; Gworek, B.; Ostrowska, A.; Porębska, G.; Sienkiewicz, J. Charakterystyka gleb wylesionych obszarów Gór Izerskich (Soil characteristics of deforested areas in the Izera Mountains). Roczniki Gleboznawcze XLVIII (in Polish). 1997, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Szopka, K.; Karczewska, A.; Kabała, C. Spatial distribution of lead in the surface layers of mountain forest soils, an example from Karkonosze National Park, Poland. Geoderma 2013, 192, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 18400-100:2017; Soil quality, Sampling, Part 100: Guidance on the selection of sampling standards (Edition 1, 2017).

- ISO 18400-101:2017; Soil quality, Sampling, Part 101: Soil quality, Sampling, Part 101: Framework for the preparation and application of a sampling plan (Edition 1, 2017).

- ISO 18400-102:2017; Soil quality, Sampling, Part 102: Soil quality, Sampling, Part 102: Selection and application of sampling techniques (Edition 1, 2017).

- ISO 18400-103:2017; Soil quality, Sampling, Part 103: Soil quality, Sampling, Part 103: Safety (Edition 1, 2017).

- ISO 18400-104:2018; Soil quality, Sampling, Part 104: Soil quality, Sampling, Part 104: Strategies (Edition 1, 2018).

- ISO 18400-105:2017; Soil quality, Sampling, Part 105: Soil quality, Sampling, Part 105: Packaging, transport, storage and preservation of samples (Edition 1, 2017).

- ISO 18400-106:2017; Soil quality, Sampling, Part 106: Soil quality, Sampling, Part 106: Quality control and quality assurance (Edition 1, 2017).

- ISO 23909:2008; Soil quality — Preparation of laboratory samples from large samples, Published (Edition 1, 2008).

- ISO 11464:2006; Soil quality — Pretreatment of samples for physico-chemical analysis, Published (Edition 2, 2006).

- ASTM D2976 -15; Standard Test Method for pH of Peat Materials. Book of Standards Volume 04.08.

- ASTM D2216 - 19; Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Determination of Water (Moisture) Content of Soil and Rock by Mass.| Developed by Subcommittee: D18.03. Book of Standards Volume: 04.08.

- ASTM D2974 – 14; Standard Test Methods for Moisture, Ash and Organic Matter in Peat and Other Organic Soils. Book of Standards Volume 04.08’.

- ASTM D4531-86; International. Standard Test Methods for Bulk Density of Peat and Peat products. Designation: D 4531-86 (Reapproved 2008).

- ISO 10390:2021; Soil, treated biowaste and sludge, Determination of pH, Published (Edition 3, 2021).

- Bleam, W. Soil and Environmental Chemistry, 2nd edition; Elsevier Inc.; Academic Pres, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronk, R.C.; Lee, S. Recent and planned developments of the Program Ox Cal. Radiocarbon 2013, 55, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazdur, A.; Fogtman, M.; Michczyński, A.; Pawlyta, J. Precision of 14C dating in Gliwice radiocarbon laboratory. FIRI Programme. Geochronometria 2003, 22, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tudyka, K.; Pazdur, A.; Theodórsson, P.; Michczyński, A.; Pawlyta, J. The application of ICELS system for radiocarbon dating. Radiocarbon 2010, 52, 1661–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, N.; Blaauw, M.; Mauquoy, D.; Chambers, F.M. 2010/2011. Constructing deposition chronologies for peat deposits using radiocarbon dating. Mires Peat 2010/2011, 7(Art. 10), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Steinnes, E.; Rühling, Å.; Lippo, H.; Mäkinen, A. Reference materials for large-scale metal deposition surveys. Accreditation and Quality Assurance 1997, 2, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ure, A.M.; Quevauviller, P.; Muntau, H.; Griepink, B. Speciation of heavy metals in soils and sediments. An account of the improvement and harmonization of extraction techniques undertaken under the auspices of the BCR of the Commission of the European Communities. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2006, 51, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauret, G.; López-Sánchez, J.F.; Sahuquillo, A.; Rubio, R.; Davidson, C.M.; Ure, A.; Quevauviller, P. J. Improvement of the BCR three step sequential extraction procedure prior to the certification of new sediment and soil reference materials. J. Environ. Monit. 1999, 1, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemberyová, M.; Barteková, J.; Hagarová, I. The utilization of modified BCR three-step sequential extraction procedure for the fractionation of Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb and Zn in soil reference materials of different origins. Talanta 2006, 70, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, M.; Boková, V.; Heltai, G.; Flórián, K.; Fekete, I. Study of application of BCR sequential extraction procedure for fractionation of heavy metal content of soils, sediments, and gravitation dusts. Toxicol. Environ. Chem 2010, 92, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. In International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kabata-Pendias, A. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2011; p. 266. [Google Scholar]

