Submitted:

15 June 2023

Posted:

15 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Carbon Allotropes Within Electrochemical Aptasensing

3. Inorganic Metal Oxide-Based Semiconductors

4. Other Inorganic Semiconductors (PbS, CdS, ZnS, CdT)

5. Organic Semiconductors

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

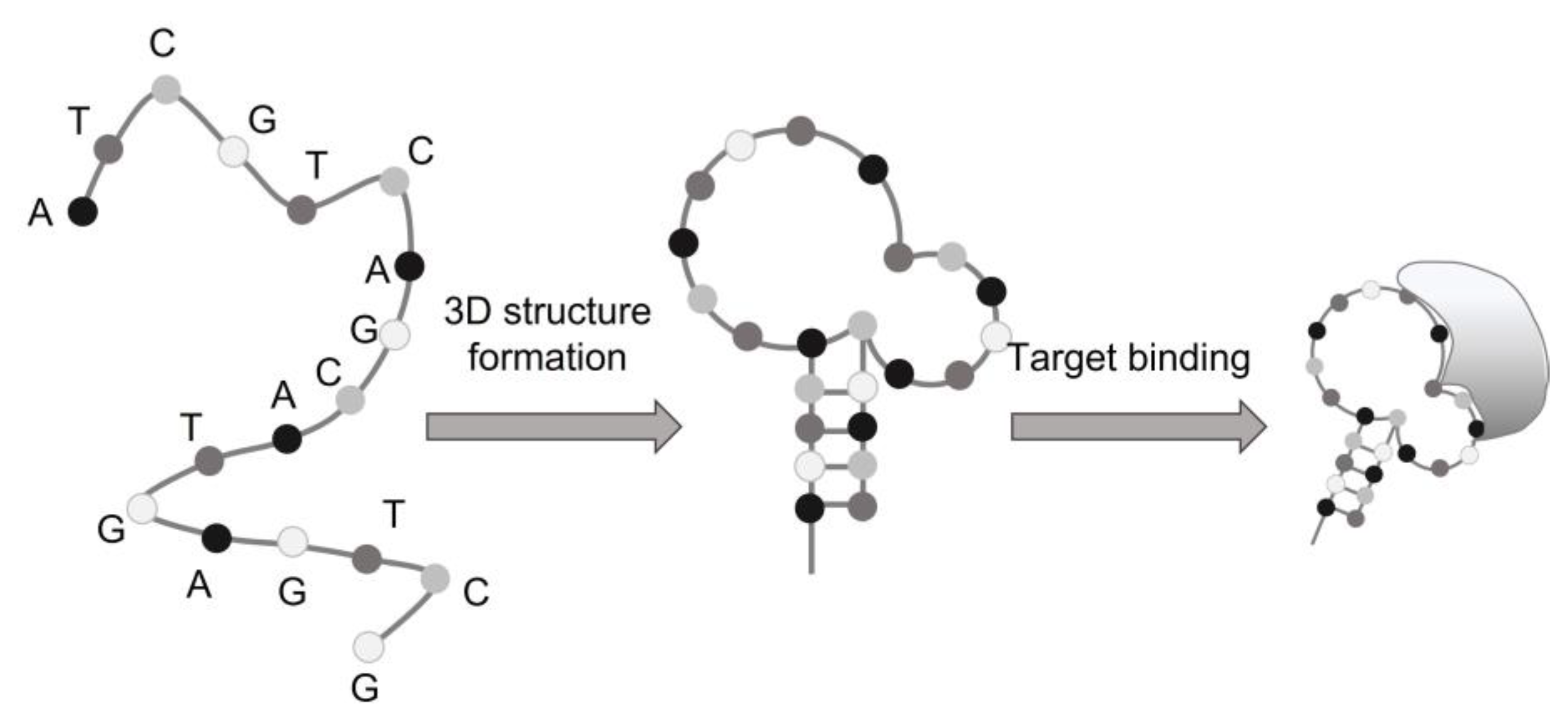

- Zhuo, Z.; Yu, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Lu, A.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, B. Recent advances in SELEX technology and aptamer applications in biomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerk, C.; Gold, L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 1990, 249, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, A.D.; Szostak, J.W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshavsky-Graham, S.; Heuer, C.; Jiang, X.; Segal, E. Aptasensors versus immunosensors-Which will prevail? Eng. Life Sci. 2022, 22, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.; Zuo, X.; Yang, R.; Xia, F.; Plaxco, K.W.; White, R.J. Comparing the properties of electrochemical-based DNA sensors employing different redox tags. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 9109–9113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catanante, G.; Mishra, R.K.; Hayat, A.; Marty, J.-L. Sensitive analytical performance of folding based biosensor using methylene blue tagged aptamers. Talanta 2016, 153, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Li, H.; Xu, L.; Deng, Z.; Han, W.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zu, Y. Oligonucleotide aptamer-mediated precision therapy of hematological malignancies. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 13, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernat, V.; Disney, M.D. RNA structures as mediators of neurological diseases and as drug targets. Neuron 2015, 87, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalonga, A.; Mayol, B.; Villalonga, R.; Vilela, D. Electrochemical aptasensors for clinical diagnosis. A review of the last five years. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2022, 369, 132318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikebukuro, K.; Kiyohara, C.; Sode, K. Electrochemical detection of protein using a double aptamer sandwich. Anal. Lett. 2004, 37, 2901–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hianik, T.; Wang, J. Electrochemical aptasensors – Recent achievements and perspectives. Electroanalysis 2009, 21, 1223–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Ellatief, R.; Abd-Ellatief, M.R. Electrochemical aptasensors: Current status and future perspectives. Diagnostics 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, A. J.; Faulkner, L. R.; White, H. S. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications, 3rd ed.; Wiley, USA, 2022; ISBN 9781119334071. [Google Scholar]

- Girault, H.H. Analytical and Physical Electrochemistry, 1st ed.; EPFL Press: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2004; p. 315. [Google Scholar]

