1. Introduction

The SRY-related HMG-box (Sox) family is a group of transcriptional regulators defined by the presence of a highly conserved high-mobility group (HMG) domain that mediates DNA binding [

1]. This domain was first identified in a male determinant in eutherian mammals, which is called the sex-determining region on the Y chromosome (Sry) [

2,

3]. Since then, numerous Sox proteins were identified and analyzed, and the presence of Sox genes has now been established in almost all metazoans [

4]. Based on homology within the HMG domain and structural features outside the domain, the Sox gene family can be subdivided into groups A to K [

5]. It has been shown extensively in vertebrates and invertebrates that the Sox family genes are involved in the regulation of many important developmental processes, such as sex determination and differentiation, cell type specification, neurogenesis, organogenesis, etc. [

4,

6]

Among the many functions of Sox genes, regulating on sexual development has been the focus of much attention in aquatic animals, particularly in fish. This is not only because aquatic animals often have diverse reproductive strategies and sex determination systems, but also because they exhibit substantial sex dimorphism, which is closely linked to several economic traits, including growth rate and body size [

7]. To date, multiple Sox genes have been implicated in the regulation of sex determination, sex differentiation and gonadal development in fish, although their specific roles may vary between species [

6]. Most of these Sox genes showed sexually dimorphic expression in the gonads, and in some cases, sex reversal could be achieved through the genetic manipulation of a single Sox gene.

The most extensively studied Sox genes in fish are probably the members of group E, represented by Sox8, Sox9, and Sox10. In mammals, Sox9 has been proposed as a downstream gene of Sry because of its capable of determining male sex in the absence of Sry [

8]. Sox8 resembles Sox9 in its expression profile and biochemical properties, and can partly substitute for Sox9 [

9]. Sox10 is also involved in the male determination with the ability to activate the transcriptional target of Sox9 [

10]. Despite the diverse sex-forming mechanisms, numerous studies have shown that Sox8 and Sox9 are also important for male development in fish [

6]. Sox9 is specifically expressed in testis in many gonochorism fish species [

11,

12,

13], and in the hermaphrodite fish, the Sox9 mRNA increased during the female to male transition, suggesting a role in testis differentiation [

14]. So far, reports of Sox10 in fish are very limited, but it seems to be a multifunctional gene that are expressed in the gonads of both sexes [

15].

As another important group of aquatic animals, crustaceans also have variable sex determination systems, although the mechanisms involved are poorly understood. Nevertheless, it has been widely accepted that the male differentiation of crustaceans is controlled by an insulin-like androgenic gland hormone (IAG) secreted by the male specific androgenic gland (AG) [

16]. Several transcriptional binding sites for Sox were predicted upstream of IAG genes in the oriental river prawn Macrobrachium nipponense [

17,

18], implying the involvement of Sox genes in the sexual development of crustaceans. Similar to mammal and fish, the SoxE members was also proposed as sex-related factors in crustaceans. The mRNA of a SoxE gene was mainly located in oocytes and spermatocytes of oriental river prawn Macrobrachium nipponense, while its expression in males was significantly higher than that in females during the post-larval development [

19]. In the mud crab, Scylla paramamosain, the Sox9 was shown to positively regulate the expression of vitellogenesis-inhibiting hormone (VIH) by directly binding the promoter region, and its RNA silencing resulted in the significant decrease of VIH as well as the increase of vitellogenin expression in ovary and hepatopancreas of a mature female [

20]. However, the regulatory relationship between SoxE and IAG has not been demonstrated previously.

The swimming crab, Portunus trituberculatus, is an economically essential crab species in Southeast China, and has been extensively artificially propagated and cultivated. Elucidating the mechanism of sex development will be beneficial to develop sex control technology, which is essential for its aquaculture industry. In the present study, a male-specific SoxE was characterized in P. trituberculatus, and its transcriptional interaction with IAG was revealed using RNA interference and mock IAG treatment. In addition, the putative role and mechanism of SoxE on testicular development were also investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

For tissue sampling, wild male crabs (body weight, 280-350 g) were purchased at February, April, August, October, and December from the local aquatic market in Guoju District, Ningbo City, Zhejiang Province, China. The timepoints were designed to be consistent with the different stages of testicular development of

P. trituberculatus according to previously reported [

21]. In addition, female crabs were purchased at December when their ovaries are at vitellogenic stage. Tissues including hepatopancreas, muscles, ovaries, testis, androgenic gland, heart, brain, thoracic ganglion, eyestalks, and Y-organ were dissected on ice, and stored in RNA preservation fluid (Cwbiotech, Taizhou, China) at −80 °C until RNA extraction.

For samples of the embryonic and larval development, female crabs that were about to ovulate spawn were bought from Sanmen, Ningbo at April 2021, and temporarily reared in a capacious tank on the aquaculture base of the Institute of Marine and Fisheries of Ningbo, China, waiting for ovulation the shedding of their eggs. Samples were collected from different developmental stages, including embryos, larvae and the newly settled juveniles [

22]. All samples were stored in RNA preservation fluid (Cwbiotech) at -80℃ until RNA extraction.

2.2. Extraction of Total RNA and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from different samples using the RNA-Solv® reagent (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop 2000 UV Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cheshire, UK). The genomic DNA removed with (10× gDNA Remover Mix) and the first strand of cDNA was synthesized using a HiFiScript gDNA Removal cDNA SynthesisKit (Cwbiotech, Taizhou, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, followed by storage at −80 °C until use.

