Submitted:

22 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

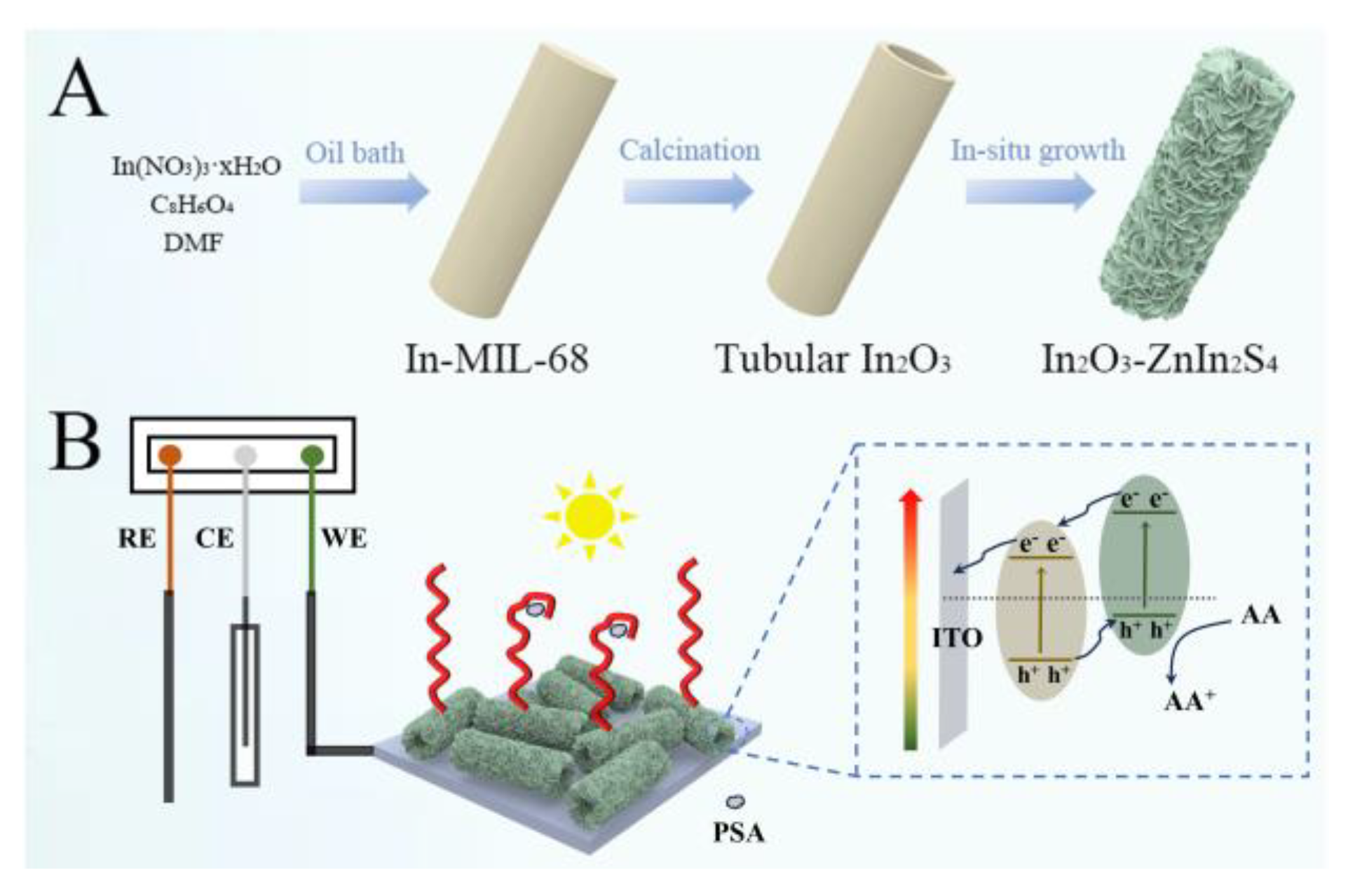

2.1. Preparation of Hollow Tubular In2O3

2.2. Synthesis of Branched Sheet Embedded Tubular In2O3-ZnIn2S4

2.3. Fabrication of Sensing Platform and Analysis Protocol

2.4. Detection Limit Calculation

3. Results and Discussion

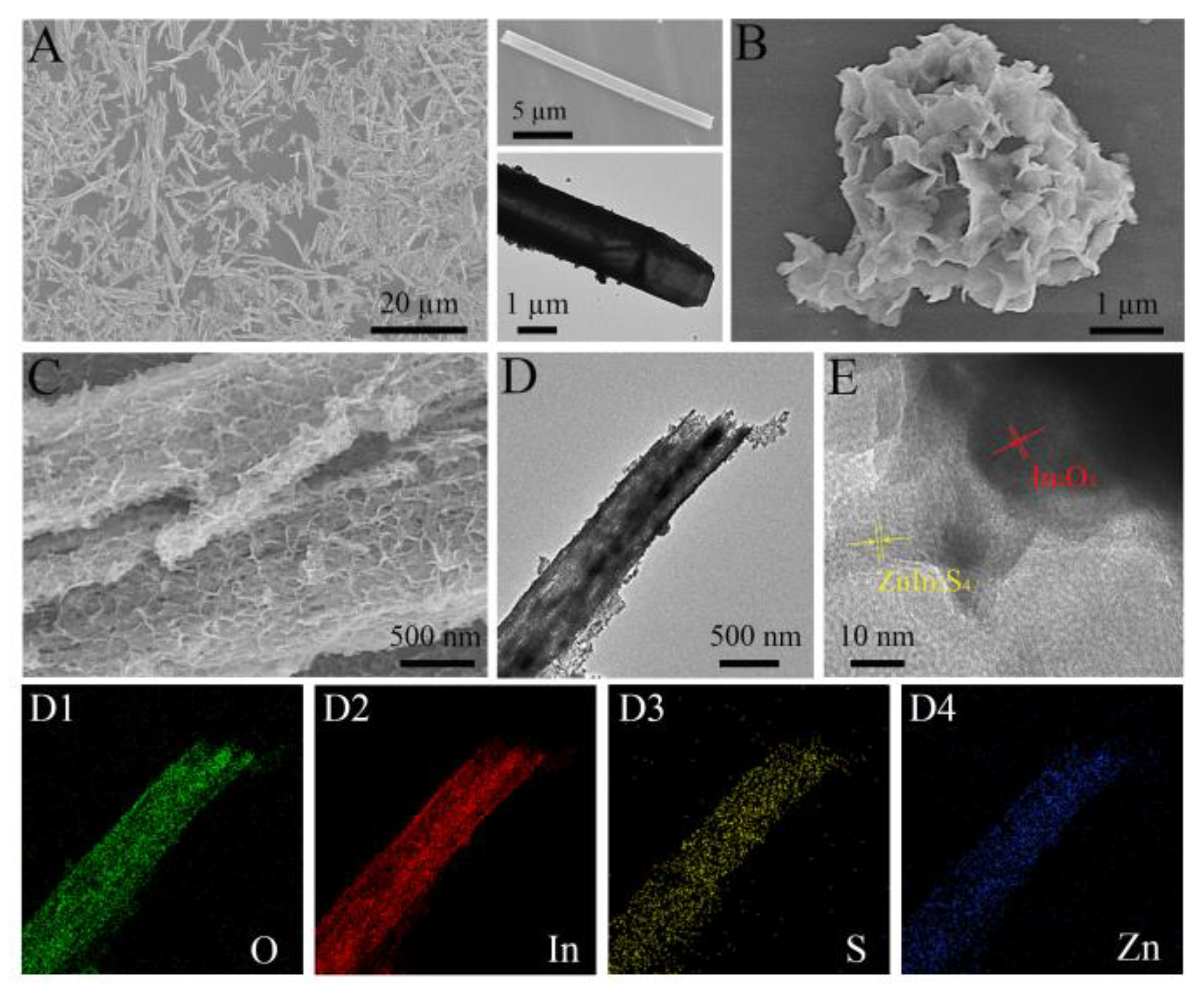

3.1. Morphology and Structure Characterization

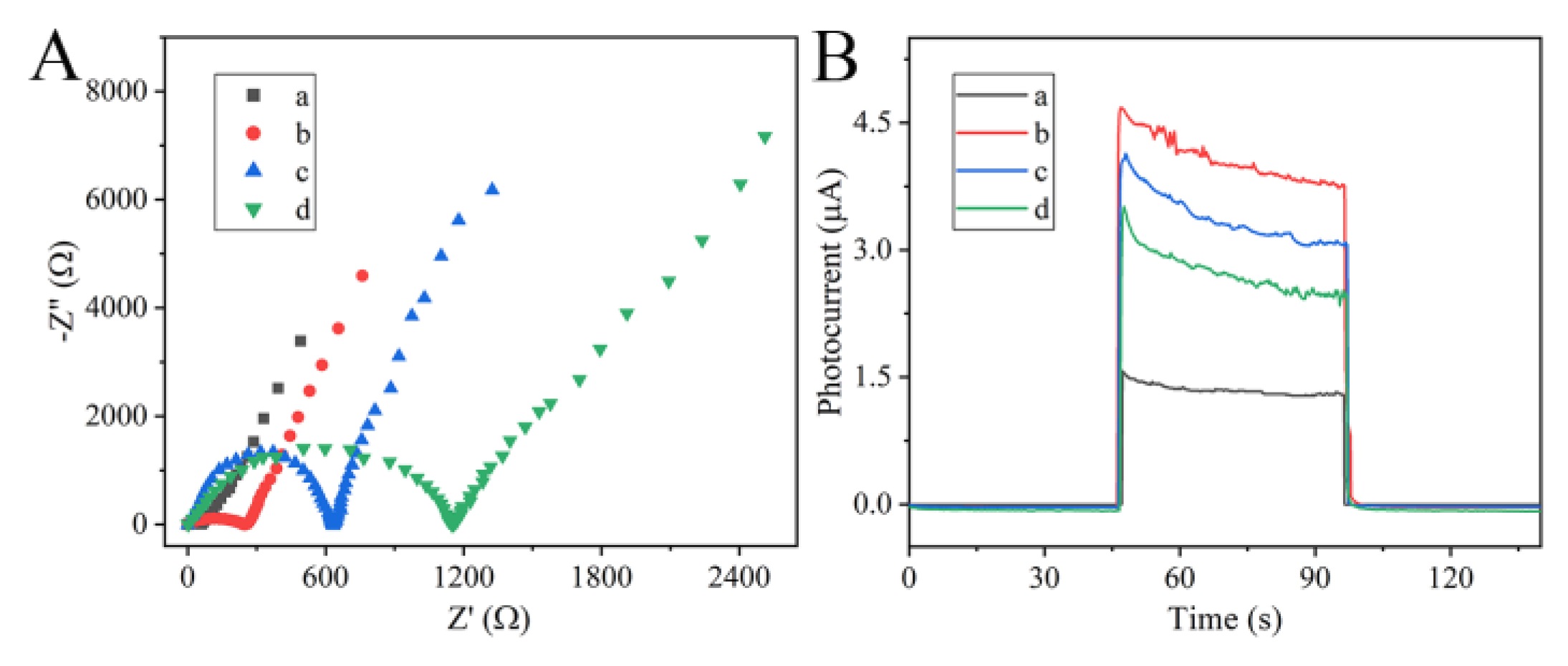

3.2. PEC and EIS Behaviors

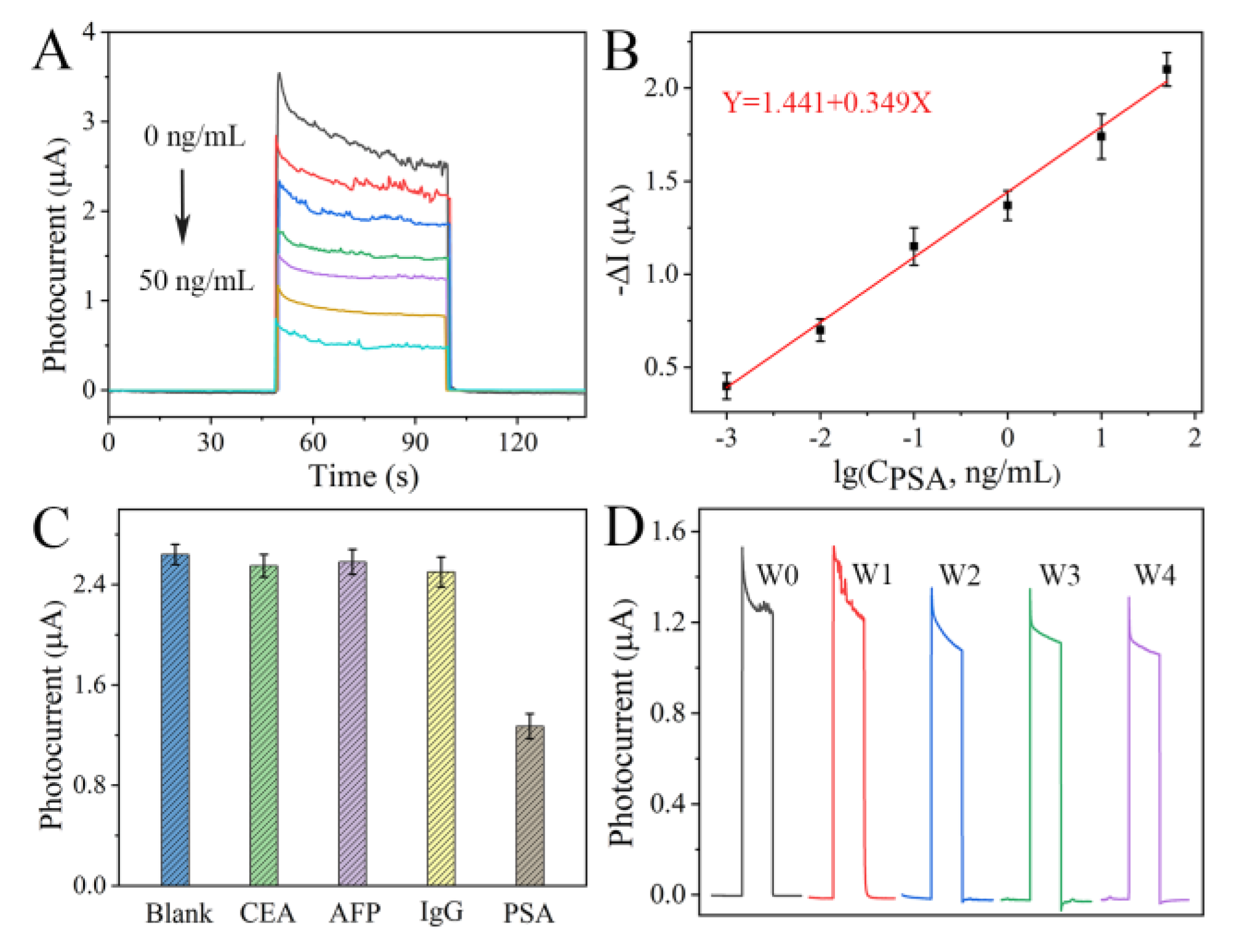