- Renedo, O.D.; Alonso-Lomillo, M.A.; Martínez, M.J.A. Recent developments in the field of screen-printed electrodes and their related applications. Talanta 2007, 73, 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Miranda Ferrari, A.; Rowley-Neale, S.J.; Banks, C.E. Screen-printed electrodes: Transitioning the laboratory in-to-the field. Talanta Open 2021, 3, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evtugyn, G.; Porfireva, A.; Shamagsumova, R.; Hianik, T. Advances in electrochemical aptasensors based on carbon nanomaterials. Chemosensors 2020, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertel, L.; Miranda, D.A.; García-Martín, J.M. Nanostructured titanium dioxide surfaces for electrochemical biosensing. Sensors 2021, 21, 6167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetti, N.P.; Bukkitgar, S.D.; Reddy, K.R.; Reddy, C.V.; Aminabhavi, T.M. ZnO-based nanostructured electrodes for electrochemical sensors and biosensors in biomedical applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 141, 111417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukkitgar, S.D.; Kumar, S.; Pratibha; Singh, S. ; Singh, V.; Raghava Reddy, K.; Sadhu, V.; Bagihalli, G.B.; Shetti, N.P.; Venkata Reddy, C.; Ravindranadh, K.; Naveen, S. Functional nanostructured metal oxides and its hybrid electrodes – Recent advancements in electrochemical biosensing applications. Microchem. J. 2020, 159, 105522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Lin, X.; Jiang, N.; Huang, M. Carbon-doped WO3 electrochemical aptasensor based on Box-Behnken strategy for highly-sensitive detection of tetracycline. Food Chem. 2022, 367, 130564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, Z.; Ai, L.; Zhou, S.; Fan, H.; Ai, S. Signal-off photoelectrochemical aptasensor for S. aureus detection based on graphite-like carbon nitride decorated with nickel oxide. Electroanalysis 2022, 34, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samie, H.A.; Arvand, M. Label-free electrochemical aptasensor for progesterone detection in biological fluids. Bioelectrochemistry 2020, 133, 107489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, S.; Srivastava, P.; Maheshwari, S.N.; Sundar, S.; Prakash, R. Nano-structured nickel oxide based DNA biosensor for detection of visceral leishmaniasis (Kala-azar). Analyst 2011, 136, 2845–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgakilas, V.; Perman, J.A.; Tucek, J.; Zboril, R. Broad family of carbon nanoallotropes: classification, chemistry, and applications of fullerenes, carbon dots, nanotubes, graphene, nanodiamonds, and combined superstructures. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 4744–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Kumar, P.; Park, D.-S.; Shim, Y.-B. Electrochemical sensors based on organic conjugated polymers. Sensors 2008, 8, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.; Fidanovski, K.; Lauto, A.; Mawad, D. All-organic semiconductors for electrochemical biosensors: An overview of recent progress in material design. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Yoo, H.; Lee, E.K. New opportunities for organic semiconducting polymers in biomedical applications. Polymers. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, A. The era of carbon allotropes. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ebrahimi, A.; Li, J.; Cui, Q. Fullerene-biomolecule conjugates and their biomedicinal applications. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2014, 9, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

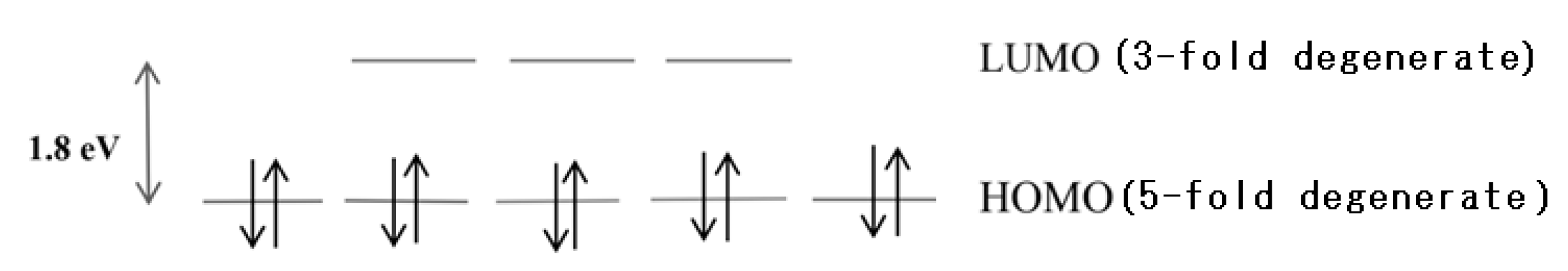

- Pilehvar, S.; De Wael, K. Recent advances in electrochemical biosensors based on fullerene-C60 nano-structured platforms. Biosensors 2015, 5, 712–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, N.M. 30 years of advances in functionalization of carbon nanomaterials for biomedical applications: A practical review. J. Mater. Res. 2017, 32, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalraj, B.; Palanisamy, S.; Chen, S.-M.; Lou, B.-S. Preparation of highly stable fullerene C60 decorated graphene oxide nanocomposite and its sensitive electrochemical detection of dopamine in rat brain and pharmaceutical samples. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 462, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compton, R.G.; Spackman, R.A.; Wellington, R.G.; Green, M.L.H.; Turner, J. A C60 modified electrode: Electrochemical formation of tetra-butylammonium salts of C60 anions. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1992, 327, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassell, A.M.; Scrivens, W.A.; Tour, J.M. Assembly of DNA/fullerene hybrid materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1998, 37, 1528–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