2.3. Molecular cloning and characterization

The sequence of PtSoxE were obtained using a keyword-based screening of our RNAseq library (SRR13870346), and was validated using a pair of specific primers (

Table 1). The PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel (Vazyme, China) by electrophoresis, and the bands corresponding to the expected size were excised, purified, and the amplicon was ligated into the pMD19-T vector (Takara, Japan). The ligated product was transformed into competent Escherichia coli DH5α cells and five positive clones were selected for sequencing. The open reading frame (ORF) was predicted using the ORF Finder (http://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html), and the conserved domains of PtSoxE was analyzed using the SMART (

http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method by MEGA7.0 (

https://www.megasoftware.net/).

2.4. siRNA synthesis

Three siRNAs for PtSoxE were designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China) with the following sequences: sense and antisense of siRNA-882, 5′- CGGACUCACUAGAAAGUAUTT -3′ and 5′-AUACUUUCUAGUGAGUCCGTT-3′, respectively; sense and antisense of siRNA-905, 5′- CGUGCUGAGAUGAAUAAGUTT-3′ and 5′-ACUUAUUCAUCUCAGCACGTT-3′, respectively; sense and antisense of siRNA-1016, 5′-GCCACCAUGAAUACUGUAATT-3′, and 5′-UUACAGUAUUCAUGGUGGCTT-3′, respectively. A negative control siRNA (sense and antisense, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ and 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′, respectively), which shares no homology to the sequence of the target PtSoxE was employed in this study. All the synthetic siRNAs were dissolved in DEPC-H2O prior to use.

2.5. Preparation of AG homogenate and recombinant IAG

The AG homogenate was prepared according to Cui [

23]. Briefly, 10 AGs were isolated from male crabs purchased at August, and homogenized with pestle on ice in phosphate-buffered saline. After centrifugation for 20 min (16,000×g, 4℃), the supernatant was collected and the procedure was repeated one more time. The obtained supernatant was stored at 4℃ until use. For preparation of the recombinant IAG (rIAG), the ORF region of PtIAG (GenBank accession No. KX168425) was amplified, liganded into pET-28a-sumo, and expressed in the Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3). The fusion protein was mainly expressed in soluble form and was further purified by HisTrap HP column. The concentration of rIAG was determined using Bradford methods.

2.6. In vitro experiments

The testis and AG explants were prepared as previously described [

21], and precultured in M199 medium for 1 h. Two sets of in vitro experiments were conducted. The siRNA-mediated RNA interference of PtSoxE was performed on testis and AG explants, and the experimental siRNA or NC siRNA were mixed with the Lipofectamine® 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen, USA) in equal volumes, and then added into the culture medium for incubation. The treatments with AG homogenate and recombinant IAG were performed only on testis, and 3.5 nM, 35 nM, 350 nM of recombinant IAG were used. All samples were collected for RNA extraction after co-cultured at 26 °C for 8 h.

2.7. Gene expression analysis

The tissue distribution of PtSoxE was detected by semiquantitative PCR using a pair of specific primers (

Table 1). Tissues sampled in December were used for analysis. β-actin was used as the positive control. Amplification was performed with the following program: denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 90 s, with a final elongation at 72 °C for 10 min. The products were assessed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gel. Other gene expression analysis was performed using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). PCR was carried out using the SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II Kit (Takara, Kyoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 56 °C for 20 s.Relative mRNA expression levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA expression and calculated using the comparative Ct (2−ΔΔCt) method [

24]. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were subjected to a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Student’s t-test or Tukey’s multiple-group comparison test (SPSS 24.0 software). Significant differences were accepted at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Molecular characterization of PtSoxE