3.3. Analytical Performance

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Homer, M. K.; Kuo, D. Y.; Dou, F. Y.; Cossairt, B. M., Photoinduced charge transfer from quantum dots measured by cyclic voltammetry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14226-14234. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tan, R.; Wu, Z.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Xu, M.; Gu, W.; Zhu, C.; Hu, L., Small-molecule probe-induced in situ-sensitized photoelectrochemical biosensor for monitoring α-Glucosidase activity. ACS sensors 2023, 8, 3257-3263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Feng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xue, X.; Feng, R.; Yan, T.; Yan, L.; Wei, Q., Self-powered photoelectrochemical aptasensor based on MIL-68(In) derived In2O3 hollow nanotubes and Ag doped ZnIn2S4 quantum dots for oxytetracycline detection. Talanta 2022, 240, 123153. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, B.; Ko, T.-K.; Hyun, S.-K.; Lee, C., NO2 sensing properties of WO3-decorated In2O3 nanorods and In2O3-decorated WO3 nanorods. Nano Convergence 2019, 6, 40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Cao, W.; Wang, P.-H.; Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Qiao, Z.; Ding, Z.-J., Fast and sensitive detection of CO by Bi-MOF-derived porous In2O3/Fe2O3 core-shell nanotubes. ACS sensors 2023, 8 (12), 4577-4586.

- Han, C.; Zhang, X.; Huang, S.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, T. T.; Li, Q.; Qian, J., MOF-on-MOF-derived hollow Co3O4/In2O3 nanostructure for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2300797.