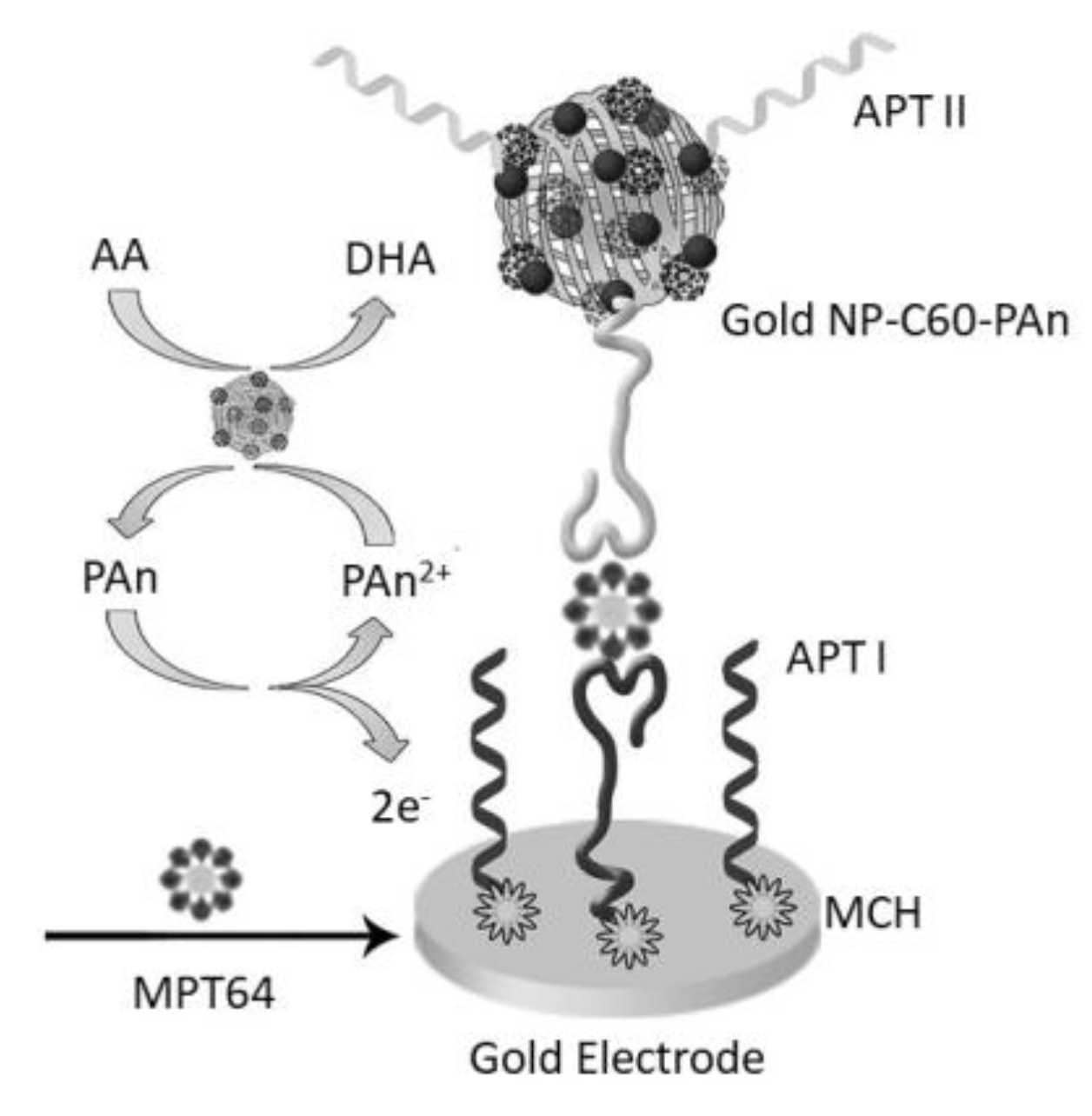

- Bai, L.; Chen, Y.; Bai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Huang, A. Fullerene-doped polyaniline as new redox nanoprobe and catalyst in electrochemical aptasensor for ultrasensitive detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis MPT64 antigen in human serum. Biomaterials 2017, 133, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, D.C.; Honeychurch, K.C. Carbon nanotube (CNT)-based biosensors. Biosensors 2021, 11, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hianik, T. Aptamer-based biosensors. In Encyclopedia of Interfacial Chemistry: Surface Science and Electrochemistry, Wandelt, K., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 7, pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