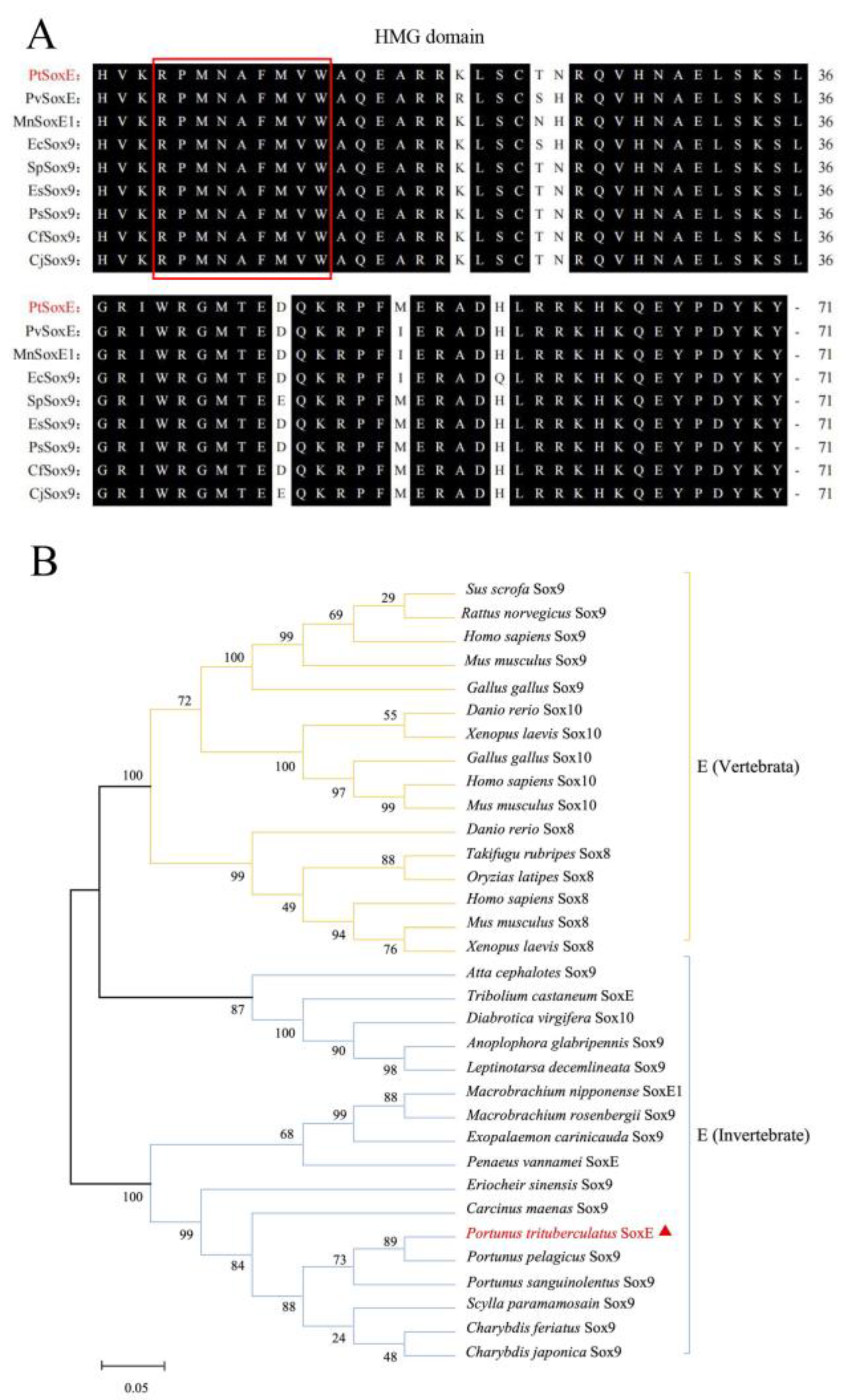

We obtained a 1479 bp PtSoxE cDNA (GenBank accession No. OL9440166) which encodes a protein with 492 amino acids (

Supplementary material 1). SMART analysis indicated the HMG domain of PtSoxE located from amino acid position 148 to 218, and the multiple sequence alignment with known crustacean SoxE sequences showed this domain was highly conserved among different species (

Figure 1A). It was revealed in phylogenetic analysis that the selected SoxE sequences were divided into three major branches, one for vertebrates, one for invertebrate insects and one for invertebrate crustaceans. PtSoxE was clustered into the crustacean branches, and showed most closely related to the Sox9 from Portunus pelagicus (

Figure 1B).

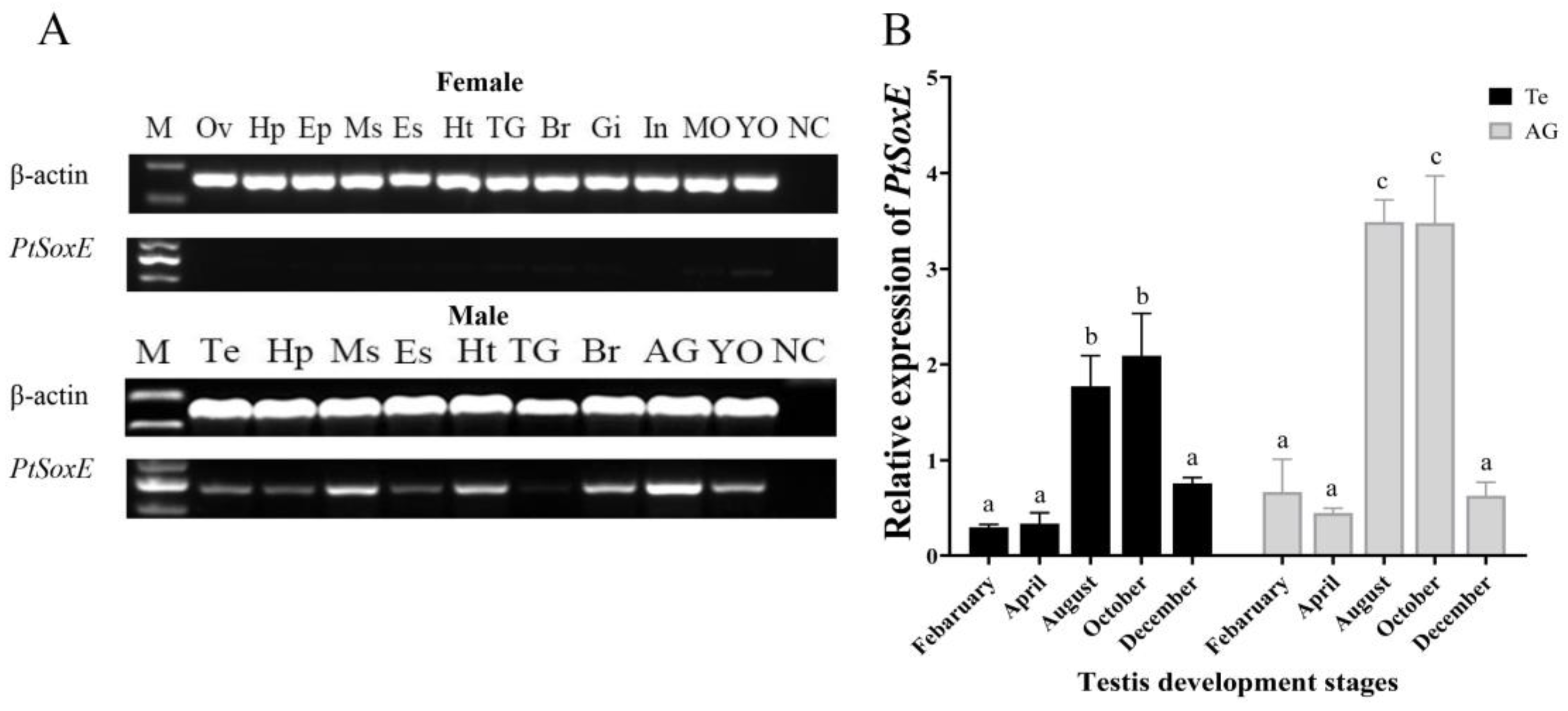

3.2. Spatial and temporal patterns of PtSoxE expression

Semi-quantitative PCR showed that PtSoxE gene was specifically expressed in males. PtSoxE exhibited an extensively expression in male tissues, with the highest mRNA levels in AG and followed by muscle, heart, brain, and Y-organ. The PtSoxE expression was detected in testis, but at lower levels when compared with above tissues (

Figure 2A).