- Håkanson, L. An ecological risk index for Aquatic pollution control. A Sedimentological Approach. Water Research 1980, 14, 975–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Soil Quality Indicators: pH. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rausch, N.; Ukonmaanaho, L.; Nieminen, T.; Krachler, M.; Shotyk, W. Porewater evidence of metal (Cu, Ni, Co, Zn, Cd) mobilization in an acidic, ombrotrophic bog impacted by a smelter, Harjavalta, Finland and comparison with reference sites. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 8207–8213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, N.; Nieminen, T.; Ukonmaanaho, L.; Le Roux, G.; Krachler, M.; Cheburkin, A.K.; Bonani, G.; Shotyk, W. Comparison of atmospheric deposition of copper, nickel, cobalt, zinc and cadmium recorded by Finnish peat cores with monitoring data and emission records. Environ. Sci.Technol. 2005, 39, 5989–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopáček, J.; Veselý, J. Sulfur and nitrogen emissions in the Czech Republic and Slovakia from 1850 till 2000. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 2179–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulski, S.Z. Metal ore potential of the parent magma of granite –the Karkonosze massif example. In Granitoids in Poland; AM Monograph No. 1, PIG and UW: Warsaw (Poland); pp. 123-125–125.

- Mochnacka, K.; Oberc-Dziedzic, T.; Mayer, W.; Pieczka, A.; Góralski, M. Occurrence of sulphides in Sowia Dolina near Karpacz (SW Poland) – an example of ore mineralization in the contact aureole of the Karkonosze granite. Mineralogia Polonica 2007, 38, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Centre for Emissions Management (KOBiZE) at the Institute of Environmental Protection – National Research Institute. Poland’s Informative Inventory Report 2024, Air pollutant emissions in Poland 1990 – 2022. Submission under the UN ECE Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution and Directive (EU) 2016/2284. Ministry of Climate and Environment, Warsaw 2024.

- Bódog, I.; Csikós-Hartyányi, Z.; Hlavay, J. Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of elements in fly ash samples. Microchemical Journal 1996, 54, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, D.M.; Rucandio, M.I. Sequenial extractions for determination of cadmium distribution in coal fly ash, soil and sediment samples. Anal. Chem. Acta 1999, 401, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Duan, Y.; Lu, J.; Gupta, R.; Pudasainee, D.; Liu, S.; Liu, M.; Lu, J. Chemical speciation and leaching characteristics of hazardous trace elements in coal and fly ash from coal-fired power plants. Fuel 2018, 232, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, W.-P. Speciation analysis of Hg, As, Pb, Cd, and Cr in fly ash at different ESP’s hoppers. Fuel 2020, 280, 118688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US-EPA. SW-846 Test Method 1313: Liquid-Solid Partitioning as a Function of Extract pH Using a Parallel Batch Extraction Procedure (Last updated on May 9, 2024).