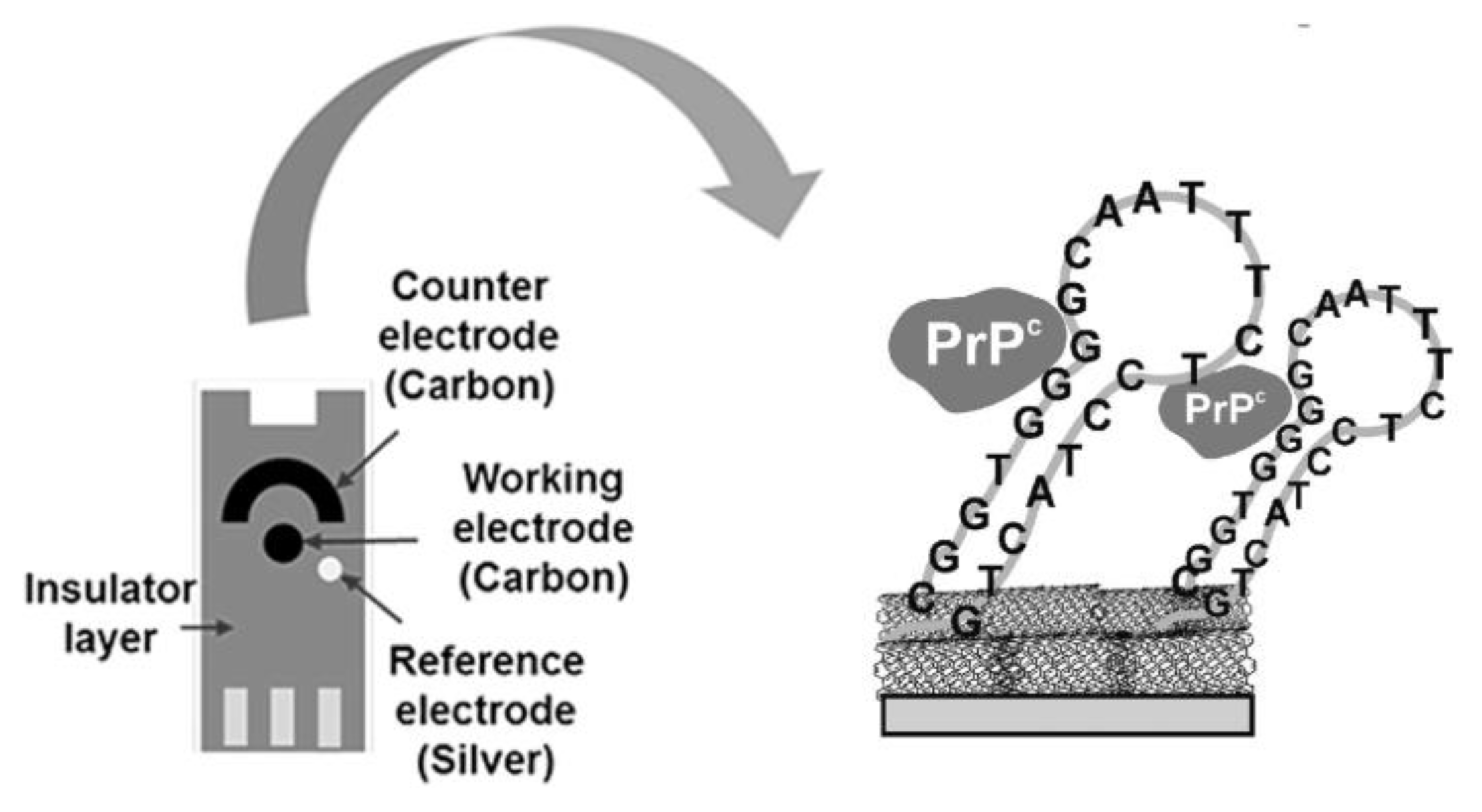

- Hianik, T.; Porfireva, A.; Grman, I.; Evtugyn, G. EQCM biosensors based on DNA aptamers and antibodies for rapid detection of prions. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009, 16, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miodek, A.; Castillo, G.; Hianik, T.; Korri-Youssoufi, H. Electrochemical aptasensor of human cellular prion based on multiwalled carbon nanotubes modified with dendrimers: A platform for connecting redox markers and aptamers. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 7704–7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miodek, A.; Castillo, G.; Hianik, T.; Korri-Youssoufi, H. Electrochemical aptasensor of cellular prion protein based on modified polypyrrole with redox dendrimers. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 56, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelada-Guillén, G.A.; Riu, J.; Düzgün, A.; Rius, F.X. Immediate detection of living bacteria at ultralow concentrations using a carbon nanotube based potentiometric aptasensor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009, 48, 7334–7337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelada-Guillén, G.A.; Blondeau, P.; Rius, F.X.; Riu, J. Carbon nanotube-based aptasensors for the rapid and ultrasensitive detection of bacteria. Methods 2013, 63, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R.; Pulingam, T.; Appaturi, J.N.; Zifruddin, A.N.; Teh, S.J.; Lim, T.W.; Ibrahim, F.; Leo, B.F.; Thong, K.L. Carbon nanotube-based aptasensor for sensitive electrochemical detection of whole-cell Salmonella. Anal. Biochem. 2018, 554, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