Given the importance of AG and testis in male sexual development, the annual expression of PtSoxE in the two tissues was further examined. The results showed similar changes in PtSoxE expression in both tissues, which was low in February and May, increased significantly in August and October, and fell back in December (

Figure 2B). Since August and October are the peak periods of testis development [

21], this result suggests that PtSoxE may have an important regulatory role in male reproductive development.

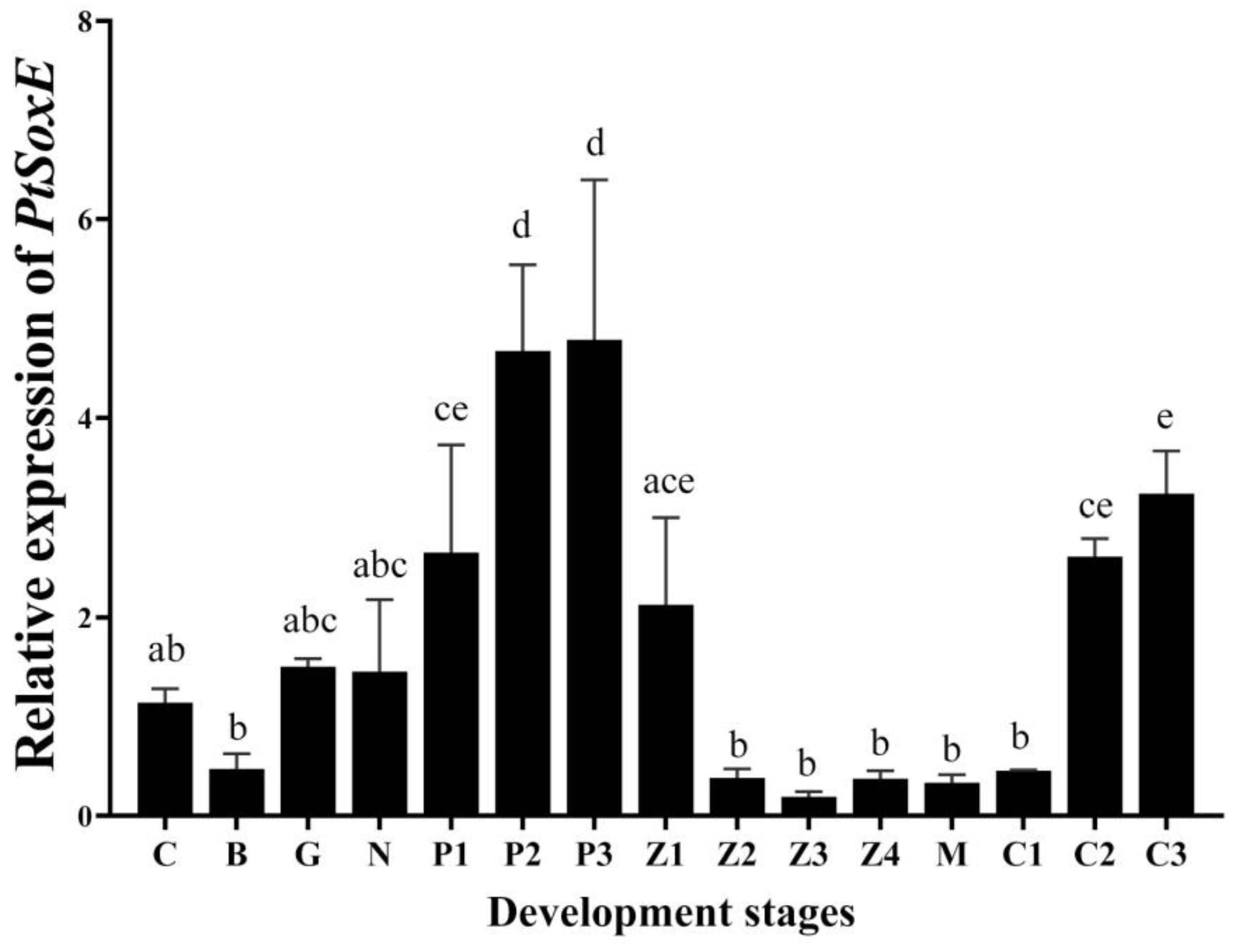

During the development of embryo and larval, the PtSoxE gene expression increased from the protozoan Ⅰ (P1) stage, to the maximum level at P2 and P3 stages. After hatching, PtSoxE mRNA levels decreased rapidly, remaining low during larval development, and returned to high levels at the juvenile crab II stage (C2) (

Figure 3).