- Stefaniak, S.; Kmiecik, E.; Miszczak, E.; Szczepańska-Plewa, J. Leaching behavior of fly ash from co-firing of coal with alternative off gas fuel in powerplant boilers. Appl. Geochem. 2018, 93, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccone, C.; Miano, T.M.; Shotyk, W. Qualitative comparison between raw peat and related humic acids in an ombrotrophic bog profile. Org. Geochem. 2007, 38, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccone, C.; Cocozza, C.; Cheburkin, A.K.; Shotyk, W.; Miani, T.M. Distribution of As, Cr, Ni, Ti, and Zr between peat and its humic fraction along an undisturbed ombrotrophic bog profile (NW Switzerland). Appl. Geochem. 2008, 23, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, A.R.; Ohde, S.; Shinjo, R.; Ganmanee, M.; Cohen, M.D. Geochemical fractions and modeling adsorption of heavy metals into contaminated river sediments in Japan and Thailand determined by sequential leaching technique using ICP-MS. Arab. J. Chem 2019, 12, 780–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.P.P.; Baldock, J.A. The link between peat hydrology and decomposition: Beyond von Post. J. Hydrol. 2013, 479, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezanezhad, F.; Price, J.S.; Quinton, W.L.; Lennartz, B.; Milojevic, T.; Van Cappelen, P. Structure of peat soils and implications for water storage, flow and solute transport: a review update for geochemists. Chem. Geol. 2016, 429, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubev, V.; Whittington, P. Effect of volume change on the unsaturated hydraulic conductivity of Sphagnum moss. J. Hydrol. 2018, 559, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabała, C. Pierwiastki śladowe w glebach Gór Izerskich. Zesz. Nauk. Akademii Rolniczej we Wrocławiu (in Polish). 1998, 347, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kabała, C.; Szerszeń, L. Profile distribution of lead, zinc and copper in Dystric Cambisols developed from granite and gneiss of the Sudetes Mountains, Poland. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2002, 138, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Unit | A horizon (n=5) Topsoil | B horizon (n=5) Subsoil | C horizon (n=5) backround |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Mean±SD | 5.15±0.66 | 4.78±0.64 | 5.53±0.77 | |

| Min.-Max. | 4.43-6.04 | 4.27-5.75 | 4.72-6.34 | ||

| ρ | Mean±SD | µS cm-1 | 162.4±5.9 | 125.5±6.6 | 78.33±12.9 |

| Min.-Max | 156.6-168.5 | 118.7-131.9 | 69.5-93.1 | ||

| Eh | Mean±SD | mV | 286.5±42.3 | 291.5±50.2 | 332.1±24.9 |

| Min.-Max. | 237.8-313.1 | 235.5-332.5 | 314.0-360.5 | ||

| Water content | Mean±SD | % | 58.2±8.7 | 49.4±16.2 | 23.0±5.5 |

| Min.-Max | 49.1-66.5 | 34.2-66.6 | 17.4-28.4 | ||

| Ash content | Mean±SD | % | 58.6±22.3 | 64.5±22.9 | 93.5±2.5 |

| Min.-Max. | 40.2-83.4 | 42.1-88.0 | 91.2-96.2 | ||

| OM | Mean±SD | % | 41.4±22.3 | 35.5±22.9 | 0.70±0.30 |

| Min.-Max. | 16.6-59.8 | 12.0-57.9 | 0.30-1.10 | ||

| Cd | Mean±SD | mg kg-1 | 0.77±0.30 | 0.43±0.18 | 0.12±0.06 |

| Min.-Max. | 0.46-1.18 | 0.12-0.99 | 0.02-0.19 | ||

| Pb | Mean±SD | mg kg-1 | 128.61±40.03 | 75.20±52.30 | 27.00±25.28 |

| Min.-Max. | 64.42-184.60 | 19.25-153.70 | 14.40-68.87 | ||

| CF | Cd | 7.7 (very high) | 4.3 (considerable) | ||

| CF | Pb | 4.5 (considerable) | 2.8 (moderate) |

| Layer, cm |

Age | Bulk density g cm-3 |

Concentration Cn mg kg-1 |

Incremental loads Ln mg m-2 |

Total loads ∑Ln mg m-2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd | Pb | Cd | Pb | Cd | Pb | |||