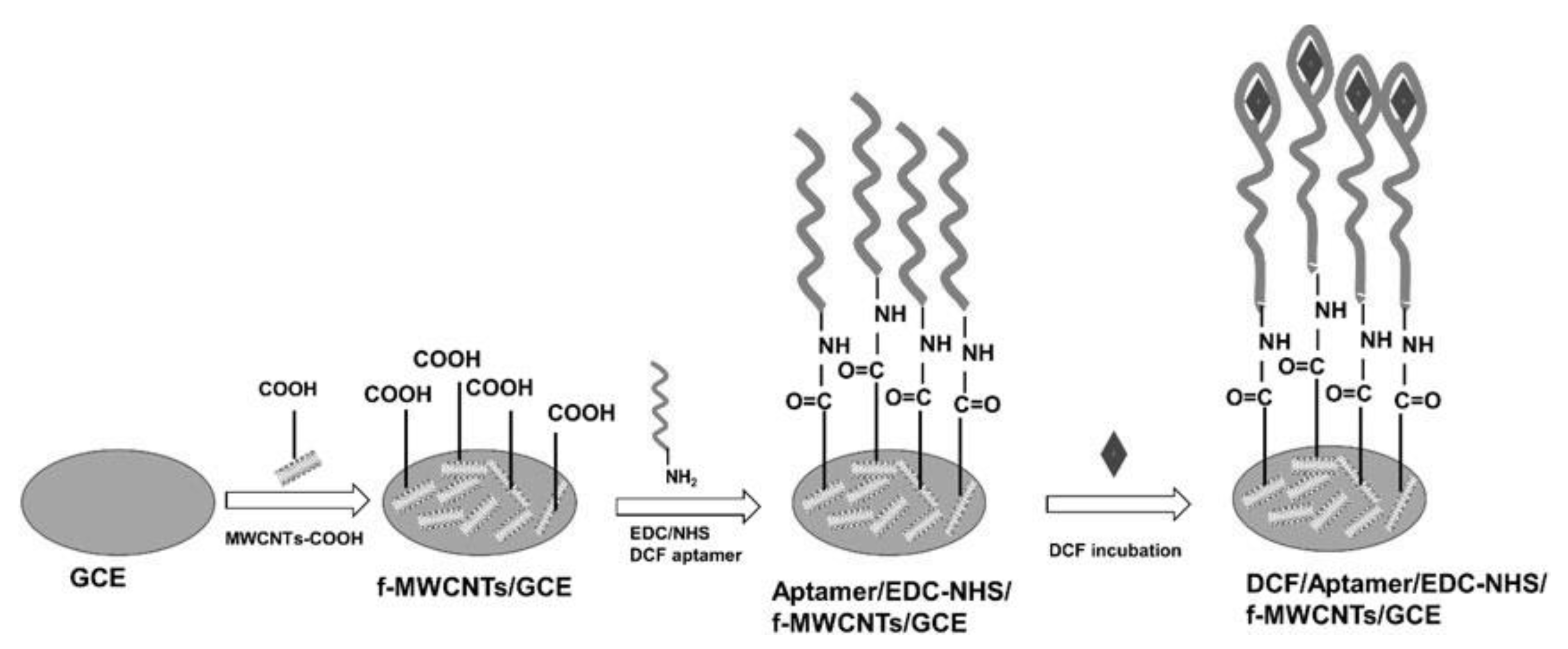

- Zou, Y.; Griveau, S.; Ringuedé, A.; Bedioui, F.; Richard, C.; Slim, C. Functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotube-based aptasensors for diclofenac detection. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 812909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Geng, L. Signal-on electrochemical aptasensor for sensitive detection of sulfamethazine based on carbon quantum dots/tungsten disulfide nanocomposites. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 393, 139054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Pan, J.; Yang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Lu, F.; Chen, Y.; Gao, W. A photoelectrochemical aptasensor for thrombin based on the use of carbon quantum dot-sensitized TiO2 and visible-light photoelectrochemical activity. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikova, T.; Gorbatchuk, V.; Stoikov, I.; Rogov, A.; Evtugyn, G.; Hianik, T. Impedimetric determination of kanamycin in milk with aptasensor based on carbon black-oligolactide composite. Sensors. 2020, 20, 4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, K.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, W. Label-free polygonal-plate fluorescent-hydrogel biosensor for ultrasensitive microRNA detection. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2020, 306, 127554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cancel, G.; Suazo-Dávila, D.; Medina-Guzmán, J.; Rosado-González, M.; Díaz-Vázquez, L.M.; Griebenow, K. Chemically glycosylation improves the stability of an amperometric horseradish peroxidase biosensor. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 854, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visa, M.; Andronic, L.; Enesca, A. Behavior of the new composites obtained from fly ash and titanium dioxide in removing of the pollutants from wastewater. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 388, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şerban, I.; Enesca, A. Metal oxides-based semiconductors for biosensors applications. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Meng, F.; Wang, X.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, M. Carbon-based nanocomposite smart sensors for the rapid detection of mycotoxins. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadzirah, S.; Azizah, N.; Hashim, U.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Kashif, M. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle-based interdigitated electrodes: A novel current to voltage DNA biosensor recognizes E. coli O157:H7. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0139766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimipour, M.; Heydari-Bafrooei, E.; Sanjari, M.; Johansson, M.B.; Molaei, M. A glassy carbon electrode modified with TiO2(200)-rGO hybrid nanosheets for aptamer based impedimetric determination of the prostate specific antigen. Mikrochim. Acta 2018, 186, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muniandy, S.; Teh, S.J.; Appaturi, J.N.; Thong, K.L.; Lai, C.W.; Ibrahim, F.; Leo, B.F. A reduced graphene oxide-titanium dioxide nanocomposite based electrochemical aptasensor for rapid and sensitive detection of Salmonella enterica. Bioelectrochemistry 2019, 127, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

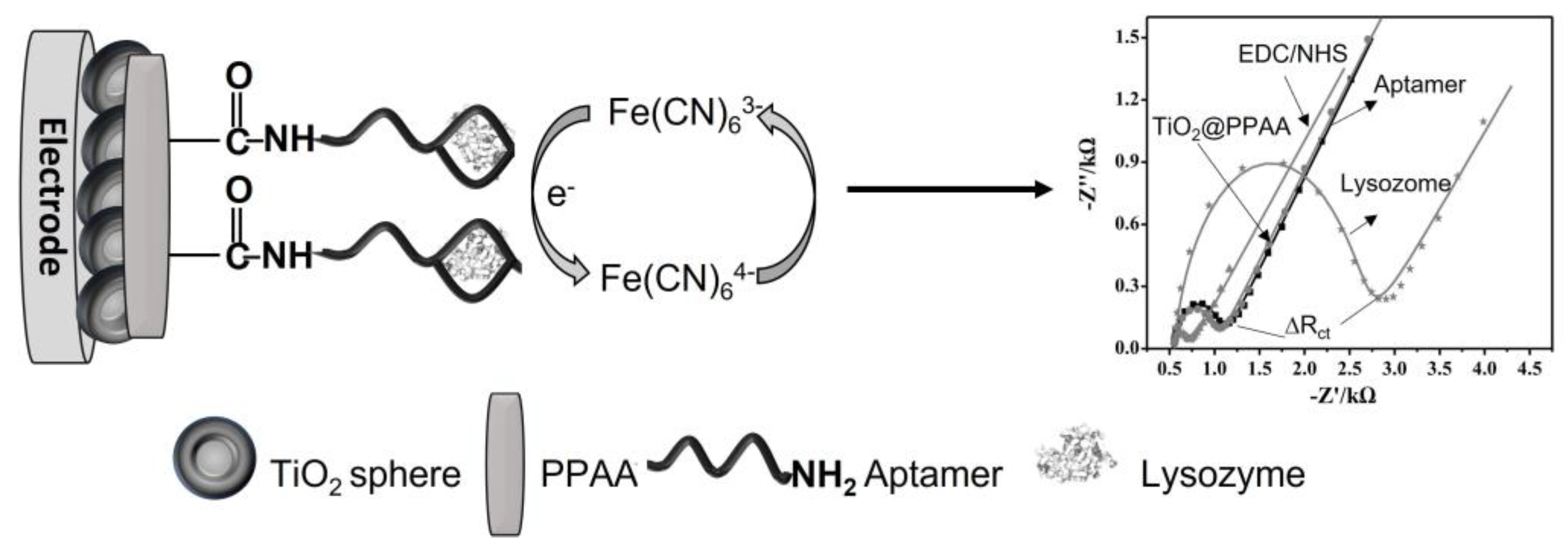

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S.; He, L.; Peng, D.; Yan, F.; Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Fang, S. Feasible electrochemical biosensor based on plasma polymerization-assisted composite of polyacrylic acid and hollow TiO2 spheres for sensitively detecting lysozyme. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 74, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evtugyn, G.; Cherkina, U.; Porfireva, A.; Danzberger, J.; Ebner, A.; Hianik, T. Electrochemical aptasensor based on ZnO modified gold electrode. Electroanalysis 2013, 25, 1855–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