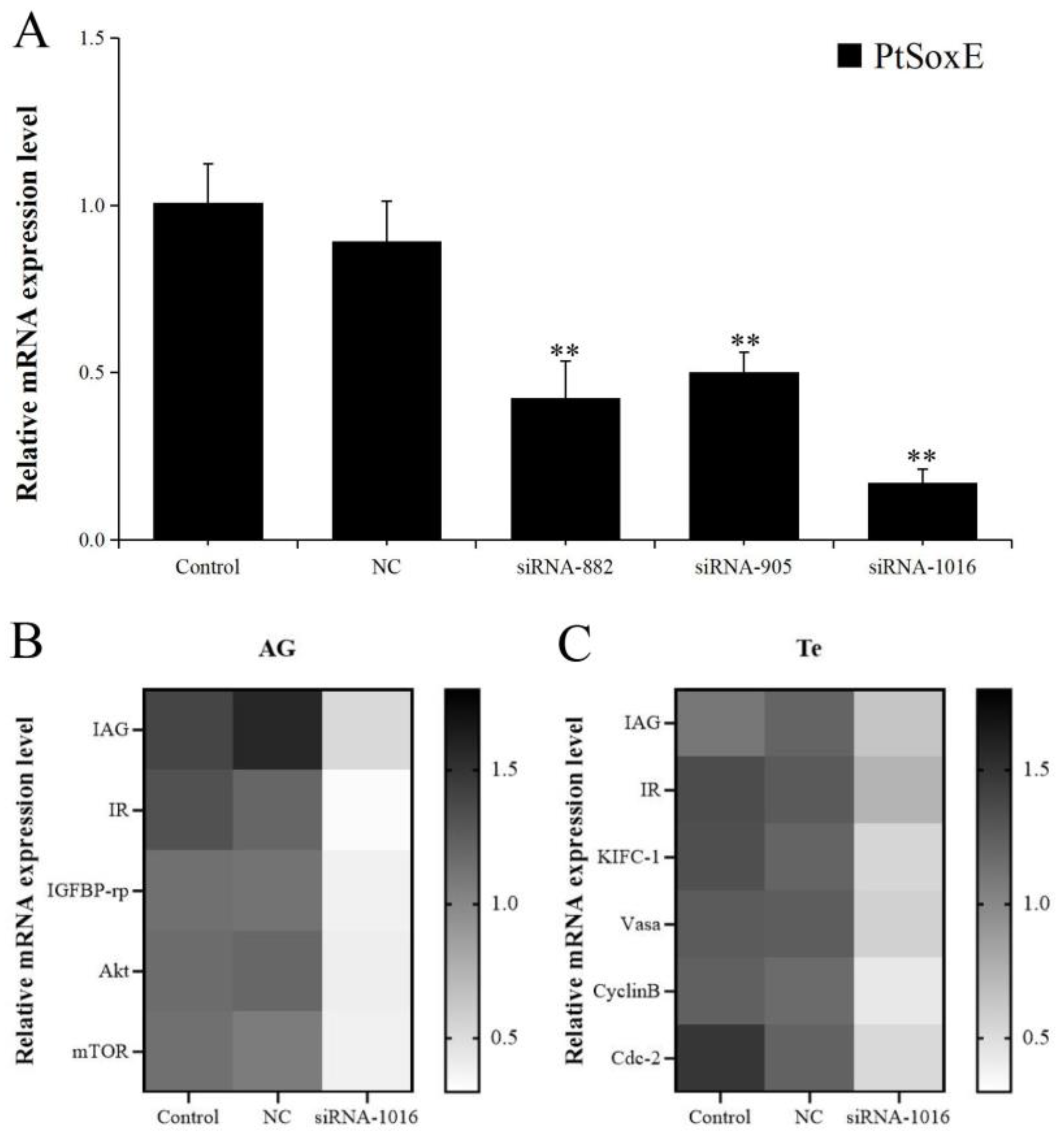

3.3. Effects of PtSoxE siRNA on gene expression in AG and testis

The RNAi efficiency of the synthetic PtSoxE siRNAs (siRNA-882, siRNA-905, siRNA-1016) was evaluated by examining the PtSoxE expression in AG. All three siRNAs caused significantly decrease in PtSoxE expression when compared with the negative control siRNA, the RNAi efficiency was 53% for siRNA-882, 44% for siRNA-905, and 81% for siRNA-1016 (

Figure 4A). Therefore, treatment of siRNA-1016 was used for further analysis. In the siRNA-1016 treated AG, the expression of IAG and several insulin pathway genes, including insulin receptor (IR), insulin-like growth factor banding protein-related peptide (IGFBP-rp), protein kinase B (Akt), and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) were also downregulated (

Figure 4B). While in testis, the siRNA-1016 caused reduction in expression of IAG and insulin receptor (IR), as well as some spermatogenesis-related genes, such as kinesin-like protein (KIFC-1), ATP-dependent RNA helicase (Vasa), CyclinB and cyclin-dependent kinase-2 (Cdc-2) (

Figure 4C).