| (A) Peat | ||||||||

| P1 | (lat. 50.85114 N, long. 15.35466 E, 828 m) | |||||||

| 0-3 | 2010 | 0.067 | 1.51 | 20.8 | 3.04 | 41.8 | 3.04 | 41.8 |

| 3-6 | 1999 | 0.096 | 2.77 | 108.8 | 7.97 | 313.4 | 11.00 | 355.2 |

| 6-9 | 1986 | 0.115 | 2.40 | 253.0 | 8.27 | 872.8 | 19.28 | 1 228 |

| 9-12 | 1961 | 0.119 | 1.70 | 269.4 | 6.08 | 961.7 | 25.35 | 2 190 |

| 12-14.5 | 1941 | 0.099 | 0.91 | 273.2 | 2.25 | 676.2 | 27.61 | 2 866 |

| 14.5-17 | 1926 | 0.097 | 0.81 | 201.2 | 1.96 | 487.9 | 29.56 | 3 354 |

| 17-20 | 1908 | 0.109 | 0.75 | 137.6 | 2.47 | 449.8 | 32.03 | 3 804 |

| 20-23 | 1883 | 0.097 | 0.71 | 98.9 | 2.07 | 287.8 | 34.10 | 4 091 |

| 23-26 | 1843 | 0.119 | 0.51 | 92.4 | 1.82 | 329.7 | 35.93 | 4 421 |

| 26-29 | 1792 | 0.113 | 0.40 | 87.5 | 1.34 | 296.5 | 37.27 | 4 718 |

| 29-31.5 | 1780 | 0.132 | 0.51 | 108.9 | 1.69 | 359.3 | 38.96 | 5 077 |

| 31.5-35 | 1710 | 0.105 | 0.42 | 72.4 | 1.55 | 266.2 | 40.51 | 5 343 |

| 35-38 | 1690 | 0.090 | 0.34 | 47.9 | 0.93 | 129.4 | 41.44 | 5 473 |

| 38-41 | 1600 | 0.080 | 0.28 | 34.1 | 0.68 | 82.0 | 42.12 | 5 554 |

| 41-44 | 1530 | 0.090 | 0.18 | 17.7 | 0.48 | 47.8 | 42.60 | 5 602 |

| P2 | (lat. 50.85175 N, long. 15.36155 E, 828 m) | |||||||

| 0-2.5 | 0.065 | 0.71 | 13.3 | 1.15 | 21.6 | 1.15 | 21.6 | |

| 2.5-5 | 0.085 | 1.04 | 19.6 | 2.20 | 41.6 | 3.35 | 63.2 | |

| 5-7.5 | 0.090 | 1.59 | 77.8 | 3.59 | 175.1 | 6.94 | 238.3 | |

| 7.5-10.5 | 0.136 | 1.87 | 158.2 | 7.62 | 645.0 | 14.56 | 883.3 | |

| 10.5-13 | 0.137 | 1.50 | 246.9 | 5.13 | 845.7 | 19.68 | 1 729 | |

| 13-15.5 | 0.134 | 3.38 | 231.8 | 11.29 | 773.9 | 30.97 | 2 503 | |

| 15.5-18 | 0.121 | 2.45 | 170.7 | 7.42 | 516.5 | 38.39 | 3 019 | |

| 18-20.5 | 0.101 | 1.65 | 119.7 | 4.18 | 303.3 | 42.57 | 3 323 | |

| 20.5-24 | 0.108 | 0.95 | 76.9 | 3.59 | 290.1 | 46.17 | 3 613 | |

| 24-27 | 0.077 | 0.62 | 63.8 | 1.42 | 146.8 | 47.59 | 3 760 | |

| 27-30 | 0.074 | 0.47 | 55.1 | 1.06 | 123.0 | 48.65 | 3 883 | |

| 30-33 | 0.073 | 0.39 | 50.8 | 0.85 | 111.7 | 49.50 | 3 994 | |

| 33-37 | 0.062 | 0.34 | 35.4 | 0.84 | 88.2 | 50.34 | 4 083 | |

| 37-42 | 0.061 | 0.27 | 22.3 | 0.82 | 68.5 | 51.16 | 4 151 | |

| 42-47 | 0.062 | 0.27 | 17.3 | 0.83 | 53.8 | 51.99 | 4 205 | |

| P3 | (lat. 50.85208 N, long. 15.36105 E, 829 m) | |||||||

| 0-3 | 0.060 | 0.39 | 8.6 | 0.70 | 15.4 | 0.70 | 15.4 | |

| 3-6 | 0.066 | 0.94 | 24.3 | 1.86 | 48.1 | 2.56 | 63.5 | |

| 6-9 | 0.071 | 2.44 | 94.9 | 5.16 | 200.9 | 7.72 | 264.4 | |

| 9-11.5 | 0.072 | 2.12 | 129.4 | 3.85 | 234.4 | 11.57 | 498.8 | |