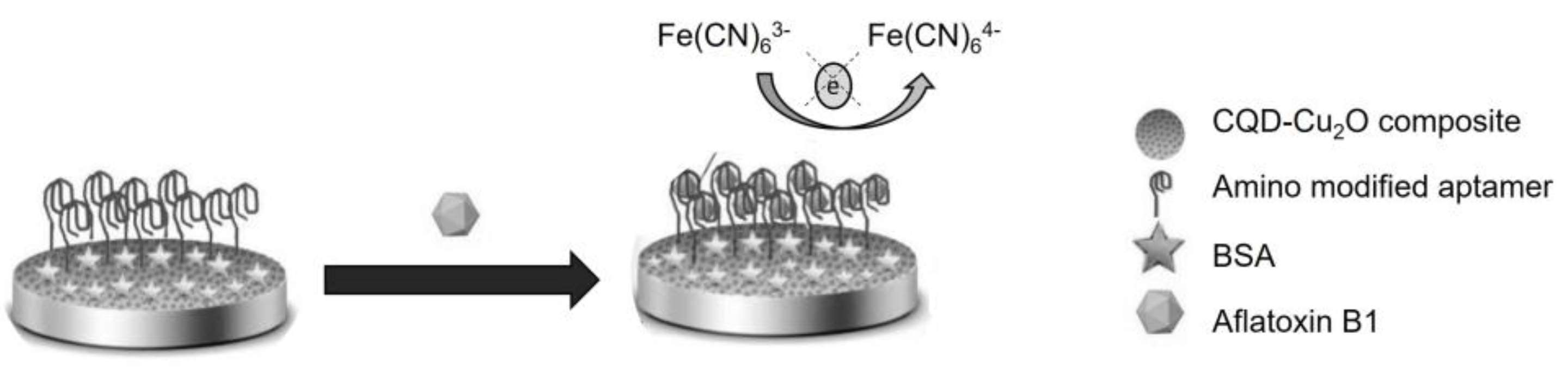

- Rahimi, F.; Roshanfekr, H.; Peyman, H. Ultra-sensitive electrochemical aptasensor for label-free detection of Aflatoxin B1 in wheat flour sample using factorial design experiments. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 128436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowska, I.; Hepel, M.; Kurzątkowska-Adaszyńska, K. Advances in design strategies of multiplex electrochemical aptasensors. Sensors 2021, 22, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evtugyn, G.; Belyakova, S.; Porfireva, A.; Hianik, T. Electrochemical aptasensors based on hybrid metal-organic frameworks. Sensors. 2020, 20, 6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

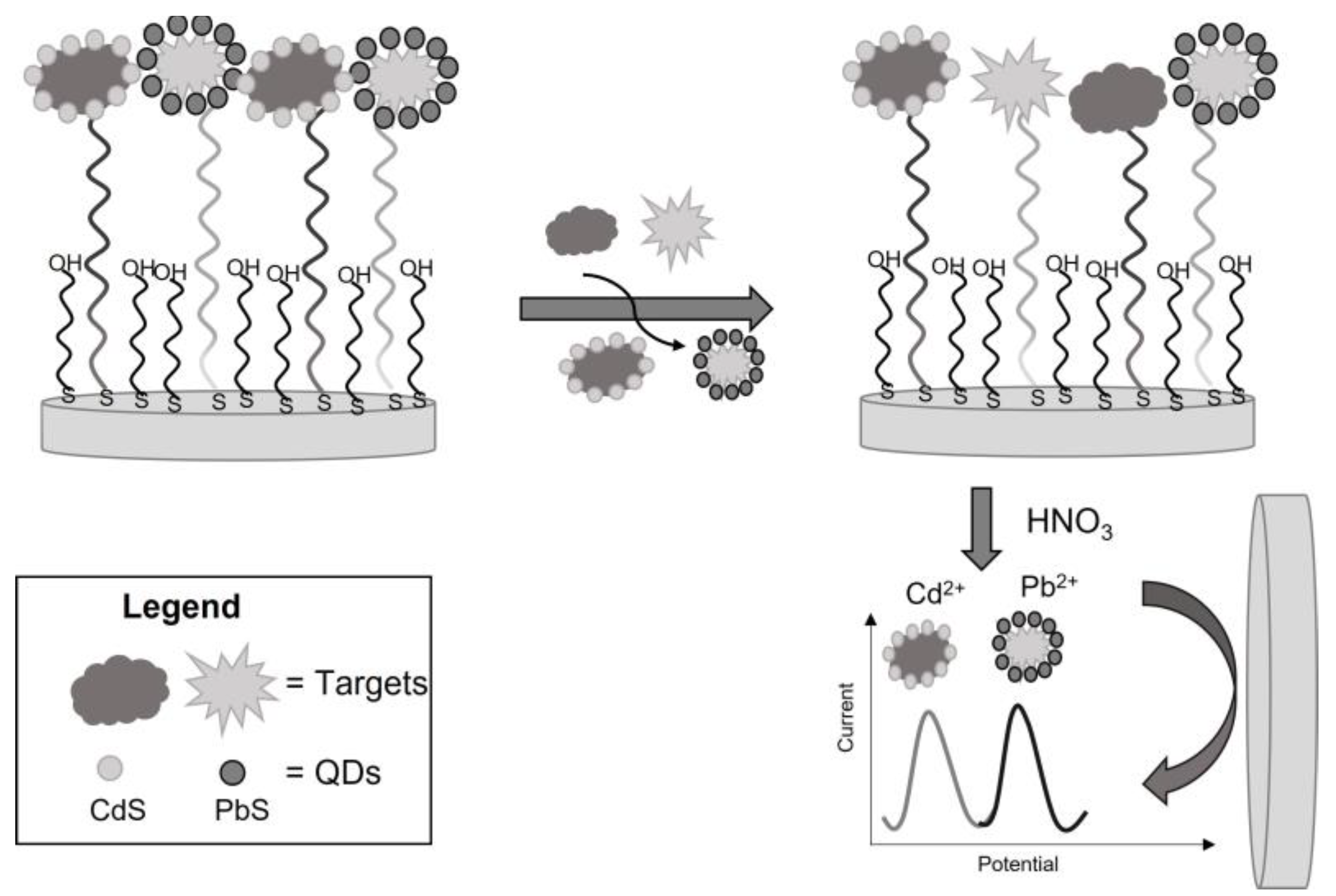

- Hansen, J.A.; Wang, J.; Kawde, A.-N.; Xiang, Y.; Gothelf, K. V; Collins, G. Quantum-dot/aptamer-based ultrasensitive multi-analyte electrochemical biosensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2228–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavel, I.-A.; Lakard, S.; Lakard, B. Flexible sensors based on conductive polymers. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Nie, W.; Tsai, H.; Wang, N.; Huang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Wen, R.; Ma, L.; Yan, F.; Xia, Y. PEDOT:PSS for flexible and stretchable electronics: Modifications, strategies, and applications. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinauskas, A. Self-doped polyanilines. J. Power Sources 2004, 126, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