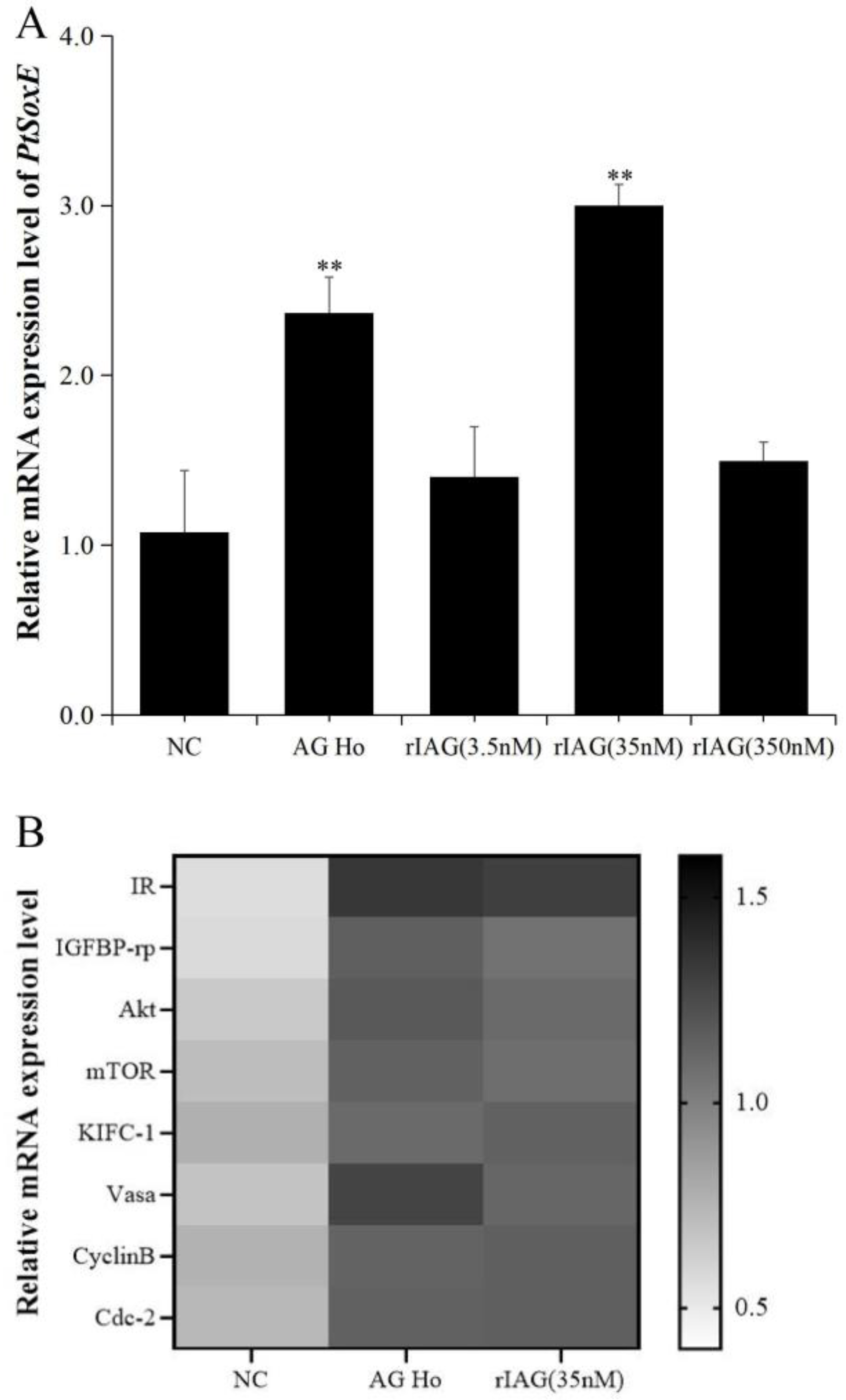

3.4. Effects of AG homogenate and rIAG on PtSoxE expression in testis

To investigate whether IAG may have a role on PtSoxE expression, the testis explants were treated with AG homogenate and recombinant IAG, and the changes in PtSoxE transcript levels were determined. Significant increases in PtSoxE expression were found in treatments with AG homogenate and 35 nm of rIAG when compared with the control group, while there was no obvious change in PtSoxE expression when treated with 3.5 and 350 nm of rIAG (

Figure 5A). In the AG homogenate and 35 nm rIAG groups, genes involved in the insulin pathway (IR, IGFBP-rp, Akt, mTOR) and spermatogenesis (KIFC-1, Vasa, CyclinB, and Cdc-2) were also up-regulated (

Figure 5B).

4. Discussion

In this study, a Sox family gene sequence hallmarked with a HMG domain was identified in the swimming crab,

P. trituberculatus. Multiple sequence alignment showed that the obtained sequence shares high identities to the known SoxE family sequences of crustaceans, and their HMG domains are highly conserved, thus designating as PtSoxE. It was worth noted that many SoxE sequences of crustaceans were designated as Sox9, but this may not be rigorous. In vertebrates, the SoxE subfamily is mainly consist of Sox8, Sox9, and Sox10, whereas in invertebrates, only one or two SoxE sequences were identified within a species. In an early report, the Drosophila Sox100B was clustered into SoxE branch but separated with mouse Sox8, Sox9, and Sox10 [

25]. Our phylogenetic analysis supports the separation of vertebrate and invertebrate SoxE proteins, and apparently, the current invertebrate SoxE genes can be referred as orthologues of vertebrate Sox8, 9, and 10, but cannot be specifically classified into any one of these groups.

Tissue distribution analysis showed that PtSoxE was expressed exclusively in male tissues of

P. trituberculatus, suggesting it may play an important role in male sexual development. To our knowledge, this is the first report of male-specific expression of the SoxE gene in crustaceans. In other two reports, the SoxE genes from the mud crab S. paramamosain and the oriental freshwater prawn M. nipponense were expressed in both sexes, and both ovarian and testicular related roles were proposed [

19,

26]. This difference in expression and function seems difficult to explain giving that the highly conserved DNA-binding domains (HMG domains) may lead to similar transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. However, it is indeed that the expression patterns and physiological functions of fish SoxE genes also varies considerably across species. For instance, in the gonochorism fish, many studies have shown that Sox9 is expressed specifically in testis, but its biased expression in ovaries has not been uncommonly [

6].