| 11.5-14 | 0.093 | 1.24 | 171.4 | 2.88 | 398.3 | 14.45 | 897.1 | |

| 14-16 | 0.097 | 0.91 | 201.7 | 1.77 | 391.3 | 16.22 | 1288 | |

| 16-19 | 0.080 | 1.14 | 203.4 | 2.73 | 488.3 | 18.96 | 1777 | |

| 19-21.5 | 0.101 | 1.85 | 198.6 | 4.68 | 501.4 | 23.63 | 2278 | |

| 21.5-25 | 0.106 | 3.14 | 211.2 | 11.64 | 783.6 | 35.27 | 3062 | |

| 25-28 | 0.090 | 3.31 | 108.5 | 8.94 | 292.9 | 44.21 | 3355 | |

| 28-31 | 0.091 | 1.35 | 81.2 | 3.69 | 221.5 | 47.90 | 3576 | |

| 31-35 | 0.111 | 0.90 | 99.5 | 4.00 | 442.0 | 51.90 | 4018 | |

| 35-39 | 0.116 | 0.68 | 123.7 | 3.14 | 573.5 | 55.04 | 4592 | |

| 39-43 | 0.086 | 0.42 | 109.4 | 1.46 | 377.8 | 56.50 | 4970 | |

| 43-47 | 0.077 | 0.36 | 90.3 | 1.12 | 276.5 | 57.62 | 5246 | |

| Mean | 50.74±7.59 | 5018±726 | ||||||

| (B) Soil | ||||||||

| S2 | (lat. 50.81641 N, long. 15.37677 E, 868 m) | |||||||

| 0-5 | 0.342 | 1.18 | 184.6 | 20.18 | 3157 | 20.18 | 3157 | |

| 5-10 | 0.201 | 0.73 | 230.1 | 7.35 | 2313 | 27.52 | 5469 | |

| 10-20 | 0.730 | 0.11 | 77.3 | 7.88 | 5641 | 35.41 | 11110 | |

| Profile | Cd | Pb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layer cm |

Mobile fractions (F0+FI+FII) [%] | Mobilizable fraction (FIII) [%] |

Immobile fraction (FIV) [%] |

Mobile fractions (F0+FI+FII) [%] | Mobilizable fraction (FIII) [%] |

Immobile fraction (FIV) [%] |

|

| (A) Peat | |||||||

| P1 | (lat. 50.85114 N, long. 15.35466 E, 828 m) | ||||||

| 0-5 | 85.9 | 13.9 | 0.2 | 14.1 | 84.6 | 1.3 | |

| 5-10 | 92.1 | 6.9 | 1.0 | 16.9 | 81.2 | 2.0 | |

| 10-20 | 97.2 | 2.5 | 0.4 | 27.2 | 71.0 | 1.8 | |

| 20-40 | 96.1 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 29.1 | 66.8 | 4.1 | |

| P2 | (lat. 50.85175 N, long. 15.36155 E, 828 m) | ||||||

| 0-5 | 86.6 | 13.1 | 0.3 | 15.2 | 82.8 | 2.0 | |

| 5-10 | 89.5 | 9.6 | 0.9 | 20.2 | 76.4 | 3.4 | |

| 10-20 | 86.0 | 13.7 | 0.3 | 22.3 | 75.4 | 2.3 | |

| 20-40 | 91.5 | 7.5 | 1.0 | 26.4 | 70.5 | 3.1 | |

| P3 | (lat. 50.85208 N, long. 15.36105 E, 829 m) | ||||||

| 0-5 | 86.9 | 12.6 | 0.5 | 12.4 | 85.8 | 1.7 | |

| 5-10 | 79.9 | 17.5 | 2.6 | 16.7 | 79.3 | 4.0 | |

| 10-20 | 72.1 | 26.8 | 1.1 | 15.8 | 82.2 | 2.0 | |

| 20-40 | 75.9 | 22.9 | 1.1 | 14.9 | 82.7 | 2.4 | |

| (B) Soil | |||||||

| S2 | (lat. 50.81641 N, long. 15.37677 E, 868 m) | ||||||

| 0-5 | 89.0 | 7.9 | 3.2 | 16.2 | 76.5 | 7.3 | |

| 5-10 | 84.2 | 10.2 | 5.6 | 7.7 | 85.8 | 6.5 | |

| 10-20 | 37.8 | 3.2 | 59.1 | 28.3 | 49.4 | 22.3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).