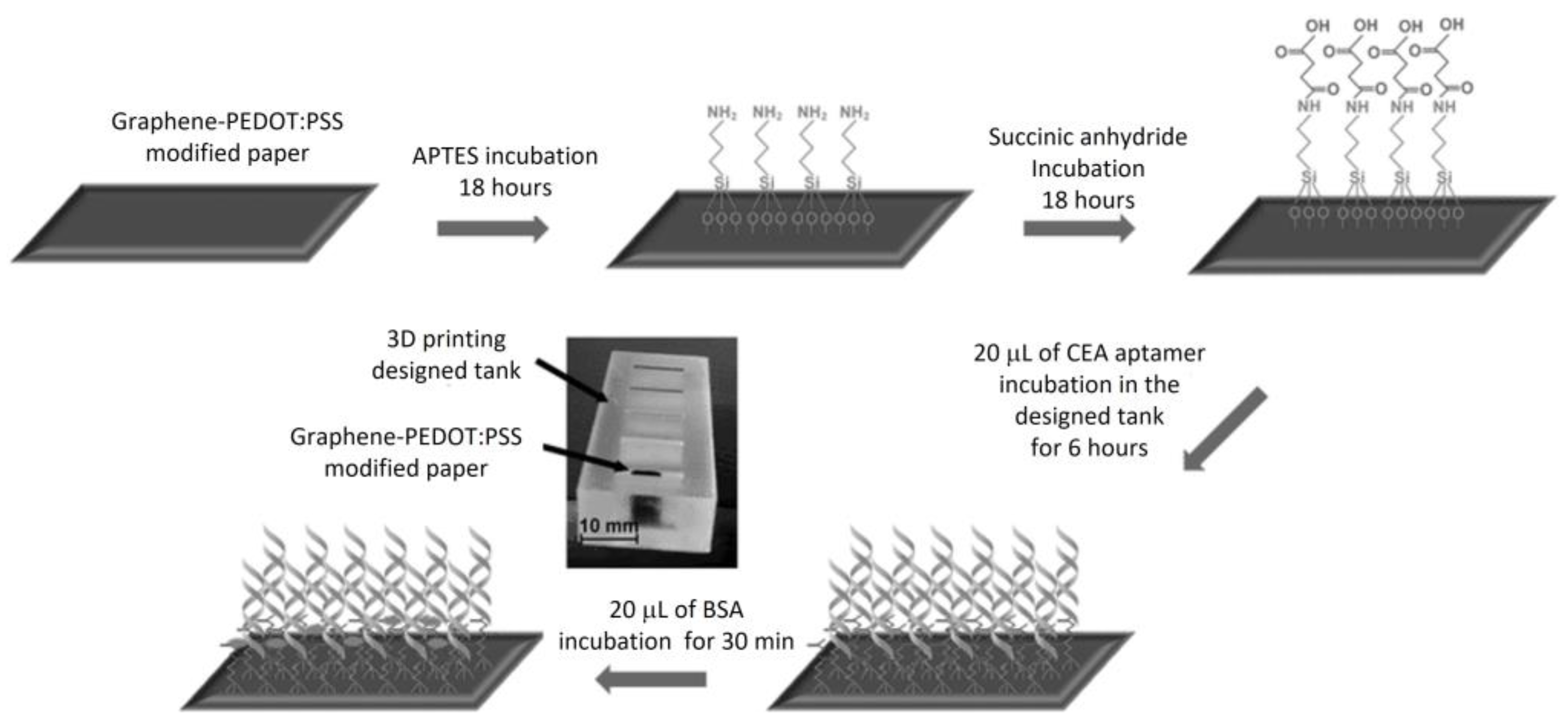

- Yen, Y.-K.; Chao, C.-H.; Yeh, Y.-S. A Graphene-PEDOT:PSS modified paper-based aptasensor for electrochemical impedance spectroscopy detection of tumor marker. Sensors 2020, 20, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