The PtSoxE transcripts were found most abundant in AG, which gives rise to the possibility that it may be related to the IAG. Although potential transcription factor binding sites for Sox proteins had been predicted in the 5'-flanking region of

M. nipponense IAG [

17,

18], the regulatory effect of Sox members on IAG was not previously reported. The siRNA treatments in the present study showed that the PtSoxE silencing led to reduction in IAG expression in AG and testis, which suggested the PtSoxE might be an upstream regulator of IAG. As an insulin-like peptide, it has been widely accepted that the molecular action of IAG achieve through the classical IIS pathway [

27,

28,

29]. In our previously report, treatment with IAG dsRNA caused significantly decrease in the expression of several IIS pathway genes, such as IR, IGFBP-rp, Akt, and mTOR [

21]. In AG explants, these IIS pathway genes were also down-regulated by PtSoxE silencing. One explanation for this might be the reduction in IAG signaling induced by siRNA treatment, but firmly conclusion requires the demonstration of whether PtSoxE have a direct regulatory role on these IIS pathway genes.

In its annual expression change, the PtSoxE in AG was highly expressed in August and October, and the AG was in the secretory phase during this period [

30]. However, according to a previous study by our group, the most abundant expression of PtIAG occurs during the synthesis phase of AG, which is the time period from May to July [

31]. This inconsistency suggested other mechanisms may be involved in the regulation of IAG expression, but also raised question about whether IAG affects PtSoxE expression. Treatments with AG homogenate and rIAG (35 nM) showed a stimulatory regulation of IAG on PtSoxE, and the induced expression of IIS pathway genes inferred a putative activation mechanism. Interestingly, high concentrations of IAG (350 nM) exhibited no effect on PtSoxE expression. Since the hemolymph titer of IAG in

P. trituberculatus has not been reported, the physiological significance of this result is unclear.

Although the tissue distribution analysis did not show high levels of PtSoxE in the testis, the annual expression suggested this may be related to the period in which the samples were tested. High expression of PtSoxE was observed in August and October, a period of rapid spermatogenesis and testicular development. The result was similar to the Sox9 from

S. paramamosain, whose mRNA level was most abundant in the spermatid stage during testicular development [

26]. In mammals and fish, the SoxE family genes have shown their involvement in differentiation and development of testis [

6,

9], and in crustaceans, this function seems to be conserved. Our results showed that silencing in PtSoxE led to the downregulation of several reported spermatogenesis-related genes, including KIFC-1 [

32], Vasa [

33], CyclinB [

34] and Cdc-2 [

35], and vice versa when PtSoxE expression was activated, providing a piece of molecular evidence of the testicular role of PtSoxE.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, a male-specific SoxE from P. trituberculatus was identified and characterized in the present study. It was shown by siRNA mediated silencing that the PtSoxE positively regulates the IAG expression in AG and testis. While on the hand, the PtSoxE could be induced by treating with AG homogenate and rIAG, suggesting a transcriptional interaction between PtSoxE and IAG. The PtSoxE expression showed a closely positively correlation with several reported spermatogenesis-related genes, suggesting its involvement in the testicular development of P. trituberculatus.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1. The cDNA and amino acid sequences of gene encoding SoxE in P. trituberculatus. The initiation codon (ATG) and the stop codon (TAA) are all characterized in bold; the HMG-box is in gray; the Sox family of landmark motifs are all characterized in red font; the glycosylation sites are presented with a frame; the phosphorylation sites are indicated in double underline. Supplementary material 2. The information of other Sox genes.