- Shi, L.; Benetti, D.; Wei, Q.; Rosei, F., MOF-derived In2O3/CuO p-n heterojunction photoanode incorporating graphene nanoribbons for solar hydrogen generation. Small 2023, 19, 2300606. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lu, K.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Huang, C.; Jia, N., In2O3/Bi2S3 S-scheme heterojunction-driven molecularly imprinted photoelectrochemical sensor for ultrasensitive detection of dlorfenicol. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 58397-58405.

- Han C.; Zhang X.; Huang S.; Hu Y.; Yang Z.; Li T.; Li Q.; Qian J., MOF-on-MOF-derived hollow Co3O4/In2O3 nanostructure for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10 2300797.

- Liu, X.; Zhang L.; Li Y.; Xu X.; Du Y.; Jiang Y.; Lin K., A novel heterostructure coupling MOF-derived fluffy porous indium oxide with g-C3N4 for enhanced photocatalytic activity, Mater. Res. Bull. 2021, 133, 111078. [CrossRef]

- Ren J.; Yuan K.; Wu K.; Zhou L.; Zhang Y., A robust CdS/In2O3 hierarchical heterostructure derived from a metal–organic framework for efficient visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen production, Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 366–375.

- Yang, J.; Zhu, X.; Yu, Q.; He, M.; Zhang, W.; Mo, Z.; Yuan, J.; She, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, H., Multidimensional In2O3/In2S3 heterojunction with lattice distortion for CO2 photoconversion. Chinese J. Catal. 2022, 43, 1286-1294. [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Peng, L.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X.; Yang, C.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Ni, Y., Highly efficient photocatalytic water splitting utilizing a WO3-x/ZnIn2S4 ultrathin nanosheet Z-scheme catalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 908-914. [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Medic, I.; Steinfeldt, N.; Dong, T.; Voelzer, T.; Haida, S.; Rabeah, J.; Hu, J.; Strunk, J., Ultrathin defective nanosheet subunit ZnIn2S4 hollow nanoflowers for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Small Struct. 2023, 4, 2300091. [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Liu, K.; Liu, Y.; Ji, Z.; Wang, X.; Hui, B.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, D.; Jiang, L., Heterostructure with tightly-bound interface between In2O3 hollow fiber and ZnIn2S4 nanosheet toward efficient visible light driven hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 345, 123697. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, S.; Zhou, R.; Li, Y.; He, Z.; Ding, H.; Chen, D.; Ao, W., A review: Synthesis, modification and photocatalytic applications of ZnIn2S4. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 78, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Fang, W.; Xv, R.; Fu, L., TiO2 nanoparticles modified with ZnIn2S4 nanosheets and Co-Pi groups: Type II heterojunction and cocatalysts coexisted photoanode for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2022, 47, 33361-33373. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Xiong, J., Kong, D., Liu, Y., Wu, H., Li, F., Hu, H.; Wang, D.; Guo, X.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, Z., Anchoring ZnIn2S4 nanosheets on oxygen-vacancy NiMoOx nanorods for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130608.

- Kong, D.; Hu, X.; Geng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, D.; Lu, Y., Geng, W.; Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Pu, X., Growing ZnIn2S4 nanosheets on FeWO4 flowers with pn heterojunction structure for efficient photocatalytic H2 production. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 591, 153256.

- Wang, M.; Zhang, G.; Guan, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, Q., Spatially separating redox centers and photothermal effect synergistically boosting the photocatalytic hydrogen evolution of ZnIn2S4 nanosheets. Small, 2021, 17, 2006952. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Shen, H.; Wang, M.; Feng, Q.; Chen, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J., Fabrication of ZnIn2S4 nanosheets decorated hollow CdS nanostructure for efficient photocatalytic H2-evolution and antibiotic removal performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 315, 123698. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guan, B. Y.; Lou, X. W. D., Construction of ZnIn2S4-In2O3 hierarchical tubular heterostructures for efficient CO2 photoreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 5037-5040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.-S.; Choi, M.; Baek, M.; Hsieh, P.-Y.; Yong, K.; Hsu, Y.-J., CdS/CdSe co-sensitized brookite H:TiO2 nanostructures: Charge carrier dynamics and photoelectrochemical hydrogen generation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 225, 379-385. [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Liu, K.; Liu, Y.; Ji, Z.; Wang, X.; Hui, B.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, D.; Jiang, L., Heterostructure with tightly-bound interface between In2O3 hollow fiber and ZnIn2S4 nanosheet toward efficient visible light driven hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 345, 123697.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).