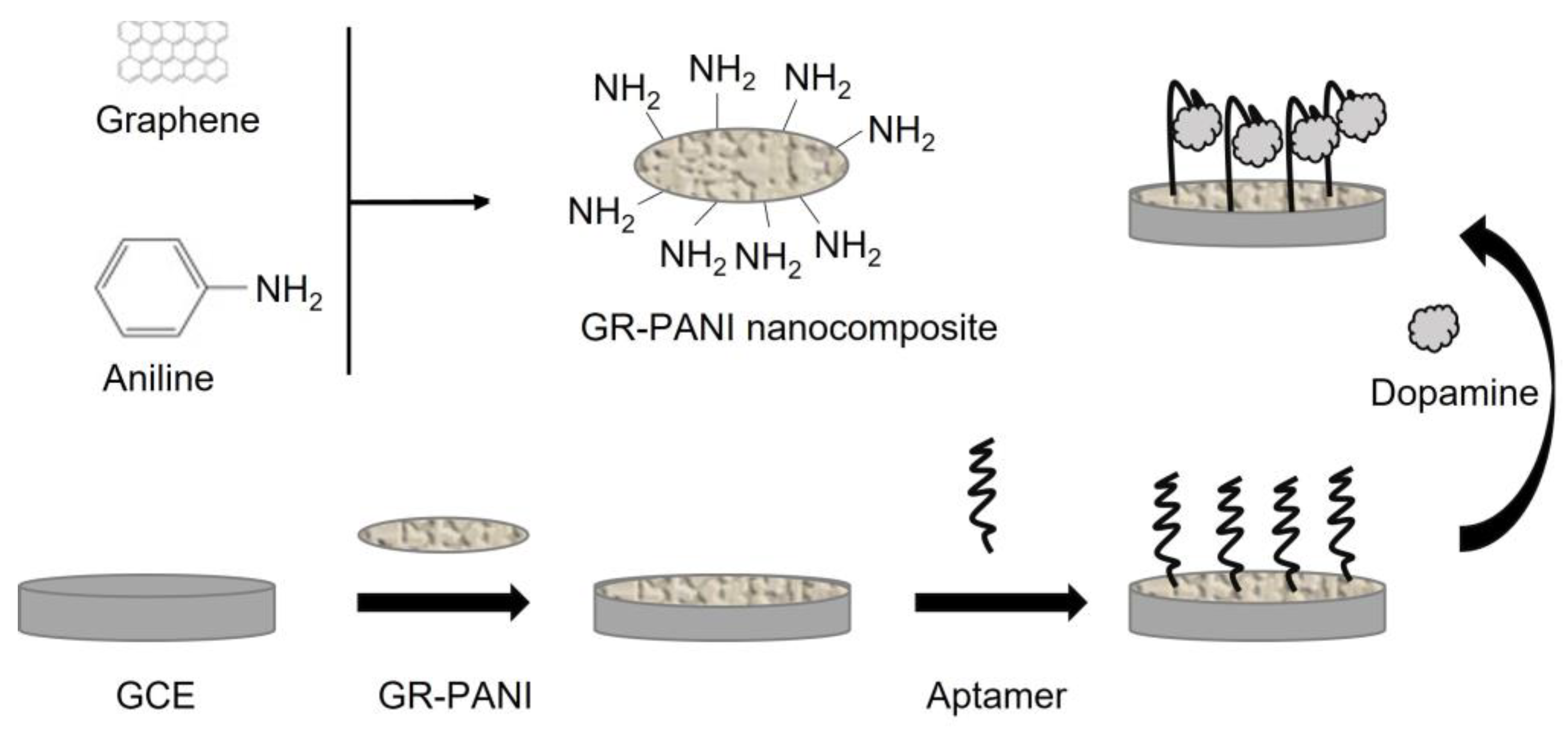

- Liu, S.; Xing, X.; Yu, J.; Lian, W.; Li, J.; Cui, M.; Huang, J. A novel label-free electrochemical aptasensor based on graphene–polyaniline composite film for dopamine determination. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 36, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, P.; Miodek, A.; Yang, D.-K.; Chen, L.-C.; Lloyd, M.D.; Estrela, P. Electro-engineered polymeric films for the development of sensitive aptasensors for prostate cancer marker detection. ACS Sensors 2016, 1, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šafaříková, E.; Švihálková Šindlerová, L.; Stříteský, S.; Kubala, L.; Vala, M.; Weiter, M.; Víteček, J. Evaluation and improvement of organic semiconductors’ biocompatibility towards fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2018, 260, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsan, M.M.; Ghica, M.E.; Brett, C.M.A. Electrochemical sensors and biosensors based on redox polymer/carbon nanotube modified electrodes: a review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 881, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

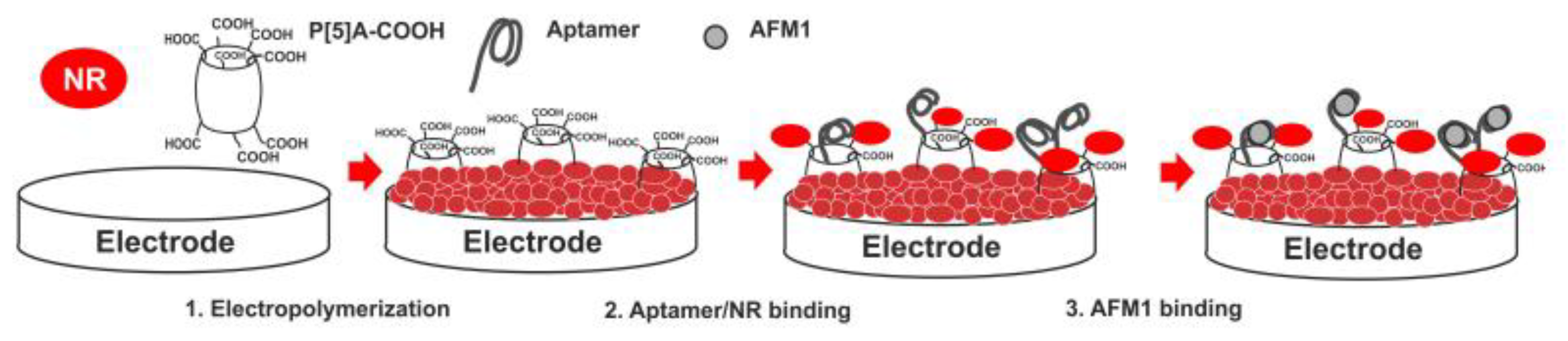

- Smolko, V.; Shurpik, D.; Porfireva, A.; Evtugyn, G.; Stoikov, I.; Hianik, T. Electrochemical aptasensor based on Poly(Neutral Red) and carboxylated Pillar[5]arene for sensitive determination of Aflatoxin M1. Electroanalysis 2018, 30, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

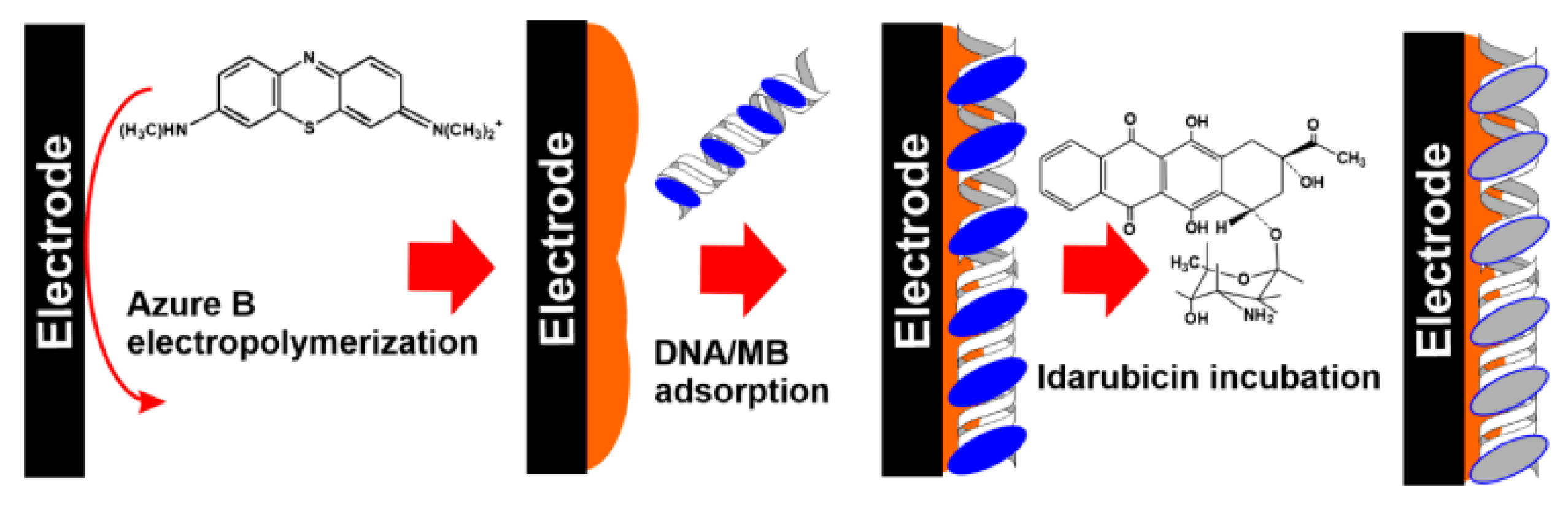

- Goida, A.; Kuzin, Y.; Evtugyn, V.; Porfireva, A.; Evtugyn, G.; Hianik, T. Electrochemical sensing of idarubicin—DNA interaction using electropolymerized azure B and methylene blue mediation. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).