Author Contributions

D.Z. designed the study, Q.J. wrote the manuscript, D.X. and M.W. performed the experiments and analyzed the data, X.X. revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the National natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41776165 and 31802265), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang province (LY20C190004), and the K. C. Wong Magna Fund in Ningbo University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In China, ethical approval is not required for experiments on crabs. All the experiments comply with the requirements of the governing regulation for the use of experimental animals in Zhejiang Province (Zhejiang provincial government order No. 263, released on 17 August 2009, effective from 1 October 2010) and the Animal Care and Use Committee of Ningbo University.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kamachi, Y.; Kondoh, H. Sox proteins: Regulators of cell fate specification and differentiation. Development 2013, 140, 4129–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbay, J.; Collignon, J.; Koopman, P.; Capel, B.; Economou, A.; Münsterberg, A.; Vivian, N.; Goodfellow, P.; Lovell-Badge, R. A gene mapping to the sex-determining region of the mouse Y chromosome is a member of a novel family of embryonically expressed genes. Nature 1990, 346, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.H.; Berta, P.; Palmer, M.S.; Hawkins, J.R.; Griffiths, B.L.; Smith, M.J.; Foster, J.W.; Frischauf, A.-M.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Goodfellow, P.N. A gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif. Nature 1990, 346, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonatto Paese, C.L.; Leite, D.J.; Schönauer, A.; McGregor, A.P.; Russell, S. Duplication and expression of Sox genes in spiders. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2018, 18, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, W.; Pan, J.; Qin, Q.; Zhong, L.; Shao, J.; Sun, M.; Jiang, H.; Bian, W. Genome-wide identification, phylogeny and expressional profile of the Sox gene family in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D: Genomics and Proteomics 2018, 28, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, B.; Du, H. A review on sox genes in fish. Reviews in Aquaculture 2021, 13, 1986–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Gui, J.F. Genetic basis and biotechnological manipulation of sexual dimorphism and sex determination in fish. Science China Life Sciences 2015, 58, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canning, C.A.; Lovell-Badge, R. Sry and sex determination: How lazy can it be? Trends in Genetics 2002, 18, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopman, P. Sex determination: A tale of two Sox genes. Trends in Genetics 2005, 21, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanco, J.C.; Wilhelm, D.; Davidson, T.L.; Knight, D.; Koopman, P. Sox10 gain-of-function causes XX sex reversal in mice: Implications for human 22q-linked disorders of sex development. Human Molecular Genetics 2010, 19, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolfi, M.C.; Carreira, A.C.O.; Jesus, L.W.O.; Bogerd, J.; Funes, R.M.; Schartl, M.; Sogayar, M.C.; Borella, M.I. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of dmrt1 and sox9 during gonad development and male reproductive cycle in the lambari fish, Astyanax altiparanae. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2015, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, H.; Tveiten, H.; Torgersen, J.S.; Andersen, Ø. Divergent and sex-dimorphic expression of the paralogs of the Sox9-Amh-Cyp19a1 regulatory cascade in developing and adult atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.). Molecular Reproduction and Development 2013, 80, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Jia, Y.; Liu, S.; Chi, M.; Cheng, S.; Gu, Z. Molecular characterization and expression profiles of transcription factor Sox gene family in Culter alburnus. Gene Expression Patterns 2020, 36, 119112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.S.; Hu, W.; Liu, X.C.; Lin, H.R.; Zhu, Z.Y. Molecular cloning and mRNA expression pattern of Sox9 during sex reversal in orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides). Aquaculture 2010, 306, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Du, Q.; Sun, J.; Chang, Z. Molecular cloning and mRNA expression pattern of Sox10 in Paramisgurnus dabryanus. Molecular Biology Reports 2013, 40, 3123–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, T.; Sagi, A. The insulin-like androgenic gland hormone in crustaceans: From a single gene silencing to a wide array of sexual manipulation-based biotechnologies. Biotechnology Advances 2012, 30, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.J.; Jiang, F.W.; Bai, H.K.; Fu, H.T.; Jin, S.B.; Sun, S.M.; Qiao, H.; Zhang, W.Y. Genomic cloning, expression, and single nucleotide polymorphism association analysis of the insulin-like androgenic gland hormone gene in the oriental river prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense). Genetics and Molecular Research 2015, 14, 5910–5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.Y.; Li, J.L.; Qiu, G.F. Identification of putative regulatory region of insulin-like androgenic gland hormone gene (IAG) in the prawn Macrobrachium nipponense and proteins that interact with IAG by using yeast two-hybrid system. General and comparative endocrinology 2016, 229, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jin, S.; Fu, H.; Qiao, H.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, S.; Gong, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, Y. Functional analysis of a SoxE gene in the oriental freshwater prawn, Macrobrachium nipponense by molecular cloning, expression pattern analysis, and in situ hybridization (de Haan, 1849). 3 Biotech 2019, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, X.; Zou, Z.; Liang, K.; Wang, Y. Transcriptional Regulation of Vih by Oct4 and Sox9 in Scylla paramamosain. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xu, R.; Tu, S.; Yu, Q.; Xie, X.; Zhu, D. Putative Role of CFSH in the Eyestalk-AG-Testicular Endocrine Axis of the Swimming Crab Portunus trituberculatus. Animals 2023, 13, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, X.; Wang, M.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, L.; Zhu, D. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of the inverbrate Dmrt1 homologs in the swimming crab, Portunus trituberculatus (Miers, 1876) (Decapoda, Portunidae). Crustaceana 2020, 93, 851–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Liu, H.; Lo, T.S.; Chu, K.H. Inhibitory effects of the androgenic gland on ovarian development in the mud crab Scylla paramamosain. Comparative Biochemistry & Physiology Part A Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2005, 140, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2< sup>− ΔΔCT</sup> Method. methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, J.; Schepers, G.; Koopman, P. Phylogeny of the SOX Family of Developmental Transcription Factors Based on Sequence and Structural Indicators. Developmental Biology 2000, 227, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Liao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Liang, K.; Wang, Y. Molecular cloning, characterization, and expression analysis of a sex-biased transcriptional factor sox9 gene of mud crab Scylla paramamosain. Gene 2021, 774, 145423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Wang, Y.M.; Xu, H.J.; Li, J.W.; Luo, J.Y.; Wang, M.-R.; Ma, W.-M. The characterization and knockdown of a male gonad-specific insulin-like receptor gene in the white shrimp Penaeus vannamei. Aquaculture Reports 2022, 27, 101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herran, B.; Bertaux, J.; Grève, P. Divergent evolution and clade-specific duplications of the Insulin-like Receptor in malacostracan crustaceans. General and comparative endocrinology 2018, 268, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.; Li, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, W. siRNA knockdown of MrIR induces sex reversal in Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Aquaculture 2020, 523, 735172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Zhu, D.F.; Yang, J.F.; Qi, Y. Microstructure and Ultrastructure of Androgenic Gland in Swimming Crab Portunus trituberculatus. Fish. Sci. 2010, 29, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.E.; Zheng, H.; Xie, X.; Xu, R.; Zhu, D. Molecular identification and putative role of insulin growth factor binding protein-related protein (IGFBP-rp) in the swimming crab Portunus trituberculatus. Gene 2022, 833, 146551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.C.; Yang, W.X. Acroframosome-Dependent KIFC1 Facilitates Acrosome Formation during Spermatogenesis in the Caridean Shrimp Exopalaemon modestus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.Y.; Fang, X.; Luo, B.Y.; Qiu, G.F. Identification and characterization of a new germline-specific marker vasa gene and its promoter in the giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2022, 259, 110716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, P.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, T.; Jiang, S.; Qiao, H.; Gong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jin, S.; Fu, H. RNA Interference Analysis of the Functions of Cyclin B in Male Reproductive Development of the Oriental River Prawn (Macrobrachium nipponense). Genes 2022, 13, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, T.; Jiang, S.; Qiao, H.; Gong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Jin, S.; Fu, H. RNA interference analysis of the potential functions of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 in sexual reproduction of male oriental river prawns (Macrobrachium nipponense). Aquaculture International 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).